Abstract

Objectives:

Coordination of care across health care settings is needed to ensure safe patient transfers. We examined the effects of the ECHO-Care Transitions program (ECHO-CT) on readmissions, skilled nursing facility (SNF) length of stay (LOS), and costs.

Design:

This is a prospective cohort study evaluating the ECHO-CT program. The intervention consisted of weekly 90-minute teleconferences between hospital and SNF-based teams to discuss the care of recently discharged patients.

Setting and Participants:

The intervention occurred at one small community hospital and 7 affiliated SNFs and 1 large teaching hospital and 11 associated SNFs between March 23, 2019, and February 25, 2021. A total of 882 patients received the intervention.

Methods:

We selected 13 hospitals and 172 SNFs as controls. Specific hospital-SNF pairings within the intervention and control groups are referred to as hospital-SNF dyads. Using Medicare claims data for more than 10,000 patients with transfers between these hospital-SNF dyads, we performed multivariable regression to evaluate differences in 30-day rehospitalization rates, SNF lengths of stay, and SNF costs between patients discharged to intervention and control hospital-SNF dyads. We split the post period into pre-COVID and COVID periods and ran models separately for the small community and large teaching hospitals.

Results:

There was no significant difference-in-differences among intervention compared to control facilities during either post-acute care period for any of the outcomes.

Conclusions and Implications:

Although video-communication of care plans between hospitalists and post-acute care clinicians makes good clinical sense, our analysis was unable to detect significant reductions in rehospitalizations, SNF lengths of stay, or SNF Medicare costs. Disruption of the usual processes of care by the COVID pandemic may have played a role in the null findings.

Keywords: Care transitions, rehospitalization, quality improvement

Care transitions from hospitals to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) are potentially dangerous because of gaps in communication, care team changes, different medication formularies, and misaligned treatment plans. A high burden of comorbidities, multiple medications, and impaired adaptive mechanisms, make older adults particularly vulnerable to adverse outcomes, including medication errors, miscommunication, poor follow-up, and rehospitalization.1–3 Careful coordination of care across health care settings is needed to ensure safe patient transfers, but transitions between institutions that are not collaborative leads to fragmented care and disjointed communication.4,5 Post-acute care clinicians typically receive no verbal sign-out, rely on written, nonstandardized discharge documentation of varying quality, and have difficulty accessing the discharging team for questions. Clinicians from both hospitals and SNFs request improved communication and documentation6 when transitioning patients between hospital and SNF and believe that limited information sharing may contribute to poor outcomes, such as readmissions.7 Interventions targeted at improving transitions of care may improve patient outcomes.8,9

In response to this health care challenge, physicians at our institution developed a novel videoconference intervention between hospital and SNF clinicians, called ECHO-Care Transitions (ECHO-CT), modeled after the ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) videoconferencing framework.10 This intervention was designed to improve communication between hospital and SNF in the postdischarge period, and provide physician and pharmacist expertise to review discharge plans and answer any questions that arise after discharge. Additionally, our team provided a link to hospital-based resources and could facilitate postdischarge follow-up and testing as needed. Our initial evaluation of this program used administrative data from a large teaching hospital and a prospective cohort design to evaluate outcomes in 362 individuals discharged to 47 SNFs. In this study, we found that enrolled patients had decreased 30-day readmission rates (OR 0.57, P = .034), post-acute lengths of stay (−5.52 days, P =.01), and health care costs (−$2602.19 per patient, P = .001) compared to controls.11 Similar results have been replicated in other patient populations using the ECHO model of care.12 However, our initial study was limited by implementation at a single, academic center and use of a comparator group of patients from the same institution. In this study, we attempted to overcome limitations by analyzing costs using Medicare claims, implementing ECHO-CT at a small community and large teaching hospital, and using matched hospitals and SNFs in New England as controls.

