Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in women, with underrepresented minority (URM) women experiencing the highest mortality rate. For decades, there has been an underrepresentation of women in CVD trials. Although more recent studies have increased the number of women enrolled in these trials, systematic reviews have demonstrated that this enrollment is still low. The National Institute of Health along with other agencies have boosted their efforts to increase enrollment of women and URM populations in CVD trials. Despite these efforts, there still remains a gap. This paper reviews the magnitude, implications and causes of the underrepresentation of women in CVD trials. A proposed multifaceted approach to solving this issue is also outlined in this commentary. Hopefully, implementation of these proposed solutions may facilitate the increase of women, including URM women, enrolled in CVD trials. It is anticipated that this will improve CVD outcomes in these patients.

Keywords: Women, Heart disease, CAD, Cardiovasular disease, Underrepresented minority populations, Clinical trials

Highlights

-

•

Women are significantly underrepresented in the majority of CV research studies.

-

•

CV study results are erroneously extrapolated to women and URM despite potential harm.

-

•

Participation to prevalence ratio (PPR) for women in most CV trials is consistently <0.8.

-

•

Lack of enrollment of women in CV trials may be due to multiple factors including socioeconomic and community factors.

-

•

A multifaceted approach to addressing the underrepresentation of women in CV trials is recommended.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular (CV) disease is the leading cause of mortality for women worldwide [1], [2]. In the United States women bear a disproportionate burden of death and disability from CV disease [1], [3], [4]. African-American women in the US bear the greatest CV mortality burden relative to other ethnicities [5]. Despite this fact women including women from underrepresented minority populations (URM) are still consistently poorly represented in research studies [6]. This has widespread consequences in the overall evaluation, stratification, and treatment of women with CV disease, as prior research based on male participants should not be extrapolated to women. A study by Jin, et al., found that out of 740 completed CV trials including a total of 862,652 adults, only 38.2% were women [6].

This under-representation extends to multiple CV research areas, particularly imaging trials as was outlined in the review article by Brown, et al. published in this edition of the Journal. Cardiac imaging is a natural starting point for the assessment of disease burden. In the most recently completed CV imaging trials, the PROMISE trial included the greatest proportion of women (52.7%) [7]. However, in other imaging trials, women still only represent a minority of the subjects [8], [9], [10]. This commentary will review the magnitude and implications for the underrepresentation of women in CV trials as well as the proposed causes potential solutions of this underrepresentation.

2. Magnitude of the problem and its implications

The continuing work to advance the health of women has included advocacy for increasing the representation of women in clinical studies. It has been reported that even when women have been included as subjects in clinical research, the influence of sex and ethnicity are not widely analyzed and reported for various health outcomes [11].

Historically, advocacy for increasing women's health can be drawn back to a milestone in 1990 when the National Institute of Health (NIH) Office of Research on Women's Health was formed in response to congressional, scientific and advocacy concerns. The lack of systemic and consistent inclusion of women in NIH-supported clinical research was concerning as this could result in clinical health-care decisions being made for women based solely on male predominant study findings, without any evidence that they were applicable to women [12].

This recognition of female underrepresentation led to the NIH Revitalization Act in 1993, which aimed to increase enrollment of women and URM in clinical trials [13]. Despite all these efforts and other public initiatives to raise awareness about women and heart disease, recent data continue to show that enrollment of women including URM women still lags behind that of men [6].

There have been published studies that illustrate consistent findings highlighting the underrepresentation of women. These studies include the landmark Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries (GUSTO) trial, which enrolled over 40,000 patients to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of fibrinolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction (AMI). In this study, women constituted only 25% of the trial participants [14]. A systematic review of 325 CV trials published in three leading medical journals from 1997 to 2009 estimated that 1 in 3 participants were women [15]. After accounting for age- and sex-specific differences in disease prevalence, however, the enrollment rates of women were lower than expected, estimated at 3% to 13% across the spectrum of CV diseases [15].

