Abstract

Background

Mounting evidence indicates that although some plant-based diets are healthful, others are not. Changes in the gut microbiome and microbiome-dependent metabolites, such as trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), may explain differential health effects of plant-based diets. However, human data are sparse on whether qualitatively distinct types of plant-based diets differentially affect gut microbiome diversity, composition, particularly at the species level, and/or metabolites.

Objectives

We aimed to examine cross-sectional associations of different plant-based indices with adult gut microbiome diversity, composition, and the metabolite TMAO.

Methods

We studied 705 adults in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging with data for diet, fecal microbiome (shotgun metagenomic sequencing), and key covariates. We derived healthful plant-based diet index (hPDI) and unhealthful plant-based diet index (uPDI) using data from food frequency questionnaires. We examined plant-based diet indices with microbiome α-diversity (richness and evenness measures), β-diversity (Bray–Curtis and UniFrac measures), composition (species level), and plasma TMAO. We used regression models to determine associations before and after adjustment for age, sex, education, physical activity, smoking status, body mass index, and total energy intake.

Results

The analytic sample (mean age, 71.0 years, SD = 12.8 years) comprised 55.6% female and 67.5% non-Hispanic White participants. hPDI was positively and uPDI negatively associated with microbiome α-diversity, driven by microbial evenness (Pielou P < 0.05). hPDI was also positively associated with relative abundance of 3 polysaccharide-degrading bacterial species (Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Eubacterium eligens, and Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron) and inversely associated with 6 species (Blautia hydrogenotrophica, Doreasp CAG 317, Eisenbergiella massiliensis, Sellimonas intestinalis, Blautia wexlerae, and Alistipes shahii). Furthermore, hPDI was inversely associated with TMAO. Associations did not differ by age, sex, or race.

Conclusions

Greater adherence to a healthful plant-based diet is associated with microbiome features that have been linked to positive health; adherence to an unhealthful plant-based diet has opposing or null associations with these features.

Keywords: gut microbiome, diet, dietary pattern, healthful plant-based diet index, unhealthful plant-based diet index, overall plant-based diet index

Introduction

Plant-based diets (ie, dietary patterns higher in plant-based foods and lower in animal-based foods) are increasing in popularity owing to their benefits for human and planetary health [1]. Observational studies have demonstrated that dietary patterns higher in plant-based foods are associated with a lower risk of morbidity and/or mortality owing to cardiovascular diseases [2] and certain types of cancer [3,4], and they are more environmentally sustainable [5,6]. However, more nuanced evidence suggests that not all variations of plant-based diets benefit human health [7]. For example, a healthy plant-based diet, comprising whole grains, fruit, vegetables, and nuts, has been associated with a lower risk of obesity, coronary artery disease, kidney diseases, type 2 diabetes, and some types of cancers [[8], [9], [10], [11], [12]] and lower risk and severity of COVID-19 infections [13]. By contrast, an unhealthy plant-based diet, such as one rich in sweetened beverages, refined grains, fried potatoes, and sweets and desserts, is associated with an elevated risk of heart disease, kidney disease, colorectal cancer, and obesity [[8], [9], [10],12].

The mechanisms by which qualitatively different plant-based diets are either supportive or detrimental to health are not yet fully understood. One hypothesis is that plant-based diets alter health outcomes through their influence on the intestinal (gut) microbiome [14,15]. Previous studies have shown that intake of diets rich in healthy plant-based foods are associated with higher abundance of polysaccharide-degrading bacteria, such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Eubacterium eligens [16,17]. In separate studies, these same species have been associated with lower levels of inflammation [18,19]. To our knowledge, only 2 studies to date—the Men’s Lifestyle Validation Study (MLVS) and the Personalised Responses to Dietary Composition Trial (PREDICT1)—have investigated whether a healthful plant-based diet index (hPDI) compared with an unhealthful plant-based diet index (uPDI) have differential associations with gut microbiome features [16,17]. Using shotgun sequencing data, the MLVS investigators identified 7 differentially abundant species [at false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05] associated with hPDI, and the PREDICT1 investigators found ∼20 species associated with hPDI (at FDR < 0.2). Neither study identified species associated with uPDI [16,17].

The health effects of plant-based diets might also be partially due to the dietary patterns’ impact on circulating trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), a microbiome-dependent metabolite that has been positively associated with risk of several chronic diseases, including cardiometabolic diseases and cancer [20]. TMAO is naturally present in fish and can be derived through microbial bioconversion of amino acids found in animal products and plant products. For example, the gut microbiome can produce TMAO from choline and carnitine (ie, amino acids highly abundant in eggs and beef) or from betaine (ie, an amino acid mostly commonly found in beets, spinach, and whole grains, such as quinoa, wheat, oat bran, brown rice, and barley) [20,21]. Thus, circulating TMAO concentrations are determined by a diet–microbiome interaction, which depends on the relative dietary intake and microbial community composition of the population under study. Only 1 previous study, the MLVS study, investigated and reported associations of hPDI and uPDI with circulating TMAO, finding hPDI was positively and uPDI negatively associated with TMAO concentrations [22]. However, this study was only conducted in US males.

In this study, we studied a racially diverse cohort of United States males and females to examine the association of qualitatively distinct plant-based diet indices (PDIs) with gut microbiome diversity and composition and circulating TMAO. We use whole-genome shotgun metagenomic sequencing to identify bacterial species. We hypothesized that greater adherence to hPDI, but not uPDI, is associated with higher microbiome α-diversity and higher abundance of bacterial species adept at degradation of indigestible plant polysaccharides (eg, F. prausnitzii and E. eligens).

Although our primary interest was in the comparison of hPDI and uPDI, we also compared findings with an overall plant-based index (PDI), which measures plant food intake agnostic to potential healthful effects of those foods. We hypothesized that associations identified in the hPDI or uPDI are attenuated for the overall PDI. Finally, we also hypothesized that higher scores in all 3 plant-based indices would be inversely associated TMAO because TMAO is naturally occurring in fish and TMAO precursors (eg, choline and carnitine) are abundant in animal products [20].

Methods

Study design

The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA) is an ongoing prospective cohort study supported and maintained since 1958 by the National Institute on Aging [23]. Participants in BLSA are from the Washington DC–Baltimore metropolitan area [23]. For BLSA, study investigators recruited and enrolled community-residing volunteers who did not have major chronic health conditions at enrollment [23]. The inclusion criteria for BLSA were as follows: participants had to be aged ≥20 years, have a body weight of fewer than 300 pounds or a BMI of <40 kg/m2, and be free of mobility, cognitive impairments, and chronic diseases, except for controlled hypertension. A more comprehensive description of the inclusion/exclusion criteria has been previously published [24].

