Abstract

Background:

Advanced practice providers (APPs) comprise an increasing proportion of the emergency medicine (EM) workforce, particularly in rural geographies. With little known regarding potential expanding practice patterns, we sought to evaluate trends in independent emergency care services billed by APPs from 2013 to 2019.

Methods:

We performed a repeated cross-sectional analysis of emergency clinicians independently reimbursed for at least 50 Evaluation & Management (E/M) services [99281–99285, 99291] from Medicare Part B, with high acuity services including codes 99285 and 99291. We describe the outcome proportion of E/M services by acuity level, and report at 1) the encounter-level and 2) at the clinician-level. We stratified analyses by clinician type and geography.

Results:

A total of 47,323 EM physicians, 10,555 non-EM physicians, and 26,599 APPs were included in analyses. APPs billed emergency care services independently for 5.1% (rural – 7.3%, urban – 4.8%) of all high acuity encounters in 2013, increasing to 9.7% (rural – 16.4%, urban – 8.8%) by 2019. At the clinician-level, in 2013, the average rural-practicing APP independently billed 22.8% of services as high acuity, 72.6% as moderate acuity, and 4.5% as low acuity. By 2019, the average rural-practicing APP independently billed 36.2% of services as high acuity, representing a +58.8% relative increase from 2013. Relative increases in high acuity visits independently billed by APPs were substantially greater when compared to EM physicians across both rural and urban geographies.

Conclusions:

In 2019, APPs billed independent services for approximately 1 in 6 high acuity ED encounters in rural geographies and 1 in 11 high acuity ED encounters in urban geographies, and well over one-third of the average APPs’ encounters were for high acuity E/M services. Given differences in training and reimbursement between clinician types, these estimates suggest further work is needed evaluating emergency care staffing decision-making.

Keywords: Emergency medicine, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, visit acuity, rural health

Introduction

Advanced practice providers (APPs), primarily including physician assistants and nurse practitioners, comprise an increasing proportion of the emergency medicine (EM) workforce, particularly in rural geographies.1–4 APPs have provided care in the ED setting for years, primarily with a focus on low-acuity patients, such as in a fast-track setting. Over time, as ED visit volumes have increased and physician shortages in select geographies have increased, APPs have expanded their care to more complex and acute patients, often under the direct supervision of a physician.5,6 Policies permitting independent APP practice with indirect physician support have been implemented by many states to facilitate staffing of rural geographies or safety net providers. Concerns exist regarding the expanding practice patterns of APPs, yet prior analyses have suggested the potential for APP replacement of physician care for higher acuity patients to be unfounded.7,8 To date, there has not been detailed assessment of APP independent service provision in nationally representative data to determine how practice patterns have changed, particularly regarding high acuity emergency care.

Significant training and expertise are required for the delivery of high quality emergency care and critical care services, particularly trauma resuscitations, cardiac emergencies, and acute neurological emergencies. A March 2022 Guideline by the American College of Emergency Physicians stated that physician assistants and nurse practitioners should not perform independent, unsupervised care in the ED setting.9 Given current workforce limitations,1,3 APP independent service provision remains essential to providing 24/7 staffing in select EDs and communities for all emergency care ranging from lower acuity visits to critical care services in the ED.

Several recent studies have documented increasing visit acuity and complexity of ED visits.10–12 However, it remains unknown if there has been a change in the independent service provision of APPs as visit acuity has increased. First, these data are important in ongoing policy discussions at the state and federal level regarding the payment and delivery of emergency care services, particularly in rural geographies. Second, and perhaps most importantly, data here can inform a new dialogue among training programs and regulatory bodies regarding the supply of the emergency care workforce.

We sought to describe trends in independent emergency care services billed by APPs across visit acuity and visit geographies for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries from 2013 to 2019. We conduct both encounter- and clinician-level analyses to provide quantitative estimates of the role that APPs play in the provision of emergency care.

Methods

Study Design and Dataset

We performed a repeated cross-sectional analysis of emergency clinicians using the CMS Provider Utilization and Payment Data from the Physician and Other Practitioners Public Use File (PUF), including the currently available years of 2013 to 2019.13 This study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board, and we followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.14

This dataset has been well described in several prior EM workforce analyses and provides information on services provided to Medicare beneficiaries by healthcare professionals based on CMS administrative claims data.1,15–17 The PUF provides information on all clinicians with active national practitioner identification (NPI) registrations reimbursed greater than 10 times by the Medicare fee-for-service Part B program in a calendar year. The PUF also includes information regarding clinician demographics (name, credentials, gender, rurality) and utilization and payment information organized by billed E/M services through the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS).

