Abstract

Purpose

It remains unclear whether patients with HER2-negative, low-estrogen receptor (ER-low)-positive early breast cancer (BC) benefit from Oncotype DX® (ODX) testing.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective review of cases referred for ODX testing over a seven-year period from a breast biomarker testing referral center (n = 854). For each case, we recorded the ODX Recurrence Score (RS) along with percentage of ER nuclear positivity and staining intensity on immunohistochemistry. Our criteria for ER-low was defined as ≤10% cells with nuclear positivity and/or weak intensity of staining. Slides from all ER-low cases were reviewed and the reported ODX ER gene scores were recorded. We randomly selected a comparator group of 56 patients with ER > 10% positivity and non-weak staining intensity (ER-high).

Results

We identified 27 cases (3.2%) that met our criteria for ER-low. Of these, 92.6% had a high RS (>25), and 7.4% had a RS of 25. All cases with ≤10% ER nuclear positivity had a high RS. Most ER-low cases (85.2%) had ODX quantitative ER gene scores in the negative range, whereas all (100%) ER-high cases had positive ER gene scores.

Conclusion

ODX does not appear to add significant additional information to inform treatment decisions for most patients with ER-low BC. Incorporating weak ER staining intensity in addition to low percentage of nuclear positivity identifies about twice as many ER-low patients, although with reduced specificity for high RS. Our study supports the contention that most ER-low early BC should be regarded similarly to ER-negative BC.

Keywords: ER-low, Breast cancer, Estrogen receptor, Oncotype DX, Expression intensity, Immunohistochemistry, IHC

Highlights

-

•

A subset of hormone receptor positive breast cancers express only low levels of ER.

-

•

Most ER low breast cancers have high OncotypeDx Recurrence Scores.

-

•

Routine OncotypeDx testing may not be necessary for ER ‘low’ breast cancer.

-

•

Cases with >10% but weak ER expression should be further characterized.

1. Introduction

The estrogen receptor (ER) is a critical predictive biomarker in breast cancer (BC). The majority of BCs are ER-positive, currently defined by the ASCO-CAP guidelines as tumors with ≥1% ER nuclear staining by IHC [[1], [2], [3]]. ER positivity is associated with more favorable clinical outcomes and is predictive of response to endocrine therapies (ETs). Early-stage BC generally refers to disease that can be treated with curative intent. Adjuvant systemic therapy for patients with early-stage ER-positive BC includes ET, with or without adjuvant chemotherapy (CT), whereas those with ER-negative BC are usually offered adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone. The therapeutic benefits of ER-targeted therapies have been shown to correlate with the level of ER expression in tumor cells [4] and there has been increasing interest in the characterization of BC with low levels of ER expression, herein referred to as ER-low. The definition of ER-low versus ER-high varies but is commonly based on the percentage of tumor cell nuclei with ER expression by IHC [5]. Historically, ER-low has been defined with cut-offs of up to ≤20% nuclear positivity [1,[6], [7], [8]], but there has recently been an emerging consensus definition of ≤10% [1,9,10]. The proportion of early-stage BC that meets this ER-low criteria ranged from 2 to 7% in a recent review [1].

Oncotype DX (ODX) is a reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay that analyzes the expression of a 21-gene panel using paraffin-embedded tumor tissue to derive a recurrence score (RS) ranging from 0 to 100 [11]. The assay was developed specifically for ER-positive, HER2-negative early-stage BC, and provides a robust estimation of the absolute incremental gain in freedom from distant recurrence from the addition of adjuvant chemotherapy to standard endocrine therapy [[12], [13], [14], [15]]. The ODX report also includes an ER (as well as progesterone receptor [PR] and HER2) gene score as an external validation of the ER status of the case under analysis. The ODX RS has been validated in large retrospective and prospective clinical trials [16,17] and has been incorporated as an essential element in adjuvant therapy decision-making for this breast cancer subtype in jurisdictions where it is funded [18,19]. A RS of >25 predicts significant benefit from the addition of chemotherapy to ET for the postmenopausal patient population. For premenopausal patients, RS scores of >15 are associated with measurable chemotherapy benefit, with greater absolute benefit for those with RS > 25 [14,15].

In this study, we reviewed all ER-low BC cases referred for ODX from a biomarker testing referral center over a seven-year period. We used an expanded definition of ER-low that incorporates nuclear staining intensity in addition to the usual ≤10% cut-off for percentage of nuclear positivity. In doing so, we aimed to identify more patients with disease that could be classified as ER-low.

