Abstract

There are many lesions that cause compression of nerves and vessels in the head and neck, and they can often be overlooked in the absence of adequate history or if not suspected by the radiologist. Many of these lesions require a high index of suspicion and optimal positioning for imaging. While a multimodality approach is critical in the evaluation of compressive lesions, an MRI utilizing high-resolution (heavily weighted) T2-weighted sequence is extremely useful as a starting point. In this review, we aim to discuss the radiological features of the common and uncommon compressive lesions of the head and neck which are broadly categorized into vascular, osseous, and miscellaneous etiologies.

Keywords: compressive lesions, trigeminal neuralgia, glossopharyngeal neuralgia, cervical rib, hemifacial spasm, trochlear nerve palsy, optic neuropathy

Introduction

There are many lesions that can cause compression of nerves and vessels of the head and neck, and many of these can be overlooked if not suspected by the radiologist or proper symptoms are not provided in the history. In addition, patients may not have symptoms in the neutral position but may experience symptom provocation in certain positions; therefore, it is important to perform imaging with the patient in the specific position that causes the symptoms, or the lesion may be missed. The purpose of this review is to discuss the common and uncommon compressive lesions of the head and neck, including potential mimics due to intrinsic pathology. These can be broadly categorized into vascular, osseous, and miscellaneous etiologies.

Vascular etiologies

Trigeminal neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is characterized by paroxysmal unilateral orofacial pain in the distribution of the facial or intraoral trigeminal nerve territory. 1 The pathognomic pain, often described as sudden brief stabbing or electric-shock like attacks can be triggered by maneuvers including innocuous mechanical stimuli, facial or oral movements, or complex activities such as shaving or applying make-up. These symptoms may be elicited on physical examination as well.1,2 Classical TN is a specific category of TN wherein there is evidence of vascular compression either demonstrated on MRI or intraoperatively during neurovascular decompression, along with morphological changes within the trigeminal root.1,3 Most vascular compressions in classical TN occur at the transitional zone (TZ) which is the microscopic region where the nerve sheath transitions from central myelin to peripheral myelin and is most vulnerable to compression.4–6 The offending vessels in classical TN from most common to less common include the superior cerebellar artery, anterior inferior cerebellar artery, basilar artery, and petrosal vein.7,8

Imaging

A pre-contrast CT of the head may be normal. A post-contrast CT of the brain and skull base is helpful in cases of secondary TN, such as sinus masses, cerebellopontine angle (CPA) masses, and skull base lesions. CT angiogram of the head can help evaluate vascular anatomy, such as ectasia or dolichoectasia of the vertebrobasilar system, but cannot demonstrate neurovascular compression. The best imaging tool is an MRI with high resolution sequences such as Constructive Interference in Steady State (CISS), Fast Imaging Employing Steady-state Acquisition (FIESTA), T2 Sampling Perfection with Application optimized Contrasts using different flip angle Evolution (SPACE), 3DT2, etc. (Figure 1). These sequences best delineate the morphology of the cisternal trigeminal nerve.9,10 Additionally, the offending arteries or veins are seen as serpiginous flow voids that contact or compress the trigeminal nerve. Compressed nerves can be displaced, deformed, or appear atrophic. Nerve displacement or atrophy directly represent clinically significant compression and have been reported as 97% specific for classical TN. Moreover, compression of the trigeminal nerve at its entry into the brainstem has a nearly 100% sensitivity and positive predictive value.6,9–11 Although heavily T2-weighted sequences yield excellent anatomic detail, there is often poor contrast between the nerves and the vessels. There is utility in contrast-enhanced 3D-CISS imaging to improve the characterization of high-grade neurovascular compression, localize the side of patient symptoms and predict the outcome following microvascular decompression (MVD). In conjunction with high-resolution MRI, an MR angiogram allows for localization and identification of vertebrobasilar branches in the posterior fossa. There is some utility in post-contrast enhanced T1W imaging of the brain, which may improve visualization of neurovascular relationships by causing the vessels to enhance. Furthermore, a post-contrast T1-weighted sequence helps rule out non-neurovascular abnormalities, such as enhancing masses in the cerebellopontine angle, skull base, leptomeninges or cranial nerves, as well as perineural spread of tumor. The diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequence can distinguish lesions such as an epidermoid which demonstrates diffusion restriction. 11 The FLAIR sequence may help suggest multiple sclerosis which is a cause of secondary TN.12,13

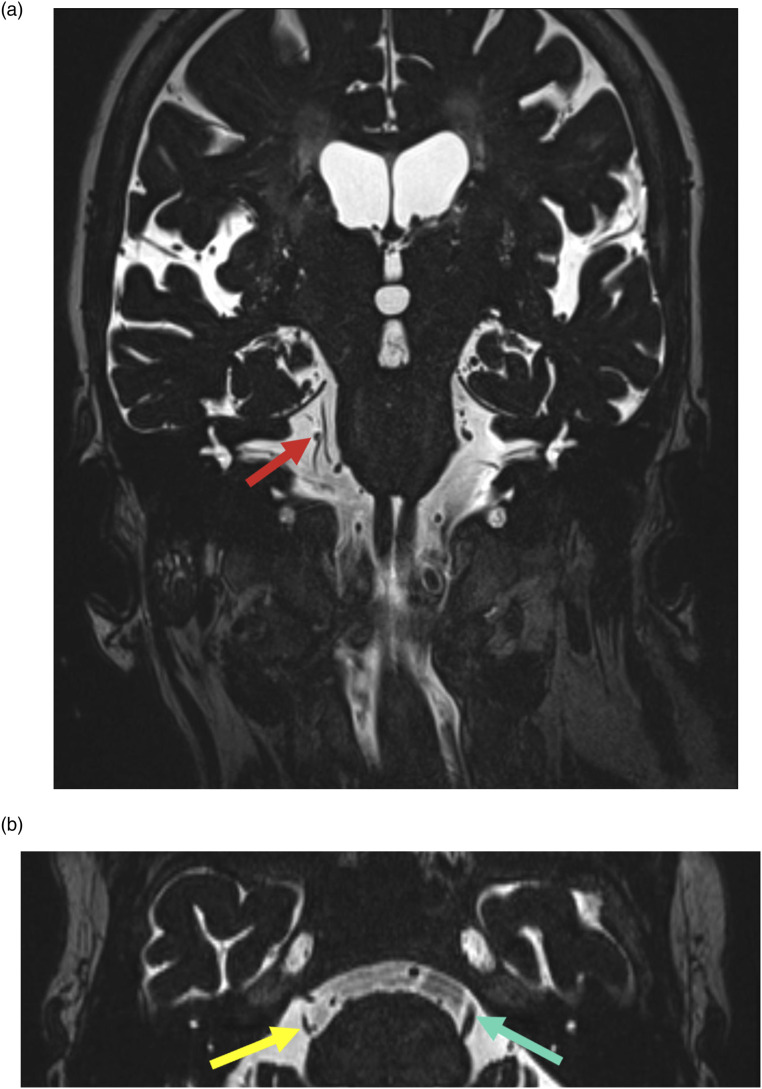

Figure 1.

81-year-old female with long-standing sharp right face pain. Coronal high-resolution T2WI MRI (a) shows abutment of the right trigeminal nerve by a branch of the right superior cerebellar artery (red arrow). Axial high-resolution T2WI MRI (b) shows resultant volume loss of the nerve (yellow arrow); note normal bulk on the left (green arrow).

