This prognostic study investigates if models that incorporate routinely collected clinical and laboratory information can predict morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction.

Key Points

Question

Can models incorporating routinely collected clinical and laboratory variables predict morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)?

Findings

This prognostic study used the data of 6263 participants in the Dapagliflozin Evaluation to Improve the Lives of Patients With Preserved Ejection Fraction Heart Failure (DELIVER) trial to create models to predict the risk of composite outcome of cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization and the individual outcomes of cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality, and these models were externally validated. The models performed better than the measurement of N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide level alone.

Meaning

Prognostic Models for Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (PREDICT-HFpEF) models can be used to accurately predict outcomes in patients with HFpEF.

Abstract

Importance

Accurate risk prediction of morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) may help clinicians risk stratify and inform care decisions.

Objective

To develop and validate a novel prediction model for clinical outcomes in patients with HFpEF using routinely collected variables and to compare it with a biomarker-driven approach.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Data were used from the Dapagliflozin Evaluation to Improve the Lives of Patients With Preserved Ejection Fraction Heart Failure (DELIVER) trial to derive the prediction model, and data from the Angiotensin Receptor Neprilysin Inhibition in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (PARAGON-HF) and the Irbesartan in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction Study (I-PRESERVE) trials were used to validate it. The outcomes were the composite of HF hospitalization (HFH) or cardiovascular death, cardiovascular death, and all-cause death. A total of 30 baseline candidate variables were selected in a stepwise fashion using multivariable analyses to create the models. Data were analyzed from January 2023 to June 2023.

Exposures

Models to estimate the 1-year and 2-year risk of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure, cardiovascular death, and all-cause death.

Results

Data from 6263 individuals in the DELIVER trial were used to derive the prediction model and data from 4796 individuals in the PARAGON-HF trial and 4128 individuals in the I-PRESERVE trial were used to validate it. The final prediction model for the composite outcome included 11 variables: N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level, HFH within the past 6 months, creatinine level, diabetes, geographic region, HF duration, treatment with a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, transient ischemic attack/stroke, any previous HFH, and heart rate. This model showed good discrimination (C statistic at 1 year, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.71-0.75) in both validation cohorts (C statistic at 1 year, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.69-0.74 in PARAGON-HF and 0.75; 95% CI, 0.73-0.78 in I-PRESERVE) and calibration. The model showed similar discrimination to a biomarker-driven model including high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T and significantly better discrimination than the Meta-Analysis Global Group in Chronic (MAGGIC) risk score (C statistic at 1 year, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.58-0.63; delta C statistic, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.10-0.15; P < .001) and NT-proBNP level alone (C statistic at 1 year, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.64-0.68; delta C statistic, 0.07; 95% CI, 0.05-0.08; P < .001). Models derived for the prediction of all-cause and cardiovascular death also performed well. An online calculator was created to allow calculation of an individual’s risk.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this prognostic study, a robust prediction model for clinical outcomes in HFpEF was developed and validated using routinely collected variables. The model performed better than NT-proBNP level alone. The model may help clinicians to identify high-risk patients and guide treatment decisions in HFpEF.

Introduction

Previous studies have indicated that physicians and patients are poor at estimating prognosis without the use of a mathematical tool. Predicting risk is important as it allows for informed decision-making about care strategies and prognosis-related discussions with patients, their families, and carers.1,2 Identifying variables associated with a higher risk of death or hospitalization may also help in selecting patients for clinical trials to ensure adequate event rates and even reveal targets for intervention to improve prognosis.

Although several multivariable models that predict adverse outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) exist, most are old and do not include N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level.3,4,5,6,7 The other predictors included in these models also vary between studies, and several include complex quality-of-life variables5 or biomarkers that are not measured routinely in clinical practice.7 Importantly, most models have not been externally validated.3,4,5,6

We aimed to develop and validate a novel prediction model in a contemporary cohort, using routinely collected variables and to compare this with a recent biomarker-driven approach to prediction.

Methods

The Dapagliflozin Evaluation to Improve the Lives of Patients With Preserved Ejection Fraction Heart Failure (DELIVER) patient cohort was used for model derivation.8 The Angiotensin Receptor Neprilysin Inhibition in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (PARAGON-HF) and Irbesartan in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction Study (I-PRESERVE) cohorts were used for model validation.9,10

Trial Design

The design, baseline characteristics, and primary results of the trials have been previously published.9,11,12 All trials were approved by an ethics committee at each participating center, and all patients provided written informed consent. Participants were asked whether they belonged to one of the following racial groups: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, White, or other race (not specified), according to US Food and Drug Administration guidance. This prognostic study followed the Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) reporting guidelines.

The DELIVER trial was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial that examined the efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin, 10 mg, once daily compared with matched placebo in patients with HF and mildly reduced (mr) or pEF. Briefly, patients were eligible if they had symptomatic (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class II-IV) HF with a left ventricular EF (LVEF) greater than 40%, evidence of structural heart disease on echocardiography, and elevated BNP levels (>300 pg/mL or 600 pg/mL if atrial fibrillation or flutter; to convert to nanograms per liter, multiply by 1).

The PARAGON-HF trial was a double-blind, active-controlled, event-driven, randomized clinical trial that compared the efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan with that of valsartan in patients with HFmrEF/HFpEF. The inclusion criteria were broadly similar to those of the DELIVER trial but included patients with an LVEF of greater than 45% and required an NT-proBNP level greater than 900 pg/mL if in atrial fibrillation or flutter.

