Abstract

Disruption of meiosis and DNA repair genes is associated with female fertility disorders like premature ovarian insufficiency (POI). In this study, we identified a homozygous missense variant in the HELQ gene (c.596 A>C; p.Gln199Pro) through whole exome sequencing in a POI patient, a condition associated with disrupted ovarian function and female infertility. HELQ, an enzyme involved in DNA repair, plays a crucial role in repairing DNA cross-links and has been linked to germ cell maintenance, fertility, and tumour suppression in mice. To explore the potential association of the HELQ variant with POI, we used CRISPR/Cas9 to create a knock-in mouse model harbouring the equivalent of the human HELQ variant identified in the POI patient. Surprisingly, Helq knock-in mice showed no discernible phenotype, with fertility levels, histological features, and follicle development similar to wild-type mice. Despite the lack of observable effects in mice, the potential role of HELQ in human fertility, especially in the context of POI, should not be dismissed. Larger studies encompassing diverse ethnic populations and alternative functional approaches will be necessary to further examine the role of HELQ in POI. Our results underscore the potential uncertainties associated with genomic variants and the limitations of in vivo animal modelling.

Keywords: premature ovarian insufficiency, HELQ, ovarian development, infertility

1. Introduction

Premature ovarian insufficiency is a condition that can result from premature depletion of oocytes and/or abnormal ovarian development and affects up to 4% of women of reproductive age. It is characterized by elevated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and amenorrhea before the age of 40 years [1,2]. POI is a leading cause of infertility in women, and while it is believed to have a strong genetic component, its genetic basis is not yet fully understood [3]. Currently, over 80 genes have been linked to POI, with critical roles in various cellular and molecular pathways such as gonadogenesis, folliculogenesis, endocrine signalling, cell growth and division, DNA damage repair, metabolism and autoimmunity [4,5,6]. However, these genes only account for a minority of POI cases.

Oogenesis is a complex process that involves both mitotic and meiotic cellular divisions, leading to the production of a mature oocyte [7]. In humans, oogenesis begins with rapid mitotic cell divisions that give rise to approximately 7 million oogonia, which either commit to a developmental fate or are lost through atresia [8]. After this initial phase, oogonia enter meiosis during prenatal development and undergo a rapid arrest during the diplotene stage of meiotic prophase I and remain dormant until puberty [9,10]. At that point, just before ovulation, luteinising hormone (LH) secretion triggers meiosis resumption. The primordial follicle, which is present during the initial stages of oogenesis, exhibits extreme longevity and features a distinctive structure that makes the nucleus of the oocyte susceptible to DNA damage [11]. Therefore, the proper functioning of the DNA repair system is crucial for maintaining genomic integrity in oocytes. This protects against the development of germline mutations and eliminates oocytes with compromised DNA integrity during oocyte maturation [12,13]. Numerous genes are involved in regulating DNA replication, DNA damage repair, and homologous recombination during meiosis, many of which are necessary for normal ovarian function and female fertility [14,15]. Disruptions to some of these genes, including MCM8/9, REC8, HROB, NUP107, STAG3, HFM1, POF1B, SWI5, HELQ, MND1, PSMC3IP, MSH4/5, CSB-PGBD3, and ATM (summarised in Table 1), have previously been associated with POI in females. In prophase I of meiosis, homologous recombination (HR) is triggered by DNA double-strand breaks (DSB) and enables the exchange of large sections of the DNA double helix between paired homologous chromosomes. This dynamic pathway is essential for generating genetic diversity and plays a crucial role in repairing damaged DNA [16,17]. One of the important genes that plays a crucial role in various DNA processes such as replication, recombination, and inter-strand crosslink repair is HELQ [18]. Previous studies have linked the ortholog of HELQ in Drosophila melanogaster (Mus301 or Spn-C3) and C. elegans (Helq-1 or Hel-3084) to the repair of meiotic double-strand breaks (DSB) and the activation of the meiotic checkpoint [19,20]. In humans, HELQ encodes the protein HEL308, which acts as a DNA-dependent ATPase and DNA helicase. It is believed that helicases are critical for strand invasion as they can unwind the D loop, making homologous DNA available for the invading strand. There are two parallel helicase pathways involved in this process. One pathway involves the helicase HELQ, which is associated with ATR and RAD51 paralogs, while the other pathway involves the helicases MCM8 and MCM9, which are recruited by HROB [18,21]. As reported previously, deficiency of Helq leads to reduced germ cell numbers in both male and female mice indicating the critical role of Helq in germ cell maintenance [22,23]. In humans, HELQ is expressed in the testes, ovaries, heart, and skeletal muscle [24]. However, its significance in human reproduction remains unclear and further research is necessary to define its role and underlying mechanisms. A meta-analysis of 22 genome-wide association studies conducted on women of European descent has found a correlation between HELQ and the age of natural menopause [25]. In a previous report, no causative variant in HELQ was found among Chinese Han women with secondary amenorrhea [26]. However, a recent study on a large cohort of individuals with POI proposed a potential link between HELQ variants and the pathogenicity of POI [27]. In this study, we used WES to identify a novel homozygous missense variant in HELQ in a POI patient and investigate its potential pathogenicity using mouse modelling.

Table 1.

Candidate genes involved in meiosis, DNA replication, and repair implicated in premature ovarian insufficiency. AR: Autosomal recessive variants have been reported. AD: Autosomal dominant variants have been reported.

| Gene | Inheritance | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| MCM 8 | AR, AD | [21,28,29,30,31,32,33] |

| MCM 9 | AR, AD | [30,34,35,36,37,38] |

| REC8 | AR, AD | [21,39] |

| HROB (C18orf53) | AR | [21,27] |

| NUP107 | AR | [21,40] |

| STAG3 | AR | [21,41] |

| HFM1 | AR | [21,42] |

| POF1B | AR, AD | [21,43,44] |

| SWI5 | AR | [27] |

| HELQ | AD, AR | [25,27,45] |

| MND1 | AR | [46] |

| PSMC3IP | AR | [47,48] |

| MSH4 | AR | [27,49] |

| MSH5 | AR, AD | [50,51] |

| MSH6 | - | [45] |

| CSB-PGBD3 | AD | [52] |

| ATM | AD | [27] |

| PRIM1 | - | [25] |

| DMC1 | AR | [53,54,55] |

| MEIOB | AR | [56,57] |

| SYCP2L | AR | [58] |

| SYCE1 | AR | [59] |

| HSF2BP | AR | [60,61] |

| TP63 | AD | [62,63] |

| ZSWIM7 | AR | [64,65] |

| FANCM | AR | [27,66,67] |

| FANCL | AD | [68] |

| FANCA | AD | [69] |

| FANCU (XRCC2) | AR | [70] |

| FANCI | - | [25] |

| BRCA1 (FANCS) | - | [45] |

| BRCA2 (FANCD1) | AR | [27] |

| SMC1B | AD | [39] |

| SGO2 | AR | [71] |

| SPIDR | AR | [27,72] |

| EXO1 | AD | [25,73] |

| RAD51 | AD | [73] |

| WDR62 | AD | [74] |

| NBN | AR | [75] |

| UIMC1 | - | [25] |

| ERCC6 | AD | [27] |

| LLGL1 | AD | [45] |

| BOD1L1 | AD | [45] |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient’s Clinical Information

The patient was carefully selected based on clinical consultations, with the exclusion of patients who had a known aetiology of POI, such as those who underwent chemotherapy, radiotherapy, gonadotoxic therapy, or ovarian surgery and individuals with FMR1 premutation or an abnormal karyotype. The patient described here was born to non-consanguineous parents and received a diagnosis of POI at the age of 18 years. She presented with primary amenorrhea, elevated FSH (125 IU/L), and low AMH (0.15 ng/mL). Abdominal ultrasound revealed small ovaries. Further endocrinological assessment indicated the presence of hyperandrogenism with hirsutism and elevated anti-thyroid antibodies in the patient. All procedures were in compliance with the ethical standards of the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

2.2. General Molecular Techniques

Genomic DNA was extracted from EDTA-blood samples obtained from the patients manually with the NucleoSpin® Blood XL kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) or using an automated system, Hamilton Microlab STAR and Nucleospin® Blood L kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality of the DNA was evaluated using a NanoDrop™ 1000 spectrophotometer and the Qubit dsDNA BR Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Selected variants were validated by Sanger sequencing using BigDye v3.1 Terminators (Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX, USA) and ABI 3130X (Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX, USA).

