Abstract

Fibrosis is primarily described as the deposition of excessive extracellular matrix, but in many tissues it also involves a loss of lipid or lipid-filled cells. Lipid filled cells are critical to tissue function and integrity in many tissues including the skin and lungs. Thus, loss or depletion of lipid filled cells during fibrogenesis, has implications for tissue function. In some contexts, lipid-filled cells can impact ECM composition and stability, highlighting their importance in fibrotic transformation. Recent papers in fibrosis address this newly recognized fibrotic lipodystrophy phenomenon. Even in disparate tissues, common mechanisms are emerging to explain fibrotic lipodystrophy. These findings have implications for fibrosis in tissues composed of fibroblast and lipid-filled cell populations such as skin, lung, and liver. In this review, we will discuss the roles of lipid-containing cells, their reduction/loss during fibrotic transformation, and the mechanisms of that loss in the skin and lungs.

Keywords: Lipodystrophy, dermal adipocytes, skin fibrosis, Wnt signaling

Introduction:

In the context of fibrosis, several tissues including skin, liver, and lung exhibit loss of lipid filled cells or lipodystrophy1-7. Emerging evidence demonstrates that factors originating from lipid-filled cells are fibroprotective in tissues and their acute loss in fibrotic transformation contributes to tissue dysfunction8-12. As such, understanding the mechanisms and implications of fibrotic lipodystrophy is critical when considering therapeutic strategies in fibrosis. Lipid-filled cells include, but are not limited to adipocytes in white adipose tissue. Lipid-filled cells that occur naturally or arise as a result of disease in non-adipose tissues will also be discussed13. Despite not being classified as adipocytes, these cells may in fact be capable of undergoing various lipid handling processes normally associated with white adipocytes, thus it is useful to begin by outlining the structure and function of adipose tissue, and review lipid handling processes which occur in adipocytes. We will then discuss the importance of lipid-filled cells in skin and lung and outline the evidence for their reduction in fibrosis. Finally, we will examine evidence for the dysregulation of lipid handling processes in fibrotic lipodystrophy and its implications for tissue function.

BASIC STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF ADIPOSE TISSUE

White adipose tissue, one of the largest lipid storage and endocrine organs in the body, is known to have a complex structure and function14. It is associated with diverse tissues such as the skin, muscle, intestines, and the heart among others15. This fatty, connective, adipose tissue consists of adipocytes, stromal cells, macrophages, mural cells, fibroblasts, and pericytes16,17, creating a diverse array of cell-cell interactions18. The primary purpose of adipose tissue is storage of neutral fatty acids that can be metabolized as needed for energy19. Additionally, the adipose tissue can release a variety of adipokines, such as adiponectin and leptin, acting as a paracrine, endocrine, or autocrine organ20. In order to achieve these numerous functions, adipocytes have dynamic homeostatic and stimulated mechanisms to handle lipid. The discovery of new lipid handling mechanisms in adipose tissue and techniques to detect changes in lipid handling are key to better understanding changes in lipid-filled cells in disease states. The conserved and tissue-specific roles of lipid-filled cells are disrupted upon stimulated lipid depletion in tissue fibrosis which will be discussed in more detail in this review.

LIPID HANDLING PROCESSES

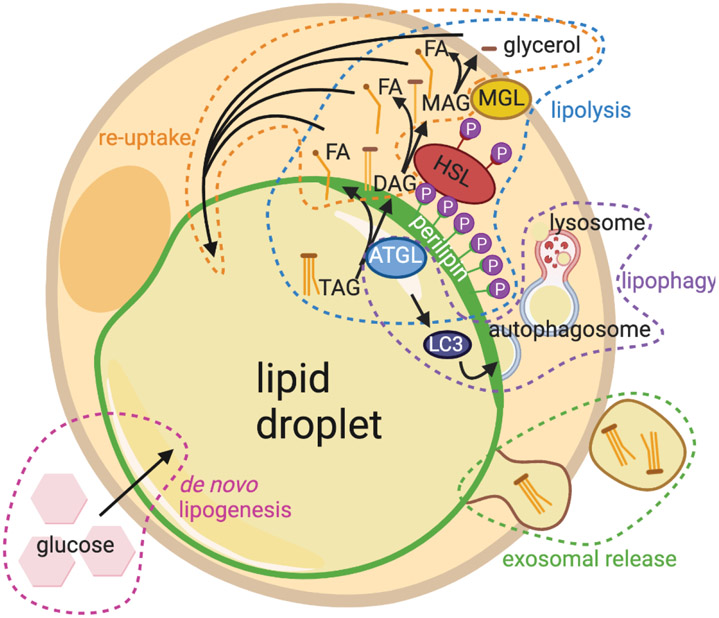

Lipid handling is a tightly controlled process within adipocytes 21. While stored lipids are constantly being broken down as needed for energy, intercellular communication, and structural components of cells, they are also being replenished to maintain the lipid-laden state of the cell22. The processes by which adipocytes modulate their lipid content are detailed below (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Lipid handling involves lipid breakdown and accumulation.

Breakdown processes include lipolysis, lipophagy, and exosomal release. Lipid accumulation can occur by de novo lipogenesis or by re-uptake of fatty acids and glycerol.

The homeostatic functioning of systemic adipose tissue prevents the development of metabolic disorders. Classically, a major role of lipid handling in adipose tissue depots is the storage or release of energy in the form of lipids depending on nutrient availability23. The lipid content within adipose tissue is homeostatically maintained by balancing lipid accumulation and lipid breakdown. In periods of high nutrient availability, energy is stored within adipocytes as triacylglycerols (TAGs). These stored lipids can be broken down and the products mobilized in periods of low nutrient availability. Subject to complex hormonal and metabolic regulation, dietary fatty acids (FAs) can be taken up by adipocytes and esterified into TAGs (lipogenesis), or de novo TAGs can be synthesized from malonyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA during times of caloric excess (de novo lipogenesis)20. Under conditions like fasting, adipocytes break up their stored TAGs into constituent FAs (lipolysis) and release them into circulation thus, supplying energy-hungry peripheral tissues with FAs20. Throughout their homeostatic functions and in states of stimulated lipid metabolism, adipocytes produce numerous factors, called adipokines which influence the function of both local and distant tissues in the body24-26. The specific roles of some of the adipose-derived factors will be discussed in relevant tissues throughout this review. For more extensive review of lipid handling processes see other reviews23,27.

Lipid Uptake: De novo Lipogenesis and Re-esterification

Before we review the processes that contribute to lypodystrophy associated with the fibrotic state, we provide a brief introduction to the dynamic lipid accumulation pathways that are active during tissue homeostasis. De novo lipogenesis is the uptake of glucose and its conversion to TAG for energy storage28. After caloric intake, the citric acid cycle stops and energy is diverted towards fatty acid anabolism. Here, citrate is converted to fatty acids depending on the availability of acetyl-CoA28-30. Adipocytes may also, or instead, accumulate lipid by re-esterification. In this process, glucose first enters adipocytes via the GLUT-4 receptor31. A series of enzymes convert glucose into glycerol-3-phosphate, which is then bound to free fatty acids (FFAs) that have been synthesized or taken from the surroundings of the adipocyte30. Though these processes are relevant to lipid homeostasis in tissue, since lypodystrophy occurs in the fibrotic state, most research has focused on stimulants of aberrant lipid depletion which will be discussed in greater detail below.

LIPID DEPLETION:

Lipid depletion via lipolysis

The breakdown of stored lipids via the lipolysis pathway is a well-characterized lipid handling process, which occurs homeostatically (basal lipolysis), but may also be stimulated (stimulated lipolysis). Aberrant lipolysis is implicated in various diseases including diabetes, cancer, and liver disease23,32-35. In lipolysis, a series of lipases consecutively remove fatty acid chains from triacylglycerides (TAGs) in the lipid droplet, resulting in the release of glycerol and fatty acids. The key players in lipolysis are reviewed in detailed elsewhere27,36. Briefly, the first step in the lipolysis pathway involves recruitment of Adipose Triglyceride Lipase (ATGL) to the lipid droplet as a result of phosphorylation of the perilipin vesicular protein37. ATGL enzymatically cleaves one fatty acid chain from TAG resulting in diacylglycerol (DAG)38. The Zechner lab showed that inhibition or genetic ablation of ATGL in adipocytes prevents the majority of lipolysis in isolated adipocytes38,39. Phosphorylation of Hormone Sensitive Lipase (HSL) by ATGL allows it to remove a second fatty acid chain from DAG resulting in monoacylglycerol (MAG) as evidenced by DAG accumulation in HSL-deficient mice40,41,42. MAG is then further cleaved of its last fatty acid chain by monoacylglycerol lipase (MGL), releasing the leftover glycerol and a total of three free fatty acid (FFA) chains to the extracellular environment or to the β-oxidation cycle43. As a result, MGL depletion leads to MAG accumulation in mouse adipose tissue as well as other sites44. While the stimuli may differ between basal and stimulated lipolysis, several core lipases are conserved between the two processes including ATGL, making targeting lipolysis in disease challenging27. The key lipolytic players highlighted in these and other papers enable investigation into the involvement in lipolysis in both the aforementioned tissue diseases and in homeostasis.

