Abstract

The presence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) covalently closed circular (ccc) DNA (cccDNA), which serves as a template for viral replication and integration of HBV DNA into the host cell genome, sustains liver pathogenesis and constitutes an intractable barrier to the eradication of chronic HBV infection. The current antiviral therapy for HBV infection, using nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs), can suppress HBV replication but cannot eliminate integrated HBV DNA and episomal cccDNA. CRISPR/Cas9 is a powerful genetic tool that can edit integrated HBV DNA and minichromosomal cccDNA for gene therapy, but its expression and delivery require a viral vector, which poses safety concerns for therapeutic applications in humans. In the present study, we used synthetic guide RNA (gRNA)/Cas9-ribonucleoprotein (RNP) as a non-viral formulation to develop a novel CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene therapy for eradicating HBV infection. We designed a series of gRNAs targeting multiple specific HBV genes and tested their antiviral efficacy and cytotoxicity in different HBV cellular models. Transfection of stably HBV-infected human hepatoma cell line HepG2.2.15 with HBV-specific gRNA/Cas9 RNPs resulted in a substantial reduction in HBV transcripts. Specifically, gRNA5 and/or gRNA9 RNPs significantly reduced HBV cccDNA, total HBV DNA, pre-genomic RNA, and HBV antigen (HBsAg, HBeAg) levels. T7 endonuclease 1 (T7E1) cleavage assay and DNA sequencing confirmed specific HBV gene cleavage and mutations at or around the gRNA target sites. Notably, this gene-editing system did not alter cellular viability or proliferation in the treated cells. Because of their rapid DNA cleavage capability, low off-target effects, low risk of insertional mutagenesis, and readiness for use in clinical application, these results suggest that synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNP-based gene-editing can be utilized as a promising therapeutic drug for eradicating chronic HBV infection.

Keywords: CRISPR/Cas9, HBV, cccDNA, synthetic therapeutic, gRNA, ribonucleoprotein

1. Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major public health problem, with 300 million people suffering from chronic hepatitis B (CHB) worldwide (WHO 2021). Approximately 1 million HBV-infected individuals die each year due to end-stage liver diseases, such as liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)1, 2. While current antiviral therapy, nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs), can suppress HBV replication, it cannot eradicate HBV infection, and NA cessation readily leads to viral reactivation and disease progression3, 4. Thus, novel therapeutic modalities are desperately needed to eliminate chronic HBV infection5–7.

Current antiviral therapies fail to cure HBV infection, primarily due to the presence of covalently closed circular (ccc) DNA (cccDNA) in the nucleus of infected cells. Distinct from integrated HBV DNA, cccDNA is an episomal minichromosome that serves as a template for transcribing viral RNAs, including pre-genomic RNA (pgRNA), which acts as a viral transcriptional template. HBV cccDNA is very stable and cannot be directly affected by antiviral NAs8. While HBV cccDNA is deemed a potential therapeutic target, there are no drugs currently available that can effectively target cccDNA9, 10. Thus, any curative strategy should include a means to eliminate the episomal cccDNA (which supports viral replication) and integrated HBV DNA (which does not support viral replication but can code HBsAg) without inducing collateral cytotoxic effects in HBV-infected cells11.

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)-associated protein 9 (Cas9)-mediated genome editing is an appealing means to combat HBV infection12. This approach enables the destruction of the HBV cccDNA and the cleaving of the integrated HBV DNA. Although it has shown promise in HBV gene-editing and viral suppression both in vitro and in vivo13–15, this approach faces several challenges that need to be overcome for clinical application, e.g., its off-target effects and inefficient, non-specific in vivo delivery. Targeting specific HBV genes that are crucial for viral replication while avoiding off-target cytotoxic effects is key to the success of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated viral clearance. Additionally, the current CRISPR/Cas9 expression and/or delivery methods require viral vectors, which pose safety concerns for therapeutic application in humans12–16. These shortcomings have largely limited the use of CRISPR/Cas9-based therapeutics for HBV eradication. Synthetic CRISPR/Cas9 can be directed to the target genes to cleave any desired DNA sequences. This can be achieved by designing a guide RNA (gRNA) with approximately 20 nucleotides that match a particular sequence of the genome with downstream protospacer adjacent motifs (PAMs). Thus, synthetic gRNA/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) is a suitable non-viral formulation17, 18. Importantly, direct administration of synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs offers versatile and transient gene-editing in a controllable way compared with other delivery methods that depend on plasmid DNA (pDNA) or messenger RNA (mRNA), which exhibit varying transcriptional and translational activities and uncontrollable expression duration in vivo, and thus can result in off-target effects and unwanted immune responses19, 20.

In this study, we selected HBV-specific target genes that are crucial for HBV replication but are not homologous (off-target) with the human genome, synthesized a series of gRNA/Cas9 RNPs targeting these genes, and tested their antiviral activity and cytotoxicity in HBV-infected cell models. Our results show that synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs targeting HBV polymerase (P), surface (S), and viral enhancer and oncogenic (X) genes can efficiently inhibit HBV replication without causing any cytotoxic effects. These synthetic gRNA/Cas9-based gene-editing modalities warrant further investigation as a potential therapeutic drug for chronic HBV infection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. HBV cell lines and transfection with synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs:

The HepG2.2.15 Human Hepatoblastoma cell line (Cat# SCC249, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA) is a traditional HBV cellular model that is widely used for studying HBV infection and drug development21–22. HepG2.2.15 cells display constitutive HBV RNA transcription and DNA replication, but a lesser detection of cccDNA by Southern blot and PCR detection23. The HepG2/2.2.15 cells were cultured in DMEM (Cat# MT10013CV, Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) supplemented with 10% Fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin (50 ug/ml each; Fisher Scientific) and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 atmosphere. We used the Amaxa Cell Line Nucleofector Kit V (Lonza VCA-1003) to deliver gRNA/Cas9 into HepG2/2.2.15 cells stably expressing HBV. For each transfection, 160 μM gRNA and 160 μM tracrRNA were first incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes, followed by adding 80 μM Cas9 protein and incubating at 37°C for 15 minutes. Approximately 40 μM of the gRNA/Cas9 complex was transfected into HepG2/2.2.15 cells (5 × 105) following the manufacturer’s instructions. After 72 hours, the culture supernatants were harvested to measure HBV antigens by ELISA, and the cell pellets were used to determine HBV DNA or mRNA levels by real-time-PCR.

The HepDE19 cell line is tetracycline-controlled HBV stable cells maintained in the presence of 500 μg/ml G418 and 1 μg/ml tetracycline (Tet)24. Upon withdrawing Tet from the culture fluid of HepDE19 cells, pgRNA transcription, HBV DNA replication, cccDNA formation, and HBV e antigen (HBeAg) production gradually increase in a time-dependent manner25. To induce HBV replication, we cultured the cells in a Tet-free medium for 0–10 days, followed by measuring the expression of HBV antigens, HBV cccDNA, and pgRNA using methods previously described21–23. For cell transfection, HepDE19 cells were cultured in Tet-free medium for 2 days. The gRNA/Cas9 RNPs and Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX reagents were prepared in two separate tubes following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 125 ng gRNA, 500 ng GeneArt Platinum Cas9 nuclease, and 1 μl Cas9 Plus reagents were mixed in one tube, and 1.5 μl Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX reagent was added in a separate tube. The gRNA/Cas9 RNP solution was then transferred to the tube containing the Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX solution. The mixture was vortexed and incubated at 25°C for 10 min to form the gRNA/Cas9 RNP/Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX complex. Meanwhile, HepDE19 cells were seeded in a 24-well plate at 2.0 × 105 cells per well. The gRNA/Cas9 RNP/Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX complex was then added directly to the cell suspension, and the cells were incubated for 72 h, followed by assessing HBV replication with Tet-free medium as described above.

2.2. Infection of HepG2-NTCP cells with HBV and transfection with synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs:

HBV infectious particles were harvested from the supernatants of gRNA/Cas9-treated HepDE19 cells and used for the infection of HepG2-NTCP cells following a previously published method24, 25. Briefly, the supernatants of gRNA RNP-treated HepDE19 cells were harvested and concentrated using a PEG concentration kit (Cat# ab102538, Abcam, Waltham, MA). For HBV infection, 2.5 × 105 HepG2-NTCP cells were seeded in a 12-well plate and mixed with 10 μl concentrated HBV supernatants in 1 ml hepatocyte maintenance medium (HMM) (with 8% PEG8000 and 5% DMSO) at 37°C for 16 h. The culture media were changed daily with fresh HMM. After 8 days, the cells were harvested and HBV DNA and cccDNA levels were determined as described below.

In another experiment, 1×106 HepG2-NTCP cells were infected using supernatants containing HBV particles from HepDE19 cells that were maintained for 6 days. The HBV-infected HepG2-NTCP cells were transfected with gRNA5, gRNA9, gRNA5 plus gRNA9, or gRNAc RNPs as described above. The cells were maintained for 3 days in a complete culture medium and then harvested for HBV cccDNA detection by qPCR.

2.3. HBsAg and HBeAg ELISA:

The levels of HBsAg and HBeAg in the supernatants of cell cultures were determined by ELISA (Cat# KA0286 and NBP2–600029, Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The optical density of antigen levels was measured at 450 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer. The samples were run in triplicate, and the experiments were repeated at least three times.

2.4. HBV mRNA qPCR:

Total RNA was extracted from the cell pellets by the RNeasy Mini kit (Cat# 74104, QIAGEN, Germantown, MD), and 1 μg RNA was converted to cDNA using the Applied Biosystems High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Cat# 43-688-14, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA). Quantitative real-time PCR (real-time-qPCR) was performed using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Cat# 1725124, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The PCR primers were: HBV mRNA forward, 5’-GAGTGCTGTATGGTGAGGTG-3’, reverse, 5’-TTTGGGGCATGGACATTGAC-3’; HBV pgRNA forward 5’-CTCCTCCAGCTTATAGACC-3’, reverse 5’-GTGAGTGGGCCTACAAA-3’; and GAPDH forward 5’-ACAACTTTGGTATCGTGGAAGG-3’, reverse 5’–GCCATCACGCCACAGTTT C-3’. The gene expression levels were determined by the 2−ΔΔCq method and values were normalized to GAPDH expression as an internal control.

