Abstract

Periodontitis drives irreversible destruction of periodontal tissue and is prone to exacerbating inflammatory disorders. Systemic immunomodulatory management continues to be an attractive approach in periodontal care, particularly within the context of ‘predictive, preventive, and personalized’ periodontics. The present study incorporated genetic proxies identified through genome-wide association studies for circulating immune cells and periodontitis into a comprehensive Mendelian randomization (MR) framework. Univariable MR, multivariable MR, subgroup analysis, reverse MR, and Bayesian model averaging (MR-BMA) were utilized to investigate the causal relationships. Furthermore, transcriptome-wide association study and colocalization analysis were deployed to pinpoint the underlying genes. Consequently, the MR study indicated a causal association between circulating neutrophils, natural killer T cells, plasmacytoid dendritic cells, and an elevated risk of periodontitis. MR-BMA analysis revealed that neutrophils were the primary contributors to periodontitis. The high-confidence genes S100A9 and S100A12, located on 1q21.3, could potentially serve as immunomodulatory targets for neutrophil-mediated periodontitis. These findings hold promise for early diagnosis, risk assessment, targeted prevention, and personalized treatment of periodontitis. Considering the marginal association observed in our study, further research is required to comprehend the biological underpinnings and ascertain the clinical relevance thoroughly.

Research organism: None

Introduction

Periodontitis imposes a considerable social burden on dental practice and general health

Periodontitis is a highly prevalent disease that affects a considerable percentage of the population. According to large-scale epidemiological research, up to half of all adults worldwide suffer periodontal disease, with severe periodontitis threatening 10.5–12.0% of them (Kassebaum et al., 2014). Furthermore, periodontitis is the leading cause of adult tooth loss, necessitating extensive dental procedures such as extractions, dental implants, or prosthetics, which can be costly and time-consuming for both patients and dental practitioners (Genco and Sanz, 2020). Recent research demonstrated a relationship between periodontitis and inflammatory comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease (Hajishengallis and Chavakis, 2021). The high prevalence and harmful implications of periodontitis underline the importance of managing periodontitis to maintain oral and general health (Peres et al., 2019). Since early-stage prevention is the most significant way to improve health, the identification of additional potential risk factors was required to provide predictive, preventive, and personalized strategies for periodontal care (Ma et al., 2021).

Evidence from epidemiology and pathophysiology demonstrates the impact of circulating immune cells on periodontitis

Periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the interactions between microorganisms and host immune response (Curtis et al., 2020). The immune response to periodontitis comprises both innate and adaptive immunity, with multiple cytokines, immune cells, and inflammatory pathways participating in a complex interplay (Dutzan et al., 2016). Systemic immunological alternations, such as circulating immune cells, play a crucial role in the initiation and progression of periodontitis (Cekici et al., 2014). An observational study indicated that patients with periodontitis experience a greater level of circulating leukocytes (Noz et al., 2021), while another discovered that the distribution of B cells alters in the context of severe periodontitis, with a higher proportion of circulating memory B cells (Demoersman et al., 2018). Furthermore, inflamed periodontal tissue recruits immune cells from circulation (Hajishengallis, 2020). With the progression of periodontitis, there is a significant alteration in the quantity of immune cells present within the periodontal tissue. Specifically, an increase in the count of both monocytes and B cells is observed, whereas a decrease is noted in the count of T cells (Nair et al., 2014; Steinmetz et al., 2016). The promising concept of ‘trained immunity’ has recently provided a greater understanding of the host immune response in periodontitis (Netea et al., 2020), which can explain the fact that the increased hyper-responsiveness of circulating immune cells from patients with periodontitis as well as its probable mechanism of mediating periodontitis and its comorbidities (Li et al., 2023).

Immunomodulation of systemic immune response serves as a hub for periodontal care

Systemic immunomodulation management can potentially improve host homeostasis by altering the composition and function of the immune milieu (Yang et al., 2021). Periodontitis can be effectively managed by restricting immune cell activation, implying that immunomodulators have significant promise in constructing comprehensive strategies for periodontal management (Zidar et al., 2021). For example, resveratrol, quercetin, and N-acetylcysteine were reported to reduce the release of reactive oxygen species by neutrophils, which aided in the prevention of periodontitis (Orihuela-Campos et al., 2015). Nonetheless, from a medical and therapeutic perspective, it is critical to determine whether the link between circulating immune cells and periodontitis is merely correlative or driven by causative mechanistic interactions (Lamont and Hajishengallis, 2015). Understanding the role of systemic immune alternations in periodontitis is critical for developing an effective strategy for early screening of high-risk patients, prompt implementation of definitive prevention, and individualized deployment of targeted treatment, all to reduce unexpected inflammatory responses, maintaining oral health, and avoiding complications (Zhang et al., 2023).

Mendelian randomization provides a potent complement to causal inference in terms of genetics

Previous research has substantiated the potential of immunomodulation management in predicting and preventing periodontitis; however, in observational studies, the association is frequently disguised by reverse causality, confounding factors, and disease conditions, which obscured the intrinsic causal inference between them (Hajishengallis and Korostoff, 2017). Mendelian randomization (MR) investigates the causal relationships between risk factors and diseases by exploiting genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs) (Davies et al., 2018), which is less likely to be affected by underlying bias or disease condition in that alleles are randomly allocated from parents to offspring (Julian et al., 2023). Notably, MR with distinct causal relationships may provide fresh evidence from a genomics perspective (Golubnitschaja et al., 2014). We postulate that individuals with a disproportionate immunological network have a higher risk of periodontitis due to unexpected inflammatory reactions.

Results

The present study, as shown in Figure 1, was based on the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology using the Mendelian Randomization (STROBE-MR) checklist (Skrivankova et al., 2021). The present research aims to evaluate the causal association between circulating immune cells and the risk of periodontitis, providing insight into opportunity for systemic immunomodulation management in periodontal care. We utilized summary statistics from publicly available genome-wide association studies (GWASs) to perform both univariable MR (UVMR) and multivariable MR (MVMR) analyses (Table 1, Supplementary file 1–Table S1). Furthermore, we replicated the UVMR analysis by excluding potentially pleiotropic single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and subsequently conducted subgroup and reverse MR analyses. Additionally, the Bayesian model averaging (MR-BMA) was employed to pinpoint the predominant characteristics with causal signals. Finally, we conducted a transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS) and colocalization analysis to discern potential genes implicated in biological relationships.

Figure 1. Study design.

(A) Overview of the process and principal assumptions of MR. (B) Data sources of the GWASs. (C) Methods performed in the present study. Abbreviations and Notes: BCC, Blood Cell Consortium; BMA, Bayesian model averaging, a high-throughput method based on nonlinear regression; BMI, body mass index; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; FUSION, functional summary-based imputation; GLIDE, Gene-Lifestyle Interactions in Dental Endpoints collaboration consortium; GWAS, genome-wide association study; IVW, inverse variance weighted, the primary method in MR to explore the association between exposure and outcome; LOO, leave-one-out, a method for detecting potential influential SNPs; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism, as genetic instrumental variables for the exposure and outcome; MACE, model-averaged causal estimate; MIP, marginal probability of inclusion; MR, Mendelian randomization; MR-PRESSO, Mendelian Randomization Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier, a method for assessing and rectifying pleiotropic SNPs; MSCE, model-specific causal estimate; MVMR, multivariable Mendelian randomization, an MR model for adjusting confounding and mutual correction; Neu, neutrophil; NKT, natural killer T cell; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cell; PP, posterior probability; TWAS, transcriptome-wide association study; UVMR, univariable Mendelian randomization.

© 2024, BioRender Inc

Figure 1 was created using BioRender, and is published under a CC BY-NC-ND license. Further reproductions must adhere to the terms of this license.

