Abstract

Background and Aims

Thromboembolism complication is considered the most common complication associated with the treatment of endovascular. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to assess the studies investigating the effect of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor agents on thromboembolic complications during endovascular aneurysm coiling.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review investigated the outcome of the use of three glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor agents (ie abciximab, tirofiban, and eptifibatide) on the thromboembolic complications during endovascular aneurysm coiling. The electronic databases of PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Medline were searched up to 25 June 2021, using the keywords “Abciximab,” “Tirofiban,” and “Eptifibatide” incombination with “Thromboembolism Complication,” “Aneurysms,” and “Endovascular Aneurysm Coiling.”

Results

A total of 21 articles were found to be eligible and included in this review. The rates of complete and partial recanalization were estimated to be 56% and 92% in patients who underwent abciximab and tirofiban therapy, respectively. Rupture aneurysms were found in the majority of patients. In general, the mortality rate of the patients treated for thromboembolic complications during endovascular treatment of cerebral aneurysms with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors was found to be 4.8% (CI 95%:0.027–0.067; p < .005). The average remission rate in studies investigating thromboembolism was 91% (CI 95%:0.88–0.95, I2 : 65.65/p < .001).

Conclusion

Based on the obtained results, a higher mean rate of complete recanalization by eptifibatide was found in studies in which abciximab or tirofiban were used, compared to other mentioned agents. Moreover, the amount of hemorrhage was reported to be less after using tirofiban rather than abciximab.

Keywords: Abciximab, cerevral aneurysm, eptifibatide, tirofiban

Introduction

Thromboembolism complication is considered the most common complication associated with the endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms with detachable coils.1,2

Aneurysm ruptures can lead to subarachnoid hemorrhage while unruptured aneurysms are asymptomatic in the majority of cases. However, symptoms caused by mass effect are reported in unruptured aneurysms. Therefore, there is a rupture risk, even for small aneurysms. The rate of symptomatic intracranial aneurysms has been estimated to be 10–15% in all intracranial aneurysms.3,4 Based on the literature, the risk of rupture is 0.05% per year in patients with an aneurysm smaller than 10 mm and without a history of subarachnoid hemorrhage, while it is 1% among patients with aneurysms bigger than 10 mm. 5 Moreover, the incidence of thromboembolic complications during endovascular aneurysm coiling ranged between 6.7% and 28%.2,6–8

The displacement of pre-existing intra-aneurysmal thrombus may occur during coil placement. Furthermore, a new thrombus may be formed on the catheters during intervention or in the coil surface due to temporary stenosis of an adjacent artery caused by coil herniation. 9 Since thromboembolism may lead to permanent deficits, its treatment should be considered. 8

Local or systemic thrombolytic medications are effective in the control of thromboembolism. Intravenous (IV) heparin is the standard treatment for acute thrombus formation during coil placement. However, the desired optimal results are not obtained by this treatment approach. Urokinase or recombinant tissue plasminogen activator are utilized for thrombus formation. Nevertheless, it often results in severe rebleeding at the aneurysm site. 10

The simple route of administration and the short half-life of the drug are two main important issues that should be taken into account in this regard. 9 Urokinase, tissue plasminogen activator and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors are the most common thrombolytic agents.11–14 Abciximab, tirofiban, and eptifibatide are three antiplatelet drugs of the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor class, and IV abciximab is used to dissolve hyperacute thrombi. 14 However, few studies, including small case series, have assessed the effect of intra-arterial (IA) abciximab in thromboembolic complications during endovascular aneurysm coiling. Eptifibatide and tirofiban are the other glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors, which have been recently used to resolve and/or prevent thromboembolic complications during endovascular aneurysm coiling.

This study analyzed all studies assessing the effect of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor agents on thromboembolic complications during endovascular aneurysm coiling. Moreover, this systematic review focused on the success rate of IA or IV administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors and the recanalization of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors for thromboembolic complications during coiling the aneurysms. We also aimed to consider the administered dosage and half-life of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, the prevalence of hemorrhage, and thrombocytopenia after using these inhibitors.

Materials and methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis assessed the outcome of the use of three glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor agents (ie abciximab, tirofiban, and eptifibatide) on the thromboembolic complications during endovascular aneurysm coiling. Moreover, according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions meta-analysis, this study followed eight stages including the assessment of the eligible criteria, data collection (using electronic databases), exclusion of unrelated articles, review of the quality assessment, data extraction, and analysis of the collected data. 15

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria were determined according to the PICOS method (participants, intervention, comparison, outcome, and study design). The inclusion criteria were English-written case-control, prospective, and retrospective studies on human subjects that assessed the effects of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor agents on thromboembolic complications during coil embolization in cerebral aneurysms. However, in-vitro and animal studies, meta-analyses, reviews, narrative articles, short communications, editorial letters and qualitative investigations, were excluded from this study.

Review of the literature

Based on inclusion/exclusion criteria, all articles published from 30 May to 25 June 2021, were searched in the PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Embase electronic databases using the keywords “Abciximab,” “Tirofiban,” and “Eptifibatide” in combination with “Thromboembolism Complication,” “Aneurysms,” and “Endovascular Aneurysm Coiling” and the application of appropriate Booleans and wildcards.