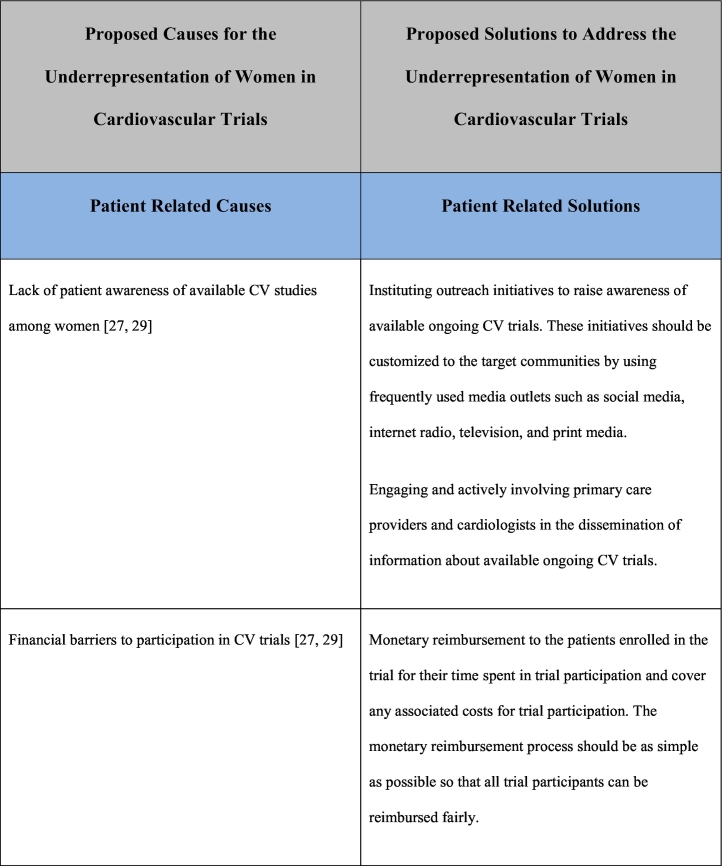

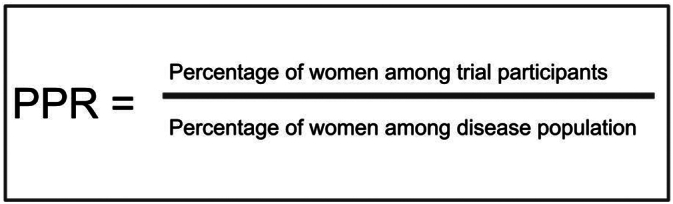

A more contemporary systematic review indicates that this underrepresentation of women in CV trials persist with women representing approximately one third of the study population in most studies [6]. Participation to prevalence ratio (PPR) is a measure to describe the representation of women in a trial with respect to their proportion in the disease population Fig. 1 [16]. The ideal PPR is considered to be 0.8–1.2, which indicates a good representation of women in a study [16]. Even after adjusting for prevalence, it has been shown that trials related to heart failure, acute coronary syndromes, and coronary artery disease (CAD) have consistent underrepresentation of women with PPR <0.8 [6]. Trials related to device placement, procedures and multi-interventions had lower representation of women compared to trials focused on lifestyle and medications, and trials conducted in the Americas had better representation than those conducted in Europe and the Western Pacific [6]. Besides NIH sponsored trials, government sponsored trials had lower enrollment of women [6]. Additionally, low representation of women was particularly seen in women 61–65 years of age [6].

Fig. 1.

Calculation of the participation to prevalence ratio (PPR)

An outline of the calculation of the participation to prevalence ratio (PPR) [16].

Recent CV imaging studies also had low enrollment of women. In the SCOT-HEART trial, investigators reported 44% of the study population being women [8], the ICONIC trial reported 36.3% of the acute coronary syndrome patients being women [10] and the ISCHEMIA trial reported 22.6% women [9]. This is of critical importance because the presentation, imaging, and pathophysiology of CAD in women are different from that of men. Compared to men, women are more likely to have diffuse non-obstructive epicardial CAD with lower coronary flow reserve (CFR) [17]. Women had fewer calcified lesions and higher plaque density compared to men [18], and women have smaller sized coronary arteries. Therefore, less plaque burden is required to result in flow limiting stenosis [19]. In view of these sex differences in the pathophysiology of CAD, the extrapolation of the findings from these imaging trials to women may not be appropriate.

