Abstract

Females of the extremophile crustacean, Artemia franciscana, either release motile nauplii via the ovoviviparous pathway or encysted embryos (cysts) via the oviparous pathway. Cysts contain an abundant amount of the ATP-independent small heat shock protein that contributes to stress tolerance and embryo development, however, little is known of the role of ATP-dependent molecular chaperone, heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) in the two processes. In this study, a hsp90 was cloned from A. franciscana. Characteristic domains of ArHsp90 were simulated from the deduced amino acid sequence, and 3D structures of ArHsp90 and Hsp90s of organisms from different groups were aligned. RNA interference was then employed to characterize ArHsp90 in A. franciscana nauplii and cysts. The partial knockdown of ArHsp90 slowed the development of nauplius-destined, but not cyst-destined embryos. ArHsp90 knockdown also reduced the survival and stress tolerance of nauplii newly released from A. franciscana females. Although the reduction of ArHsp90 had no effect on the development of diapause-destined embryos, the resulting cysts displayed reduced tolerance to desiccation and low temperature, two stresses normally encountered by A. franciscana in its natural environment. The results reveal that Hsp90 contributes to the development, growth, and stress tolerance of A. franciscana, an organism of practical importance as a feed source in aquaculture.

Keywords: Hsp90, Stress tolerance, Development, Molecular chaperone, Artemia franciscana

Introduction

Artemia franciscana, an extremophile crustacean, exhibits a complex life history due to the harsh environment of its natural habitat. Their embryos undergo alternative pathways of development, termed ovoviviparous, leading to the release of swimming nauplii and oviparous, the gastrulae enclosed in a chitinous shell (cysts).1, 2 Upon release from females, cysts enter diapause, a state of dormancy characterized by metabolic depression, arrested development, and enhanced stress tolerance. Diapause in A. franciscana occurs in anticipation of adverse environmental conditions. Diapause is divided into stages, including initiation, maintenance, and termination.3, 4 Diapause termination in A. franciscana occurs until encountering discrete termination cues such as desiccation and/or cold or by artificial stimuli such as solvents and certain chemicals.5 In favorable conditions, A. franciscana embryo development resumes after diapause, but if conditions are not conducive to growth, activated cysts enter a state termed quiescence and remain dormant until introduction to an environment suitable for development.

To cope with stressors such as temperature extremes, desiccation, and anoxia during diapause, A. franciscana cysts possess adaptations including but not limited to a rigid cyst cell wall,2, 6, 7 high trehalose concentration,8 late embryogenesis abundant proteins,9, 10, 11 and abundant ATP-independent diapause specific molecular chaperones.1, 12, 13, 14 Three different diapause-specific small heat shock proteins, p26, ArHsp21, and ArHsp22, and a ferritin homolog, artemin are synthesized only in embryos that enter diapause and have a role in stress tolerance and development.1, 12, 13, 14 But there is little information on the occurrence and activities of the ATP-dependent molecular chaperones such as heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) during A. franciscana stress tolerance and diapause.

Hsp90, a highly conserved ATP-dependent molecular chaperone of the HSP family, is a flexible dimer. Each Hsp90 monomer consists of an amino-terminal ATP-binding domain, a middle domain (MD), and a carboxyl-terminal dimerization domain.15, 16 Utilizing energy generated by ATP binding and hydrolysis, Hsp90 contributes to protein folding, regulating signaling proteins, and interacts with hormone receptors and regulatory kinases.17, 18, 19 What’s more, Hsp90 is one of the most abundant cytosolic proteins in eukaryotes, accounting for 1–2% of soluble protein in the absence of stress,20, 21 indicating a key role in cell function.

A number of studies have demonstrated that Hsp90 plays different roles during insect development and diapause.22, 23, 24, 25 For instance, hsp90 is upregulated during larvae diapause of the wheat blossom midge, Sitodiplosis mosellana, indicating the roles of the gene in diapause maintenance.26 However, hsp90 is downregulated during pupal diapause in the flesh fly, Sarcophaga crassipalpis and the corn earworm, Helicoverpa zea,27, 26 suggesting a different function of Hsp90 in these insects. In certain cases, Hsp90 may not be affected by diapause. Hsp90 transcript is not changed when entering diapause in the blow fly Lucilia sericata, but the amount of Hsp90 mRNA is upregulated upon diapause termination, meaning that the gene may be associated with post-diapause development.28 In crustaceans, Hsp90 regulates the developmental process as well. For example, Hsp90 influences the signal transduction of estrogen which mediates vitellogenin synthesis in the shrimp Metapenaeus ensis.29 And in the water flea Daphnia magna, Hsp90 has a role in juvenile development.30 But still, the function of Hsp90 in the development and diapause of crustaceans is poorly understood.

Therefore, in the present research, cDNA encoding a structurally typical Hsp90 was cloned from A. franciscana and named ArHsp90 (Table 1). Multiple sequence alignment and analysis of 3D configuration analysis of ArHsp90 and Hsp90 from other species confirm the conservatism of the protein. dsRNA generated with ArHsp90 as a template was used for the knockdown of ArHsp90 by RNA interference (RNAi) in nauplii and cysts. Knocking down of ArHsp90 reduced the survivability of nauplii and lowered the cold and desiccation tolerance of cysts and the thermal tolerance of nauplii. Furthermore, reduced ArHsp90 leads to the release of not fully developed cysts and shortened body length of nauplii, indicating a role of ArHsp90 in A. franciscana embryo development.

Table 1.

Primers used for cloning HSP90 cDNA by 5′- and 3′-RACE.

| Primer name | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partial Hsp90 | GAYGACGARCAG TACRTSTGGGAG |

TGCTTCTTGGCRG CCATGTADCCCAT |

62 |

| 5′-RACE outer | GCTGATGGCGAT GAATGAACACTGa |

AATGGGCTTGGTC TTGTTGAG |

54 |

| 5′-RACE inner | CGCGGATCCGAA CACTGCGTTTGC TGGCTTTGATGa |

GCTCATCATCATT GTGTTTGGAAG |

60 |

| 3′-RACE outer | TGAAACTTGGCA TCCACGAG |

GCGAGCACAGAA TTAATACGACTa |

53 |

| 3′-RACE inner | GAATTCAGGAGA ACCAAAAGCACA TC |

CGCGGATCCGAA TTAATACGACTC ACTCACTATAGGa |

60 |

| Hsp90 qPCR | GTCAGTTTGGTGT GGGTTTC |

CCTTGGGTTTGTC CTCTTC |

57 |

| Tubulin qPCR | CTGCATGCTGTAC AGAGGAGATGT |

CTCCTTCAAGAGA GTCCATGCCAA |

55 |

| GFP dsRNA |

TAATACGACTCAC TATAGGGAGACAC ATGAAGCAGCACG ACCT |

TAATACGACTCAC TATAGGGAGAAGT TCACCTTGATGCCC TTC |

72 |

| Hsp90 dsRNA |

TAATACGACTAAC TATAGGGACCATT CGACCAGACAGTGG |

TAATACGACTAAC TATAGGGGCGAGG TGATCTTCCCAGTC |

72 |

Abbreviations used: HSP90, heat shock protein 90; RACE, rapid amplification of cDNA ends.

