Abstract

Background

Multiple chronic conditions (MCCs) are common in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). We examined the association of 12 MCCs with the risk of a 30-day hospital readmission and/or dying within one year among those discharged from the hospital after an AMI. We also examined the five most prevalent pairs of chronic conditions in this population and their association with the principal study endpoints.

Methods

The study population consisted of 3,294 adults hospitalized with a confirmed AMI at the three major medical centers in central Massachusetts on an approximate biennial basis between 2005 and 2015. Patients were categorized as ≤1, 2-3, and ≥4 chronic conditions.

Results

The median age of the study population was 67.9 years, 41.6% were women, and 15% had ≤1, 32% had 2-3, and 53% had ≥4 chronic conditions. Patients with ≥4 conditions tended to be older, had a longer hospital stay, and received fewer cardiac interventional procedures. There was an increased risk for being rehospitalized during the subsequent 30 days according to the presence of MCCs, with the highest risk for those with ≥4 conditions. There was an increased, but attenuated, risk for dying during the next year according to the presence of MCCs. Individuals with diabetes/hypertension and those with heart failure/chronic kidney disease were at particularly high risk for developing the principal study outcomes.

Conclusion

Development of guidelines that include complex patients, particularly those with MCCs and those at high risk for adverse short/medium term outcomes, remain needed to inform best treatment practices.

Keywords: Myocardial infarction, chronic conditions

Highlights

• Multiple chronic conditions (MCCs) are common in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction

• Patients with a greater number of MCCs have poorer short-term outcomes

• Patients with diabetes/hypertension had a higher risk for 30-day hospital readmission while patients with diabetes/chronic kidney disease were at increased risk for dying during the first year after being discharged from the hospital.

The prevalence of multiple chronic conditions (MCCs) in patients with cardiovascular disease has increased in the United States and other industrialized nations as their populations age. Patients hospitalized with an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and MCCs consume disproportionately higher levels of healthcare resources and are at greater risk for adverse outcomes, including readmission to the hospital and death, as compared to those without MCCs.1–6 The clinical management of this vulnerable population is particularly challenging, due in part to the lack of guidelines for their treatment. 7 Healthcare providers struggle with the dilemma of employing treatments that may not be beneficial to individuals with MCCs, and that could cause harm versus denying effective treatments, to these patients who are at higher risk for adverse outcomes and who would benefit from more aggressive management. 8

Despite the high prevalence of MCCs in patients hospitalized for AMI, there are limited recent data describing the clinical characteristics of patients with MCCs, the management of these patients during their hospitalization for AMI, and the association between MCCs and adverse outcomes after being discharged form the hospital after an AMI.

To address these knowledge gaps, to better inform patient-provider decision-making, and to improve the care of those with an AMI and MCCs, we examined the demographic and clinical characteristics, clinical management, and the association between MCCs and the risk of 30-day readmission to the hospital and/or dying within one-year among patients hospitalized with AMI as part of the Worcester Heart Attack Study (WHAS).9–13 A secondary objective of this study was to examine the five most prevalent pairs of chronic conditions in this study population and their association with 30-day hospital readmissions and one-year death rates.

Methods

The Worcester Heart Attack Study is an ongoing population-based investigation that has examined in-hospital and post-discharge trends in the clinical epidemiology of AMI among residents of the Worcester, Massachusetts (MA) metropolitan area hospitalized at all medical centers in central MA on an approximate biennial basis.9–13

Computerized medical records of residents of central MA admitted to the three major hospitals that treat patients with acute coronary disease in the Worcester metropolitan area with possible AMI (International Classification of Disease (ICD) 9 codes 410–414, and 786.5) were identified. Cases of possible AMI were independently validated using predefined criteria for AMI, including diagnoses of ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).14,15 This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School.

Trained nurses and physicians abstracted information on patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics. These characteristics included patients’ age, sex, race/ethnicity, hospital length of stay, and previously diagnosed chronic conditions including anemia, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dementia, depression, diabetes, heart failure, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, and stroke. These 12 chronic conditions were selected based on their high prevalence in our study population and the published literature (see supplemental Table A for ICD-9 codes).1,3,4,16

Data on the receipt of three coronary diagnostic and interventional procedures (cardiac catheterization, percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI], and coronary artery bypass graft surgery [CABG]) during hospitalization, and evidence-based pharmacotherapies during hospitalization, namely angiotensin converting inhibitors (ACE-I)/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), aspirin, beta blockers, and lipid lowering agents were also abstracted from hospital medical records by trained study staff.