2.3. Whole-Exome Sequencing

The genomic DNA underwent WES at the Victorian Clinical Genetics Service (VCGS), with exome capture using SureSelect Human All Exon V6 (Agilent, Melbourne, Australia). The sequencing was carried out on the NextSeq 500/550 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). WES data were processed using a Cpipe pipeline [76] and analysed using SeqR (https://seqr.broadinstitute.org/, seqr v1.0-83775191; accessed on 12 May 2023). Two different approaches were employed to analyse WES data as previously described [62]. The first was gene-centric and focused on gene priority using POI candidate genes (adapted from [62]) and the second was variant-centric and focused on variant priority. For variant-centric analysis, moderate-high priority (MAF < 0.001) biallelic variants in any gene or high priority loss of function variants (MAF < 0.0001) were considered. GnomAD (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/, accessed on 12 May 2023) was used for analysing the minor allele frequency (MAF) as well as the tolerance of genes to missense and/or loss-of-function variation. To predict the pathogenicity of variants in silico, several online algorithms were utilised, all of which were accessed on 12 May 2023, including SIFT/Provean (https://provean.jcvi.org/version 2023), Polyphen2 (https://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2; v2), Mutation Taster (https://www.mutationtaster.org/; v2) and CADD (Combined Annotation-Dependent Depletion) score (https://cadd.gs.washington.edu/snv; v1.6). The conservation of affected residues was analysed using Multiz Alignments of 100 vertebrates (UCSC Genome Browser https://genome.ucsc.edu/; v 2023) as well as the Decipher database (https://www.deciphergenomics.org/; v11.22).

2.4. Mice

All procedures involving animals for the generation of knock-in mice were conducted at the Melbourne Advanced Genome Editing Centre (MAGEC) gene editing facility, located within the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute. F1 heterozygous mice of the C57BL/6J background were bred at the Disease Model Unit animal facility of MCRI to establish the knock-in line. Mice were kept in a temperature-controlled facility (25 ± 1 °C) and on a 12 h light: 12 h darkness regimen under specific pathogen-free conditions with mouse chow freely available. The experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee (AEC) of the Royal Children’s Hospital. Cervical dislocation was used as the method of euthanasia for the mice. Testes and ovaries were individually measured and weighed.

2.5. Production of CRISPR/Cas9 Knock-In Mice

To generate the Helq knock-in mice, a Q161P mutation was introduced within the Helq gene located on chromosome 5 of the mice from a C57BL/6J background. 20 ng μL−1 of Cas9 mRNA, 10 ng μL−1 of a single guide RNA (sgRNA) sequence (AAGTATAAAATTTGAGAAGA) and 40 ng μL−1 of the oligo donor (CTAGATGTCCCTGCTGAACCAGAACCTGGAAGCGATCTTTCGTTTGATGTGCCTTCTTCTctATTTTATACTTTGAAAATCCGCAGAACTCACCAGAAGCTTTGGGCGATCCGTGCACTAG) (in which uppercase bases denote exons and lowercase bases denote intron sequences) were injected into the cytoplasm of fertilised one-cell stage embryos generated from wild-type C57BL/6J breeders. After a period of 24 h, two-cell stage embryos were transferred into the uteri of pseudo-pregnant female mice. To confirm the integration of the oligo donor, the viable offspring were genotyped by next-generation sequencing using the forward primer AACCTCACTGACCCGGAAAC and the reverse primer ACTCTGAAGCAGCTCTGACG. Out of the offspring, five F0 mice were selected for subsequent backcrossing with wild-type mice to produce F1 heterozygous mice.

2.6. Genotyping

An assay utilizing restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) was used to genotype the Helq knock-in mice. The procedure involved amplifying a specific DNA fragment encompassing the Helq variant through PCR, followed by digestion with ApoI, an enzyme that selectively cleaves the wild-type DNA but not the DNA carrying the variant. The resulting DNA fragments were then separated and visualized on an agarose gel, enabling the identification of different genotypes (homozygous, heterozygous and wild-type). Restriction digest of the wild-type PCR product resulted in two fragments measuring 296 bp and 404 bp, whereas restriction digest of the Helq variant led to a single 700 bp product. The primer sequences used for genotyping were GCGAAGAGGACATGTTTGGT as the reverse primer and CCATATAGCTTTTTGATTCCTTTCA as the forward primer. Additionally, PCR was performed for the biological sex of the mice. The presence of PCR products for both Sry and Hprt indicated male sex, while only Hprt amplicons were indicative of female sex. We allocated the mice to four different experimental groups: i. Fertility assessment, ii. Histological and morphological analysis of gonads, iii. Quantitative assessment of ovarian follicles, iv. Longevity study for survival/tumorigenesis analysis.

2.7. Fertility Assessment

For fertility tests of HelqKI/KI knock-in mice, we established five parallel crosses over a period of 6 months. These included a total of 60 mice, divided into six breeding pairs for each of the five different genotype crosses, namely Hom × Hom, Wt × Wt, Het × Het, Hom (male) × Het (female), and Hom (female) × Het (male). Subsequently, the variations in the number of litters and pups among these five breeding groups were evaluated.

2.8. Histology and Immunohistochemistry and Reagents

Ovaries and testes were collected from all genotypes of C57BL/6J mice per experimental group (n = 72, six mice per sex and per genotype at two time points, 3-month-old and 6-month-old mice). Gonads were fixed (ovaries in 4% PFA, one of the testes in Bouin’s solution and the other in 4% PFA), paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at 5 μm. Every fifth section was collected for morphological, histological, and immunofluorescent analysis, using standard procedures. To illustrate the morphological difference between wild-type and HelqKI/KI mice, fixed gonads of mice were sectioned and deparaffinised in xylene and rehydrated in a graded series of ethanol. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and periodic acid-schiff (PAS) were used to stain the prepared sections from both ovaries and testes.

The subsequent primary antibody employed for the immunostaining of the ovarian sections was Rabbit anti-FOXL2 [77] as a marker of granulosa cells of ovaries. Goat anti-rabbit-HRP was used as a secondary antibody. Slides were developed in DAB substrate and counterstained with Hematoxylin.

2.9. Quantification of Ovarian Follicular Numbers

Quantification analysis of ovarian sections was performed to determine any differences between the number of follicles in the ovaries of Helq knock-in and wild-type mice. Serial sectioning at 5 μm of ovaries from in 6-month-old females (n = 21, seven mice per genotype) was performed at Melbourne Histology Platform of the University of Melbourne with every 10th section used for the quantification.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for FOXL2 was conducted to visualise distinct developmental stages of follicles, with a particular focus on identifying smaller primordial follicles. Follicles were classified as primordial if they contained an oocyte surrounded by a partial or complete layer of squamous granulosa cells. Primary follicles showed a single layer of cuboidal granulosa cells. Follicles were classed as secondary if they possessed more than one layer of granulosa cells with no visible antrum. Early antral follicles possessed generally only one or two small areas of follicular fluid (antrum) whilst antral follicles possessed a single large antral space. The follicle classes were quantified separately and using light microscopy. Only follicles with visible oocyte and zona pellucida were counted.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

For evaluating the statistical significance of differences between groups we used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey post hoc tests. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using GraphPad (version 9.0.0 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA USA, www.graphpad.com, accessed on 12 May 2023).