2. Methods

This study was approved as a Quality Improvement initiative by the Nova Scotia Health Research Ethics Board. We included all early-stage, invasive BC cases referred for ODX from our centre since 2016 (n = 854). 447 cases were in-house surgical pathology cases, and the remaining 407 were referred-in biomarker consultations from other regional hospitals. For each case, relevant clinicopathologic data was collected from the patient charts, including RS, year of BC diagnosis, and hormone receptor IHC results (ER% nuclear staining, ER staining intensity). Seventy cases with reported ER staining percentage but unreported ER intensity were included. We excluded 186 patients with unretrievable biomarker or RS data, the majority of which were referred-in cases in which hormone receptor testing was performed at a regional hospital.

Institutional ER IHC methods and reporting have remained unchanged since 2016, with consistent “optimal” designations in regular participation in external QA programs for breast biomarkers. Referred-in cases used their respective institutional protocols for biomarker testing. For in-house cases, ER IHC was performed using the Benchmark Ultra autostainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson AZ) with the SP1 monoclonal rabbit antibody (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson AZ). External and internal control status, along with standard pre-analytic factors, were recorded for all cases. Breast biomarker results were reported by one of four breast pathologists with ER staining intensity categorized into one of five categories (weak, weak-moderate, moderate, moderate-high, and high) that were numerically coded as an Intensity Score (IS) from 1 (weak) to 5 (high). ER-low cases were defined as those with ≤10% ER nuclear staining and/or weak (IS = 1) ER staining intensity. We classified ER-low cases into three subtypes: those with ≤10% nuclear staining and IS = 1 (“low weak”), those with ≤10% nuclear staining and IS ≥ 2 (“low only”), and those with IS = 1 and > 10% nuclear staining (“weak only”; Fig. 1). All ER-low cases (including cases reported at regional hospitals) had ER IHC slides reviewed by two authors who were blinded to the original biomarker results. The performance of internal and external controls was re-checked, and the IHC slides were re-scored (% staining and IS). Re-scores were only considered different from the original report if they resulted in a change in ER status or a change in ER-low subtype. For each of the ER-low cases, additional data was collected, including specimen type (biopsy versus resection), patient age, BC histologic type, tumor grade, type of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment received (if any), as well as progesterone receptor (PR) staining percentage and staining intensity, which was numerically coded into IS of 1–5 in the same manner as ER (see Supplementary Information). The proportions of patients meeting ER-low criteria for each calendar year were calculated together with exact 95% binomial confidence intervals.

Fig. 1.

Schema highlighting the variation in estrogen receptor (ER) expression strength within ER-positive breast cancer (BC). Four representative examples of ER-positive BC are shown (hematoxylin- and eosin-stained tumor sections with corresponding ER immunohistochemistry). Subtypes of ER-low breast cancer are highlighted in red boxes. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

ER gene scores were recorded from the ODX reports for each of the ER-low cases. A comparator group of ER-high patients was generated using a randomized list to select 56 ER-high patients, excluding those with unavailable biomarker, RS, or gene score data. The same additional histopathological data, specimen type (biopsy versus resection), patient age, BC histologic type, tumor grade, type of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment received (if any), as well as progesterone receptor (PR) staining percentage and staining intensity was also collected for these ER-high cases. Fisher's exact test was used to test for the difference in proportions of patients with positive ER gene scores (>25) between ER-high and ER-low patients. All analysis was performed in Stata v18 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