The I-PRESERVE trial was a double-blind, randomized clinical trial comparing the effects of irbesartan, 300 mg, once daily with placebo in patients with HF and an LVEF of greater than 45%; there was no BNP inclusion criterion.

Statistical Analysis

The outcomes analyzed in this study were the composite of HF hospitalization (HFH) or cardiovascular death, cardiovascular death, and all-cause death. We also constructed a model to predict the risk of HFH alone without accounting for mortality.

Multivariable analyses for each outcome were performed in a stepwise fashion. In step 1, 30 baseline candidate variables selected according to their availability across trials, ease of use in routine practice, and clinical relevance were examined. Continuous variables were inspected using restricted cubic splines and Poisson models for nonlinear effects. Age, body mass index (BMI), LVEF, and systolic blood pressure were included with a cutoff value, at which point the effect of the variable had a negligible association with the outcome. Heart rate was included as a continuous variable. A backward stepwise Cox proportional hazards model was built for each outcome, with a 2-sided P value <.10 as the initial significance level and selected variables were then taken forward to step 2.

In step 2, all initial candidate variables were evaluated for significant interaction with each outcome. For the interaction terms, a 2-sided P value <.001 was considered statistically significant. Significant interaction terms were added and selected again using a backward stepwise approach and taken forward to step 3.

In step 3, laboratory tests available across all studies (log-transformed NT-proBNP and creatinine levels) were added. Laboratory results were evaluated by visual inspection of restricted cubic splines and Poisson models to identify nonlinearity. Statistically significant laboratory tests were added to the baseline models.

Variables generated as predictive based on the duration of follow-up in the DELIVER trial (minimum and maximum 13.5 months and 39 months) were used to generate the prediction model.

The Cox model was used to obtain survival at 1 and 2 years. The predicted vs actual outcomes at 1 and 2 years were compared across quintiles of risk.

The C statistic was used to assess the discriminative ability of the model. Predicted scores from the DELIVER trial were applied to the PARAGON-HF and I-PRESERVE trials to estimate survival at 1 and 2 years. Missing data were rare, and single value imputation of the median value from the DELIVER trial for continuous variables or mode for categorical variables was used. The I-PRESERVE trial only collected information on HFH in the last 6 months (as opposed to overall).

The performance of the derived score in the DELIVER trial was also compared with the performance of the Meta-Analysis Global Group in Chronic (MAGGIC) risk score in the DELIVER, PARAGON-HF, and I-PRESERVE trials. MAGGIC is a simple integer score, developed using a multivariable risk model built after the examination of 31 candidate variables in 39 372 patients enrolled in 30 clinical trials and cohort studies.4

Analyses were performed using Stata, version 17.0 (StataCorp). Data were analyzed from January 2023 to June 2023.

Results

Data from 6263 individuals in the DELIVER trial were used to derive the prediction model and data from 4796 individuals in the PARAGON-HF trial and 4128 individuals in the I-PRESERVE trial were used to validate it. The final prediction model for the composite outcome included 11 variables: NT-proBNP level, HFH within the past 6 months, creatinine level, diabetes, geographic region, HF duration, treatment with an sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), transient ischemic attack (TIA)/stroke, any previous HFH, and heart rate. Baseline characteristics, representing the candidate variables for the prognostic models, are shown in eTable 1 in Supplement 1 according to whether patients experienced a clinical outcome of interest or not. Information on race and region are provided in eTables 1, 8, and 9 in Supplement 1 for each study. Patients experiencing a clinical outcome were older (CV death: mean [SD] age with event, 73.1 [9.9] years vs without event, 71.5 [9.5] years) and more likely to be male (CV death: with event, 311 of 492 [63.2%] males vs without event: 3205 of 5771 [55.5%] males). They had more comorbidities and were more likely to have a previous HFH (CV death with event, 145 of 492 [29.5%] vs without event, 857 of 5771 [14.9%]), especially if recent.

Predictive Models

Composite of Cardiovascular Death or HFH

The composite of CV death or HFH occurred in 475 of 3131 patients (15.2%) in the dapagliflozin group and 577 of 3132 patients (18.4%) in the placebo group. After stepwise variable selection, the prognostic model for this outcome included NT-proBNP level and recent HFH (in the last 6 months) as the most powerful predictors, based on the χ2 value. These were followed by creatinine level, history of diabetes, region (enrollment in North America), longer duration of HF, randomized treatment allocation (dapagliflozin vs placebo), history of COPD, TIA, or stroke, any previous HFH, and higher heart rate.

