Abstract

Background:

Emergency care workforce concerns have gained national prominence given recent data suggesting higher than previously estimated attrition. With little known regarding characteristics of physicians leaving the workforce, we sought to investigate the age and number of years since residency graduation at which male and female EM physicians exhibited workforce attrition.

Methods:

We performed a repeated cross-sectional analysis of EM physicians reimbursed by Medicare linked to date of birth and residency graduation date data from the American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM) for the years 2013–2020. Stratified by gender, our primary outcomes were the median age and number of years since residency graduation at the time of attrition, defined as the last year during the study timeframe that an EM physician provided clinical services. We constructed a multivariate logistic regression model to examine the association between gender and EM physician workforce attrition.

Results:

A total of 25,839 (70.2%) male and 10,954 (29.8%) female EM physicians were included. During the study years, 5,905 male EM physicians exhibited attrition at a median age (IQR) of 56.4 (44.5–65.4) years, and 2,463 female EM physicians exhibited attrition at a median (IQR) age of 44.0 (38.0–53.9) years. Female gender (aOR= 2.30, 95%CI: 1.82 to 2.91) was significantly associated with attrition from the workforce. Male and female EM physicians had respective median (IQR) post-residency graduation times in the workforce of 17.5 (9.5–25.5) years and 10.5 (5.5–18.5) years among those who exhibited attrition, and 1 in 13 males and 1 in 10 females exited clinical practice within five years of residency graduation.

Conclusions:

Female physicians exhibited attrition from the EM workforce at an age approximately 12 years younger than male physicians. These data identify widespread disparities regarding EM workforce attrition that are critical to address to ensure stability, longevity, and diversity in the emergency physician workforce.

Keywords: Emergency medicine, workforce, attrition, gender, age

Introduction

Long-term strategic planning of the emergency medicine (EM) workforce is essential to balance physician supply with increasing patient demand and ensure the provision of high-quality clinical care. Emergency workforce studies date back over three decades,1,2 with early studies suggesting a shortage of EM physicians followed by more recent projections predicting a considerable surplus.3–6 Attrition from the workforce may mitigate a potential overabundance of EM physicians. The latest estimates suggest an annual cumulative attrition rate of approximately 5% prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, with estimates increasing to 8.2% attrition during early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.7 Rural and urban area differences in workforce attrition have been detailed,7,8 yet there is limited literature exploring differences in EM physician attrition by other important characteristics such as age, gender, and time since residency graduation using real-world clinical practice data.

Differential attrition of female EM physicians is an area of inquiry that is particularly limited. The proportion of women graduating medical school has risen from approximately 30% in 1985 to over 50% in 2022.7–10 However, despite similar representation at the medical school level, 2022 AAMC data suggest that 39.4% of EM residents are female, a proportion that has remained relatively stagnant since 2007 when 38.8% of EM residents were identified as female.10 Beyond residency graduation, only 29% of active EM physicians and 11.7% of EM department chairs are female.11,12 This decreasing percent of female physicians at progressive milestones along the EM career continuum may be due to differences in attrition as earlier exit from the EM workforce by women may be one potential structural barrier to advancement. Possible causes of the underrepresentation of women in EM in later career stages and roles include promotion discrepancies, salary deficits, burnout, traditional societal ‘norms’ (e.g. time expectations regarding domestic and family activities), and gender-specific factors including sexual harassment, mistreatment and gender bias in the workplace – all of which may lead to lack of pursuit and recruitment into leadership roles, but also differential attrition rates of female versus male EM physicians.13–19

Despite well-described risk factors for attrition of female EM physicians, studies to date have commonly relied on anticipatory surveys (asking respondents when they plan to leave the workforce) or have not looked specifically at the EM physician workforce.20,21 Estimates across all specialties suggest that the majority of physicians exit clinical practice sometime between 60 and 69 years of age,20 yet it stands to reason that EM physicians in general, and women in particular given the above factors, may be prone to early attrition from clinical practice. Addressing potential gender inequities in age at attrition from the EM workforce is critical to inform employment recruitment and retention strategies.

Therefore, this study’s primary objective was to describe the age at which male and female physicians exhibited attrition from the EM workforce between the years of 2013 to 2020. As a secondary objective, we identified the number of years since residency graduation of physicians at the time of attrition from the EM workforce.