Management

The most common first-line management is pharmacologic therapy. 14 Transcutaneous approach (nerve stimulation, focused ultrasound, transcranial MR cortical stimulation), percutaneous (chemodenervation with alcohol or glycerol, radiofrequency ablation, cryoablation, nerve block, balloon compression), radiotherapy (CyberKnife, Gamma Knife) and open surgical options such as MVD are available if conservative therapy fails.14,15

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia (previously termed “vagoglossopharyngeal neuralgia”) is described by a pattern of unilateral, brief (lasting few seconds to 2 min), sharp stabbing pain with sudden onset and termination in the distributions of both the glossopharyngeal nerve, and the auricular and pharyngeal branches of the vagus nerve. 3 Pain is typically experienced in the ear, base of tongue, pharynx, and tonsillar fossa and precipitated by coughing, chewing, or swallowing.3,16,17 Rarely it has also been associated with hemodynamic instability including cardiac syncope due to activation of vagal reflex pathways likely within the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve.18,19 The nerve at its emergence from the brainstem is at risk of compression by an enlarged posterior inferior cerebellar, vertebral, or anterior inferior cerebellar artery. Non-vascular etiologies include tumors, multiple sclerosis, Chiari I morphology, infarct, neck trauma, or elongated styloid process (Eagle syndrome).3,20–22 Occasionally, GN can also be caused by compression as a post-operative complication of trigeminal nerve MVD. 23 When compared to TN, GN is less common, likely due to the short length of central myelin along the glossopharyngeal nerve that offers only a small anatomical area for clinically significant neurovascular compression. 24

Imaging

CT of the head is inadequate to visualize the glossopharyngeal nerve, but it is useful to evaluate the pars nervosa of the jugular foramen that houses the glossopharyngeal nerve. 25 As in TN, evaluation of GN is also best performed with MRI with high resolution T2-weighting imaging such as CISS, FIESTA, T2-SPACE, and with vascular imaging such as MR angiography with time-of-flight.22,24 The extent of vascular compression can be analyzed by the absence of CSF between nerve and the offending vessel, as well as by structural change causing concavity due to vascular compression (Figure 2). 7 Of note, evaluation of the supraolivary fossette which is the medial-most portion of the CPA and is in close proximity to the root entry zone (REZ) is an important component of pre-surgical workup. 26 The primary objective of imaging is to exclude non-vascular causes as mentioned previously. Using contrast-enhanced MRI to evaluate mass lesions and multiple sclerosis, along with FLAIR and diffusion sequences, is crucial in this exclusion process.

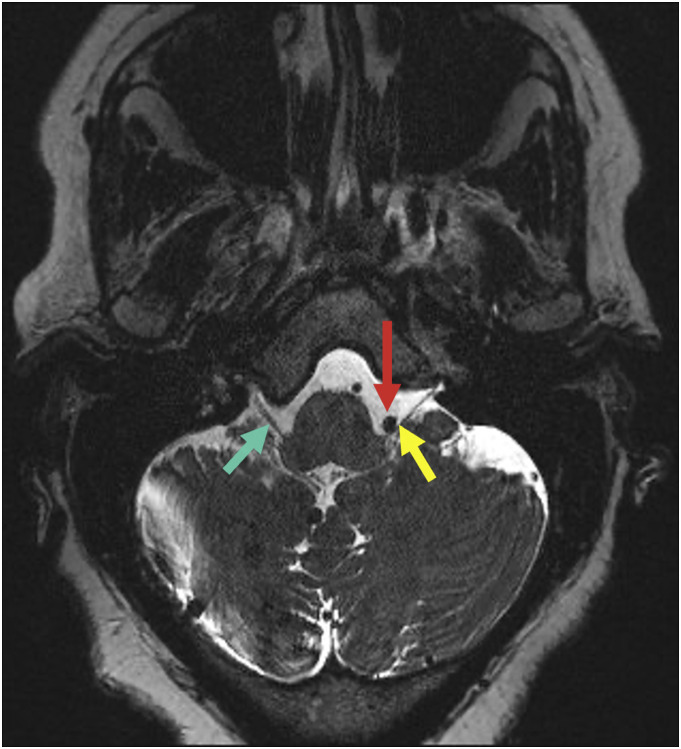

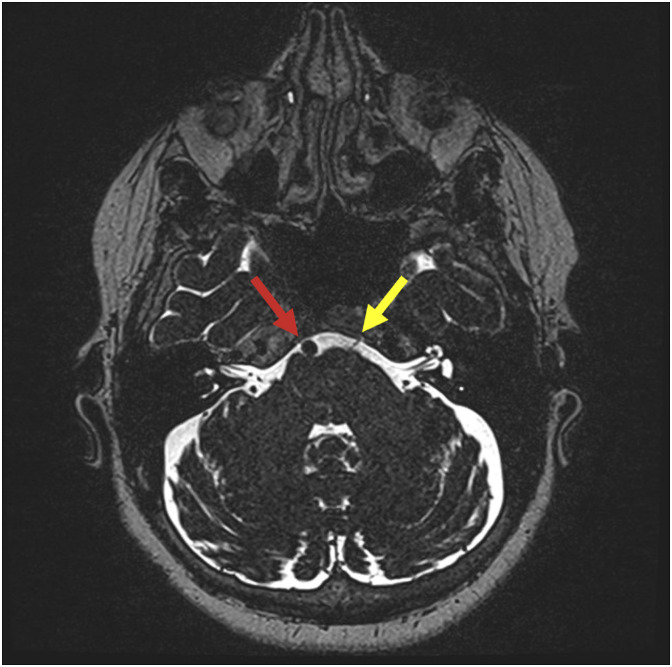

Figure 2.

60-year-old female with intermittent stabbing left throat pain. Axial T2-SPACE image through the brainstem demonstrates the V4 segment of the left vertebral artery (red arrow) contacting the left IX/X nerve complex (yellow arrow) near the root entry zone. Note the normal right side (green arrow).

Management

First-line treatments include pharmacologic therapy with anticonvulsants. In patients not responding to medical therapy or those complicated by adverse reactions, interventions such as MVD, stereotactic radiosurgery, peripheral glycerol rhizotomy, CT-guided percutaneous tractotomy–nucleotomy, and percutaneous thermorhizotomy have been reported as options.27–32

Vestibulocochlear nerve compression

Vascular compression of the vestibulocochlear nerve and its clinical significance remain controversial. The most thought vascular offender is the anterior inferior cerebellar artery loops. However, Clift and colleagues did not find a significant correlation between symptoms and vascular compression of the vestibulocochlear nerve. 33 Other theories such as advancing age and arterial elongation, pulsatile vascular compression causing demyelination, and atherosclerotic hardening of the arterial wall have also been reported. Imaging techniques are similar to that discussed with the trigeminal nerve, although, whether the presence of neurovascular conflict is related to symptomatology is debatable.

Occipital neuralgia

Occipital neuralgia is defined by unilateral or bilateral paroxysmal sharp pain in the distribution of the greater, lesser, and/or the third occipital nerve. 3 The pain may be associated with dysesthesia or allodynia of the scalp. 3 Most cases of occipital neuralgia are idiopathic. Other specific causes include trauma, prior skull base surgery, atlantoaxial osteoarthritis, or mass lesion.34,35 Vascular compression is relatively rare, but the most common vascular offenders include an anomalous ectatic vertebral artery, 36 fenestrated vertebral artery, 37 and posterior inferior cerebellar artery. 35 A critical differential to keep in mind is temporal arteritis which can present as occipital neuralgia even in the absence of an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate level as the management includes prompt administration of steroids. 38

Imaging

The utility of imaging is limited to identifying the small proportion of cases that are not idiopathic. CT of the head and cervical spine can show post-traumatic or degenerative disease at the C1-C2 articulation. MRI of the brain and cervical spine with inclusion of T2-weighted sequences have been shown to depict the offending vessels. Furthermore, T2-weighted imaging and contrast enhanced imaging can help detect lesions causing occipital neuralgia.

Management

Conservative management with cervical collars, peripheral nerve stimulation, analgesics, antimigraine medication, local nerve block, and nerve ablation have been attempted, with variable degrees of success. 34 Surgical treatments include greater occipital nerve decompression and C1-C2 arthrodesis.39,40

Hemifacial spasm

Hemifacial spasm is characterized by painless, paroxysmal spasm of the orbicularis oculi muscle secondary to unilateral hyperexcitability of the facial nerve. This condition can often progress in frequency and severity to involve the remainder of the facial muscles and, rarely, the contralateral side. 41 Primary hemifacial spasms are typically the result of vascular compression of the nerve at the anterior caudal REZ by the ipsilateral posterior inferior cerebellar, anterior inferior cerebellar, vertebral, basilar, or cochlear artery.42–45 Even gentle contact by a cerebellar artery on the centrally myelinated nerve fibers is sufficient to cause hemifacial spasm. 43 Few cases of vascular compression of the distal, cisternal portion of the facial nerve have also been reported, identified in patients with recurrent hemifacial spasms or failed MVD procedures.45,46,47

Imaging

CT of the head with contrast and CT angiography of the head can reveal ectasia, dolichoectasia, or malposition of the vertebrobasilar system, but neither can detect nerve compression.48–50 Similarly, digital subtraction angiography (DSA) cannot depict the exact relationship between the vessels and nerves. 51 The best imaging tool is an MRI with high-resolution T2-weighted imaging or source MR angiography images that show serpentine asymmetric signal void representative of a compressive vessel at the facial nerve root exit zone in the medial CPA (Figure 3). 51 MRI FLAIR sequence is valuable in evaluating for underlying multiple sclerosis presenting as hemifacial spasm. 52 Post-contrast MRI sequences can also provide information on other secondary etiologies of hemifacial spasm such as perineural tumor spread and cranial neuritis. 53

