Abstract

Introduction

Laparoscopic surgery (LAP) is now recognized as the standard procedure for colorectal surgery. However, the standard surgery for ulcerative colitis (UC) is total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA), which may be an overly complex procedure to complete laparoscopically. We conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy as well as the advantages and disadvantages of LAP-IPAA in patients with UC stratified by the outcome of interest.

Method

We performed a systematic literature review by searching the PubMed/MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library, and the Japan Centra Reuvo Medicina databases from inception until January 2023. Meta-analyses were performed for surgical outcomes, including morbidity and surgical course, to evaluate the efficacy of LAP-IPAA.

Results

A total of 707 participants, including 341 LAP and 366 open surgery (OPEN) patients in 9 observational studies and one randomized controlled study, were included. From the results of the meta-analyses, the odds ratio (OR) of total complications in LAP was 1.12 (95% CI: 0.58–2.17, p = 0.74). The OR of mortality for LAP was 0.38 (95% CI: 0.08–1.92, p = 0.24). Although the duration of surgery was extended in LAP (mean difference (MD) 118.74 min (95% CI: 91.67–145.81), p < 0.01) and hospital stay were not shortened, the duration until oral intake after surgery was shortened in LAP (MD −2.10 days (95% CI: −3.52–0.68), p = 0.004).

Conclusions

During IPAA for UC, a similar morbidity rate was seen for LAP and OPEN. Although LAP necessitates extended surgery, there may be certain advantages to this procedure, including easy visibility during the surgical procedure or a shortened time to oral intake after surgery.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis, Laparoscopic surgery, Restorative proctocolectomy, Ileal pouch anal anastomosis

Introduction

Currently, laparoscopic surgery (LAP) is the standard procedure for colorectal disease, just as it is for multi-organ surgery. A meta-analysis for studies reported between 2007 and 2015 concluded that LAP can result in smaller incisions, a shorter length of hospital stay (LOS), and less morbidity without worsening oncological outcomes for colorectal cancer [1]. Recently, it was reported that LAP is also useful for inflammatory bowel disease, including ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease [2, 3]. However, although the standard procedure for UC has been restorative proctocolectomy (RP) with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) since 1978 [4], LAP-IPAA has had negative impacts because of the difficulty and complexity of the surgical procedure [5–7]. However, surgical devices have been recently developed which may make LAP-IPAA easier. Therefore, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy as well as the advantages and disadvantages of LAP in patients with UC stratified by the outcome of interest.

Materials and Methods

Literature Search Strategy

We performed a comprehensive search in the PubMed/MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library, and the Japan Centra Reuvo Medicina (Ichushi Web, Japanese search engine) databases on January 3, 2023. The following free text words and medical subject headings were used for the search: “ulcerative colitis” and “laparoscopic surgery” {(“colitis, ulcerative” [MeSH Terms] OR (“colitis” [All Fields] AND “ulcerative” [All Fields]) OR “ulcerative colitis” [All Fields] OR (“ulcerative” [All Fields] AND “colitis” [All Fields])} AND (“laparoscopy” [MeSH Terms] OR “laparoscopy” [All Fields] OR (“laparoscopic” [All Fields] AND “surgery” [All Fields]) OR “laparoscopic surgery” [All Fields]). The publication period was not limited in the search. Cross-references and related articles were also reviewed. The studies were evaluated, and other hand-selected papers were added manually.

Study Eligibility

Studies meeting the following criteria were included in the meta-analysis. (1) Participants: patients who were treated with laparoscopic or open restorative proctocolectomy. Patients with UC were primarily selected; however, those with indeterminate colitis (IC), familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), and other diseases such as Crohn’s disease, adenoma, or adenocarcinoma were also included because some studies included these diseases but did not evaluate them independently. (2) Intervention: patients who were treated with LAP-IPAA. (3) Comparison: patients who were treated with open surgery (OPEN). (4) Outcomes: mortality, morbidity, amount of intraoperative bleeding, surgical time, LOS, or duration until oral intake days after surgery. (5) Study design: prospective studies with or without randomization and observational comparative studies.

