Abstract

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), including fluoxetine, are frequently combined with medical psychostimulants such as methylphenidate (Ritalin), for example, in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder/depression comorbidity. Co-exposure to these medications also occurs with misuse of methylphenidate as a recreational drug by patients on SSRIs. Methylphenidate, a dopamine reuptake blocker, produces moderate addiction-related gene regulation. Findings show that SSRIs such as fluoxetine given in conjunction with methylphenidate potentiate methylphenidate-induced gene regulation in the striatum in rats, consistent with a facilitatory action of serotonin on addiction-related processes. These SSRIs may thus increase methylphenidate’s addiction liability. Here, we investigated the effects of a novel SSRI, vilazodone, on methylphenidate-induced gene regulation. Vilazodone differs from prototypical SSRIs in that, in addition to blocking serotonin reuptake, it acts as a partial agonist at the 5-HT1A serotonin receptor subtype. Studies showed that stimulation of the 5-HT1A receptor tempers serotonin input to the striatum. We compared the effects of acute treatment with vilazodone (10–20 mg/kg) with those of fluoxetine (5 mg/kg) on striatal gene regulation (zif268, substance P, enkephalin) induced by methylphenidate (5 mg/kg), by in situ hybridization histochemistry combined with autoradiography. We also assessed the impact of blocking 5-HT1A receptors by the selective antagonist WAY-100635 (0.5 mg/kg) on these responses. Behavioral effects of these drug treatments were examined in parallel in an open-field test. Our results show that, in contrast to fluoxetine, vilazodone did not potentiate gene regulation induced by methylphenidate in the striatum, while vilazodone enhanced methylphenidate-induced locomotor activity. However, blocking 5-HT1A receptors by WAY-100635 unmasked a potentiating effect of vilazodone on methylphenidate-induced gene regulation, thus confirming an inhibitory role for 5-HT1A receptors. Our findings suggest that vilazodone may serve as an adjunct SSRI with diminished addiction facilitating properties and identify the 5-HT1A receptor as a potential therapeutic target to treat addiction.

Keywords: methylphenidate, fluoxetine, vilazodone, psychostimulant, SSRI, striatum, gene expression, zif268

Introduction

Pharmacological treatments in pediatric populations frequently involve psychotropic drugs including psychostimulants (e.g., methylphenidate) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Whereas SSRIs such as fluoxetine are approved for pediatric depressive disorders and are also effective in the treatment of anxiety disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder, and others [1], methylphenidate is widely prescribed for the management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [2, 3]. For example, it was reported that in 2008 approximately 3 million children were treated with psychostimulants including methylphenidate for ADHD in the US alone [4]. ADHD is diagnosed in up to 7% of school-age children in the US [3, 5]. Moreover, further methylphenidate exposure results from widespread misuse of this psychostimulant for recreational purposes (party drug) or as a “cognitive enhancer” by children and students [6–8].

Preclinical research indicates that individual psychotropic medications when used during brain development may induce a variety of maladaptive neuronal changes and increase the risk for drug addiction and other behavioral disorders (for reviews, see [9–12]). However, possible interactions between different drugs have received little attention. This is surprising, as co-exposure to more than one drug is quite common. Thus, methylphenidate and SSRIs are often combined to treat ADHD/depression co-morbidity [13, 14], which occurs in up to 40% of pediatric ADHD cases [15, 16]. Furthermore, methylphenidate plus SSRI combinations are used for a number of other purposes, including to accelerate or augment the effects of SSRIs in the treatment of depression (e.g., [17–20]) or others (e.g., [21]). Unintended co-exposure to these drugs also occurs, for example, in patients on SSRI antidepressants who use methylphenidate recreationally or as a cognitive enhancer. Little is known regarding potential adverse neurobehavioral effects induced by such drug interactions.

The neurochemical effects of methylphenidate and SSRIs, individually, are well understood. SSRIs such as fluoxetine selectively block the serotonin reuptake to produce increased synaptic levels of serotonin. Methylphenidate inhibits the dopamine reuptake, causing dopamine overflow [22], similar to cocaine (reviewed in [23]). However, in contrast to cocaine, methylphenidate does not affect the serotonin reuptake and does not produce serotonin overflow (e.g., [24–26]; see [23]). Therefore, combining methylphenidate with fluoxetine may induce more “cocaine-like” effects by simultaneously inhibiting the reuptake of both dopamine and serotonin.

