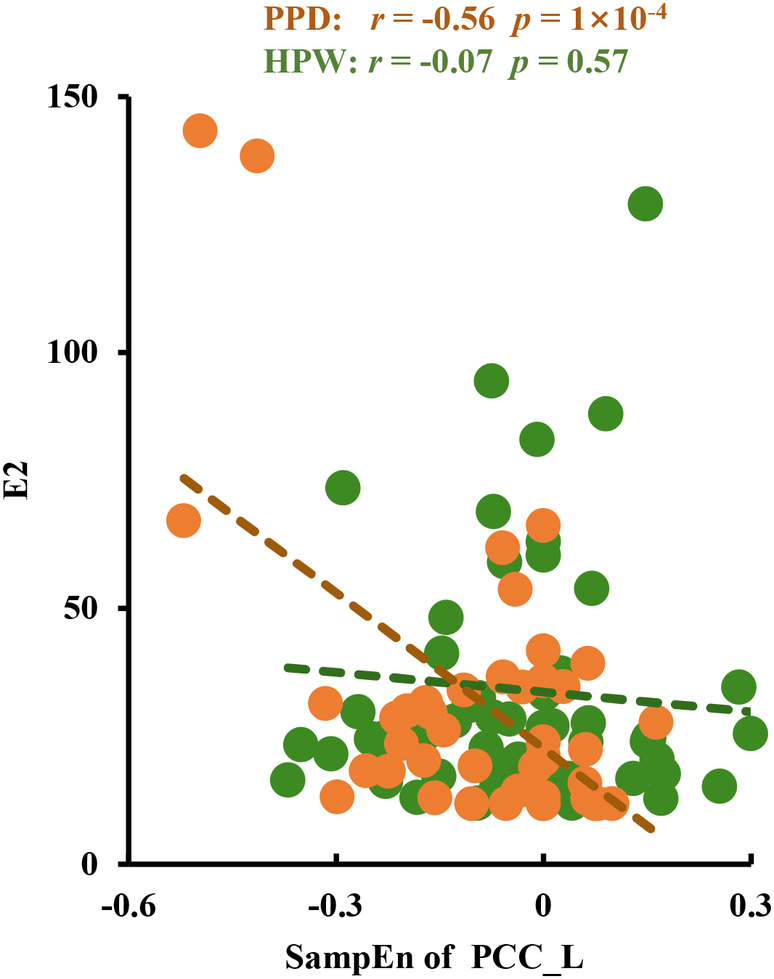

Abstract

Although Postpartum depression (PPD) and PPD with anxiety (PPD‐A) have been well characterized as functional disruptions within or between multiple brain systems, however, how to quantitatively delineate brain functional system irregularity and the molecular basis of functional abnormalities in PPD and PPD‐A remains unclear. Here, brain sample entropy (SampEn), resting‐state functional connectivity (RSFC), transcriptomic and neurotransmitter density data were used to investigate brain functional system irregularity, functional connectivity abnormalities and associated molecular basis for PPD and PPD‐A. PPD‐A exhibited higher SampEn in medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) and posterior cingulate cortex (PPC) than healthy postnatal women (HPW) and PPD while PPD showed lower SampEn in PPC compared to HPW and PPD‐A. The functional connectivity analysis with MPFC and PPC as seed areas revealed decreased functional couplings between PCC and paracentral lobule and between MPFC and angular gyrus in PPD compared to both PPD‐A and HPW. Moreover, abnormal SampEn and functional connectivity were associated with estrogenic level and clinical symptoms load. Importantly, spatial association analyses between functional changes and transcriptome and neurotransmitter density maps revealed that these functional changes were primarily associated with synaptic signaling, neuron projection, neurotransmitter level regulation, amino acid metabolism, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) signaling pathways, and neurotransmitters of 5‐hydroxytryptamine (5‐HT), norepinephrine, glutamate, dopamine and so on. These results reveal abnormal brain entropy and functional connectivities primarily in default mode network (DMN) and link these changes to transcriptome and neurotransmitters to establish the molecular basis for PPD and PPD‐A for the first time. Our findings highlight the important role of DMN in neuropathology of PPD and PPD‐A.

Keywords: functional connectivity, molecular basis, postpartum depression, postpartum depression with anxiety, sample entropy

The article reveal abnormalities in brain entropy and functional connectivity, predominantly in the default mode network (DMN), link these changes to the transcriptome and neurotransmitters, establishing for the first time the molecular basis of PPD and PPD‐A and highlighting the important role of the DMN in PPD and PPD‐A neuropathology.

1. INTRODUCTION

Maternal mental health in the early postpartum period are a global public health problem (Kimmel, 2020), with an estimated 12% of healthy mothers (without a history of depression) diagnosed with postpartum depression (PPD) and up to 70% of those with PPD having co‐morbid anxiety (Bobo & Yawn, 2014; Hendrick et al., 2000; Nakić Radoš et al., 2018; Ross et al., 2003; Shorey et al., 2018), that is, postpartum depression with anxiety (PPD‐A). PPD and PPD‐A lead not only to maternal mood disorders and behavioral changes (Falah‐Hassani et al., 2016; Muzik & Borovska, 2010), but also affect the mental health status of family members, especially their offspring (Goodman, 2004; Shonkoff and Garner, 2012). However, compared to PPD, PPD‐A was associated with more severe depressive symptoms (Farr et al., 2014; Goodman, 2004), longer response time to treatment (Hendrick et al., 2000), and increased risk of self‐harm ideation (Martin et al., 2018). Current clinical practice relies primarily on subjective psychological scales to assess anxiety and depressive symptoms (Falah‐Hassani et al., 2016; Han et al., 2023) making it difficult to accurately differentiate PPD and PPD‐A. Therefore, identifying neurofunctional biomarkers for PPD and PPD‐A is particularly important for precision diagnosis and therapy.

The human brain is a complex dynamic system (Başar, 2011). Brain entropy (BEN) is a physical measure to characterize system irregularity and thus may be potential to distinguish healthy and disease states by reflecting brain status (Pei‐Shan et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2014). BEN is calculated with resting‐state functional magnetic resonance imaging which is a non‐invasive technique to depict brain intrinsic spontaneous fluctuations (Rosen & Savoy, 2012; Saxe et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2013). The previous studies have demonstrated that sample entropy (SampEn) is more consistent and insensitive to missing data (Lake et al., 2002; Richman & Moorman, 2000). SampEn has been used to investigate the relationship between brain entropy and normal cognitive function and to reveal functional abnormalities in Alzheimer's disease, mild cognitive impairment, and depression patients (Pei‐Shan et al., 2017; Saxe et al., 2018; Wang, Niu, et al., 2017). These studies indicated that SampEn is an effective tool to characterize complex behaviors, disease pathogenesis and clinical manifestations.

Genetic effects of PPD have been reported on the basis of twin (Treloar et al., 1999) and family studies (Forty et al., 2006; Murphy‐Eberenz et al., 2006). However, the neurobiological and genetic mechanisms associated with brain functional changes of PPD and PPD‐A remain poorly understood, and the combination of neuroimaging with transcriptomic provides the opportunity to bridge the gap. Recently, Allen Human Brain Atlas (AHBA) was developed to link macroscopic brain structure and function properties with microscopic gene expression profiles to uncover potential molecular basis (Arnatkeviciute et al., 2019; Hawrylycz et al., 2012). A large number of literatures have applied spatial association analysis between neuroimaging measures and spatial transcriptomic data and identified the underlying genetic basis of brain functional organization patterns and structural and functional changes in brain disorders (Altmann et al., 2020; Anderson et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2021). In addition to AHBA atlas, the neurotransmitter density maps are from PET images of over 1200 healthy individuals and include 19 different neurotransmitter receptors and transporters for nine different neurotransmitter systems (dopamine, norepinephrine, 5‐HT, acetylcholine, glutamate, GABA, histamine, cannabinoids, and opioids) were constructed (Hansen et al., 2022). The neurotransmitter density maps provide a new tool to investigate the brain structural and functional changes associated neurotransmitters.

In this study, we aimed to use a newly developed brain entropy method and transcriptomic data to identify diagnostic neuromarkers and molecular basis for PPD and PPD‐A using resting‐state fMRI acquired from 62 healthy postnatal women (HPW), 45 PPD patients and 31 PPD‐A patients. Furthermore, enrich, neurotransmitter distribution and protein–protein interaction analyses were performed to identify the associated biological process, molecular functions and hubs of the identified genes.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Participants

The fMRI data in this study were obtained from a longitudinal project investigating the pathogenic mechanisms and influencing factors of PPD and PPD‐A in Chengdu, China. From June 1, 2018 to January 1, 2020 postpartum women were screened, recruited and diagnosed at the Maternity Clinic, West China Second University Hospital of Sichuan University by two experienced psychiatrists (Cheng, Hu, et al., 2022). Diagnosis was made according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM‐5) and the Chinese Classification and Diagnostic Criteria of Mental Disorders, Third Edition (CCMD‐3). The exclusion criteria of all participants are: (1) left‐handedness; (2) the presence of intracranial organic lesions affecting brain structure; (3) a history of suicide or any other Axis I mental disorders; (4) a history of drug or alcohol abuse; hormonal contraceptive and vasoactive drug use; and (5) contraindications to MRI (e.g., claustrophobia, etc.). A total of 138 participants including 62 HPW, 45 drug‐naive PPD patients and 31 drug‐naive PPD‐A patients were recruited. The clinical performances including load of postpartum depression, anxiety, sleep quality, and stress were evaluated by Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (Cox et al., 1987), Beck's anxiety inventory (BAI) (Beck et al., 1988), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck et al., 1961), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (Buysse et al., 1989), and Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (Cohen, 1988), respectively. This study was approved by the local ethics committee of West China Second University Hospital of Sichuan University and was in accordance with the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki, Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2. Resting‐state fMRI data acquisition

During MRI scanning, participants were asked to remain awake with their eyes closed and to keep relaxed. The fMRI data were acquired using a Siemens 3.0 T MRI system at the West China Second University Hospital of Sichuan University. No participants were found to fall asleep during the scan. The scan parameters were: repetition time (TR) = 3.05 s, echo time = 22.5 ms, flip angle = 30°, number of slices = 36, slice thickness = 4 mm, slice gap = 1 mm, field of view = 230 × 230 mm2, voxel size = 2.45 × 2.45 × 4 mm3, acquisition matrix = 94 × 94.

