Abstract

Informed by minority stress and intersectionality frameworks, we examined: 1) associations of sexual identity and race/ethnicity with probable diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD-PD) among sexual minority women (SMW; e.g., lesbian, bisexual); and 2) potential additive and interactive associations of minority stressors (discrimination, stigma consciousness, and internalized homonegativity) and potentially traumatic childhood and adulthood events (PTEs) with PTSD-PD. Data come from a large and diverse community sample of SMW (N = 662; age range: 18–82; M = 40.0, SD = 14.0). The sample included 35.8% Black, 23.4% Latinx, and 37.2% White participants. Logistic regressions tested associations of sexual identity and race/ethnicity, minority stressors, and PTEs with PTSD-PD. More than one-third of SMW (37.2%) had PTSD-PD with significantly higher prevalence among bisexual, particularly White bisexual women, than lesbian women. Discrimination, stigma consciousness, and internalized homonegativity were each associated with higher odds of PTSD-PD, but only internalized homonegativity was additively associated with PTSD-PD in mutually adjusted models above and beyond effects of PTEs. No evidence for interactive effects between PTEs and minority stressors was found. In a diverse community sample of sexual minority women, PTSD is strongly associated with potentially traumatic childhood events and with minority stressors above and beyond the associations with other potentially traumatic events and stressors in adulthood. Our findings suggest a strong need for therapists to address the effects of stigma and homophobia in treatment for PTSD, as these minority stressors likely maintain and exacerbate the effects of past traumas.

Keywords: PTSD, lesbian, bisexual, discrimination, race/ethnicity, potentially traumatic events

Introduction

It is well established that across their lifespans, sexual minority women (SMW; e.g., lesbian, bisexual, queer women) experience higher rates of violence and victimization (Hughes et al., 2007, 2010; Walters et al., 2013) and interpersonal traumas (Austin et al., 2008; Balsam et al., 2005; Hughes et al., 2010; Katz-Wise & Hyde, 2012; Roberts et al., 2010) than heterosexual women. SMW report significantly higher rates of childhood maltreatment; over one-quarter of lesbian and almost one-third of bisexual women report physical abuse, neglect, or witnessing domestic violence (Roberts et al., 2010). More than half of lesbian (60%) and bisexual (54%) women report intimate partner violence (IPV) and most lesbian (89%) and bisexual (86%) women report having experienced at least one kind of traumatic event. Mental health concerns such as depression, PTSD, and substance use (Balsam et al., 2015; Jorm et al., 2002; Roberts et al., 2010) disproportionately affect SMW compared to their heterosexual counterparts (Alessi et al., 2013).

PTSD is a mental health diagnosis related to symptoms that arise in response to a traumatic event (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Directly experiencing, witnessing, or learning about a traumatic event are considered to be potential precursors to the development of PTSD. Traumas may have happened just one time or may be chronic; they may be interpersonal (e.g., partner violence, mugging) or non-interpersonal (e.g., hurricane, car accident). Symptoms of PTSD include continued intrusion of the event (e.g., flashbacks or nightmares), avoidance of reminders of the event (e.g., avoiding the places where the trauma occurred or avoiding thoughts related to the event), arousal and reactivity (e.g., being startled easily, difficulty sleeping), and cognitive and mood symptoms (e.g., negative beliefs about oneself, persistent shame, or guilt). For a diagnosis of PTSD, the symptoms must last over one month and must cause significant impairment (e.g., at work or in relationships).

Not everyone who experiences trauma develops PTSD symptoms. However, PTSD is unfortunately not uncommon. Using data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), Roberts and colleagues (2010) found that in a population-based sample, 10.4% of women and 4.3% of men met diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Sexual minority women appear to be at particularly high risk for PTSD. Lesbian (18%) and bisexual (26%) women evidence higher rates of PTSD than exclusively heterosexual women (13%; Roberts et al., 2010). These higher rates of PTSD persist even in a sample of trauma-exposed SMW and heterosexual women (86.7% and 76.3%, respectively; Weiss, Garvert, & Cloitre, 2015). However, extant research suggests that SMW’s heightened risks are not fully explained by their greater violence exposure. Two theoretical frameworks, minority stress and intersectionality, may be useful in understanding SMW’s higher risk for PTSD.

Minority Stress.

Compounding their high rates of victimization, SMW experience minority stressors such as discrimination and stigma related to their marginalized social locations (e.g., marginalization due to being a woman, a sexual minority, a person of color—and intersections between these; Brooks, 1981; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013; I. H. Meyer, 2013; Pachankis et al., 2018). Minority stressors are conceptualized as being external, objective, and distal from the self (e.g., discrimination) and as proximal and dependent on one’s appraisals, perceptions, and internalizations of distal stressors (e.g., experiences of stigma may become internalized homonegativity). According to the Sexual Minority Stress Model (Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 1995, 2013), chronic exposure specifically to sexual minority stressors (e.g., homonegativity, stigma related to sexual identity) has appreciable effects on sexual minority individuals’ mental and physical health. Among SMW, higher levels of exposure to minority stressors increases risks for multiple negative health outcomes such as depression, physical symptoms, and unhealthy behaviors (Herek & Garnets, 2007; Hughes, 2011; Keyes et al., 2012; R. J. Lewis et al., 2012; McCabe et al., 2009). Higher levels of minority stressors increase risks for poor mental and physical health by overburdening an individual’s coping resources and impairing emotion regulation (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013). Although we know that potentially traumatic events (PTEs) and minority stressors are associated with distress, we do not yet know whether they present independent risks or whether, when combined, they lead to additively (i.e., independent main effects) and/or multiplicatively (i.e., interactive effects) higher risks.

Sexual minority stressors have also been implicated in PTSD (Szymanski & Balsam, 2011). Higher numbers of sexual-identity-related microaggressions (Robinson & Rubin, 2016) and higher levels of homonegativity (Dworkin, Gilmore, et al., 2018) are associated with higher levels of PTSD symptoms. Among LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer) people, those who believed their traumatic event was related to discrimination based on sexual identity had more PTSD symptoms (Keating & Muller, 2020). In a study using NESARC data, there was no association between lifetime discrimination and PTSD among SMW (Lee et al., 2016). However, Dworkin and colleagues longitudinally examined homonegativity, interpersonal traumatic events, and PTSD in a sample of young SMW diagnosed with PTSD (Dworkin, Gilmore, et al., 2018). The authors theorized that experiencing homonegativity and other sexual minority stressors may lead to maladaptive cognitions about the self and one’s place in the world, which might in turn exacerbate PTSD symptoms. Indeed, experiencing homonegativity was prospectively associated with trauma-related negative cognitions about the self, the world, and cognitions related to self-blame, which in turn were prospectively associated with higher severity of PTSD. These findings suggest that sexual minority stressors may maintain and/or exacerbate PTSD symptoms.

Intersectionality.

Extant research has been criticized for failing to account for the influences of sources of oppression such as those related to race, sex/gender, and sexual identity (Ferlatte et al., 2018). As risks for PTSD may be influenced by multiple forms of oppression, the current study is additionally informed by an intersectional framework to consider how minority stressors related to multiply1 marginalized identities may interact to increase PTSD risks. Intersectionality accounts for the simultaneous interaction of multiple intersecting social locations and forms of oppression such as racism, sexism, and homonegativity in shaping an individual’s experience (Bowleg, 2008; Bowleg et al., 2003, 2008; Crenshaw, 1991; Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016; Ferguson et al., 2014; Lincoln, 2016; Parent et al., 2013). Examining sexual identity or racial/ethnic differences to the exclusion of the potential effects of stressors related to multiply marginalized statuses can lead to a limited or biased understanding of mental health risks and protections (Ferguson et al., 2014; Lincoln, 2016; Szymanski & Gupta, 2009). Intersectionality complements the minority stress framework as intersecting stigmas may have multiplicative (interactive) effects on mental health (Quinn, 2019).

Findings related to racial/ethnic differences in PTSD rates are mixed, with some suggesting higher rates among BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color; Alegría et al., 2013; Hall-Clark et al., 2016; Roberts, Gilman, et al., 2011) and some showing similar or lower rates than those of White individuals (Asnaani & Hall-Clark, 2017; Forman-Hoffman et al., 2016; Friedman et al., 2007). In a recent study using nationally representative data, Latinx2 and Asian American participants had lower odds and Black participants had similar odds of PTSD compared to White participants (McLaughlin et al., 2019). Among those who had experienced a PTE, Asian American participants were less likely to meet criteria for PTSD, Latinx participants were equally likely, and Black participants had a higher likelihood of PTSD than their White counterparts. Similar to the effects of sexual minority stressors, minority stressors related to racism and race-based discrimination may increase risks for PTSD above and beyond the risks associated with PTEs. For example, in a study of Black adults living in Pittsburgh, 26% screened positive for PTSD; reporting any kind of discrimination was associated with a 10% higher likelihood of screening positive for PTSD (Brooks Holliday et al., 2018). The authors did not disaggregate by sex/gender.

Interactions between race/ethnicity and sexual identity.

In comparison to lesbian women, existing evidence suggests that bisexual women experience substantially higher mental health risks (Bostwick et al., 2014, 2019; Flanders, Anderson, et al., 2019; Ross et al., 2018; Salway, Ross, et al., 2019). Some of these sexual identity differences in risks may be attributable to differential levels and types of minority stressors. For example, bisexual women report experiencing prejudice and stereotyping due to biphobic perceptions in both heterosexual and sexual minority communities (Beach et al., 2019; Bostwick & Hequembourg, 2014; Chmielewski & Yost, 2013; Flanders et al., 2016; Flanders, Shuler, et al., 2019). Rates and risks may also vary by the intersections between sexual identity and race/ethnicity given intersections between racism and biphobia (Balsam et al., 2011; Bostwick et al., 2019; Flanders, Shuler, et al., 2019; Ghabrial & Ross, 2018; Lim & Hewitt, 2018; Molina et al., 2014; Ramirez & Galupo, 2019). Conceivably, these minority stressors could heighten risks for PTSD among bisexual women, and perhaps particularly BIPOC bisexual women.

