Summary

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai (HTHH) volcano eruption received worldwide attention due to its magnitude and potential effects on environment and climate. However, the operational sulfur dioxide (SO2) products mis-estimated SO2 emissions under volcanic conditions due to large uncertainties in the assumptions of SO2 plume altitude. That might have occurred in previous volcanic eruptions and misled understanding of the evolution of sulfate aerosols in the atmosphere and their impact on global climate. Here, we simultaneously retrieved the volcanic SO2 and its plume altitude from the Troposphere Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) and the Environment Monitoring Instrument-2 (EMI-2), exploring the SO2 burden, distribution, and evolution from January 14 to 17. We captured multiple eruptions with the second eruption emitting far more SO2 than the first. Total emissions exceeded 900 kt, significantly higher than those from operational products. Our inferred emission fluxes and injection heights offer valuable references for climate modeling and submarine volcano studies.

Subject areas: Earth sciences, Remote sensing

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Monitoring of SO2 emissions and fluxes for the 2022 HTHH volcano eruption

-

•

SO2 VCDs and its plume height retrieved from TROPOMI and EMI-2 observations

-

•

Capture multiple eruptions

-

•

Total SO2 emission exceeded 900 kt, much higher than that from operational products

Earth sciences; Remote sensing

Introduction

Sulfur dioxide (SO2) is a major air pollutant emitted from both anthropogenic activities and natural processes. Although volcanic emissions of SO2 are relatively weaker compared to anthropogenic sources,1 volcanic SO2 has a longer lifetime when injected into stratosphere and exerts larger influences on global climate.2,3,4,5,6 SO2, as the most widely measured gases during volcanic eruptions, can help understand the volcanic eruptive activities.7 For example, the SO2 emission rate may indicate the changes in the permeability of volcanic conduits, allowing predictions of the development of subsequent volcanic processes.8 Moreover, the volcanic SO2 has adverse effects on respiratory health.9,10 After the Holuhraun volcanic eruption in September 2014, the Iceland people, 250 km away from the eruption site, spent more asthma medication.9 In particular, SO2 from volcanic eruptions has a potentially strong impact on the global climate due to its subsequent conversion into aerosols and long-distance transport.11,12,13 For example, in 1815, the Tambora eruption caused global temperatures to drop by 0.4°C–0.7°C in the following year, leading to “the year without a summer.”14

On January 14, 2022, the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Haʻapai (HTHH) volcano (Tonga) erupted with massive volcanic gas and ash plumes to high levels. It is a submarine volcano in the South Pacific (20.54°S, 175.38°W). Note that most of the active volcanoes are submarine, while most of the submarine volcanoes cannot actually be discovered or quantified.15 However, this HTHH eruption was the most violent volcanic eruption so far in the 21st century.16 On January 15 and 17, 2022, it erupted again, producing vigorous atmosphere phenomena (an umbrella cloud, lighting, local and distal tsunamis),17,18 triggering a tsunami that affected Tonga and surrounding countries (e.g., Fiji and Australia). This eruption last a whole night, with the transiently volcanic plume of up to 58 km.19 According to World Bank reports,20 on January 16, 2022, only small parts of Hunga Tonga and Hunga Ha’apai islands remained, most of which had been blown apart, with 90M US dollars economic damage. In addition, dozens of flights delay and even ground caused by volcanic cloud drift have had an adverse impact on people’s travel.21

To gain insight into the atmospheric impacts and potential influences on the global climate system, it is crucial to quantify the emission flux of SO2 and its injection heights. Direct measurements of volcanic emissions are challenging given the destructive nature of volcano eruptions, while space-based observation can artfully fill this gap. Krueger3 observed the volcanic gas after the eruptions of the El Chichón volcano with the total ozone mapping spectrometer (TOMS). Later, the Global Ozone Monitoring Experiment (GOME),4 the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI),22 and the Ozone Mapping and Profiler Suite (OMPS)23 have also been applied to monitor the burden and evolution of volcanic SO2.24 The current volcanic inventory of SO2 emissions is mainly derived from TOMS and OMI observations. Unfortunately, TOMS is now unable to collect data. And OMI, with a nadir spatial resolution of 13 × 24 km2, suffers from the reduction of spatial coverage due to the blockage in the cross-track positions (also known as “row anomaly”).25 OMPS can be used for the extension of the volcanic SO2 inventory. However, the along-track and across-track coverage of OMPS is 50 km, which limits the availability of OMPS data.26 In October 2017, the TROPOsphere Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) onboard the Sentinel-5 Precursor (S-5P) satellite was launched. The nadir footprint is 3.5 × 5.5 km2 after October 2019.27 With strength of high resolution, it has the ability to monitor column concentrations of SO2 globally. Subsequently, the Environment Monitoring Instrument 2 (EMI-2) is also onboard with an along-track coverage of 13 km and an across-track of 20 km.28 Unlike the TROPOMI’s overpass time at 1:30 p.m. local time, EMI-2’s overpass time is at 10:30 a.m. local time, which is beneficial to improving the time resolution of satellite observations.29 A variety of algorithms have been developed to better retrieve SO2 vertical column densities (VCDs), including differential optical absorption spectrometer (DOAS),30 linear fit (LF),31 principal component algorithm (PCA),32 and covariance-based retrieval algorithm (COBRA).33 Under volcanic conditions, most of SO2 products from ultraviolet (UV) measurements provide the column, but no information on the plume height is available. However, the SO2 plume height is crucial for aircraft safety and atmospheric changes. Several infrared (IR) SO2 products (e.g., Infrared Atmospheric Sounding Interferometer (IASI on MetOp-A/B) product) provide the plume altitude.34 While, the SO2 column from IR measurements has weaker sensitivity in the lower troposphere and incomplete spatial coverage, which makes SO2 columns fairly rapidly drop below the detection limit of about 6 Dobson Unit (DU, 1 DU = 2.69 × 1016 molecule cm−2).35

Here, we aim to analyze the evolution of SO2 plumes from the 2022 HTHH volcano eruption and estimate emission flux, which aids the future explorations of its environmental and climate effects. The SO2 columns and plume heights are retrieved directly using the optimal estimation (OE)36,37 method from both TROPOMI and EMI-2 level 1 radiance observations. Through the observations, daily distribution, burden, and flux of SO2 are derived and used to estimate total SO2 emissions. The results presented here could offer insights on the intensity of this eruption and the areas affected. The reported emission intensity and injection heights can be further used for chemical transport modeling and climate modeling.