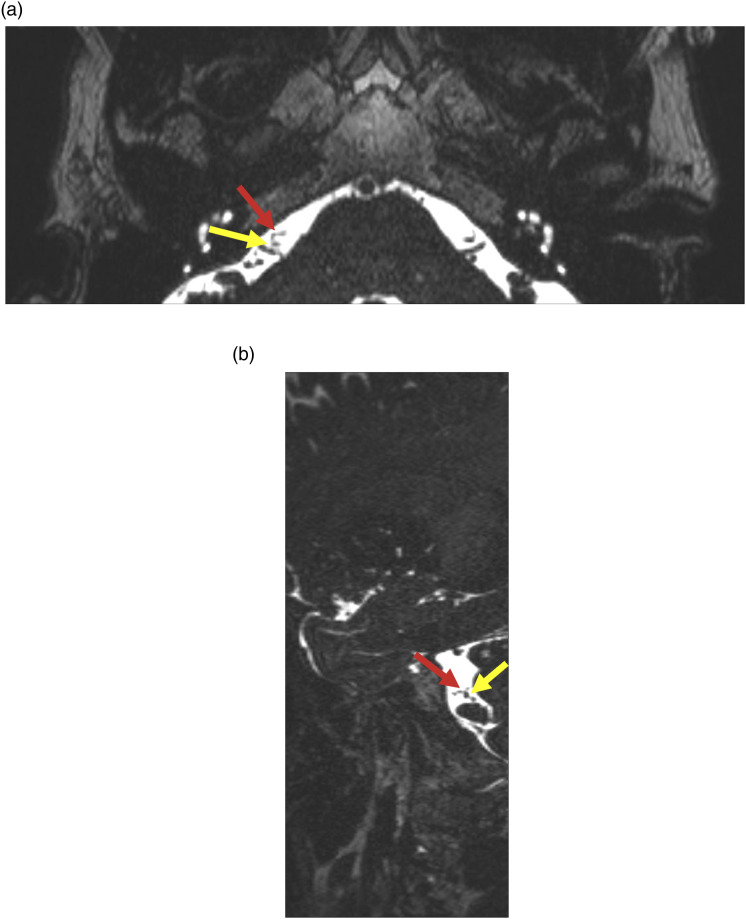

Figure 3.

55-year-old female with right facial hemispasm and twitching of the right lip. Axial high resolution T2WI MRI (a) and Sagittal T2WI MRI (b) show abutment of the right facial nerve (yellow arrow) by a vessel of unclear origin (red arrow).

Management

The two most accepted treatments for hemifacial spasms are botulinum toxin injection which provides sustained symptomatic relief by blocking acetylcholine release from presynaptic motor neurons and MVD which has a greater than 90% reported success rate in addressing the underling compressing vascular loop.54,55

Trochlear nerve palsy

The most common etiology of unilateral trochlear nerve palsy is congenital. 56 However, the thin morphological structure, the long intracranial course and the slender connection to the brainstem render the trochlear nerve highly susceptible to trauma and neurovascular compression.57–59 Indeed, up to 75% of cases of bilateral trochlear nerve palsy have been reported to be a result of trauma. 56 Patients may present with vertical diplopia, ipsilateral hypertropia without ptosis, and head tilt to the contralateral side. 60 Etiologies include neurovascular compression due to internal carotid artery compression, aneurysms, and subarachnoid hemorrhage.58,61

Imaging

The cisternal segment of the trochlear nerve is difficult to identify reliably on conventional MRI. As in TN, the utilization of high-resolution 3D sequences such as FIESTA have been shown to identify the trochlear nerve (Figure 4). 62 Additionally, using a voxel size smaller than the diameter of the trochlear nerve enables better visualization of the nerve. 62 Another study demonstrated easier identification of the trochlear nerve by using anatomic landmarks such as the trochlear groove and the trochlear cistern on fluid sensitive sequences. 63

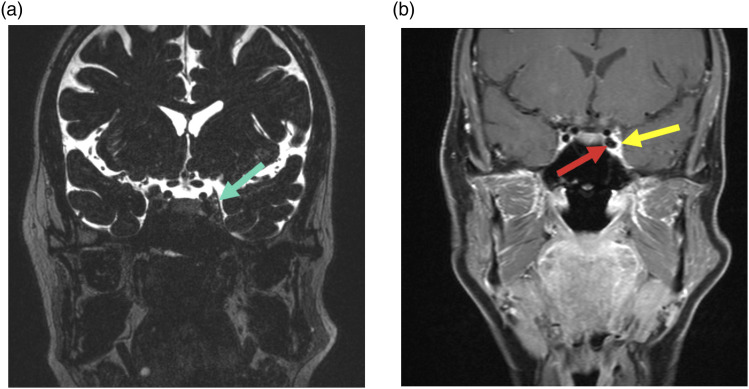

Figure 4.

58-year-old female with vertical diplopia and left trochlear nerve palsy. Coronal T2WI MRI (a) shows slight prominence of the left superior cavernous sinus at the expected location of the trochlear nerve (green arrow). Coronal T1 post-contrast image (b) shows ectasia of the left internal carotid artery (red arrow), presumed to be abutting the trochlear nerve (yellow arrow).

Management

Treatment of the underlying neurovascular cause, particularly in cases of ICA aneurysms or subarachnoid hemorrhage due to ruptured posterior communicating artery aneurysms.58,61

Abducens nerve palsy

Isolated abducens nerve palsy is rare and often results from neurovascular compression of the abducens nerve at the REZ by dolichoectasia or aneurysms in the vertebrobasilar system.64–67 Specifically, the most common offending vessels include the basilar artery, vertebral artery, and anterior inferior cerebellar artery. 68 Other etiologies of isolated nerve palsy include meningitis, malignancy, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus or hypertension, petrous apex or orbital syndromes, cavernous sinus syndrome, pontine infarct involving the abducens nerve fascicle, intracranial hypertension or hypotension.69,70 Furthermore, the etiology is not definitively identified in about 18–30% of patients. 71

Imaging

CT of the head with contrast and CT angiography of the head can demonstrate distinct dolichoectasia of the vertebrobasilar system but as in the previously described neurovascular compression syndromes, neither imaging modality can detect nerve compression. However, the bone reconstructions in a CT brain is valuable for assessing the skull base and bony foramina, thereby ruling out alternative causes of abducens nerve palsy pertaining to the course of the cranial nerve from the brainstem to the orbit. Additionally, CT angiography of the head is beneficial in diagnosing occult carotid-cavernous fistulas, which can result in abducens nerve palsy. 71 The gold standard for visualization of the nerve includes an MRI of the brain with thin section high resolution T2-weighted imaging and enhanced T1 imaging or source MR angiography images, as these techniques delineate cranial nerves surrounded by CSF, with high spatial resolution (Figure 5).68,73

Figure 5.

75-year-old female with diplopia and right VI nerve palsy. Axial high-resolution T2WI shows dolichoectasia of the basilar artery (red arrow), coursing along the exit point at the level of right VI cranial nerve. Note the normal left VI cranial nerve (yellow arrow).

Management

Various treatments have been reported including observation, prism lenses, and MVD. Interestingly, MVD for the management of trigeminal neuralgia has been reported to cause temporary abducent nerve neurapraxia due to manipulation of the dolichoectatic vessels and stretching of the abducens nerve, for which observation is only required. 74 However, due to the small number of surgically treated cases of isolated abducens nerve palsy, determining surgical indication and timing of MVD has been challenging. 68 Spontaneous recovery due to neurovascular compromise is presumably low and therefore treatment with MVD is a strong consideration in long-standing abducens nerve palsy (4–6 months or longer). 68

Medullary compression

Vascular indentation and mass effect on the medulla can result in medullary compression syndromes that presents with ataxia, vertigo, persistent headaches, limb weakness, dysarthria, and dysphagia. 75 The most common site of compression is the anterolateral aspect of the medulla and the most common offending vessels are the vertebral artery and the posterior inferior cerebellar artery. 75 Medullary compression is more common in the older population with hypertension and diabetes due to progressive vascular wall damage, 76 although some studies report equipoise among normotensive and hypertensive patients. 77

Imaging

CT angiogram of the head demonstrates dolichoectasia of the vertebrobasilar system, but medullary compression cannot be appreciated on a CT angiogram study. The best imaging technique is an MRI of the brain with heavily weighted T2 sequences that depicts dolichoectasia of the vertebrobasilar system with compression, indentation, or deformity of the medulla (Figure 6). Pre-operative evaluation also includes 3D-gradient echo T2-weighted imaging (CISS) and MR angiography time-of-flight.78–81 However, a major limitation of 3D sequences are the flow-related signal variability of vessels and CSF pulsation artifacts. 82

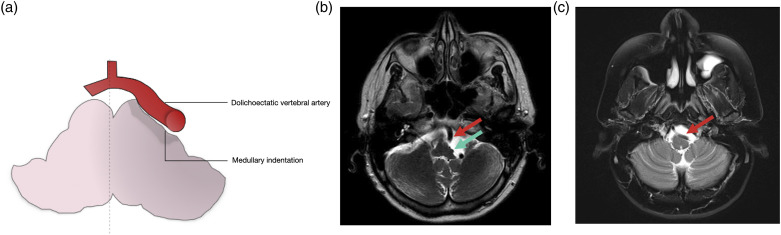

Figure 6.

