Abstract

The uridine modifications pseudouridine (Ψ), dihydrouridine, and 5-methyluridine are present in eukaryotic mRNAs. Many uridine-modifying enzymes are associated with human disease, underscoring the importance of uncovering the functions of uridine modifications in mRNAs. These modified uridines have chemical properties distinct from those of canonical uridines, which impact RNA structure and RNA-protein interactions. Pseudouridine, the most abundant of these uridine modifications, is present across (pre-)mRNAs. Recent work showed that many pseudouridines are present at intermediate to high stoichiometries, likely conducive to function and at locations poised to influence pre-/mRNA processing. Technological innovations and mechanistic investigation are unveiling the functions of uridine modifications in pre-mRNA splicing, translation, and mRNA stability, which are discussed in this review.

Keywords: mRNA modifications, pseudouridine, splicing, translation, mRNA stability, pre-mRNA processing

Introduction to uridine modifications in mRNAs

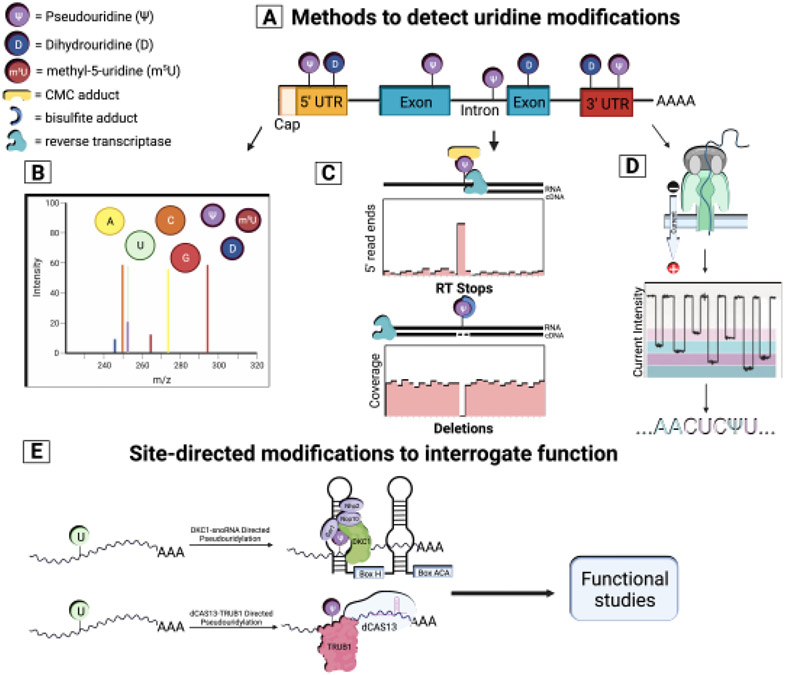

mRNA modifications are emerging as major regulators of mRNA fate and function. The cellular functions of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) in gene regulation have been intensely investigated, while studies on the function of uridine modifications in mRNA have been limited. The toolbox for monitoring both uridine modification levels and locations and interrogating their functions has rapidly expanded over the last few years, catapulting the discovery of the role of these modifications in diverse aspects of mRNA metabolism (Figure 1A). Here we contextualize these recent advances and highlight key areas for future investigations. First, we describe the methods for detecting and studying uridine modifications, focusing on pseudouridine (Ψ). We then discuss the writers of Ψ and the molecular impacts of Ψ on RNA structure and RNA-protein interactions before exploring the known and potential functions of Ψ-modified mRNA, focusing on mammalian mRNA processing, translation, and stability. We compare Ψ with other uridine modifications (Box 1) that have been detected in mRNA and discuss how their functions in mRNA metabolism are ripe for investigation (Box 2).

Figure 1. Uridine modifications in mRNA.

a) Distribution of uridine modification across mRNAs. b) Digestion of mRNAs followed by bulk nucleoside LC/MS is applied to determine the presence and absolute abundance of uridine modifications within mRNAs based on spectra intensity and mass shift of modified compared to unmodified nucleoside. c) Sequencing-based mapping tools reliant on chemical derivatization of modifications (CMC and bisulfite) and reverse transcriptase signatures (RT stops and deletions respectively) are used to identify the location, and with the aid of synthetic standards, the stoichiometry of uridine modifications transcriptome-wide. d) Direct RNA long-read sequencing with Nanopore Technology allows identification of co-occurring uridine modifications within full-length mRNAs based on signal differences (e.g. current intensity,) as modified compared to unmodified mRNAs translocate through Nanopores. e) Site-directed modifications to interrogate functions. Recently, engineered snoRNAs with base complementary to target sites of interest have allowed site-specific installation of individual pseudouridines in mRNA by the pseudouridine synthase DKC1. PUSs have been fused to dead RNA targeting CAS13 (dCAS13) to install Ψ at specific locations directed by guide RNAs (gRNA). Although some challenges remain, these and new technologies could represent tools to study the direct functions of individual modifications in mRNAs.

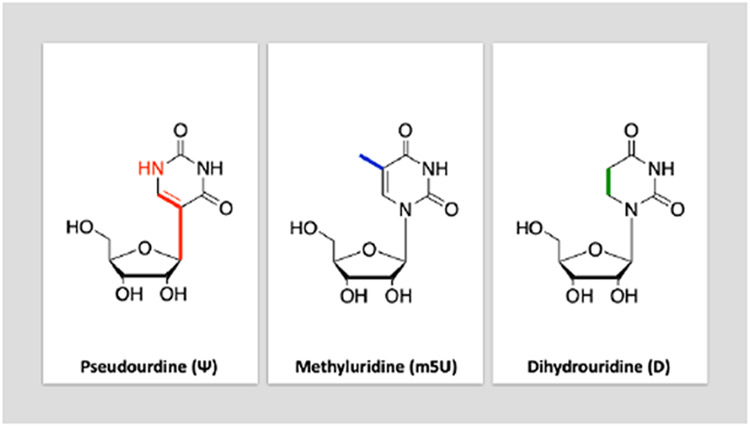

Box 1. The chemistry of uridine modifications.

The distinct chemistry of the uridine modifications pseudouridines (Ψ), dihydrouridine (D), and 5-methyluridine (m5U) is expected to account for their functional differences (Figure I). Ψ, an isomer of uridine, contains a C-C bond between the C1 of the ribose sugar and C5 of uracil instead of the C-N bond attaching the ribose sugar and uracil in canonical uridine [73]. This distinction allows Ψ to have greater rotational and conformational flexibility, while increasing hydrogen-bonding potential and base-stacking interactions [71]. The extra hydrogen bond donor can hydrogen-bond with a water molecule and bridge an interaction with the backbone phosphate and rigidify the backbone. D, another modified base, differs from U in its fully saturated uracil lacking the C5-C6 alkene. This lack of double bond makes dihydrouridine nonplanar, thereby altering conformational preference and stacking interactions [88,89]. m5U deviates from U in its methylated C5 [90].

Box 2. Other uridine modifications - dihydrouridine and 5-methyluridine.

Recent advances suggest that other modifications to uridine are part of the epitranscriptome, which urges studies on functional interplay. While D and m5U have been found in mRNAs, only the locations of Ds have been mapped. Approximately 150 D sites, distributed among the 5′ UTR, CDS, and 3′ UTR, were found in yeast by the derivatization of the modification with sodium borohydride and reverse transcriptase stops [91,92]. DUS3L is a major dihydrouridine synthase in humans accounting for ~60% of mRNA dihydrouridines. TRMT2A is the primary m5U mRNA methyltransferase as inferred from crosslinking studies trapping RNAs covalently during catalysis and bulk nucleoside mass spec [2-4,93]. Crosslinking experiments with uridine analogs that covalently trap DUS3L with target RNAs identified hundreds of non-tRNA sequences including mRNAs. These putative sites were mostly in intronic or non-coding regions suggesting the interesting possibility that D, like Ψ, might be added to pre-mRNAs[4]. In yeast, analysis of intronic reads from a Dus null strain led to a modest increase in intronic reads of the RPL30 gene in yeast [91], suggesting that the impact of D on splicing should be investigated.