Psychostimulants such as cocaine alter the expression of hundreds of genes in dopamine target areas including the striatum and nucleus accumbens (e.g., [27–31]), effects that are considered critical for psychostimulant addiction [32]. The psychostimulant methylphenidate has principally similar if more moderate molecular effects (for reviews, see [23, 33]). For example, studies showed that chronic oral methylphenidate treatment in rats produced changes in dopamine transporter and dopamine receptor levels in the striatum (e.g., [34, 35]). Methylphenidate-induced molecular changes are produced by excessive dopamine overflow and are mediated by dopamine receptors in the striatum [36, 37]. However, it is well known that serotonin receptor stimulation facilitates these dopamine-mediated molecular effects in the case of cocaine (for review, see [33]). Thus, inhibition of the serotonin neurotransmission by transmitter depletion or receptor antagonism reduces gene induction by cocaine in the striatum, affecting, for example, transcription factors (immediate-early genes, IEGs) [38–40] and neuropeptides [41–43]. Serotonin is thus an important modulator of psychostimulant-induced neuroplasticity.

Consistent with these earlier findings, a series of studies demonstrated that combining an SSRI (i.e., serotonin action) with methylphenidate potentiates methylphenidate-induced gene regulation in the striatum [12, 33]. For example, the prototypical SSRI fluoxetine was found to potentiate methylphenidate-induced expression of IEGs such as zif268 and c-fos, as well as the expression of the neuropeptides substance P, dynorphin and enkephalin [12], which serve as cell-type markers for drug actions in direct (dynorphin, substance P) vs. indirect (enkephalin) striatal output neurons [33]. Such potentiated gene regulation was also produced by another often prescribed SSRI, citalopram [44].

Our earlier studies used intraperitoneal (i.p.) drug administration, which mimics intermittent high dose exposure that may be encountered during methylphenidate abuse. However, more recent work demonstrated that oral administration (in drinking water) of methylphenidate plus fluoxetine, in doses that produced clinically relevant drug plasma levels [45], also induced potentiated changes in expression of the same genes in the striatum [46]. This oral treatment regimen induced a variety of behavioral changes, including enhanced sucrose consumption and altered anxiolytic- and antidepressant-like effects [47], as well as enhanced cocaine self-administration [48], subsequent to methylphenidate plus fluoxetine treatment in adolescent rats. Similarly, facilitated acquisition of cocaine self-administration after methylphenidate plus fluoxetine pretreatment was also found in a subpopulation of adult rats [49]. These findings thus suggest that methylphenidate plus SSRI combinations may increase the risk for substance use disorder or other neuropsychiatric disorders [12, 50].

In order to mitigate such effects, it is important to understand the underlying mechanisms, that is, the serotonin receptor subtypes that mediate the potentiation of methylphenidate-induced gene regulation by SSRIs. Earlier studies by others [39, 40] and our own [51] have highlighted a contribution of the 5-HT1B receptor in regulating psychostimulant-induced gene expression. For example, stimulation of the 5-HT1B receptor has been shown to enhance cocaine-induced gene regulation in the striatum [39, 40]. This receptor also facilitates methylphenidate-induced behavior [51, 52] and gene regulation [51, 53]. Specifically, our results showed that the selective 5-HT1B receptor agonist CP94253 potentiated methylphenidate-induced expression of the IEGs zif268 and c-fos [51]. However, 5-HT1B receptor stimulation did not affect the induction of the IEG homer1a, which, in contrast, is potentiated by fluoxetine [51]. This latter finding thus indicates that other serotonin receptors are also involved.

In the present study, we investigated a possible role for the 5-HT1A receptor in modulating methylphenidate-induced gene regulation in the striatum. Recent preclinical studies demonstrated that a novel SSRI, vilazodone, is useful in moderating serotonin neuron activity in models of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia [54, 55]. Vilazodone differs from other SSRIs in that, in addition to its action as a serotonin reuptake blocker, it also acts as a partial agonist of the 5-HT1A receptor [56–58]. This 5-HT1A receptor agonism, presumably at the inhibitory 5-HT1A autoreceptor, has been shown to temper activity in serotonin projections to the striatum and attenuate dopamine agonist-induced activity and gene regulation in striatal neurons after L-DOPA treatment [54, 55, 59]. Here, we investigated whether vilazodone would produce less serotonin-related potentiation of methylphenidate-induced gene regulation in the striatum, compared with the effects of the prototypical SSRI fluoxetine. Our results indicate that this is the case and that this effect is indeed mediated by 5-HT1A receptor stimulation.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (five weeks old at the time of the drug treatment; Harlan, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) were housed 2–3 per cage under standard laboratory conditions (12:12 h light/dark cycle, lights on at 07:00; with food and water available ad libitum). Experiments were performed between 13:00–17:00. Prior to the drug treatment, the rats were allowed one week of acclimation during which time they were repeatedly handled. All procedures met the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (National Research Council, 2003) and were approved by the Rosalind Franklin University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Drug Treatment