2.3. Resting‐state fMRI data preprocessing

The preprocessing steps for resting‐state fMRI were as follows: the first six volumes were removed to reduce the effect of magnetization imbalance, and the remaining images were aligned to the first volume to correct for the subject's head movements. Subjects with a shift more than 2.5 mm and angular motion more than 2.5° were excluded to minimize the effect of head motion, no subjects were excluded in this study. Then, all fMRI data were aligned to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) EPI template, resampled to a size of 3 × 3 × 3 mm3, and smoothed using an 8 mm Gaussian kernel. Next, covariates including Friston‐24 head movement parameters, whole brain mean, cerebral white matter and cerebrospinal fluid signals were regressed. All the data were filtered with a temporal bandpass of 0.01–0.1 Hz. Moreover, scrubbing method with linear interpolation was further used to eliminate the bad images exceeding the predefined criteria (frame displacement (FD), FD >0.5) for excessive motion.

2.4. Sample entropy (SampEn) calculation

SampEn which is defined as the negative logarithm of the conditional probability for two sequences mainly characterize the complexity of time series. The smaller SampEn means smaller complexity of the time series, the greater self‐similarity and the higher predictability (Richman & Moorman, 2000). The SampEn could accurately estimate the probability distribution function from a moderate number of time points of the fMRI time series (Saxe et al., 2018). The details for SampEn calculation can be found in previous studies (Abásolo et al., 2006; Molina‐Picó et al., 2011; Richman & Moorman, 2000). In this study, SampEn for resting‐state fMRI data is calculated as follows, defining x as a time series with the length of N for each voxel, exclusion of self‐matching (i ≠ j) and (1 ≤ i ≤ N − m) (Richman & Moorman, 2000). The data matrix is set up and the vector space of m is constructed, X m (i) = {x(i), x(i + 1), … x(i + m − 1)}, 1 ≤ i ≤ N − m + 1, which represents the value of m consecutive x's from point i. By defining the maximum distance between X m (i) and X m (j) as d[X m (i), X m (j)] = max k=0,…,m−1{|x(i + k) − x(j + k)|}, we counted the number of j whose distance between X m (i) and X m (j) is ≤r (1 ≤ i ≤ N − m, i ≠ j), it denoted as B i = num{d| X m (i), X m (j) | < r}. We define Bm i(r) = B i (N − m − 1)−1, Similarly, to the vector space of m + 1, we can get A i = num{d| X m+1(i), X m+1(j) | < r} and Am i(r) = A i (N − m − 1)−1. We define the probability of two sequences matching m points at a similar tolerance r as B m (r), and define the probability of two sequences matching m + 1 points at a similar tolerance r as A m (r):

| (1) |

| (2) |

The SanpEn is defined as:

| (3) |

In the calculation of SampEn, two parameter values must be considered and set, namely the embedding dimension m and the distance threshold r. According to the published literatures, it is known that SampEn shows good statistical properties when m = 2 and r in the range of 0.1–0.25 (Costa et al., 2002; Lipsitz & Goldberger, 1992; Protzner et al., 2010; Sokunbi, 2014). In this study, m was set as 2 and r was set as 0.2 since it enables a more detailed reconstruction of the joint probabilistic dynamics of the time series.

The voxel‐wise SampEn was calculated for each subject. To effectively improve normality for statistical analysis, a standardized z‐transformation of the whole‐brain SampEn map was performed to generate z‐scores map. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) with age as a covariate was performed among HPW, PPD and PPD‐A to determine the brain regions showing differences in SampEn among the three groups, the significance was determined using a cluster‐level Monte Carlo simulation corrected threshold of p < 0.05 (cluster‐forming threshold at voxel‐level p < 0.001; cluster size = 40). To further determine the between‐group differences, the mean SampEn values of the brain regions identified in ANOVA analysis were computed. Post hoc two‐sample t‐tests were performed between any pair of groups of HPW, PPD, and PPD‐A, and the significance level was set at p < 0.05 with Bonferroni correction.

2.5. Seed‐based functional connectivity analysis

Functional connectivity analysis was performed using the brain regions with differences in SampEn as seed region to further explore whether abnormal distal functional interactions between HPW, PPD, and PPD‐A. Functional connectivity (FC) was measured using Pearson's correlation coefficient and was converted to z values for statistical analysis using the Fisher z‐transform. ANOVA with age as a covariate was performed on the whole brain functional connectivity maps among HPW, PPD and PPD‐A subjects. The statistically significant differences were set using cluster‐level Monte Carlo simulation correction method with p < 0.05 (cluster‐forming threshold at voxel‐level p < 0.001; cluster size = 35). To determine between‐group differences, the mean FCs of brain areas with changed FCs were calculated for post hoc two‐sample t‐tests, the significant level was set at p < 0.05 using Bonferroni correction.

2.6. Correlation analysis

To investigate whether SampEn and FCs showing differences among HPW, PPD, and PPD‐A were associated with clinical performances, estrogen, and progesterone levels, correlation analyses were performed, and the significance level was set at p < 0.05 corrected using false discovery rate (FDR) method.

2.7. Neuroimaging‐transcriptome spatial association analysis

To identify the molecular basis of functional differences for PPD and PPD‐A, neuroimaging‐transcriptome spatial association analysis was performed. The genes expression data in this study were obtained from Allen Human Brain Atlas (AHBA) (http://www.brain-map.org) which is derived from the brains of six human autopsy donors (1 female, age range 24–57 years). The dataset includes 20,737 genes with unique Entrez IDs detected by 58,692 probes extracted from 3702 tissue samples from different sites (Arnatkeviciute et al., 2019; Hawrylycz et al., 2012). To screen the most representative probes to annotate genes, the probes showing 50% higher than background signal of brain samples in all subjects based on expression intensity were selected (Habets et al., 2023). Removing duplicate annotations and probes with low correlation with RNA‐seq data (Spearman Rho <0.2), 10,027 genes with unique Entrez IDs annotated by 10,027 probes were finally used for further analyses. Given that only two subjects in AHBA had right‐sided brain data, thus, only the left hemispheric data were analyzed in this study (Arnatkeviciute et al., 2019). For spatial association analysis, the gene expression data was projected a Schaefer brain atlas and a 500 × 10,027 expression matrix was obtained.

Because partial least squares (PLS) is technically well suited to the high degree of covariance in gene expression data, we used it to establish a correspondence between the gene expression data and the neuroimaging data to derive the genes that were most associated with changes in SampEn and FCs in PPD and PPD‐A (Farahani et al., 2010). The independent variable of PLS was the z‐score normalized gene expression matrix, and the dependent variable is the statistical t‐values of whole‐brain SampEn and FCs between any pair of the three groups. The first principal component (PLS1) was a linear combination of gene expression values with the highest correlation with the region of difference between the groups (Li et al., 2021), and we used an alignment test to test the statistical significance of PLS1 and a bootstrap test to assess the weight of genes contributing to PLS1. Standard errors were estimated using the Bootstrap method and z‐values (PLS weights divided by their standard errors) were converted to p‐values to assess the contribution of each gene to PLS1. After Bonferroni correction (p < 0.05), the set of genes that reliably contributed to PLS1 were obtained (Whitaker et al., 2016).

2.8. Enrichment analysis of associated genes

The genes most associated with the changes in SampEn and FCs were selected for functional annotation using ToppGene (https://toppgene.cchmc.org) (Chen et al., 2009). The ability to obtain annotations of 14 different aspects of gene function based on the Gene Ontology (GO) resource (http://geneontology.org) to determine biological function including molecular functions (MF), biological processes (BP) and cellular components (CC) (Gene Ontology Consortium, 2021). We also use the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) to identify biological pathways. KEGG contains mostly known metabolic pathways and regulatory pathways and can identify higher level functions of the genome (Kanehisa & Goto, 2000). The significance for gene enrichment analysis was determined using fisher's exact tests and corrected using FDR method with q < 0.05.

2.9. Protein–protein interaction (PPI) analysis

PPI analysis was performed using STRING (version 11.0, http://string-db.org) to construct a PPI network of genes associated with changes in SampEn, FCs according to a criterion of a highest confidence interaction score of 0.4, and the genes with the top 10% highest degree values in the network were identified as hub genes. Whole‐brain gene expression levels of the top five hub genes rankings by node degree were analyzed using the Neurosynth toolkit (https://neurosynth.org/).