The language of publication was restricted to English. Articles with in vitro studies or animal studies and those without a proper number of events were not included. Studies with participants exhibiting a disease other than UC were included; however, studies in which UC patients comprised less than 50% of the overall participants were excluded. The minimal number of participants was not limited. Studies involving hand-assisted LAP were not included. Subtotal colectomy (STC) or total proctocolectomy (TPC) without pouch reconstruction was not included. The article selection was independently performed and confirmed by the coauthors.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A standard data entry form was designed for data extraction. Three reviewers who are experts in the medical or surgical treatment of inflammatory bowel disease independently extracted the available data from the studies. The extracted data included the author’s name, publication year, study design, patient characteristics, and types of outcomes, namely, mortality and morbidity. Any disagreement among these three authors was resolved by discussion with all authors at a consensus meeting.

Endpoint

The primary endpoint of this systematic review and meta-analysis was surgical mortality and morbidity after RP (total proctocolectomy with IPAA). Morbidity included total complications, wound infection (incisional surgical site infection (SSI), anastomotic leakage/abdomino/pelvic abscess (organ/space SSI), or postoperative ileus/bowel obstruction. The secondary endpoints were the duration of surgery (minutes), amount of blood loss (mL), LOS (days), or duration until oral intake days after surgery (days). Oral intake included either liquid or diet.

Assessment of Risk of Bias and Certainty of Evidence

The risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions (ROBINS-I) tool was used for the assessment of observational studies [8]. The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) approach [9] was used to grade the certainty of evidence of the outcomes.

Statistical Analysis

We performed a random-effects meta-analysis for the outcomes of interest. Outcomes were calculated using Windows Review Manager Software 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Center, The Collaboration, 2014, Copenhagen, Denmark) to obtain the odds ratios (ORs) or the mean difference (MD) with the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The other statistical analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 19.0. Categorical variables were compared between the 2 groups using the Pearson χ2 test. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Heterogeneity was measured using I-squared and tau-squared indexes, testing the null hypothesis that all studies shared a common effect size.

Results

Study Selection

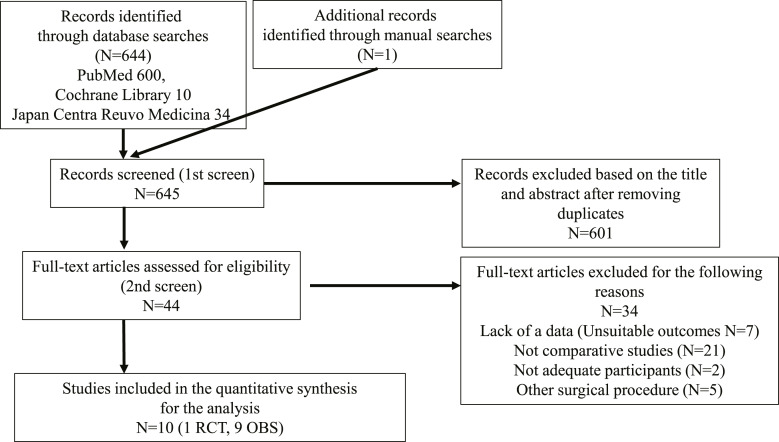

A total of 645 records were identified through database searches. After the removal of duplicates and screening of the titles and abstracts, the full texts of 44 studies were assessed for eligibility. Ultimately, 10 studies [7, 10–18] met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1; Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the literature search according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA).

Table 1.