Lipid depletion via lipophagy

Lipophagy is the autophagic breakdown of the lipid droplet by the lysosome, which is not only indispensable for cellular lipid metabolism, but also occurs in response to nutrient deprivation45,46. In this conserved catabolic process, a series of autophagy-associated proteins (Atg5, Atg7, Atg12) and adaptor protein microtubule-associated light chain 3 (LC3) assemble to form an autophagosome at an intracellular lipid droplet membrane to facilitate the trafficking of lipid to lysosomes and its subsequent degradation45,47. The autophagosome then uses lysosomal proteins to break down the lipid within the droplet into FFA48. After breakdown of lipids by lipophagy, some FFA are expelled from the cell via lysosomal exocytosis, in which a lysosomal vesicle fuses with the plasma membrane, dispensing the FFA to the extracellular space49. This was first demonstrated in the liver, where knockout of autophagy gene Atg5 caused accumulation of TAG in cells and reduced lipid breakdown in response to known lipolytic stimuli45. Similar to lipolysis, lipophagy is also initiated by ATGL, such that knock down of Atgl has been reported to result in reduced expression of key lipophagy-related genes in vivo and its chemical inhibition causes comparable changes in vitro50. Additionally, some types of lipophagy modify PLIN proteins on lipid droplet membranes to mediate ATGL recruitment, initiating lipolysis51. This suggests crosstalk between lipolysis and lipophagy pathways48 (Fig. 1).

Adipocyte Exosomes: a new way for lipid depletion.

An emerging way to expel lipids and adipokines is to generate extracellular vesicles such as exosomes by adipocytes (AdExos). AdExos are small vesicles produced from adipocytes via an endocytic pathway. These exosomes are known to have originated from adipocytes due to previous characterization as a lipid droplet containing neutral lipids carrying the adipocyte marker Perilipin 1 (PLIN1), surrounded by a phospholipid bilayer carrying tetraspanins such as CD6352. In addition to carrying neutral lipids, AdExos and other extracellular vesicles also carry a variety of adipokines including MIF, TNFα, MCSF, and RBP-4, which, when taken up by other cells, may induce different responses53. Recent studies have shown that AdExos play important roles in the differentiation of adipose tissue macrophages, making them multinucleated, accumulating fat, and increasing lysosomal content52. AdExos can form in the absence of ATGL gene function, suggesting this is an ATGL-independent mechanism for lipid depletion. The role of AdExos-mediated cross talk between adipocytes and fibroblasts remains to be rigorously tested in the context of tissue fibrosis.

Dermal adipose tissue and its dysregulation in skin fibrosis

Function of Dermal White Adipose Tissue

Next, we focus on the role of dermal white adipose tissue (DWAT) during homeostatic conditions, its dynamic changes during normal hair follicle cycling, and the emerging mechanisms of DWAT lipodystrophy in skin fibrosis. DWAT, underlies the ECM-rich dermal fibroblast layer, and predominantly contains mature dermal adipocytes. The field of DWAT research has been expanding rapidly over the last few years since dermal adipose tissue has been recognized as a distinct secondary adipose tissue depot, with divergent functions from visceral white adipose tissue54-56. In the skin, DWAT plays a role in immune defense57, thermoregulation58, vascularization7, hair follicle cycling59,60, and wound healing7.

In mice, a distinct layer of DWAT, is apparent in the dermis, separated from subcutaneous white adipose tissue (SWAT) by the panniculus carnosus muscle layer61. Until recently, the distinction between the dermal and subcutaneous adipose tissue was not appreciated in humans, but Wojciechowicz and colleagues drew attention to the differences between the two depots in 201362. Driskell and colleagues first used the term DWAT to describe the portion of the dermal fat immediately adjacent to the dermis in mice and humans56. Even though they were recognized as metabolically distinct compartments, the DWAT and SWAT depots in humans were previously called the subcutaneous adipose tissue and deep subcutaneous adipose tissue, respectively63. The recent distinction of DWAT as a unique depot from SWAT, however, complicates the interpretation of earlier studies of adipose tissues in skin diseases.

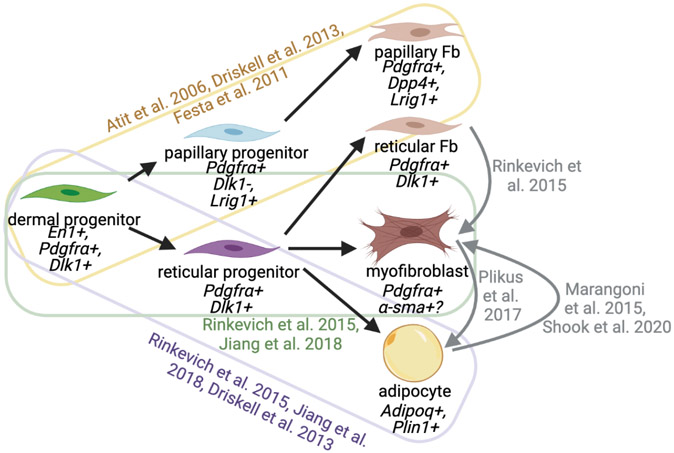

In addition to being anatomically distinct in mice, the adipocytes that comprise DWAT have different origins than SWAT adipocytes, arising from a common dermal fibroblast-adipocyte progenitor during embryonic development56,64,65(Fig. 2). In the dorsal dermis, fibro-adipo progenitors emerge from the somites66,67. They undergo differentiation based on exposure to cues such as Wnt signaling67-69. Lineage-tracing experiments show that dermal adipocytes are derivatives of En1, Pdgfrα and Dlk1 expressing cells65,70-73. Recent in vitro studies suggest Wnt activation causes adipocytes derived from dermal progenitors to become depleted of lipid and acquire α-SMA positivity suggesting that these cells are plastic and capable of lineage conversion 74,75.

Figure 2: Dermal progenitors give rise to various dermal populations, though those dermal populations in adult tissue are plastic.

Black lines indicate differentiation trajectory of cell populations under control conditions; associated references in color. Gray lines and references indicate platicity of mature dermal polulations.

The dermal adipocytes’ ability to carry out their many functions are dependent on the quantity of their lipid content and their ability to mobilize that lipid24,76. Mature adipocytes take up lipid either by de novo lipogenesis or by re-uptake of extracellular neutral lipid77. Conversely, they breakdown lipid by lipolysis or lipophagy, or they release intact lipid by exosomal release27,37,51,52 (Fig. 2). Lipid breakdown, and particularly lipolysis, occurs homeostatically in the skin resulting in the release of fatty acids and adipokines that impact the identity and behavior of neighboring cells8,78.

Immune cells are among the cells impacted by adipocyte-derived signals. Dermal adipocytes uniquely display an inflammatory gene expression signature homeostatically79. During a bacterial infection, dermal adipocytes increase in size and number and release inflammatory peptides including Cathelicidin57. Similarly, in response to skin injury, mature adipocytes release fatty acids via lipolysis to stimulate immune cell recruitment. Subsequently, they differentiate into α-SMA expressing and ECM-producing myofibroblasts themselves7. Dermal adipocytes are also known to release a suite of secreted factors, including fatty acids and adipokines, that regulate dermal fibroblasts and their production of extracellular matrix8,10,80. In disease states in which adipocyte secretion profile is affected, the roles of adipocytes become increasingly clear. Altogether, the dermal adipose tissue serves numerous critical functions, prompting recent investigation into its dysfunction in disease states such as dermal fibrosis (discussed below).

Skin-specific roles of lipid-filled cells- modulation of hair cycling

Before we review changes in DWAT during acute and chronic skin fibrosis, we briefly want to acknowledge the dynamic change in the size of the DWAT layer during hair cycling in mouse skin as a model for homeostatic DWAT layer regression and expansion (also reviewed extensively elsewhere60. Unlike other adipose depots, the DWAT is adjacent to hair follicles in the dermis creating a unique signaling environment. Dermal adipose tissue impacts, and is impacted by, hair cycling81,82. Concurrent with the phases of the hair cycle, the DWAT is known to dramatically expand during anagen and regress through catagen and telogen79,81-83. The coupling of the hair cycle and DWAT flux results from complex crosstalk that converges on shared pathways including BMP, Hedgehog, and Wnt signaling60. DWAT expansion occurs through both adipocyte hypertrophy and hyperplasia during anagen in response to growth factor signals from hair follicles60,81,82. DWAT layer regression occurs dramatically during catagen and telogen; however, this does not occur via apoptosis82,62. Zhang and colleagues profiled dermal adipocytes during hair cycling and concluded that DWAT layer volume reduction corresponds in part to decreasing lipid content resulting from a lipogenesis-to-lipolysis switch that occurs in the anagen-to-catagen transition, though the dependence of DWAT lipid reduction on lipolysis has yet to be demonstrated functionally79,84. Lipophagy has also been hypothesized to work with stimulated lipolysis to account for the decrease in adipocyte size beginning in catagen84. The cyclical nature of dermal adipose tissue in its association with hair cycling points to important tissue-specific roles of dermal adipose tissue that should be examined in the context of skin fibrosis. Hair loss is a symptom of scarring and chronic fibrosis. Understanding the changes in adipocyte biology that accompany fibrotic skin disease will inform research in this aspect of fibrosis and wound healing85-87. Additionally, by examining the dynamic changes in dermal adipose tissue associated with hair cycling and the impact of those adipose tissue changes on the neighboring dermis, we may better understand the ways in which fibrotic fat loss impacts dermal architecture.