It has also been established that the treatment pharmacokinetics for women are different from that of men [20], [21]. Despite this, there is continued underrepresentation of women in CV research studies and the results of these studies are often extrapolated to women. This extrapolation may lead to potential harm and greater side effects for women [22]. This underscores that low representation in clinical trials can lead to poor CV outcomes for women.

3. Proposed causes of the underrepresentation of women in clinical trials

Although there is growing awareness, significant gaps persist in sex-specific research and many questions of clinical importance remain unanswered. To discover the basic understanding of this dilemma, we must focus on answering the main question: why are women not participating in trials at the same extent as men? An exploration of the causes of this underrepresentation is not complete without including causes unique to URM women as this population bears the greatest CV mortality among women [5].

A randomized study of patient willingness to participate in CV prevention trials found that men had 15% greater willingness to participate than women [23]. Among the reasons for this gap was the fact that women perceived a greater risk of harm from trial participation. Women had also been shown to take fewer risks than men under stress, and major health-based decisions could certainly be a source of stress [24].

Additionally, financial stability, sociocultural environment, patient education, community engagement as well as the health care system are all important factors influencing CV health in women [25], [26]. These factors also play an important role in decision making when it comes to clinical trial participation [27]. Distrust of the healthcare system and of medical research also negatively impacts the enrollment of URM women [28], [29].

Women are likely more swayed by their surrounding social and family environments [6]. Women may take more time to plan and they may require more sources of input with decisions influenced by friends, family, researchers, or other external influences [6]. They are also more likely to have their decisions influenced by altruistic motivations given that most women are caregivers [6].

Equally important, a lack of awareness, leadership, and engagement on the part of investigators may be a cause of poor enrollment of women in clinical trials [27]. Several recent studies have reviewed female authorship for CV disease clinical trial publications and found that women are significantly underrepresented in clinical trial leadership [27]. Although the proportion of women in trial leadership has increased over the past decade, the upward trend has been slow [27].

