Abstract

To identify cis-acting elements in the foamy virus (FV) RNA pregenome, we developed a transient-vector-production system based on cotransfection of indicator gene-bearing vector and gag-pol and env expression plasmids. Two elements which were critical for vector transfer were found and mapped approximately. The first element was located in the RU5 leader and the 5′ gag region (approximately up to position 650 of the viral RNA). The second element was located in an approximately 2-kb sequence in the 3′ pol region. Although small 5′ and 3′ deletions, as well as internal deletions of the latter element, were tolerated, both elements were found to be absolutely required for vector transfer. The functional characterization of the pol region-located cis-acting element revealed that it is essential for efficient incorporation or the stability of particle-associated virion RNA. Furthermore, virions derived from a vector lacking this sequence were found to be deficient in the cleavage of the Gag protein by the Pol precursor protease. Our results suggest that during the formation of infectious virions, complex interactions between FV Gag and Pol and the viral RNA take place.

The identification of cis-acting RNA elements is a prerequisite for the establishment of safe retroviral vectors and packaging cell lines (28, 33). In retroviruses, cis-acting sequences (CASs) may be involved in RNA dimerization and genome packaging (4, 28), in reverse transcription (50), and in the regulation of gene expression at the transcriptional or posttranscriptional level (11). Some of these sequences, such as the transcriptional trans-activator response element or the Rev response element of lentiviruses, interact with viral regulatory proteins (11). While these elements can be replaced by constitutive promoters or constitutive RNA transport elements (CTEs), respectively, RU5 and U3R sequences of the long terminal repeat (LTR), adjacent sequences (the polypurine tract [PPT] and the primer binding site, and RNA dimerization and packaging sequences must invariantly be present on the retrovirus vector genome (7, 22, 33, 54). Fortunately, some of these elements overlap at least partially in the retrovirus vectors, which have been characterized in detail (4, 33).

The use of foamy virus (FV)-derived vectors in gene transfer experiments may be more advantageous than murine leukemia virus-derived vectors, and preliminary constructs have already been used (5, 18, 39, 45, 47). However, the FV CASs have not been characterized. Furthermore, the replication strategy of FVs appears to differ markedly from those of all other retroviruses (34, 44, 52, 53). We therefore wished to improve FV vectors and to learn more about the unusual mode of replication of this virus group by characterizing the cis-acting RNA elements of the so-called human FV (HFV) isolate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Baby hamster kidney cells (BHK-21), human fibroblasts (KMST6) (37), and simian virus 40 T-antigen-expressing human embryonal kidney cells (293T) (12) were cultivated in Eagle’s minimal essential medium or Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 5 to 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics.

Recombinant DNA.

The pcHSRV2 (27, 34)-derived and human cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early enhancer- and promoter-directed HFV expression plasmids (pMH4, pMH5, and pMH5/M54) and the HFV gag-pol and env gene expression plasmids (pCgp-1 and pCenv-1) have been described previously (16). The pol gene expression plasmid, pCpol-2, was made by substituting a 4.28-kb XbaI fragment of pPZ-2 (21) for a 5.74-kb XbaI fragment of pHSRV2 (47). Thus, this plasmid contains the CMV enhancer and promoter directing the expression of a pol gene transcript with a spliced leader sequence (21). Vectors were made by deleting pMH5 or pMH5/M54 constructs with suitable restriction enzyme sites and by religation after treatment of the ends with Klenow enzyme or phage T4 polymerase as appropriate. All vectors bear an expression cassette made up of the spleen focus-forming virus (SFFV) U3 region (2) and the gene coding for green fluorescent protein (GFP), as described previously (16).

The plasmid pSP/HFV-2, which was used to generate the antisense cRNA probe for the RNase protection analysis, was made by inserting a 760-bp HindIII-AvrII (blunted) fragment spanning a region from the HindIII site in U3 of pHSRV2 (47) to the AvrII site in the gag leader into HindIII-EcoRI (blunted)-cut pSP65.

Analysis of vector transfer efficiency.

DNAs were prepared with Maxi Kit columns (Qiagen). Equal amounts of vector-containing DNA (27 μg) and the expression plasmids for the HFV structural proteins were transiently transfected into 2 × 106 293T cells in 6-cm-diameter dishes as calcium phosphate coprecipitates (1, 48). Twenty-four hours posttransfection, the CMV promoter was induced with 10 mM sodium butyrate for 8 h (48). Forty-eight hours following transfection, the supernatant was harvested and passed through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter (Schleicher & Schuell) and 1 ml of each was applied to BHK-21 and KMST6 recipient cells seeded the day before at a density of 3 × 103 cells per well in 24-well plates. Seventy-two hours following transduction, the recipient cells were detached from the plastic support and washed in phosphate-buffered saline. At that time, approximately 5 × 104 BHK-21 cells and 2 × 104 KMST6 cells were harvested. The amounts of transduced cells were determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting on a FACScan device with the LysisII and CellQuest software packages (Becton Dickinson) and expressed as the percentages of GFP-positive cells in relation to the total number of cells analyzed. All experiments were done with at least two independent plasmid preparations and at least four times. We always found some variation (as indicated in the figures) from assay series to assay series, probably due to transfection efficiencies. However, the results within a series of experiments were consistent.

Protein analysis.

Lysates from transfected cells or from cell-free virus which was sedimented through a 20% sucrose cushion in TNE (100 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) for 3 h at 25,000 rpm in an SW41 rotor (Beckman) at 4°C were prepared as described previously (17). The samples were run on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels (8% polyacrylamide) and semidry blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell). The blots were allowed to react with rabbit antisera raised against recombinant HFV Gag (17) and RNase H (23) and were developed with the ECL detection system (Amersham).