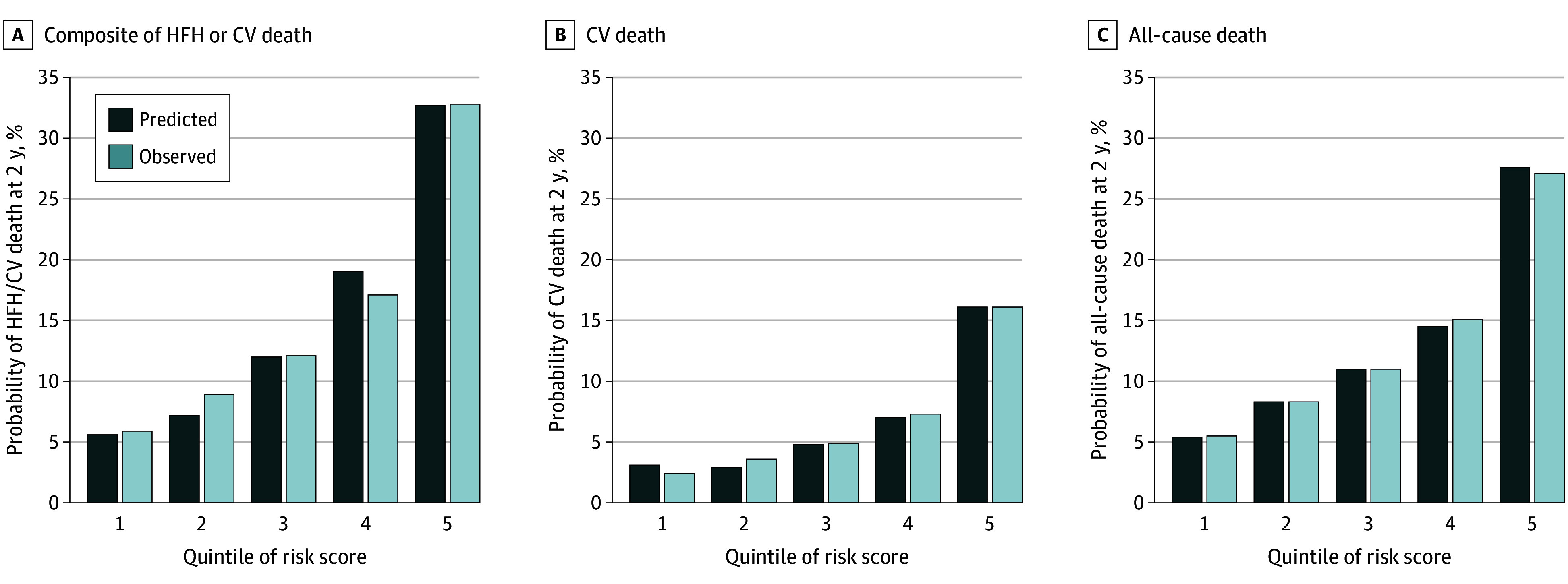

The C statistic for this model was 0.73 (95% CI, 0.71-0.75) at 1 year and 0.71 (95% CI, 0.70-0.73) at 2 years. A risk score was created from the coefficients in Table 1 and divided into 5 groups of equal size. There was good agreement between observed and model-predicted risk (Figure 1). The event rate per 100 person-years at 2 years was 17.3 (95% CI, 15.7-19.2) in the highest risk quintile vs 2.27 (95% CI, 1.78-2.91) in the lowest risk quintile (eTable 2 in Supplement 1)

Table 1. Prognostic Models for Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (PREDICT-HFpEF) Model for the Composite of Cardiovascular (CV) Death or Heart Failure Hospitalization, CV Death, and All-Cause Death.

| Characteristic | CV death or heart failure hospitalization | CV death | All-cause death | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | χ2 | Coefficient (SE) | P value | HR (95% CI) | χ2 | Coefficient (SE) | P value | HR (95% CI) | χ2 | Coefficient (SE) | P value | |

| NT-proBNP (per log unit increase) | 1.62 (1.51-1.75) | 163.1 | 0.48 (0.04) | <.001 | 1.67 (1.50-1.86) | 86.9 | 0.51 (0.06) | <.001 | 1.54 (1.42-1.66) | 120.8 | 0.43 (0.04) | <.001 |

| Heart failure hospitalization in the past 6 mo | 1.91 (1.01-1.32) | 58.4 | 0.65 (0.08) | <.001 | 1.91 (1.57-2.32) | 41.3 | 0.65 (0.10) | <.001 | 1.32 (1.11-1.58) | 9.7 | 0.28 (0.09) | .002 |

| Creatinine (per 0.0565 mg/dL increase) | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | 22.9 | 0.02 (0.004) | <.001 | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | 8.01 | 0.02 (0.01) | .005 | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | 17.6 | 0.02 (0.01) | <.001 |

| History of diabetes | 1.33 (1.17-1.50) | 20.3 | 0.28 (0.06) | <.001 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.22 (1.08-1.39) | 9.9 | 0.20 (0.06) | .002 |

| Region | 1.42 (1.21-1.68)a | 18.4 | 0.35 (0.08) | <.001 | 0.58 (0.44-0.77)b | 13.9 | −0.54 (0.14) | <.001 | 1.67 (1.43-1.96)c | 41.9 | 0.52 (0.08) | <.001 |

| Heart failure duration greater than 1 y | 1.33 (1.16-1.54) | 16.9 | 0.29 (0.07) | <.001 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Not receiving SGTL2i | 1.28 (1.32-1.44) | 15.8 | 0.25 (0.06) | <.001 | 1.18 (0.99-1.40) | 3.24 | 0.16 (0.09) | .07 | 1.11 (0.98-1.25) | 2.6 | 0.10 (0.06) | .11 |

| History of COPD | 1.39 (1.18-1.64) | 15.5 | 0.33 (0.08) | <.001 | 1.52 (1.20-1.92) | 12.4 | 0.42 (0.12) | <.001 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| History of TIA/stroke | 1.33 (1.13-1.56) | 11.6 | 0.28 (0.08) | .001 | 1.57 (1.25-1.98) | 15.0 | 0.45 (0.12) | <.001 | 1.27 (1.08-1.51) | 8.2 | 0.24 (0.08) | .004 |