Results

Derived burden of SO2 of the first eruption

The HTHH volcano erupted at 4:20 a.m. local time on January 14, 2022, and EMI-2 provided the measurements of SO2 columns in the eruption cloud ∼6 h after the eruption onset (Figure 1). At 10:30 a.m. local time on January 14, EMI-2 OE retrievals suggested that SO2 column concentrations reached up to 25 DU and plume height reached as high as 17 km above the volcano. The measured SO2 burden of that was about 45 kt. 3 h after the EMI-2 detection, in the volcanic plume, an SO2 burden of approximately 52 kt was measured from TROPOMI OE product. The maximum SO2 column measured by TROPOMI was ∼22 DU, smaller than that from EMI-2. EMI-2 OE SO2 observations are commonly noisier than those from TROPOMI due to relatively lower spatial resolution. Both products show excellent spatial agreement and suggest a distinctive “ring-shape” spatial pattern. Higher SO2 concentrations were detected at the edge of the expanding cloud, while the lower SO2 concentrations were found near the cloud core, with even some areas having no SO2 or lower than the instrumental detection (Figure 1). This kind of distribution pattern is unusual but can be explained by the scrubbing of SO2 by the co-emitted water. The comparison of SO2 columns from TROPOMI and EMI-2 OE products on January 14 was shown in Figure S1, with a correlation coefficient of 0.51 and a mean bias of 1.7 DU. We interpreted the difference as a diagnosis of the diffusion and continued emissions from eruption (approximately 3 h difference between the observations). This conclusion is supported by the wind direction from the radiosonde sounding at Pago Pago (American Samoa).38 Besides, TROPOMI inferred plume altitudes were lower than those from EMI-2, partly caused by deposition over the detection interval.

Figure 1.

SO2 plumes observed from satellites after Tonga eruption on January 14, 2022

SO2 vertical column density measured by (A) EMI-2 and (B) TROPOMI on January 14, 2022. The second rows are the same as the first, but for SO2 plume altitudes observed from (C) EMI-2 and (D) TROPOMI, respectively.

For the validation of SO2 columns, independent TROPOMI operational DOAS SO2 product, OMI PCA SO2 product, OMPS PCA SO2 product, and OMPS LF SO2 product were applied and compared with our OE products. These independent UV satellite level 2 products provide SO2 columns based on a pre-assumption of SO2 center of mass altitude (CMA). According to the SO2 plume altitudes on January 14 in the Tonga volcanic case, we chose the reported SO2 columns with assuming the SO2 concentrated in the lower stratosphere (STL) that was more applicable to the 2022 HTHH eruption. The overpass time of OMI, OMPS, and TROPOMI are similar, so the correlation coefficient of SO2 columns (>0.78) from the SO2 products used for validation and from TROPOMI OE product was higher than that between EMI-2 and TROPOMI OE products (Figures 2 and 3). Especially, the SO2 columns from TROPOMI OE product are consistent with that from TROPOMI DOAS and OMPS PCA product, with the correlation coefficient of >0.95 and the mean bias of <0.2 DU. The small differences might come from the algorithms (OE, DOAS, and PCA) and the instrument resolutions (TROPOMI and OMI). Although the resolution of OMPS is much lower than that of TROPOMI, which results in the high-SO2-value area the OMPS PCA product being larger and the low-SO2-value area it being smaller than the TROPOMI OE product, the OMPS PCA product still has a high correlation with the TROPOMI product. It indicates that the resolution differences (TROPOMI, OMI, and OMPS) and the algorithm differences (OE, PCA, and DOAS) have little impact on the SO2 observations. However, the SO2 columns from OMPS LF product were larger than those from OMPS PCA product, with a mean bias of 3.14 DU (See Figure S2). This might mainly come from the differences in the retrieval algorithms. Moreover, SO2 from OMPS LF product was larger than that from other products, indicating a potential overestimation of volcanic SO2 column in OMPS LF product. Note that we only used the STL SO2 columns from TROPOMI DOAS, OMI, and OMPS PCA products. Under volcanic conditions, without the knowledge of SO2 plume altitude, it was likely to use SO2 columns retrieved with wrong a priori SO2 profiles, which would lead to potentially large biases in the subsequent studies (See Figures S3–S6).

Figure 2.

SO2 distribution from four satellites products

Distribution of SO2 VCDs from (A) TROPOMI DOAS product with CMA of ∼15 km, (B) OMI PCA product with CMA of ∼17 km, (C) OMPS PCA product with CMA of ∼17 km and (D) OMPS LF product with CMA of ∼17 km on January 14, 2022.

Figure 3.

Comparisons of SO2 columns from different satellite products on January 14, 2022

Scatterplot of SO2 columns collected from TROPOMI OE product and from other four SO2 product with the CMA of lower stratosphere, including (A) TROPOMI DOAS product, (B) OMI PCA product, (C) OMPS PCA product and (D) OMPS LF product, on January 14, 2022.

The heights and distribution of aerosols and clouds on January 14 were detected from one CALIPSO orbit with the 532 nm total attenuated backscatter (TAB) data and vertical feature mask (VFM) image version 3.41 (See Figure S7). TAB data represent that the stronger cloud (gray scales) and weaker cloud and aerosol (red, orange, and yellow shades) were located 15–20 km at the volcanic feature. Combined the TAB and VFM, it was obvious that CALIPSO captured the volcanic plumes after the Tonga eruption, which show good agreement with the plume height retrieved using the OE algorithm.