4. Proposed solutions for addressing underrepresentation of women in clinic trials

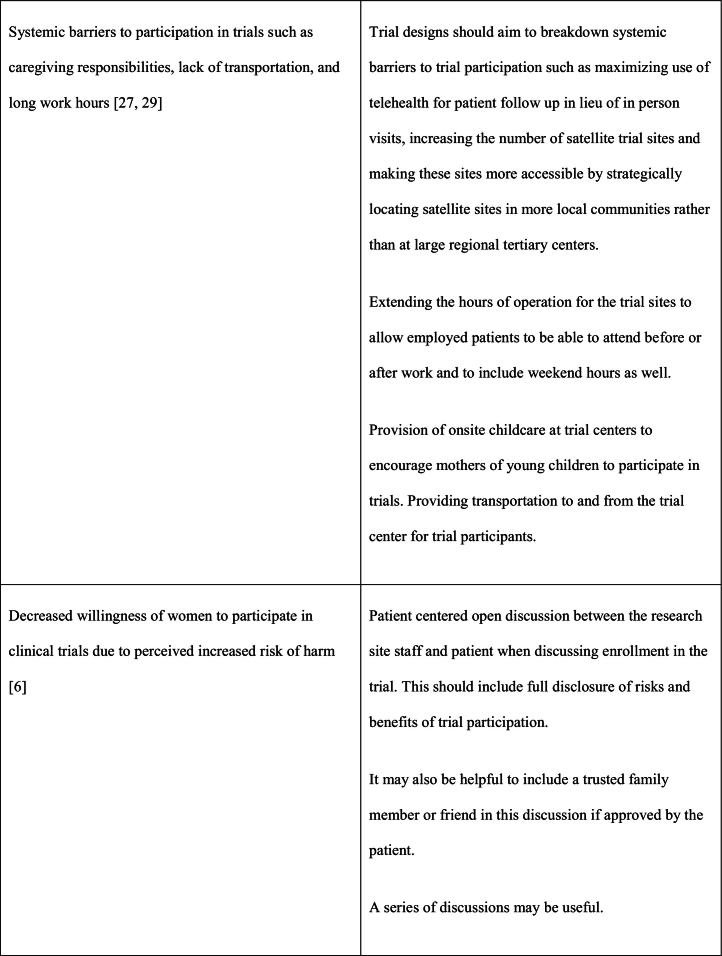

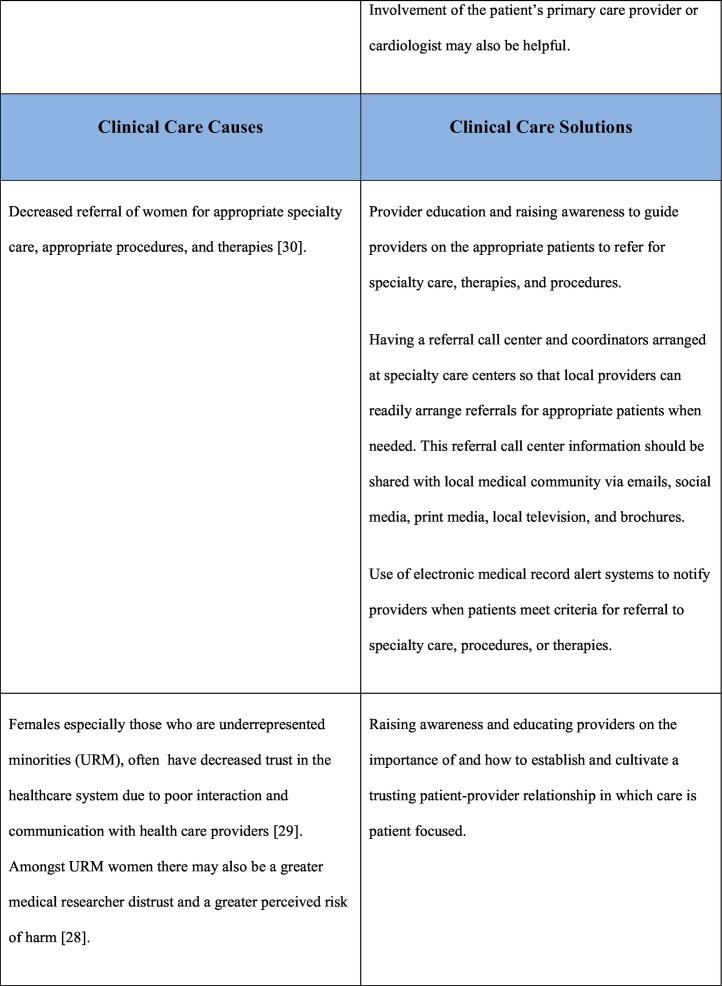

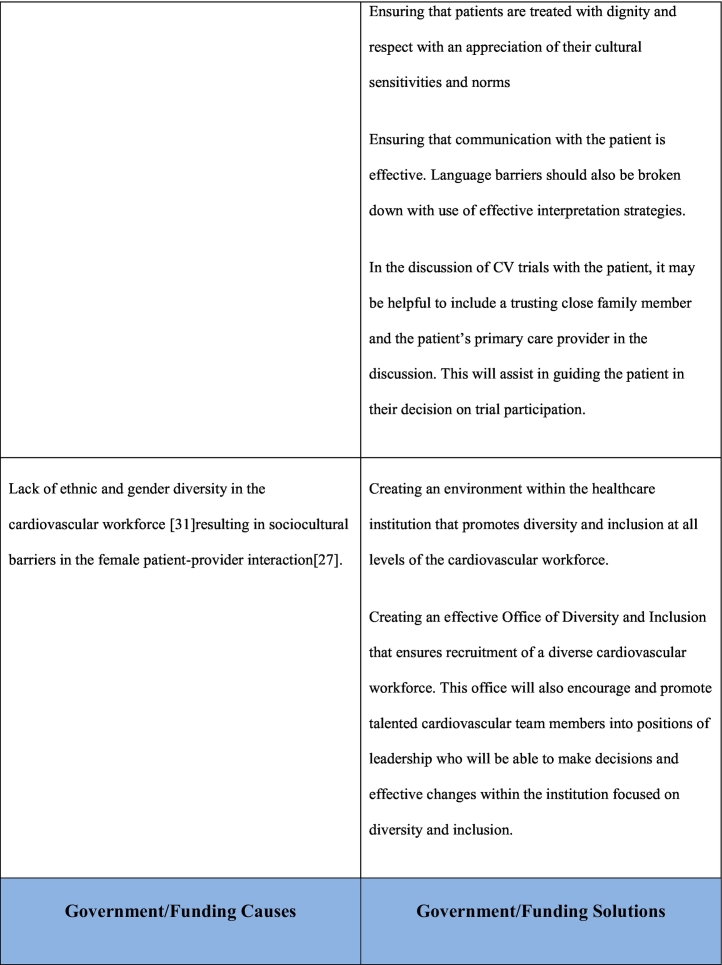

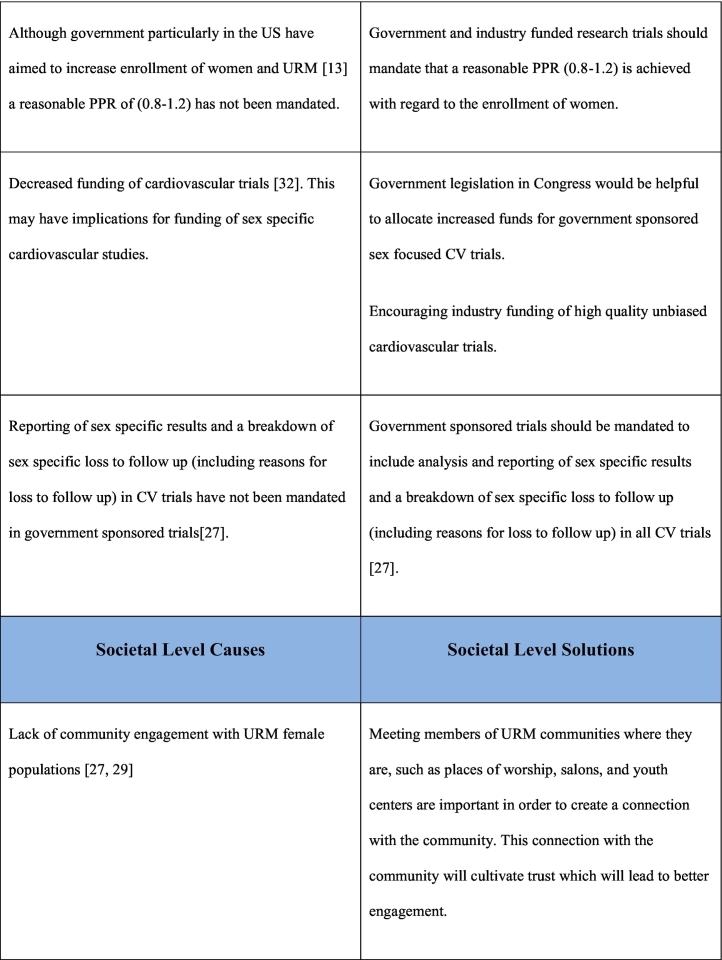

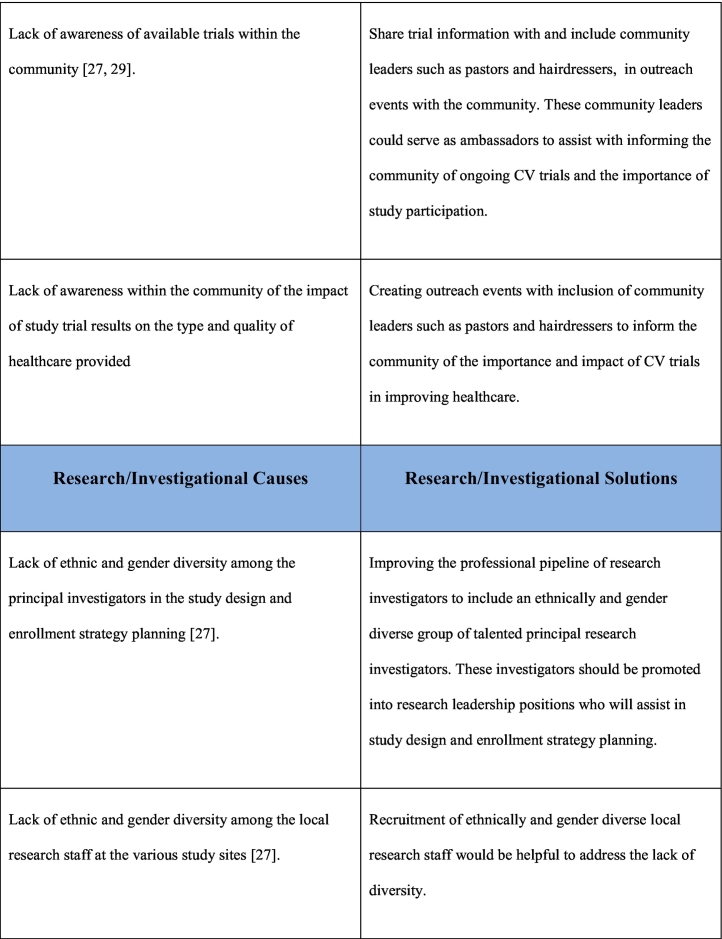

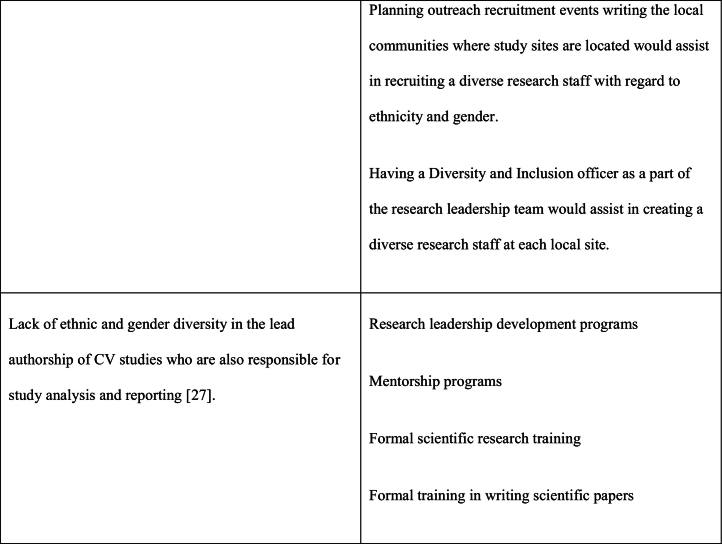

As noted previously, the reasons for underrepresentation of women in clinical trials are multifactorial and addressing this issue will require a multifaceted approach. This multifaceted approach requires interventions at a patient care level, clinical care team level, governmental/funding level, societal level as well as at the level of research investigational leadership and authorship. Table 1 outlines the causes and potential solutions to underrepresentation of women in CV research trials.

Table 1.

5. Conclusion

Underrepresentation of women including URM women in CV trials remains dismally low despite efforts by government organizations to increase the enrollment of women and URM in these trials [6]. This underrepresentation leads to the extrapolation of study results from predominantly male trials to women which have been shown to lead to more side effects and potentially worse outcomes [22]. The causes for the underrepresentation of women in CV trials are multifactorial [6], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]. Therefore addressing these causes should be multifaceted at the levels of the patient, clinical care, government/funding, societal and research study leadership, and authorship.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kardie Tobb-Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing.

Madison Kocher-Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing.