Artificial incorporation of m5U in phenylalanine codons has been shown to affect translation efficiency in a context dependent matter [3]. Artificial incorporation of D-modified codons in translation reporters were translated with similar efficiency in one study, but modestly decreased translation in another [91,92]. Differences in the translation extract sources and context dependent effects may explain the differences. D was found to be in more exposed and flexible positions on mRNA, likely due to changes in the backbone conformation that disfavors the typical RNA helix and allows for higher flexibility [91,92]. The large impact that D has on structure through stabilization of the C-2′-endo sugar orientation due to the nonplanar nature of the base compared to U [89] suggests that its presence in mRNA might lead to functional consequences. Given that Ψ and D favor opposite sugar pucker conformation, and one rigidifies while the other makes the backbone more flexible, it will be of interest to study their interplay.

These studies point toward uridine modifications as potential regulators of mRNA processing and as a new frontier in the field of RNA biology. Future work will likely investigate these uridine modifications in a variety of mRNA contexts to understand their functions and mechanisms by which they impact gene expression.

Developments in the study of uridine modifications in mRNAs

Detecting the abundance of uridine modifications in mRNA by mass spectrometry

Ψ is the most prevalent of the uridine modifications, comprising 0.2-0.6% [1] of uridines in mRNA. This is comparable in prevalence to m6A, the most well-studied modification of mRNA. The modified bases 5-methyluridine (m5U) (0.00094%) [2] and dihydrouridine (D) (<0.0001%) [3] also comprise the mRNA epitranscriptome, albeit at a lower abundance (Boxes 1 and 2). These estimates are based on LC/MS detection of nucleosides, which gives quantitative readouts of modification levels within mRNA species. For mRNAs, this technique is limited to digestion into single nucleosides prior to detection; while this provides absolute and quantitative modification levels in the samples, the drawback is the consequent loss of any information about modification locations. An additional important consideration is that the input mRNA must be sufficiently pure to avoid misleading signals from contaminating abundant and highly modified RNAs like tRNAs. Indeed, inclusion of a panel of tRNA modification standards and subsequent RNA-seq analysis can further help assess purity [3,4]. With further improvements in mRNA digestion, LC/MS instrumentation and data processing, important information like modification location could be retained, along with absolute quantification of stoichiometry for mRNAs.

Determining the location and stoichiometry of pseudouridines in mRNAs

Hundreds to thousands of Ψs have been identified and their locations mapped in mRNA using high-throughput Ψ profiling methods, including Ψ-seq (see Glossary), Pseudo-seq, CeU-Seq, BID-seq, and PRAISE [5-10]. Original maps were sparse, limited to the most highly expressed genes in each of the profiled cell lines and different methods have distinct biases and blind spots, leading to limited overlap of called sites. In more recent years, as more maps have emerged from a variety of cell types and through use of orthogonal methods, such as distinct chemistry and sequencing library construction, many sites have been validated across more than one method and dataset [7,9,11-14]. Mapping of Ψ in mRNAs has revealed that it is present in every landmark region of an mRNA from end to end, including 5′Untranslated regions (UTRs), internal exons, introns, and 3′UTRs, without a strong bias and underrepresentation in 5′UTRs reported. Thus, in principle, this broad distribution endows Ψ with the ability to influence any aspect of mRNA metabolism, whether that is splicing, 3′end processing, export, translation, or mRNA turnover.

Initially, Ψ profiling methods (Ψ-seq, Pseudo-seq, CeU-Seq) relied on derivatization of Ψs with N-cyclohexyl-N′-β-(4-methylmorpholinium)ethylcarbodiimide (CMC), resulting in reverse transcription stops that are detectable by Illumina sequencing of the truncated cDNAs [1,6,15]. Incomplete and context dependent derivatization of Ψ with CMC and on the behavior of reverse transcriptase at Ψ-CMC adducts prevent it from achieving absolute quantification. Ψ can also be chemically labeled with bisulfite (RBS-seq) [16], and recent improvements on the initial reaction conditions have allowed for more efficient, near-complete chemical labeling of Ψ sites with bisulfite that results in adducts that can be quantified from deletion signatures during reverse transcription (BID-seq and PRAISE) [8,9]. These methods have expanded the list of validated Ψ sites and, with the aid of synthetic standards in 256 sequence contexts, have allowed estimation of the stoichiometry at these individual sites [8,9]. Most Ψs in HeLa and HEK293 human cell lines displayed intermediate to high stoichiometry (>20% of the uridines at individual sites within a given mRNA), with a median of 10-30% [8,9]. Comparatively, recent estimates of m6A stoichiometries have revealed median stoichiometries of <20% [17,18]. These results support the premise that Ψ is broadly present at levels high enough to be conducive to functional impact.

Identifying pseudouridines in full length mRNAs

Direct RNA long-read sequencing (with Nanopore technology) is a promising approach for detecting Ψs while retaining the context of full-length transcripts. This approach could facilitate relating modifications with specific mRNA isoforms and detection of modifications that co-occur within the same mRNA molecule, which is not possible using other approaches that rely on short-read Illumina sequencing. Thus, direct long-read sequencing of RNA could facilitate functional interrogation of uridine modifications in mRNA processing and reveal how multiple modifications might act at different ends of transcripts to determine their fate. Ψs can be distinguished from uridines based on deviations in ionic current, dwell time, and characteristic U-to-C base calling errors as RNA is threaded through a Nanopore [14,19-21]. Using this approach, individual mRNAs have been shown to contain up to 7 unique uridine modification sites [14]. A few candidate Ψs have been found to be independent of each other, while other pairs of sites appear to be anti-correlated [21]. These approaches open avenues for studying the coordinated regulation and function of multiple modifications within a single mRNA.

While promising, Nanopore technology is limited currently by low signal-to-noise ratio, background base-calling errors, and context-dependent effects. To address these issues, genetic knockouts and/or in vitro transcribed unmodified transcriptomes are used as negative controls. Conversely, synthetic standards with individual modifications at different stoichiometries in sequence contexts of interest are used as positive controls [14,22]. Machine learning models can be trained on ground-truth positive control data to derive predictive models for modification sites [20,23]. As the ability of nanopore technology to differentiate between unmodified nucleosides and modified nucleosides further improves, the use of the technology could become key to functional studies of the epitranscriptome.

Writers of pseudouridine on mRNA

RNA modifying enzymes, or “writers”, are responsible for carrying out uridine modifications in mRNA. The expression and activity of uridine modification writers is regulated in response to environmental cues and across cell types. Further, mutations or altered expression of these RNA modifying enzymes have been linked to numerous diseases [24] (Table 1), underscoring their importance in the proper regulation of cellular processes and organismal function.

Table 1.

Writers of uridine modifications in mRNAs.

| Enzy me |

Motif | Substrates a |

Localizati on |

Function in mRNA |

Disease Associationb |

References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ψ | PUS1 | HRU at the base of a bulged stem loop | mRNA, tRNA, mt-tRNA (Patton 2005) | Nucleus, mitochondria | Alternative splicing, alternative polyadenylation, translation – stop codon readthrough | MLASA, osteoarthritis, hepatocellular carcinoma | [7,8,94-96,9,26,32,50,55-58] |

| PUSL1 | - | mRNA | Mitochondrial inner membrane | - | Hepatocellular carcinoma | [8,32,97] | |

| PUS3 | - | mRNA, tRNA | Nucleus, cytoplasm | - | Neurodevelopment | [8,37-42,98] | |

| PUS7 | UNUAG | mRNA, tRNA | Nucleus | mRNA abundance, alternative splicing, alternative polyadenylation | Neurodevelopment, age-related macular degeneration, hepatocellular carcinoma, glioblastoma, colorectal cancer | [1,5,32-36,43-47,6,48,7-9,13,26,27,30] | |

| PUS7L | - | mRNA, tRNA | Nuclear speckles, nucleoli | - | - | [7,8,98] | |

| PUS10 | - | mRNA, tRNA | Nucleus, nuclear bodies, mitochondria | - | Ulcerative colitis and celiac disease, Crohn’s disease | [7,51,52,98] | |

| TRUB1 | GUUCNA NNC At 2nd base in 7 bp loop with 5 bp stem | mRNA, tRNA, mt-tRNA (Jia 2022) | Nucleus, mitochondria, vesicles | mRNA stability | - | [1,5,7– 9,13,26,99] | |