| Previous heart failure hospitalization | 1.25 (1.07-1.45) | 8.2 | 0.22 (0.08) | .004 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.24 (1.06-1.45) | 7.6 | 0.22 (0.08) | .006 |

| Heart rate (per 10 bpm increase) | 1.07 (1.02-1.13) | 7.8 | 0.07 (0.03) | .005 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Body mass index <25d | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.13 (1.07-1.20) | 18.7 | 0.12 (0.03) | <.001 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ejection fraction (per 5% less than 55%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.19 (1.08-1.30) | 13.8 | 0.17 (0.05) | <.001 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Age (per 5 y increase above 70 y) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.11 (1.03-1.20) | 8.01 | 0.11 (0.38) | .005 | 1.23 (1.17-1.30) | 64.5 | 0.21 (0.03) | <.001 |

| Male sex | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.31 (1.15-1.50) | 15.9 | 0.27 (0.07) | <.001 |

| NYHA class III/IV | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.28 (1.12-1.47) | 12.4 | 0.25 (0.07) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide; SGTL2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

SI conversion factor: To convert creatinine to micromoles per liter, multiply by 88.4.

North America.

Asia.

Latin America.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Figure 1. Observed and Predicted Risk in the Dapagliflozin Evaluation to Improve the Lives of Patients With Preserved Ejection Fraction Heart Failure (DELIVER) Trial at 2 Years .

Risk for the composite of heart failure hospitalization (HFH) or cardiovascular (CV) death (A), CV death (B), and all-cause death (C) for patients categorized by quintile of risk score. Quintiles of risk score are graded from low risk (1) to high risk (2).

Cardiovascular Death

Cardiovascular death occurred in 231 of 3131 patients (7.4%) in the dapagliflozin group and 261 of 3132 patients (8.3%) in the placebo group. The prognostic model for cardiovascular death also included NT-proBNP level and recent HFH as the most powerful predictors (Table 1). In addition, creatinine level, region (enrollment in Asia), randomized treatment allocation, history of COPD, and TIA or stroke were associated with cardiovascular death as well as the primary composite outcome. However, the model for cardiovascular death included older age, lower LVEF, and BMI, which were not in the model for the composite outcome (and diabetes, longer duration HF, any prior HFH, and higher heart rate, which were associated with the composite outcome, were not included in the model for cardiovascular death).

The C statistic for cardiovascular death was 0.75 (95% CI, 0.71-0.79) and 0.71 (95% CI, 0.68-0.74) at 1 year and 2 years respectively. Quintiles of risk showed good agreement between observed and predicted risk with a strong gradient of risk (Figure 1).

All-Cause Death

Death from any cause occurred in 497 of 3131 patients (15.9%) in the dapagliflozin group and 526 of 3132 patients (16.8%) in the placebo group. The strongest predictor within the prognostic model for all-cause death was NT-proBNP level (as for the other outcomes), but recent HFH was a weaker predictor than in the other models (Table 1). The variables associated with all-cause mortality largely overlapped with those included in the model for cardiovascular death except for COPD, higher heart rate, LVEF, and BMI (cardiovascular death only) and NYHA class and male sex (all-cause death only).

The C statistic for all-cause death was 0.71 (95% CI, 0.68-0.74) at 1 year and 0.68 (95% CI, 0.66-0.70) at 2 years. Quintiles of risk showed good agreement between observed and predicted risk with a strong gradient of risk (Figure 1).

HFH

In a model derived to predict HF hospitalizations, NT-proBNP level and HFH within the last 6 months were the largest contributors to the model (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). The model performed well with an overall C statistic of 0.72 (95% CI, 0.70-0.74) in the derivation cohort from the DELIVER trial but declined to 0.66 (95% CI, 0.64-0.67) when the model was tested in the PARAGON-HF trial. Similar results were seen for 1- and 2-year predictions (eTable 4 in Supplement 1).

Common Variables

Many of the predictive variables were the same in each of the 3 models (Table 1). The common variables were NT-proBNP and creatinine level, history of HFH within the previous 6 months, and history of TIA/stroke.

NT-proBNP level was the strongest predictor of each of the 3 outcomes. Model performance was better with the inclusion of NT-proBNP level and substantially better than NT-proBNP level alone (Table 2 and eTable 6 in Supplement 1) or HFH within the last 6 months alone (eTables 5 and 6 in Supplement 1).

Table 2. Model Performance With and Without N-Terminal Pro–Brain Natriuretic Peptide (NT-proBNP) Level Assessed by Harrell C Statistic.