2.5. HBV DNA and cccDNA qPCR:

Total and protein-free HBV DNAs were extracted from whole cell lysate using the Hirt DNA method according to a previously published protocol26. For HBV cccDNA analysis, the protein-free DNA was treated with 10 units of T5 exonuclease (NEB) at 37°C for 30 min, followed by 95°C for 5 min, and diluted 4-fold with nuclease-free water. Next, the cccDNA was cleaned with a DNA clean and concentrator kit (ZYMO Research, Irvine, CA) and used for PCR. HBV total DNA and cccDNA were analyzed by real-time PCR using a TaqMan PCR assay. The primers and probe used to amplify HBV total DNA were: HBV total DNA forward: 5’-CCGTCTGTGCCTTCTCATCTG-3’, reverse 5’-AGTCCAAGAGTYCTCTTATGYAAGACCTT-3’, and internal probe: 5’-FAM-CCGTGTGCACTTCGCTTCACCTCTGC-TAMRA-3’. The primers and probe used to amplify HBV cccDNA (Genotype D, subtype ayw) were: forward: 5’-TCATCTGCCGGACCGTGTGC-3’, reverse 5’-TCCCGATACAGAGCTGAGGCGG-3’, and internal probe 5’-FAM-TTCAAGCCTCCAAGCTGTGCCTTGGGTGGC-TAMRA-3’. The PCR reactions were performed in 20 μl volumes and contained 2 μl DNA. The PCR conditions were: 95°C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 64°C for 30 s. The DNA levels were determined by the 2−ΔΔCq method and values were normalized to the control group.

2.6. HBV RNA detection by RNAscope:

RNAscope was performed using an assay kit from ACD (Newark, CA). Briefly, the cells were cultured and attached on cover glasses (8 mm in diameter, FisherSci) in a 24-well plate overnight, followed by fixation with 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF), dehydration, immobilization. Next, the slides were incubated with RNAscope hydrogen peroxide at room temperature (RT) for 10 min, followed by incubating with RNAscope Protease III diluted 1:5 with 1X PBS at RT for 10 min. Then, the RNAscope probe was hybridized at 40°C for 2 h in a hybridization oven, then processed with RNAscope 2.0 HD detection reagent. Finally, the slides were dried in a 60°C oven, briefly rinsed with pure xylene, and immediately covered with 1 drop of EcoMount (Fisher Scientific) by a coverslip (40 × 24 mm, FisherSci). Images were obtained using an EVOS microscope (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and analyzed by QuPath software and GraphPad Prism 7 (Irvine, CA).

2.7. HBV DNA mutagenesis determination by T7EI assay:

The HBV DNA sequences surrounding gRNA-binding sites were amplified by PCR. The PCR primers used for detecting the gRNA5 flanking region were: forward 5’-GACAAGAATCCTCACAATA-3’, reverse 5’- CATAGAGGTTCCTTGAGCAG −3’. The primers used for detecting the gRNA9 flanking region were: forward 5’-TACATCGTTTCCATGGCTGCTAG-3’, reverse: 5’- CAACTCCTCCCAGTCTTTAAAC −3’. All PCR products were verified by Sanger sequencing and subjected to a re-annealing process to induce heteroduplex formation. After re-annealing, the PCR products were treated with T7EI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) at 37°C for 30 min and analyzed using 3% agarose gels. The gel band images were acquired using a gel imaging system (Bio-Rad).

2.8. HBV DNA sequencing.

Following treatment with gRNA5/Cas9 + gRNA9/Cas9, or gRNAc/Cas9 RNPs, genomic DNA was isolated from HepDE19 cells using the PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Cat# K182001, Invitrogen). DNA fragments containing the gRNA target sequences were amplified by qPCR using primers flanking the cleavage sites. The PCR products were confirmed using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and purified using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Cat# 28704, Qiagen). Sequencing of the extracted DNA fragments was performed by GENEWIZ (Chelmsford, MA) using Sanger’s sequencing method. The PCR primers used for the detection of gRNA5 and gRNA9 flanking regions are described above. The sequencing readouts were aligned with the gRNAc, which was compared to the HBV sequence in the database (ayw strain, Genbank accession number: NC_003977.2). The Chromas’s software (Technelysium DNA sequencing software) was used to read the nucleotide peaks, and the alignment of two or more sequences was performed using the BLAST tool from NCBI-BLAST to compare the nucleotide sequences.

2.9. Cytotoxicity assay:

We used the MTT assay to determine metabolic activity and cell viability as an indicator of cellular cytotoxicity. Twenty-four hours after gRNA/Cas9 transfection, the cells were cultured in a Tet-free medium for an additional 24 h. For measuring cell proliferation, the cells were cultured in the Tet-free medium for an additional 3 days in a 96-well plate. The culture medium (100 ul) was changed and MTT reagent (0.5 mg/ml) was added at 37°C for 4 h, followed by measuring the absorbance at 550–690 nm using a spectrophotometer (BioTek SYNERGY H1).

Statistical analysis:

All data were analyzed using Prism 7 software and are expressed as mean ± SE. Comparisons between two groups were made using a parametric paired or unpaired t-test for normally distributed data or a non-parametric Wilcoxon paired t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test for non-normal distributions. Comparisons among multiple groups were made using a one-way ANOVA at a 95% confidence level (Tukey’s honest significance test). P-values <0.05 (*) were considered statistically significant and p-values <0.01 (**), <0.001 (***), or <0.0001 (****) were considered very significant.

3. Results

3.1. Design and synthesis of gRNA/Cas9 RNPs targeting HBV genomes:

Identifying gRNAs targeting specific HBV genes with minimal predicted off-target effects is the first step in designing a CRISPR/Cas9 RNP for HBV treatment. The major challenge of selecting these specific targets on HBV DNA is the high heterogeneity of the HBV genome (i.e., HBV quasispecies), complicating the design of gRNAs that would target multiple or all HBV genotypes (A-H)27. Thus, identifying new gRNAs for specific Cas9 targeting highly conserved regions of HBV DNA is essential for the CRISPR/Cas9 design to move into clinical application for HBV eradication.

To select the most specific and potent targeting sites within the HBV genome, we used e-CRISP online gRNA designing tool to compare HBV sequences for potential HBV gRNA targeting sites that have the best-predicted on-target (i.e., HBV sequences that are critical for viral replication) and lowest off-target effects (i.e., 0% homology with the human genome). We compared the genomic DNA sequences of 8 HBV genotypes (A-H) originating from distinct regions and identified 9 target sites in highly conserved regions on the HBV genome, including polymerase (P), capsid (C), surface (S), and X genes (Fig. 1A). We synthesized gRNAs based on the ayw strain (Genbank accession number: NC_003977.2), and these gRNAs carry an NGG codon (where N can be any nucleotide) at the 3’-end following the HBV sequence complementary to the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), which can be recognized by the Cas9 nuclear localization signal (NLS) that can direct gRNA/cas9 RNP into the cell nucleus. The features of these selected gRNAs, including their name, lengths, start/end positions, orientation (plus/minus strands), nucleotide sequences, % of ATGC nucleotides, seed GC contents, S-/E-/Doench-scores, and numbers of mismatch hits, are presented in Table 1. The on-target antiviral activity and off-target cytotoxic effects of these 9 HBV-specific gRNA/Cas9 RNPs were tested and compared with a gRNAc using different HBV-infected cell model systems.

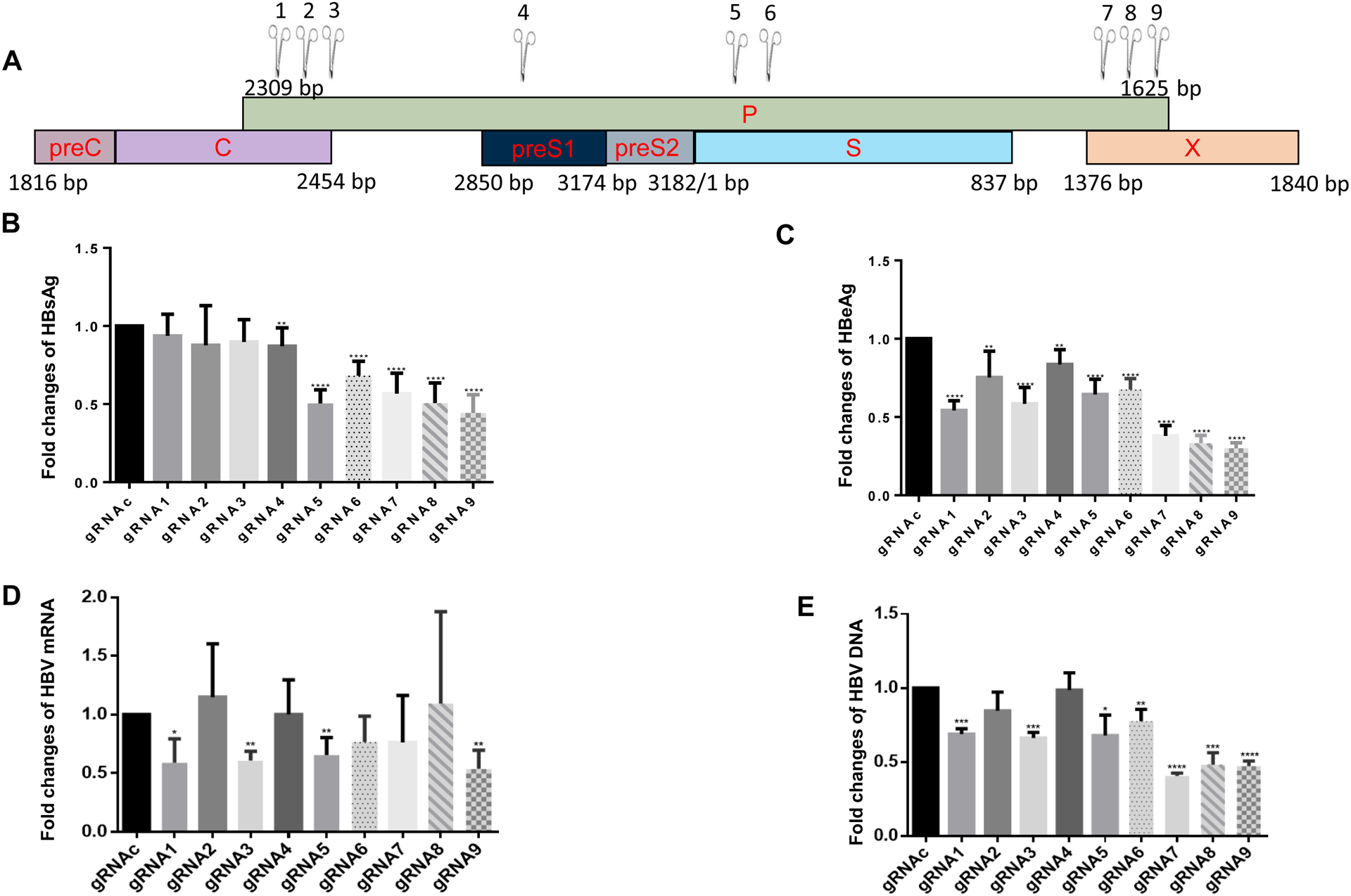

Fig. 1. Designing and selecting gRNAs to target the HBV genome and inhibit HBV replication.