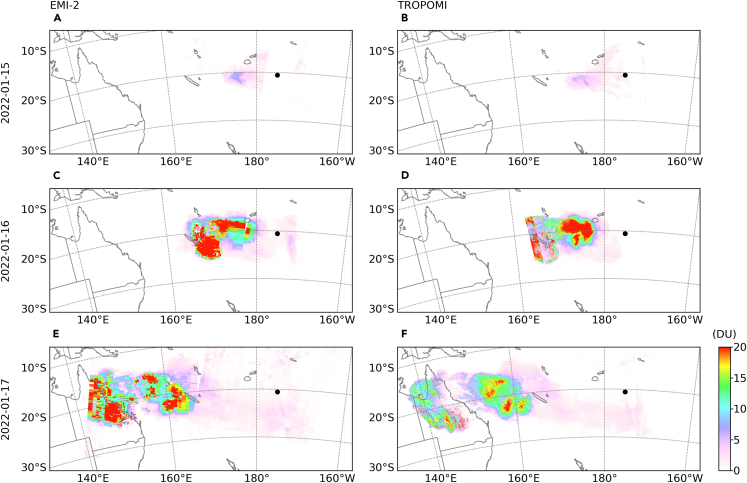

The subsequent evolution of the SO2 plume is shown in Figures 4 and S10. On January 15, under easterly winds, the SO2 plume from the Tonga volcanic eruption migrated to the west and diluted (Figure 4). Both TROPOMI and EMI-2 detected a growing area of SO2 plume, but maximum SO2 column concentrations generally declined (EMI-2: maximum ∼8 DU, SO2 burden ∼42 kt) under the influences of winds. The declines could be caused by both deposition of SO2 over time and detection limitation of the instrument. TROPOMI observed a similar SO2 burden of about 50 kt on January 15. It was worth noting that there is not any SO2 emission detected by the UV satellite on January 15, 2022, before the next major eruption at 17:10 local time. However, the geostationary GEOS-West Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI) imagery (https://worldview.earthdata.nasa.gov/) shows that several sporadic “puffs” from the HTHH volcano continued before the second major eruption (e.g., on January 15 at 7:00 and 10:10 local time). This could be explained by the detection limitation of the UV satellite observations and the interference of the clouds and aerosols produced by the volcanic eruptions.

Figure 4.

SO2 distribution from January 15 to 17, 2022

Distribution of SO2 column detected by EMI-2 (left panels) and TROPOMI (right panels) on (A and B) January 15, (C and D) 16 and (E and F) 17, 2022.

Derived burden of SO2 of the subsequent eruptions

At 5:10 p.m. local time on January 15, the HTHH volcano erupted for the second time, however, the plume was not captured by the satellite until January 16, since the overpass times of satellites on January 15 were before 5:10 p.m. On January 16, SO2 plume drifted further west and both EMI-2 and TROPOMI retrievals suggested Fiji, Vanuatu, and New Caledonia were covered by the SO2 clouds. At the same time, due to the second eruption, the SO2 increased again. The SO2 columns in most areas between Fiji and New Caledonia were above 20 DU, especially in New Caledonia, where the SO2 concentrations were even as high as 40 DU. The SO2 burden inferred for January 16 was 652 kt with EMI-2 and 572 kt with TROPOMI (Figures 4C and 4D)). On January 17, SO2 plume from the Tonga eruption continued to drift westward. Both TROPOMI and EMI-2 observed two relatively intact plumes, and the boundary between the two plumes became more distinct. The altitude of the plumes over vast regions was below 10 km, but in northwest New Caledonia, plumes still existed above 15 km (See Figure S8), suggesting potential influences on the stratosphere. We estimated that the SO2 burden observed by EMI-2 was 809 kt, consistent with that observed by TROPOMI (794 kt). An increased SO2 burden observed on January 17 compared to that on January 16 was probably due to a third eruption or continued emissions of SO2 during the period between these two observations.

The possible volcanic feature heights from CALIPO (15–30 km) were higher than that from TROPOMI and EMI observations (15–20 km) on January 16. This may be due to the fact that the overpass time of CALIPSO is around 15:00 p.m. local time, while the overpass times of TROPOMI and EMI-2 are 1:30 p.m. and 10:30 a.m. local time, respectively (See Figure S9). Moreover, the current OE algorithm only considers the SO2 profile shape of a single-peak, but the actual situation is more complex, which will also lead to errors in the volcanic SO2 height inversion. On January 17, CALIPO images show that most of the aerosol heights were below 5 km, similar to that from OE products (See Figure S10).

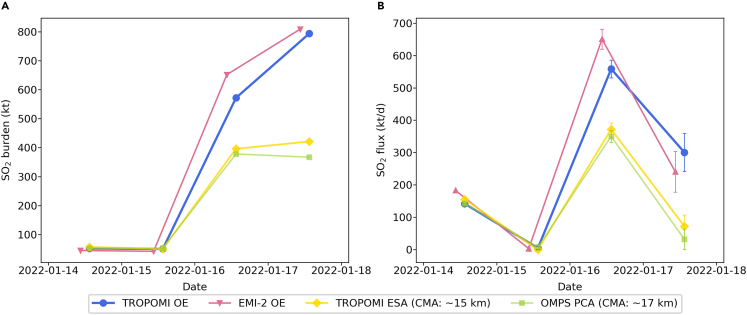

Estimates of SO2 emissions from Tonga eruption

Emitted SO2 from the Tonga eruption was likely to be oxidized in the atmosphere and experience deposition processes.13,39 To estimate the emission flux of SO2, we followed previous studies to assume that SO2 from volcano eruption is exponentially decayed, with a wide e-folding time of 5–35 days.2,15 Figure 5 illustrates the time series of SO2 burdens and SO2 flux from January 14 to 17, 2022, derived from TROPOMI and EMI-2 observations retrieved using the OE algorithm. On January 14, the estimated SO2 emission flux with TROPOMI (142 kt d−1) was lower than that with EMI-2 (183 kt d−1), as the volcano continued to emit SO2 during the observation period but at a slower rate than the initial rate. The total SO2 emissions from the first Tonga eruption were about 45–54 kt from TROPOMI and EMI-2 OE products, comparable to the estimated emissions from the STL SO2 columns from TROPOMI DOAS, OMI, and OMPS PCA products.