We stratified our study population into three MCC groupings, namely those with ≤ 1 chronic condition, 2-3 chronic conditions, and persons with 4 or more of 12 chronic conditions examined. We compared differences in the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, hospital management practices, and in-hospital and post discharge outcomes within each of these three MCC strata using chi square tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. Subsequently, we excluded those individuals who died during the hospitalization for AMI from the study cohort to examine those at risk of developing outcomes of interest (n=301). To systematically examine the association between the number of MCCs and the risk of 30-day readmission to the hospital as well as one-year risk of death among patients discharged from participating central MA hospitals after their AMI, we used Cox proportional hazards modeling and adjusted for several potentially confounding demographic and clinical factors of prognostic importance. We ran unadjusted models first; in the second model, we adjusted for age and sex; and in the third model we adjusted for patient’s age, sex and type of AMI (STEMI vs. NSTEMI). These potential confounders were chosen based on findings from prior studies, on their statistically significant (p-value <=0.05) association with the principal study endpoints, and because of their clinical relevance.9–13

We estimated the overall prevalence of the five most common pairs of chronic conditions using a correlation matrix. Once the most frequent pairs of chronic conditions were determined, we examined their association with the risk of 30-day readmission to the hospital and 1-year risk of death among discharged hospital survivors using Cox proportional hazard models.

Results

A total of 3,294 patients were hospitalized with an independently validated AMI in this population-based investigation between 2005 and 2015. Of these patients, 583 (15.2%) had ≤1 chronic condition, 1,223 (31.8% ) had 2-3 chronic conditions, and 2,035 (53% ) had ≥4 chronic conditions. Overall, the average age of this study population was 67.9 years and 41.6% were women.

Patients with a greater number of MCCs, namely those with 2 or 3 conditions and those with 4 or more conditions, were more likely to be older, female, and experience a longer hospital stay as compared to those with ≤1 chronic condition (Table 1). Patients presenting the highest burden of MCCs were more likely to had a previous diagnostic or interventional procedure, namely PCI and CABG.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics according to multimorbidity burden.

| Characteristic | ≤1 chronic condition (n = 583) | 2-3 chronic conditions (n = 1,223) | 4 or more chronic conditions (n = 2,035) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (%) | ** | ||

| <55 | 35.3 | 22.1 | 11.0 |

| 55-64 | 26.0 | 24.1 | 14.8 |

| 65-74 | 16.9 | 19.7 | 22.7 |

| ≥ 75 | 21.7 | 34.0 | 51.6 |

| Age, years (mean) | 60.1 | 64.9 | 71.9** |

| Male | 71.2 | 60.1 | 53.8** |

| White race | 89.6 | 89.1 | 90.3 |

| Previous AMI | 10.1 | 30.4 | 45.3** |

| Length of stay (days, mean) | 3.8 | 4.4 | 5.8** |

| NSTEMI | 47.7 | 62.8 | 76.0** |

| Risk factors (%) | |||

| Hyperlipidemia | 25.9 | 76.0 | 75.3** |

| Hypertension | 20.9 | 83.6 | 88.07* |

| Medical history (%) | |||

| Anemia | 0.7 | 3.6 | 22.0** |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.4 | 7.4 | 21.1** |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.0 | 9.6 | 38.2** |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1.7 | 8.3 | 23.7** |

| Dementia | 0.7 | 3.4 | 12.1** |

| Depression | 3.8 | 12.6 | 23.1** |

| Diabetes | 3.1 | 25.9 | 53.1** |

| Heart failure | 0.9 | 5.8 | 38.5** |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0.9 | 9.3 | 31.7** |

| Stroke | 0.3 | 3.4 | 16.8** |

| Previous Interventional Procedures | |||

| Coronary artery bypass surgery | 6.2 | 9.2 | 5.3** |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 70.5 | 61.7 | 42.3** |

| Complications during hospitalization (%) | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 10.0 | 13.0 | 23.6** |

| Cardiogenic shock | 5.8 | 4.6 | 6.7 |

| Heart failure | 19.4 | 23.3 | 43.8** |

| Stroke | 0.4 | 1.1 | 1.6 |

Individuals presenting with a higher number of MCCs were more likely to have developed atrial fibrillation and heart failure during their index hospitalization for AMI as compared to those with the fewest number of MCCs. Approximately one in every five patients with 0-1 chronic condition, one in every four among those with 2 or 3 conditions, and one in every two patients with 4 or more conditions developed heart failure during their hospitalization for AMI.