Little research has examined racial/ethnic differences in PTSD among sexual minority populations. There is even less PTSD research that has asessed within-group sexual identity differences (e.g., comparing lesbian to bisexual women) and racial/ethnic differences, despite potentially discrete risks and disparities (Balsam et al., 2015; Jorm et al., 2002; Sigurvinsdottir & Ullman, 2016). Rodriguez-Seijas and Pachankis (2019) found no significant racial/ethnic differences in rates of PTSD among heterosexual adults or among sexual minority adults in the NESARC study (no sex/gender differences were tested). However, there were significant differences in comparisons of sexual minority and heterosexual adults. Both Black and Latinx sexual minority adults had three times higher odds and White sexual minority adults had two times higher odds of PTSD diagnosis than their heterosexual counterparts. Controlling for sexual-orientation-related discrimination attenuated the associations somewhat, but there were still significant differences comparing Black and White sexual minority participants to their heterosexual counterparts, whereas for Latinx individuals there were no longer statistically significant differences in PTSD by sexual identity. Among SMW, however, several studies have documented higher rates of PTSD among BIPOC SMW compared to White SMW (Balsam et al., 2015; Jorm et al., 2002; Sigurvinsdottir & Ullman, 2016) with some evidence of higher rates of PTSD among Black bisexual than Black heterosexual and White bisexual women. A few studies have found that BIPOC SMW report the highest rates of victimization (Bostwick et al., 2019; Walters et al., 2013), which may in part explain elevated risks for PTSD.

Taken together these findings suggest that compared to heterosexual women, SMW are more likely to experience violence and victimization, mental health concerns, and possibly higher rates of PTSD—even when the rates of PTEs are similar. SMW also experience unique and chronic stress due to minority stressors, which may put them at even higher risk for mental health concerns. Trauma and minority stressors interact and may overlap (Balsam et al., 2005; D’Augelli & Grossman, 2001; Sigurvinsdottir & Ullman, 2016; Tjaden et al., 1999). This suggests a need to understand whether the potentially higher rates of mental health concerns (e.g., PTSD) are independently linked to the discrete impacts of victimization and minority stressors—or whether the combination of victimization and minority stressors may exacerbate mental health risks among SMW. However, previous research has tended to test risk factors for PTSD in isolation rather than considering that they each may compound the others’ effects. For example, most studies of PTSD among SMW focus on either criterion A events (interpersonal traumas; Alessi et al., 2013) or minority stressors (Dworkin, Gilmore, et al., 2018; Szymanski & Balsam, 2011) — none have examined the synergies between these pernicious stressors, despite SMW’s potentially high rates of PTSD and risk factors for PTSD. The dearth of research on the potentially compounding impacts of stressors related to both sexual identity and race/ethnicity on risks for PTSD amplify the need for an intersectional approach to these questions.

Current study

The higher risks for PTSD among SMW highlight that this is an important, and understudied, area—and that research on what might contribute to these higher risks is needed. As noted above, to our knowledge no research has examined whether PTEs and minority stressors—which co-occur frequently among sexual and gender minorities—multiplicatively increase SMW’s PTSD risks. Yet, PTSD is thought to have a dose-dependent relationship with traumas such that more PTEs increase the risks for developing PTSD and, as noted earlier, discrimination and other forms of stigma as well as some demographic factors also heighten risks. There is also some evidence that the combined effects of stigma and trauma may increase PTSD risks above and beyond effects of the trauma (Schneider et al., 2018).

The primary aim of this study was to test whether minority stressors (i.e., discrimination, stigma consciousness, and internalized homonegativity) and PTEs (childhood and adulthood—interpersonal and non-interpersonal) would be independently or multiplicatively associated with higher PTSD risk. This study improves upon previous research by including sexual minority stressors (stigma consciousness, internalized homonegativity, and discrimination based on sexual identity) as well as, consistent with an intersectional approach, discrimination based on gender and race/ethnicity in order to account for multiple sources of marginalization. We hypothesized that the combination of minority stressors and PTEs would multiplicatively increase risks for PTSD.

Second, relatively few studies of SMW’s health have the sample size and diversity to examine sexual identity and racial/ethnic differences, much less to test how race/ethnicity and sexual identity interact to influence risk of negative mental health outcomes like PTSD (Bowleg, 2008; Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016; Abrams et al., 2020). Thus, the current study builds upon previous research on PTSD among SMW by testing whether rates of PTSD differ by sexual identity, race/ethnicity, and the interactions between these. We hypothesized that BIPOC SMW, particularly bisexual BIPOC women, would evince the highest rates of PTSD given the disproportionate and compounding impacts of minority stressors and PTEs. Arguably, using quantitative data—as opposed to qualitative data—can be considered an insufficient method for investigating intersectional oppressions. Intersectionality’s core argument is that axes of oppression are overlapping and dynamic (Moradi & Grzanka, 2017) and categories, such as sexual identity and race/ethnicity, are limited proxies for diverse and complex experiences of racism, sexism, and bi/homophobia. However, quantitative methods can provide tools for understanding the complexities of experience and can help shed light on multiple determinants of wellbeing (McCall, 2005; Veldhuis et al., 2020). Indeed, as Crenshaw notes “recognizing that identity politics takes place at the site where categories intersect thus seems more fruitful than challenging the possibility of talking about categories at all” (Crenshaw, 1991; p.1299). Further, quantitative methods support testing whether combined effects of inequity may additively or multiplicatively exacerbate risks or promote resiliencies.

Methods

Participants

Data for this study are from the Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women (CHLEW) Study, a 22-year longitudinal study of SMW’s alcohol use and health. Recruitment for the baseline study occurred in 2000–2001 using social network and snowball sampling methods. Adult cisgender women in the greater Chicago Metropolitan area who identified as lesbian when screened for eligibility (N = 447) were interviewed. Follow-up interviews were conducted in 2004–2005 (wave 2; interviews conducted in person or over the phone) with 384 women (response rate = 86%), and again in 2010–2012 (wave 3; interviews conducted in person or over the phone) with 354 women (response rate = 79%). At wave 3 the study team added a supplemental sample of young SMW (18–24 years), Black and Latinx SMW, and bisexual women (N = 373) using a modified version of respondent-driven sampling (Hughes et al., 2021; Martin et al., 2015); all women in the supplemental sample were interviewed in person.

The current study used cross-sectional data from wave three as it includes the largest and most diverse sample (total N = 724) and the most comprehensive measure of PTSD across the waves of the study. Data for participants who identified as anything other than lesbian, mostly lesbian, or bisexual (e.g., heterosexual, mostly heterosexual; n = 27) and those with missing data for more than two of the seven PTSD symptom questions (n = 35) were excluded from analyses. This yielded an analytic sample of N = 662 ranging in age from 18 to 82 years of age (M = 40.0, SD = 14.0). Due to missing data for some victimization measures, degrees of freedom vary slightly in each analysis (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Potentially traumatic events and minority stressors by race/ethnicity and sexual identity (N = 662)

| Total (n = 662) | Race/ethnicity | Sexual identity | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Black (n = 237) | Latinx (n = 155) | White (n = 246) | p a | Bisexual (n = 170) | Lesbian (n = 492) | p a | ||||||||

| VARIABLE | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Potentially Traumatic Events (PTEs) | ||||||||||||||

| Wyatt childhood sexual abuse | 58.8 | 389 | 62.9 | 149 | 58.1 | 90 | 55.3 | 136 | 0.705 | 55.3 | 94 | 60.0 | 295 | 0.330 |

| Childhood physical abuse | 59.7 | 395 | 78.1 | 185 | 59.4 | 92 | 41.9 | 103 | <.001 | 57.6 | 98 | 60.4 | 297 | 0.606 |

| Childhood neglect | 11.5 | 76 | 10.1 | 24 | 10.3 | 16 | 13.4 | 33 | 0.661 | 9.4 | 16 | 12.2 | 60 | 0.273 |

| Adult sexual assault | 31.0 | 205 | 29.5 | 70 | 25.2 | 39 | 35.4 | 87 | 0.661 | 34.1 | 58 | 29.9 | 147 | 0.273 |

| Adult physical assault | 33.2 | 220 | 40.9 | 97 | 29.7 | 46 | 27.6 | 68 | 0.417 | 34.1 | 58 | 32.9 | 162 | 0.121 |

| Intimate partner violence (lifetime) | 30.7 | 203 | 40.5 | 96 | 36.1 | 56 | 18.7 | 46 | <.001 | 33.5 | 57 | 29.7 | 146 | 0.691 |

| Sentinel events (lifetime) | ||||||||||||||

| Interpersonal (M/SD) | 3.48 | 2.41 | 4.11 | 2.42 | 3.50 | 2.56 | 2.83 | 2.11 | 0.051 | 3.71 | 2.34 | 3.40 | 2.43 | 0.398 |

| Non-interpersonal (M/SD) | 2.30 | 1.51 | 2.57 | 1.55 | 2.17 | 1.52 | 2.09 | 1.43 | 0.025 | 2.22 | 1.37 | 2.33 | 1.56 | 0.658 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Minority Stressors | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Experienced discrimination | 1.73 | 2.60 | 1.93 | 2.88 | 1.63 | 2.42 | 1.56 | 2.38 | 0.361 | 1.89 | 2.65 | 1.68 | 2.59 | 0.301 |