Schematic representation medullary indentation by dolichoectatic vertebral artery. (a) 62-year-old female with ataxia and vertigo. Axial T2WI MRI (b) shows indentation and deformity of the left lateral aspect of the medulla (green arrow) by a dolichoectatic vertebral artery (red arrow). (c) 35-year-old female with persistent throbbing headaches. Axial T2WI MRI (b) shows mass effect on the anterolateral left medulla by a dolichoectatic vertebral artery (red arrow).

Management

Conservative management with antiplatelets, anticoagulants, and analgesics has been reported to be effective. 75 MVD of the medulla is not a standard procedure but has been reported to have significant improvement of deficits. However, some authors recommend consideration of MVD in selected patients with intractable severe hypertension, based on the lack of significant improvement and potential for complications from new cranial nerve lesions. 83

Osseous etiologies

Cervical ribs

Cervical ribs (CR) are supernumerary ribs arising as an extension of the lateral process of C7 vertebra during development. It occurs in 0.5–1.0% of the population.84,85 The prevalence of a CR is more common in women than men. 86 The presence of a CR is about 25 times higher in patients with thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS). 87 CR is classified into four types. Type 1 is a complete rib that articulates with the manubrium sternum and type 2 has a free distal tip that does not articulate with the sternum. Type 3 has a fibrous distal segment that is attached to the sternum and type 4 is just an extension from the transverse process of the C7 vertebra. Presence of a CR is found mostly incidentally; for a patient to be symptomatic with TOS, a combination of predisposing factors like a CR or fibrous bands along with aggravating factors including hyperextension/abduction of the upper limb are present. TOS can be neurogenic, vascular, or mixed. Ninety percent of the cases of TOS are neurogenic due to compression of the brachial plexus. This results in ipsilateral pain or paresthesia in the head, neck, shoulder, or arm. Prolonged compression can lead to atrophy of the intrinsic hand muscles and loss of function.86,89 Vascular compression can be due to subclavian artery or vein involvement leading to thrombosis, as well as aneurysm formation and distal limb ischemia.

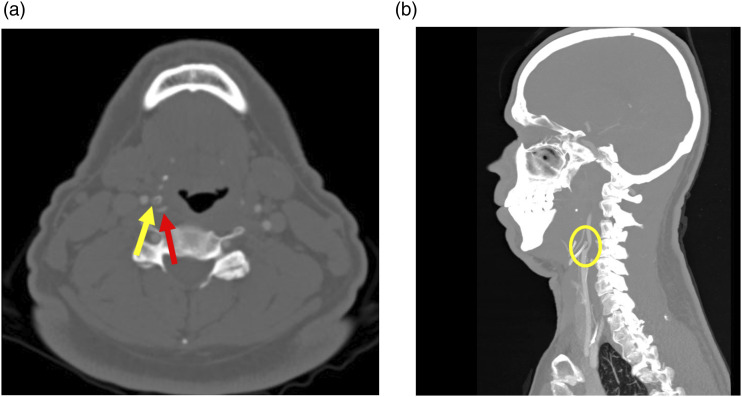

Imaging

Chest radiography or cervical radiography is the initial modality of choice to identify CR. Ultrasound in either B-mode or Doppler is also helpful in the setting of vascular TOS to identify the changes in vessel caliber and blood flow during adducted and abducted position of the arm.90,91 In equivocal cases, a contrast-enhanced CTA or MRA can be helpful. CTA with 3D reconstruction is helpful in delineating the location and extent with adjacent anatomical structures in addition to identifying vascular compression and thrombosis. However, the application of provocative maneuvers with hyperabduction of the upper limb can be limited due to the gantry size.92–94 Cervical ribs can often be misdiagnosed as an elongated transverse process. A coronal reconstructed image in CT will help differentiate between the two based on the articulation between the CR and vertebral body (Figure 7). 86 MRA with T1W sagittal sequences can better demonstrate neurovascular compression along with vascular thrombosis, whereas coronal sequences aid in assessing the brachial plexus. Images can be acquired pre- and post-provocative maneuvers with arm adduction and abduction while keeping the head and neck in neutral position.92,95 An additional benefit of MRI in multiple positions is the lack of radiation.

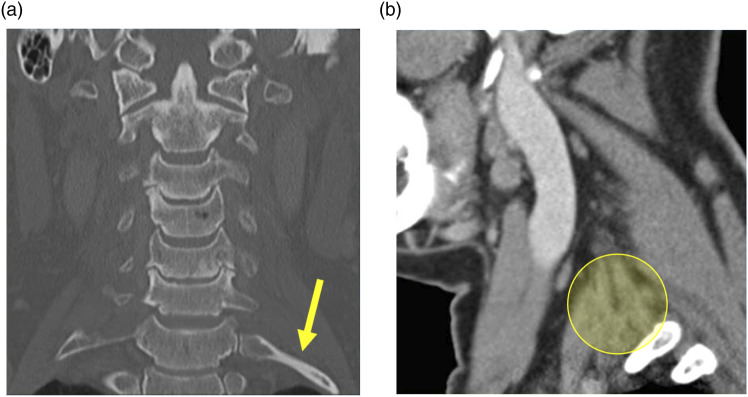

Figure 7.

54-year-old male with intermittent left Horner syndrome and left brachial plexopathy. Coronal CT neck image in the bone window (a) shows bilateral cervical ribs (yellow arrow pointing to the left). Sagittal image in the soft tissue window (b) shows the expected location of the left inferior cervical ganglion and brachial plexus (yellow circle), presumably compressed/stretched by the left cervical rib upon movement.

Management

For patients with persistent symptoms, management includes CR resection. 96 Combined first rib resection along with CR resection will provide more space for the neurovascular bundle and thereby lower chance of symptom recurrence. 96 For patients with incidentally discovered CR, counselling should be provided about the occurrence of TOS.

Bow hunter syndrome

Bow hunter syndrome or rotational vertebral artery occlusion syndrome is caused by vertebrobasilar insufficiency due to a rotational compression of the dominant vertebral artery. The second part of the vertebral artery runs vertically through the transverse foramina, typically of C1 to C6 vertebrae. Compression can be caused primarily by adjacent osteophytes, fibrous bands, herniated disc, tumors or secondarily due to post-intervention or trauma.97–99 Aggravating factors include hypoplasia or stenosis of the contralateral vertebral artery. 100 Depending on the level of posterior circulation insufficiency, symptoms can either be transient or persistent, varying from presyncope or syncope to strokes.

Imaging

Due to the wide range of nonspecific symptoms patients present with, an initial work up to exclude other possible causes including carotid occlusion and vestibular diseases is recommended. CT head can reveal offending agents such as osteophytes and ossification of the posterior atlantooccipital membrane. As per angiographic evidence, the most common sites of compression are typically at C1-C2 and C5-C7, which are the most dynamic parts of the artery.101,101 Dynamic digital subtraction vertebral angiography remains the gold standard for diagnosis. Acquisition of images during the neutral position aids in assessing the patency of the artery, whereas images on rotated position of the neck will reveal the presence and level of stenosis (Figures 8 and 9).102,103

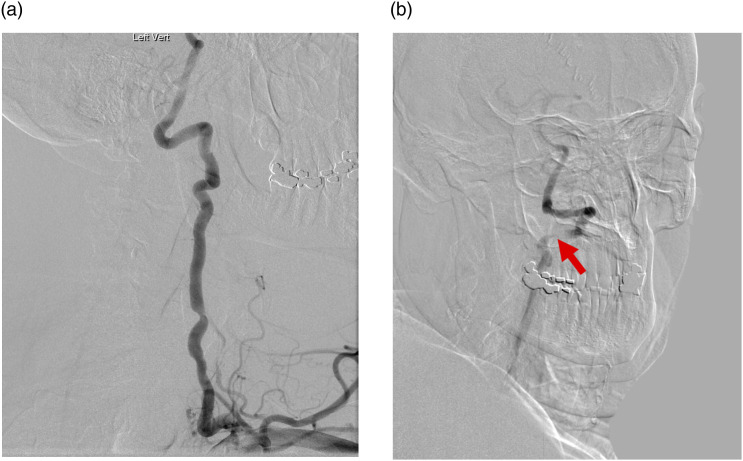

Figure 8.

