Abstract

Morphological revision and phylogenetic analysis based on nITS and nLSU of specimens previously considered to be a species related to Fulvifomes robiniae from South America revealed a new species of Fulvifomes, i.e. Fulvifomes wrightii. It grows on Libidibia paraguariensis, a Fabaceae distributed in the Chaco Region. The new species is characterised by a perennial, ungulate basidioma with a rimose pileal surface, 6–7 pores per mm, a homogenous context, indistinct stratified tubes and abundant crystals in tube trama and hymenia. Illustrations, taxonomic analyses and a key to the Fulvifomes species recorded from the Americas is provided.

Citation: Martínez M, Salvador-Montoya CA, de Errasti A, Popoff OF, Rajchenberg M (2023). Fulvifomes wrightii (Hymenochaetales), a new species related to F. robiniae from Argentina and Paraguay. Fungal Systematics and Evolution 12: 47–57. doi: 10.3114/fuse.2023.12.03

Keywords: distribution, host, Hymenochaetaceae, new taxa, phylogenetic analysis, taxonomy

INTRODUCTION

Fulvifomes (Murrill 1914) is characterised by perennial basidiomata with or without a crust on the pileal surface, a monomitic to dimitic hyphal system, with or without dark lines in the context, and subglobose to ellipsoid, yellowish basidiospores, occasionally with a flattened side that turn darker in KOH solution (Zhou 2014, Salvador-Montoya et al. 2018, 2022). For many decades the genus was considered a synonym of Phellinus (Phellinus s.l.) or a subgenus of Phellinus (Dai 1999). However, molecular studies confirmed that Fulvifomes is a distinct taxon (Wagner & Fisher 2001, 2002). Wagner & Fischer (2002), Larsson et al. (2006) and Dai (2010) showed that Fulvifomes is closely related to Aurificaria luteoumbrina in their phylogenetic inferences. Currently, Aurificaria is considered a synonym of Fulvifomes (Zhou 2014). Ecologically, Fulvifomes includes species that grow on dead trunks and living angiosperm trees in temperate and tropical regions (Salvador-Montoya et al. 2018, Olou et al. 2019, Wu et al. 2022).

Fulvifomes robiniae (type species of the genus) is considered a parasitic polypore of Robinia species (recurrent host is R. pseudoacacia) in temperate North America (Salvador-Montoya et al. 2018). This species was related to Fulvifomes rimosus (Kotlaba & Pouzar 1978). However, Kotlaba & Pouzar (1978, 1979) showed F. robiniae and F. rimosus to exhibit morphological differences in the shape of pileal and pore surfaces, as well as in the size of basidiospores. Furthermore, F. robiniae was initially considered to have a variable morphology and wide geographic distribution in North and Central America (USA, Bahamas, Puerto Rico and Jamaica) (Kotlaba & Pouzar 1978, 1979, Gilbertson & Ryvarden 1987). Nevertheless, based on morphological, ecological and molecular data, Salvador-Montoya et al. (2018, 2022) have shown that specimens resembling F. robiniae from different parts of the Americas correspond to different entities.

During surveys in Paraguay and Argentina, specimens that resemble F. robiniae were collected in the Chaco Region of both countries. The aim of the present study was to taxonomically establish and describe a new species within the F. robiniae complex in the Chaco region in South America.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Morphological studies

The specimens studied are deposited in the Fungarium of the Centro de Investigación y Extensión Forestal Andino Patagónico (HCFC) and Fungarium CTES. Morphological and microscopic procedures follow Robledo & Urcelay (2009). Colours were determined following Kornerup & Wanscher (1978). Spores were measured from sections from the tubes of basidiomata. For the spore measurements ImageJ software was used (González 2018). The following abbreviations were used: KOH = 5 % potassium hydroxide, IKI = Melzer’s reagent, IKI– = neither amyloid nor dextrinoid, CB = cyanophilous, CB– = acyanophilous, L = mean spore length (arithmetic mean of all spores), W = mean spore width (arithmetic average of all spores), Q = variation in L/W ratios among specimens studied, n = number of spores measured from a given number of specimens. The maps were prepared with QGIS 3.12 “Bucuresti” free software (https://www.qgis.org/en/site/).

Isolates

A fungal culture was obtained from the basidiomata by transferring small pieces from the context or tubes to Petri dishes containing 2 % malt extract agar (MEA) (Nobles 1965, Rajchenberg & Greslebin 1995) and deposited in the Culture Collection of Centro de Investigación y Extensión Forestal Andino Patagónico (CIEFAPcc).

DNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing

Extraction of total genomic DNA from dried basidiomata and culture followed the protocol of Doyle & Doyle (1990) modified by Tamari & Hinkley (2016). Primers pairs LR0R, LR5 and LR7 (Vilgalys & Hester 1990) were used to amplify nLSU sequences, while the ITS region was amplified using primers ITS1 and ITS4 (White et al. 1990). The PCR procedure for ITS and LSU followed Ji et al. (2017). For ITS the amplification was: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94 °C for 40 s, 54 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 1 min, and a final extension of 72 °C for 10 min. For nLSU the amplification was: denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 1.5 min, with a final extension of 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR product was purified and sequenced in Macrogen Inc. (Republic of Korea).

Phylogenetic analyses

The new sequences obtained from each region were assembled and manually edited using the Bioedit program, Geneious v. 6.1.8 and CromasPro DNA Sequencing Software (Hall 1999, Treves 2010, Kearse et al. 2012). New nITS and nLSU sequences were added to sequences obtained from GenBank (NCBI) (Table 1). The sequences used in this work represent species endorsed by Ji et al. (2017), Salvador-Montoya et al. (2018, 2022) and Olou et al. (2019).

Table 1.

List of species, localities, sources and GenBank accession numbers of taxa used in this study.

| Species | Geographic Origin | Collection Reference | Substrate | GenBank accession number | |

| Species | Geographic Origin | Collection Reference | Substrate | GenBank accession number | |

| Fulvifomes azonatus | China/Yunnan | Dai 17470 | Angiosperm | MH390395 | MH390418 |

| F. acaciae | Costa Rica | JV 2203/71-J | Acacia sp. | OP828596 | OP828594 |

| USA | JV 0312/23.4 | Acacia sp. | OP828597 | OP828595 | |

| F. boninensis | Japón | FFPRI421009 | Morus boninensis | LC315777 | LC315786 |

| F. caligoporus | China/Hainan | Dai 17660 | On living angiosperm tree | MH390391 | MH390421 |

| F. cedrelae (as F. centroamericanus) | Guatemala | JV 0611/III | On living angiosperm tree | KX960764 | KX960763 |

| Guatemala | JV 0611/8P | On living angiosperm tree | – | KX960757 | |

| Costa Rica | JV 1408/4 | On living angiosperm tree | KX960768 | – | |

| F. costaricense | Costa Rica/Guanacaste | JV 1607/103-J | Angiosperm | MH390386 | MH390414 |

| F. dracaenicola | China/Hainan | Dai 22093 | Dracaena cambodiana | MW559804 | MW559799 |

| F. elaeodendri | South Africa | CMW 47909 | Elaeodendron croceum | MH599132 | MH599096 |

| F. fastuosus | Philippines | CBS 213.36 | Gliricidia sepium | AY059057 | AY558615 |

| Thailand | LWZ 20140801-1 | Angiosperm | KR905669 | KR905675 | |

| F. floridanus | USA/Florida | JV 0904/76 | Lysiloma latisiliqua | MH390388 | MH390424 |

| F. fabaceicola | Brazil/Pernambuco | JRF 74 | – | MH048087 | MH048097 |

| Brazil/Pernambuco | PH 6 | – | MH048086 | MH048096 | |

| F. fastuosus | Philippines | CBS 213.36 | Gliricidia sepium | AY059057 | AY558615 |

| F. hainanensis | China | Dai 11573 | Angiosperm | JX866779 | KC879263 |

| F. halophilus | Thailand | MU23 | Xylocarpus granatum | JX104740 | JX104693 |

| F. imbricatus | Thailand | LWZ 20140729-26 | Angiosperm | KR905671 | KR905679 |

| F. indicus | China | Yuan 5932 | Bombax ceiba | JX866777 | KC879261 |

| Zimbabwe | O 25034 | Unknown | KC879259 | KC879262 | |

| F. jouzaii | Costa Rica/Puntarenas | JV 1504/16-J | Angiosperm | MH390400 | MH390425 |

| F. jawadhuvensis | India | MUBL4011 | Albizia amara | MW048886 | MW040079 |

| F. coffeatoporus | USA/Florida | JV0904/1 | Krugiodendron ferreum | KX960765 | KX960762 |

| USA/Florida | JV0312/24.10J | K. ferreum | KX960766 | KX960760 | |

| USA/Florida | JV1008/21 | K. ferreum | KX960767 | KX960761 | |

| F. karitianaensis | Brazil/Rondonia | AMO 763 | – | MH048081 | MH048091 |

| F. kawakamii | USA | CBS 428.86 | Casuarina equisetifolia | AY059028 | – |

| F. merrillii | Taiwan | – | Unknown | JX484002 | JX484013 |

| F. mangroviensis | India | MUBL4012 | Aegiceras corniculatum | MW048909, | MW040083 |

| India | KSM-MP12a | A. corniculatum | OM897221 | OM897222 | |

| F. malaiyanurensis | India | CAL 1618 | Tamarindus indica | MW048883 | MF155651 |