| TRUB2 | - | mRNA, tRNA, mt-tRNA (Mukhopadhyay 2021), mt-mRNA (Antonicka) | Mitochondria | - | - | [7,8,26,100, 101] | |

| DKC1 | snoRNA-guided | mRNA, rRNA, snoRNA, snRNA | Nucleus | - | Dyskeratosis congénita, HIV, hepatocellular carcinoma, cataracts and sensorineural deafness | [8,9,32,49,53,54] | |

| RPUSD2 | - | mRNA | Nucleus, mitochondria | - | - | [7,26,98] | |

| RPUSD3 | - | mRNA, mt-mRNA (Antonicka) | Nucleus, mitochondria | - | Hepatocellular carcinoma | [32,98,100] | |

| RPUSD4 | - | mRNA, mt-rRNA (Antonicka 2017) | Mitochondria, nucleus | Alternative splicing, alternative polyadenylation | Osteoarthritis | [7,50,100] | |

| m5U | TRMT2A | - | mRNA, tRNA | Nucleus, cytoplasm | - | Breast cancer | [4,98,102] |

| TRMT2B | - | mRNA, tRNA | Nucleus, nuclear bodies, mitochondria | - | Alzheimer’s disease | [103-105] | |

| D | DUS3L | GGGUCC | mRNA, tRNA | Nucleus, cytoplasm | Translation | Inflammatory bowel disease, cardiovascular disease | [4,98,106-108] |

Only mRNA, tRNA, rRNA, and snRNAs were considered as substrates, though other classes may also be modified by these writers.

Disease associations are linked to dysregulation of the writers, whether pseudouridines in mRNA targets contribute to disease phenotypes has not been determined.

Pseudouridine synthases

One major class of RNA-modifying enzymes consists of pseudouridine synthases (PUSs), which isomerize U to Ψ. There are two sub-classes of PUSs. The twelve synthases in the first category are standalone, directly recognizing sequence and/or structural features in the RNA (Table 1) [25]. This is in contrast to the second category comprised of one representative enzyme that serves as the catalytic subunit (DKC1) of a small nucleolar RNA-protein complexes (snoRNP) complex, which is assembled with individual Box H/ACA small nucleolar RNA (snoRNAs) that guide base-pairing around the target site [25]. Various knockout/knockdown and biochemical studies have identified TRUB1, DKC1, PUS1, and PUS7 as the PUSs responsible for the largest number of Ψs on mRNA [1,7,8,13,26]. Other PUSs also modify mRNA (Table 1).

Most PUSs localize to the nucleus or have nuclear isoforms, but there are also many that localize or have isoforms that localize to mitochondria (Table 1), where they modify mitochondrial RNAs, including mt-mRNAs [13,26-28]. The nuclear localization of most PUSs implies that modification occurs in the nucleus. Recent work uncovered the presence of Ψ in pre-mRNAs isolated from chromatin-associated RNA, specifically in introns, demonstrating that pseudouridylation occurs co-transcriptionally [7]. This early deposition endows this modification with the potential to affect nearly any step of mRNA processing, including splicing. PUS1, PUS7, and RPUSD4, for example, directly pseudouridylate hundreds of pre-mRNA sequences that are modified in cells [7]. While the exact mechanism of co-transcriptional modifications remains to be elucidated—along with the exact timing of their deposition relative to transcription and other pre-mRNA processing steps—many pre-mRNA processing steps are coupled to transcription through recruitment of pre-mRNA processing factors by the transcription machinery and interactions with chromatin [29]. PUS7 may be recruited by similar mechanisms, given that it acts on pre-mRNA [7] and is associated with histone marks present at active Poll II promoters and enhancers [30]. Such co-transcriptional addition of Ψ also suggests a capacity to modulate RNA:DNA hybrids that regulate transcription, as has been shown for m6A [31]. While Ψ can be added early to pre-mRNAs in the nucleus, re-localization of PUSs to the cytoplasm can also result in later-stage deposition, as evidenced by the gain of new pseudouridylation sites observed under heat-shock conditions [1,5]. Future studies mapping Ψ across subcellular compartments could shed light on the dynamics of uridine modifications throughout the lifecycle of mRNAs.

Diseases associated with pseudouridine synthases

PUSs have been associated with a wide-range of human diseases including cancer [32-36], neurodevelopmental disorders [37,38,47,39-46], degenerative disorders [48-50], autoimmune disorders [51,52], viral infection [53], and others. For example, mutations in DKC1 lead to dyskeratosis congenita, which is likely due to its telomere function as mutations in the telomerase complex also lead to disease [54]. However, mutations that disrupt catalytic activity are associated with disease severity suggesting that the contribution of RNA pseudouridylation warrants investigation. Mutations in PUS1 cause myopathy-lactic acidosis-sideroblastic anemia [55-58], a mitochondrial disease. Patient cells have revealed mitochondrial translation defects [56] consistent with the presence of a PUS1-mitochondrial isoform that modifies mitochondrial tRNAs and mRNAs [8,9]. Mutations in PUS3 [37-42] or PUS7 that are predicted to be loss of function [43-47] lead to neurodevelopmental disorders presenting with microcephaly and intellectual disabilities. High expression of PUS7 is elevated in glioblastoma and its catalytic activity is required for tumorigenesis, supporting that Ψ in RNA targets contribute to cancer phenotypes [34]. The molecular mechanisms behind these disease phenotypes are not understood. Whether the RNA modifications these enzymes catalyze, in mRNA or other RNAs, are causative of disease remains to be elucidated.

Regulation of mRNA pseudouridylation

Different cell lines and tissue types exhibit differential expression of PUSs [7,25] and distributions of Ψ, with some Ψs conserved across tissues and cell lines while others are unique to a specific tissue or cell [1,8]. Analyses in mice, for example, revealed varying amounts and stoichiometries of Ψ across different tissue types, with a majority of identified sites being tissue-specific (highest in the cerebellum) [1,8]. Ψ distributions are also altered by various stressors - such as heat shock [28], serum starvation [6], and hydrogen peroxide treatment [1]. For example, yeast PUS7 re-localizes to the cytoplasm following heat shock, where it gains new targets [5]. Furthermore, in human cells upon interferon stimulation, Ψ becomes more prevalent in genes related to the interferon pathway and anti-viral response, such as ISG15 [21]. Other environmental factors and stimuli could also influence the Ψ landscape beyond the examples mentioned here. Thus, the mechanisms by which Ψ deposition is regulated to control gene expression in response to changing conditions is an area open for investigation.