Data Management

All clinicians in the Medicare PUF with addresses registered to the 50 states and Washington D.C were included. Clinicians were required to receive ≥50 total reimbursements within a study year for E/M services 99281–99285 and 99291, reflecting the typical emergency and critical care services rendered by emergency clinicians. Consistent with prior work,11,15 high acuity services included E/M service codes 99285 and 99291, moderate acuity services included E/M service codes 99283 and 99284, and low acuity services included E/M service codes 99281 and 99282. Clinician type (EM physician, non-EM physician, APP) was determined from the ‘Provider Type’ variable, identified from the clinician specialty code reported on received claims. The APP category was inclusive of nurse practitioners, physician assistants, certified nurse midwives, and certified registered nurse anesthetists. Non-EM physicians were defined as physicians with a non-EM medical specialty designated (Supplemental Table 1). All encounters were attributed to rural and urban geographies based on the Rural Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) code of the emergency clinician. Consistent with prior work,17 clinicians in metropolitan areas (Rural Urban Commuting Area codes 1 to 3) were classified as urban and clinicians in micropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas (Rural Urban Commuting Area codes 4 to 10) were classified as rural.

Outcome Measures

We assessed two outcomes: 1) encounter-level proportions of E/M services, and 2) clinician-level proportions of E/M services. At the encounter-level, we first examined what proportion of high acuity encounters were independently billed by different emergency clinician types, and whether changes have occurred in recent years. Additionally, we examined whether these trends varied by visit geography (e.g. rural vs. urban). For example, EM physicians may have billed 70% of high acuity E/M services in rural geographies in a given study year, while non-EM physicians billed 20% and APPs independently billed the remaining 10%. At the clinician-level, we then identified the average proportion of E/M services that a clinician (stratified by clinician type) provided across the study years. At the level of the individual clinician, the outcome captured the proportion of E/M services that were high, moderate, or low acuity in comparison to a clinician’s total number of E/M services. For example, an individual rural-practicing APP in 2014 may have billed 5% E/M services as low acuity, 70% as moderate acuity, and 25% as high acuity.

Statistical Analyses

We present descriptive statistics of clinicians providing emergency care. For the clinician-level analyses, we also present relative differences in the mean % of E/M services billed by level of acuity from 2013 to 2019. This was conducted to isolate the impact of clinician type and rural-urban location, as concurrent trends have suggested a more global increased high acuity E/M service provision.

To evaluate robustness of data from the main analyses, we performed secondary analyses to assess proportions of only critical care services (99291) billed across clinician types and geographies.

We performed data management and analyses using Stata (version 16; StataCorp, College Station, TX) and created data visualizations using GraphPad Prism.

Results

Study Population Trends

A total of 84,477 unique clinicians provided at least 50 ED E/M services during one of the 2013 to 2019 study years, including 47,323 EM physicians, 10,555 non-EM physicians, and 26,599 APPs. In 2013, there were 49,243 EM clinicians, with an increase to 58,636 EM clinicians by 2019. In 2013, 7,716 EM clinicians provided care in rural geographies and 41,527 EM clinicians provided care in urban geographies, while 7,877 EM clinicians provided care in rural geographies and 50,759 EM clinicians provided care in urban geographies in 2019. Annually, the total number of Medicare fee-for-service encounters ranged from 21,113,066 (in 2019) to 22,123,781 (in 2017), with the proportion of high acuity encounters increasing and the proportion of moderate and low acuity encounters decreasing every year (Table 1).

Table 1.

Emergency clinicians and encounters by rural-urban designation and acuity, 2013–2019.

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total clinicians | 49,243 | 50,830 | 52,414 | 54,898 | 56,886 | 58,042 | 58,636 |

| EM physicians | 33,293 (67.6%) |

34,216 (67.3%) |

35,016 (66.8%) |

35,987 (65.6%) |

37,010 (65.1%) |

37,513 (64.6%) |

38,366 (65.4%) |

| Rural | 4,001 | 3,929 | 3,895 | 3,837 | 3,835 | 3,814 | 3,804 |

| Urban | 29,292 | 30,287 | 31,121 | 32,150 | 33,175 | 33,699 | 34,562 |

| Non-EM physicians | 5,774 (11.7%) |

5,568 (11.0%) |

5,328 (10.2%) |

5,354 (9.8%) |

5,260 (9.2%) |

5,297 (9.1%) |

5,153 (8.8%) |

| Rural | 1,970 | 1,870 | 1,782 | 1,714 | 1,663 | 1,608 | 1,525 |

| Urban | 3,804 | 3,698 | 3,546 | 3,640 | 3,597 | 3,689 | 3,628 |

| APPs | 10,176 (20.7%) | 11,046 (21.7%) |

12,070 (23.0%) |

13,557 (24.7%) |

14,616 (25.7%) |

15,232 (26.2%) |

15,117 (25.8%) |

| Rural | 1,745 | 1,858 | 1,991 | 2,210 | 2,421 | 2,507 | 2,548 |

| Urban | 8,431 | 9,188 | 10,079 | 11,347 | 12,195 | 12,725 | 12,569 |

| Total Encounters | 21,183,771 | 21,326,957 | 21,757,627 | 22,091,840 | 22,123,781 | 21,570,013 | 21,113,066 |

