Abstract

In the pursuit of finding efficient D-π-A organic dyes as photosensitizers for dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs), first-principles calculations of guanidine-based dyes [A1–A18] were executed using density functional theory (DFT). The various electronic and optical properties of guanidine-based organic dyes with different D-π-A structural modifications were investigated. The structural modification of guanidine-based dyes largely affects the properties of molecules, such as excitation energies, the oscillator strength dipole moment, the transition dipole moment, and light-harvesting efficiencies. The energy gap between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) is responsible for the reduction and injection of electrons. Modification of the guanidine subunit by different structural modifications gave a range of HOMO–LUMO energy gaps. Chemical and optical characteristics of the dyes indicated prominent charge transfer and light-harvesting efficiencies. The wide electronic absorption spectra of these guanidine-based dyes computed by TD-DFT-B3LYP with 6-31G, 6-311G, and cc-PVDZ basis sets have been observed in the visible region of spectra due to the presence of chromophore groups of dye molecules. Better anchorage of dyes to the surface of TiO2 semiconductors helps in charge-transfer phenomena, and the results suggested that −COOH, −CN, and −NO2 proved to be proficient anchoring groups, making dyes very encouraging candidates for DSSCs. Molecular electrostatic potential explained the electrostatic potential of organic dyes, and IR spectrum and conformational analyses ensured the suitability of organic dyes for the fabrication of DSSCs.

1. Introduction

Solar energy is recently considered a great source of energy that fulfills the demand for electricity due to its low-cost production as conventional or nonrenewable energy sources are being depleted with the increase in population. The solar cells function effectively by producing environmentally friendly gases with no toxic products or noise. Dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) are considered to have great potential due to their low fabrication cost and high efficiency in electricity production.1−5

DSSC is composed of many components, such as semiconductors, dye sensitizers, redox electrolytes, and counter electrodes. Solar light is used as a source for the excitation of electrons in organic dyes from their ground state of energy. DSSC has a sandwich-like structure containing two TCO substrates. TCO has a temperature resistance property that is suitable for the TiO2 layer and the transmittance of light. The excited electrons of the oxidized dye are then inserted into the conduction band (CB) of a wide band gap semiconductor (usually TiO2).6 From the CB, electrons are transferred to the transparent conducting glass. These electrons are transported to the electrolyte on the counter electrode by employing an external circuit. Dye gains the electrons from the electrolyte in the dye regeneration process, turning the electrolyte molecules electron-deficient, which diffuse toward the counter electrode.7 The restoration of the initial state of the electrolyte happens on the counter electrode due to the reduction process taking place through a redox mediator. The working process of the DSSCs is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Working scheme of DSSCs from ref (8) reused with permission from Elsevier license number 5712010860265.

The DSSC performance depends on the photosensitive dye bonded on TiO2, which remarkably affects its efficiency.9 A photosensitized dye must have a broad spectrum with a wide absorption. LUMO is confined to the acceptor unit. More electronegativity of the acceptor component of the dye localized the LUMO on the acceptor.10 To avoid carrier recombination processes, HOMO should be located farther from the TiO2 semiconductor. For efficient electron injection, the energy gap of HOMO–LUMO levels of excited dyes must be higher than the CB of semiconductor TiO2 in terms of electronic structure.11 The value of the HOMO of dye molecules must be lesser than the HOMO of the electrolyte (I–/I3–) redox couple of the dye molecule.12 In another step, the photosensitizing process in which the excited electron is directly transferred from the dye at its ground state to the wide CB of the semiconductor is gaining very much importance and recognition due to its more efficient procedure. Furthermore, maximum absorption in the visible region with a wide range of wavelength is responsible to calculate the light-harvesting efficiency (LHE).13−15

Photosensitized dyes must be stable in their excited state as well as in their ionized state to increase their efficiency and consistency, which can be evaluated through an analysis of their chemical reactivity parameters. The molecular structure in good flexibility is fundamentally very important.3 The efficiency and stability of organic dyes are key aspects in improving the performance of DSSCs. Organic dyes in DSSCs consist of a donor (D) moiety linked with an acceptor moiety (A) through π-conjugation as a D-π-A structure, which is responsible for developing a variety of organic dyes.16 They have a basic D-π linker-A structure having π-bridged dye molecules, which link the donor part with the acceptor part of dye molecules. The acceptor unit of dye molecules is responsible to confine the molecule on the semiconductor surface, while the π bridging molecule, due to its conjugation, is responsible for easy charge transfer and efficient light harvesting over a wide range.17−20

Large organic molecules are not easily synthesized by simple processes, so before their preparation in the lab, it is necessary to predict their LHE computationally.21 Various efforts have been made for the theoretical investigation of characteristics of dyes, which explain the modified design of new dyes.22−27 Since the process and function of DSSCs are based on excitation and transport of electrons, quantum-based calculations are used as a guiding principle for the molecular design of dyes.28 Density functional theory (DFT) calculations play an effective role in predicting the geometry of dyes at the ground state.29 To understand the electronic structure of dye molecules, Kohn–Sham (KS) molecular orbital analysis play a fundamental role in understanding the electronic structure of dyes. Time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) methods are used to evaluate the excited states and the optical and electronic properties of dyes.30

In this work, we focus on the study of D-π-A structures containing variable donor and acceptor moieties. The π-linkages contain phenyl, thiophene, imine, and phenyl groups. It has been considered that these groups play a significant role in lowering the HOMO–LUMO gaps and covering a long-range of visible spectra. Literature studies indicate that dyes with a longer range of visible absorption spectrum have greater potential as light-harvesting agents for DSSCs.31 The objective of our work is to design modified dyes by using variable donor and acceptor moieties on the primary molecular structure of guanidine and finding the dyes that can be employed in DSSCs with efficient characteristics analyzed through quantum calculations.

