Abstract

Three-dimensional (3D) heterogeneous and anisotropic scaffolds that approximate native heart valve tissues are indispensable for the successful construction of tissue engineered heart valves (TEHVs). In this study, novel tri-layered and gel-like nanofibrous scaffolds consisting of poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) and poly (aspartic acid) (PASP) are fabricated by a combination of positive/negative conjugate electrospinning and bioactive hydrogel post-processing. The nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds present tri-layered structure, resulting in anisotropic mechanical properties that are comparable to native heart valve leaflets. Biological tests show that nanofibrous scaffolds with high PASP ratio significantly promote the proliferation and collagen and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) secretions of human aortic valvular interstitial cells (HAVICs) compared to PLGA scaffolds. Importantly, the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds are found to effectively inhibit the osteogenic differentiation of HAVICs. Two types of porcine VICs from young and adult age groups are further seeded onto the PLGA-PASP scaffolds. The adult VICs secrete higher amount of collagens and GAGs, and undergo a significantly higher level of osteogenic differentiation than young VICs. RNA sequencing analysis indicates that age has a pivotal effect on the VIC behaviors. This study provides important guidance and reference for the design and development of 3D tri-layered, gel-like nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds for TEHV application.

Keywords: electrospinning, hydrogel, structural anisotropy, valve interstitial cells, valve calcification

1. Introduction

Heart valves are essential soft tissues and undergo roughly 100,000 opening and closing cycles per day to maintain the proper direction of blood flow in the cardiovascular system.[1, 2] According to the current statistics, more than five million people require corresponding treatments for heart valve-related diseases annually in the USA.[3] Mechanical or bioprosthetic valves currently employed in the clinics exhibit some important capacities to save the lives of patients with severe heart valves injuries or diseases.[4] However, these valve substitutes still present some major drawbacks, including strong thromboembolic complications, extensive calcification, and inferior durability.[5, 6] Moreover, they cannot support tissue regrowth and remodeling after implantation, which are significantly important for pediatric patients.[7, 8]

The healthy extracellular matrix (ECM) of native valve leaflets presents a complex but highly organized tri-laminar architecture, i.e., fibrosa, spongiosa, and ventricularis.[1, 9] Dense collagen fibers with circumferentially aligned structures are dominant in the fibrosa layer in the aortic side. Randomly aligned proteoglycans are located in the spongiosa - the middle layer of the native valve ECM. Then, radially aligned elastin fibers are mainly involved in the ventricularis layer in the ventricular side. Importantly, the diameters of the collagen and elastin fibers exhibited in the ECM of native valve leaflets are in the nanometer scale, ranging from several to hundreds of nanometers.[10–12] The above-mentioned heterogeneous material components and structural features further result in anisotropic mechanical properties and biochemical and biophysical functions in the native valve tissues.[13, 14] With the synergetic development of science and technology, tissue engineering constitutes a promising and advanced approach for generating engineered valve scaffolds that facilitate the repair and regeneration of damaged or diseased valves.[5, 15] Therefore, an ideal engineered valve scaffold should resemble the heterogeneous morphology, structure, and properties of the native valve leaflet to the full extent. Most recently, electrospinning technique has been widely explored to develop nanofibrous scaffolds with EMC-biomimetic morphology and structure, and improved physicochemical and biological properties for various tissue engineering applications.[16–18]

It is well known that valvular interstitial cells (VICs) are the most important resident cell population in valve leaflet tissues.[19] VICs are widely located throughout all three layers of valve leaflets and play important roles in maintaining the valvular structure and function by synthesizing ECM proteins and secreting remodeling-associated enzymes.[20] Existing studies showed that more than 95% VICs present a quiescent fibroblast-like phenotype in healthy valve leaflets.[21] Once the pathological triggers are experienced, they may transform into pathological phenotypes, like myofibroblast-like phenotypes that have extensive expressions of myofibroblast-associated protein markers, such as α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA).[22, 23] During valvular calcification-related cases, the VICs also transform into osteoblastic phenotype with enhanced expressions of osteoblast-related markers, such as alkaline phosphatase (ALP), Runx2, and osteocalcin (OCN).[24, 25] It should be noted that many existing studies have demonstrated that the valve calcification is one of the most vital reasons that lead to the failure of artificial valve scaffolds after in vivo implantation.[26–28] Some previous studies found that age had an important influence on valvular calcification.[29] For instance, one study has already demonstrated that the younger women (<60 years old) showed less valve calcification than older women.[30] Therefore, an ideal engineered valve scaffold should provide the appropriate biophysical and biochemical microenvironments for cell regrowth and tissue formation while effectively preventing the occurrence of valve calcification and other diseases.

The aim of our present study is to design and develop novel tri-layered and gel-like nanofibrous scaffolds made of poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) and poly (aspartic acid) (PASP) composites to better mimic the native ECM of valve leaflet tissues. These nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds were generated based on a positive/negative conjugate electrospinning technique and a subsequent bioactive hydrogel formation process. This strategy was expected to combine the merits of a nanofibrous structure and a hydrogel material to provide a morphological, structural, and biomechanical heterogeneity. We hypothesized that the tri-layered, gel-like constructs could effectively mimic the anisotropic structure and mechanical properties of native valvular leaflets while simultaneously supporting cellular growth and preventing valvular calcification. Human aortic VICs (HAVICs) were employed as model cells to investigate the cell behaviors, including cell growth, proliferation, ECM production, and gene expression, when seeded on several nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds with different PASP contents. Moreover, we also isolated pulmonary valve leaflets from porcine hearts from two different age groups (~4–6 months vs. ~2 years) and further obtained young porcine pulmonary VICs (yPPVICs) and adult porcine pulmonary VICs (aPPVICs) from each group. The cultured yPPVICs and aPPVICs were seeded on our nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds to investigate the influence of age on the cell behaviors and ECM remodeling. This study provides guidance and reference of the design and development of novel tri-layered and gel-like nanofibrous scaffolds for heart valve tissue engineering application.