Each study visit was conducted over 3 days at the National Institute on Aging’s Intramural Research Program (NIA IRP) Clinical Research Unit [23]. During these visits, participants underwent comprehensive physical and laboratory examinations [23]. In addition, participants provided information on their medical history and completed a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) [23].

Our study used data from a subset of BLSA participants who provided stool samples at 1 or more attended visits between 2013 and 2019, resulting in 1810 fecal samples from 928 participants. We show the study flow diagram for our analytic sample in Supplemental Figure 1. We excluded fecal samples with >70% unknown taxa (n = 6) and fecal samples with a sequencing depth of <100,000 reads (n = 4). Of the 1800 fecal samples remaining, we chose the earliest available sample for each participant, resulting in 925 participants and fecal samples. From these participants, we excluded individuals who were missing dietary intake information (n = 172), who had improbable energy intake [females <500 or >3500 kcal and males <700 or >4500 kcal] (n = 26) [10], who were missing key covariates (n = 14) and who had taken antibiotics before stool collection (n = 8). Our final analytic sample had 705 adults. The NIH institutional review board approved the study protocol, and all participants provided informed consent at each visit.

Fecal sample collection and processing

Each participant provided their own stool sample during the study visits, which was collected using stool collection bowl provided by study staff. Participants returned the stool samples to the study staff at their examination visit. On receipt of the stool samples, study staff transferred them into an empty storage tube, stored at 4 °C [25] and aliquoted into a 50-mL Falcon tube without buffer and stored at −80 °C within 24 h.

DNA extraction, sequencing, and annotation

Diversigen extracted the bacterial DNA and conducted whole-genome shotgun sequencing. They used a Qiagen PowerFecal Pro extraction kit to extract DNA from fecal samples and prepped the library with a Nextera XT DNA library preparation kit [26]. The resulting 2 × 150-bp paired-end reads were sequenced on a NextSeq sequencer. We processed raw fastq files through the bioBakery3 workflow by using the ChocoPhlAn database (mpa_v30_CHOCOPhlAn_201901_marker_info. txt.bz2, which is publicly available at http://cmprod1.cibio.unitn.it/biobakery3/metaphlan_databases/) for taxonomic assignment [27]. We used a Newick phylogenetic tree provided by ChocoPhlAn to calculate UniFrac distances. We performed quality control at the read level using KneadData (v0.10.0) and Trimmomatic (v0.39) before taxonomic assignment with MetaPhlAn3 (v3.0.7) [28]. Owing to low prevalence, we removed both viral and eukaryotic genomic data.

Dietary assessment and construction of PDIs

We assessed general dietary intake over the past year using a self-administered semiquantitative 100-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). This FFQ has been validated internally through comparison with 3-day diet records in BLSA [29] and externally in a Puerto Rican Population residing in Massachusetts [30,31]. Adapted from the original Block-National Cancer Institute FFQ, the BLSA FFQ was modified for the United States population by adding minority group recipes, adjusting food item weightings, expanding portion sizes, incorporating food preparation questions, and enhancing question flow [29]. Trained BLSA staff gave instruction to participants regarding the FFQ, which was collected at the same study visit as the fecal sample collection. Subsequently, estimates of energy and nutrient intake (eg, fiber) were derived using University of Minnesota Nutrient Data System for Research program [32,33].

Using FFQ data, we derived hPDI, uPDI, and PDI using a quintile-based scoring system of 18 food groups, consistent with previous studies [9,34]. We report the complete list of food groups and their classifications in Supplemental Table 1. To calculate plant-based diet indices, we first divided each food group into quintiles of intake and assigned each quintile a score (ranging 1–5) according to alignment with the respective plant-based pattern. We summed the 18 quintile scores for each participant to generate a total plant-based diet index ranging from 18 (lowest adherence) to 90 (highest adherence). For the hPDI, we assigned higher quintile scores for greater intakes of healthy plant foods and lower quintile scores for greater intakes of unhealthy plant foods. In the uPDI, this scoring schema was reversed. In the PDI, we assigned higher quintile scores for greater intakes of all plant foods. In all PDIs, we assigned lower quintile scores for greater intakes of animal-based foods.

TMAO measurement

Overnight fasted plasma samples were collected and stored at −80 °C. These samples were used to quantify TMAO using the MxP Quant 500 kit using standard procedures [35]. TMAO was measured as part of a metabolomic project independent of the microbiome study in the BLSA. The subset of participants (n = 425) from the metabolomic study that overlapped with our analytic sample was used for analyses with TMAO as an outcome.

Covariate Assessment

Participants reported their age (continuous), sex (binary), race and ethnicity, educational attainment, smoking status, and physical activity level on a clinic visit questionnaire [25]. Participants self-reported their race and ethnicity based on the following classifications: non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, American Indian or Alaska Native, Chinese, Filipino, Hawaiian, Japanese, other Asian or other Pacific Islander, other non-White, or not classifiable. We collected and reported data on self-identified race and ethnicity to compare our cohort with the general United States population. We also operationalized race as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, or others and assessed effect measure modification by non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black. We classified smoking status as current, former (not a current smoker and smoked >100 cigarettes in a lifetime), or never (not a current smoker and smoked ≤100 cigarettes in a lifetime), and physical activity was self-reported on a questionnaire and classified as sedentary, low, medium, or high activity levels. We treated education as a continuous variable, reported by participants as years received. Height and weight were measured, and we calculated BMI by dividing weight (kg) by the square of height (m2).

Statistical analyses

By definition, hPDI increases with a higher intake of healthy plant-based foods and a lower intake of an unhealthy plant-based foods, whereas the opposite is true for uPDI. PDI increases with the consumption of both healthy and unhealthy plant-based foods and, thus, does not distinguish between these 2 categories. In previous epidemiologic studies, hPDI and uPDI had opposing associations with cardiometabolic disease outcomes—hPDI was associated with lower risk of obesity, cardiometabolic diseases, kidney disease, and certain types of cancer, and uPDI was associated with a higher risk of these outcomes [[8], [9], [10],12]. PDI was inversely associated with coronary artery disease, but the association was weaker than hPDI [9]. In this study, we were primarily interested in differentiating between diet qualities of PDIs, so we focused on comparing associations of hPDI and uPDI with microbiome features.

We used the R package tableone [36] to present demographics characteristics, overall and by quartile of PDIs, as median (IQR) for continuous variables, and n (%) for binary and categorical variables. We determined the omnibus P value for differences across quartiles of PDIs using Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test for the nonnormal continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables (with continuity correction), and we considered a P value of <0.05 as statistically significant.

Diversity analyses

We rarefied our data for microbiome diversity analyses to minimize the influence of library size. We rarefied the data set by randomly subsampling to a depth of 140,000 reads per individual, performed 10 times without replacement, and then averaging the result to get the final rarefied data set. Rarefying removed 1 bacterial species (Porphyromonas_sp_HMSC065F10).

