Abstract

Background

Messages aimed at increasing uptake of vaccines have been modestly successful, perhaps in part because they often focus on why individuals should receive a vaccine. Construal Level Theory posits that messages emphasizing “how” to get a vaccine may be more effective at encouraging vaccination than emphasizing “why.” This message framing may be particularly important for COVID-19 booster acceptance.

Objective

To determine if pre-visit patient portal messages designed using Construal Level Theory increase rates of COVID-19 booster vaccination.

Design and Interventions

This 3-arm randomized trial was conducted across three large, diverse primary care clinics in Massachusetts between February and May 2022, testing the impact of “how” versus “why” framed pre-visit messages versus no messages (“usual care”). Messages were sent by patient portal two business days before a visit.

Participants

Adults with upcoming primary care visits who had electronic health record evidence of receiving their initial COVID-19 vaccination series but not a booster dose.

Main Measures

Receipt of a COVID-19 booster vaccination after the message was sent through the visit date (primary outcome) or 6 weeks (secondary outcome).

Key Results

A total of 3665 patients were randomized (mean age: 53.5 years (SD: 17.3), 59% female, 65.2% White, 26.6% Hispanic), with 1249 to “how” 1199 to “why,” and 1217 to usual care arms. Except for clinic and preferred language, characteristics were well balanced across arms. Rates of COVID-19 booster were 13.6% (usual care), 11.7% (“how”) (odds ratio (OR) “how” vs usual care: 0.87, 95%CI: 0.67–1.14), and 13.7% (“why”) (“why” vs usual care: OR: 1.01, 95%CI: 0.81–1.28). At 6 weeks, “why” outperformed “how” for vaccination (OR: 1.26, 95%CI: 1.06–1.49), with no difference versus usual care.

Conclusions

We found no differences on visit booster receipt after single pre-visit portal messages designed using Construal Level Theory. Further studies to identify effective messaging interventions are needed, especially as additional doses are recommended.

Clinical Trial Registration

This trial is registered at clinicaltrials.gov, ID: NCT04871776. Initial release occurred 04/30/2021.

KEY WORDS: COVID-19 booster vaccinations, messaging

INTRODUCTION

COVID-19 vaccinations provide robust protection against serious illness and death; despite this, the uptake of booster vaccines has been modest.1 For other vaccines, such as influenza, tailored outreach to patients using behavioral science has modestly increased uptake,2, 3 but interventions to increase the uptake of COVID vaccination have had mixed results.4–9 Less is known about how to encourage receipt of booster vaccinations for COVID-19, a behavior likely to be increasingly important if yearly doses are recommended moving forward.

To date, messages to increase the uptake of COVID-19 vaccination have often focused on why individuals should receive the vaccine.5 However, messages that describe how to do something may be more effective at inducing behaviors that are psychologically near (e.g., imminent, personal), like scheduling a vaccination appointment within a week.10 Specifically, Construal Level Theory posits that messages emphasizing “why” a person should choose a behavior elicit “high-level” construals, which are characterized by abstract thinking and a deliberative mindset and so may be less likely to induce an action. Conversely, messages emphasizing “how” to do something evoke “low-level” construals, characterized by concrete thinking and an implementation mindset, and may be better at encouraging a specific action.10–13

To our knowledge, Construal Level Theory has not been explicitly tested for any vaccine messaging, even though successful message interventions have often seemed to invoke low-level construals.2, 14, 15 For example, messages stating that a flu vaccine dose was “reserved” for the patient at their upcoming appointment (low-level construal) were more effective than messages talking about protecting loved ones (high-level construals).2 Similarly, information on where and when to receive the flu shot outperformed other messages highlighting either positive gains from vaccination or potential losses from not getting vaccinated,14 and a map of flu vaccine locations was more effective than messaging about potential losses or an entry to win a $100 gift card.15 However, specifically emphasizing “how” or “why” in otherwise similar messages has not been previously explicitly tested.