2. Results

2.1. Morphological analysis of electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds

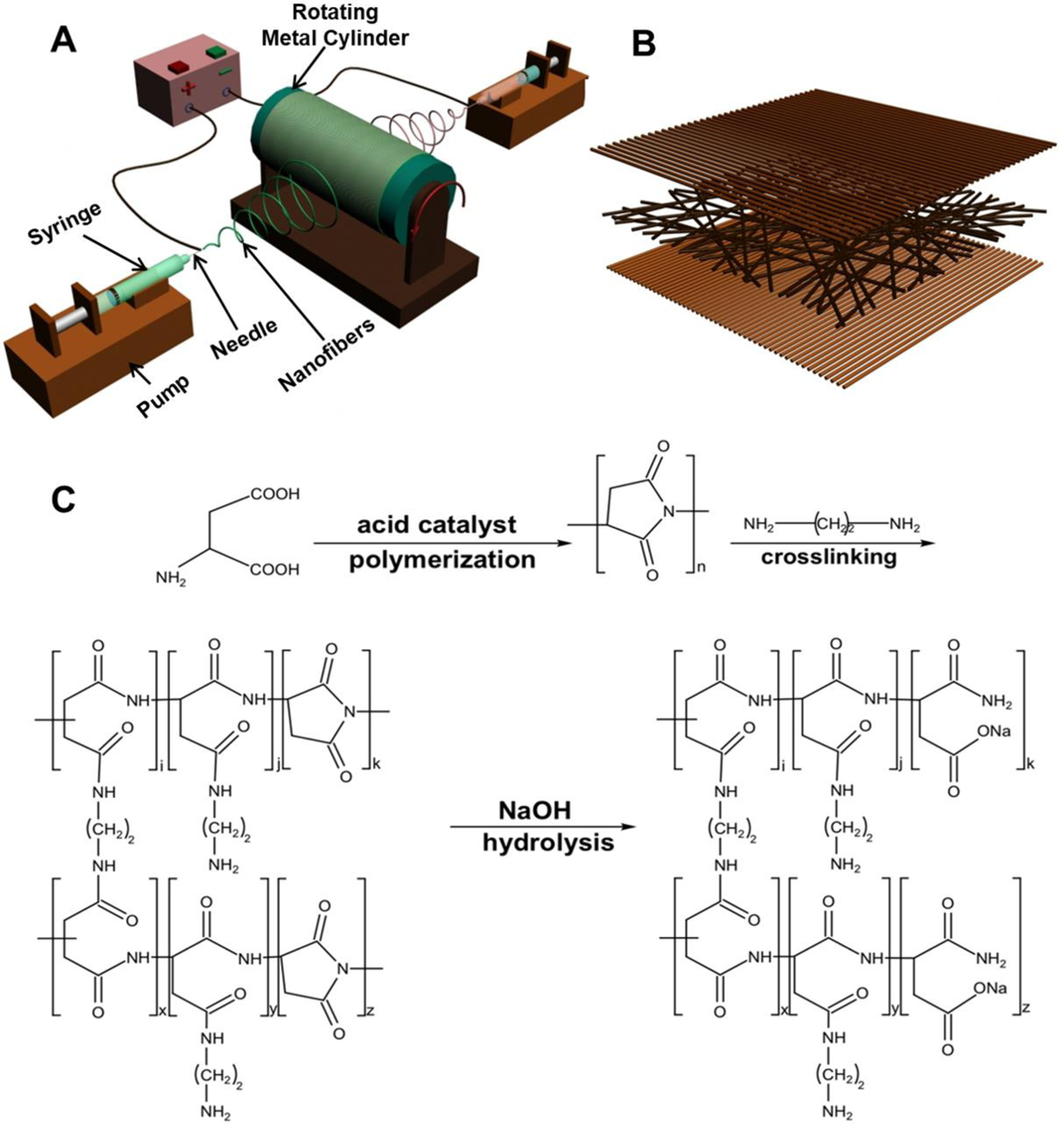

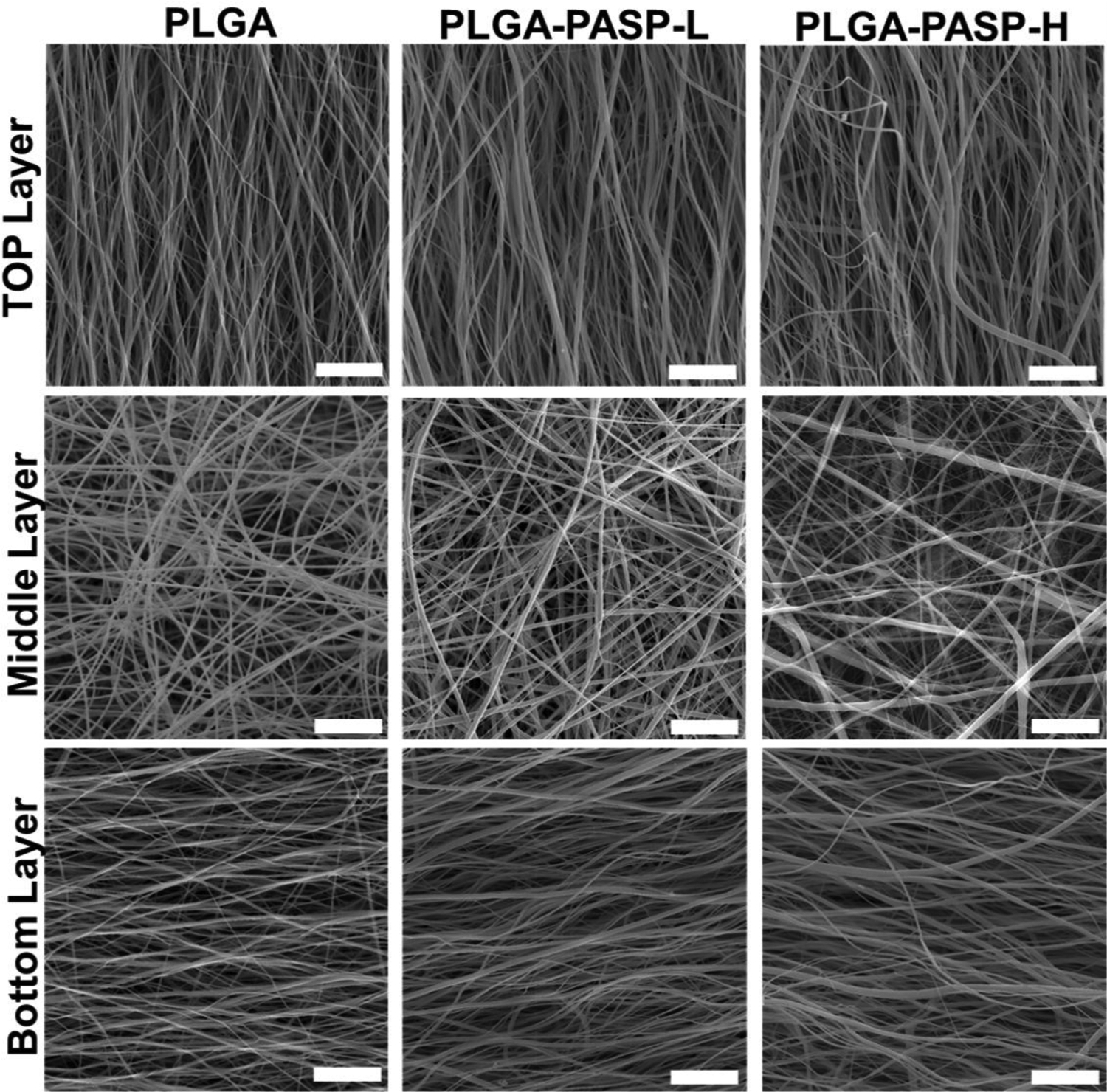

A combination of a positive/negative conjugate electrospinning process (Figure 1A) and subsequent bioactive hydrogel formation (Figure 1C) was employed to fabricate tri-layered, gel-like nanofibrous scaffolds (Figure 1B). The tri-layered structure was easily manipulated by using an electrospinning process with predetermined spinning parameters. To obtain the gel-like properties, polysuccinimide (PSI) was employed as the intermediate for the formation of a PASP hydrogel, which was incorporated into scaffolds with different contents. After crosslinking with ethylenediamine, some amide rings in the PSI macromolecular chains were opened and some crosslinking bonds were formed. Then, a NaOH solution was applied to partly open the remaining amide rings in the crosslinked PSI macromolecular chains, and the crosslinked PASP hydrogel component was obtained. The electrospun pure PASP mesh had hydrogel-like properties and could be easily extruded through a pipette tip (Supplemental Video 1). The two different as-obtained PLGA-PASP scaffolds were denoted as PLGA-PASP-L (Low PSI content; PLGA:PSI=2:1) and PLGA-PASP-H (High PSI content; PLGA:PSI=1:1), according to their original PSI contents. After the addition of PLGA, the hydrogel-like properties were maintained, but the meshes were not injectable. SEM images showed that the fibrous structures were similar for all the three different scaffolds (Figure 2). The fibers in the bottom layer presented an aligned structure along one direction, while the fibers in the middle layer exhibited random structure, and the fibers in the upper layer possessed an aligned structure aligned perpendicularly to the bottom layer. The tri-layered fibrous structures of the three as-prepared scaffolds better mimic the structural anisotropy of native valve leaflet tissue layers. The average fiber diameter was calculated (Supplemental Figure S1) and found to be 514.8±102.0 nm for PLGA scaffolds, 684.2±128.6 nm for PLGA-PASP-L scaffolds, and 818.8±158.6 nm for PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds, indicating that the introduction of the PASP component led to a significantly increased fiber diameter of the nanofibrous scaffolds. Some other studies also demonstrated that the spinnability of PASP was relatively inferior than some synthetic polymers, such as polycaprolactone (PCL) and PLGA, leading to an increase of the fiber diameter when a higher PASP content was utilized.[31, 32]

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic of the positive/negative conjugate electrospinning process. PLGA and PSI solutions were loaded into two different syringes placed opposite to each other, and separately electrospun to generate PLGA-PSI nanofiber scaffolds. (B) Schematic of tri-layered nanofibrous scaffolds. The fibers in the bottom layer presented an aligned structure along one direction, while the fibers in the middle layer exhibited random structure, and the fibers in the upper layer possessed an aligned structure aligned perpendicularly to the bottom layer. (C) Schematic of bioactive PASP hydrogel formation.

Figure 2.

SEM images of three different nanofibrous scaffolds with tri-layered structures made of different PLGA and PASP components: PLGA, PLGA-PASP-L, and PLGA-PASP-H. Scale bars=25 μm.

2.2. Mechanical characterizations of electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds

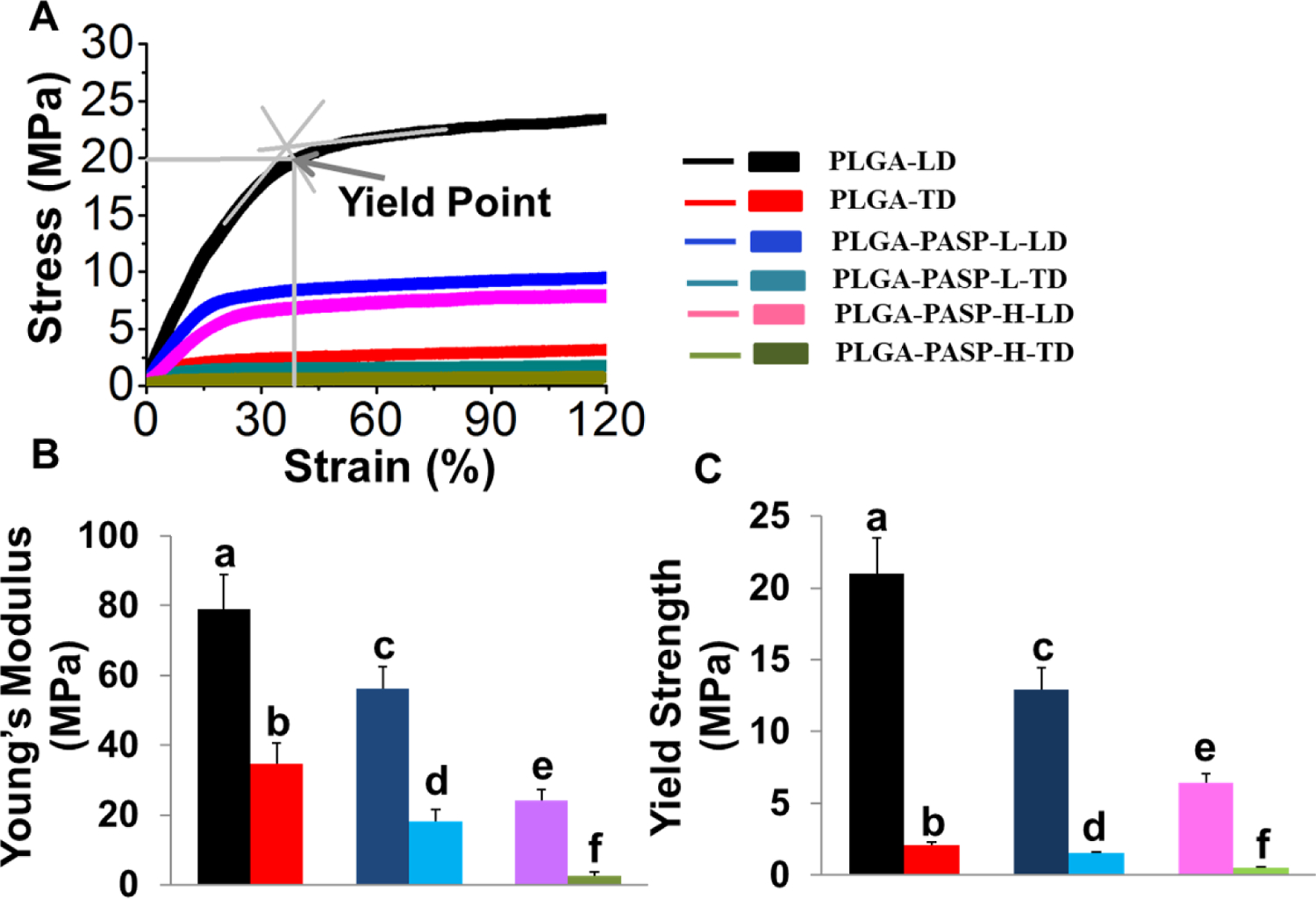

Mechanical measurements for PLGA, PLGA-PASP-L, and PLGA-PASP-H nanofibrous scaffolds were performed along both of the two principal axes, i.e., longitudinal direction (spinning time=6h) and transverse direction (spinning time=2h) (Figure 3). As expected, all three nanofibrous scaffolds exhibited anisotropic mechanics that resembled the native valve leaflet tissues. The tensile mechanical properties along the longitudinal and transverse directions were matched with the circumferential direction and radial direction of the native valve leaflet tissues, respectively. It was found that all the three scaffolds possessed similar stress-strain curves along both the longitudinal and transverse directions, consisting of one linear elasticity region and one subsequent yield platform region (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Mechanical properties of PLGA, PLGA-PASP-L, and PLGA-PASP-H nanofibrous scaffolds along two different directions, i.e., longitudinal direction (LD) and transverse direction (TD). (A) Typical stress-strain curves for the three different scaffolds. An illustration was made to explain how to calculate the yield point. (B) Young’s modulus and (C) Yield strength (n=6; bars that do not share letters exhibit significant difference among each other, p<0.05).

When comparing the mechanical behaviors along the longitudinal direction, the Young’s modulus for the nanofibrous PLGA scaffolds was highest (79.1±9.8 MPa), which was notably lower for the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-L scaffolds (56.3±6.1 MPa) and even lower for nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds (24.1±3.1 MPa) (Figure 3B). Similarly, the Young’s modulus along the transverse direction was also significantly decreased with increasing PASP contents, from 34.6±6.0 MPa for PLGA to 18.2±3.5 MPa and 2.6±1.0 MPa for PLGA-PASP-L and PLGA-PASP-H nanofibrous scaffolds, respectively. The yield point was recognized as the limit point for transferring from elastic deformation to plastic deformation in the stress-strain curves, which is extremely relevant to the recoverable deformability of scaffolds. The yield strength (the stress at the yield point) of the three different scaffolds was found to display a trend similar to the Young’s modulus results (Figure 3C). Again, the nanofibrous PLGA scaffolds possessed the highest yield stress (21.0±2.5 MPa) along the longitudinal axis, which was notably lower for PLGA-PASP-L (12.9±1.6 MPa), and even lower for PLGA-PASP-H (6.4±0.6 MPa). The values of the yield stress along the transverse direction were determined to be 2.1±0.2 MPa, 1.5±0.1 MPa, and 0.5±0.1 MPa for PLGA, PLGA-PASP-L, and PLGA-PASP-H nanofibrous scaffolds, respectively. These results showed that an increase of the PASP component significantly decreased the Young’s modulus and yield strength of the nanofibrous scaffolds.

