Abstract

CRISPR/Cas-based gene-editing technologies have emerged as one of the most transformative tools in genome science over the past decade, providing unprecedented possibilities for both fundamental and translational research. Following the initial wave of innovations for gene knock-out, epigenetic/RNA modulation, and nickase-mediated base-editing, recent efforts have pivoted towards long-sequence gene editing— specifically, the insertion of large fragments (>1 kb) into the endogenous genome. In this review, we survey the development of these CRISPR/Cas-based sequence insertion methodologies in conjunction with the emergence of novel families of editing enzymes, such as transposases, single-stranded DNA-annealing proteins, recombinases, and integrases. Despite facing a number of challenges, this field continues to evolve rapidly and holds the potential to catalyze a new wave of revolutionary biomedical applications.

Keywords: CRISPR/Cas9, Genome editing, Large fragment knock-in, Transposase, Recombinase, Genomic insertion

Introduction

Over the past decade, genome editing techniques have advanced exponentially [1–4]. The successive discoveries of zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) [5], transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) [6–8], and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) have broadened the scope of genome modification applications in biological research. These tools have extended the reach from in vitro to in vivo studies due to their simplicity, flexibility, efficiency, and economically feasible engineering [1,2,9,10].

Despite these nuclease-mediated genome editing technologies unlocking the potential for precise and efficient genetic research, large fragment (>1 kb) knock-ins remain one of the most challenging types of gene editing [11,12]. Large fragment knock-ins play a significant role in fields ranging from fundamental research to translational medicine, agriculture, and animal husbandry. Historically, Cas9 nuclease-based methods have been the primary tools for knock-in gene editing. Traditional CRISPR/Cas9 systems exploit one of three types of DNA repair mechanisms: homology-directed repair (HDR), nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ), and microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ). After Cas9 induces a DNA break in dividing cells, HDR and MMEJ can occur during the late S/G2 phase and M-early S phase, respectively. If a donor template with an extended homology sequence (usually >50bp) is available, HDR functions as a precise, albeit inefficient, repair process that can potentially be used for gene knock-in. Conversely, when short microhomologies (usually <50bp) exist, the two microhomologies flanking the break site can be annealed via MMEJ, which has also been harnessed for gene knock-in [13]. In non-dividing cells, which are most relevant for therapeutic applications, and in the absence of an adjacent homology donor, NHEJ is the predominant DNA repair mechanism. During NHEJ, both ends of DNA strands rejoin and tolerate a diverse range of base changes, which can be utilized in homology-independent gene knock-in strategies [14]. However, these strategies may result in imprecise insertions or deletions with substantial indel errors. Their efficiencies also vary greatly depending on cell type, which has motivated further research into the discovery and optimization of more reliable gene insertion techniques.