| Low acuity | 304,620 (1.4%) |

266,364 (1.2%) |

255,964 (1.2%) |

243,757 (1.1%) |

234,247 (1.1%) |

218,145 (1.0%) |

205,803 (1.0%) |

| Moderate acuity | 9,026,580 (42.6%) |

9,026,607 (42.3%) |

9,014,058 (41.4%) |

8,912,626 (40.3%) |

8,600,961 (38.9%) |

8,230,130 (38.2%) |

7,739,632 (36.7%) |

| High acuity | 11,852,571 (56.0%) |

12,033,986 (56.4%) |

12,487,605 (57.4%) |

12,935,457 (58.6%) |

13,288,573 (60.1%) |

13,121,738 (60.8%) |

13,167,631 (62.4%) |

| Encounters by clinician type | |||||||

| Low acuity | |||||||

| EM physicians | 190,798 (62.6%) |

170,739 (64.1%) |

164,834 (64.4%) |

151,153 (62.0%) |

143,494 (61.3%) |

133,598 (61.2%) |

125,444 (61.0%) |

| Non-EM physicians | 65,454 (21.5%) |

54,569 (20.5%) |

49,045 (19.2%) |

46,255 (19.0%) |

41,735 (17.8%) |

36,377 (16.7%) |

30,934 (15.0%) |

| APPs | 48,368 (15.9%) |

41,056 (15.4%) |

42,085 (16.4%) |

46,349 (19.0%) |

49,018 (20.9%) |

48,170 (22.1%) |

49,425 (24.0%) |

| Moderate acuity | |||||||

| EM physicians | 6,641,297 (73.6%) |

6,577,531 (72.9%) |

6,501,017 (72.1%) |

6,321,656 (70.9%) |

6,009,469 (69.9%) |

5,700,024 (69.3%) |

5,377,704 (69.5%) |

| Non-EM physicians | 983,004 (10.9%) |

924,825 (10.2%) |

876,152 (9.7%) |

823,245 (9.2%) |

772,752 (9.0%) |

720,329 (8.8%) |

662,049 (8.6%) |

| APPs | 1,402,239 (15.5%) |

1,524,251 (16.9%) |

1,636,889 (18.2%) |

1,767,725 (19.8%) |

1,818,740 (21.1%) |

1,809,777 (22.0%) |

1,699,879 (22.0%) |

| High acuity | |||||||

| EM physicians | 10,282,353 (86.8%) |

10,397,031 (86.4%) |

10,717,802 (85.8%) |

10,977,236 (84.9%) |

11,189,415 (84.2%) |

10,966,748 (83.6%) |

10,963,651 (83.3%) |

| Non-EM physicians | 961,830 (8.1%) |

923,533 (7.7%) |

938,745 (7.5%) |

961,254 (7.4%) |

975,299 (7.3%) |

949,997 (7.2%) |

930,036 (7.1%) |

| APPs | 608,388 (5.1%) |

713,422 (5.9%) |

831,058 (6.7%) |

996,967 (7.7%) |

1,123,859 (8.5%) |

1,204,993 (9.2%) |

1,273,944 (9.7%) |

Abbreviations: APP, advanced practice provider

Note: Low acuity - E/M service codes 99281 and 99282; Moderate acuity - E/M service codes 99283 and 99284; High acuity - E/M service codes 99285 and 99291

Main Results

Across all acuity levels and geographies, APPs independently billed E/M services for 8.3% of emergency encounters involving Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries in 2013, increasing to 14.3% in 2019 (Table 1). In 2013, APPs independently billed E/M services for 15.9% of low acuity encounters, 15.5% of moderate acuity encounters, and 5.1% of high acuity encounters. By 2019, APPs independently billed E/M services for 24.0% of low acuity encounters, 22.0% of moderate acuity encounters, and 9.7% of high acuity encounters. Comparatively, EM physicians in 2013 billed E/M services for 86.8% of all high acuity encounters involving Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, slightly decreasing to 83.3% by 2019.

