Summary

Background

The Bowel Ultrasound Score (BUSS) accurately detects therapy-related changes by using the Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn's disease (SES-CD) as the reference standard. We aimed to evaluate ultrasound remission as a treatment target and its prediction for long-term endoscopic remission.

Methods

This single-centre prospective observational study, based at a tertiary referral centre in Milan, Italy, enrolled, between March 1, 2018, and January 31, 2021, adult patients with active CD (SES-CD >2) who were starting biologics. Colonoscopy and IUS was performed at baseline and at 12 months (mean 12.8 ± 4.2). The primary outcome was the predictive value of ultrasound remission at week 12 (BUSS ≤3.52) for long-term endoscopic remission at 12 months. The International Bowel Ultrasound Segmental Activity Score (IBUS-SAS) was also calculated and optimal cut-point to detect endoscopic remission was identified through ROC analysis.

Findings

93 patients with CD were included. Of these, 22 patients (24%) achieved endoscopic remission. Week 12 ultrasound remission predicted endoscopic remission (59% compared with 41% of the patients who were not in ultrasound remission; OR 9.93, 95% CI 3.10–31.80; p < 0.001), while week 12 calprotectin values (<50, <100, <250 μg/g) did not. Week 12 ultrasound activity was associated with failure to achieve long-term endoscopic remission (NPV 87%, PPV 54%). IBUS-SAS cut-off to discriminate endoscopic remission was 22.8 (AUC 0.906). ROC curve comparison showed no-significant difference between BUSS and IBUS-SAS (p = 0.46) for detecting endoscopic remission.

Interpretation

Early ultrasound remission predicts long-term endoscopic remission, making it a valuable early treatment target for clinical practice and in clinical trials. Larger multicentre validation studies are warranted to confirm these findings.

Funding

None.

Keywords: Crohn's disease, Intestinal ultrasound, Bowel ultrasound score, BUSS, IBUS-SAS, Target

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Dependence solely on symptoms for treatment escalation results in a lower rate of achieving endoscopic remission, as compared with an approach that includes evaluation of both clinical and biochemical activity. However, establishing a single universal fecal calprotectin threshold applicable to all patients for predicting endoscopic remission remains a challenge. Intestinal ultrasound has emerged as a promising tool for monitoring patients, effectively detecting disease activity. We aimed to evaluate ultrasound remission as a treatment target and its prediction for long-term endoscopic remission.

Added value of this study

The findings of this single-centre prospective observational study suggest that ultrasound remission after induction with biologic therapy could consistently predict long-term endoscopic remission. We identified that a Bowel Ultrasound Score (BUSS) greater than 3.52 by week 12 is associated with failure to achieve endoscopic remission (NPV 87%) at 12 months.

Implications of all the available evidence

Intestinal ultrasound offers the potential for a non-invasive, proactive approach involving early and meticulous monitoring of patients. This strategy could encompass timely evaluations of treatment response, with the overarching goal of reducing Crohn's disease (CD) related complications. Larger multicentre validation studies are needed.

Introduction

Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic, relapsing, and destructive inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract which can lead to organ damage and impaired quality of life.1 A “treat-to-target approach” with tight monitoring of intestinal inflammatory lesions is recommended.2 Ileocolonoscopy (IC) is currently the gold standard to assess disease activity and the response to treatments.2 However, it has a limited role in tight monitoring strategies because it cannot be performed repeatedly. Conversely, intestinal ultrasound (IUS) allows frequent assessments and has the advantage of assessing both the large and the small bowel and examining bowel wall layers beyond the mucosa. The ability of IUS in monitoring response to treatment in patients with CD has been demonstrated in large cohorts.3,4 The first interventional multicentre trial evaluating IUS has shown that some ultrasonographic parameters, including bowel wall thickness (BWT) and colour Doppler signals (CDS), change early and quickly in response to treatment.5 However, clear definitions of response and remission to assess the responsiveness by IUS are not yet validated, particularly with IC as the reference standard.6,7

The international Bowel Ultrasound Segmental Activity Score (IBUS-SAS) was developed without the use of IC as a reference standard, so definitive cut-off values for remission and response are lacking.8

We have previously developed and described an IUS-based score of luminal activity in a large cohort of patients with CD that uses IC as the reference standard and have used parameters identified in multivariate analyses as independent predictors for detecting disease activity and severity.9 The Bowel Ultrasound Score (BUSS) detects endoscopic response with high accuracy. The most accurate cutoff values for BUSS were 3.52 (AUROC 0.86) for endoscopic remission (SES-CD ≤2) and decrease of 1.2 points (AUROC 0.79) for endoscopic response (≥50% decrease of SES-CD).10 More recently, BUSS was validated in an external cohort.11

This study aimed to prospectively evaluate early ultrasound remission, as defined by a BUSS ≤3.52, as a relevant treatment target and its prediction for long-term endoscopic remission.