3. Results

3.1. Identification of a Homozygous Missense Variant in HELQ

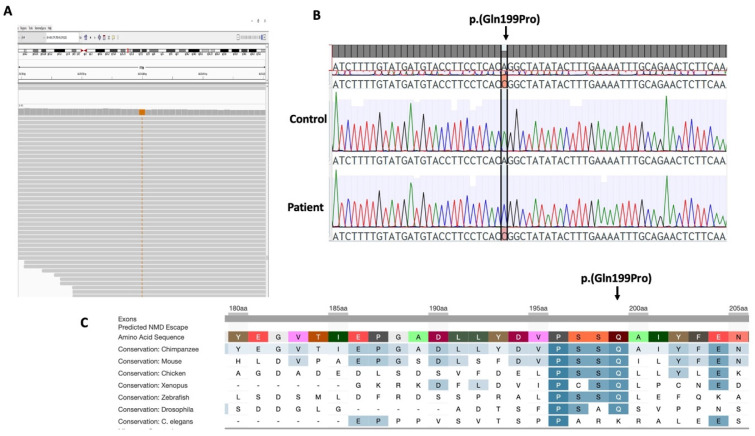

In an effort to understand the genetic basis of POI, we used WES to analyse a patient diagnosed with POI and primary amenorrhea. In the patient, gene-centric and variant centric analysis detected 41 variants of interest in the proband (Table 2). These variants were further analysed for their likely role in causing the patient phenotype and many of them were discarded based on weak in silico evidence for impact and/or only weak association of the gene with potential POI pathogenicity. We considered a homozygous HELQ missense variant (Chr4:83453647T>G, NM_133636.5: c.596 A>C; p.(Gln199Pro)) as the top candidate, primarily because it was the sole gene identified by both gene-centric and variant-centric analyses. Sanger sequencing validated the HELQ variant in the patient (Figure 1A,B). This variant is absent in population databases (gnomAD, ExAC) and predicted as pathogenic by online algorithms including SIFT (score 0), Polyphen (Score 0.99), CADD (PHRED score 23.9), and MutationTaster (score 1.00). The HELQ gene variant affects an evolutionarily conserved residue (Figure 1C) suggesting that changes at this site are likely to be detrimental to protein function. The effects of the HELQ missense variant on the protein structure were analysed using HOPE. The variant residue differs in size and hydrophobicity compared to the wild-type residue. The HELQ variant, p.(Gln199Pro), introduces a smaller and more hydrophobic residue at this position potentially disrupting interactions, hydrogen bonds, and proper protein folding [78].

Table 2.

Genes identified with variants of interest after filtration.

| Gene-Centric Analysis | Variant-Centric Analysis (Recessive) | Variant-Centric Analysis (LOF) |

|---|---|---|

| Moderate-high priority, MAF < 0.001, high-quality, POI candidate genes | Moderate-high priority, MAF < 0.001, high-quality, recessive inheritance | High priority, MAF < 0.0001, high-quality |

| 14 variants (14 genes): INSRR, LAMC1, VWA5B2, HELQ, MRPS30, BBS9, RGS22, PCSK5, CENPJ, MLH3, MRPS11, SLX4, LONP1, BMP2 | 14 variants (8 genes): WDR78, HELQ, ZBED8, ZBTB43, DEPDC7, CD63, LIPC, ZNF20 | 14 variants (12 genes): PRAMEF4, MROH7, ZBTB41, OSMR, STK32A, RABEPK, C10orf90, SLC6A5, LINS1, PTPN2, ZNF544, TSPAN6 |

Figure 1.

A homozygous missense variant in HELQ. (A) IGV view of HELQ variant (c.596 A>C; p.(Gln199Pro)) variant in an isolated POI patient. (B) Sanger sequencing of the patient was consistent with the WES results. (C) Decipher view of the variant indicating conservation of the affected residue among the different species.

3.2. HelqKI/KI Mice Are Fertile

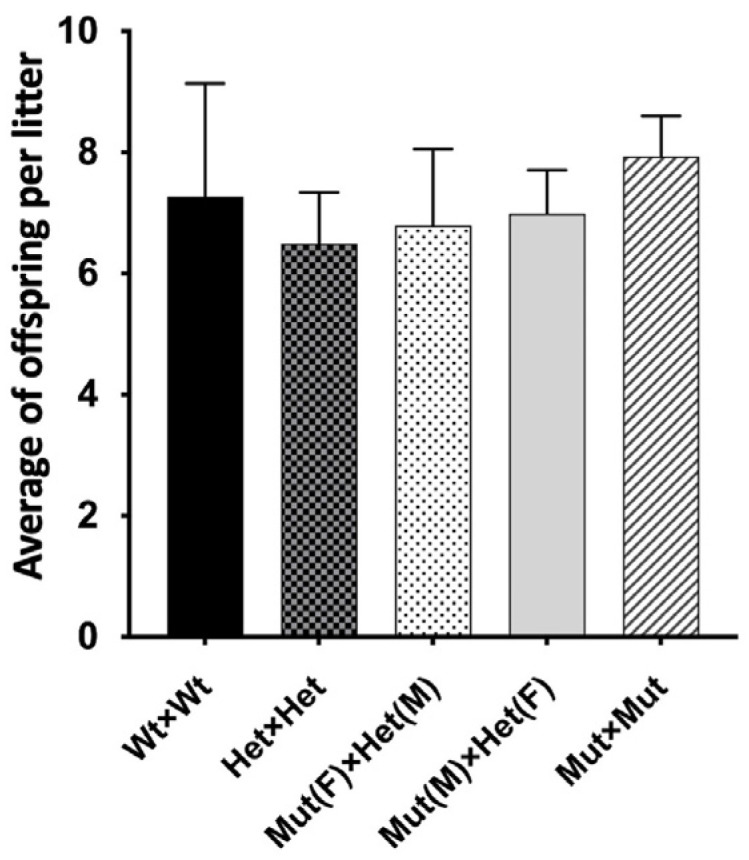

To investigate the effect of the HELQ variant we established Helq knock-in (HelqKI/KI) mice using CRISPR/Cas9. Homozygous HelqKI/KI mice were born at the expected ratio and had an apparently wild-type phenotype. To assess the reproductive potential of HelqKI/KI, we established six breeding pairs for each of five different genotype crosses: Hom × Hom, Wt × Wt, Het × Het, Hom (male) × Het (female), and Hom (female) × Het (male). Comparing the number of pups and the interval between litters among these five breeding groups over a period of 6 months showed that there were no significant differences in the numbers of offspring (Figure 2) and the interval between litters among and HelqKI/KI and Het/Wt mice. This indicates that both male and female HelqKI/KI mice have fertility levels comparable to those of Het/Wt mice.

Figure 2.

Fertility assessment of HelqKI/KI mice. Bar chart shows average offspring per litter in five genotype crosses. No significant differences found in offspring count among five breeding groups over a 6-month breeding period (n = 60) (ANOVA p > 0.05).

3.3. HelqKI/KI Mice Have Normal Ovarian Weight, Morphology and Follicle Number

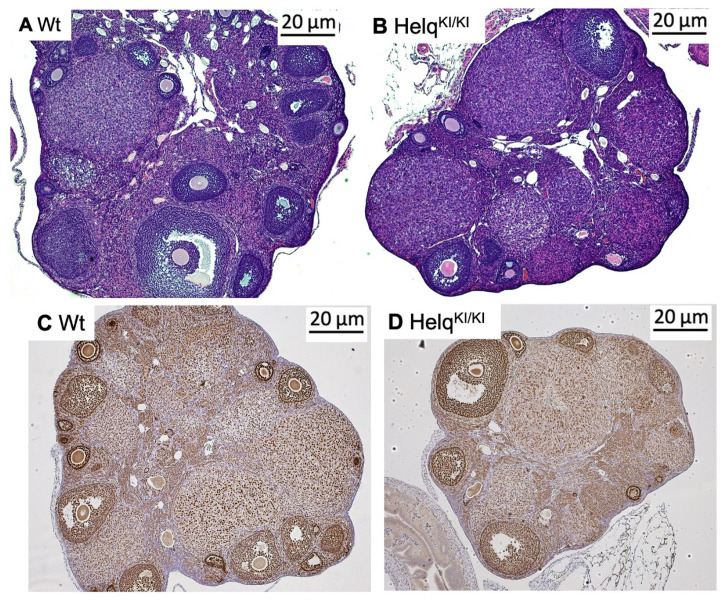

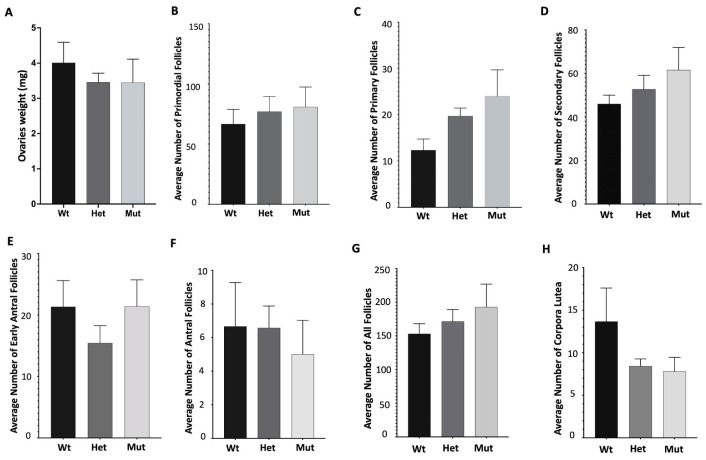

In light of the observed dysgenesis and atrophy in ovaries in knock-out mice [22,23], we opted to examine ovarian weight and morphology in knock-in mice. To investigate ovarian morphology between Helq knock-in and wild-type mice, ovarian sections from female mice at two time points, 3 months and 6 months, were stained with H&E. Morphological assessment of the H&E-stained sections did not show any apparent differences in HelqKI/KI mice compared to the Het and Wt groups (Figure 3A–D). There were no significant differences in ovarian weight of HelqKI/KI mice compared to the Het and Wt groups (Figure 4A). Quantification of follicular numbers was performed on ovarian sections obtained from 6-month-old female mice of three different genotypes. The analysis revealed no significant differences in the total number of follicles or individual follicle types between HelqKI/KI and Het and Wt ovaries. Additionally, there were no differences in the number of corpora lutea (CL) among the mice (Figure 4B–H).