The prescribing of the 4 effective cardiac medications during the patients’ index hospitalization for AMI in each of the MCC comparison groups was relatively similar, although a statistically significant difference was found in the prescribing of ACE inhibitors and aspirin. Those with a higher number of MCCs – 2 or 3 (70%) MCCs and those with 4 or more (70%) MCCs – were prescribed ACE inhibitors more often than those with ≤1 condition (66%). In contrast, the prescribing of aspirin during the patients’ acute hospitalization was significantly lower in those with 4 or more conditions (95%) as compared with those with ≤1 and those with 2 or 3 chronic conditions (98% and 97%, respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Interventional/Diagnostic procedures and in-hospital medication received during hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction according to multimorbidity burden.

| Characteristic | ≤1 chronic condition (n = 479) | 2-3 chronic conditions (n = 1,024) | 4 or more chronic conditions (n = 1,791) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic/Interventional Procedure (%) | |||

| Cardiac catheterization | 91.4 | 86.2 | 66.9** |

| Coronary bypass surgery | 6.6 | 9.1 | 5.9** |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 73.1 | 65.3 | 45.0** |

| Medication (%) | |||

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors /Angiotensin receptor blockers | 66.4 | 70.4 | 70.1* |

| Aspirin | 97.9 | 97.1 | 94.8* |

| Beta blockers | 93.5 | 94.1 | 93.8 |

| Lipid lowering | 92.5 | 92.2 | 81.0** |

| Antiarrhythmic | 8.0 | 9.5 | 11.7 |

The most common cardiac procedure performed in each group was cardiac catheterization, followed by PCI, and then CABG. As the number of chronic conditions increased across each MCC group, the receipt of each procedure decreased, with the exception of an increase in the receipt of CABG procedures between the group with ≤1 chronic condition and 4 or more conditions (6.6 and 5.9% respectively) and the group with 2-3 chronic conditions (9.1%) (Table 2).

Overall, 16% of individuals across all groups were readmitted to the hospital during the 30-days post-hospital discharge. The lowest frequency of readmissions occurred in the group with ≤1 chronic condition (9.8%) and the rates increased with an increasing number of MCCs (13.3% and 19.3% for those with 2-3 conditions and those with 4 or more conditions, respectively). After controlling for several potentially confounding factors, namely age, sex, and type of AMI (STEMI vs. NSTEMI), the risk for being readmitted to the hospital during the subsequent 30 days was 1.18 (95% CI1.01; 1.40) and 1.57 (95% CI 1.38; 1.84) for those with 2-3 chronic conditions and those with ≥4 chronic conditions, respectively, as compared to those with one or fewer conditions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Hazard ratios (unadjusted and adjusted HRs) for the risk of readmission to the hospital within 30-days after discharge from the hospital for acute myocardial infarction according to multimorbidity burden.

| 30-day readmission to hospital (Percentage of individuals who were readmitted: 16%) | Rate (%) | Unadjusted HR (95%CI) | Adjusted a HRs (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤1 chronic condition | 9.8 | Ref | Ref |

| 2-3 chronic conditions | 13.3 | 1.20 (1.02;1.40) | 1.18 (1.01;1.40) |

| 4 or + chronic conditions | 19.3 | 1.58 (1.36;1.83) | 1.57 (1.38;1.84) |

Adjusted for age, sex, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Overall, 22.5% of patients died within 1-year after hospital discharge across all MCC groups. After adjusting for several potential confounding factors of prognostic importance, the risk of dying within one-year of hospital discharge was 1.22 (95% CI 1.03; 1.44) for those with 2-3 chronic conditions and 1.19 (95% CI 1.01;1.40) for those with ≥4 chronic conditions, as compared to those with ≤1 chronic condition (Table 4).

Table 4.