| F. nakasoneae | JV 0904/68 | USA/Florida | Angiosperm | MH390373 | MH390408 |

| JV 1109/77 | USA/Texas | Condalia hookeri | MH390374 | MH390409 | |

| F. nilgheriensis | USA | CBS 209.36 | On dead deciduous wood | AY059023 | AY558633 |

| F. nonggangensis | China/Guangxi | GXU 1127 | Angiosperm | MT571502 | MT571504 |

| F. popoffii | Argentina/Corrientes | CTES 568185 | Peltophorum dubium | ON754378 | ON754383 |

| Argentina/Corrientes | CTES 568187 | P. dubium | ON754377 | – | |

| Argentina/Corrientes | CTES 568190 | Schinopsis balansae | ON754379 | ON754384 | |

| Argentina/Corrientes | CTES 568186 | P. dubium | ON754376 | ON754382 | |

| F. rhytiphloeus | Brazil/Bahia | VRTOR658 | – | MT906624 | MT908357 |

| F. rigidus | China/Yunnan | Dai 17496 | Shorea chinensis | MH390398 | MH390432 |

| F. rimosus | Taiwan | – | Unknown | JX484003 | JX484016 |

| Australia | 2392655 | Unknown | – | MH628255 | |

| F. robiniae | USA/Maryland | CBS 211.36 | Robinia pseudoacacia | AY059038 | AY558646 |

| USA/Arizona | CFMR 2693 | R. neomexicana | KX065995 | KX065961 | |

| USA/Wisconsin | CFMR 2735 | R. pseudoacacia | KX065996 | KX065962 | |

| F. siamensis | Thailand | STRXG2 | Xylocarpus granatum | JX104755 | JX104708 |

| F. squamosus | Peru/Piura | USM 258349 | Acacia macracantha | MF479264 | MF479269 |

| Peru/Piura | USM 258361 | A. macracantha | MF479266 | MF479267 | |

| F. subindicus | China/Hainan | Dai 17743 | Angiosperm | MH390393 | MH390435 |

| F. submerrillii | China/Hubei | Dai 17911 | On angiosperm stump | MH390371 | MH390405 |

| Fulvifomes sp. | Australia | MEL 2382673 | Unknown | KP013036 | KP013036 |

| F. thailandicus | Thailand | LWZ 20140731-1 | Angiosperm | KR905665 | KR905672 |

| F. tubogeneratus | China/Guangxi | GXU 2468 | On dead trunk | MT580800 | MT580805 |

| F.thiruvannamalaiensis | India | MUBL4013 | Albizia amara | MZ221600 | MZ221598 |

| F. xylocarpicola | Thailand | KBXG5 | Xylocarpus granatum | JX104716 | JX104669 |

| Thailand | MU1 | X. granatum | JX104718 | JX104671 | |

| F. yoroui | Benin/Collines | OAB 0097 | Pseudocedrela kotschyi | MN017120 | MN017126 |

| F. wrightii | Paraguay/Pte.Hayes | HCFC 3237 | Libidibia paraguariensis | OQ924554 | OQ807188 |

| Paraguay/Pte.Hayes | HCFC 3238 | L. paraguariensis | OQ924556 | OQ807189 | |

| Paraguay/Boquerón | HCFC 3239 | L. paraguariensis | OQ924555 | – | |

| Argentina/Chaco | CTES 568247 | L. paraguariensis | OQ924562 | OQ807190 | |

| Argentina/Chaco | CTES 568252 | L. paraguariensis | OQ924561 | OQ807191 | |

| Argentina/Chaco | CTES 568254 | L. paraguariensis | OQ924557 | OQ807195 | |

| Argentina/Chaco | CTES 568251 | L. paraguariensis | OQ924560 | OQ807192 | |

| Argentina/Chaco | CTES 568249 | L. paraguariensis | OQ924559 | OQ807193 | |

| Argentina/Chaco | CTES 568253 | L. paraguariensis | OQ924558 | OQ807194 | |

| F. waimiriatroarensis | Brazil/Amazonas | VTROAMZ01 | Unknown | OK086356 | OK086370 |

| Fomitiporia chinensis | China | LWZ 20130713-7 | Deciduous wood | KJ787808 | KJ787817 |

| F. chinensis | China | LWZ 20130916-3 | Deciduous wood | KJ787809 | KJ787818 |

| Inonotus hispidus | Spain | S45 | Vitis vinifera | EU282484 | EU282482 |

| I. porrectus | USA/Missouri | CBS 296.56 | Gleditschia triacanthos | AY059051 | AY558603 |

| Inocutis dryophilus | USA/Ohio | L(61)5-20-A | Quercus prinus | AM269846 | AM269783 |

| I. jamaicensis | USA/Arizona | RLG 15819 | Q. arizonica | KY907703 | – |

| Phellinotus neoaridus | Brazil/Pernambuco | URM 80362 | Caesalpiania sp. | KM211286 | KM211294 |

The dataset was aligned with Guidance (Sela et al. 2015), under L-INS-I criteria for nLSU region and Q-INS-I for ITS, then manually inspected and edited using the MEGA v. 6 program (Tamura et al. 2013) when needed. Potential ambiguously aligned segments were detected with the software Gblock v. 0.91b (Castresana 2000) for the nITS region. The combined dataset was constructed combining the nLSU and nITS regions and was subdivided into four data partitions: ITS1, 5.8S, ITS2 and LSU. Phellinotus neoaridus, Fomitiporella chinensis, Inocutis dryophilus and Inonotus hispidus were used as outgroups for phylogenetic inferences, based on works performed by Salvador-Montoya et al. (2018), Pildain et al. (2018) and Olou et al. (2019).