RNase protection analysis.

Supernatants from four 6-cm-diameter dishes, which were transfected with the same plasmids, were pooled and passed through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter and the viral particles were concentrated by ultracentrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion as described above. The virus particle-containing sediment was resuspended in 60 μl of phosphate-buffered saline. Twenty microliters was used for immunoblot analysis, and viral RNA was extracted from the remaining 40 μl with the Qiamp viral RNA kit (Qiagen). RNase protection analysis was performed with the HypSpeed RPA kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Ambion) and with 20 μl of a total volume of 50 μl of RNA eluted from the preparation column. Following linearization with HindIII, an antisense 777-nucleotide (nt) riboprobe was synthesized with 25 μCi of [α-32P]GTP (Amersham) by standard protocols (1). The probe was resuspended in 50 μl of sodium dodecyl sulfate-containing buffer, and 0.05 μl (containing approximately 10,000 cpm) was used per reaction. RNase digestion was performed with 20 μg of RNase A/ml and 400 U of RNase T1/ml for 40 min at 37°C. The reaction products were resolved on 7 M urea-containing 5% polyacrylamide gels. Once dry, the gels were exposed to X-ray film, and quantification was performed with a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager.

RESULTS

Design of the experimental strategy.

HFV is a complex retrovirus (10, 43). In addition to the Gag, Pol, and Env proteins, replication of HFV requires at least the presence of the Tas–Bel-1 transcriptional trans-activator (3, 43). All previous HFV vector constructs depended on the Tas protein, which was either encoded in the vector genome (39, 47) or provided for by cotransfection of replication-competent helper virus, by a Tas expression plasmid (18, 45), or by a stable Tas-expressing cell line (5). To develop HFV vectors which are independent of Tas, we generated an expression plasmid (pMH4) (Fig. 1) in which gene expression of the provirus was regulated by the strong CMV promoter. In this plasmid, the start of transcription, beginning with the R region of the LTR, was preserved (27, 34). The 3′ region of the HFV genome with the accessory bel genes was deleted, and an expression cassette for GFP under the control of the constitutively active SFFV U3 region was inserted. Transfection of pMH4 gives rise to virus which is able to perform one round of replication. Following integration into recipient cells, gene expression from the HFV LTR is silent and the SFFV U3 promoter directs the expression of GFP, which can easily be monitored. Transfection of an infectious genome under the control of the CMV promoter (pcHSRV2) into 293T cells has been reported to give rise to up to 105 infectious viruses within 48 h (27). When pMH4 was transfected into 293T cells and hamster or human fibroblasts were exposed to the supernatant, transduction efficiencies were usually over 50% under the assay conditions outlined above (Fig. 2). When the transduced cells were reanalyzed following cultivation for several weeks, the percentage of GFP-positive cells remained unchanged, indicating that the transduction was stable (data not shown). The transduction efficiency of recipient cells did not vary significantly when the env gene was deleted from the vector genome and Env was provided from a separate expression construct (pMH5 and pCenv-1) (Fig. 1). Neither did it vary when the pol gene ATG of pMH5 was down-mutated (pMH5/M54) and Env and Pol (pCgp-1) (Fig. 1) were provided in trans by triple plasmid cotransfection of 293T cells (see values in Fig. 2). Using this functional assay, we generated a set of deletion mutants of the vector to identify the regions of the genome critical for vector transfer.

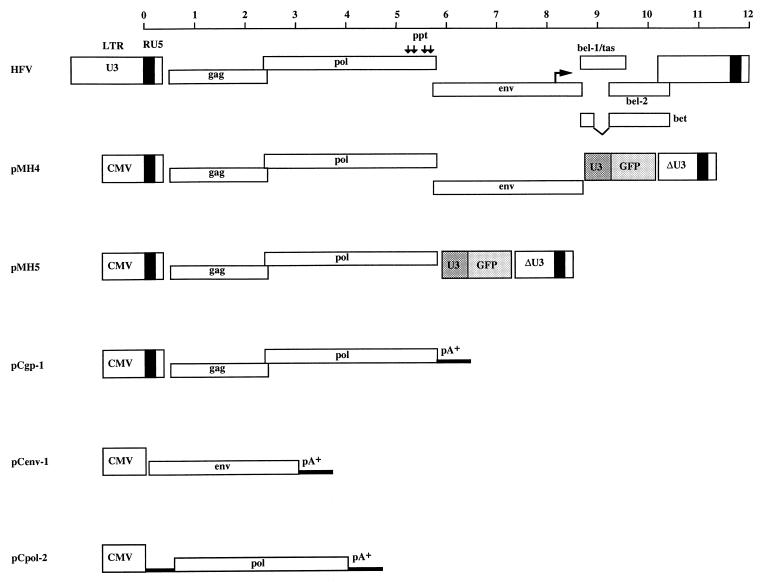

FIG. 1.