Methods

Intervention

The ECHO-CT program is described in a previous publication.13 Briefly, 90-minute videoconferences were held weekly, during which the hospital-based acute care team discussed each patient discharged during the prior week for up to 10 minutes, with each receiving SNF-based care team. SNF teams were also able to rediscuss patients who were reviewed at a prior session. The hospital-based team consisted of a facilitator (a hospitalist attending, who was usually not the patient’s inpatient clinician), social worker, project manager, pharmacist, geriatrician, primary care physician, and specialists. Although the facilitator, project manager, and pharmacist were present at all conferences, other participants attended as schedules allowed. SNF participants always included a physician or nurse clinician; additional participants would participate if available and could include physical therapists, case managers, and occasionally trainees. During the videoconference sessions, medications were reconciled, treatment plans discussed, goals of care communicated, and follow-up appointments confirmed or scheduled. Each discussion followed a templated format14 to ensure quality, reproducibility, and teamwork. Although we initially planned to have multiple SNFs on the calls at the same time to learn from each other, this proved infeasible because of time and staffing constraints. Prior to the intervention, handoffs consisted primarily of written communication via the discharge summary and instructions, with occasional verbal handoffs.

Design

This was a prospective cohort study. Patient outcomes from patients in the hospital-SNF dyads that participated in the ECHO-CT intervention were compared to a sample of patients in control dyads. Dyads are defined as hospital and SNF pairings across which patient transfers occurred. We used ECHO-CT program data, intervention hospital administrative data, person-level claims, and provider-level data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services as well as provider-level data from LTCFocus (ltcfocus.org) to inform sample selection and analyses. Because of clinical and administrative limitations, we were unable to randomize patients for discharge to experimental and control facilities and therefore choose a prospective cohort study design rather than a randomized controlled trial.

ECHO-CT intervention dyads

For this study, the ECHO-CT program was implemented at 1 large tertiary-care teaching hospital and 1 small community-based hospital in New England. Each of these hospitals discharge patients to several SNFs. SNFs were chosen to participate in the program if they received patients from either study hospital in 2018 and the discharge volume was in the middle third of all discharge volumes to SNFs receiving patients from that hospital. This criterion ensured that each SNF had a sufficient “dose” of ECHO-CT to plausibly improve the outcomes of interest but were not already so highly engaged with the study hospital that potential benefit from the intervention would be minimal. We excluded 1 SNF that had previously participated in ECHO-CT for a total of 18 hospital-SNF dyads.