Further, COVID-19 booster vaccination messaging may be a particularly good application for studying Construal Level Theory given its emotional and political valence. We hypothesized that “how” messages would be more effective than “why” messages overall because of the implementation mindset that “how” messages are more likely to induce. Because COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy differs by age, gender, and race,16, 17 demographic groups may respond differently to alternative framing of messages, which could help target future vaccine messaging to increase effectiveness. Thus, in this trial, we tested the effectiveness of “how” versus “why” framed, pre-visit patient portal messages compared to no messages to increase COVID-19 booster vaccination rates. Our secondary objective was to explore potential subgroups where one type of messaging may be particularly impactful.

METHODS

This 3-arm pragmatic randomized controlled trial tested the effectiveness of “how” versus “why” framed pre-visit patient portal messages versus no messages on COVID-19 booster rates. Pragmatic features of this trial include the use of routinely collected electronic health record (EHR) data to identify eligible patients and collect study outcomes, using the EHR for intervention delivery, and being embedded into the normal clinic workflow. The study was conducted at three primary care clinics within a large health system (Mass General Brigham) between February and May 2022. This trial was approved by our Institutional Review Board (2021P001308) and registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04871776).

Setting

The practices were selected because they serve racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse neighborhoods in greater Boston and offered COVID-19 boosters in clinic workflows. Patients with clinic visits for any reason could receive a booster if eligible based on their prior vaccination schedule recorded in the EHR, administered by clinic staff as part of their visit. Before and during the study period, in addition to the nationwide messaging and media attention on COVID-19 vaccinations, there was some general messaging encouraging vaccination from the health system, although not prior to any primary care office visit, nor directly from the practices. This non-specific messaging included intermittent (approximately every other month) untargeted messages sent through the patient portal on behalf of the health system chief equity officer and other efforts, including mailed letters and mobile vaccination vans traveling in some communities, but they focused on the primary vaccination series and not boosters.

Participant Identification

Eligible patients were identified using a reporting function in the EHR and (1) were ≥ 18 years of age, (2) had received a primary COVID-19 vaccination series but not a booster based on pre-visit EHR information, (3) had an upcoming in-person primary care visit in a study clinic, and (4) used the EHR’s patient portal. Patients who had an EHR-recorded allergy to any COVID-19 vaccine were excluded. Patient identification relied on vaccination information in the EHR which had several inputs: (1) vaccines administered within the health system, (2) provider entry based on patient vaccination cards or self-report, and (3) electronic queries by the health system of the Massachusetts Immunization Information System (MIIS) registry, which records and electronically shares all vaccinations administered statewide. The health system regularly queried MIIS to identify patients who newly received their initial COVID vaccination series. For booster doses, queries occurred less frequently and sometimes only upon arrival for a visit.

Randomization was performed within each clinic at the level of the clinic day. Because it was technologically impossible to randomize individual patients within the EHR reports used to identify patients each day, randomization could not be performed at the patient level. To randomize clinic days, random blocks of 6 were created and used to allocate all the occurrences of each weekday within each clinic through the study period such that by study completion a balanced number of each day of the week within each clinic in each arm was expected. In other words, within each clinic, each weekday (e.g., Mondays) had an equal chance of being randomly allocated to each of the three arms. Randomization was concealed such that no provider or patient was aware of assignment of clinic days. Primary care providers were briefed on the study before launch but were blinded to assignment of clinic days such that they did not know if or which type of message their patients would receive each day.

Interventions

Intervention messages were designed based on prior research, and guided by Construal Level Theory, with our team including behavioral science expertise.10, 11 Specifically, messages were designed to be similarly short, consistent with a 6th grade reading level, and vary only slightly in content so that one message emphasized “why” to get boosted (high-level construals) and the other emphasized the pragmatics of “how” to get boosted (low-level construals, both in Table 1). Messages were translated into the 7 most common languages used at the clinics (Arabic, Bosnian, Chinese Mandarin, Haitian Creole, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish).