Methods

Study design and population

This was a single-centre, prospective observational study. All consecutive adult patients (18 years of age and older) with an established diagnosis of CD (since at least 6 months) seen in a tertiary referral centre in Milan, Italy, between March 1, 2018, and January 31, 2021, who required investigation by IC due to suspicion of active disease were eligible. Inclusion criteria were endoscopic activity, defined by a SES-CD >2, and need to start a biological therapy. Exclusion criteria were any contraindication to full IC (e.g., intolerance to preparation, severe flare), concomitant participation in clinical trials, disease limited to the rectum, active infections, including Clostridioides difficile and cytomegalovirus infections, penetrating or stricturing complications requiring surgery, and inability to perform IUS within the time intervals established by the study.

Ethics statement

The study was performed according to Good Clinical Practice guidelines and was approved by our Institutional Review Board, IRCCS Ethics Committee of the Humanitas Clinical Institute. All patients gave their informed consent for this study.

This protocol study is registered on Clinical trial registry website (https://praticheweb.humanitas.it) with the number ICH2218.

Procedures

Colonoscopies

The examinations were performed in a blinded fashion by an expert endoscopist with at least 10 years of experience and using a standard video endoscope (Fujinon, Japan) and following the standard protocol used in clinical practice (colonic cleansing by administration of 4 L polyethylene glycol). The endoscopic activity was measured by SES-CD, and endoscopic remission was defined as a SES-CD ≤2.12,13

Intestinal ultrasound

A gastroenterologist who is expert in IUS (20 years of experience) performed all the scanning procedures in a blinded fashion, without having any knowledge about the patient's symptoms and endoscopic findings. Neither preparation nor contrast were used. IUS was performed after 6–8 h fasting, using an Aloka Arietta V60 with convex (5–1 MHz) and microconvex probes (4–8 MHz), according to acquisition protocol previously described.9 The entire abdomen was systematically scanned starting from the right iliac fossa. The following parameters were evaluated: bowel wall thickness (BWT) (normal values up to 3 mm), measured in longitudinal and transverse sections, from the interface between the mucosa and the lumen to the interface between the serosa and the muscle layer. A mean of two measurements for each section was calculated; bowel wall stratification (BWS), defined as (0) normal, multilayered, (1) uncertain, (2) predominantly hypoechogenic (≤3 cm), (3) lost (>3 cm); colour Doppler signals (CDS), defined as absence (0) or presence of blood signals at colour Doppler. In case of presence of blood signals, they were quantified as (1) short signals, (2) long signals inside bowel wall, (3) long signals inside and outside bowel wall; presence of mesenteric lymph nodes; mesenteric hypertrophy [i-fat, defined as absent (0), uncertain (1), present (2)]. The presence of complications was also investigated: stricture, defined as presence of wall thickening with a narrowed lumen with or without dilatation of a proximal loop; fistula, defined as a hypoechoic tract with or without hyperechoic content; abscess, defined as a roundish anechoic lesion with an irregular wall, without vascular signals.

These parameters were evaluated for each intestinal segment impacted by the disease, and the worst segment taken into account.

The BUSS was calculated according to the validated formula (BUSS = 0.75 × BWT + 1.65 × CDS; where CDS = 1 if present, or CDS = 0 if absent). Ultrasound remission was defined as a BUSS score ≤3.52, ultrasound response as a decrease of 1.2 points of BUSS.10 The IBUS−SAS was also calculated (4 × BWT + 15 × i-fat + 7 × CDS + 4 × BWS).8

We considered the most affected segment, with the highest scores, in cases where multiple intestinal segments were affected by the disease.

Follow-up

All patients underwent IC (reference standard) and IUS at week 0, prior to starting biological therapy, and at the final visit, after an average follow-up time of 12.8 months (SD = 4.2). IUS and IC were performed in a maximum interval of 30 days, by two different blind operators, unaware of the patients' clinical and biochemical parameters. Therapies were kept stable in the period between the two procedures. The SES-CD and the BUSS were measured to quantify disease activity. In addition, at week 0, at week 12 and at the final visit, patients underwent complete clinical assessment and blood and stool samples were obtained for C-reactive protein (CRP) and faecal calprotectin (FC) measurements. IUS was also performed at week 12 (Fig. 1). The disease was considered clinically active if the Harvey–Bradshaw Index (HBI) was higher than 4.14 The Montreal Criteria were used to define disease extent.15

Fig. 1.

Cohort and design of the study. Abbreviations: IC, colonoscopy; IUS, intestinal ultrasound; HBI, Harvey-Bradshaw index; FC, faecal calprotectin; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Outcomes

The primary objective was to evaluate whether ultrasound remission (BUSS ≤3.52) at week 12, after biologic induction, could predict endoscopic remission (SES-CD ≤2) in the long-term.