HFV genome organization and basic HFV vectors and expression plasmids. The scale at the top is drawn with respect to the start of transcription (position 1 of R in the LTR). Vertical arrows above the pol gene of HFV indicate the location of purine-rich sequences which may serve as internal initiators of plus-strand synthesis during reverse transcription. The fourth central PPT has been characterized previously (25, 51). The arrow in the env gene indicates the FV-specific internal promoter (31). In pMH4, pMH5, and pCgp-1, the start of transcription of the CMV promoter, which drives the expression of HFV genes, is identical to that of HFV. In pMH4 and pMH5, an internal cassette made up of the SFFV U3 region that directs the expression of GFP (S65T) was inserted upstream of the 3′ LTR (16). The 3′ LTR was derived from the infectious clone pHSRV2 (47). This LTR is a deletion variant of the full-length LTR, and it occurred spontaneously in cell culture (46). pCpol-2 is a Pol expression plasmid. It contains the leader sequence of the spliced HFV pol mRNA (21). pA+ indicates the polyadenylation signal derived from bovine growth hormone and present in the pcDNA vector (Invitrogen).

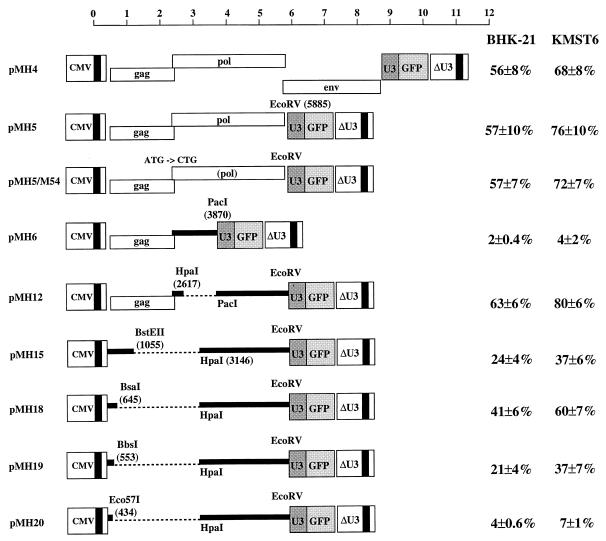

FIG. 2.

Two cis-acting elements are required to transfer HFV vectors. The vector plasmids (9 μg) together with pCgp-1 (9 μg) and pCenv-1 (9 μg), or adjusted with pcDNA (in the cases of pMH4 and pMH5) for a total amount of 27 μg of DNA, were transfected into 293T cells. The cell-free supernatant was used to transduce BHK-21 and KMST6 cells. The results are expressed as the percentages of GFP-positive cells relative to the total number of cells analyzed and represent the means and standard errors from four independent experiments. The locations of restriction enzyme sites used to construct the vectors are indicated with respect to the start of transcription. Deletions are marked as dotted lines. The scale is as in Fig. 1.

Two cis-acting elements are essential to transfer HFV vectors.

The deletion of the 3′ part of the pol region (pMH6) (Fig. 2) abrogated transduction by HFV vectors, while the 5′ portion of pol was not required for efficient transfer (pMH12) (Fig. 2). This indicated that one essential CAS was located approximately between positions 3870 and 5885 after the start of transcription (position 1 of the R region of the LTR).

Retroviral packaging sequences are usually located in the 5′ region of the genome to avoid the packaging of subgenomic RNAs (4, 28). To determine whether a 5′ CAS existed in the HFV genome, we generated a series of deletion mutants extending into the gag region with a plasmid which contained the element in pol identified in the previous experiments (pMH15). As shown in Fig. 2, deletions were tolerated up to position 645 (pMH18), while further deletions up to position 553 (pMH19) and 434 (pMH20) led to modest or severe reductions in transfer efficiencies, respectively. Since the ATG start codon of the gag gene is located at position 445 of the RNA (32), the 5′ CAS of HFV extends into the gag gene. With pMH15, we observed a reduced transduction efficiency relative to that of pMH18, although the deletion in the latter was greater (Fig. 2). This discrepancy is probably due to the fact that a relatively large aberrantly truncated Gag protein (approximately 200 amino acids) is expressed from pMH15, which may dominantly interfere with HFV particle assembly. With some other deletion constructs which could generate aberrant Gag-Pol fusion proteins, such a dominant negative effect on the transfer of pMH5 wild-type vector was observed (data not shown).

Taken together, the results presented in Fig. 2 indicate that two CASs are essential for the transfer of HFV-based vectors. One is located in the 5′ leader region (CAS I) and one in the 3′ pol region (CAS II).

In the experiment whose results are presented in Fig. 2, all vector constructs except pMH4 and pMH5 were cotransfected with the Gag-Pol and Env expression plasmids, pCgp-1 and pCenv-1. The RU5 leader region and the gag and pol regions are contained in the pCgp-1 plasmid (Fig. 1) because in FVs, Pol is expressed from a spliced mRNA, and the splice donor site is located in the R region at position 51 (35). Therefore, copackaging of the pCgp-1-derived primary transcript may take place, since it harbors CAS I and CAS II. RNase protection analysis revealed that pCgp-1 RNA was indeed packaged into virions (data not shown). However, the pCgp-1 transcript does not contain the U3-GFP cassette (Fig. 1), and a significant reduction in vector transfer efficiencies due to copackaging of pCgp-1 RNA with the vector RNA was not observed (compare the transduction efficiencies obtained with pMH4 or pMH5 with those obtained with pMH5/M54, pMH12, or pMH18, as shown in Fig. 2).

Fine mapping of CAS II.