Study design and data extraction

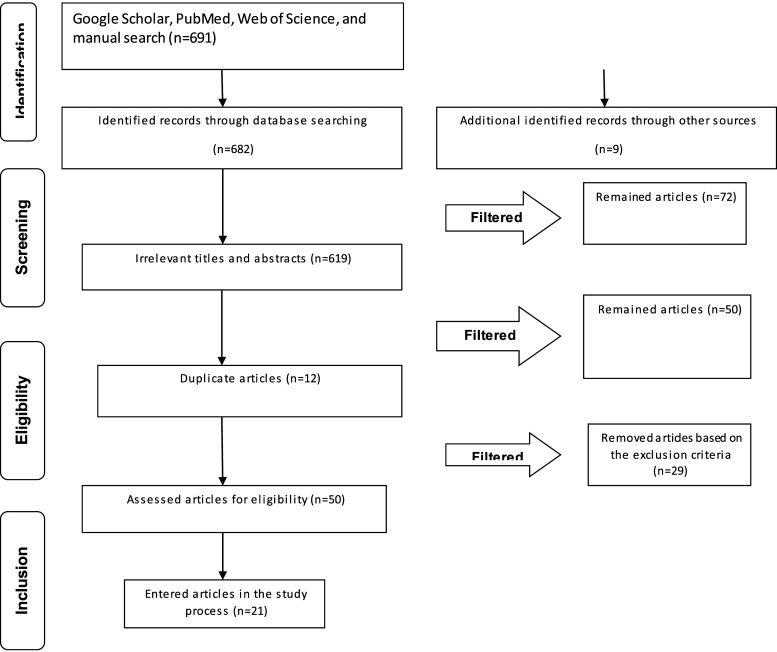

Initially, the duplicate studies were removed from the extracted articles. In the next stage, the titles and abstracts of the papers were reviewed based on the eligibility criteria in order to exclude the irrelevant ones. The search process was conducted by two researchers, independently. They studied the titles and abstracts of all papers separately. It should be noted that the researchers agreed on the eligibility criteria. In the final evaluation, the researchers reviewed the full-text versions of the selected articles and excluded the papers with insufficient data, studies with no focus on the research objective, and studies without inclusion criteria. The researchers agreed on the selection of the included studies, as well as the data extraction and exchange process, otherwise, the third researcher intervened to resolve the disagreements. The PRISMA flow chart presents the stages in the selection of the articles (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart representing the process of paper selection in the review.

Quality assessment

Cochrane’s risk of bias tool was employed to assess the risk of bias for each study. Accordingly, the selected papers were assessed in terms of eight bias domains, including bias due to confounders, selection of sample size, assessment of the intervention, missing data, selective reporting, outcome, a departure from the intended intervention, and other possible biases. 16 The low, high, and unknown items were considered for risks of bias and were marked as “Yes,” “No,” and “Unclear,” respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Quality assessment of included articles in the review process.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (version 2.2, Biostat Inc.). The meta-analysis was performed in the case the outcome was reported in two or more studies. We estimated the event rate and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each outcome in all studies. Heterogeneity across studies was estimated using the I2 statistic and substantial heterogeneity was defined as I2 > 50%. The random effects model was used in the case of high heterogeneity. The sensitivity analyses were performed by sequentially omitting each individual study to assess the stability of the pooled results. A p-value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Out of 691 articles found in the search process, 619 studies were removed due to their irrelevance to the research objectives. Moreover, out of 72 remaining articles, 12 were excluded due to duplicability. Moreover, technical notes (n = 2), editorial letters (n = 2), books (n = 1), reviews and narrative reviews (n = 9), unavailable full texts (n = 2), and the studies focused on other thrombolytics, except for glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor agents (i.e., abciximab, tirofiban, and eptifibatide) (n = 24), were also excluded from the study. Eventually, 21 original studies were eligible to be included in this review.

The majority (76%) of the studies was case series, and 10 (24%) studies were retrospective reviews.

The included studies contained data from 561 patients with thrombus formation complicating aneurysm coiling. The mean age range of the patients was 49–68 years and the female/male ratio was 60:40. It is worth noting that 32%–84% of patients in these studies were diagnosed with a ruptured aneurysm. A total of nine studies were performed only on patients with ruptured aneurysms, while only one case study reported a patient with unruptured aneurysms. Moreover, the aneurysm size in these studies ranged between 2 and 25 mm. Abciximab and tirofiban were administered to patients in 14 (67%) and four (19%) studies. However, only two (10%) studies reported the administration of eptifibatide for thromboembolic events related to endovascular treatment of cerebral aneurysms. One study compared abciximab and tirofiban and the administered dosage of abciximab for thromboembolism during coil embolization of cerebral aneurysms, based on the route of administration (ie IA, IV, or combined). Table 1 tabulates the extracted data in detail, and the risk of bias in the included studies is illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Extracted data obtained from the included studies.

| Author (year) Reference | Country | Type of study | Sample size | Age | Male/Female ratio | Type of aneurysms | Aneurysm size | Type of agent | Type of surgery | Dosage (mg) | Location of Aneurysm | External agent | Angiographic recanalization | Complication | Subarachnoid hemorrhage | Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mounayer et al. 17 (2003) | Case series | France | 13 | 49 (40–61) | 8/5 | Rupture aneurysms | — | Abciximab | Coiling/stent | 4–10 mg over a period of 10–20 min 0–54-0.125 mg/Kg | AcoA a : 5 | Heparin | CR f : 92% | No abciximab-related intracranial hemorrhages | — | One patient |

| MCA b :3 | PR g : One case (8%) | |||||||||||||||

| ICA c :2 | ||||||||||||||||

| PcoA d :1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Supra ICA e :1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Basilar tip:1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Aggour et al. (2010) 1 | Case series | France | 23 | (27–74) | 11/12 | Rupture aneurysms | — | Abciximab | Coiling/stent | IA h : 5 mg abciximab delivered over 5–10 min (maximum dose of 0.25 mg/kg) | MCA: 9 | Heparin | CR: 13 (56.5%) | No hemorrhagic complications | — | No |

| IV i : 0.125 mg/kg/min for 12 h | ACA j :4 | PR: 17.4% | Ischemic lesions: 11 (47.8%) | |||||||||||||

| ACA/MCA:1 | ||||||||||||||||

| MCA/ICA:1 | ||||||||||||||||

| ICA:1 | ||||||||||||||||

| PCA k :2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Pericallosal: 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| M1 l and bilateral A2 m :2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Martínez-Pérez et al. 18 | Case series | Canada | 14 | 56.5 (48–76) | 3/11 | Rupture aneurysms | 5–14 mm | Abciximab | Coiling procedure | A bolus of 2–5 mg over 2 min | Acom n :8 | Heparin | CR:4 (28%) | Rupture and bleeding: 1 | 7 | One patient |

| IA: a Maximum dose of 0.25 mg/kg | MCA:3 | PR:9 (64%) | Distal thrombus: 4 (57%) | |||||||||||||