Table 1.

Text of “How” and “Why” Portal Messages

| “How” message | “Why” message |

|---|---|

| Subject: How to get your COVID-19 booster: Opportunity at your upcoming visit | Subject: Get your COVID-19 booster to stay protected: Opportunity at your upcoming visit |

|

Dear Patient, Our records indicate that you are eligible to receive a booster shot against COVID-19 (if you have already received one, please ignore this message). You have an upcoming visit with your primary care provider, and a booster should be available for you. Please ask about a booster shot at your visit. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends a booster, regardless of which vaccine you received before. The booster dose is free. Alternatively, you can schedule your booster at another MGB location through https://covidvaccine.massgeneralbrigham.org/ or locally at https://vaxfinder.mass.gov/ or vaccines.gov. Please do not reply to this message. You may ask questions and/or update your vaccine status with your provider during your upcoming visit. Sincerely, Your Care Team Mass General Brigham Click here for COVID-19 information in English, Spanish, Portuguese, Arabic, Chinese, Russian, and Haitian Creole. |

Dear Patient, The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends a booster shot to maintain your immune response. The booster is one way to slow the spread, protect yourself and your loved ones. It will help us get back to doing more of what we loved to do before the pandemic. Our records indicate that you are eligible to receive a booster shot against COVID-19 (if you have already received one, please ignore this message). The CDC recommends a booster, regardless of which vaccine you received before. The booster dose is free. A booster should be available for you at your upcoming visit with your primary care provider. Alternatively, you can schedule your booster at another MGB location through https://covidvaccine.massgeneralbrigham.org/ or locally at https://vaxfinder.mass.gov/ or vaccines.gov. Please do not reply to this message. You may ask questions and/or update your vaccine status with your provider during your upcoming visit. Sincerely, Your Care Team Mass General Brigham Click here for COVID-19 information in English, Spanish, Portuguese, Arabic, Chinese, Russian, and Haitian Creole. |

Each day, we identified eligible patients using EHR reports and sent portal messages (or no message, according to arm) in their preferred language two business days before the visit. We included all in-person visit types scheduled on a given day (e.g., physical, follow-up, urgent). The sender of the message was listed as “Your MGH Primary Care Team” and displayed the photo of the research assistant sending the messages that day. Once sent, patients were automatically notified (by push notification from a smartphone app, email, text message, or multiple modalities, depending on individual patient settings) that a new message was available to read in their portal, unless the patient had specifically deactivated this feature.

After the study intervention period was complete, a random subset of 60 messages (10 per clinic per study arm) were reviewed manually within the EHR to determine if messages had been viewed.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was receipt of a COVID-19 vaccination from two business days before through the day of the scheduled visit. Intervention messages were sent three business days before the scheduled visit, so the outcome window began the day after intervention messages were sent. The secondary outcome was receipt of any COVID-19 vaccination within 6 weeks, again beginning two business days before the scheduled visit. Both analyses were prespecified as intention-to-treat and thus included all eligible patients with upcoming visits on the randomized day.

Data for both primary and secondary outcomes were downloaded from the EHR 78 days after completion of all study interventions to ensure vaccine administrations were properly recorded and updated through the MIIS queries. The EHR and registry datasets were merged, and duplicate vaccination records were removed. In some cases (< 2%), there remained sets of vaccinations with administration dates within 1 week for the same patient. After chart review by study staff blinded to patient allocation, all cases with two administration dates within 1 week were reduced to one record, and the record with more complete information (e.g., vaccine lot number) was retained.

Because of the lag in registry data for booster vaccinations imported into the EHR for some patients, we conducted sensitivity analyses excluding patients who, based on later data, had actually already received their booster at the time eligibility was determined and study messages were sent.