The second CAS was located in an approximately 2-kb fragment at the 3′ end of the pol region and extending approximately 160 nt into the env region (pMH12 in Fig. 2). To better understand the function of CAS II in vector transfer and to optimize the capacity of HFV vectors further, deletion mutants of the HpaI-EcoRV fragment (i.e., the fragment occupying positions 3146 to 5885 of the viral RNA) of pMH18, a plasmid which already has 3′ gag sequences downstream of position 645 deleted (Fig. 2), were constructed. Deletions introduced into the HpaI-EcoRV fragment in the 3′ direction were tolerated up to position 3871 (pMH25) (Fig. 3). Further deletions up to position 4663 (pMH27) or 5216 (pMH30) resulted in significantly reduced transfer efficiency (Fig. 3). Removal of approximately 650 bp from the 3′ region of the element (pMH26) led to a similar reduction. The transfer activity was restored when smaller deletions from the 5′ and 3′ ends of the fragment were introduced (pMH32) or when only small internal fragments, i.e., of 550 or 220 bp, were removed from CAS II (pMH28 and pMH29 in Fig. 3, respectively). The experiments with the latter constructs suggest that CAS II is bipartite.

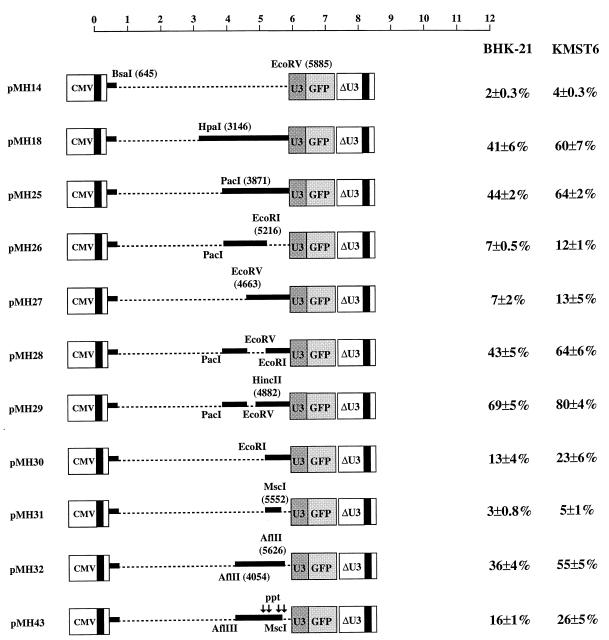

FIG. 3.

Fine mapping of CAS II. HFV vector deletion constructs were used to characterize the RNA element in the pol region more precisely. The experimental strategy described in the legend for Fig. 2 was used. The vertical arrows in pMH43 (bottom) indicate the location of purine-rich sequences, at least one of which probably functions as an internal PPT for the initiation of plus-strand synthesis (25, 51). Deletions are marked as dotted lines. The scale is as in Fig. 1.

It has been shown previously that HFV contains in the center of the genome (in the 3′ pol region) a duplication of the PPT (25, 51). Such an internal PPT is also found in lentiviruses (9). For human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the second PPT is involved in dual initiation of plus-strand synthesis (8). Furthermore, it has been reported that the central PPT is required for optimal HIV replication in cell culture (8). We therefore wished to analyze whether the central PPT of HFV plays a major role in mediating transfer by CAS II. While efficient transfer was obtained with pMH32, a construct with a deletion in the PPT (pMH43) led to an approximately 50% reduction of transfer efficiency (Fig. 3). This indicated that the PPT may play some role in vector transfer. Closer inspection of the genomic region in question revealed that not one but four potential central PPTs are present in HFV (Fig. 1 and 3). It has not yet been determined which of these can be used by the virus and whether any of these is required for efficient viral replication. However, pMH27, which contained all potential PPTs, was not transferred efficiently (Fig. 3). Furthermore, with pMH31, which contained the two centrally located potential PPTs, transfer efficiency was reduced to the value of the negative control, pMH14, which lacked the complete CAS II (Fig. 3). The same holds true for a derivative of pMH14, pMH24, into which the fourth and originally reported PPT (25, 51) was introduced as an oligonucleotide (data not shown). These experiments indicated that the functions of the internal PPT and CAS II are different and required further analysis.

Effect of CAS II on gene expression and virion RNA content.

The effect of CAS II on vector transfer led us to hypothesize that it has a function in either posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression or genome packaging. To investigate these topics, we used the three constructs, pMH5/M54, pM38, and pMH40, depicted in Fig. 4A. Common to the constructs is the presence of the complete gag gene and the down-mutation of the pol gene ATG to CTG (14). While pMH5/M54 contained the complete pol region, pMH38 had the 3′ pol region (CAS II) deleted, and pMH40 lacked the 5′ pol region and contained CAS II. As expected from the results presented in Fig. 3, cotransfection of pCpol-2 and pCenv-1 with the vector DNAs affected transfer only with pMH5/M54 and pMH40 (Fig. 4A).

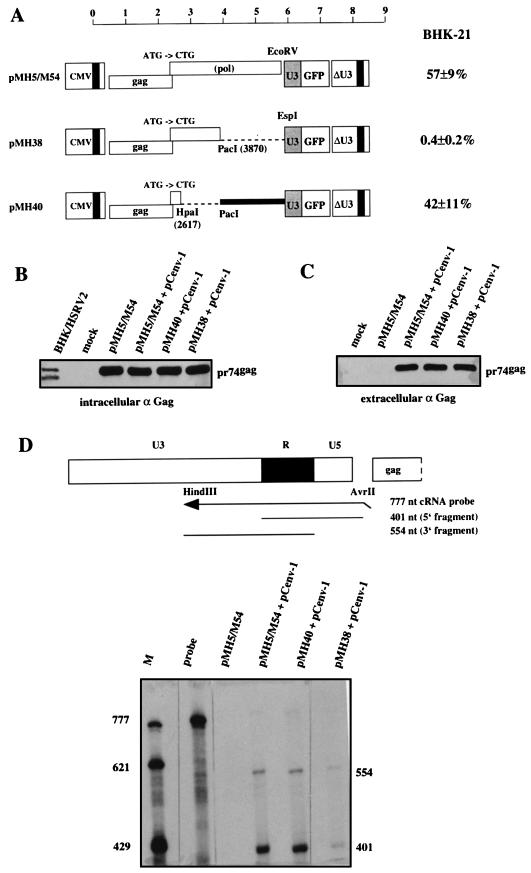

FIG. 4.

