Abstract

We present the case of a 61-year-old man with known Morbus Barlow disease, who presented with postoperative myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest within 1 hour after minimally invasive mitral valve surgery owing to coronary artery occlusion by native mitral valve tissue.

Key Words: coronary embolism, coronary interventions, mitral valve surgery, myocardial infarction

Graphical abstract

History of Presentation

A 61-year-old male patient with known Morbus Barlow disease of the mitral valve presented with progressive dyspnea NYHA functional class III and dizziness for 3 weeks. On the suspicion of severe mitral valve regurgitation (MR), he was referred to our institution. Here he presented with bilateral lower limb edema, slight tachycardia (100 beats/min), a blood pressure of 110/75 mm Hg, and an early systolic murmur by auscultation. The initial echocardiographic assessment showed a severe holosystolic MR, severe dilatation of the left atrium with a concentrically hypertrophic left ventricle (LV) and normal left ventricular ejection fraction. The primary electrocardiogram was normal. Transesophageal echocardiography confirmed severe MR owing to Barlow's disease with prolapse of both leaflets in segment 2, deep indentation between segments P2 and P3, and ruptured chordae of segment 2 with flail-leaflet and annulus dilatation (Figures 1 and 2). Preoperative coronary angiogram showed right-sided dominance with relevant long coronary stenosis in the mid and apical left anterior descending artery (LAD) (both 70%) and first diagonal branch ostial 70% (Figure 3A).

Learning Objectives

-

•

To evaluate approaches for the preoperative investigations, intervention planning as well as identifying and minimizing perioperative and postoperative complications after valve surgery.

-

•

To identify and evaluate the possible reasons for electrocardiogram changes and possible coronary occlusion after valve surgery.

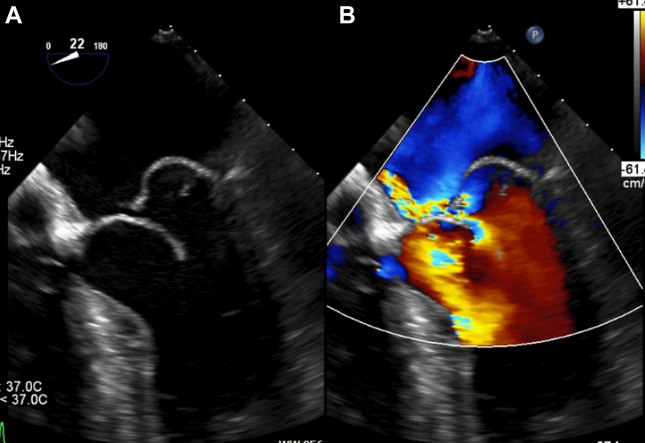

Figure 1.

Preoperative Transesophageal Echocardiography of the Mitral Valve

(A) Two-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography showing a ruptured chordae in the P2-segment with flail leaflet and prolapse in both leaflets of the same segment (posterior>anterior). (B) Mitral regurgitation in color Doppler echocardiography with an eccentric jet.

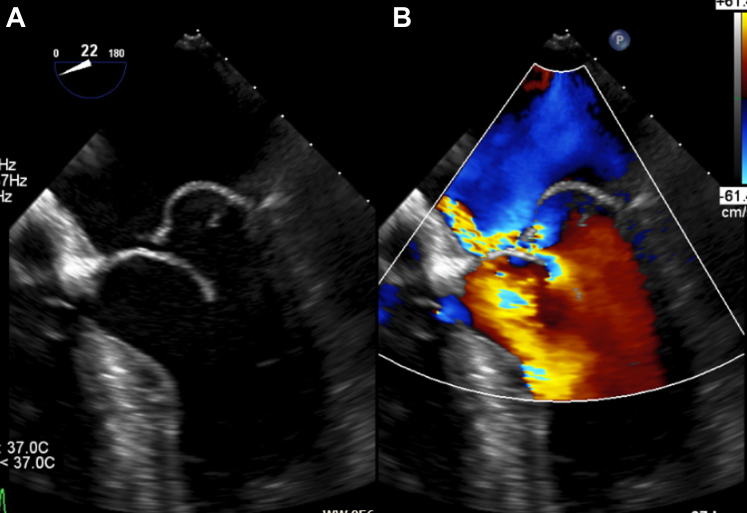

Figure 2.