Figure 5.

Time series of SO2 burden and emission flux

Time series of (A) SO2 burden and (B) SO2 emission flux (right y axis) of the 2022 HTHH eruption. SO2 burden was observed from EMI-2 OE product (red triangle line) at 10:30 a.m. LT and TROPOMI OE (blue circle line), TROPOMI ESA (yellow diamond line) and OMPS PCA (green square line) products at 1:30 p.m. LT, respectively. Daily SO2 flux was derived with an e-folding time of 5–35 days.

Comparing the SO2 burdens and emissions from different SO2 products on January 14, we found that OMPS LF product showed larger SO2 burden and flux than other products (See Table S1; Figure 5). This was seen in the comparisons of SO2 columns between these products. The mean SO2 flux derived from EMI-2 OE product was close to 0 on January 15. It means that the SO2 emission was smaller than its sedimentation during the observation period between on January 14 to 15. The SO2 fluxes from EMI-2 were 651 kt d−1 and 241 kt d−1 on January 16 and 17, respectively. The SO2 flux derived from TROPOMI OE product showed generally good agreement with that from EMI-2 OE product, with the value of 559 kt d-1 and 301 kt d−1 on January 16 and 17, respectively. Compared with the SO2 flux from EMI-2, the SO2 flux from TROPOMI was less on January 16 and higher on January 17. This difference was associated with the complete coverage of the observation products on these two days. After January 17, the SO2 flux of Tonga volcano has shown negative values, possibly due to overestimation of e-folding and limitations of satellite observation limits. It indicated that the Tonga volcano stopped emitting SO2 into the atmosphere. Eventually, we estimated that the Tonga eruption produced 916 kt and 940 kt SO2 over January 14 to 17, based on TROPOMI and EMI-2 OE SO2 products, respectively. The SO2 emission is similar to the result estimated from the Infrared Atmospheric Sounding Instrument (>1000 kt),40 a high-spectral-resolution infrared space-borne instrument. To subtract the initial SO2 emissions of 45–52 kt on January 14, the remained emissions of 871–898 kt were produced by the eruption on January 15. Obviously, larger SO2 injections were observed from the OE products and IASI observations than previously thought. The SO2 emissions from TROPOMI operational DOAS SO2 product were about 400–500 kt, smaller than those estimated from OE products (https://so2.gsfc.nasa.gov/tropomi_2019_now.html#2022).41 We inferred that the bias was from the underestimation on January 17, since the operational estimation of Tonga SO2 emissions only from the STL products. However, the SO2 sedimentation was significant over time. The SO2 plume heights were lower than in the lower stratosphere layer, which was used in the operational estimations (See Figure S8).

Discussions

Given the scrubbing of SO2 in a water-rich plume, SO2 produced by most of submarine volcano eruptions cannot be detected or quantified by UV satellite-based observations. Until this 2022 HTHH eruption, only ∼12 submarine eruptions had provided enough energy to produce SO2 plume that breached the ocean surface and produced detectable SO2 emissions.38 Dramatically, the 2022 HTHH volcano eruption occurred to produce sufficient SO2 and received worldwide attention due to its magnitude and potential effects on environment and climate. Here we explored the burden, distribution, and evolution of SO2 based on observations from two space-based instruments, TROPOMI and EMI-2. We further quantified the emission of SO2 over January 14 to 17 to be over 900 kt. Since TOMS was launched in 1978 to observe volcanic SO2 emissions, the total SO2 emissions from this eruption of the 2022 HTHH eruption have been only lower than the 23 recorded volcanic emissions (See Table S2), making it the 24th of the total amount of volcanic SO2 eruptions captured using satellite-based instruments. Furthermore, compared with the SO2 emissions from the anthropogenic hotspots in 2019, except for the emissions from the 1st anthropogenic SO2 emission hot spot, Norilsk smelter site in Russia, the SO2 emissions from the 2022 HTHH eruption had been much larger than the remaining anthropogenic SO2 emissions sources (See Table S3).1 The SO2 emissions of this round of Tonga eruption are only second to the yearly anthropogenic SO2 emissions from eight countries (i.e., India, Russia, China, Saudi Arabia, Mexico, Iran, South Africa, and Turkey, See Table S4).

The Volcanic Explosivity Index of this eruption is 4, given that the radius of the umbrella cloud produced by the eruption was ∼120 km.42 However, the SO2 emissions derived from those aforementioned satellite products were much lower than the mean SO2 emissions yield for magmatic eruptions with VEI of 5 (2300 kt). We interpreted that as the large amount of water carried by the submarine volcano eruptions. The conclusion can be supported by the ∼6 days SO2 e-folding time of this 2022 HTHH volcano eruption that is lower than most of the e-folding time from other volcanos. And the relatively short lifetime of SO2 might be due to the huge mass of water vapor (a source of OH) that oxidizes SO2 to SO4−.

Due to the lack of information about SO2 plume altitudes, the SO2 emissions over January 14 to 17 based on operational product were less than 600 kt,29,38,43 a low estimation of about 300 kt than the emissions from the OE products. The OE SO2 products would improve the global surface temperature estimation based on the volcanic SO2 emissions. This might also occur in previous volcanic eruptions, causing miscalculation of the impact on global climate change.13

The results from the two different instruments are generally consistent and complementary. It further demonstrated that TROPOMI and EMI-2 have the ability to extend the records of volcanic emissions, with smaller retrieval uncertainty than other satellite products (Figure 6). Given that most of the volcanoes are located in remote areas, a space-based instrument provides a useful reference for intensity and the process of volcano eruptions globally. Through the retrieved column concentrations of SO2, we can better understand the formation mechanism of volcanoes and implement risk management in advance. Long-term and persistent data from satellites makes it possible to integrate multiyear measurements and volcanic activities. Moreover, the SO2 VCDs can be assimilated by chemical transport models to better represent the spatiotemporal variability of volcanic SO2 emissions and to better understand its environmental impacts. Our inferred emission flux over time and injection heights offer also value for climate modeling to understand the evolution of ashes in both troposphere and stratosphere, the impacts on global climate, and the impacts on stratosphere ozone.