Hazard ratios (unadjusted and adjusted HRs) for the risk of dying at 1-year post discharge from the hospital for acute myocardial infarction according to multimorbidity burden.

| Dying 1-year (Percentage of individuals who died within 1-year: 22.5%) | Rate (%) | Unadjusted HR (95%CI) | Adjusted a HRs (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤1 morbidity | 9.8 | Ref | Ref |

| 2-3 chronic conditions | 13.6 | 1.33 (1.13; 1.57) | 1.22 (1.03; 1.44) |

| 4 or + chronic conditions | 31.6 | 1.48 (1.26;1.72) | 1.19 (1.01; 1.40) |

Adjusted for age, sex, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

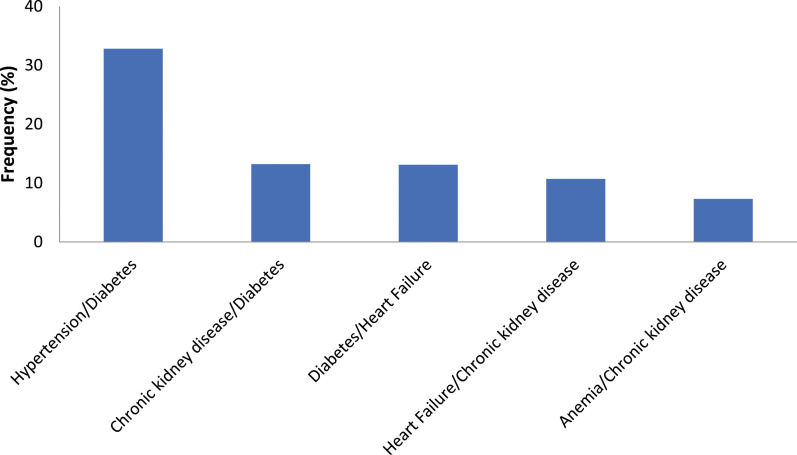

The five leading pairs of previously diagnosed chronic conditions (from most prevalent to least prevalent) were hypertension and diabetes; chronic kidney disease and diabetes; diabetes and heart failure; heart failure and chronic kidney disease, and anemia and chronic kidney disease (Figure 1). In terms of 30-day readmission to the hospital, patients with hypertension and diabetes were the most likely to be readmitted (adjusted hazard ratio (aHR): 1.38 (95% CI 1.14; 1.66), followed by those with previously diagnosed heart failure and chronic kidney disease (aHR:1.32 (95% CI 1.15;1.52)) as compared to those without these chronic conditions, respectively (Table 5).

Figure 1.

Top five pairs of chronic conditions in those who had an acute myocardial infarction.

Table 5.

Hazard ratios (unadjusted and adjusted HRs for the risk of readmission to the hospital within 30-days after discharge from the hospital for acute myocardial infarction according to top five pairs of chronic conditions.

| 30-day readmission to hospital | Rate (%) | Unadjusted HR (95%CI) | a Adjusted HRs (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension/Diabetes | 19.5 | 1.12 (1.03;1.23) | 1.38 (1.14;1.66) |

| Anemia/Chronic kidney disease | 22.7 | 1.47 (1.26;1.71) | 1.13 (1.03;1.25) |

| Chronic kidney disease/Diabetes | 24.2 | 1.34 (1.19;1.51) | 1.30 (1.12;1.43) |

| Heart Failure/Chronic kidney disease | 25.5 | 1.39 (1.22;1.59) | 1.32 (1.15;1.52) |

| Diabetes/Heart Failure | 26.4 | 1.28 (1.14;1.44) | 1.25 (1.10;1.41) |

Adjusted for age, sex, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Comparison group for each model are those without the pair of chronic conditions.

Somewhat similar trends were found for the risk of dying within one-year after hospital discharge for AMI. Patients who had been previously diagnosed with diabetes and chronic kidney disease had the greatest risk of dying within one-year (aHR: 2.11 (95% CI 1.86; 2.40)), followed by those who had been previously diagnosed with diabetes and heart failure (aHR:1.95 (95% CI 1.71; 2.21)) as compared to those without these chronic conditions, respectively (Table 6).

Table 6.