The secondary objectives were: 1) to evaluate the role of FC at different cut-off values, <50, <100 and < 250 mcg/g, and of CRP <5 mg/L, at week 12 as predictors of endoscopic remission at the final visit; 2) the role of HBI ≤4 at week 12 as predictor of endoscopic remission at the final visit; 3) to find the best cut-off of IBUS-SAS to detect endoscopic remission (SES-CD ≤2); 4) to compare the ROC curves of BUSS, IBUS-SAS and BWT in order to find the best model to detect endoscopic remission (SES-CD ≤2); 4) to evaluate whether ultrasound remission (BUSS ≤3.52) at week 12, after biologic induction, could predict ultrasound remission in the long-term.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of the data are presented as medians (interquartile range), or as percentages when appropriate. Logistic regression analysis was performed to analyse the association between ultrasound remission at week 12, as defined by a BUSS ≤3.52, and endoscopic remission, as defined by SES-CD ≤2, at the final visit. The presence of endoscopic remission was the outcome variable (or dependent variable) (i.e., a binomial variable taking the value 1 if SES-CD ≤2, and the value 0 if SES-CD >2). BUSS ≤3.52, and other non-invasive parameters, including FC at different cut-off values, <50, <100 and <250 mcg/g, CRP <5 mg/L and HBI ≤4 were employed as explanatory variables (or independent variables). In the univariable analysis, a criterion of p < 0.10 was used to identify candidate predictors. A multivariable model was then fitted using a “backwards elimination procedure”. All variables with p < 0.05 were retained in the model. Contingency tables taking into account presence or absence of endoscopic remission at the final visit, in relation with ultrasound remission at week 12 and ultrasound response during biologic therapy, were constructed to determine the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and accuracy (how closely a given result aligns with the true or expected value) of BUSS. Reliability between ultrasound remission at week 12 and endoscopic remission at the final visit was assessed using kappa statistics.

Correlation between BUSS, IBUS-SAS and SES-CD at the final visit was assessed using the Spearman rank correlation test. Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) was used to determine cutoff values for IBUS-SAS for detecting endoscopic remission. Finally, AUROC of BUSS, IBUS-SAS and BWT were compared in order to find the best model to assess endoscopic remission.

We planned to treat missing data as worst-case scenario should any patients be lost to follow-up. Namely, the ultrasound data would be considered non-predictive of endoscopic remission.

All statistical tests are two-sided. p-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Stata software was used for all statistical analyses (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

The sample size was based according to the rules of thumb, for which the sample size should be 10 times or greater than the number of predictors (i.e., at least 60 patients in total).16 We considered that a sample size of 93 would be acceptable. In addition, it was determined by practical considerations (i.e. time, availability of eligible patients and cost), but also aiming to reach a similar or even higher sample size compared with relevant studies,17 in which IUS or other imaging tools, such as magnetic resonance imaging, were shown to assess response to therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Patient and public engagement

Patients were actively encouraged to participate in order to provide evidence on the use of non-invasive tools for the management of their disease. The role of patients within this study was highlighted during the annual meeting with the patients held at our institution. Patients were aware that their participation was useful to advance knowledge and to improve quality of care for themselves and the patients’ community.

Role of the funding source

The funders had no role in data collection, analysis, or interpretation of this manuscript. All authors confirm their participation in the shaping of the manuscript, had access to the data and accept responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Study population

692 patients with Crohn's disease were eligible during the enrollment phase. 169 patients had active Crohn's disease. 76 were excluded because they were participating in other studies. Finally, 93 were enrolled and completed the study, with no patient lost at follow-up.

43% of the patients were treated with adalimumab, 43% with ustekinumab, 9% with infliximab, and 5% with vedolizumab (Table 1). After a median period of 12.8 months (SD 4.2, IQR 9.9–15.6 months), 22 (24%) patients achieved endoscopic remission (SES-CD ≤2), and 29 (31%) ultrasound remission (BUSS ≤3.52). We found a statistically significant, high positive correlation between BUSS and SES-CD at the final visit [r = 0.525, 95% CI 0.360–0.658; p < 0.001]. Change of clinical characteristics over time are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. Specifically, BUSS significantly decreased from week 0 to week 12 (median 5.85 vs 4.95; p < 0.001). Conversely no further significant changes were observed between week 12 and the final visit (median 4.95 vs 4.95; p = 0.13). Similarly, CRP and calprotectin decreased mainly within the first 12 weeks (median 6.4 vs 2.8; p < 0.001; median 235 vs 93.6; p = 0.001; respectively). HBI decreased significantly throughout the time period [median 5 at week 0 vs 2 at week 12; vs 1 at the final visit (p < 0.001 week 0 vs week 12 and the final visit; p = 0.005 week 12 vs final visit)]. BUSS values were significantly lower at all the time points in the patients who achieved endoscopic remission compared with patients did not (at week 0, p = 0.013; at week 12, p < 0.001; at the final visit, p < 0.001). CRP and calprotectin were significantly lower at week 12 and at the final visit (p = 0.004 and p = 0.008; p = 0.013 and 0.049, respectively). Conversely HBI was not significantly different in patients having endoscopic remission at any of the time points (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients.