| IV 0.125 mg/kg/min | Basilar:3 | No: 1 (7%) | ||||||||||||||

| Jones et al. (2008) 19 | Case series | UK | 38 | 54 (29–81) | 17/21 | 84% had rupture aneurysms | — | Abciximab | Coiling procedure | A bolus of 0.25 mg/kg reduced to 0.125 mcg/kg per minute | AC o : 34 (89%) | Heparin | Good outcome: 30 (79%) | No rebleeding post-abciximab administration | 2 | One patient |

| PC p : 4 (11%) | Poor outcome: 8 (21%) | |||||||||||||||

| Fiorella et al. (2003) 13 | Case series | USA | 13 | 50 (28–31) | — | Rupture aneurysms | — | Abciximab | Coiling/stent/balloon | Intravenously as a 0.125–0.25 mg/kg bolus followed by a 12-h | — | Heparin | CR: 53% | No hemorrhaging | 2 | No |

| Intra-arterial abciximab (3.5–10 mg) | PR: 47% | Small infarcts: 5 | ||||||||||||||

| Gralla et al. (2008) 20 | Retrospective | Switzerland | 63 | 55.3 | 24/39 | Both rupture and unrupture aneurysms | 4 mm | Abciximab | Coiling/stent/balloon | 12.7 mg (range 2–30,±5.6) | Acom:27 (42%) | Heparin | CR: 68.3% | No haemorrhagic complications | 2 | 2 patients |

| MCA: 12 (19%) | PR: 19.5% | Large and symptomatic groin hematoma: 2 (3.2%) | ||||||||||||||

| Basilar artery: 11 (17.5%) | No:12.5% | |||||||||||||||

| Pcom q : 4 (6.3%) | ||||||||||||||||

| PA r : 3(4.8%) | ||||||||||||||||

| ICA: 3(4.8%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Pica: 2 (3.2%) | ||||||||||||||||

| PCA: 1 (2.6%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Linfante et al. (2015) 21 | Retrospective | USA | 19 | 52 (25–83) | 5/14 | Both rupture and unrupture aneurysms | 6.6 mm | Abciximab | Coiling/stent/balloon | Dose of IA was 10.5 mg | Acom: 7 | Heparin | Complete or partial: 100% | No periprocedural hemorrhagic complications | 2 | 2 patients |

| MCA 5 | ||||||||||||||||

| ACA: 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Basilar artery: 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Pcom: 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Vertebral artery: 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| ICA:1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Ries et al. (2009) 22 | Germany | Case series | 48 | 50 (28–75) | 16/32 | Both rupture and unrupture aneurysms | 2–25 mm | Abciximab | Coiling/stent/balloon | IV or IA with a standard bolus of 0.25 mg/Kg of body weigh | Acom: 12 | Heparin | CR | No extra cerebral bleeding complications infarct: 31% | — | 3 patients |

| Pcom:5 | 14.3% | Complete infarction: 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Basilar artery:11 | PR | |||||||||||||||

| PAA s :5 | 59.5% | |||||||||||||||

| ICA:1 | ||||||||||||||||

| A1/A2 segment; 5 | ||||||||||||||||

| OAA t :6 | ||||||||||||||||

| Park et al. (2008) 23 | Korea | Retrospective | 13 | 54 (25–85) | 8/23 | Rupture aneurysms | 3–24 mm | Abciximab | Coiling procedure | 0.2 mg/mL as a bolus of 4–15 mg over a period of 15–30 min | Acom: 15 (46.9) | Heparin | CR: 17 (53%) | Post-procedural rebleeding:3 | 3 | 2 patients |

| MCA: 8 (25.0) | PR: 15 (46.9) | |||||||||||||||

| PCoA: 3 (9.4) basilar artery:2 (6.2) | ||||||||||||||||

| ACA; (6.2) | ||||||||||||||||

| Paraclinoid: 2 (6.2) | ||||||||||||||||

| Velat et al. (2006) 24 | USA | Case series | 29 | 58 (30–76) | 5/24 | Both rupture and unrupture aneurysms | — | Abciximab | Coiling/stent/balloon | A bolus of 0.25 mg/kg followed by a 12 h intravenous infusion (0.125 lg/kg per minute) | MCA:15 | Heparin | CR: 61% | Three intracranial hemorrhages secondary to a small dissection | — | 2 patients |

| PCA:11 | PR: 19 | |||||||||||||||

| ICA:2 | ||||||||||||||||

| ACA:1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Aviv et al. (2005) 25 | Canada | Case series | 13 | 56 (28–79) | 5/8 | Rupture aneurysms | 2–15 mm | Abciximab | Coiling/stent/balloon | 5–20 mg | Acom: 5 | Heparin | CR: 8 (62%) | Transient hemiparesis:3 | 1 | One patient |

| Pcom:5 | PR: 5 (38%) | Infarct:3 | ||||||||||||||

| Basilar tip:1 | Rupture:1 | |||||||||||||||

| MCA:1 | Shunt/haematoma evacuation:1 | |||||||||||||||

| Pica:1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Gentric et al. (2015) 26 | USA | Retrospective | 51 | 68 (66.6, 42–94) | 22/29 | Rupture aneurysms | 4–10 mm | Abciximab | Coiling procedure | 0.25 mg/kg followed by a 12 h IV infusion (0.125 mg/kg/min) | — | Heparin | — | Bleeding: Four patients (9.5%) | 10 | 3 patients |

| Significant peripheral bleeding: 2 (4.8%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Bruening et al. (2006) 27 | Germany | Case series | 16 | 52.9 (35–77) | 10/6 | Rupture aneurysms | 3–18 mm | Tirofiban | Coiling procedure | 0.4 mg/kg/min for 30 min reduced to 0.1 mg/kg/min | ACA: 7 cases | Heparin | CR: 8 (50%) | No major hemorrhagic complications | All | 2 patients |

| ICA: 2 | PR: 1 (6%) | |||||||||||||||

| Pcom: 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| MCA: 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| PC: 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Kang et al. (2008) 28 | Korea | Case series | 25 | 52 (23–73) | 18/7 | 56% had rupture aneurysms | — | Tirofiban | Coiling/stent/balloon | 0.2–1.0 mg | ACA: 12 | Heparin | CR and PR: 96% | No hemorrhagic complication related to tirofiban infusion | 2 | — |

| ICA: 7 | ||||||||||||||||

| ACA: 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Pcom: 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Paraclinoid 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| MCA: 4 | ||||||||||||||||