T7 promotor is bolded.

Commercial primer.

Results

Characterization of A. franciscana ArHsp90 nucleotide and amino acid sequences

The full-length ArHsp90 cDNA (Accession Number MK007072) of 2249 nucleotides obtained from hydrated cysts of A. franciscana contained a 5′-untranslated region of 74 nucleotides and a 3′-untranslated region of 78 nucleotides with a short poly(A) tail (Figure 1). The ArHsp90 open reading frame (ORF) encoded a polypeptide of 698 amino acid residues with a predicted molecular mass of 80.42 kDa and a theoretical isoelectric point of 4.8.

Fig. 1.

cDNA and deduced amino acid sequence of ArHsp90. ATP binding domain, blue underline; Middle domain, orange underline; Carboxyl terminal domain, red underline. The characteristic “GVG” motifs of ArHsp90 ATP binding domain are boxed with green line. The peptide 390-CLELFEEIAEDKENYKKFYE-409 was used as antigen to make an antibody to ArHsp90 (boxed with purple line). The carboxyl-terminal “MEEVD” motifs are boxed with yellow line. Five characteristic sequences in the ATP binding domain and middle domain are boxed with black line.

ArHsp90 contains an amino-terminal ATP binding domain (ABD) characterized by two GVG motif (Figure 1). Following the ABD was a MD that in Hsp90 from other species binds clients and regulates ATP hydrolysis, and a carboxyl-terminal domain that mediates dimerization. The deduced amino acid sequence of the cloned ArHsp90 contains the well-conserved Hsp90 family peptide signatures: 27-NKEILRELISSNSSDALDKIR-47, 94-LGTIAKSGT-102, 88-IGQFGVGFYSAYLVAD-133, 331-IKLYVRRVFI-340, and 357-GVVDSEDLPLNISRE-371. The pentapeptide MEEVD at the end of the C-terminus is identified and well-conserved (Figures 1 and 2(a)). A second ArHsp90 cDNA with an identical ORF was cloned from a different preparation of cyst RNA, thereby verifying the absence of PCR and sequencing artifacts (not shown).

Fig. 2.

Structures and 3D configurations of Hsp90s. (a) Schematic representation of the domain organization of Hsp90s. (b) The 3D models of Hsp90s simulated. ABD domain of each Hsp90 is yellow-colored. Abbreviations used: ABD, ATP binding domain; MD, middle doamin; CTD, carboxyl terminal domain; Af_Hsp90, A. franciscana Hsp90;Dm_Hsp90, Drosophila melanogaster Hsp90; Hsp90, heat shock protein 90; Hs_Hsp90, Homo sapiens Hsp90; Ov_Hsp90, Octopus vulgaris Hsp90; Sc_Hsp90, Saccharomyces cerevisiae Hsp90; Td_Hsp90, Triticum dicoccoides Hsp90.

Phylogenetic and 3D structure analysis of Hsp90s

Phylogenetic analysis shows that ArHsp90 is an arthropod Hsp90, and it is the most primitive one that is closely related to the Hsp90 of Octopus (Figure 3). Hsp90s from six species (one crustacean, one insect, one vertebrate, one mollusk, one plant, and one yeast) were employed to simulate 3D structures and all of them are similar in 3D construction (Figure 2(b)). As a conserved and characteristic domain of Hsp90, ABDs of Hsp90 from the six species were analyzed. All the ABDs analyzed contain three conserved motifs “GTKAFMEALQAGADISMIGQFGVGFYSAYLVADKVVVTSKHNDDEQYVWE,” “ETFAFQAEIAQLMSLIINTFYSNKEIFLRELISNSSDALDKIRYESLTDP,” and “GKELYIKJIPBKEDKTLTIIDTGIGMTKADLVNNLGTIAKS.” (Figure 4(a), Supplementary Figure S2). 3D alignment of ABDs showed that they were of great similarity in spatial conformation, with similar numbers of helixes and strands as well as a root-mean-square deviations (RMSD) ranging from 0.263 to 0.618 by pair-to-pair comparison (Figure 4). In coincidence with their phylogenetic relationship, ArHsp90 has the smallest RMSD with Hsp90 from Octopus (0.263).

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic relationship of Hsp90s. The maximum likelihood (ml) method with 200 bootstrap replicates was employed to construct phylogenetic tree. Bootstrap value higher than 50 was marked. Different colors are used to mark different Hsp90 groups. Yeast and plant Hsp90s (orange). Animal Hsp90s (Yellow). Arthropod Hsp90s (Blue). Vertebrate Hsp90s (Purple). Insect Hsp90s (Green). Hsp90 of A. franciscana (Af_Hsp90) is red-colored.

Fig. 4.

The 3D model analysis of ABDs of Hsp90s. (a) 3D model of ABDs of the chosen Hsp90s. (b) 3D alignment of the ABDs. (c) Number of helixes and strands in ABDs. (d) RMSD matrix of ABDs. Abbreviations used: ABD, ATP binding domain; Af_Hsp90, A franciscana Hsp90; Dm_Hsp90, Drosophila melanogaster Hsp90; Hsp90, heat shock protein 90; Hs_Hsp90, Homo sapiens Hsp90; Ov_Hsp90, Octopus vulgaris Hsp90; RMSD, root-mean-square deviations; Sc_Hsp90, Saccharomyces cerevisiae Hsp90; Td_Hsp90, Triticum dicoccoides Hsp90.

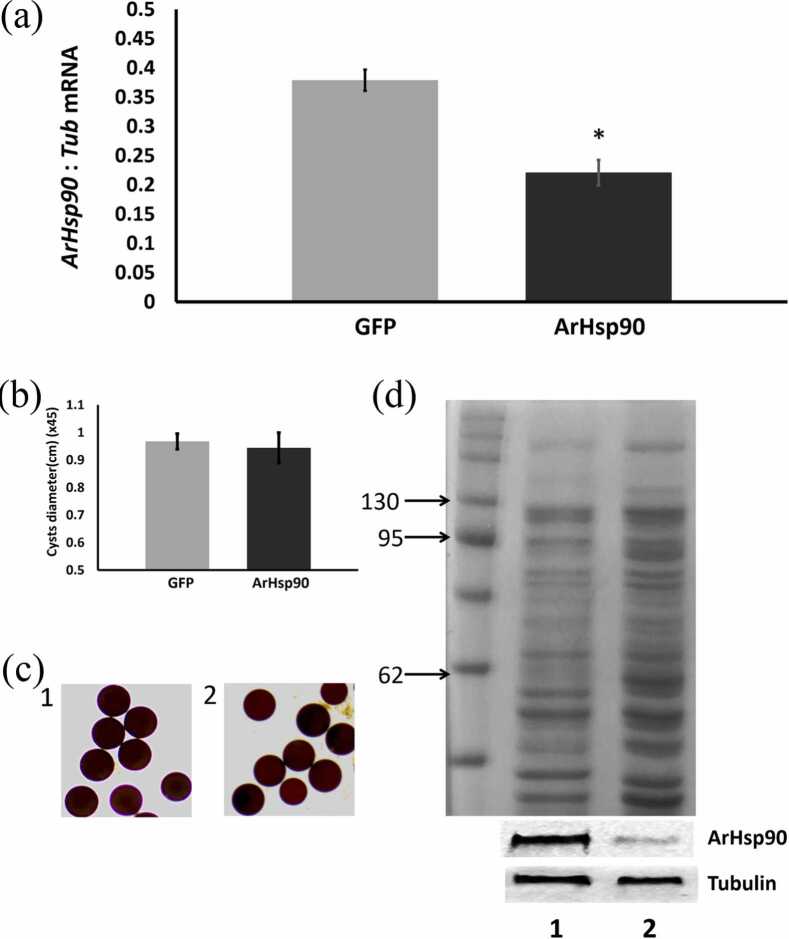

Injection of A. franciscana females with ArHsp90 dsRNA knocked down ArHsp90 mRNA and protein in cysts but did not change the diameter of cysts