| Patients included in the study (N = 93) | |

|---|---|

| Sex, N (%) | |

| Male | 53 (57) |

| Female | 40 (43) |

| Age at diagnosis, year (q1–q3) | 26 (21–41) |

| Disease duration, year (q1–q3) | 5.9 (1.7–11.3) |

| Disease location, N (%) | |

| L1 ileal | 47 (51) |

| L2 colonic | 7 (7) |

| L3 ileo-colonic | 39 (42) |

| Disease behavior, N (%) | |

| B1 inflammatory | 52 (56) |

| B2 stricturing | 30 (32) |

| B3 penetrating | 11 (12) |

| Perianal disease, N (%) | 21 (23) |

| Previous surgery, N (%) | |

| 1 surgery | 32 (34) |

| >1 surgery | 1 (1) |

| Smoking, N (%) | |

| Active | 36 (39) |

| Past | 26 (28) |

| Never | 30 (33) |

| Previous use of biologics, N (%) | |

| 1 biologic | 30 (32) |

| >1 biologic | 15 (16) |

| Never | 48 (52) |

| Use of steroids, N (%) | |

| Concomitant | 13 (14) |

| Past | 80 (86) |

| Use of immunosuppressants, N (%) | |

| Concomitanta | 7 (7) |

| Past | 34 (37) |

| Never | 52 (56) |

| Biological therapy started, N (%) | |

| Adalimumab | 40 (43) |

| Infliximab | 8 (9) |

| Ustekinumab | 40 (43) |

| Vedolizumab | 5 (5) |

Data are presented as medians (interquartile range) or percentages when appropriate.

Five patients took azathioprine and 2 patients methotrexate.

Fig. 2.

Change of clinical characteristics over time, according with the achievement of the endoscopic outcomes. Data are presented as medians (interquartile range) in patients achieving endoscopic remission vs patients not achieving endoscopic remission. The asterisk symbols indicate the presence of statistical significance. A) BUSS: at week 0, 5.33 (4.43–5.93) vs 6 (5.19–6.83), p = 0.013; at week 12, 2.89 (2.25–4.50) vs 5.55 (4.38–6.15), p < 0.001; at the final visit, 2.32 (2.25–2.63) vs 5.33 (4.53–6.23), p < 0.001. B) HBI: at week 0, 4.5 (1–7) vs 6 (2–8), p = 0.66; at week 12, 1 (0–4) vs 2 (1–5), p = 0.19; at the final visit, 1 (0–3) vs 1 (0–4), p = 0.60. C) CRP: at week 0, 4.95 (1.7–19.8) vs 6.8 (3.7–16.2), p = 0.40; at week 12, 1.2 (0.85–2.25) vs 3.7 (1.9–9.72), p = 0.004; at the final visit, 1.9 (0.82–4.87) vs 4.5 (1.7–7.15), p = 0.013. D) FC: at week 0, 249 (42–755) vs 253 (64–635), p = 0.88; at week 12, 32 (11–117) vs 105 (37–296), p = 0.008; at the final visit, 62 (20–142) vs 124 (60–260), p = 0.049. Abbreviations: BUSS, Bowel Ultrasound Score; HBI, Harvey-Bradshaw index; CRP, C-reactive protein; FC, faecal calprotectin.

Early predictors of risk of endoscopic remission

The multivariable analysis among all the variables considered at week 12 identified BUSS ≤3.52 as the only independent predictor of endoscopic remission (SES-CD ≤2) at the final visit [OR 9.93, 95% CI 3.10–31.80; p < 0.001] (Table 2). Moderate reliability [k = 0.42 (0.10–0.21)] was observed between BUSS ≤3.52 at week 12 and SES-CD ≤2 at reassessment. Sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) (%, 95% CI) of BUSS ≤3.52 at week 12 for detecting endoscopic remission at the final visit were 59 (36–79), 85 (74–92), 78 (69–86), 54 (33–74), and 87 (77–94), respectively. BUSS ≥1.2 reduction had a sensitivity of 86% (95% CI 65–97), specificity of 63% (95% CI 51–75), accuracy of 69% (95% CI 58–78), PPV of 42% (95% CI 28–58) and a NPV of 94% (95% CI 83–99), in predicting patients who achieved SES-CD ≤2 (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 2.