Control sample

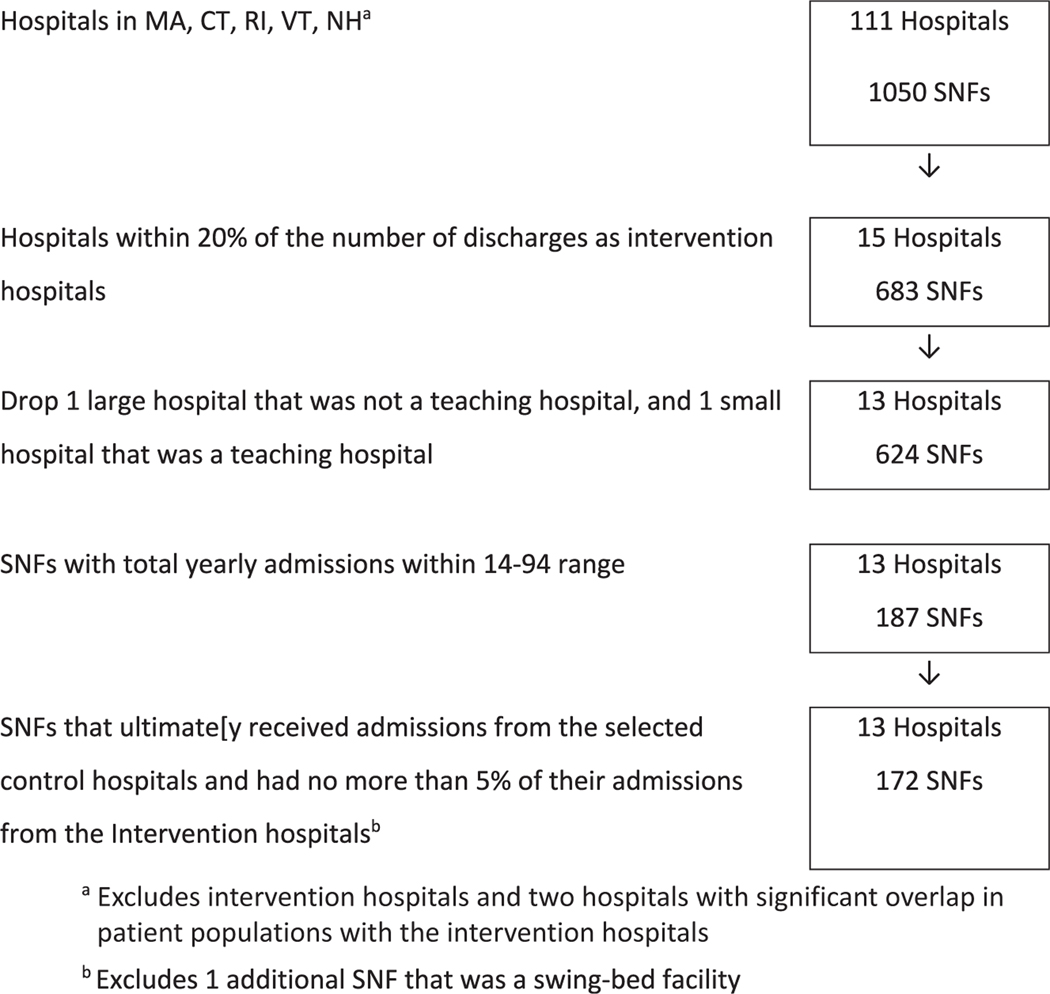

To select the set of eligible control hospital-SNF dyads, we used 2018 fee-for-service inpatient Medicare claims from all hospitals in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont, and New Hampshire, and SNF claims and MDS assessments from the SNFs to which they discharged, as well as a measure of hospital teaching status from the 2019 Open Payment List of Teaching Hospitals made publicly available by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.15 Control hospitals were matched to intervention hospitals by teaching status (teaching hospital or community-based) and size, measured as within 20% of the intervention hospitals’ annual volume of Medicare discharges to SNFs. Control SNFs were selected if discharge volume to them from the control hospital was also in the middle third of all SNFs receiving patients from that hospital (range of 14–94 patients admitted per year). The final eligible analytic data set consisted of 13 hospitals (5 large teaching hospitals and 8 small community hospitals) and 172 SNFs (Figure 1), paired into 184 unique hospital-SNF dyads. Each hospital was paired with 1 or more SNFs, and 12 SNFs met eligibility criteria to be paired with 2 hospitals each.

Fig. 1.

Hospital-SNF control selection using 2018 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) data. CT, Connecticut; MA, Massachusetts; NH, New Hampshire; VT, Vermont; RI, Rhode Island.

Patients

For all the hospital-SNF dyads, we selected all Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older who were discharged following an observation or inpatient stay from a study hospital and admitted to an affiliated SNF within 1 day of the hospital discharge. Medicare Advantage patients were excluded because these encounter records were not available to us at the time of this study; however, given that Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare populations do not differ significantly in regard to demographics, satisfaction with care, or access to care,16 we do not suspect that this would limit the generalizability of the results. Multiple observations per person were allowed.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was 30-day rehospitalization. We also evaluated length of SNF stay (up to the 100-day Medicare payment limit) and total SNF costs for a subset of patients who were not rehospitalized and did not die within 30 days. We excluded these groups given concerns that the observation period would be truncated for these groups, and rehospitalization was examined as a separate outcome.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for participant-level and SNF-level characteristics using means and SDs or frequencies and percentages, as appropriate.

We conducted difference-in-differences (DID) analyses comparing patient outcomes from a preintervention period to an intervention period for experimental and control hospital-SNF dyads. We performed separate analyses for the large teaching hospitals and the small community hospitals because one of the aims of the study was to determine if the program could be successfully implemented in a small community hospital, and splitting the analysis allowed us to determine if the intervention was more effective in one environment than another. There was no significant difference in rehospitalization rates within the small community hospital and large teaching hospital during 1-year preintervention time points, thereby supporting a parallel trend assumption for the 2 experimental hospitals.