The best evolutionary model was selected with AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) with the jModelTest2 v. 1.6 on XEDE program in CIPRESS online (Darriba et al. 2012). Maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) were employed to perform phylogenetic analysis of the final combined dataset. Maximum likelihood was conducted with RaxMLv. 8.1 program (Stamatakis 2014) to find the best score trees with GTRGAMMA model for the single marker and the data set. The analysis first involved 1 000 independent ML searches each one starting from one randomised stepwise addition parsimony tree. The BI analysis was carried out in the Mr.Bayes v. 3.2.6 program (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck 2003) with two independent runs, each one starting from random trees with four independent simultaneous chains. A total of 8 000 000 million generations were made in total, sampling a tree every 1000 generations. The final alignment were deposited in TreeBASE (http://purl.org/phylo/treebase/phylows/study/TB2:S30336).

RESULTS

Molecular phylogeny

The final combined database (28S + ITS1 + 5.8S + ITS2), had 68 sequences (including the new sequences), resulting in a total of 1 995 characters of which 628 were constant. The Jmodeltest results indicated that the best evolutionary model for each partition was TIM2+I+G, TrN+G, K80+I and TIM3+G for LSU, ITS1, 5.8S, ITS2, respectively.

The phylogenetic inferences based on the combined dataset showed that Fulvifomes was recovered as monophyletic (BS = 100/BPP = 1). Within Fulvifomes, the sequences of the new species formed a monophyletic group (BS = -/BPP = 0.87) closely related to F. robiniae (BS = 100/BPP = 1), but forming a distinct linage here named as Fulvifomes wrightii (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Maximun likelihood (ML) tree of Fulvifomes based on dataset of ITS and nLSU sequences. Bayesian posterior probability above 0.80 and bootstrap values above 60 % are shown. Species studied in this work are in bold and the different substrates on which the species in the genus grow (! = type material; ◆ = angiosperm; ▲ = dead angiosperm; ◄ = living angiosperm; *= decaying wood; ● =dead deciduous wood; ∎ dead trunk; ∆ = unknown).

Taxonomy

Fulvifomes wrightii M. Martínez, Salvador-Montoya & Rajchenb., sp. nov. MycoBank MB 848322. Figs 2, 3.

Fig. 2.

Fulvifomes wrightii sp. nov. A–I. Basidiomata: A. CTES 568247; B. CTES 568248; C. CTES 568252; D. CTES 568250; E. CTES 568251; F. CTES 568249; G. CTES 568254; H. CTES 568253; I. HCFC 3238; J. HCFC 3237 (holotype). K, L. Pore surface. M–O. Basidiospores: M. In water; N. In Melzer’s reagent; O. In 5 % KOH. Scale bars: A–D = 2cm; E, F = 1 cm; G = 5 cm; H = 2 cm; I = 5 cm; J = 1cm; K, L = 3 cm; M–O = 5 µm.

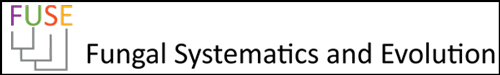

Fig. 3.

Microscopical features of Fulvifomes wrightii. A. Thin- to thick-walled generative hyphae of the context. B. Skeletal hyphae from the tubes. C. Crystals. D. Basidiospores. Scale bars: A = 100 µm; B = 100 µm; C = 15 µm; D = 10 µm.

Typus: Paraguay, Pte. Hayes, Chaco Húmedo, residence “Frigorífico Concepción SA”. Coord.: 23°26’39’’ S57°27’54’’W, on living stems of Libidibia paraguariensis, 18 May 2019, M. Martínez, M. Vera & C. Insfrán, N° 415A, CIEFAPcc 707 (holotype HCFC 3237).

Diagnosis: Basidioma perennial, ungulate, pileal surface rimose, dark gray, pore surface flat to convex, 6–7 pores/mm. Context homogenous. Hyphal system monomitic in the context and dimitic in tube trama. Hymenia with abundant crystals. Basidiospores subglobose to broadly ellipsoidal with a flattened side, (4.5–)5–6 × (4–)4.5–5 µm, thick-walled, yellow to brown in water, turning darker in KOH solution, on living trees of Libidibia paraguariensis.