2.3. Nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds promoted interaction and ECM remodeling of HAVICs

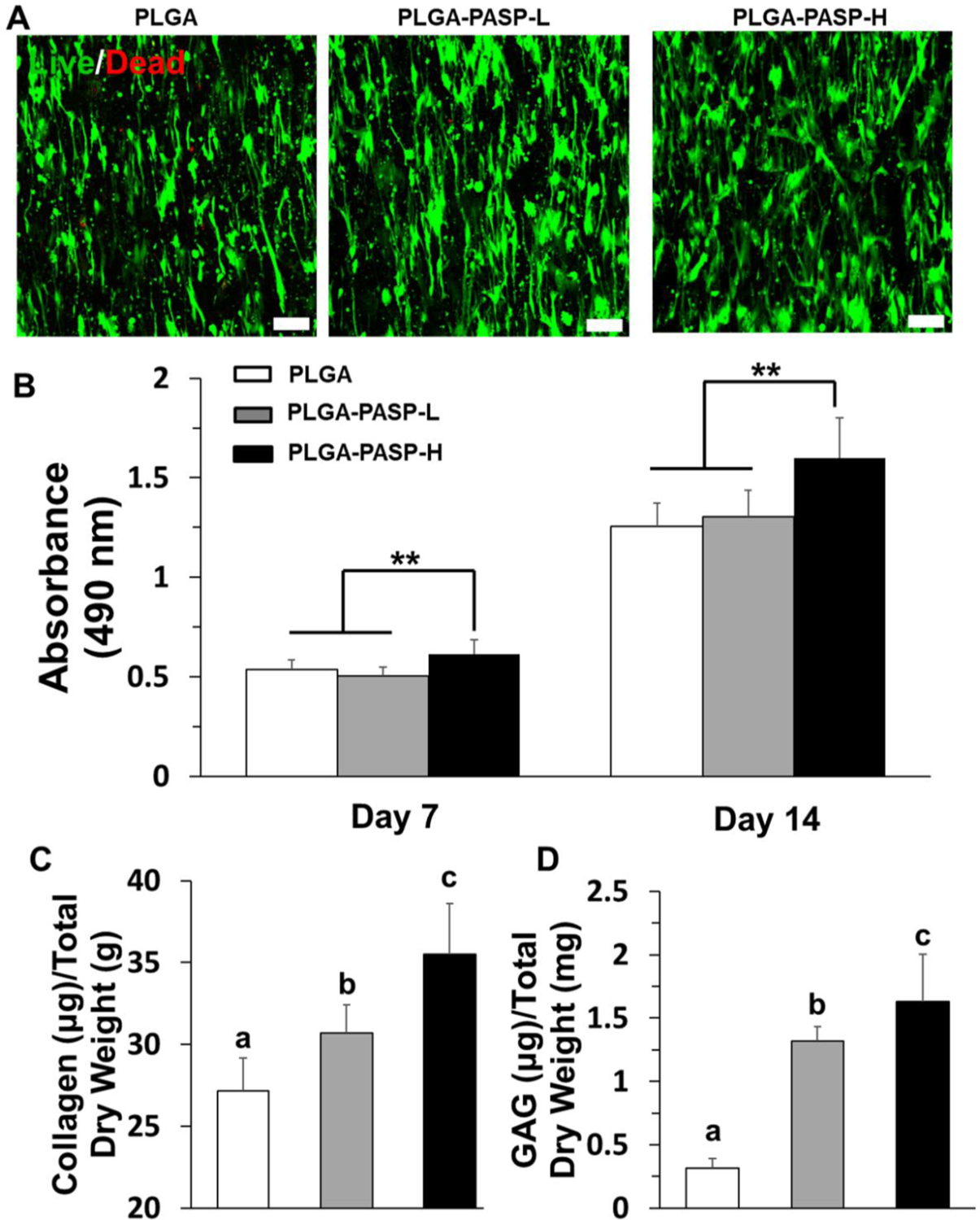

HAVICs were seeded and cultured on different nanofibrous scaffolds to investigate the influences of scaffold structures and components on the cell behaviors. The images of Live/Dead staining displayed that all the three nanofibrous scaffolds supported a high viability of HAVICs after 14 days of culture, and almost no dead cells with the red color were observed (Figure 4A). It was also found that most HAVICs cultured on the three different nanofibrous scaffolds reshaped, elongated, and aligned along the direction of the fiber alignment. The results from the MTT assay further demonstrated that the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds with a higher PASP hydrogel content significantly promoted the growth and proliferation of HAVICs in comparison with the PLGA and PLGA-PASP-L nanofibrous scaffolds at days 7 and 14 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

(A) Live & dead staining of HAVICs seeded on PLGA, PLGA-PASP-L, and PLGA-PASP-H nanofibrous scaffolds and cultured in growth medium (GM) for 14 days. Scale bars=100 μm. (B) MTT assay results of HAVICs seeded on the three different scaffolds throughout 14 days with GM (n=5, **p<0.01). (C) Collagen content and (D) GAG content characterization of HAVICs cultured on the three different scaffolds with GM on day 14 (n=5; bars that do not share letters exhibit significant difference among each other, p<0.05).

To further determine the ECM deposition and remodeling capacity of HAVICs seeded on the three different nanofibrous scaffolds, two biological tests were conducted to measure the total collagen and GAG contents after 14 days of culture (Figure 4C and D). The addition of PASP promoted the collagen and GAG deposition. Both the collagen and GAG contents in the PLGA-PASP-H nanofibrous scaffolds were found to be the highest among the three scaffolds. The HAVICs on the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-L scaffolds also expressed a significantly higher level of collagen and GAG than those on the nanofibrous PLGA scaffolds. These results confirmed our hypothesis that the addition of the PASP component into the proposed nanofibrous scaffolds positively affects the cell-scaffold interaction in terms of ECM secretion and deposition.

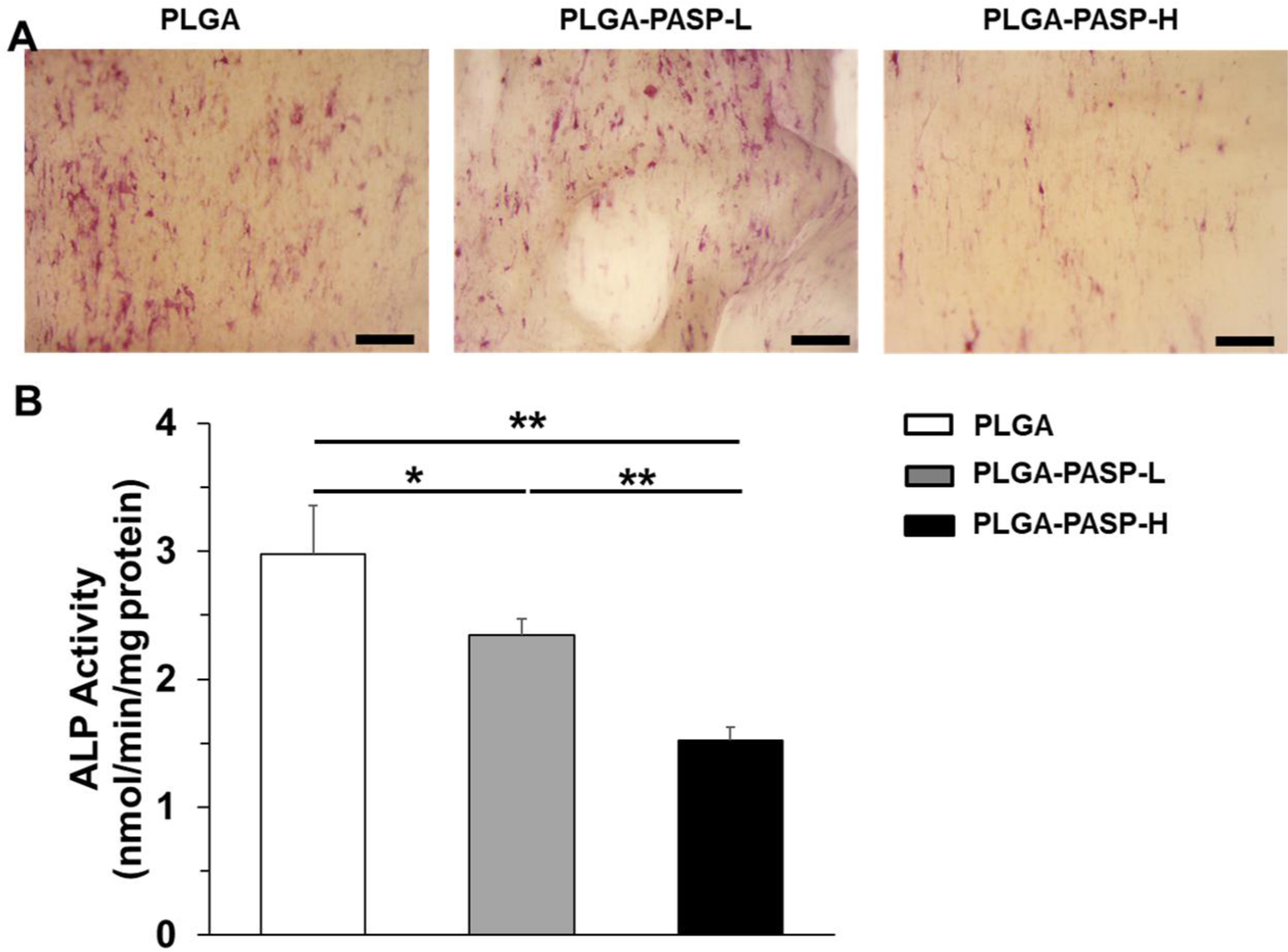

2.4. PLGA-PASP nanofibrous scaffolds inhibited osteogenic differentiation of HAVICs

The anti-calcification ability of engineered scaffolds is an assuredly important property for TEHVs.[25] HAVICs were seeded on different scaffolds and cultured in a pro-osteogenic environment, using osteogenic differentiation medium (ODM), for 14 days, to explore how the scaffold components affected the osteogenic differentiation of HAVICs. It was found that large areas of ALP staining, with a red color, were observed on both the PLGA and PLGA-PASP-L nanofibrous scaffolds (Figure 5A). In comparison, limited ALP staining was detected on the PLGA-PASP-H nanofibrous scaffolds. The results from quantitative analysis of ALP activity also showed that significant differences were found among the three different nanofibrous scaffolds (Figure 5B). The ALP activity of HAVICs detected in the nanofibrous PLGA scaffolds without the PASP component was highest. With the increase of the PASP content, the ALP activity of the HAVICs in the PLGA-PASP nanofibrous scaffolds significantly decreased. The results indicated that the ALP activity of HAVICs was obviously inhibited when more PASP was introduced into the nanofibrous scaffolds.

Figure 5.

(A) ALP staining of HAVICs seeded on PLGA, PLGA-PASP-L, and PLGA-PASP-H nanofibrous scaffolds and cultured in ODM for 14 days. Scale bars= 500 μm. (B) ALP activity on day 14 of HAVICs seeded on the three different scaffolds and cultured in ODM (n=5; *p<0.05, **p<0.01).