Impact of non-invasive tools at week 12 on the risk of endoscopic remission (SES-CD ≤2) at the final visit.

| Univariable analysis |

Multivariable analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Parameters | ||||

| BUSS ≤3.52 | 7.87 (2.71–22.87) | <0.001 | 9.93 (3.10–31.80) | <0.001 |

| Calprotectin μg/g | ||||

| <50 | 3.58 (1.25–10.24) | 0.017 | ||

| <100 | 3.77 (1.21–11.70) | 0.021 | ||

| <250 | 2.93 (0.60–14.14) | 0.17 | ||

| CRP <5 mg/L | 2.66 (0.80–8.87) | 0.11 | ||

| HBI <5 | 1.33 (0.43–4.09) | 0.61 | ||

Abbreviations: SES-CD, Simplified endoscopic activity score for CD; BUSS, Bowel Ultrasound Score; CRP, C-reactive protein; HBI, Harvey-Bradshaw index.

In bold, the significant p-value (p < 0.05 value).

Early predictors of risk of ultrasound remission

BUSS ≤3.52 at week 12 was the only independent predictor of ultrasound remission (BUSS ≤3.52) at the final visit [OR 7.27, 95% CI 2.28–23.14; p < 0.001] (Supplementary Table S3).

Cut-off values for IBUS-SAS

IBUS-SAS correlated significantly with SES-CD [r = 0.544, 95% CI 0.382–0.673; p < 0.001]. Based on the receiver operating characteristic curve, we selected IBUS-SAS ≤22.8 as the best cut-off value to determine endoscopic remission (SES-CD <2). Sensitivity and specificity were 95% (95% CI 77–99) and 83% (72–91), respectively [AUROC 0.906, 95% CI 0.827–0.957].

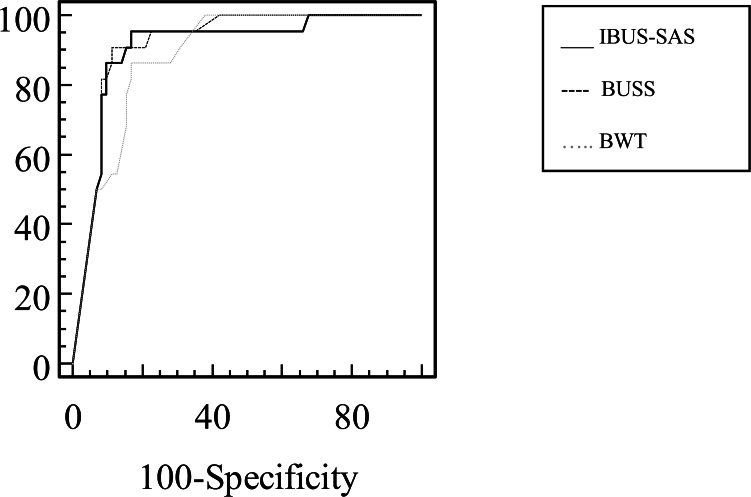

We found a statistically significant high positive correlation between BUSS and IBUS-SAS at the final visit [r = 0.891, 95% CI 0.840–0.927; p < 0.001]. The analysis of ROC curves comparing BUSS and IBUS-SAS showed no statistically significant differences in their abilities to detect endoscopic remission (p = 0.46). In contrast, BUSS exhibited superiority over BWT (AUC of 0.918 for BUSS compared with 0.885 for BWT (p = 0.007)) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of ROC curves of IBUS-SAS (AUC 0.906, 95% CI 0.827–0.957), BUSS (0.918, 95% CI 0.843–0.965) and BWT (0.885, 95% CI 0.802–0.942) to discriminate endoscopic remission. IBUS-SAS vs BUSS, p = 0.46; IBUS-SAS vs BWT, p = 0.29; BUSS vs BWT, p = 0.007. Abbreviations: ROC curve, receiver operating characteristic curve; AUC, area under the curve; IBUS-SAS, International Bowel Ultrasound Segmental Activity Score; BUSS, Bowel Ultrasound Score; BWT, Bowel wall thickness.

Discussion

A ‘treat-to-target’ strategy involving vigilant treatment response assessment is strongly advised for managing patients with CD.2 IC forms the cornerstone of this strategy and patients frequently undergo multiple colonoscopies throughout their treatment journey. However, patient acceptance of this procedure remains limited. In contrast, IUS presents a non-invasive alternative that eliminates the need for preparation and contrast media, making it more favourable among patients. Moreover, IUS offers real-time feasibility, enabling swift clinical decision-making right at the point of care. BUSS is an ultrasonography-based score of luminal activity, developed in a large cohort of patients with CD, using IC as reference standard, and recently validated in an external cohort.9,11 BUSS detects accurately treatment response and predicts disease progression.9,10 Other IUS activity scores have been developed and validated for CD in recent years. However, sensitivity to change and predictive ability have not been assessed, or IC was not used as a reference standard.6,8

This study presents compelling evidence that achieving ultrasound remission, as indicated by a BUSS of 3.52 or less emerged as the sole predictor for endoscopic remission over the long term. We found that a BUSS greater than 3.52 by week 12 was associated with failure to achieve long-term endoscopic remission (NPV 87%) (Supplementary Figure S1 and S2). Should these findings be substantiated through further research, they could potentially steer the direction of treatment adjustments in cases where the initial ultrasound remission target has not yet been attained.