Etymology: In honour of Dr. Jorge Eduardo Wright for his contributions to Paraguayan mycology.

Description: Basidiomata perennial, sessile, solitary, woody hard. Pilei dimidiate, ungulate to slightly applanate, projecting up to 100–143 mm long, 48–81 mm wide and 30–145 mm thick at the base. Pileal surface with brown tomentose zones (5E6 – 5F7), soon glabrous and black, dark grey (1F1) to greyish green (1C2 – 1D2), in juvenile specimens concentrically furrowed with small cracks, in the mature basidioma the pileal surface becoming radially to concentrically rimose, glabrous, margin slightly acute to obtuse, entire, brown reddish (6C7) to dark brown (6FA). Hymenophore poroid, flat to convex, brown (5E7 – 5E4), dark brown (6F8) to greyish brown (5E3); pores round to regular (5)6–7(8) per mm, (90–)100–190(–200) µm diam, dissepiments entire, (30–)40–170(–190) µm thick. Tubes indistinctly stratified, with whitish mycelial cords filling the more developed tubes, up to 105 mm long, brown (6E7). Context homogenous, golden brown (5D7), woody hard, up to 5–8 mm in juvenile specimen, almost lacking when mature. In KOH the context becomes reddish brown and, the tubes, dark brown.

Hyphal system monomitic in the context and dimitic in tube trama; generative hyphae thin- to thick-walled, branched, regularly simple-septate, (1.5–)2.5–4.5(−6) µm diam; trama with unbranched skeletal hyphae, 90–526 × (3–)3.5–4 um, lumen almost solid, tapering to the apex with 2–4 adventitious septa. Generative hyphae thin- to thick-walled, covered with small crystals, 1.5–4 µm diam, branched and simple septate. Basidiospores (4.5–)5–6 × (4–)4.5–5 µm, (L = 5.4 µm, W = 4.6 µm) Q = 1.10–1.25 (Q av. = 1.18), broadly ellipsoid to subglobose, with a flattened side, smooth and thick-walled, yellow to brown in water, dark brown in KOH, IKI‒, CB‒. Rhomboid and quadrangular crystals present in hymenia. Basidia and cystidia not observed.

Cultural characters: Growth slow, 0.5–3.5 cm in MEA in 25 d, at first mat somewhat compacted, then cottony, especially the central area, to somewhat homogeneously appressed, scant fluffy aerial mycelium to somewhat cottony present, pale yellow at first, then becoming deep yellow, margin irregular. Aerial hyphae composed of dominant generative hyphae, 1–4 µm diam, frequently branched, thickened in some sections and with some cytoplasmic contents, regularly septate. Fibre hyphae present, not dominant, little branched, 2.5–3.5 µm diam, lumen almost solid. Chlamydospores abundant, globose, ellipsoid, terminal and intercalated 3.7–11.9 × 4.7– 9.9 µm. The hyphae are pale yellow in water, turning reddish on contact with KOH (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Fulvifomes wrightii. Macro- and microscopic cultural features. A. Mycelial mat, B, C. Generative hyphae, in water. D–F. Ellipsoid and globose chlamydospores, in KOH. G. Fiber hyphae, in KOH. Scale bars: A = 2 cm; B, C = 5 µm; D–F = 15 µm; G = 5 µm.

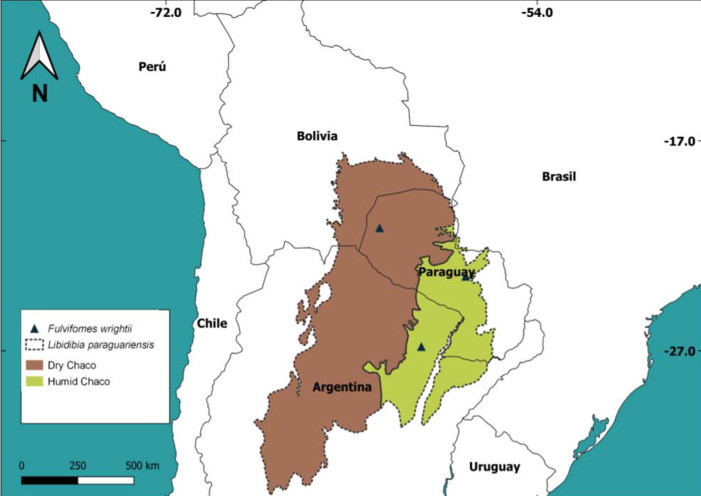

Habitat and Distribution: Basidiomata are found on living trees of L. paraguariensis (Fabaceae). This polypore is distributed in the Chaco region of Paraguay and Argentina (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Map of the geographic distribution of specimens of Fulvifomes wrightii and the host Libidibia paraguariensis in subtropical region (the black lines represent the estimated distribution of the host).