As revealed by qRT-PCR with tyrosinated α-tubulin as the internal standard, the injection of ArHsp90 dsRNA into females reduced ArHsp90 mRNA in cysts by 41.7% in comparison to the amount of ArHsp90 mRNA in cysts released from females injected with green fluorescent protein (GFP) dsRNA (Figure 5(a)). Equal amounts of protein extracts prepared from cysts released from females, after injection with ArHsp90 dsRNA or GFP dsRNA, were applied to each well of SDS polyacrylamide gels as determined by Bradford assay and verified by Coomassie staining of gels. Immunoprobing of western blots for tyrosinated α-tubulin which did not change during knockdown also indicated that equal amounts of protein were loaded in all lanes of the SDS polyacrylamide gels (Figure 5(d)). Cysts from females injected with ArHsp90 dsRNA exhibited a reduced amount of ArHsp90 when compared to cysts from females injected with GFP dsRNA (Figure 5(d)).

Fig. 5.

RNAi knockdown ArHsp90 mRNA and protein in A. franciscana cysts. (a) The amount of ArHsp90 mRNA in A. franciscana cysts released from females receiving GFP and ArHsp90 dsRNA was determined by qPCR using tyrosinated α-tubulin as internal standard. The experiment was done three times and error bars show standard deviation. The asterisk indicates that the amount of ArHsp90 mRNA in cysts from females receiving ArHsp90 dsRNA was statistically different (P < 0.05) from the amount of ArHsp90 mRNA in cysts from females receiving GFP dsRNA. (b) The average diameters (magnified 45 times) of cysts from females injected with GFP or ArHsp90 dsRNA. (c) Light micrographs showing cysts from females injected with GFP (1) or ArHsp90 (2) dsRNA. (d) Protein extracts from 50 cysts released from females injected with either GFP dsRNA (1) or ArHsp90 dsRNA (2) were resolved in SDS polyacrylamide gels and either stained with Coomassie blue (upper) or transferred to nitrocellose and stained with antibody to ArHsp90 or Tubulin. The experiment was repeated two times and a representative example is shown. Abbreviations used: GFP, green fluorescent protein; RNAi, RNA interference.

Cysts from both groups exhibited normal color and shape (Figure 5(c)), but those with reduced ArHsp90 exhibited normal outlook and the average diameter is 0.944 cm (×45), a little smaller compared to the ones with the normal amount of ArHsp90 (0.967 cm (×45)). But the difference is not significant (P > 0.05) (Figure 5(b)).

ArHsp90 protects A. franciscana cysts against stress

Following 4 weeks of desiccation and freezing at −80 °C for 2 months, treatments were required to terminate diapause and also served as stressors, cysts were incubated in seawater at room temperature for hatching, an indicator of viability after stress. Only 5.5% of cysts with reduced ArHsp90 survived whereas 20% of cysts containing ArHsp90 survived as indicated by hatching (Figure 6(a)).

Fig. 6.

Knockdown of ArHsp90 reduced the A. franciscana cysts stress tolerance. (a) Cysts released from females injected with dsRNA for GFP and ArHsp90 were incubated in seawater for 1 week, desiccated for 4 weeks and frozen for 2 months and then incubated in seawater at room temperature to determine stress tolerance by evaluate hatching. The experiment was repeated three times and error bars show standard deviation. The asterisk indicates that the hatching number of cysts from females receiving ArHsp90 dsRNA was statistically different from the hatching number of cysts from females receiving GFP dsRNA. (b) Metabolism test of newly released cysts receiving either ArHsp90 dsRNA or GFP dsRNA. The absorbance at 553 nm of cysts from both group and empty control were presented. Bars marked with same letter means there was no significant difference. Abbreviation used: GFP, green fluorescent protein.

Metabolic activities of cysts released from females injected with GFP or ArHsp90 dsRNA were similar as confirmed by similar color changes in phenol red seawater, which was due to acidification of the solution via the production of CO2, after incubation for 1 day (Figure 6(b)).

Knockdown of ArHsp90 slows the development of nauplius-destined but not encysted A. franciscana embryos

Protein extracts from nauplii released from females injected with ArHsp90 dsRNA exhibited a reduced amount of ArHsp90 mRNA and protein when compared to nauplii from females injected with GFP dsRNA (Figure 7(a) and (b)).

Fig. 7.

RNAi knockdown ArHsp90 mRNA and protein in A. franciscana caused the release of not fully developed embryos and shortened nauplii. (a) The amount of ArHsp90 mRNA in A. franciscana nauplii released from females receiving GFP and hsf1 dsRNA was determined by qPCR using tyrosinated α-tubulin as internal standard. The experiment was done three times and error bars show standard deviation. The asterisk indicates that the amount of ArHsp90 mRNA in cysts from females receiving ArHsp90 dsRNA was statistically different (P < 0.05) from the amount of ArHsp90 mRNA in cysts from females receiving GFP dsRNA. (b) Protein extracts from 60 nauplii released from females injected with either GFP dsRNA (1) or ArHsp90 dsRNA (2) were resolved in SDS polyacrylamide gels and either stained with Coomassie blue (upper) or transferred to nitrocellose and stained with antibody to ArHsp90 or Tubulin. The experiment was repeated two times and a representative example is shown. (c) Light micrographs showing nauplii from females injected with GFP dsRNA (1) or ArHsp90 dsRNA, and not fully developed embryos (3). (d) The average diameters (magnified 45 times) of cysts from females injected with GFP or ArHsp90 dsRNA. Abbreviations used: ES, eye spot; GFP, green fluorescent protein; RNAi, RNA interference.

For the first broods of cysts from females injected with either GFP or ArHsp90 dsRNA, the time from fertilization to release was approximately 5 days (Table 2). Meanwhile, the time from fertilization to release of first broods of nauplii was approximately 5 days from females injected with GFP dsRNA. In contrast, the release time for nauplii from females injected with ArHsp90 dsRNA was 6.5 days, which is significantly longer than nauplii released from females injected with GFP dsRNA (Table 2).

Table 2.

The average time to release for cysts and nauplii from A. franciscana females with normal and reduced ArHsp90.

| +Hsp90 | −Hsp90 | (Δ Days) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyst | 5.4 | 5.5 | 0.2 | >0.05 |

| Nauplii | 5.5 | 6.5 | 1.0 | <0.001 |

Abbreviation used: Hsp90, heat shock protein 90.