Analyses

In our original sample size estimates, we had assumed a usual care arm vaccination rate of 20% and type I error rate of 0.05, as well as a type II error rate of 80%. With those assumptions, we estimated that including at least 3300 individuals would allow us to observe a 5 percentage point difference in vaccination rates compared to usual care. We also assumed a negligible impact of clustering with the weekday randomization scheme. Of note, we also chose not to formally adjust for multiple testing, because the groups share the same comparison group, and a recent systematic review reasoned that if each exposure was compared with control in a separate trial, no adjustment would be necessary.18, 19

Means and frequencies of baseline characteristics were used to describe the sample in each arm. Crude rates of the primary and secondary outcomes were also calculated.

For the study analyses, we used generalized estimating equations (GEE) with a logit link function and binary-distributed errors, adjusting for clinic-day clustering and including clinic as an adjustment variable for all models. In additional analyses, we also adjusted for key demographics, including race, sex, and ethnicity. We also performed sensitivity analyses among only those patients retrospectively identified as eligible for the booster at the time messages were sent, due to the lag in registry data importation for some patients. Lastly, we conducted exploratory subgroup analyses by age (above and below the median), sex, race (White, Black, other), ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic), EHR-recorded preferred language, and clinic.

RESULTS

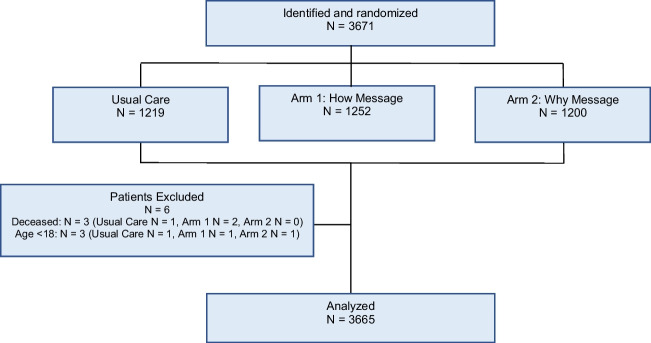

In total, 3671 patients were randomized and received messages; 6 patients were excluded because they were retrospectively determined to not meet eligibility criteria; therefore, 3665 patients were included in the analysis: 1249 in the “how” arm, 1199 in the “why” arm, and 1217 in usual care (Fig. 1). Their mean age was 53.5 years (SD: 17.3); 59% were female, 65.2% were White, and 26.6% were Hispanic. Except for clinic and preferred language, patient characteristics were well balanced across arms (Table 2). In the random sample of 60 patients, 70% of patients viewed the study messages. This was similar though slightly higher in the “why” arm (67% in “how” arm, 73% in “why” arm).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram.

Table 2.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients in the Trial

| How message arm | Why message arm | Usual care arm | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 1249 (34.08%) | 1199 (32.71%) | 1217 (33.21%) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 53.80 (17.36) | 53.23 (17.46) | 53.40 (16.96) | 0.703 |

| Female, N (%) | 733 (58.69%) | 697 (58.13%) | 736 (60.48%) | 0.471 |

| Partnered, N (%) | 675 (55.19%) | 655 (55.74%) | 702 (58.74%) | 0.168 |

| Race, N (%) | 0.678 | |||

| Asian | 48 (3.84%) | 49 (4.09%) | 51 (4.19%) | |

| Black/African American | 91 (7.29%) | 74 (6.17%) | 99 (8.13%) | |

| White | 766 (61.33%) | 724 (60.38%) | 718 (59.00%) | |

| Multiple/Other | 289 (23.14%) | 286 (23.85%) | 287 (23.58%) | |

| Unavailable/declined | 55 (4.40%) | 66 (5.50%) | 62 (5.09%) | |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | 0.322 | |||

| Hispanic | 322 (25.78%) | 324 (27.02) | 329 (27.03%) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 830 (66.45%) | 769 (64.14%) | 768 (63.11%) | |