(A) The E-CRISPR gRNA designer was used to compare the sequences of 8 HBV genotypes (genotype A-H) and identify 9 potential HBV gRNA target sites in the HBV genome (denoted by scissors), including polymerase (P), capsid (C), surface (S), and non-structural X genes. (B) HBsAg levels in the supernatants of HepG2/2.2.15 cells transfected with synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs for 3 days, determined by ELISA. (C) HBeAg levels in the supernatants of HepG2/2.2.15 cells 3 days after nucleofection, determined by ELISA. (D) HBV mRNA levels in HepG2/2.2.15 cells 3 days after nucleofection, determined by real-time RT-PCR. (E) HBV DNA levels in HepG2/2.2.15 cells 3 days after nucleofection, determined by real-time PCR. Data shown are means ± SE from three independent experiments carried out in triplicates. Values were normalized to the gRNAc-treated cells as a control. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001.

Table 1.

The features of gRNAs designed and tested in this study

| Name | HBV gRNA 1 | HBV gRNA2 | HBV gRNA3 | HBV gRNA4 | HBV gRNA5 | HBV gRNA6 | HBV gRNA7 | HBV gRNA8 | HBV gRNA9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| Start | 2318 | 2342 | 2346 | 2902 | 297 | 349 | 1422 | 1501 | 1525 |

| End | 2341 | 2365 | 2369 | 2925 | 320 | 372 | 1445 | 1524 | 1548 |

| Strand | minus | minus | plus | minus | Plus | plus | minus | minus | minus |

| Nucleotide sequence | GATTGAGACCTTCGTCTGCG NGG | GATTGAGATCTTCTGCGACG NGG | GTCGCAGAAGATCTCAATCT NGG | GCTCCTACCTTGTTGGCGTC NGG | GTTATCGCTGGATGTGTCTG NGG | GCTATGCCTCATCTTCTTGT NGG | GTCGGAACGGCAGACGGAGA NGG | GAAGCGAAGTGCACACGGTC NGG | GGTCTCCATGCGACGTGCAG NGG |

| Gene Name | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Transcripts | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Transcript∷ Exon | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Number of Cpg Islands hit | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Sequence around the cutside | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| %A %C %T %G | 24 36 16 24 | 24 36 20 20 | 28 24 20 28 | 32 28 8 32 | 8 20 32 40 | 8 24 48 20 | 4 48 28 20 | 12 40 24 24 | 20 40 16 24 |

| S-Score | 40 | 60 | 80 | 80 | 100 | 100 | 60 | 60 | 80 |

| A-Score | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| E-Score | 68.3874 | 80.6503 | 53.3841 | 54.3242 | 61.7668 | 56.9203 | 60.2608 | 61.6696 | 67.6774 |

| percent of total transcripts hit | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Target | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Match-start | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Match-end | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Matchstring | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Editdistance | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Number of Hits | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Direction | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| CDS_score | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Exon_Score | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| seed_GC | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Doench_Score | 0.537490841 | 0.799378984 | 0.04104376 | 0.115975383 | 0.303114158 | 0.464274315 | 0.021491185 | 0.085875578 | 0.305634687 |

| Xu_score | 0.181883387 | 0.433139128 | 0.128164786 | 0.000235774 | 0.18522702 | −0.018258996 | 0.391550943 | 0.297604811 | 0.478239533 |

| Chromosome | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Genomic start | 1818 | 1842 | 1846 | 2402 | −203 | −151 | 922 | 1001 | 1025 |

| Genomic End | 1841 | 1865 | 1869 | 2425 | −180 | −128 | 945 | 1024 | 1048 |

3.2. Synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs inhibit HBV replication in HepG2/2.2.15 cells:

Because the hepatoma cell line HepG2/2.2.15 is a traditional HBV cellular model used to test the efficacy and cytotoxicity of anti-HBV drugs28, we first tested our synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs for their antiviral efficiency in HepG2/2.2.15 cells. After 3 days of nucleofection, we measured HBsAg and HBeAg levels in the supernatants of the treated cells. As shown in Fig. 1B, HBsAg levels significantly decreased in cells transfected with gRNA4–9/Cas9 compared with the scrambled gRNAc. In addition, transfection with gRNA5, gRNA8, or gRNA9 led to a 50% reduction in HBsAg expression. The levels of HBeAg were also reduced in all gRNA/Cas9-transfected cells, with >50% reduction after treatment with gRNA7, gRNA8, or gRNA9 compared with the gRNAc (Fig. 1C). Next, total RNA from HepG2/2.2.15 cells transfected with gRNA/Cas9 was isolated and the relative HBV mRNA expression levels were determined by real-time PCR. The results showed a remarkable suppression (~50% reduction) of HBV mRNA expression in cells transfected with gRNA1, gRNA3, gRNA5, or gRNA9 compared with gRNAc (Fig. 1D). Correspondingly, we observed a significant reduction in the HBV DNA level in the transfected cells, with gRNA7, gRNA8, or gRNA9 transfection showing >50% reduction compared with the gRNAc transfection (Fig. 1E). The gRNAs were designed to target different region of HBV genome and thus may elicit different antiviral effects on the expression of HBV antigens, as well as the levels of HBV mRNA and HBV DNA. The differences in these virologic readouts in the treated cells may also result from varying sensitivity of the detection methods we used. Because the transfection efficiency in the HepG2-based cell line was ~50%, a 50% reduction in these virologic readouts represents a remarkable antiviral effect in this HBV-infected cell model. Based on their inhibitory efficacy and specific targeting sites, we chose gRNA5 (which targets HBV P/S genes) and gRNA9 (which targets HBV P/X genes) for further testing using an advanced HBV-infected cell model.

3.3. Synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs inhibit HBV replication in HepDE19 cells:

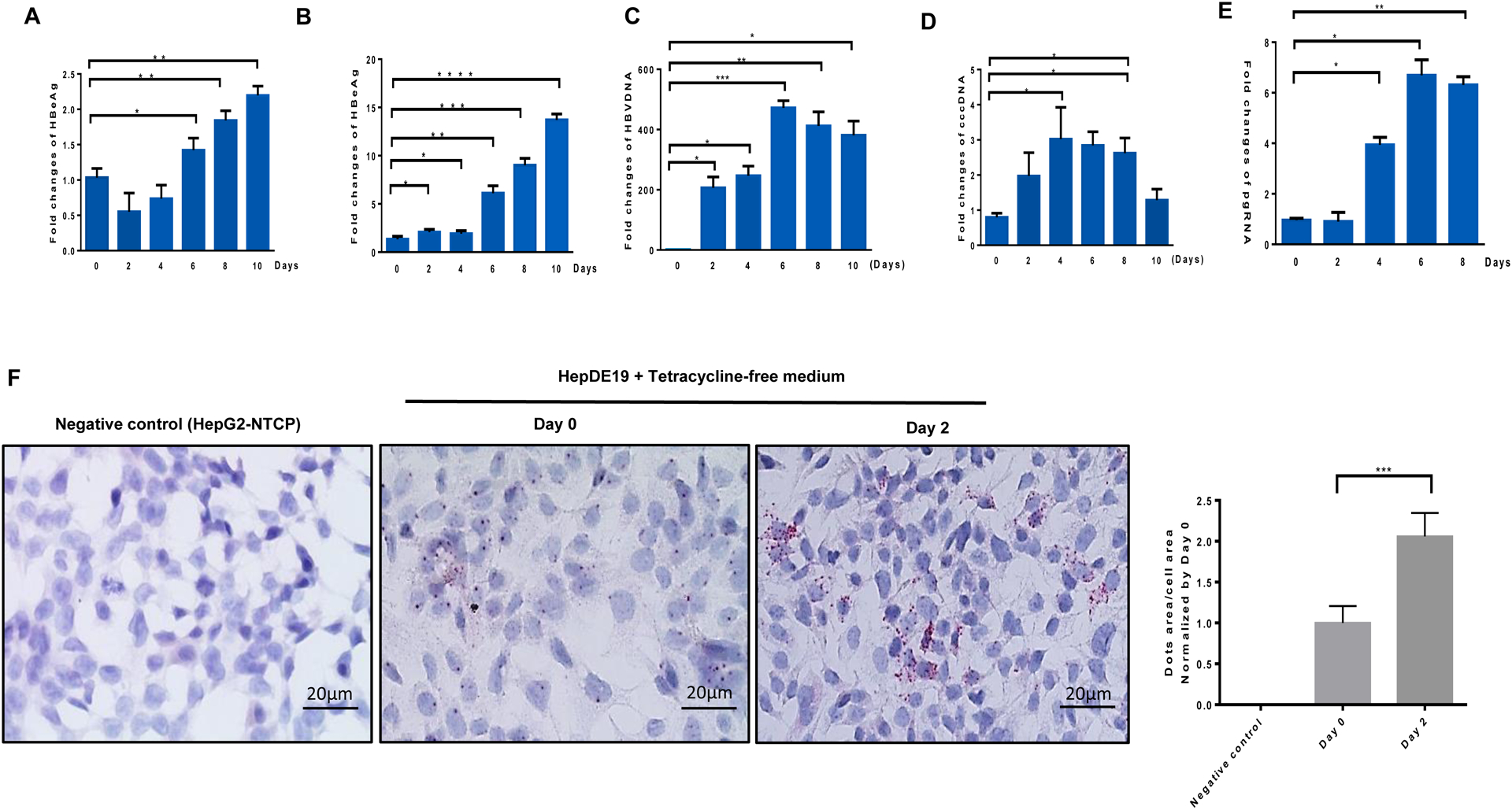

The HepDE19 cell line is a robust HBV cell culture system that can support HBV replication and propagation. This cell line was maintained in the presence of 1 μg/ml tetracycline (Tet) and G418 (500 μg/ml). In this stable cell line, HBV replication is under the control of a Tet responsive promoter, which results in a controllable production of HBV compared with the HepG2.2.15 cell line, and the expression of pgRNA, cccDNA, and HBeAg are induced when the cells are cultured in Tet-free medium (for viral induction)21. As shown in Fig. 2, HepDE19 cells exhibited a time-dependent increase in the expression of HBsAg (Fig. 2A) and HBeAg (Fig. 2B), as determined in the culture supernatants by ELISA. In addition, real-time PCR revealed a time-dependent increase in total HBV DNA (Fig. 2C), cccDNA (Fig. 2D), and pgRNA (Fig. 2E) in HepDE19 cells cultured with Tet-free medium. We also detected increases in HBV RNA expression by RNAscope in HepDE19 cells at day 0 and day 2 after incubation in Tet-free medium (Fig. 2F). With these detectable HBV readouts, this cell line can serve as a reliable model to test the efficacy of antiviral drugs.

Fig. 2. Induction of HBV replication in HepDE19 cells by tetracycline-free culture medium.