Study periods.

January 23, 2018, to January 23, 2019, served as the preintervention period. The ECHO-CT program was implemented from March 23, 2019, to February 25, 2021. There was a 2-month pause in the program between March 29, 2020, and May 22, 2020, because of the COVID-19 pandemic and the need to deploy staff for the pandemic response. Because processes of care and patient populations differed considerably before and during the COVID pandemic, we divided the intervention period into 2 distinct periods for analysis–ECHO, pre-COVID: March 23, 2019–March 28, 2020; and ECHO, during COVID: May 23, 2020–February 25, 2021).

Statistical models.

All models included a treatment indicator, a time indicator, and a treatment by time interaction term (the primary effect of interest) to test whether the pre-post changes in outcome rates were different for patients in treatment dyads versus controls. We used adjusted generalized logistic regression with robust standard errors clustered on SNFs to estimate odds ratios, 95% CIs, and adjusted least square means for the dichotomous 30-day rehospitalization outcome. For length of stay and cost outcomes, we used adjusted quantile regression clustering on SNFs to estimate median length of stay and median costs.17,18

Therefore, in addition to considering the location (state), size (no. of discharges to SNFs), and hospital type (large teaching vs small community), we also controlled for several SNF- and patient-level characteristics. Patient characteristics were age, sex, race, more than 1 hospitalization in the 30 days prior to SNF admission, and patient comorbidity score (measured using an Elixhauser index19 derived from the index hospitalization; higher values indicate greater morbidity). Baseline SNF characteristics from LTCfocus (ltcfocus.org) and Nursing Home Compare (medicare.gov/care-compare/) included total beds, total direct care hours per resident per day, profit status, and overall 5-star rating (≥4 vs <4).

The primary analyses included all individuals with a qualifying transfer between an intervention hospital and SNF regardless of whether the case was specifically discussed in an ECHO-CT session to capture spillover effects of the intervention throughout the facilities. A patient may not have been discussed at a session if the session was canceled, if the SNF did not attend the call, or if the patient was discharged prior to the session. If a patient was unable to be discussed at a session, we performed chart review and attempted to communicate by email and phone follow-up instead (see Supplementary Table 1). To determine whether there was a difference between the individuals whose case was discussed in an ECHO-CT session and the full sample, we conducted sensitivity analyses removing individuals from intervention dyads who were not discussed or did not receive the full ECHO-CT program.

The study was reviewed and approved by the participating institutions’ Institutional Review Board. A HIPAA waiver of authorization was issued for the use of protected health information, and the use of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data was covered under the strict terms of a Data Use Agreement (DUA). The study was registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (Protocol ID: 2018P000457). Analyses were performed using a SAS statistical analysis package, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc), and Stata 17, release 17 (Stata Statistical Software).

Results

Patient and SNF characteristics in the intervention and control groups for each hospital type are presented in Table 1. There were 10,708 FFS Medicare beneficiaries discharged from the 15 hospitals included in this study to 172 eligible study SNFs (comprising 184 hospital-SNF dyads) during the baseline or intervention periods; 2498 beneficiaries were discharged from small community hospitals and 8210 from large teaching hospitals. In addition, 14.74% (1580 individuals) had multiple hospitalizations.

Table 1.

Patient (N = 10,708) and SNF (N = 184) Characteristics by Hospital Type and Intervention Status

| Characteristics | Small Community Hospitals |

Large Teaching Hospitals |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Group | Control Group | Intervention Group | Control Group | |