To quantify measures of microbial α-diversity (ie, within-sample microbial diversity), we used the R packages microbiome [37] and phyloseq [38]. We used the R package microbiome to calculate Pielou evenness index, which describes the evenness or how uniformly different species are distributed in the gut microbiome community, and varies from 0, meaning no evenness, to 1, representing a completely uniform distribution [39]. Then, we used the R package phyloseq to calculate observed species, a microbial richness index that represents the total number of unique observed microbial species, and a Shannon diversity index [40], which combines richness and microbial evenness, typically ranging from 1.5 to 3.5 [41].

We evaluated the association between the PDIs (as the independent variable) and the α-diversity metrics (as the dependent variable) using linear regression models. We assessed associations before and after adjustment for covariates. Fully-adjusted models adjusted for age (continuous), sex (male or female), years of education (continuous), physical activity status (sedentary, low, medium, or high), smoking status (current, ever, and never), BMI (continuous), and total energy intake (continuous). For models examining the α-diversity measure observed species, we additionally adjusted for unrarefied sequencing depth. We did not adjust our multivariable models by race/ethnicity because we recognized that this can be considered a social construct rather than a biological attribute [42].

In all α-diversity models, we evaluated effect measure modification by age (<median, ≥median), sex, and race (non-Hispanic White compared with non-Hispanic Black) by including an interaction term between diet index and each potential effect measure modifier. We also investigated potential nonlinear associations of α-diversity measures with PDIs using restricted cubic spline models from the R package rms [43]. We adjusted interaction models and restricted cubic spline models for the same covariates included in the linear regression models.

We assessed microbial β-diversity, a measure of between-person biodiversity, using the Bray–Curtis distance [44] from the phyloseq package and both unweighted and weighted UniFrac from the rbiom package [[45], [46], [47]]. We constructed principal coordinate analysis plots to visualize the β-diversity (across quartiles of each diet index) and performed a permutational multivariate analysis of variance to evaluate associations of diet indices with β-diversity metrics using the adonis2 function in the vegan package [48] with 9999 permutations.

Compositional analyses

We used the unrarefied microbiome data for compositional analyses. We removed taxa that were present in <10% of participants and had a mean abundance of <0.1% across participants, being the default threshold for the analysis of compositions of microbiomes with bias correction (ANCOM-BC) [49]. This process reduced the total number of bacterial species from 625 to 93.

We analyzed species differential abundance using 2 statistical approaches to help enhance the comprehensiveness and robustness of the results. First, we performed differential abundance testing using ANCOM-BC, which is a compositional differential abundance testing approach for microbiome absolute abundances [49]. It uses a log-linear regression that includes an offset term to adjust for biases resulting from unequal sampling fractions and identifies taxa associated with variables of interest. Using ANCOM-BC, we estimated the log-fold change in species per 1-SD increment in dietary indices and per 1-SD increment in the 18 food group components comprising the dietary indices. We applied an FDR correction [Benjamini and Hochberg (BH) correction) of q <0.05 to identify species that had a significant association with the PDIs in ANCOM-BC models.

To complement ANCOM-BC findings, we used the logistic compositional analysis (LOCOM) [50]. LOCOM is a compositional differential abundance testing methodology based on robust logistic regression models, allowing for the analysis of microbiome data without the use of pseudocounts. Using LOCOM, we estimated the log odds ratio of a read belonging to the taxon of interest rather than falling into a null taxon per 1-SD increment in dietary indices and per 1-SD increment in the 18 food group components comprising the dietary indices. In LOCOM models, we used a BH-corrected FDR of q <0.20.

We used the R package ggplot2 [51] to visualize the associations using a heatmap and relative species abundance in scatter strip plots. We used the R package ggtree [52] to create the visualization of the phylogenetic tree for taxa included in the heatmap.

TMAO analyses

We examined the association of log-transformed TMAO concentrations with dietary indices and individual food groups using linear regression models. We applied an FDR correction (BH correction) of q <0.05 to identify diet indices and food groups that had a significant association with log-transformed TMAO. We examined nonlinear associations using restricted cubic spline models from the R package rms [43].

Results

We present participant characteristics by quartiles of scores for hPDI and uPDI in Table 1. Compared with those in lower quartiles of the hPDI, participants in higher quartiles of the hPDI were more likely to be females, have lower BMI and energy intake, and more likely to identify as White. By contrast, participants in higher quartiles of uPDI comprised a higher percentage of never smokers and a considerably lower percentage of individuals with medium to high activity status. Participants in higher quartiles of PDI (Supplemental Table 2) are more likely to be older and have higher energy intake, differing from those in hPDI and uPDI quartiles. hPDI was inversely associated with uPDI (ρ = −0.16) and positively with PDI (ρ = 0.19); uPDI was inversely associated with PDI (ρ = −0.29). We also presented median (range), expressed in grams, for each food group from the lowest to the highest quintiles in Supplemental Table 3.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of plant-based diet indexes for adults in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging

| Demographics | Diet score (range) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (33–83) (n = 705) | hPDI |

uPDI |

|||||||

| Q1 (35–50) (n = 214) | Q2 (51–54) (n = 156) | Q3 (55–59) (n = 176) | Q4 (60–83) (n = 159) | Q1 (33–49) (n = 203) | Q2 (50–55) (n = 184) | Q3 (56–59) (n = 157) | Q4 (60–79) (n = 161) | ||

| Age (y) | 73.0 (64.0–81.0) | 72.0 (60.3–80.0) | 74.0 (65.8–81.0) | 73.0 (65.0–81.0) | 73.0 (67.0–82.0) | 73.0 (66.0–80.5) | 72.5 (62.0–81.0) | 74.0 (65.0–81.0) | 75.0 (64.0–81.0) |

| Female | 392 (55.6) | 102 (47.7) | 77 (49.4) | 100 (56.8) | 113 (71.1) | 116 (57.1) | 99 (53.8) | 96 (61.1) | 81 (50.3) |

| Race | |||||||||

| White1 | 476 (67.5) | 149 (69.6) | 112 (71.8) | 125 (71.0) | 90 (56.6) | 142 (70.0) | 125 (67.9) | 102 (65.0) | 107 (66.5) |

| Black1 | 176 (25.0) | 54 (25.2) | 35 (22.4) | 42 (23.9) | 45 (28.3) | 40 (19.7) | 46 (25.0) | 45 (28.7) | 45 (28.0) |

| Other | 53 (7.5) | 11 (5.1) | 9 (5.8) | 9 (5.1) | 24 (15.1) | 21 (10.3) | 13 (7.1) | 10 (6.4) | 9 (5.6) |

| Education (y) | 18.0 (16.0–20.0) | 18.0 (16.0–19.0) | 18.0 (16.0–20.0) | 18.0 (16.0–20.0) | 18.0 (16.0–20.0) | 18.0 (16.0–20.0) | 18.0 (16.0–20.0) | 18.0 (16.0–19.0) | 18.0 (16.0–20.0) |