(A-B) Time-dependent induction of HBsAg and HBeAg levels in HepDE19 cells cultured in tetracycline-free (Tet-free) medium, determined by ELISA. (C-E) HBV DNA, cccDNA, and pgRNA levels in HepDE19 cells cultured in Tet-free medium, determined by real-time PCR. Data are presented as mean ± SE from three independent experiments carried out in triplicates. Values were normalized to the gRNAc-treated cells as a control. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 (F) Representative images and summary data of the RNAscope results showing HBV RNA positive signal (red dots) in HepDE19 cells cultured in Tet-free medium for 0 and 2 days. RNAscope imaging of HepG2-NTCP cells without HBV infection is shown as a negative control. The data were analyzed by QuPath software to quantify the positive HBV RNA dot area versus cell area from 6 imaging areas.

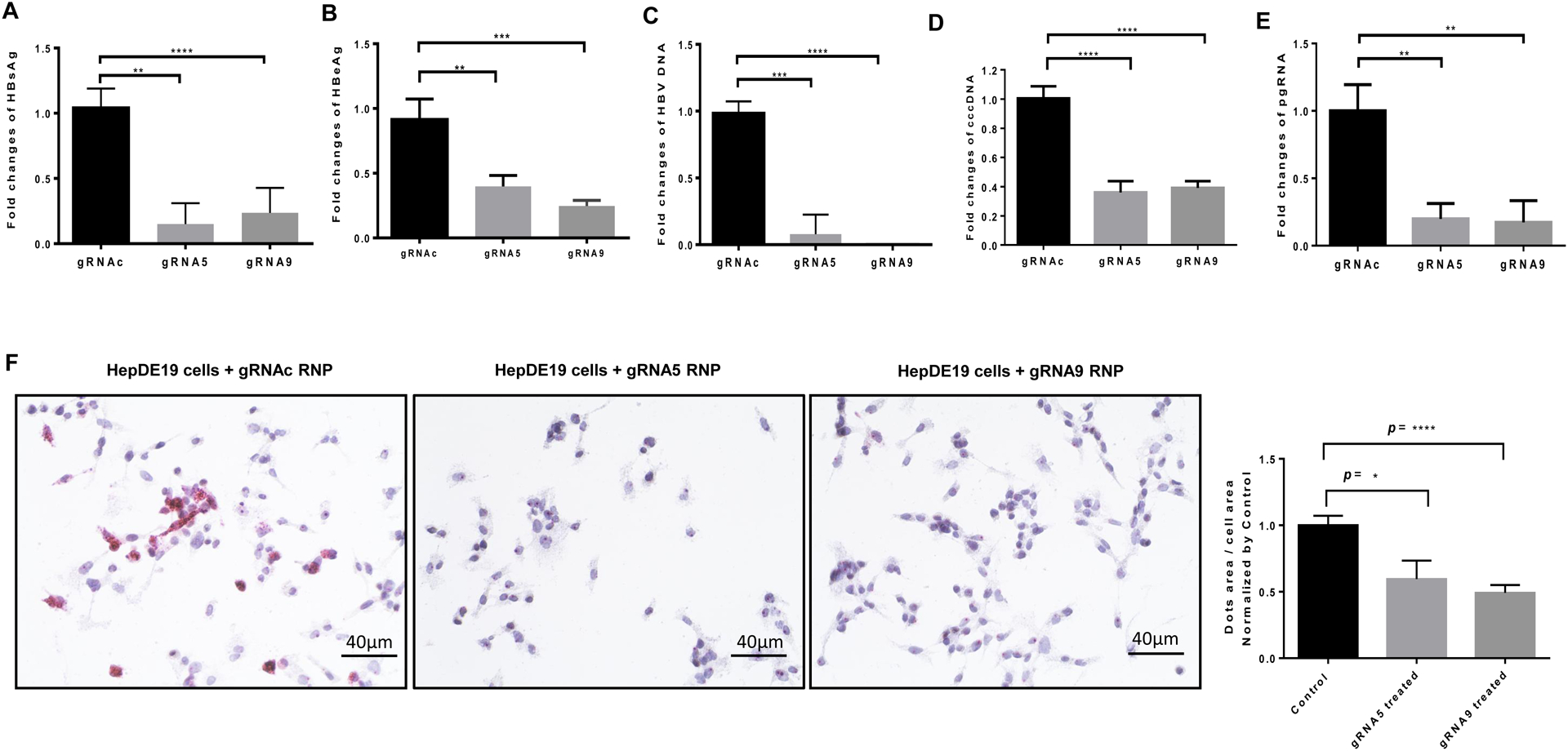

Next, we tested the antiviral efficacy of our synthetic gRNA5 and gRNA9 in HepDE19 cells. As shown in Fig. 3, HBV replication was significantly suppressed in HepDE19 cells transfected with gRNA5 or gRNA9 compared with the scrambled gRNAc, as evidenced by the significant decreases in the expression of HBsAg (Fig. 3A), HBeAg (Fig. 3B), total HBV DNA (Fig. 3C), cccDNA (Fig. 3D), pgRNA (Fig. 3E), and HBV RNA (Fig. 3F) following incubation with Tet-free medium for 3 days. Taken together, these results demonstrate that gRNA5 or gRNA9 can significantly suppress HBV replication in HBV-infected cells.

Fig. 3. Suppression of HBV replication in HepDE19 cells by synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs.

(A-B) HBsAg and HBeAg levels in the supernatants of HepDE19 cells transfected with gRNA5 or gRNA9 RNP versus control gRNAc, determined by ELISA. (C-E) HBV DNA, cccDNA, and pgRNA levels in HepDE19 cells transfected with gRNA5 or gRNA9 RNP versus gRNAc, determined by real-time PCR. Data are means ± SE from three independent experiments carried out in triplicates. Values were normalized to the gRNAc-treated cells as a control. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. (F) HBV RNA levels in HepDE19 cells transfected with gRNA5 or gRNA9 RNP versus gRNAc, determined by RNAscope. Representative RNAscope images and summary data are shown. The data were analyzed by QuPath software to quantify the positive HBV RNA dot area versus cell area from 6 imaging areas and normalized by gRNAc.

3.4. HepDE19 cells and HepG2-NTCP cells transfected with gRNA/Cas9 RNPs produce fewer infectious HBV particles:

Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) is a functional receptor for human HBV29. The human hepatoma cell line HepG2 is not susceptible to HBV infection due to lack of NTCP; however, HepG2 cells transfected with NTCP expression plasmids (HepG2-NTCP) are susceptible to natural HBV infection25. To further characterize the inhibitory effects of our synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs on HBV replication, we incubated HepG2-NTCP cells with supernatants collected from gRNA/Cas9 RNP-transfected HepDE19 cell culture (after 4 days). Genomic DNA was isolated from HepG2-NTCP cells on day 8 after HBV infection and used for the assessment of HBV replication. Compared with cells infected with supernatants from the gRNAc-treated cells, HepG2-NTCP cells infected with the supernatants of gRNA5- and gRNA9-treated HepDE19 cells had significantly lower HBV DNA levels (Fig. 4A). Moreover, the amount of HBV cccDNA was also remarkably lower in HepG2-NTCP cells infected with the supernatants of gRNA5- and gRNA9-transfected HepDE19 cells (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that gRNA5- or gRNA9-treated HepDE19 cells produce fewer copies of infectious HBV particles capable of infecting HepG2-NTCP cells.

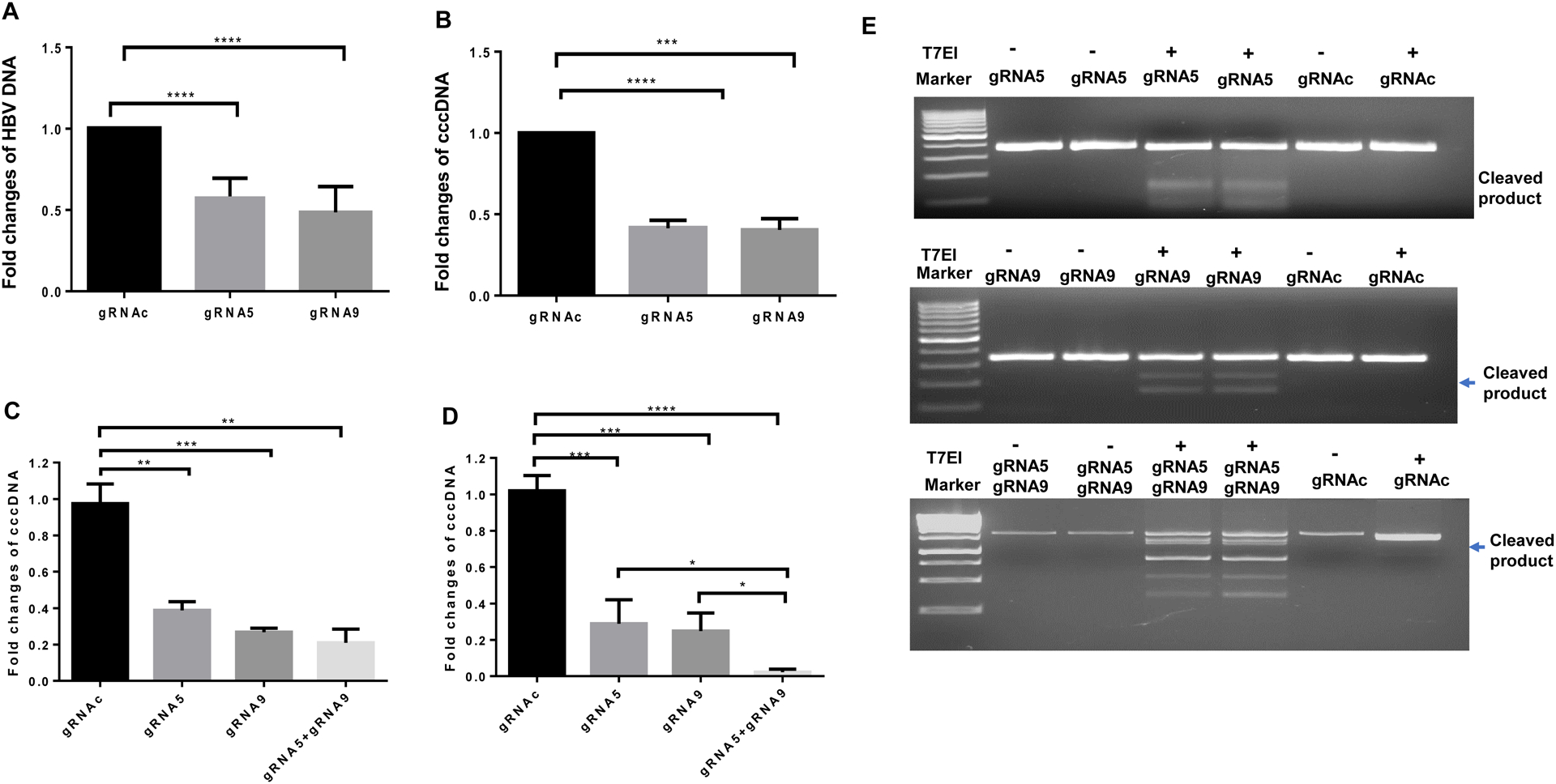

Fig. 4. Antiviral effects of synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs.