Skin Tissue Fibrosis-associated lipodystrophy

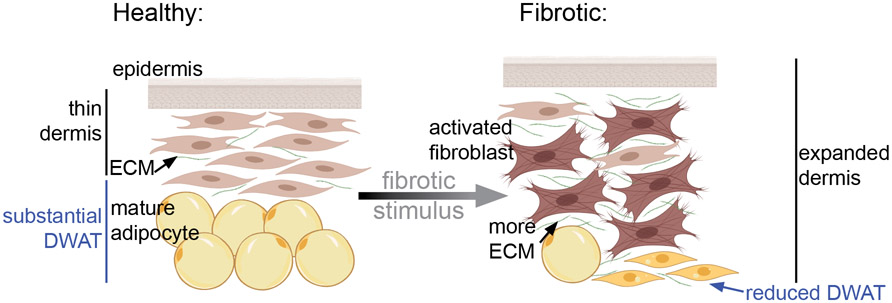

Next, we will discuss recent findings regarding the involvement of dermal fat in skin fibrosis. Dermal fibrosis encompasses a wide variety of skin diseases including keloids and hypertrophic scars, caused by acute skin injury, as well as diseases like scleroderma and psoriasis, caused by chronic immune or environmental insults88. They are characterized by excess deposition of extracellular matrix in addition to an early loss of dermal fat83,89 (Fig. 3). Transcriptional profiling of skin from limited and systemic scleroderma patients showed that that fatty acid metabolism was differentially down-regulated in SSc 90. The causes and consequences of fibrosis-associated lipodystrophy in the skin are only beginning to be understood. We will review the literature regarding fibrotic fat loss in skin and its mouse models in vivo. We will include mouse models of both acute and chronic fibrosis because there are some similarities and some differences between them (Table 1)91. Acute skin fibrosis occurs during wound healing and chronic fibrosis occurs in the context of ongoing disease states. Wound healing and chronic fibrosis differ in their stimuli and dynamics92. Importantly, both classes of fibrotic disease have in common an ultimate loss of DWAT, but how that lipodystrophy occurs is dependent on the stimulus.

Figure 3: Schematic of fibrotic changes in the skin.

Skin fibrosis includes dermal expansion, fibroblast activation, ECM accumulation and reduced DWAT volume due to reduced lipid in individual adipocytes.

Table 1:

Summary of studies in fibrosis that impact DWAT and mechanism

| Reference: | Acute/ chronic: |

Stimulus: | Effect on dermal fat | Proposed mechanism: |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 59 | Acute | Wound | Early DWAT expansion | PPARγ-mediated adipogenesis |

| 7 | Acute | Wound | Early DWAT expansion, later regression | ATGL-mediated lipid loss followed by myofibroblast conversion |

| 110 | Acute | 21d bleomycin | Reduced adipose tissue | Fizz1-dependent |

| 75 | Chronic | 10-21d conditional Wnt activation in adult | Reduced DWAT, reversible | Dpp4-dependent |

| 89 | Chronic | 14d Bleomycin | Dermal adipocyte transdifferentiation into myofibroblast | TGFβ-dependent |

| 113 | Chronic | 28d Bleomycin | DWAT reduction | PPARγ-mediated adipogenesis |

| 136 | Chronic | Constitutive Wnt activation | Lack of DWAT in Wnt activated | Adipogenesis defect |

Loss of dWAT in acute fibrosis/wound healing:

Physical or chemical insult to the skin causes an early, robust, and geographically concentrated immune response93. One interesting phenomenon that has been observed in wound healing, but not chronic skin fibrosis is an initial expansion of dermal adipose tissue59. Dermal adipocytes are key players in the early stages of injury-induced immune activation. In bacterial infection, adipocyte precursors undergo differentiation into adipocytes, which then stimulate an immune response57. During the early inflammatory stage of wound healing, new adipocytes emerge from Engrailed (En1) lineage cells65. Shook et al. showed that adipocytes at the wound site expand, and later are reduced in size due to ATGL-dependent lipolysis and that the products of lipid breakdown recruit immune cells and are required for efficient wound closure7. ATGL is also involved in lipophagy, which is not explicitly ruled out in these studies50. After lipodystrophy, some lineage marked dermal adipocytes assume a myofibroblast identity7. This trans-differentiation from lipid-filled mature dermal adipocyte to activated myofibroblast means that not only are the potentially fibro-protective effects of adipocytes negated, but the population of cells contributing to fibrotic extracellular matrix remodeling expands. Thus, understanding the mediators of this conversion and preventing it, can open new therapeutic avenues.

The plasticity of dermal populations is a key aspect of fibrosis onset, but perhaps it might also be leveraged in treatment. In fact, Plikus and colleagues had previously shown that myofibroblasts can be induced to become adipocytes during wound healing, but only in the presence of factors secreted from hair follicles, which are typically absent in human wound beds94. Indeed, others have shown that hair cycle affects dermal ECM deposition and rate of wound closure in mammalian skin95,96. This may in part be due to hair cycle-associated DWAT differences, as adipocytes in the skin have been shown to recruit fibroblasts necessary for wound healing and impact their ECM deposition8,59. These studies illustrate the need to consider the cyclical nature of the DWAT in wounding models and its relationship to skin appendages including hair follicles.

Depletion of dWAT in chronic fibrosis models:

Chronic fibrosis in humans also involves dermal fat loss, though it is not known if the lypodystrophy is due to an acute lipolytic event54,108. This fat loss is recapitulated in animal models including TGF-beta activation models, Wnt activation models, and bleomycin-induced chemical models though it has been investigated in some models more thoroughly than in others75,89,109,110.

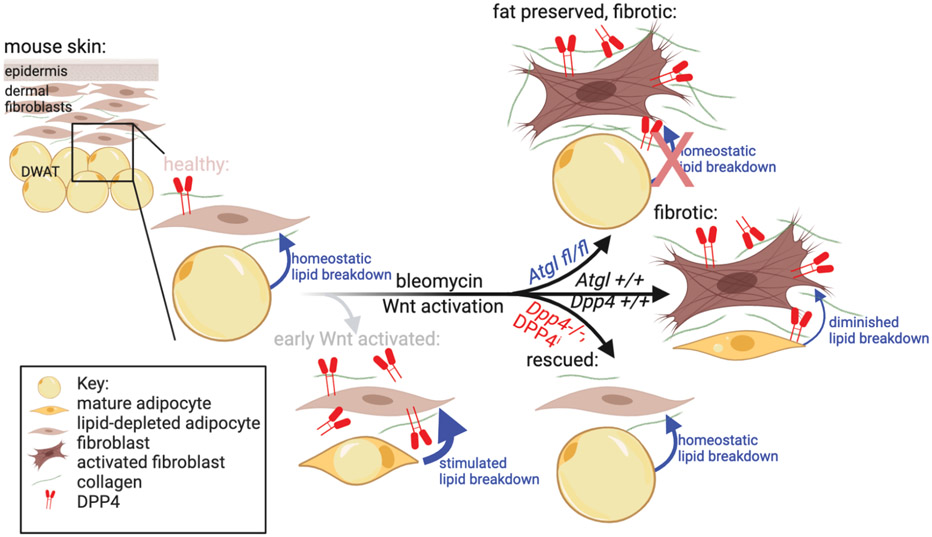

Mice treated with subcutaneous bleomycin injection in the dorsal skin for only five days (which is still a fairly acute and concentrated fibrotic stimulus) exhibit profound loss of intradermal fat accompanied by excessive lipid breakdown111. An initial expansion of adipose tissue has not been reported in chronic fibrosis models as it has in wound healing and bacterial infection models. As in wound healing contexts, however, adipocyte lipid depletion occurs and is dependent on ATGL, consistent with increased lipolysis111. In a short-term bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis, inhibition of that adipocyte lipolysis has been reported to cause precocious dermal thickening, suggesting that induced dermal adipocyte lipolysis plays a fibro-protective role by reducing or delaying ECM accumulation in the context of short-term bleomycin-induced fibrosis111 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Dermal Wnt activation and bleomycin challenge stimulate ATGL-dependent lipid breakdown.

Atgl fl/fl mice retain DWAT lipid despite bleomycin challenge, though have greater dermal thickening. Stimulated lipid breakdown precedes collagen remodeling in Wnt-induced fibrosis. DPP4 is increased in both Wnt activated and bleomycin-challenged mouse skin. Dpp4 −/− mice are protected from stimulated lipid breakdown, and collagen remodeling.