Figure 3.

Histological analysis of HelqKI/KI ovaries. No differences were observed in the H&E-stained ovarian sections of 3-month-old HelqKI/KI mice compared with Wt mice (A,B). Immunostaining of ovarian sections with FOXL2 showed no differences in morphology of ovarian sections in 6-month-old HelqKI/KI mice compared to Het/Wt mice (C,D) (n = 36).

Figure 4.

Analysis of follicular numbers in ovarian sections of 6-month-old mice. There was no significant difference in the weights of ovaries of HelqKI/KI mice compared to Het and Wt mice (A). There were also no significant differences in the average number of primordial (B), primary (C), secondary (D), early antral (E) antral follicles (F), all follicles (G), as well as corpora lutea in HelqKI/KI compared to Het and Wt mice (H) (n = 21) (all ANOVA p > 0.05).

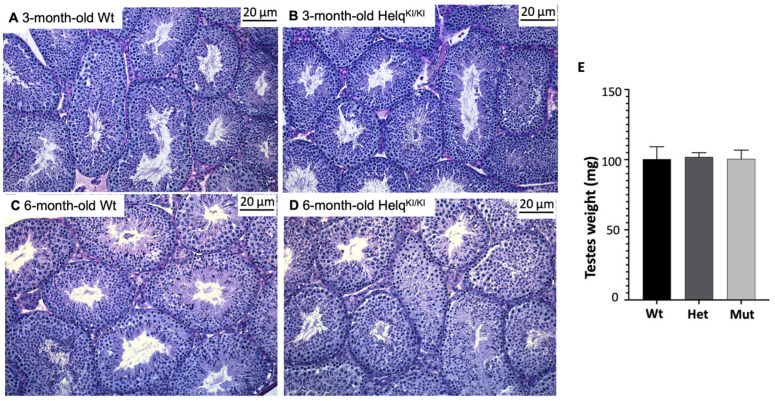

3.4. Testicular Weight and Morphology Are Normal in HelqKI/KI Mice

Given that Helq knock-out mice have smaller testes with regions of atrophied seminiferous tubules [22], we analysed the testicular weight and morphology in knock-in mice. There were no significant differences in the testes weights between the HelqKI/KI knock-in and the Het/Wt mice. The testes sections of 3-month-old and 6-month-old male mice were stained with PAS. Morphological assessment results revealed no apparent difference between HelqKI/KI, het and Wt mice at 3 months and 6 months of age (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Morphological analysis of HelqKI/KI testes. Histological study of PAS-stained testes from 3-month-old (A,B) and 6-month-old (C,D) mice did not show any differences between HelqKI/KI and Het/Wt mice. There was no statistically significant difference in the weight of testes between HelqKI/KI and Het/Wt mice (E) (n = 36) (ANOVA p > 0.05).

3.5. Longevity Study for Survival/Tumorigenesis Analysis

Since Helq knock-out in mice resulted in increased tumour formation such as ovarian tumours and pituitary tumours [22], we assessed any potential tumour development in HelqKI/KI mice. A substantial number of HelqKI/KI mice (n = 360; 60 mice per sex, per genotype) were assigned to a longevity study group, and their gonads were closely monitored for the development of tumours over a period of twelve months. The results did not reveal any evidence of susceptibility to tumours in the Helq mice.

4. Discussion

4.1. Missense Variants in HELQ Are a Possible Cause of POI

In the present study, we employed whole-exome sequencing to discover a novel homozygous missense variant in the HELQ gene (c.596 A>C; p.Gln199Pro) in an isolated POI patient diagnosed with primary amenorrhea. This variant affects a residue that is highly conserved from archaea to eukaryotes suggesting that changes at this site are likely to be detrimental to protein function. It is predicted to be disease-causing and damaging by multiple in silico algorithms. The HELQ gene is a strong candidate POI gene based on studies in mice demonstrating oocyte depletion and infertility in Helq knock-out mice. This variant was curated as a Class 3A variant of uncertain significance (VUS) according to modified ACMG criteria [79]. In order to examine the potential implication of this variant on the pathogenicity of POI, additional evidence was sought to establish whether the variant was deleterious. To this end, we generated a CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knock-in mouse model. Despite conservation of this residue and the predicted deleterious nature of the variant by online algorithms, the mouse model harbouring the equivalent of the patient’s HELQ variant (p.Gln199Pro) failed to recapitulate the POI phenotype.

Research using mouse models has provided significant insights into the role of HELQ in male and female reproduction. These studies have shed light on the involvement of HELQ in meiotic processes, such as meiotic double-strand break repair and meiotic checkpoint activation. HELQ has been implicated in germ cell maintenance, ultimately contributing to the regulation of both male and female fertility [22,80]. Previous studies have documented that Helq knock-out male mice exhibit hypogonadism associated with a decrease or loss of spermatogonia. Correspondingly, female mice deficient in Helq had atrophied ovaries and a diminished number of follicles resembling human POI [22,23]. Multiple lines of evidence have consistently supported a strong association between genes implicated in meiosis and DNA repair and the development of POI [21,81]. However, knowledge regarding the impact of HELQ variants in POI patients is based on a limited number of studies. HELQ was first identified to be related to age at natural menopause in humans through a comprehensive meta-analysis of 22 genome-wide association studies involving women of European descent. This finding could highlight the potential involvement of HELQ in female reproduction, given that menopause represents the cessation of ovarian function and serves as a reliable indicator of ovarian aging in women [25]. In contrast, a subsequent study failed to identify any plausible causative variants in the HELQ after sequencing all 18 exons and exon–intron boundaries of HELQ in a cohort of 192 Chinese Han women with POI [26]. Furthermore, two known single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), rs1494961 and rs2047210, identified within the HELQ gene in this study, revealed no significant disparity in allele frequency between patients and controls [26]. A recent study has identified a homozygous truncated variant in exon 17 of HELQ (c.3095delA; p.Tyr1032SerfsTer4) using WES in a POI patient who presented with secondary amenorrhea and born to consanguineous Moroccan parents [27]. Chromosomal studies in the patient’s lymphocytes revealed spontaneous chromosomal breaks enhanced by mitomycin. Because only one POI patient has been identified with biallelic variants in HELQ, it remains a gene of uncertain significance for POI pathology. Identifying additional POI patients with disruption to this gene will consolidate HELQ as a bona fide POI causative gene. Given that the variant in our patient was a Class 3A VUS, we sought additional support by disease modelling to determine its causal role in POI.

4.2. HELQ Missense Variant Remains a Variant of Uncertain Significance

Despite the previous Helq knock-out studies, the Helq knock-in mice harbouring the HELQ variant (p.Gln161Pro equivalent to human, p.Gln199Pro) found in our POI patient does not recapitulate the POI phenotype. Both male and female HelqKI/KI mice exhibited fertility levels similar to those of Wt mice. Our assessment of ovarian and testicular tissue through histological analysis revealed no apparent differences between the HelqKI/KI and Wt mice. The biallelic nature of the HELQ gene variant combined with deleterious in silico predictions and high evolutionary conservation led to this variant being considered of high clinical relevance. However, our mouse model failed to provide the functional support necessary to promote this HELQ gene variant to a likely pathogenic status. This could be due to (1) the variant being an incidental finding and unrelated to POI pathogenicity or (2) the failure of the mouse model to functionally mimic the human scenario. Mouse models, while valuable tools for studying human diseases, may not fully mirror the complexity and intricacies of human biology [82,83,84]. Despite their genetic similarity to humans, they often face criticism for their limited ability to accurately recapitulate human disease phenotypes [82]. Furthermore, it is crucial to consider the potential limitations of the knock-in strategy and the specific genetic context of the variant within the mouse genome. The introduction of a single variant in isolation may not fully capture the genetic interactions and regulatory mechanisms present in the human genetic background [85,86]. Mouse strains used in research studies often have different genetic backgrounds, which can influence the manifestation and interpretation of human variants, a factor that is sometimes overlooked. These genetic differences can interact with the introduced variant and produce unpredictable functional consequences of the variant due to the dissimilarities in protein structure, expression patterns, or compensatory mechanisms [82,87,88]. A previous report has highlighted molecular differences within mice of 129 substrains [89]. Similarly, the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC) has shown that all commonly used C57BL/6 strains, in particular the substrains C57BL/6J (used here) and C57BL/6N, are not genetically identical and exhibit phenotypic differences [90].