In experiment 1, rats received an injection of fluoxetine HCl (5 mg/kg, i.p., in 10% Kolliphor EL in 0.02% ascorbic acid; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) (FLX) or vilazodone HCl (10 mg/kg; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) (VIL) or vehicle, followed 15 min later by an injection of methylphenidate HCl (5 mg/kg, in 0.02% ascorbic acid; Sigma-Aldrich) (MP) or vehicle (groups Veh, MP, MP+FLX, MP+VIL and VIL; n=7–11). A separate cohort received an injection of also a higher dose of vilazodone HCl (10 and 20 mg/kg) (VIL10, VIL20) or vehicle, followed 15 min later by an injection of methylphenidate HCl (5 mg/kg) or vehicle (groups Veh, MP, MP+VIL10 and MP+VIL20; n=6–8). Experiment 2 assessed a role for the 5-HT1A receptor in mediating the actions of vilazodone by administration of the 5-HT1A antagonist WAY-100635. Rats received first an injection of WAY-100635 (maleate) (0.5 mg/kg, in 0.02% ascorbic acid; Cayman Chemical) (WAY) or vehicle, followed 15 min later by an injection of vilazodone HCl (10 mg/kg, in 10% Kolliphor EL) or vehicle, followed 15 min later by an injection of methylphenidate HCl (5 mg/kg, in 0.02% ascorbic acid) or vehicle (groups Veh, MP, MP+VIL, MP+VIL+WAY, MP+WAY and WAY; n=5–8). All drugs were given in a volume of 1 ml/kg, and the doses were based on our previous studies (e.g., [44, 53, 55, 59, 60]) and the literature [54]. After the last injection, the rat was placed in an open-field apparatus (43×43 cm), and locomotion (“ambulation” counts) and local repetitive movements (“stereotypy 2” counts) were measured for 40 min with an activity monitoring system (Truscan, Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, Pennsylvania, USA).

Tissue Preparation and In Situ Hybridization Histochemistry

Immediately after the behavioral test, the rats were killed with CO2, and their brain was rapidly removed and frozen in isopentane cooled on dry ice. Brains were stored at −30 °C until cryostat sectioning. Coronal sections (12 μm) were thaw-mounted onto glass slides (Superfrost/Plus, Daigger, Wheeling, IL, USA), dried on a slide warmer and stored at −30 °C. In preparation for in situ hybridization histochemistry, the sections were first fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/0.9% saline for 10 min at room temperature, and then incubated in a fresh solution of 0.25% acetic anhydride in 0.1 M triethanolamine/0.9% saline (pH 8.0) for 10 min, dehydrated, defatted for 2 × 5 min in chloroform, rehydrated, and air-dried. The slides were stored at −30 °C until hybridization.

In situ hybridization histochemistry was performed as described before [53, 61]. Oligonucleotide probes (48-mers; Invitrogen, Rockville, MD, USA) were labeled with [35S]-dATP. The probes had the following sequence: zif268 (NGFI-A, EGR-1), complementary to bases 352–399, GenBank accession number M18416; substance P, bases 128–175, X56306; and enkephalin, bases 436–483, M28263. Hybridization and washing procedures were as reported [53, 61]. One hundred μl of hybridization buffer containing labeled probe (~3 × 106 cpm) was added to each slide. The sections were coverslipped and incubated at 37 °C overnight. After incubation, the slides were first rinsed in four washes of 1X saline citrate (150 mM sodium chloride, 15 mM sodium citrate), and then washed 3 times 20 min each in 2X saline citrate/50% formamide at 40 °C, followed by 2 washes of 30 min each in 1X saline citrate at room temperature. After a brief water rinse, the sections were air-dried and then apposed to X-ray film (BioMax MR-2, Kodak) for 4–12 days.

Analysis of Autoradiograms

Gene expression in the striatum was assessed in sections from three rostrocaudal levels: “rostral” (approximately +1.6 mm relative to bregma; [62]), “middle” (+0.4) and “caudal” (−0.8), in a total of 23 sectors [61, 63]. These sectors are mostly defined by their predominant cortical inputs and thus reflect different functional domains (see [61, 63]).

Hybridization signals on film autoradiograms were measured by densitometry (NIH Image; Wayne Rasband, NIMH, Bethesda, MD, USA), as described [53]. Experimenters were blinded to the treatment when performing the image analysis. The “mean density” value of a region of interest was measured by placing a template over the captured image. Mean densities were corrected for background by subtracting mean density values measured over white matter (corpus callosum). Values from corresponding regions in the two hemispheres were then averaged. The illustrations of film autoradiograms depicted are computer-generated images and are contrast-enhanced, with all images manipulated equally. Maximal hybridization signal is black.

Statistics

Treatment effects were determined by one-factor ANOVA (Prism 9, GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Newman-Keuls post hoc tests were used to describe differences between individual groups.