2.10. Spatial correlation analyses for neuroimaging and neurotransmitter density maps

To identify neurotransmitters associated with PPD and PPD‐A, we performed spatial Pearson correlation analyses between statistical t‐maps of SampEn and FCs and neurotransmitter density maps. The 19 neurotransmitter receptor density maps in standard space were downloaded from this link (https://github.com/netneurolab/hansen_receptors/tree/main/data/PET_nifti_images) for analyses. Significance was determined by a spatial substitution test by transforming voxel space to the surface space of fSL32K and rotating the t‐statistic maps of SampEn and FCs 10,000 times to preserve spatial autocorrelation, yielding a distribution of spatial correlation values. Finally, the position of the true spatial correlation values in the distribution was calculated and defined as the statistical p‐value. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Clinical characteristics

Subjects' demographic and clinical data information are shown in Table 1. The three groups of subjects were well matched in age (p = 0.11), postpartum time (p = 0.9), levels of estradiol (p = 0.74), and progesterone (p = 0.96). The EPDS, BAI, BDI, PSQI, PSS in PPD and PPD‐A were significantly higher than those of HPW group. PPD‐A has significantly higher EPDS, BAI and BDI scores than PPD.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the used subjects.

| Characteristics | HPW (62) | PPD (45) | PPD‐A (31) | F value | HPW vs. PPD | HPW vs. PPD‐A | PPD vs. PPD‐A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 32.42 ± 3.92 | 31.11 ± 3.19 | 31.03 ± 3.83 | F 2,135 = 2.29 (p = 0.11) | p = 0.069 | p = 0.11 | p = 0.92 |

| Postpartum time (days) | 96.27 ± 58.86 | 94.29 ± 56.29 | 100.35 ± 53.16 | F 2,135 = 0.11 (p = 0.9) | p = 0.86 | p = 0.75 | p = 0.64 |

| Estradiol (pg/ml) | 81.23 ± 372.8 | 67.2 ± 241.09 | 32.01 ± 19.5 | F 2,135 = 0.31 (p = 0.74) | p = 0.83 | p = 0.47 | p = 0.42 |

| Progesterone (ng/ml) | 0.79 ± 1.41 | 0.85 ± 2.75 | 0.92 ± 1.67 | F 2,135 = 0.04 (p = 0.96) | p = 0.89 | p = 0.71 | p = 0.9 |

| EPDS scores | 7.06 ± 4.14 | 16.2 ± 3.22 | 18.87 ± 5.46 | F 2,135 = 104.07 (p < 0.001) | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.0092 |

| BAI scores | 30.73 ± 7.23 | 37.18 ± 5.94 | 53.71 ± 10.23 | F 2,135 = 93.83 (p < 0.001) | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

| BDI scores | 7.24 ± 5.7 | 17.4 ± 7.37 | 24.26 ± 9.7 | F 2,135 = 61.8 (p < 0.001) | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.001 |

| PSQI scores | 6.85 ± 3.41 | 9.29 ± 3.46 | 10.71 ± 3.85 | F 2,135 = 13.94 (p < 0.001) | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.097 |

| PSS scores | 15.5 ± 4.8 | 19.62 ± 4.9 | 20.68 ± 3.92 | F 2,136 = 16.83 (p < 0.001) | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.3 |

Note: One‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was first used to identify differences in demographics and clinical characteristics. Post‐hoc two‐sample t‐tests were further used to determine the between group differences in all the clinical performances. A Pearson chi‐squared test was used for gender comparison.

Abbreviations: BAI, Beck's anxiety inventory; BDI, Beck's depression inventory; EPDS, Edinburgh postnatal depression scale; HPW, healthy postnatal women; PSQI, Pittsburgh sleep quality index; PSS, perceived stress scale; PPD, postpartum depression; PPD‐A, postpartum depression with anxiety.

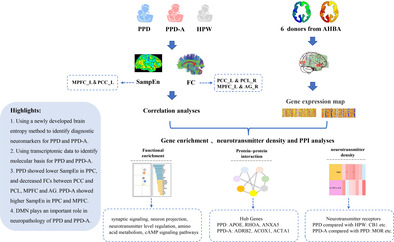

3.2. SampEn differences among HPW, PPD, and PPD‐A

ANOVA identified significant difference in SampEn maps among HPW, PPD and PPD‐A groups located in left medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC_L) and left posterior cingulate cortex (PCC_L, Table 2 and Figure 1). The post‐hoc two‐sample t‐tests found that PPD‐A shows significantly higher SampEn in PCC_L than both PPD and HPW while there is no significant difference between PPD and HPW. PPD‐A also shows significantly higher SampEn in MPFC_L than HPW and PPD, and PPD shows lower SampEn in MPFC_L than HPW.

TABLE 2.

Differences in sample entropy (SampEn) and functional connectivity (FC) between HPW, PPD, and PPD‐A groups.

| Indices | Brain regions | L/R | Peak MNI coordinates | F values | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | Z | |||||

| SampEn | Medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) | L | −6 | 51 | 3 | 13.87 | p < 0.001 |

| Posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) | L | −3 | −54 | 24 | 11.3 | p < 0.001 | |

| FC: MPFC | Angular gyrus | R | 45 | −63 | 51 | 7.99 | p = 0.001 |

| FC: PCC | Paracentral lobule | R | 9 | −27 | 54 | 12.03 | p < 0.001 |

Note: The one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to identify differences in SampEn values and FCs among the three groups.

Abbreviations: L, left hemisphere; R, right hemisphere.

FIGURE 1.

Differences in brain sample entropy (SampEn) between postpartum depression (PPD), PPD with anxiety (PPD‐A) and healthy postnatal women (HPW). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) of SampEn maps (with age as covariate) showed significant differences in left medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC_L) and left posterior cingulate cortex (PCC_L) in HPW, PPD and PPD‐A. Post‐hoc two‐sample t‐tests of SampEn in MPFC_L and PCC_L between any pair of HPW, PPD, and PPD‐A were further performed to identify between group differences.

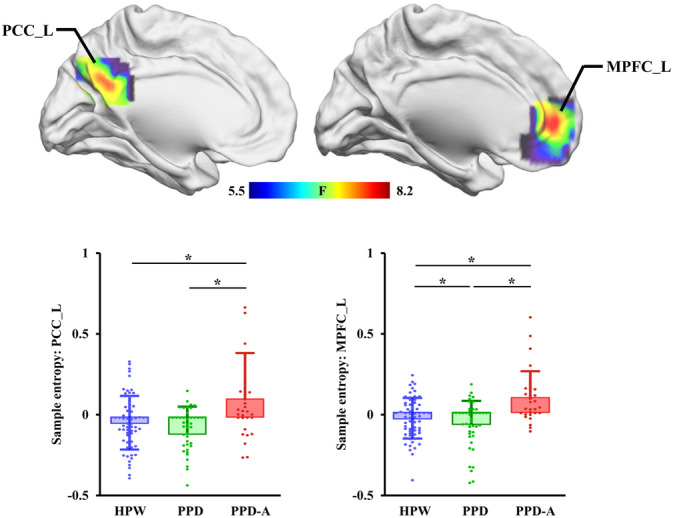

3.3. Functional connectivity differences of MPFC and PCC

Using MPFC_L and PCC_L as seed area, whole‐brain functional connectivity analysis identified significant differences in FCs between MPFC_L and right angular gyrus (AG_R) and between PCC_L and right paracentral lobule (PCL_R). PPD shows significantly decreased FCs between MPFC_L and AG_R and between PCC_L and PCL_R compared to both HPW and PPD‐A, but there are no significant difference between HPW and PPD‐A (Table 2 and Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Differences in functional connectivities (FCs) of left MPFC and PCC among HPW, PPD, and PPD‐A. One‐way ANOVA found altered FCs between MPFC_L and right angular gyrus (AG_R) and between PCC_L and right paracentral lobule (PCL_R) among HPW, PPD, and PPD‐A. Post‐hoc two‐sample t‐tests revealed significantly decreased FCs between PCC_L and PCL_R and between MPFC_L and AG_R in PPD compared to both HPW and PPD‐A. There are no significant differences in FCs between HPW and PPD‐A.

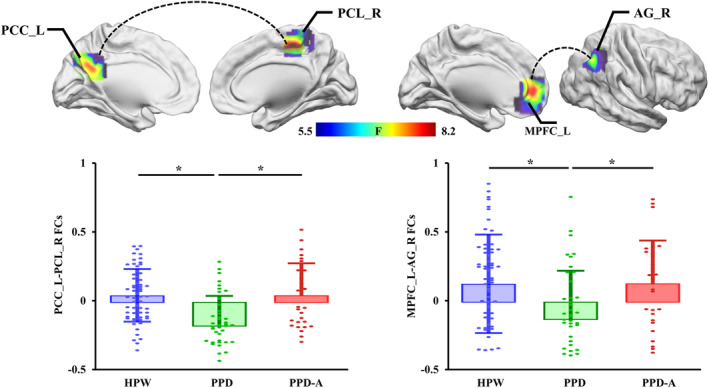

3.4. Correlation analyses

In PPD group, the SampEn in PCC_L was significantly negatively correlated with estrogen level (r = −0.56, p = 1 × 10−4) (Figure 3). We also found that FCs of PCC_L with PCL‐R were negatively correlated with PSS scores in the PDD group (r = −0.33, p = 0.036), and FCs of MPFC_L with AG‐R were positively correlated with PSS scores in the PDD‐A group (r = 0.37, p = 0.047) before multiple comparisons correction (Figure S1).

FIGURE 3.

Correlation analysis results. The SampEn of PCC_L was significantly negatively correlated with estrogen level in patients with PPD not in subjects with HPW.

3.5. Gene enrichment and PPI analyses

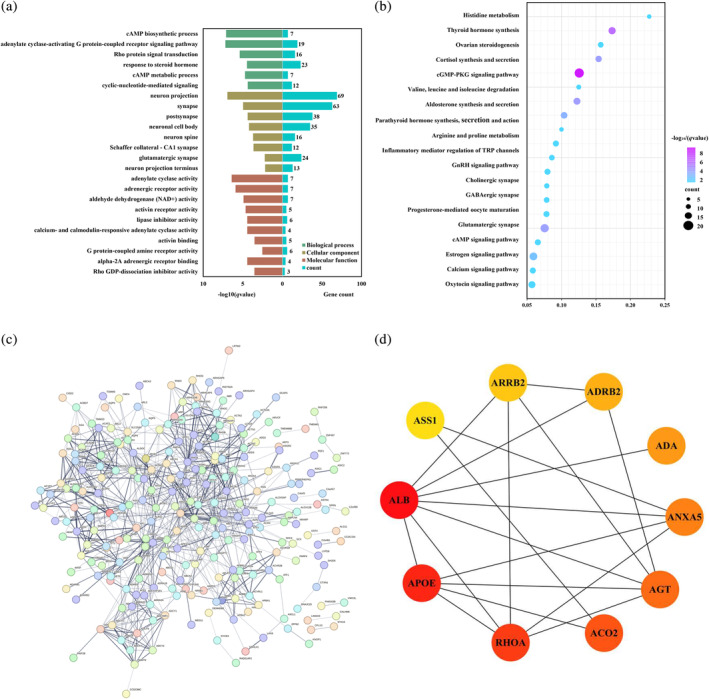

The associated genes with the changes of FCs (MPFC_L or PPC_L as seed areas) between PPD and HPW and between PPD‐A and HPW were identified, respectively. The overlapped genes found between PPD versus HPW and PPD‐A versus HPW was taken as the MPFC_L or PCC_L related FCs changes associated genes for PPD (Figures S2 and S3). In addition, the overlapped genes for FC changes of MPFC_L and PCC_L as seeds areas were further analyzed and 446 overlapped genes finally kept as the basic functional connectivity changes associated genes for PPD. GO analysis for the 446 genes revealed that these genes were mainly enriched in synaptic signaling, response to hormones, energy metabolism, and modulation of neuronal actions (Figure 4a). The KEGG analysis for the 446 genes found that these genes were mainly enriched in cAMP signaling pathway, neurotransmitterergic synapses, amino acid metabolism, inflammatory signaling pathway, and endocrine hormone signaling pathway (Figure 4b). By PPI analysis, we constructed a statistically significant PPI network for the 446 genes (p = 1.0 × 10−16) (Figure 4c). The top 10 hub genes with the highest degree values in the PPI network were shown (Figure 4d).