The effectiveness of IUS in assessing treatment response in CD patients is widely acknowledged and substantiated by evidence from substantial patient cohorts.3,4 However, it is important to note that a rigorous reference standard, such as IC, was not utilized. It is worth highlighting that a majority of IUS parameters demonstrated improvement within the initial 12 weeks of treatment, which aligns with our own findings. Notably, a recent milestone has been reached with the publication of the first multicentre interventional trial, involving centralized readings, that employs IUS for monitoring the response to ustekinumab. This trial delved into IUS response in correlation with endoscopic response and remission. Specifically, the absence of an IUS response by week 4 was linked to the lack of endoscopic response by week 48 (NPV of 73%).5 Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that, much like previous studies, the definitions of IUS response and remission lacked proper validation.18 A BWT measurement exceeding 3 mm has emerged as the most robust indicator for discerning disease activity.19 Cut-off thresholds for BWT concerning endoscopic response and remission have indeed been suggested.7 Nonetheless, it is important to recognize that thickening can be induced by almost all pathological conditions affecting the gut. Given that both acute inflammatory and chronic fibrotic alterations are almost universally present within the CD-affected bowel, it is advisable to also evaluate other activity parameters. Specifically, neovascularization and heightened vascularization play a pivotal role in driving persistent intestinal inflammation in CD.20 BUSS was built employing multivariable approach, with SES-CD serving as the benchmark reference standard. In this method, the beta coefficients derived from the conclusive model of each pertinent variable were transformed into a weighted score. BWT and CDS emerged as autonomous predictors for endoscopic activity.9 This approach effectively amplifies the significance of individual ultrasound parameters by assigning enhanced weights. Remarkably, the predictive capacity of the multivariable model surpasses that of the univariable counterparts, signifying its superior predictive performance. We conducted a comparative analysis of the accuracy between BUSS and BWT in the identification of endoscopic remission, revealing superior performance by BUSS. A standardized metric to communicate disease activity and therapeutic response are crucial in order to implement the use of IUS for the management of patients with CD, both in clinical practice than in clinical trials. The development of IBUS-SAS followed a rigorous methodological framework. This involved the integration of four essential IUS parameters: BWT, CDS, i-fat, and BWS. These parameters were correlated with the overall disease activity assessed using a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), forming the basis of the score.8 Through a rigorous evaluation using ROC curve analysis, we established that both IBUS-SAS and BUSS exhibited commendable diagnostic accuracy. As a result of these promising findings, we advocate for the adoption of these scores not only within clinical trials but also as valuable tools in routine clinical practice. A noteworthy aspect of this study lies in its proposition that IUS could serve as an early treatment target.

The correlation between clinical symptoms and the extent of mucosal inflammation in CD is notably weak, often leading to the discovery of significant mucosal inflammation during complete clinical remission. The CALM trial underscored the disparity between treatment outcomes, showcasing that relying solely on symptoms for treatment escalation yielded a lower rate of endoscopic remission compared with an approach incorporating clinical and biochemical activity assessment (specifically, FC and CRP).21 Despite this, patients themselves prioritize clinical symptoms as the paramount indicators for treatment.

While attaining clinical remission remains imperative, it must be coupled with demonstrable enhancement in inflammation measures.2 Among biomarkers, FC and CRP take precedence, with FC typically outperforming CRP. Although a FC threshold of 150 mg/g has been suggested to denote endoscopic remission, the limited reliability of FC (especially in CD) designates the range of 100–250 mg/g as a grey area, and even values below 600 mg/g can still correspond to minimal inflammation.2 In our study, FC values below both 50 and 100 exhibited an association with endoscopic remission during the univariable analysis; however, this correlation did not hold during the multivariable analysis. These findings point towards the potential superiority of a combined strategy involving IUS alongside faecal calprotectin, suggesting a more robust and comprehensive approach to assessment. Ultimately, the pronounced advantage offered by IUS in evaluating transmural remission propels our treatment objectives in CD towards more profound and consequential endpoints. Notably, aiming for the target of transmural remission appears to correlate with enhanced long-term outcomes and reduced risk of bowel damage, in contrast to the exclusive focus on achieving endoscopic remission.22,23 Importantly, it is worth noting that BUSS was able to forecast disease progression even among patients who had achieved endoscopic remission.9

This study has several notable strengths: 1) we utilized a validated ultrasound-based scoring system; 2) treatment response was evaluated in direct comparison to IC, the established gold standard; 3) both IUS and IC were conducted in a blinded manner; 4) treatment regimens remained consistent across the various procedures; 5) notably, we conducted a prospective longitudinal investigation in a real-world setting. However, certain limitations are also present in this study: 1) it is confined to a single centre; 2) while the sample size aligns with similar studies, it remains modest; 3) centralized readings were not employed for endoscopic and ultrasound findings; 4) the interval between IUS and colonoscopy extended up to 30 days, although as noted, patients in this study were on stable therapy during this time period; 5) the last evaluation at the final visit ranged from 10 to 15 months. We also acknowledge the limitation of having a single expert ultrasonographer performing the exams in this study but note that the established reliability of the two ultrasound parameters (BWT and CDS) used to construct BUSS is well-documented.