Results

Effects of Vilazodone vs. Fluoxetine on Methylphenidate-Induced Gene Expression in the Striatum and Behavior

Figure 1A presents drug-induced changes in zif268 expression in the 6 sectors of the middle striatum. Examples of film autoradiograms showing zif268 expression in the middle striatum are depicted in Figure 2A. Figure 2B shows maps illustrating the spread of drug effects on zif268 expression across the 23 sectors in the rostral, middle and caudal striatum. Methylphenidate (5 mg/kg) significantly increased zif268 mRNA levels, compared with vehicle controls (MP vs. Veh, P<0.05), in 14 of the 23 striatal sectors, spanning the rostrocaudal extent of the striatum. Combining fluoxetine (5 mg/kg) with methylphenidate produced significantly increased zif268 expression in 16 sectors (MP+FLX vs. Veh, P<0.05). In 8 of these sectors, zif268 expression was significantly greater after methylphenidate plus fluoxetine treatment than after methylphenidate-only treatment (potentiation) (MP+FLX vs. MP, P<0.05) (Fig. 2B). These effects were most robust in the middle striatum, which displayed potentiated zif268 expression in 5 of the 6 sectors (Fig. 1A). In contrast, we previously demonstrated that this dose of fluoxetine (5 mg/kg) given alone has no effects on striatal gene expression (e.g., zif268, substance P, enkephalin; e.g., [44, 60]).

Figure 1.

Effects of methylphenidate plus vilazodone vs. methylphenidate plus fluoxetine treatment on zif268 and substance P expression in the striatum and behavior. (A, B) Mean density values (mean±SEM, in % of MP) measured in the six sectors (zif268; A) or the three dorsal sectors (substance P; B) of the middle striatum (see diagram, lower right) are given for the groups that received an injection of vehicle (Veh), methylphenidate (5 mg/kg) (MP), methylphenidate plus fluoxetine (5 mg/kg) (MP+FLX), methylphenidate plus vilazodone (10 mg/kg) (MP+VIL) or vilazodone alone (VIL) (n=7–11). (C) Ambulation counts (mean±SEM, in % of MP) in the 40-min open-field test are shown for these treatment groups. Sector abbreviations: m, medial; d, dorsal; dl, dorsolateral; vl, ventrolateral; c, central; v, ventral. *** P<0.001, ** P<0.01, * P<0.05, vs. MP; ### P<0.001, ## P<0.01, # P<0.05, as indicated.

Figure 2.

Effects of methylphenidate plus vilazodone vs. methylphenidate plus fluoxetine treatment, as well as effects of the 5-HT1A antagonist WAY-100635, on zif268 expression in the striatum. (A) Illustrations of film autoradiograms show zif268 expression in the mid-level striatum in rats that received (from upper left) vehicle (Veh), methylphenidate (5 mg/kg) (MP), methylphenidate plus fluoxetine (5 mg/kg) (MP+FLX), vilazodone (10 mg/kg) (VIL), methylphenidate plus vilazodone (MP+VIL), WAY-100635 (0.5 mg/kg) (WAY), methylphenidate plus WAY-100635 (MP+WAY), or methylphenidate plus vilazodone plus WAY-100635 (MP+VIL+WAY). The maximal hybridization signal is black. (B) Maps depict the regional distribution of increases in zif268 expression across the 23 sectors on the rostral, middle and caudal striatal levels. Shown are the increases (vs. the MP group) in the MP+FLX or MP+VIL groups (potentiation) (experiment 1, left) and the increases (vs. the MP group) in the MP+VIL or MP+VIL+WAY groups (experiment 2, right). The data are expressed relative to the maximal increase observed in each experiment (% of max.). Sectors with a statistically significant difference vs. MP controls (P<0.05) are coded as indicated. Sectors without significant effect are in white.

Similar to fluoxetine alone, vilazodone (10 mg/kg) alone had no effect on zif268 expression (VIL vs. Veh, P<0.05, 0/23 sectors). Moreover, in marked contrast to fluoxetine, vilazodone added to methylphenidate had minimal or no effects on methylphenidate-induced zif268 expression (MP+VIL vs. MP, P<0.05, 3/23 sectors; 1/6 sectors of the middle striatum) (Figs. 1A and 2A and B).

Drug-induced changes in the expression of substance P (Fig. 1B), a direct pathway marker, and enkephalin, an indirect pathway marker, were also assessed. In contrast, to the robust effects on zif268 expression (see above), borderline significant effects were seen for substance P; however, these changes mimicked the patterns of zif268 changes (Fig. 1B), consistent with our earlier findings showing that methylphenidate plus fluoxetine treatment had similar but weaker effects on substance P than on zif268 expression. Methylphenidate (5 mg/kg) alone produced a tendency for increased substance P expression that reached borderline statistical significance only in 2 (caudal) sectors (MP vs. Veh controls, P<0.05) (not shown). Combining fluoxetine with methylphenidate produced significantly increased substance P expression in 5 sectors on 3 levels (MP+FLX vs. Veh, P<0.05) (Fig. 1B). Vilazodone alone had no significant effect on substance P expression (VIL vs. Veh, P<0.05, 0/23 sectors). Similarly, neither fluoxetine nor vilazodone had a statistically significant effect on methylphenidate-induced substance P expression (MP+FLX or MP+VIL vs. MP, P<0.05, 0/23 sectors) (Fig. 1B).