Table 1. Characteristics of the GWAS data for MR.

| Phenotype | Year | Sample size (n case/n control) | n SNP (million) | Ancestry | Unit | Consortium/cohort | PMID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | |||||||

| Circulating immune cells | 2020 | 563,946 | 15 | European | nl | BCC | 32888494 |

| Lymphocyte subsets | 2020 | 3757 | 15.2 | European | µg | Sardinian cohort | 32929287 |

| Outcome | |||||||

| Periodontitis | 2019 | 35,096 (12,251/22,845) | 10.8 | European | Event | GLIDE | 31235808 |

| Chronic periodontitis (FinnGen) | 2023 | 263,668 (4434/259,234) | 20.2 | European | Event | FinnGen (R9K11) | 36653562 |

| Chronic gingivitis (FinnGen) | 2021 | 196,245 (850/195,395) | 16.4 | European | Event | FinnGen (R5K11) | |

| Gingival hyperplasia (FinnGen) | 2023 | 259,613 (379/259,234) | 20.2 | European | Event | FinnGen (R9K11) | |

| Covariate | |||||||

| Cigarettes smoked per day | 2019 | 249,752 | 12 | European | 1/SD | GSCAN | 30643251 |

| Fasting plasma glucose | 2021 | 200,622 | 31 | European | mmol/l | MAGIC | 34059833 |

| Body mass index | 2018 | 681,275 | 2.3 | European | kg/m2 | GIANT | 30124842 |

Estimated effects of circulating immune cells on periodontitis risk

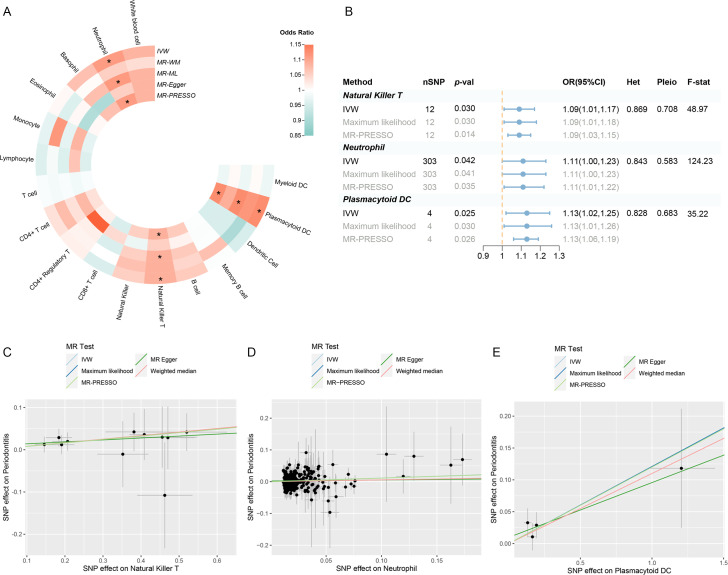

Following a rigorous screening procedure, a total of 1940 SNPs were selected as IVs in the present study (Supplementary file 1–Table S2). The F-statistics ranged from 28.67 to 220.07, indicating a low risk of weak instrument bias. Three circulating immune cells were identified to be suggestively significant in the inverse variance weighted (IVW) method [odds ratio (OR): 1.09, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.01–1.17, p = 0.030 for natural killer T (NKT) cells; OR: 1.11, 95% CI: 1.00–1.23, p = 0.042 for neutrophils; OR: 1.13, 95% CI: 1.02–1.25, p = 0.025 for plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs)], which were further supported by the maximum likelihood and MR Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier (MR-PRESSO) (Figure 2A, B; Supplementary file 1–Table S3). The MR-Egger regression revealed no evidence of horizontal pleiotropy (p-values for intercept >0.05). However, significant heterogeneity was detected in two traits (memory B cell and monocyte) (Supplementary file 1–Table S4), which faded after the removal of outliers (Supplementary file 1–Table S5—Table S5, Figure 2—figure supplement 1). Moreover, the leave-one-out analysis showed no influential SNPs significantly linked with the outcome (Figure 2—figure supplement 2). The observed significant results remained robust after removing pleiotropic SNPs (Supplementary file 1–Table S6), and the scatter plot displayed a balanced distribution among SNPs (Figure 2C–E).

Figure 2. Results of the UVMR.

(A) A circular heatmap representing the MR analyses for the associations between circulating immune cells and the risk of periodontitis. Lines, from outermost to innermost, represent IVW, MR-WM, MR-ML, MR‐Egger, and MR-PRESSO, respectively. The color scale of the heatmap is based on the OR. *p < 0.05. (B) A forest plot of the MR analyses for significant results in (A) (p < 0.05). The effects are quantified using OR with 95% CI. (C–E) The effect estimates for each variant in natural killer T cell (C), neutrophil (D), and plasmacytoid DC (E) are provided by plotting SNP–outcome associations against SNP–exposure associations. Lines with different colors represent the regression slope fitted by different MR methods. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DC, dendritic cell; F-stat, F-statistic; IVW, inverse variance weighted; Het, heterogeneity; MR, Mendelian randomization; MR-ML, Mendelian randomization weighted median; MR-WM, Mendelian randomization maximum likelihood; MR-PRESSO, Mendelian Randomization Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier; OR, odds ratio; Pleio, pleiotropy; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; UVMR, univariable Mendelian randomization.

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Scatter plots to explore outliers for two features with considerable heterogeneity.

Figure 2—figure supplement 2. Results of leave-one-out sensitivity analysis.

A replication UVMR of three subgroups of periodontal diseases (chronic periodontitis, chronic gingivitis, and gingival hyperplasia) was also performed in the FinnGen cohort (Figure 3, Figure 3—figure supplement 1). However, the significant findings identified within the primary database were not replicated during subgroup analysis, which may be attributed to the heterogeneity of periodontal disease and variations in the population composition across datasets. Intriguingly, B cell was discovered to be involved in the subgroups of the FinnGen population (OR: 1.11, 95% CI: 1.02–1.22, p = 0.019 for chronic periodontitis; OR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.02–1.88, p = 0.036 for gingival hyperplasia) (Supplementary file 1–Tables S7–S9). Reverse MR revealed no indication of reverse causality (Supplementary file 1–Table S10).

Figure 3. Results of the subgroup and reverse MR.

(A) A circular heatmap illustrates the results of the subgroup analysis and reverse MR. Lines in the heatmap represent periodontitis (GLIDE), chronic periodontitis (FinnGen), chronic gingivitis (FinnGen), gingival hyperplasia (FinnGen), and reverse MR analysis, progressing from outside to inside. The color scale of the heatmap is determined by the odds ratio (OR). *p < 0.05. (B) A forest plot of the MR analyses for significant results in Figure 4A (p < 0.05). The effects are quantified using OR with 95% CI. Abbreviations: CG, chronic gingivitis; CI, confidence interval; CP, chronic periodontitis; DC, dendritic cell; F-stat, F-statistic; GH, gingival hyperplasia; GLIDE, Gene-Lifestyle Interactions in Dental Endpoints collaboration consortium; Het, heterogeneity; IVW, inverse variance weighted; MR-PRESSO, Mendelian Randomization Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier; PD, periodontitis; Pleio, pleiotropy; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; MR, Mendelian randomization.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Scatter plots of the estimated effects in the subgroup MR.

Assessing the independent and prioritized relationships through MVMR

After accounting for variable mutual adjustment and covariate correction for potential confounders, the causal relationship between circulating neutrophils and periodontitis remained stable with no evidence of heterogeneity or pleiotropy (Figure 4A, B). Nevertheless, the observed association dissipated upon adjusting for body mass index (BMI), unveiling significant heterogeneity. Even though the MVMR-least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (MVMR-LASSO) analysis was utilized to make appropriate corrections, caution was still recommended when dealing with the effect. Furthermore, the significance of pDC and NKT remained stable after mutual adjustment, whereas the strength of the association for pDC was compromised in the MR-Egger sensitivity analysis (Supplementary file 1–Table S11).

Figure 4. Results of the MVMR.

(A) A heatmap represents the results of the MVMR. Rows and columns correspond to exposures and adjustment factors, respectively. The color scale of the heatmap is determined by the odds ratio (OR). *p < 0.05. (B) Forest plot analysis of the MVMR of significant results following mutual adjustment and confounder correction. The effects are quantified using OR with 95% CI. Scatter plots of the Cochran’s Q test and Cook’s distance to explore outlier or influential variations in Mendelian randomization-Bayesian model averaging (MR-BMA) for neutrophil (C), natural killer T (D), and plasmacytoid DC (E), respectively. Abbreviations: BMA, Bayesian model averaging; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; DC, dendritic cell; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; IVW, inverse variance weighted; Het, heterogeneity; LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; MVMR, multivariable Mendelian randomization; Pleio, pleiotropy; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

In the MR-BMA framework, the best models and factors were ordered and prioritized based on their posterior probability (PP) and marginal inclusion probability (MIP) metrics (Table 2, Supplementary file 1−Table S12). Consequently, we observed neutrophil as the best model and leading factor for periodontitis (p = 0.771, MIP = 0.895), followed by NKT and pDC. The Cochran’s Q test and Cook’s distance failed to detect outlier or influential variations (Figure 4C–E).