| Number of hospitals | 1 | 5 | 1 | 8 |

| Number of dyads | 7 | 24 | 11 | 142 |

| Patient characteristics Number. of patients |

747 | 1751 | 756 | 7454 |

| Age, mean ± SD Sex, n (%) |

85.15 ± 7.71 | 83.09 ± 8.76 | 80.65 ± 8.83 | 81.58 ± 8.74 |

| Male | 296 (39.63) | 710 (40.55) | 315 (41.67) | 2961 (39.72) |

| Female | 451 (60.37) | 1041 (59.45) | 441 (58.33) | 4493 (60.28) |

| Race, n (%) White |

712 (95.31) | 1682 (96.06) | 557 (73.68) | 6819 (91.48) |

| Other | 35 (4.69) | 69 (3.94) | 199 (26.32) | 635 (8.52) |

| ECI, mean ± SD >1 hospitalization in 30 days prior to SNF admission, n (%) |

10.30 ± 7.46 | 10.24 ± 8.04 | 10.88 ± 8.65 | 10.20 ± 7.95 |

| Yes | 161 (21.55) | 361 (20.62) | 240 (31.75) | 1723 (23.12) |

| No | 586 (78.45) | 1390 (79.38) | 516 (68.25) | 5731 (76.88) |

| Time period, n (%) Baseline period |

280 (37.48) | 734 (41.92) | 341 (45.11) | 3114 (41.78) |

| Intervention period “Pre-COVID” | 270 (36.14) | 655 (37.41) | 284 (37.57) | 2853 (38.27) |

| Intervention period “During-COVID” | 197 (26.37) | 362 (20.67) | 131 (17.33) | 1487 (19.95) |

| SNF characteristics Number of SNFs |

7 | 24 | 11 | 142 |

| Total beds, median (range) | 120 (48–191) | 104 (32–333) | 120 (44–150) | 123 (19–290) |

| Total direct care (RN, LPN, or CNA) hours/day/resident, mean (SD) | 5.04 (2.06) | 3.63 (0.85) | 3.85 (0.69) | 3.74 (0.92) |

| Profit, n (%) Yes |

3 (42.86) | 21 (87.50) | 6 (54.55) | 111 (78.17) |

| No | 4 (57.14) | 3 (12.50) | 5 (45.45) | 31 (21.83) |

| Overall star rating, n (%) 3 or less |

2 (28.57) | 10 (41.67) | 1 (9.09) | 56 (39.16) |

| 4 or 5 | 5 (71.43) | 14 (58.33) | 10 (90.91) | 86 (60.84) |

CNA, certified nursing assistant; ECI, Elixhauser Comorbidity Index; LPN, licensed practical nurse; RN, registered nurse .

Table 2 presents the results of the adjusted difference-in-differences logistic regression models for 30-day rehospitalizations (measured as adjusted least squares mean, or predicted probability of rehospitalization). There were no significant differences in pree and post–30-day hospital readmission rates in hospital-SNF dyads that participated in the ECHO-CT program compared to hospital-SNF dyads that did not. Among community hospital-SNF dyads, there was also no difference (P = .07 for pre-COVID ECHO period vs baseline, and P = .13 for COVID ECHO period vs baseline). Among large teaching hospital-SNF dyads, we also did not show a difference between intervention and control groups (P =.23 for pre-COVID ECHO vs baseline; P =.76 for COVID ECHO vs baseline).

Table 2.

Estimated Odds Ratios and 95% CIs for the Effect of the ECHO-CT Program on Adjusted 30-Day Rehospitalization Rates, Stratified by Type of Hospital (N = 10,708)

| Parameter | Parameter | Small Community Hospitals (n = 2498) |

Large Teaching Hospitals (n = 8210) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | ||

| Group | |||||||

| Group | Intervention group | 0.80 | 0.63–1.02 | .07 | 1.26 | 0.93–1.71 | .14 |

| Control group Time period |

(Ref) | (Ref) | (Ref) | (Ref) | (Ref) | (Ref) | |

| Time period | Intervention period “Pre-COVID” | 1.09 | 0.85–1.39 | .51 | 1.01 | 0.89–1.13 | .92 |

| Intervention period “During-COVID” | 0.89 | 0.65–1.22 | .46 | 0.93 | 0.80–1.08 | .33 | |

| Baseline period | (Ref) | (Ref) | (Ref) | (Ref) | (Ref) | (Ref) | |

| Group Time period | Group × Time Period Intervention period “Pre-COVID” Intervention group |

1.35 | 0.97–1.88 | .07 | 0.82 | 0.59–1.13 | .23 |

| Control group Intervention period “During-COVID” Intervention group |

1.43 | 0.90–2.28 | .13 | 1.07 | 0.68–1.69 | .76 | |

| Control group Baseline period Intervention group |

(Ref) | (Ref) | (Ref) | (Ref) | (Ref) | (Ref) | |

| Control group | |||||||

Models control for patient characteristics (age, sex, race, Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, >1 hospitalization in the 30 days prior to index SNF admission) and SNF characteristics (profit status, total beds, total direct care hours per day per resident, and overall 5-star rating).