No significant drug-induced increases in enkephalin expression were seen, with the exception of a borderline effect in the middle central sector after methylphenidate treatment (MP vs. Veh, P<0.05, 1/23 sectors) (not shown), also consistent with earlier findings [60].

The behavioral effects of these drug treatments were assessed in an open-field test. These effects overall mirrored those on zif268 expression, with one important exception (Fig. 1A vs. C). Methylphenidate treatment significantly increased locomotor activity (ambulation) (MP vs. Veh, P<0.001) (Fig. 1C), and this effect was also potentiated by adding fluoxetine (MP+FLX vs. MP, P<0.001). However, in contrast to gene expression, vilazodone enhanced methylphenidate-induced locomotion to a similar degree as fluoxetine (MP+VIL vs. MP, P<0.01), while by itself, vilazodone had no significant effect on locomotion (VIL vs. Veh, P>0.05).

To further clarify the impact of vilazodone on gene expression and behavior, the effects of a higher dose (20 mg/kg; VIL20) were also assessed in a separate study (Tab. 1). Our results showed that neither 10 mg/kg nor 20 mg/kg of vilazodone had a significant effect on methylphenidate-induced zif268 expression (MP+VIL10 or MP+VIL20 vs. MP, P<0.05, 0/23 sectors) (Tab. 1) or substance P expression (not shown) in the striatum. Again, in contrast to gene expression, vilazodone produced a dose-dependent potentiation of methylphenidate-induced locomotor activity (MP+VIL20 vs. MP, P<0.01) (Tab. 1).

Table 1.

Effects of methylphenidate plus vilazodone vs. methylphenidate treatment on zif268 expression in the striatum and behavior.

| A) Expression of zif268 mRNA in striatum (% MP) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veh | MP | MP+VIL10 | MP+VIL20 | |

|

|

||||

| m | 54.7±3.0*** | 100.0±4.6 | 86.4±3.7 | 87.7±2.5 |

| d | 51.0±1.5*** | 100.0±3.7 | 91.6±2.6 | 88.5±2.0 |

| dl | 47.0±2.6*** | 100.0±5.6 | 92.7±7.9 | 91.4±4.6 |

| vl | 42.9±2.5*** | 100.0±8.6 | 89.3±8.2 | 85.9±7.6 |

| c | 45.1±2.1*** | 100.0±6.1 | 81.7±1.4 | 80.2±8.6 |

| v | 88.8±5.7 | 100.0±8.6 | 104.8±10.1 | 94.6±6.1 |

| B) Ambulation (% MP) | ||||

| Veh | MP | MP+VIL10 | MP+VIL20 | |

|

|

||||

| 17.7±2.0** | 100.0±13.1 | 149.2±24.3 | 199.3±30.8** | |

(A) Mean density values (mean±SEM, in % of MP) measured in the six sectors of the middle striatum (see diagram, Fig. 1) are given for the groups that received an injection of vehicle (Veh), methylphenidate (5 mg/kg) (MP), or methylphenidate plus vilazodone (10 or 20 mg/kg) (MP+VIL10, MP+VIL20) (n=6–8). (B) Ambulation counts (mean±SEM, in % of MP) in the 40-min open-field test are shown for these treatment groups. Sector abbreviations: m, medial; d, dorsal; dl, dorsolateral; vl, ventrolateral; c, central; v, ventral.

P<0.001

P<0.01, vs. MP.

The 5-HT1A Receptor Dampens the Effects of Vilazodone on Methylphenidate-Induced Gene Expression in the Striatum and Behavior

Figure 3A displays the influence of the 5-HT1A receptor antagonist WAY-100635 on vilazodone-induced changes in zif268 expression in the middle striatum. Examples of film autoradiograms illustrating these effects are given in Figure 2A. Methylphenidate (5 mg/kg) significantly increased zif268 expression in 15 of the 23 sectors (MP vs. Veh, P<0.05). Combining vilazodone (10 mg/kg) with methylphenidate produced a similar effect (MP+VIL vs. Veh, P<0.05, 14/23 sectors); that is, again vilazodone did not potentiate methylphenidate-induced zif268 expression (MP+VIL vs. MP, P<0.05, 0/23 sectors) (Fig. 2B).