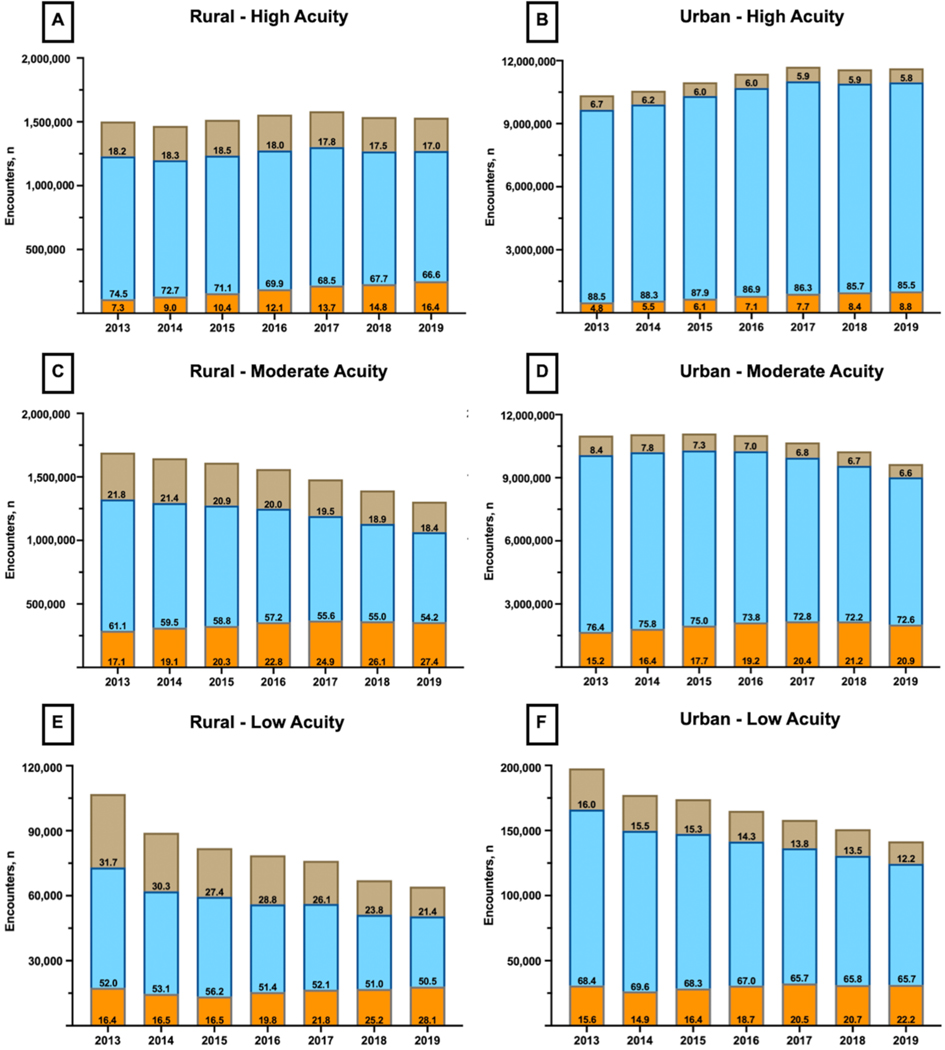

APPs billed more high acuity care independently in rural geographies, with 7.3% (1 in 14 encounters) of high acuity encounters billed by APPs in 2013 increasing to 16.4% (1 in 6 encounters) in 2019. In urban geographies, 4.8% (1 in 21 encounters) of high acuity encounters were independently billed by APPs in 2013 compared to 8.8% (1 in 11 encounters) in 2019 (Figure 1). Counter to the trends exhibited among APPs, 74.5% of rural high acuity encounters in 2013 were billed by an EM physician, decreasing to 66.6% by 2019. In urban geographies, 88.5% of high acuity encounters were billed by an EM physician, decreasing to 85.5% by 2019.

Figure 1.

Encounter-level E/M services billed by emergency clinicians across rural-urban designations and acuity levels.

Note: Orange – Advanced practice providers; Blue – EM physicians; Brown – Non-EM physicians.

Note: Panel A – High acuity services billed in rural designations; Panel B – High acuity services billed in urban designations; Panel C – Moderate acuity services billed in rural designations; Panel D – Moderate acuity services billed in urban designations; Panel E – Low acuity services billed in rural designations; Panel F – Low acuity services billed in urban designations.

Note: As an example interpretation, in calendar year 2016 there were 1,556,693 high acuity encounters in rural designations. EM physicians performed 69.9% of those encounters, non-EM physicians performed 18.0%, and APPs independently performed the remaining 12.1%.

Note: The numbers listed within the columns represent the proportions (%) that an individual clinician type contributed to total clinician encounters within that year, acuity level, and rural-urban designation.