| Basilar artery: 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Cho et al. (2012) 29 | Korea | Retrospective | 39 | 54.7 | 16/23 | Rupture aneurysms | 2–13 mm | Tirofiban | Coiling/stent/balloon | 0.5–0.75 mg | Acom: 15 (38) | Heparin | CR: 7 (17%) | Intracerebral hemorrhage: 2 | 1 | 2 patients |

| MCA: 9 (23) | PR: 24 (61%) | |||||||||||||||

| Pcom: 7 (18) | No progression or response: 8 (20%) | |||||||||||||||

| ICA” 6 (15) | ||||||||||||||||

| ACA:1 (3) | ||||||||||||||||

| Pica: 1 (3) | ||||||||||||||||

| Kim et al. (2016) 30 | Korea | Retrospective | 20 | 55 (33–76) | 12/8 | Both rupture and unrupture aneurysms | 2.4–12.5 mm | Tirofiban | Coiling/stent/balloon | 5 μg/kg for 3–5 min followed by IV maintenance (0.08 μg/kg/min) for approximately 4–24 h | Acom: 8 (40) | Heparin |

CR: 10 (50%) | Irrelevant intracerebral hemorrhage:1 | 2 | No |

| MCA: 6 (30) | PR: 9 (45%) | Thromboemboli-related cerebral infarction:5 patients | ||||||||||||||

| ICA: 4 (20) | ||||||||||||||||

| IC-Pcom: 1 (5) | ||||||||||||||||

| A2–3:1 (5) | ||||||||||||||||

| Jeong et al. (2013) 10 | Korea | Case series | 22 | 44–80 | 9/13 | 32% had rupture aneurysms | 2.6–12 | Abciximab and tirofiban | Coiling/stent | Tirofiban:0.2–1 mg | Acom:6 | Heparin | CR: 5 (22%) | No hemorrhagic complications | — | No |

| Abciximab:10–20 mg | ACA:3 | PR: 13 (59%) | ||||||||||||||

| Basilar top:2 | ||||||||||||||||

| SCA:4 | ||||||||||||||||

| Left ICA Bifurcation:2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Paraclinoid:4 | ||||||||||||||||

| Right proximal A1:1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Ramakrishnan et al. (2013) 31 | USA | Case series | 40 | 50 | 8/32 | 71% had rupture aneurysms | — | Eptifibatide | Coiling/stent/balloon | 2.25–12 mg | — | Heparin | C:77.5% P:20% | Strokes: 10% intracerebral hemorrhage:20% | — | — |

| Parenchymal hematoma: 4% | ||||||||||||||||

| Katsaridis et al. (2008) 32 | Greece | Case series | 4 | 52.7 | 1/3 | Unruptured aneurysms | — | Eptifibatide | Coiling/stent/balloon | 15 mg (200 μg/kg) in 5–6 min | — | Heparin | CR and PR:100% | Hemorrhage | 3 | No |

| Song et al. (2004) 2 | USA | Case series | 7 | 52 | 2/5 | 57% had rupture aneurysms | 5–8 mm | Abciximab | Coiling/stent/balloon | 2–5 mg | Acom:2 | Heparin | CR:5 | Hemorrhage:2 | 1 | 1 patient |

| Pcom:1 | PR:1 | |||||||||||||||

| AM:1 | O:1 | |||||||||||||||

| MCA:2 | ||||||||||||||||

| AVM u :1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Pericallosal/parietal: 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| SH v :1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Walsh et al. (2011) 33 | USA | Case series | 51 | 68 (42–94) | 23/29 | 55% had rupture aneurysms | — | Abciximab | Coiling/stent/balloon | Over 5 min as 0.25–0.125 mg/kg | — | Heparin | Hemorrhage:9 | 9 | 4 patients |

aAnterior communicating artery.

bMiddle cerebral artery.

cInternal carotid artery.

dPosterior communicating artery.

eSupraclinoid internal carotid artery.

fComplete recanalization.

gPartial recanalization.

hIntra-Arterial.

iIntravenous.

jAnterior cerebral artery.

kPosterior cerebral artery.

lM1 segment of the middle cerebral artery.

mA2 segment of anterior cerebral artery.

nAnterior communicating artery.

oAnterior circulation.

pPosterior circulation.

qPosterior communicating artery.

rPericallosal artery.

sPericallosal artery aneurysm.

tOphthalmic artery aneurysm.

uArteriovenous malformation.

vSuperior hypophyseal.

Figure 3 presents the subgroup analysis of mortality outcome, based on sample size. The mortality rate in 13 studies in which abciximab had been used for thromboembolism was 5.1% (I2 = 08; p < .001) and it was 4.6% in four studies in which tirofiban (I2 = 22.43; p = .27) had been administered. Tirofiban and eptifibatide were used for thromboembolism in only one study. No significant effect was observed in the variance of the results according to the meta-regression performed based on the sample size, gender, and type of medicine (p = .82). Based on sensitivity analysis (SA), no change occurred in the result following the successive elimination of studies.

Figure 3.

Subgroup analysis of mortality outcome, based on sample size. Abciximab: The average mortality rate in 13 studies was 5.1% with p < .001 and I2 = 08. Tirofiban: The average mortality rate in four studies was 4.6% with p = .27 and I2 = 22.43. Tirofiban and Abciximab: One study. Eptifibatide: One study.

Figure 4 presents the subgroup analysis based on sample size for remission outcome. The remission rate in 12 studies that used abciximab for thromboembolism was 92% (I2 = 66.2; p < .001), and it was 86 in four studies in which tirofiban was used for thromboembolism (I2 = 77.48; p < .001). Moreover, the average remission rate was 82% in two studies in which eptifibatide was administered for thromboembolism (I2 = 0.48; p < .001) and 97% in studies in which tirofiban and abciximab were used. The result of meta-regression showed that gender and type of medicine (T) had significant effects on the variance of the results, but the sample size did not have any effect on heterogeneity (p = .13). Based on SA, no change was observed with the successive elimination of studies.

