Key Points

Question

How will Medicare’s new health equity adjustment in the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) program, which assigns additional points to hospitals with more dual-eligible patients for providing high-quality care, affect hospital performance and payment adjustments?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 2676 hospitals participating in the HVBP program, health equity adjustment reclassified 119 of 1206 hospitals (9.9%) from receiving penalties to receiving bonuses. Safety net and high-proportion Black hospitals were significantly more likely to experience increased payment adjustments, as were hospitals located in rural areas and the South. The largest net-positive changes in total payment adjustments were $29.0 million among safety net hospitals and $15.5 million among high-proportion Black hospitals.

Meaning

Medicare’s new health equity adjustment in the HVBP program will significantly reclassify hospital bonus and penalty status and redistribute program payments, with hospitals caring for minoritized populations and those with low income benefiting the most.

Abstract

Importance

Medicare’s Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) program will provide a health equity adjustment (HEA) to hospitals that have greater proportions of patients dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid and that offer high-quality care beginning in fiscal year 2026. However, which hospitals will benefit most from this policy change and to what extent are unknown.

Objective

To estimate potential changes in hospital performance after HEA and examine hospital patient mix, structural, and geographic characteristics associated with receipt of increased payments.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study analyzed all 2676 hospitals participating in the HVBP program in fiscal year 2021. Publicly available data on program performance and hospital characteristics were linked to Medicare claims data on all inpatient stays for dual-eligible beneficiaries at each hospital to calculate HEA points and HVBP payment adjustments.

Exposures

Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program HEA.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Reclassification of HVBP bonus or penalty status and changes in payment adjustments across hospital characteristics.

Results

Of 2676 hospitals participating in the HVBP program in fiscal year 2021, 1470 (54.9%) received bonuses and 1206 (45.1%) received penalties. After HEA, 102 hospitals (6.9%) were reclassified from bonus to penalty status, whereas 119 (9.9%) were reclassified from penalty to bonus status. At the hospital level, mean (SD) HVBP payment adjustments decreased by $4534 ($90 033) after HEA, ranging from a maximum reduction of $1 014 276 to a maximum increase of $1 523 765. At the aggregate level, net-positive changes in payment adjustments were largest among safety net hospitals ($28 971 708) and those caring for a higher proportion of Black patients ($15 468 445). The likelihood of experiencing increases in payment adjustments was significantly higher among safety net compared with non–safety net hospitals (574 of 683 [84.0%] vs 709 of 1993 [35.6%]; adjusted rate ratio [ARR], 2.04 [95% CI, 1.89-2.20]) and high-proportion Black hospitals compared with non–high-proportion Black hospitals (396 of 523 [75.7%] vs 887 of 2153 [41.2%]; ARR, 1.40 [95% CI, 1.29-1.51]). Rural hospitals (374 of 612 [61.1%] vs 909 of 2064 [44.0%]; ARR, 1.44 [95% CI, 1.30-1.58]), as well as those located in the South (598 of 1040 [57.5%] vs 192 of 439 [43.7%]; ARR, 1.25 [95% CI, 1.10-1.42]) and in Medicaid expansion states (801 of 1651 [48.5%] vs 482 of 1025 [47.0%]; ARR, 1.16 [95% CI, 1.06-1.28]), were also more likely to experience increased payment adjustments after HEA compared with their urban, Northeastern, and Medicaid nonexpansion state counterparts, respectively.

Conclusions and Relevance

Medicare’s implementation of HEA in the HVBP program will significantly reclassify hospital performance and redistribute program payments, with safety net and high-proportion Black hospitals benefiting most from this policy change. These findings suggest that HEA is an important strategy to ensure that value-based payment programs are more equitable.

This cross-sectional study discusses hospital performance after the incorporation of health equity adjustment into Medicare’s Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program.

Introduction

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) designated health equity as the first pillar of its 2023 strategic plan and is undertaking a comprehensive effort to advance equity through policy changes to its quality and value programs.1,2,3 Since 2011, the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) program has been one of Medicare’s cornerstone value-based initiatives. The HVBP program is mandatory and distributes financial bonuses or penalties to nearly 3000 US hospitals according to quality measures related to clinical outcomes, patient experience, safety, and efficiency.4

There has been substantial controversy surrounding the HVBP program since its enactment.5 Several studies have shown that the HVBP program disproportionately penalizes hospitals that care for disadvantaged and historically marginalized populations while providing greater financial bonuses to those that do not.6 For example, safety net hospitals,7,8 those serving more patients with low income,5,9 and those caring for a higher proportion of Black adults have all been more frequently penalized by the HVBP program.10 Because the program adjusts for medical risk factors but not social risk factors that are strongly associated with performance measures,11,12,13 many clinicians and policy experts have raised concerns that the HVBP program is widening disparities in care by unfairly redirecting resources away from disadvantaged hospitals.9,14

In response to these concerns, CMS recently finalized major policy changes to the HVBP program.15 Beginning in fiscal year (FY) 2026, hospitals with a greater proportion of patients dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid and that provide high-quality care will receive a health equity adjustment (HEA) that increases the scores used to determine bonuses and penalties under the program.16 Although the HVBP program is required to maintain budget neutrality, this policy change has the potential to significantly redistribute program payments across hospitals. However, which hospitals will benefit most from HEA and to what extent are currently unknown. Understanding the potential impact of this policy change is critically important because CMS and other payers are considering similar strategies to advance health equity under current and future value-based payment models.17

Therefore, we aimed to address 3 questions by simulating the impact of Medicare’s new HEA on HVBP performance, using FY 2021 data. First, does HEA change hospital performance rankings and bonus or penalty status under the HVBP program? Second, what is the magnitude of the financial impact of HEA both overall and across hospital characteristics (patient mix, structural, and geographic)? Third, which hospital characteristics are associated with receipt of increased bonuses or reduced penalties after HEA?

Methods

The HVBP Program and HEA

The HVBP program adjusts the amount that Medicare pays hospitals under the Inpatient Prospective Payment System by providing financial bonuses or penalties (henceforth referred to as “payment adjustments”) based on the quality of care delivered. The program evaluates 4 domains of quality: clinical outcomes, patient experience, safety, and efficiency. Each domain is scored, weighted, and summed into a total performance score, which is subsequently used to determine payment adjustments for each hospital. More details regarding the methodology for estimating HVBP payment adjustments are provided in eMethods 1 in Supplement 1.18 The HVBP program does not currently account for race and ethnicity, rurality, or other social risk factors.