2. Computational Details

2.1. Methods

To study the charge density, electronic transition, and absorption spectra of molecules, TD-DFT is being used.32 TD-DFT is used to efficiently study the oscillatory strengths of transitions and their excitation energies. For TD-DFT calculations, time-dependent perturbation (TD perturbation) was applied to the ground state of the molecule.33 TD-DFT also provides calculations about the charge density response, which in turn determines the excitation spectrum in the dipole approximation. Frequency-dependent polarizability α̅(ω)34 is the study of dipole moment (DM) to oscillation in the TD-DFT field and given below as eq 1

| 1 |

where ωI = excitation energy and fI = oscillator strength. Frequency-dependent local density approximation (LDA) is employed by Gaussian 16 which provides potential change due to perturbation in the applied electric field. Fractional derivative35 provides kernel fxc as under (eq 2):

| 2 |

where vσxc = exchange correlation for σ spin density of electron and ρτ = density of τ-spin of electron.36 In order to calculate the oscillator strength and energies of excitation, the eigen value equation ωi is given as under (eq 3):

| 3 |

where Ω = index matrix related to spin and Fi = eigen vectors. DFT is used to study the optical and electronic behaviors of observed molecules by operating the KS framework. These DFT calculations about energy states helped to study various optical properties such as the ionization energy, global hardness (η), chemical potential (μ), electron affinity, transfer of charge, and DM of molecules. The DFT gives the total energy of molecules as E(ρ) = Ee(ρ) + ∫ V(r)ρ(r)dr where Ee is the electronic energy, V stands for the potential to calculate the attraction between the nucleus and the electron, and ρ is the electron density.37

2.2. Calculations

DFT and TD-DFT were carried out computationally in Gaussian 16 to calculate the ground-state geometries of 20 guanine-derived dye molecules (A1–A18) which were optimized under B3LYP functional with 6-31G, 6-311G, and cc-PVDZ basis sets. BPV86, LSDA, and B3PW91 functionals were also utilized for some compounds to study the optical and electric parameters. The DFT calculations were carried out in Gaussian 16W by using B3LYP along with the LanL2DZ basis set to study the interaction of the TiO2 semiconductor with the organic dye. The chemical structures of dye molecules (A1–A18) are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Chemical Structures of Guanine-Derived Dye Molecules (A1–A18).

HOMO is related to the donor moiety and LUMO is related to the electron acceptor unit of a molecule. The HOMO–LUMO energy gap was used to explain the electronic and optical properties of molecules, such as the chemical reactivity and stability of dye molecules.38 KS framework was able to calculate the electronegativity (x), chemical hardness (η), and chemical potential (μ) by using the following eqs 4, 5, and 6. IP (−EHOMO) stands for the ionization potential of the HOMO, and EA (−ELUMO) is related to the electron affinity of the LUMO. The global softness (σ) of dye molecules can be calculated by using following eq 7.39 Parr et al.40 found the electrophilicity index (ω) that is used to calculate the strength of electrophilicity using eq 8.41

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

3. Results and Discussion

The electronic structures of all guanidine-based organic dyes with different D-π-A structural modifications are geometrically optimized, as given in Table 1. We attempted to get the values of desired properties of dyes with D-π-A structures through structural modification, which is helpful in calculating the energy levels of frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs). The guanidine central unit is substituted with some electron donor moieties, e.g., NH2 in some structures acts as the donor (D) part, which is linked with the π-linker phenyl ring. Thiophene substituted with different functional groups, i.e., −COOH, – CN, and −NO2, acts as an acceptor (A) moiety. These functional groups proved to be proficient anchoring groups on the surface of semiconductor TiO2, which supports efficient charge transfer and makes them very effective candidates to enhance the efficiency of DSSCs.

3.1. Molecular Orbital Analysis

In the FMO analysis of dye molecules, the HOMO is associated with the donor part of the molecule, and the LUMO is related to the acceptor unit of the molecule. Introducing a variety of functional groups in guanidine nuclei may alter the HOMO–LUMO gap, which obviously alters the charge transfer. This alteration in the HOMO–LUMO energy gap is very effective for studying the electronic and optical properties of dye molecules. The concentration of electron density of HOMO-3 is higher than the concentration of electron density in HOMO, HOMO-1, and HOMO-2. The contribution of HOMO-3 is greater from the nitrogen atom of the basic unit of guanidine and conjugated linked units. The major contribution of almost more than 40% of LUMOs of dye molecules, which are limited on the acceptor part, is from the central part of guanidine. Some contribution of LUMOs is due to the presence of specific functional groups attached to thiophene and benzene rings. The charge density of LUMO among LUMO-1, LUMO-2, and LUMO-3 is greater for all dyes. HOMO levels of all dyes are found to be close to each other in contrast to LUMOs with a remarkable difference in energy, as given in Figure 2a,b.

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic molecular orbital energy levels of guanidine-based dyes [A1–A9(trans)]and CB of TiO2 electrolyte used as the reference. (b) Schematic molecular orbital energy levels of guanidine-based dyes (A10–A18)and CB of TiO2 electrolyte used as the reference.

The changes in the positions of HOMOs, LUMOs, and the HOMO–LUMO gap are due to the structural modifications of dye molecules. Such changes in FMOs describe the transition of charge transfer due to the structural modification of molecules. The energy gap between HOMO and LUMO explains the stability of the molecule and other optical parameters of the molecule.42 For efficient energy conversion, the HOMO value of the molecule must be less than the HOMO value of the redox couple I3–/I, i.e., −4.9 eV,43 while the value of LUMO of the dye molecule must be greater than the value of CB of the semiconductor TiO2, i.e., −4 eV.44 Different functionals like BPV86, LSDA, and B3PW91 with basis set 6-311G in addition to B3LYP functionals with various basis sets 6-31G, 6-311G, and cc-PVDZ were utilized for the optimizations and calculations, and comparative data are reported in Table 1. ELUMO, EHOMO values of [A10–A8(trans)] dyes calculated with B3LYP functionals achieved EHOMO from −5.29 to −6.08 eV and ELUMO from −2.39 to −2.9 eV as shown in Table 2. These calculated values prove the ultrafast injection of electrons from the dye molecule into the CB of the TiO2 semiconductor. One leading dye molecule among other efficient dyes has achieved HOMO/LUMO at −5/–3.5 eV.45 This is a reasonable HOMO–LUMO gap, which is sufficient for expanding the region of energy conversion. The B3LYP calculated values of EHOMO – ELUMO gap (ΔE) of [A1–A18(trans)] dyes are given in Table 2.