Methods

Study Design and Datasets

We performed a repeated cross-sectional analysis of emergency physicians using the CMS 2013–2020 Provider Utilization and Payment Data from the Physician and Other Supplier Public Use File (PUF), linked to date of birth data and residency graduation date data obtained from the American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM).22 At the time of analysis, the 2020 study year was the most recent year available in the Medicare PUF. ABEM data included any physician who had ever been board certified as of September 30, 2022. This study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board and followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.23

Used within several prior EM workforce analyses,7,24–26 the PUF provides information on services provided to Medicare beneficiaries by healthcare professionals. It is based on data from the CMS Chronic Condition Data Warehouse (CCW), a database with 100% of Medicare enrollment and fee-for-service administrative claims data. The PUF contains data on utilization and payment (allowed amount and Medicare payment) organized by National Provider Identifier (NPI), Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code, and place of service (facility or non-facility). To protect the privacy of Medicare beneficiaries, clinicians must be reimbursed by the Medicare fee-for-service Part B program greater than 10 times in a calendar year for an individual Evaluation & Management (E/M) service code to be included within the PUF. Clinician demographics (name, credentials, gender, address, rurality, entity type) within the PUF are included from the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System (NPPES). Within the NPPES, the variable for ‘gender’ allowed a possible response of “male” or “female”, illustrating a common lack of clear differentiation between sex and gender response categories within large population surveys. Given that the aforementioned underlying reasons for attrition are largely due to gender (most influential construct) more so than sex, we have maintained consistency in our analyses and reporting with the original data collection practices by NPPES and used ‘gender’.

Data Management

Clinicians in the Medicare PUF with addresses registered to the 50 states and Washington D.C were considered for inclusion. Based on HCPCS E/M codes 99281 to 99285, included clinicians were required to cumulatively receive ≥50 reimbursements in any one of the study years between 2013 and 2020, identical to thresholds in previous EM workforce analyses, to qualify as “practicing” that year.6,7 Linked by NPI, we identified 39,650 EM clinicians that were included in both the Medicare PUF and ABEM data. Seven emergency clinicians had missing date of birth information and were therefore excluded. An additional 734 emergency clinicians were excluded as they were identified to be non-EM physicians determined within the Medicare PUF data from the ‘Provider Type’ variable. Consistent with prior work identifying emergency clinicians,7,24 this designation was derived from the provider specialty code reported on the claim. Ten EM physicians were excluded as they had a residency graduation date after the time of attrition (explained further below). An additional 1,785 EM physicians had a residency graduation date in or after 2020 and were excluded as they were not eligible to be identified as exhibiting attrition during the study timeframe. Finally, 321 EM physicians were only present in the dataset in 2020, and were therefore excluded for a similar reason. The remaining 36,793 EM physicians represented the analytic sample with complete Medicare PUF and ABEM date of birth data (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Analytic sample flow diagram

Abbreviations: ABEM – American Board of Emergency Medicine; NPP – Non-physician practitioner; CMS – Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; DOB – date of birth; EM – emergency medicine

We then developed a second analytic sample of residency-trained EM physicians to further characterize those exhibiting attrition during the 2013 to 2019 study years (attrition described further below). This portion of the analysis followed a retrospective cohort design, where we first identified those who exhibited attrition (outcome) during the years of data available and then presented data based on the physician’s residency graduation year (exposure). From the 36,793 EM physicians in the original analytic sample, 2,869 were excluded as they had incomplete or missing residency graduation date data, resulting in 33,924 with complete date of birth and residency graduation date data. Including only those EM physicians that exhibited attrition during the 2013 to 2019 study years, the second analytic sample included 6,580 EM physicians and consisted of 4,303 male and 2,277 female EM physicians.

Outcomes

Our primary outcomes were the median age and the number of years since residency graduation at the time of attrition, stratified by gender. Consistent with prior work,7 physicians exhibiting attrition were identified as those who exited the workforce during one year of the study timeframe and were not identified to provide clinical services within any subsequent study year. For uniformity and ease of interpretation, we solely focused on EM physicians who exhibited ‘permanent attrition’ and avoided inclusion of those who exhibited ‘temporary attrition’,7 characterized by those who provided ED E/M services later in the 2013 to 2020 study timeframe after originally exiting the workforce. For each study year, we calculated the median age of EM physicians exhibiting attrition, stratified by gender. As we were unable to identify the exact date of a physician’s attrition from the workforce, we used a conservative approach to determine the age of each EM physician at the end of every year in which they practiced clinically by determining the difference between their date of birth and December 31st of the assessed study year. For example, a physician with a date of birth of June 30, 1965, billed for ED E/M services within the 2016 year, and then was not identified to provide clinical services in the 2017 to 2020 study years. Using December 31, 2016, as the date of attrition, we identified that the physician was 51.5 years of age at the time of attrition.