| C statistic (95% CI) | Difference in C statistic (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) NT-proBNP alone | (2) Baseline model without NT-proBNP | (3) Baseline model with NT-proBNP | (2) vs (1) | P value | (3) vs (1) | P value | |

| HFH/CV death | |||||||

| 1 y | 0.66 (0.64 to 0.68) | 0.70 (0.68 to 0.72) | 0.73 (0.71 to 0.75) | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.06) | .01 | 0.07 (0.05 to 0.09) | <.001 |

| 2 y | 0.65 (0.63 to 0.66) | 0.68 (0.66 to 0.70) | 0.71 (0.69 to 0.73) | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.05) | .009 | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.08) | <.001 |

| CV death | |||||||

| 1 y | 0.69 (0.65 to 0.73) | 0.72 (0.68 to 0.76) | 0.75 (0.71 to 0.79) | 0.03 (−0.02 to 0.08) | .24 | 0.06 (0.03 to 0.09) | <.001 |

| 2 y | 0.65 (0.62 to 0.68) | 0.69 (0.66 to 0.71) | 0.71 (0.68 to 0.74) | 0.04 (0 to 0.07) | .03 | 0.06 (0.04 to 0.08) | <.001 |

| All-cause death | |||||||

| 1 y | 0.65 (0.62 to 0.68) | 0.68 (0.65 to 0.71) | 0.71 (0.68 to 0.74) | 0.02 (−0.01 to 0.06) | .22 | 0.05 (0.03 to 0.07) | <.001 |

| 2 y | 0.62 (0.60 to 0.64) | 0.66 (0.64 to 0.68) | 0.68 (0.66 to 0.70) | 0.04 (0.02 to 0.06) | <.001 | 0.06 (0.04 to 0.07) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: CV, cardiovascular; HFH, heart failure hospitalization.

Missing Data

The extent of missing data for the derivation cohort is shown in eTable 7 in Supplement 1. Data were complete for 25 of 32 candidate variables. The proportion of missing data ranged from 0.015% to 0.03%.

External Validation of the Models

The DELIVER model was validated in the PARAGON-HF and I-PRESERVE trial datasets. Baseline characteristics according to outcomes for both trials are shown in eTables 8 and 9 in Supplement 1. The extent of missing data for each study is shown in eTable 10 in Supplement 1.

Application of the model derived from the DELIVER to PARAGON-HF trials gave C statistics for the composite outcome at 1 and 2 years of 0.71 (95% CI, 0.69-0.74) and 0.68 (95% CI, 0.66-0.70), respectively. The C statistics for cardiovascular and all-cause death at 1 year were 0.70 (95% CI, 0.65-0.74) and 0.67 (95% CI, 0.63-0.71), respectively. At 2 years, the C statistics were 0.68 (95% CI, 0.65-0.71) and 0.67 (95% CI, 0.64-0.69), respectively.

Applying the model for the composite outcome to I-PRESERVE gave C statistics at 1 and 2 years of 0.75 (95% CI, 0.73-0.78) and 0.73 (95% CI, 0.71-0.75), respectively. The C statistics for cardiovascular and all-cause death at 1 year were 0.75 (95% CI, 0.71-0.79) and 0.74 (95% CI, 0.70-0.77), respectively, and at 2 years were 0.73 (95% CI, 0.70-0.76) and 0.73 (95% CI, 0.71-0.76), respectively.