In the Inpatient Prospective Payment System final rule issued by CMS,15 hospitals with a greater proportion of patients dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid will be rewarded for providing high-quality care. Hospitals will have the opportunity to earn up to 10 additional HEA points, which will be added to the total performance score (revised from a range of 0-100 to 0-110). The HEA is computed as the product of 2 values: the underserved multiplier and the measure performance scaler. The underserved multiplier is calculated by ranking hospitals according to the proportion of dual-eligible inpatient stays and applying a logistic exchange function to generate values between 0 and 1 (eMethods 2 and eFigures 1 and 2 in Supplement 1). The measure performance scaler is determined by allocating 0, 2, or 4 points to hospitals for being in the bottom, middle, or top performance tercile, respectively, of each HVBP domain and summing all points to generate values between 0 and 16. To illustrate, a hospital whose proportion of dual-eligible inpatient stays is 0.4 after the logistic function is applied (underserved multiplier = 0.4) and that performed at the top tercile in all 4 HVBP domains (measure performance scaler = 16) would earn 6.4 bonus points, whereas another hospital with an underserved multiplier of 0.8 performing at the same level would earn 10 points owing to the cap.

Data Sources

We used publicly available CMS files to identify all hospitals participating in the HVBP program in FY 2021, as well as their HVBP domain and total performance scores.19,20 The corresponding baseline and performance periods for FY 2021 are listed in eTable 1 in Supplement 1, which extend through 2019 across most measures. We chose this FY to avoid the extensive modifications applied to the HVBP program during the COVID-19 pandemic beginning in 2020. To determine the proportion of dual-eligible inpatient stays in FY 2021, we obtained data on all Medicare inpatient stays (fee-for-service and Medicare Advantage) and patients dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid at each hospital from the Medicare inpatient files and the Master Beneficiary Summary File.

The FY 2021 CMS Impact Files and 2020 American Hospital Association survey were used to determine hospital structural and geographic characteristics. Additionally, we extracted hospital-level case mix indices (average relative diagnosis related group weight of Medicare discharges) and total relative diagnosis related group weights by using the FY 2021 CMS case mix index file. Medicare inpatient and summary files were used to determine the proportion of Medicare hospitalizations for Black patients at each hospital. Financial information on base operating payment rates and area-level wage indices was acquired from FY 2021 Inpatient Prospective Payment System final rule data files. Data on state-level Medicaid expansion status were assembled by KFF.21

Outcomes

Our primary outcomes were changes in hospital performance (bonus or penalty status) and payment adjustments under the HVBP program after simulated HEA. We also examined hospital-level and total changes in HVBP payment adjustments across hospital patient mix characteristics (case mix index, safety net status,22 and high-proportion racial minority status10), as well as structural (size, ownership, and teaching status) and geographic characteristics (region, rurality, and state-level Medicaid expansion status). These variables are described in further detail in eMethods 3 in Supplement 1. Increased payment adjustments refer to larger bonuses, smaller penalties, or both, whereas decreased payment adjustments refer to smaller bonuses, larger penalties, or both.

Statistical Analysis

We use descriptive statistics to summarize HVBP performance scores, proportion of dual-eligible inpatient stays, and patient mix, structural, and geographic characteristics by hospital bonus or penalty status under the HVBP program in FY 2021.

We then assessed the extent to which the bonus or penalty status of hospitals would change after HEA is incorporated into the HVBP program. To do so, we first calculated the HEA points that would have been allocated to each hospital in FY 2021 according to their HVBP domain scores and proportion of dual-eligible inpatient stays. These HEA points were then used to calculate new hospital-level total performance scores. Next, we determined the proportion of hospitals that received a bonus or penalty under the HVBP program in FY 2021 that would be reclassified into a different bonus or penalty group after implementation of the HEA (eg, from receiving a bonus to receiving a penalty or vice versa). We also examined changes in average hospital-level payment adjustments, as well as total payment adjustments, after HEA across hospital patient mix, structural, and geographic characteristics. Statistical significance of changes in HVBP payment adjustments after HEA was assessed with Wilcoxon signed rank tests. To quantify the likelihood of receiving an increased payment adjustment after HEA across each hospital characteristic (eg, safety net status), we fit robust multivariable Poisson regression models adjusting for all other hospital characteristics.

We conducted several additional analyses in response to a CMS request for information regarding the potential impact of alternative approaches to calculate HEA points.15 For each alternative approach, we evaluated the proportion of hospitals reclassified to a different bonus or penalty group and total changes in HVBP payment adjustments across hospital characteristics after HEA. First, we calculated HEA points without a 10-point cap. Second, to calculate the measure performance scaler, we allocated 0, 0, or 4 points to hospitals for being in the bottom, middle, or top performance tercile, respectively, of each HVBP domain. Third, we determined the underserved multiplier with a linear exchange function by rescaling hospital dual-eligible rank between 0 and 1. Fourth, we calculated the underserved multiplier with actual scoring by directly using the proportion of dual-eligible inpatient stays at each hospital.

All analyses were conducted with R version 4.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), and a 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Institutional review board approval was obtained from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, with a waiver of informed consent owing to the deidentified nature of the data.

Results

Hospital Characteristics

Of 2676 hospitals participating in the HVBP program in FY 2021, 1470 (54.9%) received bonuses and 1206 (45.1%) received penalties (Table 1). The mean (SD) percentage of dual-eligible inpatient stays was 26.3% (14.0%) among hospitals receiving bonuses and 29.5% (13.1%) among those receiving penalties. The distribution of dual-eligible inpatient stays across hospitals is shown in eFigure 3 in Supplement 1 and the proportion of such stays across hospital characteristics is presented in eTable 2 in Supplement 1. Mean (SD) total performance scores were 41.9 (9.2) and 24.2 (4.8) among hospitals receiving bonuses and penalties, respectively.