Functions of pseudouridines in mRNA

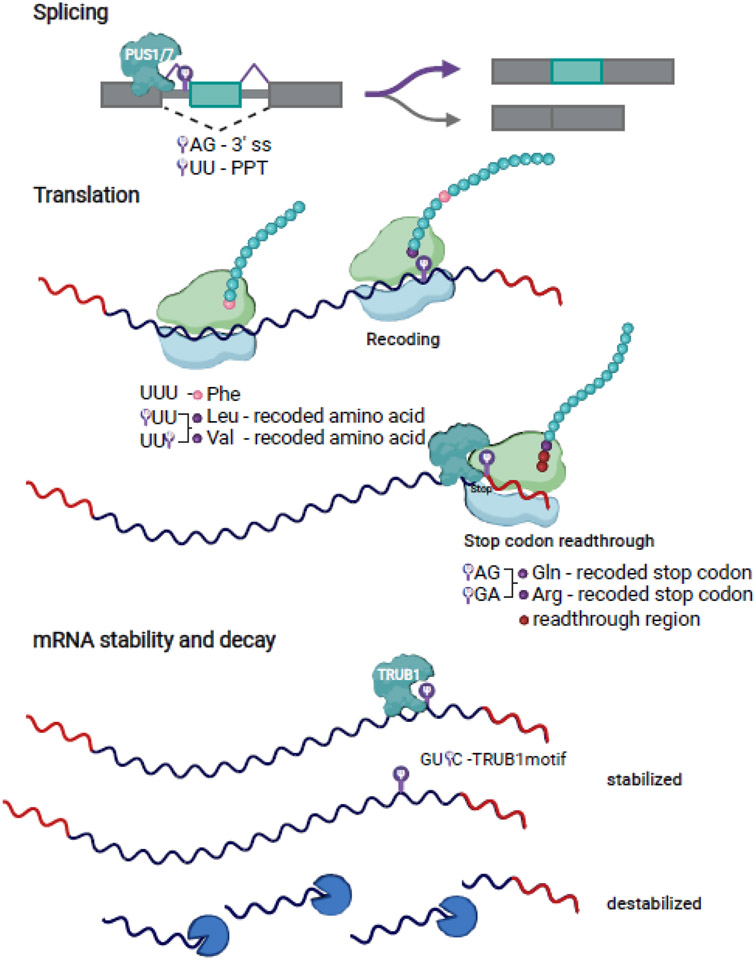

The prevalence of Ψs in mRNA, reproduced by multiple groups using orthogonal methods [7-9,13], and the high stoichiometry of Ψs [8] in many mRNAs supports their functional significance. Consistently, PUSs have been associated with a wide range of human diseases that might be in part mediated by mRNA targets (Table 1). Most studies have focused on three potential areas where uridine modifications could influence gene expression: splicing, translation, and mRNA stability (Figure 2). These could be mediated through the known molecular effects of Ψ on RNA-protein and RNA structure (discussed below). Most functional studies have been performed using genetic manipulation of the writers that result in global perturbations and in vitro biochemical approaches, leaving a gap in establishing the causality of individual modifications in the context of their endogenous functions within cells. Here we discuss the functions and potential functions of uridine modifications in mRNAs.

Figure 2. Functions of pseudouridines in mRNAs.

Emerging evidence suggests that Ψ may function in mRNA processing and mRNA metabolism. Ψ in pre-mRNAs are added by pre-mRNA pseudouridine synthases such as PUS1 and PUS7. Pseudouridines are enriched within splice sites including the 3’ splice site (3’ ss) and the polypyrimidine tract (PPT), and can impact alternative splicing outcomes. Ψ in coding sequences, at the 1st or 3rd position in Phe codons can impact translation fidelity leading to recoding to amino acids Leu and Val. Ψ in UAG and UGA stop codons leads to stop codon readthrough and misincorporation of Gln and Arg. PUS1 has been shown to pseudouridylate a stop codon. TRUB1-dependent Ψs (in the context of the TRUB1 motif GUΨC) in mRNAs have been shown to stabilize mRNAs and loss of Ψ leads to destabilization. Future work investigating direct effects of individual modifications in mRNAs in cells and providing mechanistic insight are needed to clarify direct versus indirect functions of uridine modifications in mRNA and to reveal the extent to which mRNA modifications are used for gene regulation.

Impacts of pseudouridine on RNA-protein interactions

Due to the chemical differences between U and Ψ, it is likely that Ψs affect the binding affinities of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) for RNA either directly or indirectly through effects on RNA structure (Table 2). For some modifications, such as m6A, there are dedicated modification readers that specifically accommodate the methyl group [59]. Ψs might not have dedicated readers, but canonical RBPs/domains could bind with higher or lower affinity depending on the modifications. To our knowledge, endogenous readers of Ψs in mRNAs remain to be discovered in mammals. However, there are examples of altered protein-RNA interactions with Ψ.

Table 2.

Pseudouridine-sensitive RNA-protein interactions.

| Pseudouridine-sensitive protein-RNA interactions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Level of Evidence | Effects | Hypothesized Function of Ψ |

References |

| RNase L | Fully Ψ-substituteda exogenous mRNA delivered to mammalian cells | - | Prevent RNA degradation | [60] |

| RNase E | Artificialb single Ψ in vitro | - | Prevent RNA degradation | [61] |

| PRP5 | Ψ removal by writer enzyme deletion in yeast | Ψ increased binding presumably through structure effects | Spliceosome assembly | [69] |

| MetRS | In vitro oligo binding assay and in vivo Ψ-to-C mutation in yeast | Ψ increased binding | Translation | [64] |

| U2AF2 | Artificial substitution of Ψ at specific locations of polypyrimidine tract in vitro | Ψ decreased binding due to rigidification of backbone | Splice site recognition | [65] |

| MBNL1 | Artificial addition of Ψ in binding site in vitro[67] | Ψ decreased binding due to rigidification of backbone | - | [67] |

| PUM2 | Artificial addition of Ψ in binding site in vitro[68] | Ψ decreased binding | - | [68] |

| RIG-I | Fully Ψ substituted RNA in vitro | Ψ increased binding and suppressed filament formation[62,63] | Prevent innate immune activation | [62,63] |

Fully Ψ-substituted = 100% of U’s replaced with Ψ during in vitro transcription.

Artificial Ψ = Ψ has not been demonstrated to exist in endogenous contexts, but site-specific and 100% modified at that location.

For example, a fully Ψ substituted synthetic mRNA showed reduced degradation by RNase L in mammalian cells [60]. Similarly, the presence of a single Ψ abrogated cleavage by E. coli RNase E in vitro [61]. These results suggest that RNases are sensitive to the presence of Ψ, possibly through altered backbone geometry. It remains to be determined whether protection from ribonucleases is a mechanism by which Ψs mediate observed impacts of Ψ on mRNA turnover8. Ψs have also been shown to prevent activation of foreign nucleic acid sensors and to dampen innate immune responses, implicating RNA sensors as Ψ readers. For example, unmodified, but not Ψ-containing RNAs activate the cytosolic innate immune receptor RIG-I [62,63]. The presence of psedorudine directlyaffects RIG-I filament formation in vitro [63]. Further, binding of yeast methionine aminoacyl tRNAMet synthetase MetRS was enriched around mRNA regions with Ψ in yeast. Biochemical experiments showed that MetRS binds better to Ψ-containing RNA than an unmodified control, and a Ψ-to-C mutation in an endogenous mRNA reduces MetRS binding, providing evidence that MetRS functions as a Ψ reader in mRNA [64]. Individual Ψs artificially introduced at specific positions in the polypyrimidine tract of a pre-mRNA inhibited the binding of U2AF2 due to rigidification of the RNA backbone [65]. Similarly, Ψs reduced the binding of Sm to the U7 snRNA [66], of the splicing factor MBNL1 to Ψ-containing expansion repeats [67], and of PUM2 to RNAs containing its motif in vitro [68].

Ψs also alter the binding of RBPs through effects on RNA structure. One example of this is yeast RNA helicase Prp5 which was found to bind less to U2 snRNAs in the absence of two Ψs in the U2 snRNA, due to Ψ-mediated alterations of the structure in the branch site recognition region [69]. While none of these studies explore the effects of endogenous Ψs in mammalian systems, they demonstrate that a single Ψ can impact RNA structure and RBP binding. An immediate area of interest is the identification of endogenous readers of Ψs that mediate their effects on mRNA metabolism.

Impact of pseudouridine on RNA structure

Studies on the effect of Ψ on mRNA structure are lacking, but studies of other RNA species inform potential functions. While the canonical U favors the C-2′-endo sugar structure, Ψ favors a C-3′-endo sugar structure due to hydrogen bonding with its own phosphate backbone. This altered structure adds rigidity to the backbone and base and stabilizes RNA duplexes [59]. These structural changes have been shown to improve thermodynamic stability of Ψ-A pairing compared to the canonical U-A pairing [70] in a context dependent nature [71]. Additionally, Ψ has been shown to improve base stacking in several different contexts, which contributes to the increased stability of RNA duplexes by 1-2 kcal/mol [72,73]. However, if positioned in the loop of a stem-loop, Ψs destabilize the stem [74]. Recent in vitro work on a riboswitch found in the 5′UTR of a bacterial mRNA showed that the effects of Ψ on structural stability can also be context dependent. Ψs at some positions were locally destabilizing while globally stabilizing at others [75], indicating the various potential context-dependent effects of Ψ on RNA structure. Ψ in the U2 snRNA stabilizes U2 snRNA-pre-mRNA pairing in vitro in certain branch site contexts [65]. Additionally, stress inducible Ψs in U2 snRNA shift the equilibrium between alternate conformations of the U2 snRNA that are formed during splicing.

Ψ can stabilize, destabilize, and alter structural equilibrium in vitro, which could in turn impact RNA-protein interactions and mRNA processing. How Ψs impact mRNA structure in cells and how they might in turn impact mRNA metabolism remains to be determined. Chemical structure probing of unmodified and modified mRNAs in cells would be a first step.