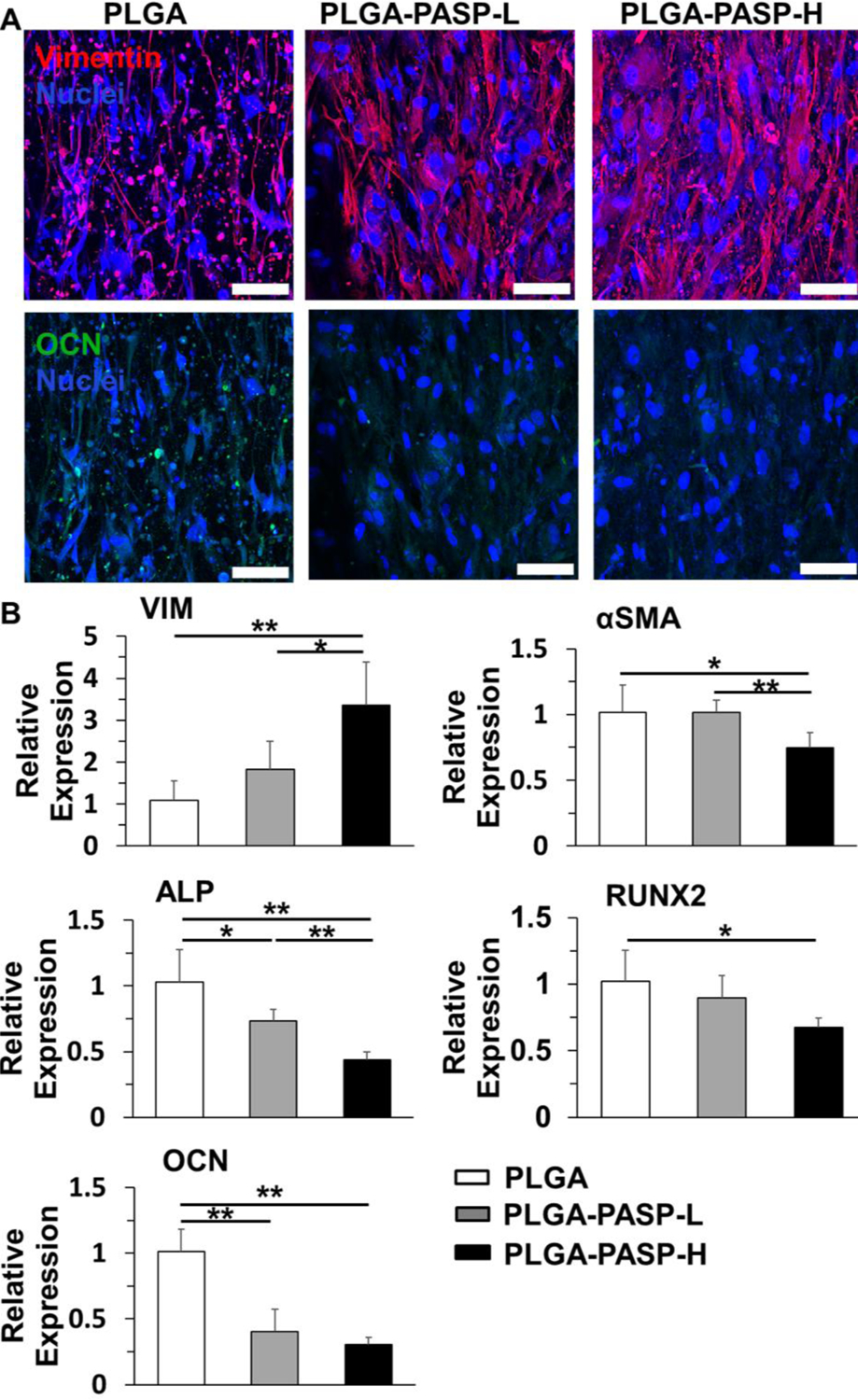

To further validate the phenotypic change of HAVICs seeded on the three different nanofibrous scaffolds in ODM, IF staining was carried out to visualize the expression of vimentin (the major protein marker for quiescent VICs) and osteocalcin (OCN, the late marker for osteogenic differentiation) (Figure 6A). The HAVICs cultured on the nanofibrous PLGA scaffolds had the lowest expression of vimentin but the highest expression of OCN. Conversely, with the incorporation of PASP, the HAVICs seeded on the two PLGA-PASP nanofibrous scaffolds exhibited improved vimentin expressions but significantly decreased OCN expressions. RT-qPCR analysis was utilized to determine the expression of five gene markers, including vimentin, α-SMA (a marker for activated VICs), ALP, Runx2 (an essential transcription factor for osteogenic differentiation), and OCN (Figure 6B). It was found that the HAVICs cultured on the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds significantly upregulated the expression of vimentin but downregulated the expression of α-SMA and ALP genes compared to the HAVICs conditioned on the PLGA and PLGA-PASP-L nanofibrous scaffolds. The HAVICs also presented significantly higher expression of Runx2 and OCN genes when cultured on the PLGA scaffolds compared to those conditioned on the PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds. Moreover, the expression of ALP and OCN genes for HAVICs cultured on nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-L scaffolds were found to be significantly lower than those conditioned on nanofibrous PLGA scaffolds. All these results demonstrated that the introduction of high PASP content into the nanofibrous scaffolds effectively reduced activation of HAVICs by promoting their quiescent fibroblastic phenotype and decreasing active myofibroblastic phenotype and inhibited the osteogenic differentiation of HAVICs.

Figure 6.

(A) IF staining of Vimentin (red), OCN (green), and nuclei (blue) for HAVICs seeded on PLGA, PLGA-PASP-L, and PLGA-PASP-H nanofibrous scaffolds and cultured in ODM for 14 days. Scale bars= 100 μm. (B) mRNA expression on day of HAVICs seeded on the three different nanofibrous scaffolds and cultured in ODM 14 (n=3; *p<0.05, **p<0.01). HAVICs seeded on nanofibrous PLGA scaffolds were utilized as control groups.

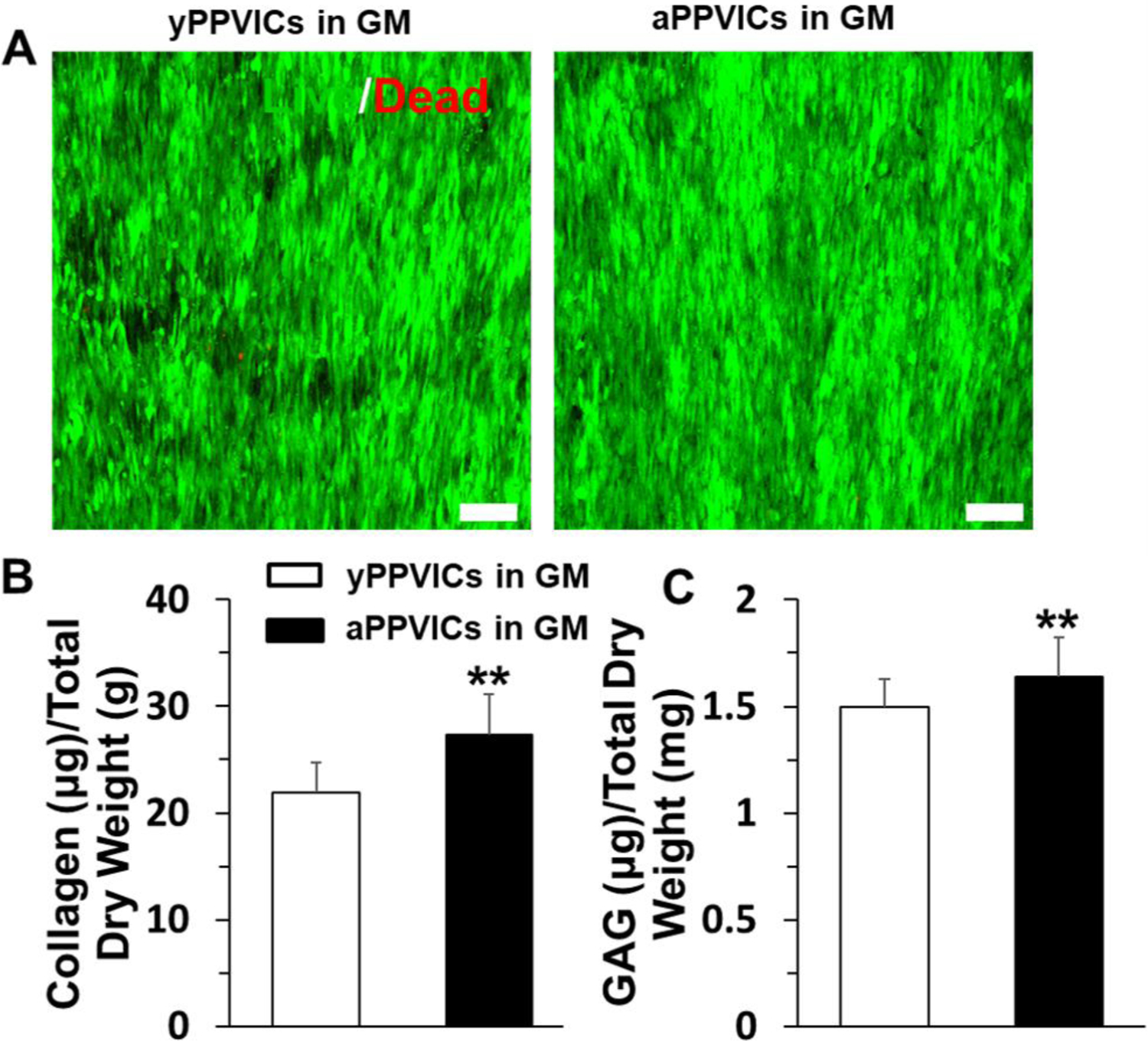

2.5. The aPPVICs secreted more collagen and GAG contents than the yPPVICs when both cultured on the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds

Two different types of porcine VICs, i.e., yPPVICs and aPPVICs, were harvested and isolated from young pigs (~4–6 months) and adult pigs (~2 years) and were separately seeded on the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds to investigate the interaction and ECM remodeling capacities of VICs with significant age differences. Live/dead staining showed that both yPPVICs and aPPVICs presented high viabilities and high levels of cell alignment when cultured on the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds at day 14 (Figure 7A). The ECM component tests showed that both collagen and GAG contents extracted from the yPPVIC-seeded nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds were significantly lower than those from their aPPVIC-seeded counterparts after 14 days of culture (Figure 7B). These indicated that the age significantly affected the ECM remodeling ability of VICs when seeded on the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds.

Figure 7.

(A) Live & dead staining of yPPVICs and aPPVICs seeded on nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds and cultured in GM for 14 days. Scale bars=100 μm. (B) Collagen content and (C) GAG content characterization on day 14 of HAVICs cultured on the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds with GM (n=5; **p<0.01).