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis based on medicine type used for remission outcome. Abciximab: 12 studies with an average remission rate of 92% and p < .001; I2 = 66.28. Tirofiban: Four studies with an average remission rate of 86% and p < .00; I2 = 77.48. Tirofiban and abciximab: One study with an average remission rate of 97% and p: NA. Eptifibatide: Two studies with an average remission rate of 82% and p < .001; I2 = 0.

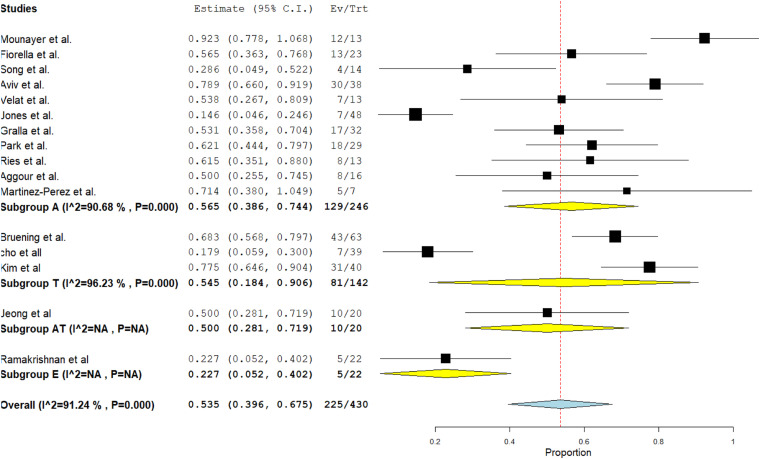

Figure 5 presents the subgroup analysis based on sample size for complete remission outcome. Based on the obtained results, the rate of complete remission outcome in 11 studies that used abciximab for thromboembolism has been estimated at 56% (I2 = 90.68; p < .001). The complete remission outcome rate in three studies that used tirofiban for thromboembolism was 54% (I2 = 96.23; p < .001). According to the conducted meta-regression based on sample size, gender, and type of medicine, no significant effect was observed in the variance of the results (p = .26). Based on SA, no change was observed with successive elimination of studies.

Figure 5.

Subgroup analysis based on sample size for complete remission outcome. Abciximab: 11 studies with an average remission rate of 56% and p < .001; I2 = 90.68. Tirofiban: Three studies with an average remission rate of 54% and p < .001; I2 : 96.23. Tirofiban and abciximab: One study. Eptifibatide: One study.

Discussion

Use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors for thromboembolic complications during cranial aneurysm coiling

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors are proper medications due to their safety, effectiveness, and relatively short half-lives. Three available glycoproteins IIb/IIIa inhibitors include abciximab, eptifibatide, and tirofiban.

Abciximab is a platelet aggregation inhibitor that binds to the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor of human platelets. Due to the beneficial effect of the agents in coronary catheter intervention, their use has been suggested for the treatment of thromboembolic complications during intracranial aneurysm coiling. 34

Although some studies claim an association between the use of abciximab for thromboembolism during coil embolization of cerebral aneurysms with cerebral hemorrhage and severe thrombocytopenia, others showed no such relationship.22,23 As an antiplatelet drug, tirofiban is a relatively short-acting and reversible glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitor. Eptifibatide is another antiplatelet drug of the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor class which is suggested for the treatment of thromboembolic complications during intracranial aneurysm coiling.

Success rate of intra-arterial or intravenous administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors

To assess the success rate of abciximab in different studies, they should be considered based on the utilized route of administration (IA, IV, or combined). Therefore, it is essential to consider four main factors in this regard, such as immediate angiographic outcome, rebleeding due to selective treatment, the neurological outcome at follow-ups, and the results of computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on the presence of ischemic lesions.

In the present meta-analysis, remission rate and complete remission outcome have been estimated at 92% and 56% due to the use of abciximab for the treatment of thromboembolism. It seems that abciximab is a beneficial treatment option for patients with ruptured or unruptured cerebral aneurysms. There are different routes of abciximab bolus administration in the literature. In a study conducted by Jones et al., an IV bolus was administered based on the patient’s weight (0.25 mg/kg). 19 Moreover, a selective arterial initial low-dose bolus was suggested by Mounayer et al., which showed a higher complete re-permeability and favorable neurological outcome with the IA bolus compared to the IV route (40% vs. 26.1%). 17

In a study conducted by Martínez-Pérez et al., the post-coiling state of the aneurysm after IA abciximab infusion was assessed based on MRI findings for the first time. The results showed a relationship between the dose of IA abciximab and aneurysm recanalization. Aneurysm recanalization was reported in 21% of the cases, and rebleeding was reported in none of these recanalized aneurysms after IA abciximab infusion. 18 However, the agent should be administered in patients with ruptured aneurysms, and some factors, including packing density and platelet count, should be considered in this regard.23,35

Aviv et al. showed that a high rate of complete recanalization was reported only with the administration of an IV bolus of abciximab. 25 No other similar studies investigated the IA bolus administration without IV infusion.2,17,23 In another study conducted by Ries et al., 3 and 39 patients were subjected to IA and IV abciximab, respectively. 22

Moreover, Aggour reported improved angiographic outcomes using IA bolus administration compared to the study conducted by Ries (complete recanalization: 56.5% vs. 14.3%; partial recanalization: 17.4 vs 59.5%). In general, in two studies conducted by Aggour and Ries, a higher rate of immediate angiographic recanalization was found with IA compared to IV bolus administration of abciximab.1,22

Jeong et al. investigated the effectiveness of IA abciximab and tirofiban infusion for the treatment of thromboembolism during coiling. They reported the effectiveness of IA compared to IV administration in the prevention of possible cerebral hemorrhage and the increase of the recanalization rate. 10

According to the literature, the success rates of IV and IA use of abciximab were estimated to be 50% and 86% in the prevention or decrease of strokes due to intraprocedural thromboembolic complications, respectively.1,19–21,36

Recanalization of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors for thromboembolic complications during cranial aneurysm coiling

Abciximab inhibits the formation and stability of the clot structure; moreover, it can disperse platelet aggregates. Therefore, both endogenous and parenteral fibrinolytic agents penetrate the clot due to the use of abciximab, which facilitates the rapid and extensive promotion of thrombolysis. 37 The successful recanalization rates after using abciximab are reported to be between 80% and 100% in the literature.1,11,38

A study performed by Martínez-Pérez et al. evaluated effectiveness of abciximab for the treatment of thromboembolic complications during aneurysm coiling. 18 The results of recently performed studies were similar to the findings of the aforementioned study.1,19,23

In another study, Mounayer et al. administered a bolus of abciximab for thrombus formation complicating aneurysm coiling. In the majority of the patients, the thrombi developed without coil protrusion into the parent artery. Moreover, complete recanalization was achieved in 92% of the patients. 17 Similarly, Aggour et al. reported a complete recanalization in the majority of the subjects with thrombi at the coil/parent artery interface (72.7%).