The characteristics of the included studies

| Author | Study design | Total participants | LAP | OPEN | Male | Age | BMI, kg/m2 | Disease | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAP | OPEN | LAP | OPEN | LAP | OPEN | UC | FAP | others | |||||

| Schmitt [7] (1994) | OBS | 42 | 22 | 20 | 11 | 11 | 31 (12–59) | 34 (17–64) | NA | NA | 31 | 10 | 1 |

| Marcello [10] (2000) | OBS | 40 | 20 | 20 | 15 | 15 | 25 (12–61) | 26 (9–61) | 24 (18–32) | 24 (18–30) | 26 | 14 | 0 |

| Hashimoto [11] (2001) | OBS | 24 | 11 | 13 | 4 | 7 | 30 (19–47) | 30 (18–49) | NA | NA | 12 | 12 | 0 |

| Araki [12] (2001) | OBS | 32 | 21 | 11 | 8 | 2 | 27.2±8.1 | 31.1±11.2 | 31.2±4.5 | 33.1±4.8 | 32 | 0 | 0 |

| Dunker [13] (2001) | OBS | 32 | 15 | 17 | 4 | 9 | NA | NA | 23.6±4.6 | 24.5±3.2 | 28 | 4 | 0 |

| Larson [14] (2006) | OBS | 300 | 100 | 200 | 40 | 80 | 32 (17–34) | 32 (17–64) | 22.4 (17–34) | 23 (16–32) | 289 | 11 | 0 |

| Flores [15] (2010) | OBS | 7 | 3 | 4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Schiessling [16] (2013) | RCT | 41 | 21 | 20 | 18 | 8 | 36.9±17.0 | 39.2±14.3 | 25.2±4.4 | 24.7±4.4 | 24 | 17 | 0 |

| Mineccia [17] (2018) | OBS | 78 | 30 | 48 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 78 | 0 | 0 |

| Duraes [18] (2018) | OBS | 152 | 119 | 33 | 66 | 1 | 37.0±15.0 | 29.3±10.8 | 24.7±5.0 | 20.3±3.0 | 108 | 26 | 18 |

LAP, laparoscopic surgery; OPEN, open surgery; BMI, body mass index; UC, ulcerative colitis; FAP, familial adenomatous polyposis; OBS, observational study; RCT, randomized controlled trial; NA, not available.

Continuous variables are indicated as median with range in paresis or mean ± standard deviation.

Characteristics of the Included Studies

The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. One of 10 studies was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) [16]. The remaining 9 studies were observational studies (OBSs).

Quality of the OBSs and Certainty of Evidence

Using the GRADE approach, all outcomes had a low-to-moderate grade for the certainty of evidence (online suppl. Table; for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000535832).

Outcomes of the Included Studies

A total of 707 participants, including 341 patients in the LAP group and 366 patients in the OPEN group in 9 OBSs, were included for analyses. All patients were subjected to total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) as an initial surgery for restorative proctocolectomy.

Some studies included patients with FAP, IC, or other diseases (Table 1). There was no information on disease severity, nutritional/immunological status, degree of anemia, or use of immunosuppressive agents before surgery.

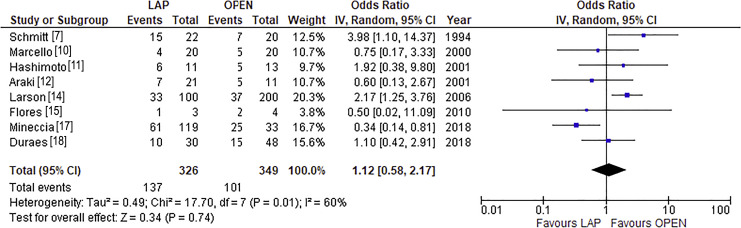

Meta-Analysis of Total Complications and Mortality in IPAA

A forest plot with a random-effects model for total complications is shown in Figure 2. The OR of total complications in the LAP group was 1.12 (95% CI: 0.58–2.17, p = 0.74), with a moderate risk of heterogeneity (I2 = 60%).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot for total complications. The OR in LAP was 1.12 (95% CI: 0.58–2.17), with an I2 of 60% according to the random-effects model.