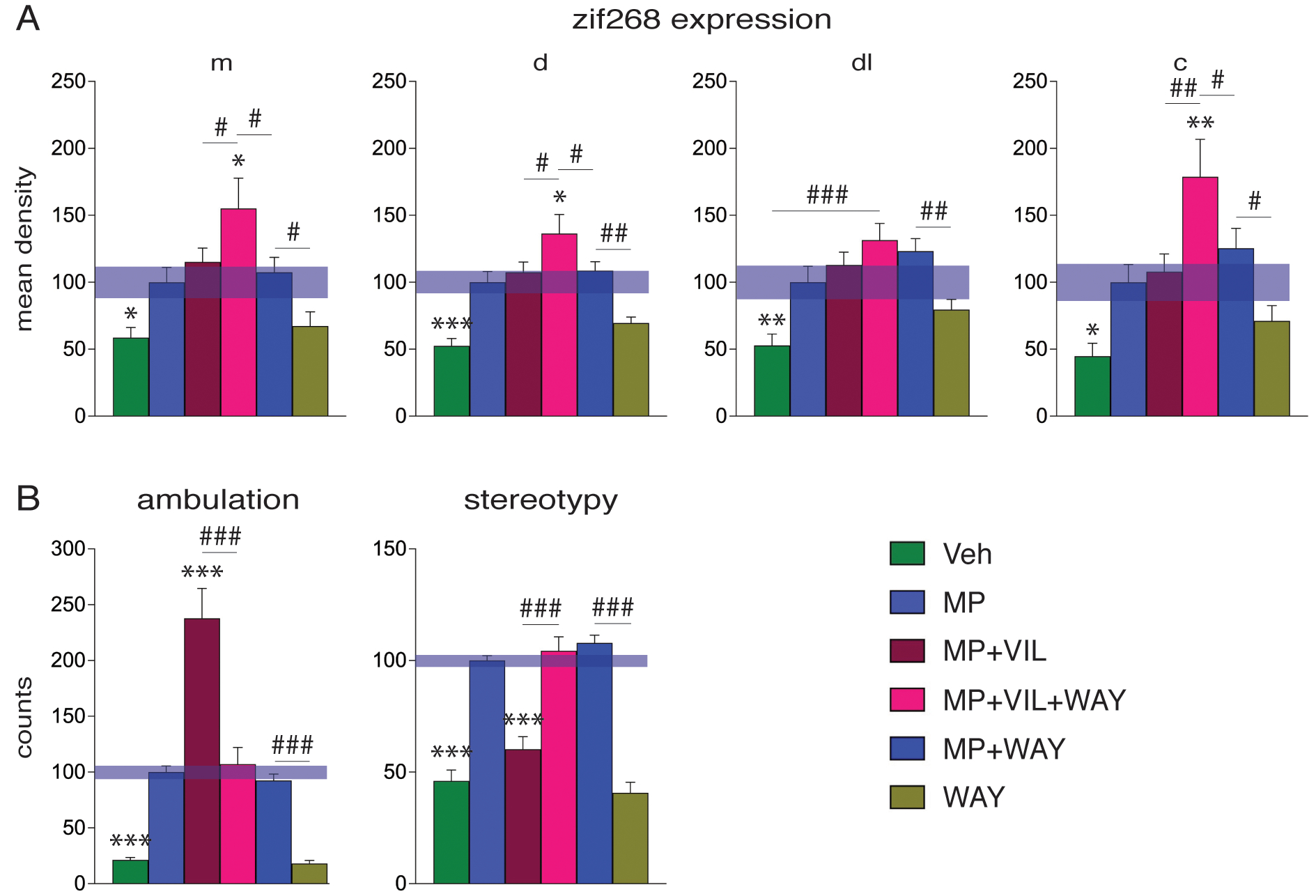

Figure 3.

Effects of blocking the 5-HT1A receptor by the selective 5-HT1A antagonist WAY-100635 on methylphenidate plus vilazodone-induced zif268 expression in the striatum and behavior. (A) Mean density values (mean±SEM, in % of MP) measured in four sectors of the middle striatum (see diagram, Fig. 1) are shown for the groups that received an injection of vehicle (Veh), methylphenidate (5 mg/kg) (MP), methylphenidate plus vilazodone (10 mg/kg) (MP+VIL), methylphenidate plus vilazodone plus WAY-100635 (0.5 mg/kg) (MP+VIL+WAY), methylphenidate plus WAY-100635 (MP+WAY), or WAY-100635 (WAY) (n=5–8). (B) Ambulation (left) and stereotypy counts (right) (mean±SEM, in % of MP) in the open-field test are given for these treatment groups. Abbreviations: m, medial; d, dorsal; dl, dorsolateral; c, central. *** P<0.001, ** P<0.01, * P<0.05, vs. MP; ### P<0.001, ## P<0.01, # P<0.05, as indicated.