Table 2. B3LYP (Otherwise Defined) Calculated Values of ELUMO, EHOMO, and EHOMO – ELUMO gap (ΔE) of A1–A18 Dyes.

| dyes | ELUMO (eV) | EHOMO (eV) | EHOMO – ELUMO gap ΔE (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | –2.84 | –6.02 | 3.186 |

| A1(BPV86) | –4.12 | –5.33 | 1.21 |

| A1(LSDA) | –4.73 | –5.97 | 1.24 |

| A1(B3PW91) | –3.27 | –6.14 | 2.87 |

| A2 | –2.77 | –6.08 | 3.302 |

| A2(BPV86) | –3.83 | –5.30 | 1.47 |

| A2(LSDA) | –4.48 | –5.83 | 1.35 |

| A2(B3PW91) | –2.98 | –6.13 | 3.15 |

| A3 | –2.62 | –5.93 | 3.316 |

| A3(BPV86) | –3.75 | –5.20 | 1.45 |

| A3(LSDA) | –4.34 | –5.71 | 1.37 |

| A3(B3PW91) | –2.88 | –6.02 | 3.14 |

| A4 | –2.39 | –5.29 | 2.897 |

| A5 | –2.49 | –5.42 | 2.93 |

| A6 | –2.49 | –5.34 | 2.85 |

| A7 | –2.61 | –5.66 | 3.06 |

| A8 | –2.58 | –5.39 | 2.81 |

| A9(cis) | –2.75 | –5.82 | 3.07 |

| A9DMSO(cis) | –2.79 | –5.79 | 3.01 |

| A9(trans) | –2.9 | –5.71 | 2.83 |

| A10 | –2.6 | –5.58 | 2.98 |

| A11 | –2.52 | –5.12 | 2.6 |

| A12 | –2.54 | –5.36 | 2.82 |

| A13 | –2.73 | –5.64 | 2.92 |

| A14 | –2.69 | –5.75 | 3.05 |

| A15 | –2.62 | –5.73 | 3.1 |

| A16(cis) | –2.44 | –5.58 | 3.14 |

| A16(trans) | –2.53 | –5.48 | 2.95 |

| A17 | –2.75 | –5.75 | 2.99 |

| A18 | –2.74 | –5.77 | 3.02 |

3.2. Reactivity Descriptors

The parameters of the chemical reactivity of the dye molecule show the ability of molecule to stabilize in its environment.46 Different functionals like BPV86, LSDA, and B3PW91 with the basis set 6-311G in addition to B3LYP functionals with various basis sets 6-31G, 6-311G, and cc-PVDZ were utilized for the calculations and comparative data reported in Table 3. Different chemical parameters, which were calculated and reported in Table 3 such as the chemical and ionization potential, the global hardness and softness, the DM, and the transition dipole moment (TDM) well explained the chemical attitude of dye molecules. The HOMO–LUMO energy gap largely affected the hardness and softness of the molecule, that is, a lower energy gap is associated with the softness of the molecule and a higher energy gap value indicates the hardness of the molecule.47 Similarly, ionization potential (IP) values are responsible for the reactivity parameters of the molecule as a greater value of IP increases the reactivity of the molecule. Moreover, less softness value and high hardness value are responsible for the high stability and less reactivity of the dye as given in Table 3. A1, A2, A3, and A15 are found to be the most stable thermally and kinetically among all studied dye molecules because of calculated global hardness and chemical potential values. From the negative potential value, we observed that the dyes have a greater ability to gain electrons from the environment. So, most of the dyes efficiently convert solar energy to electrical energy due to their high reactivity and high charge- transfer tendency.

Table 3. DFT-B3LYP (Otherwise Defined) Calculated Chemical Reactivity Parameters of A1–A18 Dyes.

| dyes | electron affinity (EA) | ionization potential (IP) | electronegativity (x) | electrophilicity (ω) | chemical potential (μ) | global hardness (η) | global softness (σ) | DM (D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 2.84 | 6.02 | 4.43 | 0.359 | –1.59 | 4.429 | 0.113 | 5.605 |