Table 2. Ranking of risk factors and models for periodontitis in MR-BMA analysis.

| Trait | Ranking by MIP | MIP | MACE | Ranking by PP | PP | MSCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil | 1 | 0.895 | 0.097 | 1 | 0.771 | 0.108 |

| Natural killer T cell | 2 | 0.135 | −0.003 | 2 | 0.056 | −0.017 |

| Plasmacytoid DC | 3 | 0.102 | 0 | 3 | 0.045 | 0.007 |

DC, dendritic cell; MACE, average causal effect of risk factor model; MIP, marginal inclusion probability; MR-BMA, Mendelian randomization-Bayesian model averaging; MSCE, model-specific causal estimates; PP, poster probability.

TWAS reveals key crosstalk genes

The TWAS indicated that five cross-trait genes, including CC2D2B (10q24.1), RP11-326C3.7 (11p15.5), USP3 (15q22.31), HERC1 (15q22.31), and AMFR (16q13), may be implicated in the interaction of circulating immune cells with periodontitis (Figure 5A, B). After Bonferroni correction (p < 6.27 × 10−6), we identified 658 of 3081 characteristics significantly associated with neutrophils, 5 of 443 with NKT, and 5 of 1038 with pDC. Within a broad criterion (p < 5 × 10−4), we discovered that 6 of 423 characteristics were linked to periodontitis (Figure 5C, Figure 5—figure supplement 1). Notably, four of these high-confidence genes were found to be involved with multiple phenotypes: S100A9, S100A12 (neutrophils and periodontitis); MCM6, P14KAP2 (neutrophils and pDC) (Table 3, Figure 5D). Most of these significant features survived conditional analysis and permutation testing (381/658 for neutrophils, 3/5 for NKT, 5/5 for pDC, and 5/6 for periodontitis). The majority of them were shown to be colocalized with their respective phenotype (554/658 for neutrophils, 4/5 for NKT, 3/5 for pDC, and 0/6 for periodontitis), implying that shared and pleiotropic SNPs influence both gene expression and phenotype (Supplementary file 1–Tables S13–S16).

Figure 5. Results of the TWAS and colocalization analysis.

(A) A Venn diagram illustrates the intersecting genes shared by multiple traits (p < 0.05). (B) A heatmap representing the TWAS and colocalization analysis for five genes interacting among neutrophil, natural killer T cell, plasmacytoid DC, and periodontitis. The TWAS Z-score is used as the color scale for the heatmap. *PP.H3 + PP.H4 > 0.5; **PP.H3 + PP.H4 > 0.8; ***PP.H4 > 0.8. (C) Manhattan plot of gene–traits associations for periodontitis. The x-axis represents genomic positions. Blue lines indicate a Z-score of 1.96. Red circles represent significant gene–trait associations (p < 0.05). Six genes satisfy a multiple corrected threshold of p < 5 × 10−4. (D) Regional Manhattan plot of conditional analysis for S100A9, S100A12 in periodontitis. Gray bars indicate the location of genes on chromosome 1. Genes colored in orange and green on the graph indicate the marginally and jointly significant genes that best explain the GWAS signals. Gray and blue dots indicate the GWAS p-values before and after conditioning on the jointly significant gene. Abbreviations: DC, dendritic cell; GWAS, genome-wide association study; PP, posterior probability; TWAS, transcriptome-wide association study.

Figure 5—figure supplement 1. Manhattan plots for natural killer T and plasmacytoid DC.

Table 3. TWAS and colocalization analysis identified genes involved in multiple phenotypes.

| Gene name | Position | Phenotype | TWAS Z-score | TWAS p val | Perm p val | Model p val | PP.H3 | PP.H4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S100A9 | 1q21.3 | Neutrophil | 7.225 | 5.0 × 10−13 | 0 | 1.7 × 10−17 | 0.035 | 0.962 |

| Periodontitis | −3.564 | 3.7 × 10−4 | 1.3 × 10−3 | 1.7 × 10−17 | 0.008 | 0.259 | ||

| S100A12 | 1q21.3 | Neutrophil | 7.310 | 2.7 × 10−13 | 1.7 × 10−4 | 4.1 × 10−43 | 0.027 | 0.970 |

| Periodontitis | −3.513 | 4.4 × 10−4 | 8.1 × 10−4 | 4.1 × 10−43 | 0.008 | 0.244 | ||

| MCM6 | 2q21.3 | Neutrophil | −5.549 | 2.9 × 10−8 | 0 | 3.5 × 10−13 | 0 | 0.999 |

| Plasmacytoid DC | 7.172 | 7.4 × 10−13 | 2.7 × 10−3 | 3.5 × 10−13 | 1.000 | 0 | ||

| PI4KAP2 | 22q11.21 | Neutrophil | 5.345 | 9.0 × 10−8 | 3.3 × 10−3 | 3.7 × 10−39 | 0.003 | 0.016 |

| Plasmacytoid DC | 5.322 | 1.0 × 10−7 | 3.2 × 10−3 | 3.7 × 10−39 | 0.009 | 0.045 |

DC, dendritic cell; Perm, permutation test; PP, posterior probability; TWAS, transcriptome-wide association study.

Discussion

In the present research, we employed MR to explore the potential links between circulating immune cells and periodontitis. Our study revealed causal relationships between elevated levels of circulating neutrophils, NKT cells, and pDCs with a higher risk of periodontitis. TWAS and colocalization analysis demonstrated possible high-confidence and cross-trait genes to be engaged in their interaction.

Circulating neutrophils play a significant part in periodontitis and inflammatory comorbidities

Notably, our findings suggested that circulating neutrophils may play a leading causal role in the likelihood of periodontitis, and it remained robust after correcting for potential confounding factors and outliers. Neutrophils are abundant and short-lived myeloid cells that can be rapidly recruited to inflammatory sites, serving as the first line of defense against infections and other host insults. In recent years, a profound understanding of the role of neutrophils in chronic inflammatory diseases, where they may directly act as effectors of destructive inflammation, has been gained. However, a scarcity of neutrophils can also trigger damaging tissue inflammation, their pivotal role in maintaining physiological equilibrium (Ley et al., 2018). Numerous pieces of clinical evidence have uncovered that neutrophils account for a significant portion of inflammatory tissue damage and that the severity of periodontitis is positively correlated with the overproduction, dysregulation, or hyperactivity of neutrophils (Chapple et al., 2023; Fine et al., 2021). A case–control study indicated that periodontitis patients suffered from more apoptotic circulatory neutrophils than healthy people (Nicu et al., 2018). An increased neutrophil count could suggest the inflammatory burden of gingivitis and dental plaque in the oral cavity (Sreenivasan and Prasad, 2022). Another study discovered neutrophil depletion ameliorated experimental periodontitis, while unrestrained recruitment aggravated it (Dutzan et al., 2018).

Neutrophil-mediated inflammatory responses are crucial in the pathogenesis of periodontitis, influencing its localized manifestation and systemic complications, thereby associating it with a broad spectrum of inflammatory complications (Hajishengallis and Chavakis, 2022). During periodontitis, neutrophils act as the primary defense against bacteremia, with their primary function being to engulf and eradicate these bacteria, thus inhibiting their dissemination within the body. Following this, neutrophils liberally release proinflammatory cytokines in the connective tissue adjacent to the periodontal pocket. It is plausible that these cytokines could permeate into the bloodstream, thereby potentially exacerbating systemic inflammation (D’Aiuto et al., 2013). In severe periodontitis cases, patients experience low-grade systemic inflammation, as indicated by elevated levels of neutrophils and proinflammatory mediators, compared to their healthy counterparts (Schenkein et al., 2020). Preclinical research also demonstrates that ligature-induced periodontitis is accompanied by an elevation in circulating neutrophil counts, resulting in endothelial dysfunction and vascular inflammation (Brito et al., 2013). The quantity and functionality of neutrophils are critical indicators of inflammation severity. The reduction in neutrophil count and inflammatory mediators observed after successful periodontitis treatment suggests a decrease in systemic inflammation (Hajishengallis et al., 2022).

The recently developed concept of ‘trained immunity’ has introduced new perspectives on how neutrophils contribute to periodontitis and its comorbidities. ‘Trained immunity’ primarily denotes the memory-like response of myeloid innate immune cells, such as neutrophils and monocytes, to pathogens following initial infection (Li et al., 2022). Contrary to the memory response of specific immune cells, the memory characteristic of trained immunity primarily manifests as a rapid response and efficient elimination of pathogens rather than clear recognition (Netea et al., 2016). Trained myeloid cells have the potential to amplify the functionality of neutrophils, thereby fortifying the body’s defense against subsequent infections. Nevertheless, within the framework of chronic inflammation, these cells could intensify tissue damage (Hajishengallis, 2014).