The IA administration of abciximab was used in the study performed by Song et al. for patients with ruptured and unruptured aneurysms. They reported complete recanalization in 71% of the patients, whereas no recanalization was reported in 14% of the patients. 2

Ramakrishnan et al. used eptifibatide to manage thromboembolism during the endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms. According to the results, recanalization was achieved in 97.5% of the cases, and it was complete in 77.5% of them. 31 Another study conducted by Katsaridis et al. confirmed the effectiveness of IA use of eptifibatide for rescue treatment, which led to a high rate of recanalization. 32 The experiences reported on the similar use of abciximab or tirofiban reveal that the mean rate of complete recanalization is higher by eptifibatide, compared to the mentioned agents,2,13,19,21–23,39,40 Bruening et al. assessed other glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (tirofiban) in terms of preventing thrombus formation and embolism. Partial or total occlusion of the parent vessel, which was reported in half of the patients, was dissolved completely after the patients received the combination of tirofiban and heparin. The outcome was excellent in six out of eight patients with an initial WFNS (World Federation of Neurological Surgeons) score 1. 27 In general, the data support the use of tirofiban as an alternative approach for the treatment of a thromboembolic complication of a ruptured intracranial aneurysm. The rate of immediate recanalization was higher in the tirofiban group, compared to the abciximab group; however, the difference was not statistically significant. 10

Administered dosage and half-life of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors

Abciximab is very beneficial, especially for controlling the development of a thromboembolic complication during the endovascular coiling of a ruptured aneurysm. Platelet function can be inhibited for approximately 48 h after the post-administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptors. 34 Commonly, an IV bolus of 0.25 mg/kg of abciximab, continued by a 12 h infusion of 0.125 mg/kg/m, is prescribed in coronary angioplasty. 17

Tirofiban is an antiplatelet drug that acts as a reversible antagonist of fibrinogen binding to the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor. The agent can effectively inhibit platelet aggregation after the administration of a 30 min loading dose. Its plasma half-life is estimated to be 2 h, which is remarkably shorter than that of abciximab with a time interval of up to 48 h to wear off.7,41 It can lead to the normalization of platelet function within approximately 4 h after discontinuation.41,42

Mounayer et al. administered a bolus of 4–10 mg of abciximab over 10–20 min to deliver a 4 mg bolus of the agent. Rapid desegregation of the thrombus was reported after the early administration of abciximab at high concentrations. 17 In another study, the injection of abciximab bolus (0.25 mg/kg continued by IV infusion of 0.125 mg/kg/min for 12 h) into the common carotid artery resolved symptoms of ischemic cerebrovascular events within 5 h. The IA injection of the abciximab at doses of 4 mg, 5 mg, and 10 mg after the failure of urokinase therapy results in a rapid flow restoration without hemorrhagic complications in patients with acute thrombosis of cerebral arteries.38,43

In one study, a bolus injection of 5 mg followed by an IV bolus of abciximab (5 mg) was administered in cases with acute distal embolization associated with carotid angioplasty. 44 Therefore, one can hypothesize that the local and immediate IA administration of low doses of abciximab effectively leads to the production of a high concentration of abciximab at the site of the thrombus. The mean (12.2 mg) and minimum (10 mg) doses of abciximab approximately account for 70% and 50% of the recommended loading dose of abciximab for a 70 kg subject, respectively. Moreover, the corresponding values were 470 μg and 10 mg for tirofiban, accounting for approximately 56% of the recommended loading dose of tirofiban for a 70 kg subject. The relatively lower administration doses of tirofiban compared to abciximab makes it more beneficial in terms of cost-effectiveness and safety. 10 Based on the obtained results, recanalization rates for both IA abciximab and tirofiban were high, 10 as reported in the previously conducted studies.1,2,22,23,27,28

Eptifibatide is an antiplatelet drug of the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor class with a rapid onset of action and a plasma half-life of 1.5 h. The function of the platelet is restored about 4 h after discontinuation of the eptifibatide. 31 Abciximab has a higher affinity for binding to the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor and other cell surface receptors with unclear significance compared to eptifibatide. 45

Hemorrhage and thrombocytopenia after the administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors

Bleeding is a serious concern with the administration of abciximab. However, no major hemorrhagic complications were reported among cases that received abciximab in addition to heparin, compared to those who received heparin alone. 46

Although some researchers suggest the occlusion of the aneurysm before the administration of abciximab, others do not agree.2,24,47,48 Moreover, increased hemorrhage is not reported after the administration of abciximab for immediate thromboembolic complications during aneurysm coiling, 25 thereby strengthening the argument in favor of abciximab administration. In a study conducted by Martínez-Pérez et al., hemorrhage, distal migration of the thrombus, and recanalization of the cerebral aneurysm were reported in half of the patients. 18

In one trial, a threefold increase in bleeding complications was reported with the administration of drugs along with IV heparin (between 10,000–12,000 U). 49 Moreover, a lower bleeding complication rate is observed using 70 U of heparin per kilogram.

In a study performed by Jones et al., activated clotting time was maintained between 200 and 300 s. 19 They planned to stop heparin use similar to that performed in some previous studies2,25 such as the study carried out by Velat et al. in which heparin administration was stopped after the prescription of abciximab. 24 Their results showed rebleeding in three patients.