Using residency graduation date data, we employed a similar approach as described above to assess the number of years since residency graduation until attrition, stratified by gender, among the analytic sample of 6,580 EM physicians with complete residency graduation date data that exhibited attrition during the 2013 to 2019 study years.

Statistical Analyses

We first calculated descriptive statistics of EM physicians providing emergency care with complete date of birth data from ABEM. We calculated annual attrition proportions stratified by gender. Then, we calculated age distributions at the time of attrition, stratified by gender.

We next constructed a multivariate logistic regression model to examine the association between gender and attrition using a series of model building strategies. By the technique of domain knowledge, we first selected available features conceptually linked (association or confounding) to the outcome. We controlled for the log transformation of ‘years since residency graduation’ and incorporated an interaction term of gender and log transformation of ‘years since residency graduation’ to account for dynamic proportional changes in male and female EM physicians (thereby subject to attrition) since the specialty’s inception. The ‘age’ variable was not included in the final models as it was identified to be collinear with ‘years since residency graduation’. We report adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals. The unit of analysis was the NPI, and we included 33,924 EM physicians in the workforce, with 6,580 having met the attrition outcome. We limited our analyses to observations with complete valid data for the variables of interest.

Among the 6,580 EM physicians with complete residency graduation date data who exhibited attrition during the 2013 to 2019 study years, we present paired bar charts of the number of EM physicians exhibiting attrition in the years after residency graduation, stratified by gender.

Finally, we assessed attrition after residency graduation year for those with complete prospective data of at least 5 years duration, including those graduating residency between 2013 and 2015. For example, we identified EM physicians who graduated residency in 2013 and exhibited attrition from the workforce between 2013 and 2018.

We performed data management and analyses using Stata (version 16; StataCorp, College Station, TX) and created data visualizations using GraphPad Prism.

Sensitivity Analysis

To evaluate robustness of data from the main analyses, we performed an additional sensitivity analysis using a more conservative definition for attrition in which we required EM physicians to be absent from the EM workforce for at least 3 years to be considered as exhibiting attrition. Three years was chosen to address potential misclassification if an EM physician temporarily exited the workforce but was categorized as attrition based on the above definition. The intent of this analysis was to avoid including EM physicians in the later years of the study timeframe who may have actually exhibited temporary attrition if the dataset were extended additional years. Of those EM physicians who temporarily left the workforce within the study timeframe, 96% returned to clinical practice within three years, thereby supporting use of this time horizon. Given the duration of the dataset, this sensitivity analysis therefore included EM physicians who exhibited attrition between 2013 and 2017 and were not identified to provide clinical services again for at least the 3-year timespan between 2018 and 2020.

Results

Characteristics of Study Population

During the 2013 to 2020 timeframe, a total of 86,660 unique clinicians were included from the Medicare PUF dataset. Within that sample, 36,793 EM physicians had complete ABEM date of birth data. In 2013, the EM physician workforce that met our inclusion criteria included 18,079 males and 6,753 females, with respective increases identified to 21,307 and 9,135 in 2019. EM physicians clinically practicing within the 2013 and 2019 timeframe exhibited similar median (interquartile range [IQR]) ages, respectively identified as 43.0 (36.8–51.7) and 42.1 (36.1–50.5) years of age. Of those with complete ABEM date of birth data between 2013 to 2019, 5,905 male EM physicians exhibited attrition at a median age (IQR) of 56.4 (44.5–65.4) years and 2,463 female EM physicians exhibited attrition at a median (IQR) age of 44.0 (38.0–53.9) years.