Figure 6.

SO2 retrieval uncertainty from four satellites products

The frequency of SO2 distribution from (A) TROPOMI OE product, (B) EMI-2 OE product, (C) TROPOMI operational product and (D) OMPS operational product in clean Pacific areas. Solid line—the Gaussian function fitted by the SO2 product.

Limitations of the study

Previous observations mostly focused on the distribution of SO2 concentration; then, analyzed the emission rate of volcanic SO2. However, due to the impact of SO2 profiles in retrieval based on satellite-based observations, the mis-estimations of volcanic SO2 emissions might occur. Therefore, unlike previous researches, this paper involved the emission height of SO2 and comprehensively considered the impact of SO2 plume height on the concentration. Unfortunately, the once-a-day observation frequency and low spatial resolution of satellites cannot accurately capture the details of volcanic eruptions. In addition, we did not consider the impact of aerosols, volcanic ash, etc. related to volcanic eruptions on the observed spectra. Due to future changes in aerosol content, the aerosol scattering and absorption should also be added in the observations. This aspect, as well as the impact of the properties of particulate matter such as volcanic ash on the volcanic SO2 retrieval, needs to be analyzed in a model-based setting.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| TROPOMI operational data | Copernicus Open Access Hub | https://s5phub.copernicus.eu/dhus/#/home |

| TROPOMI OE SO2 | This paper | https://github.com/Xiacz/Tonga |

| EMI-2 OE SO2 | This paper | https://github.com/Xiacz/Tonga |

| OMI PCA SO2 | NASA | https://aura.gesdisc.eosdis.nasa.gov/data/Aura_OMI_Level2/OMSO2.003/ |

| OMPS PCA SO2 | NASA | https://measures.gesdisc.eosdis.nasa.gov/data/SO2/OMPS_NPP_NMSO2_PCA_L2.2/ |

| OMPS LF SO2 | NASA | https://snpp-omps.gesdisc.eosdis.nasa.gov/data/SNPP_OMPS_Level2/OMPS_NPP_NMSO2_L2.2/ |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Python 3.9 | Python Software Foundation | https://www.python.org/ |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Cheng Liu (chliu81@ustc.edu.cn).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique materials.

Data and code availability

-

•

The source data is available as listed in the key resources table.

-

•

The code associated with the retrieval algorithm is available from the lead contact upon reasonable request.

-

•

Any additional information about the paper is available from the lead contact upon reasonable request.

Method details

Space-based instrument and data

We used two onboard sun-synchronous instruments, TROPOMI and EMI-2, to infer the emissions of SO2 from the Tonga volcano eruption.17,18 Both are two-dimensional push-broom imaging spectrometers and are able to monitor global distributions of SO2 column once a day.13,19 The TROPOMI instrument onboard the Sentinel-5 Precursor (S-5P) satellite considers 8 spectral channels.44 Band 3 covers the spectra from 302 to 397 nm, with a spectral resolution of 0.5 nm full width at the half maximum (FWHM) and a spectral sampling of 0.2 nm/pixel. It has 450 cross-track positions of approximately 2600 km, and a finer spatial resolution (3.5 km × 5.5 km after August 2019).27 The ascending equator overpass time is at 1:30 p.m. local time (LT). The S-5P operational processing system provides an offline TROPOMI operational SO2 product retrieved using DOAS algorithm. TROPOMI operational DOAS SO2 product reported three available volcanic SO2 columns according to assumed a priori SO2 profiles (i.e., lower troposphere (TRL) with CMA of ∼1 km, mid-troposphere (TRM) with CMA of ∼7 km and lower stratosphere (STL) with CMA of ∼ 15 km). The accuracy of TROPOMI operational DOAS SO2 product under volcanic conditions has not been validated. In this study, we compared the TROPOMI operational product based on the Tonga volcanic eruption event.

The Environmental Monitoring Instrument (EMI)-2 is onboarded the GF-5 02 satellite,28 which was launched on September 7, 2021 (https://space.skyrocket.de/doc_sdat/gf-5.htm). EMI-2 considers 4 spectral channels,28 and the ultraviolet 2 (UV2) band measures spectra from 302 nm to 402 nm. The spectral resolution and sampling of EMI-2 are 0.5 nm FWHM and 0.09 nm/pixel, respectively. It covers a 2600 km cross-track swath with 70 positions. The nadir footprint of EMI-2 is 13 km × 20 km, much larger than that of TROPOMI. Different from the overpass time of S-5P, the equator ascending crossing time of GF-5 02 is around10:30 a.m. LT.28

For the comparison with the TROPOMI and EMI-2 data, we used the commonly used OMI and OMPS SO2 product. For OMI, the operational SO2 retrievals derived using the PCA algorithm. The OMI pixel size varies from the nadir (13 km × 24 km) to the edge (28 km × 150 km). For OMPS, the SO2 products retrieved using the PCA and LF algorithms were used to validate. The spatial resolution of OMPS is about 50 km × 50 km at the nadir footprint size, lower than that of TROPOMI and EMI-2. Both the overpass-times of OMI and OMPS are close to S-5P. In OMI and OMPS SO2 product, three different volcanic SO2 columns are reported with the CMAs of ∼3 km (TRL product), ∼8 km (TRM product), and ∼ 17 km (STL product).

For the case of the Tonga eruption, we used the STL columns from TROPOMI operational DOAS, OMI PCA, OMPS PCA and OMPS LF SO2 products to validate the OE retrievals. In addition, the ash plume from CALIOP/CALIPSO space-born lidar observations also used to compared with the SO2 plume altitudes retrieved using OE algorithm.