| A1(BPV86) | 4.12 | 5.33 | 5.03 | 0.035 | –0.60 | 5.03 | 0.099 | 5.967 |

| A1(LSDA) | 4.73 | 5.97 | 5.04 | 0.038 | –0.62 | 5.04 | 0.099 | 6.066 |

| A1(B3PW91) | 3.27 | 6.14 | 4.70 | 0.304 | –1.43 | 4.70 | 0.106 | 5.868 |

| A2 | 2.77 | 6.08 | 4.425 | 0.386 | –1.65 | 4.275 | 0.117 | 5.967 |

| A2(BPV86) | 3.83 | 5.30 | 4.56 | 0.160 | –0.73 | 4.56 | 0.109 | 5.884 |

| A2(LSDA) | 4.48 | 5.83 | 5.15 | 0.130 | –0.67 | 5.15 | 0.097 | 5.957 |

| A2(B3PW91) | 2.98 | 6.13 | 4.54 | 0.345 | –1.57 | 4.54 | 0.110 | 5.785 |

| A3 | 2.62 | 5.93 | 4.275 | 0.386 | –1.65 | 4.275 | 0.117 | 2.755 |

| A3(BPV86) | 3.75 | 5.20 | 4.47 | 0.161 | –0.72 | 4.47 | 0.111 | 2.745 |

| A3(LSDA) | 4.34 | 5.71 | 5.02 | 0.135 | –0.68 | 5.02 | 0.099 | 2.782 |

| A3(B3PW91) | 2.88 | 6.02 | 4.45 | 0.352 | –1.57 | 4.45 | 0.112 | 2.755 |

| A4 | 2.39 | 5.29 | 3.84 | 0.374 | –1.45 | 3.873 | 0.129 | 1.321 |

| A5 | 2.49 | 5.42 | 3.955 | 0.369 | –1.46 | 3.95 | 0.126 | 1.47 |

| A6 | 2.49 | 5.34 | 3.915 | 0.365 | –1.43 | 3.916 | 0.128 | 1.472 |

| A7 | 2.61 | 5.66 | 4.135 | 0.370 | –1.53 | 4.134 | 0.121 | 5.668 |

| A8 | 2.58 | 5.39 | 3.985 | 0.354 | –1.41 | 3.983 | 0.126 | 2.649 |

| A9(cis) | 2.75 | 5.82 | 4.285 | 0.357 | –1.53 | 4.286 | 0.117 | 6.886 |

| A9DMSO(cis) | 2.79 | 5.79 | 4.29 | 0.316 | –1.50 | 4.22 | 0.102 | 6.79 |

| A9(trans) | 2.9 | 5.71 | 4.305 | 0.328 | –1.41 | 4.3 | 0.116 | 8.98 |

| A10 | 2.6 | 5.58 | 4.09 | 0.364 | –1.49 | 4.088 | 0.122 | 2.636 |

| A11 | 2.52 | 5.12 | 3.82 | 0.340 | –1.3 | 3.82 | 0.131 | 1.89 |

| A12 | 2.54 | 5.36 | 3.95 | 0.356 | –1.41 | 3.95 | 0.127 | 2.174 |

| A13 | 2.73 | 5.64 | 4.185 | 0.348 | –1.46 | 4.19 | 0.119 | 6.33 |

| A14 | 2.69 | 5.75 | 4.22 | 0.360 | –1.52 | 4.22 | 0.118 | 6.734 |

| A15 | 2.62 | 5.73 | 4.175 | 0.371 | –1.55 | 4.17 | 0.119 | 7.64 |

| A16(cis) | 2.44 | 5.58 | 4.01 | 0.391 | –1.57 | 4.01 | 0.125 | 7.5 |

| A16(trans) | 2.53 | 5.48 | 4.005 | 0.368 | –1.47 | 4.0 | 0.125 | 10.26 |

| A17 | 2.75 | 5.75 | 4.25 | 0.351 | –1.49 | 4.25 | 0.118 | 4.26 |

| A18 | 2.74 | 5.77 | 4.255 | 0.171 | –1.51 | 8.84 | 0.057 | 7.5 |

3.3. Spectral Properties

Although dye molecules show more sensitivity toward the absorption spectrum in the visible region, conventional dyes are sensitive in the visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum. Photons of wavelength less than 920 nm can be used in the photovoltaic conversion of universal AM 1.5 illumination into electricity.48 In DSSCs, UV light can be useful by using materials with low conversion luminescence.49 The DFT spectral studies of dye molecules in the UV region predict the degradation of dye upon UV exposure.50 Therefore, the most competent and leading organic dye is the one that shows a strong excitation peak in the visible spectral region, which is very helpful in understanding the prospective transition of electrons from the dye to the semiconductor surface.

Elucidation of spectral properties of dyes was done through TD-DFT-B3LYP at the ground-state equilibrium geometry (enlisted in Table 4), and conclusive simulated excitation spectra are shown in Figure 3. The transition of intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) is directly affected by the light LHE. A1–A18 dyes have shown more than 40% transfer of charge from the corresponding HOMO levels to the respective LUMO levels as shown in Figure 4a–d. A9(cis), A15, A16(cis), A16(trans), A17, and A18 dyes have exhibited more than 95% charge transfer from H-0 → L + 1 transition as shown in Table 4. It has been studied that the most effective energy gap (ΔE) should be in the range between 1.1 and 2 eV to get an efficient value of LHE.51 Energy gap (ΔE) for [A1–A18(trans)] dyes was found to be greater than 2.0 eV. Oscillator strength describes the strength of absorbing energy in the solar spectrum. LHE increases with the increasing value of oscillator strength as LHE = 1–10f where f is the oscillator strength.52A9(cis), A15, A16(cis), A16(trans), A17, and A18 dyes were found to have higher oscillator strengths and hence significant LHEs as depicted in Table 4. TDM is also related to the oscillator strength. All [A1–A18(trans)] dyes showed that the structural axis of the dye is responsible for the TDM. In the study of all dye molecules, A9 (cis) and A9(trans) exhibited the highest value of TDM as well as a high value of oscillator strength.

Table 4. TD-DFT-B3LYP Calculated Spectral Parameters of A1–A18 Dyes.

| dyes | λmax | EHOMO – ELUMO gap (ΔE) (eV) | oscillator strength f (a.u) | TDM (a.u) | major transitions | LHE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 476.8 | 3.186 | 0.02 | 0.3143 | H-0→L+0 (57%) | 0.05 |