| Physical activity | |||||||||

| Sedentary | 63 (8.9) | 20 (9.3) | 15 (9.6) | 15 (8.5) | 13 (8.2) | 9 (4.4) | 23 (12.5) | 15 (9.6) | 16 (9.9) |

| Low | 274 (38.9) | 97 (45.3) | 59 (37.8) | 58 (33.0) | 60 (37.7) | 75 (36.9) | 59 (32.1) | 67 (42.7) | 73 (45.3) |

| Medium | 208 (29.5) | 51 (23.8) | 41 (26.3) | 65 (36.9) | 51 (32.1) | 70 (34.5) | 61 (33.2) | 41 (26.1) | 36 (22.4) |

| High | 160 (22.7) | 46 (21.5) | 41 (26.3) | 38 (21.6) | 35 (22.0) | 49 (24.1) | 41 (22.3) | 34 (21.7) | 36 (22.4) |

| Smoking status2 | |||||||||

| Ever | 255 (36.2) | 80 (37.4) | 54 (34.6) | 65 (36.9) | 56 (35.2) | 94 (46.3) | 63 (34.2) | 51 (32.5) | 47 (29.2) |

| Never | 450 (63.8) | 134 (62.6) | 102 (65.4) | 111 (63.1) | 103 (64.8) | 109 (53.7) | 121 (65.8) | 106 (67.5) | 114 (70.8) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.4 (23.9–30.3) | 27.7 (25.0–31.8) | 26.6 (23.5–30.2) | 26.1 (23.8–29.5) | 25.5 (23.5–28.2) | 26.5 (23.9–30.8) | 26.2 (23.9–29.9) | 26.5 (23.9–30.3) | 26.4 (24.2–30.4) |

| Energy intake (kcal/d) | 1772.4 (1325.9–2325.8) | 2206.3 (1718.5–2777.2) | 1727.4 (1392.1–2190.7) | 1741.7 (1230.2–2160.9) | 1426.4 (1087.4–1827.9) | 2230.5 (1852.7–2719.9) | 1900.5 (1487.2–2389.5) | 1564.7 (1184.4–1926.6) | 1336.9 (1006.8–1789.9) |

Data are presented as median (IQR) for continuous variables or n (%) for categorical variables.

Abbreviations: hPDI, healthful plant-based diet index; Q, quartile; uPDI, unhealthful plant-based diet index; PDI, overall plant-based diet index.

Non-Hispanic.

Ever smoker: current and former, the latter is not a current smoker and smoked >100 cigarettes in a lifetime; never smoker: not a current smoker and smoked ≤ 100 cigarettes in a lifetime.

Associations of PDIs and food groups with microbiome diversity metrics

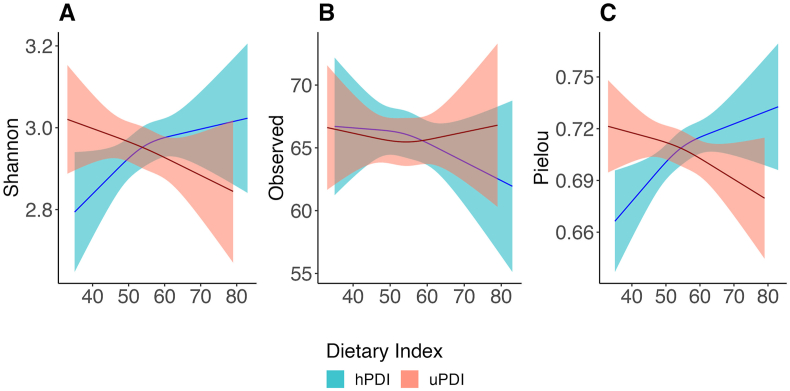

We found no evidence (all interaction P values ≥ 0.07) that associations of PDIs with microbiome α-diversity differed by age (continuous or dichotomized by median age), sex (male compared with female), or race (non-Hispanic White compared with non-Hispanic Black) (Supplemental Table 4). We report unadjusted and adjusted linear regression associations of hPDI and uPDI with α-diversity metrics in Supplemental Tables 5 and 6. For restricted cubic spline analysis with multivariable adjustment associations, a higher hPDI score was associated with higher gut microbiome α-diversity according to metrics that consider microbial evenness (ie, Shannon index and Pielou index) (Figure 1A,C), but hPDI was not associated with α-diversity richness (ie, observed species) (Figure 1B). By contrast, a higher uPDI score was associated with lower α-diversity according to metrics (ie, Pielou index) that consider microbial evenness and richness (Figure 1C). Restricted cubic spline regression plots of these associations did not indicate significant nonlinearity (Figure 1). PDI was associated with lower observed species (Supplemental Figure 2) but was not significant (Supplemental Table 7).

FIGURE 1.

Multivariable-adjusted associations of the healthy plant-based diet index and unhealthy plant-based diet index with gut microbiome α-diversity indices in adult participants from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA). Restricted cubic spline (RCS) plots showing associations of plant-based diet indices with gut microbiome α-diversity indices in adult participants (n = 705; age range: 26–96 years) from the BLSA. (A) RCS plot of dietary indices compared with Shannon index. (B) RCS plot of dietary indices compared with observed species. (C) RCS plot of dietary indices compared with Pielou index. Bold line indicates α-diversity metric mean and shaded area 95% CIs about the mean at given diet index value. Models were adjusted for age, sex, education years, physical activity status, smoking status, body mass index, and total energy intake. Models included a spline term with 3 knots for dietary indices. hPDI, healthful plant-based diet index; uPDI, unhealthful plant-based diet index.

We next report associations of PDIs with measures of gut microbiome β-diversity. After adjusting for covariates, hPDI (quartiles) was significantly associated with all measures of gut microbiome β-diversity, explaining 0.66% of the variance in weighted UniFrac, 0.48% in unweighted UniFrac, and 0.38% in Bray–Curtis distance (Supplemental Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 8); both uPDI and PDI were significantly associated only with unweighted UniFrac, uPDI explaining 0.32% and PDI explaining 0.38% of the variance in unweighted UniFrac (Supplemental Figures 4 and 5; Supplemental Table 8).