Retrieval algorithm

The OE retrieval algorithm, initially applied for SO2 retrieval in GOME-2,45 was applied to retrieve SO2 vertical column densities (VCDs) using solar irradiance and Earth’s backscattered radiance spectra measured by TROPOMI and EMI.19,23 We previously demonstrated that our TROPOMI OE SO2 product exhibited a smaller retrieval uncertainty (standard deviation) of 0.3 DU and better consistency with ground-based Multi-axis Differential Optical Absorption Spectrometer (MAX-DOAS) measurements, compared with the TROPOMI operational SO2 products.37 In order to adapt the OE algorithm to EMI-2 measurements, we have performed several sensitivity tests to improve the spectral fitting process.46 As a two-dimensional spectrometer, the cross-track and wavelength dependent bias existed in the EMI-2 reflectance, which would lead to failure in the SO2 retrieval. The systematic bias can be eliminated by correcting the measured reflectance using radiometric calibration.47 From the radiometric correction factor in EMI-2 (See Figure S11), the measured reflectance was greater than the simulated one. The overestimation of the measured reflectance was over 20% with the wavelength of < 309 nm. With the increasing of wavelength, the overestimation was decreasing to within 10%. Corrected measurement error, including minimum floor noise (See Figure S12A) and corrected ratio in north and south hemisphere (See Figures S12B and S12C)), was derived and used to constrain the retrieval. After that, the suitable fitting window for EMI-2 was selected of 313.0∼323.0 nm.

Complying with the retrieval settings, the retrieval uncertainty was about 0.2 DU for the EMI-2 OE SO2 product, approximately two-thirds of that of the TROPOMI OE SO2 product (Figure 6). Since TROPOMI has a smaller footprint than EMI-2, the standard error of TROPOMI was roughly 2.5 times smaller than that of EMI-2. For volcano eruption, we used a Gaussian plume with a FWHM of 0.5 km and an altitude of plume peak of the retrieved SO2 plume height,45 instead of GEOS-Chem simulated SO2 profiles as the a priori, in this study. To deal with enhanced SO2 column from volcano eruption, we simulated the radiance with the Vector Linearized Discrete Ordinate Radiative Transfer model (VLIDORT) on a finer wavelength grid of 0.02 nm.48 The initial SO2 plume altitude was chosen to be 10 km, and SO2 columns and plume heights were then retrieved simultaneously.

We examined also the sensitivity of retrievals to initial plume altitudes (See Figure S12), and we found retrieved SO2 column with an initial plume altitude of 5 km was highly correlated with that of 10 km (a correlation coefficient of 0.99 and a mean bias of -10.7%). When SO2 concentrations were relatively low, the retrieved plume height was close to the initial altitude. Under high concentrations, retrieved plume height was less affected by initial altitude, and mean bias declined to 3.3%.

To infer daily measured SO2 burden, we used a fixed threshold of 3 times of the standard deviation to exclude data smaller than the threshold. The thresholds of TROPOMI and EMI-2 OE product, TROPOMI and OMPS operational SO2 product were 0.9 DU, 0.6 DU, 1.5 DU and 0.3 DU, respectively (See Table S1; Figure 6). A discrete time series of SO2 burden was calculated by multiplying SO2 column by pixel size. Given oxidation and deposition of SO2 in the atmosphere, we used an exponential function to represent SO2 loss.49 The “delta-M” method50 was applied to calculate constant SO2 flux during the time interval, based on mass conservation. The SO2 retrieval obtained from TROPOMI and EMI-2 retrieved using the OE algorithm is available online at https://zenodo.org/record/6034207#.YgT1ZlhBy3I.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the 2021 Guangdong Provincial Department of Science and Technology Research Platform Project, Guangdong Provincial Smart Vocational Education Engineering Technology Research Center (2021A118), Innovation Team Project of Colleges and Universities of Guangdong Provincial Department of Education (Natural Science) (2022KCXTD047), National Natural Science Foundation of China (42225504) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3700100). The authors would like to thank the European Space Agency (ESA) for providing the Sentinal-5 Precursor products. TROPOMI was developed by ESA and The Netherlands Space Office.

Author contributions

C.X., C.L., and M.G. designed the research. C.L. conceived and organized the study, and provided financial support. Z.C. and Q.L. contributed to the interpretation and helped improve the paper. H.W. provided the cloud information. C.X. and M.G. wrote the manuscript with specific inputs from C.L., Z.C., H.W., and Q.L. All co-authors commented on the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: March 8, 2024

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2024.109446.

Contributor Information

Cheng Liu, Email: chliu81@ustc.edu.cn.