Figure 2 shows the adjusted rates of rehospitalizations. The small community hospital-SNF dyads that received the ECHO-CT program had an adjusted baseline rehospitalization rate of 0.22, which rose to 0.29 during the pre-COVID ECHO period, and 0.27 during the COVID ECHO period, although these differences did not reach statistical significance. The control dyads for the small community hospital showed a similar pattern. Among the large teaching hospitals, the hospital-SNF dyads that received the ECHO-CT program showed a drop in rehospitalization rates in the expected direction in the pre-COVID period (from 0.29 to 0.25), but this drop was not statistically significant. The control large teaching hospital-SNF dyads did not show a change over time. The difference in the change in rehospitalization rates over time in the intervention group did not differ significantly from that of the control group (from 0.24 during baseline to 0.25 during pre-COVID time).

Fig. 2.

Adjusted rates of rehospitalization.

There were similar null findings for the SNF length of stay and 30-day SNF costs, with small, nonsignificant, increases in lengths of stay and costs for both the small community hospital and the large teaching hospital (all P > .1; Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Sensitivity Analyses

Of the patients who received the intervention, there were 104 (12%) who received a partial intervention (eg, were not discussed in the teleconference but charts were reviewed by the communication via phone or email) and 778 (88%) patients who received the full intervention. For those patients in the large teaching hospital intervention dyads, rehospitalization rates were 0.29 at baseline, 0.25 in the pre-COVID ECHO period, and 0.26 in the COVID ECHO period compared with 0.24, 0.25, and 0.23 in the control dyads, respectively. Rehospitalization rates for the small community hospital were 0.22 at baseline, 0.27 in the pre-COVID ECHO period, and 0.26 in the COVID ECHO period and 0.26, 0.28, and 0.24 in the control dyads, respectively.

Given that the majority of patients received the full intervention, results for the sensitivity analysis were similar to the full sample analysis, with no significant difference in differences between either of the study periods and baseline (see Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, we were unable to replicate our prior results showing a beneficial impact of our intervention on readmission rates, costs of care, and SNF lengths of stay. Several factors may have contributed to our null outcomes. Although we intended to closely replicate the ECHO “all teach, all learn” model, because of constraints on SNF staff availability we were unable to have all SNFs present at ECHO videoconferences to learn from each other. Instead, our videoconferencing sessions focused primarily on individual patient discussions with interspersed, informal education. Lack of adherence to the model may have resulted in less benefit than has been observed with other ECHO interventions.20 As the majority of patients received the full intervention, and there was no significant result observed in our sensitivity analysis, we do not think that lack of fidelity contributed to our null result. In part because of the stresses of the COVID pandemic, SNF participation was not as robust as we had hoped and not all patients were discussed. Additionally, although we sought to improve communication and increase the availability of hospital-based resources for the SNF-based team, we were unable to affect other components of care that may prevent a successful hospital to SNF transition, including transportation, family concerns, and financial constraints.

Pandemic interruptions also decreased our enrollment numbers and necessitated evaluating the program in 2 different time periods; both factors diminished our ability to detect a difference if one existed. The pandemic may have also blunted the impact of the intervention, as staff were stretched thin and potentially unable to engage as meaningfully as they would have otherwise. Another limitation is lack of randomization. Although we adjusted for patient- and facility-level characteristics, other unmeasured factors may have affected the outcomes. Another potential limitation was our ability to roll out the intervention in only 2 hospitals given budget and other constraints. Although this may have limited our variability in resulting hospital-SNF dyads, we intentionally chose a large teaching hospital and a small community hospital to capture as much variability as possible. In addition, each of those hospitals discharge to multiple SNFs, increasing variability.