3-Dimensional Reconstruction

Mitral valve with prolapse reconstructed in a 3-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography view.

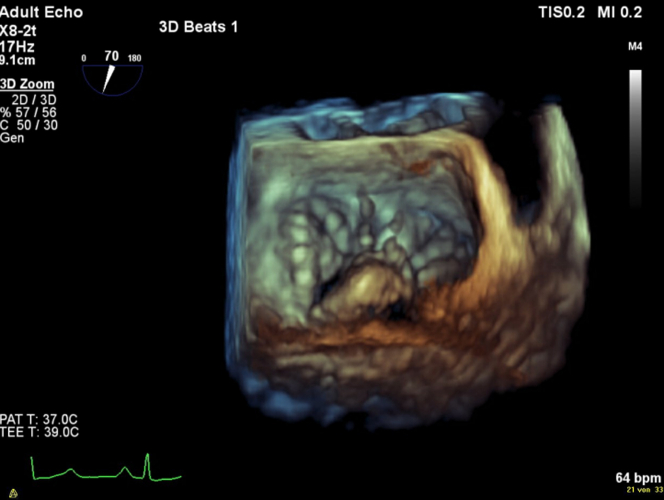

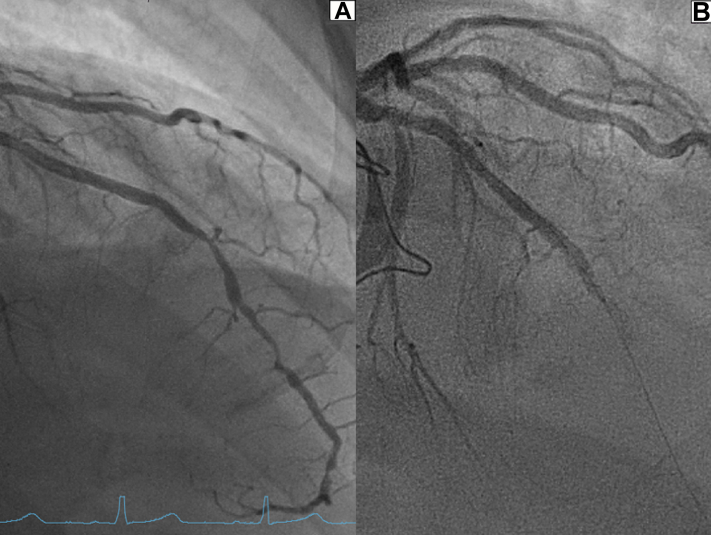

Figure 3.

Pre- and Postoperative Coronary Angiography

(A) Preoperative coronary angiography showing sequential LAD obstructions. (B) Postoperative total mid-LAD blockage with inserted coronary guide-wire. LAD = left anterior descending artery.

At the interdisciplinary heart board with given findings and a preoperative EuroSCORE of 1.02%, an accelerated elective surgical, minimally invasive procedure with staged percutaneous coronary intervention of the described coronary lesions was undertaken.1 This hybrid approach was chosen to shorten time on the heart-lung machine and because of an unfavorable landing zone for an arterial bypass graft in the distal LAD owing to diffuse atherosclerotic plaques (Figure 3A).

Surgical access was created by right lateral minithoracotomy with standard clamping of the ascending aorta and antegrade cardioplegia. The diagnosis of Barlow's mitral valve disease was confirmed intraoperatively with prolapse of both leaflets and ruptured chordae in the P2 segment with flail leaflet and thick leaflets with myxomatous degeneration. This step was followed by a broad triangular resection of the P2 segments, trimming of the edges, and cleft closure with leaving some prolapsing tissue, which was tried to incorporate into the suture line with the aim of a valve-preserving reconstruction. Owing to suboptimal results after multiple attempts with significant residual MR, it was decided to proceed to valve replacement with complete resection of the anterior leaflet. A bioprothesis (Edwards Lifesciences Perimount Magna Mitral, 29 mm) was implanted with subsequent good intraoperative result and without paravalvular leakage. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for postoperative monitoring. Shortly after arriving in the ICU, ST-segment elevation suddenly occurred in the anterior leads followed by ventricular fibrillation, which was successfully cardioverted into a stable sinus rhythm; however, with ongoing ST elevation (Figure 4). The patient was promptly transferred to the catheterization laboratory for acute percutaneous coronary intervention.