Meng Gao, Email: mmgao2@hkbu.edu.hk.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Dahiya S., Anhäuser A., Farrow A., Thieriot H., Chanchal A., Myllyvirta L. Delhi: Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air & Greenpeace India; 2020. Ranking the World’s Sulfur Dioxide (SO2) Hotspots: 2019-2020 A Closer Look at the Colourless Gas that Is Poisoning Our Air and Health. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorkavyi N., Krotkov N., Li C., Lait L., Colarco P., Carn S., DeLand M., Newman P., Schoeberl M., Taha G., et al. Tracking aerosols and SO2 clouds from the Raikoke eruption: 3D view from satellite observations. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2021;14:7545–7563. doi: 10.5194/amt-2021-58. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krueger A.J. Sighting of El Chichón sulfur dioxide clouds with the Nimbus 7 total ozone mapping spectrometer. Science. 1983;220:1377–1379. doi: 10.1126/science.220.4604.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisinger M., Burrows J.P. Tropospheric Sulfur Dioxide observed by the ERS-2 GOME instrument. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1998;25:4177–4180. doi: 10.1029/1998GL900128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohno M., Utsugi M., Mori T., Kita I., Kagiyama T., Tanaka Y. Temporal variation in the chemical composition (HCl/SO2) of volcanic gas associated with the volcanic activity of Aso Volcano, Japan. Earth Planets Space. 2013;65:e1–e4. doi: 10.5047/eps.2012.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carn S.A., Fioletov V.E., Mclinden C.A., Li C., Krotkov N.A. A decade of global volcanic SO2 emissions measured from space. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:44095. doi: 10.1038/srep44095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paez P.A., Cogliati M.G., Caselli A.T., Monasterio A.M. An analysis of volcanic SO2 and ash emissions from Copahue volcano. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 2021;110 doi: 10.1016/j.jsames.2021.103365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campion R., Delgado-Granados H., Legrand D., Taquet N., Boulesteix T., Pedraza-Espitía S., Lecocq T. Breathing and coughing: The extraordinarily high degassing of popocatépetl volcano investigated with an So2 camera. Front. Earth Sci. 2018;6 doi: 10.3389/feart.2018.00163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlsen H.K., Valdimarsdóttir U., Briem H., Dominici F., Finnbjornsdottir R.G., Jóhannsson T., Aspelund T., Gislason T., Gudnason T. Severe volcanic SO2 exposure and respiratory morbidity in the Icelandic population – a register study. Environ. Health. 2021;20:23. doi: 10.1186/s12940-021-00698-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwasawa S., Kikuchi Y., Nishiwaki Y., Nakano M., Michikawa T., Tsuboi T., Tanaka S., Uemura T., Ishigami A., Nakashima H., et al. Effects of SO2 on respiratory system of adult miyakejima resident 2 years after returning to the Island. J. Occup. Health. 2009;51:38–47. doi: 10.1539/joh.L8075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt A., Leadbetter S., Theys N., Carboni E., Witham C.S., Stevenson J.A., Birch C.E., Thordarson T., Turnock S., Barsotti S., et al. Satellite detection, long-range transport, and air quality impacts of volcanic sulfur dioxide from the 2014–2015 flood lava eruption at Bárðarbunga (Iceland) J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2015;120:9739–9757. doi: 10.1002/2015JD023638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kandlbauer J., Hopcroft P.O., Valdes P.J., Sparks R.S.J. Climate and carbon cycle response to the 1815 Tambora volcanic eruption. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013;118:12497–12507. doi: 10.1002/2013JD019767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuo M., Zhou T., Man W., Chen X., Liu J., Liu F., Gao C. Volcanoes and Climate: Sizing up the Impact of the Recent Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai Volcanic Eruption from a Historical Perspective. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2022;39:1986–1993. doi: 10.1007/s00376-022-2034-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raible C.C., Brönnimann S., Auchmann R., Brohan P., Frölicher T.L., Graf H.F., Jones P., Luterbacher J., Muthers S., Neukom R., et al. Tambora 1815 as a test case for high impact volcanic eruptions: Earth system effects. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change. 2016;7:569–589. doi: 10.1002/wcc.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cahalan R.C., Dufek J. Explosive Submarine Eruptions: The Role of Condensable Gas Jets in Underwater Eruptions. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 2021;126 e2020JB020969. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ming L., Ke F., Hu X., Cui W., Zhao P. GNSS/AQUA Fusion Study of Atmospheric Response Characteristics and Interaction Mechanisms during the 2022 Tonga Volcanic Eruption. Atmosphere. 2023;14:1619. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kubota T., Saito T., Nishida K. Global fast-traveling tsunamis driven by atmospheric Lamb waves on the 2022 Tonga eruption. Science. 2022;377:91–94. doi: 10.1126/science.abo4364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matoza R.S., Fee D., Assink J.D., Iezzi A.M., Green D.N., Kim K., Toney L., Lecocq T., Krishnamoorthy S., Lalande J.M., et al. Atmospheric waves and global seismoacoustic observations of the January 2022 Hunga eruption, Tonga. Science. 2022;377:95–100. doi: 10.1126/science.abo7063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuen D.A., Scruggs M.A., Spera F.J., Zheng Y., Hu H., McNutt S.R., Thompson G., Mandli K., Keller B.R., Wei S.S., et al. Under the surface: Pressure-induced planetary-scale waves, volcanic lightning, and gaseous clouds caused by the submarine eruption of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano. Earthq. Res. Adv. 2022;2 doi: 10.1016/j.eqrea.2022.100134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The World Bank . 2022. The January 15, 2022 Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai Eruption and Tsunami, Tonga: Global Rapid Post Disaster Damage Estimation (Grade) Report; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Venckunas V. Airlines Forced to Cancel Dozens of Flights Due to Tonga Volcano Eruption. 2022. https://www.aerotime.aero/articles/29973-flights-cancelled-due-to-tonga-volcano-eruption.