Main Results

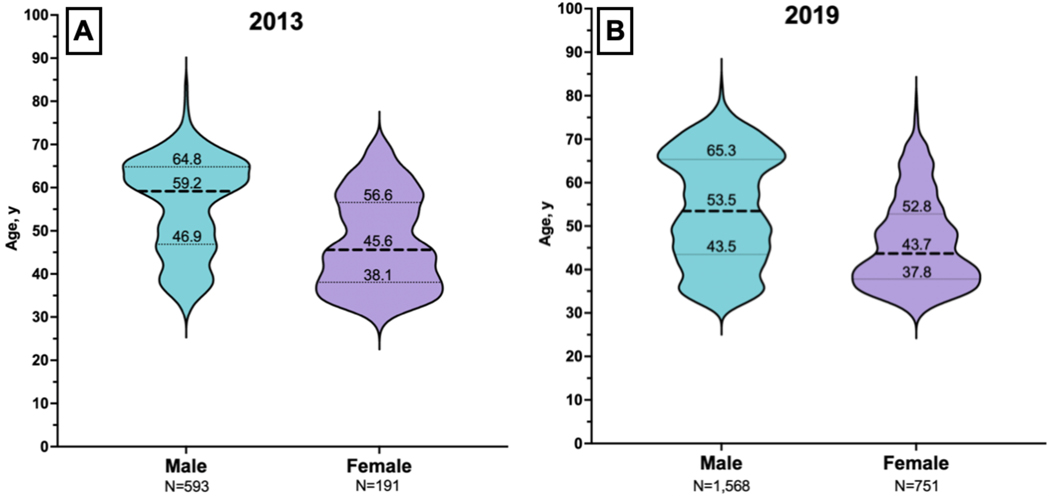

In 2013, 593 (3.3%) male and 191 (2.8%) female EM physicians exhibited attrition and were not identified to provide emergency setting E/M services through the remainder of the study years (Table 1). The 784 EM physicians who exhibited attrition in 2013 had a median (IQR) age of 56.2 (44.0–63.5) years, stratified to 59.2 (46.9–64.8) years for male and 45.6 (38.1–56.6) years for female EM physicians (Table 2). In 2019, the last year that attrition could be calculated, 1,568 (7.4%) male and 751 (8.2%) female EM physicians respectively exhibited attrition, as they were not identified to provide ED E/M services during the 2020 year (Table 1). The 2,319 EM physicians who exhibited attrition in 2019 had a median (IQR) age of 49.7 (40.6–62.8) years, stratified to 53.5 (43.5–65.3) years for male and 43.7 (37.8–52.8) years for female EM physicians (Table 2, Figure 2).

Table 1.

Annual attrition proportion by gender

| Male Physicians | Female Physicians | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # in EM workforce | % attrition | # in EM workforce | % attrition | |

| 2013 | 18,079 | 3.3% | 6,753 | 2.8% |

| 2014 | 18,536 | 3.4% | 7,174 | 3.3% |

| 2015 | 18,956 | 3.3% | 7,528 | 3.9% |

| 2016 | 19,529 | 3.6% | 7,968 | 3.4% |

| 2017 | 20,206 | 4.3% | 8,391 | 4.2% |

| 2018 | 20,655 | 4.4% | 8,740 | 4.2% |

| 2019 | 21,307 | 7.4% | 9,135 | 8.2% |

Note – The year listed is the last year the physician was identified to provide clinical services, defined as exhibiting attrition. For example, 974 (3.5%) of 27,497 physicians left the workforce in 2016 and were not identified to provide clinical services in 2017–2020. Stratified by gender, this included 702 (3.6%) of 19,529 male and 272 (3.4%) of 7,968 female EM physicians.

Table 2.

Median age at year of attrition

| Median age, y (IQR) at year of attrition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Total | 56.2 (44.0–63.5) N=784 | 54.9 (42.9–63.6) N=870 | 52.7 (41.1–63.2) N=918 | 52.4 (41.8–64.5) N=974 | 51.4 (41.3–64.1) N=1,232 | 50.7 (41.4–64.1) N=1,271 | 49.7 (40.6–62.8) N=2,319 |

| Male | 59.2 (46.9–64.8) N=593 | 59.1 (45.3–64.6) N=632 | 57.4 (43.9–65.1) N=626 | 58.1 (45.0–65.8) N=702 | 55.4 (43.8–65.8) N=876 | 55.3 (44.4–65.8) N=908 | 53.5 (43.5–65.3) N=1,568 |

| Female | 45.6 (38.1–56.6) N=191 | 45.4 (38.4–57.2) N=238 | 44.4 (37.8–56.6) N=292 | 43.4 (37.6–52.2) N=272 | 44.2 (37.8–52.2) N=356 | 43.4 (38.1–52.9) N=363 | 43.7 (37.8–52.8) N=751 |

Note – The year listed is the last year the physician was identified to provide clinical services, defined as exhibiting attrition.

Note – The analytic sample was the 36,793 EM physicians with complete ABEM date of birth data.

Figure 2.

Age distribution at time of attrition for males and females, 2013 and 2019

Note – Panel A – 2013; Panel B – 2019.

Note – Thick dashed line represents median, thin dotted lines represent first and third quartiles.

Note – The analytic sample was the 36,793 EM physicians with complete ABEM date of birth data.

Within the logistic regression model, female gender (aOR=2.30, 95%CI: 1.82 to 2.91) and log-transformed years since residency graduation (aOR=3.00, 95% CI: 2.84 to 3.17) were significantly associated with attrition from the workforce between 2013 and 2019 study years. We also identified a significant interaction between gender and years since residency graduation (aOR=0.86; 95% CI: 0.79 to 0.94), with a larger gender difference in attrition (female more than male) noted for those more recently graduating from residency.