Furthermore, DNA repair variants appear to exhibit increased variability dependent on the genetic background. For instance, a previous study demonstrated that a mouse knock-in model of DMC1 M200V, harbouring a human infertility allele of the meiotic recombinase DMC1, did not affect fertility in mice [91]. Despite the fact that the DMC1 variant (M200V) was found pathogenic in an African woman with POI [55], both Dmc1M200V/M200V female and male mice did not exhibit any abnormalities in their gonads which was similar to the HelqKI/KI mice phenotype observed in our study. By contrast, subsequent research indicated a detrimental effect of this DMC1 variant in biochemical assays, and the introduction of the corresponding variant in the Schizosaccharomyces pombe dmc1 ortholog resulted in a significant decrease in meiotic recombination [92]. This underscores the significance of utilising alternative approaches to validate the variants associated with human infertility. Additionally, given that POI is a heterogeneous disorder with various genetic causes [2], the genetic background of mouse models used to study POI may not fully represent the diverse genetic landscape observed in human patients [39]. Identified POI-related gene variants cannot be completely dismissed or ruled out as there may be intergenic interactions that might influence their effects [15].

A recent study highlighted a divergence in the functioning of DMC1 between mice and humans. A pathogenic homozygous frameshift DMC1 variant (p.Glu10Asnfs*31) was identified in two sisters from a Chinese family who exhibited diminished ovarian reserve with few antral follicles but successful retrieval of metaphase II oocytes from one sister. In contrast, female Dmc1−/− knock-out mice demonstrated a complete failure of follicle development [93]. Moreover, previous studies in mice showed sexual dimorphism as a consequence of knocking out Mcm9, a DNA damage repair gene, in mice. Although the female Mcm9 knock-out mice were sterile due to a lack of oocytes, male knock-outs were fertile with fewer germ cells compared to their Wt counterparts [94,95]. By contrast, both male and female humans are infertile if the MCM9 gene is disrupted [30,96]. These studies highlight some of the limitations when using meiosis and DNA repair genes in mouse models when trying to recapitulate gonadal development processes.

A discrepancy between mouse models and human infertility can result from divergent roles of the affected genes but also from different effects of variant residues in mouse vs human proteins. For example, although Spata16 knock-out causes infertility in male mice, mice with a knock-in of a variant that segregated with male infertility in a pedigree with three affected individuals [97] retained fertility [98]. It remains possible that the p.Gln161Pro Helq variant does not disrupt mouse Helq function while the p.Gln199Pro HELQ variant may still be deleterious to human HELQ.

To explore the wider implications of the Helq variant on long-term health, specifically regarding cancer predisposition, we monitored HelqKI/KI mice for a duration of 12 months. Our primary focus was to monitor for the development of tumours, particularly in the gonad. Unlike Helq knock-out mice, the Q161P knock-in mice had no significant tumour development compared to the Wt mice. Although HELQ-deficient human and mouse cells are more sensitive to DNA interstrand crosslinks (ICLs)-inducing agents, suggesting a role for HELQ in the processing of ICLs and tumour suppression [18,22,80], the role of HELQ in cancer development requires further elucidation. For example, screening of 185 Finnish breast or ovarian cancer families for germline variation in the HELQ gene showed no likely causative variants. Likewise, studying the association of common variation in the HELQ gene with breast and ovarian cancer risk through haplotype analysis did not show any differences between affected cases and healthy population controls [99]. We currently lack a comprehensive understanding of the role of HELQ in cancer development. Notably, neither our genetically modified mice nor the patient under study exhibited signs of cancer. The lack of cancer-related findings in our study does not imply a discrepancy; instead, it underscores the complexity of the involvement of HELQ in cancer, which remains an area requiring further investigation.