(A-B) Detection of HBV DNA and cccDNA in HepG2-NTCP cells 8 days after HBV infection using the supernatants of HepDE19 cells transfected with gRNA5, gRNA9, or gRNAc for 3 days, determined by real-time RT-PCR. (C) HBV-infected HepG2-NTCP cells were transfected with gRNA5, gRNA9, or gRNAc for 3 days, followed by measuring HBV cccDNA levels by real-time RT-PCR. Values were normalized by the gRNAc-transfected. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. (D) HBV cccDNA levels in HepDE19 cells transfected with gRNA5, gRNA9, or gRNAc for 3 days, and the same treatment was repeated 4-times. DNA was isolated and HBV cccDNA levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. (E) T7E1 assay to detect mismatch nucleotides in HBV DNA from HepDE19 cells transfected with gRNA5 or gRNAc (upper panel), gRNA9 or gRNAc (middle panel), and gRNA5 plus gRNA9 (lower panel) and treated with or without T7E1. The cleaved DNA products are shown (lower bands).

To further characterize the anti-HBV activities of gRNA5 and gRNA9 RNPs in newly infected cells, we used HBV particles derived from HepDE19 cells to infect HepG2-NTCP cells, followed by transfecting the newly HBV-infected HepG2-NTCP cells. We found that transfection with gRNA5, gRNA9, or gRNA5 plus gRNA9 significantly reduced HBV cccDNA levels (Fig. 4C).

We next sought to determine whether repeated treatments with gRNA/Cas9 can increase the antiviral efficacy in HepDE19 cells with stable HBV infection. To this end, HepDE19 cells cultured with Tet-free medium for 2 days were transfected with gRNA5, gRNA9, or gRNA5 plus gRNA9 every 3 days for a total of four treatment. After four treatments, gRNA5 or gRNA9 alone elicited ~70–80% reduction in HBV cccDNA compared with the scrambled gRNAc treatment (Fig. 4D). Unexpectedly, four treatments with gRNA5 or gRNA9 alone did not increase the antiviral efficacy more than the levels observed with one-time treatment (Fig. 3D). However, four-times treatments with gRNA5 plus gRNA9 elicited a significant reduction (> 95%) in HBV cccDNA levels compared with the scrambled gRNAc (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these results suggest that gRNA5 and gRNA9 are good candidates for HBV drug development.

3.5. Cleavage of HBV DNA by synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs in HepDE19 cells:

DNA cleavage by CRISPR/Cas9 results in double-strand breaks (DSBs), which are primarily repaired by the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair pathway, resulting in gene mutations30, 31. Thus, detecting DNA cleavage and mismatch mutations following CRISPR/Cas9-mediated DNA damage repair is important for confirming gene-editing effects. To assess the capacity of our gRNA/Cas9 RNP candidates to induce cleavages in HBV DNA in HepDE19 cells, we performed a mismatch sensitive T7 endonuclease 1 (T7E1) assay35, following transfection of HepDE19 cells with gRNA5, gRNA9, gRNA5 plus gRNA9, or gRNAc RNPs for 3 days. This assay allows for the detection of specific gene cleavage or mutations in HBV DNA in the treated cells. The mutagenesis was determined based on the DNA fragments detected after the gRNA/Cas9-mediated cleavage of the HBV DNA following T7E1 digestion. As shown in Fig. 4E, DSBs were introduced in HBV DNA by T7E1 treatment following HepDE19 cell transfection with gRNA5 (upper panel), gRNA9 (middle panel), and gRNA5 plus gRNA9 (lower panel), but not in the gRNAc-transfected cells or in cells without T7E1 treatment. These results confirm that gRNA5, gRNA9, or gRNA5 plus gRNA9 can induce cleavages and mutations in targeted HBV DNA.

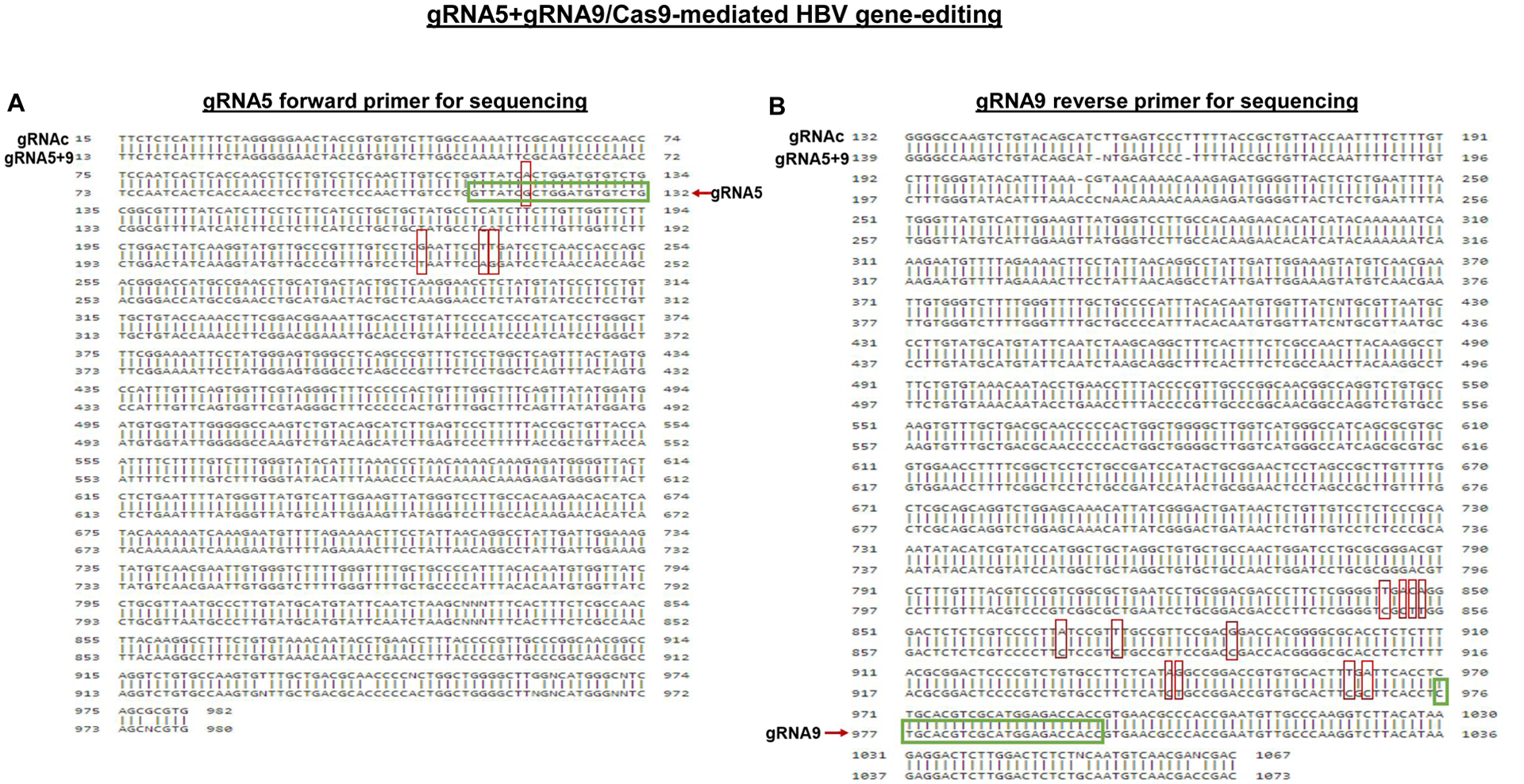

Following a successful CRISPR/Cas9 cleavage, DNA damage repair pathways are initiated, and nucleotide mutagenesis occurs in the targeted genome, introducing substitution mutations. To confirm mutations in the edited (damaged/repaired) HBV DNA, we performed Sanger sequencing after PCR amplification of the HBV DNA fragments containing the gRNA target sites from the gRNA5 plus gRNA9-treated HepDE19 cells. Compared to the treatment with gRNAc, which has a sequence identical to the HBV DNA sequence in the database (ayw strain, Genbank accession number: NC_003977.2), we observed multiple mismatch substitution (red boxed) mutations at and/or around the gRNA5 and gRNA9 target sites in treated cells (Fig. 5). These results confirm the targeted mutations within HBV genes in HepDE19 cells treated with gRNA5 and gRNA9 RNPs.

Fig. 5. DNA sequencing of gRNA5 + gRNA9/Cas9 RNP-treated HepDE19 cells.

The cell treatment, genomic DNA isolation, and target gene amplification are described in the Methods section. Sanger DNA sequencing of the PCR products was performed using primers flanking region covered by the gRNA5 forward primer (A) and gRNA9 reverse primer (B). The sequencing data were aligned and compared with the scramble control (gRNAc), which is identical to the HBV DNA sequence database (ayw strain, Genbank accession number: NC_003977.2). The Chromas DNA sequencing software was used to read the nucleotide peaks, and the alignment of two or more sequences was performed using BLAST tool (from NCBI-BLAST) to compare the nucleotide sequences. The representative HBV DNA sequencing data with gRNA5 and gRNA9 targeted sites (green boxes) as well as the nucleotide substitution mutations (red boxes) are shown.