| Discrim race/ethnicityb | ||||||||||||||

| Never endorsed | 80.7 | 534 | 69.6 | 165 | 77.4 | 120 | 96.3 | 237 | <.001 | 75.9 | 129 | 82.3 | 405 | 0.065 |

| Once | 12.8 | 85 | 19.8 | 47 | 14.8 | 23 | 2.4 | 6 | 15.3 | 26 | 12.0 | 59 | ||

| More than once | 6.5 | 43 | 10.5 | 25 | 7.7 | 12 | 1.2 | 3 | 8.8 | 15 | 5.7 | 28 | ||

| Discrim sexual identityb | ||||||||||||||

| Never endorsed | 67.1 | 444 | 69.2 | 164 | 68.4 | 106 | 63.4 | 156 | 0.070 | 74.7 | 127 | 64.4 | 317 | <.001 |

| Once | 16.2 | 107 | 15.6 | 37 | 14.8 | 23 | 17.9 | 44 | 9.4 | 16 | 18.5 | 91 | ||

| More than once | 16.8 | 111 | 15.2 | 36 | 16.8 | 26 | 18.7 | 46 | 15.9 | 27 | 17.1 | 84 | ||

| Discrim sex/genderb | ||||||||||||||

| Never endorsed | 83.8 | 555 | 87.8 | 208 | 82.6 | 128 | 81.7 | 201 | 0.047 | 79.4 | 135 | 85.4 | 420 | 0.532 |

| Once | 9.8 | 65 | 8.0 | 19 | 13.5 | 21 | 8.5 | 21 | 10.6 | 18 | 9.6 | 47 | ||

| More than once | 6.3 | 42 | 4.2 | 10 | 3.9 | 6 | 9.8 | 24 | 10.0 | 17 | 5.1 | 25 | ||

| Stigma consciousness (M/SD)c | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.06 | 0.96 | −0.20 | 1.15 | 0.06 | 0.96 | 0.016 | 0.09 | 1.21 | −0.02 | 0.92 | 0.599 |

| Internalized homophobia (M/SD) | 14.56 | 5.35 | 15.09 | 5.70 | 14.95 | 5.90 | 13.80 | 4.54 | <.001 | 17.20 | 6.12 | 13.65 | 4.73 | <.001 |

P-value from logistic (for dichotomous variables) linear (for continuous variables) regression on race/ethnicity, sexual identity, and race/ethnicity*sexual identity interaction, controlling for age and education.

Categories collapsed into “Any” vs “None” due to small n’s for logistic regression models

Stigma consciousness combines different questions for lesbian and bisexual women and standardizes within these groups, and then combines across the sample. As this is a standardized score, not an average score it has a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. Thus, the negative score for Latinx women (for example) indicates a lower score among that group, on average, when compared to the overall mean.

Participants of other race/ethnicities are not included in this table.

Measures

Sexual identity.

Participants were asked if they self-identified as: exclusively lesbian, mostly lesbian, bisexual, mostly heterosexual, exclusively heterosexual, or other (with the option to specify their sexual identity).

Race/ethnicity.

Race/ethnicity was determined based on two questions asking participants to indicate their race and whether they were of Hispanic or Latina/Latinx origin or descent. Responses were categorized into White, Black, and Latinx; women who identified as both Latinx and any other racial/ethnic group were categorized as Latinx (LaVeist-Ramos et al., 2012; Mora et al., 2022; Thompson & Martinez, 2022).

Potentially traumatic events (PTEs).

PTEs in this study were measured in multiple ways: Childhood PTEs were operationalized as childhood sexual abuse, childhood neglect, and childhood physical abuse. Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) was assessed using Gail Wyatt’s CSA inventory (Wyatt, 1985) of eight types of sexual experiences before age 18, ranging from exposure and fondling to anal and vaginal penetration. CSA was defined as: 1) any unwanted intrafamilial sexual activity before age 18, or that involved a family member five or more years older than the participant; and/or 2) any unwanted extrafamilial sexual activity before age 18, or before age 13 and involved another person five or more years older. Responses were used to create a dichotomous variable indicating whether or not the experiences met Wyatt’s criteria.

Questions about childhood neglect and physical abuse, and adult sexual and physical assault are from the National Study of Health and Life Experiences of Women (NSHLEW) study. The CHLEW was initially designed to replicate and extend the NSHLEW, a 20-year longitudinal study of alcohol use among women in the general U.S. population (Wilsnack et al., 2006). Childhood neglect. SMW who indicated neglect of their basic needs [(i.e., neglected my basic needs (food, clothing, shelter, love)] as a usual method of discipline were categorized as having experienced childhood neglect. Childhood physical abuse was measured by asking participants, “Do you feel that you were physically abused by your parents or other family members when you were growing up?” Responses were dichotomous (yes or no).

Adulthood PTEs were operationalized as adult sexual assault, adult physical assault, or lifetime intimate partner violence. PTSD sentinel events (both interpersonal and non-interpersonal) were also included as indicators of PTEs. Adult sexual assault was assessed by asking the participant, “Since you were 18 years old was there a time when someone forced you to have intercourse that you really did not want? This might have happened with partners, lovers, or friends, as well as with more distant persons and strangers.” Participants were asked a parallel question about other types of sexual assault. Responses were categorized as any, none, or unknown. Adult physical assault was assessed by asking, “Not counting unwanted sexual experiences, has anyone other than your partner attacked you with a gun, knife or some other weapon, whether you reported it or not?” and whether or not they had been attacked by someone other than a partner “without a weapon but with the intent to kill or seriously injure you?” Responses were dichotomized to indicate any (versus no) adult physical assault. Intimate Partner Violence (IPV). Participants were asked questions from the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus et al., 1996) to indicate whether a partner had ever “threw something at you, pushed you, or hit you?” or “threatened to kill you, with a weapon or in some other way?” A yes response to at least one of these was used to indicate any lifetime IPV. Participants were asked about a range of lifetime traumatic events which comprised both interpersonal and non-interpersonal PTSD sentinel events based on definitions of PTSD sentinel events in the DSM-IV. We created separate counts of the number of events that were interpersonal (11 questions, such as being threatened with a gun or mugged) or non-interpersonal (9 questions, such as natural disasters or car accidents).

Minority stressors

Discrimination.

The Experiences of Discrimination Scale (Krieger et al., 2005; Williams et al., 1997) includes six items representing different types of discrimination (e.g., in healthcare, in public places) based on sex/gender, race/ethnicity, and/or sexual identity and how often they occurred in the past year. Participants were asked, for example, how often they had experienced “discrimination in your ability to obtain health care or health insurance coverage?” Response options were: never, once, two or three times, four or more times. Scale scores reflect the total number of discrimination types experienced in the past year (Bostwick et al., 2014; α = .69, 95%CI 0.66, 0.73), and separate scores were calculated for discrimination based on sexual identity, gender, and race/ethnicity.

Stigma consciousness.

The Stigma Consciousness Questionnaire was developed by Pinel (1999) for use with a wide range of minoritized groups (e.g., women, gay men, Black and Latinx people). The measure assesses whether participants are influenced by stereotypes within and outside their group and the degree to which those in marginalized groups perceive stigma and stereotypes using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (0) to strongly agree (6) (Pinel, 1999). Example items include: Stereotypes about lesbians/bisexuals have not affected me personally, My being lesbian/bisexual does not influence how people act with me, and I worry that certain behaviors will be viewed as stereotypically lesbian/bisexual. The scale was modified to assess stigma consciousness for lesbian women (10 items, α = .0.76, 95%CI 0.73, 0.79) and bisexual women (11 items, α = .0.83, 95%CI 0.80, 0.87) separately. Responses were summed, and then standardized within each sexual identity group due to the different number of items in each scale. These standardized scores were then combined into a single stigma consciousness variable with higher scores indicating greater stigma consciousness.

Internalized homonegativity.

To assess the internalization of negative attitudes about sexual minority identities, we used questions adapted from Herek et al. (1997) including: I have tried to stop being attracted to women; I would like to get professional help in order to change my sexual orientation; I am proud that I am lesbian/bisexual. Participants were asked to rate each item on a five-point Likert scale of strongly agree to strongly disagree. Scores were summed to create a composite score; higher scores indicate higher levels of internalized homonegativity (α = 0.80 95%CI 0.78, 0.83).

Probable diagnosis of PTSD.

Probable diagnosis of PTSD was assessed using a scale created by Breslau and colleagues (1999) that has been validated for use with community samples to indicate probable PTSD (Breslau, Peterson, et al., 1999). The scale has been used successfully in other large-scale studies (Roberts, Rosario, et al., 2011; Trudel-Fitzgerald et al., 2016) as well as in the NESARC (Bohnert & Breslau, 2011). Although this is an older measure, it was chosen because of low participant burden, its validity for use with a community sample, and its strong concordance with PTSD-related structured interviews (Breslau, Peterson, et al., 1999; Kimerling et al., 2006). Participants who reported at least one lifetime PTE were asked seven questions about possible PTSD symptoms (e.g., Did you avoid being reminded of this experience by staying away from certain places, people, or activities?). Items cover the three symptom clusters from the DSM-IV: reexperiencing, avoidance/numbing, arousal. In the DSM-V, cognitive distortions were added to the criteria for PTSD. Breslau’s scale includes three items consistent with this new criterion: foreshortened future, diminished interest in activities, and feelings of detachment or estrangement. The number of symptoms were summed; a score of four or more indicated probable diagnosis of PTSD, hereafter referred to as PTSD-PD. The authors who developed the measure indicate that a cutoff score of 4 on the scale has a sensitivity of 80.3% and a specificity of 97.3% (Breslau, Chilcoat, et al., 1999; Breslau et al., 1998; Breslau, Peterson, et al., 1999; α = 0.81, 95%CI 0.78, 0.83).