Periodontitis exemplifies a condition that stimulates maladaptive myelopoiesis in the bone marrow, characterized by producing excessive hyper-inflammatory monocytes and neutrophils (Li et al., 2023). This leads to an influx of maladaptively trained neutrophils in both the blood circulation and periodontal tissues that infiltrate not only oral tissues but also non-oral ones, simultaneously triggering an increase in the production of neutrophil extracellular traps and a reduction in their degradation (White et al., 2016). As a result, this process intensifies the collapse of the epithelial barrier, fosters bacteremia, exacerbates periodontitis, and amplifies the severity of inflammatory complications (Burmeister et al., 2022). While our comprehension of neutrophils' regulatory mechanisms and functions is far from complete, current research has facilitated the development of targeted therapeutic strategies to manage chronic inflammatory disorders mediated by neutrophils, such as the inflammatory response observed in periodontitis.

Several lymphocyte subsets are causally associated with the risk of periodontitis

NKT cells, a distinct fraction of T lymphocytes, are linked to the pathophysiology of various inflammatory, osteolytic, and autoimmune diseases (Godfrey et al., 2000). Similar to our findings, previous research revealed more NKT recruited in periodontitis tissues (Muthukuru, 2012; Yamazaki et al., 2001). Several studies have demonstrated the tissue-specific function of NKT and highlighted its pathogenic role in periodontitis (Aoki-Nonaka et al., 2014; Melgar-Rodríguez et al., 2021), which may be attributed to the proinflammatory and immunoregulatory activities mediated by NKT, spanning from cytokine production to immune cell interactions (Seidel et al., 2020).

In addition, our study identified a convoluted causal relationship between pDC and periodontitis. Dendritic cells, as specialized antigen-presenting cells, play a crucial role in the modulation of the host immune response and may be related to bone loss during periodontitis (El-Awady et al., 2022; Ginesin et al., 2023). In response to viral encounters and infection, pDC represents a unique subgroup of DC that releases type I interferon (Jego et al., 2003). However, pDC is only discovered in a tiny percentage of healthy oral tissues, and more relevant clinical research still needs to be conducted (Meghil and Cutler, 2020; Wilensky et al., 2014). The involvement of pDC in periodontitis deserves further investigation.

Systemic immunomodulation management for immune cells serves as a target for periodontal care

Periodontitis is a damaging inflammatory disease induced and exacerbated by the plaque biofilm and host immune response (Moutsopoulos and Konkel, 2018). The systemic immune response comprises both innate and adaptive immunity, with numerous cytokines, immune cells, and inflammatory pathways interacting in complex crosstalk during periodontitis, hinting that immunomodulation management may be an essential target for periodontal care (Dutzan et al., 2016; Hajishengallis, 2014).

Reactive periodontal therapies, which focus on plaque management, pocket depth reduction, and gingival bleeding eradication, only sometimes produce the intended results and fall short of a genuinely comprehensive approach to dental care (Kornman et al., 2017). Recently, a promising term ‘P4 periodontics’ (Predictive, Preventive, Personalized, and Participatory) has been introduced as a multilayer healthcare paradigm for the management of periodontitis, emphasizing the personalized responsiveness of treatment to disease (Bartold and Ivanovski, 2022). Modulating systemic host immune responses is particularly appropriate for predicting the progression and severity of periodontitis in persons whose periodontal condition is only slightly correlated with dental plaque (Divaris et al., 2020). MR contributes a novel approach to investigating systemic immunological alternations in periodontitis. A recent MR study evaluated the causal associations between circulating cytokines and the risk of periodontitis (Huang et al., 2023).

Our present study highlighted five genes (USP3, AMFR, HERC1, CC2D2B, and RP11-326C3.7) that may play a pivotal role in the communication between circulating neutrophils, pDC, NKT, and periodontitis, as well as two high-confidence genes (S100A9, S100A12) situated within 1q21.3 as prospective gene targets for regulating circulating neutrophils during periodontitis. Our findings could pave the way for a novel preventive and therapeutic approach to modifying the systemic immunological equilibrium in periodontitis patients by modulating circulating immune cells. These findings enable the prediction of individuals at risk of periodontitis by screening specific immune imbalances, which could then be employed to prevent periodontitis and related inflammatory comorbidities, particularly in patients with systemic susceptibility factors.

Strengths and limitations in the present study

The present study exhibited several strengths. First, under the premise of three key assumptions, MR is a powerful tool for explaining the relationship between complicated features (such as circulating immune cells) by successfully mitigating the effect of probable confounders and allowing for reasonable causal order. Second, a rigorous quality control process was conducted in accordance with the STROBE-MR checklist in multiple domains, including IVs selection, heterogeneity investigations, and removal of pleiotropic loci (Supplementary file 2—STROBE-MR Checklist). Third, we adopted a series of sensitivity tests and MVMR to rule out the impact of outlier, influential, or pleiotropic SNPs. Fourth, a novel method based on nonlinear Bayesian averaging was applied to explore the causal drivers of disease risk from a set of high-throughput risk factors. Finally, TWAS was used in conjunction with MR to identify achievable regulatory gene targets for periodontal care.

However, some limitations should be addressed when interpreting the results. To begin with, a need for GWAS databases hampered more comprehensive and precise analyses. As a result, we could not evaluate the impact of immune cells on distinct subsets of periodontal illnesses (such as gingival recession and periodontal abscess) or ethnic groups (such as East Asian and African). Second, the primary results from the IVW method were not stable across all alternative analyses, nor were they replicated within subgroups, implying that the findings had limited evidentiary power. Third, the considerable variation in sample size between the two exposure databases contributes to the discrepancies in the number of positive SNPs. Despite our exploration of multiple selection thresholds for IVs, the inconsistency in screening methods and the disparity in the included SNPs could potentially introduce bias. Fourth, none of the results satisfied the Bonferroni correction (p < 0.05/17 traits = 0.003), which may have inflated the rate of type I errors. Despite our best attempts to minimize potential confounding factors, interferences from unobserved pleiotropies could not be completely ruled out. Fifth, we relied on the whole-blood data for the FUSION algorithm due to the lack of transcriptome data associated with oral tissues (such as gums, oral mucosa, and alveolar bone) in the GTEx database. This has led to an excessive focus on systemic immunological changes, thereby overlooking the significance of alterations in local periodontal tissue immunity. Such an oversight could compromise the precision and pertinence of our research findings. Sixth, in addition to quantities, function abnormalities (such as dysregulation or hyperactivity) of circulating immune cells may also be related to the susceptibility and severity of periodontitis; however, our research failed to address this issue. Seventh, while most immune cells in the gingival crevicular fluid are derived from blood, the amount of circulating immune cells is influenced by more intricate factors, which may challenge the current causal inference. Finally, since MR evaluates causal inference from the standpoint of genetic variations, it may sometimes correspond differently to fact.

In conclusion, the present study provides suggestive evidence of the causal associations of genetically predicted circulating neutrophils, NKT cells, and pDCs on the risk of periodontitis, which shed light on the involvement of systemic immunological alterations in periodontitis etiology. Our findings may provide an innovative and evidence-based framework for systemic immunomodulation management in periodontal care, which can be valuable for early diagnostics, risk assessment, targeted prevention, and personalized management of periodontitis, especially for patients with systemic susceptibility factors. However, the effect estimation discovered in our study was marginal, prompting caution when transferring to clinical practice. More studies are required to comprehend our findings’ biological plausibility and clinical applicability.

Materials and methods

Data source

Summary-level data on 17 circulating immune cells were obtained from large-scale GWAS conducted by the Blood Cell Consortium (BCC) and the Sardinian cohort (Orrù et al., 2020 [GWAS Catalog: GCST0001391-GCST0002121]; Vuckovic et al., 2020 [GWAS Catalog: GCST90002379-GCST90002407]). The GWAS data for periodontitis and its subtypes were supplied by the Gene-Lifestyle Interactions in Dental Endpoints collaboration (GLIDE) consortium and the FinnGen cohort (Kurki et al., 2023; Shungin et al., 2019). To maintain the homogeneity within the target group and minimize overlap, we performed a screening process on the population. Populations from the Latin American and UK Biobank were excluded from the periodontitis dataset (Ye et al., 2023). Characteristics of GWAS and included cohorts are highlighted in Table 1 and Supplementary file 1–Table S1. The statistical analyses were performed using ‘TwoSampleMR’ (version 0.5.7)’, ‘MRPRESSO’ (version 1.0), ‘RadialMR’ (version 1.1), ‘mrbma’ (version 0.1.0), and ‘GagnonMR’ (version 0.0.0.9) packages in R software (version 4.3.1).