3.6. Cytotoxicity of gRNA/Cas9 RNP in HepDE19 cells:

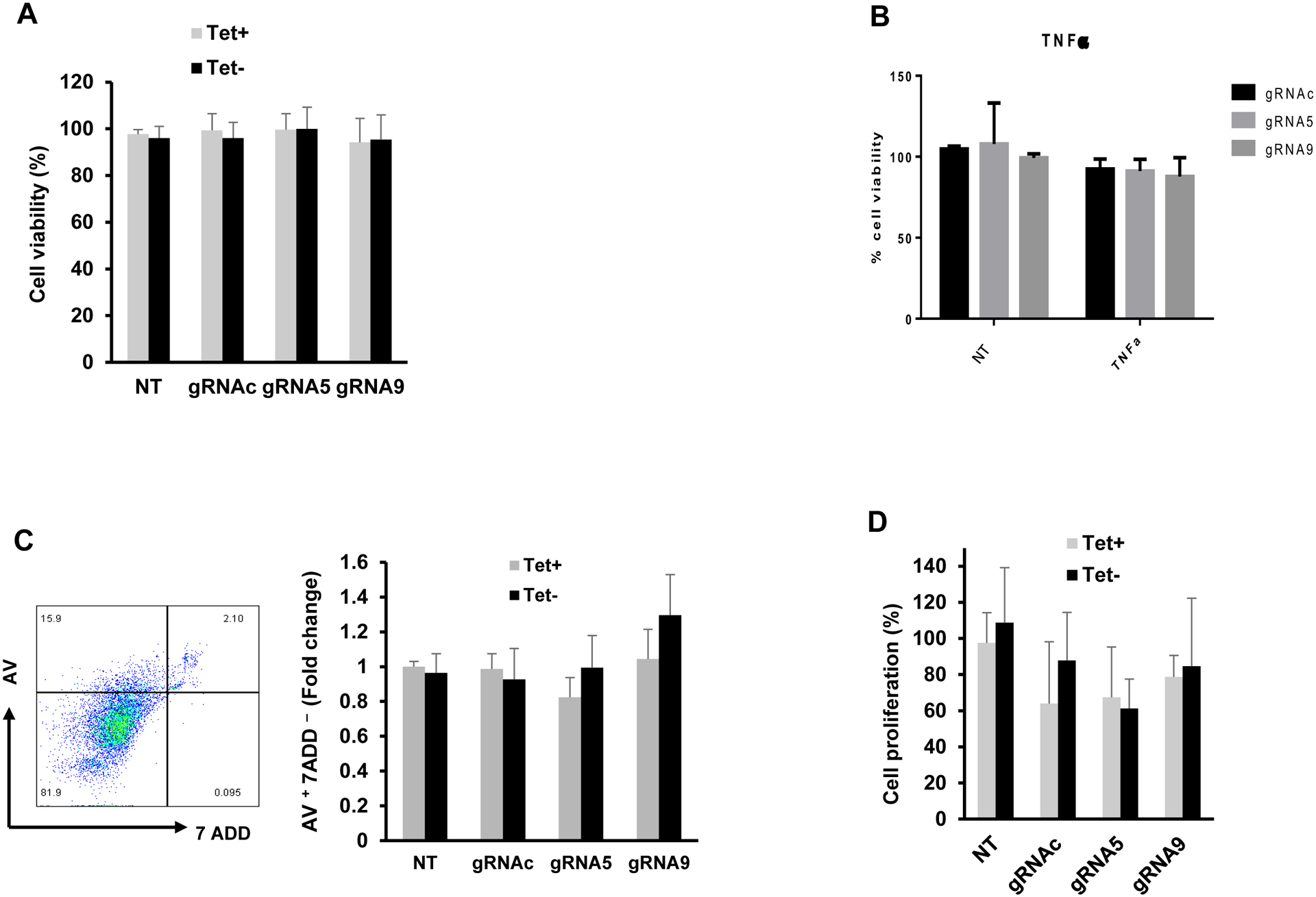

NAD(P)H-dependent cellular oxidoreductase enzymes reduce the tetrazolium MTT (3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol 2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) salt into insoluble formazan, which indicates the overall survival and metabolic activity of a living cell. To determine whether gRNA5/Cas9 or gRNA9/Cas9 exert any cytotoxic effects on HepDE19 cells, we first measured cell viability after transfection with gRNA5 or gRNA9 in the presence or absence of Tet-free medium (for HBV induction) for 24 h using the MTT assay. As shown in Fig. 6A, compared with the non-transfected (NT) control, we did not observe any significant differences in the viability of the gRNA5- or gRNA9-transfected HepDE19 cells. Since HBV itself is not a direct cytopathic pathogen but can induce cell injury via immune-mediated mechanisms, we measured the viability of transfected and non-transfected HepDE19 cells cultured in a Tet-free medium in the presence of TNFα, which can induce apoptotic cell death. We did not observe any cytotoxic effects from gRNA5 or gRNA9 treatment compared with the gRNAc or control (Fig. 6B). Moreover, flow cytometry analysis was performed to detect the cell surface apoptotic marker annexin V and the loss of the plasma membrane integrity (measured by up taking 7-ADD). We then evaluated cell apoptosis by measuring the Av and 7ADD levels in gRNA-transfected HepDE19 cells with or without Tet-free medium. We did not observe any significant differences in cell apoptosis among the different treatments (Fig. 6C). Finally, we assessed the proliferative ability of HepDE19 cells with or without gRNA transfection for 3 days, using the MTT assay. We found no significant differences in cell proliferation (Fig. 6D). Taken together, these results indicate that our synthetic gRNA5/Cas9 and gRNA9/Cas9 RNPs are not cytotoxic to human hepatocytes.

Fig. 6. Cytotoxic effects of synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs.

(A) Cell viability assessment by MTT assay of HepDE19 cells transfected with gRNA5, gRNA9, or gRNAc and cultured in the presence or absence of Tet-free medium (for HBV induction) for 24 h. (B) Cell viability assay of HepDE19 cells transfected with gRNA5, gRNA9, or gRNAc and cultured in Tet-free medium in the presence or absence of 10 ng/ml of TNFα. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis in HepDE19 cells transfected with gRNA5, or gRNA9, or gRNAc and cultured in the presence or absence of Tet-free medium for 3 days, determined by Av and 7ADD staining. (D) The proliferative ability of HepDE19 cells transfected with gRNAc, gRNA5 or gRNA9 and cultured in the presence or absence of Tet-free medium for 3 days, determined by MTT assay. Data are means ± SE from at least three independent experiments. Values were normalized by the gRNAc-transfected cells. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001.

4. Discussion

CRISPR/Cas9 can induce sequence-specific cleavage or mutation in HBV DNA that is integrated into the host cell genome and disrupt HBV cccDNA11–16 32–35. The use of CRISPR/Cas9 is currently the best method for the functional inhibition of HBV cccDNA; however, its off-target effects and delivery by viral vectors create safety concerns in human applications34. In the present study, we used synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs to develop CRISPR/Cas9-mediated HBV gene-editing drugs. We designed a series of gRNAs targeting different HBV genes crucial for HBV replication and tested their antiviral efficacy and cellular cytotoxicity in stably infected HBV cell lines, Hep2.2.15 and HepDE19, as well as in HBV-infected hepatoma cells expressing HBV receptor (HepG2-NTCP). We demonstrated that these synthetic HBV gRNA/Cas9 RNPs can efficiently suppress HBV replication, as evidenced by the significant reduction in HBV DNA, cccDNA, pgRNA, mRNA, and HBsAg as well as HBeAg levels in the stably HBV-producing cell lines and in newly HBV-infected HepG2-NTCP cells. While the molecular mechanisms underlying this viral suppression remain unclear, these drugs likely induce rapid cleavage or mutation in HBV DNA, which was confirmed by the mismatch cleavage assay and Sanger DNA sequencing, resulting in a high percentage of DNA damage that cannot be fully repaired by the host cell DNA repair machinery35, 36. These findings suggest that our synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs can be employed as a potential HBV DNA-editing drug to combat chronic HBV infection.

HBV cccDNA serves as a template for viral pgRNA/mRNA synthesis and is resistant to antiviral NA treatment in patients with chronic HBV infection8, 9. Here, we demonstrated that our specifically designed and selected gRNA (gRNA5 and/or gRNA9)/Cas9 RNPs, individually or in combination, can significantly reduce HBV cccDNA levels in stably HBV-transfected cells. Specifically, our results showed that one-time or repeated (4-times) transfection of HepDE19 cells with gRNA5, gRNA9, or gRNA5 plus gRNA9 RNPs can reduce HBV cccDNA by ~70–80% (with a single gRNA transfection) and >95% (with repeated transfection of gRNA5 plus gRNA9) compared with the control gRNAc transfection (Fig. 3D, Fig. 4D). Interestingly, while repeated transfection with a single gRNA (gRNA5 or gRNA9) reduced HBV cccDNA to a level similar to one-time transfection, repeated transfection with gRNA5 plus gRNA9 RNPs combined (i.e., dual DNA excision) led to a more pronounced (>95%) reduction in HBV cccDNA (Fig. 4D). T7E1 cleavage assay and Sanger DNA sequencing confirmed specific HBV DNA gene-editing events (mutations) at or near the sites targeted by gRNA5 and gRNA9. It should be noted that upon repeating the DNA sequencing several times, we learned that verifying DNA mutations using Sanger sequencing can be tricky since the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene-editing (mutations after DNA damage and repair) does not always modify the target genes exactly at the expected sites and with alterations in the same nucleotides. The gene-editing process often introduces random mutations (insertion, deletion, or substitution) at or around the gRNA targeting (binding) sites, where Cas9 nuclease protein-generated DNA damages are repaired by the NHEJ pathway. Because this DNA damage and repair process is a biological event that takes place within the treated cells, it can result in different nucleotide mutations in different batches of cells and generate a mixture of DNA products, despite applying the same treatment (with gRNA/Cas9 transfection) conditions and sequencing method. Therefore, it is likely that, after DNA damage repair, gRNA/Cas9-mediated HBV gene-editing by a single gRNA generates new HBV variants that are replication capable but less competent in supporting HBV cccDNA reproduction. Importantly, dual excision (i.e., by gRNA5 plus gRNA9) may lead to multiple DNA damages (which is supported by the DNA sequencing data) that are more difficult to repair. Thus, repeated treatment will increase the chance of cuttings in the uncut genes due to increased cell transfection rate with the dual gene-editing drugs, leading to a more pronounced (>95%) inhibition of HBV cccDNA formation. The most common outcome of viral cccDNA damage induced by CRISPR/Cas9 is the repair of DSBs by the NHEJ and/or HR pathways, which result in mutations and/or reduction in cccDNA if left unrepaired and thus will prevent the virus from escaping the gene-editing process and producing replicable new variants. Because HBV cccDNA methylation can affect the antiviral activity of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene excision, modulation of the DNA repair pathways to enhance CRISPR/Cas9 activity may facilitate the eradication of HBV cccDNA13, 14.

The integration of HBV DNA into the host genome is an obstacle for curing HBV infection and an important risk factor in hepatocarcinogenosis37–39. While the integrated HBV DNA in cellular chromosomes is not a viral replicable template as HBV cccDNA (which can transcribe a full-length pgRNA to support viral replication), the integrated HBV DNA may contribute to HBV pathogenesis via the expression of large amounts of HBsAg and modulation of cellular gene expression and chromosomal stability. Many HBV integration events occur within fragile sites, such as TERT, FN1, MLL4, ROCK1, and SENP539–41, which are linked to oncogenesis and cancer development42. A recent study demonstrated that the CRISPR/Cas9 RNP-based gene editing can modify the function of cccDNA and interrupt the replication of HBV DNA36. In our study, we found that synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs can inhibit HBV DNA replication in multiple HBV cellular models with integrated HBV DNA, suggesting that our CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing approach can inactivate HBV gene expression from the integrated HBV DNA and potentially prevent chromosomal translocation and instability in the host cell genome.