Specimens examined: Argentina, Chaco, Presidencia de la Plaza, Capitán Solari, Parque Nacional Chaco, on living tree of L. paraguariensis, 29 Mar. 1990, O.F. Popoff 693 (CTES 568261); ibid., on living tree of L. paraguariensis, 17 Sep. 2016, C.A. Salvador-Montoya et al. 715, 717 and 716 (CTES 568247, 568254 and 568252, respectively); ibid., on living tree of L. paraguariensis, 18 Sep. 2016, C.A. Salvador-Montoya & O.F. Popoff 723, 724, 725, 726 and 727 (CTES 568250, 568249, 568253, 568251, 568248, respectively); ibid., on living tree of L. paraguariensis (as Caesalpinia melanocarpa), Jun. 1947, Wright, C. Iaconis & J.A. Stevenson (BACF 53440 as Fomes dependens); ibid., Apr. 1949, Martinoli (BACF 53441, as Fomes dependens). Paraguay, Pte. Hayes, Chaco Húmedo, residence “Frigorífico Concepción SA”, 23°26’39’’S 57°27’54’’W, on living tree of L. paraguariensis, 18 May 2019, M. Martínez, M. Vera & C. Insfran 415A (HCFC 3237, holotype); ibid., 18 May 2019, M. Martínez, M. Vera & C. Insfran 415B (HCFC 3238); ibid., 16 Nov. 2018, M. Martínez, B. De Madrignac & Cristian 393 (HCFC 3239).

Additional specimens examined: Fulvifomes robiniae: EE. UU. Ohio #223 (ex NY, lectotype fide Lowe) (BACF 27561, isotype). Fulvifomes aff. robiniae: Tayikistan, Tadzhik SSR, Nurek, on living Pistacia vera, 25 Apr. 1980, E. Parmasto 102813 (BAFC 28043, as Phellinus robiniae).

DISCUSSION

Fulvifomes wrightii is characterised by its perennial ungulate basidiomata with rimose and dark grey pileal surface, a convex pore surface with 6–7 pores per mm, indistinctly stratified tubes, the homogenous context, a dimitic hyphal system that is restricted to the tubes (viz., monomitc in the context), and hymenia and tube trama with abundant crystals in well-developed specimens (Fig. 3). In vitro, the culture has chlamydospores (Fig. 4).

Fulvifomes wrightii resembles Fulvifomes robiniae by the shape of basidiomata and basidiospores. However, F. robiniae has a cracked and dark brown pileal surface, a flat pore surface with 5–6 pores per mm, and lacks crystals in the hymenium (Gilbertson & Ryvarden 1987, Salvador-Montoya et al. 2018). Additionally, F. robiniae has a geographic distribution in temperate zones of the USA, growing mainly on living trees of Robinia pseudoacacia (Kotlaba & Pouzar 1978, Salvador-Montoya et al. 2018), a Fabaceae that is native in North America (IPNI 2022). Outside the Americas, R. pseudoacacia is a naturalised and invasive species in the temperate regions of Europe, as well as in Asia and Southern Africa (Capdevila-Argüelles et al. 2011). Regarding F. wrightii, it is found in the subtropical region of South America, growing on living trees of L. paraguariensis [common name is “Guayacán”, considered the South American ebony tree according to Aronson & Toledo (1992)]. Libidibia paraguariensis is considered endemic to the Chaco region and is distributed in north and central Argentina, southern Bolivia, Brazil (specifically in Matto Grosso do Sul state), Paraguay (Giménez et al. 2017). According to Mereles (2005), L. paraguariensis appears in xerophytic forests in the Chaco region, and grows in structured, floodable and asphyxiated soils. Nevertheless, Imaña-Encinas et al. (2019) mention it as a tree species of the humid Chaco, conditioned by topographic gradients and floods.

Fulvifomes wrightii also resembles F. cedrelae, F. rimosus, F. popoffii and Phellinus chaquensis. Nevertheless, F. cedrelae differs by smaller basidiospores (5–5.5 × 4–4.5 μm) and by growing on Meliaceae where it induces a heart-rot (e.g. Cedrela fissilis, C. odorata and Swietenia mahagoni) (Salvador-Montoya et al. 2018, 2022). Regarding F. rimosus, it has larger pores (4–5 pores/mm) (Kotlaba & Pouzar 1978). In the case of F. popoffii, this species has a rimose pileal surface, a flat pore surface with 5–6 pores/mm and grows on living trees of Peltophorum dubium (Salvador-Montoya et al. 2022). Finally, P. chaquensis differs from F. wrigthii by its smaller pores (6–7 pores/mm), presence of hymenial setae and by growing on standing trees of Astronium balansae, L. paraguariensis and species of Schinopsis (Luna et al. 2012, Rajchenberg & Robledo 2013, Salvador-Montoya et al. 2018).