Candidates for IVs underwent a thorough set of screening procedures. A complicated criterion was performed to equalize the sample disparities among databases. We initially filtered the p-values of the SNPs, followed by the selection of independent SNPs using the linkage disequilibrium approach. A rigorous threshold of p < 1 × 10−9 was applied to the database with an abundance of positive SNPs (as in the BCC consortium) to ensure the reliability of IVs. Otherwise, a relatively strict standard of p < 1 × 10−6 was initially adopted (as in the Sardinian cohort), and we would loosen it at p < 5 × 10−6 if less than three SNPs met this threshold (an essential requirement for MR-PRESSO analysis). The R2 and F-statistics were introduced to demonstrate the degree of genetic variation explained and their relative impact on the outcomes, and SNPs with F-statistics <10 would be removed based on the first MR assumption (Papadimitriou et al., 2020). In addition, SNPs that exhibited a direct association with the outcome would also be deleted to support the third MR assumption. Palindromic and ambiguous SNPs were eliminated throughout the harmonization processes to ensure the reliability and validity of causal inference. In MVMR, we excluded SNPs in the major histocompatibility complex area (6p21.31) due to their complexity and confounding effects (Burgess and Thompson, 2015).

Univariable Mendelian randomization

In UVMR, the IVW method was performed as the primary analysis, and four alternative MR methods, including weighted median, maximum likelihood, MR-Egger, and MR-PRESSO global test were employed for sensitivity testing to assess the robustness of the IVW estimates. The IVW assumes that all genetic variations meet the conditions and integrates calculations from multiple genetic variants by weighting them inversely to variances (Sanderson et al., 2022). The weighted median generates precise estimates when more than half of the SNPs are valid (Gormley et al., 2023). The maximum likelihood offers a normal bivariate distribution to estimate causal effects by maximizing the likelihood function with a linear relationship (Xue et al., 2021). MR-Egger provides estimates after accounting for possible horizontal pleiotropy discovered by its incorporated intercept test, albeit the estimates were frequently underpowered (Bowden et al., 2016). MR-PRESSO detects outliers that cause pleiotropy and generates estimates once these outlier SNPs are eliminated (Verbanck et al., 2018). The observed significant results were considered ‘robust’ if the effect of sensitivity analyses was identical to that of the IVW method, yielding a p-value <0.05.

Multivariable Mendelian randomization

To gauge the individual influence of each variant, MVMR analysis with mutual adjustment was performed, followed by a correction for associated confounders (Burgess and Thompson, 2015). We have incorporated covariates, including the number of cigarettes smoked, fasting plasma glucose levels, and BMI into the MVMR analysis, given that these factors could indirectly affect systemic immune responses and inflammation (Liu et al., 2023). The MVMR-IVW method was utilized as the primary test, supplemented by the MVMR-LASSO and the MVMR-Egger method (Bowden et al., 2016). The MVMR-LASSO regression yields dependable estimations for moderate-to-high degrees of heterogeneity or pleiotropy, and it also assists in alleviating the potential effects of multicollinearity among variables (Grant and Burgess, 2021).

The heterogeneity and horizontal pleiotropy of the results were quantified using Cochran’s Q-statistics and the intercept term in MR-Egger regression, respectively. The MR-Radial, a more sensitive method for outliers, would detect and remove outlier SNPs whenever heterogeneity or pleiotropy was discovered (Bowden et al., 2018). The leave-one-out analysis and scatter plot were conducted to detect influential SNPs.

Bayesian model averaging

As a multivariate framework for high-throughput risk factors based on nonlinear regression, the MR-BMA was then employed to explore the leading traits responsible for outcome (Zuber et al., 2020). First, we used closed-form Bayes factors and independence priors to calculate each variant’s PP and model-specific causal estimates. Next, the total PPs for all potential models were added to determine the MIP. The model-averaged causal estimate, which reflected the average direct effect of each metabolic trait on the outcomes, was also used to compare risk factors and interpret the directions. Finally, the best model was chosen, preferably based on ranking each model’s MIP and PP values. The Q-statistic and Cook’s distance were used to identify invalid outliers and influential variants within the model. A genetic variant was defined as either an outlier or an influential variant if it possessed a q-value exceeding 10 or its Cook’s distance surpassed the median of the corresponding F-distribution (Eledum, 2021). The MR-BMA would be repeated once unqualified variations were discovered.

Transcriptome-wide association study

We exploited the updated Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project Version 8 whole-blood data for TWAS analysis (Gusev et al., 2016). First, the functional summary-based imputation (FUSION) pipeline was used to infer the transcriptome associated with significant outcomes, among which the optimal gene expression model was chosen by comparing the values of R2 provided by Bayesian sparse linear mixed models and multiple penalized linear regressions. A Bonferroni-corrected criterion of p < 6.27 × 10−6 (0.05/7890 genes) was adopted to measure statistical significance. Then, conditional analysis and permutation testing were implemented to assess the dependability and robustness of the gene transcript–trait relationships discovered through TWAS. Finally, we performed an expression quantitative trait locus colocalization analysis on TWAS-derived genes to determine whether the association was caused by a single causal SNP (PP.H4) or distinct causal SNPs (PP.H3). PP.H3 + PP.H4 > 0.8 was considered significant evidence of colocalization (Wallace, 2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all the GWASs for making the summary data publicly available, and we appreciate all the investigators and participants who contributed to those studies. We appreciate the BioRender’s convenience in drawing Figure 1 (https://www.biorender.com). Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities 2022FZZX01-33 Shan Wang. Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities 2023QZJH58 Zhiyong Wang. National Major Science and Technology Projects of China 81991500 and 81991502 Qianming Chen. Zhejiang University Global Partnership Fund 188170 and 194452307/004 Zhiyong Wang. Joint Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province LHDMD23H300001 Shan Wang.

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Contributor Information

Yingying Mao, Email: myy@zcmu.edu.cn.

Qianming Chen, Email: qmchen@zju.edu.cn.

Bian Zhuan, Wuhan University, China.

Tadatsugu Taniguchi, University of Tokyo, Japan.

Funding Information

This paper was supported by the following grants:

Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities 2023QZJH58 to Zhiyong Wang.

National Major Science and Technology Projects of China 81991500 to Qianming Chen.

Zhejiang University Global Partnership Fund 188170 to Zhiyong Wang.

Joint Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province LHDMD23H300001 to Shan Wang.

Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities 2022FZZX01-33 to Shan Wang.

National Major Science and Technology Projects of China 81991502 to Qianming Chen.

Zhejiang University Global Partnership Fund 194452307/004 to Zhiyong Wang.

Additional information

Competing interests

No competing interests declared.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Conceptualization, Writing – original draft.

Conceptualization, Writing – original draft.

Conceptualization, Methodology.

Conceptualization, Methodology.

Validation, Methodology.

Conceptualization, Methodology.

Funding acquisition, Writing – review and editing.

Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration.

Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review and editing.

Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review and editing.

Ethics

Since we utilized publicly available GWAS summary data or published studies, ethical committee approval was not required for this manuscript.

Additional files

Characteristics of the single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) used as instrumental variables (IVs) in the Mendelian randomization (MR). Effect estimates of causal associations between circulating immune cells and periodontitis risk. The heterogeneity and horizontal pleiotropy of the main results using Cochran’s Q-statistics and MR-Egger intercept. Effect estimates of causal associations after excluding outliers in RadialMR for two features with considerable heterogeneity. Effect estimates of causal associations after excluding influential or outlier SNPs for significant results. Effect estimates of causal associations between circulating immune cells and chronic periodontitis, chronic gingivitis, and gingival hyperplasia in subgroup analysis. Effect estimates of the reverse associations between periodontitis and circulating immune cells. Effect estimates of causal associations after mutual and covariate correction in multivariable Mendelian randomization (MVMR). Ranking of models according to their posterior probability (PP) using Mendelian randomization-Bayesian model averaging (MR-BMA) analysis. Results of transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS), conditional analysis, permutation testing, and colocalization analysis on neutrophil, natural killer T cell, plasmacytoid dendritic cell (DC), and periodontitis.