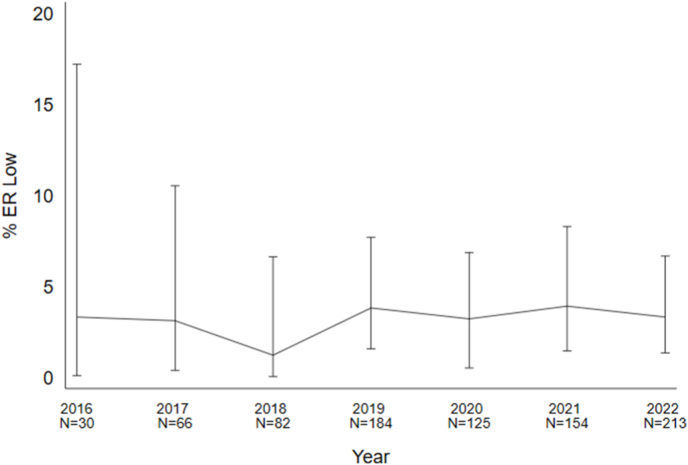

3. Results

Of the 854 BC specimens that were sent for ODX testing, we identified 27 cases (3.2%; 95% CI [2.1, 4.6]) meeting criteria for ER-low. Thirteen (48.1%; 95% CI [28.7, 68.1]) ER-low cases were identified on core biopsy, and 14 (51.9%; 95% CI [32.0, 71.3]) were identified on surgically excised specimens. The percentage of ER-low cases out of all cases sent for ODX referrals each calendar year ranged between 1.2 and 3.9% (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The percentage of Oncotype DX (ODX) breast cancer patients meeting ER-low criteria is shown for each calendar year, beginning at the initiation of ODX referrals from our centre. Errors bars represent 95% exact binomial confidence intervals.

The 27 ER-low cases were further divided into three ER-low subtypes: 12 cases (44.4%; 95% CI [25.5, 64.7]) had ≤10% ER nuclear staining and weak ER intensity (“low weak”), 13 (48.1%; 95% CI [28.7, 68.1]) had >10% ER nuclear staining and weak ER intensity (“weak only”), and 2 (7.4%; 95% CI [0.9, 24.3]) had ≤10% ER nuclear staining and greater than weak ER intensity (“low only”). When the IHC slides were reviewed for each of the ER-low cases at the time of the study, one case from 2016 was re-scored just below the 1% ER positivity threshold (ER staining had previously been reported as 2%, IS = 1). All other ER-low cases were re-scored in the same subcategory as in the initial biomarker report. For all cases, external and internal control tissues were confirmed to stain appropriately. Within the weak only group, ER positivity ranged from 15 to 90%. Of the ER-low cases, 25 (92.6%; 95% CI [75.7, 99.1]) had a RS of >25. The remaining two (7.4%; 95% CI [1.0, 24.3]) ER-low cases each had a RS of 25 and were both weak only, with one case having 50% ER positivity and the other having 70% ER positivity. All cases with ≤10% ER nuclear staining (n = 14, 1.6% of total ODX cases; 95% CI [1.0, 2.7]) had a RS > 25.

For the purposes of comparison, in a randomly selected group of 56 ER-high patients, only 6 (10.7%; 95% CI [4.0, 21.9]) had RS > 25 (Fisher's exact test p < 0.001). The ODX quantitative ER gene score was in the negative range (normalized gene expression score <6.5) in 23/27 (85.2%; 95% CI [66.3, 95.8]) of the ER-low cases. One ER low weak case had a positive quantitative gene score; this case had two tumors on one block, one of which was ER high and the other ER low by IHC. In the same randomly selected group of 56 ER-high cases, none had ER gene scores in the negative range. These findings are summarized in Table 1. There was a significant difference in the proportion of patients with ER gene score positivity between ER-low (n = 4, 14.8%; 95% CI [4.2, 33.7]) and ER-high cases (n = 56, 100%; 95% CI [93.6, 100]; Fisher's exact test p < 0.001). The biomarker, RS, histopathological, and clinical data (if retrievable) for each of the ER-low cases and comparator group of ER-high cases is available as Supplementary Information.

Table 1.

Oncotype DX ER Gene Scores and Recurrence Scores (RS) for early-stage ER-positive breast cancer, categorized by percentage of tumor cells with ER expression and intensity score (IS). *One case had two tumors in one block; one tumor was ER low and the other ER high, likely resulting in a positive quantitative ER gene score.

| ER Group | ER-Low subgroup | n | ER Gene score negative (%) | RS (range) | RS > 25 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER-low | Low weak | 12 | 11 (91.7)* | 27–70 | 12 (100) |