Covariates.

Covariates included age (under 30-referent; 30–39, 40–49, 50 and above) and education (Bachelor’s degree or higher-referent, some college or less) as both age and education have been demonstrated to be associated with PTSD (Bonanno et al., 2007; Brewin et al., 2000).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to assess proportions of sexual identity, race/ethnicity, age, and education level for the whole sample and for the sample stratified by presence or absence of PTSD-PD. Similarly, proportions were calculated for PTEs including childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse, and neglect as well as adult sexual assault, physical assault, and intimate partner violence. Mean counts for interpersonal and non-interpersonal sentinel PTEs were summarized and reported by whether PTSD-PD was absent or present.

Associations between each variable and PTSD-PD were tested using logistic regressions; each measure was included as a predictor either separately (unadjusted) or controlling for sexual identity, race/ethnicity, age, and education (adjusted). Continuous measures (personal and non-interpersonal sentinel PTEs, as well as the three minority stress scales) were standardized for comparability in these models. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were used to assess strength and statistical significance of effects. Informed by an intersectionality approach (Bauer, 2014; Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016), to test the interaction of sexual identity and race/ethnicity on PTSD-PD, we fit an additional logistic regression model with the interactions between sexual identity and race/ethnicity and present results by all groups.

To test whether PTEs and minority stressors might interact to increase risks, a fully adjusted multiple logistic regression model for PTSD-PD was fit with a combination of trauma and stress variables. For the purposes of variable reduction, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of the PTEs and minority stressors was performed to identify common underlying dimensions using oblique rotation to allow for the correlation of factors. A subsequent confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) provided factor score estimates for underlying PTE and discrimination factors. Goodness of fit for the EFA and CFA were assessed with Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) using established cutoff points (RMSEA < 0.05, CFI/TLI > 0.90; Hu & Bentler, 1999). Resultant factor scores, along with sexual identity, race/ethnicity, age, and education, were included in the fully adjusted model. This model was used to assess the additive effects (i.e., independent main effects) of each predictor above and beyond the effects of the other associated variables. Interaction effects between PTEs and minority stressors were tested in additional logistic regression models including several combinations of interaction effects of PTE, minority stressors, sexual identity and race/ethnicity. Specifically, we tested 2-way interactions for PTE factors by minority stressors, PTE factors by sexual identity, PTE factors by race/ethnicity, minority stressors by sexual identity, minority stressors by race/ethnicity, and 3-way interactions of PTEs and minority stressors with sexual identity or race/ethnicity.

Missing data were rare (<2%) for all variables except for adult sexual assault (n = 41, 6.2%). This missing category was included in the individual regression models for adult sexual assault; for all other variables, listwise deletion was used. Factor scores were created using WLSMV estimation, accounting for missing data on all indicator variables. Statistical significance was determined using p < .05. Mplus version 7.11 was used for factor analyses; all other analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.

Results

Associations between demographic characteristics and PTSD-PD

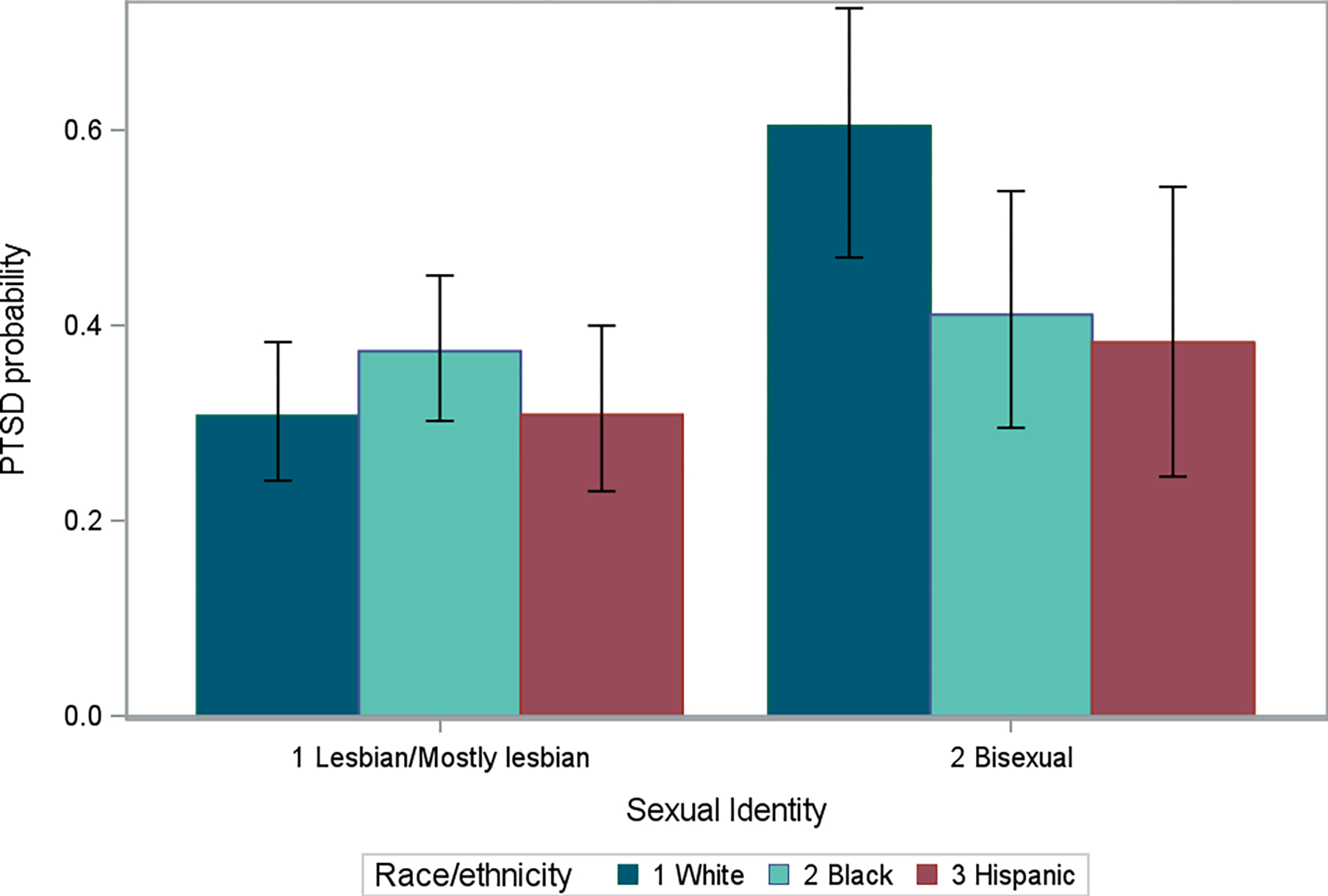

The final study sample included 662 women, 37.2% (n = 246) of whom reported four or more symptoms of PTSD (i.e., met criteria for PTSD-PD). In unadjusted models, rates of PTSD-PD were significantly higher in women who self-identified as bisexual (48.8%) than in lesbian women (33.1%) [OR = 1.93, 95% CI (1.35–2.74)]; see Table 1 for descriptive statistics. Older (>50 years old) and more highly educated SMW were less likely to meet criteria for PTSD-PD [OR = 0.61, 95% CI (0.40, 0.93); OR = 0.55, 95% CI (0.40, 0.76), respectively]. However, the significant association of age with PTSD-PD was not significant in the adjusted model. When considered alone, there were no significant differences in PTSD-PD by race/ethnicity; however, a race by sexual identity interaction (df = 2, p = 0.036) indicated a differentially higher risk in White bisexual women (Figure 1 and Supplemental Table 1). Significantly more White bisexual (60.4%) than White lesbian (30.8%) women met criteria for PTSD-PD (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Probable diagnosis of PTSD and sexual identity, race/ethnicity, age, and education (N = 662).

| Probable Diagnosis of PTSD (cutoff: 4 or more) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 416) | Yes (n = 246) | Unadjusted | Adjusted (n = 661) | |||||||

| VARIABLE | Total N | % | n | row % | n | row % | OR | CI | OR | CI |

|

|

||||||||||

| Sexual identity | 662 | |||||||||

| Lesbian/Mostly lesbian | 492 | 74.32 | 329 | 66.87 | 163 | 33.13 | ref | ref | ||

| Bisexual | 170 | 25.68 | 87 | 51.18 | 83 | 48.82 | 1.93 | (1.35 – 2.74) | 1.8 | (1.24 – 2.61) |

| Race/ethnicity | 662 | |||||||||

| White | 246 | 37.16 | 160 | 65.04 | 86 | 34.96 | ref | ref | ||

| Black | 237 | 35.80 | 138 | 58.23 | 99 | 41.77 | 1.33 | (0.92 – 1.93) | 1.00 | (0.66 – 1.50) |

| Latinx | 155 | 23.41 | 102 | 65.81 | 53 | 34.19 | 0.97 | (0.63 – 1.48) | 0.77 | (0.49 – 1.21) |

| Other | 24 | 3.63 | 16 | 66.67 | 8 | 33.33 | 0.93 | (0.38 – 2.26) | 0.82 | (0.32 – 2.05) |

| Age category | 662 | |||||||||

| Under 30 | 194 | 29.31 | 113 | 58.25 | 81 | 41.75 | ref | ref | ||

| 30 to 39 | 147 | 22.21 | 97 | 65.99 | 50 | 34.01 | 0.72 | (0.46 – 1.12) | 0.87 | (0.54 – 1.39) |

| 40 to 49 | 134 | 20.24 | 76 | 56.72 | 58 | 43.28 | 1.06 | (0.68 – 1.66) | 1.22 | (0.76 – 1.95) |

| 50 and above | 187 | 28.25 | 130 | 69.52 | 57 | 30.48 | 0.61 | (0.40 – 0.93) | 0.79 | (0.50 – 1.25) |

| Education | 661 | |||||||||

| Some college or less | 341 | 51.59 | 192 | 56.30 | 149 | 43.70 | ref | ref | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 320 | 48.41 | 224 | 70.00 | 96 | 30.00 | 0.55 | (0.40 – 0.76) | 0.59 | (0.41 – 0.85) |

Adjusted for sexual identity, race/ethnicity, age, and education

Ref = referent

Figure 1. Probable Diagnosis of PTSD and sexual identity (adjusted for age and education).