68-year-old male with rotational syncope. Axial CTA of the neck shows symmetric vertebral arteries (green arrows) in the neutral position (a) and asymmetric severe narrowing of left vertebral artery (red arrow) when head is rotated to the right (b).

Figure 9.

68-year-old male with rotational syncope (same patient as Figure 8). Conventional angiogram demonstrates normal filling of the left vertebral artery in the neutral position (a) and confirms severe narrowing when the head is rotated towards the right (red arrow, b).

Management

In patients with single patent vertebral artery with persistent symptoms and concern for impending stroke, management includes either open surgical intervention for vertebral artery decompression, vertebral fusion or minimally invasive endovascular methods involving coil embolization, and angioplasty with stenting. On the other hand, in patients with less severe and transient symptoms an individualized approach based on the etiology is recommended. Patients who opt for non-surgical management can be treated conservatively by antiplatelet therapy.102,104

Golfer’s stroke

Golfer’s stroke is characterized by recurrent cerebral infarctions secondary to craniocervical artery dissection associated with playing golf. 105 The repetitive rapid body and neck movement may result in torsional forces on the extracranial cervical arteries with each swing. 106 Specifically, various studies have discovered that the V3 segment of the vertebral artery is exposed without the support of bony structures and rotates freely during inadvertent head movement, rendering it the most susceptible during golf swing movements.107,108 In addition to dissection from mechanical shear, the extracranial vessels can get compressed by an elongated hyoid process, styloid process, or fibrous bands from the longus colli muscle.109–111

Imaging

Doppler ultrasound can demonstrate the location of arterial dissection, with the added advantage of being able to reproduce the compression by the hyoid bone in the rotated neck position. Doppler velocities may appear normal in the neutral position but decreased significantly with neck rotation, as in a golf swing.111,112 CT angiography of the neck in the neutral position can demonstrate close contact of the hyoid bone (usually greater horn) with the extracranial vasculature (Figure 10). CT angiography with the neck in a rotated position can demonstrate compression of the vasculature against the hyoid. 111 MRI of the brain demonstrates an embolic pattern of strokes with infarcts in the anterior or posterior circulation, particularly on the diffusion weighted images. 111 MR angiography can demonstrate intimal flaps within the dissected extracranial vessel or signal loss in the vessel related to compression. 111

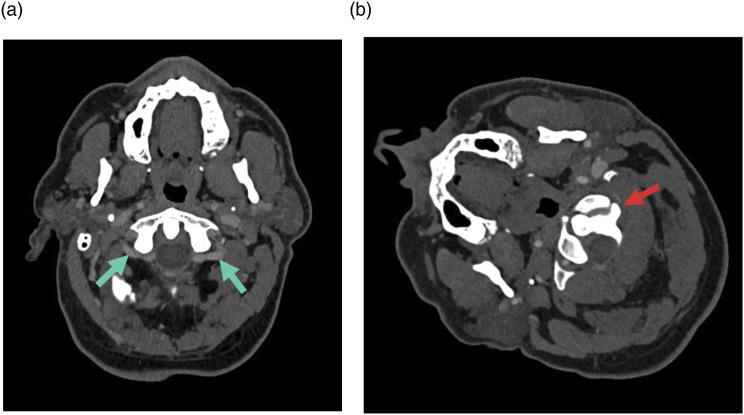

Figure 10.

A 57-year-old male (golfer) with multiple episodes of hemiparesis, tingling sensation and numbness in his left hand and face while playing golf. Axial CT angiogram of the neck (bone window) (a) and sagittal CT soft tissue of the neck (b) show compression of the right internal carotid artery (red arrow) by the right hyoid tubercle (yellow arrow and yellow circle).

Management

In addition to conservative management with antithrombotics,113,114 definitive treatment is resection of identified osseous offenders such an elongated styloid, enlarged greater horn of hyoid, osteophytic spurs, or decompression of fibrous bands.115,116 Other more invasive treatments include hemilaminectomy at the C1 level and C1-C2 posterior fusion.101,117

Eagle syndrome

This condition is characterized by pharyngeal pain, painful deglutition, referred otalgia, facial paresthesia, and symptoms of arterial compression secondary to elongation of the styloid process.118,119 Medial or lateral deviation of an elongated styloid process can compress the internal carotid artery or external carotid artery. 118 Symptoms may be either due to physical compression and reduced caliber of the affected vessel and/or irritation of the sympathetic nerve supply of the vascular wall. 118 Clinically, patients may present with local pain and tenderness (carotidynia) and pain in the distribution of the affected vessel. To elaborate, if the internal carotid artery is affected, then the patient may present with parietal headaches and pain in the distribution of the ophthalmic artery, without significant involvement caudal to the level of the eye. However, if the external carotid artery is involved, then the pain is usually referred to below the eye in the region supplied by various external carotid artery branches. 118 Furthermore, multiple recent reports of Eagle syndrome causing internal jugular venous stenosis have also been reported. 120 Specifically, the upper-third segment of the internal jugular vein is thought to be most susceptible to compression due to adjacent bony structures such as the styloid process and transverse process of C1. 120 Patients with venous compression present mainly with insomnia, hearing impairment, visual impairment and tinnitus. 120 Diagnosis of Eagle syndrome is made by both physical examination and imaging. Palpation of the elongated ossified styloid process in the tonsillar fossa should elicit and exacerbate the characteristic symptoms.118,121

Imaging

A panoramic radiograph may be used to determine if the styloid process is truly elongated. A length of 3 cm or longer in an adult is considered elongated (normal <2.5 cm). 121 In the absence of a panoramic radiograph, anteroposterior and posterior views of the skull should be obtained. The anteroposterior view is helpful to ascertain the presence of medial or lateral deviation of the styloid process. 121 Similarly, a CT of the neck is highly useful to evaluate both osseous and vascular detail in multiple planes and provides complementary information as that in the radiographs. 121 Furthermore, studies utilizing three-dimensional CT, three-dimensional angiography with near-infrared spectroscopy, and more recently three-dimensional virtual imaging have been reported for the diagnosis of symptomatic Eagle syndrome.122–124

Management

Although conservative management with analgesics, anticonvulsants, antidepressants have been tried, surgical treatment is the only effective treatment.125–127 Specifically, transoral and transcervical approach for resection of the elongated styloid process have been reported.125,126 Use of a piezoelectric cutting device to reduce the risk of transient marginal mandibular nerve injury with the transcervical approach has also been suggested. 127

Miscellaneous

Optic neuropathy

Compressive optic neuropathy is characterized by mass effect on the anterior visual pathway and is an infrequent cause of visual impairments. 128 Vascular compressions have been reported at the optic nerve and optic chiasm, 128 while the most common offenders include the internal carotid artery, anterior cerebral artery, posterior communicating artery, and rarely the ophthalmic artery and recurrent artery of Heubner. 128 Other lesions such as cerebral cavernous venous malformations (also called cavernous hemangiomas or cavernomas) affecting the anterior visual pathways, 129 meningiomas compressing the optic nerve, 130 and rarely an anterior clinoid mucocele causing compressive optic neuropathy have been reported. 131 Furthermore, progressive optic neuropathy caused by compression due to a prolapsing or herniated gyrus rectus has also been reported.132,133 The gyrus rectus is located at the very middle in the anterior cranial fossa, in close vicinity of the intracranial segment of the optic nerve and anterior part of the chiasm.132,133