The use of synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs for gene-editing is an appealing approach because it can induce rapid DNA cleavage and has low off-target effects and low risk of oncogenic mutagenesis and can easily be produced for use in clinical applications. We selected nine gRNA target sites on HBV genomes with the highest levels of conservation among HBV strains and the lowest homologous (off-target) on the host genome. Our results showed that only gRNA5 (which targets P and S genomes) and gRNA9 (which targets P and X genomes) were the most specific and potent gRNAs in inactivating HBV replication. The regions targeted by these gRNAs contain the HBV polymerase, the S gene, and the viral enhancer and oncogenic X gene, which are all critical for HBV activity34, 40–43. Therefore, we propose that these genomic regions are optimal target sites for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated HBV gene-editing. These results warrant further investigation to test the efficacy of gRNA5 and gRNA9 RNPs in eradicating HBV infection. Theoretically, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene-editing/cleavage will only interfere with the translation of the target gene, however, we noticed that the HBV DNA, cccDNA, and pgRNA levels were all suppressed following treatments with our gRNA RNPs. We speculate that the lower levels of HBV RNA transcripts we observed in this study are secondary to the inhibited HBV cccDNA, or that the introduced DNA mutations may lead to the instability of HBV RNA to a certain extent. Further studies are needed to illustrate the underlying mechanisms of these events.

Although we did not observe any significant cytotoxic effects from our synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs in this in vitro system, off-target effects are always a concern for any CRISPR/Cas9 technology when applied in vivo. Even though CRISPR/Cas9 predominantly recognizes the intended target sites, previous high-throughput genome-wide analyses44, CRISPR/Cas9 toxicity screens45, and SITE-seq biochemical methods46 have shown evidence of off-target effects due to CRISPR/Cas9 target mismatch. Those unexpected off-target effects could cause structural rearrangements in the host cell genomes, which may result in oncogenic activation or genomic instability47–50. In addition, the risk of germline transmission is also a challenge to the safety of this strategy. Thus, the risks associated with this new technology must be fully investigated and resolved before its clinical application. Notably, the application of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene therapy is limited due to ineffective targeted delivery. Virus-mediated delivery, such as adeno-associated virus (AAV), has been used to deliver CRISPR/Cas9 in vivo12–16. However, viral vectors may lead to oncogenic effects, toxicity, immunogenicity, and insertional mutagenesis. In addition, due to the low packaging capacity of AAV, viral titers required for therapeutic efficacy are usually several orders of magnitude higher than the acceptable clinical limits. While viral expression systems pose safety concerns for therapeutic application in humans, the existing non-viral formulations (e.g., liposomes or nanoparticles) for delivery of synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs also have shortcomings, such as intolerance, cytotoxicity, poor biocompatibility or stability, off-site delivery, limited cargo-loading capacity, and potential immunogenicity17, 19, 56–58. These challenges limit the use of gRNA/Cas9 technology in clinical applications. Therefore, novel delivery strategies are desperately needed for the delivery of synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs to eradicate chronic HBV infection in vivo.

In summary, this study provides proof-of-concept that synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs can efficiently abolish HBV cccDNA replication and pgRNA/mRNA as well as HBsAg/HBeAg expression in infected cells in vitro. This study, however, has some limitations, such as lacking an evaluation of long-term inhibitory effects on HBV and comprehensive analysis of the gene-editing activity and the host immune responses in vivo. An HBV transgenic mouse model and HBV-infected, liver-humanized mice can offer an excellent opportunity for further evaluation of the antiviral and side effects of our synthetic gRNA/Cas9 RNPs in vivo. Additionally, the development of multiplexed gRNA/Cas9 RNPs using engineered nanoparticles or exosomes for in vivo delivery will facilitate their clinical applications. Despite using combinatorial and repeated treatments with two gRNA/Cas9 RNPs, the maximum reduction in HBV cccDNA achieved by this approach was ~95%, suggesting that complete (100%) elimination of intractable HBV cccDNA is indeed a difficult-to-achieve goal. The identification of low levels of cccDNA in the liver of patients who have spontaneously resolved acute HBV infection indicates that, while complete elimination of intrahepatic cccDNA reservoirs may remain an unreachable goal, immunological control and clinical resolution of HBV infection may yet be possible. Successful treatment of chronic HBV infection may require a combination of drugs with different mechanisms of action against various HBV life cycles and functions. Therefore, a combination of CRISPR/Cas9 RNPs that can substantially reduce HBV cccDNA levels and direct-acting antiviral NA drugs and in conjunction with immunotherapy may eventually cure chronic HBV infection.

Acknowledgment:

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R21AI157909 and R15AG069544 (to Z.Q.Y.); VA Merit Review Awards 2I01BX0002670-06 (to Z.Q.Y) and 5I01BX005428 and NIH S10OD021572 (to J.P.M.); and DoD Award PR170067 (to Z.Q.Y). This publication is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the James H. Quillen Veterans Affairs Medical Center. The contents in this publication do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data Availability Statement:

The datasets generated during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data sharing policies will be followed per the NIH and VA guidelines.