Pre-mRNA processing

One other frontier in the functions of uridine modifications in mRNA is their effect on pre-mRNA processing. This area has been understudied because most research has been done on polyA-selected mRNAs that have already been fully processed. Recent work examined chromatin-associated RNA that is enriched in nascent pre-mRNAs, which are tethered to chromatin via association with Pol II from human cell lines, to identify Ψs in pre-mRNAs [7]. The majority of Ψs were found in intronic regions, with enrichment of Ψs in introns of alternatively spliced regions. Ψs were enriched within splice sites, in proximal introns, and in the binding sites of many RBPs that include splicing factors, demonstrating that Ψs are in regions known to influence splicing.

Splicing reporter experiments have shown that artificial pseudouridylation [65] and endogenous Ψs identified in cells [7] directly impact splicing in nuclear extracts where site specific modification in the absence of genetic perturbation is possible. For example, a Ψ upstream of the 3′ splice site increased splicing efficiency of an RBM39 reporter minigene. Artificial pseudouridylation of either of 2 positions, but not other positions, of a model pre-mRNA polypyrimidine tract substrate inhibited splicing [65]. This was explained by loss of U2AF2 binding due to rigidifying effects of Ψ on the RNA backbone. In cells, knockdown of PUS1, PUS7, and RPUSD4 leads to widespread alternative splicing and 3′ end processing [7]. These results suggest that pseudouridylation broadly influences pre-mRNA processing, including splicing and 3′ end processing. Alternative splicing changes in both directions, increased exon inclusion and skipping, are observed following PUS depletion. This is consistent with Ψs residing in the binding sites of splicing repressors and enhancers. Mechanistic dissection of the molecular effects of individual Ψs will allow context-dependent effects to be deciphered. Whether Ψs directly impact 3′ end processing and lead to alternative cleavage and polyadenylation remains an outstanding question. Ψ profiling is limited to the most highly expressed genes, hindering comprehensive quantification of Ψ at all positions surrounding alternative pre-mRNA processing events. Future work using enrichment strategies and/or targeted Ψ profiling of nascent RNAs along with synthetic standards will allow relating pseudouridylation stoichiometry to differences in inclusion of alternatively spliced regions.

Ψs alter the structure of RNA and impact RNA-RNA or RNA-protein interactions, which could explain the effects of Ψs on pre-mRNA processing. For example, Ψs could stabilize RNA-RNA interactions between the snRNAs and pre-mRNA splice sites harboring Ψs. Ψs could also directly or indirectly (through structure), alter the binding affinity of splicing factors to pre-mRNAs. Multiple splicing factors were found to be enriched for having Ψ within their binding sites [7], raising the possibility that Ψ could directly affect their binding. Consistent with these mechanistic hypotheses, Ψ are known to impact RNA structure and RNA-protein interactions (see above).

Translation

Uridine modifications could impact translation efficiency or change how the ribosome interprets the codon, or lead to misincorporation of amino acids, thus impacting translation fidelity [76]. Fully substituted exogenously delivered mRNAs are in some cases more efficiently translated than the unmodified versions [60,77]. Reconstituted in vitro systems have found that introducing Ψs in phenylalanine codons (UUU), a frequently Ψ-modified codon [1], modestly slows dipeptide synthesis [78] and decreases the yield of full-length peptides [79,80]. These results contrast with enhanced translation observed in vivo with fully substituted therapeutic mRNAs. These differences could be due to the fully modified versus site specifically modified mRNAs and/or additional translational control mechanisms in the in vivo context not captured in the minimal in vitro systems.

Ψs also leads to recoding of phenylalanine to leucine or valine in a context-dependent manner. Ψ at the first and third positions results in amino acid misincorporation 25% of the time in the in vitro system [81]. The effects of misincorporation are both dependent on the position of the modified bases and the identity of the opposing tRNA, with some combinations causing fold changes in rate constants while others have no effect [78]. Assays in cells have been limited to the use of fully modified reporters, tracking amino acid misincorporation through mass spectrometry analysis of a peptide product. Fully Ψ-modified reporters in HEK cells were observed to have ~1% of amino acids substituted [81]. More work is required to understand if and how single modifications would affect translation of endogenous mRNA in cells, but these results indicate that Ψs can have a biochemical impact on translational fidelity. Whether these mechanisms might be more prevalent under stress or in limiting tRNA conditions is of particular interest.

Artificial pseudouridylation of stop codons using designed snoRNAs (Figure 1D) demonstrates that Ψ-containing stop codons can be read through resulting in production of longer protein products in yeast (Figure 2) [82]. Recently, artificial pseudouridylation of diseaserelevant premature termination codons showed read-through and recovery of full-length protein at low levels (~5-15% of wild-type) in mammalian cells [83,84]. While the rate of stop codon read-through was not found to vary between UAG, UAA, and UGA or as a result of perturbing surrounding sequences in yeast [85], the mammalian UAA was found to be modified at lower levels [83]. Comprehensive examination of sequence contexts will be necessary before general principles about the effect of Ψs on stop codon read-through can be determined. Whether Ψs existed at endogenous stop codons remained unclear until a handful of pseudouridylated codons in human cell lines were identified by bisulfite-based Ψ detection [8]. A stop codon in NDUFS2 is pseudouridylated by PUS1. Knockdown of PUS1 decreased stop codon readthrough, suggesting that Ψ could promote readthrough at endogenously modified stop codons [8]. In contrast many more (106) pseudouridylated stop codons were identified in mRNAs from mouse tissues, all with a downstream unmodified stop codon, indicating more potential examples of endogenous stop codon read-through mediated by pseudouridylation [8]. Analysis of the protein products of a subset of these mRNA revealed longer protein isoforms indicating potential read-through, in some but not all cases, occurring in a tissue-specific manner [8]. The stoichiometry of modification relative to read-through also appears to be context dependent, indicating additional mechanisms may regulate Ψ-mediated stop codon read-through.

Two crystal structures of the ribosome with a pseudouridylated codon have been solved [81,86], providing mechanistic insights into the effects of Ψ on translational fidelity. A ΨAA stop codon in complex with a bacterial ribosome did not alter the structure or kinetics of peptide release [81,86], consistent with Ψ at stop codons impacting decoding by near-cognate tRNA rather than release. A ΨUU phenylalanine codon in complex with a bacterial ribosome displayed increased flexibility at the amino acid binding end (CAA-end) of the tRNA, a region not examined in the ΨAA structure, and slower GTP hydrolysis with EF-Tu [81]. Overall, this supports a model where multiple subtle differences combine to cause amino acid misincorporation.

mRNA Stability

Biochemical experiments with modified and unmodified RNA and experiments following depletion of PUS in cells suggest a role for Ψ in mRNA stability. Early work on synthetic mRNAs found that fully pseudouridylated RNA in cells outlived unmodified RNA by several hours due to less efficient activation of 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase 1 (OAS) and RNase L degradation [60]. Biochemical studies have also shown that Ψs prevent cleavage by RNase E in vitro [61], suggesting the Ψs might protect RNAs from degradation by cellular ribonucleases. PUS7 mRNA targets in yeast decrease in abundance following PUS7 deletion, supporting a stabilizing role of Ψs in mRNA [5]. However, whether this is due to directly affecting mRNA turnover was not investigated.

More recently, TRUB1 mRNA targets were found to have shorter half-lives upon TRUB1 depletion, showing that TRUB1 leads to stabilization of mRNAs that it pseudouridylates [8]. Further work attempted to directly attribute the stabilizing effect to a single Ψ within a handful of TRUB1-stabilized mRNAs. Targeting TRUB1 to the modification site with dCas-13d to induce site specific modification increased the lifespan of the mRNAs [8], indicating that either tethering TRUB1 or the Ψ it generates modulates mRNA lifespan. Another study did not observe a global difference in the abundance of TRUB1 mRNA targets following knockdown [9]. However, differences in knockdown efficiencies might explain this discrepancy.