Key to species of Fulvifomes in America

-

1 Pileal surface rimose1 .......... 2

1 Pileal surface fissured, cracked or squamulate2 .......... 9

2 Hyphal system dimitic throughout the basidioma .......... 3

2 Hyphal system monomitic in the context and dimitic in the tubes .......... 4

3 Tubes distinctly stratified, spores cyanophilous, pores 9–10 per mm .......... F. jouzaii

3 Tubes indistinctly stratified, spores acyanophilous, pores 3–5 per mm .......... F. rimosus

4 Basidioma triquetrous, on Polygonaceae .......... F. minutiporus

4 Basidioma ungulate, another host .......... 5

5 Pores (5–)6–7(–8) per mm .......... 6

5 Pores 3–4 per mm .......... 8

6 Crystals lacking, context with indistinct dark lines .......... F. cedrelae

6 Crystals present in the hymeniun and tubes, context without black lines .......... 7

7 Growing on Peltophorum dubium and Schinopsis balansae .......... F. popoffii

7 Growing on Libidibia paraguariensis .......... F. wrigthii

8 Tubes stratified, basidiospores ellipsoid .......... F. fabaceicola

8 Tubes indistinctly stratified, basidiospores subglobose to globose .......... F. coffeatoporus

9 Tubes distinctly stratified, dimitic hyphal system throughout the basidioma .......... 10

9 Tubes indistinctly stratified, dimitic hyphal system restricted to the tubes .......... 11

10 Pores 7–9 per mm .......... F. rhytiphloeus

10 Pores 4–7 per mm .......... F. grenadensis

11 Context with black lines .......... 12

11 Context without black lines .......... 13

12 Basidiospores ellipsoid, chlamydospores present .......... F. kawakamii

12 Basidiospores subglobose, chlamydospores absent .......... F. costaricense

13 Pilear surface squamulate, on Acacia macracantha .......... F. squamosus

13 Pilear surface cracked with crusted or scrupose zone, host different .......... 14

14 Growing on Robinia pseudoacacia .......... F. robiniae

14 Growing on Acacia .......... 15

15 Basidiospores broadly ellipsoidal, 5–6 × 4–5 μm .......... F. acaciae

15 Basidiospores ellipsoid, 4–5 × 3–4 μm .......... 16

16 Pileal surface glabrous .......... F. karitianaensis

16 Pileal surface velutinate .......... F. waimiriatroariensis

1Rimose: having a surface covered with a network of cracks radial-concentrically and small crevices.

1Fissured: having long irregularly, narrow cracks or openings.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the curators of the fungaria BAFC and CTES for providing access to collections. The first author thanks Luis Oakley and Christian Vogt for helping with commentaries on Chaco’s biogeography and distribution of L. paraguariensis, Pablo Masera for helping with the geoprocessing and map confection and to Belén Pildain for her help with the phylogenetic tree. Funding by PICT-MinCyT (Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Argentina) for projects 2015/1933 and 3234/2018 are also acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- Aronson J, Toledo SC. (1992). Caesalpinia paraguariensis (Fabaceae): Forage Tree for All Seasons. Economic Botany 46: 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila-Argüelles L, Zilleti A, Suarez VA. (GEIB) (2011). Manual de las especies exóticas invasoras de los ríos y riberas de la cuenca hidrográfica del Duero. Confederación Hidrográfica del Duero Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, y Medio Rural y Marino, España. [Google Scholar]

- Castresana J. (2000). Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Molecular Biology and Evolution 17: 540–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R. et al. (2012). jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nature Methods 9: 772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai YC. (1999) Phellinus sensu lato (Aphyllophorales, Hymenochaetaceae) in East Asia. Acta Botanica Fennica 166: 43–103. [Google Scholar]

- Dai YC. (2010). Hymenochaetaceae (Basidiomycota) in China. Fungal Diversity 45: 131–343 [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. (1990). Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 12: 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbertson RL, Ryvarden L. (1987). North American Polypores vol 2. Oslo, Fungiflora. [Google Scholar]

- Giménez AM, Bolzon Muniz GBM, Moglia JGM.et al. (2017) Ecoanatomía del ébano sudamericano: “guayacán” (Libidibia paraguariensis, Fabaceae). Boletín de la Sociedad Argentina de Botánica. 52: 45–54 [Google Scholar]

- González AM.(2018). ImageJ: una herramienta indispensable para medir el mundo biológico. Folium relatos botánicos 1: 6–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hall T. (1999). BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series 4: 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Imaña-Encinas J, Campos da Nóbrega R, Jong-Choon Woo, et al. (2019). Delimitación por SIG de un área de la ecorregión Chaco Húmedo a la margen derecha del río Paraguay. Investigación Agraria 21: 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- IPNI (2022). International Plant names Index. Published on the Internet http://www.ipni.org. The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries and Australian National Botanic Gardens [Retrieved 23 August 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- Ji XH, Wu F, Dai YC. et al. (2017). Two new species of Fulvifomes (Hymenochaetales, Basidiomycota) from America. MycoKeys 22: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, et al. (2012). Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28: 1647–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornerup A, Wanscher JH. (1978). Methuen Handbook of Colour (3rd ed.). Eyre Methuen, London. [Google Scholar]