Renee Bullock-Palmer-Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Conceptualization, Resources.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Virani S.S., et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2021 update. Circulation. 2021;143(8):e254–e743. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solimene M.C. Coronary heart disease in women: a challenge for the 21st century. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2010;65(1):99–106. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322010000100015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ezekowitz J.A., et al. Is there a sex gap in surviving an acute coronary syndrome or subsequent development of heart failure? Circulation. 2020;142(23):2231–2239. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim C., et al. A systematic review of gender differences in mortality after coronary artery bypass graft surgery and percutaneous coronary interventions. Clin. Cardiol. 2007;30(10):491–495. doi: 10.1002/clc.20000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heron M. Deaths: leading causes for 2017. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2019;68(6):1–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin X., et al. Women's participation in cardiovascular clinical trials from 2010 to 2017. Circulation. 2020;141(7):540–548. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.043594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douglas P.S., et al. PROspective multicenter imaging study for evaluation of chest pain: rationale and design of the PROMISE trial. Am. Heart J. 2014;167(6):796–803.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CT coronary angiography in patients with suspected angina due to coronary heart disease (SCOT-HEART): an open-label, parallel-group, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9985):2383–2391. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maron D.J., et al. Initial invasive or conservative strategy for stable coronary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(15):1395–1407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang H.J., et al. Coronary atherosclerotic precursors of acute coronary syndromes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018;71(22):2511–2522. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.<collab>Institute of Medicine Board on Population H.and P.Public Health</collab>. National Academies Press (US) Copyright © 2012, National Academy of Sciences; Washington (DC): 2012. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health, in Sex-Specific Reporting of Scientific Research: A Workshop Summary. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinn V.W., et al. Public partnerships for a vision for women's health research in 2020. J. Women's Health (Larchmt) 2010;19(9):1603–1607. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mastroianni A.C., Faden R., Federman D., editors. Institute of Medicine Committee on, E. and S. Legal Issues Relating to the Inclusion of Women in Clinical, in Women and Health Research: Ethical and Legal Issues of Including Women in Clinical Studies. I. National Academies Press (US) Copyright 1994 by the National Academy of Sciences; Washington (DC): 1994. All rights reserved. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weaver W.D., et al. Comparisons of characteristics and outcomes among women and men with acute myocardial infarction treated with thrombolytic therapy.GUSTO-I investigators. JAMA. 1996;275(10):777–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsang W., et al. The impact of cardiovascular disease prevalence on women's enrollment in landmark randomized cardiovascular trials: a systematic review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012;27(1):93–98. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1768-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott P.E., et al. Participation of women in clinical trials supporting FDA approval of cardiovascular drugs. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018;71(18):1960–1969. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taqueti V.R. Sex differences in the coronary system. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018;1065:257–278. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-77932-4_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw L.J., et al. Sex differences in calcified plaque and long-term cardiovascular mortality: observations from the CAC consortium. Eur. Heart J. 2018;39(41):3727–3735. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun R., et al. Culprit plaque characteristics in women vs men with a first ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: in vivo optical coherence tomography insights. Clin. Cardiol. 2017;40(12):1285–1290. doi: 10.1002/clc.22825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosano G.M.C., et al. Gender differences in the effect of cardiovascular drugs: a position document of the working group on pharmacology and drug therapy of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2015;36(40):2677–2680. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Regitz-Zagrosek V. Therapeutic implications of the gender-specific aspects of cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5(5):425–439. doi: 10.1038/nrd2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santema B.T., et al. Identifying optimal doses of heart failure medications in men compared with women: a prospective, observational, cohort study. Lancet. 2019;394(10205):1254–1263. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31792-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding E.L., et al. Sex differences in perceived risks, distrust, and willingness to participate in clinical trials: a randomized study of cardiovascular prevention trials. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007;167(9):905–912. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.9.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mather M., Lighthall N.R. Both risk and reward are processed differently in decisions made under stress. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2012;21(2):36–41. doi: 10.1177/0963721411429452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw L.J., et al. Quality and equitable health care gaps for women: attributions to sex differences in cardiovascular medicine. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017;70(3):373–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghare M.I., et al. Sex disparities in cardiovascular device evaluations: strategies for recruitment and retention of female patients in clinical device trials. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. Intv. 2019;12(3):301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho L., et al. Increasing participation of women in cardiovascular trials. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021;78(7):737–751. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braunstein J.B., et al. Race, medical researcher distrust, perceived harm, and willingness to participate in cardiovascular prevention trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 2008;87(1):1–9. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181625d78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michos E.D., et al. Improving the enrollment of women and racially/ethnically diverse populations in cardiovascular clinical trials: an ASPC practice statement. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021;8 doi: 10.1016/j.ajpc.2021.100250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aggarwal N.R., et al. Sex differences in ischemic heart disease. Circ.Cardiovasc.Qual.Outcomes. 2018;11(2) doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.004437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schnabel R.B., Benjamin E.J. Diversity 4.0 in the cardiovascular health-care workforce. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020;17(12):751–753. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-00462-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nicholls M. Funding of cardiovascular research in the USA: Robert Califf and Peter Libby – speak about cardiovascular research funding in the United States and what the latest trends are with Mark Nicholls. Eur. Heart J. 2018;39(40):3629–3631. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]