In contrast to stabilizing effects of PUS observed in the cases above, mRNAs containing Ψs dependent on the pseudouridines synthase TgPUS1 are modestly stabilized in TgPUS1 mutant trypanosomes, indicating that Ψs could destabilize mRNAs in some contexts [87]. Future work will be required to determine the impact of Ψs on mRNA stability in different sequence and structural contexts and to delineate positional outcomes due to the location of pseudouridines within mRNAs. The underlying mechanisms mediating PUS-dependent mRNA stability changes, and whether PUS or the Ψs they install alter recruitment of the degradation machinery is open for investigation.

Tools to interrogate direct versus indirect effects of pseudouridinylation

Most studies of uridine modifications have been limited to chronic global perturbation of RNA-modifying enzymes that have hundreds of target sites among different classes of RNAs, including tRNAs. Tools for targeted addition, site-specific blocking, or removal of uridine modifications are highly desirable to allow to interrogate the effects of individual modifications and establish causality between modifications and observed phenotypes resulting from knockdown or knockout of the writers. Recently, as noted above, TRUB1 was fused to dCas-13 to use CRISPR guide RNAs to direct the PUS to the region of modification (Figure 1E) [8].

Two recent studies used engineered H/ACA box snoRNAs to introduce site specific Ψs at premature termination codons (PTC) [83,84]. In contrast to the CRISPR/PUS fusions where the features recognized by the particular enzyme are still needed and thus would only work for targets of that enzyme, the snoRNA-guided approach is in principle entirely programable to direct pseudouridylation at any location. However, pseudouridylation efficiency is limited and context dependent. DKC1, the catalytic subunit of snoRNPs, primarily localizes to the nucleolus and Cajal bodies where canonical rRNA and snRNA targets reside. Overexpression of a cytoplasmic isoform of the DKC1 that overcomes the limited access of DKC1 to mRNAs improves modification efficiency several-fold. One potential caveat to these kinds of experiments is that tethering a large RNP to the target regions might impact mRNA metabolism independent of introducing the modification (e.g., through steric blocking of regulatory elements). Inclusion of a catalytic null mutant enzyme and evaluation of the release kinetics of RNPs after modification will be important to interpret outcomes, to ensure this approach does not confound interpretation of results.

Concluding Remarks

Technological innovation will continue to advance the studies of Ψ, including determining their location, stoichiometry, and the mRNA isoforms that harbor them in a variety of cellular contexts. Multiple disease-associated PUSs modify mRNAs that could contribute to disease etiology, and Ψs are tissue-specific and can change in response to environmental cues, implying tuned regulation remains to be explored. Further, Ψ can affect pre-mRNA processing, translation, and mRNA stability in context-specific manners. Mechanistically, these effects could be mediated through Ψ-dependent differences in RNA structure and RNA-protein interactions. Reader proteins that could mediate these effects in endogenous contexts remain to be determined, though several examples of RBPs with Ψ-sensitive binding are documented. Future studies and technologies for interrogating the direct biochemical effects of individual modifications will allow attributing changes in mRNA metabolism upon manipulation of RNA modifying enzymes to pseudouridylation of mRNAs (see Outstanding questions). Evaluation of the interplay of pseudouridine with other uridine modifications may facilitate cracking the regulatory logic of uridine modifications in gene expression (Box 2).

Outstanding Questions.

Do pseudouridines in mRNA contribute to disease phenotypes associated with dysregulation of writers?

How is deposition of pseudouridine regulated, under normal conditions and in response to environmental cues?

What are the mechanisms by which pseudouridines mediate their functional effects on pre-mRNA processing, translation and mRNA stability?

Are there readers of pseudouridine and do pseudouridines alter mRNA structure in cells?

How does sequence context affect the function of pseudouridines?

How can new technologies, such as site-specific pseudouridylation, be leveraged to determine the direct endogenous functions of these modifications?

Will new technologies, such as direct RNA sequencing, allow identification of multiple uridine modifications, report on stoichiometry, and retain location information in full length mRNAs?

Do uridine modifications work in concert or exert feedback on each other?

Figure I.

Structures of modified uridines.

Highlights.

mRNA modifications impact the mRNA lifecycle.

Pseudouridine is the most prevalent of the uridine modifications in mRNA.

There have been recent developments in technologies to quantify and to study the functions of pseudouridine, particularly in mRNA.

Functions of pseudouridines in mRNA have been uncovered in splicing, translation and stability.

The presence and regulation of uridine modifications in mRNA urge future studies into their functions.

Glossary

- BID-Seq

Quantitative pseudouridine sequencing method using bisulfite chemical labeling at pH 7 (optimized bisulfite reaction conditions from RBS-Seq to drive reactivity with Ψ to completion and minimize reactivity with cytidine). Resulting bisulfite-Ψ adducts induce deletions during reverse transcription identified from Illumina Sequencing. Applied to mRNA in HeLa (575 sites), HEK293T (543 sites) and A549 cells (922 sites) along with mouse tissue samples (508-6617 sites depending on tissue).

- CeU-Seq

Pseudouridine sequencing method using CMC with N3 handle to label and enable enrichment via click chemistry prior to identification by RT stops from Illumina Sequencing. Applied to mRNA in HEK293T cells (2084 sites).

- D-seq

Identification of dihydrouridine sites after NaBH4 chemical labeling identified by RT stops. Applied to mRNA in yeast (130 sites).

- Illumina Sequencing

Technology for indirect sequencing of RNA from cDNA, generating short-reads, that is the readout for several RNA modification sequencing methods.

- Long read RNA nanopore sequencing

Technology that allows direct sequencing of full-length RNAs by threading RNA through a Nanopore with an applied current. As each nucleoside passes through the Nanopore they disrupt the ionic current and display different dwell times in the Nanopore channel. Modified versus unmodified nucleosides can be distinguished by differences in ionic current, dwell time and base calling errors.

- PRAISE

Quantitative pseudouridine sequencing method using bisulfite chemical labeling at pH 5.1 with increased bisulfite molar ratio (optimized bisulfite reaction conditions from RBS-Seq to drive reactivity with Ψ to completion and minimize reactivity with cytidine), which induce deletions during reverse transcription identified from Illumina Sequencing. Applied to mRNA in HEK293T cells (2209 sites).

- Pseudo-Seq Ψ-Seq

Pseudouridine sequencing method that uses derivatization of pseudouridines with CMC followed by identification by RT stops from Illumina Sequencing. Applied to mRNA in yeast (41 sites) and HeLa cells (96 sites) and pre-mRNA in HepG2 cells (1316 exonic sites and 2088 intronic sites).

- RBS-Seq

Pseudouridine sequencing method using bisulfite chemical labeling at pH 5 which induces deletions during reverse transcription identified from Illumina Sequencing. Applied to mRNA in HeLa cells (322 sites).

- Rho-seq

Identification of dihydrouridine sites after two step reaction resulting in rhodamine chemical labeling identified by RT stops. Applied to mRNA in fission yeast (143 sites) and HCT116 cells (112 sites).