| Low only | 2 | 2 (100) | 42–56 | 2 (100) | |

| Weak only | 13 | 10 (76.9) | 25–65 | 11 (84.6) | |

| ER-high | 46 | 0 (0) | 0–43 | 6 (12.0) |

4. Discussion

ER-low BC is increasingly recognized as an important clinical entity which has led to the inclusion of this category in the latest ASCO/CAP guidelines and inclusion in BC pathology reports [3]. In our study, every ER-low case with ≤10% staining had a high RS (>25), suggestive of significant benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy. This is consistent with previous studies which have also observed that most ER-low BC referred for ODX have a high RS [7,20]. We included cases with >10% staining but with weak intensity which allowed for the identification of nearly twice as many ER-low cases than if we had only applied the ≤10% staining criteria. This expanded definition of ER-low was associated with decreased specificity for ER-low cases having a high RS (two of 13 patients in the weak only subgroup had RS of 25, compared to none of 14 in the group meeting the original ER-low definition having RS ≤ 25). An RS of 25 lies just below the threshold for no significant CT benefit in postmenopausal women and is associated with reduced but measurable benefit in premenopausal women [16]. Importantly, none of our ER-low cases had a RS allowing for confident avoidance of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Previous work examining the difference between weak ER staining intensity compared to low percentage of cells with staining is limited. In the only study to our knowledge addressing this question, a reduction in ER expression intensity on IHC was a better predictor of decreased BC survival than reduced staining percentage [21]. Further work is needed to better elucidate the differences between ER-low subsets but our results are supportive of the weak intensity only subgroup being included in future studies within this evolving area of BC research.

There are challenges inherent to the subjectivity in the grading of ER staining intensity. The same is true but less so for the determination of ER staining percentage. False positive ER-low results could lead to suboptimal adjuvant treatment and it is therefore important to consider preanalytical factors, such as cold ischemic time and specimen fixation protocols, either of which could contribute to falsely low ER staining intensity. There are also well-recognized analytic factors influencing the consistency of ER intensity reporting, most of which arise from different laboratories using different and closed-system protocols for tissue processing and staining [8,22,23]. A lack of standardized ER intensity thresholds was one of the principal contributing factors in at least one highly publicized instance involving significant under-reporting of ER-positive cases [24]. Increased institutional participation in large IHC quality control programs which monitor individual labs for differences from ER reference standards can help eliminate many of these issues [25].

Studies have repeatedly demonstrated an overall high concordance in ER IHC reporting between core biopsy and subsequent surgical specimens [26,27], however this has been challenged recently by a study showing high rates of ER negativity on surgical resections following core biopsies reported as ER-low [28]. Finally, there remain interpretive factors that may affect ER reporting, such as when pathologists fail to recognize decreased ER staining intensity in the internal control breast epithelium (if present), which can result in under-calling of both ER intensity and percentage. The various potential sources of pre-analytic and analytic error do not account for how most ER-low tumors (as determined by IHC) have been shown to have similar histomorphology and biological behaviour as ER-negative BC [[29], [30], [31]].

We have shown in the present study that our reported rate of ER-low BC has remained consistent amongst cases sent for ODX referrals over a seven-year period (Fig. 2), during which our biomarker reporting transitioned from being performed primarily on resection specimens to core biopsies. To address the limitation that referred-in specimens had hormone receptor testing performed at regional hospitals, slides for each of the ER-low cases were reviewed by two of the authors. On review, one case was re-scored just below the 1% ER positivity threshold (ER staining had previously been reported as 2%, IS = 1). This 2016 case was one of the oldest cases included and some staining had possibly faded over time. All other ER-low cases were re-scored in the same ER-low subcategory as in the initial biomarker report.

Using the consensus definition of ≤10% nuclear staining, our prevalence of ER-low cases (1.6%) is lower than that reported elsewhere (2–7%) [1,3]. Some oncologists may recommend adjuvant CT without the added information of ODX based on a pathology report of an ER-low tumor and other clinicopathologic factors. Since our study cohort was comprised only of patients who had ODX testing, our sampling may be unrepresentative of the true prevalence of ER-low BC in our region.

Previous studies have shown that semiquantitative IHC is highly concordant with ODX's RT-PCR-based assay in predicting ER status, and is arguably the more sensitive modality [32,33]. IHC is the current standard of care for ER assessment and given its practical utility in terms of cost, turnaround time, and the ability to correlate expression with histomorphology, it is likely to remain so for the near future. The fact that the vast majority of IHC-adjudicated ER-low BCs in our study (including one case with 90% weak ER staining) had ODX quantitative gene scores in the negative range further supports the ASCO-CAP recommendation to report tumors in the ER-low group as a separate subtype of ER positive disease. Artificial intelligence-based image analysis may serve as an aid to biomarker assessment by reproducibly detecting ER-low tumors, given that it has been shown to be capable of predicting ER status as well as response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in BC in some studies [34,35]. Use of image analysis however, has not been shown to be superior to visual estimations in the low range of ER expression [28].