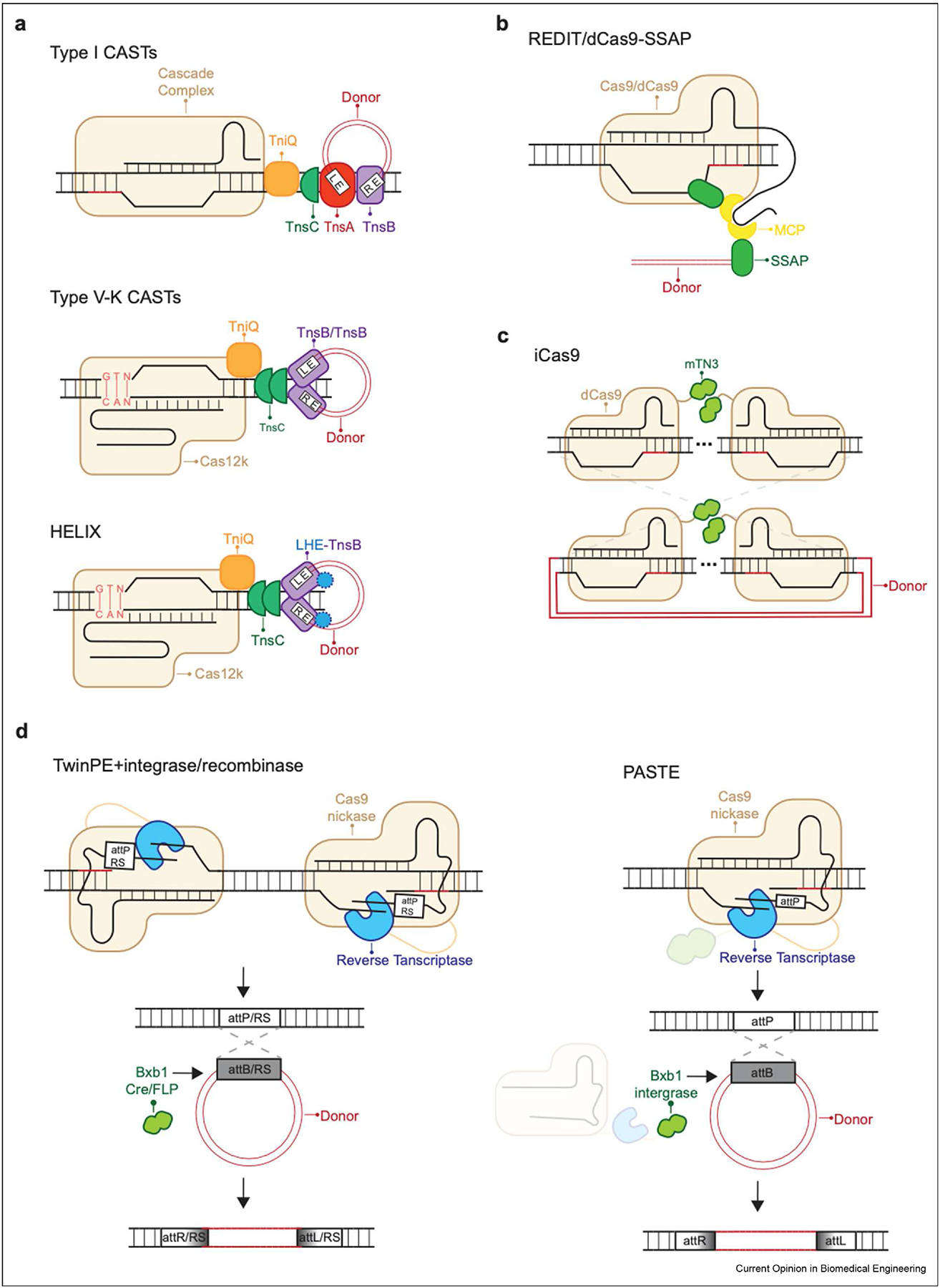

The ideal large-sequence insertion technique should be compact, scarless, and operate independently of endogenous DNA repair mechanisms. Moreover, it should generate efficient, programmable, unidirectional, and pure insertion products. In this review, we summarize the recently developed CRISPR techniques for long-sequence genome insertion. These methods are exemplified by: (1) the transposon-encoded CRISPR/ Cas system; (2) the phage-encoded single-stranded DNA-annealing protein (SSAP) editor coupled with CRISPR/Cas9 and/dCas9 (deactivated Cas9); and (3) recombinase/integrase with Prime Editing and dCas9 (Figure 1). We review these newly developed tools for improving editing efficiency at precise locations, with a particular focus on large fragment (>1 kb) knock-in. We also discuss the application of these tools as well as challenges and future directions in this exciting field (features of each system summarized in Table 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of approaches for long sequence insertion via CRISPR/Cas. Programmable long sequence insertion with (a) type I and V–K CRISPR-associated transposases (CAST) and HELIX; (b) phage single-stranded DNA-annealing proteins (SSAPs); (c) integrase mTN3-fused Cas9 (iCas9); and (d) prime editing-based insertion of a landing pad prior to integrase/recombinase-catalyzed donor insertion. Landing pads can be attachment sites (AttB or AttP) or recombinase recognition sites (RS), and must be present in the donor sequence as well.

Table 1.