- RNABPP

RNA-mediated activity-based protein profiling (RNABPP) to probe methyl transferases (i.e. TRMT2A) and dihydrouridine synthases (i.e. DUS3L) by incubation with 5-fluoropyrmidines to crosslink RNA substrates to RNA modifying enzymes. Applied to mRNA in HEK293T cells (80 D sites).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Li X. et al. (2015) Chemical pulldown reveals dynamic pseudouridylation of the mammalian transcriptome. Nat. Chem. Biol 11, 592–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng QY et al. (2020) Chemical tagging for sensitive determination of uridine modifications in RNA. Chem. Sci 11, 1878–1891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones JD et al. (2023) Methylated guanosine and uridine modifications in S. cerevisiae mRNAs modulate translation elongation. RSC Chem. Biol 4, 363–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dai W. et al. (2021) Activity-based RNA-modifying enzyme probing reveals DUS3L-mediated dihydrouridylation. Nat. Chem. Biol 17, 1178–1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz S. et al. (2014) Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals widespread dynamic-regulated pseudouridylation of ncRNA and mRNA. Cell 159, 148–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlile TM et al. (2014) Pseudouridine profiling reveals regulated mRNA pseudouridylation in yeast and human cells. Nature 515, 143–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez NM et al. (2022) Pseudouridine synthases modify human pre-mRNA co-transcriptionally and affect pre-mRNA processing. Mol. Cell 82, 645–659.e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dai Q. et al. (2022) Quantitative sequencing using BID-seq uncovers abundant pseudouridines in mammalian mRNA at base resolution. Nat. Biotechnol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang M. et al. (2023) Quantitative profiling of pseudouridylation landscape in the human transcriptome. Nat. Chem. Biol DOI: 10.1038/s41589-023-01304-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marchand V. et al. (2020) HydraPsiSeq: A method for systematic and quantitative mapping of pseudouridines in RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang W. et al. (2019) Sensitive and quantitative probing of pseudouridine modification in mRNA and long noncoding RNA. Rna 25, 1218–1225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lei Z and Yi C (2017) A Radiolabeling-Free, qPCR-Based Method for Locus-Specific Pseudouridine Detection. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 56, 14878–14882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Safra M. et al. (2017) TRUB1 is the predominant pseudouridine synthase acting on mammalian mRNA via a predictable and conserved code. Genome Res. 27, 393–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tavakoli S. et al. (2023) Semi-quantitative detection of pseudouridine modifications and type I/II hypermodifications in human mRNAs using direct long-read sequencing. Nat. Commun 14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lovejoy AF et al. (2014) Transcriptome-wide mapping of pseudouridines: Pseudouridine synthases modify specific mRNAs in S. cerevisiae. PLoS One 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khoddami V. et al. (2019) Transcriptome-wide profiling of multiple RNA modifications simultaneously at single-base resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 116, 6784–6789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Campos MA et al. (2019) Deciphering the “m6A Code” via Antibody-Independent Quantitative Profiling. Cell 178, 731–747.e16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu L. et al. (2022) m6A RNA modifications are measured at single-base resolution across the mammalian transcriptome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022 408 40, 1210–1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleming AM et al. (2021) Nanopore Dwell Time Analysis Permits Sequencing and Conformational Assignment of Pseudouridine in SARS-CoV-2. ACS Cent. Sci 7, 1707–1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Begik O. et al. (2021) Quantitative profiling of pseudouridylation dynamics in native RNAs with nanopore sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol 39, 1278–1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang S. et al. (2021) Interferon inducible pseudouridine modification in human mRNA by quantitative nanopore profiling. Genome Biol. 22, 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCormick C. et al. (2023) Multicellular, IVT-derived, unmodified human transcriptome for nanopore direct RNA analysis. bioRxiv [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassan D. et al. (2022) Penguin: A tool for predicting pseudouridine sites in direct RNA nanopore sequencing data. Methods 203, 478–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jalan A. et al. (2023) Decoding the ‘Fifth’ Nucleotide: Impact of RNA Pseudouridylation on Gene Expression and Human Disease. Mol. Biotechnol. DOI: 10.1007/s12033-023-00792-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borchardt EK et al. (2020) Regulation and Function of RNA Pseudouridylation in Human Cells. Annu. Rev. Genet 54, 309–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlile TM et al. (2019) mRNA structure determines modification by pseudouridine synthase 1. Nat. Chem. Biol 15, 966–974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guegueniat J. et al. (2021) The human pseudouridine synthase PUS7 recognizes RNA with an extended multi-domain binding surface. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 11810–11822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purchal MK et al. (2022) Pseudouridine synthase 7 is an opportunistic enzyme that binds and modifies substrates with diverse sequences and structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 119, 1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shenasa H and Bentley DL (2023) Pre-mRNA splicing and its cotranscriptional connections. Trends Genet. DOI: 10.1016/j.tig.2023.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ji X. et al. (2015) Chromatin proteomic profiling reveals novel proteins associated with histone-marked genomic regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112, 3841–3846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abakir A. et al. (2020) N 6-methyladenosine regulates the stability of RNA:DNA hybrids in human cells. Nat. Genet 52, 48–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin Z. et al. (2022) Integrative multiomics evaluation reveals the importance of pseudouridine synthases in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Genet 13, 1–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guzzi N. et al. (2018) Pseudouridylation of tRNA-Derived Fragments Steers Translational Control in Stem Cells. Cell 173, 1204–1216.e26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cui Q. et al. (2021) Targeting PUS7 suppresses tRNA pseudouridylation and glioblastoma tumorigenesis. Nat. Cancer 2, 932–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Q. et al. (2023) PUS7 promotes the proliferation of colorectal cancer cells by directly stabilizing SIRT1 to activate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Mol. Carcinog 62, 160–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song D. et al. (2021) HSP90-dependent PUS7 overexpression facilitates the metastasis of colorectal cancer cells by regulating LASP1 abundance. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res 40, 170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin TY et al. (2022) Destabilization of mutated human PUS3 protein causes intellectual disability. Hum. Mutat 43, 2063–2078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borghesi A. et al. (2022) PUS3-related disorder: Report of a novel patient and delineation of the phenotypic spectrum. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 188, 635–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nøstvik M. et al. (2021) Clinical and molecular delineation of PUS3-associated neurodevelopmental disorders. Clin. Genet 100, 628–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Paiva ARB et al. (2019) PUS3 mutations are associated with intellectual disability, leukoencephalopathy, and nephropathy. Neurol. Genet 5, 1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abdelrahman HA et al. (2018) A null variant in PUS3 confirms its involvement in intellectual disability and further delineates the associated neurodevelopmental disease. Clin. Genet. 94, 586–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Froukh T. et al. (2020) Genetic basis of neurodevelopmental disorders in 103 Jordanian families. Clin. Genet 97, 621–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Darvish H. et al. (2019) A novel PUS7 mutation causes intellectual disability with autistic and aggressive behaviors. Neurol. Genet 5, 1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han ST et al. (2022) PUS7 deficiency in human patients causes profound neurodevelopmental phenotype by dysregulating protein translation. Mol. Genet. Metab 135, 221–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Naseer MI et al. (2020) Next generation sequencing reveals novel homozygous frameshift in PUS7 and splice acceptor variants in AASS gene leading to intellectual disability, developmental delay, dysmorphic feature and microcephaly. Saudi J. Biol. Sci 27, 3125–3131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Brouwer APM et al. (2018) Variants in PUS7 Cause Intellectual Disability with Speech Delay, Microcephaly, Short Stature, and Aggressive Behavior. Am. J. Hum. Genet 103, 1045–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shaheen R. et al. (2019) PUS7 mutations impair pseudouridylation in humans and cause intellectual disability and microcephaly. Hum. Genet 138, 231–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ratnapriya R. et al. (2021) Family-based exome sequencing identifies rare coding variants in age-related macular degeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet 29, 2022–2034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Balogha E. et al. (2020) Pseudouridylation defect due to DKC1 and NOP10 mutations causes nephrotic syndrome with cataracts, hearing impairment, and enterocolitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 117, 15137–15147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen Z. et al. (2023) Expression patterns of eight RNA-modified regulators correlating with immune infiltrates during the progression of osteoarthritis. Front. Immunol 14, 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Medrano LM et al. (2019) Expression patterns common and unique to ulcerative colitis and celiac disease. Ann. Hum. Genet 83, 86–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Festen EAM et al. (2011) A meta-analysis of genome-wide association scans identifies IL18RAP, PTPN2, TAGAP, and PUS10 as shared risk loci for crohn’s disease and celiac disease. PLoS Genet. 