Other skin fibrosis models rely on longer term, more dilute bleomycin treatment. In one such model, after 14 days of subcutaneous bleomycin treatment Marangoni and colleagues observed intradermal fat loss and trans-differentiation of a small subpopulation of adipocytes into myofibroblasts112. Sustained bleomycin subcutaneous injections for 28 days also result in dramatic DWAT loss and reduced expression of Ppar−γ, a critical gene to adipocyte differentiation and glucose metabolism113,114. Ppar-γ agonism leads to reduced fibrosis including attenuated DWAT loss113. This suggests that reduced lipid uptake is involved in maintenance of lipodystrophy. These data were corroborated by Martins et al. who further identified Fizz1 as a critical player in adipocyte to myofibroblast trans-differentiation110. These findings are relevant to human skin fibrosis as fibrotic skin also displays a marked reduction in PPAR-γ/FAO gene expression as well115.

Wnt signaling is elevated across fibrotic diseases in humans including in skin fibrosis, as well as in most murine models including the bleomycin and TGF-β activation models of skin fibrosis100,101,101-109. The Wnt signaling pathway is a good candidate to investigate in fibrosis associated lipodystrophy, because it is involved in fibroblast/adipocyte cell fate commitment126-128. Wnt activation drives fibro/adipo-progenitor cells to become fibroblasts over adipocytes, and its upregulation activates fibroblasts to form myofibroblasts across fibrotic diseases of different organs124,129-133. Overexpression of a canonical Wnt ligand, Wnt 10b, in adipocyte progenitor populations in adult mouse skin leads to reduction in adipocyte number and causes dermal thickening and pro-fibrotic gene expression134. The authors propose that this is the result of reduced adipogenesis, but didn’t rule out an effect of Wnt on mature adipocytes. In fact, mature dermal adipocytes are a highly plastic population of cells79. As in acute fibrosis, the loss of adipocyte identity has implications for adipocyte function and particularly for their interaction with other dermal cells. Wnt activation by stabilization of its primary effector, β-catenin, in various fibroblast and fibroblast/adipocyte lineages during skin development has been shown to cause fibrosis including fibrotic fat loss135,136. Many have demonstrated that Wnt activation in various dermal lineages during the development of DWAT leads to reduced dermal fat, largely due to reduced adipogenesis136-138. These models highlight the involvement of Wnt activation in dermal fibro-adipo progenitor cell fate decisions. In order to understand how the dysregulation of Wnt signaling causes fibrotic fat loss in mature dermal adipocytes, we need to develop and rigorously test new genetic models in vivo.

Our group recently developed an inducible and de-inducible model of Wnt signaling activation in the En1-derived lineage in mouse skin in vivo to test if DWAT loss is dependent on sustained dermal Wnt signaling. Upon Wnt activation, we found DWAT depletion precedes ECM expansion in the dermis, suggesting adipocyte lipid handling may regulate matrix remodeling. Additionally, de-inducing Wnt signaling activation in this model allows for the dynamic re-emergence of the DWAT, before the ECM expansion is ameliorated. The mechanism underlying the DWAT re-emergence remains to be determined75. These results are consistent and support the short term Wnt signaling inhibition trials on human forearm skin that show an emergence of an adipocyte signature139. In addition, they indicate that in the absence of other fibrotic stimuli, the return of the skin to control levels of Wnt signaling is sufficient to allow reversal of skin fibrosis and associated lipodystrophy in mice. As a result, Wnt signaling and its effectors represent potentially effective targets for fibrosis therapy (Fig. 4).

Visible and dynamic DWAT reduction in Wnt activated skin is preceded by an increase in the expression of activated lipolytic proteins111. In cultured adipocytes derived from dermal progenitors, treatment with a Wnt agonist leads to elevated glycerol release and is partially protected with ATGL inhibitor, indicative of a role for lipid breakdown111. These data however do not reveal how Wnt activation stimulates lipid breakdown and future studies should focus on the mechanism of Wnt stimulation of lipolysis and/or lipophagy. Additionally, though the early remodeling of the DWAT suggests matrix remodeling is impacted by fibrotic fat loss, the necessity of lipodystrophy for Wnt induced fibrotic remodeling will require rigorous testing in vivo using inducible Cre lines restricted to mature dermal adipocytes with genetic lineage tracing.

We also used the Wnt inducible/de-inducible mouse model to identify and functionally validate Wnt-dependent target genes. We found Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) as a robust downstream mediator of Wnt-induced fibrotic lipid depletion and ECM remodeling in mouse skin in vivo75. DPP4 has recently emerged as a protein if particular interest in skin wound healing and fibrosis owing to its diverse roles in fibroblast ECM production, re-epithelialization, and immune activation140,141. DPP4 expression distinguishes primary collagen producing fibroblasts from other fibroblast subpopulations in skin wound healing142,143. DPP4 is known to impact lipid handling in other contexts and has been implicated in fibrotic remodeling of the skin and other tissues though has not previously been implicated in fibrotic lipodystrophy71,144-152. Wnt activation in a Dpp4−/− background in vivo lead to a rescue of ECM accumulation, lipodystrophy, reduced expression of activated lipolytic proteins, and appearance of lipid breakdown by electron microscopy75,111. Dpp4 inhibitors such as FDA-approved sitagliptin accelerated recovery of DWAT from Wnt activation induced lipodystrophy75. Together, these results demonstrate a growing role of DPP4 in fibrosis and lipid handling, but the mechanism of action remains unknown.

Dermal fat has largely been overlooked in fibrosis research, but it serves critical functions in healthy skin which are likely profoundly impacted by its lipid depletion in a fibrotic context57,61,153. Among these numerous roles, adipocyte-derived factors have been implicated in controlling ECM remodeling, a role which is especially important in the context of fibrosis8,10,80. For this reason, fat grafts containing visceral adipocytes and adipose stem cells have been used to treat scleroderma and have led to improvements in skin quality and a reduction of scleroderma symptoms154,155. Understanding the causes and consequences of fibrosis associated lipodystrophy will certainly inform these types of therapies. In addition to discovering new therapeutic targets for treatment of skin fibrosis, research directed at fibrotic fat loss in the skin may have implications for other organs that exhibit fibrotic lipodystophy such as the lungs and liver1,4. Likewise, skin fibrosis researchers may draw on published data from other tissue associated with fat depots that have more established literature regarding adipocyte biology.

Adipocyte to activated fibroblasts lineage transition and impact on fibrosis:

In animal models and human acute and chronic skin and internal organ fibrosis, fat depots in obesity, diabetes, and organ frailty there is an expansion of activated fibroblasts cells and diminished mature adipocytes cell numbers7,89,97-100 (Figure 3). This change in cellular ratio contributes to ECM deposition, expansion, and change in skin and organ structure and function. Adult cells can transition between lineages by 1) de-differentiation to an immature cellular state, 2) transdifferentiate to another cell type directly or indirectly, or 3) heterotopic cell fusion were two terminally differentiated cells can fuse together100,101. Adipocyte to fibroblast lineage transition can be tracked faithfully by inducible genetic lineage tracing in mouse skin, expression of adipocytes losing perilipin1 marker expression and gaining alpha smooth muscle actin (Acta2) markers. Furthermore, lineage traced mature adipocytes can undergo dramatic morphological changes towards a dermal fibroblast phenotype64,89,102. The Rinkevich lab has challenged the conversion of lineage traced mature dermal adipocyte to profibrotic fibroblast at a functional level. They use a combination transcriptome analysis in an ex-vivo skin wounding model and transplant experiments in vivo to demonstrate that the adipocyte to fibroblasts conversion occurs transiently by morphology, but the transcriptome and function remain distinct from fibrogenic fibroblasts during wound healing103.

The transition between lineages in adult cells by dedifferentiation and transdifferentiation are achieved by transcriptional regulation104, but the transcriptional switches in adipocyte to activated fibroblasts transition remain to be identified. Recently, Wnt signaling via Wnt5a and Wnt10b may be a trigger for de-differentiation of adipocytes to fibroblasts in a tumor microenvironment105-107. Emerging evidence in a rigorous study from the Longaker group show that mechanical cues are sufficient for this transition in mouse and human adipocytes. They found Piezo-1/2 stretch channels in vivo are required for this transition during wound healing and promotes diminished scarring/regenerative healing in skin102. They also demonstrate that a subpopulation of dermal adipocytes can convert and clonally expand to profibrotic fibroblasts. Thus, targeting the adipocytes-fibroblasts transition with non-canonical Wnt signaling and mechanosensitive pathway modifiers are exciting new therapeutic avenues in fibrosis.