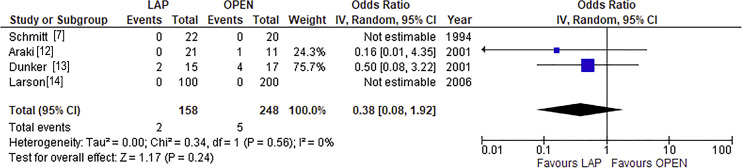

A forest plot with a random-effects model for mortality is shown in Figure 3. The OR of mortality in the LAP group was 0.38 (95% CI: 0.08–1.92, p = 0.24), with a low risk of heterogeneity (I2 = 0%).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot for mortality. The OR in LAP was 0.38 (95% CI: 0.08–1.92), with an I2 of 0% according to the random-effects model.

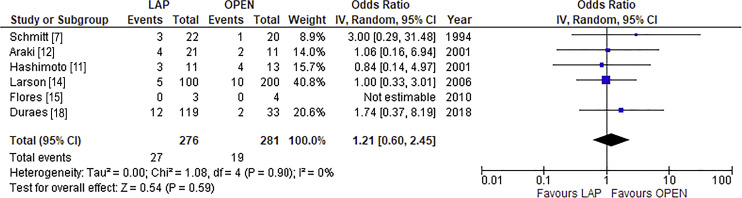

Meta-Analysis for Each Complication in IPAA

Incisional SSI

A forest plot with a random-effects model for incisional SSI is shown in Figure 4. The OR of incisional SSI in the LAP group was 1.21 (95% CI: 0.60–2.45, p = 0.59).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot for incisional surgical site infection. The OR in LAP was 1.21 (95% CI: 0.60–2.45), with an I2 of 0% according to the random-effects model.

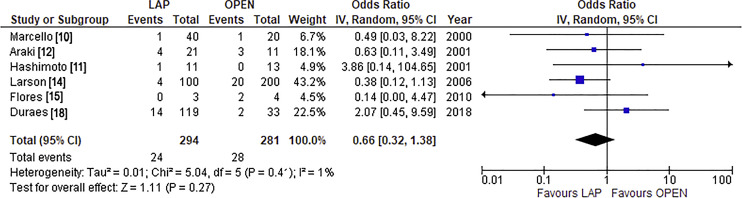

Organ/Space SSI

A forest plot with a random-effects model for organ/space SSI is shown in Figure 5. The OR of organ/space SSI in the LAP group was 0.66 (95% CI: 0.32–1.38, p = 0.27).

Fig. 5.

Forest plot for organ/space surgical site infection. The OR in LAP was 0.66 (95% CI: 0.32–1.38), with an I2 of 1% according to the random-effects model.

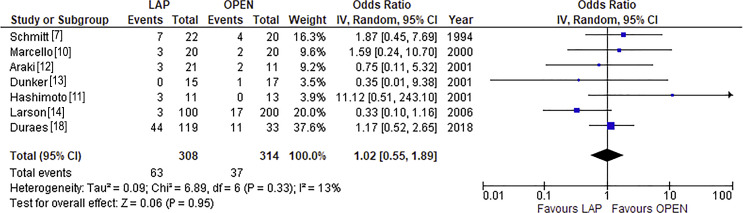

Bowel Obstruction/Ileus

A forest plot with a random-effects model for bowel obstruction/ileus is shown in Figure 6. The OR of bowel obstruction/ileus in the LAP group was 1.02 (95% CI: 0.55–1.89, p = 0.95).

Fig. 6.

Forest plot for bowel obstruction/ileus. The OR in LAP was 1.02 (95% CI: 0.55–1.89), with an I2 of 13% according to the random-effects model.

Meta-Analysis for Intraoperative Outcomes in IPAA

Duration of Surgery

The duration of surgery in the LAP group was significantly extended, and the MD was 118.74 min (95% CI: 91.67–145.81 min, p < 0.01).