Associations of PDIs and food groups with bacterial species

We estimated the log-fold change in species abundance per 1-SD increment in PDIs using ANCOM-BC and LOCOM approaches (Supplemental Table 9 shows the number of significantly differentially abundant species). We visualize ANCOM-BC results for log-fold change in hPDI and uPDI in Figure 2 and display the corresponding coefficient and adjusted P value in Supplemental Table 10. After adjusting for covariates, of the 93 gut microbiome species tested, ANCOM-BC identified 19 species as being significantly associated with hPDI (Figure 2A) and 11 species as being significantly associated with uPDI (Figure 2B). By contrast, the LOCOM statistical approach identified 9 species significantly associated with hPDI, but none significantly associated with uPDI (Supplemental Table 10). A total of 5 species identified by ANCOM-BC using a q <0.05 were also identified by LOCOM using a q< 0.20; LOCOM identified 4 species as significant at q <0.10. None of the species significantly associated with uPDI according to ANCOM-BC (q <0.05) were identified by LOCOM (q <0.20). Namely, greater adherence to hDPI was associated with higher relative abundance of E. eligens and lower relative abundance of Blautia hydrogenotrophica, Dorea sp CAG 317, Eisenbergiella massiliensis, and Sellimonas intestinalis (Supplemental Table 10).

FIGURE 2.

Differential abundance of bacterial species in the gut microbiome of adults in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging by continuous plant-based diet indices. Significant species were detected by analysis of compositions of microbiomes with bias correction (ANCOM-BC). (A) Differential abundance species across hPDI. (B) Differential abundance species across uPDI. ∗Species were also detected by logistic regression model for testing differential abundance of microbial species according to logistic compositional analysis (LOCOM). Associations shown reflect the difference in log abundance of bacterial species per 1-SD increment in plant-based diet indices. Significance was determined using a Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate–corrected q < 0.05 for ANCOM-BC and q < 0.2 for LOCOM. Models were adjusted for age, sex, education years, physical activity status, smoking status, body mass index, and total energy intake. hPDI, healthful plant-based diet index; LFC, XXX; uPDI, unhealthful plant-based diet index.

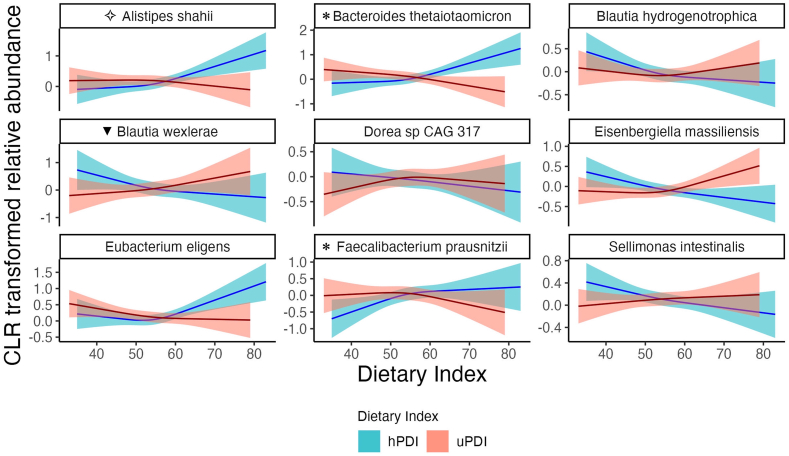

Then, we modeled, using restricted cubic splines, the species that were associated with either ANCOM-BC or LOCOM (Figure 3 and Supplemental Figures 6–8). In Figure 3, we reported the 5 taxa detected by both statistical techniques. In addition, we showed differential abundance for 4 species that were detected by one of the statistical techniques, associated with dietary indices in a linear fashion in the restricted cubic spline plots, and for which secondary differential abundance testing detected a nonsignificant difference in the same direction (Supplemental Table 10). In particular, 4 species (Alistipes shahii, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, E. eligens, and F. prausnitzii) were associated with hPDI in a positive, linear fashion, whereas the remaining 5 species were inversely associated with hPDI. Blautia wexlerae was positively associated with uPDI (Figure 3 and Supplemental Figure 8). Additional analyses of the association between PDI scores and microbiome species were presented in Supplemental Table 10 and Supplemental Figures 9 and 10. The association of PDI with bacterial species were generally closer to hPDI than uPDI, but showed fewer differentially abundant species.

FIGURE 3.

Restricted cubic spline plots showing associations of hPDI and uPDI with gut microbiome bacterial species in adults from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Restricted cubic spline regression modeled the centered log-ratio (CLR)–transformed relative abundance of species in relation to hPDI or uPDI (restricted cubic spline with 3 knots), after adjusting for age, sex, education years, physical activity status, smoking status, body mass index, and total energy intake. Species shown were either differential abundance species associated with hPDI or uPDI in both ANCOM-BC and LOCOM, or abundance changed significantly in one of the statistical tests and association showed a linear fashion in the restricted cubic spline plot. ∗Bacterial species positively associated with hPDI in ANCOM-BC; ✧Species positively associated with hPDI in LOCOM; ▼Differentially abundant species positively associated with uPDI in ANCOM-BC; the secondary differential abundance testing detected a nonsignificant difference in the same direction for these 4 species. The other 5 differentially abundant species shown were detected by both ANCOM-BC and LOCOM: Eubacterium eligens was positively associated with hPDI and the other 4 species were negatively associated with hPDI. Significance was determined using a Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate–corrected q <0.05 for ANCOM-BC and q <0.2 for LOCOM. ANCOM-BC, analysis of compositions of microbiomes with bias correction; hPDI, healthful plant-based diet index; LOCOM, logistic compositional analysis; uPDI, unhealthful plant-based diet index.

Figure 4A presents the presence and relative abundance of differentially abundant species detected by either ANCOM-BC or LOCOM with dietary indices and Figure 4B of these species in relationship to the food groups that made up dietary indices. We found fruits, vegetables, legumes, and vegetable oil correlated with similar bacterial species as hPDI, whereas sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages correlated with similar bacterial species as uPDI, suggesting that these foods may drive, at least in part, the observed difference in associations of bacterial species with hPDI and uPDI (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Phylogenetic tree, relative abundance, and heat map of gut microbiome species and log-transformed TMAO that significantly associated with dietary indices and food groups in adults from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. (A) Phylogenic tree of differential abundant species associated with dietary indices in either ANCOM-BC or LOCOM, and relative abundance of these species in the analytical population. (B) Heat map of these species associated with plant-based indices or food groups. Associations estimated by ANCOM-BC shown reflect the difference in log abundance of bacterial species per 1-SD increment measurement. Log-linear regression estimates change of log-transformed TMAO per 1-SD increment measurement. Significance was determined using a Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate–corrected q <0.05 for ANCOM-BC and q < 0.2 for LOCOM. Models were adjusted for age, sex, education years, physical activity status, smoking status, body mass index, and total energy intake. hPDI, healthful plant-based diet index; Meat (ie poultry and red meat); PDI, overall plant-based diet index; SSBs, sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages; TMAO, trimethylamine N-oxide; uPDI, unhealthy plant-based diet index.