| A2 | 385 | 3.302 | 0.012 | 0.1564 | H-2→L+0 (61%) | 0.03 |

| A3 | 382.37 | 3.316 | 0.013 | 0.168 | H-2→L+0 (64%) | 0.03 |

| A4 | 399.96 | 2.897 | 0.013 | 0.1728 | H-2→L+0 (71%) | 0.03 |

| A5 | 405.93 | 2.93 | 0.013 | 0.1712 | H-2→L+0 (70%) | 0.03 |

| A6 | 412.57 | 2.85 | 0.011 | 0.1516 | H-2→L+0 (63%) | 0.02 |

| A7 | 397.72 | 3.06 | 0.013 | 0.1687 | H-2→L+0 (62%) | 0.03 |

| A8 | 421 | 2.81 | 0.0083 | 0.1158 | H-2→L+0 (52%) | 0.02 |

| A9(cis) | 412 | 3.07 | 0.509 | 0.69 | H-0→L+1 (98%) | 0.69 |

| A9DMSO(cis) | 412 | 3.01 | 0.501 | 0.67 | H-0→L+1 (98%) | 0.67 |

| A9(trans) | 432.76 | 2.83 | 0.048 | 0.68 | H-2→L+1 (84%) | 0.11 |

| A10 | 406 | 2.98 | 0.011 | 0.1451 | H-2→L+0 (44%) | 0.02 |

| A11 | 633 | 2.6 | 0.0064 | 0.1329 | H-2→L+0 (46%) | 0.02 |

| A12 | 416 | 2.82 | 0.01 | 0.1451 | H-2→L+0 (61%) | 0.02 |

| A13 | 413 | 2.92 | 0.009 | 0.1245 | H-2→L+0 (54%) | 0.02 |

| A14 | 402 | 3.05 | 0.01 | 0.1286 | H-0→L+1 (56%) | 0.02 |

| A15 | 418 | 3.1 | 0.506 | 6.98 | H-0→L+1 (98%) | 0.69 |

| A16(cis) | 430 | 3.14 | 0.449 | 6.37 | H-0→L+1 (96%) | 0.65 |

| A16(trans) | 432 | 2.95 | 0.523 | 7.44 | H-0→L+1 (96%) | 0.7 |

| A17 | 416 | 2.99 | 0.414 | 5.68 | H-0→L+1 (97%) | 0.61 |

| A18 | 414 | 3.02 | 0.464 | 6.34 | H-0→L+1 (98%) | 0.66 |

Figure 3.

TD-DFT-B3LYP calculated excitation spectra of representative guanidine-based dyes [A9(cis), A15, A16(cis), A16(trans), and A17].

Figure 4.

(a) FMOs for main transitions of guanidine-based dyes (A1–A5) using the DFT-B3LYP method, (b) FMOs for main transitions of guanidine-based dyes [A6–A9(trans)] using the DFT-B3LYP method, (c) FMOs for main transitions of guanidine-based dyes (A10–A14) using the DFT-B3LYP method, and (d) FMOs for main transitions of guanidine-based dyes (A15–A18) using the DFT-B3LYP method.

TD-DFT-B3LYP-calculated excitation spectra of representative guanine-derived dyes [A9(cis), A15, A16(cis), A16(trans), and A17] are presented in Figure 3. It has been analyzed from wave functions that absorption (λmax) is due to the transition of electrons from the ground-state HOMO level to the excited-state LUMO level. The excitation peaks describe the values of LHE which in turn is related to the oscillator strength values (given in Table 4), and molecular orbitals are involved in the major transition of electrons, as mentioned in Figure 4a–d. It was observed that the change in the basic guanidine subunit by introducing thiophene substituted with a specific functional group remarkably effected the π-conjugation that may be responsible for the HOMO–LUMO gap as well as upshift and downshift of the absorption region of the spectrum. These absorption maxima in the 300–600 nm range correspond to the maximum oscillator strengths for each dye molecule. The highest intensity peak was observed for [A9(cis), A15, A16(cis), A16(trans), and A17] which have a nitro group-substituted thiophene ring that is attached to the phenyl ring of the guanidine subunit. As thiophene units are reported, there is a consequent increase in the length of the D-π-A type dye, which causes a redshift of the absorption bands toward the visible region.13A9(cis) has shown that maximum absorption at 411 nm corresponds to charge transfer (98%) between major molecular orbitals involved (H-0→L+1). A15 shows that the maximum absorption at 420 nm corresponds to charge transfer (98%) between major molecular orbitals involved (H-0→L+1). A16(cis) and A16(trans) show maximum absorption at 432 nm, which corresponds to charge transfer (96%) between major molecular orbitals involved (H-0→L+1). A17 shows maximum absorption at 417 nm, which corresponds to charge transfer (97%) between the major molecular orbitals involved (H-0→L+1).

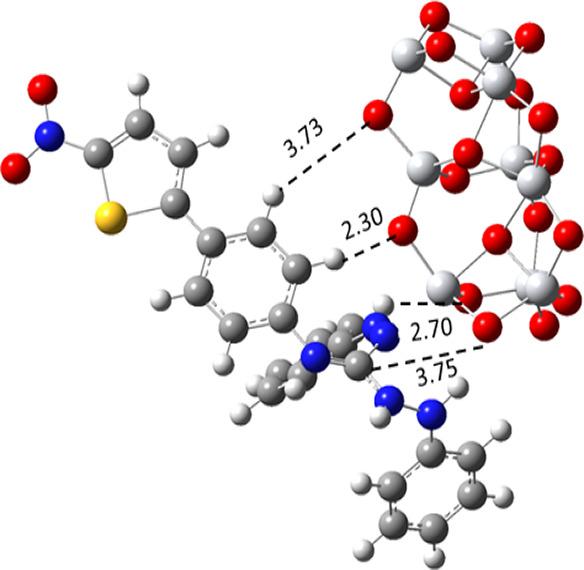

3.4. DFT Study of Dye-TiO2 Interaction

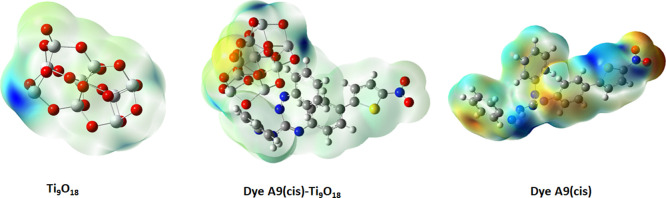

TiO2, as a nanoparticle, is a photoactive material because of its stability. It has potential applications in solar energy conversion and keeping the environment green. DFT study of organic dyes with the interaction with TiO2 prior to synthesizing the organic dye as the photosensitizer is very important to check its efficiency toward DSSCs. For the DFT study, the dye-TiO2 interaction was carried out at Gaussian 16W using the B3LYP hybrid functional and LanL2DZ basis set. First, TiO2 oligomers with up to nine repeating units were optimized, followed by the calculation of their interaction with the dye. There are different intermolecular interactions observed between the C and H of the dye with the O atom of TiO2, as mentioned in Figure 5. Band gap of dye A9-cis is 3.07 eV and band gap of TiO2 is 2.05 while on interaction, and the band gap between HOMO–LUMO became 1.55 eV as mentioned in Figure 6. This decrease in band gap ensures the excellent photoactive property of the dye which is correlated with the π-conjugation of the organic dye.