Hazard ratios (unadjusted and adjusted HRs) for the risk of dying at 1-year post discharge from the hospital for acute myocardial infarction according to top five pairs of chronic conditions.

| Dying 1-year | Rate (%) | Unadjusted HR (95%CI) | a Adjusted HRs (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension/Diabetes | 27.4 | 1.67 (1.52; 1.83) | 1.58 (1.43;1.73) |

| Chronic kidney disease/Diabetes | 39.0 | 2.17 (1.92;2.46) | 2.11 (1.86; 2.40) |

| Diabetes/Heart Failure | 40.8 | 2.11 (1.71;2.38) | 1.95 (1.71;2.21) |

| Heart Failure/Chronic kidney disease | 49.4 | 1.95 (1.69;2.25) | 1.74 (1.50;2.02) |

| Anemia/Chronic kidney disease | 50.0 | 1.66 (1.41;1.96) | 1.51 (1.28;1.79) |

Adjusted for age, sex, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Comparison group for each model are those without the pair of chronic conditions.

Discussion

In this population-based study of adults hospitalized with AMI at all three major medical centers serving residents of the Worcester metropolitan area, we found that patients with a higher number of MCCs tended to be older, were more likely to be women, experienced a longer length of stay in hospital, underwent significantly fewer interventional procedures, and had poorer short and long-term outcomes. We observed an increased risk for 30-day hospital readmission according to the presence of MCCs, with the highest risk observed for these outcomes in patients with 4 or more chronic conditions. Finally, patients with diabetes/heart failure and those with diabetes/chronic kidney disease were at the highest risk for dying within a year of index hospitalization, and those with hypertension and diabetes and heart failure/chronic kidney disease were at higher risk for readmission to the hospital, respectively.

We found that patients with a greater number of MCCs tended to be women and older, experienced a longer hospital stay, and were more likely to have been previously diagnosed with an AMI. Similar to our findings, patients (n = 9,566) hospitalized with an AMI at 77 national health service hospitals in England between 2011 and 2015 were grouped into three strata using latent class analysis to identify clusters based on number of MCCs – Mild, Moderate, and Severe. Those in the severe group included the largest proportion of older adults, women, and patients who had previously experienced an AMI. 17 These data suggest that the patients with a greater number of MCCs have a more complex profile than patients with fewer chronic conditions, making their management more complex and challenging.

Our data suggest decreasing rates of cardiac procedures, namely cardiac catheterization and PCI, as the number of chronic conditions increased; the frequency of coronary bypass surgery was lowest in the group with ≥4 chronic conditions.

Despite having received fewer cardiac interventional procedures, patients with 4 or more chronic conditions were treated similarly in the hospital with effective cardiac medications as those with fewer chronic conditions, consistent with previous findings. In a prior investigation of our study population who were hospitalized with AMI in 2003, 2005, and 2007, we found a similar reduction in the use of evidence-based interventions in those with a higher number of chronic conditions, but similar rates of in-hospital medication use across all groups. 6 Similarly, in a population-based cohort of more than 100,000 patients hospitalized with AMI between 2012 and 2018 in Switzerland, the number of MCCs was inversely associated with the receipt of PCI. Over 60% of those with the lowest number of conditions (Charlson: 1.42) received a PCI, as compared to 36% of those with the highest number of conditions (Charlson: 2.81). 2 Among nearly 1,000 patients hospitalized with a STEMI in 53 Ontario hospitals in 2006, the likelihood of being treated with coronary reperfusion therapy fell by 18% for each additional pre-existing condition present at the time of hospital admission. 18 Lastly, researchers in the United Kingdom used data from more than 693,000 patients in the Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP) to investigate the association of number of MCCs with the receipt of “optimal care” during hospitalization for AMI. 19 There was a high use of ACE-Is/ARBs and aspirin during hospitalization, regardless of the number of chronic conditions previously diagnosed, and reduced use of an invasive coronary strategy for those with comorbidities compared to those without. Overall, the presence of each chronic condition, with the exception of hypertension, renal failure, and peripheral vascular disease, was associated with a lower likelihood of receiving optimal hospital care. 19

There are a number of potential explanations for the treatment patterns observed in individuals with a higher number of MCCs. These include the physicians’ perception of treatment as being more difficult in this complex and sicker population, and that patients with a higher number of MCCs may develop a greater number of adverse reactions due to interactions between their chronic conditions and various treatment practices. Unfortunately, present management guidelines often exclude patients with multiple chronic conditions and in consequence, healthcare providers struggle with using treatments that may not be beneficial and that could cause harm to individuals with MCCs, versus denying effective treatments to patients at high risk for adverse outcomes who could benefit from more aggressive management. 8