| Unknown | 97 (7.77%) | 106 (8.84%) | 120 (9.86%) | |

| Preferred language, N (%) | 0.044 | |||

| English | 1004 (80.38) | 912 (76.06) | 930 (76.42%) | |

| Spanish | 179 (14.33%) | 214 (17.85%) | 223 (18.32%) | |

| Other | 66 (5.28%) | 73 (6.09%) | 64 (5.26%) | |

| Clinic | 0.005 | |||

| 1 | 531 (42.51%) | 511 (42.62%) | 463 (38.04%) | |

| 2 | 529 (42.35%) | 527 (43.95%) | 528 (43.39%) | |

| 3 | 189 (15.13%) | 161 (13.43%) | 226 (18.57%) | |

| Scheduled visit weekday, N (%) | 0.173 | |||

| Monday | 245 (19.62%) | 259 (21.60%) | 237 (19.47%) | |

| Tuesday | 313 (25.06%) | 275 (22.94%) | 292 (23.99%) | |

| Wednesday | 241 (19.30%) | 258 (21.52%) | 284 (23.34%) | |

| Thursday | 255 (20.42%) | 225 (18.77%) | 208 (17.09%) | |

| Friday | 195 (15.61%) | 182 (15.18%) | 196 (16.11%) | |

| Baseline vaccinations, N (%) | ||||

| Flu shot in past year (N = 3665) | 582 (46.60%) | 542 (45.20%) | 537 (44.12%) | 0.465 |

| Ever received pneumonia vaccine (if age > 65) (N = 973) | 306 (91.62%) | 287 (88.58%) | 285 (90.48%) | 0.417 |

| Ever received a zoster vaccine (if age > 50) (N = 2101) | 374 (51.52%) | 329 (48.24%) | 322 (46.46%) | 0.160 |

| Tetanus vaccine in last 10 years (N = 3665) | 997 (79.82%) | 962 (80.23%) | 985 (80.94%) | 0.782 |

| Baseline utilization | ||||

| No. of medications, mean (SD) | 13.62 (17.83) | 13.77 (19.65) | 13.35 (18.34) | 0.856 |

p-values represent results of chi-square tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables across all 3 arms

Abbreviation: SD standard deviation, Flu Influenza, No. number. 72 patients had missing data for partnered variable and were classified as “not partnered

Rates of the primary outcome (vaccination through scheduled visit date) were 11.7% (“how” arm), 13.7% (“why” arm), and 13.6% (usual care arm), with no differences observed across arms in the intention-to-treat analysis (Table 3). For example, the odds ratio (OR) comparing “why” versus “how” was 1.20 (95%CI: 0.96–1.51). Rates also did not differ in intention-to-treat analyses adjusting for demographic characteristics. For the secondary outcome of vaccination through 6 weeks, there was also no difference comparing “how” versus usual care or “why” versus usual care (Table 3) in intention-to-treat analyses. However, the “why” arm led to a 26% greater odds of vaccination compared with the “how” arm (OR: 1.26, 95%CI: 1.06–1.49) at 6 weeks.

Table 3.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

| Odds ratio (95%CI) how vs usual care | Odds ratio (95%CI) why vs usual care | Odds ratio (95%CI) why vs how | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccination from intervention delivery through scheduled visit (primary outcome) | |||

| Intention-to-treat analysis | |||

| Unadjusted | 0.87 (0.67 to 1.14) | 1.01 (0.81 to 1.28) | 1.20 (0.96 to 1.51) |

| Adjusted | 0.88 (0.68 to 1.15) | 1.04 (0.82 to 1.32) | 1.22 (0.97 to 1.54) |

| Sensitivity analysis | |||

| Unadjusted | 0.91 (0.70 to 1.18) | 0.90 (0.69 to 1.18) | 1.01 (0.78 to 1.32) |

| Adjusted | 0.91 (0.70 to 1.19) | 0.91 (0.69 to 1.20) | 1.02 (0.79 to 1.33) |

| Vaccination through 6 weeks after intervention delivery (secondary outcome) | |||