Comparison With Other Prognostic Models

MAGGIC Risk Score

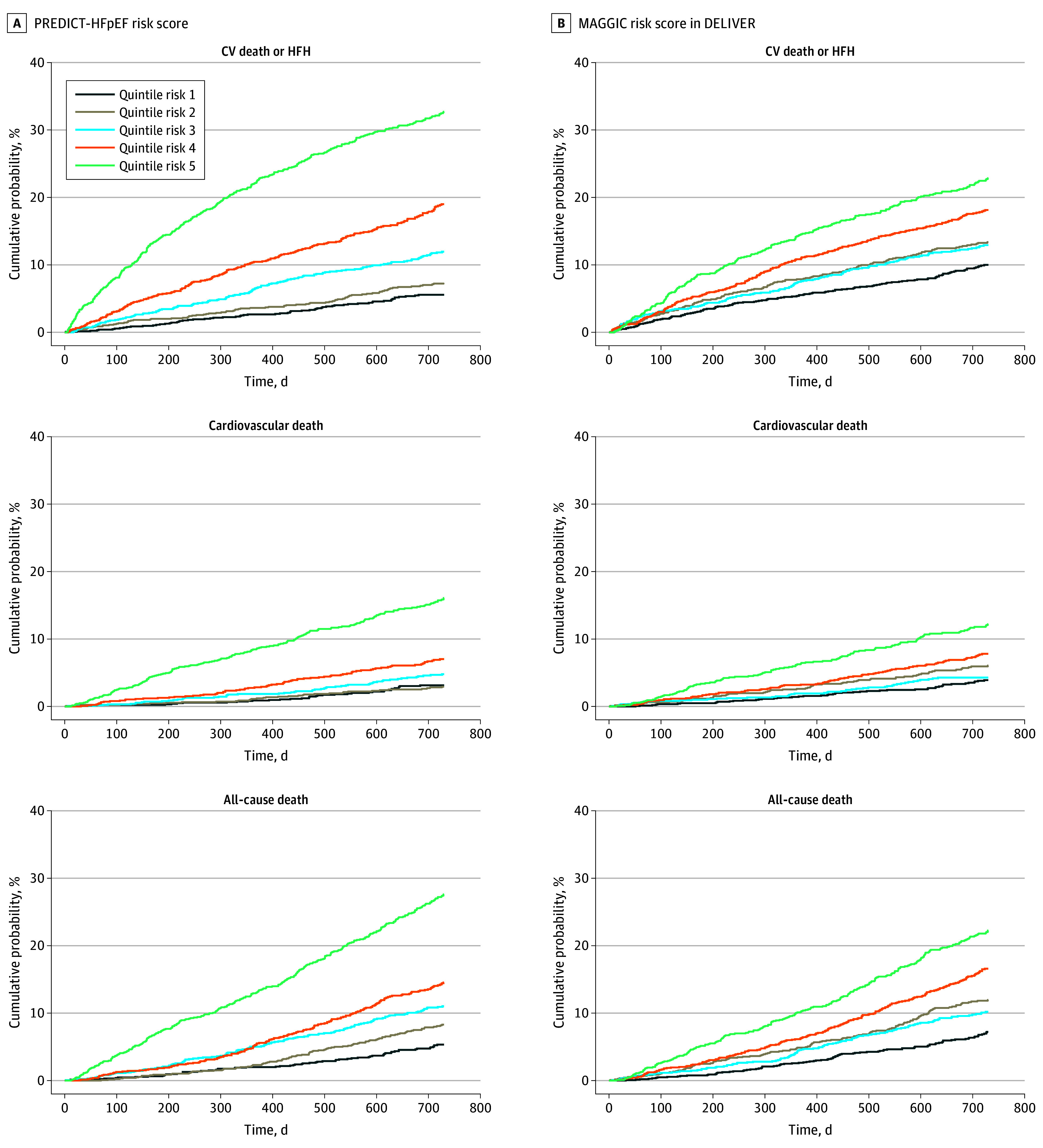

Applying the MAGGIC integer score to the DELIVER dataset resulted in poor risk discrimination at 1 and 2 years for the composite end point (C statistic, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.58-0.63 and 0.59; 95% CI, 0.58-0.61), cardiovascular death (0.65; 95% CI, 0.61-0.69 and 0.62; 95% CI, 0.59-0.65), and all-cause death (0.63; 95% CI, 0.60-0.66 and 0.62; 95% CI, 0.60-0.64). The gradient in observed risk for composite outcome was not as steep with quintiles of MAGGIC risk score as with the present model (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Plots for Observed Event Rate at 1 Year According to Quintiles of Risk Score.

A, Prognostic Models for Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (PREDICT-HFpEF) risk score. B, Meta-Analysis Global Group in Chronic (MAGGIC) risk score in the Dapagliflozin Evaluation to Improve the Lives of Patients With Preserved Ejection Fraction Heart Failure (DELIVER) trial. CV indicates cardiovascular; HFH, HF hospitalization.

The PREDICT-HFpEF model performed better in terms of discrimination than the MAGGIC integer score for all outcomes examined at 1 and 2 years (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of Prognostic Models for Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (PREDICT-HFpEF) Model Performance With the Meta-Analysis Global Group in Chronic (MAGGIC) Score in the Angiotensin Receptor Neprilysin Inhibition in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (PARAGON-HF) and Irbesartan in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction Study (I-PRESERVE) Trials and to the Empagliflozin in Heart Failure With a Preserved Ejection Fraction (EMPEROR-Preserved) Risk Model in the Subset of Patients in the PARAGON-HF Trial With High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin-T Available.

| Outcome | PARAGON-HF (All) | PARAGON-HF (subset) | I-PRESERVE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C statistic (95% CI) | P valuea | C statistic (95% CI) | P valuea | C statistic (95% CI) | P valuea | |

| HFH/CV death | ||||||

| PREDICT-HFpEF | 0.68 (0.66-0.70) | NA | 0.71 (0.67-0.75) | NA | 0.73 (0.71-0.75) | NA |

| EMPEROR-Preserved | NA | NA | 0.71 (0.67-0.75) | .74 | NA | NA |

| MAGGIC | 0.59 (0.57-0.61) | <0.001 | 0.60 (0.55-0.64) | <.001 | 0.63 (0.60-0.65) | <.001 |

| CV death | ||||||

| PREDICT-HFpEF | 0.68 (0.65-0.71 | NA | 0.71 (0.64-0.79) | NA | 0.73 (0.70-0.76) | NA |

| EMPEROR-Preserved | NA | NA | 0.72 (0.65-0.78) | .86 | NA | NA |

| MAGGIC | 0.63 (0.59-0.66) | 0.009 | 0.65 (0.58-0.73) | .17 | 0.64 (0.60-0.68) | <.001 |

| All-cause death | ||||||

| PREDICT-HFpEF | 0.67 (0.64-0.69) | NA | 0.69 (0.63-0.74) | NA | 0.73 (0.71-0.76) | NA |

| EMPEROR-Preserved | NA | NA | 0.72 (0.67-0.77) | .18 | NA | NA |

| MAGGIC | 0.63 (0.61-0.66) | 0.009 | 0.64 (0.58-0.70) | .09 | 0.66 (0.63-0.69) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: CV, cardiovascular; HFH, HF hospitalization; NA, not applicable.

P value compares model performance to that of PREDICT-HFpEF.

EMPEROR-Preserved Biomarker-Driven Risk Model

The variables included in the present model for the composite end point overlapped with those included in the recently published biomarker-driven EMPEROR-Preserved risk model.7 Common variables were NT-proBNP level, recent HFH, history of COPD and diabetes, as well as the use of SGLT2 inhibitors.

The EMPEROR-Preserved model performed well in the subset of patients in the PARAGON-HF trial with biomarkers available, with a C statistic at 2 years greater than 0.70 for all 3 outcomes of interest (Table 3). However, the present model also performed well in this subset of patients from the PARAGON-HF trial, with similar C statistics without the inclusion of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn)–T level(Table 3). The addition of hs-cTn–T level to the present models did not improve discrimination for the composite outcome or cardiovascular death but did improve discrimination for all-cause death: C statistic at 2 years 0.71 (95% CI, 0.66-0.77) vs 0.69 (95% CI, 0.63-0.74; P =.02).