FIGURE 4.

Gene enrichment analysis and the corresponding PPI network of the genes for PPD derived from spatial association analyses between transcriptome and changes of FCs. (a) Triplicate histograms were plotted for GO enrichment analysis of biological processes (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular functions (MF). All the results were obtained with p < 0.05 (BH‐FDR correction). (b) Bubble plot was used to show the KEGG enrichment analysis results obtained with p < 0.05 (BH‐FDR correction). (c) A PPI network was constructed using significantly associated genes with changes of FCs. (d) The top 10 hub genes of the PPI network were shown and different colors represent the size of degree (The dark red represents higher degree values and the yellow represent lower degree values).

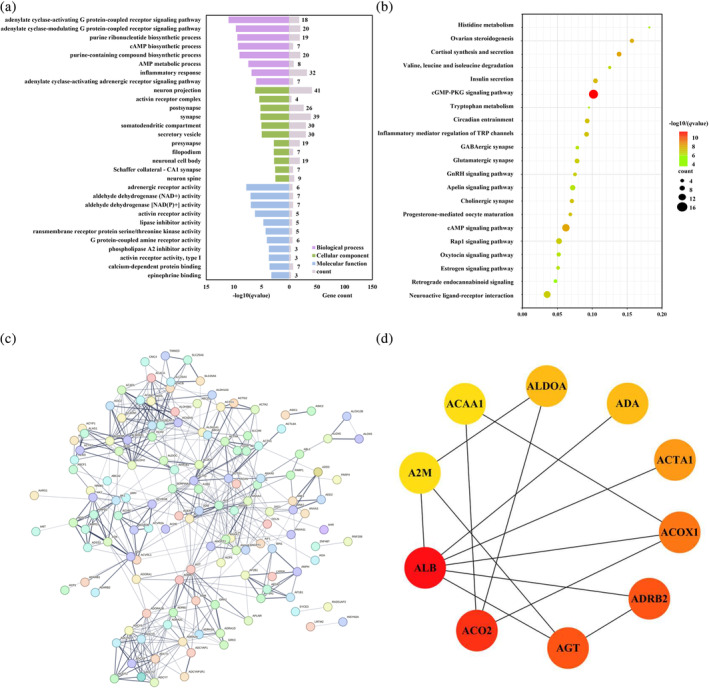

In addition, we found 231 genes significantly associated with changes in SampEn between PPD and PPD‐A. GO analysis revealed that these genes were mainly enriched in cell signaling responses, modulation of neuronal and synaptic actions, and adrenergic receptor activity (Figure 5a). In KEGG analysis, these genes were mainly enriched in cAMP signaling pathway, neurotransmitterergic synapses, inflammatory pathways, neuroactive ligand‐receptor interactions, and endocrine hormone signaling pathways (Figure 5b). By PPI analysis, we constructed a statistically significant PPI network (p = 1.0 × 10−16) (Figure 5c), and the top 10 hub genes with the highest degree values in the PPI network were shown (Figure 5d).

FIGURE 5.

Gene enrichment analysis of the genes associated with sample entropy (SampEn) differences between PPD and PPD‐A groups and corresponding protein–protein interaction (PPI) network. (a) Triplicate histograms were plotted for GO enrichment analysis of biological processes (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular functions (MF). All the results were obtained with p < 0.05 (BH‐FDR correction). (b) Bubble plot was used to show the KEGG enrichment analysis results obtained with p < 0.05 (BH‐FDR correction). (c) A PPI network was constructed with the significantly associated genes for the changes of SampEn between PPD and PPD‐A. (d) The top 10 hub genes of the PPI network were shown and different colors represent the size of degree (the dark red represents higher degree values and the yellow represent lower degree values).

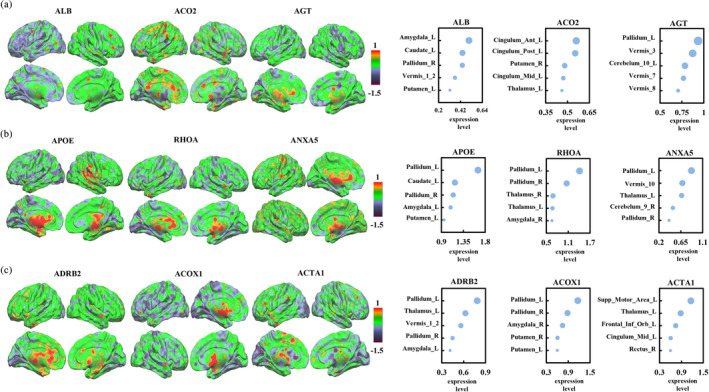

In addition, the expression levels of the top three hub genes (ALB, ACO2, AGT) between PPD and PPD‐A in the whole brain and in the top five brain areas were shown. These hub genes with the highest expression levels in amygdala, cingulate gyrus, striatum, thalamus and cerebellum were observed (Figure 6a). The top three hub genes of APOE, RHOA, and ANXA5 specific for PPD had the highest levels of expression in the striatum, amygdala, thalamus and cerebellum (Figure 6b); and the top three hub genes of ADRB2, ACOX1, and ACTA1 specific for PPD‐A had the highest levels of expression in the striatum, supplementary motor area, thalamus, amygdala, the orbital part of inferior frontal cortex, cingulate cortex, cerebellum and rectus (Figure 6c).

FIGURE 6.

The expression levels of top three hub genes in the whole brain and in the top five brain areas. (a) The expression levels of the top three overlapped hub genes between PPD and PPD‐A in whole brain and the top five brain areas were shown. (b) The expression levels of the top three hub genes specific for PPD in whole brain and the top five brain areas were shown. (c) The expression levels of the top three hub genes specific for PPD‐A in whole brain and the top five brain areas were exhibited.

3.6. PPD and PPD‐A related neurotransmitter receptors

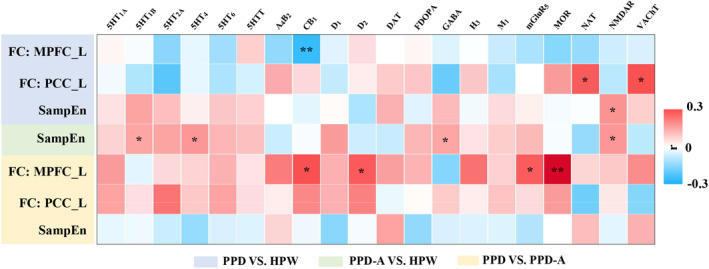

Neurotransmitter receptor distribution‐neuroimaging spatial correlation analyses found that the changes of FC with MPFC_L as seed area between PPD and HPW were negatively correlated with CB1 (r = −0.24, p = 0.004); the changes of FC with PCC_L as seed area between PPD and HPW was positively correlated with NAT (r = 0.26, p = 0.006) and VAChT (r = 0.27, p = 0.014); the changes of SampEn between PPD and HPW were positively correlated with NMDAR (r = 0.17, p = 0.03). For PPD‐A compared with HPW, the changes in SampEn were positively correlated with 5HT1B (r = 0.14, p = 0.033), 5HT4 (r = 0.16, p = 0.019), GABA (r = 0.14, p = 0.043), and NMDAR (r = 0.16, p = 0.014). For PPD‐A compared with PPD, the changes of FC with MPFC_L as seed area were positively correlated with CB1 (r = 0.27, p = 0.02), D2 (r = 0.26, p = 0.031), mGluR5 (r = 0.25, p = 0.015), and MOR (r = 0.38, p = 0.011) (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

PPD and PPD‐A related neurotransmitter receptors. Spatial Pearson correlation analyses between statistical t maps of SampEn and FCs and neurotransmitter density maps have identified PPD and PPD‐A‐related neurotransmitter receptors. The significant level was set at p < 0.05.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, combining brain sample entropy, functional connectivity and neuroimaging‐transcriptome/neurotransmitter spatial association analyses, we revealed abnormal sample entropy and functional couplings of DMN in PPD and PPD‐A. Moreover, we linked these functional changes with trancriptomic expression level and neurotransmitter density. We found that the functional abnormalities in PPD or PPD‐A are associated with synaptic signaling, neuron projection, neurotransmitter level regulation, ion transmembrane transport, cAMP signaling pathways and neurotransmitters of 5‐HT, norepinephrine, glutamate and dopamine etc. Our findings highlight the important role of DMN in neuropathology of PPD and PPD‐A and identify the molecular basis for functional changes in PPD and PPD‐A for the first time.