In contrast, blocking 5-HT1A with WAY-100635 given in conjunction with vilazodone treatment did produce increased gene expression (Figs. 2 and 3A). Thus, adding WAY-100635 to vilazodone potentiated methylphenidate-induced zif268 expression [MP+VIL+WAY vs. Veh, P<0.05, 18/23 sectors; MP+VIL+WAY vs. MP, P<0.05, 9/23 sectors (Fig. 2B); MP+VIL+WAY vs. MP+VIL, P<0.05, 9/23 sectors; MP+VIL+WAY vs. MP+WAY, P<0.05, 6/23 sectors]. This effect of WAY-100635 was seen on all three rostrocaudal levels (Fig. 2B). Finally, WAY-100635 given alone did produce a tendency for increased zif268 expression in some sectors, which, however, was statistically significant only in one or two sectors (WAY vs. Veh, P<0.05, 1/23 sectors; MP+WAY vs. MP, P<0.05, 2/23 sectors) (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Effects of blocking the 5-HT1A receptor by the selective 5-HT1A antagonist WAY-100635 on methylphenidate plus vilazodone-induced substance P (A) and enkephalin (B) expression in the striatum. Mean density values (mean±SEM, in % of MP) measured in four sectors of the middle striatum are given for the groups that received vehicle (Veh), methylphenidate (MP), methylphenidate plus vilazodone (MP+VIL), methylphenidate plus vilazodone plus WAY-100635 (MP+VIL+WAY), methylphenidate plus WAY-100635 (MP+WAY), or WAY-100635 only (WAY). Abbreviations: m, medial; d, dorsal; dl, dorsolateral; c, central. * P<0.05, vs. MP; ### P<0.001, ## P<0.01, # P<0.05, as indicated.

Again, similar but weaker effects were seen for substance P, but not enkephalin (Fig. 4). Methylphenidate significantly increased substance P expression in 7 of the 23 sectors (MP vs. Veh, P<0.05). Adding vilazodone (10 mg/kg) to methylphenidate produced a similar effect (MP+VIL vs. Veh, P<0.05, 5/23 sectors); that is, vilazodone did not potentiate methylphenidate-induced substance P expression (MP+VIL vs. MP, P<0.05, 0/23 sectors) (Fig. 4A).

Blocking 5-HT1A with WAY-100635 given in conjunction with vilazodone treatment, in contrast, did modestly facilitate substance P expression in a few sectors (MP+VIL+WAY vs. Veh, P<0.05, 8/23 sectors; MP+VIL+WAY vs. MP, P<0.05, 2/23 sectors; MP+VIL+WAY vs. MP+VIL, P<0.05, 1/23 sectors; MP+VIL+WAY vs. MP+WAY, P<0.05, 1/23 sectors) (Fig. 4A). Finally, WAY-100635 alone did also produce borderline increases in substance P expression in some (rostral) sectors (WAY vs. Veh, P<0.05, 5/23 sectors; MP+WAY vs. MP, P<0.05, 1/23 sectors) (not shown). In contrast to substance P, no significant drug-induced changes in enkephalin expression were seen (Fig. 4B).

The behavioral effects of these drug treatments were again assessed in the open-field test (Fig. 3B). Methylphenidate treatment significantly increased locomotor activity (ambulation) (MP vs. Veh, P<0.001), and this effect was potentiated by adding vilazodone (MP+VIL vs. MP, P<0.001). WAY-100635 given in conjunction with vilazodone plus methylphenidate blocked the vilazodone-induced potentiation of locomotion (MP+VIL+WAY vs. MP+VIL, P<0.001; MP+VIL+WAY vs. MP, P>0.05) (Fig. 3B). WAY-100635 given alone had no significant effect on locomotion (WAY vs. Veh, P>0.05). This blocking effect by WAY-100635 was also discernible in local repetitive movements (“stereotypy 2” counts) (Fig. 3B). Methylphenidate also significantly increased the number of local repetitive movements (MP vs. Veh, P<0.001). As vilazodone potentiated forward locomotion, the number of local repetitive movements decreased (MP+VIL vs. MP, P<0.001) to levels seen in vehicle controls (MP+VIL vs. Veh, P>0.05). WAY-100635 blocked this vilazodone effect. Thus, in animals treated with methylphenidate plus vilazodone plus WAY-100635, the levels of local movements returned to the levels present in animals treated with methylphenidate-only (MP+VIL+WAY vs. MP, P>0.05; MP+VIL+WAY vs. MP+VIL, P<0.001), or methylphenidate plus WAY-100635 (MP+VIL+WAY vs. MP+WAY, P>0.05) (Fig. 3B). WAY-100635 given alone had no significant effect on local repetitive movements (WAY vs. Veh, P>0.05).