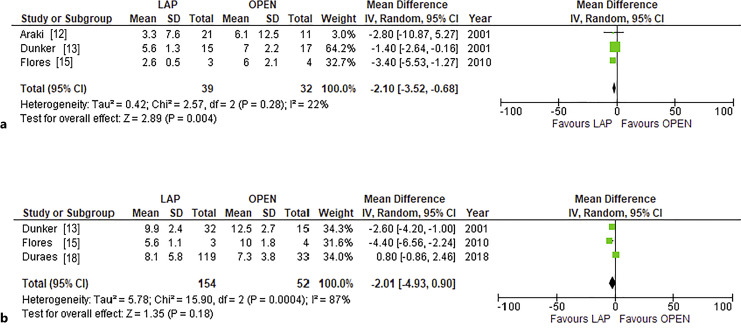

Duration until Oral Intake after Surgery

A forest plot with a random-effects model for duration until oral intake is shown in Figure 7a. The duration until oral intake in the LAP group was shortened, and the MD was −2.10 days (95% CI: −3.52 to 0.68 days, p = 0.004).

Fig. 7.

Forest plot for postoperative recovery. The mean differences in (a) duration until oral intake after surgery and (b) length of hospital stay in LAP were −2.10 days (95% CI: −3.52 to 0.68 days) and −2.01 days (95% CI: −4.93 to 0.90 days), respectively.

Length of Hospital Stay

A forest plot with a random-effects model for LOS is shown in Figure 7b. The LOS was similar, and the MD of LOS was −2.01 days (95% CI: −4.93 to 0.90 days, p = 0.18).

Outcomes in 1 RCT

One RCT compared 21 LAP cases and 20 OPEN cases among patients with UC and FAP; however, the RCT was stopped prematurely due to insufficient patient recruitment. The study included 17 patients with FAP and 24 with UC. The amount of intraoperative bleeding, which was set as the primary outcome, was similar between LAP and OPEN (261.5 ± 195.4 mL and 228.1 ± 119.5 mL, respectively). The duration of surgery was longer in LAP (313.9 ± 52 min) than in OPEN (200.2 ± 53.8 min). The incidences of organ/space SSI were similar between LAP and OPEN (4/21 [19%] and 4/20 [20%], respectively). Only LOS was compared to each disease independently. The LOS for LAP was shorter than that for OPEN (11.22 ± 4.8 days and 26.4 ± 4.3 days, respectively).

Discussion

This meta-analysis was performed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of laparoscopic proctocolectomy with ileal pouch reconstruction in patients with UC. Although the duration of surgery was significantly longer in LAP than in OPEN, total number of complications was similar. Alternatively, LAP may have better postoperative recovery. These findings were similar to those of a previous meta-analysis and review [2, 19].

In a previous Cochrane analysis [20], the outcomes of body image and cosmetic appearance were evaluated, but this outcome was not included in this review because most of the included studies did not mention it. However, this outcome should be evaluated further.

Regarding the comparison between OPEN and LAP, OPEN might be performed in patients with poorer conditions, including high disease severity, malnutritional, or anemic status. We need to evaluate both procedures against the same background. On the other hand, LAP, which provides an easy and extended view, may avoid injury to the nerves involved in sexual function and urination, which can lead to fertility or sexual disfunction during manipulation of the lower rectum. This effect should also be evaluated in further studies.

In view of fertility, sexual or urinary disfunction, or failure of the IPAA procedure in terms of surgical manipulation, robotic surgery may have some advantages over LAP. A recent meta-analysis reported that robotic surgery is safe for IPAA in cases of UC and FAP, although the surgical time is extended [21]. However, there are still few studies about robotic surgery for IPAA; robotic surgery is not a universal procedure for IPAA in patients with UC, and there were some differences between robotic surgery and LAP, including the complexity of the procedure and the medical cost. Therefore, we did not include the studies of robotic surgery in this review; however, such surgery may be useful even for IPAA, as mentioned above. We need to evaluate robotic surgery in the future.

In this series, most of the included studies included elective surgery, although there were few descriptions of disease severity. We could not analyze results restricted to each level of severity; however, outcomes may obviously be affected by disease severity. Notably, the results of these studies were evaluated for mild or moderate disease, which are indications for elective proctocolectomy with pouch reconstruction. LAP is not always recommended for severe UC, which involves toxic megacolon, perforation, and massive bleeding and is an indication for emergent surgery. Candidacy for LAP should be determined according to the patient’s condition not only in an emergent setting but also even under urgent surgery.