4.1. DMN in PPD and PPD‐A

Both MPFC and PCC which are core areas of DMN are involved in emotion regulation and various cognitive functions (Drevets et al., 2008; Payne & Maguire, 2019; Zheng et al., 2018) and are also key brain regions in PPD and postpartum anxiety (Chase et al., 2014; Sabihi et al., 2021). The DMN has been shown to be involved in regulating depression and anxiety levels (Payne & Maguire, 2019; Tao et al., 2015). Compared with HPW and PPD, we found that the SampEn of left PCC specifically increased in PPD‐A. PCC is the posterior core region of the DMN and plays an important role in self‐reflection (Chase et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2018). Compared with depression, many studies emphasize the key role of PCC in anxiety because PCC shows relatively high activities to think about responsibilities and obligations. For example, it has been found that neuroticism scores are associated with PCC activity and is positively correlated with anxiety symptoms (Roelofs et al., 2008). Orchard et al. found that a decrease in the inhibitory effects of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex on PCC may cause excessive maternal worry to induce postnatal anxiety (Orchard et al., 2023). We found the specifically elevated SampEn of PCC suggesting increased irregularity of the brain system caused by elevated levels of fear and reduced levels of well‐being in patients with PPD‐A. The elevated SampEn of PCC may be specific for anxiety symptoms and may serve as a biomarker to identify PPD‐A.

Compared to HPW, the SampEn of MPFC increased in PPD‐A while decreased in PPD. The MPFC is the anterior core of the DMN and acts as a control panel for cognitive processes as well as emotion regulation (Drevets et al., 2008; Miller & Cohen, 2001). The functional disruption of MPFC plays a key role in the development of both PPD and postpartum anxiety disorder (Sabihi et al., 2021). Structural plasticity and altered neuronal activity in the MPFC are closely associated with emotional and cognitive deficits in PPD (Leuner et al., 2014; Leuner et al., 2023). Patients with PPD were found to have decreased spontaneous neural activity in the prefrontal cortex and to exhibit impaired cognitive function (Zheng et al., 2018). These findings indicated that depression is an adaptive behavior of a person to reduce the uncertainty in life by reducing the entropy of sensory and physical states (Badcock et al., 2017). It has been found that the neuropeptide oxytocin in the prelimbic region of the MPFC modulates maternal anxiety‐like behavior (Sabihi et al., 2014). The higher anxiety sensitivity of healthy adults with negative childhood experiences showed higher MPFC entropy (Duncan et al., 2015). Depression is a state of neuronal hypoactivity while anxiety is a state of neuronal excitation. The presence of both states indicates increased brain irregularity in patients PPD‐A. Using SampEn analysis, we provide new evidence for irregular activity of MPFC in patients with PPD and PPD‐A, and SampEn of MPFC can be used as a marker to distinguish PPD and PPD‐A.

Decreased FCs between PCC and PCL as well as between MPFC and AG were found in patients with PPD Compared with HPW and PPD‐A. The PCL is a part of the somatosensory network, and the reduced FC with PCC may be related to impaired ability to process autosensory leading to reduced sensitivity to various somatosensory stimuli. This conclusion is supported by a previous study which found reduced somatosensory cortical activation in patients with PPD leading to reduced sensitivity of patients to neonatal pain manifestations (Bembich et al., 2016). The negative correlation of FC between PCC and PCL with PSS scores found in our study suggests that the FC between PCC and PCL directly regulated the mental stress in PPD. MPFC and AG are two important components of DMN and patients with PPD showed reduced voxel‐mirrored homotopic connectivity of MPFC (Zhang et al., 2022). The AG is involved in attention, emotion, memory and semantic processing (Liu et al., 2012; Wang, Xie, et al., 2017). The reduced FC between MPFC and AG may be related to self‐reference dysfunction, impaired attention and memory capacity in PPD patients. Moreover, we found that SampEn of PCC was negatively correlated with blood estrogen levels in PPD patients indicating the functional irregularity of PCC in PPD was mediated by estrogen level. Our findings were supported by the previous studies which found that the biological mechanism of PPD is estrogen fluctuations through the estrogen signaling pathway and estrogen receptor α was negatively correlated with gray matter volume of PCC (McEvoy et al., 2017; Tan et al., 2020). All these findings highlight the important role of PCC and MPFC in the neuropathology of PPD.

4.2. Molecular basis for PPD and PPD‐A

We constructed two PPI networks with hub genes screened from genes associated with altered brain entropy and functional connectivity. These genes are mainly involved in the regulation of nutrient metabolism and protein expression at the synapse in PPD and PPD‐A. For PPD‐A, some of the central genes are closely associated with the development of anxiety symptoms, and they have functional implications for understanding the molecular pathogenesis and treatment of PPD‐A. For example, ADRB2 encodes the adrenergic receptor β2 which has been shown to reduce β‐adrenergic signaling in patients with postpartum anxiety (Nicoloro‐SantaBarbara et al., 2022). ACOX1 can contribute to the development of anxiety by affecting the level of ω‐3 LC‐polyunsaturated fatty acid synthesis (Aliev et al., 2022). In the case of PPD, high expression of several pivotal genes has been shown to be a risk factor for PPD. For example, the RhoA signaling pathway plays a key role in PPD by participating in the process of glutamatergic synaptic stress and the release of AMPA receptors to dendritic spines (Gerges et al., 2004; Olivier et al., 2015). ANXA5 is a Ca2+‐dependent membrane and phospholipid‐binding protein, and Ca2+ promotes the synthesis of 5‐HT, thereby playing an important role in preventing the development of PPD (Freiría‐Martínez et al., 2023; Robinson et al., 2014).

Compared with PPD, genes associated with altered brain function in PPD‐A are predominantly enriched in biological pathways associated with anxiety‐like symptoms, including modulation of neuronal and synaptic actions, lipid metabolism, neuroactive ligand‐receptor interactions, and inflammatory pathways. For example, Ageta et al. find that activin in the forebrain bi‐directionally affects anxiety‐related behaviors (Ageta et al., 2008). Monoacylglycerol lipase inhibitors significantly increase basal corticosterone levels causing anxiety‐like symptoms (Aliczki et al., 2013). Conditional ablation of the neural cell adhesion molecule L1 results in increased basal excitatory synaptic transmission and decreased anxiety in mice with CA1 (Law et al., 2003). Excess purine produced by T cells can over‐activate neurons in the amygdala leading to anxiety symptoms (Fan et al., 2019). We found that the distribution of the neurotransmitter of MOR which elicits anxiety‐like behaviors by altering interactions between the brain's opioid and GABA systems, is also important for anxiety symptoms (Kalinichev et al., 2000). The neurotransmitter of mGluR5 is one of the most important receptors of the central glutamatergic system, and anxiety symptoms exhibited by offspring rats exposed prenatally and postnatally to a high‐calorie diet are associated with overexpression of glutamate receptor mRNA in the prefrontal cortex (Rivera et al., 2020). Postpartum mothers separated from their infants show anxiety‐like behaviors and a tendency toward high expression of dopamine receptor D2 (Noori et al., 2020). Our study also found that PPD‐A is associated with the neurotransmitters of 5‐HT and GABA, which is consistent with previous findings that symptoms of depression and anxiety in PPD mouse model are associated with differential expression of GABA receptor subunits and a significant increase in 5‐HT in the hypothalamus (Avraham et al., 2017; Tarantino et al., 2011). Genes associated with altered brain function in PPD were mainly enriched in response to hormones, neuronal projections, and cAMP signaling pathways, which are associated with depressive symptoms. For example, PAŘÍZEK et al. found that changes in steroid hormone levels in the 4 weeks before delivery were associated with PPD (Pařízek et al., 2014). The hair cortisol levels during pregnancy can predict depressive symptoms in PPD (Romero‐Gonzalez et al., 2019). The neurotransmitters of CB1 and VAChT belong to dopamine and acetylcholine systems, respectively. Activation of the CB1 receptor and inhibition of VAChT could reduce dopamine release and cause PPD (Anderson & Maes, 2013; Busquets‐Garcia et al., 2018). The neurotransmitter of NMDAR is associated with neuroplasticity and mediates learning and memory functions (Dupuis et al., 2023). The use of a noncompetitive NMDAR antagonist show rapid and sustained antidepressant effects in a rodent model of postpartum depression (Feng et al., 2024). In addition, the neurotransmitter of NAT which belongs to the noradrenergic system was also found in our study. A previous study has reported that postnatal dysregulation of the metabolism of norepinephrine causes PPD (Ma et al., 2019). Taken together, we found that the occurrences of PPD are not only associated abnormal gene expression profiles but also are regulated by multiple neurotransmitters.

It should be noted that our study has several limitations. First, it is possible that the differences between PPD and PPD‐A are due to their confounding factors including the modes of conception and delivery and differences in the mothers' own cognitive abilities, thus further refinement of the study design is needed; Second, we only conducted a cross‐sectional research of PPD and PPD‐A patients in this study. A longitudinal study from preconception, prenatal to postnatal period is desired, which may delineate the dynamic mechanisms of PPD and PPD‐A. Third, the gene expression data came from six postmortem brains not from the same subjects as the neuroimaging data, which may result in the results bias. In addition, the transcriptomic data only include six subjects and only one female subject enrolled. The small samples and skewed gender distribution may also influence the spatial correlation analyses results. Fourth, in our study, we found that some of the PPD‐A subjects have higher BDI scores than PPD, which suggest that the PPD‐A sample does not just have co‐morbid anxiety but also with severe depression. Although PPD‐A has higher BDI scores than PPD, we found the inconsistency that some PPD or PPD‐A subjects with higher EPDS but with lower BDI and vice versa indicating that PPD and general depression may share similar but different brain circuits (Cheng, Guo, et al., 2022). In spite of this inconsistency, our study still cannot rule out the effects of this confound factor, which is indeed a limitation of our study. The future studies need to pay more attention during screening samples to ensure that the selected samples have same conditions to exclude other confound factors.