7, 3–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao Y. et al. (2016) Pseudouridylation of 7SK snRNA promotes 7SK snRNP formation to suppress HIV-1 transcription and escape from latency. EMBO Rep. 17, 1441–1451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.AlSabbagh MM (2020) Dyskeratosis congenita: a literature review. JDDG - J. Ger. Soc. Dermatology 18, 943–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cao M. et al. (2016) Clinical and molecular study in a long-surviving patient with MLASA syndrome due to novel PUS1 mutations. Neurogenetics 17, 65–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fernandez-Vizarra E et al. (2007) Nonsense mutation in pseudouridylate synthase 1 (PUS1) in two brothers affected by myopathy, lactic acidosis and sideroblastic anaemia (MLASA). J. Med. Genet 44, 173–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kasapkara ÇS et al. (2017) A myopathy, lactic acidosis, sideroblastic anemia (MLASA) case due to a novel PUS1 mutation. Turkish J. Hematol 34, 376–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oncul U. et al. (2021) A Novel PUS1 Mutation in 2 Siblings with MLASA Syndrome: A Review of the Literature. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol 43, E592–E595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sipa K. et al. (2007) Effect of base modifications on structure, thermodynamic stability, and gene silencing activity of short interfering RNA. Rna 13, 1301–1316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anderson BR et al. (2011) Nucleoside modifications in RNA limit activation of 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase and increase resistance to cleavage by RNase L. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 9329–9338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Islam MS et al. (2021) Impact of pseudouridylation, substrate fold, and degradosome organization on the endonuclease activity of RNase E. RNA 27, 1339–1352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Durbin AF et al. (2016) RNAs containing modified nucleotides fail to trigger RIG-I conformational changes for innate immune signaling. MBio 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peisley A. et al. (2013) RIG-I Forms Signaling-Competent Filaments in an ATP-Dependent, Ubiquitin-Independent Manner. Mol. Cell 51, 573–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levi O and Arava YS (2021) Pseudouridine-mediated translation control of mRNA by methionine aminoacyl tRNA synthetase. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 432–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen C. et al. (2010) A Flexible RNA Backbone within the Polypyrimidine Tract Is Required for U2AF 65 Binding and Pre-mRNA Splicing In Vivo . Mol. Cell. Biol 30, 4108–4119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kolev NG and Steitz JA (2006) In vivo assembly of functional U7 snRNP requires RNA backbone flexibility within the Sm-binding site. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 13, 347–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.deLorimier E et al. (2017) Pseudouridine Modification Inhibits Muscleblind-like 1 (MBNL1) Binding to CCUG Repeats and Minimally Structured RNA through Reduced RNA Flexibility. J. Biol. Chem 292, 4350–4357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vaidyanathan PP et al. (2017) Pseudouridine and N6-methyladenosine modifications weaken PUF protein/RNA interactions. Rna 23, 611–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu G. et al. (2016) Pseudouridines in U2 snRNA stimulate the ATPase activity of Prp5 during spliceosome assembly. EMBO J. 35, 654–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hudson GA et al. (2013) Thermodynamic contribution and nearest-neighbor parameters of pseudouridine-adenosine base pairs in oligoribonucleotides. Rna 19, 1474–1482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Deb I. et al. (2019) Computational and NMR studies of RNA duplexes with an internal pseudouridine-adenosine base pair. Sci. Rep 9, 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Davis DR (1995) Stabilization of RNA stacking by pseudouridine. Nucleic Acids Res. 23, 5020–5026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kierzek E. et al. (2014) The contribution of pseudouridine to stabilities and structure of RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Meroueh M. et al. (2000) Unique structural and stabilizing roles for the individual pseudouridine residues in the 1920 region of Escherichia coli 23S rRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 2075–2083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vögele J. et al. (2023) Structural and dynamic effects of pseudouridine modifications on noncanonical interactions in RNA. RNA 29, 790–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Franco MK and Koutmou KS (2022) Chemical modifications to mRNA nucleobases impact translation elongation and termination. Biophys. Chem 285, 106780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Anderson BR et al. (2010) Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA enhances translation by diminishing PKR activation. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 5884–5892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Monroe JG et al. (2022) N1-Methylpseudouridine and pseudouridine modifications modulate mRNA decoding during translation. bioRxiv at <https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.06.13.495988v1%0Ahttps://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.06.13.495988v1.abstract> [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hoernes TP et al. (2016) Nucleotide modifications within bacterial messenger RNAs regulate their translation and are able to rewire the genetic code. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 852–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hoernes TP et al. (2019) Eukaryotic translation elongation is modulated by single natural nucleotide derivatives in the coding sequences of mRNAs. Genes (Basel). 10, 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Eyler DE et al. (2019) Pseudouridinylation of mRNA coding sequences alters translation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 116, 23068–23074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Karijolich J and Yu YT (2011) Converting nonsense codons into sense codons by targeted pseudouridylation. Nature 474, 395–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Song J. et al. (2023) CRISPR-free, programmable RNA pseudouridylation to suppress premature termination codons. Mol. Cell 83, 139–155.e9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Adachi H. et al. (2023) Targeted pseudouridylation: An approach for suppressing nonsense mutations in disease genes. Mol. Cell 83, 637–651.e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Adachi H and Yu YT (2020) Pseudouridine-mediated stop codon readthrough in s. cerevisiae is sequence context–independent. Rna 26, 1247–1256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Svidritskiy E. et al. (2016) Structural Basis for Translation Termination on a Pseudouridylated Stop Codon. J. Mol. Biol 428, 2228–2236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nakamoto MA et al. (2017) MRNA pseudouridylation affects RNA metabolism in the parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Rna 23, 1834–1849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Emerson J and Sundaralingam M (1980) Structure of the potassium salt of the modified nucleotide dihydrouridine 3’-monophosphate hemihydrate: correlation between the base pucker and sugar pucker and models for metal interactions with ribonucleic acid loops. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem 36, 537–543 [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dalluge JJ et al. (1996) Conformational flexibility in RNA: The role of dihydrouridine. Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 1073–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Davanloo P. et al. (1979) Role of ribothymidine in the thermal stability of transfer RNA as monitored by proton magnetic resonance. Nucleic Acids Res 6, 1571–1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Draycott AS et al. (2022) Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals a diverse dihydrouridine landscape including mRNA. PLoS Biol. 20, 1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Finet O. et al. (2022) Transcription-wide mapping of dihydrouridine reveals that mRNA dihydrouridylation is required for meiotic chromosome segregation. Mol. Cell 82, 404–419.e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Carter JM et al. (2019) FICC-Seq: a method for enzyme-specified profiling of methyl-5-uridine in cellular RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, E113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Patton JR et al. (2005) Mitochondrial myopathy and sideroblastic anemia (MLASA): Missense mutation in the pseudouridine synthase 1 (PUS1) gene is associated with the loss of tRNA pseudouridylation. J. Biol. Chem 280, 19823–19828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tesarova M. et al. (2019) Sideroblastic anemia associated with multisystem mitochondrial disorders. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Woods J and Cederbaum S (2019) Myopathy, lactic acidosis and sideroblastic anemia 1 (MLASA1): A 25-year follow-up. Mol. Genet. Metab. Reports 21, 100517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Busch JD et al. (2019) MitoRibo-Tag Mice Provide a Tool for In Vivo Studies of Mitoribosome Composition. Cell Rep. 29, 1728–1738.e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Uhlén M. et al. (2015) Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science (80-.). 347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jia Z. et al. (2022) Human TRUB1 is a highly conserved pseudouridine synthase responsible for the formation of Ψ55 in mitochondrial tRNAAsn, tRNAGln, tRNAGluand tRNAPro. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 9368–9381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Antonicka H. et al. (2017) A pseudouridine synthase module is essential for mitochondrial protein synthesis and cell viability. EMBO Rep. 18, 28–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mukhopadhyay S. et al. (2021) Mammalian nuclear TRUB1, mitochondrial TRUB2, and cytoplasmic PUS10 produce conserved pseudouridine 55 in different sets of tRNA. DOI: 10.1261/rna [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hicks DG et al. (2010) The expression of TRMT2A, a novel cell cycle regulated protein, identifies a subset of breast cancer patients with HER2 over-expression that are at an increased risk of recurrence. BMC Cancer 10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Laptev I et al. (2020) Mouse Trmt2B protein is a dual specific mitochondrial metyltransferase responsible for m5U formation in both tRNA and rRNA. RNA Biol. 17, 441–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Powell CA and Minczuk M (2020) TRMT2B is responsible for both tRNA and rRNA m5U-methylation in human mitochondria. RNA Biol. 17, 451–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Liu W. et al. (2023) The Inflammatory Gene PYCARD of the Entorhinal Cortex as an Early Diagnostic Target for Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomedicines 11, 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Park YM et al. (2020) Host genetic and gut microbial signatures in familial inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol 11, 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhang B. et al. (2021) Identification of key gene modules and pathways of human platelet transcriptome in acute myocardial infarction patients through co-expression network. Am. J. Transl. Res 13, 3890–3905 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhang Y. et al. (2022) Integrative analysis of transcriptome-wide association study and mRNA expression profile identified candidate genes and pathways associated with aortic aneurysm and dissection. Gene 808, 145993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]