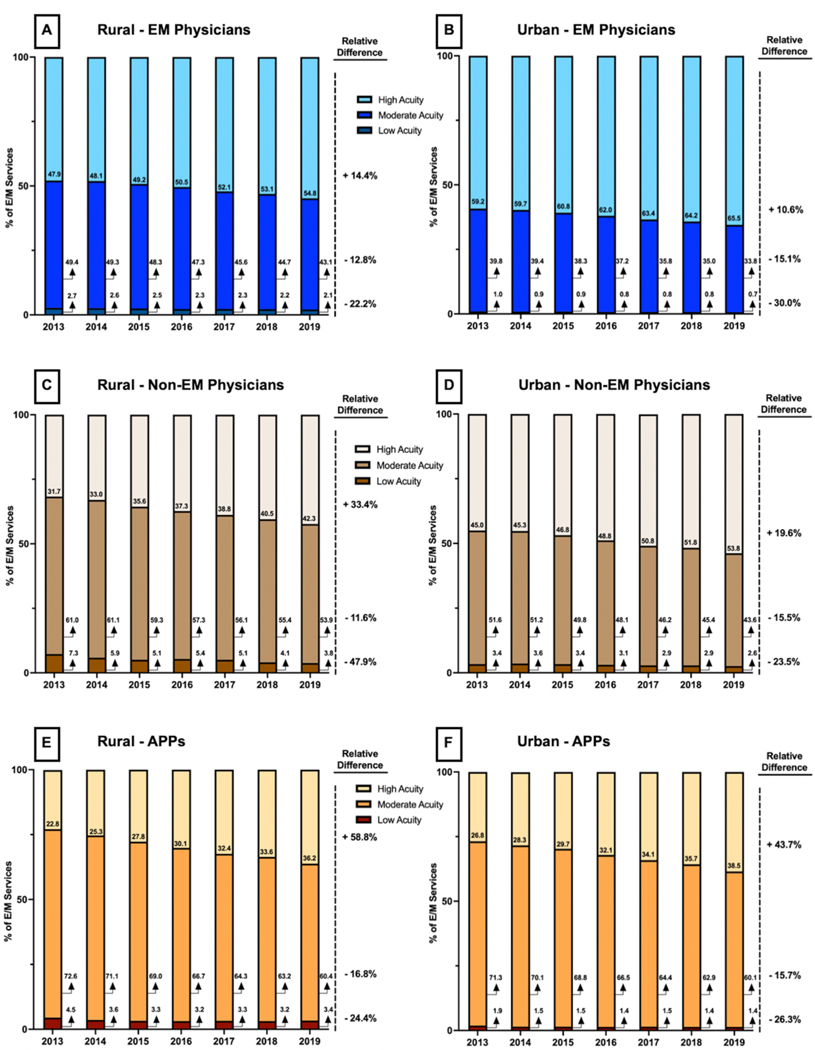

In 2013, the average rural EM physician billed 47.9% of services as high acuity, 49.4% as moderate acuity, and 2.7% as low acuity. Comparatively, the average rural-practicing APP independently billed 22.8% as high acuity, 72.6% as moderate acuity, and 4.5% as low acuity. By 2019, the average rural EM physician billed 54.8% of services (a +14.4% relative difference) as high acuity and the average rural APP billed 36.2% of services (a +58.8% relative difference) as high acuity when compared to 2013. In 2013, the average urban EM physician billed 59.2% of services as high acuity, 39.8% as moderate acuity, and 1.0% as low acuity. Comparatively, the average urban-practicing APP independently billed 26.8% as high acuity, 71.3% as moderate acuity, and 1.9% as low acuity. By 2019, the average urban EM physician billed 65.5% of services (a +10.6% relative difference) as high acuity and the average urban APP billed 38.5% of services (a +43.7% relative difference) as high acuity when compared to 2013 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Clinician-level E/M services billed across rural-urban designations and clinician types.

Abbreviations: APP, advanced practice provider; E/M, Evaluation & Management

Note: Orange scale – Advanced practice providers; Blue scale – EM physicians; Brown scale – Non-EM physicians.

Note: Panel A – % of E/M services billed by the average EM physician in rural designations; Panel B – % of E/M services billed by the average EM physician in urban designations; Panel C – % of E/M services billed by the average non-EM physician in rural designations; Panel D – % of E/M services billed by the average non-EM physician in urban designations; Panel E – % of E/M services billed by the average APP in rural designations; Panel F – % of E/M services billed by the average APP in urban designations.

Note: As an example interpretation, in calendar year 2016, the average EM physician practicing in rural designations billed 50.5% of E/M services as high acuity (99285 or 99291), 47.3% as moderate acuity (99283 or 99284), and the remaining 2.3% as low acuity (99281 or 99282). The relative difference between 2013 (47.9%) and 2019 (54.8%) in high acuity billing for the average EM physician practicing in rural designations was +14.4.

Secondary Analysis

In 2013, there were 26,733 EM clinicians who billed for critical care services, including 2,330 rural EM physicians, 21,567 urban EM physicians, 576 rural non-EM physicians, 1,693 urban non-EM physicians, 112 rural APPs, and 455 urban APPs. Critical care encounters (99291) were increasingly billed independently by APPs, increasing from 1.1% in 2013 to 2.9% in 2019. In rural geographies, APPs independently billed 0.2% of critical care encounters in 2013, increasing to 0.5% in 2019. In urban geographies, APPs independently billed 0.9% of critical care encounters in 2013, increasing to 2.4% in 2019. In 2013, the average APP independently billed 0.6% of their E/M services as critical care, rising to 1.4% by 2019. Further results of encounter and clinician proportions for critical care billing E/M services within each year can be found in Supplemental Table 2.