5. CONCLUSIONS

By combining brain entropy, functional connectivity, transcriptomic and neurotransmitter data, we found that the functional irregularity of DMN and functional connectivities within DMN could serve as effective neuromarkers to distinguish PPD and PPD‐A. Furthermore, the functional changes in PPD and PPD‐A are closely associated with synaptic signaling, neuron projection, neurotransmitter receptor and transmembrane transporter activity, which indicates that long‐term postpartum depression or anxiety results in synaptic plasticity and neurotransmitter changes. These synaptic and molecular alterations may be the underlying neuropathological basis of PPD and PPD‐A.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62176044); Natural Science Foundation of Yunnan Province (202102AA100053) and Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (202201BE070001‐004); National Natural Science Foundation of China (31920103009), the Major Project of National Social Science Foundation (20&ZD153); Shenzhen‐Hong Kong Institute of Brain Science—Shenzhen Fundamental Research Institutions (2022SHIBS0003); Kunming University of Science and Technology & The second people's hospital of Yuxi Joint Special Project on Medical Research (KUST‐YX2022001; KUST‐YX2022003); Kunming University of Science and Technology & People's hospital of Lijiang Joint Special Project on Medical Research (KUST‐LJ2022002Y).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

FIGURE S1. Correlations between FCs and PSS scores. The FC of PCC_L‐PCL_R were negatively correlated with PSS scores before correction for multiple comparisons in the PDD group. The FC of MPFC_L‐AG_R were positively correlated with PSS scores in the PDD‐A group.

FIGURE S2. Gene enrichment analysis and the corresponding PPI network of the set of genes resolving PPDs obtained from changes in FCs of MPFC_L‐AG_R. (a) Triplicate histograms were plotted for GO enrichment analysis of biological processes (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular functions (MF). All the results were obtained with p < 0.05 (BH‐FDR correction). (b) Bubble plot was used to show the KEGG enrichment analysis results obtained with p < 0.05 (BH‐FDR correction). (c) A PPI network was constructed using significantly associated genes with changes of FCs. (d) The top 10 hub genes of the PPI network were shown and different colors represent the size of degree (The dark red represents higher degree values and the yellow represent lower degree values).

FIGURE S3. Gene enrichment analysis and the corresponding PPI network of the set of genes resolving PPDs obtained from changes in FCs of PCC_L‐PCL_R. (a) Triplicate histograms were plotted for GO enrichment analysis of biological processes (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular functions (MF). All the results were obtained with p < 0.05 (BH‐FDR correction). (b) Bubble plot was used to show the KEGG enrichment analysis results obtained with p < 0.05 (BH‐FDR correction). (c) A PPI network was constructed using significantly associated genes with changes of FCs. (d) The top 10 hub genes of the PPI network were shown and different colors represent the size of degree (The dark red represents higher degree values and the yellow represent lower degree values).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors also would like to thank Dr Qiang Yao and Aiyun Xing, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, West China Second Hospital, Chengdu, for their instruction and assistance with patients enrollment.

Chen, K. , Yang, J. , Li, F. , Chen, J. , Chen, M. , Shao, H. , He, C. , Cai, D. , Zhang, X. , Wang, L. , Luo, Y. , Cheng, B. , & Wang, J. (2024). Molecular basis underlying default mode network functional abnormalities in postpartum depression with and without anxiety. Human Brain Mapping, 45(5), e26657. 10.1002/hbm.26657

Contributor Information

Yuejia Luo, Email: luoyj@bnu.edu.cn.

Bochao Cheng, Email: wonder9527@163.com.

Jiaojian Wang, Email: jiaojianwang@uestc.edu.cn.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data and code used for data analysis are available upon request.

REFERENCES

- Abásolo, D. , Hornero, R. , Espino, P. , Alvarez, D. , & Poza, J. (2006). Entropy analysis of the EEG background activity in Alzheimer's disease patients. Physiological Measurement, 27, 241–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ageta, H. , Murayama, A. , Migishima, R. , Kida, S. , Tsuchida, K. , Yokoyama, M. , & Inokuchi, K. (2008). Activin in the brain modulates anxiety‐related behavior and adult neurogenesis. PLoS One, 3, e1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliczki, M. , Zelena, D. , Mikics, É. , Varga, Z. K. , Pintér, O. , Bakos, N. , Varga, J. , & Haller, J. (2013). Monoacylglycerol lipase inhibition‐induced changes in plasma corticosterone levels, anxiety and locomotor activity in male CD1 mice. Hormones and Behavior, 63, 752–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliev, F. , Barr, P. B. , Davies, A. G. , Dick, D. M. , & Bettinger, J. C. (2022). Genes regulating levels of ω‐3 long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acids are associated with alcohol use disorder and consumption, and broader externalizing behavior in humans. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 46, 1657–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmann, A. , Cash, D. M. , Bocchetta, M. , Heller, C. , Reynolds, R. , Moore, K. , Convery, R. S. , Thomas, D. L. , van Swieten, J. C. , Moreno, F. , Sanchez‐Valle, R. , Borroni, B. , Laforce, R., Jr. , Masellis, M. , Tartaglia, M. C. , Graff, C. , Galimberti, D. , Rowe, J. B. , Finger, E. , … Rohrer, J. D. (2020). Analysis of brain atrophy and local gene expression in genetic frontotemporal dementia. Brain Communications, 2, fcaa122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, G. , & Maes, M. (2013). Postpartum depression: Psychoneuroimmunological underpinnings and treatment. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 9, 277–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, K. M. , Collins, M. A. , Kong, R. , Fang, K. , Li, J. , He, T. , Chekroud, A. M. , Yeo, B. T. T. , & Holmes, A. J. (2020). Convergent molecular, cellular, and cortical neuroimaging signatures of major depressive disorder. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117, 25138–25149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnatkeviciute, A. , Fulcher, B. D. , & Fornito, A. (2019). A practical guide to linking brain‐wide gene expression and neuroimaging data. NeuroImage, 189, 353–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avraham, Y. , Hants, Y. , Vorobeiv, L. , Staum, M. , Abu Ahmad, W. , Mankuta, D. , Galun, E. , & Arbel‐Alon, S. (2017). Brain neurotransmitters in an animal model with postpartum depressive‐like behavior. Behavioural Brain Research, 326, 307–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badcock, P. B. , Davey, C. G. , Whittle, S. , Allen, N. B. , & Friston, K. J. (2017). The depressed brain: An evolutionary systems theory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21, 182–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Başar, E. (2011). Brain‐body‐mind in the nebulous Cartesian system: A holistic approach by oscillations. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A. T. , Epstein, N. , Brown, G. , & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 893–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A. T. , Ward, C. H. , Mendelson, M. , Mock, J. , & Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4, 561–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bembich, S. , Vecchiet, C. , Cont, G. , Sustersic, C. , Valencak, F. , & Demarini, S. (2016). Maternal cortical response to baby pain and postpartum depressive symptoms. Biological Psychology, 121, 12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo, W. V. , & Yawn, B. P. (2014). Concise review for physicians and other clinicians: Postpartum depression. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 89, 835–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busquets‐Garcia, A. , Bains, J. , & Marsicano, G. (2018). CB1 receptor signaling in the brain: Extracting specificity from ubiquity. Neuropsychopharmacology, 43, 4–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse, D. J. , Reynolds, C. F., 3rd , Monk, T. H. , Berman, S. R. , & Kupfer, D. J. (1989). The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28, 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase, H. W. , Moses‐Kolko, E. L. , Zevallos, C. , Wisner, K. L. , & Phillips, M. L. (2014). Disrupted posterior cingulate‐amygdala connectivity in postpartum depressed women as measured with resting BOLD fMRI. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9, 1069–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. , Bardes, E. E. , Aronow, B. J. , & Jegga, A. G. (2009). ToppGene suite for gene list enrichment analysis and candidate gene prioritization. Nucleic Acids Research, 37, W305–W311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. , Zhang, C. , Wang, R. , Jiang, P. , Cai, H. , Zhao, W. , Zhu, J. , & Yu, Y. (2022). Molecular basis underlying functional connectivity of fusiform gyrus subregions: A transcriptome‐neuroimaging spatial correlation study. Cortex: A Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior, 152, 59–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, B. , Guo, Y. , Chen, X. , Lv, B. , Liao, Y. , Qu, H. , Hu, X. , Yang, H. , Meng, Y. , Deng, W. , & Wang, J. (2022). Postpartum depression and major depressive disorder: The same or not? Evidence from resting‐state functional MRI. Psychoradiology, 2, 121–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, B. , Hu, X. , Roberts, N. , Zhao, Y. , Xu, X. , Zhou, Y. , Tan, X. , Chen, S. , Meng, Y. , Wang, S. , Xing, H. , & Deng, W. (2022). Prolactin mediates the relationship between regional gray matter volume and postpartum depression symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders, 301, 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In Spacapan S. & Oskamp S. (Eds.), The social psychology of health (pp. 31–67). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M. , Goldberger, A. L. , & Peng, C. K. (2002). Multiscale entropy analysis of complex physiologic time series. Physical Review Letters, 89, 068102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J. L. , Holden, J. M. , & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10‐item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 150, 782–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets, W. C. , Price, J. L. , & Furey, M. L. (2008). Brain structural and functional abnormalities in mood disorders: Implications for neurocircuitry models of depression. Brain Structure & Function, 213, 93–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, N. W. , Hayes, D. J. , Wiebking, C. , Tiret, B. , Pietruska, K. , Chen, D. Q. , Rainville, P. , Marjańska, M. , Ayad, O. , Doyon, J. , Hodaie, M. , & Northoff, G. (2015). Negative childhood experiences alter a prefrontal‐insular‐motor cortical network in healthy adults: A preliminary multimodal rsfMRI‐fMRI‐MRS‐dMRI study. Human Brain Mapping, 36, 4622–4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis, J. P. , Nicole, O. , & Groc, L. (2023). NMDA receptor functions in health and disease: Old actor, new dimensions. Neuron, 111, 2312–2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falah‐Hassani, K. , Shiri, R. , & Dennis, C. L. (2016). Prevalence and risk factors for comorbid postpartum depressive symptomatology and anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders, 198, 142–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan, K. Q. , Li, Y. Y. , Wang, H. L. , Mao, X. T. , Guo, J. X. , Wang, F. , Huang, L. J. , Li, Y. N. , Ma, X. Y. , Gao, Z. J. , Chen, W. , Qian, D. D. , Xue, W. J. , Cao, Q. , Zhang, L. , Shen, L. , Zhang, L. , Tong, C. , Zhong, J. Y. , … Jin, J. (2019). Stress‐induced metabolic disorder in peripheral CD4(+) T cells leads to anxiety‐like behavior. Cell, 179, 864–879.e819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farahani, H. A. , Rahiminezhad, A. , Same, L. , & Immannezhad, K. (2010). A comparison of partial least squares (PLS) and ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions in predicting of couples mental health based on their communicational patterns. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 1459–1463. [Google Scholar]