Features of CRISPR/Cas-based techniques for long sequence insertion.

| Category | Tool | Efficiency | Size of insertion | Off-target concerns | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transposon-encoded CRISPR/Cas systems | shCAST | Up-to 80% (E. coli) | ≤ 10 kb | Possibility of Cointegration (cargo duplication and full plasmid backbone insertion) | Short cargo-flanking sequence remnant Delivery of multiple components and DNA donor |

| INTEGRATE | ~100% (Bacteria) ~1% (HEK293T cell with ClpX) | ≥ 10 kb | Potential bidirectional insertion | Short cargo-flanking sequence remnant Delivery of multiple components and DNA donor |

|

| HELIX | Higher than INTEGRATE (Bacteria) 0.04% (HEK293T cell-based plasmid) | ≥ 10 kb | Minimized possibility of Cointegration (cargo duplication and full plasmid backbone insertion) | Delivery of multiple components and DNA donor | |

| SSAP-editor coupling with CRISPR/Cas9 and -dCas9 | REDIT | Up to 15% (A549, HepG2, HeLa); 5% (hESC) | ≥ 2 kb | Potential Cas9 off-target, potential off-target insertion of cargo | Requiring endogenous DNA repair Delivery of DNA donor On-target indel/error. |

| dCas9-SSAP | Up to 20% | ≥ 2 kb | Potential off-target insertion of cargo | Affected by endogenous DNA repair Delivery of DNA donor |

|

| Recombinase/integrase with Prime editing or Cas9 | TwinPE/GRAND editing | 2.6–6.8% (Human cells) | Up to 5.6 kb | Potential off-target insertion of landing pads that may lead to cargo insertion | Short cargo-flanking sequence remnant Requiring endogenous DNA repair Delivery of multiple component and DNA donor On-target indel/error |

| PASTE | 50~60% (Human cell lines); 4~5% (Primary human hepatocytes and T cells) | ≤ 36 kb | Potential off-target insertion of landing pads that may lead to cargo insertion | Short cargo-flanking sequence remnant Requiring endogenous DNA repair Delivery of multiple component and DNA donor On-target indel/error |

|

| PrimeRooot | 6.3% (Kitaake rice) | Up to 11.1 kb | Potential off-target insertion of landing pads that may lead to cargo insertion | Short cargo-flanking sequence remnant Requiring endogenous DNA repair Delivery of multiple component and DNA donor On-target indel/error |

|

| iCas9 | ~9.4 folds increase over non-targeting control (HEK293T) | Up to 1 kb | Potential recombinase off-target interaction that may lead to off-target cargo insertion | Delivery of DNA donor |

Transposon-encoded CRISPR/Cas systems as genomic insertion tools

Transposons are mobile genetic elements that can move from one location to another within a host genome and have harnessed CRISPR systems for mobility (Figure 1a). The core components of a typical transposon include a left end (LE) sequence, right end (RE) sequence, and a central cargo gene encoding a transposase. The transposase is expressed and subsequently binds to the LE and RE to form a complex. This complex is excised from the donor DNA strand and inserted into a new location specified by the transposase. Transposon-encoded CRISPR/Cas systems, such as Tn7 or Tn5053-like transposons, co-opt type I or type V CRISPR/Cas systems for genetic element mobilization [15]. Tn7-like transposons contain two transposase proteins, TnsA and TnsB, which regulate the cleavage of the 5′ and 3′ ends of the transposable element sequences, respectively. These transposases cooperate to insert the cargo into a target site identified by either of its two sequence-specific DNA binding proteins: TnsD, which targets the highly specific attTn7 sequence, and TnsE, which recognizes features of replicating DNA. TnsC mediates communication between the two transposases and binding proteins [16]. In contrast, Tn5053-like transposons lack TnsA, so only 3’ nicking occurs [17].

Recently, a CRISPR-associated transposase was characterized from cyanobacteria Scytonema hofmanni (ShCAST) that consists of Tn7-like transposase subunits and the type V–K CRISPR effector (Cas12k) [18]. ShCAST can insert cargo DNA up to 10 kb in length at 60–66 base pairs downstream of the protospacer. Out of the 48 tested target sites in the Escherichia coli genome, 29 were successfully transposed, indicating a successful insertion rate of ~60%. While the transposition of ShCAST is specific, it can also integrate at non-targeted sites under overexpression conditions. This off-target insertion is Cas12k independent and favors highly expressed genes. Furthermore, ShCAST can generate a mixture of simple insertion and cointegrate gene products, consisting of cargo duplication and full plasmid backbone insertion [18,19]. To overcome the limitations of a high off-target rate and low insertion purity, a nicking homing endonuclease fusion to TnsB, named HELIX, was engineered to restore the 5’ nicking capability needed for cargo excision on the DNA donor [20]. HELIX enables cut-and-paste DNA insertion with up to 99.4% simple insertion product purity, while retaining robust integration efficiencies on genomic targets. It was also demonstrated that HELIX exhibited an on-target specificity 34% higher than its derived CAST, and that Cas12k fusions and/or pi protein co-expression can further reduce off-target integration [20].