Figure 4.

Electrocardiogram

Ventricular fibrillation with cardioversion and subsequent ST-segment elevation.

Past Medical History

The patient was treated for arterial hypertension and dyslipidemia. Moreover, he had a regular follow-up with his outpatient cardiologist for mitral valve prolapse and a stable ectasia of the ascending aorta. In 2009, he had a radiofrequency ablation for atrioventricular nodal reentry tachycardia and remained in sinus rhythm since.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses of the symptoms and postoperative findings could be acute coronary occlusion with myocardial infarction (MI) owing to surgical lesion of a coronary artery, acute thrombosis or embolism of a coronary artery, acute heart failure, or plaque rupture.

Investigations

Echocardiography in the ICU after cardioversion showed new apical and anteroseptal akinesia with mildly reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (49%) without signs of an LV thrombus. Immediate coronary angiography revealed a total occlusion in the proximal LAD being the culprit lesion (Figure 3B). Based on previous findings, a plaque rupture with known stenosis was assumed. The coronary wire could be advanced smoothly, but after multiple balloon dilatations there was no good flow in the target vessel (TIMI flow grading system, grade I-II), at which point the operator decided to insert a suction catheter (Medtronic Export Advance aspiration catheter) assuming a thrombus.

Management

After aspiration with a suction catheter and consecutive drug-eluting balloon treatment in the LAD, subsequent flow was good (TIMI flow grade III) and the preoperatively described stenosis was treated successfully. The patient was henceforth hemodynamically stable and symptom free. By aspiration, a single thrombus was removed. The thrombus appeared macroscopically as a whitish, rod-like tissue with a size of 1.5 × 0.3 cm (Figure 5) that, after detailed histopathological examination, could primarily be assigned as a native heart valve or endocardial fragment (Figure 6). An embolus from a papillary fibroelastoma was also discussed, but considered unlikely given the unremarkable aortic valve morphology in the transesophageal echocardiography.

Figure 5.

Macroscopic Picture

Macroscopic picture of the embolus with an approximately 1.5 × 0.3 cm whitish, rod-like elastic tissue.

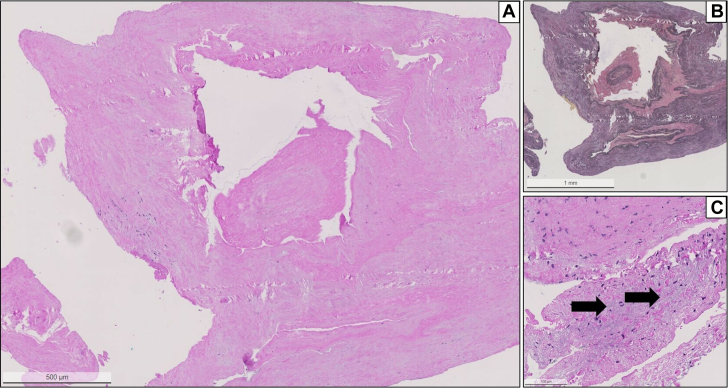

Figure 6.

Histology of the Embolus

(A) Histology of the material from the LAD shows a compact elastofibrotic tissue consistent with part of an atrioventricular valve (hematoxylin and eosin staining; original magnification ×2.5). (B) Elastica van Gieson staining demonstrate the elastic fibers in within the tissue (original magnification ×2.5). (C) Magnification with demonstration of focal mucoid degeneration (arrows). Note the absence of thrombosis or inflammatory activity. Abbreviation as in Figure 3.

Given guideline-compliant anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists for a total of 3 months after implantation of the bioprothesis, clopidogrel 75 mg/day was added for a further 3 months followed by aspirin monotherapy 100 mg/day.2

The remaining inpatient course was without complications.

Discussion

We present this uncommon case of coronary embolism owing to a native valve fragment with total occlusion of the LAD after minimally invasive mitral valve surgery.