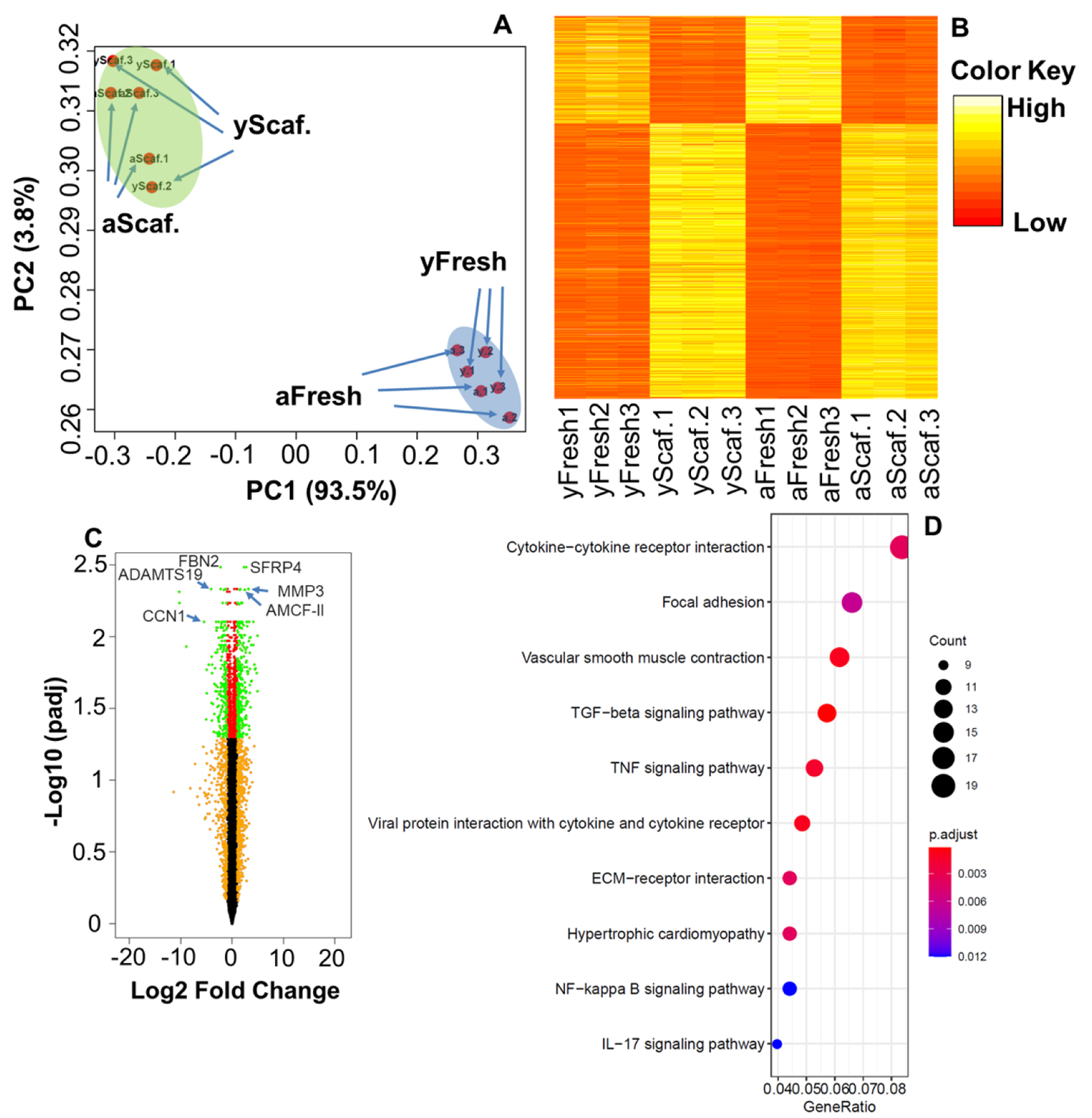

2.6. RNA sequencing analysis

We further conducted global RNA sequencing to compare the gene expression differences of yPPVICs and aPPVICs after being cultured on nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds for 14-days in GM (denoted as yScaffold and aScaffold). The freshly isolated cells without 2D expansion and scaffold seeding were used as a control (denoted as yFresh and aFresh). Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to compare the transcriptional profiles and similarities across the four groups (i.e., yFresh, aFresh, yScaffold, and aScaffold). The PCA of overall gene expression data showed that the first principal component (PC1) and the second principal component (PC2) accounted for 93.5% and 3.8% of the total variance, respectively. All the freshly isolated PPVICs were clustered together in the scatter plot of the PCA, which were completely separated from the groups cultured on nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds (Figure 8A). A heatmap of all the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) among four groups also confirmed that yFresh and aFresh had similar expression patterns, while yScaffold and aScaffold displayed similar transcriptional profiles (Figure 8B). A volcano plot was generated to evaluate the gene expression variation between the yScaffold and aScaffold groups (Figure 8C). It showed that 88 genes were significantly upregulated, and 78 genes were significantly downregulated in the aScaffold group. Among these genes, secreted frizzled related protein (SFRP) 4, matrix metallopeptidase (MMP) 3, and alveolar macrophage chemotactic factor 2 (AMCF-II) were significantly upregulated in the aScaffold group, while fibrillin (FBN) 2, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS) 19, and cellular communication network factor (CCN) 1 were downregulated. SFRP4 is a class I antagonist of the Wnt signaling pathways and has been reported to have anti-proliferative effects and reduce fibrosis.[33, 34] AMCF-II (or CXCL5) is a member of the CXC chemokine family and is associated with inflammation and valve calcification.[35] Both MMP and ADAMTS are major proteinase enzymes that are required for heart valve development, repair, and remodeling. MMP3 degrades several types of collagen (II, III, IV, IX, and X), proteoglycans, fibronectin, laminin, and elastin.[36] It has been reported the activities of MMP3 were upregulated in pathological valve tissues[37] and VICs[38]. The functions of ADAMTS19 are not fully understood. Very recent studies showed that a loss of ADAMTS19 caused aortic valve dysfunction.[39, 40] The Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis was used to identify significantly enriched pathways in DEGs. Figure 8D shows the top 10 upregulated signaling pathways in the aScaffold group. Several of these signaling pathways, including vascular smooth muscle contraction, TGFβ signaling pathway, TNF signaling pathway, and NF-kappa B signaling pathway, were reported to play important roles in inducing pathological activation and calcification of valvular cells.[41–44]

Figure 8.

(A) Principal component scatter plot showing the overall similarity of gene expression among four groups; PC1 accounted for 93.5% of the variance, and PC2 accounted for 3.8% of the variance. (B) Heatmap of all the differentially expressed genes among the four groups. (C) Volcano plot (aScaffold vs. yScaffold); Genes with adjusted p ≤ 0.05 and log2 FC ≥2 or ≤−2 were identified as significantly differently expressed. (D) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of upregulated genes (aScaffold vs. yScaffold). n=3 for each group.

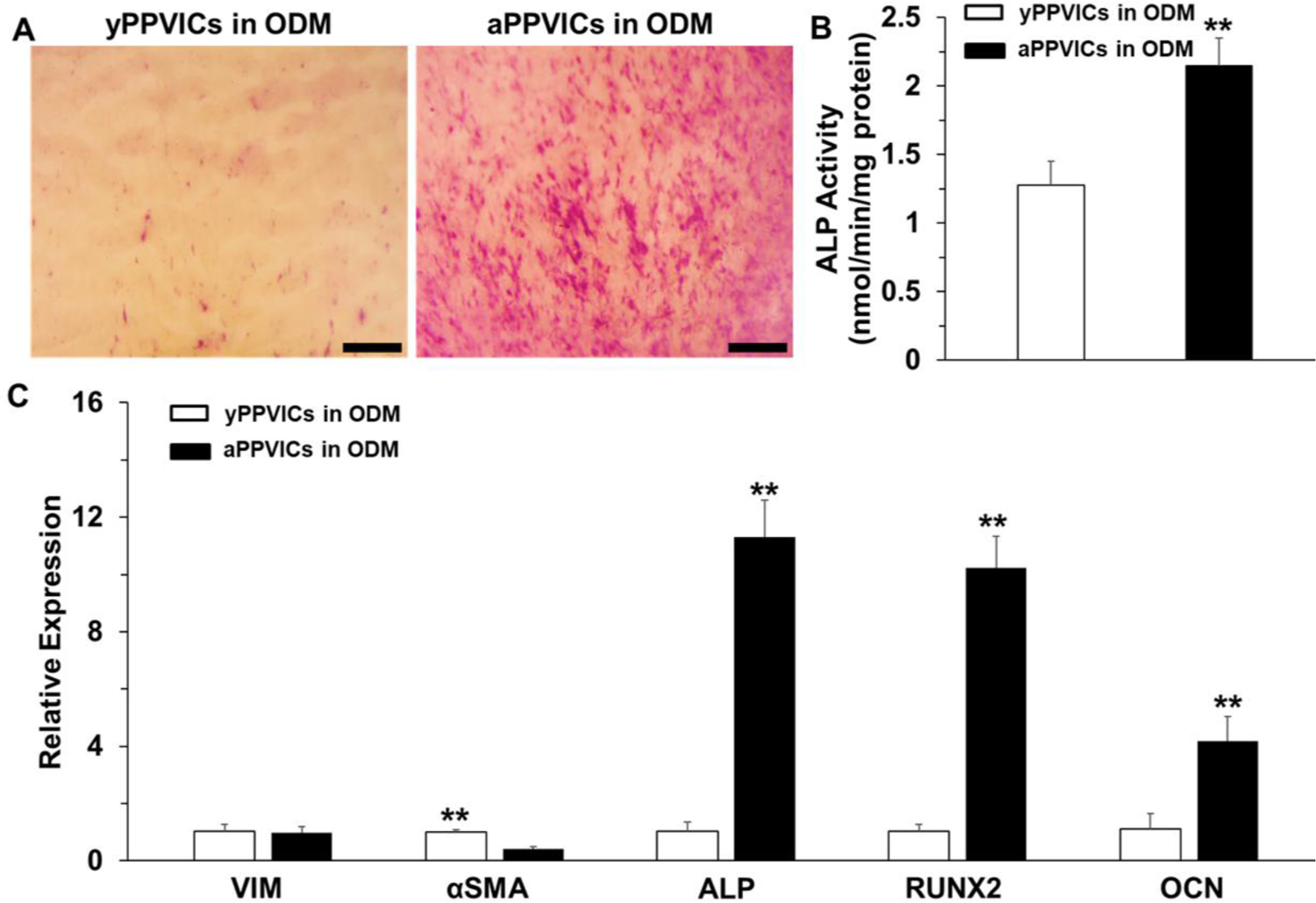

2.7. The aPPVICs exhibited higher levels of osteogenic differentiation than the yPPVICs when induced by pro-osteogenic conditions

The yPPVICs and aPPVICs were seeded separately on nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds and cultured in ODM for 14 days to determine the effects of the ages of VICs on osteogenic differentiation. The ODM induction did not affect PPVIC viability (Supplemental Figure S2), and both yPPVICs and aPPVICs in ODM expressed high levels of αSMA protein (Supplemental Figure S3), indicating that both of these two different cells were activated. The images of ALP staining showed that aPPVICs presented positive ALP staining, while the yPPVICs were mostly negative to ALP staining, with very limited ALP expression being observed (Figure 9A). The results from the ALP activity test also demonstrated that aPPVICs cultured on the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds had a significantly higher ALP activity than the yPPVICs (Figure 9B). The RT-qPCR results were consistent with the previous ALP analysis. The aPPVICs exhibited much higher levels of osteogenic differentiation than yPPVICs by significantly upregulating the osteoblast-associated gene markers, including ALP, Runx2, and OCN (Figure 9C). These results supported the hypothesis that the young VICs could inhibit and delay the osteogenic differentiation, in comparison with the adult VICs, when seeded on the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds.

Figure 9.

(A) ALP staining, (B) ALP activity (n=5; **p<0.01), and (C) mRNA expression (n=3; **p<0.01) of yPPVICs and aPPVICs seeded on nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds and cultured in ODM for 14 days. Scale bars= 500 μm. HAVICs seeded on nanofibrous PLGA scaffolds were utilized as control groups for mRNA expression analysis.

3. Discussion

Native valve leaflet tissues possess 3D complex ECM structures with three layers, which dictate their anisotropic mechanical characteristics and their biochemical and biophysical functions.[45, 46] Therefore, ideal TEHV leaflets should duplicate the structural features of the natural valvular leaflet ECM.[47–49] In the present study, we designed and implemented 3D tri-layered nanofibrous scaffolds to replicate the native trilaminar architecture of valvular leaflet ECM. The first layer (i.e., the bottom layer, mimicking the ventricularis layer) was electrospun to generate aligned nanofibers along one direction. The second layer (i.e., the middle layer, mimicking the spongiosa layer) was constructed with randomly oriented nanofibers. The last layer (i.e, the upper layer, mimicking the fibrosa layer) was composed with aligned nanofibers oriented along the direction perpendicular to the first layer.