Data availability

The data generated or analyzed during this study are available in this published article and its supplementary information files. The code and curated data for the present analyzed are available at GitHub (copy archived at Code4Ye, 2024).

The following previously published dataset was used:

The GLIDE consortium 2019. GWAS summary statistics for dental caries and periodontitis. Data Repository for University of Bristol.

References

- Aoki-Nonaka Y, Nakajima T, Miyauchi S, Miyazawa H, Yamada H, Domon H, Tabeta K, Yamazaki K. Natural killer T cells mediate alveolar bone resorption and a systemic inflammatory response in response to oral infection of mice with Porphyromonas gingivalis. Journal of Periodontal Research. 2014;49:69–76. doi: 10.1111/jre.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartold PM, Ivanovski S. P4 Medicine as a model for precision periodontal care. Clinical Oral Investigations. 2022;26:5517–5533. doi: 10.1007/s00784-022-04469-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden J, Del Greco M F, Minelli C, Davey Smith G, Sheehan NA, Thompson JR. Assessing the suitability of summary data for two-sample Mendelian randomization analyses using MR-Egger regression: the role of the I2 statistic. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2016;45:1961–1974. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden J, Spiller W, Del Greco M F, Sheehan N, Thompson J, Minelli C, Davey Smith G. Improving the visualization, interpretation and analysis of two-sample summary data Mendelian randomization via the radial plot and radial regression. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2018;47:1264–1278. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito LCW, DalBó S, Striechen TM, Farias JM, Olchanheski LR, Mendes RT, Vellosa JCR, Fávero GM, Sordi R, Assreuy J, Santos FA, Fernandes D. Experimental periodontitis promotes transient vascular inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Archives of Oral Biology. 2013;58:1187–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess S, Thompson SG. Multivariable Mendelian randomization: the use of pleiotropic genetic variants to estimate causal effects. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2015;181:251–260. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister A, Vidal-Y-Sy S, Liu X, Mess C, Wang Y, Konwar S, Tschongov T, Häffner K, Huck V, Schneider SW, Gorzelanny C. Impact of neutrophil extracellular traps on fluid properties, blood flow and complement activation. Frontiers in Immunology. 2022;13:1078891. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1078891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cekici A, Kantarci A, Hasturk H, Van Dyke TE. Inflammatory and immune pathways in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Periodontology 2000. 2014;64:57–80. doi: 10.1111/prd.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapple ILC, Hirschfeld J, Kantarci A, Wilensky A, Shapira L. The role of the host-Neutrophil biology. Periodontology 2000. 2023;01:12490. doi: 10.1111/prd.12490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Code4Ye eLife202402. swh:1:rev:359121665fadfc34f72241ea9d22aec28f926f51Software Heritage. 2024 https://archive.softwareheritage.org/swh:1:dir:644e6d6f1f0efa7eb89cca6c8a3755987cd373ac;origin=https://github.com/Code4Ye/eLife202402;visit=swh:1:snp:fe3f5b0f36063c72e972655eacb3f6e256197f39;anchor=swh:1:rev:359121665fadfc34f72241ea9d22aec28f926f51