Shared-decision making between patients and providers is paramount in meeting the goals of care in patients with AMI and MCCs. Patients must understand the risks and benefits of proceeding with treatment and the consequences of deferring active management, as well as the importance of adherence to medications after AMI. A longitudinal study of more than 2,000 patients hospiatlzied with an acute coronary syndrome at six medical centers in Massachusetts and Georgia showed that patients with MCC’s tended to have lower health literacy and were more likely to be cognitively impaired than patients with ≤ 1 chronic condtion. 20 This further suggests the need to improve patient education in this at risk population and meet the goals of patient care.

Evidence-based care for AMI has been primarily driven by the results of carefully conducted randomized controlled clinical trials, in which a single disease is generally targeted and other chronic conditions are excluded. 7 There is a clear need to include this complex population in clinical trials in order to guide healthcare providers in the management of patients with AMI and MCCs, and improve their clinical outcomes. It remains incumbent upon the cardiovascular research community to develop guidelines for how to best treat these complex high risk patients and improve their short and long-term prognosis.

Our findings suggest a higher risk of 30-day readmission to the hospital and death within 1-year of discharge from the hospital, particularly in patients with ≥4 chronic conditions as compared to those with <=1 chronic condition. In the previously referenced Swiss study of more than 100,000 admissions for AMI between 2012 and 2018, the investigators found an increased risk of hospital readmission with each additional chronic condition present. 2

In a previous publication of nearly 10,000 patients hospitalized with a confirmed AMI in the Worcester Heart Attack Study between 1990 and 2007, we observed an increased risk of dying during the first month and first year following hospital discharge as the number of chronic conditions increased. 4 In the previously described United Kingdom study using MINAP, suboptimal in-patient care resulted in decreased survival at all times after discharge, with the greatest survival reduction occurring in those with the highest number of chronic conditions. 19

Our findings suggest that patients with diabetes/hypertension had the highest risk of 30-day readmission, while those with diabetes/chronic kidney disease had the greatest risk of dying during the first year post-hospitalization.

Our findings with regards to the association of diabetes/hypertension and high risk of hospital readmission are of particular interest due to the high prevalence of diabetes in the United States. Individuals with diabetes have an increased risk of atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease, as well as diastolic dysfunction and diabetic cardiomyopathy, all contributing to the development of heart failure. Data from the 2014 US Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) showed that patients with diabetes had a 45% higher risk of being rehospiatlzied for heart failure after an AMI as compared to those without diabetes. 21

Much of the available literature that has described the most prevalent dyads of chronic conditions in those hospitalized with an AMI come from prior investigations of our study population. For example, among more than 2,900 patients hospitalized with an AMI at central Massachusetts medical centers during 2003, 2005, and 2007, the two most frequent pairs of cardiac related conditions were coronary heart disease/hypertension (11.4%) and diabetes/hypertension (6.1%). The two most frequent pairs of non-cardiac related conditions were anemia/chronic kidney disease (3.5%) and COPD/ chronic kidney disease (2.0%). 6 Among 1,564 patients with an initial AMI during the study years of 2005, 2011, and 2015, hypertension and hyperlipidemia were the most prevalent pair of chronic conditions followed by anemia/chronic kidney disease and chronic kidney disease/heart failure. 22

The strengths of this study are largely derived from its population-based design that captured the vast majority of cases of AMI that occurred among residents of central MA between 2005 and 2015. However, there are several limitations to be cognizant of in interpreting the present results. First, data on chronic conditions were abstracted from hospital records and we were unable to collect additional information about the severity, duration, or extent of each of the chronic conditions under study. The majority of our study population was Caucasian, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other ethnic groups. There was a dearth of information on several characteristics associated with this patient population (e.g. socioeconomic status, functional status, and cognitive impairment) which may have confounded the observed associations. Lastly, follow up data on health outcomes other than short and long-term readmission and death were not available to the study team, which may reflect unmeasured factors that may have developed after hospital discharge and potentially confound the outcomes under study.