In one study performed by Park et al., the post-procedural hemorrhage rate in ruptured or unruptured intracranial aneurysms was reported to be 9.7%, all of which occurred in patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms in the setting of thrombocytopenia. 23 In another study, the hemorrhagic complication rate was estimated at 18% after using abciximab. 33

The IA infusion of other glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (ie eptifibatide and tirofiban) rather than abciximab are considered an alternative treatment for thromboembolic complications. 50 There is some evidence of lower rates of rebleeding and thrombocytopenia due to the administration of tirofiban.10,51 Although tirofiban has a lower effect on the treatment of acute coronary syndromes compared to abciximab, it seems that its efficacy resembles that of abciximab in the treatment of thromboembolism during coil embolization of cerebral aneurysms.

Moreover, due to the short plasma half-life of tirofiban, it may be more suitable than abciximab for the mentioned problem. The plasma half-life of tirofiban is 2 h, whereas it is 48 h in the case of abciximab.20,27 In some surgeries such as external ventricular drainage that are necessary in some cases, the possibility of operation-related hemorrhagic complications is less with the administration of tirofiban compared to abciximab.

It seems that there is an association between the rate of bleeding episodes and thrombocytopenia with the use of tirofiban rather than abciximab.23,52 According to a study conducted by Cho et al., the amount of hemorrhage was lower after the administration of tirofiban compared to abciximab infusion. 29

Ramakrishnan et al. reported no patients with intracerebral or systemic hemorrhage with solitary administration of IA eptifibatide. Moreover, they showed no case of thrombocytopenia attributable to eptifibatide. The rates of bleeding, immunogenicity, and thrombocytopenia have been found to be higher with the administration of abciximab compared to eptifibatide. According to the mentioned study, eptifibatide is a better rescue agent in endovascular thromboembolic complications. 31

Conclusion

In general, early thrombus detection, protection of the aneurysm by coils, and use of IA glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors are three main factors for obtaining the optimal effects in thromboembolic events. The success rates of IV and IA use of abciximab in the prevention or decrease of the rate of strokes caused by intraprocedural thromboembolic complications were between 50% and 86%, respectively. No superiority was observed between abciximab and tirofiban in this regard. Moreover, the successful recanalization rates after using abciximab are reported to be between 80% and 100%. The results on the similar use of abciximab or tirofiban revealed a higher mean rate of complete recanalization by eptifibatide, compared to the mentioned agents. It seems that the success rate of eptifibatide is higher, compared to abciximab or tirofiban; however, due to a lack of sufficient data in this regard, further studies are recommended to confirm the results. In addition, the amount of hemorrhage was smaller with the administration of tirofiban compared to abciximab infusion. Moreover, the rates of bleeding and thrombocytopenia due to abciximab administration were higher compared to eptifibatide administration. Eventually, eptifibatide can be considered a better rescue agent in endovascular thromboembolic complications.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to their colleagues who provided insight and expertise during the study.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Ehsan Keykhosravi https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8762-2042