| Intention-to-treat analysis | |||

| Unadjusted | 0.83 (0.67 to 1.01) | 1.03 (0.87 to 1.23) | 1.26 (1.06 to 1.49) |

| Adjusted | 0.83 (0.68 to 1.01) | 1.05 (0.88 to 1.25) | 1.26 (1.07 to 1.50) |

| Sensitivity analysis | |||

| Unadjusted | 0.82 (0.65 to 1.04) | 0.96 (0.78 to 1.18) | 1.20 (0.95 to 1.53) |

| Adjusted | 0.82 (0.65 to 1.05) | 0.97 (0.78 to 1.20) | 1.21 (0.94 to 1.54) |

All analyses are adjusted for clustering of patients within clinic day and clinic. The adjusted analyses also adjust for race, sex, and ethnicity. Sensitivity analyses include only patients who were retrospectively eligible for booster at the time of randomization (N = 2045)

Abbreviation: CI confidence interval

Using retrospectively available data, 1620 (44%) patients had already received a booster when they were identified as eligible and did not have an EHR record of that booster at that time. There were slightly more patients for whom this occurred in the “how” (44.9%) and usual care arms (44.5%) than in the “why” arm (43.1%). When excluding these retrospectively ineligible patients in our sensitivity analyses, the primary outcome results remained null (Table 3). In the secondary analysis of vaccination through 6 weeks, the magnitude of the OR comparing the “why” versus “how” arm was slightly lower than the intention-to-treat analysis and no longer statistically significant (i.e., OR: 1.20, 95%CI: 0.95–1.53).

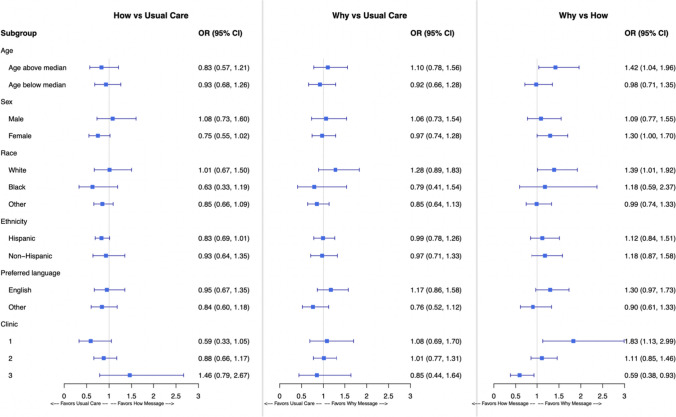

We also conducted exploratory subgroup analyses of the primary outcome by key demographic groups (shown in Fig. 2). There were no differences observed by age, sex, race, ethnicity, or preferred language. The only significant interaction was by clinic (p-value = 0.046), specifically that the “why” message outperformed the “how” message in one clinic and the opposite relationship in another (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Unadjusted primary analyses by subgroup. Note: The results of the primary analysis by demographic subgroup are plotted for each comparison. As with the primary analysis, all analyses are adjusted for clustering of patients within clinic day and clinic.

DISCUSSION

In this randomized trial of > 3000 patients, we found no difference in rates of COVID-19 booster vaccination among patients sent pre-visit messages that were framed to induce different mindsets and encourage vaccination compared with usual care. We did observe that invoking a “why” mindset could have been potentially more effective than “how” over a longer follow-up time. This may have been related in part to slight differences in the rates of patients who in retrospect had already received a booster vaccination in each arm at the time of intervention delivery, as supported by the slight change in the odds ratios between the intention-to-treat and sensitivity analyses. However, it is also possible that the “why” message was more effective than “how” in this context, possibly because booster receipt in clinic was easy or there was already high general knowledge about how and where to obtain boosters, both of which could have made the “how” message redundant. Though Construal Level Theory may still be an important factor to consider in other contexts, in this study, other factors probably had more of an impact on vaccination than the small changes in message framing.

