Abstract

To identify the receptor which may determine the macrophage tropism of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against porcine alveolar macrophages (PAM) were produced. Two MAbs (41D3 and 41D5) which completely blocked PRRSV infection of PAM were further characterized. It was found that they reduce the attachment of PRRSV to PAM and immunoprecipitate a 210-kDa membrane protein from PAM. This protein was detected on the cell membranes of PAM but not of PRRSV-nonpermissive cells. A colocalization was found between the reactive sites of MAb 41D3 and PRRSV on PAM membranes. All PRRSV-infected cells in tissues of experimentally infected pigs reacted with MAb 41D3. Taken together, all these data suggest that the identified 210-kDa membrane protein is a putative receptor for PRRSV on porcine macrophages.

The porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) is a new member of arteriviruses, which also include equine arteritis virus, murine lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus, and simian hemorrhagic fever virus. One striking feature common to these viruses is that the macrophage is the main and may be the only type of cell supporting replication in their respective hosts (10). PRRSV has a restricted tropism for cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage both in vivo and in vitro (1, 3, 7, 11, 12, 14). Of many porcine cell systems tested, only porcine alveolar macrophages (PAM) and some porcine peripheral blood monocytes after cultivation support a productive replication of PRRSV (1–4, 7, 8, 12, 14).

Our previous observations suggested that certain unique virus receptors may contribute to the susceptibilities of cells to PRRSV (4–6). No viral receptors for arteriviruses have been identified so far. In the present study, we attempted to identify the PRRSV receptor on PAM by generation of PAM-specific monoclonal antibodies (MAbs). To increase the chance of obtaining PAM-specific MAbs, BALB/c mice were made immunologically tolerant with freshly isolated porcine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) before immunization with PAM. Two MAbs (41D3 and 41D5) which reacted with PAM and blocked PRRSV infection of PAM were obtained (5). These two MAbs were affinity purified with goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG)-agarose (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and used in a number of experiments to identify the putative virus receptors on PAM.

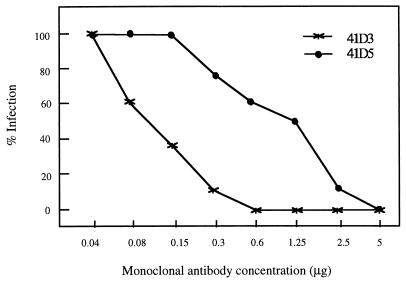

We first examined whether preincubation of PAM with affinity-purified anti-PAM MAbs 41D3 and 41D5 inhibited subsequent virus replication in the cells. PAM grown in a 96-well plate were incubated with different amounts of MAbs 41D3 and 41D5 and isotype-matched controls for 60 min on ice, washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and inoculated with 50 μl of medium containing 100 50% tissue culture infective doses of PRRSV (Lelystad isolate). After a 48-h incubation at 37°C, the cells were fixed and stained with swine anti-PRRSV sera according to an immunoperoxidase monolayer assay as previously described (13). It was found that as little as 0.6 μg of MAb 41D3 per ml and 5 μg of MAb 41D5 per ml completely protected 105 PAM from PRRSV infection. The protective effect of MAbs 41D3 and 41D5 was concentration dependent (Fig. 1). None of the control MAbs affected PRRSV replication. MAbs 41D3 and 41D5 exhibited a similar blocking capacity with PRRSV (94V360), a MARC-145-cell-adapted Belgian isolate (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Ability of MAbs 41D3 and 41D5 to inhibit PRRSV infection of PAM. Each value is the mean of results from three experiments with PAM originating from three different pigs.