Among the 6,580 EM physicians with complete residency graduation date data that exhibited attrition during the 2013 to 2019 study years, the 4,303 male and 2,277 female EM physicians had respective median (IQR) post-residency graduation times in the workforce of 17.5 (9.5–25.5) years and 10.5 (5.5–18.5) years (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Time within workforce among male and female EM physicians exhibiting attrition during 2013–2019 study years

Note – Included are 6,580 EM physicians (4,303 male and 2,277 female) that exhibited attrition between 2013 and 2019. Among that population, male and female EM physicians had respective median (IQR) post-residency graduation times in the workforce of 17.5 (9.5–25.5) years and 10.5 (5.5–18.5) years.

Five-year prospective attrition estimates for residents graduating between 2013 and 2015 ranged between 6.1–10.0% for male and 8.4–12.7% for female EM physicians. As an example, among the 1,558 identified to graduate residency in 2013, 57 (6.1%) male and 65 (10.4%) female EM physicians left emergency setting clinical practice within 5 years (Table 3).

Table 3.

Five-year prospective workforce attrition among EM residency graduates

| Residency Graduation Year | Emergency Medicine Residency Graduates, N | Graduated Residents that Exhibited Attrition Prospectively Within 5 Years, N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||

| 2013 | 1,558 | 57 (6.1%) | 65 (10.4%) |

| 2014 | 1,607 | 73 (7.2%) | 50 (8.4%) |

| 2015 | 1,645 | 105 (10.0%) | 75 (12.7%) |

Sensitivity Analysis

After incorporating a more conservative definitive of attrition, we identified that the 3,429 male and 1,349 female EM physicians who exhibited attrition between 2013 to 2017 (also absent in the workforce at least from 2018 to 2020) respectively had a median age (IQR) of 58.0 (44.9–65.3) and 44.5 (38.0–54.7) years. Including this population within the logistic regression model as part of the sensitivity analysis, female gender (aOR=2.25, 95%CI: 1.57 to 3.23) and log-transformed years since residency graduation (aOR=3.90, 95% CI: 3.61 to 4.23) remained significantly associated with attrition from the workforce between 2013 and 2017 study years. These findings are consistent with those identified within primary analyses and the original definition of attrition.

Discussion

In this analysis of national emergency care clinical practice data, we identified four main findings. First, at the time of attrition from the EM workforce, female EM physicians were over 12 years younger in comparison to male EM physicians. Second, the median age for both male and female EM physicians respectively exhibiting attrition decreased considerably from 59.2 and 45.6 years in 2013 to 53.5 and 43.7 years in 2019, well below prior reports that suggest physician retirement often occurs after the age of 60.20 Third, among those who exhibited attrition from the EM workforce between 2013 to 2019, females left the workforce after residency graduation approximately seven years before their male counterparts. Finally, nearly 1 in 13 male and 1 in 10 female EM physicians were prospectively identified to leave the EM workforce within five years of residency graduation.

Our findings demonstrate considerably higher attrition rates than prior literature, while documenting gender differences in rates, years in the workforce post-residency graduation, and age at attrition. Prior studies have estimated annual EM workforce attrition to range between 1–10%, although some are limited by their survey design asking physicians their expectations regarding clinical practice in years to come.1,15,27 Previous observational studies have suggested potential underlying reasons for both the overall and gender-specific trends identified in our study, including increasing burnout in emergency medicine in general, and female physicians exhibiting greater burnout, being paid less, and facing greater challenges with recognition, advancement and academic promotion when compared to male physician colleagues.13,14 For mid-career women specifically, a multifactorial phenomenon has been described with barriers causing cumulative inequity, leading women to become invisible, marginalized, discouraged, and potentially leaving their positions, with further work needed to better understand potential causes of attrition at varying ages and career stage.28 These and other factors may conceptually increase the risk for attrition among women which our analysis quantified as departing the EM workforce at an age 12 years younger than their male counterparts. Going forward, there is a pressing need to perform analyses that place these EM-specific findings into context among attrition rates of attendings within other specialties.