Effect of CAS II on HFV protein expression and virion RNA content. The Gag-positive and Pol-negative vectors pMH5/M54, pMH38, and pMH40 were used to determine these effects. (A) The vector plasmids were cotransfected with pCpol-2 and pCenv-1 into 293T cells, and the transduction efficiencies of cell-free viruses were determined on BHK-21 cells. Results are expressed as described for Fig. 2. (B) The immunoblot analysis of 293T cells transfected with the vector constructs plus pCenv-1 revealed that all plasmids expressed similar amounts of Gag (pr74), thus ruling out an essential role for CAS II as an RNA transport element. A diluted lysate from BHK-21 cells infected with HSRV2, the virus derived from pHSRV2, was run as a control. (C) Gag content of cell-free particles following centrifugation through a sucrose cushion. Similar amounts of pr74gag are present in the preparations of cells cotransfected with pCenv-1 plus either pMH5/M54, pMH38, or pMH40. Note that Env coexpression is required for cellular export of HFV capsids (16). (D) RNase protection analysis of virion RNA in the particulate material analyzed in Fig. 4C for Gag content. 5′ (401-nt) and 3′ (554-nt) fragments corresponding to the RU5 and U3R regions, respectively, of the viral RNA are specifically protected in pMH5/M54- and pMH40-derived virions. pMH38-derived virions showed an 80% reduced RNA content. The marker lane (M) contained in vitro-transcribed RNA from pSP/HFV-2 which was linearized with HindIII (777 nt), BsaAI (621 nt), and XbaI (429 nt).

Analysis of protein expression in cells transfected with the vector plasmids and pCenv-1 revealed that all three constructs expressed pr74 Gag precursor protein to a similar extent (Fig. 4B). Since the Gag protein could be expressed only from the vector genomes, it is very unlikely that CTE plays a role in CAS II-mediated vector transfer.

We next investigated the virion RNA content of the three vector genomes. The replication strategy of HFV poses a problem in this analysis, since reverse transcription of the RNA pregenome most likely takes place as a late event in the viral replication cycle before the budding of the virus (34). Although a definite answer to this question is not yet available, at the least, the presence of large amounts of virion DNA (53) complicates the detection and quantification of packaged virion RNA. To circumvent this problem, we analyzed the RNA content of extracellular virions prepared following cotransfection of the vector plasmids (Fig. 4A) with pCenv-1 alone. In this situation reverse transcription cannot occur. However, cleavage of the Gag precursor (pr74) to generate the p70 molecule, which probably represents the final capsid-forming structure (16), also cannot occur (24). The expression of pr74 has been reported to result in a majority of aberrantly formed capsid structures which are, however, enveloped upon coexpression of HFV Env (16, 24). Thus, we observed efficient cellular export of particulate material following cotransfection of vector plasmids with the Env protein expression construct (Fig. 4C). RNase protection analysis of similar amounts of virions, as judged by immunoblot analysis of Gag (Fig. 4C), revealed that vector RNA was specifically protected in extracellular virions prepared from cells cotransfected with pMH5/M54 plus pCenv-1 (Fig. 4D). Specific bands of 401 and 554 nt, which corresponded to the protection of 5′ and 3′ LTR regions (Fig. 4D), respectively, were also detected in virions prepared from cells cotransfected with pMH40 plus pCenv-1 and, to a much lesser extent, in virions prepared from cells cotransfected with pMH38 plus pCenv-1 (Fig. 4D). Quantification (the mean of three assays) of the band corresponding to the protected 5′ RNA fragment revealed that in relation to the RNA content of pMH5/MH54-derived virions (100%), the RNA content of pMH40-derived virions was approximately 90%, while the RNA content in pMH38-derived virions was reduced to approximately 20%. This suggests that CAS II has a major effect on RNA pregenome packaging or virion RNA stability. Furthermore, unlike hepadnaviruses, HFV appeared not to require Pol for incorporation of virion RNA (38).

Effect of CAS II on virion protein content.