Overall operative mortality after surgical mitral valve replacement has previously been reported as approximately 3.7%. The main complications include postoperative atrial fibrillation, rhythm disturbances requiring pacemaker implantation, bleeding with tamponade, and cardiac arrest.3 Rare but serious iatrogenic complications after valve surgery include injury of the left main or circumflex coronary artery, acute aortic insufficiency owing to surgical leaflet injury, left ventricular outflow obstruction, and intracoronary air embolism.4, 5, 6

The exact prevalence of acute MI with causative coronary embolus without underlying coronary sclerosis has been reported between 4% and 13%, but the exact prevalence is unclear in the acute setting.7,8 Coronary embolism is most commonly associated with implanted prosthetic aortic and mitral valve thrombosis, atrial fibrillation, patent foramen ovale or atrial septal defect with shunting, neoplasia, tumor disease, and endocarditis.9

In this case of coronary embolism from a native valve fragment, early detection and intervention was significant for the clinical outcome. Importantly, the diagnosis was assisted by immediate use of an aspiration catheter to remove and identify the embolus. To our knowledge, this case is the first of its kind to be reported. It, however, underlines that surgical care and continuous postoperative monitoring are crucial to manage such events. Moreover, it accentuates the importance of a preoperative coronary angiogram, which delivers information on the coronary anatomy and possible lesions. With this knowledge, identifying the culprit vessel and reason for occlusion is easier in case of postoperative acute MI. Among differential causes of periprocedural and postprocedural coronary embolization are torn calcium deposits from either the valve or the manipulated aorta, blood clots from clamping sites owing to retrograde perfusion, air embolism, and migrated valve tissue after resection. A repeated rinsing of the operative site with sterile saline solution and use of a suction catheter might reduce the risk of such embolism.

The decision to use a minimally invasive method in this patient was based on the favorable anatomical and functional conditions, as well as on experience from the surgical team routinized in mitral valve surgery. Available data suggest good procedural and long-term outcomes of minimally invasive mitral valve surgery in patients with primary MR, including Barlow’s disease.10

Hence, in high-volume centers with an experienced surgical team, Barlow’s disease with complex pathology will in most cases not be a contraindication for a standard, minimally invasive procedure. To avoid additional risks by surgical and operative interventions, an interdisciplinary heart team approach with detailed evaluation of the individual patient is essential.

Follow-up

The patient joined a rehabilitation program where he showed a good course of recovery. After completing the rehabilitation program, follow-up was done with his outpatient cardiologist. The patient could progressively improve his physical capacities. (New York Heart Association functional class I).

Conclusions

Although cases of postoperative coronary embolism are rare in general, this case of embolism by native mitral valve tissue after replacement is the first to be reported. Prompt identification and treatment of associated acute MI is the main target in preserving myocardial muscle and avoiding further complications. The reasons for coronary occlusion should be differentiated in any case.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.Nashef S.A., Roques F., Sharples L.D., et al. EuroSCORE II. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41:734–744. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs043. discussion 744-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vahanian A., Beyersdorf F., Praz F., et al. ESC/EACTS Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:561–632. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2022 Feb 18: PMID: 34453165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gammie J.S., Chikwe J., Badhwar V., et al. Isolated mitral valve surgery: the Society of Thoracic Surgeons adult cardiac surgery database analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;106:716–727. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.03.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paparella D., Squiccimarro E., Di Mauro M., Katsavrias K., Calafiore A.M. Acute iatrogenic complications after mitral valve repair. J Card Surg. 2022;37:4088–4093. doi: 10.1111/jocs.17055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alsaddah J., Alkandari S., Younan H. Iatrogenic left main coronary artery stenosis following aortic and mitral valve replacement. Heart Views. 2015;16:37–39. doi: 10.4103/1995-705X.153001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santiago M., El-Dayem M.A., Dimitrova G., Awad H. Missed diagnosis of iatrogenic acute aortic insufficiency after mitral valve surgery. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2011;49:26–31. doi: 10.1097/AIA.0b013e3181f89bb6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waller B.F. Atherosclerotic and nonatherosclerotic coronary artery factors in acute myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Clin. 1989;20:29–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shibata T., Kawakami S., Noguchi T., et al. Prevalence, clinical features, and prognosis of acute myocardial infarction attributable to coronary artery embolism. Circulation. 2015;132:241–250. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.015134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Popovic B., Agrinier N., Bouchahda N., et al. Coronary embolism among ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction patients: mechanisms and management. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11 doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.117.005587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borger M.A., Kaeding A.F., Seeburger J., et al. Minimally invasive mitral valve repair in Barlow's disease: early and long-term results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:1379–1385. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]