Figure 5.

Optimized geometric structure of the dye A9(cis)-Ti9O18 bounded complex.

Figure 6.

FMOs of the dye A9(cis)-Ti9O18 bounded complex.

3.5. Molecular Electrostatic Potential Reactivity Study

Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) was carried out by using Gaussian 16W/B3LYP/LanL2DZ in the gas phase with TD-DFT as shown in Figure 7. For A9 (cis) compound contour plots, the optimized structure and MEP surfaces were evaluated, and nucleophilic and electrophilic properties were explained using different colors. Red indicates higher energy area and explains the electrophilic (attractive) potential, and blue indicates lower energy area which explains the nucleophilic (repulsive) potential. Electrostatic potential reduces in the order as red < orange < yellow < green < blue.

Figure 7.

MEP plots of Ti9O18, dye A9(cis)-Ti9O18, and dye A9(cis).

3.6. Vibrational Analysis

Theoretical vibrational analysis was calculated by using Gaussian 16W under hybrid functional B3LYP with the LanL2DZ basis set, as shown in Figure 8. It was observed from the spectrum obtained by calculating the frequency of the A9 (cis) molecule that strong intensity of absorption around 3200–3400 cm–1 indicates the presence of the N–H bond. Aromatic C–H and C–C bonds express their peaks in the normal region. Azo linkage in the compound was indicated in the range 1400–1520 cm–1, and the guanidine center was observed in the band range 1550–1700 cm–1.

Figure 8.

IR spectrum of dye A9(cis).

3.7. Conformational Analysis

Conformational analysis was performed using DFT/B3LYP/LanL2DZ for A9(cis). Conformers of A9(cis) with minima were evaluated using potential energy scan (PES) as shown in Figure 9a. It indicates four conformers with minima with total energy and scan coordinates of −1742.51574, −1742.50824, −1742.50824, and −1742.51574 kcal/mol. DFT scans suggest a total energy of −1742.54 kcal/mol with the scan coordinate 1 at −109.928 and scan coordinate 2 at 124.219 as shown in Figure 9b.

Figure 9.

(a) PES of dye A9(cis). (b) PES grid of dye A9(cis).

4. Conclusions

We explored the optical and electronic attitudes of guanidine-based organic dye molecules (A1–A18) computationally by using DFT under the B3LYP functional with various basis sets. The geometry of dye molecules in the ground state was completely optimized to study the properties of FMOs along with the excitation spectra in detail. The calculated values obtained from the computational studies of guanidine-based dyes showed that the optical properties such as energy gaps, excitation properties, TDM, oscillator strength, and LHE depend on the structural modifications of the dyes. It has been found that dyes with a thiophene moiety substituted with a NO2 group have good light LHEs. The density of charge was more dependent on the inner levels of HOMO. Therefore, ICT from inner HOMO levels is responsible for increasing excitation energy. The chromophore groups present in guanidine-based dyes are responsible to give absorption spectra in the visible region. Better anchorage of dye molecules to the surface of TiO2 semiconductors helps in charge-transfer phenomena, and the results suggested that −COOH, – CN, and–NO2 proved as proficient anchoring groups making dyes very beneficial and effective candidates for DSSCs. The high negative value of HOMO levels as compared to the redox couple (I–/I3–) reduction proves that these dyes are promising and appropriate leading molecules for superfast transfer of electrons into the CB of TiO2. Similarly, various other parameters, such as MEP, vibrational analysis, and conformational analysis, explained the high efficiency of organic dyes in solar cell fabrication. The high oscillator strength and good excitation spectra of these dyes give greater LHE, which increases the suitability of dyes for application in DSSCs.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), with the grant numbers EP/S030786/1 and EP/T025875/1 from the University of Exeter. However, the EPSRC was not directly involved in the writing of this article. Ms. Uzma Hashmat also acknowledges the Higher Education Commission (HEC), Pakistan for the award of International Research Support Initiative Programme (IRSIP) fellowship. This work is from Ph.D thesis of Ms. Uzma Hashmat.

Data Availability Statement

There is no associated data with this article.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

This paper originally published ASAP on March 14, 2024. The author list was updated, and a new version reposted on March 15, 2024.