Another Type I–F CRISPR effector-based Tn-7-like transposon system was recently described, showing the ability to Insert Transposable Elements by Guide RNA-Assisted TargEting (INTEGRATE) [21]. In this system, the CRISPR/Cas effector complex (the pQCascade plasmid, which encode CRISPR arrays, Cascade, and TniQ) from Vibrio. cholerae directs an accompanying transposase (auxiliary plasmids that encode TnsA, TnsB, and TnsC) to integrate DNA downstream of a genomic target site. The donor plasmid encodes the DNA substrate LE-cargo-RE, and the cargo is inserted 47–51 bp downstream of the protospacer, forming a 5 bp duplication sequence on the flanks of the insertion sequence. Even though the optimal length of genetic cargo for this Tn7-like transposon is 775 bp, it can successfully transpose cargo genes of up to 10 kb, indicating its potential for large-scale gene integration. It demonstrated an off-target efficiency of less than 5%, and the off-target sites were not biased [21]. However, the uncontrollable direction of transposon insertion reduces the precision of INTEGRATE in gene therapy applications. Moreover, this system requires multiple cumbersome genetic components and displays low efficiency for larger insertions. Thus, an improved version was developed, using streamlined expression vectors to increase the editing efficiency 2–5 times and achieve ~100% efficiency of targeted insertion of DNA fragments up to 10 kb in length [22]. Results show that although bidirectional transposition can also be detected with the improved INTEGRATE, the insertion events near the RE of the transposon at the target site (T-RL) show a significantly stronger bias, and there are no non-targeted insertion events. As the improved INTEGRATE does not require specific homologous arms, it is easier to achieve multi-target integration of cargos in one step. Currently, it can achieve 99% efficiency in inserting genes into three target sites simultaneously. However, each target site needs to be spaced at least 1 Mb apart [22].

Programmable SSAP-editor with CRISPR system via Cas9 or dCas9

Phage-encoded single-stranded DNA-annealing proteins (SSAPs) are enzymes that perform precise recombination in prokaryotes. Notably, they have also been discovered in viruses, such as the human Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 (HSV-1) [23]. SSAPs integrate nucleic acid donors without nicking or breaking the genome, thereby preserving the integrity of the host genome while achieving multi-kilobase genome recombineering [24]. The SSAPs can work in a sequence-independent manner, which allows them to function across a wide range of species and genetic contexts.

The discovery of SSAPs has opened a new avenue for genome engineering, especially for the insertion of long DNA sequences (Figure 1b). To realize this potential and extend its application to mammalian gene editing, researchers developed a system titled “RecT Editor via Designer-Cas9-Initiated Targeting (REDIT)” by coupling the phage SSAP RecTwith a programmable Cas9 [25]. The RecT enzyme is a recombinase originally encoded by bacteriophages, and facilitates homologous recombination in the bacterial host. The utility of the REDIT system comes from the fact that RecT can guide the insertion of a kilobase-scale DNA sequence at a specific genomic location dictated by the Cas9 guide RNA. The REDIT system has exhibited efficiencies up to five times higher than those of Cas9 alone when using different donor DNAs at various insertion sizes [25]. However, the use of the Cas9 nuclease in the REDIT system can lead to random indel formation following DNA cutting, which is a significant limitation in terms of maintaining genomic integrity.

To overcome this limitation, another editor was developed, which is based on dCas9, a catalytically inactive form of the Cas9 nuclease. This system, termed the dCas9-SSAP editor, offers the targeting specificity of the CRISPR/Cas9 system without the DNA cleavage activity, thus minimizing potential DNA damage [26]. The dCas9-SSAP editor enables kilobase-scale long-sequence insertion with minimal DNA damage and errors. The reported efficiency of this system is as high as 20% across various donor designs and cell types. Most importantly, unlike REDIT, the dCas9-SSAP editor does not introduce any detectable off-target insertions, providing highly precise genome editing [26]. Notably, the scalability and efficiency of the dCas9-SSAP editor make it a promising tool for myriad applications ranging from fundamental research to therapeutic development.