Finally, given broad selection of control hospitals and SNFs using claims data, we do not know what other interventions may have been occurring in the control hospitals to improve transitions of care. That said, in our experience, most hospitals do not utilize methods beyond written communication at the time of discharge; therefore, we would expect the effect of any one intervention at a control hospital to be small.

Conclusions and Implications

Although we did not see a significant effect of our intervention on our preselected outcomes, we believe ECHO-CT may have been beneficial in unmeasured ways that could be addressed in future research. We discovered many transition errors during ECHO-CT sessions, including medication discrepancies and communication gaps that will be reported separately. Improved communication and relationships between hospital and SNF staff did not clearly change rehospitalization rates, cost of care, or SNF LOS; however, it may have resulted in more coordinated, less-fragmented care for patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to posthumously recognize Jessica Ogarek, who began work on the project as lead programmer before her terminal illness, as well as Yoojin Lee, Brown’s Center for Gerontology and Health Care Research’s Lead Data Scientist, who was instrumental in providing support and mentorship during this study.

The study was supported by a grant (R01 HS25702–02) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD.

Footnotes

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2023.09.001.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Coleman EA. Falling through the cracks: challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler C, Williams MC, Moustoukas JN, Pappas C. Transitions of care for the geriatric patient in the emergency department. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29: 49–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman EA, Berenson RA. Lost in transition: challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of transitional care. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:533–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naylor M, Keating SA. Transitional care. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(9 Suppl):58–63. quiz 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valverde PA, Ayele R, Leonard C, Cumbler E, Allyn R, Burke RE. Gaps in hospital and skilled nursing facility responsibilities during transitions of care: a comparison of hospital and SNF clinicians’ perspectives. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36: 2251–2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark B, Baron K, Tynan-McKiernan K, Britton M, Minges K, Chaudhry S. Perspectives of clinicians at skilled nursing facilities on 30-day hospital readmissions: a qualitative study. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:632–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parrish MM, O’Malley K, Adams RI, Adams SR, Coleman EA. Implementation of the care transitions intervention: sustainability and lessons learned. Prof Case Manag. 2009;14:282–293. quiz 294–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1822–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arora S, Thornton K, Jenkusky SM, Parish B, Scaletti JV. Project ECHO: linking university specialists with rural and prison-based clinicians to improve care for people with chronic hepatitis C in New Mexico. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 2):74–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore AB, Krupp JE, Dufour AB, et al. Improving transitions to postacute care for elderly patients using a novel video-conferencing program: ECHO-care transitions. Am J Med. 2017;130:1199–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cantor JC, Chakravarty S, Farnham J, Nova J, Ahmad S, Flory JH. Impact of a provider tele-mentoring learning model on the care of medicaid-enrolled patients with diabetes. Med Care. 2022;60:481–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farris G, Sircar M, Bortinger J, et al. Extension for community healthcare outcomes-care transitions: enhancing geriatric care transitions through a multidisciplinary videoconference. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:598–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipsitz L, Moore A, Junge-Maughan L. Project ECHO care-transitions programToolkit. Accessed October 18, 2022. https://www.bidmc.org/-/media/files/beth-israel-org/research/research-by-department/medicine/gerontology/echo-care/bidmc-echo-ct-toolkit-032521.pdf

- 15.Open Payments List of Teaching Hospitals. Accessed October 18, 2022. https://www.cms.gov/OpenPayments/Downloads/2019-Reporting-Cycle-Teaching-Hospital-List-pdf.pdf

- 16.The Commonwealth Fund. Medicare advantage vs. Traditional medicare: howdo beneficiaries’ characteristics and experiences differ. Accessed October 18, 2022. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2021/oct/medicare-advantage-vs-traditional-medicare-beneficiaries-differ

- 17.Machado JAF, Parente PMDC, Santos Silva JMC. qreg2: Stata module to perform quantile regression with robust and clustered standard errors. Statistical Software Components S457369. Boston College Department of Economics; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parente P, Santos Silva J. Quantile regression with clustered data. J Econom Methods. 2016;5:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arora S, Thornton K, Murata G, et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providers. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2199–2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.