The swimming nauplii released from females receiving either GFP or ArHsp90 dsRNA were similar to one another in activity and shape (Figure 8(c)), but the latter tended to be somewhat shorter than the former (Figure 8(d)). Occasionally, females destined to produce nauplii that were injected with dsRNA for Hsp90 released broods of green, irregularly shaped bodies (Figure 8(c)).

Fig. 8.

ArHsp90 knockdown nauplii exhibited reduced survivability and increased heat sensitivity. (a) Surviving (motile) nauplii released from females injected with either GFP or ArHsp90 dsRNA were counted daily and compared to the number of viable nauplii upon release from females. The experiment was repeated three times and error bars show standard deviation. (b) Nauplii released from females injected with either GFP or ArHsp90 dsRNA were heat shocked at 39 °C for 1 h and then allowed to recover at room temperature for 24 h. Surviving (motile) nauplii were counted at the times indicated and compared to the number of viable nauplii before heat shock to give % survival. The experiment was repeated three times and error bars show standard deviation. Abbreviation used: GFP, green fluorescent protein.

ArHsp90 knockdown reduces nauplii viability and thermal tolerance

Approximately 96% of nauplii from females injected with GFP dsRNA survived 5 days after release. In contrast, nauplii from females injected with ArHsp90 dsRNA began to die 2 days after release, and 78% of nauplii survived on day 5 (Figure 8(a)). Upon exposure to 39 °C for 1 h and then incubation at 25 °C for recovery, 87% of nauplii from females injected with GFP dsRNA survived while only 67% of nauplii from females injected with ArHsp90 dsRNA survived (Figure 8(b)).

Discussion

Hsps play important roles in diapause and stress responses.23, 25 A. franciscana enhances stress tolerance by entering diapause and facing adverse conditions such as temperature extremes.33, 31, 32 Thus understanding the role of Hsps in A. franciscana diapause is of great importance. In spite of the abundance and importance of Hsp90 in cells, the function of Hsp90 during crustacean development has received limited attention and therefore, the whole sequence of A. franciscana hsp90 is cloned and how Hsp90 regulates A. franciscana embryo development and stress tolerance is investigated in the present study.

ArHsp90, the Hsp90 family member acquired, is characterized by classical Hsp90 domains, ABD, MD, and carboxyl-terminal domain (Fig. 2, Fig. 4). The possession of the five characteristic sequences of Hsp90 indicating that ArHsp90, like other Hsp90s, is an ATP-dependent protein35, 34 (Schopf et al., 2017). ArHsp90 shares high sequence similarity with Hsp90s of other species (Supplementary Figure S1). The conserved domains and high sequence similarity indicate that ArHsp90 is a characteristic member of the Hsp90 family. The conserved MEEVD motif, which is essential in the interaction with co-chaperones and therefore a signature of cytosolic Hsp90,36, 37 is identified in all six Hsp90s analyzed. Together, the arthropod Hsp90s form a group in contrast to the vertebrate group, as well as the plant and fungi group. ArHsp90 is the closest one related to Octopus Hsp90 compared to Hsp90s of other arthropods as revealed by phylogenetic analysis and RMSD of ABD 3D model alignment. The result is in correspondence to the evolutionary position of A. franciscana, a primitive crustacean.38 And the low pair-to-pair RMSD values between representative Hsp90s selected indicate a high conservatism of the protein among species in a different kingdom. The conservatism across species indicates a critical role of Hsp90 in organisms. Hsp90 was confirmed to have a role in development and against environmental stress in several insect and vertebrate species.12, 19, 26 Therefore, a similar role of Hsp90 in A. franciscana is expected.

ArHsp90 clearly play an important role in the survival of diapausing cysts because knockdown of ArHsp90 reduced cyst hatching, an indication of stress tolerance. The protective role of Hsp90 in A. franciscana diapause is consistent with the findings in S. mosellana diapause, where hsp90 is more prominent for cold tolerance.26 Since ATP is limiting during diapause in A. franciscana and protein refolding by Hsp90 is ATP-dependent,39, 40 Hsp90 would be unable to function effectively as a molecular chaperone, possibly resulting in increased amounts of nonfunctional proteins and disruption of cell activities. The degradation of such proteins and their recovery from aggregates would also be reduced. It has been proposed that ATP-requiring molecular chaperones such as Hsp90 sequester substrate proteins in the absence of ATP as a protective method during diapause23 and this activity would be diminished in Hsp90 knockdown cysts leading to reduced survival during diapause. Alternatively, Hsp90 has been shown in other organisms such as Omphisa fuscidentalis to increase in abundance as diapause terminates41 and the inhibition of this process in knockdown cysts, should it occur, may adversely affect their ability to terminate diapause and resume development.

In other examples, Hsp90 is downregulated during pupal diapause of the flesh fly Sarcophaga crassipaipis28 but is unchanged in the fruit fly Drosophila triauraria.42 In the marine copepod Calanus finmarchicus, the amount of Hsp90 does not vary in response to diapause.42 In spite of these findings, the role of Hsp90 in diapausing crustaceans remains uncertain, and the finding herein that Hsp90 confers stress tolerance during crustacean diapause is novel.

Reduction of ArHsp90 reduced the developmental rate of nauplius-destined embryos, in contrast to the situation in cysts. And nauplii with reduced ArHsp90 are significantly shorter and exhibit higher mortality after release than the ones with normal amounts. This slower rate, possibly not fully fulfilled embryo development, and reduced survivability of nauplii containing less Hsp90, may reflect a requirement for Hsp90 as A. franciscana nauplius-destined embryos are actively developing and growing into swimming nauplii. The phenomenon suggests the importance of Hsp90 in the nauplius-destined embryo development and early stage of the post-release development of A. franciscana nauplii. That nauplii did not all die is likely due to residual Hsp90 in these animals. Hsp90 interacts with more than 10% of the proteome and is essential for the growth of eukaryotic cells.43 The reduction of Hsp90 probably disturbed several cellular events related to the development and survival of A. franciscana nauplii. Previous researches listed the pleiotropic roles of cytosolic Hsp90s in embryogenesis and postembryonic development in insects including fruit fly, red flour beetle, and brown planthopper.45, 46, 44 The finding in A. franciscana is consistent with these researches and further extends the role of Hsp90 in the embryo and postembryonic development to primitive arthropods.

A few nauplius-destined embryos with reduced Hsp90 developed into irregularly shaped greenish bodies that eventually disintegrated without hatching (Figure 6(c)). The molecular basis for the development of the irregularly shaped bodies is uncertain but may reflect the disruption of cell cycle events or alterations in cell signaling pathways. Both of these possibilities are feasible based on the known roles of Hsp90 in binding signaling molecules and transcription factors.42, 47, 48, 49 It is also possible that by reducing the amount of Hsp90, there is a decrease in the efficiency of protein folding within cells of nauplius-destined embryos leading to more widespread effects in the cell and thus on the developing embryos as a whole. To be noticed, Hsp90 is linked to the activation of the ecdysone receptor/ultraspiracle complex in Drosophila melanogaster.50 And in vertebrates, hsp90 is associated with the activity of steroid hormone.51 So there is a possibility that the knockdown of Hsp90 disturbed the hormone system in A. franciscana and thus influenced the development of nauplius-destined embryos.