* “Other” race/ethnicity category excluded for small sample size.

PTEs and minority stressors by race/ethnicity and sexual identity

More than half of participants reported childhood sexual (58.8%) and nearly 60% (59.7%) reported physical abuse. Nearly one-third reported assault during adulthood: sexual assault (31.0%), physical assault (33.2%), and intimate partner violence (33.5%; Table 2). After adjusting for age and education differences, Black SMW reported significantly higher rates of childhood physical abuse, intimate partner violence and non-interpersonal sentinel events than White SMW (omnibus tests, see Table 2). There were no differences in PTEs by sexual identity or by the interaction between sexual identity and race/ethnicity. There were, however, differences in minority stressors.

When different types of discrimination were examined, we found racial/ethnic differences in discrimination based on race/ethnicity (p<0.001) and sexual-identity differences in discrimination based on sexual identity (p<0.001); discrimination based on sex/gender also differed by race/ethnicity (p = 0.047). Stigma consciousness was lower among Latinx compared to Black and White SMW (df = 2, p = 0.016) but did not differ by sexual identity. Internalized homonegativity differed by both race/ethnicity (p < 0.001), sexual identity (p < 0.001), and the interaction between sexual identity and race/ethnicity (p < 0.001) (Table 2 and Supplemental Table 2).

PTEs and minority stressors associated with PTSD-PD

Except for CPA, all indicators of PTEs (both childhood and adult) were significantly associated with PTSD-PD after controlling for demographic variables (Table 3). Both interpersonal (aOR 2.02, 95%CI 1.68, 2.45) and non-interpersonal sentinel events (aOR 1.47, 95%CI 1.24, 1.75) were associated with PTSD-PD, though interpersonal events were associated with higher odds of PTSD-PD than were non-interpersonal events. SMW who reported experiencing more discrimination (aOR 1.21, 95%CI 1.03, 1.43), higher stigma consciousness (aOR 1.35, 95%CI 1.14, 1.60), and more internalized homonegativity (aOR 1.20, 95%CI 1.01, 1.43) showed significantly increased odds of PTSD-PD. To tease apart the potential effects of different types of discrimination (i.e.., sexist, racist, bi/homophobic), we included discrimination based on race/ethnicity, sexual identity, and sex/gender in the model. There were no significant associations between types of discrimination based on race/ethnicity or sex/gender on PTSD-PD. However, SMW who reported more than one incident of discrimination based on sexual identity had higher odds of PTSD-PD (aOR 2.25, 95%CI 1.42, 3.54) than those who reported no discrimination. Both interpersonal and non-interpersonal sentinel events were associated with PTSD-PD, though interpersonal events were associated with higher odds of PTSD-PD than were non-interpersonal events.

Table 3.

Probable Diagnosis of PTSD, potentially traumatic events, and minority stressors.

| VARIABLE | No PTSD-PD | Yes PTSD-PD | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/mean | row %/std | n/mean | row %/std | OR/ β | CI | OR/ β | CI | |

|

| ||||||||

| POTENTIALLY TRAUMATIC EVENTS | ||||||||

| Wyatt childhood sexual abuse | ||||||||

| No | 197 | 75.77 | 63 | 24.23 | ref | ref | ||

| Yes | 210 | 53.98 | 179 | 46.02 | 2.67 | (1.88 – 3.77) | 2.92 | (2.03 – 4.19) |

| Childhood physical abuse | ||||||||

| No | 181 | 67.79 | 86 | 32.21 | ref | ref | ||

| Yes | 235 | 59.49 | 160 | 40.51 | 1.43 | (1.03 – 1.99) | 1.37 | (0.96 – 1.95) |

| Childhood neglect | ||||||||

| No | 382 | 65.19 | 204 | 34.81 | ref | ref | ||

| Yes | 34 | 44.74 | 42 | 55.26 | 2.31 | (1.43 – 3.75) | 2.39 | (1.45 – 3.95) |

| Adult sexual assault | ||||||||

| No | 283 | 68.03 | 133 | 31.97 | ref | ref | ||

| Yes | 110 | 53.66 | 95 | 46.34 | 1.84 | (1.3 – 2.59) | 1.89 | (1.32 – 2.7) |

| Adult physical assault | ||||||||

| No | 302 | 70.23 | 128 | 29.77 | ref | ref | ||

| Yes | 108 | 49.09 | 112 | 50.91 | 2.45 | (1.75 – 3.42) | 2.55 | (1.78 – 3.66) |

| Intimate partner violence (lifetime) | ||||||||

| No | 307 | 67.47 | 148 | 32.53 | ref | ref | ||

| Yes | 108 | 53.20 | 95 | 46.80 | 1.82 | (1.3 – 2.56) | 1.7 | (1.19 – 2.43) |

| Sentinel events (lifetime) | ||||||||

| Interpersonala | −0.19 | 0.89 | 0.47 | 0.99 | 2.06 | (1.72 – 2.46) | 2.02 | (1.68 – 2.45) |

| Non-interpersonala | −0.07 | 0.91 | 0.28 | 1.07 | 1.44 | (1.22 – 1.69) | 1.47 | (1.24 – 1.75) |

| MINORITY STRESS | ||||||||

| Experienced discriminationa | −0.07 | 0.93 | 0.15 | 1.11 | 1.23 | (1.06 – 1.44) | 1.21 | (1.03 – 1.43) |

| Discrimination based on sexual identity | ||||||||

| Never | 299 | 67.34 | 145 | 32.66 | ref | ref | ||

| Once | 63 | 58.88 | 44 | 41.12 | 1.44 | (0.93 – 2.22) | 1.57 | (1 – 2.47) |

| More than once | 54 | 48.65 | 57 | 51.35 | 2.18 | (1.43 – 3.32) | 2.25 | (1.42 – 3.54) |

| Discrimination based on gender | ||||||||

| Never | 350 | 63.06 | 205 | 36.94 | ref | ref | ||

| Once | 44 | 67.69 | 21 | 32.31 | 0.81 | (0.47 – 1.41) | 0.78 | (0.44 – 1.37) |

| More than once | 22 | 52.38 | 20 | 47.62 | 1.55 | (0.83 – 2.91) | 1.42 | (0.74 – 2.73) |

| Discrimination based on race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Never | 339 | 63.48 | 195 | 36.52 | ref | ref | ||

| Once | 50 | 58.82 | 35 | 41.18 | 1.22 | (0.76 – 1.94) | 1.12 | (0.68 – 1.85) |

| More than once | 27 | 62.79 | 16 | 37.21 | 1.03 | (0.54 – 1.96) | 0.96 | (0.49 – 1.89) |

| Stigma consciousnessa | −0.09 | 0.97 | 0.16 | 1.05 | 1.29 | (1.1 – 1.52) | 1.35 | (1.14 – 1.6) |

| Internalized homonegativitya | −0.14 | 0.91 | 0.11 | 1.02 | 1.30 | (1.11 – 1.53) | 1.20 | (1.01 – 1.43) |

Continuous predictor, standardized to have mean = 0 and STD = 1 across the sample, values are mean and standard deviation and beta coefficient (β) from regression

Adjusted for sexual identity, race/ethnicity, age, and education

Because of the large number of PTEs and minority stressors examined and their potential overlap with small to moderate correlations, we performed factor analyses to identify a parsimonious set of composite factors that had a conceptually meaningfully structure. A three-factor CFA model provided factor scores for three separate dimensions: childhood PTEs, adult PTEs, and discrimination (supplemental Table 3). Loadings for adult sexual assault and intimate partner violence on the adult PTE factor were low but were included as influential indicators of the underlying construct because of their conceptual importance. Internalized homonegativity did not show a statistically significant loading on any factors and so was included in subsequent models as a separate variable. CFA fit for the 3-factor model was good (RMSEA = 0.044, CFI = 0.940, TLI = 0.916).