Imaging

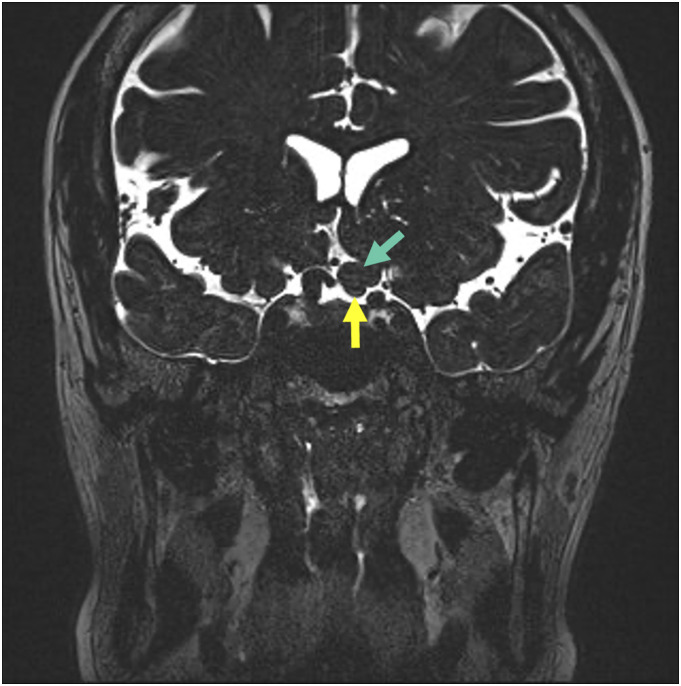

The ideal imaging modality is MRI of the brain, with heavily weighted T2 sequences showing the optic nerve in contact with the herniated or prolapsed gyrus rectus with distorted contour along the gyrus (Figure 11).132,133 In cases of neurovascular compression, the MRI can reveal indentation and mass effect of the optic chiasm or optic nerves by the culprit intracranial vessels. 134 The compressed optic nerve or chiasm demonstrates T2 hyperintensity while the unaffected contralateral side may be normal in signal intensity and caliber. 135

Figure 11.

51-year-old female with intermittent left eye visual obscurations and visual loss. Coronal high-resolution T2WI of the brain shows herniation of the left rectus gyrus (green arrow) on to the left optic nerve (yellow arrow).

Management

No definitive treatment exists for this rare condition. However, there are reports of MVD, anterior clinoidectomy, and optic canal unroofing that have shown benefit in this condition.4,136 However, if the process is chronic, MVD may not result in adequate symptom control due to fibrosed or degenerative nature of the nerve. 133 It is therefore imperative to identify these etiologies early to prevent permanent visual impairment.

Conclusion

High index of suspicion and optimal positioning for imaging is key in patients with compressive lesions of the head and neck. While a multimodality approach is critical in the evaluation of compressive lesions, an MRI utilizing high-resolution (heavily weighted) T2-weighted sequence is extremely useful as a starting point.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

George K Vilanilam https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0845-670X

Erik H Middlebrooks https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4418-9605