Historically, treatment algorithms did not recognize ER-low BC as a distinct group. This was based on data that patients with 1–10% ER expression may benefit from ET and appeared have more favorable outcomes than ER-negative BC [36]. Later work however observed no benefit from ET in ER-low BC, firstly in 1–5% ER expressors [22], and later in 1–10% ER expressors [10,29,37,38]. A more recent study observed a non-statistically significant numerical trend toward ET benefit for breast cancer specific but not disease-free survival in ER-low BC [39]. On balance, current evidence suggests that patients with ER-low BC have decreased likelihood of benefit from ET compared to ER-high BC and studies addressing the use of adjuvant CT in ER-low BC have found that these patients benefit similarly to ER-negative BC [30,40]. Further work is needed to determine which histopathological features within the ER-low category are associated with responsiveness to CT and ET.

The principal aim of our study was to assess the utility of ODX testing for patients with ER-low BC. Consistent with previous findings, our work shows that ODX does not add significant additional information to inform adjuvant treatment decisions for most patients with ER-low BC, since the vast majority have a high RS predictive of significant benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy [7,20]. This adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that most ER-low BC has biologic similarities to ER-negative BC [1,4,29,41]. There is increasing evidence that eligible ER-low patients can be offered adjuvant chemotherapy without the need for ODX testing which would lessen cost as well as minimize treatment delay. Further work is required to unravel the features associated with clinicopathological heterogeneity within ER-low BC, and to better determine the degree of ET benefit for ER-low early BC. The incorporation of ER expression intensity represents an important step forward in better characterizing this clinically challenging entity.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or no-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Exemption for research ethics approval was granted by the Nova Scotia Health Research Ethics Board (January 4, 2023/REB FILE#: 1028820). This study was approved by the institution as a Quality Improvement Study/Initiative.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient information confidentiality, but may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

John Loggie: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Penelope J. Barnes: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Data curation. Michael D. Carter: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization. Daniel Rayson: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Gillian C. Bethune: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

J. Loggie, P. Barnes, M. Carter, and G. Bethune do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

D. Rayson declares the following:

- Honoraria for CME lectures from IPSEN, Novartis, Gilead, Astra Zeneca, Pfizer, Merck, Lilly.