Recombinase/integrase with prime editor or Cas9 nuclease

Site-specific integrases have been recognized as valuable genome engineering tools, even facilitating long read insertions of up to 27 kb in mammalian cells [27]. To direct these integrases to specific loci, engineered systems have been created by fusing zinc fingers [28], transcription activator-like effectors [29], or dCas9 programmable DNA-binding proteins [30] to integrases. These systems have been evaluated in mammalian cells, but their integration efficiency has been limited until recent developments leveraging the CRISPR system (Figure 1c and d).

As a powerful CRISPR based gene editing tool, prime editing (PE) employs a fusion protein that contains a catalytically impaired Cas9 nickase and a reverse transcriptase (RT) enzyme, along with a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA). The pegRNA both specifies the target genomic site and encodes the desired edit [31]. Building on this approach, the Twin prime editing (TwinPE) system uses two pegRNAs, with either fully or partially complementary templates for the same edit, to perform genetic modification at targeted locations within the human genome [32]. When combined with the serine integrase Bxb1, TwinPE successfully integrated a 5.6-kb DNA donor plasmid into the genomes of human cells at AAVS1, CCR5, and ALB with efficiencies of 6.8%, 6.1%, and 2.6%, respectively [32].

A novel system, known as Programmable Addition via Site-specific Targeting Elements (PASTE), was recently shown to achieve high-efficiency insertion of even larger sequences than those possible with TwinPE [33]. This system combines prime editing with the serine integrase Bxb1. By fusing Cas9, reverse transcriptase, and large serine integrase together, PASTE achieved programmable integration of cargos up to ~36 kb in a single delivery reaction, with efficiencies reaching high double-digits in cell lines and ~4–5% in primary human hepatocytes and T cells [33].

Besides TwinPE and PASTE, another prime editing-based PrimeRoot system (Prime editing-mediated Recombination Of Opportune Targets) was introduced by Sun et al. and combined plant-optimized recombinases and enchanced plant PE to create targeted DNA insertions. PrimeRoot is capable of efficiently inducing recombinase site insertion events in rice at frequencies approaching 50%, and PrimeRoot can be used to precisely insert DNA segments of up to 11.1 kb into the rice genome [34].

Cas9 has also complemented the utility of recombinases and integrases, particularly for site-specific large-sequence insertion. A dCas9 fused with a hyperactive mutant recombinase from transposon Tn3, a member of the serine recombinases, enables targeted integration into endogenous genomic loci in HEK293 cells [35]. This system, called iCas9, boasts an efficiency approximately 9.4-fold higher than the non-targeting control [35].

Applications of CRISPR-based tools for long sequence insertion

The CRISPR/Cas system has been widely utilized for the integration of large DNA fragments into genomes, with significant advancements particularly observed in the last two years. Besides the aforementioned tools, SLEEK (Selection by essential-gene exon knock-in) could achieve knock-in efficiencies of more than 90% in clinically relevant cell types [36]. SLEEK utilized AsCas12a that targets a site within an exon of an essential gene, and a cargo template with which the correct knock-in would retain essential gene function while also integrating the transgene of interest. This method offers researchers a means to rapidly test different transgene cargos, driving high-level transgene knock-in and expression of clinically relevant cargos across clinically relevant cell types [36].

Among the above reviewed tools, CRISPR-associated transposons have mainly been studied in a few prokaryotes and have recently been engineered to work in mammalian cells with relatively moderate efficiencies, which indicate that further effort is required to harness their potential in genome engineering applications. SSAP-based tools were tested in different human cell lines with distinctive tissue origins (cervix-derived HeLa cells, liver-derived HepG2 cells and bone-derived U2OS cells), and researchers also reported successful sequence insertion in therapeutically relevant sites such as AAVS1 with human embryonic stem cells. TwinPE was used to correct a large sequence inversion associated with Hunter syndrome in human cells with up to ~9% efficiency. PASTE was shown with versatility for gene tagging, gene replacement, gene delivery and protein production and secretion. PrimeRoot was tested to integrate a gene cassette into a predicted genomic safe harbor site of Kitaake rice, with an observed increase of blast resistance. These findings indicate the promising application of abovementioned tools in clinical therapeutics, agriculture, and potentially, animal husbandry.