Lipid filled cells of the lung and their involvement in fibrosis

Pulmonary Lipofibroblasts

As in other tissues, lipid-filled cells serve critical roles in lungs. Here we will discuss those roles and how lipid-filled cells are transformed in pulmonary fibrosis. Lipofibroblasts are lipid containing fibroblast cells in the lungs which have been extensively studied in rodents, and also exist in humans156-159. Like dermal adipose tissue, lipofibroblasts of the lungs arise from common fibro/lipofibro-progenitor cell populations and their identity is controlled by expression of known adipogenic transcription factor Ppar-γ160,161,162. Because of their common origins, lipofibroblasts are highly plastic cells that can dynamically regulate their lipid and have the capacity to reversibly transdifferentiate into myofibroblasts1,163. Lipofibroblasts of the lungs exhibit dynamic lipid handling throughout development and in adult tissue. They are most abundant in the developing postnatal lung, but are still present, with less lipid content in the adult lung164. The signals and mechanisms that regulate lipofibroblast lipid handling processes will be discussed in more detail in the context of lung injury and fibrosis.

Lipofibroblasts serve numerous roles in the lung. They are critical to lung development and response to tissue injury163. Pulmonary lipofibroblasts, like white adipocytes, have been demonstrated to release triglycerides when stimulated165. These triglycerides play an essential role in protection from reactive oxygen species165. In culture, lipofibroblasts can make surfactant and play a role in the production of elastin and other extracellular matrix components164,166. Additionally, lipofibroblasts produce retinoic acid which controls lung epithelial differentiation167. Thus, loss of lung lipofibroblasts can impact lung homeostasis and is a critically important feature of lung injury and fibrosis.

Pulmonary fibrosis-associated lipodystrophy:

Despite notable differences in function and morphology between lipofibrobasts and dermal adipocytes, similar mechanisms may govern fibrotic lipodystrophy in the two tissues. Though the mechanisms haven’t yet been elucidated, disruptions of various players in lipid metabolism occur in lung fibrosis including several proteins involved in lipid uptake and release168. Additionally, in both tissues, lipid filled cells arise from progenitor populations that have the capacity to assume a myofibroblast or a lipid-laden state161,162. This common lineage between lipid-filled cells and myofibroblasts may account for plasticity in adult tissue that is seen in fibrotic disease of both tissues.

As in skin, lipid-filled cells of the lung are plastic and their transformation into myofibroblasts has been reported in chronic pulmonary fibrosis1,163. El Agha et al. showed, by lineage labeling in lung fibroblasts, that bleomycin injection stimulates the formation of myofibroblasts from lipofibroblasts1. Additionally, this phenomenon is reversible and the re-emergence of lipofibroblasts is associated with improved lung function1. Idiopathic lung fibrosis tissue samples have elevated expression of autophagy proteins, a known contributor to fibrotic fat loss in other tissues5. Kheirollahi and coleagues have shown too that treatment of human IPF samples ex vivo and treatment of murine bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis with metformin, an anti-diabetic agent, can promote a shift from myofibroblastic to lipogenic gene expression and lipid droplet formation in lung fibroblasts169. Signaling pathways involved in pulmonary lipodystrophy remain unclear. Wnt signaling is widely upregulated in lung fibrosis models and elevated Wnt signaling is known to favor myofibroblast differentiation in animal models170-174. Whether Wnt signaling is involved in lipofibroblast to myofibroblast transition in the lungs has not been determined to our knowledge. Similar to dermal fibrotic lipodystrophy, the transition from lipofibroblast to myofibroblast in the lung is driven by reduced PPARγ expression1,158,175. In these contexts as well, PPARγ agonism has been shown to promote lung function and even reverse damage, highlighting the potential for fibrosis treatment directed against known targets in adipocyte identity and lipid handling1,158,175,176.

Conserved role of Wnt and DPP4 in lung fibrosis associated lipodystrophy

The involvement of Wnt signaling and PPARγ in lung fibrosis suggests some conserved mechanism between lipid depletion of skin and lung. Another protein discussed above in regulating lipid handling in skin fibrosis is DPP4 and DPP4 inhibitors have also recently been investigated for use in treatment of lung fibrosis145. Though DPP4 hasn’t been investigated in the context of fibrotic lipodystrophy of the lung, the role of DPP4 in dermal lipid handling (discussed above) indicate a potential for its involvement in pulmonary fibrotic lipodystrophy75. In both lung and skin tissue, DPP4 inhibition is broadly fibroprotective in various models, raising the intriguing possibility that lipoprotection may play a role in previously reported improved tissue function in DPP4 inhibited lungs145. The mechanism underlying lipid depletion is not known in lipofibroblasts of the lungs, but it is possible that stimulated lipolysis might occur in lungs, as shown in dermal wound healing and fibrosis models7,75. This would be consistent with the reported accumulation of extracellular fatty acids in lungs from individuals with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, though the effects of those accumulated fatty acids may differ between lung and skin tissues177,178. Additionally, metabolic dysregulation and idiopathic lung fibrosis often co-occur, leading researchers to investigate the use of other anti-diabetic drugs for the treatment of lung fibrosis. Among these, metformin has shown promise in protecting against fibrosis, at least in part by stimulating lipid uptake in lung fibroblasts169. Rosiglitazone, another anti-diabetic drug and PPAR-γ agonist similarly has been shown to reduce pulmonary fibrosis and has an anti-myogenic effect on human lung fibroblasts in vitro1,179,180.

Non-cell autonomous effects of lipodystrophy:

One critical way that lipid-filled cells impact tissue function is through their homeostatic and stimulated release of adipokines and fatty acids that impact neighboring cells8,80. As fibrosis occurs in diverse tissues with different cellular compositions, these impacts are not entirely conserved. Some of the impacts of adipocyte-derived factors in skin and other tissues will be discussed here.

A specialized role of the secondary adipose tissue depots such as the DWAT has emerged in the context of regulating metabolism of adjacent cells. In skin, a key recipient of adipocyte-derived FAs are the fibroblast population. Zhao et al. have shown that dermal fibroblasts are subject to metabolic regulation as a result of PPAR-γ regulated fatty acid oxidation and glycolysis115. Homeostatically, fibroblasts undergo fatty acid oxidation (FAO/β -oxidation) and glycolysis in order to strike a balance between the ECM protein degradation and accumulation. The balance between the two metabolic pathways in fibroblasts maintains normal skin structure and prevents disease states such as fibrosis. Zhao et al. also show that levels of FAO and glycolysis differ in regions of skin with different ECM profiles which mirror differences between healthy and fibrotic skin of the same region115. Long chain fatty acid transporter CD36 is responsible for coupling the fibroblasts’ metabolic states with their capacities for ECM regulation, as it is essential for the degradation of collagen115. Thus, the dermal fibroblasts’ role in maintaining healthy skin structure is tied to availability of FA, indicating that dermal fibroblasts are ultimately dependent on the DWAT adipocytes’ lipid content and their ability undergo lipid breakdown processes. Adipocyte-derived fatty acids are also known to impact collagen gene expression in fibroblasts. Ezure and Amano have shown in vitro that factors released by lipid-laden cells reduce proliferation, and expression of key matrix genes in human and mouse fibroblasts and that palmitic acid alone can recapitulate inhibition of Collagen 1 gene expression and proliferation181. This suggests that lipid-laden adipocytes might offer a degree of fibroprotection that is lost when adipocytes are depleted of lipid. Another adipokine, adiponectin, is regulated by PPAR-γ, and has potent anti-fibrotic effects including inhibition of Acta2 (encoding α-sma protein) and Collagen I gene expression in control and TGF-β treated murine dermal fibroblasts and in fibrotic human fibroblasts80.

In non-skin tissue, fibrotic lipodystrophy appears to have different effects than those reported in skin due to the differing tissue composition. In lungs for example, surfactant can significantly alter the composition and accumulation of saturated fatty acids during IPF182,183. Reduced lung function has been attributed to CD36-mediated uptake of palmitic acid, causing ER stress and eventually apoptosis in lung epithelium183. In renal fibrosis, key enzymes in the FAO pathway are downregulated and linked to intracellular lipid accumulation184. Despite those notable differences however, adiponectin can reduce activation and ECM production in human renal mesangial cells as it does in dermal fibroblasts185. These findings in skin, lung, and kidney point to critical context-specific roles for dysregulated lipid metabolism in disparate fibrotic tissues which should be considered in treatment.

Major Open questions and Future directions:

Fat loss is prevalent in fibrotic disease, yet it has largely been overlooked as a therapeutic target. Lipid filled cells play critical roles in healthy tissue which are likely affected by their fibrotic transformation1,57,153,163,186. These roles differ by tissue type as does the impact of fibrotic stimulus on tissue architecture. Though the mechanisms of fibrotic fat loss have yet to be elucidated, emerging research suggests there may be common pathways involved in lipid dysregulation between tissues. Whether lipodystrophic stimuli and mechanisms are conserved between tissues remains a major unanswered question in the fibrosis field. Skin and lung are particularly good tissues in which to investigate these parallels because both tissues contain lipid-filled and myofibroblast cells derived from common progenitors. In both tissues, lipid-filled cells transform into myofibroblasts, an active cell type in fibrotic ECM accumulation. Commonly dysregulated signaling pathways between the two tissues with known roles in lipid handling, such as canonical Wnt signaling and others, should be investigated for roles in this transformation.