There are several potential implications of female EM physicians leaving the workforce considerably earlier than male EM physicians. First, female EM physicians bring unique perspective and experiences to the workforce, and their absence or attrition leads to a less diverse workforce providing emergency care, contributing to the trainee learning environment, and serving as role models for medical students, all being critical to counteract the widening gender gap at higher levels of EM leadership and to consider in light of the most recent 2023 EM Match results. Second, female EM physicians exhibiting attrition from the EM workforce are unable to influence the greater healthcare landscape through leadership positions generally attained later in careers. Third, patient outcomes may suffer, as prior work has shown female internists to provide higher quality care and achieve better 30-day mortality and readmission rates when compared to male internists.29 Finally, Greenwood et al. reported that female patients were two to three times more likely to survive a myocardial infarction if their emergency physician was female.30

Across genders, significant implications also exist regarding the age of the EM workforce and those exhibiting attrition. Our work identifies an EM physician workforce that has a median age of 43.0 and 42.1 years for men and women, respectively. These findings are aligned with recent survey data of EM physicians and provide additional evidence that the workforce is becoming younger,31,32 with attrition serving as a potential contributor to this distribution. Prior workforce projections, assuming lower attrition rates or older ages at the point of attrition, should be revisited and conducted regularly to ensure accurate projections that will optimize supply and demand for emergency care. The critical need for action has never been more apparent than after release of the most recent Residency Match cycle data, in which the number of unfilled EM residency positions rose from 14 in 2021 to 219 in 2022 to 555 in 2023.33 Like the declining number of medical students entering the specialty, we identified that practicing EM physicians are exiting emergency setting clinical practice at relatively younger ages – potentially a result of more global non-gender-specific causative factors such as record-level hospital crowding,34,35 COVID-19 pandemic stressors,36 widespread staffing shortages, and prior EM physician workforce surplus projections.6

The findings of this study showcase marked gender disparities in attrition that warrant immediate attention and have significant implications for the specialty of emergency medicine, the ability to maintain a diverse workforce, and the ability to meet emergency care demands in the future. Going forward, these findings should serve as a clarion call to revisit strategies that have been described to address recruitment and retention within the EM workforce.13 While this study time frame extends through 2020, it does not take into account the full effect of the COVID-19 pandemic and resultant changes to emergency care including record-level boarding, increased behavioral health emergencies, and increased workplace violence that likely increased the risk of attrition. Recent fundamental early-stage efforts by specialty society organizations have worked to counteract these potential contributors to attrition, seeking to improve workforce safety, reduce barriers to promotion of women, and provide toolkits to address unique challenges to female academic EM physicians that may add longevity to careers.37–39 Previously described for female EM physicians, central concepts to guide strategies should include the “commitment to the education, management, and elimination of gender bias; affording women with equal access to opportunities and resources; providing leadership support and engagement; and supporting and creating a culture that strengthens work-life integration and family-friendly policies.”13,40 Finally, amid the current changing landscape of emergency care, future research (e.g. qualitative methods) should consider evaluating what EM physicians exhibiting attrition do after leaving facility- or hospital-based clinical practice: retirement, urgent care or another clinical care setting, telehealth practice, administrative role, consulting, or something else?

Limitations

There are several limitations of the present analysis that deserve mention. First, the PUF data only contains information regarding Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries. While this population may not be completely reflective of a physician’s entire practice, it is unlikely that a large number of emergency physicians left the workforce to care for a population exclusive of Medicare beneficiaries. Second, physicians were required to perform ≥50 ED levels 1 to 5 E/M services in a study year for inclusion, with this requirement consistent with prior workforce literature. A lower threshold may have included a nominal number of additional physicians and resulted in a slightly reduced risk for misclassification, yet we believe the current threshold includes those EM physicians with an adequate number of emergency care services provided. Third, rather than dates for individual encounters at the physician level, the dataset included summary statistics regarding how many E/M services of a certain type (e.g. 99285) a physician provided, thereby preventing knowledge of the exact date of attrition for each physician within the study year. Therefore, the date of attrition was selected to be December 31 for each case if the physician was not identified to provide E/M services in the following year. This conservative approach resulted in study participants likely being slightly younger at the exact time of attrition than calculated for this analysis, but systematic bias (e.g. towards one gender) is unlikely. Fourth, the PUF reports the specialty for which the physician billed the largest number of services that year, particularly relevant in the case when a physician identifies as belonging to multiple specialties. CMS’s approach to this possibility is not expected to systematically redistribute physicians in a biased fashion, thereby maintaining our findings. Fifth, we did not investigate the prevalence of partial attrition or transitions to part-time effort. Although decreases in clinical effort might not reflect similar motivations as complete exits from clinical practice, in aggregate they might sum to substantial changes in the overall workforce (i.e. physicians opting to be 0.8 or 0.9 full-time equivalent). Sixth, it is possible that there are additional variables, aside from those which we had access to and were able to assess, that confound, contribute to, mediate, and/or moderate the gender-attrition relationship. Finally, we are limited by the duration of the available data (2013 to 2020), and therefore it is possible that EM physicians exhibited attrition prior to the study timeframe.