Most importantly, these long-sequence editors have significant implications for the development of therapeutics. The ability to insert full exons or entire genes can offer curative benefits to patients with individualized mutations, regardless of the location of their underlying genetics, exemplified by conditions like Phenylketonuria (PKU) and Fanconi Anemia (FA). For disorders like Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency (AATD) that require replacement of malfunctioning genes, these tools could work synergistically with RNAi/ASO/Knock-out gene therapies. Peering into the future, we envision the insertion of peptide/antibody drugs (biologics) or corresponding therapeutic cassettes sparking transformative methodologies for a wide range of diseases, including common diseases and various types of cancer. This could catalyze groundbreaking progress in in vivo generation of immunotherapies and T-cell, NK-cell therapies. Furthermore, the development of sophisticated tools such as PrimeRoot underscores the potential of these editing systems in synthetic biology, environmental engineering, and agricultural industries. These advancements hint at a future where precision gene-editing technologies could be widely applied across numerous fields, revolutionizing our approach to health and environmental challenges.

Challenges and future directions

Despite notable progress, current CRISPR-based genome insertion editors still have limitations, warranting further investigation and development (Table 1). Within the context of gene therapy, transposon-encoded CRISPR/Cas systems continue to encounter hurdles such as editing efficiency, deliverability, and translatability from bench to bedside. Single-Stranded DNA-Annealing Protein (SSAP) editors, although compact in size and conducive to convenient delivery into cells (both in vitro and in vivo), grapple with issues such as relatively low insertion efficiencies, linear donor template requirements, and poorly-understood functional mechanisms. These challenges must be addressed for their full potential to be realized in translational development. Prime editing-based tools, such as TwinPE-integrase and PASTE, have their own limitations. They leave undesirable sequence scars from recombined sites in gene insertion products. These scars, together with potential nickase-mediated indels, are likely to limit the application of these systems to safe harbor loci, increasing the risk that scar insertion could have unintended consequences. Furthermore, the large coding sequences required by many of these tools, along with the need for multiple sgRNAs or pegRNAs, can impose constraints on delivery due to size restrictions of viral vectors.

Addressing these challenges will necessitate a focus on several areas: (1) Elucidating the underlying mechanisms of the currently developed enzymes to both reduce off-target effects and enhance on-target efficiencies; (2) Discovering and engineering additional enzymes or methods capable of efficient genome knock-in, such as novel recombination systems, or target-primed reverse transcription systems from mobile genetic elements, such as LTR, non-LTR retro-transposons, and group II introns [37–39]; (3) Developing superior delivery methods while optimizing the composition and size of gene-editing technologies.

In summary, CRISPR/Cas-based large sequence gene knock-in technologies hold substantial promise for both basic research and therapeutic translation. While the past two years have seen impressive advancements in this field, there is still room for optimization and innovation in the future.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Le Cong reports financial support was provided by National Institutes of Health. Le Cong reports relationship with PossibleMedicines, AcrobatGenomics, ArborBiotechnology, CureGenetics, and RootpathGenomics that includes: equity or stocks.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