An increasing prevalence of heart disease and chronic conditions coupled with an aging population presents a complicated paradigm in the management of patients with acute coronary disease. The results of our study suggest that MCCs are highly prevalent among patients experiencing an AMI, particularly in older patients, and the presence of MCCs affect the care that these patients receive and their short and long-term morbidity and mortality. Future research should be focused on the optimal management of patients hospitalized with an AMI and MCCs. It is crucial to develop guidelines that include these high risk and complex patients. It is particularly important that investigations are targeted towards patients with the most common chronic conditions, and those who may be at increased risk for recurrent hospitalization and mortality.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Short and medium-term outcomes in individuals hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction and multiple chronic conditions: The Worcester heart attack study by Christopher Zammitti, Mayra Tisminetzky, Jordy Mehawej, Hawa O Abu, Ruben Miozzo, Joel M Gore, Darleen Lessard, Benita A Bamgbade, Jorge Yarzebski, Jerry H Gurwitz, and Robert J Goldberg in Journal of Multimorbidity and Comorbidity

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging, R01AG062630, R33AG057806, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, R01HL35434, U01HL105268.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School IRB to carry out the Worcester Heart Attack Study with a HIPAA IRB WAIVER OF AUTHORIZATION WHAS DOCKET 458.

ORCID iDs

Christopher Zammitti https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4193-9674

Mayra Tisminetzky https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8557-2029