In conclusion, we demonstrate the utility of IUS as a highly precise tool for prognosticating treatment responses, thereby supporting its use as an early treatment benchmark. Specifically, individuals unable to attain a BUSS of 3.52 following biologic induction stand at an elevated probability of not achieving endoscopic remission during the subsequent assessment. These discoveries offer the potential for a non-invasive, proactive approach involving early and meticulous monitoring of patients. This strategy could encompass timely evaluations of treatment response, with the overarching goal of attaining the desired treatment outcome. Extensive multicentre validation studies are essential to substantiate these findings. Additionally, such studies can help identify additional cut-off values for BUSS that may be more tailored to specific clinical scenarios, such as patients undergoing surgery or predicting severe endoscopic activity, complications, and the development of damage.

Contributors

MA is guarantor of the article, she conceived and designed the study. CDA, FF, AZ and FDA collected all the data. MA performed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. GF, LPB, VJ, DTR and SD critically revised the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Data sharing statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of interests

MA received consulting fees from Nikkiso Europe, Mundipharma, Janssen, Abbvie, Ferring, Galapagos, and Pfizer; FF received consulting fees form Amgen, Abbvie, Janssen, Galapagos, and Pfizer; FD received consulting fee from Janssen, Galapagos, Sandoz, and Omega Pharma; V.J. received consulting fees from AbbVie, Alimentiv, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Asahi Kasei Pharma, Asieris, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Ferring, Flagship Pioneering, Fresenius Kabi, Galapagos, GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, Metacrine, Mylan, Pandion, Pendopharm, Pfizer, Protagonist, Prometheus, Reistone Biopharma, Roche, Sandoz, Second Genome, Sorriso Pharmaceuticals, Takeda, Teva, TopiVert, Ventyx, and Vividion; DTR received consulting fees from AbbVie, AltruBio, Bristol Myers Squibb, Connect Biopharma, Eli Lilly, InDex Pharmaceuticals, Iterative Health, Janssen, Pfizer Inc, Prometheus Biosciences, Reistone, and Takeda; LP-B declares personal fees from AbbVie, Alimentiv, Alma Bio Therapeutics, Amgen, Applied Molecular Transport, Arena, Biogen, BMS, Celltrion, CONNECT Biopharm, Cytoki Pharma, Enthera, Ferring, Fresenius Kabi, Galapagos, Genentech, Gilead, Gossamer Bio, GSK, HAC-Pharma, IAG Image Analysis, Index Pharmaceuticals, Inotrem, Janssen, Lilly, Medac, Mopac, Morphic, MSD, Norgine, Novartis, OM Pharma, ONO Pharma, OSE Immunotherapeutics, Pandion Therapeutics, Pfizer, Prometheus, Protagonist, Roche, Sandoz, Takeda, Theravance, Thermo Fisher, Tigenix, Tillots, Viatris, Vifor, Ysopia, Abivax; Stock options: CTMA; GF received consultancy fees from Takeda, Abbvie, Janssen, Pfizer, Celltrion, Sandoz, Amgen, Ferring, Gilead, Galapagos, BMS; SD received consulting fees from AbbVie, Alimentiv, Allergan, Amgen, Applied Molecular Transport, AstraZeneca, Athos Therapeutics, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Celltrion, Dr Falk Pharma, Eli Lilly, Enthera, Ferring Pharmaceuticals Inc., Gilead, Hospira, Inotrem, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Morphic, MSD, Mundipharma, Mylan, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz, Sublimity Therapeutics, Takeda, Teladoc Health, TiGenix, UCB Inc., Vial, Vifor. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102559.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary Table S1. Change of clinical characteristics over time. Supplementary Table S2. Diagnostic accuracy of BUSS in detecting endoscopic remission (SES-CD <2) at the final visit. Supplementary Table S3. Impact of non-invasive tools at week 12 on the risk of ultrasound remission (BUSS < 3.52) at the final visit.

Supplementary Figure S1.