4.3. Functional Validation Is Important for Human Variant Curation

Curating variants as pathogenic directly without functional/in vivo validation can carry certain risks and limitations. Without disease modelling, the functional consequences of variants may remain uncertain. Computational algorithms play a valuable role in estimating the potential impact of a variant on protein function. However, relying exclusively on these algorithms as an endpoint during the validation process is discouraged due to their limited reliability [100,101]. Therefore, to better understand HELQ variant consequences in DNA repair pathways and their relevance to POI pathogenicity, it is crucial to combine insights from mouse models with human studies. Given that only one POI patient has previously been reported with biallelic variants in HELQ, it remains a gene variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in terms of potential POI pathogenicity. The identification of additional variants in independent families will strengthen the evidence that HELQ gene variants, particularly missense variants, can be causal. These studies could encompass in vitro investigations such as measurement of the stability of variant HELQ or its capacity to support DNA damage repair and the use of patient-derived cells, particularly patient lymphoblasts, which can be tested for their sensitivity to DNA damage. Evidence of an increased sensitivity to DNA damage would support a causal role of the HELQ variant. Unfortunately, such cell types were not available in the current study. By integrating various approaches, we can bridge the existing gaps and enhance our understanding of how HELQ deficiency affects DNA damage repair and reproductive dysfunction in humans.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have identified a homozygous missense variant in HELQ (p.Gln199Pro) in a woman with POI presenting as primary amenorrhea. A Helq knock-in mouse model failed to recapitulate the POI phenotype and thus the HELQ gene variant remains a VUS. Relying solely on in silico predictions is insufficient to understand the true impact of variants on pathogenicity. Although the Helq mouse model failed to support pathogenicity of this novel HELQ gene variant, the limitations of mouse models such as incomplete conservation and inability to represent the human genetic background may have masked the phenotypic consequences. Further research employing robust and complementary functional validation approaches including additional patients with independent HELQ variants is necessary to establish a more comprehensive understanding of the role of HELQ variants in POI and to facilitate patient management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.J.T. and A.H.S.; Methodology, S.B., E.J.T., A.D.B., D.W., R.S., G.R., J.v.d.B. and A.J.K.; Investigation and Analysis, S.B., A.D.B., R.S., K.M.B., M.A.-J., A.J.K., A.L., S.J., K.L.A., D.W., A.H.S. and E.J.T.; Resources, E.J.T. and P.T.; Data Curation, S.B., E.J.T. and K.M.B.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, S.B. and E.J.T.; Writing—Review & Editing, S.B., E.J.T., A.H.S., D.W., M.A.-J., S.J. and A.L.; Supervision, E.J.T. and A.H.S.; Project Administration, G.R., J.v.d.B. and K.L.A.; Funding Acquisition, A.H.S. and E.J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne (HREC/22073; 6 March 2018). The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee (AEC) of the Royal Children’s Hospital (A912; 19 March 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) program grant (1074258 to Andrew H. Sinclair), NHMRC fellowships (1054432 to Elena J. Tucker, 1126995 to Rajini Sreenivasan, 1062854 to Andrew H. Sinclair), a Suzi Carp postdoctoral scholarship (to Elena J. Tucker), a CHU Rennes grant (Appel à Projets Innovations 2019 to Sylvie Jaillard), Melbourne International Research Scholarship and David Danks PhD Top-up Scholarship (Shabnam Bakhshalizadeh). The research conducted at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute was supported by the Victorian government’s operational infrastructure support program. The generation of CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in mice used in this study was supported by Phenomics Australia and the Australian Government through the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS) program.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Li M., Zhu Y., Wei J., Chen L., Chen S., Lai D. The global prevalence of premature ovarian insufficiency: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Climacteric. 2023;26:95–102. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2022.2153033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tucker E.J., Grover S.R., Bachelot A., Touraine P., Sinclair A.H. Premature Ovarian Insufficiency: New Perspectives on Genetic Cause and Phenotypic Spectrum. Endocr. Rev. 2016;37:609–635. doi: 10.1210/er.2016-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen M., Jiang H., Zhang C. Selected Genetic Factors Associated with Primary Ovarian Insufficiency. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24:4423. doi: 10.3390/ijms24054423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goswami D., Conway G.S. Premature ovarian failure. Horm. Res. 2007;68:196–202. doi: 10.1159/000102537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qin Y., Jiao X., Simpson J.L., Chen Z.J. Genetics of primary ovarian insufficiency: New developments and opportunities. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2015;21:787–808. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tucker E.J., Jaillard S., Sinclair A.H. Human Reproductive and Prenatal Genetics. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2023. Update on the genetics and genomics of premature ovarian insufficiency; pp. 439–461. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartshorne G.M., Lyrakou S., Hamoda H., Oloto E., Ghafari F. Oogenesis and cell death in human prenatal ovaries: What are the criteria for oocyte selection? Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2009;15:805–819. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gap055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker T. A quantitative and cytological study of germ cells in human ovaries. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 1963;158:417–433. doi: 10.1097/00006254-196408000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pepling M.E. From primordial germ cell to primordial follicle: Mammalian female germ cell development. Genesis. 2006;44:622–632. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pepling M.E., Spradling A.C. Mouse ovarian germ cell cysts undergo programmed breakdown to form primordial follicles. Dev. Biol. 2001;234:339–351. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerr J.B., Hutt K.J., Michalak E.M., Cook M., Vandenberg C.J., Liew S.H., Bouillet P., Mills A., Scott C.L., Findlay J.K. DNA damage-induced primordial follicle oocyte apoptosis and loss of fertility require TAp63-mediated induction of Puma and Noxa. Mol. Cell. 2012;48:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashwood-Smith M., Edwards R. Genetics and human conception: DNA repair by oocytes. MHR Basic Sci. Reprod. Med. 1996;2:46–51. doi: 10.1093/molehr/2.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tilly J.L. Commuting the death sentence: How oocytes strive to survive. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:838–848. doi: 10.1038/35099086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiao X., Ke H., Qin Y., Chen Z.-J. Molecular genetics of premature ovarian insufficiency. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2018;29:795–807. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veitia R.A. Primary ovarian insufficiency, meiosis and DNA repair. Biomed. J. 2020;43:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baudat F., Imai Y., De Massy B. Meiotic recombination in mammals: Localization and regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14:794–806. doi: 10.1038/nrg3573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jasin M., Rothstein R. Repair of strand breaks by homologous recombination. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013;5:a012740. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takata K.-i., Reh S., Tomida J., Person M.D., Wood R.D. Human DNA helicase HELQ participates in DNA interstrand crosslink tolerance with ATR and RAD51 paralogs. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2338. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCaffrey R., St Johnston D., González-Reyes A. Drosophila mus301/spindle-C encodes a helicase with an essential role in double-strand DNA break repair and meiotic progression. Genetics. 2006;174:1273–1285. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.058289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ward J.D., Muzzini D.M., Petalcorin M.I., Martinez-Perez E., Martin J.S., Plevani P., Cassata G., Marini F., Boulton S.J. Overlapping mechanisms promote postsynaptic RAD-51 filament disassembly during meiotic double-strand break repair. Mol. Cell. 2010;37:259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tucker E.J., Bell K.M., Robevska G., van den Bergen J., Ayers K.L., Listyasari N., Faradz S.M., Dulon J., Bakhshalizadeh S., Sreenivasan R., et al. Meiotic genes in premature ovarian insufficiency: Variants in HROB and REC8 as likely genetic causes. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2022;30:219–228. doi: 10.1038/s41431-021-00977-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adelman C.A., Lolo R.L., Birkbak N.J., Murina O., Matsuzaki K., Horejsi Z., Parmar K., Borel V., Skehel J.M., Stamp G. HELQ promotes RAD51 paralogue-dependent repair to avert germ cell loss and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2013;502:381–384. doi: 10.1038/nature12565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luebben S.W., Kawabata T., Akre M.K., Lee W.L., Johnson C.S., O’Sullivan M.G., Shima N. Helq acts in parallel to Fancc to suppress replication-associated genome instability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:10283–10297. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marini F., Kim N., Schuffert A., Wood R.D. POLN, a nuclear PolA family DNA polymerase homologous to the DNA cross-link sensitivity protein Mus308. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:32014–32019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stolk L., Perry J.R., Chasman D.I., He C., Mangino M., Sulem P., Barbalic M., Broer L., Byrne E.M., Ernst F. Meta-analyses identify 13 loci associated with age at menopause and highlight DNA repair and immune pathways. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:260–268. doi: 10.1038/ng.1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang W., Zhao S., Zhuang L., Li W., Qin Y., Chen Z.-J. The screening of HELQ gene in Chinese patients with premature ovarian failure. Reprod. BioMed. Online. 2015;31:573–576. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heddar A., Ogur C., Da Costa S., Braham I., Billaud-Rist L., Findikli N., Beneteau C., Reynaud R., Mahmoud K., Legrand S. Genetic landscape of a large cohort of Primary Ovarian Insufficiency: New genes and pathways and implications for personalized medicine. EBioMedicine. 2022;84:104246. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.AlAsiri S., Basit S., Wood-Trageser M.A., Yatsenko S.A., Jeffries E.P., Surti U., Ketterer D.M., Afzal S., Ramzan K., Haque M.F.