Alok A Bhatt https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3400-7123

References

- 1.Cruccu G, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS, et al. Trigeminal neuralgia: new classification and diagnostic grading for practice and research. Neurology 2016; 87: 220–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melzack R, Terrence C, Fromm G, et al. Trigeminal neuralgia and atypical facial pain: use of the McGill pain questionnaire for discrimination and diagnosis. Pain 1986; 27: 297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olesen J. Headache classification committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders. Cephalalgia 2018: 38: 1–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Ridder D, Sime MJ, Taylor P, et al. Microvascular decompression of the optic nerve for paroxysmal phosphenes and visual field deficit. World Neurosurg 2016; 85: 367.e5–367.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peker S, Kurtkaya Ö, Üzün I, et al. Microanatomy of the central myelin-peripheral myelin transition zone of the trigeminal nerve. Neurosurgery 2006; 59: 354–359; discussion 354-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antonini G, Di Pasquale A, Cruccu G, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging contribution for diagnosing symptomatic neurovascular contact in classical trigeminal neuralgia: a blinded case-control study and meta-analysis. Pain 2014; 155: 1464–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes MA, Frederickson AM, Branstetter BF, et al. MRI of the trigeminal nerve in patients with trigeminal neuralgia secondary to vascular compression. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2016; 206: 595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas K, Chang F-L, Vilensky J. The anatomy of vascular compression in trigeminal neuralgia (P07.051). Neurology 2013; 80: 7. (supp) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majoie CB, Verbeeten B, Dol JA, et al. Trigeminal neuropathy: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiographics 1995; 15: 795–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia M, Naraghi R, Zumbrunn T, et al. High-resolution 3D-constructive interference in steady-state MR imaging and 3D time-of-flight MR angiography in neurovascular compression: a comparison between 3T and 1.5T. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 1251–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leal PRL, Barbier C, Hermier M, et al. Atrophic changes in the trigeminal nerves of patients with trigeminal neuralgia due to neurovascular compression and their association with the severity of compression and clinical outcomes. J Neurosurg 2014; 120: 1484–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sirin S, Gonul E, Kahraman S, et al. Imaging of posterior fossa epidermoid tumors. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2005; 107: 461–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gass A, Kitchen N, MacManus DG, et al. Trigeminal neuralgia in patients with multiple sclerosis: lesion localization with magnetic resonance imaging. Neurology 1997; 49: 1142–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu R, Xie ME, Jackson CM. Trigeminal neuralgia: current approaches and emerging interventions. J Pain Res 2021; 14: 3437–3463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fariselli L, Marras C, De Santis M, et al. CyberKnife radiosurgery as a first treatment for idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery 2009; 64: A96–A101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blumenfeld A, Nikolskaya G. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2013; 17: 343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruyn GW. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Cephalalgia 1983; 3: 143–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banerjee C, Viers A, Vender J. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia/neuropathy with hemodynamic instability and associated syncope treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. World Neurosurg 2020; 139: 314–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burfield L, Ahmad F, Adams J. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia associated with cardiac syncope. BMJ Case Rep, 2016; 2016: bcr2015214104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanpolat Y, Unlu A, Savas A, et al. Chiari type I malformation presenting as glossopharyngeal neuralgia: case report. Neurosurgery 2001; 48: 226–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warren HG, Kotsenas AL, Czervionke LF. Trigeminal and concurrent glossopharyngeal neuralgia secondary to lateral medullary infarction. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006; 27: 705–707. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hiwatashi A, Matsushima T, Yoshiura T, et al. MRI of glossopharyngeal neuralgia caused by neurovascular compression. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008; 191: 578–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maki Y, Kikuchi T, Komatsu K, et al. Rare case of concurrent glossopharyngeal and trigeminal neuralgia, in which glossopharyngeal neuralgia was possibly induced by postoperative changes following microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. World Neurosurg 2019; 130: 150–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jani RH, Hughes MA, Ligus ZE, et al. MRI findings and outcomes in patients undergoing microvascular decompression for glossopharyngeal neuralgia. J Neuroimaging 2018; 28: 477–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.García Santos JM, Sánchez Jiménez S, Tovar Pérez M, et al. Tracking the glossopharyngeal nerve pathway through anatomical references in cross-sectional imaging techniques: a pictorial review. Insights Imaging 2018; 9: 559–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawashima M, Matsushima T, Inoue T, et al. Microvascular decompression for glossopharyngeal neuralgia through the transcondylar fossa (supracondylar transjugular tubercle) approach. Neurosurgery 2010; 66: 275–280; discussion 280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma Y, Li YF, Wang QC, et al. Neurosurgical treatment of glossopharyngeal neuralgia: analysis of 103 cases. J Neurosurg 2016; 124: 1088–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kosary IZ, Ouaknine G. Surgical treatment of glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Harefuah 1972; 83: 484–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rey-Dios R, Cohen-Gadol AA. Current neurosurgical management of glossopharyngeal neuralgia and technical nuances for microvascular decompression surgery. Neurosurg Focus 2013; 34: E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams BJ, Schlesinger D, Sheehan J. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia treated with gamma knife radiosurgery. World Neurosurg 2010; 73: 413–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanpolat Y, Savas A, Batay F, et al. Computed tomography-guided trigeminal tractotomy-nucleotomy in the management of vagoglossopharyngeal and geniculate neuralgias. Neurosurgery 1998; 43: 484–489; discussion 490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yomo S, Arkha Y, Donnet A, et al. Gamma knife surgery for glossopharyngeal neuralgia: report of 2 cases. J Neurosurg 2009; 110: 559–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clift JM, Wong RD, Carney GM, et al. Radiographic analysis of cochlear nerve vascular compression. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2009; 118: 356–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cerrato P, Bergui M, Imperiale D, et al. Occipital neuralgia as isolated symptom of an upper cervical cavernous angioma. J Neurol 2002; 249: 1464–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White JB, Atkinson PP, Cloft HJ, et al. Vascular compression as a potential cause of occipital neuralgia: a case report. Cephalalgia 2008; 28: 78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma RR, Parekh HC, Prabhu S, et al. Compression of the C-2 root by a rare anomalous ectatic vertebral artery: case report. J Neurosurg 1993; 78: 669–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim K, Mizunari T, Kobayashi S, et al. Occipital neuralgia caused by the compression of the fenestrated vertebral artery: a case report. No Shinkei Geka 1999; 27: 645–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jundt JW, Mock D. Temporal arteritis with normal erythrocyte sedimentation rates presenting as occipital neuralgia. Arthritis Rheum 1991; 34: 217–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robinson IS, Salibian AA, Alfonso AR, et al. Surgical management of occipital neuralgia: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Plast Surg 2021; 86: S322–S331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ehni G, Benner B. Occipital neuralgia and the C1-2 arthrosis syndrome. J Neurosurg 1984; 61: 961–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Samii M, Jannetta PJ. The cranial nerves: anatomy·pathology·pathophysiology·diagnosis·treatment. New York: Springer Science & Business Media, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jannetta PJ, Abbasy M, Maroon JC, et al. Etiology and definitive microsurgical treatment of hemifacial spasm. Operative techniques and results in 47 patients. J Neurosurg 1977; 47: 321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tash RR, Kier EL, Chyatte D. Hemifacial spasm caused by a tortuous vertebral artery: MR demonstration. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1988; 12: 492–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Campos-Benitez M, Kaufmann AM. Neurovascular compression findings in hemifacial spasm. J Neurosurg 2008; 109: 416–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barona L, Krstulovic C, Bejarano B, et al. Vestibular impairment in hemifacial spasm syndrome: a case report. J Int Adv Otol 2020; 16: 138–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryu H, Yamamoto S, Sugiyama K, et al. Hemifacial spasm caused by vascular compression of the distal portion of the facial nerve. Report of seven cases. J Neurosurg 1998; 88: 605–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fukuda M, Kameyama S, Honda Y, et al. Hemifacial spasm resulting from facial nerve compression near the internal acoustic meatus--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1997; 37: 771–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sobel D, Norman D, Yorke CH, et al. Radiography of trigeminal neuralgia and hemifacial spasm. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1980; 135: 93–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Digre KB, Corbett JJ, Smoker WR, et al. CT and hemifacial spasm. Neurology 1988; 38: 1111–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carlos R, Fukui M, Hasuo K, et al. Radiological analysis of hemifacial spasm with special reference to angiographic manifestations. Neuroradiology 1986; 28: 288–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tash R, DeMerritt J, Sze G, et al. Hemifacial spasm: MR imaging features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1991; 12: 839–842. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hertz R, Espinosa J, Lucerna A, et al. Multiple sclerosis presenting with facial twitching (myokymia and hemifacial spasms). Case Rep Neurol Med 2017; 2017: 7180560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gupta S, Mends F, Hagiwara M, et al. Imaging the facial nerve: a contemporary review. Radiol Res Pract 2013; 2013: 248039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Defazio G, Abbruzzese G, Girlanda P, et al. Botulinum toxin a treatment for primary hemifacial spasm: a 10-year multicenter study. Arch Neurol 2002; 59: 418–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sekula RF, Frederickson AM, Arnone GD, et al. Microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm in patients >65 years of age: an analysis of outcomes and complications. Muscle Nerve 2013; 48: 770–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lekskul A, Wuthisiri W, Tangtammaruk P. The etiologies of isolated fourth cranial nerve palsy: a 10-year review of 158 cases. Int Ophthalmol 2021; 41: 3437–3442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marinković S, Gibo H, Zelić O, et al. The neurovascular relationships and the blood supply of the trochlear nerve: surgical anatomy of its cisternal segment. Neurosurgery 1996; 38: 161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prosst RL, Majetschak M. Traumatic unilateral trochlear nerve palsy. J Trauma 2007; 62: E1–E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yasargil MG. Microneurosurgery. Stuttgart: Ceorg Thieme, 1987, pp. 161–164. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Graf M. Diagnose und Therapie der Trochlearisparese. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 2009; 226: 806–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Son S, Park CW, Yoo CJ, et al. Isolated, contralateral trochlear nerve palsy associated with a ruptured right posterior communicating artery aneurysm. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2010; 47: 392–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Choi BS, Kim JH, Jung C, et al. High-resolution 3D MR imaging of the trochlear nerve. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010; 31: 1076–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bunch PM, Kelly HR, Zander DA, et al. Trochlear groove and trochlear cistern: useful anatomic landmarks for identifying the tentorial segment of cranial nerve IV on MRI. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017; 38: 1026–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ohtsuka K, Sone A, Igarashi Y, et al. Vascular compressive abducens nerve palsy disclosed by magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Ophthalmol 1996; 122: 416–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tega J, Kobayashi H, Kozaki Y, et al. Microvascular decompression to treat abducens nerve paralysis caused by compression of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery: a case report. No Shinkei Geka 2020; 48: 429–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smoker WRK, Corbett JJ, Gentry LR, et al. High-resolution computed tomography of the basilar artery. II. Vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia: clinical-pathologic correlation and review. Am J Neuroradiol 1986; 7: 61–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mamata Y, Muro I, Matsumae M, et al. Magnetic resonance cisternography for visualization of intracisternal fine structures. J Neurosurg 1998; 88: 670–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Miyamoto S, Matsuda M, Ishikawa E, et al. Microvascular decompression for abducens nerve palsy due to neurovascular compression from both the vertebral artery and anterior inferior cerebellar artery: a case report. Surg Neurol Int 2020; 11: 242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miller NR. The ocular motor nerves. Curr Opin Neurol 1996; 9: 21–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Donaldson D, Rosenberg NL. Infarction of abducens nerve fascicle as cause of isolated sixth nerve palsy related to hypertension. Neurology 1988; 38: 1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Berlit P, Reinhardt-Eckstein J, Krause KH. Die isolierte Abdunzensparese - Eine retrospektive Studie an 165 Patienten. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 1989; 57: 32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vaphiades MS, Roberts BW. Abducens nerve palsy from an occult high flow carotid cavernous fistula. Am Orthopt J 2004; 54: 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sadashiva N, Shukla D. Neurovascular conflict of abducent nerve. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2017; 8: 3–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Choudhari KA. Isolated abducent nerve palsy after microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia: case report. Neurosurgery 2005; 57: E1317; discussion E1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kutty RK, Yamada Y, Takizawa K, et al. Medullary compression due to ectatic vertebral artery—case report and review of literature. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2020; 29: 104460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Savitz SI, Ronthal M, Caplan LR. Vertebral artery compression of the medulla. Arch Neurol 2006; 63: 234–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Žižka J, Ceral J, Eliáš P, et al. Vascular compression of rostral medulla oblongata: prospective MR imaging study in hypertensive and normotensive subjects. Radiology 2004; 230: 65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tanrikulu L, Hastreiter P, Richter G, et al. Virtual neuroendoscopy: MRI-based three-dimensional visualization of the cranial nerves in the posterior cranial fossa. Br J Neurosurg 2008; 22: 207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Leal PRL, Hermier M, Froment JC, et al. Preoperative demonstration of the neurovascular compression characteristics with special emphasis on the degree of compression, using high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging: a prospective study, with comparison to surgical findings, in 100 consecutive patients who underwent microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2010; 152: 817–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ross JS. The high-field-strength curmudgeon. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004; 25: 168–169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stobo DB, Lindsay RS, Connell JM, et al. Initial experience of 3 Tesla versus conventional field strength magnetic resonance imaging of small functioning pituitary tumours. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011; 75: 673–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Naraghi R, Hastreiter P, Tomandl B, et al. Three-dimensional visualization of neurovascular relationships in the posterior fossa: technique and clinical application. J Neurosurg 2004; 100: 1025–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Manava P, Naraghi R, Schmieder R, et al. 3D-Visualization of neurovascular compression at the ventrolateral medulla in patients with arterial hypertension. Clin Neuroradiol 2021; 31: 335–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fliegel BE, Menezes RG. Anatomy, Thorax, Cervical Rib. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing, 2020, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31082045 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chang KZ, Likes K, Davis K, et al. The significance of cervical ribs in thoracic outlet syndrome. J Vasc Surg 2013; 57: 771–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Viertel VG, Intrapiromkul J, Maluf F, et al. Cervical ribs: a common variant overlooked in CT imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 2191–2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Henry BM, Vikse J, Sanna B, et al. Cervical rib prevalence and its association with thoracic outlet syndrome: a meta-analysis of 141 studies with surgical considerations. World Neurosurg 2018; 110: e965–e978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sanders RJ, Hammond SL, Rao NM. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a review. Neurologist 2008; 14: 365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Raptis CA, Sridhar S, Thompson RW, et al. Imaging of the patient with thoracic outlet syndrome. RadioGraphics 2016; 36: 984–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chen H, Doornbos N, Williams K, et al. Physiologic variations in venous and arterial hemodynamics in response to postural changes at the thoracic outlet in normal volunteers. Ann Vasc Surg 2014; 28: 1583–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Demondion X, Vidal C, Herbinet P, et al. Ultrasonographic assessment of arterial cross-sectional area in the thoracic outlet on postural maneuvers measured with power Doppler ultrasonography in both asymptomatic and symptomatic populations. J Ultrasound Med 2006; 25: 217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Demondion X, Bacqueville E, Paul C, et al. Thoracic outlet: assessment with MR imaging in asymptomatic and symptomatic populations. Radiology 2003; 227: 461–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gillet R, Teixeira P, Meyer J-B, et al. Dynamic CT angiography for the diagnosis of patients with thoracic outlet syndrome: correlation with patient symptoms. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2018; 12: 158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Khalilzadeh O, Glover M, Torriani M, et al. Imaging assessment of thoracic outlet syndrome. Thorac Surg Clin 2021; 31: 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Demirbag D, Unlu E, Ozdemir F, et al. The relationship between magnetic resonance imaging findings and postural maneuver and physical examination tests in patients with thoracic outlet syndrome: results of a double-blind, controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88: 844–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hawks C, Herrera-Nicol S, Pruzansky ME, et al. Minimally invasive resection of symptomatic cervical rib for treatment of thoracic outlet syndrome. World Neurosurg 2020; 139: 219–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Duan G, Xu J, Shi J, et al. Advances in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of Bow Hunter’s syndrome: a comprehensive review of the literature. Interv Neurol 2016; 5: 29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Regenhardt RW, Kozberg MG, Dmytriw AA, et al. Bow Hunter’s syndrome. Stroke 2022; 53: E26–E29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Choi KD, Choi JH, Kim JS, et al. Rotational vertebral artery occlusion: mechanisms and long-term outcome. Stroke 2013; 44: 1817–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Montano M, Alman K, Smith MJ, et al. Bow Hunter’s syndrome: a rare cause of vertebrobasilar insufficiency. Radiol Case Rep 2021; 16: 867–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shimizu T, Waga S, Kojima T, et al. Decompression of the vertebral artery for bow-hunter’s stroke: case report. J Neurosurg 1988; 69: 127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zaidi HA, Albuquerque FC, Chowdhry SA, et al. Diagnosis and management of bow hunter’s syndrome: 15-year experience at barrow neurological institute. World Neurosurg 2014; 82: 733–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Taylor WB, Vandergriff CL, Opatowsky MJ, et al. Bowhunter’s syndrome diagnosed with provocative digital subtraction cerebral angiography. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2012; 25: 26–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Strickland BA, Pham MH, Bakhsheshian J, et al. Bow Hunter’s syndrome: surgical management (video) and review of the literature. World Neurosurg X 2017; 103: 953.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Maroon JC, Gardner P, Abla AA, et al. ‘Golfer’s stroke’: golf-induced stroke from vertebral artery dissection. Surg Neurol 2007; 67: 163–168; discussion 168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Thériault G, Lachance P. Golf injuries: an overview. Sports Med 1998; 26: 43–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sherman DG, Hart RG, Easton JD. Abrupt change in head position and cerebral infarction. Stroke 1981; 12: 2–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Schievink WI. Spontaneous dissection of the carotid and vertebral arteries. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 898–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mapstone T, Spetzler RF. Vertebrobasilar insufficiency secondary to vertebral artery occlusion from a fibrous band. Case report. J Neurosurg 1982; 56: 581–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Renard D, Azakri S, Arquizan C, et al. Styloid and hyoid bone proximity is a risk factor for cervical carotid artery dissection. Stroke 2013; 44: 2475–2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Liu G, Wang Y, Chu C, et al. Hyoid elongation may be a rare cause of recurrent ischemic stroke in youth-A case report and literature review. Front Neurol 2021; 12: 653471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Choi MH, Hong JM, Lee JS, et al. Preferential location for arterial dissection presenting as golf-related stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 323–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.TISSINGTON TATLOW WF, BAMMER HG. Syndrome of vertebral artery compression. Neurology 1957; 7: 331–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Markus HS, Levi C, King A, et al. Antiplatelet therapy vs anticoagulation therapy in cervical artery dissection: the cervical artery dissection in stroke study (cadiss) randomized clinical trial final results. JAMA Neurol 2019; 76: 657–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Okawara S, Nibbelink D. Vertebral artery occlusion following hyperextension and rotation of the head. Stroke 1974; 5: 640–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sheehan S, Bauer RB, Meyer JS. Vertebral artery compression in cervical spondylosis: arteriographic demonstration during life of vertebral artery insufficiency due to rotation and extension of the neck. Neurology 1960; 10: 968. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Matsuyama T, Morimoto T, Sakaki T. Comparison of C1-2 posterior fusion and decompression of the vertebral artery in the treatment of bow hunter’s stroke. J Neurosurg 1997; 86: 619–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.EAGLE WW. Symptomatic elongated styloid process; report of two cases of styloid process-carotid artery syndrome with operation. Arch Otolaryngol 1949; 49: 490–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kaz’mierski R, Wierzbicka M, Kotecka-Sowinska E, et al. Expansion of the classification system for eagle syndrome. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168: 746–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bai C, Wang Z, Guan J, et al. Clinical characteristics and neuroimaging findings in eagle syndrome induced internal jugular vein stenosis. Ann Transl Med 2020; 8: 97–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Murtagh RD, Caracciolo JT, Fernandez G. CT findings associated with eagle syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2001; 22: 1401–1402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Beder E, Ozgursoy OB, Karatayli Ozgursoy S, et al. Three-dimensional computed tomography and surgical treatment for Eagle’s syndrome. Ear, Nose Throat J 2006; 85: 443–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Nakagawa D, Ota T, Iijima A, et al. Diagnosis of eagle syndrome with 3-dimensional angiography and near-infrared spectroscopy: Case report. Neurosurgery 2011; 68: E847–E849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Nastro Siniscalchi E, Mormina E, Cicchiello S, et al. Can a 3D virtual imaging model predict Eagle syndrome? Appl Sci (Basel) 2022; 12: 4564. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Papadiochos I, Papadiochou S, Sarivalasis ES, et al. Treatment of Eagle syndrome with transcervical approach secondary to a failed intraoral attempt: surgical technique and literature review. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 2017; 118: 353–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Beder E, Ozgursoy OB, Karatayli Ozgursoy S. Current diagnosis and transoral surgical treatment of eagle’s syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005; 63: 1742–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Bertossi D, Albanese M, Chiarini L, et al. Eagle syndrome surgical treatment with piezosurgery. J Craniofac Surg 2014; 25: 811–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Tsutsumi S, Ono H, Yasumoto Y. Vascular compression of the anterior optic pathway: a rare occurrence? Can Assoc Radiol J 2017; 68: 409–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Lehner M, Fellner FA, Wurm G. Cavernous haemangiomas of the anterior visual pathways. Short review on occasion of an exceptional case. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2006; 148: 571–578; discussion 578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hénaux PL, Bretonnier M, Le Reste PJ, et al. Modern management of meningiomas compressing the optic nerve: a systematic review. World Neurosurg 2018; 118: e677–e686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Thurtell MJ, Besser M, Halmagyi GM. Anterior clinoid mucocele causing acute monocular blindness. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2007; 35: 675–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Smith J, Jack MM, Peterson JC, et al. Herniated gyrus rectus causing idiopathic compression of the optic chiasm. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2017; 153: 79–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Nishioka T, Okumura R, Ishikawa M, et al. Prolapsing gyrus rectus as a cause of progressive optic neuropathy. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2000; 40: 301–307; discussion 307-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Freeman JY, Newman NJ. Carotid artery compression of the optic nerve. Ophthalmology 2000; 107: 1798–1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Eurorad . Idiopathic herniation of gyrus rectus – a rare cause of sudden monocular vision loss. https://www.eurorad.org/case/16364 (accessed 3 November 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 136.Woodall MN, Alleyne CHJ. Teaching neuroimages: microvascular decompression of the optic nerve. Neurology 2013; 81: e137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]