References

- 1.Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, Krause G, Ott JJ. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(10003):1546–55. Epub 2015/08/02. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61412-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ott JJ, Horn J, Krause G, Mikolajczyk RT. Time trends of chronic HBV infection over prior decades - A global analysis. J Hepatol. 2017;66(1):48–54. Epub 2016/09/07. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang YS, Sun HY, Chang SY, Chuang YC, Cheng A, Huang SH, Huang YC, Chen GJ, Lin KY, Su YC, Liu WC, Hung CC. Long-term virological and serologic responses of chronic hepatitis B virus infection to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-containing regimens in patients with HIV and hepatitis B coinfection. Hepatol Int. 2019;13(4):431–9. Epub 2019/06/10. doi: 10.1007/s12072-019-09953-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang T, Su B, Song T, Zhu Z, Xia W, Dai L, Wang W, Zhang T, Wu H. Immunological Efficacy of Tenofovir Disproxil Fumarate-Containing Regimens in Patients With HIV-HBV Coinfection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1023. Epub 2019/10/02. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gish RG, Given BD, Lai CL, Locarnini SA, Lau JY, Lewis DL, Schluep T. Chronic hepatitis B: Virology, natural history, current management and a glimpse at future opportunities. Antiviral Res. 2015;121:47–58. Epub 2015/06/21. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koumbi L Current and future antiviral drug therapies of hepatitis B chronic infection. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(8):1030–40. Epub 2015/06/09. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i8.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dusheiko G Will we need novel combinations to cure HBV infection? Liver Int. 2020;40 Suppl 1:35–42. Epub 2020/02/23. doi: 10.1111/liv.14371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nassal M HBV cccDNA: viral persistence reservoir and key obstacle for a cure of chronic hepatitis B. Gut. 2015;64(12):1972–84. Epub 2015/06/07. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo JT, Guo H. Metabolism and function of hepatitis B virus cccDNA: Implications for the development of cccDNA-targeting antiviral therapeutics. Antiviral Res. 2015;122:91–100. Epub 2015/08/15. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu A, Liao X, Li S, Zhao H, Chen L, Xu M, Duan X. HBV cccDNA and Its Potential as a Therapeutic Target. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2019;7(3):258–62. Epub 2019/10/15. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2018.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maepa MB, Jacobs R, van den Berg F, Arbuthnot P. Recent developments with advancing gene therapy to treat chronic infection with hepatitis B virus. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2020;15(3):200–7. Epub 2020/03/07. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang HC, Chen PJ. The potential and challenges of CRISPR-Cas in eradication of hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA. Virus Res. 2018;244:304–10. Epub 2017/06/20. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kostyusheva AP, Kostyushev DS, Brezgin SA, Zarifyan DN, Volchkova EV, Chulanov VP. [Small Molecular Inhibitors of DNA Double Strand Break Repair Pathways Increase the ANTI-HBV Activity of CRISPR/Cas9]. Mol Biol (Mosk). 2019;53(2):311–23. Epub 2019/05/18. doi: 10.1134/S0026898419010075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kostyushev D, Brezgin S, Kostyusheva A, Zarifyan D, Goptar I, Chulanov V. Orthologous CRISPR/Cas9 systems for specific and efficient degradation of covalently closed circular DNA of hepatitis B virus. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;76(9):1779–94. Epub 2019/01/24. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03021-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H, Sheng C, Wang S, Yang L, Liang Y, Huang Y, Liu H, Li P, Yang C, Yang X, Jia L, Xie J, Wang L, Hao R, Du X, Xu D, Zhou J, Li M, Sun Y, Tong Y, Li Q, Qiu S, Song H. Removal of Integrated Hepatitis B Virus DNA Using CRISPR-Cas9. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:91. Epub 2017/04/07. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, Sheng C, Liu H, Wang S, Zhao J, Yang L, Jia L, Li P, Wang L, Xie J, Xu D, Sun Y, Qiu S, Song H. Inhibition of HBV Expression in HBV Transgenic Mice Using AAV-Delivered CRISPR-SaCas9. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2080. Epub 2018/09/27. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang C, Mei M, Li B, Zhu X, Zu W, Tian Y, Wang Q, Guo Y, Dong Y, Tan X. A non-viral CRISPR/Cas9 delivery system for therapeutically targeting HBV DNA and pcsk9 in vivo. Cell Res. 2017;27(3):440–3. Epub 2017/01/25. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roth TL, Puig-Saus C, Yu R, Shifrut E, Carnevale J, Li PJ, Hiatt J, Saco J, Krystofinski P, Li H, Tobin V, Nguyen DN, Lee MR, Putnam AL, Ferris AL, Chen JW, Schickel JN, Pellerin L, Carmody D, Alkorta-Aranburu G, Del Gaudio D, Matsumoto H, Morell M, Mao Y, Cho M, Quadros RM, Gurumurthy CB, Smith B, Haugwitz M, Hughes SH, Weissman JS, Schumann K, Esensten JH, May AP, Ashworth A, Kupfer GM, Greeley SAW, Bacchetta R, Meffre E, Roncarolo MG, Romberg N, Herold KC, Ribas A, Leonetti MD, Marson A. Reprogramming human T cell function and specificity with non-viral genome targeting. Nature. 2018;559(7714):405–9. Epub 2018/07/12. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0326-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang M, Glass ZA, Xu Q. Non-viral delivery of genome-editing nucleases for gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2017;24(3):144–50. Epub 2016/11/01. doi: 10.1038/gt.2016.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang S, Shen J, Li D, Cheng Y. Strategies in the delivery of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Theranostics. 2021;11(2):614–48. Epub 2021/01/05. doi: 10.7150/thno.47007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai D, Mills C, Yu W, Yan R, Aldrich CE, Saputelli JR, Mason WS, Xu X, Guo JT, Block TM, Cuconati A, Guo H. Identification of disubstituted sulfonamide compounds as specific inhibitors of hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA formation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(8):4277–88. Epub 2012/05/31. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00473-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y, Nie H, Mao R, Mitra B, Cai D, Yan R, Guo JT, Block TM, Mechti N, Guo H. Interferon-inducible ribonuclease ISG20 inhibits hepatitis B virus replication through directly binding to the epsilon stem-loop structure of viral RNA. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(4):e1006296. Epub 2017/04/12. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long Q, Yan R, Hu J, Cai D, Mitra B, Kim ES, Marchetti A, Zhang H, Wang S, Liu Y, Huang A, Guo H. The role of host DNA ligases in hepadnavirus covalently closed circular DNA formation. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(12):e1006784. Epub 2017/12/30. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marchetti AL, Zhang H, Kim ES, Yu X, Jang S, Wang M, Guo H. Proteomic Analysis of Nuclear HBV rcDNA Associated Proteins Identifies UV-DDB as a Host Factor Involved in cccDNA Formation. J Virol. 2021:JVI0136021. Epub 2021/10/28. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01360-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan R, Zhang Y, Cai D, Liu Y, Cuconati A, Guo H. Spinoculation Enhances HBV Infection in NTCP-Reconstituted Hepatocytes. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129889. Epub 2015/06/13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marchetti M, Zermatten MG, Bertaggia Calderara D, Aliotta A, Alberio L. Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia: A Review of New Concepts in Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management. J Clin Med. 2021;10(4). Epub 2021/02/14. doi: 10.3390/jcm10040683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Croagh CM, Desmond PV, Bell SJ. Genotypes and viral variants in chronic hepatitis B: A review of epidemiology and clinical relevance. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(3):289–303. Epub 2015/04/08. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sells MA, Chen ML, Acs G. Production of hepatitis B virus particles in Hep G2 cells transfected with cloned hepatitis B virus DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84(4):1005–9. Epub 1987/02/01. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.4.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan H, Zhong G, Xu G, He W, Jing Z, Gao Z, Huang Y, Qi Y, Peng B, Wang H, Fu L, Song M, Chen P, Gao W, Ren B, Sun Y, Cai T, Feng X, Sui J, Li W. Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is a functional receptor for human hepatitis B and D virus. Elife. 2012;1:e00049. Epub 2012/11/15. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tong S, Li J. Identification of NTCP as an HBV receptor: the beginning of the end or the end of the beginning? Gastroenterology. 2014;146(4):902–5. Epub 2014/03/01. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bibikova M, Carroll D, Segal DJ, Trautman JK, Smith J, Kim YG, Chandrasegaran S. Stimulation of homologous recombination through targeted cleavage by chimeric nucleases. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(1):289–97. Epub 2000/12/13. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.1.289-297.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo H, Jiang D, Zhou T, Cuconati A, Block TM, Guo JT. Characterization of the intracellular deproteinized relaxed circular DNA of hepatitis B virus: an intermediate of covalently closed circular DNA formation. J Virol. 2007;81(22):12472–84. Epub 2007/09/07. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01123-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai D, Wang X, Yan R, Mao R, Liu Y, Ji C, Cuconati A, Guo H. Establishment of an inducible HBV stable cell line that expresses cccDNA-dependent epitope-tagged HBeAg for screening of cccDNA modulators. Antiviral Res. 2016;132:26–37. Epub 2016/05/18. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seeger C, Sohn JA. Targeting Hepatitis B Virus With CRISPR/Cas9. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2014;3:e216. Epub 2014/12/17. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2014.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kennedy EM, Bassit LC, Mueller H, Kornepati AVR, Bogerd HP, Nie T, Chatterjee P, Javanbakht H, Schinazi RF, Cullen BR. Suppression of hepatitis B virus DNA accumulation in chronically infected cells using a bacterial CRISPR/Cas RNA-guided DNA endonuclease. Virology. 2015;476:196–205. Epub 2015/01/02. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinez MG, Combe E, Inchauspe A, Mangeot PE, Delberghe E, Chapus F, Neveu G, Alam A, Carter K, Testoni B, Zoulim F. CRISPR-Cas9 Targeting of Hepatitis B Virus Covalently Closed Circular DNA Generates Transcriptionally Active Episomal Variants. mBio. 2022;13(2):e0288821. Epub 2022/04/08. doi: 10.1128/mbio.02888-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhen S, Hua L, Liu YH, Gao LC, Fu J, Wan DY, Dong LH, Song HF, Gao X. Harnessing the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated Cas9 system to disrupt the hepatitis B virus. Gene Ther. 2015;22(5):404–12. Epub 2015/02/06. doi: 10.1038/gt.2015.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seeger C, Sohn JA. Complete Spectrum of CRISPR/Cas9-induced Mutations on HBV cccDNA. Mol Ther. 2016;24(7):1258–66. Epub 2016/05/21. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dong C, Qu L, Wang H, Wei L, Dong Y, Xiong S. Targeting hepatitis B virus cccDNA by CRISPR/Cas9 nuclease efficiently inhibits viral replication. Antiviral Res. 2015;118:110–7. Epub 2015/04/07. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu C, Zhou W, Wang Y, Qiao L. Hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2014;345(2):216–22. Epub 2013/08/29. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tarocchi M, Polvani S, Marroncini G, Galli A. Molecular mechanism of hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocarcinogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(33):11630–40. Epub 2014/09/11. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i33.11630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sung WK, Zheng H, Li S, Chen R, Liu X, Li Y, Lee NP, Lee WH, Ariyaratne PN, Tennakoon C, Mulawadi FH, Wong KF, Liu AM, Poon RT, Fan ST, Chan KL, Gong Z, Hu Y, Lin Z, Wang G, Zhang Q, Barber TD, Chou WC, Aggarwal A, Hao K, Zhou W, Zhang C, Hardwick J, Buser C, Xu J, Kan Z, Dai H, Mao M, Reinhard C, Wang J, Luk JM. Genome-wide survey of recurrent HBV integration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44(7):765–9. Epub 2012/05/29. doi: 10.1038/ng.2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang Z, Jhunjhunwala S, Liu J, Haverty PM, Kennemer MI, Guan Y, Lee W, Carnevali P, Stinson J, Johnson S, Diao J, Yeung S, Jubb A, Ye W, Wu TD, Kapadia SB, de Sauvage FJ, Gentleman RC, Stern HM, Seshagiri S, Pant KP, Modrusan Z, Ballinger DG, Zhang Z. The effects of hepatitis B virus integration into the genomes of hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Genome Res. 2012;22(4):593–601. Epub 2012/01/24. doi: 10.1101/gr.133926.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hai H, Tamori A, Kawada N. Role of hepatitis B virus DNA integration in human hepatocarcinogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(20):6236–43. Epub 2014/05/31. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i20.6236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feitelson MA, Lee J. Hepatitis B virus integration, fragile sites, and hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2007;252(2):157–70. Epub 2006/12/26. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zoulim F, Locarnini S. Hepatitis B virus resistance to nucleos(t)ide analogues. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(5):1593–608 e1–2. Epub 2009/09/10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O’Geen H, Henry IM, Bhakta MS, Meckler JF, Segal DJ. A genome-wide analysis of Cas9 binding specificity using ChIP-seq and targeted sequence capture. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(6):3389–404. Epub 2015/02/26. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morgens DW, Wainberg M, Boyle EA, Ursu O, Araya CL, Tsui CK, Haney MS, Hess GT, Han K, Jeng EE, Li A, Snyder MP, Greenleaf WJ, Kundaje A, Bassik MC. Genome-scale measurement of off-target activity using Cas9 toxicity in high-throughput screens. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15178. Epub 2017/05/06. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cameron P, Fuller CK, Donohoue PD, Jones BN, Thompson MS, Carter MM, Gradia S, Vidal B, Garner E, Slorach EM, Lau E, Banh LM, Lied AM, Edwards LS, Settle AH, Capurso D, Llaca V, Deschamps S, Cigan M, Young JK, May AP. Mapping the genomic landscape of CRISPR-Cas9 cleavage. Nat Methods. 2017;14(6):600–6. Epub 2017/05/02. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koo T, Lee J, Kim JS. Measuring and Reducing Off-Target Activities of Programmable Nucleases Including CRISPR-Cas9. Mol Cells. 2015;38(6):475–81. Epub 2015/05/20. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2015.0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilbie D, Walther J, Mastrobattista E. Delivery Aspects of CRISPR/Cas for in Vivo Genome Editing. Acc Chem Res. 2019;52(6):1555–64. Epub 2019/05/18. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yin H, Kauffman KJ, Anderson DG. Delivery technologies for genome editing. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(6):387–99. Epub 2017/03/25. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.You L, Tong R, Li M, Liu Y, Xue J, Lu Y. Advancements and Obstacles of CRISPR-Cas9 Technology in Translational Research. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2019;13:359–70. Epub 2019/04/17. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2019.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Louis Jeune V, Joergensen JA, Hajjar RJ, Weber T. Pre-existing anti-adeno-associated virus antibodies as a challenge in AAV gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther Methods. 2013;24(2):59–67. Epub 2013/02/28. doi: 10.1089/hgtb.2012.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rapti K, Louis-Jeune V, Kohlbrenner E, Ishikawa K, Ladage D, Zolotukhin S, Hajjar RJ, Weber T. Neutralizing antibodies against AAV serotypes 1, 2, 6, and 9 in sera of commonly used animal models. Mol Ther. 2012;20(1):73–83. Epub 2011/09/15. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nguyen DN, Roth TL, Li PJ, Chen PA, Apathy R, Mamedov MR, Vo LT, Tobin VR, Goodman D, Shifrut E, Bluestone JA, Puck JM, Szoka FC, Marson A. Polymer-stabilized Cas9 nanoparticles and modified repair templates increase genome editing efficiency. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38(1):44–9. Epub 2019/12/11. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0325-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wessel EM, Tomich JM, Todd RB. Biodegradable Drug-Delivery Peptide Nanocapsules. ACS Omega. 2019;4(22):20059–63. Epub 2019/12/04. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.9b03245. stockholder in the firm Phoreus Biotechnology that has licensed the IP developed by Professor Tomich at Kansas State University. All of the research for this project was carried out in a non-affiliated laboratory. EMW and RBT have no conflicts to declare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen G, Abdeen AA, Wang Y, Shahi PK, Robertson S, Xie R, Suzuki M, Pattnaik BR, Saha K, Gong S. A biodegradable nanocapsule delivers a Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex for in vivo genome editing. Nat Nanotechnol. 2019;14(10):974–80. Epub 2019/09/11. doi: 10.1038/s41565-019-0539-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data sharing policies will be followed per the NIH and VA guidelines.