-U. Exome sequencing reveals MCM8 mutation underlies ovarian failure and chromosomal instability. J. Clin. Investig. 2015;125:258–262. doi: 10.1172/JCI78473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouali N., Francou B., Bouligand J., Imanci D., Dimassi S., Tosca L., Zaouali M., Mougou S., Young J., Saad A. New MCM8 mutation associated with premature ovarian insufficiency and chromosomal instability in a highly consanguineous Tunisian family. Fertil. Steril. 2017;108:694–702. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Desai S., Wood-Trageser M., Matic J., Chipkin J., Jiang H., Bachelot A., Dulon J., Sala C., Barbieri C., Cocca M. MCM8 and MCM9 nucleotide variants in women with primary ovarian insufficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017;102:576–582. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dou X., Guo T., Li G., Zhou L., Qin Y., Chen Z.-J. Minichromosome maintenance complex component 8 mutations cause primary ovarian insufficiency. Fertil. Steril. 2016;106:1485–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heddar A., Beckers D., Fouquet B., Roland D., Misrahi M. A novel phenotype combining primary ovarian insufficiency growth retardation and pilomatricomas with MCM8 mutation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020;105:1973–1982. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y.X., He W.B., Xiao W.J., Meng L.L., Tan C., Du J., Lu G.X., Lin G., Tan Y.Q. Novel loss-of-function mutation in MCM8 causes premature ovarian insufficiency. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2020;8:e1165. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fauchereau F., Shalev S., Chervinsky E., Beck-Fruchter R., Legois B., Fellous M., Caburet S., Veitia R.A. A non-sense MCM9 mutation in a familial case of primary ovarian insufficiency. Clin. Genet. 2016;89:603–607. doi: 10.1111/cge.12736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldberg Y., Halpern N., Hubert A., Adler S.N., Cohen S., Plesser-Duvdevani M., Pappo O., Shaag A., Meiner V. Mutated MCM9 is associated with predisposition to hereditary mixed polyposis and colorectal cancer in addition to primary ovarian failure. Cancer Genet. 2015;208:621–624. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo T., Zheng Y., Li G., Zhao S., Ma J., Qin Y. Novel pathogenic mutations in minichromosome maintenance complex component 9 (MCM9) responsible for premature ovarian insufficiency. Fertil. Steril. 2020;113:845–852. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wood-Trageser M.A., Gurbuz F., Yatsenko S.A., Jeffries E.P., Kotan L.D., Surti U., Ketterer D.M., Matic J., Chipkin J., Jiang H., et al. MCM9 mutations are associated with ovarian failure, short stature, and chromosomal instability. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;95:754–762. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang X., Touraine P., Desai S., Humphreys G., Jiang H., Yatsenko A., Rajkovic A. Gene variants identified by whole-exome sequencing in 33 French women with premature ovarian insufficiency. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2019;36:39–45. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1349-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bouilly J., Beau I., Barraud S., Bernard V., Azibi K., Fagart J., Fèvre A., Todeschini A.L., Veitia R.A., Beldjord C. Identification of multiple gene mutations accounts for a new genetic architecture of primary ovarian insufficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016;101:4541–4550. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ren Y., Diao F., Katari S., Yatsenko S., Jiang H., Wood-Trageser M.A., Rajkovic A. Functional study of a novel missense single-nucleotide variant of NUP 107 in two daughters of M exican origin with premature ovarian insufficiency. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2018;6:276–281. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caburet S., Arboleda V.A., Llano E., Overbeek P.A., Barbero J.L., Oka K., Harrison W., Vaiman D., Ben-Neriah Z., García-Tuñón I. Mutant cohesin in premature ovarian failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:943–949. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J., Zhang W., Jiang H., Wu B.L., Primary Ovarian Insufficiency C. Mutations in HFM1 in recessive primary ovarian insufficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:972–974. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1310150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lacombe A., Lee H., Zahed L., Choucair M., Muller J.-M., Nelson S.F., Salameh W., Vilain E. Disruption of POF1B binding to nonmuscle actin filaments is associated with premature ovarian failure. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;79:113–119. doi: 10.1086/505406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ledig S., Preisler-Adams S., Morlot S., Liehr T., Wieacker P. Premature ovarian failure caused by a heterozygous missense mutation in POF1B and a reciprocal translocation 46, X, t (X; 3)(q21. 1; q21. 3) Sex. Dev. 2015;9:86–90. doi: 10.1159/000373906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gorsi B., Hernandez E., Moore M.B., Moriwaki M., Chow C.Y., Coelho E., Taylor E., Lu C., Walker A., Touraine P. Causal and candidate gene variants in a large cohort of women with primary ovarian insufficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022;107:685–714. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jolly A., Bayram Y., Turan S., Aycan Z., Tos T., Abali Z.Y., Hacihamdioglu B., Coban Akdemir Z.H., Hijazi H., Bas S., et al. Exome Sequencing of a Primary Ovarian Insufficiency Cohort Reveals Common Molecular Etiologies for a Spectrum of Disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019;104:3049–3067. doi: 10.1210/jc.2019-00248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Agha A.E., Ahmed I.A., Nuebel E., Moriwaki M., Moore B., Peacock K.A., Mosbruger T., Neklason D.W., Jorde L.B., Yandell M. Primary ovarian insufficiency and azoospermia in carriers of a homozygous PSMC3IP stop gain mutation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018;103:555–563. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zangen D., Kaufman Y., Zeligson S., Perlberg S., Fridman H., Kanaan M., Abdulhadi-Atwan M., Libdeh A.A., Gussow A., Kisslov I. XX ovarian dysgenesis is caused by a PSMC3IP/HOP2 mutation that abolishes coactivation of estrogen-driven transcription. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;89:572–579. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carlosama C., Elzaiat M., Patiño L.C., Mateus H.E., Veitia R.A., Laissue P. A homozygous donor splice-site mutation in the meiotic gene MSH4 causes primary ovarian insufficiency. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017;26:3161–3166. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guo T., Zhao S., Zhao S., Chen M., Li G., Jiao X., Wang Z., Zhao Y., Qin Y., Gao F. Mutations in MSH5 in primary ovarian insufficiency. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017;26:1452–1457. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Macaisne N., Touzon M.S., Rajkovic A., Yanowitz J.L. Modeling primary ovarian insufficiency-associated loci in C. elegans identifies novel pathogenic allele of MSH5. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2022;39:1255–1260. doi: 10.1007/s10815-022-02494-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qin Y., Guo T., Li G., Tang T.-S., Zhao S., Jiao X., Gong J., Gao F., Guo C., Simpson J.L. CSB-PGBD3 mutations cause premature ovarian failure. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eskenazi S., Bachelot A., Hugon-Rodin J., Plu-Bureau G., Gompel A., Catteau-Jonard S., Molina-Gomes D., Dewailly D., Dodé C., Christin-Maitre S. Next generation sequencing should be proposed to every woman with “idiopathic” primary ovarian insufficiency. J. Endocr. Soc. 2021;5:bvab032. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvab032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He W.-B., Tu C.-F., Liu Q., Meng L.-L., Yuan S.-M., Luo A.-X., He F.-S., Shen J., Li W., Du J. DMC1 mutation that causes human non-obstructive azoospermia and premature ovarian insufficiency identified by whole-exome sequencing. J. Med. Genet. 2018;55:198–204. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mandon-Pépin B., Touraine P., Kuttenn F., Derbois C., Rouxel A., Matsuda F., Nicolas A., Cotinot C., Fellous M. Genetic investigation of four meiotic genes in women with premature ovarian failure. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2008;158:107–115. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Caburet S., Todeschini A.-L., Petrillo C., Martini E., Farran N.D., Legois B., Livera G., Younis J.S., Shalev S., Veitia R.A. A truncating MEIOB mutation responsible for familial primary ovarian insufficiency abolishes its interaction with its partner SPATA22 and their recruitment to DNA double-strand breaks. EBioMedicine. 2019;42:524–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.03.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Y., Liu L., Tan C., Meng G., Meng L., Nie H., Du J., Lu G.-X., Lin G., He W.-B. Novel MEIOB variants cause primary ovarian insufficiency and non-obstructive azoospermia. Front. Genet. 2022;13:936264. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.936264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.He W.-B., Tan C., Zhang Y.-X., Meng L.-L., Gong F., Lu G.-X., Lin G., Du J., Tan Y.-Q. Homozygous variants in SYCP2L cause premature ovarian insufficiency. J. Med. Genet. 2021;58:168–172. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2019-106789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Vries L., Behar D.M., Smirin-Yosef P., Lagovsky I., Tzur S., Basel-Vanagaite L. Exome sequencing reveals SYCE1 mutation associated with autosomal recessive primary ovarian insufficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;99:E2129–E2132. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Felipe-Medina N., Caburet S., Sánchez-Sáez F., Condezo Y.B., De Rooij D.G., Gómez-h L., Garcia-Valiente R., Todeschini A.L., Duque P., Sánchez-Martin M.A. A missense in HSF2BP causing primary ovarian insufficiency affects meiotic recombination by its novel interactor C19ORF57/BRME1. eLife. 2020;9:e56996. doi: 10.7554/eLife.56996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li S., Xu W., Xu B., Gao S., Zhang Q., Qin Y., Guo T. Pathogenic variations of homologous recombination gene HSF2BP identified in sporadic patients with premature ovarian insufficiency. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022;9:768123. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.768123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tucker E.J., Jaillard S., Grover S.R., van den Bergen J., Robevska G., Bell K.M., Sadedin S., Hanna C., Dulon J., Touraine P., et al. TP63-truncating variants cause isolated premature ovarian insufficiency. Hum. Mutat. 2019;40:886–892. doi: 10.1002/humu.23744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tucker E.J., Gutfreund N., Belaud-Rotureau M.A., Gilot D., Brun T., Kline B.L., Bell K.M., Domin-Bernhard M., Théard C., Touraine P. Dominant TP63 missense variants lead to constitutive activation and premature ovarian insufficiency. Hum. Mutat. 