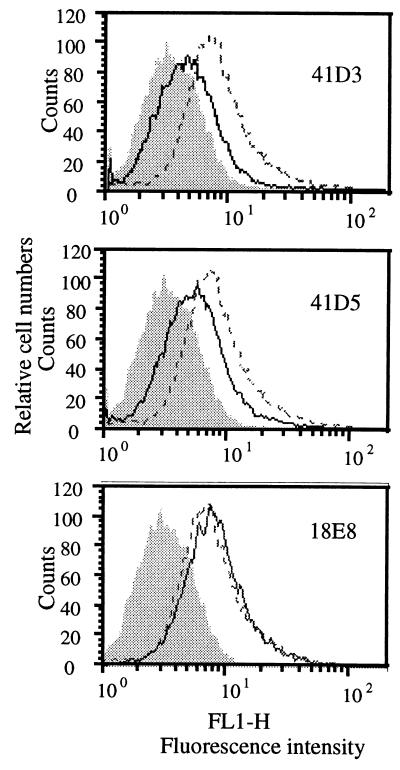

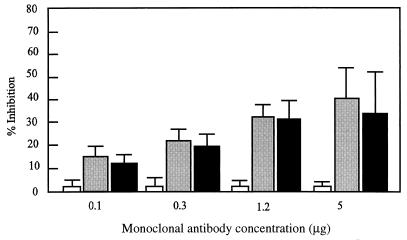

We next tested whether MAbs 41D3 and 41D5 prevented PRRSV binding to PAM. PAM (2 × 105) were incubated with serial dilutions of MAbs 41D3 and 41D5 or of isotype-matched control MAbs 18E8, 13D12, 26A8, and 4G3 (9) for 60 min on ice before being subjected to about 0.5 μg of biotinylated virus. The cells were stained with streptavidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Amersham International, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Pretreatment of PAM with MAbs 41D3 and 41D5 resulted in a 40 to 65% reduction of virus binding compared to the amount of biotinylated PRRSV bound in the presence of the negative control IgG1 antibody (Fig. 2). The inhibition of PRRSV attachment to PAM by MAbs 41D3 and 41D5 was shown to be concentration dependent (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of the inhibition of PRRSV binding to PAM by MAbs 41D3 and 41D5. PAM (2 × 105) cultivated for 1 day were preincubated with 5 μg of affinity-purified MAb 41D3 or 41D5 or irrelevant control MAb 18E8 prior to the addition of 5 μg of biotinylated PRRSV. The fluorescence of cells preincubated with antibody is shown as a solid-line histogram, the autofluorescence of cells (without virus) is shown as a shaded histogram, and the fluorescence of cells without antibodies is shown as a dashed-line histogram.

FIG. 3.

Ability of MAbs 41D3 and 41D5 to prevent PRRSV attachment to PAM. Fifty microliters of various dilutions of affinity-purified anti-PAM MAbs 41D3 (black bar) and 41D5 (grey bar) or of the isotype-matched irrelevant MAb 18E8 (white bar) was preincubated with 2 × 105 PAM before incubation with biotinylated PRRSV. Fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry, and inhibition was expressed as a percentage of that of the control (without MAbs). Each value is the mean of results from three experiments with PAM originating from three different pigs.

To examine whether the expression of the MAb 41D3- or 41D5-reactive antigen(s) on the membranes of different cell types is correlated with the cells’ susceptibility to PRRSV, a variety of cell lines (PK-15, SK, ST, and MARC-145) and porcine monocyte/macrophage lineage cells were examined by flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy. When membrane immunofluorescence staining of PAM was performed with either MAb 41D3 or 41D5 as the primary antibody, all cells were positive, but when staining was performed with irrelevant IgG1 antibodies, all cells were negative. Fluorescence staining was absent on the membranes of PRRSV-nonpermissive cells, which include PBMC; porcine peritoneal macrophages; and ST, SK, and PK-15 cells. Cells from a PRRSV-permissive cell line, MARC-145 (8), were also negatively stained with MAbs 41D3 and 41DS. Together with the observation that some PRRSV isolates need to be adapted to infect MARC-145 cells, our results may indicate that PRRSV enters MARC-145 cells by a pathway which is different from that of PAM. When MAb 41D3 or 41D5 was used as the primary antibody on acetone-fixed cells, PAM cells were strongly stained but ST, SK, PK-15, and MARC-145 cells showed no staining. A faint cytoplasmic staining of some PBMC and porcine peritoneal macrophages was observed. No staining was found in all cell types when isotype-matched irrelevant antibodies were used as primary antibodies.

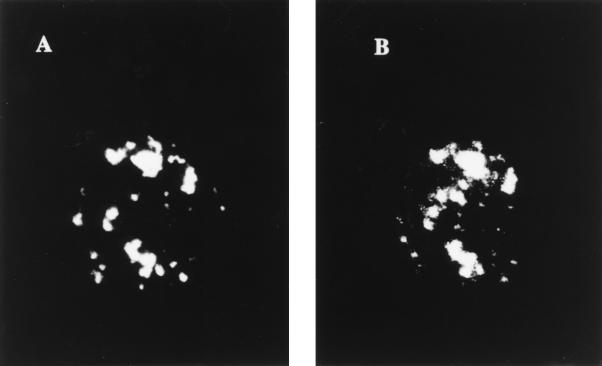

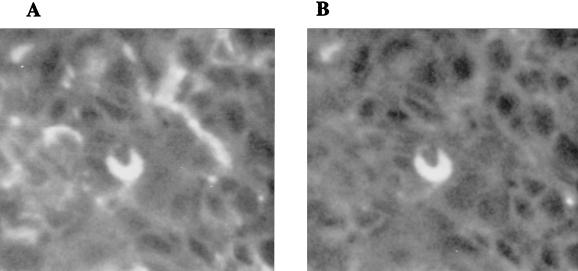

When PAM were stained with both MAb 41D3 and fluorescence-labelled PRRSV and analyzed by confocal microscopy, a clear colocalization was found on the membranes of PAM (Fig. 4). This result suggests that MAb 41D3 and PRRSV react with the same structure(s) on the surfaces of PAM.