Table 1. Characteristics and Performance of Hospitals Participating in the HVBP Program by Bonus or Penalty Status Before Health Equity Adjustment.

| Characteristics | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Hospitals receiving penalties | Hospitals receiving bonuses | |

| Total No. of hospitals | 1206/2676 (45.1) | 1470/2676 (54.9) |

| Dual-eligible inpatient stays, mean (SD), %a | 29.5 (13.1) | 26.3 (14.0) |

| Total performance scores, mean (SD)b | 24.2 (4.8) | 41.9 (9.2) |

| Weighted domain scores, mean (SD)c | ||

| Clinical outcomes | 9.6 (3.9) | 13.0 (4.8) |

| Patient/caregiver experience of care | 6.3 (3.3) | 10.8 (6.1) |

| Safety domain | 7.6 (4.0) | 12.4 (5.4) |

| Efficiency and cost reduction | 1.8 (3.1) | 9.1 (8.7) |

| Patient mix characteristics | ||

| Case mix indexd | ||

| Quintiles 2-5 | 946/2190 (43.2) | 1244/2190 (56.8) |

| Quintile 1 (most complex) | 260/486 (53.5) | 226/486 (46.5) |

| Safety net status | ||

| Non–safety net hospital | 815/1993 (40.9) | 1178/1993 (59.1) |

| Safety net hospitale | 391/683 (57.2) | 292/683 (42.8) |

| Proportion minority | ||

| Non–high-proportion Black hospital | 906/2153 (42.1) | 1247/2153 (57.9) |

| High-proportion Black hospitalf | 300/523 (57.4) | 223/523 (42.6) |

| Structural characteristics | ||

| Size (No. of beds) | ||

| Small (<100) | 204/783 (26.1) | 579/783 (73.9) |

| Medium (100-399) | 768/1538 (49.9) | 770/1538 (50.1) |

| Large (≥400) | 234/355 (65.9) | 121/355 (34.1) |

| Ownership | ||

| Private, for profit | 248/492 (50.4) | 244/492 (49.6) |

| Private, nonprofit | 769/1829 (42.0) | 1060/1829 (58.0) |

| Public | 173/331 (52.3) | 158/331 (47.7) |

| Teaching status | ||

| Nonteaching | 502/1322 (38.0) | 820/1322 (62.0) |

| Teachingg | 704/1354 (52.0) | 650/1354 (48.0) |

| Geographic characteristics | ||

| Region | ||

| Northeast | 228/439 (51.9) | 211/439 (48.1) |

| Midwest | 237/648 (36.6) | 411/648 (63.4) |

| South | 531/1040 (51.1) | 509/1040 (48.9) |

| West | 210/549 (38.3) | 339/549 (61.7) |

| Rurality | ||

| Urban | 999/2064 (48.4) | 1065/2064 (51.6) |

| Rural | 207/612 (33.8) | 405/612 (66.2) |

| Medicaid expansion status | ||

| Nonexpansion state | 482/1025 (47.0) | 543/1025 (53.0) |

| Expansion stateh | 724/1651 (43.9) | 927/1651 (56.1) |

Abbreviation: HVBP, Hospital Value-Based Purchasing.

Defined as the proportion of inpatient stays for patients with dual-eligible status out of the total number of inpatient Medicare (fee-for-service and Advantage) stays in 2019. A stay was defined as dual eligible if it was for a patient with Medicare and full Medicaid benefits for the month the patient was discharged. If the patient died in the month of discharge, dual-eligible status was determined by using the previous month. Data on inpatient stays were obtained from Medicare inpatient files. Data on dual-eligible status were drawn from the Master Beneficiary Summary File.

The score ranges from 0 to 110.

Higher scores indicate better performance on measures.

A measure of the average relative diagnosis related group weight of Medicare discharges.

Defined as hospitals in the top quartile of the Disproportionate Share Hospital index nationally.

Defined as hospitals in the top quintile of proportion of Medicare (fee-for-service and Advantage) hospitalizations for Black patients in 2019.

Defined as hospitals with medical school affiliations reported to the American Medical Association or members of the Council of Teaching Hospitals and Health Systems.

Adopted and implemented Medicaid expansion by 2019.

Hospital characteristics differed by HVBP bonus vs penalty status. Safety net hospitals (391 [57.2%] vs 292 [42.8%] of 683), high-proportion Black hospitals (300 [57.4%] vs 223 [42.6%] of 523), and hospitals in the top (most medically complex) case mix index quintile (260 [53.5%] vs 226 [46.5%] of 486) were more likely to receive penalties than bonuses. In addition, large hospitals (234 [65.9%] vs 121 [34.1%] of 355), public hospitals (173 [52.3%] vs 158 [47.7%] of 331), and teaching hospitals (704 [52.0%] vs 650 [48.0%] of 1354) were also more often in the penalized group, as were hospitals located in the South (531 [51.1%] vs 509 [48.9%] of 1040) and Northeast (228 [51.9%] vs 211 [48.1%] of 439).

Reclassification of HVBP Bonus or Penalty Status

The distributions of HVBP bonus or penalty status before and after HEA are shown in eFigure 4 in Supplement 1. Of 1470 hospitals that received bonuses before HEA, 102 (6.9%) were reclassified to instead receive penalties after HEA. Of 1206 hospitals that received penalties before HEA, 119 (9.9%) were reclassified to instead receive bonuses after HEA. Results of HVBP performance reclassification based on total performance score quintiles appear in eFigure 5 in Supplement 1.

Changes in HVBP Payment Adjustments

Before HEA, the mean hospital-level HVBP bonus and penalty were $155 250 (range, $90 to $5 215 069) and $196 996 (range, $163 to $2 125 735), respectively. After HEA, the mean hospital-level HVBP bonus and penalty were $151 390 (range, $18 to $6 547 164) and $207 410 (range, $20 to $2 140 874). Accordingly, average hospital-level payment adjustments decreased by $4534 after HEA, ranging between a decrease of $1 014 276 to an increase of $1 523 765. Distributions of HVBP payment adjustments before and after HEA are shown in eFigure 6 in Supplement 1.

As expected, HVBP payment adjustments increased across increasing proportions of dual-eligible inpatient stays after HEA (eFigures 7 and 8 in Supplement 1). Changes in hospital-level HVBP payment adjustments also varied significantly across hospital characteristics (Table 2). The largest mean (SD) increases in HVBP payment adjustments were observed among safety net ($42 418 [$73 233]) and high-proportion Black hospitals ($29 576 [$87 126]), with corresponding reductions among non–safety net ($20 625 [$89 634]) and non–high-proportion Black hospitals ($12 820 [$88 787]). Public hospitals ($15 698 [$72 559]), rural hospitals ($6503 [$33 946]), and Southern hospitals ($4436 [$93 577]) also experienced increases in mean (SD) payment adjustments, whereas payment adjustments decreased among nonprofit ($10 942 [$99 098]), urban ($7807 [$100 610]), Northeastern ($12 234 [$82 405]), and Midwestern hospitals ($26 016 [$92 834]). Significant reductions in mean (SD) payment adjustments were also experienced by teaching hospitals ($7984 [$116 704]) and those in the top case mix index quintile ($13 843 [$163 698]).