2022;43:1443–1453. doi: 10.1002/humu.24432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McGlacken-Byrne S.M., Le Quesne Stabej P., Del Valle I., Ocaka L., Gagunashvili A., Crespo B., Moreno N., James C., Bacchelli C., Dattani M.T. ZSWIM7 is associated with human female meiosis and familial primary ovarian insufficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022;107:e254–e263. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yatsenko S.A., Gurbuz F., Topaloglu A.K., Berman A.J., Martin P.-M., Rodríguez-Escribà M., Qin Y., Rajkovic A. Pathogenic variants in ZSWIM7 cause primary ovarian insufficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022;107:e2359–e2364. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgac090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fouquet B., Pawlikowska P., Caburet S., Guigon C., Mäkinen M., Tanner L., Hietala M., Urbanska K., Bellutti L., Legois B. A homozygous FANCM mutation underlies a familial case of non-syndromic primary ovarian insufficiency. eLife. 2017;6:e30490. doi: 10.7554/eLife.30490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jaillard S., Bell K., Akloul L., Walton K., McElreavy K., Stocker W.A., Beaumont M., Harrisson C., Jaaskelainen T., Palvimo J.J., et al. New insights into the genetic basis of premature ovarian insufficiency: Novel causative variants and candidate genes revealed by genomic sequencing. Maturitas. 2020;141:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang Y., Guo T., Liu R., Ke H., Xu W., Zhao S., Qin Y. FANCL gene mutations in premature ovarian insufficiency. Hum. Mutat. 2020;41:1033–1041. doi: 10.1002/humu.23997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang X., Zhang X., Jiao J., Zhang F., Pan Y., Wang Q., Chen Q., Cai B., Tang S., Zhou Z. Rare variants in FANCA induce premature ovarian insufficiency. Hum. Genet. 2019;138:1227–1236. doi: 10.1007/s00439-019-02059-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang Y.-X., Li H.-Y., He W.-B., Tu C., Du J., Li W., Lu G.-X., Lin G., Yang Y., Tan Y.-Q. XRCC2 mutation causes premature ovarian insufficiency as well as non-obstructive azoospermia in humans. Clin. Genet. 2019;95:442–443. doi: 10.1111/cge.13475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Faridi R., Rehman A.U., Morell R.J., Friedman P.L., Demain L., Zahra S., Khan A.A., Tohlob D., Assir M.Z., Beaman G. Mutations of SGO2 and CLDN14 collectively cause coincidental Perrault syndrome. Clin. Genet. 2017;91:328–332. doi: 10.1111/cge.12867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smirin-Yosef P., Zuckerman-Levin N., Tzur S., Granot Y., Cohen L., Sachsenweger J., Borck G., Lagovsky I., Salmon-Divon M., Wiesmüller L. A biallelic mutation in the homologous recombination repair gene SPIDR is associated with human gonadal dysgenesis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017;102:681–688. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Luo W., Guo T., Li G., Liu R., Zhao S., Song M., Zhang L., Wang S., Chen Z.-J., Qin Y. Variants in homologous recombination genes EXO1 and RAD51 related with premature ovarian insufficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020;105:e3566–e3574. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou Y., Qin Y., Qin Y., Xu B., Guo T., Ke H., Chen M., Zhang L., Han F., Li Y. Wdr62 is involved in female meiotic initiation via activating JNK signaling and associated with POI in humans. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tucker E.J., Grover S.R., Robevska G., van den Bergen J., Hanna C., Sinclair A.H. Identification of variants in pleiotropic genes causing “isolated” premature ovarian insufficiency: Implications for medical practice. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2018;26:1319–1328. doi: 10.1038/s41431-018-0140-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sadedin S.P., Dashnow H., James P.A., Bahlo M., Bauer D.C., Lonie A., Lunke S., Macciocca I., Ross J.P., Siemering K.R., et al. Cpipe: A shared variant detection pipeline designed for diagnostic settings. Genome Med. 2015;7:68. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0191-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Polanco J.C., Wilhelm D., Davidson T.-L., Knight D., Koopman P. Sox10 gain-of-function causes XX sex reversal in mice: Implications for human 22q-linked disorders of sex development. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:506–516. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Venselaar H., Te Beek T.A., Kuipers R.K., Hekkelman M.L., Vriend G. Protein structure analysis of mutations causing inheritable diseases. An e-Science approach with life scientist friendly interfaces. BMC Bioinform. 2010;11:548. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Richards S., Aziz N., Bale S., Bick D., Das S., Gastier-Foster J., Grody W.W., Hegde M., Lyon E., Spector E. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–423. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Han X., Zhao L., Li X. HELQ in cancer and reproduction. Neoplasma. 2016;63:825–835. doi: 10.4149/neo_2016_601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Biswas L., Tyc K., El Yakoubi W., Morgan K., Xing J., Schindler K. Meiosis interrupted: The genetics of female infertility via meiotic failure. Reproduction. 2021;161:R13–R35. doi: 10.1530/REP-20-0422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Justice M.J., Dhillon P. Using the mouse to model human disease: Increasing validity and reproducibility. Dis. Models Mech. 2016;9:101–103. doi: 10.1242/dmm.024547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Perlman R.L. Mouse models of human disease: An evolutionary perspective. Evol. Med. Public Health. 2016;2016:170–176. doi: 10.1093/emph/eow014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wall R.J., Shani M. Are animal models as good as we think? Theriogenology. 2008;69:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2007.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pound P., Ritskes-Hoitinga M. Is it possible to overcome issues of external validity in preclinical animal research? Why most animal models are bound to fail. J. Transl. Med. 2018;16:304. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1678-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Seok J., Warren H.S., Cuenca A.G., Mindrinos M.N., Baker H.V., Xu W., Richards D.R., McDonald-Smith G.P., Gao H., Hennessy L. Inflammation and Host Response to Injury, Large Scale Collaborative Research Program. Genomic responses in mouse models poorly mimic human inflammatory diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:3507–3512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222878110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Birling M.-C., Herault Y., Pavlovic G. Modeling human disease in rodents by CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Mamm. Genome. 2017;28:291–301. doi: 10.1007/s00335-017-9703-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sittig L.J., Carbonetto P., Engel K.A., Krauss K.S., Barrios-Camacho C.M., Palmer A.A. Genetic background limits generalizability of genotype-phenotype relationships. Neuron. 2016;91:1253–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Simpson E.M., Linder C.C., Sargent E.E., Davisson M.T., Mobraaten L.E., Sharp J.J. Genetic variation among 129 substrains and its importance for targeted mutagenesis in mice. Nat. Genet. 1997;16:19–27. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Simon M.M., Greenaway S., White J.K., Fuchs H., Gailus-Durner V., Wells S., Sorg T., Wong K., Bedu E., Cartwright E.J. A comparative phenotypic and genomic analysis of C57BL/6J and C57BL/6N mouse strains. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R82. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-7-r82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tran T.N., Schimenti J.C. A putative human infertility allele of the meiotic recombinase DMC1 does not affect fertility in mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018;27:3911–3918. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hikiba J., Hirota K., Kagawa W., Ikawa S., Kinebuchi T., Sakane I., Takizawa Y., Yokoyama S., Mandon-Pepin B., Nicolas A. Structural and functional analyses of the DMC1-M200V polymorphism found in the human population. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:4181–4190. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cao D., Shi F., Guo C., Liu Y., Lin Z., Zhang J., Li R.H.W., Yao Y., Liu K., Ng E.H.Y. A pathogenic DMC1 frameshift mutation causes nonobstructive azoospermia but not primary ovarian insufficiency in humans. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2021;27:gaab058. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaab058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hartford S.A., Luo Y., Southard T.L., Min I.M., Lis J.T., Schimenti J.C. Minichromosome maintenance helicase paralog MCM9 is dispensible for DNA replication but functions in germ-line stem cells and tumor suppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:17702–17707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113524108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lutzmann M., Grey C., Traver S., Ganier O., Maya-Mendoza A., Ranisavljevic N., Bernex F., Nishiyama A., Montel N., Gavois E. MCM8-and MCM9-deficient mice reveal gametogenesis defects and genome instability due to impaired homologous recombination. Mol. Cell. 2012;47:523–534. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Potorac I., Laterre M., Malaise O., Nechifor V., Fasquelle C., Colleye O., Detrembleur N., Verdin H., Symoens S., De Baere E. The Role of MCM9 in the Etiology of Sertoli Cell-Only Syndrome and Premature Ovarian Insufficiency. J. Clin. Med. 2023;12:990. doi: 10.3390/jcm12030990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dam A.H., Koscinski I., Kremer J.A., Moutou C., Jaeger A.-S., Oudakker A.R., Tournaye H., Charlet N., Lagier-Tourenne C., van Bokhoven H. Homozygous mutation in SPATA16 is associated with male infertility in human globozoospermia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:813–820. doi: 10.1086/521314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fujihara Y., Oji A., Larasati T., Kojima-Kita K., Ikawa M. Human globozoospermia-related gene Spata16 is required for sperm formation revealed by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mouse models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:2208. doi: 10.3390/ijms18102208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pelttari L.M., Kinnunen L., Kiiski J.I., Khan S., Blomqvist C., Aittomäki K., Nevanlinna H. Screening of HELQ in breast and ovarian cancer families. Fam. Cancer. 2016;15:19–23. doi: 10.1007/s10689-015-9838-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Miosge L.A., Field M.A., Sontani Y., Cho V., Johnson S., Palkova A., Balakishnan B., Liang R., Zhang Y., Lyon S. Comparison of predicted and actual consequences of missense mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E5189–E5198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511585112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang T., Bu C.H., Hildebrand S., Jia G., Siggs O.M., Lyon S., Pratt D., Scott L., Russell J., Ludwig S. Probability of phenotypically detectable protein damage by ENU-induced mutations in the Mutagenetix database. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:441. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02806-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.