Besides its role in development, ArHsp90 also confers stress tolerance in nauplii, similar to cysts. As stated in previous researches, Hsp90 confers stress resistance in mammalian cells, bacteria, and yeast.48, 52, 53 And in most cases, cytosolic Hsp90 is functional against heat stress in insects.54, 44, 55 In addition to the mentioned findings, the results generated in this study using RNAi indicate that ArHsp90 has an important protective role during stress in A. franciscana nauplii, either by protecting proteins from irreversible denaturation or assisting in their refolding or degradation. The exact amount of ArHsp90 under normal and stress conditions was not evaluated in this study but could be determined in the future in order to more fully characterize the role of ArHsp90 in the stress tolerance of A. franciscana nauplii.

Conclusion

A Hsp90 termed ArHsp90 was cloned from A. franciscana. And bioinformatic and phylogenetic analysis showed that ArHsp90 is a member of the arthropod Hsp90 group. ArHsp90 was shown by RNAi to be required for the normal development of some but not all A. franciscana nauplius-destined embryos. The phenomenon indicates that there is sufficient Hsp90 after knockdown to sustain a number of proteins involved in developmental processes. Additionally, ArHsp90 is required for stress tolerance in nauplii and cysts potentially through ATP-dependent activities such as protein folding/refolding or independently of ATP by binding proteins and preventing their irreversible denaturation. This work sets the stage for further investigation of the role of Hsp90 during growth, development, and diapause of A. franciscana including elucidating Hsp90 function in limiting ATP environments such as those that occur in diapausing cysts. Future work could test the function of isolated Hsp90 in vitro to see if protein binding is affected by ATP.

Materials and methods

Culture of A. franciscana

A. franciscana cysts (INVE Aquaculture, Inc., Ogden, UT, USA) were hydrated in distilled water at 4 °C, washed and then incubated with aeration in autoclaved seawater from Halifax Harbour, Nova Scotia, Canada, at room temperature. Nauplii were harvested and raised in a glass tank with filtered seawater at room temperature under natural sunlight with an air supply and fed daily with Isochrysis galbana (T-iso) (Provasoli-Guillard Center for Culture of Marine Phytoplankton, West Boothbay Harbor, ME, USA). The research described in this paper was performed in accordance with the ethical guidelines provided by the Canadian Council on Animal Care. The University Committee on Laboratory Animals of Dalhousie University approved the research and assigned Protocol Number 117-36.

ArHsp90 cDNA cloning

Exactly 0.1 g of hydrated A. franciscana cysts were homogenized in TRIzol (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON, Canada). RNA was extracted with the RiboPure RNA Purification Kit (Invitrogen) and used as a template for cDNA synthesis with the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (ThermoFisher Scientific, Ottawa, ON, Canada) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Degenerative primers for ArHsp90 were designed by aligning crustacean Hsp90 sequences from the Genbank database (Table 1). A partial cDNA encoding ArHsp90 was amplified in PCR mixtures for 5 min at 95 °C, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 49 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min, and then 6 min at 72 °C. PCR products of the expected size were recovered and purified with a QIAEX II Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Toronto, ON, Canada) after resolved in 1.2% agarose gel. The acquired DNA fragments were ligated into the pCR2.1-TOPO vector (ThermoFisher Scientific) before being used to transform TOP10 F′ competent Escherichia coli (ThermoFisher Scientific). Vectors containing putative ArHsp90 cDNA were harvested and sent out for sequencing at the Center for Applied Genomics DNA Sequencing Facility (TCAG), Toronto Sick Kids Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada.

Rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) method was employed to get full-length ArHsp90. Primers were designed based on the partial sequence of ArHsp90 cDNA (Table 1). mRNA prepared from A. franciscana cysts was ligated with RACE adapter, and cDNA was synthesized with the FirstChoice RLM-RACE Kit (Ambion Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX, USA) and used as a template to amplify the 5′ and 3′ regions of ArHsp90 cDNA. Nested PCR for RACE was performed with outer PCR at 95 °C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 53 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min, then 6 min at 72 °C and inner PCR was at 95 °C for 5 min followed by 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 60.5 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min, and then 6 min at 72 °C. PCR products of the appropriate size were recovered, purified, ligated to vectors, and amplified as described above. Putative ArHsp90 cDNA fragments were sequenced at TCAG, Toronto Sick Kids Hospital.

Sequence analysis

The amino acid sequence of ArHsp90 was deduced based on ArHsp90 cDNA sequence using ORF Finder (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. The molecular weights and isoelectric point values were calculated by the SMS2 server (http://www.detaibio.com/sms2/). Alignment was performed with MEGA 10.0 software (Mega Limited, Auckland, New Zealand) using the amino acid sequence of Hsp90s from a few other organisms (Supplementary Table S1) available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. A phylogenetic tree was constructed with MEGA using the Maximum Likelihood method with 200 bootstrap replications under a Poisson model and presented with Figtree software. Representative Hsp90s of other animal groups were selected to compare with ArHsp90. The chosen Hsp90s include Sc_Hsp90 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae Hsp90, from yeast), Td_Hsp90 (Triticum dicoccoides Hsp90, from plant), Ov_Hsp90 (Octopus vulgaris Hsp90, from mollusk), Dm_Hsp90 (D melanogaster Hsp90, from insect), and Hs_Hsp90 (Homo sapiens Hsp90, from vertebrate). SMART server (SMART: Main page (embl.de)) was employed to predict the conserved domains of Hsp90s.

The 3D structures of ArHsp90 and representative Hsp90s chosen were simulated by homology modeling (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/) and visualized with PyMOL software (version 2.4, Schrödinger, New York, USA). VMD software was used to calculate the RMSD between 3D structures.

dsRNA preparation and injection of A. franciscana females

First-strand cDNA was made with RNA prepared from hydrated A. franciscana cysts using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and the RiboPure RNA Purification Kit (Invitrogen). cDNA was amplified using specific primers (Table 1) at 0.2 mM and Platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen) under the following reaction conditions: 5 min at 94 °C, 30 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 60 °C, and 1 min at 72 °C, with a final 10 min at 72 °C. GFP cDNA in the vector pEGFP-N1 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) was amplified using the above reaction conditions with primers specific to GFP.56 PCR products were employed as templates for the production of ArHsp90 dsRNA and GFP dsRNA with the MEGAscript RNAi Kit (Ambion Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX, USA). The dsRNAs were visualized after agarose gel electrophoresis as described above.

ArHsp90 and GFP dsRNAs were separately diluted to 0.32 µg/μl with 0.5% phenol red in Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS) (Sigma-Aldridge, Oakville, ON, Canada). Unfertilized adult A. franciscana females were immobilized on ice cold 3% agarose and injected under an Olympus SZ61 stereomicroscope (Olympus Canada Inc., Markham, ON, Canada) with the Nanoject II microinjector (Drummond Scientific Co., Broomall, PA, USA) using glass needles prepared with preset program on a P-97 Flaming/Brown Micropipette Puller (Sutter Instrument Co., Novato, CA, USA). The needles were cut at 40° angle with a clean razor blade under the Stereomicroscope. For each injection, 250 μL of solution containing 80 ng of dsRNA for either ArHsp90 or GFP was used.