FIG. 4.

Colocalization of MAb 41D3 and biotinylated PRRSV on the membranes of PAM. PAM were subsequently incubated with biotinylated PRRSV–streptavidin-FITC and MAb 41D3–goat anti-mouse IgG–Texas red. Images were produced by superposition of 10 images of different focal planes which were taken with a confocal laser scanning system with a distance of 1 μm between each plane. Images were analyzed for Texas red staining at a 568-nm excitation (A) and for FITC staining at a 488-nm excitation (B).

In order to determine if PRRSV-antigen-positive cells in the tissues of experimentally infected pigs also contain the MAb 41D3 antigen, we performed a double immunofluorescence staining using sections of various tissues from experimentally PRRSV-infected pigs and uninfected controls (3). It was found that all the cells which contained PRRSV antigens in lungs, thymus, tonsils, spleen, and lymph nodes from the experimentally PRRSV-infected pigs also stained with MAb 41D3 (Fig. 5). No double staining was observed in the tissue sections from normal pigs or when isotype-matched irrelevant antibodies were used.

FIG. 5.

MAb 41D3 recognizes PRRSV-antigen-positive cells in experimentally infected pigs. A section of lung tissue from an experimentally PRRSV-infected pig was double stained with MAb 41D3–goat anti-mouse IgG–Texas red and swine anti-PRRSV IgG-FITC. Images for Texas red staining (568-nm excitation) (A) and for FITC staining (488-nm excitation) (B) were observed with a confocal laser scanning system.

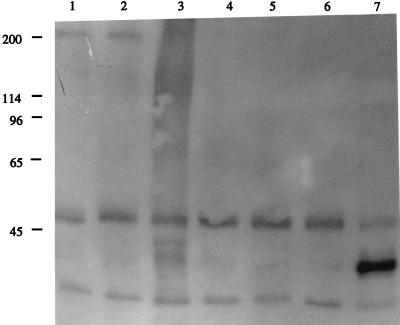

We predicted from the above-described data that MAbs 41D3 and 41D5 block PRRSV infection of PAM by binding to molecules which are used for virus attachment on the surfaces of PAM. To identify these molecules, PAM cell membrane proteins were labelled by using a protein biotinylation kit (Amersham International). Biotinylated cell lysate was precleared with insoluble protein A (Sigma), and proteins were immunoprecipitated with MAbs 41D3 and 41D5 or various control MAbs. Standard sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed with a 4- to 20%-gradient minigel system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). The separated proteins were blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and detected with an enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting detection reagent containing horseradish peroxidase substrate (Amersham International). A biotin-labelled protein with a molecular mass of approximately 210 kDa was specifically precipitated by MAbs 41D3 and 41D5. Faint background bands and two unspecific bands with molecular masses of 49 and 25 kDa were also seen in the absence of MAbs or after immunoprecipitation with control MAbs (Fig. 6). The specificities of MAbs 41D3 and 41D5 for this 210-kDa protein were further examined by a Western blotting assay in which the cell lysates prepared from PRRSV-nonpermissive cells (PK-15) were used as a negative control. A specific protein band with a molecular mass of about 210 kDa was detected only in the cell lysates of PAM with purified MAbs 41D3 and 41D5 and not in the cell lysates of PK-15 or with control MAbs.

FIG. 6.

MAbs 41D3 and 41D5 immunoprecipitate a 210-kDa protein from biotinylated PAM cell membrane preparations. PAM membrane proteins were labelled with biotin and prepared, and an immunoprecipitation assay was performed. MAbs 41D3 and 41D5 (lanes 1 and 2, respectively) specifically precipitate a 210-kDa protein. Isotype-matched irrelevant MAbs 18E8, 13D12, and 4G3 (lanes 3 to 5, respectively) and a control with no first antibody (lane 6) were used as negative controls. MAb 26A8 (lane 7), which reacts with PAM and recognizes an abundant 40-kDa PAM membrane protein but has no effect upon PRRSV infection, was used as a positive control. Molecular mass standards (in thousands) are noted at the left.