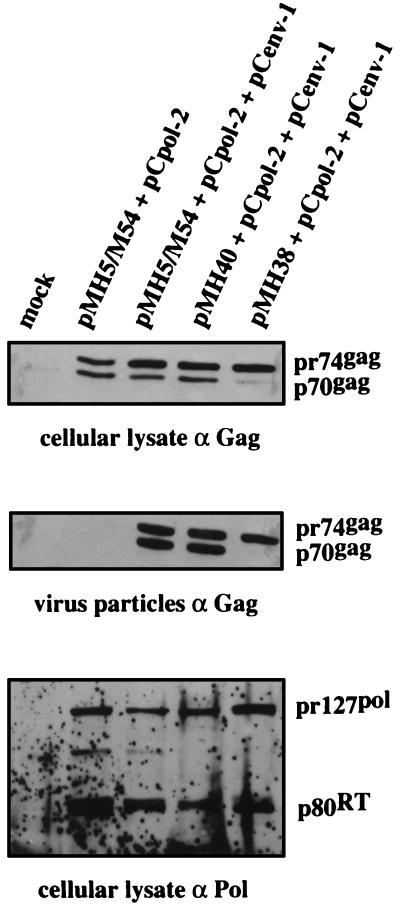

We examined the protein composition of virions prepared from cells which were transfected with pCpol-2 and pCenv-1 plus the vector plasmids pMH5/M54, pMH38, or pMH40. As shown in Fig. 5, the p70-pr74 Gag doublet was detected in cellular lysates and extracellular virions following transfection of pMH5/M54 or pMH40 together with pCpol-2 and pCenv. In sharp contrast to this, we never observed cleavage of the pr74 Gag precursor protein in virions prepared from the supernatant of cells transfected with pMH38 plus pCpol-2 and pCenv-1. Immunoblotting with a Pol-specific antiserum detected the precursor protein pr127 and the p80 reverse transcriptase in the lysates from cells transfected with the vector plasmids, which ruled out the possibility that the inability to cleave pr74gag in pMH38-transfected cells was due to a lack of expression of active Pol (Fig. 5). When extracellular virions were probed for Pol to determine whether it was incorporated into the virus particle, the assay sensitivity was at the margin of the detection level, yielding inconclusive results (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Effect of CAS II on Pol function. pMH5/M54, pMH38, and pMH40 were cotransfected into 293T cells together with pCpol-2 and pCenv-1. Forty-eight hours following transfection, Gag proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting in cellular lysates and in particulate material centrifuged through a sucrose cushion. A weak band which reacted with the Gag antibody and comigrated with the p70gag band was often detected in cellular lysates of mock-transfected 293T cells. Therefore, this weak band in pMH38-transfected cells was regarded as being nonspecific. The cellular lysate blot reacted with Gag antibody was stripped and subsequently reacted with Pol antibody.

DISCUSSION

The identification of cis-acting elements is a key step in the development of viral vectors. Using a sensitive indicator gene system, which is based on efficient transient virus production following transfection of vector, and Gag-Pol and Env expression plasmids (26, 48), we were able to identify CASs in the HFV genome. One element was located in the 5′ leader region of the pregenomic HFV transcript. In other retroviruses, the major RNA packaging sequence has been located in this region (4, 28, 33), and it is likely that further studies will identify a similar function for the signal in question in HFV. This hypothesis is supported by the finding that the dimer linkage sequence of HFV is located in the 5′ leader (15). In other retroviruses, the dimer linkage sequence and RNA packaging sequence usually overlap (4, 33).

By the same experimental strategy, we found another CAS in the 3′ pol region of HFV, the presence of which was absolutely required for vector transfer. This pointed to an essential role of CAS II in viral replication. Further investigation of CAS II revealed that its function was independent of the additional PPT located in the central region of the HFV genome (25, 51). Although the presence of an internal PPT had some influence on vector transfer efficiency, the locations of CAS II and the PPT could clearly be separated with appropriate vector constructs (Fig. 3). Similar findings have been made for HIV (42). The presence of the central PPT in the vector genome led only to a modest (twofold, as observed in the present study for HFV) increase in gene expression following transduction of recipient cells (42). In addition, currently used HIV vectors lack the central PPT (22, 36).

Further, CAS II was found not to be required for efficient gene expression. CTEs have been identified in a variety of retroviruses and in hepadnaviruses (7, 19, 20, 41, 49, 54). In functional terms, HFV belongs to the group of complex regulated retroviruses (10, 43). However, in contrast to the lentivirus and the human T-cell leukemia and bovine leukemia groups of complex retroviruses, a posttranscriptionally acting regulatory protein has not been found for HFV, and structural gene expression appeared to be independent of RNA sequences outside the coding regions (3, 16). As deduced from the results shown in Fig. 4, the presence or absence of CAS II had no major influence on the expression of the HFV vectors used, and therefore, CAS II is unlikely to influence RNA transport. Since HFV makes extensive use of RNA splicing (27, 30, 35), the identification of an FV-specific CTE is still awaited.

RNase protection analysis revealed the major influence of CAS II on virion RNA content. This can be interpreted as an indication that either CAS II is a genuine packaging sequence or its presence is essential for stabilization of the RNA in the viral particle. Further experiments are required to clarify this question. Surprisingly, we found that the influence on viral RNA content was not the sole effect of CAS II. The protein analysis of HFV virions showed that, in particles derived from a vector devoid of CAS II (pMH38), cleavage of the Gag precursor protein does not occur. The finding that cleavage of pr74gag is absolutely essential for HFV infectivity (13, 24) explains the very low transduction rate obtained with this vector. However, the reason for the lack of Gag cleavage is unclear at the moment. The protease of FVs is encoded in the pol reading frame (40, 43), and HFV expresses Pol independently of Gag from a spliced mRNA (6, 14, 21, 29, 53). The mechanism by which HFV Pol is incorporated into the viral particle is still unresolved. Our experiments suggest either that virion RNA may be a bridging molecule between Gag and Pol or that it may be required, not for Pol incorporation per se, but for the functioning of the Pol precursor protein. Furthermore, this may involve a complex interaction between viral RNA and Gag and Pol. More sensitive assays than those used in this study are required to address this question.