Quantification of ArHsp90 mRNA by qRT-PCR

RNA was prepared from either 8 cysts or 50 nauplii, harvested within 1 day after release from females injected with dsRNA for either ArHsp90 or GFP, by homogenizing in 100 μL TRIzol (ThermoFisher Scientific). cDNA was produced using 0.1 µg of RNA as a template. All RNA preparations were incubated without reverse transcriptase to ensure the absence of genomic DNA. qRT-PCR, using 1 μL of cDNA as a template, was conducted with the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen, Mississauga, ON, Canada) in a Rotor-Gene RG-3000 (Corbett Research, Sydney, Australia) with primers specific for ArHsp90 and tyrosinated α-tubulin (Table 1) at 10 μmol/L. qRT-PCR was at 50 °C for 3 min and then at 95 °C for 8 min followed by 30 cycles of 95 °C for 20 s, annealing for 20 s at 54 °C, and 72 °C for 40 s. Experiments were performed in duplicate from three individually prepared RNA samples. Copy numbers of ArHsp90 were determined from a standard curve of Ct values and normalized against tyrosinated α-tubulin.56 Primer fidelity was assessed by melting curve analysis.

Detection of ArHsp90 SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoprobing of western blots

Eighty cysts or 50 nauplii collected from females injected with either ArHsp90 or GFP dsRNA were homogenized on ice in 25 μL treatment buffer (62.5 mM Tris, 2% (w/v) SDS, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 5% (v/v) B-mercaptoethanol, 0.05% (w/v) bromophenol blue, pH 6.8), heated in a boiling water bath and collected by centrifuging for 10 min at 10,000× RPM at 4 °C. Exactly 20 μL of each protein sample was resolved in 12.5% SDS polyacrylamide gels and either stained with Coomassie blue or transferred to nitrocellulose membranes in transfer buffer (25 mM Tris, 200 mM glycine in 20% (v/v) methanol). The PiNK Plus Prestained Protein Ladder (FroggaBio Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada) was used as a marker.

To detect antibody-reactive proteins, nitrocellulose membranes were blocked in TBS (10 mM Tris, 140 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) containing 5% low-fat milk at room temperature for 60 min. Membranes washed with TBS were incubated in TBS containing polyclonal antibody raised in rabbits against the Hsp90 peptide 76-CLELFEEIAEDKENYKKFYE-97 (ABBIOTEC, San Diego, CA, USA)57 or specific antibody against α-tubulin for 20 min. The membranes were washed sequentially three times for 5 min each with TBS-T (10 mM Tris, 140 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20, pH 7.4) followed by three times for 5 min each with HST (10 mM Tris, 1 M NaCl, 0.5% Tween-20, pH 7.4) before incubated for 20 min in HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) in TBS. Then the membranes were washed with TBS-T and HST as described above followed by a final wash for 3 min in TBS and immunoreactive proteins were visualized with Western Lightning Enhanced Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA, USA). Three individually prepared protein samples for each test were quantified.

Monitoring embryo development within A. franciscana females and phenotypic changes of cysts and nauplii

The time to release after fertilization was determined for cysts and nauplii either from females injected with ArHsp90 or GFP dsRNA. Briefly, females were mated 48 h after injection. Time to release was defined by the time of fertilization to the time of release of cysts or nauplii from injected females. A. franciscana fertilization was denoted by the fusion of egg sacs.

An Olympus SZ61 stereomicroscope with infinity capture imaging software was employed to determine if cysts released from females injected with ArHsp90 dsRNA were morphologically normal compared to cysts released from females injected with GFP dsRNA. The color and shape of cysts were checked after release firstly. Then the diameters of cysts were measured with a microruler and averaged. The experiment was done 4 times for cysts either from females injected with ArHsp90 or GFP dsRNA with separate preparations of 80 cysts each time. Cysts of brown color and normal round shape were incubated in seawater for 10 consecutive days to determine if they hatched and thus failed to enter diapause after the above examinations.

The body shape and integrity of nauplii were checked before further experiments. The body length of each nauplii was then measured with a microruler. The experiment was done four times for nauplii either from females injected with ArHsp90 or GFP dsRNA with separate preparations of fifty nauplii each time.

Determining stress tolerance of cysts from A. franciscana females injected with dsRNA

Cysts viability upon release was determined as described previously using a semiquantitative phenol red assay for metabolism that measured CO2 production.12 Briefly, 10 normal shaped and colored cysts from females receiving either ArHsp90 or GFP dsRNA were incubated immediately after release in 100 μL of test solution (seawater containing 1000 U penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin sulfate and 0.03% phenol red, pH 8.6) in parafilm sealed Costar 96 well UV plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA). Control wells contained test solution only. The changes in absorbance measured at 553 nm (A553) were performed as described12 for 1 day.

Round-shaped and brown-colored cysts released from A. franciscana females injected with either ArHsp90 or GFP dsRNA were collected separately and incubated in seawater for 10 days at room temperature to allow diapause entry. To terminate diapause and test stress tolerance, collected cysts were dried in a desiccator over Indicating Drierite (Sigma-Aldrich) for 4 weeks prior to freezing at −80 °C for 2 months. The survivability of stressed cysts was determined by hatching in seawater at room temperature. Swimming nauplii were counted and removed daily after hatching. Monitoring of hatching was terminated 5 days after the last appearance of nauplii. The experiment was done in duplicate with 3 separate preparations of 40–50 cysts in each trial for cysts from females receiving either ArHsp90 or GFP dsRNA.

Viability and stress tolerance of nauplii from A. franciscana females injected with dsRNA

Swimming nauplii released from females injected with ArHsp90 or GFP dsRNA were collected within 12 h of release from females and raised in separate Petri dishes containing seawater at room temperature and observed daily to determine the number of immobile nauplii which were considered dead. Dead nauplii were removed as incubation progressed. The observation continued for 5 consecutive days, and the number of surviving nauplii was recorded.

To determine stress tolerance, nauplii released within 12 h from females injected with either ArHsp90 or GFP dsRNA were collected, heat shocked at 39 °C for 1 h,1 and then incubated at 25 °C to allow recovery. The number of surviving individuals was determined after recovering for 24 h. Three independent experiments were done with the number of nauplii ranging from 57 to 134 per experiment.

Statistical analysis

A one-tailed student’s t-test (α = 0.05) via Two-Sample Assuming Equal Variances was used to assess the time to release and the difference of ArHsp90 mRNA in cysts and nauplii released from females injected with GFP dsRNA as compared to the ones injected with ArHsp90 dsRNA. Chi-square independence of factors tests were used to assess differences in the viability and stress tolerance of first brood cysts and nauplii released from females injected with ArHsp90 and GFP dsRNA. Results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation for the above measurements. All data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Analyses were carried out using Microsoft Excel 2016.