Associations of PDIs and food groups with TMAO

Spearman correlations among dietary indices, food groups, and TMAO are shown in Supplemental Figure 11. Intake of fish or seafood had an inverse correlation with hPDI (Spearman ρ = −0.28) and uPDI (ρ = −0.39), and no correlation with PDI (ρ = −0.01). Intake of whole grains had a positive correlation with PDI (ρ = 0.26), no correlation with hPDI (ρ = 0.06), and a negative correlation with uPDI (ρ = −0.26). Fish or seafood intake had a positive correlation with TMAO (ρ = 0.12), which was the strongest correlation observed among all food groups (Supplemental Figure 11). We also report multivariable-adjusted associations of hPDI, uPDI, and PDI with TMAO in Supplemental Table 11 and Figure 4B, and present restricted cubic spline plots in Supplemental Figure 12. hPDI was inversely associated with TMAO, whereas uPDI and PDI were not.

Discussion

In our racially diverse cohort of adult males and females from the Washington DC–Baltimore metropolitan area, we found that greater adherence to hPDI was associated with higher gut microbiome evenness (a measure of microbiome α diversity), whereas greater adherence to uPDI was associated with lower microbiome evenness. hPDI was also positively associated with several bacterial species known for their ability to degrade plant polysaccharides, whereas uPDI was inversely associated with these species. Moreover, hPDI was significantly associated with lower circulating TMAO, whereas uPDI was not. Associations of PDI with microbiome outcomes were attenuated compared with hPDI and uPDI. Overall, we conclude that healthful and unhealthful plant-based diets are distinctly associated with gut microbiome features, which may explain their differential associations with health outcomes.

Previous research has presented mixed findings regarding associations between adherence to plant-based diets and microbiome features. The Hispanic Community Health Study reported no significant associations between hPDI with gut microbiome α-diversity; however, they only examined Shannon index for diversity and did not rarefy their data [53]. Investigators from the PREDICT1 cohort examined correlations between many factors and microbiome features, reporting nonsignificant correlations of hPDI and uPDI with gut microbiome α-diversity, but their analysis on microbiome diversity did not adjust for covariates and only reported on observed richness and Shannon index rather than evenness [17]. In our study, hPDI was positively associated Pielou evenness index and Shannon index (ie, an index derived from both richness and evenness), but not significantly associated with observed species (ie, richness). By contrast, uPDI was associated with a lower Pielou index. These findings indicate that greater adherence to an hPDI creates a more balanced microbiome (ie, reducing the relative abundance of highly abundant species and increasing the prevalence of rarer species) but does not necessarily increase the number of unique species. A more evenly distributed microbiome community may be more functionally resilient and beneficial to health [54]. For example, a meta-analysis reported that higher microbial evenness was associated with a lower risk of obesity [55]. Moreover, the effect size in our study was as large as differences observed for obese compared with normal weight individuals from this meta-analysis. In our study, the percentage change between the highest and lowest hPDI quartile was 3.0% for Pielou evenness and 2.9% for Shannon index, whereas the difference between individuals with obesity compared with normal weight was 0.9% for Shannon evenness and 2.1% for Shannon Index in the microbiome-obesity meta-analysis [55]. Our findings on plant-based diet quality and microbiome α-diversity also extend findings to other studies of diet quality, including studies that have found greater adherence to a vegetarian diet or a Mediterranean diet is positively associated with gut microbiome α-diversity including evenness [56,57] and greater adherence to a typical Western diet, characterized by high intakes of animal foods, sugar-sweetened beverages, and saturated fat is inversely associated with microbiome diversity measures that include evenness [57,58].

Several of the bacterial species associated with hPDI in our study have also been identified by previous epidemiologic studies. Consistent with our study, cross-sectional studies in distinct cultures have found that hPDI is positively associated with relative abundance of E. eligens [16,17,53]. In addition, in the MLVS study, the relative abundance of F. prausnitzii was positively associated with hPDI [16] and negatively associated uPDI [16]. Furthermore, F. prausnitzii was positively associated with a greater intake of healthy plant-based foods in the PREDICT1 study [17]. B. thetaiotaomicron, which was positively associated with hPDI in our study, is also adept at breaking down otherwise indigestible polysaccharides that are found in healthful plant-based diets [59].

Our finding that adherence to hPDI is associated with higher relative of these species is biologically plausible and may partly explain the health benefits of healthful plant-based diets. E. eligens is a pectin-degrader [19], and a healthful plant-based diet is rich in pectin. An in vitro cell-based assay study showed E. eligens upregulated the production of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, which indicated E. eligens might be a potential anti-inflammatory promoter [19]. F. prausnitzii can produce butyrate through fermentation of dietary plant polysaccharides [17] and has been identified as a bacterial species that can reduce inflammation in patients with Crohn disease [18]. B. thetaiotaomicron has also been associated with positive health outcomes [59].

Finally, our finding that hPDI is inversely associated with TMAO, a microbiome-dependent metabolite elevated in patients with cardiometabolic diseases and cancer [20], is consistent with the notion that hPDI is associated with lower risk of these outcomes [[8], [9], [10], [11], [12]]. In contrast to our findings, the MLVS study [16] reported a positive association between hPDI and TMAO but negative association between uPDI and TMAO. This discrepancy may stem from differences in dietary intake and microbiome composition between populations. Although TMAO is found in fish and TMAO precursors are found in animal products (eg, choline and carnitine present in eggs and red meat) [20], plant-based products are also an important source of some TMAO precursors (ie, betaine is found in beets, spinach, and whole grains, such as quinoa, wheat, oat bran, brown rice, barley) [21]. Compared with our study, the MLVS showed similar correlations of TMAO with fish (positive) and red meat (null), but distinct associations with other food groups (eg, positive association between egg intake and TMAO) [22]. Differences in findings may also stem from influences on TMAO beyond diet and microbiome, such as kidney function and genetic background (eg, flavin-containing mono-oxygenase 3 genotype) [20].

Strengths and limitations

The study has several limitations worth noting. First, our study relied on self-report of diet through FFQ, which could result in inaccurate measurement of diet. However, we would expect that any recall bias would be nondifferential with respect to the gut microbiome, and thus, bias associations toward the null. In addition, the FFQ used in our study did not distinguish between whole and processed or ultraprocessed foods or distinguish between different types of meat, limiting our ability to address their influence on associations of PDIs with gut microbiome features. We also cannot rule out the possible influence of other potential confounding factors. In addition, because this is a cross-sectional analysis, we cannot establish whether differences in adherence to PDIs were a determinant or consequence of differences in gut microbiome features.

Our study also has several strengths. We used a large and racially-diverse cohort with equitable representation of both males and females, which may increase generalizability of our results. We collected dietary data with a validated FFQ including culturally appropriate food items. Furthermore, using fecal microbiome whole-genome shotgun metagenomic sequencing, we were able to achieve higher resolution than traditional 16S rRNA sequencing, which typically only has genera-level resolution. Therefore, we were able to present associations at the species level, which is important for translation of results to clinical interventions.