The vectors resulting in the highest gene transfer efficiencies (pMH18, pMH25, pMH28, and pMH29) expressed RNA pregenomes smaller than 3.4 kb (without the inserted U3-GFP cassette). Given that the HFV wild-type pregenome is 11.7 kb in length (46), these still-preliminary vectors offer ample space for the insertion of foreign DNA without exceeding the viral packaging limit. Since the HFV LTR of these vectors is silent, they require the use of an internal promoter to direct expression of the gene of interest following transduction. This may turn out to be an advantage when tissue-specific or regulatable promoters can be used.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rolf Flügel for the generous gift of rabbit antiserum directed against HFV RNase H and Ian Johnston for critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the BMBF, Bayerische Forschungsstiftung, and EU (BMH4-CT97-2010).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baum C, Itoh K, Meyer J, Laker C, Ito Y, Ostertag W. The potent enhancer activity of the polycythemic strain of spleen focus-forming virus in hematopoietic cells is governed by a binding site for Sp1 in the upstream control region and by a unique enhancer core motif, creating an exclusive target for PEBP/CBF. J Virol. 1997;71:6323–6331. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6323-6331.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baunach G, Maurer B, Hahn H, Kranz M, Rethwilm A. Functional analysis of human foamy virus accessory reading frames. J Virol. 1993;67:5411–5418. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5411-5418.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkowitz R, Fischer J, Goff S P. RNA packaging. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;214:177–218. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80145-7_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bieniasz P D, Erlwein O, Aguzzi A, Rethwilm A, McClure M O. Gene transfer using replication-defective human foamy virus vectors. Virology. 1997;235:65–72. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bodem J, Löchelt M, Winkler I, Flower R P, Delius H, Flügel R M. Characterization of the spliced pol transcript of feline foamy virus: the splice acceptor site of the pol transcript is located in gag of foamy viruses. J Virol. 1996;70:9024–9027. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.9024-9027.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bray M, Prasad S, Dubay J W, Hunter E, Jeang K-T, Rekosh D, Hammarskjold M-L. A small element from Mason-Pfizer monkey virus genome makes human immunodeficiency virus type 1 expression and replication rev-independent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1256–1260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charneau P, Alizon M, Clavel F. A second origin of DNA plus-strand synthesis is required for optimal human immunodeficiency virus replication. J Virol. 1992;66:2814–2820. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.2814-2820.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charneau P, Clavel F. A single-stranded gap in human immunodeficiency virus unintegrated linear DNA defined by a central copy of the polypurine tract. J Virol. 1991;65:2415–2421. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2415-2421.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cullen B R. Human immunodeficiency virus as a prototypic complex retrovirus. J Virol. 1991;65:1053–1056. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1053-1056.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cullen B R. RNA-sequence-mediated gene regulation in HIV-1. Infect Agents Dis. 1994;3:68–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DuBridge R B, Tang P, Hsia H C, Leong P-M, Miller J H, Calos M P. Analysis of mutation in human cells by using Epstein-Barr virus shuttle system. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:379–387. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.1.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enssle J, Fischer N, Moebes A, Mauer B, Smola U, Rethwilm A. Carboxy-terminal cleavage of the human foamy virus Gag precursor molecule is an essential step in the viral life cycle. J Virol. 1997;71:7312–7317. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7312-7317.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enssle J, Jordan I, Mauer B, Rethwilm A. Foamy virus reverse transcriptase is expressed independently from the gag protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4137–4141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erlwein O, Cain D, Fischer N, Rethwilm A, McClure M O. Identification of sites that act together to direct dimerization of human foamy virus RNA in vitro. Virology. 1997;229:251–258. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer N, Heinkelein M, Lindemann D, Enssle J, Baum C, Werder E, Zentgraf H, Müller J G, Rethwilm A. Foamy virus particle formation. J Virol. 1998;72:1610–1615. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1610-1615.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hahn H, Baunach G, Bräutigam S, Mergia A, Neumann-Haefelin D, Daniel M D, McClure M O, Rethwilm A. Reactivity of primate sera to foamy virus gag and bet proteins. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2635–2644. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-10-2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirata R K, Miller A D, Andrews R G, Russel D W. Transduction of hematopoietic cells by foamy virus vectors. Blood. 1996;88:3654–3661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang J, Liang T J. A novel hepatitis B virus (HBV) genetic element with Rev response element-like properties that is essential for expression of HBV gene products. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7476–7486. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Z-M, Yen T S B. Hepatitis B virus RNA element that facilitates accumulation of surface gene transcripts in the cytoplasm. J Virol. 1994;68:3193–3199. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3193-3199.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jordan I, Enssle J, Güttler E, Mauer B, Rethwilm A. Expression of human foamy virus reverse transcriptase involves a spliced pol mRNA. Virology. 1996;224:314–319. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim V N, Mitrophanous K, Kingsman S M, Kingsman A J. Minimal requirement for a lentivirus vector based on human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:811–816. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.811-816.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kögel D, Aboud M, Flügel R M. Molecular biological characterization of the human foamy virus reverse transcriptase and ribonuclease H domains. Virology. 1995;213:97–108. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konvalinka J, Löchelt M, Zentgraf H, Flügel R M, Kräusslich H-G. Active foamy virus proteinase is essential for virus infectivity but not for formation of a Pol polyprotein. J Virol. 1995;69:7264–7268. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7264-7268.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kupiec J J, Tobaly-Tapiero J, Canivet M, Santillana-Hayat M, Flügel R M, Peries J, Emanoil-Ravier R. Evidence for a gapped linear duplex DNA intermediate in the replicative cycle of human and simian spumaviruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9557–9565. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.20.9557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindemann D, Bock M, Schweizer M, Rethwilm A. Efficient pseudotyping of murine leukemia virus particles with chimeric human foamy virus envelope proteins. J Virol. 1997;71:4815–4820. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4815-4820.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindemann D, Rethwilm A. Characterization of a human foamy virus 170-kilodalton Env-Bet fusion protein generated by alternative splicing. J Virol. 1998;72:4088–4094. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4088-4094.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linial M L, Miller A D. Retroviral RNA packaging: sequence requirements and implications. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;157:125–152. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-75218-6_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Löchelt M, Flügel R M. The human foamy virus pol gene is expressed as a Pro-Pol polyprotein and not as a Gag-Pol fusion protein. J Virol. 1996;70:1033–1040. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1033-1040.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Löchelt M, Flügel R M, Aboud M. The human foamy virus internal promoter directs the expression of the functional Bel 1 transactivator and Bet protein early after infection. J Virol. 1994;68:638–645. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.638-645.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Löchelt M, Muranyi W, Flügel R M. Human foamy virus genome possesses an internal, Bel-1-dependent and functional promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7317–7321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maurer B, Bannert H, Darai G, Flügel R M. Analysis of the primary structure of the long terminal repeat and the gag and pol genes of the human spumaretrovirus. J Virol. 1988;62:1590–1597. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.5.1590-1597.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller A D. Development and applications of retroviral vectors. In: Coffin J M, Hughes S H, Varmus H E, editors. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 437–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moebes A, Enssle J, Bieniasz P D, Heinkelein M, Lindemann D, Bock M, McClure M O, Rethwilm A. Human foamy virus reverse transcription that occurs late in the viral replication cycle. J Virol. 1997;71:7305–7311. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7305-7311.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muranyi W, Flügel R M. Analysis of splicing patterns of human spumaretrovirus by polymerase chain reaction reveals complex RNA structures. J Virol. 1991;65:727–735. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.2.727-735.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naldini L, Blömer U, Gallay P, Ory D, Mulligan R, Gage F H, Verma I M, Trono D. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science. 1996;272:263–267. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Namba M, Nishitani K, Hyodoh F, Fukushima F, Kimoto T. Neoplastic transformation of human diploid fibroblasts (KMST-6) by treatment with 60Co gamma rays. Int J Cancer. 1985;35:275–280. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910350221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nassal M, Schaller H. Hepatitis B virus replication. Trends Microbiol. 1993;1:221–228. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(93)90136-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nestler U, Heinkelein M, Lücke M, Meixensberger J, Scheurlen W, Kretschmer A, Rethwilm A. Foamy virus vectors for suicide gene therapy. Gene Ther. 1997;4:1270–1277. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Netzer K O, Schliephake A, Maurer B, Watanabe R, Aguzzi A, Rethwilm A. Identification of pol-related gene products of human foamy virus. Virology. 1993;192:336–338. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogert R A, Lee L H, Beemon K L. Avian retroviral RNA element promotes unspliced RNA accumulation in the cytoplasm. J Virol. 1996;70:3834–3843. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3834-3843.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parolin C, Taddeo B, Palu G, Sodroski J. Use of cis- and trans-acting regulatory sequences to improve expression of human immunodeficiency virus vectors in human lymphocytes. Virology. 1996;222:415–422. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rethwilm A. Regulation of foamy virus gene expression. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;193:1–23. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78929-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rethwilm, A. 1996. Unexpected replication pathways of foamy viruses. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 13(Suppl. 1):S248–S253. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Russell D W, Miller A D. Foamy virus vectors. J Virol. 1996;70:217–222. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.217-222.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmidt M, Herchenröder O, Heeney J, Rethwilm A. Long terminal repeat U3 length polymorphism of human foamy virus. Virology. 1997;230:167–178. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmidt M, Rethwilm A. Replicating foamy virus-based vectors directing high level expression of foreign genes. Virology. 1995;210:167–178. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soneoka Y, Cannon P M, Ramsdale E E, Griffith J C, Romano G, Kingsman S M, Kingsman A J. A transient three-plasmid expression system for the production of high titer retroviral vectors. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:628–633. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.4.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tabernero C, Zolotukhin A S, Bear J, Schneider R, Karsenty G, Felber B K. Identification of an RNA sequence within an intracisternal-A particle element able to replace Rev-mediated posttranscriptional regulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1997;71:95–101. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.95-101.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Telenitzky A, Goff S P. Reverse transcriptase and the generation of retroviral DNA. In: Coffin J M, Hughes S H, Varmus H E, editors. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 121–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tobaly-Tapiero J, Kupiec J J, Santillana-Hayat M, Canicet M, Peries J, Emanoil-Ravier R. Further characterization of the gapped DNA intermediates of human spumavirus: evidence for a dual initiation of plus-strand DNA synthesis. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:605–608. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-3-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weiss R A. Foamy viruses bubble on. Nature. 1996;380:201. doi: 10.1038/380201a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu S F, Baldwin D N, Gwynn S R, Yendapalli S, Linial M L. Human foamy virus replication: a pathway distinct from that of retroviruses and hepadnaviruses. Science. 1996;271:1579–1582. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zolotukhin A S, Valentin A, Pavlakis G N, Felber B K. Continuous propagation of RRE(−) and Rev(−)RRE(−) human immunodeficiency virus type 1 molecular clones containing a cis-acting element of simian retrovirus type 1 in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. J Virol. 1994;68:7944–7952. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7944-7952.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]