References

- 1.Aggour M, Pierot L, Kadziolka K, et al. Abciximab treatment modalities for thromboembolic events related to aneurysm coiling. Neurosurgery 2010; 67(suppl_2): ons503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song JK, Niimi Y, Fernandez PM, et al. Thrombus formation during intracranial aneurysm coil placement: treatment with intra-arterial abciximab. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004; 25(7): 1147–1153. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman JA, Piepgras DG, Pichelmann MA, et al. Small cerebral aneurysms presenting with symptoms other than rupture. Neurology 2001; 57(7): 1212–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiebers DO Whisnant JP Huston J, 3rd et al. International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms Investigators.. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. Lancet 2003; 362(9378): 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms Investigators . Unruptured intracranial aneurysms—risk of rupture and risks of surgical intervention. N Engl J Med 1998; 339(24): 1725–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cognard C, Weill A, Castaings L, et al. Intracranial berry aneurysms: angiographic and clinical results after endovascular treatment. Radiology 1998; 206(2): 499–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Workman MJ, Cloft HJ, Tong FC, et al. Thrombus formation at the neck of cerebral aneurysms during treatment with Guglielmi detachable coils. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002; 23(9): 1568–1576. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pelz DM, Lownie SP, Fox AJ. Thromboembolic events associated with the treatment of cerebral aneurysms with Guglielmi detachable coils. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998; 19(8): 1541–1547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bizzarri F, Scolletta S, Tucci E, et al. Perioperative use of tirofiban hydrochloride (Aggrastat) does not increase surgical bleeding after emergency or urgent coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001; 122(6): 1181–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeong HW, Jin S-C. Intra-arterial infusion of a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonist for the treatment of thromboembolism during coil embolization of intracranial aneurysm: a comparison of abciximab and tirofiban. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013; 34(8): 1621–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cronqvist M, Pierot L, Boulin A, et al. Local intraarterial fibrinolysis of thromboemboli occurring during endovascular treatment of intracerebral aneurysm: a comparison of anatomic results and clinical outcome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998; 19(1): 157–165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahnel S, Schellinger PD, Gutschalk A, et al. Local intra-arterial fibrinolysis of thromboemboli occurring during neuroendovascular procedures with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. Stroke 2003; 34(7): 1723–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiorella D, Albuquerque FC, Han P, et al. Strategies for the management of intraprocedural thromboembolic complications with abciximab (ReoPro). Neurosurgery 2004; 54(5): 1089–1097; discussion 1097–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abciximab in Ischemic Stroke Investigators . Abciximab in acute ischemic stroke. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study. Stroke 2000; 31(3): 601–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green S, Higgins J. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. London: Cochrane, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins J. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. London: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. https://www.cochrane-handbook.org [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mounayer C, Piotin M, Baldi S, et al. Intraarterial administration of abciximab for thromboembolic events occurring during aneurysm coil placement. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003; 24(10): 2039–2043. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martínez-Pérez R, Lownie SP, Pelz D. Intra-arterial use of abciximab in thromboembolic complications associated with cerebral aneurysm coiling: the london ontario experience. World Neurosurg 2017; 100: 342–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones RG, Davagnanam I, Colley S, et al. Abciximab for treatment of thromboembolic complications during endovascular coiling of intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29(10): 1925–1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gralla J, Rennie ATM, Corkill RA, et al. Abciximab for thrombolysis during intracranial aneurysm coiling. Neuroradiology 2008; 50(12): 1041–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linfante I, Etezadi V, Andreone V, et al. Intra-arterial abciximab for the treatment of thrombus formation during coil embolization of intracranial aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg 2010; 2(2): 135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ries T, Siemonsen S, Grzyska U, et al. Abciximab is a safe rescue therapy in thromboembolic events complicating cerebral aneurysm coil embolization: single center experience in 42 cases and review of the literature. Stroke 2009; 40(5): 1750–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park JH, Kim JE, Sheen SH, et al. Intraarterial abciximab for treatment of thromboembolism during coil embolization of intracranial aneurysms: outcome and fatal hemorrhagic complications. J Neurosurg 2008; 108(3): 450–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Velat GJ, Burry MV, Eskioglu E, et al. The use of abciximab in the treatment of acute cerebral thromboembolic events during neuroendovascular procedures. Surg Neurol 2006; 65(4): 352–358, discussion 358–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aviv RI, O’Neill R, Patel MC, et al. Abciximab in patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005; 26(7): 1744–1750. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gentric J-C, Brisson J, Batista AL, et al. Safety of Abciximab injection during endovascular treatment of ruptured aneurysms. Interv Neuroradiol 2015; 21(3): 332–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruening R, Mueller-Schunk S, Morhard D, et al. Intraprocedural thrombus formation during coil placement in ruptured intracranial aneurysms: treatment with systemic application of the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonist tirofiban. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006; 27(6): 1326–1331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang H-S, Kwon BJ, Roh HG, et al. Intra-arterial tirofiban infusion for thromboembolism during endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery 2008; 63(2): 230–237; discussion 237–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho YD, Lee JY, Seo JH, et al. Intra-arterial tirofiban infusion for thromboembolic complication during coil embolization of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. Eur J Radiol 2012; 81(10): 2833–2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim SH, Kim TG, Kong MH. Intra-arterial and intravenous tirofiban infusion for thromboembolism during endovascular coil embolization of cerebral aneurysm. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2017; 60(5): 518–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramakrishnan P, Yoo AJ, Rabinov JD, et al. Intra-arterial eptifibatide in the management of thromboembolism during endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms: case series and a review of the literature. Interv Neurol 2013; 2(1): 19–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katsaridis V, Papagiannaki C, Skoulios N, et al. Local intra-arterial eptifibatide for intraoperative vessel thrombosis during aneurysm coiling. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29(7): 1414–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walsh RD, Barrett KM, Aguilar MI, et al. Intracranial hemorrhage following neuroendovascular procedures with abciximab is associated with high mortality: a multicenter series. Neurocrit Care 2011; 15(1): 85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.EPILOG Investigators . Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockade and low-dose heparin during percutaneous coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med 1997; 336(24): 1689–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mascitelli JR, Oermann EK, De Leacy RA, et al. Predictors of treatment failure following coil embolization of intracranial aneurysms. J Clin Neurosci 2015; 22(8): 1275–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yi H-J, Gupta R, Jovin TG, et al. Initial experience with the use of intravenous eptifibatide bolus during endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006; 27(9): 1856–1860. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collet JP, Montalescot G, Lesty C, et al. A structural and dynamic investigation of the facilitating effect of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in dissolving platelet-rich clots. Circ Res 2002; 90(4): 428–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwon O-K, Lee KJ, Han MH, et al. Intraarterially administered abciximab as an adjuvant thrombolytic therapy: report of three cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002; 23(3): 447–451. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duncan IC, Fourie PA. Catheter-directed intra-arterial abciximab administration for acute thrombotic occlusions during neurointerventional procedures. Interv Neuroradiol 2002; 8(2): 159–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pagola J, Ribo M, Alvarez‐Sabin J, et al. Thrombolysis in anterior versus posterior circulation strokes: timing of recanalization, ischemic tolerance, and other differences. J Neuroimaging 2011; 21(2): 108–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morris P. Interventional and endovascular therapy of the nervous system: a practical guide. Berlin, Germany: Springer Science and Business Media, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harder S, Klinkhardt U, Alvarez JM. Avoidance of bleeding during surgery in patients receiving anticoagulant and/or antiplatelet therapy: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations. Clin Pharmacokinet 2004; 43(14): 963–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ho DSW, Wang Y, Chui M, et al. Intracarotid abciximab injection to abort impending ischemic stroke during carotid angioplasty. Cerebrovasc Dis 2001; 11(4): 300–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kittusamy PK, Koenigsberg RA, McCormick DJ. Abciximab for the treatment of acute distal embolization associated with internal carotid artery angioplasty. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2001; 54(2): 221–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coller BS. Anti-GPIIb/IIIa drugs: current strategies and future directions. Thromb Haemost 2001; 86(07): 427–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akkerhuis KM, Deckers JW, Lincoff AM, et al. Risk of stroke associated with abciximab among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Jama 2001; 286(1): 78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ng PP, Phatouros CC, Khangure MS. Use of glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitor for a thromboembolic complication during Guglielmi detachable coil treatment of an acutely ruptured aneurysm. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2001; 22(9): 1761–1763. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lempert TE, Malek AM, Halbach VV, et al. Rescue treatment of acute parent vessel thrombosis with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor during GDC coil embolization. Stroke 1999; 30: 693–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Topol EJ, Ferguson JJ, Weisman HF, et al. Long-term protection from myocardial ischemic events in a randomized trial of brief integrin beta3 blockade with percutaneous coronary intervention. EPIC Investigator Group. Evaluation of Platelet IIb/IIIa Inhibition for Prevention of Ischemic Complication. Jama 1997; 278(6): 479–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Topol EJ, Moliterno DJ, Herrmann HC, et al. TARGET Investigators. Do Tirofiban and ReoPro Give Similar Efficacy Trial . Comparison of two platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, tirofiban and abciximab, for the prevention of ischemic events with percutaneous coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med 2001; 344(25): 1888–1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herrmann HC, Swierkosz TA, Kapoor S, et al. Comparison of degree of platelet inhibition by abciximab versus tirofiban in patients with unstable angina pectoris and non–Q-wave myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2002; 89(11): 1293–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mangiafico S, Cellerini M, Nencini P, et al. Intravenous tirofiban with intra-arterial urokinase and mechanical thrombolysis in stroke: preliminary experience in 11 cases. Stroke 2005; 36(10): 2154–2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]