The choice of biomaterials for the fabrication of the scaffold is critical for heart valve tissue engineering because the native valvular leaflet ECM is mainly composed of collagen, elastin, and proteoglycans, resulting in gel-like properties.[50] PASP is a synthesized poly(amino acid) with a protein-like amide bond as every repeating unit in its macromolecular backbone. Due to its great biocompatibility, controlled biodegradability, and excellent biological functions, PASP has been widely used as a hydrogel-forming biopolymer for fabricating tissue engineered scaffolds and drug delivery carriers.[51, 52] However, its poor mechanical properties and inferior processibility restrict its use in high-performance biological scaffolds. As a comparison, PLGA is one of the most widely utilized synthetic polymers, offering great biocompatibility, adjustable bioabsorption, and excellent mechanical properties and processibility. It has also been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States.[53] Unfortunately, poor hydrophilicity and inferior biological properties have limited its applications. Existing studies showed that blending two or more different polymers is a simple and versatile strategy for combining the desirable characteristics from different polymers.[54, 55] In our present study, a mixture of PLGA and PASP was employed to fabricate the tri-layered nanofibrous scaffolds for TEHV application, which not only exhibited improved mechanical properties from the PLGA component but also possessed enhanced biological properties from the PASP component.

The mechanical performances of engineered scaffolds are also decisive factors for heart valve tissue engineering application because the TEHVs should be subjected to sustained dynamic blood circulation in vivo.[56] The mechanical properties of heart valve leaflets significantly rely on the tensile direction, valve types and ages, and individual differences.[57–59] For instance, our previous study investigated the differences of the mechanical performances of heart valve leaflets between young pigs (~4–6 months) and adult pigs (~2 years).[59] The results demonstrated that the heart valve leaflets from both young and adult pigs presented obvious mechanical anisotropy, and the mechanical properties along the circumferential direction are significantly higher than those along the radial direction. The Young’s moduli along the circumferential direction were calculated to be 2.3±1.2 MPa and 10.0±4.9 MPa for young pigs and adult pigs, respectively, while the Young’s moduli along the radial direction were calculated to be 0.8±0.4 MPa and 3.8±2.2 MPa for young pigs and adult pigs, respectively. The ultimate strengths along the circumferential direction were calculated to be 8.2±1.2 MPa and 10.7±1.7 MPa for young pigs and adult pigs, respectively, while the ultimate strengths along the radial direction were calculated to be 1.3±0.3 MPa and 1.8±0.6 MPa for young pigs and adult pigs, respectively. Our present study demonstrated that our tri-layered, gel-like nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds presented a mechanical anisotropy similar to the native valve leaflets. The tensile mechanical performances along the longitudinal and transverse directions of the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds were in the same order of magnitude with the circumferential and radial directions of the native valve leaflets, respectively. Importantly, we also demonstrated the feasibility of adjusting the mechanical properties of nanofibrous scaffolds by changing the PASP content. On the other hand, pure PLGA scaffolds had much higher Young’s modulus and strength than their counterparts with PASP. Several previous studies, including our own, have demonstrated that a local stiffness that is higher than the physiological range is intended to induce VIC activation and calcification under a pathological environment.[22, 60, 61] 3D culture of HAVICs within hydrogels or on fibrous scaffolds may induce retraction due to pathological activation of HAVICs.[61, 62] In our current study, no obvious contraction or shape change of our scaffolds with or without PASP was observed. This is probably because (1) our scaffolds may have sufficient mechanical properties to resist the cell-based contraction; (2) the seeded cells did not yet generate sufficient contraction force.

The design of a scaffold for optical TEHVs should provide appropriate biological functions that support cell activities and promote ECM deposition and remodeling.[63] In this study, we combined positive/negative conjugate electrospinning with a subsequent bioactive hydrogel formation process to fabricate nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds with different PASP contents. The nanofibers that exist in the scaffolds better replicate the architecture and size scale of collagen and elastin fibrils in the ECM of native valve leaflets. Our study demonstrated that all the three different types of VICs, including HAVICs, yPPVICs, and aPPVICs, grew very well on our nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds. Meanwhile, it was found that increasing the PASP content in the nanofibrous scaffolds significantly enhanced the proliferation of HAVICs because the PASP content imparted the scaffolds with a protein-like microenvironment. We also found, in agreement with previous studies, that the highly aligned fibrous structure in the scaffolds could induce the elongation and orientation of seeded VICs by the contact guidance phenomenon.[64, 65] The cellular alignment is especially useful in promoting the oriented deposition of regenerated ECM. The present study evaluated the deposition of total collagens and GAGs by HAVICs when seeded on different nanofibrous scaffolds and found that the PASP content significantly influenced the ECM secretion capacity. We also compared the ECM remodeling and regulation abilities of two porcine VICs when cultured on the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds. The results showed that aPPVICs conditioned on the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds possessed higher collagen and GAG contents than the yPPVICs, indicating that age difference is also a key factor for the ECM remodeling during the development of TEHVs.

The TEHVs will experience a complex in vivo microenvironment after implantation, and the pathological activation and further calcification phenomenon are the primary reasons responsible for the failure of implanted TEHVs.[66, 67] Therefore, ideal TEHVs should have great capacities to reduce cell activation and inhibit calcification. In this study, we tested and compared the levels of osteogenic differentiation of HAVICs when seeded on different nanofibrous scaffolds. It was demonstrated that the anti-osteogenic differentiation level of HAVICs increased with increasing PASP content. Our study confirmed the feasibility of introducing the PASP hydrogel material into the nanofibrous PLGA scaffolds to prevent the osteogenic differentiation and calcification in vitro. It also suggested distinct advantages of nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds for the development of advanced TEHVs. One possible reason for the anti-calcification is probably due to the decrease of the local stiffness and alteration of the biophysical and biochemical properties of the surface. The native-like gel properties originating from the PASP component should be a key factor for improving the anti-calcification capacity of the scaffold, and the detailed mechanisms will be further explored and illustrated in the future.

For TEHV design and application, the ages of the regeneration target and cell sources should also be taken into consideration. In our previous study, we demonstrated that both young and adult pig pulmonary valve (PV) leaflets had both similar and distinct protein and gene expression patterns. Adult PV leaflets and PVICs expressed much more osteogenesis-related and ECM remodeling proteins/genes than their young counterparts.[68] In this study, we also found that the yPPVICs seeded on the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds exhibited an obviously higher anti-calcification level than the aPPVICs, which is consistent with previous observations. Interestingly, we found that both freshly isolated yPPVICs and aPPVICs had similar gene expression patterns, which were quite different after they experienced 2D culture, passaging, and further maintenance on the nanofibrous scaffolds. Wang et al. also demonstrated that tissue-culture polystyrene culturing altered the transcriptional profile of VICs and activated the PI3K pathway.[69] Our current study showed that the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds could not reverse the gene expression profile alterations after 2D expansion. This indicates that effective cell expansion and maintenance strategies are important and necessary for preventing cellular phenotypic alterations. When comparing the gene expression patterns of yPPVICs and aPPVICs on nanofibrous PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds, we found that aPPVICs upregulated several signaling pathways that are highly related to pathological valve activation, inflammation, and calcification. This demonstrates that cell sources from younger donors may be more suitable for TEHVs. Therefore, this study provided useful guidance for developing age-specific TEHVs. It is envisioned that our tri-layered, gel-like nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds may open a new window for designing and developing TEHVs. Further in vivo studies should be carried out to confirm the performance of nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds in pre-clinical animal models.

4. Conclusion

In this work, a series of nanofibrous scaffolds with different PASP ratios were developed through a combination of positive/negative conjugate electrospinning and bioactive hydrogel processing. All the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds exhibited tri-layered structures and anisotropic mechanical properties, which mimic native heart valve leaflet tissues. The incorporation of PASP into the nanofibrous PLGA scaffolds notably enhanced the adhesion, proliferation, and ECM remodeling of HAVICs, as well as the anti-calcification performance. It was also found that the aPPVICs exhibited a lower calcification resistance capacity than the yPPVICs when both were seeded and cultured on the nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds, indicating that age was an extremely pivotal factor. This study provided important guidance and reference for the design and development of 3D tri-layered, gel-like nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds for TEHV application.

5. Experimental Section/Methods

Fabrication of electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds:

PSI (Mw=31,500) was synthesized via the thermal polymerization of L-aspartic acid (Aladdin Industrial Corporation) with 85% phosphoric acid (Aladdin Industrial Corporation) used as a catalyst. The polymerization process was carried out at 180 °C under a reduced pressure conditions for 4 h in a rotary evaporator with a rotary speed of 120 rpm, according to our previous studies.[70, 71] Then the as-prepared PSI was washed, dried, and further dissolved in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, Acros Organics), resulting in a concentration of 30 % (w/v) solution. The PSI solution was stirred overnight at room temperature until a homogeneous spinning solution was obtained. The PLGA solution (15% w/v) was prepared by dissolving PLGA powder (LA/GA=82/18, Corbion Purac) in hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP, Acros Organics). A positive/negative conjugate electrospinning device (Figure 1A) was designed and implemented, in which aluminum foil was lifted and rotated at different predetermined angles (0° and 90°) on a cylinder collector with adjustable rotation speeds (1700 rpm and 100 rpm), in order to fabricate tri-layered hybrid nanofibrous scaffolds (Figure 1B). The first layer (i.e., the bottom layer) was electrospun to generate nanofibers aligned along one direction. The second layer (i.e., the middle layer) was constructed with randomly-oriented nanofibers. The last layer (i.e, the upper layer) was composed with aligned nanofibers oriented perpendicular to the first layer. As shown in Figure 1A, the PLGA and PSI solutions were loaded into two syringes placed opposite to each other, both with 18G needles. Two syringe pumps were employed separately to provide the two metal needles with adjustable flow rates of the polymeric solutions. A high voltage supply was utilized to provide positive and negative voltages for the oppositely placed metal needles, respectively. A rotating metal cylinder collector was placed in the middle of the two needles to collect the oppositely charged PLGA and PSI nanofibers. To adjust the weight ratio of PLGA and PSI nanofibers in the scaffold, the flow rate of PLGA solution was fixed at 1.6 mL/h, and two different flow rates, i.e., 0.4 mL/h and 0.8 mL/h, were utilized for PSI solution to blend the PLGA nanofibers and PSI nanofibers at different weight ratios (e.g., 2:1 and 1:1). The other spinning parameters were kept the same. In detail, the distance between the two needles, applied voltages of the two needles, and the rotating speed of the cylinder collector for the uniaxially aligned structures and randomly aligned structures were maintained at 20 cm, ±11 kV, and 1700 rpm and 100 rpm, respectively. The spinning times of bottom layer, middle layer, and upper layer were set at 2h, 12h, and 6h, respectively. Tri-layered, nanofibrous PLGA scaffolds without PSI were also fabricated as a control group. Two syringes were each loaded with PLGA solution, and the solution flow rate of both syringes were fixed at 1.6 mL/h. The other parameters were kept the same as the fabrication of nanofibrous PLGA-PSI scaffolds. After the electrospinning process, the two types of scaffolds with PSI were crosslinked in 0.3 mol/L ethylenediamine solution (in water/ethanol (1/1, v/v)) and hydrolyzed in 0.1 mol/L NaOH solution in order to convert PSI into poly (aspartic acid) (PASP, a protein-like hydrogel material) (Figure 1C). Gel-like nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds were eventually generated. The two nanofibrous PLGA-PASP scaffolds were washed several times and then lyophilized for further application.