* * of outstanding interest

- 1.Doudna JA, Charpentier E: The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 2014, 346:1258096. 1258096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsu Patrick D, Lander Eric S, Zhang F: Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell 2014, 157:1262–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carr PA, Church GM: Genome engineering. Nat Biotechnol 2009, 27:1151–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anzalone AV, Koblan LW, Liu DR: Genome editing with CRISPR–Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors. Nat Biotechnol 2020, 38:824–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durai S: Zinc finger nucleases: custom-designed molecular scissors for genome engineering of plant and mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res 2005, 33:5978–5990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanjana NE, Cong L, Zhou Y, Cunniff MM, Feng G, Zhang F: A transcription activator-like effector toolbox for genome engineering. Nat Protoc 2012, 7:171–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller JC, Tan S, Qiao G, Barlow KA, Wang J, Xia DF, Meng X, Paschon DE, Leung E, Hinkley SJ, et al. : A TALE nuclease architecture for efficient genome editing. Nat Biotechnol 2011, 29:143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker S, Boch J: TALE and TALEN genome editing technologies. Gene and Genome Editing 2021, 2, 100007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, et al. : Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 2013, 339: 819–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Church GM: RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science 2013, 339:823–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erwood S, Gu B: Embryo-based large fragment knock-in in mammals: why, how and what’s next. Genes 2020, 11:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu B: Light up the embryos: knock-in reporter generation for mouse developmental biology. Anim Reprod 2020, 17, e20200055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakuma T, Nakade S, Sakane Y, Suzuki K-IT, Yamamoto T: MMEJ-assisted gene knock-in using TALENs and CRISPR-Cas9 with the PITCh systems. Nat Protoc 2015, 11: 118–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maresca M, Lin VG, Guo N, Yang Y: Obligate Ligation-Gated Recombination (ObLiGaRe): custom-designed nuclease-mediated targeted integration through nonhomologous end joining. Genome Res 2012, 23:539–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15*.Rybarski JR, Hu K, Hill A, Wilke CO, Finkelstein IJ: Metagenomic discovery of CRISPR-associated transposons. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 2021:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article built a CRISPR-associated transposon (CAST) identification pipeline and expanded the diversity of reported CAST system.

- 16.Peters JE: Tn7. Microbio Spectrum 2014, 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kholodii GY, Yurieva OV, Lomovskaya OL, Gorlenko Z, Mindlin SZ, Nikiforov VG: Tn5053, a mercury resistance transposon with integron’s ends. J Mol Biol 1993, 230: 1103–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strecker J, Ladha A, Gardner Z, Schmid-Burgk JL, Makarova KS, Koonin EV, Zhang F: RNA-guided DNA insertion with CRISPR-associated transposases. Science 2019, 365:48–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strecker J, Ladha A, Makarova KS, Koonin EV, Zhang F: Response to Comment on “RNA-guided DNA insertion with CRISPR-associated transposases.”. Science 2020:368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20**.Tou CJ, Orr B, Kleinstiver BP: Precise cut-and-paste DNA insertion using engineered type V-K CRISPR-associated transposases. Nat Biotechnol 2023. 10.1038/s41587-022-01574-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study, 5’ nick in type V–K CRISPR-associated transposases were generated by fusion with a nicking homing endonuclease to achieve improved integration product purity and genome-wide specificity. The authors demonstrate this HELIX system enables cut-and-paste DNA insertion with up to 99.4% insertion product purity.

- 21.Klompe SE, Vo PLH, Halpin-Healy TS, Sternberg SH: Transposon-encoded CRISPR-Cas systems direct RNA-guided DNA integration. Nature 2019. 10.1038/s41586-019-1323-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vo PLH, Ronda C, Klompe SE, Chen EE, Acree C, Wang HH, Sternberg SH: CRISPR RNA-guided integrases for high-efficiency, multiplexed bacterial genome engineering. Nat Biotechnol 2020, 39:480–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weller SK, Sawitzke JA: Recombination promoted by DNA viruses: phage λ to Herpes Simplex Virus. Annu Rev Microbiol 2014, 68:237–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wannier TM, Nyerges A, Kuchwara HM, Czikkely M, Balogh D, Filsinger GT, Borders NC, Gregg CJ, Lajoie MJ, Rios X, et al. : Improved bacterial recombineering by parallelized protein discovery. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117; 2020:13689–13698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25*.Wang C, Cheng JKW, Zhang Q, Hughes NW, Xia Q, Winslow MM, Cong L: Microbial single-strand annealing proteins enable CRISPR gene-editing tools with improved knock-in efficiencies and reduced off-target effects. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49:e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Phage single-stranded DNA annealing protein (SSAP) RecT was coupled with CRISPR/Cas9 system to insert kilobase-scale exogenous sequences at defined genomic regions in mammalian cells including human stem cells. This is the first study using SSAP to facilitate homology-directed mammalian gene editing.