Table 2. Mean Change in HVBP Payment Adjustments After Health Equity Adjustment by Hospital Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Mean (SD), $ | P valuea | Total change in payment adjustment, $ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital-level payment adjustmentb | Change in hospital-level payment adjustmentc | ||||

| Before HEA | After HEA | ||||

| Overall (n = 2676)d | −3498 (320 292) | −8032 (323 262) | −4534 (90 033) | <.001 | −12 133 880 |

| Patient mix characteristics | |||||

| Case mix index | |||||

| Quintiles 2-5 (n = 2190) | 4240 (214 679) | 1772 (215 944) | −2469 (62 808) | .16 | −5 406 318 |

| Quintile 1 (most complex) (n = 486) | −38 366 (596 923) | −52 208 (602 910) | −13 843 (163 698) | <.001 | −6 727 563 |

| Safety net status | |||||

| Non–safety net hospital (n = 1993) | 15 306 (339 762) | −5319 (338 919) | −20 625 (89 634) | <.001 | −41 105 588 |

| Safety net hospital (n = 683) | −58 366 (247 291) | −15 947 (272 555) | 42 418 (73 233) | <.001 | 28 971 708 |

| Proportion minority | |||||

| Non–high-proportion Black hospital (n = 2153) | 11 186 (325 970) | −1634 (327 089) | −12 820 (88 787) | <.001 | −27 602 325 |

| High-proportion Black hospital (n = 523) | −63 946 (288 279) | −34 370 (305 899) | 29 576 (87 126) | <.001 | 15 468 445 |

| Structural characteristics | |||||

| Size (No. of beds) | |||||

| Small (<100) (n = 783) | 50 236 (87 817) | 46 937 (82 146) | −3298 (23 451) | <.001 | −2 582 616 |

| Medium (100-399) (n = 1538) | 2314 (247 685) | −1802 (245 235) | −4116 (70 685) | .06 | −6 331 127 |

| Large (≥400) (n = 355) | −147 192 (681 589) | −156 263 (696 228) | −9071 (195 754) | .047 | −3 220 138 |

| Ownership | |||||

| Private, for profit (n = 492) | −24 885 (231 406) | −19 412 (242 365) | 5472 (59 136) | .06 | 2 692 430 |

| Private, nonprofit (n = 1829) | 11 080 (351 914) | 138 (352 472) | −10 942 (99 098) | <.001 | −20 013 225 |

| Public (n = 331) | −50 278 (246 712) | −34 579 (262 618) | 15 698 (72 559) | <.001 | 5 196 138 |

| Teaching status | |||||

| Nonteaching (n = 1322) | 21 752 (158 442) | 20 751 (164 463) | −1001 (49 396) | .22 | −1 323 292 |

| Teaching (n = 1354) | −28 151 (420 881) | −36 135 (422 604) | −7984 (116 704) | <.001 | −10 810 588 |

| Geographic characteristics | |||||

| Region | |||||

| Northeast (n = 439) | −17 502 (282 554) | −29 736 (275 391) | −12 234 (82 405) | <.001 | −5 370 895 |

| Midwest (n = 648) | 43 267 (355 918) | 17 251 (315 832) | −26 016 (92 834) | <.001 | −16 858 606 |

| South (n = 1040) | −53 619 (338 510) | −49 183 (369 121) | 4436 (93 577) | .02 | 4 613 446 |

| West (n = 549) | 47 449 (244 995) | 57 435 (254 445) | 9986 (80 038) | .07 | 5 482 175 |

| Rurality | |||||

| Urban (n = 2064) | −12 992 (356 718) | −20 799 (359 032) | −7807 (100 610) | <.001 | −16 113 837 |

| Rural (n = 612) | 28 522 (134 751) | 35 025 (140 917) | 6503 (33 946) | <.001 | 3 979 957 |

| Medicaid expansion status | |||||

| Nonexpansion state (n = 1025) | −37 097 (329 000) | −41 254 (356 776) | −4157 (88 131) | .002 | −4 261 123 |

| Expansion state (n = 1651) | 17 362 (313 055) | 12 593 (298 842) | −4768 (91 220) | .01 | −7 872 758 |

Abbreviations: HEA, health equity adjustment; HVBP, Hospital Value-Based Purchasing.

Comparisons were conducted with paired Wilcoxon signed rank tests.

Positive values represent bonuses and negative values represent penalties.

Positive values represent increased payment adjustments and negative values represent decreased payment adjustments.

To illustrate, mean (SD) hospital-level payment adjustments across all hospitals before and after HEA were −$3498 ($320 292) and −$8032 ($323 262), respectively, which corresponded to a mean (SD) change in hospital-level payment adjustment across all hospitals of −$4534 (−$90 033) and a total change in payment adjustment across all hospitals of −$12 133 880. The total change in payment adjustment across all hospitals was not neutral owing to shifts in the distribution of HVBP payment adjustment factors after HEA.

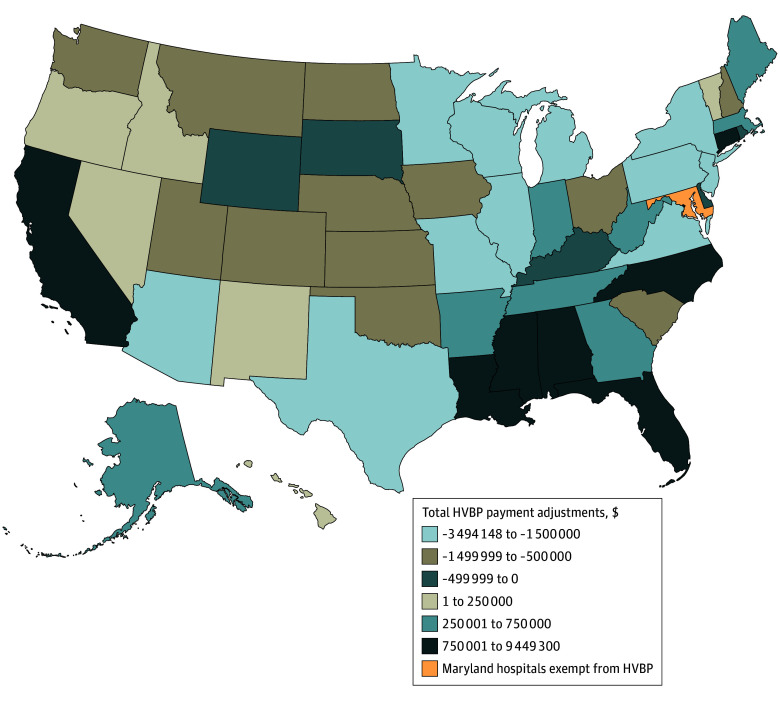

At the aggregate level, safety net ($28 971 708) and high-proportion Black hospitals ($15 468 445) had the largest increases in total HVBP payment adjustments after HEA, followed by Western ($5 482 175) and public hospitals ($5 196 138). Non–safety net hospitals ($41 105 588), non–high-proportion Black hospitals ($27 602 325), nonprofit hospitals ($20 013 225), and Midwestern hospitals ($16 858 606) experienced the largest reductions in total HVBP payment adjustments. The variation in total HVBP payment adjustment changes across states is shown in the Figure.