Remission on IUS at week 12 and long-term endoscopic remission. BUSS 6.86 at week 0, BUSS 1.5 at week 12. SES-CD 11 at week 0, SES-CD 0 at the final visit. Abbreviations: IUS, intestinal ultrasound; BUSS, Bowel Ultrasound Score; SES-CD, Simple Endoscopic Score-Crohn’s Disease.

Supplementary Figure S2.

Week 12 absence IUS remission and no endoscopic remission at the final visit. BUSS 5.55 at week 0, BUSS 5.4 at week 12. SES-CD 14 at week 0, SES-CD 14 at the final visit. Abbreviations: IUS, intestinal ultrasound; BUSS, Bowel Ultrasound Score; SES-CD, Simple Endoscopic Score-Crohn’s Disease.

References

- 1.Torres J., Mehandru S., Colombel J.F., et al. Crohn's disease. Lancet. 2017;389:1741–1755. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31711-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner D., Ricciuto A., Lewis A., et al. STRIDE-II: an update on the selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE) initiative of the international organization for the study of IBD (IOIBD): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1570–1583. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calabrese E., Rispo A., Zorzi F., et al. Ultrasonography tight control and monitoring in Crohn's disease during different biological therapies: a multicentre study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:e711–e722. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kucharzik T., Wittig B.M., Helwig U., et al. Use of intestinal ultrasound to monitor Crohn's disease activity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:535–542.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kucharzik T., Wilkens R., D'Agostino M.-A., et al. Early ultrasound response and progressive transmural remission after treatment with ustekinumab in Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;21(1):153–163.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rimola J., Torres J., Kumar S., et al. Recent advances in clinical practice: advances in cross-sectional imaging in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2022;71:2587–2597. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-326562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Voogd F., Bots S., Gecse K., et al. Intestinal ultrasound early on in treatment follow-up predicts endoscopic response to anti-TNFα treatment in Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16:1598–1608. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novak K.L., Nylund K., Maaser C., et al. Expert consensus on optimal acquisition and development of the international bowel ultrasound segmental activity score [IBUS-SAS]: a reliability and inter-rater variability study on intestinal ultrasonography in Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:609–616. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allocca M., Craviotto V., Bonovas S., et al. Predictive value of bowel ultrasound in Crohn's disease: a 12-month prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;20(4):e723–e740. doi: 10.1016/J.CGH.2021.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allocca M., Craviotto V., Dell'Avalle C., et al. Bowel ultrasound score is accurate in assessing response to therapy in patients with Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;55(4):446–454. doi: 10.1111/APT.16700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dragoni G., Gottin M., Innocenti T., et al. Correlation of ultrasound scores with endoscopic activity in Crohn's disease: a prospective exploratory study. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17(9):1387–1394. doi: 10.1093/ECCO-JCC/JJAD068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daperno M., D'Haens G., Van Assche G., et al. Development and validation of a new, simplified endoscopic activity score for Crohn's disease: the SES-CD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:505–512. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01878-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vuitton L., Marteau P., Sandborn W.J., et al. IOIBD technical review on endoscopic indices for Crohn's disease clinical trials. Gut. 2016;65:1447–1455. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harvey R.F., Bradshaw J.M. A simple index of CROHN’S-DISEASE activity. Lancet. 1980;315:514. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92767-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satsangi J., Silverberg M.S., Vermeire S., et al. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749–753. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.082909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danese S., Fiorino G., Mary J.Y., et al. Development of red flags index for early referral of adults with symptoms and signs suggestive of Crohn's disease: an IOIBD initiative. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:601–606. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ordás I., Rimola J., Alfaro I., et al. Development and validation of a simplified magnetic resonance index of activity for Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:432–439.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ilvemark J.F.K.F., Hansen T., Goodsall T.M., et al. Defining transabdominal intestinal ultrasound treatment response and remission in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and expert consensus statement. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16:554–580. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kucharzik T., Tielbeek J., Carter D., et al. ECCO-ESGAR topical review on optimizing reporting for cross-sectional imaging in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16:523–543. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodsall T.M., Nguyen T.M., Parker C.E., et al. Systematic review: gastrointestinal ultrasound scoring indices for inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:125–142. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colombel J.F., Panaccione R., Bossuyt P., et al. Effect of tight control management on Crohn's disease (CALM): a multicentre, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390:2779–2789. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32641-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernandes S.R., Rodrigues R.V., Bernardo S., et al. Transmural healing is associated with improved long-term outcomes of patients with Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1403–1409. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castiglione F., Imperatore N., Testa A., et al. One-year clinical outcomes with biologics in Crohn's disease: transmural healing compared with mucosal or no healing. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:1026–1039. doi: 10.1111/apt.15190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1. Change of clinical characteristics over time. Supplementary Table S2. Diagnostic accuracy of BUSS in detecting endoscopic remission (SES-CD <2) at the final visit. Supplementary Table S3. Impact of non-invasive tools at week 12 on the risk of ultrasound remission (BUSS < 3.52) at the final visit.