Author contribution

Jiabo Tan: Conceptualization, Experiment performed, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Afnan Fatani: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Experiment performed, Data curation, Formal analysis. Xiangyang Wu: Writing – original draft, Experiment performed, Data curation, Formal analysis. Xiaojun Song: Writing – review & editing. Thomas H. MacRae: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declarations of interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Jiabo Tan reports financial support was provided by Dalhousie University. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant (Number RGPIN/04882-2016) to THM and by the “First Class Fishery Discipline” programme [(2020)3] in Shandong Province, China. The work was also supported by doctoral funding from Qingdao Agricultural University (1120034) and by a scholarship from the Chinese Scholarship Council to JT and the King Abdullah Scholarship Program (KASP) supported by the Saudi Government, implemented by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and administered by Saudi Arabian Cultural Bureau (SACB) Canada to AF. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. One of the authors, also the cherished supervisor of the first author and the correspondence author, Dr Thomas H. MacRae has passed away. The authors would like to honor his memory in this acknowledgment.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.cstres.2024.02.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material Supplementary Fig. S1. Alignment of Hsp90 from mouse (M musculus), zebrafish (D rerio), crayfish (P clarkii), white shrimp (L vannamei), blue crab (S paramamosain), brine shrimp (A. franciscana), fruit fly (D melanogaster), and diamondback moth (P xylostella). The black underline marked the five characteristic sequences of Hsp90. “*”, 100% identical. “:”, larger than seventy-five percent identical. “.”, larger than fifty percent identical.

.

Supplementary material Supplementary Fig. S2. Motif identification and alignment of ABDs from the six characteristic Hsp90s. (a) The three conservative motifs identified in the Hsp90s. (b) The alignment of ABDs. Black, a hundred percent identical for the amino acids. Pink, larger than 75% identical. Light blue, larger than 50% identical.

.

Supplementary material Supplementary Fig. S3. Hsp90 in nauplii and cysts of A. franciscana. Protein extracts from cysts and nauplii were resolved in SDS polyacrylamide gels and either stained with Commassie (a) or blotted to nitrocellulose and reacted with antibody to Hsp90 (b). Cell free protein extracts were from nauplii (1) and cysts (2). M, molecular mass markers in kDa.

.

Data availability statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

ArHsp90 paper reference (Reference data) (Mendeley Data)