Conclusion

Greater adherence to a hPDI was associated with higher gut microbiome evenness, higher abundance of beneficial polysaccharide-degrading bacterial species, and lower TMAO concentration. By contrast, greater adherence to uPDI was inversely associated with microbiome evenness and abundance of beneficial polysaccharide-degrading bacterial species, and was not associated with TMAO. Future studies are needed to determine whether the observed associations explain differential health outcomes related to healthful compared with unhealthful plant-based diets.

Author contributions

The authors responsibilities were as follows – NTM, XS: developed the research question and developed the analytic plan; LF, TT, CWC: were involved in the design and implementation of the BLSA cohort and the collection of the biospecimens for microbiome data analysis; NTM, TT, APS: facilitated generation of the microbiome data; SAT: conducted dietary assessment; HK: oversaw the implementation of the creation of plant-based dietary indices; XS: performed statistical analysis, interpreted results, and drafted the manuscript; NTM, CT: oversaw implementation of the analytic plan, interpreted data, and edited the manuscript; XS, NTM, CT: edited and helped to write the paper; NTM has the primary responsibility for final content; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

APS has received payment for serving as a consultant for Merck, has received honoraria from Springer Nature Switzerland AG for guest editing special issues of Current Sleep Medicine Reports, and is a paid consultant to Sequoia Neurovitality. NTM is on the scientific advisory board for Tiny Health; however, this organization provided no funding for this research nor had any impact on the results or interpretation of the data. All other authors report no conflict of interest.

Funding

NTM is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (K01HL141589, R01HL166473) and the National Instutute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK, R21DK132310). HK is supported by a grant from the NHLBI (K01 HL168232). CT is supported by a grant from the NHLBI (K12 HL143957). This project was supported by the National Institutes of Aging (NIA) intramural program and by NIA grants (R01AG050507, R01AG051752).

Data availability

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available on request pending permission from the National Institutes of Aging. Some restrictions may apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajcnut.2024.01.006.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Gibbs J., Cappuccio F.P. Plant-based dietary patterns for human and planetary health. Nutrients. 2022;14(8):1614. doi: 10.3390/nu14081614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim H., Caulfield L.E., Garcia-Larsen V., Steffen L.M., Coresh J., Rebholz C.M. Plant-based diets are associated with a lower risk of incident cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular disease mortality, and all-cause mortality in a general population of middle-aged adults. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019;8(16) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loeb S., Fu B.C., Bauer S.R., Pernar C.H., Chan J.M., Van Blarigan E.L., et al. Association of plant-based diet index with prostate cancer risk. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022;115(3):662–670. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqab365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Key T.J., Appleby P.N., Crowe F.L., Bradbury K.E., Schmidt J.A., Travis R.C. Cancer in British vegetarians: updated analyses of 4998 incident cancers in a cohort of 32,491 meat eaters, 8612 fish eaters, 18,298 vegetarians, and 2246 vegans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014;100(1):378s–385s. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.071266. Suppl 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Springmann M., Wiebe K., Mason-D'Croz D., Sulser T.B., Rayner M., Scarborough P. Health and nutritional aspects of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: a global modelling analysis with country-level detail. Lancet Planet Health. 2018;2(10):e451–e461. doi: 10.1016/s2542-5196(18)30206-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pimentel D., Pimentel M. Sustainability of meat-based and plant-based diets and the environment. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003;78(3 Suppl):660S–663S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.3.660S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craig W.J., Mangels A.R., Fresan U., Marsh K., Miles F.L., Saunders A.V., et al. The safe and effective use of plant-based diets with guidelines for health professionals. Nutrients. 2021;13(11):4144. doi: 10.3390/nu13114144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung S., Park S. Positive association of unhealthy plant-based diets with the incidence of abdominal obesity in Korea: a comparison of baseline, most recent, and cumulative average diets. Epidemiol. Health. 2022;44 doi: 10.4178/epih.e2022063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satija A., Bhupathiraju S.N., Spiegelman D., Chiuve S.E., Manson J.E., Willett W., et al. Healthful and unhealthful plant-based diets and the risk of coronary heart disease in U.S. adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017;70(4):411–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim H., Caulfield L.E., Garcia-Larsen V., Steffen L.M., Grams M.E., Coresh J., et al. Plant-based diets and incident CKD and kidney function. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019;14(5):682–691. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12391018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang F., Baden M.Y., Guasch-Ferré M., Wittenbecher C., Li J., Li Y., et al. Plasma metabolite profiles related to plant-based diets and the risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2022;65(7):1119–1132. doi: 10.1007/s00125-022-05692-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang F., Ugai T., Haruki K., Wan Y., Akimoto N., Arima K., et al. Healthy and unhealthy plant-based diets in relation to the incidence of colorectal cancer overall and by molecular subtypes. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022;12(8) doi: 10.1002/ctm2.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merino J., Joshi A.D., Nguyen L.H., Leeming E.R., Mazidi M., Drew D.A., et al. Diet quality and risk and severity of COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Gut. 2021;70(11):2096–2104. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomova A., Bukovsky I., Rembert E., Yonas W., Alwarith J., Barnard N.D., et al. The effects of vegetarian and vegan diets on gut microbiota. Front. Nutr. 2019;6:47. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2019.00047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muralidharan J., Galie S., Hernandez-Alonso P., Bullo M., Salas-Salvado J. Plant-based fat, dietary patterns rich in vegetable fat and gut microbiota modulation. Front. Nutr. 2019;6:157. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2019.00157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y., Wang D.D., Satija A., Ivey K.L., Li J., Wilkinson J.E., et al. Plant-based diet index and metabolic risk in men: exploring the role of the gut microbiome. J. Nutr. 2021;151(9):2780–2789. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxab175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asnicar F., Berry S.E., Valdes A.M., Nguyen L.H., Piccinno G., Drew D.A., et al. Microbiome connections with host metabolism and habitual diet from 1,098 deeply phenotyped individuals. Nat. Med. 2021;27(2):321–332. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01183-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sokol H., Pigneur B., Watterlot L., Lakhdari O., Bermúdez-Humarán L.G., Gratadoux J.J., et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105(43):16731–16736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804812105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung W.S.F., Meijerink M., Zeuner B., Holck J., Louis P., Meyer A.S., et al. Prebiotic potential of pectin and pectic oligosaccharides to promote anti-inflammatory commensal bacteria in the human colon. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017;93(11) doi: 10.1093/femsec/fix127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho C.E., Caudill M.A. Trimethylamine-N-oxide: friend, foe, or simply caught in the cross-fire? Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2017;28(2):121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dobrijević D., Pastor K., Nastić N., Özogul F., Krulj J., Kokić B., et al. Betaine as a functional ingredient: metabolism, health-promoting attributes, food sources, applications and analysis methods. Molecules. 2023;28(12):4824. doi: 10.3390/molecules28124824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamaya R., Ivey K.L., Lee D.H., Wang M., Li J., Franke A., et al. Association of diet with circulating trimethylamine-N-oxide concentration. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020;112(6):1448–1455. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shock N., Greulich R., Costa P., Andres R., Lakatta E., Arenberg D., et al. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging, Gerontology Research Center; 1984. Normal human aging: the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuo P.L., Schrack J.A., Shardell M.D., Levine M., Moore A.Z., An Y., et al. A roadmap to build a phenotypic metric of ageing: insights from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J. Intern. Med. 2020;287(4):373–394. doi: 10.1111/joim.13024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tilves C., Tanaka T., Differding M.K., Spira A.P., Chia C.W., Ferrucci L., et al. The gut microbiome and regional fat distribution: findings from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2023;31(5):1425–1435. doi: 10.1002/oby.23717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson A.J., Vangay P., Al-Ghalith G.A., Hillmann B.M., Ward T.L., Shields-Cutler R.R., et al. Daily sampling reveals personalized diet-microbiome associations in humans. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;25(6):789–802.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beghini F., McIver L.J., Blanco-Miguez A., Dubois L., Asnicar F., Maharjan S., et al. Integrating taxonomic, functional, and strain-level profiling of diverse microbial communities with bioBakery 3. Elife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.65088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Talegawkar S.A., Tanaka T., Maras J.E., Ferrucci L., Tucker K.L. Validation of nutrient intake estimates derived using a semi-quantitative FFQ against 3 day diet records in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 2015;19(10):994–1002. doi: 10.1007/s12603-015-0518-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tucker K.L., Bianchi L.A., Maras J., Bermudez O.I. Adaptation of a food frequency questionnaire to assess diets of Puerto Rican and non-Hispanic adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1998;148(5):507–518. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bermudez O.I., Ribaya-Mercado J.D., Talegawkar S.A., Tucker K.L. Hispanic and non-Hispanic white elders from Massachusetts have different patterns of carotenoid intake and plasma concentrations. J. Nutr. 2005;135(6):1496–1502. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.6.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schakel S.F., Sievert Y.A., Buzzard I.M. Sources of data for developing and maintaining a nutrient database. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1988;88(10):1268–1271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Talegawkar S.A., Jin Y., Simonsick E.M., Tucker K.L., Ferrucci L., Tanaka T. The Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet is associated with physical function and grip strength in older men and women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022;115(3):625–632. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqab310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Satija A., Bhupathiraju S.N., Rimm E.B., Spiegelman D., Chiuve S.E., Borgi L., et al. Plant-based dietary patterns and incidence of type 2 diabetes in US men and women: results from three prospective cohort studies. PLoS Med. 2016;13(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamaguchi Y., Zampino M., Moaddel R., Chen T.K., Tian Q., Ferrucci L., et al. Plasma metabolites associated with chronic kidney disease and renal function in adults from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Metabolomics. 2021;17(1):9. doi: 10.1007/s11306-020-01762-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshida K., Bartel A. 2022. tableone: Create 'Table 1' to Describe Baseline Characteristics with or without Propensity Score Weights, R package. version 0132. [Google Scholar]