- Farr, S. L. , Dietz, P. M. , O'Hara, M. W. , Burley, K. , & Ko, J. Y. (2014). Postpartum anxiety and comorbid depression in a population‐based sample of women. Journal of Women's Health, 2002(23), 120–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y. F. , Zhou, Y. Y. , & Duan, K. M. (2024). The role of Extrasynaptic GABA receptors in postpartum depression. Molecular Neurobiology, 61, 385–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forty, L. , Jones, L. , Macgregor, S. , Caesar, S. , Cooper, C. , Hough, A. , Dean, L. , Dave, S. , Farmer, A. , McGuffin, P. , Brewster, S. , Craddock, N. , & Jones, I. (2006). Familiality of postpartum depression in unipolar disorder: Results of a family study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 1549–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiría‐Martínez, L. , Iglesias‐Martínez‐Almeida, M. , Rodríguez‐Jamardo, C. , Rivera‐Baltanás, T. , Comís‐Tuche, M. , Rodrígues‐Amorím, D. , Fernández‐Palleiro, P. , Blanco‐Formoso, M. , Álvarez‐Chaver, P. , Diz‐Chaves, Y. , Gonzalez‐Freiria, N. , Martín‐Forero‐Maestre, M. , Fernández‐Feijoo, C. D. , Suárez‐Albo, M. , Fernández‐Lorenzo, J. R. , Guisán, A. C. , Olivares, J. M. , & Spuch, C. (2023). Proteomic analysis of exosomes derived from human mature milk and colostrum of mothers with term, late preterm, or very preterm delivery. Analytical Methods, 15, 4905–4917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gene Ontology Consortium . (2021). The gene ontology resource: Enriching a GOld mine. Nucleic Acids Research, 49, D325–d334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerges, N. Z. , Backos, D. S. , & Esteban, J. A. (2004). Local control of AMPA receptor trafficking at the postsynaptic terminal by a small GTPase of the Rab family. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 279, 43870–43878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, J. H. (2004). Paternal postpartum depression, its relationship to maternal postpartum depression, and implications for family health. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 45, 26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habets, P. C. , Kalafatakis, K. , Dzyubachyk, O. , van der Werff, S. J. A. , Keo, A. , Thakrar, J. , Mahfouz, A. , Pereira, A. M. , Russell, G. M. , Lightman, S. L. , & Meijer, O. C. (2023). Transcriptional and cell type profiles of cortical brain regions showing ultradian cortisol rhythm dependent responses to emotional face stimulation. Neurobiology of Stress, 22, 100514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, X. , Cao, M. , He, J. , Xu, D. , Liang, Y. , Lang, X. , & Guan, R. (2023). A comprehensive psychological tendency prediction model for pregnant women based on questionnaires. Scientific Reports, 13, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, J. A.‐O. , Shafiei, G. A.‐O. , Markello, R. A.‐O. , Smart, K. A.‐O. , Cox, S. M. L. , Nørgaard, M. A.‐O. , Beliveau, V. A.‐O. X. , Wu, Y. , Gallezot, J. D. , Aumont, É. , Servaes, S. , Scala, S. G. , DuBois, J. M. , Wainstein, G. A.‐O. , Bezgin, G. , Funck, T. , Schmitz, T. A.‐O. , Spreng, R. A.‐O. , Galovic, M. , … Misic, B. A.‐O. (2022). Mapping neurotransmitter systems to the structural and functional organization of the human neocortex. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hawrylycz, M. J. , Lein, E. S. , Guillozet‐Bongaarts, A. L. , Shen, E. H. , Ng, L. , Miller, J. A. , van de Lagemaat, L. N. , Smith, K. A. , Ebbert, A. , Riley, Z. L. , Abajian, C. , Beckmann, C. F. , Bernard, A. , Bertagnolli, D. , Boe, A. F. , Cartagena, P. M. , Chakravarty, M. M. , Chapin, M. , Chong, J. , … Jones, A. R. (2012). An anatomically comprehensive atlas of the adult human brain transcriptome. Nature, 489, 391–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick, V. , Altshuler, L. , Strouse, T. , & Grosser, S. (2000). Postpartum and nonpostpartum depression: Differences in presentation and response to pharmacologic treatment. Depression and Anxiety, 11, 66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinichev, M. , Easterling, K. W. , & Holtzman, S. G. (2000). Periodic postpartum separation from the offspring results in long‐lasting changes in anxiety‐related behaviors and sensitivity to morphine in Long‐Evans mother rats. Psychopharmacology, 152, 431–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa, M. , & Goto, S. (2000). KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Research, 28, 27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel, M. (2020). Maternal mental health MATTERS. North Carolina Medical Journal, 81, 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake, D. E. , Richman, J. S. , Griffin, M. P. , & Moorman, J. R. (2002). Sample entropy analysis of neonatal heart rate variability. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 283, R789–R797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law, J. W. S. , Lee, A. Y. W. , Sun, M. , Nikonenko, A. G. , Chung, S. K. , Dityatev, A. E. , Schachner, M. , & Morellini, F. (2003). Decreased anxiety, altered place learning, and increased CA1 basal excitatory synaptic transmission in mice with conditional ablation of the neural cell adhesion molecule L1. The Journal of Neuroscience, 23, 10419–10432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuner, B. , Dye, C. , Franceschelli, D. , Ringland, A. , & Lenz, K. (2023). Perineuronal net remodeling in the prefrontal cortex across the peripartum period and in response to gestational stress. Biological Psychiatry, 93, S22. [Google Scholar]