Figure. Geographic Distribution of Total Changes in Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) Payment Adjustments After Health Equity Adjustment.

California and Louisiana experienced the largest increases in total HVBP payment adjustments, at $9 449 300 and $2 377 184, respectively. Pennsylvania and Minnesota experienced the largest decreases in total HVBP payment adjustments, at $3 494 148 and $3 479 801, respectively.

Hospital Characteristics Associated With Increased HVBP Payment Adjustments

Of all hospitals participating in the HVBP program, 1283 (47.9%) received increased payment adjustments after HEA (Table 3). The likelihood of receiving increased HVBP payment adjustments after HEA was significantly higher among safety net hospitals (574 of 683 [84.0%] vs 709 of 1993 [35.6%]; adjusted rate ratio [ARR], 2.04 [95% CI, 1.89-2.20]) and high-proportion Black hospitals (396 of 523 [75.7%] vs 887 of 2153 [41.2%]; ARR, 1.40 [95% CI, 1.29-1.51]) vs their non–safety net and non–high-proportion Black counterparts. Medium-sized hospitals (755 of 1538 [49.1%] vs 373 of 783 [47.6%]; ARR, 1.12 [95% CI, 1.02-1.24]) were also more likely than small hospitals to receive increased payment adjustments, whereas nonprofit hospitals were less likely to do so than their for-profit counterparts (775 of 1829 [42.4%] vs 272 of 492 [55.3%]; ARR, 0.91 [95% CI, 0.83-0.99]). A higher likelihood was observed among hospitals located in the South (598 of 1040 [57.5%] vs 192 of 439 [43.7%]; ARR, 1.25 [95% CI, 1.10-1.42]) relative to those in the Northeast, whereas a lower likelihood was observed among hospitals in the Midwest (211 of 648 [32.6%] vs 192 of 439 [43.7%]; ARR, 0.82 [95% CI, 0.72-0.95]). Rural hospitals (374 of 612 [61.1%] vs 909 of 2064 [44.0%]; ARR, 1.44 [95% CI, 1.30-1.58]) and those located in Medicaid expansion states (801 of 1651 [48.5%] vs 482 of 1025 [47.0%]; ARR, 1.16 [95% CI, 1.06-1.28]) were also more likely to receive increased payment adjustments. State-level variation in proportion of hospitals receiving increased HVBP payment adjustments is shown in eFigure 9 in Supplement 1.

Table 3. Rates of Receiving an Increased Bonus or Reduced Penalty After Health Equity Adjustment by Hospital Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Hospitals receiving increased bonus or reduced penalty, No./total No. (%) | Rate ratio (95% CI)a | Adjusted rate ratio (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 1283/2676 (47.9) | NA | NA |

| Patient mix characteristics | |||

| Case mix index | |||

| Quintiles 2-5 | 1101/2190 (50.3) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Quintile 1 (highest) | 182/486 (37.4) | 0.74 (0.66-0.84) | 0.76 (0.67-0.86) |

| Safety net status | |||

| Non–safety net hospital | 709/1993 (35.6) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Safety net hospital | 574/683 (84.0) | 2.36 (2.21-2.53) | 2.04 (1.89-2.20) |

| Proportion minority | |||

| Non–high-proportion Black hospital | 887/2153 (41.2) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| High-proportion Black hospital | 396/523 (75.7) | 1.84 (1.71-1.97) | 1.40 (1.29-1.51) |

| Structural characteristics | |||

| Size (No. of beds) | |||

| Small (<100) | 373/783 (47.6) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Medium (100-399) | 755/1538 (49.1) | 1.03 (0.94-1.13) | 1.12 (1.02-1.24) |

| Large (≥400) | 155/355 (43.7) | 0.92 (0.80-1.05) | 1.08 (0.93-1.26) |

| Ownership | |||

| Private, for profit | 272/492 (55.3) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Private, nonprofit | 775/1829 (42.4) | 0.77 (0.70-0.84) | 0.91 (0.83-0.99) |

| Public | 225/331 (68.0) | 1.23 (1.10-1.37) | 1.07 (0.96-1.19) |

| Teaching status | |||

| Nonteaching | 662/1322 (50.1) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Teaching | 621/1354 (45.9) | 0.92 (0.85-0.99) | 0.97 (0.90-1.05) |

| Geographic characteristics | |||

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 192/439 (43.7) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Midwest | 211/648 (32.6) | 0.74 (0.64-0.87) | 0.82 (0.72-0.95) |

| South | 598/1040 (57.5) | 1.32 (1.17-1.48) | 1.25 (1.10-1.42) |

| West | 282/549 (51.4) | 1.17 (1.03-1.34) | 1.07 (0.94-1.21) |

| Location | |||

| Urban | 909/2064 (44.0) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Rural | 374/612 (61.1) | 1.39 (1.28-1.50) | 1.44 (1.30-1.58) |

| Medicaid expansion status | |||

| Nonexpansion state | 482/1025 (47.0) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Expansion state | 801/1651 (48.5) | 1.03 (0.95-1.12) | 1.16 (1.06-1.28) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Rate ratios are estimated from robust Poisson regression models.

Adjusted rate ratios are estimated from robust Poisson regression models adjusting for case mix index, safety net status, high-proportion racial minority status, size, ownership, teaching status, region, location, and Medicaid expansion status.

Additional Analyses

The impact of alternative approaches to calculate HEA points on HVBP bonus or penalty status and changes in payment adjustments are presented in eFigures 10 through 13 and eTables 3 through 6 in Supplement 1, respectively. Using the point allocation approach (0, 0, or 4) for the measure performance scaler or calculating the underserved multiplier with actual scoring substantially decreased the number of hospitals reclassified from penalty to bonus status compared with the current CMS methodology. These approaches also resulted in reduced total HVBP payment adjustments across nearly all hospital characteristics. Minimal changes in hospital performance or payment adjustments were observed after removing the 10-point cap or calculating the underserved multiplier with linear scoring.