- Clinical Trial Funding to Institution from IPSEN, Gilead, Astra Zeneca, Novartis, Pfizer.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Janis Breeze for her assistance with statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2024.103715.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Reinert T., et al. Clinical implication of low estrogen receptor (ER-low) expression in breast cancer. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.1015388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammond M.E.H., et al. American Society of clinical oncology/college of American pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2784–2795. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allison K.H., et al. Estrogen and progesterone receptor testing in breast cancer: ASCO/CAP guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1346–1366. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouchard-Fortier A., Provencher L., Blanchette C., Diorio C. Prognostic and predictive value of low estrogen receptor expression in breast cancer. Curr Oncol. 2017;24:106–114. doi: 10.3747/co.24.3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aldrees R., Gao X., Zhang K., Siegal G.P., Wei S. Validation of the revised 8th AJCC breast cancer clinical prognostic staging system: analysis of 5321 cases from a single institution. Mod Pathol. 2021;34:291–299. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-00650-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shousha S. Oestrogen receptor status of breast carcinoma: allred/H score conversion table. Histopathology. 2008;53:346–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milburn M., Rosman M., Mylander C., Tafra L. Is onco type DX recurrence score (RS) of prognostic value once HER2-positive and. Low-ER expression patients are removed? Breast J. 2013;19:357–364. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Layfield L.J., Gupta D., Mooney E.E. Assessment of tissue estrogen and progesterone receptor levels: a survey of current practice, techniques, and quantitation methods. Breast J. 2000;6:189–196. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2000.99097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fei F., Siegal G.P., Wei S. Characterization of estrogen receptor-low-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;188:225–235. doi: 10.1007/s10549-021-06148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yi M., et al. Which threshold for ER positivity? a retrospective study based on 9639 patients. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1004–1011. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sparano J.A., Paik S. Development of the 21-gene assay and its application in clinical practice and clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:721–728. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paik S., et al. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2817–2826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paik S., et al. Gene expression and benefit of chemotherapy in women with node-negative, estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3726–3734. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mamounas E.P., et al. Association between the 21-gene recurrence score assay and risk of locoregional recurrence in node-negative, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: results from NSABP B-14 and NSABP B-20. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1677–1683. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.7610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harvey J.M., Clark G.M., Osborne C.K., Allred D.C. Estrogen receptor status by immunohistochemistry is superior to the ligand-binding assay for predicting response to adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1474–1481. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sparano J.A., et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy guided by a 21-gene expression assay in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:111–121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalinsky K., et al. 21-gene assay to inform chemotherapy benefit in node-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2336–2347. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2108873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu X., et al. How Canadian oncologists use Oncotype DX for treatment of breast cancer patients. Curr Oncol. 2021;28:800–812. doi: 10.3390/curroncol28010077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yordanova M., Hassan S. The role of the 21-gene recurrence score assay in hormone receptor-positive, node-positive breast cancer: the Canadian experience. Curr Oncol. 2022;29:2008–2020. doi: 10.3390/curroncol29030163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giordano J., et al. Is there a role for the oncotype DX breast recurrence score genomic assay in estrogen receptor-low positive breast cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2022;40 564–564. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill D.A., et al. Estrogen receptor quantitative measures and breast cancer survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;166:855–864. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4439-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caruana D., Wei W., Martinez-Morilla S., Rimm D.L., Reisenbichler E.S. Association between low estrogen receptor positive breast cancer and staining performance. Npj Breast Cancer. 2020;6:1–6. doi: 10.1038/s41523-020-0146-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nkoy F.L., et al. Variable specimen handling affects hormone receptor test results in women with breast cancer A large multihospital retrospective study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:606–612. doi: 10.5858/134.4.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hede K. Breast cancer testing scandal shines spotlight on black box of clinical laboratory testing. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:836–844. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pérez T., et al. Modeling Canadian quality control test program for steroid hormone receptors in breast cancer: diagnostic accuracy study. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2016;24:679–687. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slostad J.A., et al. Concordance of breast cancer biomarker testing in core needle biopsy and surgical specimens: a single institution experience. Cancer Med. 2022;11:4954–4965. doi: 10.1002/cam4.4843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asogan A.B., Hong G.S., Arni Prabhakaran S.K. Concordance between core needle biopsy and surgical specimen for oestrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 status in breast cancer. Singap Med J. 2017;58:145–149. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2016062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makhlouf S., et al. The clinical and biological significance of estrogen receptor-low positive breast cancer. Mod Pathol. 2023;36 doi: 10.1016/j.modpat.2023.100284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poon I.K., et al. The significance of highlighting the oestrogen receptor low category in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2020;123:1223–1227. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-1009-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landmann A., et al. Low estrogen receptor (ER)–Positive breast cancer and neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy: is response similar to typical ER-positive or ER-negative disease? Am J Clin Pathol. 2018;150:34–42. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqy028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gloyeske N.C., Dabbs D.J., Bhargava R. Low ER+ breast cancer: is this a distinct group? Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;141:697–701. doi: 10.1309/AJCP34CYSATWFDPQ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Connor S., Beriwal S., Dabbs D. Concordance between semiquantitative immunohistochemical assay and oncotype DX RT-PCR assay for estrogen and progesterone receptors. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2010;18:268–272. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3181cddde9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraus J.A., Dabbs D.J., Beriwal S., Bhargava R. Semi-quantitative immunohistochemical assay versus oncotype DX® qRT-PCR assay for estrogen and progesterone receptors: an independent quality assurance study. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:869–876. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naik N., et al. Deep learning-enabled breast cancer hormonal receptor status determination from base-level H&E stains. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5727. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19334-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yousif M., et al. Artificial intelligence applied to breast pathology. Virchows Arch. 2022;480:191–209. doi: 10.1007/s00428-021-03213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sleightholm R., et al. Percentage of hormone receptor positivity in breast cancer provides prognostic value: a single-institute study. J Clin Med Res. 2021;13:9–19. doi: 10.14740/jocmr4398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prabhu J.S., et al. A majority of low (1-10%) ER positive breast cancers behave like hormone receptor negative tumors. J Cancer. 2014;5:156–165. doi: 10.7150/jca.7668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen T., et al. Borderline ER-positive primary breast cancer gains No significant survival benefit from endocrine therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Breast Cancer. 2018;18:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie Y., Yang L., Wu Y., Zheng H., Gou Q. Adjuvant endocrine therapy in patients with estrogen receptor-low positive breast cancer: a prospective cohort study. Breast. 2022;66:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2022.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dieci M.V., et al. Impact of estrogen receptor levels on outcome in non-metastatic triple negative breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy. Npj Breast Cancer. 2021;7:1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41523-021-00308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo C., et al. Clinical characteristics and survival outcome of patients with estrogen receptor low positive breast cancer. Breast. 2022;63:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2022.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient information confidentiality, but may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.