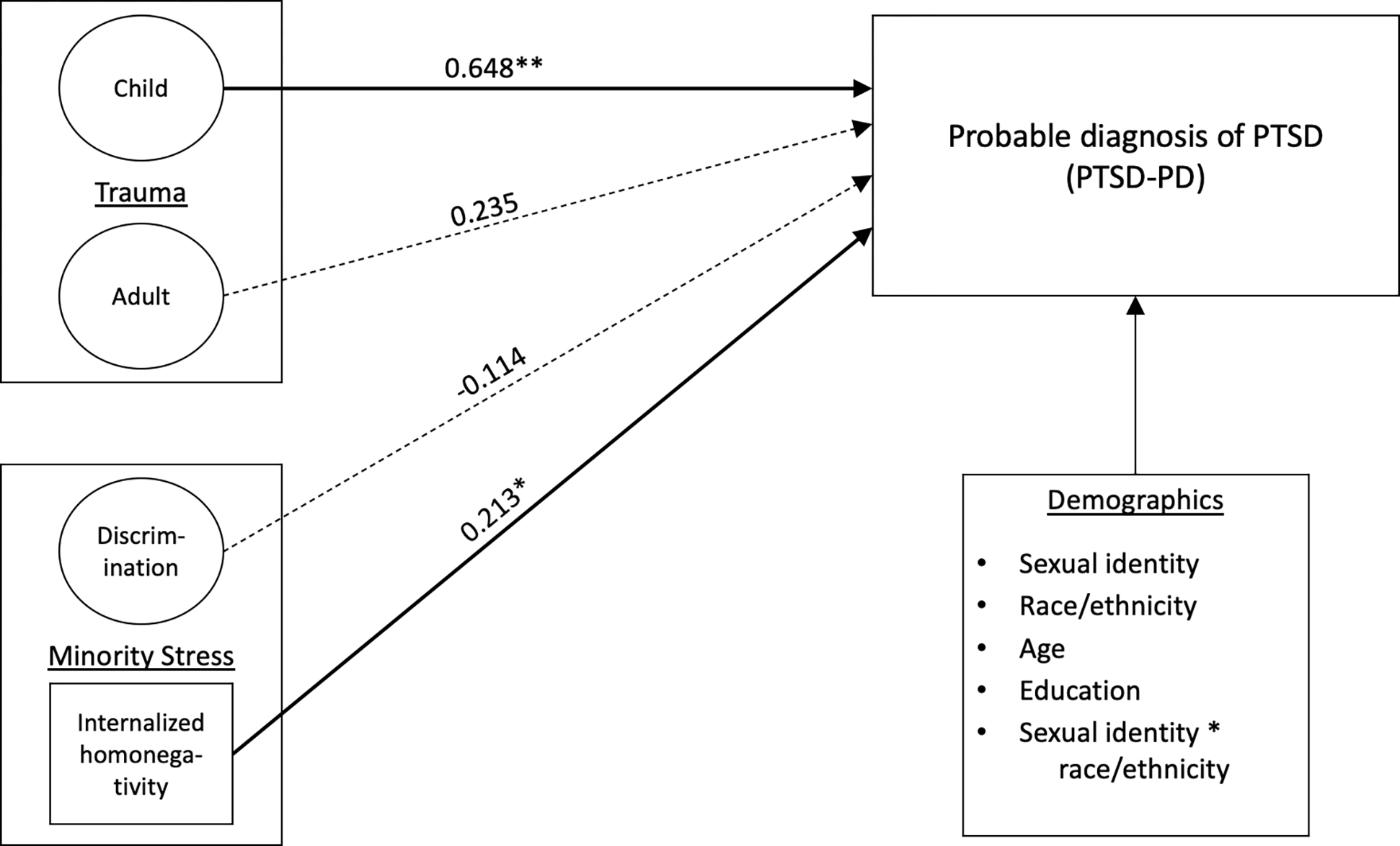

In a full model, including PTEs and minority stressors mutually adjusted for one another to identify additive effects (i.e., independent main effects); sexual identity, race/ethnicity, age, education level, and the interaction of sexual identity and race/ethnicity were also included in the model (Figure 2). Higher odds of PTSD-PD were found among women who reported childhood PTEs (aOR 1.91, 95%CI 1.26, 2.90) and internalized homonegativity (aOR 1.24, 95%CI 1.03, 1.49) but not adult PTEs or the discrimination factor. In a full model without the interaction term, bisexual compared to lesbian women continued to have increased odds of PTSD-PD (aOR 1.69, 95%CI 1.11, 2.55) above and beyond PTEs.

Figure 2. Mutually adjusted model including sexual identity, race/ethnicity, age, education level, potentially traumatic events, and minority stress variables.

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.01

Tests for interaction effects between PTEs and minority stressors did not evidence further increased odds of PTSD-PD. Specifically, we examined interactions between childhood and adulthood PTEs on the associations between internalized homonegativity and discrimination (separately) on PTSD-PD and found no significant interactions. Nor did we find interactions between PTEs and minority stress with either race/ethnicity or sexual identity in their effects on PTSD-PD. Thus, our hypothesis that minority stressors interact to increase the likelihood of PTSD-PD among those who experienced PTEs in childhood, adulthood, or both, was not supported.

Discussion

The potential consequences of PTSD are substantial; it increases the risk of substance abuse (Breslau, 2002; Breslau et al., 2003), physical health problems (Farley & Patsalides, 2001; Lehavot & Simoni, 2011; Niles et al., 2017; Zayfert et al., 2002), comorbid mental health disorders (Breslau, 2002; Breslau et al., 2003; Zayfert et al., 2002), and limits life opportunities (Kessler, 2000). Given SMW’s high rates of PTSD, understanding factors that contribute to this disparity is important. To our knowledge, ours is one of the first studies among SMW to examine whether the combination of PTEs and minority stressors additively or multiplicatively increase risks for PTSD. We found evidence that, in a diverse community sample of SMW, PTSD-PD is strongly associated with childhood PTEs and with minority stressors above and beyond the associations with other PTEs and stressors, suggesting an additive relationship between minority stressors and PTEs.

In models adjusting for demographics, CSA, childhood neglect, adult sexual assault, adult physical assault, and intimate partner violence were each associated with higher likelihood of PTSD-PD. All three sexual minority stressors (discrimination, stigma consciousness, and internalized homonegativity) were associated with higher odds of PTSD-PD. However, discrimination experiences based on gender and race/ethnicity were not associated with PTSD-PD. This finding is not consistent with previous literature suggesting that racist and sexist discriminatory experiences have negative impacts on wellbeing (Bostwick et al., 2021; Smith et al., 2022) including risk of PTSD (Berg, 2006; Holmes et al., 2016; Kira et al., 2019; Watson et al., 2016). However, findings from a meta-analysis on the effects of discrimination suggest that sexist and racist discrimination may have less impact on mental health than other forms of discrimination, like homonegative discrimination and discrimination related to concealable identities (Schmitt et al., 2014). The authors theorize that discrimination based on more concealable identities may heighten stress due to lower support from others with the same concealable identity, higher ambiguity related to the discrimination as it may be unclear whether it is the concealable identity or something else that may be the target of the discriminatory act, and the compounding impacts of concealing an identity on the impacts of the discrimination (Schmitt et al., 2014). There is some suggestion as well that early parental socialization in how to appraise and cope with discrimination is important for wellbeing (Anderson et al., 2019; Anderson & Stevenson, 2019; Cross et al., 2020). However, parental socialization in how to cope with homophobic or transphobic discrimination and bias is likely something few, if any, LGBTQ+ people have received thus perhaps heightening the impacts of the discrimination.

In mutually controlled models, that is in models that included childhood PTEs, adulthood PTEs, internalized homonegativity, and discrimination—as well as demographics—we found that childhood PTEs and internalized homonegativity were associated with higher likelihood of PTSD-PD above and beyond the effects of adult PTEs and minority stressors. This suggests an additive association between PTEs and minority stressors. Our finding of an association between internalized homonegativity (also called internalized homophobia) and PTSD symptoms is consistent with previous research (Gold et al., 2009; Straub et al., 2018). Extant research has focused on more distal (Reisner et al., 2016; Robinson & Rubin, 2016) or proximal minority stressors (Solomon et al., 2019; Straub et al., 2018) and their associations with PTSD. Less research has examined both types of minority stressors at the same time (Dworkin, Gilmore, et al., 2018). Thus, we examined the associations between PTSD and both distal (discrimination) and proximal (internalized homonegativity) minority stressors. We found that discrimination had a direct association with PTSD-PD, but this association disappeared when internalized homonegativity was included in the model. This may suggest that the links between minority stressors and PTSD are related to the activation of negative beliefs about the self and one’s sexual identity (Dworkin, Gilmore, et al., 2018), which may be more likely to occur when the minority stressors are proximal or internalized. Traumatic events may additionally reinforce negative beliefs about oneself as a sexual minority, and this may in turn increase PTSD symptom severity (Straub et al., 2018). These findings lend further support to arguments that the diagnostic criteria for PTSD should be broadened to include chronic or insidious traumatic exposure related to oppression (Alessi et al., 2013; Holmes et al., 2016; Kira et al., 2019; Szymanski & Balsam, 2011).

We expected that minority stressors would exacerbate the effects of trauma and would result in multiplicatively higher risks for PTSD-PD (Hatzenbuehler, 2009). And, indeed, as noted above, childhood PTEs and internalized homonegativity were associated with higher likelihood of PTSD-PD above and beyond the effects of the other PTEs and minority stressors, suggesting an additive effect. However, counter to our expectations of a multiplicative effect (Tsai, 2018), we found that minority stressors, in interactions with PTEs, did not increase risk of PTSD-PD. This suggests that multiply marginalized identities — and discrimination, stigma, and marginalization experienced because of those identities — may not necessarily create compounding risks for PTSD among SMW who have histories of trauma. One possible explanation for this finding may be something of a ceiling effect. For example, among SMW who have experienced childhood and/or adulthood PTEs, the stress arising from these experiences may be great enough that experiencing the marginalization of sexual minority identity may not further increase risks. It is also possible that SMW in this study had access to community and social support that may mitigate the negative effects of sexual minority stressors and discrimination based on race and gender, whereas PTEs may be less likely to have been discussed with others, perhaps particularly interpersonal PTEs. The non-significant interaction may also be related to a lack of variability given the high rates of PTEs and PTSD in this sample. Research that supports comparisons with heterosexual women and sexual minority men would be useful to evaluate interaction effects in comparison to other groups.