Discussion

In this national study of US hospitals, we found that incorporating Medicare’s HEA into the HVBP program will significantly redistribute program payments across hospitals, ranging from hospital-level reductions of just over $1 million to increases of greater than $1.5 million. Our findings indicate that the degree of change in HVBP performance and payment adjustments will vary markedly across hospital patient mix, structural, and geographic characteristics. Safety net and high-proportion Black hospitals that are currently disproportionately penalized by the HVBP program are projected to experience the largest penalty reductions, with collective net-positive changes in payment adjustments of $29.0 million and $15.5 million, respectively. In addition, rural and Southern hospitals will be more likely to benefit and receive net-positive changes in payment adjustments after HEA is implemented.

The HVBP program and other value-based initiatives have been increasingly criticized for unfairly penalizing resource-constrained hospitals serving disadvantaged populations.9,23 These disproportionate penalties may exacerbate the financial instability of safety net and rural hospitals, which are already operating on thin margins and closing at alarming rates.24,25 Clinicians, health system leaders, and policy experts have voiced concerns that current quality measures fail to adequately account for patient social risk factors.14,23,26,27,28,29 However, directly adjusting quality measures for social risk is controversial because it could be perceived as lowering the standard of care or obfuscating poorer outcomes among underserved patients.30,31 CMS has thoughtfully designed HEA specifications to simultaneously address concerns related to both health equity and appropriate performance measurement.17 First, the forthcoming HVBP policy change adjusts payments rather than the quality measures themselves, thereby avoiding shifts in performance expectations or inaccurate quality measurement. Second, the HEA successfully lowers penalties for disadvantaged hospitals through the underserved multiplier while incentivizing the provision of high-quality care through the measure performance scaler. Our additional analyses demonstrate that the finalized policy change, compared with alternative approaches, maximizes the benefit for disadvantaged hospitals and optimizes total payment adjustments across all hospitals.

Although our findings demonstrate that HEA will increase aggregate HVBP payment adjustments for hospitals caring for underserved populations, it remains unclear whether this policy change will have a meaningful effect on hospital finances, operations, and quality at the individual hospital level.32,33 For example, average payment adjustments were projected to increase by only approximately $42 000 among safety net hospitals and $6500 among rural hospitals. Nevertheless, many hospitals are expected to experience substantial net-positive changes in payment adjustments of nearly $250 000. Future studies should evaluate the downstream impacts of payment redistribution on hospitals and their patients, such as hospital closures, racial and ethnic disparities in quality of care, and investments in initiatives that aim to address health inequities.

The use of dual-eligible status in the HVBP program builds on other recent CMS policy changes and fosters alignment across its programs. In the 21st Century Cures Act, Congress directed CMS to assess hospital performance relative to other hospitals with similar proportions of dual-eligible patients in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program rather than comparing all participating hospitals to one another.34 This decision was informed by a 2016 Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation report to Congress, which demonstrated that dual-eligible status was the strongest predictor of poor outcomes across quality measures, a finding that persisted even when beneficiaries receiving care at the same hospital were compared.35,36 However, this approach in both programs can result in significant state-level heterogeneity in the effects of HEA owing to variations in Medicaid policies. Hospitals located in states with less generous Medicaid coverage, ineffective enrollment strategies, and burdensome recertification processes will likely benefit less from HEA based on dual-eligible status,37,38,39 which may explain why we found that hospitals located in Medicaid expansion states were more likely than those in Medicaid nonexpansion states to experience increased payment adjustments, consistent with analyses of the recent Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program policy change.34

The findings of this study suggest that HEA is an important first step toward mitigating the regressive nature of value-based payment programs. However, the HVBP program is still built on and constrained by the traditional fee-for-service architecture; the movement toward population-based models may enable more innovative and progressive approaches to advance health equity.23 For example, payment models could provide increased up-front payments to safety net and rural hospitals that would allow these institutions to invest in equity-centered infrastructure and care delivery innovations.40,41 Another option is for value-based payment programs to incentivize the measurement and reduction of health inequities as part of performance assessment.42 The recently announced CMS States Advancing All-Payer Health Equity Approaches and Development model is one such example and will enable states to implement hospital global budgets with social risk adjustment and bonuses for hospitals that improve performance on disparity-focused measures.43

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, we used FY 2021 data to project the impact of HEA under the HVBP program. The true impact will depend on actual hospital performance and proportion of dual-eligible inpatient stays in FY 2026. Nonetheless, our analysis used the most recent performance data available before the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in the suspension of the HVBP program and other value-based payment programs.44 Second, our estimation of hospital-level HVBP payment adjustments relied on standardized operating amounts for hospitals designated as meaningful electronic health record users. However, national data have shown that almost all acute care hospitals have achieved meaningful electronic health record use, with even higher rates among hospitals participating in the HVBP program.45,46 Third, high-proportion Black hospitals were identified by using Medicare hospitalizations. However, recent evidence suggests that the share of Medicare discharges for Black patients is nearly identical to their share of all hospital discharges.10,47 Fourth, although there is no standard method for defining safety net hospitals, we followed an approach that has been most consistently used in past studies.48,49,50

Conclusions

The incorporation of HEA in the HVBP program will significantly reclassify hospital bonus or penalty status and redistribute program payments. Hospitals that are currently disproportionately penalized, such as safety net and high-proportion Black hospitals, will benefit most from this policy change. These findings suggest that HEA will help reduce the regressive nature of the HVBP program and should be considered in other value-based payment programs.

eMethods 1. Methodology for Estimating HVBP Payment Adjustments

eMethods 2. Logistic Exchange Function to Calculate the Underserved Multiplier

eMethods 3. Detailed Description of Study Covariates

eTable 1. Fiscal Year 2021 Performance Period of HVBP Performance Domain Measures

eTable 2. Proportion of Dual-Eligible Inpatient Stays by Hospital Characteristics

eTable 3. Total Change in HVBP Payment Adjustments After Health Equity Adjustment by Hospital Characteristics Without 10-Point Cap

eTable 4. Total Change in HVBP Payment Adjustments After Health Equity Adjustment by Hospital Characteristics With (0,0,4) Performance Scaler

eTable 5. Total Change in HVBP Payment Adjustments After Health Equity Adjustment by Hospital Characteristics With Linear Scoring to Calculate the Underserved Multiplier

eTable 6. Total Change in HVBP Payment Adjustments After Health Equity Adjustment by Hospital Characteristics With Actual Scoring to Calculate the Underserved Multiplier

eFigure 1. Relationship Between Dual-Eligible Inpatient Stay Proportion and the Underserved Multiplier