References

- O’regan B.; Grätzel M. A low-cost, high-efficiency solar cell based on dye-sensitized colloidal TiO2 films. nature 1991, 353 (6346), 737. 10.1038/353737a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nazeeruddin M. K.; Pechy P.; Renouard T.; Zakeeruddin S. M.; Humphry-Baker R.; Comte P.; Liska P.; Cevey L.; Costa E.; Shklover V. Engineering of efficient panchromatic sensitizers for nanocrystalline TiO2-based solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123 (8), 1613–1624. 10.1021/ja003299u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K.; Sato T.; Katoh R.; Furube A.; Yoshihara T.; Murai M.; Kurashige M.; Ito S.; Shinpo A.; Suga S. Novel conjugated organic dyes for efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2005, 15 (2), 246–252. 10.1002/adfm.200400272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.; Lee J. K.; Kang S. O.; Ko J.; Yum J.-H.; Fantacci S.; De Angelis F.; Di Censo D.; Nazeeruddin M. K.; Grätzel M. Molecular engineering of organic sensitizers for solar cell applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128 (51), 16701–16707. 10.1021/ja066376f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velusamy M.; Justin Thomas K.; Lin J. T.; Hsu Y.-C.; Ho K.-C. Organic dyes incorporating low-band-gap chromophores for dye-sensitized solar cells. Org. Lett. 2005, 7 (10), 1899–1902. 10.1021/ol050417f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L.; Wang P.; Yang Y.; Zhan Z.; Dong Y.; Song W.; Fan R. Enhanced performance of the dye-sensitized solar cells by the introduction of graphene oxide into the TiO 2 photoanode. Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers 2018, 5 (1), 54–62. 10.1039/C7QI00503B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lennert A.; Wagner K.; Yunis R.; Pringle J. M.; Guldi D. M.; Officer D. L. Efficient and Stable Solid-State Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells by the Combination of Phosphonium Organic Ionic Plastic Crystals with Silica. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10 (38), 32271–32280. 10.1021/acsami.8b12334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan R.; Kushwaha R.; Bahadur L. Study of Light Harvesting Properties of Different Classes of Metal-Free Organic Dyes in TiO2 Based Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Energy 2014, 2014, 517574 10.1155/2014/517574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Labat F.; Le Bahers T.; Ciofini I.; Adamo C. First-principles modeling of dye-sensitized solar cells: challenges and perspectives. Accounts of chemical research 2012, 45 (8), 1268–1277. 10.1021/ar200327w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi D.; Ma X.; Ansari R.; Kim J.; Kieffer J. Design principles for the energy level tuning in donor/acceptor conjugated polymers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21 (2), 789–799. 10.1039/C8CP03341B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thavasi V.; Renugopalakrishnan V.; Jose R.; Ramakrishna S. Controlled electron injection and transport at materials interfaces in dye sensitized solar cells. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports 2009, 63 (3), 81–99. 10.1016/j.mser.2008.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bahers T.; Pauporté T.; Scalmani G.; Adamo C.; Ciofini I. A TD-DFT investigation of ground and excited state properties in indoline dyes used for dye-sensitized solar cells. Physical chemistry chemical physics 2009, 11 (47), 11276–11284. 10.1039/b914626a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namuangruk S.; Fukuda R.; Ehara M.; Meeprasert J.; Khanasa T.; Morada S.; Kaewin T.; Jungsuttiwong S.; Sudyoadsuk T.; Promarak V. D–D– π–A-Type organic dyes for dye-sensitized solar cells with a potential for direct electron injection and a high extinction coefficient: synthesis, characterization, and theoretical investigation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116 (49), 25653–25663. 10.1021/jp304489t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. G.; Devi L. G. Review on modified TiO2 photocatalysis under UV/visible light: selected results and related mechanisms on interfacial charge carrier transfer dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115 (46), 13211–13241. 10.1021/jp204364a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tae E. L.; Lee S. H.; Lee J. K.; Yoo S. S.; Kang E. J.; Yoon K. B. A strategy to increase the efficiency of the dye-sensitized TiO2 solar cells operated by photoexcitation of dye-to-TiO2 charge-transfer bands. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109 (47), 22513–22522. 10.1021/jp0537411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin P.; Yang X.; Chen R.; Sun L.; Marinado T.; Edvinsson T.; Boschloo G.; Hagfeldt A. Influence of π-conjugation units in organic dyes for dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111 (4), 1853–1860. 10.1021/jp065550j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dentani T.; Kubota Y.; Funabiki K.; Jin J.; Yoshida T.; Minoura H.; Miura H.; Matsui M. Novel thiophene-conjugated indoline dyes for zinc oxide solar cells. New J. Chem. 2009, 33 (1), 93–101. 10.1039/B808959K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Imahori H.; Umeyama T.; Ito S. Large π-aromatic molecules as potential sensitizers for highly efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. Accounts of chemical research 2009, 42 (11), 1809–1818. 10.1021/ar900034t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooyama Y.; Harima Y. Photophysical and Electrochemical Properties, and Molecular Structures of Organic Dyes for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. ChemPhysChem 2012, 13 (18), 4032–4080. 10.1002/cphc.201200218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giribabu L.; Duvva N.; Prasanthkumar S.; Singh S. P.; Han L.; Bedja I.; Gupta R. K.; Islam A. Effect of spacers and anchoring groups of extended π-conjugated tetrathiafulvalene based sensitizers on the performance of dye sensitized solar cells. Sustainable Energy & Fuels 2017, 1 (2), 345–353. 10.1039/C6SE00014B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi N.; Wang F. First-principles study of Carbz-PAHTDDT dye sensitizer and two Carbz-derived dyes for dye sensitized solar cells. J. Mol. Model. 2014, 20 (3), 2177. 10.1007/s00894-014-2177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J.; Sumathy K.; Qiao Q.; Zhou Z. Review on dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs): Advanced techniques and research trends. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 68, 234–246. 10.1016/j.rser.2016.09.097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chitumalla R. K.; Gupta K. S.; Malapaka C.; Fallahpour R.; Islam A.; Han L.; Kotamarthi B.; Singh S. P. Thiocyanate-free cyclometalated ruthenium (II) sensitizers for DSSC: a combined experimental and theoretical investigation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16 (6), 2630–2640. 10.1039/c3cp53613k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitri A.; Benjelloun A. T.; Benzakour M.; Mcharfi M.; Hamidi M.; Bouachrine M. Theoretical investigation of new thiazolothiazole-based D-π-A organic dyes for efficient dye-sensitized solar cell. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2014, 124, 646–654. 10.1016/j.saa.2014.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bahers T.; Pauporté T.; Lainé P. P.; Labat F.d. r.; Adamo C.; Ciofini I. Modeling dye-sensitized solar cells: From theory to experiment. journal of physical chemistry letters 2013, 4 (6), 1044–1050. 10.1021/jz400046p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-de-Armas R.; San Miguel M. A.; Oviedo J.; Sanz J. F. Coumarin derivatives for dye sensitized solar cells: a TD-DFT study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14 (1), 225–233. 