Discussion

This study is the first to characterize trends of APPs independently billing high acuity emergency care services nationally. Our study had 2 main findings. First, APPs independently billed nearly 10% of all high acuity encounters for Medicare beneficiaries in the ED by 2019, with that proportion reflecting a near doubling since 2013. The increase of encounters billed independently by APPs was greater in rural geographies compared to urban geographies. Second, the average APP independently billed nearly 40% of their encounters as high acuity by 2019, compared to just over 25% in 2013. The relative increase in high acuity emergency care services billed by the average clinician was greater for APPs, when compared to EM physicians and non-EM physicians, and in rural geographies, when compared to urban geographies. These are important practice changes in how the most acutely ill patients in U.S. emergency departments are cared for.

Our work extends prior literature in several ways. APPs have previously been noted to comprise an increasing proportion of the workforce,1 with our work identifying that this increasing proportion of the workforce is disproportionately also providing more complex care, with APPs independently billing approximately 1 in 6 high acuity encounters in rural geographies and approximately 1 in 11 in urban geographies as of 2019. Prior work has identified both that APPs make up an increasing proportion of the EM workforce and separately that billing for high acuity services has increased as well.1,11 If more widespread billing increases were the sole reason for acuity changes, we may have expected to see a similar rise in high acuity encounters regardless of clinician type or rural-urban location. Instead, the average rural-practicing EM physician exhibited a +14.4% relative difference in high acuity billing from 2013 to 2019, while the average rural-practicing APP exhibited a +58.8% increase, suggesting significant changes in high acuity billing between clinician types that likely extend beyond more recent global billing practice increases. The observed trends likely reflect that in rural geographies physician staffing may not be available 24/7 for all EDs and that APPs are increasingly filling the void. We also observed a pattern of increasing independent APP practice in urban geographies in which physician staffing is robust, suggesting that this trend is not solely related to clinician supply. Given the specialized knowledge and training (e.g. invasive procedures, point-of-care ultrasound, rapid management of complex conditions) needed to deliver high quality care for high acuity encounters, the increase in independent APP practice may impact access to trained or certified emergency care specialists across EDs.

Several factors may have contributed to the trends identified in this work. First, APPs have successfully advocated for independent practice both in state policies and within hospitals and health systems.18–20 Within an ED or hospital, it is logical that as APPs become a more experienced part of the physician-led ED team, they may be trusted with higher acuity care. Internal training programs for APPs in emergency medicine have provided additional skills and facilitated this practice expansion.21,22 In a recent analysis from a large national emergency medicine group by Pines et al.,23 diagnostic testing and hospitalization rates for chest pain and abdominal pain between APPs and physicians were largely similar after matching for severity and complexity. Second, rural workforce shortages have been identified, with little progress made thus far in recruiting and retaining board-certified EM physicians to non-urban areas. Third, APPs are less costly than physicians, so those responsible for staffing EDs may have increased the use of APPs to reduce staffing costs amidst increasingly narrow margins and payment cuts from both public and private payers. This trend may have accelerated as not-for-profit hospitals’ margins shrink and for-profit entities control a growing share of hospitals and ED staffing companies.24 Collectively, this multi-year trends analyses, along with economic forces described, suggests that independent APP practice in high acuity emergency care is here to stay.

This work is of primary relevance to current training requirements for APPs. Across emergency clinician types, clinical training for high acuity care varies greatly. EM physicians complete a medical degree as well as 3 to 4 years of dedicated specialty training often followed by board certification. In contrast, there is no requirement for postgraduate training or accredited certification for APPs to work independently in an ED. Approximately 10–15% of PAs working in the ED have completed postgraduate EM training in one of the approximately 50 postgraduate EM programs, which run on average 27 months in duration.25,26 The number of NPs with postgraduate EM training is unknown, but is likely much lower as programs have historically been focused on PAs. Therefore, over 80% of PAs and nearly 100% of NPs instead rely on ‘on the job’ emergency care training.21,26 With no mandated accreditation for APP postgraduate training programs,24 the Society of Emergency Medicine Physician Assistants (SEMPA) developed a standardized curriculum in 2015. These standards serve as a guideline for programs, and not a requirement, and note that ‘EM PA residents/fellows should treat a significant number of the critically ill or critically injured patients; approximating at least one month or 160 hours of critical care experience overall’.27 Together, this suggests that there is likely a mismatch between the relatively limited critical care exposure that APPs obtain in training programs and the privileges granted to care for high acuity patients independently. These findings raise an important need to revisit training requirements or standards for APPs performing high acuity emergency care.