Regarding the IPAA procedure and adhesion, LAP may lead to a long cuff during the IPAA procedure because manipulations for a short cuff might be difficult in LAP. Therefore, several concerns including increased risk of complications related to a long cuff may arise as long-term problems after surgery. The LAP-IPAA procedure may have a benefit of a reduced risk of adhesion-related complications. However, a lack of adhesions may cause the development of pouch volvulus, although the occurrence of this complication is unusual [22]. Therefore, we should evaluate long-term surgical complications.

This study had some limitations. First, this meta-analysis included only 9 OBSs with low-to-moderate evidence levels. Therefore, the evidence level of this meta-analysis is not high. Second, the definitions of complications, including infectious complications, bowel obstruction, dehydration, venous thrombosis, hernia, etc., were slightly different among the studies. We should perform an analysis that is distinct from the extracted, representative complications. Moreover, the selected studies were reported approximately between 1994 and 2018. Therefore, the heterogeneity might be high in the analysis for total complications. Third, the definitions of the starting day of oral intake were slightly different among studies. Fourth, some studies included patients with FAP, IC, or other disease who underwent the same restorative proctocolectomy. The differentiation of disease might influence surgical outcomes. Fifth, we did not analyze medical costs and cosmetic aspects in this series. These outcomes are also important and should be evaluated for LAP. Sixth, as mentioned above, LAP-IPAA and IPAA, even with the OPEN procedure, are not always suitable for cases with severe or fulminant disease activity. This analysis did not include subtotal colectomy, which is frequently performed in severe conditions such as peritonitis with perforation, toxic megacolon, or severe/fulminant disease activity. Notably, most participants in this analysis may have had mild-to-moderate disease severity. The efficacy and safety for severe UC should be evaluated in further studies as well as whether LAP is suitable for emergent situations.

In conclusion, the duration of surgery was extended in LAP for UC; however, the mortality and morbidity were similar between LAP and OPEN in patients who underwent IPAA. Moreover, although the LOS was similar, the duration until oral intake in the LAP group was shortened. Alternatively, the visibility of LAP may facilitate surgical procedures. We provide evidence for the efficacy and safety of LAP-IPAA that should be confirmed in further nationwide observational or prospective studies in the future.

Statement of Ethics

We followed PRISMA guidelines. An ethics statement is not applicable because this study was based exclusively on published literature.

Conflict of Interest Statement

MU declares lecture fees from Tanabe Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, EA Pharmaceuticals, and Kyorin Pharmaceuticals. None of the other authors have conflicts of interest related to this study to declare.

Funding Sources

This publication has no funding support.

Author Contributions

Conception, design, analyses, and writing of the article: Motoi Uchino. Literature search and first literature (abstract) assessment: Kentaro Nagano, Kurando Kusunoki, Kei Kimura, Kozo Kataoka, and Naohito Beppu. Secondary literature assessment and review: Motoi Uchino, Yuki Horio, and Ryuichi Kuwahara. Assessment of risk of bias and certainty of evidence: Motoi Uchino and Ryuichi Kuwahara. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: Motoi Uchino, Hiroki Ikeuchi, and Masataka Ikeda. Discussion at a consensus meeting: all authors. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This publication has no funding support.