Conclusion

In summary, over the 2013–2020 time period, emergency physicians exhibited attrition from the clinical workforce at increasingly younger ages, and female physicians consistently exhibited attrition from the EM workforce at an age approximately 12 years younger than their male counterparts. Additionally, nearly 1 in 13 male and 1 in 10 female EM physicians were prospectively identified to leave the EM workforce within five years of residency graduation. These data identify widespread disparities with respect to EM workforce attrition between male and female EM physicians. Addressing the root causes of this issue is crucial to promoting a more diverse and sustainable EM workforce.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank Anna Sather, BS, for assisting with the background literature review for the topic.

Financial Support:

Dr. Gettel is a Pepper Scholar with support from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale School of Medicine (P30AG021342) and the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH; R03AG073988). Dr. Ranney is supported in part by NIGMS P20 GM139664. Dr. Venkatesh was supported in part by the American Board of Emergency Medicine National Academy of Medicine Anniversary fellowship and by the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation grant KL2 TR000140 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS/NIH). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations:

This work was selected for presentation at the 2023 Society for Academic Emergency Medicine annual meeting in Austin, TX.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure:

CJG, DMC, and AKV are members of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine’s (SAEM) Workforce Committee. PA, MDL, and AMM currently serve on the SAEM Board of Directors. PA, TEM, and MDL have served as President of SAEM’s Academy for Women in Academic Emergency Medicine. SMK and CKK respectively serve on the Executive Committee and as Executive Staff for the American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM).

References

- 1.Hall KN, Wakeman MA. Residency-trained emergency physicians: their demographics, practice evolution, and attrition from emergency medicine. J Emerg Med 1999;17(1):7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holliman CJ, Wuerz RC, Chapman DM, Hirshberg AJ. Workforce projections for emergency medicine: how many emergency physicians does the United States need? Acad Emerg Med 1997;4(7):725–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ginde AA, Sullivan AF, Camargo CA Jr. National study of the emergency physician workforce, 2008. Ann Emerg Med 2009;54(3):349–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sullivan AF, Ginde AA, Espinola JA, Camargo CA Jr. Supply and demand of board-certified emergency physicians by U.S. state, 2005. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16(10):1014–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reiter M, Allen BW. The emergency medicine workforce: shortage resolving, future surplus expected. J Emerg Med 2020;58(2):198–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marco CA, Courtney DM, Ling LJ, et al. The emergency medicine physician workforce: projections for 2030. Ann Emerg Med 2021;78(6):726–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gettel CJ, Courtney DM, Janke AT, et al. The 2013 to 2019 emergency medicine workforce: clinician entry and attrition across the US geography. Ann Emerg Med 2022;80(3):260–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett CL, Sullivan AF, Ginde AA, et al. National study of the emergency physician workforce, 2020. Ann Emerg Med 2020;76(6):695–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett CL, Espinola JA, Sullivan AF, Clay CE, Samuels-Kalow ME, Camargo CA. Female emergency physician workforce in the United States, 2020. Am J Emerg Med 2022;52:255–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Association of American Medical Colleges. Percentage of U.S. medical school graduates by sex, academic years 1980–1981 through 2018–2019. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-12-percentage-us-medical-school-graduates-sex-academic-years-1980-1981-through-2018-2019#:~:text=In%201980%2D1981%2C%20only%2024.9,Line%20chart%20with%202%20lines. Accessed March 13, 2023.

- 11.Association of American Medical Colleges. Physician Specialty Data Report. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/physician-specialty-data-report. Accessed February 28, 2023.

- 12.Association of American Medical Colleges. U.S. Medical School Department Chairs by Chair Type and Gender. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/faculty-institutions/interactive-data/us-medical-school-chairs-trends. Accessed February 28, 2023.

- 13.Agrawal P, Madsen TE, Lall M, Zeidan A. Gender disparities in academic emergency medicine: strategies for the recruitment, retention, and promotion of women. AEM Educ Train 2020;4(Suppl 1):S67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuhn GJ, Abbuhl SB, Clem KJ, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) Taskforce for Women in Academic Emergency Medicine. Recommendations from the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) Taskforce on women in academic emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med 2008;15(8):762–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiler JL, Rounds K, McGowan B, Baird J. Continuation of gender disparities in pay among academic emergency medicine physicians. Acad Emerg Med 2019;26(3):286–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ting DK, Poonja Z, Lee K, Baylis J. Burnout crisis among young and female emergency medicine physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic: applying the six areas of worklife model. CJEM. 2022;24(3):247–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iyer MS, Wilson K, Draucker C, Hobgood C. Physician men leaders in emergency medicine bearing witness to gender-based discrimination. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6(1):e2249555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Jones R, Perumalswami CR, Ubel P, Stewart A. Sexual harassment and discrimination experiences of academic medical faculty. JAMA 2016;315(19):2120–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Association of American Medical Colleges. Understanding and Addressing Sexual Harassment in Academic Medicine. https://store.aamc.org/understanding-and-addressing-sexual-harassment-in-academic-medicine.html. Accessed April 4, 2023.