10.1039/C1CP22058F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majid A.; Bibi M.; Khan S. U. D.; Haider S. First Principles Study of Dendritic Carbazole Photosensitizer Dyes Modified with Different Conjugation Structures. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4 (9), 2787–2794. 10.1002/slct.201803575. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obotowo I.; Obot I.; Ekpe U. Organic sensitizers for dye-sensitized solar cell (DSSC): properties from computation, progress and future perspectives. J. Mol. Struct. 2016, 1122, 80–87. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2016.05.080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santhanamoorthi N.; Lo C.-M.; Jiang J.-C. Molecular design of porphyrins for dye-sensitized solar cells: a DFT/TDDFT study. journal of physical chemistry letters 2013, 4 (3), 524–530. 10.1021/jz302101j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Kan Y.-H.; Li H.-B.; Geng Y.; Wu Y.; Su Z.-M. How to design proper π-spacer order of the D-π-A dyes for DSSCs? A density functional response. Dyes Pigm. 2012, 95 (2), 313–321. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2012.05.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balasingam S. K.; Lee M.; Kang M. G.; Jun Y. Improvement of dye-sensitized solar cells toward the broader light harvesting of the solar spectrum. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49 (15), 1471–1487. 10.1039/C2CC37616D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casida M. E.; Jamorski C.; Casida K. C.; Salahub D. R. Molecular excitation energies to high-lying bound states from time-dependent density-functional response theory: Characterization and correction of the time-dependent local density approximation ionization threshold. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 108 (11), 4439–4449. 10.1063/1.475855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood U.; Hussein I. A.; Daud M.; Ahmed S.; Harrabi K. Theoretical study of benzene/thiophene based photosensitizers for dye sensitized solar cells (DSSCs). Dyes Pigm. 2015, 118, 152–158. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2015.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson W. A.; Oddershede J. Quadratic response theory of frequency-dependent first hyperpolarizability. Calculations in the dipole length and mixed-velocity formalisms. J. Chem. Phys. 1991, 94 (11), 7251–7258. 10.1063/1.460209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schipper P. R.; Gritsenko O. V.; van Gisbergen S. J.; Baerends E. J. Molecular calculations of excitation energies and (hyper) polarizabilities with a statistical average of orbital model exchange-correlation potentials. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 112 (3), 1344–1352. 10.1063/1.480688. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chelikowsky J. R.; Kronik L.; Vasiliev I. Time-dependent density-functional calculations for the optical spectra of molecules, clusters, and nanocrystals. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2003, 15 (35), R1517. 10.1088/0953-8984/15/35/201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gisbergen S.; Snijders J.; Baerends E. Implementation of time-dependent density functional response equations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1999, 118 (2–3), 119–138. 10.1016/S0010-4655(99)00187-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sumrra S. H.; Kausar S.; Raza M. A.; Zubair M.; Zafar M. N.; Nadeem M. A.; Mughal E. U.; Chohan Z. H.; Mushtaq F.; Rashid U. Metal based triazole compounds: Their synthesis, computational, antioxidant, enzyme inhibition and antimicrobial properties. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1168, 202–211. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.05.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma Y.Elementary organic spectroscopy; S. Chand Publishing, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Parr R. G.; Szentpály L. v.; Liu S. Electrophilicity index. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121 (9), 1922–1924. 10.1021/ja983494x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arjunan V.; Saravanan I.; Ravindran P.; Mohan S. Structural, vibrational and DFT studies on 2-chloro-1H-isoindole-1, 3 (2H)-dione and 2-methyl-1H-isoindole-1, 3 (2H)-dione. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2009, 74 (3), 642–649. 10.1016/j.saa.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona C. M.; Li W.; Kaifer A. E.; Stockdale D.; Bazan G. C. Electrochemical considerations for determining absolute frontier orbital energy levels of conjugated polymers for solar cell applications. Advanced materials 2011, 23 (20), 2367–2371. 10.1002/adma.201004554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Jennings J. R.; Parameswaran M.; Wang Q. An organic redox mediator for dye-sensitized solar cells with near unity quantum efficiency. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4 (2), 564–571. 10.1039/C0EE00519C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood U.; Hussein I. A.; Harrabi K.; Mekki M.; Ahmed S.; Tabet N. Hybrid TiO2–multiwall carbon nanotube (MWCNTs) photoanodes for efficient dye sensitized solar cells (DSSCs). Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2015, 140, 174–179. 10.1016/j.solmat.2015.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jono R.; Fujisawa J.-I.; Segawa H.; Yamashita K. Theoretical study of the surface complex between TiO2 and TCNQ showing interfacial charge-transfer transitions. journal of physical chemistry letters 2011, 2 (10), 1167–1170. 10.1021/jz200390g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aihara J.-I Reduced HOMO– LUMO gap as an index of kinetic stability for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Phys. Chem. A 1999, 103 (37), 7487–7495. 10.1021/jp990092i. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suresh D.; Amalanathan M.; Sebastian S.; Sajan D.; Joe I. H.; Jothy V. B.; Nemec I. Vibrational spectral investigation and natural bond orbital analysis of pharmaceutical compound 7-Amino-2, 4-dimethylquinolinium formate–DFT approach. Spectrochim. Acta A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2013, 115, 595–602. 10.1016/j.saa.2013.06.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C.; Li Y.; Song P.; Ma F. An experimental and theoretical investigation of the electronic structures and photoelectrical properties of ethyl red and carminic acid for DSSC application. Materials 2016, 9 (10), 813. 10.3390/ma9100813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llanos J.; Brito I.; Espinoza D.; Sekar R.; Manidurai P. A down-shifting Eu3+-doped Y2WO6/TiO2 photoelectrode for improved light harvesting in dye-sensitized solar cells. Royal Society Open Science 2018, 5 (2), 171054 10.1098/rsos.171054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari D.; Wrachien N.; Tagliaferro R.; Penna S.; Brown T. M.; Reale A.; Di Carlo A.; Meneghesso G.; Cester A. Thermal stress effects on dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs). Microelectronics Reliability 2011, 51 (9–11), 1762–1766. 10.1016/j.microrel.2011.07.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernede J. Organic photovoltaic cells: history, principle and techniques. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2008, 53 (3), 1549–1564. 10.4067/S0717-97072008000300001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.; Wang J.; Chen J.; Bai F.-Q.; Zhang H.-X. Theoretical investigation of triphenylamine-based sensitizers with different π-spacers for DSSC. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2014, 118, 1144–1151. 10.1016/j.saa.2013.09.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There is no associated data with this article.