Calculating the Estimated Risk of an Individual

An online calculator was created to allow calculation of an individual’s risk.13 The calculator provides an estimate of the individualized risk of the composite outcome of cardiovascular death or HFH and the outcomes of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.

Discussion

The prognostic models we derived in the DELIVER cohort and extensively validated in 2 separate HFpEF trial datasets were effective at predicting the risk of mortality and morbidity in patients with HFpEF. The models include routinely collected variables only, for ease of use and practical value and were developed from patients from across the world. Our models performed better than previously developed models and similarly to models relying on biomarkers that are not routinely measured in clinical practice.

Elevated levels of NT-proBNP were by far the strongest predictor of the 3 outcomes of interest. The prognostic value of NT-proBNP has been reported previously in patients with HF regardless of EF.5,7,14,15,16 However, we have demonstrated that incorporating other routine clinical variables, which are also predictive of poor outcomes, provided superior risk discrimination than NT-proBNP level alone.

A recently published biomarker-driven prediction model demonstrated that hs-cTn–T levels added complementary and independent prognostic information to NT-proBNP level in patients with HFpEF.7 However, hs-cTn–T level is not routinely measured in patients with HFpEF. Our model performed as well as this biomarker-driven prediction model offering an alternative, more routinely applicable approach to prediction beyond that offered by measuring additional biomarkers.

Given the strength of the evidence supporting NT-proBNP level as a prognostic marker, we believe that contemporary models should include NT-proBNP level as a minimum, especially as, unlike troponins, natriuretic peptides are routinely measured biomarkers in patients with HFpEF. Two previously published HFpEF risk models, Candesartan in Heart Failure Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity (CHARM) and Meta-Analysis Global Group in Chronic Heart Failure Risk Score (MAGGIC), did not include natriuretic peptides as these were not routinely measured at the time when these models were created.3,4 When we applied the MAGGIC integer score to the DELIVER cohort, it provided lower discriminatory power with a C statistic of 0.59 for the risk of cardiovascular death or HFH at 2 years.

The second most significant predictor of the composite of cardiovascular death or HFH was an HFH within the prior 6 months. This is in keeping with previous reports that a recent hospitalization is associated with a 2- to 3-fold higher risk of rehospitalization and a higher risk of cardiovascular death.17

The variables that did not overlap in the predictive models are also of interest. For example, older age was retained only in the mortality models, suggesting that hospitalizations are less dependent on age.

It is also notable that the model for all-cause mortality performed worse than the models for the composite outcome (cardiovascular death or HFH) and for cardiovascular death in terms of discrimination. This likely reflects substantial proportion of deaths that are noncardiovascular in patients with HFpEF and uncertainty about (or unavailability of) variables that predict noncardiovascular death compared to the variables known to predict cardiovascular outcomes.

Our model for HFH also found that NT-proBNP level was the most important predictor. It performed well in the derivation cohort and the C statistic remained reasonable after testing in the PARAGON-HF trial. In this model (but not the models for other outcomes), the coefficient for the association between angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) therapy and HFH suggested an association with higher risk. However, ARNI therapy was not randomized in the DELIVER trial, and this finding likely reflects confounding by indication. Indeed, we found an interaction between ARNI use and the North America region in the model. Patients had a lower EF in North America. We believe the association with ARNI use is confounded by prescribing patterns for ARNIs in North America where the US Food and Drug Administration has issued a broader indication covering HFpEF, which was not the case for many of the other global regions included in the DELIVER trial and led to the drug being used in sicker patients who are at higher risk for HF hospitalization.

Strengths and Limitations

A particular strength of our model is its extensive external validation in 2 separate HFpEF datasets, reinforcing the evidence that it performs adequately in different HFpEF populations from around the world. It was also notable that the model performed as well in the I-PRESERVE trial as in the DELIVER and PARAGON-HF trials, as, unlike these other 2 trials, the I-PRESERVE trial did not have an NT-proBNP entry criterion (although NT-proBNP level was measured in most patients in a core laboratory), and approximately 25% of patients in the I-PRESERVE trial had normal NT-proBNP concentrations (ie, <125 pg/mL), a similar proportion to those reported in observational cohort studies of patients with HFpEF.18

We believe that our prognostic model will be of use to a wide range of health care professionals caring for patients with HFpEF. It can be used to discuss prognosis with patients and families as well as communicate prognosis with other health care professionals when planning therapy for other diseases where knowledge of likely prognosis may influence treatment decisions.19 As electronic health care record systems become more widespread, the risk of the population covered could be calculated to help plan health care resources. In time, risk prediction scores could be used to determine enrollment into clinical trials and even find high-risk groups who respond to therapy.20

Both the derivation and main validation datasets were obtained from clinical trials and, therefore, included relatively selected patients. The accessibility and clinical application might be easier if we had created an integer score, but this would have resulted in loss of some predictive accuracy.

Conclusions

The DELIVER HFpEF models described in this prognostic study, based on readily available clinical and laboratory variables, accurately predicted morbidity and mortality at 1 and 2 years. Clinically, the model can be used to predict outcomes with the potential for targeting services and even therapies as more are investigated and become available for patients with HFpEF.