- 22.Carn S.A., Krotkov N.A., Yang K., Krueger A.J. Measuring global volcanic degassing with the ozone monitoring instrument (OMI) Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2013;380:229–257. doi: 10.1144/SP380.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carn S.A., Yang K., Prata A.J., Krotkov N.A. Extending the long-term record of volcanic SO2 emissions with the Ozone Mapping and Profiler Suite nadir mapper. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015;42:925–932. doi: 10.1002/2014GL062437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carn S.A., Krueger A.J., Arellano S., Krotkov N.A., Yang K. Daily monitoring of Ecuadorian volcanic degassing from space. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2008;176:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2008.01.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torres O., Bhartia P.K., Jethva H., Ahn C. Impact of the ozone monitoring instrument row anomaly on the long-term record of aerosol products. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2018;11:2701–2715. doi: 10.5194/amt-11-2701-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin N., Wang Y., Zhang Y., Yang K. A large decline of tropospheric NO2 in China observed from space by SNPP OMPS. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;675:337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu M., Lin J., Kong H., Boersma K.F., Eskes H., Kanaya Y., He Q., Tian X., Qin K., Xie P., et al. A new TROPOMI product for tropospheric NO2 columns over East Asia with explicit aerosol corrections. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2020;13:4247–4259. doi: 10.5194/amt-2019-500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao M., Si F., Zhou H., Jiang Y., Ji C., Wang S., Zhan K., Liu W. Pre-Launch Radiometric Characterization of EMI-2 on the GaoFen-5 Series of Satellites. Remote Sens. 2021;13:2843. doi: 10.3390/rs13142843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Q., Qian Y., Luo Y., Cao L., Zhou H., Yang T., Si F., Liu W. Diffusion Height and Order of Sulfur Dioxide and Bromine Monoxide Plumes from the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai Volcanic Eruption. Remote Sens. 2023;15:1534. doi: 10.3390/rs15061534. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Theys N., De Smedt I., Clarisse L., Li C., van Gent J., Danckaert T., Wang T., Hendrick F., Stavrakou T., Bauduin S., et al. Sulfur dioxide vertical column DOAS retrievals from the Ozone Monitoring Instrument: Global observations and comparison to ground-based and satellite data. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2015;120:2470–2491. doi: 10.1002/2014JD022657.Received. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang K., Krotkov N.A., Krueger A.J., Carn S.A., Bhartia P.K., Levelt P.F. Retrieval of large volcanic SO2 columns from the Aura Ozone Monitoring Instrument: Comparison and limitations. J. Geophys. Res. 2007;112:D24S43. doi: 10.1029/2007JD008825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y., Li C., Krotkov N.A., Joiner J., Fioletov V., McLinden C. Continuation of long-term global SO2 pollution monitoring from OMI to OMPS. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2017;10:1495–1509. doi: 10.5194/amt-10-1495-2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Theys N., Fioletov V., Li C., De Smedt I., Lerot C., McLinden C., Krotkov N., Griffin D., Clarisse L., Hedelt P., et al. A sulfur dioxide Covariance-Based Retrieval Algorithm (COBRA): application to TROPOMI reveals new emission sources. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021;21:16727–16744. doi: 10.5194/acp-21-16727-2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carboni E., Mather T.A., Schmidt A., Grainger R.G., Pfeffer M.A., Ialongo I., Theys N. Satellite-derived sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions from the 2014-2015 Holuhraun eruption (Iceland) Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019;19:4851–4862. doi: 10.5194/acp-19-4851-2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prata A.J., Bernardo C. Retrieval of volcanic SO2 column abundance from Atmospheric Infrared Sounder data. J. Geophys. Res. 2007;112:1–17. doi: 10.1029/2006JD007955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao F., Liu C., Cai Z., Liu X., Bak J., Kim J., Hu Q., Xia C., Zhang C., Sun Y., et al. Ozone profile retrievals from TROPOMI: Implication for the variation of tropospheric ozone during the outbreak of COVID-19 in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;764 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xia C., Liu C., Cai Z., Duan X., Hu Q., Zhao F., Liu H., Ji X., Zhang C., Liu Y. Improved anthropogenic SO2 retrieval from high-spatial-resolution satellite and its application during the COVID-19 pandemic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021;55:11538–11548. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c01970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carn S.A., Krotkov N.A., Fisher B.L., Li C. Out of the blue: Volcanic SO2 emissions during the 2021–2022 eruptions of Hunga Tonga—Hunga Ha’apai (Tonga) Front. Earth Sci. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/feart.2022.976962. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robock A. Volcanic eruptions and climate. Rev. Geophys. 2000;38:191–219. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sellitto P., Siddans R., Belhadji R., Carboni E., Legras B., Podglajen A., Duchamp C., Kerridge B. Observing the SO2 and Sulphate Aerosol Plumes from the 2022 Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha ’ apai Eruption with IASI. ESS Open Archive. 2023 doi: 10.22541//essoar.169091894.48592907/v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Witze A. Why the Tongan eruption will go down in the history of volcanology. Nature. 2022;602:376–378. doi: 10.1038/d41586-022-00394-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Constantinescu R., Hopulele-Gligor A., Connor C.B., Bonadonna C., Connor L.J., Lindsay J.M., Charbonnier S., Volentik A.C.M. The radius of the umbrella cloud helps characterize large explosive volcanic eruptions. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021;2:3–8. doi: 10.1038/s43247-020-00078-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pandey P.C. Highlighting the role of earth observation Sentinel5P TROPOMI in monitoring volcanic eruptions: a report on Hunga Tonga, a Submarine Volcano. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022;13:912–923. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fioletov V., Mclinden C.A., Griffin D., Theys N., Loyola D.G., Hedelt P., Krotkov N.A., Li C. Anthropogenic and volcanic point source SO2 emissions derived from TROPOMI onboard Sentinel 5 Precursor : first results. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020;20:5591–5607. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nowlan C.R., Liu X., Chance K., Cai Z., Kurosu T.P., Lee C., Martin R.V. Retrievals of sulfur dioxide from the Global Ozone Monitoring Experiment 2 (GOME-2) using an optimal estimation approach: Algorithm and initial validation. J. Geophys. Res. 2011;116:D18301–D18320. doi: 10.1029/2011JD015808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xia C., Liu C., Cai Z., Zhao F., Su W., Zhang C., Liu Y. First sulfur dioxide observations from the environmental trace gases monitoring instrument (EMI) onboard the GeoFen-5 satellite. Sci. Bull. 2021;66:969–973. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2021.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bak J., Liu X., Kim J.H., Haffner D.P., Chance K., Yang K., Sun K. Characterization and correction of OMPS nadir mapper measurements for ozone profile retrievals. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2017;10:4373–4388. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spurr R.J. VLIDORT: A linearized pseudo-spherical vector discrete ordinate radiative transfer code for forward model and retrieval studies in multilayer multiple scattering media. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2006;102:316–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jqsrt.2006.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Theys N., Campion R., Clarisse L., Brenot H., Van Gent J., Dils B., Corradini S., Merucci L., Coheur P.F., Van Roozendael M., et al. Volcanic SO2 fluxes derived from satellite data: A survey using OMI, GOME-2, IASI and MODIS. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013;13:5945–5968. doi: 10.5194/acp-13-5945-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krueger A.J., Walter L.S., Bhartia P.K., Schnetzler C.C., Krotkov N.A., Sprod I., Bluth G.J.S. Volcanic sulfur dioxide measurements from the Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer (TOMS) Instruments. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1995;100:14057–14076. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

The source data is available as listed in the key resources table.

-

•

The code associated with the retrieval algorithm is available from the lead contact upon reasonable request.

-

•

Any additional information about the paper is available from the lead contact upon reasonable request.