Additionally, this work has payment and policy implications that can help direct the specialty towards future strategies to improve access to high quality emergency care. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently announced billing policy updates to split/shared visits, inclusive of those performed both by physician and APP.28,29 Previously, when an ED visit was shared between a physician and APP, the E/M service could be billed under the physician’s Unique Physician Identifier Number as long as a ‘substantive portion’ of the physician’s engagement was defined by performing a history, examination, or medical decision making as the key component. Starting in 2024, the ‘substantive portion’ will solely be met by the clinician who provides more than half of total time on the encounter, with payments made at 85% of the Medicare physician fee schedule for encounters in which the ‘substantive portion’ was performed by an APP. Many EM groups may soon face cuts to revenue as visits in which direct APP supervision was previously provided by physicians will now be considered independent APP services from a reimbursement perspective. ED groups will soon be faced with a choice to either 1) increase APP independent practice and reduce direct physician supervision to those cases unlikely to meet the physician majority time threshold, or 2) increase utilization of emergency physicians who will independently perform the ‘substantive portion’ of encounters and increase reimbursement at the full 100% Medicare physician schedule. With this anticipated major shift in reimbursement for physician-APP teams, future research will be needed to evaluate the provision of emergency services across clinician types and the implications on safety and quality outcomes.

Limitations

There are several limitations of the present analysis that deserve mention. First, the PUF data contains only information on Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, and therefore may not be completely representative of a clinician’s entire practice. However, it remains unlikely that a large number of emergency clinicians did not accept Medicare insurance, and therefore we believe our estimates to have a low risk of systematic bias in identifying clinicians. Second, care provided and services billed by APPs may have been underreported, as the PUFs do not capture split/shared visits between APPs and supervising physicians. Given the relatively minimum requirements for physician billing of an APP-physician shared visit during the study timeframe, the estimates of service provision by APPs therefore are likely conservative. Third, Medicare claims data lacks setting specifications for critical care service codes. With the 99291 E/M service code able to be billed for within the ED, the intensive care unit, or the hospital floor, we excluded clinicians who solely billed 99291 but did not also bill E/M service codes reflective of care in the ED setting (99281–99285). As a result of this requirement, 95% of the clinicians billed less than 17.7% of services as critical care using the 2013 workforce as an example. Therefore, we believe this requirement captured emergency clinicians who had a sizable footprint providing emergency setting care, supporting the robustness of our findings. Fourth, NPI data have limitations. For example, a clinician working within the Indian Health Service may have a license from any state, and the address associated with the NPI may be inaccurate. This finding may categorize a very small proportion of rural-practicing physicians as urban physicians and, if present, would therefore underestimate the differences seen between rural and urban practicing clinicians. Fifth, the PUF reports the specialty for which the clinician billed the largest number of services that year, particularly relevant in the case when a physician identifies as belonging to multiple specialties. CMS’s approach to this possibility is not expected to systematically redistribute clinicians in a biased fashion, thereby maintaining our findings. Finally, many potential aggregate measures exist to define ED patient acuity – case mix, emergency severity index, inpatient admission rate.30 While the dataset used does not capture ED- or patient-level clinical data, we believe our use of E/M codes to define patient acuity most accurately reflects the resources used within the individual encounter and is also aligned with prior research.11,15

Conclusion

In summary, there was a substantial increase from 2013 to 2019 in the proportion of high acuity ED patients cared for by APPs across the U.S. In 2019, APPs billed independent services for approximately 1 in 6 high acuity ED encounters in rural geographies and 1 in 11 high acuity ED encounters in urban geographies. This increase in independent service provision by APPs nearly doubled between 2013 and 2019. The average APP independently billed well over one-third of their encounters as high acuity by 2019, compared to just over one-quarter in 2013. This represents a fundamental change in the model of care delivery for emergency medicine and for APPs. Further research is needed to evaluate if these changes in ED care have impacts on quality, safety, or cost of care.

Supplementary Material

Financial Support:

Dr. Gettel is a Pepper Scholar with support from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale School of Medicine (P30AG021342), the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH; R03AG073988), the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Foundation, and the Emergency Medicine Foundation. Dr. Schuur is supported by the Frances Weeden Gibson-Edward A. Iannuccilli M.D. endowed Professorship in Emergency Medicine. Dr. Venkatesh is supported in part by the American Board of Emergency Medicine National Academy of Medicine Anniversary fellowship and formerly by the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation grant KL2 TR000140 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS/NIH). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure:

CJG and AKV are members of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine’s Workforce Committee.

References

- 1.Gettel CJ, Courtney DM, Janke AT, et al. The 2013 to 2019 emergency medicine workforce: clinician entry and attrition across the US Geography. Ann Emerg Med 2022;S0196-0644(22)00280-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Nelson SC, Hooker RS. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners in rural Washington emergency departments. J Physician Assist Educ 2016;27(2):56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marco CA, Courtney DM, Ling LJ, et al. The emergency medicine physician workforce: projections for 2030. Ann Emerg Med 2021;78(6):726–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpenter CR, Abrams S, Courtney DM, et al. Advanced practice providers in academic emergency medicine: a national survey of chairs and program directors. Acad Emerg Med 2022;29(2):184–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hooker RS, Klocko DJ, Larkin GL. Physician assistants in emergency medicine: the impact of their role. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18(1):72–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zane RD, Michael SS. The economics and effectiveness of advanced practice providers are decidedly local phenomena. Acad Emerg Med 2020;27(11):1205–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu F, Darracq MA. Physician assistant and nurse practitioner utilization in U.S. emergency departments, 2010 to 2017. Am J Emerg Med 2020;38(10):2060–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pines JM, Zocchi MS, Ritsema T, Polansky M, Bedolla J, Venkat A. The impact of advanced practice provider staffing on emergency department care: productivity, flow, safety, and experience. Acad Emerg Med 2020;27(11):1089–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American College of Emergency Physicians. Guidelines regarding the role of physician assistants and nurse practitioners in the emergency department. https://www.acep.org/patient-care/policy-statements/guidelines-regarding-the-role-of-physician-assistants-and-nurse-practitioners-in-the-emergency-department/. Accessed June 26, 2022.