- 26**.Wang C, Qu Y, Cheng JKW, Hughes NW, Zhang Q, Wang M, Cong L: dCas9-based gene editing for cleavage-free genomic knock-in of long sequences. Nat Cell Biol 2022, 24:268–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study reported the development of a dCas9-SSAP editor, which harmonized the programmability of CRISPR with the SSAP activity of phage RecT. This dCas9-SSAP editor is capable of inserting kilobase-scale DNA sequence with an efficiency of up to ~20% across donor designs and cells type and shows minimal DNA damage and errors.

- 27.Duportet X, Wroblewska L, Guye P, Li Y, Eyquem J, Rieders J, Rimchala T, Batt G, Weiss R: A platform for rapid prototyping of synthetic gene networks in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42:13440–13451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gersbach CA, Gaj T, Gordley RM, Mercer AC, Barbas CF: Targeted plasmid integration into the human genome by an engineered zinc-finger recombinase. Nucleic Acids Res 2011, 39:7868–7878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mercer AC, Gaj T, Fuller RP, Barbas CF: Chimeric TALE recombinases with programmable DNA sequence specificity. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40:11163–11172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaikind B, Bessen JL, Thompson DB, Hu JH, Liu DR: A programmable Cas9-serine recombinase fusion protein that operates on DNA sequences in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res 2016. 10.1093/nar/gkw707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anzalone AV, Randolph PB, Davis JR, Sousa AA, Koblan LW, Levy JM, Chen PJ, Wilson C, Newby GA, Raguram A, et al. : Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature 2019:576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32**.Anzalone AV, Gao XD, Podracky CJ, Nelson AT, Koblan LW, Raguram A, Levy JM, Mercer JAM, Liu DR: Programmable deletion, replacement, integration and inversion of large DNA sequences with twin prime editing. Nat Biotechnol 2021, 40: 731–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors described twin prime editing (twinPE) which uses a prime editor protein and two prime editing guide RNAs for programmable replacement, excision of DNA, and gene-sized integration when combined with site-specific recombinase Bxb1, without requiring double-strand breaks.

- 33**.Yarnall MTN, Ioannidi EI, Schmitt-Ulms C, Krajeski RN, Lim J, Villiger L, Zhou W, Jiang K, Garushyants SK, Roberts N, et al. : Drag-and-drop genome insertion of large sequences without double-strand DNA cleavage using CRISPR-directed integrases. Nat Biotechnol 2022:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors developed the technique, Programmable Addition via Site-Specific Targeting Elements (PASTE), which employs a CRISPR-Cas9 nickase combined with serine integrase and reverse transcriptase, to achieve efficient and multiplexed integration of transgenes in dividing, non-dividing cells and in animal models.

- 34.Sun C, Lei Y, Li B, Gao Q, Li Y, Cao W, Yang C, Li H, Wang Z, Li Y, et al. : Precise integration of large DNA sequences in plant genomes using PrimeRoot editors. Nat Biotechnol 2023. 10.1038/s41587-023-01769-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Standage-Beier K, Brookhouser N, Balachandran P, Zhang Q, Brafman DA, Wang X: RNA-guided recombinase-Cas9 fusion targets genomic DNA deletion and integration. CRISPR J 2019, 2:209–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allen AG, Khan SQ, Margulies CM, Viswanathan R, Lele S, Blaha L, Scott SN, Izzo KM, Gerew A, Pattali R, et al. : A highly efficient transgene knock-in technology in clinically relevant cell types. Nat Biotechnol 2023. 10.1038/s41587-023-01779-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37*.Wilkinson ME, Frangieh CJ, Macrae RK, Zhang F: Structure of the R2 non-LTR retrotransposon initiating target-primed reverse transcription. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2023, 380: 301–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article reported the cryo-electron microscopy structure of a R2 non-long terminal repeat (non-LTR) retrotransposon initiating target-primed reverse transcription (TPRT) at its ribosomal DNA target. The authors dissected the principles of target DNA and self-RNA recognition, suggested its future use as a reprogrammable RNA-based gene-insertion tool.

- 38.Hancks DC, Kazazian HH: Roles for retrotransposon insertions in human disease. Mobile DNA 2016, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Belfort M, Lambowitz AM: Group II intron RNPs and reverse transcriptases: from retroelements to research tools. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol 2019, 11, a032375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.