In this study, bisexual women (49%) reported substantially higher rates of PTSD-PD than lesbian women (33%). Interestingly, however, except for internalized homonegativity, bisexual women in this sample generally did not report higher rates of PTEs or minority stressors than lesbian women. Lesbian women reported significantly higher levels of discrimination due to sexual identity than did bisexual women. Our findings related to sexual identity and racial/ethnic differences are somewhat inconsistent with studies that have found either higher or lower psychological distress among Black and Latinx women compared to White women (Balsam et al., 2015; Bostwick et al., 2005; Calabrese et al., 2015; Himle et al., 2009; McLaughlin et al., 2019). We found no differences in PTSD-PD by race/ethnicity and only one difference in the interaction between sexual identity and race/ethnicity; White bisexual women were more likely to report PTSD-PD than bisexual BIPOC women. This finding is consistent with previous findings from research using the same sample as the current study that suggests higher levels of distress (i.e., depression) among White bisexual than Black and Latinx bisexual women (Bostwick et al., 2019).

One possible explanation for higher rates of PTSD-PD among bisexual women might be that they may be less likely to seek treatment when faced with PTEs (Ovrebo et al., 2018). Bisexual women are more likely than lesbian women to live in poverty (Gonzales et al., 2016) and to delay or not seek care for both financial and nonfinancial reasons (Dahlhamer et al., 2016). Bisexual individuals’ feelings of marginalization within both heterosexual and sexual minority communities may extend to the health care system and lead to concerns about finding culturally competent care. However, a previous analysis using the CHLEW sample (the same sample as in the current study) did not find overall differences in mental health treatment use between lesbian and bisexual women (Jeong et al., 2016). Thus, there may be other unmeasured factors such as rejection sensitivity (Dyar et al., 2018; Feinstein, 2019; Pachankis et al., 2008) or lower social support (Woulfe et al., 2021) that account for bisexual women’s, particularly White bisexual women’s, increased risks for PTSD. Although in this sample bisexual women did not report higher rates of discrimination or sigma consciousness, they did report higher rates of internalized homonegativity which may heighten anticipation of, and vigilance to, signs of rejection related to sexual identity and in turn increase risks for distress (Dyar et al., 2018; Feinstein, 2019). Our findings suggest that it is possible that higher levels of internalized homonegativity among bisexual women may also uniquely heighten risks for trauma-related cognitions and PTSD. Whether rejection sensitivity or internalized homonegativity may have particularly keen impacts for White bisexual women is unknown given the dearth of research on the intersections among gender, sexual identity, and race/ethnicity. Thus, more research is needed.

Overall, Black and Latinx SMW reported higher levels of internalized homonegativity, discrimination based on race/ethnicity, and lower levels of stigma consciousness. Given that multiply marginalized identities (e.g., being a racial/ethnic minority person, a sexual minority person, and a woman) may increase the likelihood of experiencing multiple forms of acute and chronic stressors related to those identities (Bowleg, 2008; Bowleg et al., 2008) and given the associations we found between internalized homonegativity and PTSD-PD, we expected that BIPOC SMW would show higher risks for PTSD. This compounding of stressors related to marginalized identities and discriminatory experiences was anticipated to multiplicatively increase the risk of PTSD-PD. At least in terms of comparisons within SMW, intersections between oppression related to being a BIPOC woman and a sexual minority do not appear to be associated with higher risks for PTSD-PD. Given the overall high rates of PTSD-PD and PTEs in this sample, previous research suggests differences could be found in comparison to heterosexual women (Rodriguez-Seijas et al., 2019). Previous research examining multiply marginalized identities and PTSD also did not find associations, which the researchers mused might be due to their identity measures failing to account for potential differential weighting of the impacts of discrimination (Seng et al., 2012). The impacts of discrimination may further be heightened or lessened based on how discrimination related to that identity is internalized/appraised or whether the identities might actually be protective (Seng et al., 2012). Multiply marginalized identities may lead to positive intersectionality in which people with multiply marginalized identities may benefit from connections to a group with whom they celebrate their multiple shared identities (Ghabrial, 2017), thus providing some buffers against stressors. Consistent with positive intersectionality, there is some evidence among BIPOC women that ethnic identity strength and self-esteem may play buffering roles in the links between the effects of racism and trauma symptoms (Watson et al., 2016).

Our findings also could be interpreted from a resilience perspective—that there are unmeasured protective factors reducing risks of PTSD among BIPOC SMW. For example, the steeling effect suggests that past experiences of adversity may provide tools for coping with future stressors (Doherty et al., 2018; Juster, Seeman, et al., 2016; Rutter et al., 2016). For example, for BIPOC SMW, skills developed from coping with race-related discrimination as well as potential intergenerational coping skills learned from BIPOC parents may provide buffers against other sources of discrimination. Experiencing PTEs in childhood and getting help from others in cognitively reappraising the events and developing healthy coping behaviors may provide buffers later in life when faced with other traumas.

Conversely, the sensitization effect suggests that past adversity can make it harder to cope with future stressors (Rousson et al., 2020). How well one coped with early adversity and how severe the adversity was may be key in coping with future adversities (see Höltge et al., 2018 for a review on coping with adverse experiences). Social support currently and at the time of the traumatic events also likely plays a key role in resiliency and outcomes (Dworkin, Ullman, et al., 2018; Weiss et al., 2015). Insights into potential resiliencies could be refined by measuring subjective impacts or severity of PTEs and minority stressors from a life history perspective (Boyce & Ellis, 2005). For example, Hequembourg and colleagues (2013) found that severity of adulthood and childhood sexual violence was significantly and positively associated with poorer outcomes such as risky drinking and revictimization. More research is needed to understand protective factors that may provide resources that promote resilience, particularly among BIPOC SMW, in the face of high rates of violence and victimization.

Strengths and Limitations

The current study has many strengths, including the use of a large and diverse sample which permitted comparisons by sexual identity, race/ethnicity, and the interactions between these. However, there are some limitations that should be considered when evaluating the findings. First, women who were less “out” or who were uncomfortable disclosing their sexual identity may be underrepresented in the CHLEW study. Although the sample is highly diverse, it includes too few women with race/ethnicities other than Black, Latinx, or White as well as women who identified as bi-/multiracial to include them as separate groups. Notably, Asian and Native American/Alaska Native LGBTQ+ individuals are underrepresented in research. Understanding trauma, minority stressors, stigma, and PTSD in these populations is important.

Second, our data relied on a non-probability sample which has some limitations in terms of generalizability (Salway, Morgan, et al., 2019). However, for minoritized and marginalized groups, data from non-probability samples are important for understanding population-specific factors that influence wellbeing (Drabble et al., 2018; Henderson et al., 2019; Krueger et al., 2020; Salway, Morgan, et al., 2019). Most nationally representative samples, for example, do not include measures specific to sexual and gender minorities’ concerns and thus provide a limited understanding of the predictors of health and wellbeing. LGBTQ+ participants may also feel uncomfortable disclosing their identities in studies not focused on LGBTQ+ wellbeing or may be hesitant to take part in studies that do not center the needs and concerns of the LGBTQ+ community.

Third, because our analyses used cross-sectional data, causality could not be tested. Further, participants were asked whether they had ever experienced the PTSD-related symptoms. Thus, it is not clear whether participants continue to experience PTSD symptoms, nor is the timing or temporal order of the PTSD symptoms and the minority stressors clear. It is possible that minority stressors are associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing PTSD or that PTSD increases the likelihood of experiencing minority stressors. Higher levels of PTSD symptoms may increase vigilance which may make SMW more keenly aware of discrimination, homonegativity, and stigma in their environments and more likely to feel affected by and internalize these minority stressors (Pearlin et al., 2005; Veldhuis et al., 2018). Notably in this sample, the mean age of self-identifying as an SMW was 19.4 with more than half (58.5%) of the sample identifying by age 19. One-third (31.9%) of the sample characterized a sentinel event occurring before age 19 as their most traumatic event. This suggests that, by and large, most of the women in the sample at least identified as an SMW at the time of the sentinel event, even if they had not already experienced minority stressors by then. However, more research is needed to prospectively examine the associations between minority stressors and PTSD.

Although we included discrimination based on sexual identity, gender, and race/ethnicity in this study, our indicators of intersecting sources of oppression were limited to interactions between categories of marginalized identities. Although there is a role for such quantitative research in intersectionality research (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016; Moradi & Grzanka, 2017), they are limited proxies for how oppressions may overlap. For example, gendered racial microaggressions have significant associations with mental health, including PTSD symptoms that are likely discrete from the impacts of racism-related microaggressions and gender-related microaggressions (J. A. Lewis et al., 2017; Moody & Lewis, 2019). Interaction terms between these variables are less likely to capture the impacts of these intersectional experiences. Questions about violence/victimization did not query whether those experiences were related to sexual identity; thus, we were unable to tease out whether PTSD was specifically related to sexual minority-related violence (Szymanski & Balsam, 2011).

Our measure of discrimination (the Experiences of Discrimination Scale) did not support considering the severity or perceived impacts of the discriminatory events, which could be important in better understanding links between discrimination and mental health outcomes such as PTSD (Eccleston & Major, 2006). The measure may additionally be insufficient for examining between-group differences in discrimination as it has been shown to lack equivalence by gender, race/ethnicity, age, and education. This may be due to the scale not measuring the same underlying construct for all groups and/or that the scale is not measuring these constructs to the same degree (Bastos & Harnois, 2020). For example, research using focus group interviews has demonstrated racial/ethnic differences in how the questions are interpreted and gender differences in determining the main reason for the discrimination (Harnois et al., 2019), thus potentially obscuring subgroup differences in associations between discrimination and PTSD (Bastos & Harnois, 2020). More research is needed to examine whether the EDS, and other commonly used scales, demonstrate measurement equivalence in comparisons of LGBTQ+ subgroups, as well as in comparisons with cisgender heterosexual population groups.