Our findings contrast with some large prior studies of text messages for flu vaccination where vaccine receipt did differ based on message framing.2 However, one large study delivered messages by text which may be more easily readable or impactful than messages sent through patient portals. Interestingly, another large study of portal-based reminders for influenza vaccination for the 2020–2021 influenza vaccination season, which overlapped with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, did not demonstrate a difference between message types.20 This may have been due to the concurrent timing with the pandemic or mechanism of message delivery.

Studies specifically testing COVID-19 vaccine messaging have had mixed findings. Vaccine receipt has varied and likely depends on which COVID-19 vaccination was targeted, patient demographics and cultural context, and the intervention intensity and design.4, 5, 9, 21, 22 Interestingly, more intensive interventions to promote COVID-19 vaccination, including video messages with and without financial incentives, have also failed to increase COVID-19 vaccination rates.5 The overall lower rates of successful interventions for COVID-19 vaccination compared to messaging for other vaccine types suggest that it may be more difficult to influence COVID-19 vaccination behavior, though differences may also be due to more hesitant populations.5 However, to our knowledge, little has been studied for COVID-19 boosters, despite their increasing relevance if doses become recommended each year.

Simple pre-visit portal messages may not have been as effective in this context for several reasons. First, there was extensive attention to COVID-19 vaccinations at that time in the media, in communities, and from health systems. It is possible that one pre-visit message, even if appropriately worded and timely, may not have been a strong enough intervention in the background of many other influences on behavior. Additional potential factors contributing to the null findings could include the content of the message itself, its delivery through the patient portals, the messenger, a focus on boosters rather than original vaccination, or a more hesitant population remaining when the study was conducted. And, though this is similar to how electronic messages are delivered in clinical practice, in our random sample, 30% of patients did not view the message, which would dilute any effect.

Warranting further consideration, in exploratory subgroup analyses, there did seem to be variation in message effectiveness by clinic. Although this finding could be by chance, there are several factors that could explain this finding including differences in patient populations, the extent to which patients were made aware of vaccine availability, and whether providers recommended vaccines in visits. In each practice, primary care physicians generally have clinic on consistent days of the week, which means that the within-clinic day-level randomization would have balanced these potential contributing factors across study arms and thus not bias the overall results.

This study has several limitations. First, this was conducted in one health system that already had some messaging to encourage vaccine uptake and may differ from other clinical settings. Second, it was not possible to perfectly vary the messages only by their construal level, and while we carefully designed them to be very similar in readability, it is possible that the messages differed in some other way, such as their level of positivity. Third, information about boosters was not updated at the time of intervention delivery for approximately 40% of patients, which offers generalizable lessons to others seeking to use similar types of registry data in their health system.

In conclusion, our results suggest that unlike for other vaccinations, a single pre-visit portal message may be insufficient to increase COVID-19 booster receipt, at least in this context. Understanding what works and does not work to encourage vaccination is critical to achieving the potential benefits, especially as additional doses are recommended in the future. Identifying effective interventions within the primary care setting is needed.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30AG064199 to BWH (Choudhry PI). Dr. Lauffenburger (K01HL141538) and Dr. Haff (K23HL161480) were also supported in part by career development grants from the NIH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declarations:

Conflict of Interest:

Dr. Choudhry serves as a consultant to Veracity Healthcare Analytics and holds equity in RxAnte and DecipherHealth; unrelated to the current work, Dr. Choudhry has also received unrestricted grant funding payable to Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Humana. The remainder of the authors report no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Ms. Oran is now at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Agaku IT, Adeoye C, Long TG. Geographic, occupational, and sociodemographic variations in uptake of COVID-19 booster doses among fully vaccinated US adults, December 1, 2021, to January 10, 2022. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(8):e2227680. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.27680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Milkman KL, Patel MS, Gandhi L, et al. A Mega-Study of Text-Based Nudges Encouraging Patients to Get Vaccinated at an Upcoming Doctor’s Appointment. Social Science Research Network; 2021. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3780267.Accessed 23 Feb 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Reñosa MDC, Landicho J, Wachinger J, et al. Nudging toward vaccination: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(9):e006237. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Dai H, Saccardo S, Han MA, et al. Behavioural nudges increase COVID-19 vaccinations. Nature. 2021;597(7876):404-409. 10.1038/s41586-021-03843-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Jacobson M, Chang TY, Shah M, Pramanik R, Shah SB. Can financial incentives and other nudges increase COVID-19 vaccinations among the vaccine hesitant? A randomized trial. Vaccine. 2022;40(43):6235-6242. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.08.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Huf SW, Woldmann L, Crespo RF, et al. Implementing behavioural science informed letter interventions to increase COVID-19 vaccination uptake in uncontactable London residents: a difference-in-difference study in London, UK. Lancet Lond Engl. 2022;400 Suppl 1:S41. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02251-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Alhajji M, Alzeer AH, Al-Jafar R, et al. A national nudge study of differently framed messages to increase COVID-19 vaccine uptake in Saudi Arabia: a randomized controlled trial. Saudi Pharm J SPJ Off Publ Saudi Pharm Soc. 2023;31(9):101748. 10.1016/j.jsps.2023.101748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Rodriguez RM, Nichol G, Eucker SA, et al. Effect of COVID-19 vaccine messaging platforms in emergency departments on vaccine acceptance and uptake: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(2):115-123. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.5909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Mehta SJ, Mallozzi C, Shaw PA, et al. Effect of text messaging and behavioral interventions on COVID-19 vaccination uptake: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2216649. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.16649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Gollwitzer PM, Bayer U. Deliberative versus implemental mindsets in the control of action. In: Dual-Process Theories in Social Psychology. The Guilford Press; 1999:403–422.

- 11.Liberman N, Trope Y. The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75(1):5-18. 10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.5.

- 12.Czeizler A, Garbarino E. Give blood today or save lives tomorrow: Matching decision and message construal level to maximize blood donation intentions. Health Mark Q. 2017;34(3):175-186. 10.1080/07359683.2017.1346430. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Keller PA. Chapter 2: Social Marketing and Healthy Behaviors. In: Stewart DW, ed. Handbook of Persuasion and Social Marketing. Routledge; 2015:9-38.

- 14.McCaul KD, Johnson RJ, Rothman AJ. The effects of framing and action instructions on whether older adults obtain flu shots. Health Psychol Off J Div Health Psychol Am Psychol Assoc. 2002;21(6):624-628. 10.1037//0278-6133.21.6.624. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Baskin E. Increasing influenza vaccination rates via low cost messaging interventions. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(2):e0192594. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0192594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Vaccine Hesitancy and Acceptance: Data Segmentation Helps Address Barriers. Published online February 8, 2021. https://images.healthcare.pressganey.com/Web/PressGaneyAssociatesInc/%7Bd9dfcd63-5405-468d-ae43-1ad0aaf0fe83%7D_2021_PG_WP_Vaccine_Hesitancy_and_Acceptance.pdf.Accessed 25 Feb 2021.

- 17.Malik AA, McFadden SM, Elharake J, Omer SB. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;26:100495. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Wason JMS, Stecher L, Mander AP. Correcting for multiple-testing in multi-arm trials: is it necessary and is it done? Trials. 2014;15. 10.1186/1745-6215-15-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiol Camb Mass. 1990;1(1):43-46. [PubMed]

- 20.Szilagyi PG, Casillas A, Duru OK, et al. Evaluation of behavioral economic strategies to raise influenza vaccination rates across a health system: results from a randomized clinical trial. Prev Med. 2023;170:107474. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2023.107474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Patel MS, Fogel R, Winegar AL, et al. Effect of text message reminders and vaccine reservations on adherence to a health system COVID-19 vaccination policy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(7):e2222116. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.22116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Batteux E, Mills F, Jones LF, Symons C, Weston D. The effectiveness of interventions for increasing COVID-19 vaccine uptake: a systematic review. Vaccines. 2022;10(3):386. 10.3390/vaccines10030386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]