Physical characterization of electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds:

The morphological assessments of all the scaffolds, including PLGA scaffolds, PLGA-PASP-L scaffolds, and PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds, were carried out by using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, FEI Quanta 200). A gold sputtering process was performed to coat the scaffold specimens with a thin layer of gold before the SEM observation. Image J software (NIH, USA) was employed to measure and calculate the mean fiber diameter of different scaffolds from the as-taken SEM images. A tensile strength tester (CellScale) was utilized to characterize the mechanical properties of the different scaffold samples in the wet condition. The samples were cut into rectangular shapes (L × W= 30 mm × 10 mm) in two different orientations, i.e., longitudinal direction (the direction of fiber alignment in the upper layer of the scaffolds, spinning time=6h) and transverse direction (the direction of fiber alignment in the bottom layer of the scaffolds, spinning time=2h). Before the mechanical test, the samples were immersed into PBS solution (pH = 7.4) at 37 °C for 5 min. The tensile experiments were performed with the same gauge length of 10 mm and the same movement rate of 10 mm/min. The Young’s modulus, yield strength, and yield elongation were analyzed using the typical stress-strain curves, and the calculation methods are shown in Figure 3A.

Isolation, seeding, and culturing of HAVICs, yPPVICs, and aPPVICs:

HAVICs were isolated from human aortic valve leaflets with the donor’s consent as approved by the Institutional Review Board of Weill-Cornell Medical College in New York City, as described previously.[72, 73] Fresh female porcine hearts were obtained from Tissue Source LLC and delivered overnight. The PVs from young (~4–6-months) and adult (2-years) pigs were harvested and two different PPVICs, i.e., yPPVICs and aPPVICs, were isolated, as described previously.[59, 74] HAVICs were cultured in an HAVIC GM, which consisted of MCDB131 medium (Sigma), 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen), 1 % penicillin/streptomycin (P/S, Invitrogen), 0.25 μg/L recombinant human fibroblast growth factor basic (rhbFGF, PeproTech), and 5 μg/L recombinant human epidermal growth factor (rhEGF, Invitrogen).[73] Both yPPVICs and aPPVICs were cultured in a PVIC growth medium (GM), which contained Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Invitrogen, USA), 10% FBS, and 1% P/S.[59] HAVICs were utilized at passages 4–6, and both yPPVICs and aPPVICs were used at passages 2–4. All the cell culture experiments were performed in a 5% CO2 contained atmosphere at 37 °C. The medium was changed every two days. Before seeding the cells, all the scaffold samples were cut into 10 mm × 10 mm squares and sterilized in 70% (v/v) ethanol overnight. After washing them three times in sterilized phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution, they were further immersed in the corresponding GM overnight. The cells were seeded onto the top layer of scaffolds at a density of 1×105 cells per sample. The medium was replaced with fresh medium every two days until the predetermined time points arrived.

Osteogenic induction of VICs seeded scaffolds:

VICs (HAVICs, yPPVICs, or aPPVICs) were seeded on the nanofibrous PLGA, PLGA-PASP-L, and PLGA-PASP-H scaffolds and cultured in an ODM for 14 days. The ODM for HAVIC induction contained MCDB131 medium, 10 % FBS, 1 % P/S, 100 nM dexamethasone (Sigma, USA), 10 mM β-glycerophosphate (Sigma, USA), and 50 μM ascorbic acid (Sigma, USA). The ODM for both yPPVIC and aPPVIC induction consisted of DMEM medium, 10 % FBS, 1 % P/S, 100 nM dexamethasone, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 50 μM ascorbic acid. The ODM was changed every two days until the predetermined time point reached.

Cell viability and proliferation characterizations:

A fluorescence-based Live/Dead assay (Invitrogen) was performed to visualize the cell viability and morphology when seeded on all the different scaffolds, as described previously.[75, 76] The stained samples (green fluorescence for living cells and red fluorescence for dead cells) were observed with a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM, LSM 710, Carl Zeiss). An MTT assay (Sigma) was employed to characterize the cell proliferation when seeded on different scaffold samples throughout 14 days of culture. At predetermined time intervals, the cell-scaffold constructions were transferred into a 24 well plate, and 1mL of medium with 100 μL 5mg/ml of MTT solution were added. The liquid was discarded after 4 h of incubation, and 500 μL/well of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were further added to fully dissolve the as-formed formazan crystals. After that, 100 μL of formazan-DMSO solution were transferred to a 96 well plate, and a microplate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments) was utilized to test the absorbance value at the 490 nm wavelength.[77]

GAG and collagen analysis:

The different VIC-seeded scaffolds were lyophilized and weighed after 14 days of culture in GM. The total collagen and GAG components were determined, according to our previous reports.[61, 73] A hydroxyproline assay was employed to determine the collagen content. Briefly, the samples were hydrolyzed in 4.8 N HCl solution at 100 °C for 2 h. The hydrolyzates that were obtained were dried overnight, and chloramine T reagent was added for oxidation at room temperature for 25 min. After that, Ehrlich’s aldehyde reagent was added to each sample at 65 °C for 20 min. to fully develop chromophores. A microplate reader was used to read the absorbance value at 550 nm to measure the amount of hydroxyproline. The total collagen content was calculated based on the assumption that the hydroxyproline accounted for 12.5% of the collagen. The sulfated GAG content was quantified by a Dimethylmethylene blue (DMMB) assay. The samples were immersed in the extraction solution (300 μg/ml papain, 5 mM cysteine, and 5 mM EDTA in 50 mM phosphate buffer with a pH value of 6.5) at 60 °C for 16h. Then the DMMB dye solution was added to each sample for 30 min. to form GAG-DMMB complexes. Eventually, the complex dissociation reagent containing guanidine hydrochloride and sodium acetate trihydrate was added to dissolve all the GAG-DMMB complexes, and the values were measured with a microplate reader at a wavelength of 656 nm.

ALP staining and ALP activity characterization:

An alkaline phosphatase leukocyte kit (Sigma) was employed to stain the expressed ALP when the VICs were seeded on different scaffolds and exposed to ODM for 14 days. The ALP activity was determined according to our previous studies.[73, 78] Briefly, a lysis buffer was used to lyse the different VIC-seeded scaffolds, and a p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP)-containing ALP substrate solution (Sigma) was added at 37 °C for 10 min. The reaction was terminated by adding a 3 N NaOH solution, and the amount of p-nitrophenol formation in the presence of ALPase was characterized by a microplate reader at a wavelength of 405 nm. A BCA assay kit (Pierce) that uses bovine serum albumin as the calibrating standard was employed to determine the total protein amount. The ALP activity was presented as μmol of p-nitrophenol formed per minute per milligram of total proteins (μmol/min/mg protein).

Immunofluorescent (IF) staining:

The VIC-seeded constructs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, treated with 0.2% Triton X100 for 10 min at room temperature, and further blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) overnight at 4 °C. After that, the samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies to vimentin (mouse monoclonal anti-vimentin, Invitrogen) and osteocalcin (OCN, rabbit monoclonal anti-osteocalcin, Abcam). Then the samples were treated with secondary fluorescent antibodies for 2 h at room temperature and subsequently processed with Draq 5 nuclear dye for 30 min at room temperature. Finally, the stained samples were observed with a CLSM (LSM 710, Carl Zeiss).

Gene expression assay:

Total RNA was extracted from VIC-seeded samples after 14 days of ODM-conditioned culture by following the manufacturer’s protocols for QIA-Shredder and RNeasy micro-kits (QIAgen). Subsequently, the reverse transcription of RNA into cDNA was performed with an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad Laboratories). Real time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was run using SsoAdvanced SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) in a RT-qPCR detection apparatus (Bio-Rad). The fold changes of target gene expressions were calculated using the comparative CT method, i.e., 2−ΔΔCt method. All the primer sequences used in this study are shown in Supplementary Table s1.

RNA sequencing:

Total RNA was extracted from yPPVIC and aPPVIC laden PLGA-PASP-H constructs after 14-day culture in GM (denoted as yScaffold and aScaffold, respectively) using RNeasy mini-kits (QIAGEN), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Freshly isolated yPPVICs and aPPVICs from three pigs from each age group were pooled together and then used for RNA isolation without any 2D culture to be used as the control (denoted as yFresh and aFresh, respectively). All of the RNA samples had a 260/280 ratio >2.0 and an RNA Integrity Number > 9.0, verified by an RNA Bioanalyzer. Libraries for RNA sequencing were prepared using a TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina), and sequencing was performed on a Sciclone G3 NGS Workstation.

RNA seq data analysis:

The original FASTQ format reads were merged and trimmed by the fqtrim tool (https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/fqtrim) to remove adapters, terminal unknown bases (Ns), and low quality 3’ regions (Phred score < 30). The trimmed FASTQ files were processed by FastQC (Andrews S. (2010). FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data; available online at http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc) for quality control. The trimmed FASTQ files were mapped by STAR, as the aligner, and RSEM, as the tool for annotation and quantification, at both gene and isoform levels. The normalized expression values in TPM (Transcripts Per Kilobase Million) at gene levels were subject to statistical comparisons. The Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) method 50 was also used to adjust p values for multiple-testing caused false discovery rate. The adjusted p ≤ 0.05 was considered as significant. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was done using clusterProfiler4.0.

Statistical analysis:

All the quantitative data were reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). All the experiments in this study were carried out for at least 3 replicates for every group. ANOVA with Scheffé post-hoc test and unpaired t-test were utilized to perform the comparisons for multiple groups and two groups, respectively. A p<0.05 was recognized to have a statistically significant difference.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (17SDG33680170 to B.D.), University of Nebraska Collaboration Initiative Grant (B.D. and J.Y.L.), and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) Nebraska Center for the Prevention of Obesity Diseases (NPOD) (P20GM104320, PI: Zempleni to J.Y.L.). The Bioinformatics and Systems Biology Core at UNMC receives partial support from the Nebraska Research Initiative (NRI) and NIH (5P20GM103427; 5P30CA036727) for the bioinformatics analysis performed in this study. The University of Nebraska DNA Sequencing Core receives partial support from the National Institute for General Medical Science (NIGMS) INBRE-P20GM103427-14 and COBRE-1P30GM110768-01 grants as well as The Fred& Pamela Buffett Cancer Center Support Grant - P30CA036727. The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Shaohua Wu, College of Textiles & Clothing, Qingdao University, Qingdao, 266071, China; Mary & Dick Holland Regenerative Medicine Program and Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, 68198, USA.

Yiran Li, College of Textiles & Clothing, Qingdao University, Qingdao, 266071, China.

Caidan Zhang, Key Laboratory of Yarn Materials Forming and Composite Processing Technology of Zhejiang Province, Jiaxing University, Jiaxing, 314001, China.

Litao Tao, Department of Biomedical Science, Creighton University, Omaha, NE, 68178, USA.

Mitchell Kuss, Mary & Dick Holland Regenerative Medicine Program and Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, 68198, USA.

Jung Yul Lim, Department of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, 68588, USA.

Jonathan Butcher, Meinig School of Biomedical Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, 14850, USA.

Bin Duan, Mary & Dick Holland Regenerative Medicine Program and Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, 68198, USA; Department of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, 68588, USA; Department of Surgery, College of Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, 68198, USA.