As the measures in this study are part of a longitudinal interview study with a long battery of measures, the PTSD scale was chosen for its brevity as well as its use among community samples and in the NESARC. As a result, we were unable to include a more comprehensive assessment of PTSD or a clinical diagnosis of PTSD. This study is also limited by exclusive use of subjective measures of psychosocial experiences. Our measures of childhood neglect and physical abuse were solely single-item measures and thus do not assess the full range of what might be considered to be abusive. These items also require that participants label what they experienced as neglect or abuse, which many may not even if what they experienced is objectively abuse. Thus, physical abuse and neglect may be underreported in this study given that the measures used were focused on perceptions of abuse or neglect.

Although the loadings for adult sexual assault and intimate partner violence were low in our CFA (less than 0.4), we chose to include them in the factor because of conceptual importance, allowing them to influence the underlying factor and factor score, while also acknowledging that the overall fit of the CFA was good. Additionally, although three indicator variables are needed at minimum to conduct a factor analysis, such an analysis that includes more than three indicator variables (such as ours, which included 11) may reveal individual factors upon which less than three indicators load.

As a complement to the subjective measures, it is possible that findings could differ with more objective measures of PTSD and impacts of stressors. The use of biological indices is of growing interest in research on LGBTQ+ health disparities (Juster, de Torre, et al., 2019; Juster et al., 2017). For example, distinct profiles of endocrine stress reactivity (Juster et al., 2015), cardiovascular functioning (Juster, Doyle, et al., 2019), and allostatic load (Juster et al., 2013) have been observed among sexual minority compared with heterosexual individuals. Given that PTSD symptoms are correlated with down-regulation of stress hormones (Marin et al., 2019), future research is needed that includes multi-systemic biological measures to triangulate objective indices with subjective experiences to better understand the mechanisms whereby stigma and trauma can “get under the skin and skull” (Juster, Russell, et al., 2016; p. 1117) of SMW. In particular, much more research is needed to identify how the impacts of intersecting sources of stressors may relate to biological indices like allostatic load among SMW (Desjardins et al., 2021; Walubita et al., 2021).

Conclusions & Clinical Implications

We found evidence that, in a diverse community sample of SMW, PTSD is strongly associated with childhood PTEs and with minority stressors above and beyond the associations with other PTEs and stressors. Although we did not find main effects for race/ethnicity, bisexual women—particularly White bisexual women—were at highest risk for PTSD. More research is needed to better understand protective factors among BIPOC SMW who did not show such associations despite a higher likelihood of reporting PTEs. We also did not find support for an interactive relationship between trauma/victimization and minority stressors on risk for PTSD, which may be related to the high rates and levels of PTEs in this sample. Research on the potential associations between overlapping minority stressors (e.g., stressors specifically related to being a BIPOC sexual minority woman), PTEs, and PTSD is needed as there is some evidence that experiencing stigma may complicate treatment of PTSD by lowering likelihood of spontaneous remission and lowering the success of treatment (Schneider et al., 2018). Arguably, even if minority stressors do not compound the effects of traumas on risks for PTSD, SMW—and particularly BIPOC SMW—already experience stigma related to their multiply marginalized identities which would suggest that treatment for trauma should address the influences of stigma on mental health.

Further, our study highlights that internalized stigma plays a role in PTSD symptoms suggesting that negative beliefs about oneself and one’s identities are implicated in the development and maintenance of mental health concerns like PTSD. Clinicians should attend to the ways in which traumatic events may not just lead to maladaptive cognitions about the trauma itself, they may also lead to, reinforce, or worsen negative thoughts about the self and about one’s sexual identity. For example, trauma survivors may feel as if they are to blame for the traumatic events because of their sexual identities, that they are being punished due to their sexual identities, or that trauma-induced negative cognitions about the self may lead to an internalization of negative thoughts about sexual identity (Dworkin, Gilmore, et al., 2018). Thus, the impacts of chronic, insidious trauma exposures need to be assessed and addressed in therapy alongside the exploration of the effects of PTEs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Ruth Kirschstein Postdoctoral Individual National Research Service Award (F32 AA025816; C.B. Veldhuis, Principal Investigator), an NIH/NIAAA Pathway to Independence K99/R00 Award (K99AA028049; PI C. Veldhuis), and by Research Grant No. R01AA13328 (T. L. Hughes, Principal Investigator) from the NIAAA/NIH. Note: the content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIAAA or NIH. R. P. Juster is supported by les Fonds de recherche Québec – Santé and holds a Sex and Gender Science Chair thanks to the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. We would like to thank Candace Burton, PhD, RN, FNE and Kristine Kulage, MA, MPH for their comments on earlier versions. We would also like to express our gratitude to CHLEW project manager Kelly Martin, MPH, MA and to the CHLEW study participants.

Footnotes

We use the term multiply to indicate that the identities have been marginalized in multiple ways, rather than that people hold multiple identities that are marginalized. The intent is to put the onus on the entity doing the marginalization rather than problematizing the identities of the individual (Cyrus, 2017).

There is some debate about the term Latinx. See Torres (2018) for a discussion and Mora et al. (2022) for a history of the term. In 2019, Pew Research surveyed Hispanic adults and found that 23% of respondents had heard of the term but only 3% used it (Noe-Bustamante et al., 2020). However, in 2020, 37% of respondents in a survey of Hispanic Californians said they used the term (Thompson & Martinez, 2022). Women were more likely than men to state that Latinx should become the prevailing term for people who are Latino/a and/or Hispanic. People who reported more discrimination, who were younger, and/or had lower incomes were also more likely to use the term and believe it should be broadly used. Together this suggests use of the term Latinx may be increasing, and that is it in use more by women and by more marginalized populations. We chose to use the term Latinx in this paper to reflect the diversity of gender and gender expression among sexual minority women. Notably, however, participants in the current study were not asked whether they prefer Latinx or Latina and to our knowledge no research to date has investigated use of the term Latinx specifically among LGBTQIA+ communities. Thus, we do not yet know whether it is the preferred term of members of the LGBTQIA+ community and more research is needed.

Contributor Information

Cindy B. Veldhuis, School of Nursing, Columbia University.

Robert-Paul Juster, Department of Psychiatry and Addiction, Université de Montréal.

Thomas Corbeil, Mental Health Data Science, New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Melanie Wall, Mental Health Data Science, New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Tonia Poteat, Department of Social Medicine, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill.

Tonda L. Hughes, School of Nursing, Columbia University.

Data Sharing:

As this is a longitudinal dataset with data collection continuing and as participants were not consented to make their data publicly available, the supporting data cannot be made available.

REFERENCES

- Abrams JA, Tabaac A, Jung S, & Else-Quest NM (2020). Considerations for employing intersectionality in qualitative health research. Social Science & Medicine, 258, 113138. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Fortuna LR, Lin JY, Norris FH, Gao S, Takeuchi DT, Jackson JS, Shrout PE, & Valentine A (2013). Prevalence, Risk, and Correlates of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Across Ethnic and Racial Minority Groups in the United States: Medical Care, 51(12), 1114–1123. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessi EJ, Meyer IH, & Martin JI (2013). PTSD and sexual orientation: An examination of criterion A1 and non-criterion A1 events. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 5(2), 149–157. 10.1037/a0026642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®) (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, Jones S, Anyiwo N, McKenny M, & Gaylord‐Harden N (2019). What’s Race Got to Do With It? Racial Socialization’s Contribution to Black Adolescent Coping. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 29(4), 822–831. 10.1111/jora.12440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, & Stevenson HC (2019). RECASTing racial stress and trauma: Theorizing the healing potential of racial socialization in families. American Psychologist, 74(1), 63–75. 10.1037/amp0000392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asnaani A, & Hall-Clark B (2017). Recent developments in understanding ethnocultural and race differences in trauma exposure and PTSD. Current Opinion in Psychology, 14, 96–101. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin SB, Jun H-J, Jackson B, Spiegelman D, Rich-Edwards J, Corliss HL, & Wright RJ (2008). Disparities in Child Abuse Victimization in Lesbian, Bisexual, and Heterosexual Women in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Journal of Women’s Health, 17(4), 597–606. 10.1089/jwh.2007.0450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Molina Y, Beadnell B, Simoni J, & Walters K (2011). Measuring multiple minority stress: The LGBT People of Color Microaggressions Scale. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(2), 163–174. 10.1037/a0023244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Molina Y, Blayney JA, Dillworth T, Zimmerman L, & Kaysen D (2015). Racial/ethnic differences in identity and mental health outcomes among young sexual minority women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(3), 380–390. 10.1037/a0038680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Rothblum ED, & Beauchaine TP (2005). Victimization Over the Life Span: A Comparison of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Heterosexual Siblings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 477–487. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos JL, & Harnois CE (2020). Does the Everyday Discrimination Scale generate meaningful cross-group estimates? A psychometric evaluation. Social Science & Medicine, 113321. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer GR (2014). Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Social Science & Medicine, 110, 10–17. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach L, Bartelt E, Dodge B, Bostwick W, Schick V, Fu T-C, Friedman MR, & Herbenick D (2019). Meta-Perceptions of Others’ Attitudes Toward Bisexual Men and Women Among a Nationally Representative Probability Sample. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(1), 191–197. 10.1007/s10508-018-1347-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]