- Leuner, B. , Fredericks, P. J. , Nealer, C. , & Albin‐Brooks, C. (2014). Chronic gestational stress leads to depressive‐like behavior and compromises medial prefrontal cortex structure and function during the postpartum period. PLoS One, 9, e89912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. S. , Suckling, J. , Fan, F. , Ji, G.‐J. , Meng, Y. , Yang, S. , Wang, K. , Qiu, J. , Chen, H. , & Liao, W. (2021). Cortical structural differences in major depressive disorder correlate with cell type‐specific transcriptional signatures. Nature Communications, 12, 1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitz, L. A. , & Goldberger, A. L. (1992). Loss of “complexity” and aging. Potential applications of fractals and chaos theory to senescence. JAMA, 267, 1806–1809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F. , Hu, M. , Wang, S. , Guo, W. , Zhao, J. , Li, J. , Xun, G. , Long, Z. , Zhang, J. , Wang, Y. , Zeng, L. , Gao, Q. , Wooderson, S. C. , Chen, J. , & Chen, H. (2012). Abnormal regional spontaneous neural activity in first‐episode, treatment‐naive patients with late‐life depression: A resting‐state fMRI study. Progress in Neuro‐Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 39, 326–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. , Seidlitz, J. , Blumenthal, J. D. , Clasen, L. S. , & Raznahan, A. (2020). Integrative structural, functional, and transcriptomic analyses of sex‐biased brain organization in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117, 18788–18798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J. , Huang, Z. , Wang, S. , Zheng, S. , & Duan, K. (2019). Postpartum depression: Association with genetic polymorphisms of noradrenaline metabolic enzymes and the risk factors. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao, 39, 57–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J. A. , Hamilton, B. E. , Osterman, M. J. K. , Driscoll, A. K. , & Drake, P. (2018). Births: Final data for 2017. National vital statistics reports, 67, 1–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy, K. , Osborne, L. M. , Nanavati, J. , & Payne, J. L. (2017). Reproductive affective disorders: A review of the genetic evidence for premenstrual dysphoric disorder and postpartum depression. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19, 94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, E. K. , & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 24, 167–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina‐Picó, A. , Cuesta‐Frau, D. , Aboy, M. , Crespo, C. , Miró‐Martínez, P. , & Oltra‐Crespo, S. (2011). Comparative study of approximate entropy and sample entropy robustness to spikes. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, 53, 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy‐Eberenz, K. , Zandi, P. P. , March, D. , Crowe, R. R. , Scheftner, W. A. , Alexander, M. , McInnis, M. G. , Coryell, W. , Adams, P. , DePaulo, J. R., Jr. , Miller, E. B. , Marta, D. H. , Potash, J. B. , Payne, J. , & Levinson, D. F. (2006). Is perinatal depression familial? Journal of Affective Disorders, 90, 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzik, M. , & Borovska, S. (2010). Perinatal depression: Implications for child mental health. Mental Health in Family Medicine, 7, 239–247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakić Radoš, S. , Tadinac, M. , & Herman, R. (2018). Anxiety during pregnancy and postpartum: Course, predictors and comorbidity with postpartum depression. Acta Clinica Croatica, 57, 39–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoloro‐SantaBarbara, J. M. , Carroll, J. E. , Minissian, M. , Kilpatrick, S. J. , Cole, S. , Merz, C. N. B. , & Accortt, E. E. (2022). Immune transcriptional profiles in mothers with clinically elevated depression and anxiety symptoms several years post‐delivery. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 88, e13619. 10.1111/aji.13619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noori, M. , Hasbi, A. , Sivasubramanian, M. , Milenkovic, M. , & George, S. R. (2020). Maternal separation model of postpartum depression: Potential role for nucleus Accumbens dopamine D1‐D2 receptor Heteromer. Neurochemical Research, 45, 2978–2990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier, J. D. A. , Åkerud, H. , Skalkidou, A. , Kaihola, H. , & Sundström‐Poromaa, I. (2015). The effects of antenatal depression and antidepressant treatment on placental gene expression. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 8, 465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orchard, E. R. , Voigt, K. , Chopra, S. , Thapa, T. , Ward, P. G. D. , Egan, G. F. , & Jamadar, S. D. (2023). The maternal brain is more flexible and responsive at rest: Effective connectivity of the parental caregiving network in postpartum mothers. Scientific Reports, 13, 4719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pařízek, A. , Mikešová, M. , Jirák, R. , Hill, M. , Koucký, M. , Pašková, A. , Velíková, M. , Adamcová, K. , Šrámková, M. , Jandíková, H. , Dušková, M. , & Stárka, Ľ. (2014). Steroid hormones in the development of postpartum depression. Physiological Research, 63(Suppl 2), S277–S282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne, J. L. , & Maguire, J. (2019). Pathophysiological mechanisms implicated in postpartum depression. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 52, 165–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei‐Shan, H. , Chemin, L. , Guan‐Yen, C. , Ho‐Ling, L. , Chih‐Mao, H. , Tatia Mei‐Chun, L. , Shwu‐Hua, L. , & Shun‐Chi, W. (2017). Complexity analysis of resting state fMRI signals in depressive patients. Annual international conference of the IEEE engineering in medicine and biology society. IEEE engineering in medicine and biology society. Annual International Conference, 2017, 3190–3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protzner, A. B. , Valiante, T. A. , Kovacevic, N. , McCormick, C. , & McAndrews, M. P. (2010). Hippocampal signal complexity in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: A noisy brain is a healthy brain. Archives Italiennes de Biologie, 148, 289–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman, J. S. , & Moorman, J. R. (2000). Physiological time‐series analysis using approximate entropy and sample entropy. American Journal of Physiology: Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 278, H2039–H2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, P. , Tovar, R. , Ramírez‐López, M. T. , Navarro, J. A. , Vargas, A. , Suárez, J. , & Fonseca, F. R. (2020). Sex‐specific anxiety and prefrontal cortex glutamatergic dysregulation are Long‐term consequences of pre‐and postnatal exposure to Hypercaloric diet in a rat model. Nutrients, 12, 1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M. , Whitehouse, A. J. O. , Newnham, J. P. , Gorman, S. , Jacoby, P. , Holt, B. J. , Serralha, M. , Tearne, J. E. , Holt, P. G. , Hart, P. H. , & Kusel, M. M. H. (2014). Low maternal serum vitamin D during pregnancy and the risk for postpartum depression symptoms. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 17, 213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelofs, J. , Huibers, M. , Peeters, F. , Arntz, A. , & van Os, J. (2008). Rumination and worrying as possible mediators in the relation between neuroticism and symptoms of depression and anxiety in clinically depressed individuals. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 1283–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero‐Gonzalez, B. , Caparros‐Gonzalez, R. A. , Gonzalez‐Perez, R. , Coca‐Arco, S. , & Peralta‐Ramirez, M. I. (2019). Hair cortisol levels, psychological stress and psychopathological symptoms prior to instrumental deliveries. Midwifery, 77, 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, B. R. , & Savoy, R. L. (2012). fMRI at 20: Has it changed the world? NeuroImage, 62, 1316–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, L. E. , Gilbert Evans, S. E. , Sellers, E. M. , & Romach, M. K. (2003). Measurement issues in postpartum depression part 1: Anxiety as a feature of postpartum depression. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 6, 51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabihi, S. , Dong, S. M. , Durosko, N. E. , & Leuner, B. (2014). Oxytocin in the medial prefrontal cortex regulates maternal care, maternal aggression and anxiety during the postpartum period. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 6, 258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabihi, S. , Goodpaster, C. , Maurer, S. , & Leuner, B. (2021). GABA in the medial prefrontal cortex regulates anxiety‐like behavior during the postpartum period. Behavioural Brain Research, 398, 112967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxe, G. N. , Calderone, D. , & Morales, L. J. (2018). Brain entropy and human intelligence: A resting‐state fMRI study. PLoS One, 13, e0191582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff, J. P. , Garner, A. S. , The Committee On Psychosocial Aspects Of Child And Family Health Coec Adoption, And Dependent Care, And Section On Developmental And Behavioral Pediatrics , Siegel, B. S. , Dobbins, M. I. , Earls, M. F. , et al. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129, e232–e246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey, S. , Chee, C. Y. I. , Ng, E. D. , Chan, Y. H. , Tam, W. W. S. , & Chong, Y. S. (2018). Prevalence and incidence of postpartum depression among healthy mothers: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 104, 235–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S. M. , Beckmann, C. F. , Andersson, J. , Auerbach, E. J. , Bijsterbosch, J. , Douaud, G. , Duff, E. , Feinberg, D. A. , Griffanti, L. , Harms, M. P. , Kelly, M. , Laumann, T. , Miller, K. L. , Moeller, S. , Petersen, S. , Power, J. , Salimi‐Khorshidi, G. , Snyder, A. Z. , Vu, A. T. , … Glasser, M. F. (2013). Resting‐state fMRI in the human connectome project. NeuroImage, 80, 144–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokunbi, M. O. (2014). Sample entropy reveals high discriminative power between young and elderly adults in short fMRI data sets. Frontiers in Neuroinformatics, 8, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, G. C.‐Y. , Chu, C. , Lee, Y. T. , Tan, C. C. K. , Ashburner, J. , Wood, N. W. , & Frackowiak, R. S. J. (2020). The influence of microsatellite polymorphisms in sex steroid receptor genes ESR1, ESR2 and AR on sex differences in brain structure. NeuroImage, 221, 117087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Y. , Liu, B. , Zhang, X. , Li, J. , Qin, W. , Yu, C. , & Jiang, T. (2015). The structural connectivity pattern of the default mode network and its association with memory and anxiety. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy, 9, 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarantino, L. M. , Sullivan, P. F. , & Meltzer‐Brody, S. (2011). Using animal models to disentangle the role of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental influences on behavioral outcomes associated with maternal anxiety and depression. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2, 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treloar, S. A. , Martin, N. G. , Bucholz, K. K. , Madden, P. A. , & Heath, A. C. (1999). Genetic influences on post‐natal depressive symptoms: Findings from an Australian twin sample. Psychological Medicine, 29, 645–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B. , Niu, Y. , Miao, L. , Cao, R. , Yan, P. , Guo, H. , Li, D. , Guo, Y. , Yan, T. , Wu, J. , Xiang, J. , & Zhang, H. (2017). Decreased complexity in Alzheimer's disease: Resting‐state fMRI evidence of brain entropy mapping. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 9, 378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. , Xie, S. , Guo, X. , Becker, B. , Fox, P. T. , Eickhoff, S. B. , & Jiang, T. (2017). Correspondent functional topography of the human left inferior parietal lobule at rest and under task revealed using resting‐state fMRI and Coactivation based Parcellation. Human Brain Mapping, 38, 1659–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. , Li, Y. , Childress, A. R. , & Detre, J. A. (2014). Brain entropy mapping using fMRI. PLoS One, 9, e89948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker, K. J. , Vértes, P. E. , Romero‐Garcia, R. , Váša, F. , Moutoussis, M. , Prabhu, G. , Weiskopf, N. , Callaghan, M. F. , Wagstyl, K. , Rittman, T. , Tait, R. , Ooi, C. , Suckling, J. , Inkster, B. , Fonagy, P. , Dolan, R. J. , Jones, P. B. , Goodyer, I. M. , the, N.C , … Villis, L. (2016). Adolescence is associated with genomically patterned consolidation of the hubs of the human brain connectome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113, 9105–9110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. , Chen, K. , Zhang, J. , Ma, Y. , Chen, M. , Shao, H. , Zhang, X. , Fan, D. , Wang, Z. , Sun, Z. , & Wang, J. (2023). Molecular mechanisms underlying human spatial cognitive ability revealed with neurotransmitter and transcriptomic mapping. Cerebral Cortex., 33, 11320–11328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , Mu, Y. , Li, X. , Sun, C. , Ma, X. , Li, S. , Li, L. , Zhang, Z. , & Qi, S. (2022). Improved interhemispheric functional connectivity in postpartum depression disorder: Associations with individual target‐transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment effects. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 859453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J. X. , Chen, Y. C. , Chen, H. , Jiang, L. , Bo, F. , Feng, Y. , Tang, W. W. , Yin, X. , & Gu, J. P. (2018). Disrupted spontaneous neural activity related to cognitive impairment in postpartum women. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D. , Yuan, T. , Gao, J. , Xu, Q. , Xue, K. , Zhu, W. , Tang, J. , Liu, F. , Wang, J. , & Yu, C. (2021). Correlation between cortical gene expression and resting‐state functional network centrality in healthy young adults. Human Brain Mapping, 42, 2236–2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FIGURE S1. Correlations between FCs and PSS scores. The FC of PCC_L‐PCL_R were negatively correlated with PSS scores before correction for multiple comparisons in the PDD group. The FC of MPFC_L‐AG_R were positively correlated with PSS scores in the PDD‐A group.

FIGURE S2. Gene enrichment analysis and the corresponding PPI network of the set of genes resolving PPDs obtained from changes in FCs of MPFC_L‐AG_R. (a) Triplicate histograms were plotted for GO enrichment analysis of biological processes (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular functions (MF). All the results were obtained with p < 0.05 (BH‐FDR correction). (b) Bubble plot was used to show the KEGG enrichment analysis results obtained with p < 0.05 (BH‐FDR correction). (c) A PPI network was constructed using significantly associated genes with changes of FCs. (d) The top 10 hub genes of the PPI network were shown and different colors represent the size of degree (The dark red represents higher degree values and the yellow represent lower degree values).

FIGURE S3. Gene enrichment analysis and the corresponding PPI network of the set of genes resolving PPDs obtained from changes in FCs of PCC_L‐PCL_R. (a) Triplicate histograms were plotted for GO enrichment analysis of biological processes (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular functions (MF). All the results were obtained with p < 0.05 (BH‐FDR correction). (b) Bubble plot was used to show the KEGG enrichment analysis results obtained with p < 0.05 (BH‐FDR correction). (c) A PPI network was constructed using significantly associated genes with changes of FCs. (d) The top 10 hub genes of the PPI network were shown and different colors represent the size of degree (The dark red represents higher degree values and the yellow represent lower degree values).

Data Availability Statement

All data and code used for data analysis are available upon request.