- Curtis MA, Diaz PI, Van Dyke TE. The role of the microbiota in periodontal disease. Periodontology 2000. 2020;83:14–25. doi: 10.1111/prd.12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Aiuto F, Orlandi M, Gunsolley JC. Evidence that periodontal treatment improves biomarkers and CVD outcomes. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2013;40:S85–S105. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies NM, Holmes MV, Davey Smith G. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: a guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ. 2018;362:k601. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demoersman J, Pochard P, Framery C, Simon Q, Boisramé S, Soueidan A, Pers JO. B cell subset distribution is altered in patients with severe periodontitis. PLOS ONE. 2018;13:e0192986. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divaris K, Moss K, Beck JD. Biologically informed stratification of periodontal disease holds the key to achieving precision oral health. Journal of Periodontology. 2020;91:S50–S55. doi: 10.1002/JPER.20-0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutzan N, Konkel JE, Greenwell-Wild T, Moutsopoulos NM. Characterization of the human immune cell network at the gingival barrier. Mucosal Immunology. 2016;9:1163–1172. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutzan N, Kajikawa T, Abusleme L, Greenwell-Wild T, Zuazo CE, Ikeuchi T, Brenchley L, Abe T, Hurabielle C, Martin D, Morell RJ, Freeman AF, Lazarevic V, Trinchieri G, Diaz PI, Holland SM, Belkaid Y, Hajishengallis G, Moutsopoulos NM. A dysbiotic microbiome triggers TH17 cells to mediate oral mucosal immunopathology in mice and humans. Science Translational Medicine. 2018;10:eaat0797. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat0797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Awady AR, Elashiry M, Morandini AC, Meghil MM, Cutler CW. Dendritic cells a critical link to alveolar bone loss and systemic disease risk in periodontitis: Immunotherapeutic implications. Periodontology 2000. 2022;89:41–50. doi: 10.1111/prd.12428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eledum H. Leverage and influential observations on the Liu type estimator in the linear regression model with the severe collinearity. Heliyon. 2021;7:e07792. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine N, Chadwick JW, Sun C, Parbhakar KK, Khoury N, Barbour A, Goldberg M, Tenenbaum HC, Glogauer M. Periodontal inflammation primes the systemic innate immune response. Journal of Dental Research. 2021;100:318–325. doi: 10.1177/0022034520963710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genco RJ, Sanz M. Clinical and public health implications of periodontal and systemic diseases: An overview. Periodontology 2000. 2020;83:7–13. doi: 10.1111/prd.12344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginesin O, Mayer Y, Gabay E, Rotenberg D, Machtei EE, Coyac BR, Bar-On Y, Zigdon-Giladi H. Revealing leukocyte populations in human peri-implantitis and periodontitis using flow cytometry. Clinical Oral Investigations. 2023;27:5499–5508. doi: 10.1007/s00784-023-05168-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey DI, Hammond KJ, Poulton LD, Smyth MJ, Baxter AG. NKT cells: facts, functions and fallacies. Immunology Today. 2000;21:573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01735-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golubnitschaja O, Kinkorova J, Costigliola V. Predictive, Preventive and Personalised Medicine as the hardcore of “Horizon 2020”: EPMA position paper. The EPMA Journal. 2014;5:6. doi: 10.1186/1878-5085-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gormley M, Dudding T, Thomas SJ, Tyrrell J, Ness AR, Pring M, Legge D, Davey Smith G, Richmond RC, Vincent EE, Bull C. Evaluating the effect of metabolic traits on oral and oropharyngeal cancer risk using Mendelian randomization. eLife. 2023;12:e82674. doi: 10.7554/eLife.82674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant AJ, Burgess S. Pleiotropy robust methods for multivariable Mendelian randomization. Statistics in Medicine. 2021;40:5813–5830. doi: 10.1002/sim.9156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusev A, Ko A, Shi H, Bhatia G, Chung W, Penninx BWJH, Jansen R, de Geus EJC, Boomsma DI, Wright FA, Sullivan PF, Nikkola E, Alvarez M, Civelek M, Lusis AJ, Lehtimäki T, Raitoharju E, Kähönen M, Seppälä I, Raitakari OT, Kuusisto J, Laakso M, Price AL, Pajukanta P, Pasaniuc B. Integrative approaches for large-scale transcriptome-wide association studies. Nature Genetics. 2016;48:245–252. doi: 10.1038/ng.3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G. Immunomicrobial pathogenesis of periodontitis: keystones, pathobionts, and host response. Trends in Immunology. 2014;35:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Korostoff JM. Revisiting the Page & Schroeder model: the good, the bad and the unknowns in the periodontal host response 40 years later. Periodontology 2000. 2017;75:116–151. doi: 10.1111/prd.12181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G. New developments in neutrophil biology and periodontitis. Periodontology 2000. 2020;82:78–92. doi: 10.1111/prd.12313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Chavakis T. Local and systemic mechanisms linking periodontal disease and inflammatory comorbidities. Nature Reviews. Immunology. 2021;21:426–440. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00488-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Chavakis T. Mechanisms and Therapeutic Modulation of Neutrophil-Mediated Inflammation. Journal of Dental Research. 2022;101:1563–1571. doi: 10.1177/00220345221107602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Li X, Divaris K, Chavakis T. Maladaptive trained immunity and clonal hematopoiesis as potential mechanistic links between periodontitis and inflammatory comorbidities. Periodontology 2000. 2022;89:215–230. doi: 10.1111/prd.12421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SJ, Li R, Xu S, Liu Y, Li SH, Duan SZ. Assessment of bidirectional relationships between circulating cytokines and periodontitis: Insights from a mendelian randomization analysis. Frontiers in Genetics. 2023;14:1124638. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2023.1124638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jego G, Palucka AK, Blanck JP, Chalouni C, Pascual V, Banchereau J. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells induce plasma cell differentiation through type I interferon and interleukin 6. Immunity. 2003;19:225–234. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian TH, Cooper-Knock J, MacGregor S, Guo H, Aslam T, Sanderson E, Black GCM, Sergouniotis PI. Phenome-wide Mendelian randomisation analysis identifies causal factors for age-related macular degeneration. eLife. 2023;12:e82546. doi: 10.7554/eLife.82546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray CJL, Marcenes W. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990-2010: a systematic review and meta-regression. Journal of Dental Research. 2014;93:1045–1053. doi: 10.1177/0022034514552491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornman KS, Giannobile WV, Duff GW. Quo vadis: what is the future of periodontics? How will we get there? Periodontology 2000. 2017;75:353–371. doi: 10.1111/prd.12217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurki MI, Karjalainen J, Palta P, Sipilä TP, Kristiansson K, Donner KM, Reeve MP, Laivuori H, Aavikko M, Kaunisto MA, Loukola A, Lahtela E, Mattsson H, Laiho P, Della Briotta Parolo P, Lehisto AA, Kanai M, Mars N, Rämö J, Kiiskinen T, Heyne HO, Veerapen K, Rüeger S, Lemmelä S, Zhou W, Ruotsalainen S, Pärn K, Hiekkalinna T, Koskelainen S, Paajanen T, Llorens V, Gracia-Tabuenca J, Siirtola H, Reis K, Elnahas AG, Sun B, Foley CN, Aalto-Setälä K, Alasoo K, Arvas M, Auro K, Biswas S, Bizaki-Vallaskangas A, Carpen O, Chen C-Y, Dada OA, Ding Z, Ehm MG, Eklund K, Färkkilä M, Finucane H, Ganna A, Ghazal A, Graham RR, Green EM, Hakanen A, Hautalahti M, Hedman ÅK, Hiltunen M, Hinttala R, Hovatta I, Hu X, Huertas-Vazquez A, Huilaja L, Hunkapiller J, Jacob H, Jensen J-N, Joensuu H, John S, Julkunen V, Jung M, Junttila J, Kaarniranta K, Kähönen M, Kajanne R, Kallio L, Kälviäinen R, Kaprio J, FinnGen. Kerimov N, Kettunen J, Kilpeläinen E, Kilpi T, Klinger K, Kosma V-M, Kuopio T, Kurra V, Laisk T, Laukkanen J, Lawless N, Liu A, Longerich S, Mägi R, Mäkelä J, Mäkitie A, Malarstig A, Mannermaa A, Maranville J, Matakidou A, Meretoja T, Mozaffari SV, Niemi MEK, Niemi M, Niiranen T, O Donnell CJ, Obeidat ME, Okafo G, Ollila HM, Palomäki A, Palotie T, Partanen J, Paul DS, Pelkonen M, Pendergrass RK, Petrovski S, Pitkäranta A, Platt A, Pulford D, Punkka E, Pussinen P, Raghavan N, Rahimov F, Rajpal D, Renaud NA, Riley-Gillis B, Rodosthenous R, Saarentaus E, Salminen A, Salminen E, Salomaa V, Schleutker J, Serpi R, Shen H-Y, Siegel R, Silander K, Siltanen S, Soini S, Soininen H, Sul JH, Tachmazidou I, Tasanen K, Tienari P, Toppila-Salmi S, Tukiainen T, Tuomi T, Turunen JA, Ulirsch JC, Vaura F, Virolainen P, Waring J, Waterworth D, Yang R, Nelis M, Reigo A, Metspalu A, Milani L, Esko T, Fox C, Havulinna AS, Perola M, Ripatti S, Jalanko A, Laitinen T, Mäkelä TP, Plenge R, McCarthy M, Runz H, Daly MJ, Palotie A. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature. 2023;613:508–518. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05473-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont RJ, Hajishengallis G. Polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis in inflammatory disease. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2015;21:172–183. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley K, Hoffman HM, Kubes P, Cassatella MA, Zychlinsky A, Hedrick CC, Catz SD. Neutrophils: New insights and open questions. Science Immunology. 2018;3:eaat4579. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aat4579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Wang H, Yu X, Saha G, Kalafati L, Ioannidis C, Mitroulis I, Netea MG, Chavakis T, Hajishengallis G. Maladaptive innate immune training of myelopoiesis links inflammatory comorbidities. Cell. 2022;185:1709–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Chen Y, Cai G, Ni Q, Geng Y, Wang T, Bao C, Ruan X, Wang H, Sun W. Roles of trained immunity in the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Journal of Periodontal Research. 2023;58:864–873. doi: 10.1111/jre.13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Lai H, Zhang R, Xia L, Liu L. Causal relationship between gastro-esophageal reflux disease and risk of lung cancer: insights from multivariable Mendelian randomization and mediation analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2023;52:1435–1447. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyad090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Wang Y, Wu H, Li F, Feng X, Xie Y, Xie D, Wang W, Lo ECM, Lu H. Periodontal health related-inflammatory and metabolic profiles of patients with end-stage renal disease: potential strategy for predictive, preventive, and personalized medicine. The EPMA Journal. 2021;12:117–128. doi: 10.1007/s13167-021-00239-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meghil MM, Cutler CW. Oral microbes and mucosal dendritic cells, “spark and flame” of local and distant inflammatory diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020;21:1643. doi: 10.3390/ijms21051643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melgar-Rodríguez S, Cafferata EA, Díaz NI, Peña MA, González-Osuna L, Rojas C, Sierra-Cristancho A, Cárdenas AM, Díaz-Zúñiga J, Vernal R. Natural Killer T (NKT) cells and periodontitis: potential regulatory role of NKT10 cells. Mediators of Inflammation. 