eFigure 2. Relationship Between Rank of Dual-Eligible Inpatient Stay Proportion and the Underserved Multiplier

eFigure 3. Distribution of Dual-Eligible Inpatient Stay Proportion Across Hospitals

eFigure 4. Reclassification of Hospital Bonus/Penalty Status in the HVBP After Health Equity Adjustment

eFigure 5. Reclassification of Hospital Performance in the HVBP After Health Equity Adjustment

eFigure 6. Distribution of Hospital-Level HVBP Payment Adjustments Before and After Health Equity Adjustment

eFigure 7. Changes in Total HVBP Payment Adjustments by Quintile of Dual-Eligible Inpatient Stays

eFigure 8. Changes in Hospital-Level HVBP Payment Adjustments by Quintile of Dual-Eligible Inpatient Stays

eFigure 9. Geographical Distribution of Proportion of Hospitals Receiving Increased Payment Adjustments After Health Equity Adjustment

eFigure 10. Reclassification of Hospital Bonus/Penalty Status After Health Equity Adjustment Without 10-Point Cap

eFigure 11. Reclassification of Hospital Bonus/Penalty Status After Health Equity Adjustment With (0,0,4) Performance Scaler

eFigure 12. Reclassification of Hospital Bonus/Penalty Status After Health Equity Adjustment With Linear Scoring to Calculate the Underserved Multiplier

eFigure 13. Reclassification of Hospital Bonus/Penalty Status After Health Equity Adjustment With Actual Scoring to Calculate the Underserved Multiplier

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . 2023 CMS strategic plan. Updated January 23, 2024. Accessed September 15, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/about-cms/what-we-do/cms-strategic-plan

- 2.Seshamani M, Jacobs DB. Leveraging Medicare to advance health equity. JAMA. 2022;327(18):1757-1758. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.6613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs DB, Schreiber M, Seshamani M, Tsai D, Fowler E, Fleisher LA. Aligning quality measures across CMS—the universal foundation. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(9):776-779. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2215539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chee TT, Ryan AM, Wasfy JH, Borden WB. Current state of value-based purchasing programs. Circulation. 2016;133(22):2197-2205. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.010268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan AM. Will value-based purchasing increase disparities in care? N Engl J Med. 2013;369(26):2472-2474. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1312654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim H, Mahmood A, Hammarlund NE, Chang CF. Hospital value-based payment programs and disparity in the United States: a review of current evidence and future perspectives. Front Public Health. 2022;10:882715. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.882715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilman M, Adams EK, Hockenberry JM, Wilson IB, Milstein AS, Becker ER. California safety-net hospitals likely to be penalized by ACA value, readmission, and meaningful-use programs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(8):1314-1322. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Figueroa JF, Wang DE, Jha AK. Characteristics of hospitals receiving the largest penalties by US pay-for-performance programmes. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(11):898-900. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-005040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joynt Maddox KE. Financial incentives and vulnerable populations—will alternative payment models help or hurt? N Engl J Med. 2018;378(11):977-979. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1715455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aggarwal R, Hammond JG, Joynt Maddox KE, Yeh RW, Wadhera RK. Association between the proportion of Black patients cared for at hospitals and financial penalties under value-based payment programs. JAMA. 2021;325(12):1219-1221. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bundy JD, Mills KT, He H, et al. Social determinants of health and premature death among adults in the USA from 1999 to 2018: a national cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2023;8(6):e422-e431. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00081-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston KJ, Joynt Maddox KE. The role of social, cognitive, and functional risk factors in Medicare spending for dual and nondual enrollees. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(4):569-576. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wadhera RK, Wang Y, Figueroa JF, Dominici F, Yeh RW, Joynt Maddox KE. Mortality and hospitalizations for dually enrolled and nondually enrolled Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years or older, 2004 to 2017. JAMA. 2020;323(10):961-969. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaffery JB, Safran DG. Addressing social risk factors in value-based payment: adjusting payment not performance to optimize outcomes and fairness. Health Affairs Forefront. Published April 19, 2021. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/addressing-social-risk-factors-value-based-payment-adjusting-payment-not-performance

- 15.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . FY 2024 Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) and Long-Term Care Hospital Prospective Payment System (LTCH PPS) final rule—CMS-1785-F and CMS-1788-F fact sheet. Published August 1, 2023. Accessed September 15, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/fy-2024-hospital-inpatient-prospective-payment-system-ipps-and-long-term-care-hospital-prospective-0

- 16.Navathe AS, Liao JM. Advancing equity versus quality in population-based models: lessons from the new proposed rule. Health Affairs Forefront. Published July 10, 2023. Accessed September 15, 2023. https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/advancing-equity-versus-quality-population-based-models-lessons-new-proposed-rule

- 17.Jacobs DB, Schreiber M, Seshamani M. The CMS strategy to promote equity in quality and value programs. JAMA Health Forum. 2023;4(10):e233557. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2023.3557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bazzoli GJ, Thompson MP, Waters TM. Medicare payment penalties and safety net hospital profitability: minimal impact on these vulnerable hospitals. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(5):3495-3506. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP)—total performance score. Published 2023. Updated January 8, 2024. Accessed September 22, 2023. https://data.cms.gov/provider-data/dataset/ypbt-wvdk

- 20.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . FY 2021 IPPS final rule home page. Published 2023. Accessed September 22, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/prospective-payment-systems/acute-inpatient-pps/fy-2021-ipps-final-rule-home-page

- 21.Antonisse L, Rudowitz R. An overview of state approaches to adopting the Medicaid expansion. Kaiser Family Foundation. Published February 27, 2019. Accessed September 16, 2023. https://www.kff.org/report-section/an-overview-of-state-approaches-to-adopting-the-medicaid-expansion-issue-brief/