In addition to the canonical Wnt signaling pathway, other cellular players in fibrotic lipodystrophy may include PU.1 and Dickkopf3 (DKK3). PU.1 is required for induction of profibrotic fibroblasts and fibrosis187. PU.1 is expressed during adipocyte differentiation188 and can activate basal lipolysis and inhibit stimulated lipolysis in 3T3L1 cells in vitro189. PU.1 is expressed in aging-dependent regulated cells in subcutaneous preadipocytes and prevents differentiation of neighboring adipocyte precursor cells in vivo190. DKK3 is a divergent member of the DKK protein family and the ability DKK3 to activate Wnt signaling and contribute to tissue fibrosis is context-dependent191,192. DKK3 is expressed in adipogenesis-regulatory cells (Aregs) which can suppress adipocyte formation in vivo and in vitro in a paracrine manner193. Thus, paracrine functions of DKK3 and PU.1 may be new mechanisms of promoting lipodystrophy.

Another avenue for investigation is understanding how PPARγ, key lipid uptake/adipocyte differentiation factor, is fibroprotective. Agonism of PPARγ, has proven effective in preventing fibrotic transformation of skin, lung, liver, and kidney suggesting that adipocyte/lipofibroblast identity and associated lipid metabolism plays a role in fibrotic transformation. Thus, deeper investigation into this role may yield therapeutic targets for fibrosis therapy in several organs113,175,194,195. The role of mitochondrial dysfunction and subsequent oxidative stress is underestimated in acquired and genetic mutations leading to lipodystrophy196. Elevated Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) can occur due to severe mitochondrial dysfunction and can lead to decrease in PPARγ and adipocyte cell survival causing loss of adipocytes197,198. Genetic mutations in Laminin and CIDE-C that are associated with lipodystrophies have increased oxidative stress196,199. Given the challenges of recovering adipocytes from lipodystrophic tissues such as fibrotic skin, few studies have addressed the causative role of oxidative stress in lipodystrophy. Patient fibroblasts have been used as proxy to demonstrate presence of oxidative stress in genetic mutations associated with lipodystrophies and SSC196,199 and future studies will need to focus more directly on adipocytes during the early stages of lipodystrophy.

A promising approach is to identify and functionally validate which signaling molecules are involved in regulating lipid depletion in the context of tissue fibrosis in vivo. In both skin and lung, lipid depletion has been shown to occur prior to the transformation of once lipid-filled cells into activated fibroblasts1,7,89. In acute and chronic skin fibrosis, emerging research suggests that this transformation involves lipid breakdown by stimulated lipolysis, though corresponding studies in lung have not yet been published7,111,75. Wnt signaling and DPP4 have been implicated in this process in skin and have been shown to be similarly dysregulated in lung. In both tissues, targeting Wnt and DPP4 has led to improvement in tissue function, though neither target has been investigated specifically in the context of lipid depletion in lung. Thus, more studies are needed to obtain mechanistic insight into how Wnt and DPP4 inhibition protect against fibrosis onset and even potentially reverse existing fibrosis across tissue types.

Another direction of research needs to focus on the shared mechanisms of lipodystrophy across fibrotic tissues and research efforts need to focus on the consequences of transformation of lipid filled cells across tissues. Adipocyte-derived factors, including fatty acids, have been implicated in controlling ECM remodeling in skin, a role which is especially important in the context of fibrosis8,10,80. For this reason, fat grafts containing visceral adipocytes and adipose stem cells have been used to treat Scleroderma and have led to improvements in skin quality and a reduction of scleroderma symptoms154,155. However, fatty acid accumulation in lung tissue is pathogenic due to their impact on epithelial cells, illuminating the necessity to consider context when considering therapeutic intervention182,183. These variations in tissue architecture may lead to differences in treatment efficacy and thus need to be considered.

Finally, findings regarding the role of lipid filled cells in fibrosis will be of particular interest to researchers of other organs that exhibit fibrotic fat loss. Lipid-filled cells are critical to tissue function and are lost during fibrosis in tissues aside from skin and lungs, including liver3,6,164. Though our focus in this review has been on dermal and pulmonary fibrosis and associated lipodystrophy, other fibrotic tissues such as the liver and adipose tissue experience fibrotic lipodystrophy. In the liver, lipid-containing hepatic stellate cells (or lipocytes) store retinoids164. These cells are derived from the same precursors as ECM-producing, myofibroblastic hepatic stellate cells and they too have been shown to undergo a transformation during fibrosis onset to have reduced lipid stores5. Mechanistically this has been shown to occur by autophagy of droplets from hepatic stellate cells and their subsequent activation5. As in skin and lung, liver tissue is known to have increased Wnt activation during fibrosis, pointing to a possible conserved mechanism of lipid depletion125,129,200. Understanding how lipid-filled cells are lost or depleted of lipid will inform treatment of these life-threatening diseases.