- 10.Chou SC, Baker O, Schuur JD. Changes in emergency department care intensity from 2007–16: analysis of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. West J Emerg Med 2020;21(2):209–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke LG, Wild RC, Orav EJ, Hsia RY. Are trends in billing for high-intensity emergency care explained by changes in services provided in the emergency department? An observational study among US Medicare beneficiaries. BMJ Open 2018;8(1):e019357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin MP, Baker O, Richardson LD, Schuur JD. Trends in emergency department visits and admission rates among US acute care hospitals. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178(12):1708–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Physician & Other Practitioners – by Provider and Service. https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-physician-other-practitioners/medicare-physician-other-practitioners-by-provider-and-service. Accessed March 23, 2022.

- 14.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med 2007;147(8):573–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gettel CJ, Canavan ME, Greenwood-Ericksen MB, et al. A cross-sectional analysis of high-acuity professional services performed by urban and rural emergency care physicians across the United States. Ann Emerg Med 2021;78(1):140–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall MK, Burns K, Carius M, Erickson M, Hall J, Venkatesh AK. State of the national emergency department workforce: who provides care where? Ann Emerg Med 2018;72(3):302–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gettel CJ, Canavan ME, D’Onofrio G, Carr BG, Venkatesh AK. Who provides what care? An analysis of clinical focus among the national emergency care workforce. Am J Emerg Med 2021;42:228–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emergency Medicine News. NPs pushing expansion of independent practice. https://journals.lww.com/em-news/blog/breakingnews/pages/post.aspx?PostID=573. Accessed June 26, 2022.

- 19.American Medical Association. Physician assistant scope of practice. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/public/arc-public/state-law-physician-assistant-scope-practice.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2022.

- 20.Emergency Medicine News. Are NPs and PAs taking EP jobs? https://journals.lww.com/em-news/Fulltext/2017/08000/News__Are_NPs_and_PAs_Taking_EP_Jobs_.2.aspx#pdf-link. Accessed June 26, 2022.

- 21.Kraus CK, Carlisle TE, Carney DM. Emergency medicine physician assistant (EMPA) postgraduate training programs: program characteristics and training curricula. West J Emerg Med 2018;19(5):803–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsyrulnik A, Goldflam K, Coughlin R, et al. Implementation of a physician assistant emergency medicine residency within a physician residency. West J Emerg Med 2020;22(1):45–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pines JM, Zocchi MS, Ritsema TS, Bedolla J, Venkat A. Emergency and advanced practice provider diagnostic testing and admission decisions in chest pain and abdominal pain. Acad Emerg Med 2021;28(1):36–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NBC News. Doctor fired from ER warns about effect of for-profit firms on U.S. health care https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-care/doctor-fired-er-warns-effect-profit-firms-us-health-care-rcna19975. Accessed June 26, 2022.

- 25.Chekijian SA, Elia TR, Horton JL, Baccari BM, Temin ES. A review of interprofessional variation in education: challenges and considerations in the growth of advanced practice providers in emergency medicine. AEM Educ Train 2020;5(2):e10469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Society of Emergency Medicine Physician Assistants. Emergency Medicine Postgraduate Education for Physician Assistants Statement. https://www.sempa.org/professional-development/aaem-response---march-23/#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20postgraduate%20emergency,programs%20spread%20across%2020%20states. Accessed July 11, 2022.

- 27.Society of Emergency Medicine Physician Assistants. Postgraduate Training Program Standards. https://www.sempa.org/professional-development/postgraduate-training-program-standards. Accessed July 11, 2022.

- 28.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS-1751-F. https://www.cms.gov/medicaremedicare-fee-service-paymentphysicianfeeschedpfs-federal-regulation-notices/cms-1751-f. Accessed June 26, 2022. [PubMed]

- 29.American College of Emergency Physicians. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners FAQ. https://www.acep.org/administration/reimbursement/reimbursement-faqs/physician-assistants-and-nurse-practitioners--faq/. Accessed June 26, 2022.

- 30.Yiadom MYAB, Baugh CW, Barrett TW, et al. Measuring emergency department acuity. Acad Emerg Med 2018;25(1):65–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.