Ruben Miozzo https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8005-7730

References

- 1.Tisminetzky M, Goldberg R, Gurwitz JH. Magnitude and Impact of Multimorbidity on Clinical Outcomes in Older Adults with Cardiovascular Disease: A Literature Review. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32(2):227-246. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2016.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baechli C, Koch D, Bernet S, Gut L, Wagner U, Mueller B, Schuetz P, Kutz A. Association of comorbidities with clinical outcomes in patients after acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2020. Jun 10;29:100558. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2020.100558. PMID: 32566721; PMCID: PMC7298557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tisminetzky M, Gurwitz JH, Fan D, Reynolds K, Smith DH, Magid DJ, Sung SH, Murphy TE, Goldberg RJ, Go AS. Multimorbidity Burden and Adverse Outcomes in a Community-Based Cohort of Adults with Heart Failure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(12):2305-2313. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McManus DD, Nguyen HL, Saczynski JS, Tisminetzky M, Bourell P, Goldberg RJ. Multiple cardiovascular comorbidities and acute myocardial infarction: temporal trends (1990-2007) and impact on death rates at 30 days and 1 year. Clin Epidemiol. 2012;4:115-123. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S30883. Epub 2012 May 7. PMID: 22701091; PMCID: PMC3372969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murad K, Goff DC, Jr, Morgan TM, Burke GL, Bartz TM, Kizer JR, Chaudhry SI, Gottdiener JS, Kitzman DW. Burden of Comorbidities and Functional and Cognitive Impairments in Elderly Patients at the Initial Diagnosis of Heart Failure and Their Impact on Total Mortality: The Cardiovascular Health Study. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3(7):542-550. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen HY, Saczynski JS, McManus DD, Lessard D, Yarzebski J, Lapane KL, Gore JM, Goldberg RJ. The impact of cardiac and noncardiac comorbidities on the short-term outcomes of patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: a population-based perspective. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5:439-448. Published 2013 Nov 7. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S49485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyd CM, Leff B, Wolff JL, Yu Q, Zhou J, Rand C, Weiss CO. Informing clinical practice guideline development and implementation: prevalence of coexisting conditions among adults with coronary heart disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(5):797-805. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03391.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forman DE, Maurer MS, Boyd C, Brindis R, Salive ME, Horne FM, Bell SP, Fulmer T, Reuben DB, Zieman S, Rich MW. Multimorbidity in older adults with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 71:2149-2161. PMID: 29747836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, Alpert JS, Dalen JE. Recent changes in attack and survival rates of acute myocardial infarction (1975 through 1981): The Worcester Heart Attack Study. JAMA 1986; 255: 2774–2779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, Alpert JS, Dalen JE. Incidence and case fatality rates of acute myocardial infarction (1975–1984): The Worcester Heart Attack Study. Am Heart J 1988; 115: 761–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg RJ, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Gore JM. A two-decade (1975 to 1995) long experience in the incidence, in-hospital and long-term case-fatality rates of acute myocardial infarction: a community-wide perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1533-1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Floyd KC, Yarzebski J, Spencer FA, Lessard D, Dalen JE, Alpert JS, Gore JM, Goldberg RJ. A 30-year perspective (1975-2005) into the changing landscape of patients hospitalized with initial acute myocardial infarction: Worcester Heart Attack Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2: 88-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McManus DD, Gore J, Yarzebski J, Spencer F, Lessard D, Goldberg RJ. Recent trends in the incidence, treatment, and outcomes of patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. Am J Med. 2011;124:40-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.2012 Writing Committee Members. Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS, Adams CD, Bridges CR, Casey DE, Jr, Ettinger SM, Fesmire FM, Ganiats TG, Lincoff AM, Peterson ED, Philippides GJ, Theroux P, Wenger NK, Zidar JP, Anderson JL; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2012. Aug 14;126(7):875-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE, Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM, Franklin BA, Granger CB, Krumholz HM, Linderbaum JA, Morrow DA, Newby LK, Ornato JP, Ou N, Radford MJ, Tamis-Holland JE, Tommaso CL, Tracy CM, Woo YJ, Zhao DX, Anderson JL, Jacobs AK, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Brindis RG, Creager MA, DeMets D, Guyton RA, Hochman JS, Kovacs RJ, Kushner FG, Ohman EM, Stevenson WG, Yancy CW; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013. Jan 29;127(4):e362-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fortin M, Stewart M, Poitras ME, Almirall J, Maddocks H. A systematic review of prevalence studies on multimorbidity: toward a more uniform methodology. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(2):142-151. doi: 10.1370/afm.1337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munyombwe T, Dondo TB, Aktaa S, Wilkinson C, Hall M, Hurdus B, Oliver G, West RM, Hall AS, Gale CP. Association of multimorbidity and changes in health-related quality of life following myocardial infarction: a UK multicentre longitudinal patient-reported outcomes study. BMC Med. 2021. Sep 28;19(1):227. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-02098-y. PMID: 34579718; PMCID: PMC8477511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker AB, Naylor CD, Chong A, Alter DA; Socio-Economic Status and Acute Myocardial Infarction Study Group. Clinical prognosis, pre-existing conditions and the use of reperfusion therapy for patients with ST segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22(2):131-139. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70252-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yadegarfar ME, Gale CP, Dondo TB, Wilkinson CG, Cowie MR, Hall M. Association of treatments for acute myocardial infarction and survival for seven common comorbidity states: a nationwide cohort study. BMC Med 18, 231 (2020). doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01689-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tisminetzky M, Gurwitz J, McManus DD, Saczynski JS, Erskine N, Waring ME, Anatchkova M, Awad H, Parish DC, Lessard D, Kiefe C, Goldberg R. Multiple Chronic Conditions and Psychosocial Limitations in Patients Hospitalized with an Acute Coronary Syndrome. Am J Med. 2016;129(6):608-614. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.11.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yandrapalli S, Malik AH, Namrata F, Pemmasani G, Bandyopadhyay D, Vallabhajosyula S, Aronow WS, Frishman WH, Jain D, Cooper HA, Panza JA. Influence of diabetes mellitus interactions with cardiovascular risk factors on post-myocardial infarction heart failure hospitalizations. Int J Cardiol. 2022. Feb 1;348:140-146. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.11.086. Epub 2021 Dec 2. PMID: 34864085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tisminetzky M, Miozzo R, Gore JM, Gurwitz JH, Lessard D, Yarzebski J, Granillo E, Abu HO, Goldberg RJ. Trends in the magnitude of chronic conditions in patients hospitalized with a first acute myocardial infarction. J Comorb. 2021 Mar 3;11:2633556521999570. doi: 10.1177/2633556521999570. PMID: 33738263; PMCID: PMC7934031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Short and medium-term outcomes in individuals hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction and multiple chronic conditions: The Worcester heart attack study by Christopher Zammitti, Mayra Tisminetzky, Jordy Mehawej, Hawa O Abu, Ruben Miozzo, Joel M Gore, Darleen Lessard, Benita A Bamgbade, Jorge Yarzebski, Jerry H Gurwitz, and Robert J Goldberg in Journal of Multimorbidity and Comorbidity