In conclusion, findings regarding the mechanisms of lipodystrophy in skin should be investigated in lung including the involvement of Wnt signaling and its effectors. The specific lipid handling processes dysregulated to cause fibrotic lipodystrophy have yet to be thoroughly investigated in either tissue and understanding which processes are driving lipid depletion will require deeper investigation of metabolic targets in appropriate tissue-restricted models. Finally, the consequences of fibrotic lipodystrophy likely differ across tissues with different composition and these consequences remain to be tested vigorously in vivo.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank all the present members of the Atit lab for critically reading this work. This review was supported by National Institutes of Health National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases R01 AR076938 (RA). National Institutes of Health T32 Musculoskeletal Predoctoral Training Grant T32 AR 7505-31 (AJ), National Institutes of Health T32 Dermatology Predoctoral Training Grant T32 AR 7569-25 (AJ), Case Western Reserve University SOURCE fellowship (BZ), and Arnold and Mabel Beckman Fellowship (SK). Schematics were made with biorender.com.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Agha EE et al. Two-Way Conversion between Lipogenic and Myogenic Fibroblastic Phenotypes Marks the Progression and Resolution of Lung Fibrosis. Cell Stem Cell 20, 261–273.e3 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeBari MK & Abbott RD Adipose Tissue Fibrosis: Mechanisms, Models, and Importance. Int. J. Mol. Sci 21, E6030 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El Agha E. et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Fibrotic Disease. Cell Stem Cell 21, 166–177 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hernandez-Gea V & Friedman SL Pathogenesis of Liver Fibrosis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis 6, 425–456 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernández–Gea V. et al. Autophagy Releases Lipid That Promotes Fibrogenesis by Activated Hepatic Stellate Cells in Mice and in Human Tissues. Gastroenterology 142, 938–946 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rehan VK & Torday JS The lung alveolar lipofibroblast: an evolutionary strategy against neonatal hyperoxic lung injury. Antioxid. Redox Signal 21, 1893–1904 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shook BA et al. Dermal Adipocyte Lipolysis and Myofibroblast Conversion Are Required for Efficient Skin Repair. Cell Stem Cell 26, 880–895.e6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ezure T & Amano S Negative Regulation of Dermal Fibroblasts by Enlarged Adipocytes through Release of Free Fatty Acids. J. Invest. Dermatol 131, 2004–2009 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang F. et al. The adipokine adiponectin has potent anti-fibrotic effects mediated via adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase: novel target for fibrosis therapy. Arthritis Res. Ther 14, R229 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenke A. et al. Adiponectin attenuates profibrotic extracellular matrix remodeling following cardiac injury by up-regulating matrix metalloproteinase 9 expression in mice. Physiol. Rep 5, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saxena NK & Anania FA Adipocytokines and hepatic fibrosis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab 26, 153–161 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shibata R. et al. Adiponectin-mediated modulation of hypertrophic signals in the heart. Nat. Med 10, 1384–1389 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Church C, Horowitz M & Rodeheffer M WAT is a functional adipocyte? Adipocyte 1, 38–45 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eto H. et al. Characterization of Structure and Cellular Components of Aspirated and Excised Adipose Tissue: Plast. Reconstr. Surg 124, 1087–1097 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulz TJ & Tseng Y-H Brown adipose tissue: development, metabolism and beyond. Biochem. J 453, 167–178 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esteve Ràfols M. Adipose tissue: cell heterogeneity and functional diversity. Endocrinol. Nutr. Organo Soc. Espanola Endocrinol. Nutr 61, 100–112 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshimura K. et al. Characterization of freshly isolated and cultured cells derived from the fatty and fluid portions of liposuction aspirates. J. Cell. Physiol 208, 64–76 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zwick RK et al. Adipocyte hypertrophy and lipid dynamics underlie mammary gland remodeling after lactation. Nat. Commun 9, 3592 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cushman SW STRUCTURE-FUNCTION RELATIONSHIPS IN THE ADIPOSE CELL. J. Cell Biol 46, 342–353 (1970). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu Y-H & Ginsberg HN Adipocyte Signaling and Lipid Homeostasis. Circ. Res 96, 1042–1052 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burhans MS, Hagman DK, Kuzma JN, Schmidt KA & Kratz M Contribution of adipose tissue inflammation to the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Compr. Physiol 9, 1–58 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosen ED & Spiegelman BM Adipocytes as regulators of energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Nature 444, 847–853 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang A & Mottillo EP Adipocyte lipolysis: from molecular mechanisms of regulation to disease and therapeutics. Biochem. J 477, 985–1008 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vegiopoulos A, Rohm M & Herzig S Adipose tissue: between the extremes. EMBO J. 36, 1999–2017 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kershaw EE & Flier JS Adipose Tissue as an Endocrine Organ. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 89, 2548–2556 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao H. et al. Identification of a Lipokine, a Lipid Hormone Linking Adipose Tissue to Systemic Metabolism. Cell 134, 933–944 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frühbeck G, Méndez-Giménez L, Fernández-Formoso J-A, Fernández S & Rodríguez A Regulation of adipocyte lipolysis. Nutr. Res. Rev 27, 63–93 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saponaro C, Gaggini M, Carli F & Gastaldelli A The Subtle Balance between Lipolysis and Lipogenesis: A Critical Point in Metabolic Homeostasis. Nutrients 7, 9453–9474 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wallace M & Metallo CM Tracing insights into de novo lipogenesis in liver and adipose tissues. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 108, 65–71 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakers A, De Siqueira MK, Seale P & Villanueva CJ Adipose-tissue plasticity in health and disease. Cell 185, 419–446 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herman MA et al. A novel ChREBP isoform in adipose tissue regulates systemic glucose metabolism. Nature 484, 333–338 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hickner RC, Racette SB, Binder EF, Fisher JS & Kohrt WM Suppression of whole body and regional lipolysis by insulin: effects of obesity and exercise. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 84, 3886–3895 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.BasuRay S, Wang Y, Smagris E, Cohen JC & Hobbs HH Accumulation of PNPLA3 on lipid droplets is the basis of associated hepatic steatosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 116, 9521–9526 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nieman KM et al. Adipocytes promote ovarian cancer metastasis and provide energy for rapid tumor growth. Nat. Med 17, 1498–1503 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nielsen TS, Jessen N, Jørgensen JOL, Møller N & Lund S Dissecting adipose tissue lipolysis: molecular regulation and implications for metabolic disease. J. Mol. Endocrinol 52, R199–222 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carmen G-Y & Víctor S-M Signalling mechanisms regulating lipolysis. Cell. Signal 18, 401–408 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDonough PM et al. Differential Phosphorylation of Perilipin 1A at the Initiation of Lipolysis Revealed by Novel Monoclonal Antibodies and High Content Analysis. PLoS ONE 8, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zimmermann R. et al. Fat mobilization in adipose tissue is promoted by adipose triglyceride lipase. Science 306, 1383–1386 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haemmerle G. et al. Defective Lipolysis and Altered Energy Metabolism in Mice Lacking Adipose Triglyceride Lipase. Science (2006) doi: 10.1126/science.1123965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haemmerle G. et al. Hormone-sensitive lipase deficiency in mice causes diglyceride accumulation in adipose tissue, muscle, and testis. J. Biol. Chem 277, 4806–4815 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fredrikson G, Strålfors P, Nilsson NO & Belfrage P Hormone-sensitive lipase of rat adipose tissue. Purification and some properties. J. Biol. Chem 256, 6311–6320 (1981). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kraemer FB & Shen W-J Hormone-sensitive lipase. J. Lipid Res 43, 1585–1594 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tornqvist H, Nilsson-Ehle P & Belfrage P Enzymes catalyzing the hydrolysis of long-chain monoacyglycerols in rat adipose tissue. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 530, 474–486 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taschler U. et al. Monoglyceride lipase deficiency in mice impairs lipolysis and attenuates diet-induced insulin resistance. J. Biol. Chem 286, 17467–17477 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh R. et al. Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature 458, 1131–1135 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khawar MB, Gao H & Li W Autophagy and Lipid Metabolism. in Autophagy: Biology and Diseases: Basic Science (ed. Qin Z-H) 359–374 (Springer, Singapore, 2019). doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-0602-4_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh R & Cuervo AM Lipophagy: Connecting Autophagy and Lipid Metabolism. Int. J. Cell Biol 2012, 282041 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kounakis K, Chaniotakis M, Markaki M & Tavernarakis N Emerging Roles of Lipophagy in Health and Disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol 7, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cui W. et al. Lipophagy-derived fatty acids undergo extracellular efflux via lysosomal exocytosis. Autophagy 17, 690–705 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sathyanarayan A, Mashek MT & Mashek DG ATGL promotes autophagy/lipophagy via SIRT1 to control hepatic lipid droplet catabolism. Cell Rep. 19, 1–9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cingolani F & Czaja MJ Regulation and Functions of Autophagic Lipolysis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. TEM 27, 696–705 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Flaherty SE et al. A lipase-independent pathway of lipid release and immune modulation by adipocytes. Science 363, 989–993 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kranendonk MEG et al. Human adipocyte extracellular vesicles in reciprocal signaling between adipocytes and macrophages. Obes. Silver Spring Md 22, 1296–1308 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Varga J & Marangoni RG Dermal white adipose tissue implicated in SSc pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol 13, 71–72 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ebmeier S & Horsley V Origin of fibrosing cells in systemic sclerosis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol 27, 555–562 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Driskell R, Jahoda CAB, Chuong C-M, Watt F & Horsley V Defining dermal adipose tissue. Exp. Dermatol 23, 629–631 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang L. et al. Innate immunity. Dermal adipocytes protect against invasive Staphylococcus aureus skin infection. Science 347, 67–71 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kasza I. et al. Syndecan-1 Is Required to Maintain Intradermal Fat and Prevent Cold Stress. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004514 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmidt BA & Horsley V Intradermal adipocytes mediate fibroblast recruitment during skin wound healing. Dev. Camb. Engl 140, 1517–1527 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guerrero-Juarez CF & Plikus MV Emerging nonmetabolic functions of skin fat. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol 14, 163–173 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alexander CM et al. Dermal white adipose tissue: a new component of the thermogenic response. J. Lipid Res 56, 2061–2069 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wojciechowicz K, Gledhill K, Ambler CA, Manning CB & Jahoda CAB Development of the Mouse Dermal Adipose Layer Occurs Independently of Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue and Is Marked by Restricted Early Expression of FABP4. PLoS ONE 8, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Walker GE et al. Deep subcutaneous adipose tissue: a distinct abdominal adipose depot. Obes. Silver Spring Md 15, 1933–1943 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shook BA et al. Myofibroblast proliferation and heterogeneity are supported by macrophages during skin repair. Science 362, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jiang D. et al. Two succeeding fibroblastic lineages drive dermal development and the transition from regeneration to scarring. Nat. Cell Biol 20, 422–431 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nowicki JL, Takimoto R & Burke AC The lateral somitic frontier: dorso-ventral aspects of anterio-posterior regionalization in avian embryos. Mech. Dev 120, 227–240 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Atit R. et al. β-catenin activation is necessary and sufficient to specify the dorsal dermal fate in the mouse. Dev. Biol 296, 164–176 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Budnick I. et al. Defining the identity of mouse embryonic dermal fibroblasts. Genes. N. Y. N 2000 54, 415–430 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fu J & Hsu W Epidermal Wnt controls hair follicle induction by orchestrating dynamic signaling crosstalk between the epidermis and dermis. J. Invest. Dermatol 133, 890–898 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Driskell RR et al. Distinct fibroblast lineages determine dermal architecture in skin development and repair. Nature 504, 277–281 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rinkevich Y. et al. Identification and isolation of a dermal lineage with intrinsic fibrogenic potential. Science 348, aaa2151 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rodeheffer MS, Birsoy K & Friedman JM Identification of White Adipocyte Progenitor Cells In Vivo. Cell 135, 240–249 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wojciechowicz T. et al. Obestatin stimulates differentiation and regulates lipolysis and leptin secretion in rat preadipocytes. Mol. Med. Rep 12, 8169–8175 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sun L. et al. Dynamic interplay between IL-1 and WNT pathways in regulating dermal adipocyte lineage cells during skin development and wound regeneration. Cell Rep. 42, 112647 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jussila AR et al. Skin Fibrosis and Recovery Is Dependent on Wnt Activation via DPP4. J. Invest. Dermatol 142, 1597–1606.e9 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Skurk T, Alberti-Huber C, Herder C & Hauner H Relationship between adipocyte size and adipokine expression and secretion. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 92, 1023–1033 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Song Z, Xiaoli AM & Yang F Regulation and Metabolic Significance of De Novo Lipogenesis in Adipose Tissues. Nutrients 10, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bolsoni-Lopes A & Alonso-Vale MIC Lipolysis and lipases in white adipose tissue – An update. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab 59, 335–342 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang Z. et al. Dermal adipose tissue has high plasticity and undergoes reversible dedifferentiation in mice. J. Clin. Invest 129, 5327–5342 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fang F. et al. The adipokine adiponectin has potent anti-fibrotic effects mediated via adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase: novel target for fibrosis therapy. Arthritis Res. Ther 14, R229 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Festa E. et al. Adipocyte Lineage Cells Contribute to the Skin Stem Cell Niche to Drive Hair Cycling. Cell 146, 761–771 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Foster AR, Nicu C, Schneider MR, Hinde E & Paus R Dermal white adipose tissue undergoes major morphological changes during the spontaneous and induced murine hair follicle cycling: a reappraisal. Arch. Dermatol. Res 310, 453–462 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kruglikov IL & Scherer PE Dermal Adipocytes: From Irrelevance to Metabolic Targets? Trends Endocrinol. Metab 27, 1–10 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nicu C. Dermal white adipose tissue regulates human hair follicle growth and cycling. (University of Manchester, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lim CH et al. Hedgehog stimulates hair follicle neogenesis by creating inductive dermis during murine skin wound healing. Nat. Commun 9, 4903 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.George SMC, Taylor MR & Farrant PBJ Psoriatic alopecia. Clin. Exp. Dermatol 40, 717–721 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sshuster S. Psoriatic Alopecia. Br. J. Dermatol 87, 73–77 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shaw TJ, Kishi K & Mori R Wound-associated skin fibrosis: mechanisms and treatments based on modulating the inflammatory response. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 10, 320–330 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Marangoni RG, Varga J & Tourtellotte WG Animal models of scleroderma: recent progress. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol 28, 561–570 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hinchcliff M. et al. Mycophenolate Mofetil Treatment of Systemic Sclerosis Reduces Myeloid Cell Numbers and Attenuates the Inflammatory Gene Signature in Skin. J. Invest. Dermatol 138, 1301–1310 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jun J-I & Lau LF Resolution of organ fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest 128, 97–107 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Eming SA, Martin P & Tomic-Canic M Wound repair and regeneration: Mechanisms, signaling, and translation. Sci. Transl. Med 6, 265sr6 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Leavitt T. et al. Scarless wound healing: finding the right cells and signals. Cell Tissue Res. 365, 483–493 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Plikus MV et al. Regeneration of fat cells from myofibroblasts during wound healing. Science 355, 748–752 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Takeo M, Lee W & Ito M Wound Healing and Skin Regeneration. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 5, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ansell DM, Kloepper JE, Thomason HA, Paus R & Hardman MJ Exploring the ‘hair growth-wound healing connection’: anagen phase promotes wound re-epithelialization. J. Invest. Dermatol 131, 518–528 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Adigun R, Goyal A & Hariz A Systemic Sclerosis. in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2023). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Buras ED et al. Fibro-Adipogenic Remodeling of the Diaphragm in Obesity-Associated Respiratory Dysfunction. Diabetes 68, 45–56 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Contreras O. et al. Cross-talk between TGF-β and PDGFRα signaling pathways regulates the fate of stromal fibro-adipogenic progenitors. J. Cell Sci 132, jcs232157 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Merrell AJ & Stanger BZ Adult cell plasticity in vivo: de-differentiation and transdifferentiation are back in style. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 17, 413–425 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jopling C, Boue S & Izpisua Belmonte JC Dedifferentiation, transdifferentiation and reprogramming: three routes to regeneration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 12, 79–89 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Griffin MF et al. Piezo inhibition prevents and rescues scarring by targeting the adipocyte to fibroblast transition. BioRxiv Prepr. Serv. Biol 2023.04.03.535302 (2023) doi: 10.1101/2023.04.03.535302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kalgudde Gopal S. et al. Wound infiltrating adipocytes are not myofibroblasts. Nat. Commun 14, 3020 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wagers AJ & Weissman IL Plasticity of adult stem cells. Cell 116, 639–648 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chirumbolo S & Bjørklund G Can Wnt5a and Wnt non-canonical pathways really mediate adipocyte de-differentiation in a tumour microenvironment? Eur. J. Cancer Oxf. Engl. 1990 64, 96–100 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bochet L. et al. Adipocyte-derived fibroblasts promote tumor progression and contribute to the desmoplastic reaction in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 73, 5657–5668 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zoico E. et al. Adipocytes WNT5a mediated dedifferentiation: a possible target in pancreatic cancer microenvironment. Oncotarget 7, 20223–20235 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fleischmajer R, Damiano V & Nedwich A Alteration of Subcutaneous Tissue in Systemic Scleroderma. Arch. Dermatol 105, 59–66 (1972). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ishida W. et al. Intracellular TGF-beta receptor blockade abrogates Smad-dependent fibroblast activation in vitro and in vivo. J. Invest. Dermatol 126, 1733–1744 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Martins V. et al. FIZZ1-Induced Myofibroblast Transdifferentiation from Adipocytes and Its Potential Role in Dermal Fibrosis and Lipoatrophy. Am. J. Pathol 185, 2768–2776 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jussila A. et al. Adipocyte Lipolysis Abrogates Skin Fibrosis in a Wnt/DPP4-Dependent Manner. http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2021.01.21.427497 (2021) doi: 10.1101/2021.01.21.427497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Marangoni RG et al. Myofibroblasts in Murine Cutaneous Fibrosis Originate From Adiponectin-Positive Intradermal Progenitors. Arthritis Rheumatol. 67, 1062–1073 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wu M. et al. Rosiglitazone Abrogates Bleomycin-Induced Scleroderma and Blocks Profibrotic Responses Through Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-γ. Am. J. Pathol 174, 519–533 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kota BP, Huang TH-W & Roufogalis BD An overview on biological mechanisms of PPARs. Pharmacol. Res 51, 85–94 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zhao X. et al. Metabolic regulation of dermal fibroblasts contributes to skin extracellular matrix homeostasis and fibrosis. Nat. Metab 1, 147–157 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Akhmetshina A. et al. Activation of canonical Wnt signalling is required for TGF-β-mediated fibrosis. Nat. Commun 3, 735 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Beyer C. et al. β-catenin is a central mediator of pro-fibrotic Wnt signaling in systemic sclerosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis 71, 761–767 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Burgy O & Königshoff M The WNT signaling pathways in wound healing and fibrosis. Matrix Biol. J. Int. Soc. Matrix Biol 68–69, 67–80 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cheon SS et al. Beta-catenin regulates wound size and mediates the effect of TGF-beta in cutaneous healing. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol 20, 692–701 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lam AP et al. Nuclear β-Catenin Is Increased in Systemic Sclerosis Pulmonary Fibrosis and Promotes Lung Fibroblast Migration and Proliferation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol 45, 915–922 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chilosi M. et al. Aberrant Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway Activation in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol 162, 1495–1502 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Dees C. et al. The Wnt antagonists DKK1 and SFRP1 are downregulated by promoter hypermethylation in systemic sclerosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis 73, 1232–1239 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Königshoff M. et al. Functional Wnt signaling is increased in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PloS One 3, e2142 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Surendran K, Schiavi S & Hruska KA Wnt-dependent beta-catenin signaling is activated after unilateral ureteral obstruction, and recombinant secreted frizzled-related protein 4 alters the progression of renal fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 16, 2373–2384 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Piersma B, Bank RA & Boersema M Signaling in Fibrosis: TGF-β, WNT, and YAP/TAZ Converge. Front. Med 2, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cadigan KM & Liu YI Wnt signaling: complexity at the surface. J. Cell Sci 119, 395–402 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Christodoulides C, Lagathu C, Sethi JK & Vidal-Puig A Adipogenesis and WNT signalling. Trends Endocrinol. Metab 20, 16–24 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ross SE Inhibition of Adipogenesis by Wnt Signaling. Science 289, 950–953 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Cheng JH et al. Wnt antagonism inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 294, G39–49 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Duan J. et al. Wnt1/βcatenin injury response activates the epicardium and cardiac fibroblasts to promote cardiac repair. EMBO J. 31, 429–442 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Henderson WR et al. Inhibition of Wnt/beta-catenin/CREB binding protein (CBP) signaling reverses pulmonary fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 107, 14309–14314 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lam AP et al. Wnt coreceptor Lrp5 is a driver of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 190, 185–195 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Nusse R & Clevers H Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling, Disease, and Emerging Therapeutic Modalities. Cell 169, 985–999 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Wei J. et al. Canonical Wnt signaling induces skin fibrosis and subcutaneous lipoatrophy: a novel mouse model for scleroderma? Arthritis Rheum. 63, 1707–1717 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Hamburg-Shields E, DiNuoscio GJ, Mullin NK, Lafyatis R & Atit RP Sustained β-catenin activity in dermal fibroblasts promotes fibrosis by up-regulating expression of extracellular matrix protein-coding genes. J. Pathol 235, 686–697 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Mastrogiannaki M. et al. β-Catenin Stabilization in Skin Fibroblasts Causes Fibrotic Lesions by Preventing Adipocyte Differentiation of the Reticular Dermis. J. Invest. Dermatol 136, 1130–1142 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]