2021;2021:5573937. doi: 10.1155/2021/5573937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moutsopoulos NM, Konkel JE. Tissue-specific immunity at the oral mucosal barrier. Trends in Immunology. 2018;39:276–287. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukuru M. Technical advance: decreased helper T cells and increased natural killer cells in chronic periodontitis analyzed by a novel method for isolating resident lymphocytes. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2012;92:683–692. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0212103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair S, Faizuddin M, Dharmapalan J. Role of autoimmune responses in periodontal disease. Autoimmune Diseases. 2014;2014:596824. doi: 10.1155/2014/596824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea MG, Joosten LAB, Latz E, Mills KHG, Natoli G, Stunnenberg HG, O’Neill LAJ, Xavier RJ. Trained immunity: A program of innate immune memory in health and disease. Science. 2016;352:aaf1098. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea MG, Domínguez-Andrés J, Barreiro LB, Chavakis T, Divangahi M, Fuchs E, Joosten LAB, van der Meer JWM, Mhlanga MM, Mulder WJM, Riksen NP, Schlitzer A, Schultze JL, Stabell Benn C, Sun JC, Xavier RJ, Latz E. Defining trained immunity and its role in health and disease. Nature Reviews. Immunology. 2020;20:375–388. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0285-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicu EA, Rijkschroeff P, Wartewig E, Nazmi K, Loos BG. Characterization of oral polymorphonuclear neutrophils in periodontitis patients: a case-control study. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18:149. doi: 10.1186/s12903-018-0615-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noz MP, Plachokova AS, Smeets EMM, Aarntzen E, Bekkering S, Vart P, Joosten LAB, Netea MG, Riksen NP. An explorative study on monocyte reprogramming in the context of periodontitis in vitro and in vivo. Frontiers in Immunology. 2021;12:695227. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.695227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orihuela-Campos RC, Tamaki N, Mukai R, Fukui M, Miki K, Terao J, Ito HO. Biological impacts of resveratrol, quercetin, and N-acetylcysteine on oxidative stress in human gingival fibroblasts. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition. 2015;56:220–227. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.14-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrù V, Steri M, Sidore C, Marongiu M, Serra V, Olla S, Sole G, Lai S, Dei M, Mulas A, Virdis F, Piras MG, Lobina M, Marongiu M, Pitzalis M, Deidda F, Loizedda A, Onano S, Zoledziewska M, Sawcer S, Devoto M, Gorospe M, Abecasis GR, Floris M, Pala M, Schlessinger D, Fiorillo E, Cucca F. Complex genetic signatures in immune cells underlie autoimmunity and inform therapy. Nature Genetics. 2020;52:1036–1045. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0684-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou N, Dimou N, Tsilidis KK, Banbury B, Martin RM, Lewis SJ, Kazmi N, Robinson TM, Albanes D, Aleksandrova K, Berndt SI, Timothy Bishop D, Brenner H, Buchanan DD, Bueno-de-Mesquita B, Campbell PT, Castellví-Bel S, Chan AT, Chang-Claude J, Ellingjord-Dale M, Figueiredo JC, Gallinger SJ, Giles GG, Giovannucci E, Gruber SB, Gsur A, Hampe J, Hampel H, Harlid S, Harrison TA, Hoffmeister M, Hopper JL, Hsu L, María Huerta J, Huyghe JR, Jenkins MA, Keku TO, Kühn T, La Vecchia C, Le Marchand L, Li CI, Li L, Lindblom A, Lindor NM, Lynch B, Markowitz SD, Masala G, May AM, Milne R, Monninkhof E, Moreno L, Moreno V, Newcomb PA, Offit K, Perduca V, Pharoah PDP, Platz EA, Potter JD, Rennert G, Riboli E, Sánchez M-J, Schmit SL, Schoen RE, Severi G, Sieri S, Slattery ML, Song M, Tangen CM, Thibodeau SN, Travis RC, Trichopoulou A, Ulrich CM, van Duijnhoven FJB, Van Guelpen B, Vodicka P, White E, Wolk A, Woods MO, Wu AH, Peters U, Gunter MJ, Murphy N. Physical activity and risks of breast and colorectal cancer: a Mendelian randomisation analysis. Nature Communications. 2020;11:597. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14389-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peres MA, Macpherson LMD, Weyant RJ, Daly B, Venturelli R, Mathur MR, Listl S, Celeste RK, Guarnizo-Herreño CC, Kearns C, Benzian H, Allison P, Watt RG. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet. 2019;394:249–260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson E, Glymour MM, Holmes MV, Kang H, Morrison J, Munafò MR, Palmer T, Schooling CM, Wallace C, Zhao Q, Smith GD. Mendelian randomization. Nature Reviews. Methods Primers. 2022;2:1–21. doi: 10.1038/s43586-021-00092-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkein HA, Papapanou PN, Genco R, Sanz M. Mechanisms underlying the association between periodontitis and atherosclerotic disease. Periodontology 2000. 2020;83:90–106. doi: 10.1111/prd.12304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel A, Seidel CL, Weider M, Junker R, Gölz L, Schmetzer H. Influence of natural killer cells and natural killer T cells on periodontal disease: a systematic review of the current literature. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020;21:9766. doi: 10.3390/ijms21249766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shungin D, Haworth S, Divaris K, Agler CS, Kamatani Y, Keun Lee M, Grinde K, Hindy G, Alaraudanjoki V, Pesonen P, Teumer A, Holtfreter B, Sakaue S, Hirata J, Yu Y-H, Ridker PM, Giulianini F, Chasman DI, Magnusson PKE, Sudo T, Okada Y, Völker U, Kocher T, Anttonen V, Laitala M-L, Orho-Melander M, Sofer T, Shaffer JR, Vieira A, Marazita ML, Kubo M, Furuichi Y, North KE, Offenbacher S, Ingelsson E, Franks PW, Timpson NJ, Johansson I. Genome-wide analysis of dental caries and periodontitis combining clinical and self-reported data. Nature Communications. 2019;10:2773. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10630-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrivankova VW, Richmond RC, Woolf BAR, Davies NM, Swanson SA, VanderWeele TJ, Timpson NJ, Higgins JPT, Dimou N, Langenberg C, Loder EW, Golub RM, Egger M, Davey Smith G, Richards JB. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using mendelian randomisation (STROBE-MR): explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2021;375:n2233. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreenivasan PK, Prasad KVVK. Increase in the level of oral neutrophils with gingival inflammation - A population survey. The Saudi Dental Journal. 2022;34:795–801. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2022.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz O, Hoch S, Avniel-Polak S, Gavish K, Eli-Berchoer L, Wilensky A, Nussbaum G. CX3CR1hi monocyte/macrophages support bacterial survival and experimental infection-driven bone resorption. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2016;213:1505–1515. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbanck M, Chen CY, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nature Genetics. 2018;50:693–698. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0099-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuckovic D, Bao EL, Akbari P, Lareau CA, Mousas A, Jiang T, Chen M-H, Raffield LM, Tardaguila M, Huffman JE, Ritchie SC, Megy K, Ponstingl H, Penkett CJ, Albers PK, Wigdor EM, Sakaue S, Moscati A, Manansala R, Lo KS, Qian H, Akiyama M, Bartz TM, Ben-Shlomo Y, Beswick A, Bork-Jensen J, Bottinger EP, Brody JA, van Rooij FJA, Chitrala KN, Wilson PWF, Choquet H, Danesh J, Di Angelantonio E, Dimou N, Ding J, Elliott P, Esko T, Evans MK, Felix SB, Floyd JS, Broer L, Grarup N, Guo MH, Guo Q, Greinacher A, Haessler J, Hansen T, Howson JMM, Huang W, Jorgenson E, Kacprowski T, Kähönen M, Kamatani Y, Kanai M, Karthikeyan S, Koskeridis F, Lange LA, Lehtimäki T, Linneberg A, Liu Y, Lyytikäinen L-P, Manichaikul A, Matsuda K, Mohlke KL, Mononen N, Murakami Y, Nadkarni GN, Nikus K, Pankratz N, Pedersen O, Preuss M, Psaty BM, Raitakari OT, Rich SS, Rodriguez BAT, Rosen JD, Rotter JI, Schubert P, Spracklen CN, Surendran P, Tang H, Tardif J-C, Ghanbari M, Völker U, Völzke H, Watkins NA, Weiss S, VA Million Veteran Program. Cai N, Kundu K, Watt SB, Walter K, Zonderman AB, Cho K, Li Y, Loos RJF, Knight JC, Georges M, Stegle O, Evangelou E, Okada Y, Roberts DJ, Inouye M, Johnson AD, Auer PL, Astle WJ, Reiner AP, Butterworth AS, Ouwehand WH, Lettre G, Sankaran VG, Soranzo N. The polygenic and monogenic basis of blood traits and diseases. Cell. 2020;182:1214–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace C. Eliciting priors and relaxing the single causal variant assumption in colocalisation analyses. PLOS Genetics. 2020;16:e1008720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White P, Sakellari D, Roberts H, Risafi I, Ling M, Cooper P, Milward M, Chapple I. Peripheral blood neutrophil extracellular trap production and degradation in chronic periodontitis. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2016;43:1041–1049. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilensky A, Segev H, Mizraji G, Shaul Y, Capucha T, Shacham M, Hovav AH. Dendritic cells and their role in periodontal disease. Oral Diseases. 2014;20:119–126. doi: 10.1111/odi.12122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue H, Shen X, Pan W. Constrained maximum likelihood-based Mendelian randomization robust to both correlated and uncorrelated pleiotropic effects. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2021;108:1251–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki K, Ohsawa Y, Yoshie H. Elevated proportion of natural killer T cells in periodontitis lesions: a common feature of chronic inflammatory diseases. The American Journal of Pathology. 2001;158:1391–1398. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64090-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Pang X, Li Z, Chen Z, Wang Y. Immunomodulation in the treatment of periodontitis: progress and perspectives. Frontiers in Immunology. 2021;12:781378. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.781378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X, Liu B, Bai Y, Cao Y, Lin S, Lyu L, Meng H, Dai Y, Ye D, Pan W, Wang Z, Mao Y, Chen Q. Genetic evidence strengthens the bidirectional connection between gut microbiota and periodontitis: insights from a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2023;21:674. doi: 10.1186/s12967-023-04559-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Wang N, Rui Y, Xia Y, Xiong S, Xia X. New insight of metabolomics in ocular diseases in the context of 3P medicine. The EPMA Journal. 2023;14:53–71. doi: 10.1007/s13167-023-00313-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zidar A, Kristl J, Kocbek P, Zupančič Š. Treatment challenges and delivery systems in immunomodulation and probiotic therapies for periodontitis. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery. 2021;18:1229–1244. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2021.1908260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuber V, Colijn JM, Klaver C, Burgess S. Selecting likely causal risk factors from high-throughput experiments using multivariable Mendelian randomization. Nature Communications. 2020;11:29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13870-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]