- Kotlaba F, Pouzar Z. (1978). Notes on Phellinus rimosus complex (Hymenochaetaceae). Acta Botanica Croatica 37: 171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kotlaba F, Pouzar Z. (1979). Two new setae-less Phellinus species with large coloured spores (Fungi, Hymenochaetaceae). Folia Geobotanica & Phytotaxonomica 14: 259–263. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson KH, Parmasto E, Fischer M, et al. (2006). Hymenochaetales: a molecular phylogeny of the hymenochaetoid clade. Mycologia 98: 926–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna MJ, Murace MA, Robledo GL, et al. (2012). Characterization of Schinopsis haenkeana wood decayed by Phellinus chaquensis (Basidiomycota, Hymenochaetales). IAWA Journal 33: 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Mereles F. (2005). Una aproximación al conocimiento de las formaciones vegetales del Chaco Boreal, Paraguay. Rojasiana 6: 5–48. [Google Scholar]

- Murrill WA. (1914). North American Polypores. The New Era Printing Company, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Nobles MK. (1965). Identification of cultures of wood-inhabiting Hymenomycetes. Canadian Journal of Botany 43: 1097–1139. [Google Scholar]

- Olou BA, Ordynets A, Langer E. (2019). First new species of Fulvifomes (Hymenochaetales, Basidiomycota) from tropical Africa. Mycological Progress 18: 1383–1393. [Google Scholar]

- Pildain MB, Reinoso-Cendoya R, Ortiz-Santana B, et al. (2018). A discussion on the genus Fomitiporella (Hymenochaetaceae, Hymenochaetales) and first record of F. americana from southern South America. MycoKeys 38: 77–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajchenberg M, Greslebin A. (1995). Cultural characters, compatibility tests and taxonomic remarks of selected polypores of the Patagonian Andes forest of Argentina. Mycotaxon 56: 325–346. [Google Scholar]

- Rajchenberg M, Robledo G. (2013). Pathogenic polypores in Argentina. Forest Pathology 43: 171–184. [Google Scholar]

- Robledo G, Urcelay C. (2009). Hongos de la madera en árboles nativos del Centro de la Argentina. Editorial Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. (2003). MrBayes version 3.0: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19: 1572–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvador-Montoya CA, Popoff OF, Reck MA, et al. (2018). Taxonomic delimitation of Fulvifomes robiniae (Hymenochaetales, Basidiomycota) and related species in America: F. squamosus sp. nov. Plant Systematics and Evolution 304: 445–459. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador-Montoya CA, Martínez M, Drechsler-Santos ER. (2022). Taxonomic update of species closely related to Fulvifomes robiniae in America: F. popoffii sp. nov. Mycological Progress 21: 95. [Google Scholar]

- Sela I, Ashkenazy H, Katoh K, et al. (2015). GUIDANCE2: accurate detection of unreliable alignment regions accounting for the uncertainty of multiple parameters. Nucleic Acids Research 2015 Jul. 1; 43 (Web Server issue): W7–W14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. (2014). RaxML Version 8: a tool phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30: 1312–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, et al. (2013). MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 6.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 2725–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamari F, Hinkley CS. (2016). Extraction of DNA from Plant Tissue: Review and Protocols. In: Sample Preparation Techniques for Soil, Plant, and Animal Samples, (Micic M, ed.). Humana Press, New York: 245–263. [Google Scholar]

- Treves DS. (2010). Review of three DNA analysis applications for use in the microbiology or genetics classroom. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education 11: 186–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilgalys R, Hester M. (1990). Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. Journal of Bacteriology 172: 4239–4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner T, Fischer M. (2001). Natural groups and a revised system for the European poroid Hymenochaetales (Basidiomycota) supported by nLSU rDNA sequence data. Mycological Research 105: 773–782. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner T, Fischer M. (2002). Proceedings towards a natural classification of the worldwide taxa Phellinus s.l. and Inonotus s.l., and phylogenetic relationships of allied genera. Mycologia 94: 998–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White T, Bruns T, Lee S, et al. (1990). Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: PCR Protocols: a guide to methods and applications (Innis M, Gelfand D, Sninsky J, White T, eds.) Academic Press, New York: 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Zhou LW, Vlasák J, et al. (2022). Global diversity and systematics of Hymenochaetaceae with poroid hymenophore. Fungal Diversity 113: 1–192. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou LW. (2014). Fulvifomes hainanensis sp. nov. and F. indicus comb. nov. (Hymenochaetales, Basidiomycota) evidenced by a combination of morphology and phylogeny. Mycoscience 55: 70–77. [Google Scholar]