- 37.L. Lahti, S. Shetty, Microbiome, R package, 2012–2019.

- 38.McMurdie P.J., Holmes S. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One. 2013;8(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gauthier J., Derome N. Evenness-richness scatter plots: a visual and insightful representation of shannon entropy measurements for ecological community analysis. mSphere. 2021;6(2):e01019–e01020. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.01019-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shannon C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948;29(3):379–423. doi: 10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ortiz-Burgos S. In: Encyclopedia of Estuaries. Kennish M.J., editor. Springer; Dordrecht, Netherlands: 2016. Shannon-Weaver diversity index; pp. 572–573. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duggan C.P., Kurpad A., Stanford F.C., Sunguya B., Wells J.C. Race, ethnicity, and racism in the nutrition literature: an update for 2020. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020;112(6):1409–1414. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frank E., Harrel J. 2021. rms: Regression Modeling Strategies, R package. version 62-0. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sørensen T. A method of establishing groups of equal amplitude in plant sociology based on similarity of species content, and its application to analysis of the vegetation on Danish commons. Biol. Skr. 1948;5:1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith D. 2023. rbiom: Read/Write, Transform, and Summarize 'BIOM' Data, R package, version 1039084. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lozupone C., Knight R. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71(12):8228–8235. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8228-8235.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lozupone C.A., Hamady M., Kelley S.T., Knight R. Quantitative and qualitative beta diversity measures lead to different insights into factors that structure microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73(5):1576–1585. doi: 10.1128/aem.01996-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oksanen J., Simpson G., Blanchet F., Kindt R., Legendre P., Minchin P., et al. 2022. vegan: Community Ecology Package, R package. version 26-4. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin H., Peddada S.D. Analysis of compositions of microbiomes with bias correction. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):3514. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17041-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu Y., Satten G.A., Hu Y.J. LOCOM: a logistic regression model for testing differential abundance in compositional microbiome data with false discovery rate control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2022;119(30) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2122788119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wickham H. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2016. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu G., Smith D., Zhu H., Guan Y., Lam T.T.-K. GGTREE: an R package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods Ecol Evol. 2017;8:28–36. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peters B.A., Xing J., Chen G.C., Usyk M., Wang Z., McClain A.C., et al. Healthy dietary patterns are associated with the gut microbiome in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023;117(3):540–552. doi: 10.1016/j.ajcnut.2022.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wittebolle L., Marzorati M., Clement L., Balloi A., Daffonchio D., Heylen K., et al. Initial community evenness favours functionality under selective stress. Nature. 2009;458(7238):623–626. doi: 10.1038/nature07840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sze M.A., Schloss P.D. Looking for a signal in the noise: revisiting obesity and the microbiome. mBio. 2016;7(4) doi: 10.1128/mBio.01018-16. 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maskarinec G., Hullar M.A.J., Monroe K.R., Shepherd J.A., Hunt J., Randolph T.W., et al. Fecal microbial diversity and structure are associated with diet quality in the multiethnic cohort adiposity phenotype study. J. Nutr. 2019;149(9):1575–1584. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxz065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu D., Nguyen S.M., Yang Y., Xu W., Cai H., et al. Long-term diet quality is associated with gut microbiome diversity and composition among urban Chinese adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021;113(3):684–694. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhernakova A., Kurilshikov A., Bonder M.J., Tigchelaar E.F., Schirmer M., Vatanen T., et al. Population-based metagenomics analysis reveals markers for gut microbiome composition and diversity. Science. 2016;352(6285):565–569. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Porter N.T., Luis A.S., Martens E.C. Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26(11):966–967. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available on request pending permission from the National Institutes of Aging. Some restrictions may apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study.