In summary, we have isolated two anti-PAM MAbs which reduce PRRSV attachment and block PRRSV infection. Both MAbs recognize a 210-kDa membrane protein on PAM. This 210-kDa protein is expressed only on the cell membranes of PRRSV-permissive PAM and not on those of nonpermissive cells, which suggests that this protein may determine the unique cell and tissue specificity of the virus. All these data show that this protein appears to fulfil the criteria for a PRRSV receptor. The characterization of the 210-kDa protein by amino acid analysis of immunoaffinity-purified 210-kDa peptides or by cDNA cloning may further help to clarify its role in the regulation of the tropism of the virus.

Acknowledgments

We thank Patrick Van Oostveldt (Faculty of Agricultural and Applied Biological Sciences, Ghent, Belgium) for his help with confocal image analysis and G. Charlier (National Veterinary Research Institute, Brussels, Belgium) for the electromicroscopic quantification of purified PRRSV.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benfield D A, Nelson E, Collins J E. Characterisation of swine infertility and respiratory syndrome (SIRS) virus (isolate ATCC VR-2332) J Vet Diagn Invest. 1992;4:127–133. doi: 10.1177/104063879200400202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins J E, Benfield D A, Christianson W T, Harris L, Hennings J C, Shaw D P, Goyal S M, McCullough S, Morrison R B, Joo H S, Gorcyca D, Chladek D. Isolation of swine infertility and respiratory syndrome virus in North America and experimental reproduction of the disease in gnotobiotic pigs. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1992;4:117–126. doi: 10.1177/104063879200400201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duan X, Nauwynck H J, Pensaert M B. Virus quantification and identification of cellular targets in the lungs and lymphoid tissues of pigs at different time intervals after inoculation with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) Vet Microbiol. 1997;56:9–19. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(96)01347-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duan X, Nauwynck H J, Pensaert M B. The effect of origin, differentiation and activation status of porcine monocytes/macrophages on their susceptibility to PRRSV infection. Arch Virol. 1997;142:2483–2497. doi: 10.1007/s007050050256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duan, X., H. J. Nauwynck, H. W. Favoreel, and M. B. Pensaert. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection of alveolar macrophages can be blocked by monoclonal antibodies against cell surface antigens. In L. Enjuanes, S. Siddell, and W. Spaan (ed.), Advances in experimental medicine and biology: coronaviruses and arteriviruses, in press. Plenum Publishing Corporation, New York, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Duan, X., H. J. Nauwynck, and M. B. Pensaert. 1997. Unpublished data.

- 7.Halbur P G, Miller L D, Paul P S, Meng X J, Huffman E L, Andrews J J. Immunohistochemical identification of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) antigen in the heart and lymphoid system of three-week-old colostrum-deprived pigs. Vet Pathol. 1995;32:200–204. doi: 10.1177/030098589503200218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim H S, Kwang J, Yoon I, Joo H S, Frey M L. Enhanced replication of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus in a homogeneous subpopulation of MA-104 cell line. Arch Virol. 1993;133:477–483. doi: 10.1007/BF01313785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nauwynck H J, Pensaert M B. Effect of specific antibodies on the cell-associated spread of pseudorabies virus in monolayers of different cell types. Arch Virol. 1995;140:1137–1146. doi: 10.1007/BF01315422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plagemann P G W, Moennig V. Lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus, equine arteritis virus, and simian hemorrhagic fever virus: a new group of positive-strand RNA viruses. Adv Virus Res. 1992;41:99–192. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60036-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossow K D, Benfield D A, Goyal S M, Nelson E A, Hennings C, Jr, Collins J E. Chronological immunohistochemical detection and localization of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in gnotobiotic pigs. Vet Pathol. 1996;33:551–556. doi: 10.1177/030098589603300510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voicu I L, Silim A, Morin M, Elazhary M A S Y. Interaction of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus with swine monocytes. Vet Rec. 1994;134:422–423. doi: 10.1136/vr.134.16.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wensvoort G, Terpstra C, Pol J M A, ter Laak E A, Bloemraad M, de Kluyver E P, Kragten C, van Buiten L, den Besten A, Wagenaar F, Broekhuijsen J M, Moonen P L J M, Zetstra T, de Boer E A, Tibben H J, de Jong M F, van Veld P, Groenland G J R, van Gennep J A, Voets M T, Verheijden J H M, Braamskamp J. Mystery swine disease in The Netherlands: the isolation of the Lelystad virus. Vet Q. 1991;13:121–130. doi: 10.1080/01652176.1991.9694296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon I J, Joo H S, Christianson W T, Morrison R B, Dial G D. Isolation of a cytopathic virus from weak pigs on farms with a history of swine infertility and respiratory syndrome. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1992;4:139–143. doi: 10.1177/104063879200400204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]