- 20.Silver MP, Hamilton AD, Biswas A, Warrick NI. A systematic review of physician retirement planning. Hum Resour Health 2016;14(1):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dewa CS, Jacobs P, Thanh NX, Loong D. An estimate of the cost of burnout on early retirement and reduction in clinical hours of practicing physicians in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Physician & Other Practitioners. https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-physician-other-practitioners. Accessed November 13, 2022.

- 23.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med 2007;147(8):573–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gettel CJ, Schuur JD, Mullen JB, Venkatesh AK. Rising high acuity emergency care services independently billed by advanced practice providers, 2013 to 2019. Acad Emerg Med 2023;30(2):89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gettel CJ, Canavan ME, Greenwood-Ericksen MB, et al. A cross-sectional analysis of high-acuity professional services performed by urban and rural emergency care physicians across the United States. Ann Emerg Med 2021;78(1):140–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gettel CJ, Canavan ME, D’Onofrio G, Carr BG, Venkatesh AK. Who provides what care? An analysis of clinical focus among the national emergency care workforce. Am J Emerg Med 2021;42:228–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ginde AA, Sullivan AF, Camargo CA Jr. Attrition from emergency medicine clinical practice in the United States. Ann Emerg Med 2010;56(2):166–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewiss RE, Silver JK, Bernstein CA, Mills AM, Overholser B, Spector ND. Is academic medicine making mid-career women physicians invisible? J Womens Health 2020;29(2):187–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, Orav EJ, Blumenthal DM, Jha AK. Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for Medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177(2):206–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenwood BN, Carnahan S, Huang L. Patient-physician gender concordance and increased mortality among female heart attack patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115(34):8569–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emergency Medicine News. The EMN Salary Survey: A Portrait of the Average EP Post-COVID. https://journals.lww.com/em-news/Fulltext/2023/03000/The_EMN_Salary_Survey__A_Portrait_of_the_Average.7.aspx#:~:text=Though%20the%20average%20hourly%20rate,versus%20five%20percent%20in%202017. Accessed March 13, 2023.

- 32.Association of American Medical Colleges. Active Physicians by Age and Specialty, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-age-specialty-2021. Accessed March 13, 2023.

- 33.American College of Emergency Physicians. Joint Statement on the Emergency Medicine 2023. Match Results. https://www.acep.org/news/acep-newsroom-articles/joint-statement-match-2023/. Accessed March 22, 2023.

- 34.Janke AT, Melnick ER, Venkatesh AK. Hospital occupancy and emergency department boarding during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5(9):e2233964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kilaru AS, Scheulen JJ, Harbertson CA, Gonzales R, Mondal A, Agarwal AK. Boarding in US academic emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Emerg Med 2023. Jan 19;S0196–0644(22)01328–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians during the first 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic. Mayo Clin Proc 2022;97(12):2248–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American College of Emergency Physicians Policy Statement. Overcoming Barriers to Promotion of Women and Underrepresented in Medicine (URiM) Faculty in Academic Emergency Medicine. https://www.saem.org/docs/default-source/saem-documents/position-statements/overcoming-barriers-to-promotion-of-women-and-underrepresented-in-medicine-(urim)-faculty-in-academic-emergency-medicine.pdf?sfvrsn=5ffe6f5b_3. Accessed March 23, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Society for Academic Emergency Medicine-Academy of Women in Academic Emergency Medicine. AWAEM Toolkit. https://issuu.com/saemonline/docs/saem_awaem_toolkit. Accessed March 23, 2023.

- 39.American College of Emergency Physicians. ACEP Calls for Stronger Protections for Emergency Physicians Who Raise Workplace Safety Concerns. https://www.acep.org/home-page-redirects/latest-news/acep-calls-for-stronger-protections-for-emergency-physicians-who-raise-workplace-safety-concerns/. Accessed March 23, 2023.

- 40.Choo EK, Kass D, Westergaard M, et al. The development of best practice recommendations to support the hiring, recruitment, and advancement of women physicians in emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(11):1203–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.