References

- [1].Kodigepalli KM, Thatcher K, West T, Howsmon DP, Schoen FJ, Sacks MS, Breuer CK, Lincoln J, J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis 2020, 7, 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].O’Donnell A, Yutzey KE, Development 2020, 147, dev183020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Saidy NT, Wolf F, Bas O, Keijdener H, Hutmacher DW, Mela P, De-Juan-Pardo EM, Small 2019, 15, 1900873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Oveissi F, Naficy S, Lee A, Winlaw DS, Dehghani F, Mater. Today Bio 2020, 5, 100038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mirani B, Parvin Nejad S, Simmons CA, Can. J. Cardiol 2021, 37, 1064–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bozso SJ, El-Andari R, Al-Adra D, Moon MC, Freed DH, Nagendran J, Nagendran J, Scand. J. Immunol 2021, 93, e13018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nazir R, Bruyneel A, Carr C, Czernuszka J, J. Func. Biomater 2021, 12, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fioretta ES, Motta SE, Lintas V, Loerakker S, Parker KK, Baaijens FPT, Falk V, Hoerstrup SP, Emmert MY, Nat. Rev. Cardiol 2021, 18, 92–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jana S, Lerman A, Acta Biomater. 2019, 85, 142–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jana S, Lerman A, Regen. Med 2020, 15, 1177–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Motta SE, Lintas V, Fioretta ES, Hoerstrup SP, Emmert MY, Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2018, 15, 35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Liu Y, Ai X, Gong Y, Tang Z, Fu W, Wang W, Mater. Express 2020, 10, 2025–2031. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chester AH, Grande-Allen KJ, Front. Cardiovasc. Med 2020, 7, 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Xue Y, Ravishankar P, Zeballos MA, San V, Balachandran K, Sant S, Polym. Adv. Technol 2020, 31, 94–106. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nachlas ALY, Li S, Davis ME, Adv. Healthc. Mater 2017, 6, 1700918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhang J, Xiao C, Zhang X, Lin Y, Yang H, Zhang YS, Ding J, Control J. Release 2021, 335, 359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lobo AO, Afewerki S, de Paula MMM, Ghannadian P, Marciano FR, Zhang YS, Webster TJ, Khademhosseini A, Int. J. Nanomedicine 2018, 13, 7891–7903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zhang J, Zheng T, Alarçin E, Byambaa B, Guan X, Ding J, Zhang YS, Li Z, Small 2017, 13, 1701949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hinton RB, Yutzey KE, Annu. Rev. Physiol 2011, 29–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Liu AC, Joag VR, Gotlieb AI, Am. J. Pathol 2007, 171, 1407–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wang X, Ali MS, Lacerda CMR, Bioengineering-Basel 2018, 5, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ma H, Killaars AR, DelRio FW, Yang C, Anseth KS, Biomaterials, 2017, 131, 131–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Schoen FJ, Circulation, 2008, 118, 1864–1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Massy ZA, Mozar A, Mentaverri R, Brazier M, Kamel S, Sang Thromb. Vaiss 2008, 20, 507–510. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hjortnaes J, New SEP, Aikawa E, Trends Cardiovasc. Med 2013, 23, 71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Priya CH, Divya M, Ramachandran B, Mater. Today Proc 2020, 33, 4467–4478. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Badria AF, Koutsoukos PG, Mavrilas D, J. Mater. Sci.-Mater. Med 2020, 31, 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Guo R, Zhou Y, Liu S, Li C, Lu C, Yang G, Nie J, Wang F, Dong N-G, Shi J, ACS Appl. Bio Mater 2021, 4, 2534–2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Myasoedova VA, Di Minno A, Songia P, Massaiu I, Alfieri V, Valerio V, Moschetta D, Andreini D, Alamanni F, Pepi M, Trabattoni D, Poggio P, Ageing Res. Rev 2020, 61, 101077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Voisine M, Hervault M, Shen M, Boilard A-J, Filion B, Rosa M, Bosse Y, Mathieu P, Cote N, Clavel M-A, Am J. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e015610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Voniatis C, Barczikai D, Gyulai G, Jedlovszky-Hajdu A, J. Mol. Liq 2021, 323, 115094. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Molnar K, Voniatis C, Feher D, Ferencz A, Weber G, Zrinyi M, Jedlovszky-Hajdu A, Biophys. J 2018, 114, 363A–363A. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Pawar NM, Rao P, Cell. Signal 2018, 45, 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Nordquist E, LaHaye S, Nagel C, Lincoln J, Front. Cardiovasc. Med 2018, 5, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].She Q, Wang D, Liu B, Xiong T, Yu W, Wang J, Xiao K, Front. Genet 2021, 12, 445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Mehana E-SE, Khafaga AF, El-Blehi SS, Life Sci. 2019, 234, 116786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Fondard O, Detaint D, Iung B, Choqueux C, Adle-Biassette H, Jarraya M, Hvass U, Couetil J-P, Henin D, Michel J-B, Eur. Heart J 2005, 26, 1333–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Fong F, Xian J, Demer LL, Tintut Y, J. Cell. Biochem 2021, 122, 249–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Massadeh S, Alhashem A, van de Laar IMBH, Alhabshan F, Ordonez N, Alawbathani S, Khan S, Kabbani MS, Chaikhouni F, Sheereen A, Almohammed I, Alghamdi B, Frohn-Mulder I, Ahmad S, Beetz C, Bauer P, Wessels MW, Alaamery M, Bertoli-Avella AM, Clin. Genet 2020, 98, 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wuennemann F, Ta-Shma A, Preuss C, Leclerc S, van Vliet PP, Oneglia A, Thibeault M, Nordquist E, Lincoln J, Scharfenberg F, Becker-Pauly C, Hofmann P, Hoff K, Audain E, Kramer H-H, Makalowski W, Nir A, Gerety SS, Hurles M, Comes J, Fournier A, Osinska H, Robins J, Puceat M, Elpeleg O, Hitz M-P, Andelfinger G, Dietz HC, McCallion AS, Loeys BL, Van Laer L, Eriksson P, Mohamed SA, Mertens L, Franco-Cereceda A, Mital S, Principal MLC, Nature Genet. 2020, 52, 40–+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Clark-Greuel JN, Connolly JM, Sorichillo E, Narula NR, Rapoport HS, Mohler III ER, Gorman III JH, Gorman RC, Levy RJ, Ann. Thorac. Surg 2007, 83, 946–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Cushing MC, Mariner PD, Liao JT, Sims EA, Anseth KS, FASEB J. 2008, 22, 1769–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Farrar EJ, Huntley GD, Butcher J, PLoS One 2015, 10, e0123257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Zhu AS, Mustafa T, Connell JP, Grande-Allen KJ, Acta Biomater. 2021, 127, 159–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].O’Donnell A, Yutzey KE, Development 2020, 147, dev183020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kodigepalli KM, Thatcher K, West T, Howsmon DP, Schoen FJ, Sacks MS, Breuer CK, Lincoln J, J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis 2020, 7, 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Jana S, Lerman A, Cell Tissue Res. 2020, 382, 321–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Saidy NT, Wolf F, Bas O, Keijdener H, Hutmacher DW, Mela P, De‐Juan‐Pardo EM, Small 2019, 15, 1900873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Wang X, Ali MS, Lacerda CM, Bioengineering, 2018, 5, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Priya CH, Divya M, Ramachandran B, Mater. Today Proc 2020, 33, 4467–4478. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Adelnia H, Tran HD, Little PJ, Blakey I, Ta HT, ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2021, 7, 2083–2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Pavlyuk A, Kamalov M, Nemtarev A, Abdullin T, Salakhieva D, BioNanoScience 2020, 10, 625–632. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Pourentezari M, Dortaj H, Hashemibeni B, Yadegari M, Shahedi A, Int. J. Med. Sci. Lab 2021, 8, 78–95. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Li P, Wang Y, Jin X, Dou J, Han X, Wan X, Yuan J, Shen J, J. Mat. Chem. B 2020, 8, 6092–6099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Hajiabbas M, Alemzadeh I, Vossoughi M, Polym. Adv. Technol 2021, 32, 1333–1344. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Duan B, Ann. Biomed. Eng 2017, 45, 195–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Masoumi N, Annabi N, Assmann A, Larson BL, Hjortnaes J, Alemdar N, Kharaziha M, Manning KB, Mayer JE Jr, Khademhosseini A, Biomaterials 2014, 5, 7774–7785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hasan A, Ragaert K, Swieszkowski W, Selimović Š, Paul A, Camci-Unal G, Mofrad MR, Khademhosseini A, J. Biomech 2014, 47, 1949–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Wu S, Kumar V, Xiao P, Kuss M, Lim JY, Guda C, Butcher J, Duan B, Sci Rep 2020, 10, 21338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Santoro R, Scaini D, Severino LU, Amadeo F, Ferrari S, Bernava G, Garoffolo G, Agrifoglio M, Casalis L, Pesce M, Biomaterials 2018, 181, 268–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Duan B, Yin Z, Kang LH, Magin RL, Butcher JT, Acta Biomater. 2016, 36, 42–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Puperi DS, Kishan A, Punske ZE, Wu Y, Cosgriff-Hernandez E, West JL, Grande-Allen KJ, ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2016, 2, 1546–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Nachlas AL, Li S, Davis ME, Adv. Healthc. Mater 2017, 6, 1700918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Du J, Zhu T, Yu H, Zhu J, Sun C, Wang J, Chen S, Wang J, Guo X, Appl. Surf. Sci 2018, 447, 269–278. [Google Scholar]

- [65].Kristen M, Ainsworth MJ, Chirico N, van der Ven CF, Doevendans PA, Sluijter JP, Malda J, van Mil A, Castilho M, Adv. Healthc. Mater 2020, 9, 1900775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Kluin J, Talacua H, Smits AI, Emmert MY, Brugmans MC, Fioretta ES, Dijkman PE, Söntjens SH, Duijvelshoff R, Dekker S, Biomaterials 2017, 125, 101–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Azari S, Rezapour A, Omidi N, Alipour V, Tajdini M, Sadeghian S, Bragazzi NL, Heart Fail. Rev 2020, 25, 495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Wu S, Kumar V, Xiao P, Kuss M, Lim JY, Guda C, Butcher J, Duan B, Sci Rep 2020, 10, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Wang H, Tibbitt MW, Langer SJ, Leinwand LA, Anseth KS, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2013, 110, 19336–19341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Zhang C, Wu S, Qin X, Mater. Lett 2014, 132, 393–396. [Google Scholar]

- [71].Zhang C, Wan LY, Wu S, Wu D, Qin X, Ko F, Dyes Pigment. 2015, 123, 380–385. [Google Scholar]

- [72].Duan B, Kapetanovic E, Hockaday LA, Butcher JT, Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 1836–1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Wu S, Duan B, Qin X, Butcher JT, Acta Biomater. 2017, 51, 89–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Duan B, Hockaday LA, Kapetanovic E, Kang KH, Butcher JT, Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 7640–7650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Wu S, Qi Y, Shi W, Kuss M, Chen S, Duan B, Acta Biomater. 2020, DOI: 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Wu S, Liu J, Qi Y, Cai J, Zhao J, Duan B, Chen S, Mater. Sci. Eng. C-Mater. Biol. Appl 2021, 126, 112181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Wu S, Zhou R, Zhou F, Streubel PN, Chen S, Duan B, Mater. Sci. Eng. C-Mater. Biol. Appl 2020, 106, 110268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Wu S, Duan B, Liu P, Zhang C, Qin X, Butcher JT, Fabrication of aligned nanofiber polymer yarn networks for anisotropic soft tissue scaffolds, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 16950–16960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.