Data Availability Statement

Included data are available in each reported article. These studies are openly available in the references. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Kulkarni N, Arulampalam T. Laparoscopic surgery reduces the incidence of surgical site infections compared to the open approach for colorectal procedures: a meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2020;24(10):1017–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hata K, Kazama S, Nozawa H, Kawai K, Kiyomatsu T, Tanaka J, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for ulcerative colitis: a review of the literature. Surg Today. 2015;45(8):933–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fichera A, Peng SL, Elisseou NM, Rubin MA, Hurst RD. Laparoscopy or conventional open surgery for patients with ileocolonic Crohn's disease? A prospective study. Surgery. 2007;142(4):566–71.e1; discussion 571.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parks AG, Nicholls RJ. Proctocolectomy without ileostomy for ulcerative colitis. Br Med J. 1978;2(6130):85–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sardinha TC, Wexner SD. Laparoscopy for inflammatory bowel disease: pros and cons. World J Surg. 1998;22(4):370–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wexner SD, Johansen OB, Nogueras JJ, Jagelman DG. Laparoscopic total abdominal colectomy. A prospective trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35(7):651–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schmitt SL, Cohen SM, Wexner SD, Nogueras JJ, Jagelman DG. Does laparoscopic-assisted ileal pouch anal anastomosis reduce the length of hospitalization? Int J Colorectal Dis. 1994;9(3):134–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):401–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marcello PW, Milsom JW, Wong SK, Hammerhofer KA, Goormastic M, Church JM, et al. Laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy: case-matched comparative study with open restorative proctocolectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43(5):604–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hashimoto A, Funayama Y, Naito H, Fukushima K, Shibata C, Naitoh T, et al. Laparascope-assisted versus conventional restorative proctocolectomy with rectal mucosectomy. Surg Today. 2001;31(3):210–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Araki Y, Ishibashi N, Ogata Y, Shirouzu K, Isomoto H. The usefulness of restorative laparoscopic-assisted total colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Kurume Med J. 2001;48(2):99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dunker MS, Bemelman WA, Slors JF, van Duijvendijk P, Gouma DJ. Functional outcome, quality of life, body image, and cosmesis in patients after laparoscopic-assisted and conventional restorative proctocolectomy: a comparative study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44(12):1800–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Larson DW, Cima RR, Dozois EJ, Davies M, Piotrowicz K, Barnes SA, et al. Safety, feasibility, and short-term outcomes of laparoscopic ileal-pouch-anal anastomosis: a single institutional case-matched experience. Ann Surg. 2006;243(5):667–72; discussion 670-672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Flores P, Bailez MM, Cuenca E, Fraire C. Comparative analysis between laparoscopic (UCL) and open (UCO) technique for the treatment of ulcerative colitis in pediatric patients. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010;26(9):907–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schiessling S, Leowardi C, Kienle P, Antolovic D, Knebel P, Bruckner T, et al. Laparoscopic versus conventional ileoanal pouch procedure in patients undergoing elective restorative proctocolectomy (LapConPouch Trial)-a randomized controlled trial. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398(6):807–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mineccia M, Cravero F, Massucco P, Portigliotti L, Bertolino F, Daperno M, et al. Laparoscopic vs open restorative proctocolectomy with IPAA for ulcerative colitis: impact of surgical technique on creating a well functioning pouch. Int J Surg. 2018;55:201–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duraes LC, Schroeder DA, Dietz DW. Modified pfannenstiel open approach as an alternative to laparoscopic total proctocolectomy and IPAA: comparison of short- and long-term outcomes and quality of life. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(5):573–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bartels SA, Gardenbroek TJ, Ubbink DT, Buskens CJ, Tanis PJ, Bemelman WA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopicversus open colectomy with end ileostomy for non-toxic colitis. Br J Surg. 2013;100(6):726–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ahmed Ali U, Keus F, Heikens JT, Bemelman WA, Berdah SV, Gooszen HG, et al. Open versus laparoscopic (assisted) ileo pouch anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;1:CD006267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Flynn J, Larach JT, Kong JCH, Warrier SK, Heriot A. Robotic versus laparoscopic Ileal Pouch-Anal Anastomosis (IPAA): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36(7):1345–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jawoosh M, Haffar S, Deepak P, Meyers A, Lightner AL, Larson DW, et al. Volvulus of the ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a meta-narrative systematic review of frequency, diagnosis, and treatment outcomes. Gastroenterol Rep. 2019;7(6):403–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Included data are available in each reported article. These studies are openly available in the references. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.