References

- 1.Liang P., MacRae T.H. The synthesis of a small heat shock/alpha-crystallin protein in Artemia and its relationship to stress tolerance during development. Dev Biol. 1999;207:445–456. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacRae T.H. Molecular chaperones, stress resistance and development in Artemia franciscana. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2003;14:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koštál V. Eco-physiological phases of insect diapause. J Insect Physiol. 2006;52:113–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koštál V., Štětina T., Poupardin R., Korbelová J., Bruce A.W. Conceptual framework of the eco-physiological phases of insect diapause development justified by transcriptomic profiling. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114:8532–8537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707281114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robbins H.M., Van Stappen G., Sorgeloos P., Sung Y.Y., MacRae T.H., Bossier P. Diapause termination and development of encysted Artemia embryos: roles for nitric oxide and hydrogen peroxide. J Exp Biol. 2010;213:1464–1470. doi: 10.1242/jeb.041772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dai L., Chen D.F., Liu Y.L., et al. Extracellular matrix peptides of Artemia cyst shell participate in protecting encysted embryos from extreme environments. PloS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma W.M., Li H.W., Dai Z.M., Yang J.S., Yang F., Yang W.J. Chitin-binding proteins of Artemia diapause cysts participate in formation of the embryonic cuticle layer of cyst shells. Biochem J. 2013;449:285–294. doi: 10.1042/BJ20121259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clegg J.S. The origin of trehalose and its significance during the formation of encysted dormant embryos of Artemia salina. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1965;14:135–143. doi: 10.1016/0010-406x(65)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore D.S., Hansen R., Hand S.C. Liposomes with diverse compositions are protected during desiccation by LEA proteins from Artemia franciscana and trehalose. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1858:104–115. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toxopeus J., Warner A.H., MacRae T.H. Group 1 LEA proteins contribute to the desiccation and freeze tolerance of Artemia franciscana embryos during diapause. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2014;19:939–948. doi: 10.1007/s12192-014-0518-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warner A.H., Miroshnychenko O., Kozarova A., et al. Evidence for multiple group 1 late embryogenesis abundant proteins in encysted embryos of Artemia and their organelles. J Biochem. 2010;148:581–592. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvq091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King A.M., MacRae T.H. The small heat shock protein p26 aids development of encysting Artemia embryos, prevents spontaneous diapause termination and protects against stress. PloS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qiu Z., Macrae T.H. ArHsp21, a developmentally regulated small heat-shock protein synthesized in diapausing embryos of Artemia franciscana. Biochem J. 2008;411:605–611. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qiu Z., MacRae T.H. ArHsp22, a developmentally regulated small heat shock protein produced in diapause-destined Artemia embryos, is stress inducible in adults. FEBS J. 2008;275:3556–3566. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siligardi G., Hu B., Panaretou B., Piper P.W., Pearl L.H., Prodromou C. Co-chaperone regulation of conformational switching in the Hsp90 ATPase cycle. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51989–51998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410562200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terasawa K., Minami M., Minami Y. Constantly updated knowledge of Hsp90. J Biochem. 2005;137:443–447. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Genest O., Wickner S., Doyle S.M. Hsp90 and Hsp70 chaperones: collaborators in protein remodeling. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:2109–2120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.REV118.002806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taipale M., Jarosz D.F., Lindquist S. HSP90 at the hub of protein homeostasis: emerging mechanistic insights. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:515–528. doi: 10.1038/nrm2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wandinger S.K., Richter K., Buchner J. The Hsp90 chaperone machinery. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:18473–18477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai B.T., Chin N.W., Stanek A.E., Keh W., Lanks K.W. Quantitation and intracellular localization of the 85k heat shock protein by using monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:2802–2810. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.12.2802-2810.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zou J., Guo Y., Guettouche T., Smith D.F., Voellmy R. Repression of heat shock transcription factor HSF1 activation by HSP90 (HSP90 complex) that forms a stress-sensitive complex with HSF1. Cell. 1998;94:471–480. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81588-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denlinger D.L. Regulation of diapause. Annu Rev Entomol. 2002;47:93–122. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King A.M., MacRae T.H. Insect heat shock proteins during stress and diapause. Annu Rev Entomol. 2015;60:59–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-162107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kubrak O.I., Kucerova L., Theopold U., Nassel D.R. The sleeping beauty: how reproductive diapause affects hormone signaling, metabolism, immune response and somatic maintenance in Drosophila melanogaster. PloS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacRae T.H. Gene expression, metabolic regulation and stress tolerance during diapause. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:2405–2424. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0311-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng W., Li D., Wang Y., Liu Y., Zhu-Salzman K. Cloning of heat shock protein genes (hsp70, hsc70 and hsp90) and their expression in response to larval diapause and thermal stress in the wheat blossom midge, Sitodiplosis mosellana. J Insect Physiol. 2016;95:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rinehart J.P., Denlinger D.L. Heat-shock protein 90 is down-regulated during pupal diapause in the flesh fly, Sarcophaga crassipalpis, but remains responsive to thermal stress. Insect Mol Biol. 2000;9:641–645. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tachibana S.-I., Numata H., Goto S.G. Gene expression of heat-shock proteins (Hsp23, Hsp70 and Hsp90) during and after larval diapause in the blow fly Lucilia sericata. J Insect Physiol. 2005;51:641–647. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu L.T., Chu K.H. Characterization of heat shock protein 90 in the shrimp Metapenaeus ensis: evidence for its role in the regulation of vitellogenin synthesis. Mol Reprod Dev. 2008;75:952–959. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soetaert A., Moens L.N., Van der Ven K., et al. Molecular impact of propiconazole on Daphnia magna using a reproduction-related cDNA array. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2006;142:66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clegg J.S. Desiccation tolerance in encysted embryos of the animal extremophile, Artemia. Integr Comp Biol. 2005;45:715–724. doi: 10.1093/icb/45.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clegg J.S. Protein stability in Artemia embryos during prolonged anoxia. Biol Bull. 2007;212:74–81. doi: 10.2307/25066582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clegg J.S., Jackson S.A., Popov V.I. Long-term anoxia in encysted embryos of the crustacean, Artemia franciscana: viability, ultrastructure, and stress proteins. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;301:433–446. doi: 10.1007/s004410000249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen B., Zhong D., Monteiro A. Comparative genomics and evolution of the HSP90 family of genes across all kingdoms of organisms. BMC Genom. 2006;7:156. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta R.S. Phylogenetic analysis of the 90 kD heat shock family of protein sequences and an examination of the relationship among animals, plants, and fungi species. Mol Biol Evol. 1995;12:1063–1073. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoter A., El-Sabban M.E., Naim H.Y. The HSP90 family: structure, regulation, function, and implications in health and disease. Inter J Mol Sci. 2018;19:2560. doi: 10.3390/ijms19092560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scheufler C., Brinker A., Bourenkov G., et al. Structure of TPR domain-peptide complexes: critical elements in the assembly of the Hsp70-Hsp90 multichaperone machine. Cell. 2000;101:199–210. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80830-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khodajou-Masouleh H., Shahangian S.S., Attar F., R H.S., Rasti B. Characteristics, dynamics and mechanisms of actions of some major stress-induced biomacromolecules; addressing Artemia as an excellent biological model. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;39:5619–5637. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1796793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jay D., Luo Y., Li W. Extracellular Heat Shock Protein-90 (eHsp90): everything you need to know. Biomolecules. 2022;12:911. doi: 10.3390/biom12070911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zuehlke A.D., Moses M.A., Neckers L. Heat shock protein 90: its inhibition and function. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2018;373 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tungjitwitayakul J., Tatun N., Singtripop T., Sakurai S. Characteristic expression of three heat shock-responsive genes during larval diapause in the bamboo borer Omphisa fuscidentalis. Zool Sci. 2008;25:321–333. doi: 10.2108/zsj.25.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aruda A.M., Baumgartner M.F., Reitzel A.M., Tarrant A.M. Heat shock protein expression during stress and diapause in the marine copepod Calanus finmarchicus. J Insect Physiol. 2011;57:665–675. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao R., Houry W.A. Molecular interaction network of the Hsp90 chaperone system. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;594:27–36. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-39975-1_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen X., Li Z.D., Dai Y.T., Jiang M.X., Zhang C.X. Identification and characterization of three heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) homologs in the brown planthopper. Genes. 2020;11:1074. doi: 10.3390/genes11091074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knorr E., Vilcinskas A. Post-embryonic functions of HSP90 in Tribolium castaneum include the regulation of compound eye development. Dev Genes Evol. 2011;221:357–362. doi: 10.1007/s00427-011-0379-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schnorrer F., Schonbauer C., Langer C.C., et al. Systematic genetic analysis of muscle morphogenesis and function in Drosophila. Nature. 2010;464:287–291. doi: 10.1038/nature08799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhatti M., Dinn S., Miskiewicz E.I., MacPhee D.J. Expression of heat shock factor 1, heat shock protein 90 and associated signaling proteins in pregnant rat myometrium: implications for myometrial proliferation. Reprod Biol. 2019;19:374–385. doi: 10.1016/j.repbio.2019.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schopf F.H., Biebl M.M., Buchner J. The HSP90 chaperone machinery. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:345–360. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zuehlke A., Johnson J.L. Hsp90 and co-chaperones twist the functions of diverse client proteins. Biopolymers. 2010;93:211–217. doi: 10.1002/bip.21292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arbeitman M.N., Hogness D.S. Molecular chaperones activate the Drosophila ecdysone receptor, an RXR heterodimer. Cell. 2000;101:67–77. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80624-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pratt W.B., Toft D.O. Regulation of signaling protein function and trafficking by the hsp90/hsp70-based chaperone machinery. Exp Biol Med. 2003;228:111–133. doi: 10.1177/153537020322800201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Honore F.A., Mejean V., Genest O. Hsp90 is essential under heat stress in the bacterium Shewanella oneidensis. Cell Rep. 2017;19:680–687. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takasaki T., Tomimoto N., Ikehata T., Satoh R., Sugiura R. Distinct spatiotemporal distribution of Hsp90 under high-heat and mild-heat stress conditions in fission yeast. Micro Publ Biol. 2021;2021 doi: 10.17912/micropub.biology.000388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Quel N.G., Pinheiro G.M.S., Rodrigues L.F.C., Barbosa L.R.S., Houry W.A., Ramos C.H.I. Heat shock protein 90 kDa (Hsp90) from Aedes aegypti has an open conformation and is expressed under heat stress. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;156:522–530. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang J., Que S.Q., Liu X., et al. Characteristic and expression of Hsp70 and Hsp90 genes from Tyrophagus putrescentiae and their response to thermal stress. Sci Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91206-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tan J., MacRae T.H. Stress tolerance in diapausing embryos of Artemia franciscana is dependent on heat shock factor 1 (Hsf1) PloS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gbotsyo Y.A., Rowarth N.M., Weir L.K., MacRae T.H. Short-term cold stress and heat shock proteins in the crustacean Artemia franciscana. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2020;5:1083–1097. doi: 10.1007/s12192-020-01147-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Supplementary material Supplementary Fig. S1. Alignment of Hsp90 from mouse (M musculus), zebrafish (D rerio), crayfish (P clarkii), white shrimp (L vannamei), blue crab (S paramamosain), brine shrimp (A. franciscana), fruit fly (D melanogaster), and diamondback moth (P xylostella). The black underline marked the five characteristic sequences of Hsp90. “*”, 100% identical. “:”, larger than seventy-five percent identical. “.”, larger than fifty percent identical.

Supplementary material Supplementary Fig. S2. Motif identification and alignment of ABDs from the six characteristic Hsp90s. (a) The three conservative motifs identified in the Hsp90s. (b) The alignment of ABDs. Black, a hundred percent identical for the amino acids. Pink, larger than 75% identical. Light blue, larger than 50% identical.

Supplementary material Supplementary Fig. S3. Hsp90 in nauplii and cysts of A. franciscana. Protein extracts from cysts and nauplii were resolved in SDS polyacrylamide gels and either stained with Commassie (a) or blotted to nitrocellulose and reacted with antibody to Hsp90 (b). Cell free protein extracts were from nauplii (1) and cysts (2). M, molecular mass markers in kDa.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

ArHsp90 paper reference (Reference data) (Mendeley Data)