- 22.Liu M, Figueroa JF, Song Y, Wadhera RK. Mortality and postdischarge acute care utilization for cardiovascular conditions at safety-net versus non–safety-net hospitals. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(1):83-87. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gondi S, Joynt Maddox K, Wadhera RK. “REACHing” for equity—moving from regressive toward progressive value-based payment. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(2):97-99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2204749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaffney LK, Michelson KA. Analysis of hospital operating margins and provision of safety net services. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(4):e238785. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.8785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaufman BG, Thomas SR, Randolph RK, et al. The rising rate of rural hospital closures. J Rural Health. 2016;32(1):35-43. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buntin MB, Ayanian JZ. Social risk factors and equity in Medicare payment. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(6):507-510. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1700081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wadhera RK. Value-based payment for cardiovascular care: getting to the heart of the matter. Circulation. 2023;148(14):1084-1086. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.065661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McWilliams JM. Pay for performance: when slogans overtake science in health policy. JAMA. 2022;328(21):2114-2116. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.20945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wadhera RK, Yeh RW, Joynt Maddox KE. The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program—time for a reboot. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2289-2291. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1901225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nerenz DR, Austin JM, Deutscher D, et al. Adjusting quality measures for social risk factors can promote equity in health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(4):637-644. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agrawal SK, Shrank WH. Clinical and social risk adjustment—reconsidering distinctions. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(17):1581-1583. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1913993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jha AK. Value-based purchasing: time for reboot or time to move on? JAMA. 2017;317(11):1107-1108. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilman M, Hockenberry JM, Adams EK, Milstein AS, Wilson IB, Becker ER. The financial effect of value-based purchasing and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program on safety-net hospitals in 2014: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6):427-436. doi: 10.7326/M14-2813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joynt Maddox KE, Reidhead M, Qi AC, Nerenz DR. Association of stratification by dual enrollment status with financial penalties in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(6):769-776. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts ET, Zaslavsky AM, Barnett ML, Landon BE, Ding L, McWilliams JM. Assessment of the effect of adjustment for patient characteristics on hospital readmission rates: implications for pay for performance. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11):1498-1507. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Report to Congress: social risk factors and performance under Medicare’s value-based purchasing programs. Published December 20, 2016. Accessed December 28, 2023. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/report-congress-social-risk-factors-performance-under-medicares-value-based-purchasing-programs

- 37.Shashikumar SA, Waken RJ, Aggarwal R, Wadhera RK, Joynt Maddox KE. Three-year impact of stratification in the Medicare Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(3):375-382. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ku L, Platt I. Duration and continuity of Medicaid enrollment before the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(12):e224732. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.4732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaiser Family Foundation . Medicaid eligibility through the aged, blind, disabled pathway. Published 2022. Accessed September 17, 2023. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-eligibility-through-the-aged-blind-disabled-pathway/

- 40.Horwitz LI, Chang C, Arcilla HN, Knickman JR. Quantifying health systems’ investment in social determinants of health, by sector, 2017-19. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(2):192-198. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McWilliams JM, Weinreb G, Ding L, Ndumele CD, Wallace J. Risk adjustment and promoting health equity in population-based payment: concepts and evidence. Health Aff (Millwood). 2023;42(1):105-114. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sandhu S, Liu M, Wadhera RK. Hospitals and health equity—translating measurement into action. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(26):2395-2397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2211648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gondi S, Joynt Maddox K, Wadhera RK. Looking AHEAD to state global budgets for health care. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(3):197-199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2313194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huggins A, Husaini M, Wang F, et al. Care disruption during COVID-19: a national survey of hospital leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(5):1232-1238. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-08002-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology . Hospitals participating in the CMS EHR incentive programs. Published August 2017. Accessed September 18, 2023. https://www.healthit.gov/data/quickstats/hospitals-participating-cms-ehr-incentive-programs

- 46.Ryan AM, Krinsky S, Maurer KA, Dimick JB. Changes in hospital quality associated with hospital value-based purchasing. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(24):2358-2366. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1613412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Himmelstein G, Ceasar JN, Himmelstein KE. Hospitals that serve many Black patients have lower revenues and profits: structural racism in hospital financing. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(3):586-591. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07562-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Joynt KE, Jha AK. Characteristics of hospitals receiving penalties under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA. 2013;309(4):342-343. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.94856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chatterjee P, Sommers BD, Joynt Maddox KE. Essential but undefined—reimagining how policymakers identify safety-net hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2593-2595. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2030228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gilman M, Adams EK, Hockenberry JM, Milstein AS, Wilson IB, Becker ER. Safety-net hospitals more likely than other hospitals to fare poorly under Medicare’s value-based purchasing. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(3):398-405. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods 1. Methodology for Estimating HVBP Payment Adjustments

eMethods 2. Logistic Exchange Function to Calculate the Underserved Multiplier

eMethods 3. Detailed Description of Study Covariates

eTable 1. Fiscal Year 2021 Performance Period of HVBP Performance Domain Measures

eTable 2. Proportion of Dual-Eligible Inpatient Stays by Hospital Characteristics

eTable 3. Total Change in HVBP Payment Adjustments After Health Equity Adjustment by Hospital Characteristics Without 10-Point Cap

eTable 4. Total Change in HVBP Payment Adjustments After Health Equity Adjustment by Hospital Characteristics With (0,0,4) Performance Scaler

eTable 5. Total Change in HVBP Payment Adjustments After Health Equity Adjustment by Hospital Characteristics With Linear Scoring to Calculate the Underserved Multiplier

eTable 6. Total Change in HVBP Payment Adjustments After Health Equity Adjustment by Hospital Characteristics With Actual Scoring to Calculate the Underserved Multiplier

eFigure 1. Relationship Between Dual-Eligible Inpatient Stay Proportion and the Underserved Multiplier

eFigure 2. Relationship Between Rank of Dual-Eligible Inpatient Stay Proportion and the Underserved Multiplier

eFigure 3. Distribution of Dual-Eligible Inpatient Stay Proportion Across Hospitals

eFigure 4. Reclassification of Hospital Bonus/Penalty Status in the HVBP After Health Equity Adjustment

eFigure 5. Reclassification of Hospital Performance in the HVBP After Health Equity Adjustment

eFigure 6. Distribution of Hospital-Level HVBP Payment Adjustments Before and After Health Equity Adjustment

eFigure 7. Changes in Total HVBP Payment Adjustments by Quintile of Dual-Eligible Inpatient Stays

eFigure 8. Changes in Hospital-Level HVBP Payment Adjustments by Quintile of Dual-Eligible Inpatient Stays

eFigure 9. Geographical Distribution of Proportion of Hospitals Receiving Increased Payment Adjustments After Health Equity Adjustment

eFigure 10. Reclassification of Hospital Bonus/Penalty Status After Health Equity Adjustment Without 10-Point Cap

eFigure 11. Reclassification of Hospital Bonus/Penalty Status After Health Equity Adjustment With (0,0,4) Performance Scaler

eFigure 12. Reclassification of Hospital Bonus/Penalty Status After Health Equity Adjustment With Linear Scoring to Calculate the Underserved Multiplier

eFigure 13. Reclassification of Hospital Bonus/Penalty Status After Health Equity Adjustment With Actual Scoring to Calculate the Underserved Multiplier

Data Sharing Statement