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics and Treatment by End Point in DELIVER Derivation Cohort

eTable 2. Event Rate per 100 Person-Years for Each Risk Quintile at 2 Years

eTable 3. PREDICT-HFpEF Model for the Outcome of Heart Failure Hospitalization (HFH)

eTable 4. Performance of Model for Heart Failure Hospitalization in Derivation (DELIVER) and Validation (PARAGON-HF) Cohort by Harrell C Statistic

eTable 5. Model Performance With and Without HF Hospitalization Within Last 6 Months Assessed by Harrell C Statistic

eTable 6. Reclassification of Base Model With Addition of NTproBNP and HF Hospitalization Within Last 6 Months

eTable 7. List of Candidate Variables and Extent of Missing Data: DELIVER

eTable 8. Baseline Characteristics and Treatment by End Point in PARAGON-HF Validation Cohort

eTable 9. Baseline Characteristics and Treatment by End Point in I-Preserve Validation Cohort

eTable 10. Extent of Missing Data: PARAGON HF and I-Preserve

Data Sharing Statement.

References

- 1.Allaudeen N, Schnipper JL, Orav EJ, Wachter RM, Vidyarthi AR. Inability of providers to predict unplanned readmissions. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(7):771-776. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1663-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen LA, Yager JE, Funk MJ, et al. Discordance between patient-predicted and model-predicted life expectancy among ambulatory patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2008;299(21):2533-2542. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.21.2533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pocock SJ, Wang D, Pfeffer MA, et al. Predictors of mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(1):65-75. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rich JD, Burns J, Freed BH, Maurer MS, Burkhoff D, Shah SJ. Meta-Analysis Global Group in Chronic (MAGGIC) heart failure risk score: validation of a simple tool for the prediction of morbidity and mortality in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(20):e009594. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Komajda M, Carson PE, Hetzel S, et al. Factors associated with outcome in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: findings from the Irbesartan in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Study (I-PRESERVE). Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4(1):27-35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.932996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasahara S, Sakata Y, Nochioka K, et al. The 3A3B score: the simple risk score for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction—a report from the CHART-2 study. Int J Cardiol. 2019;284:42-49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.10.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pocock SJ, Ferreira JP, Packer M, et al. Biomarker-driven prognostic models in chronic heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the EMPEROR-Preserved trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24(10):1869-1878. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Claggett B, et al. ; DELIVER Trial Committees and Investigators . Dapagliflozin in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(12):1089-1098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon SD, Rizkala AR, Gong J, et al. Angiotensin Receptor Neprilysin Inhibition in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: rationale and design of the PARAGON-HF Trial. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5(7):471-482. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Massie BM, Carson PE, McMurray JJ, et al. ; I-PRESERVE Investigators . Irbesartan in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(23):2456-2467. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solomon SD, de Boer RA, DeMets D, et al. Dapagliflozin in heart failure with preserved and mildly reduced ejection fraction: rationale and design of the DELIVER trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23(7):1217-1225. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carson P, Massie BM, McKelvie R, et al. ; I-PRESERVE Investigators . The irbesartan in heart failure with preserved systolic function (I-PRESERVE) trial: rationale and design. J Card Fail. 2005;11(8):576-585. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.06.432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.PREDICT-HFpEF . HFpEF risk calculator. Accessed February 29, 2024. https://predict-hfpef.com

- 14.Simpson J, Jhund PS, Lund LH, et al. Prognostic models derived in PARADIGM-HF and validated in ATMOSPHERE and the Swedish Heart Failure Registry to predict mortality and morbidity in chronic heart failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(4):432-441. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.5850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunningham JW, Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, et al. Effects of sacubitril/valsartan on N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(5):372-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pocock SJ, Ferreira JP, Gregson J, et al. Novel biomarker-driven prognostic models to predict morbidity and mortality in chronic heart failure: the EMPEROR-Reduced trial. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(43):4455-4464. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, Desai AS, et al. Prior heart failure hospitalization, clinical outcomes, and response to sacubitril/valsartan compared with valsartan in HFpEF. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(3):245-254. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anjan VY, Loftus TM, Burke MA, et al. Prevalence, clinical phenotype, and outcomes associated with normal B-type natriuretic peptide levels in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(6):870-876. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aaronson KD, Cowger J. Heart failure prognostic models: why bother? Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5(1):6-9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.965848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kattan MW, Vickers AJ. Incorporating predictions of individual patient risk in clinical trials. Urol Oncol. 2004;22(4):348-352. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2004.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics and Treatment by End Point in DELIVER Derivation Cohort

eTable 2. Event Rate per 100 Person-Years for Each Risk Quintile at 2 Years

eTable 3. PREDICT-HFpEF Model for the Outcome of Heart Failure Hospitalization (HFH)

eTable 4. Performance of Model for Heart Failure Hospitalization in Derivation (DELIVER) and Validation (PARAGON-HF) Cohort by Harrell C Statistic

eTable 5. Model Performance With and Without HF Hospitalization Within Last 6 Months Assessed by Harrell C Statistic

eTable 6. Reclassification of Base Model With Addition of NTproBNP and HF Hospitalization Within Last 6 Months

eTable 7. List of Candidate Variables and Extent of Missing Data: DELIVER

eTable 8. Baseline Characteristics and Treatment by End Point in PARAGON-HF Validation Cohort

eTable 9. Baseline Characteristics and Treatment by End Point in I-Preserve Validation Cohort

eTable 10. Extent of Missing Data: PARAGON HF and I-Preserve

Data Sharing Statement.