Discussion

The goals of the present study were to compare the impact of the novel SSRI vilazodone on methylphenidate-induced gene regulation and behavior with that of the prototypical SSRI fluoxetine and assess the role of the 5-HT1A receptor in the vilazodone-induced effects. Our results demonstrate that, in contrast to fluoxetine, vilazodone had minimal or no effects on methylphenidate-induced gene regulation (i.e., zif268, substance P) in the striatum, while both vilazodone and fluoxetine enhanced methylphenidate-induced locomotor activity. In addition, blocking 5-HT1A receptors by the selective antagonist WAY-100635 unmasked a potentiating effect of vilazodone on methylphenidate-induced gene regulation and reversed the vilazodone effects on behavior.

Effects of Vilazodone versus Fluoxetine on Methylphenidate-Induced Gene Regulation and Behavior

Our previous work demonstrated that combining an SSRI, fluoxetine or citalopram, with methylphenidate treatment potentiated gene regulation by methylphenidate in the striatum [12, 33]. These studies used intermediate SSRI doses, typically 5 mg/kg, which by themselves had no effect on striatal gene regulation (e.g., [44, 53, 60, 64]). For acute and repeated treatments, we often monitored IEGs such as zif268 as gene markers to demonstrate such drug interactions. These studies showed, for example, greater induction of zif268 after acute methylphenidate plus fluoxetine treatment, but also altered regional patterns of gene induction, with the most robust effects seen in the lateral (sensorimotor) striatum, in addition to effects in the central and medial (associative) striatum. These effects of methylphenidate plus fluoxetine treatment thus better mimicked the molecular changes induced by cocaine than those of methylphenidate alone [12, 33]. Acute and repeated treatment with methylphenidate plus fluoxetine also produced potentiated increases in the expression of substance P and dynorphin [12], with more modest or no changes in enkephalin expression, indicating that, similar to other psychostimulants, the direct striatal output pathway was preferentially altered by these drug treatments [12, 33]. Overall, these findings suggest that prototypical SSRIs such as fluoxetine when given in combination with methylphenidate may increase the addiction risk for methylphenidate (see [12, 33]).

The present study investigated and compared the impact of the novel SSRI vilazodone on methylphenidate-induced gene regulation in the striatum. Vilazodone, an SSRI that was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2011 [65], has recently received attention as a potential therapeutic for L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia, which is produced by excessive dopamine action in the striatum. It is held that, in late-stage Parkinson’s disease, L-DOPA-derived dopamine is largely released from striatal serotonin terminals [66–68] and that such unregulated, massive dopamine release is responsible for changes in striatal gene regulation and L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia [69, 70]. A variety of studies have thus investigated the utility of pharmacological modulation of the serotonin neurotransmission, including the use of SSRIs and serotonin receptor agonists, in order to attenuate such abnormal dopamine release and L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia (for reviews, see [68, 71]). Several recent studies in animal models showed that treatment with vilazodone attenuates development and expression of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia [54, 55, 59, 72], as well as L-DOPA-induced gene regulation in the striatum [54, 55], effects that are thought to reflect attenuated activity in serotonin neurons and dopamine release therefrom [54, 73].

Our present study shows that even high doses [54] of vilazodone, in contrast to fluoxetine, failed to significantly potentiate methylphenidate-induced gene regulation in the striatum. We first assessed the effects of 10 mg/kg vilazodone. This dose significantly attenuated L-DOPA-induced gene regulation (zif268, dynorphin) in striatal direct pathway neurons [55], consistent with reduced activity in serotonin projections to the striatum [73]. To ascertain that the lack of an effect on methylphenidate-induced gene regulation was not due to a too low vilazodone dose, we also assessed a higher dose (20 mg/kg; [54]), which also failed to potentiate methylphenidate-induced gene regulation. In contrast to gene regulation, these same doses of vilazodone, however, did facilitate methylphenidate-induced locomotor activity in a dose-dependent manner (present results), similar to the effects of fluoxetine (present results; [52]). These findings thus indicate that vilazodone has a lesser impact on striatal gene regulation than SSRIs such as fluoxetine, while maintaining (some) SSRI effects on dopamine-mediated behavior.

Mechanisms Underlying Vilazodone’s more Moderate Effects

In our present study, we further investigated the serotonin receptor subtypes that mediate the SSRI potentiation of methylphenidate-induced gene regulation in the striatum. There are at least 14 serotonin receptor subtypes, some of which are expressed in serotonin neurons (5-HT1A) and/or in striatal neurons themselves [74, 75]. Thus, there are likely multiple and complex mechanisms by which serotonin can modulate the molecular effects of dopamine action in striatal neurons.

Previous work assessed the mechanisms by which SSRIs impact dopamine agonist-induced striatal activity and behavior. For example, the 5-HT1B receptor was found to contribute to the facilitating effects of fluoxetine on methylphenidate-induced locomotion [52]. Moreover, both 5-HT1B and 5-HT1A receptors participate in SSRI effects on L-DOPA-induced striatal activity and behavior (e.g., [54, 59, 76]). Thus, our previous results confirmed a role for the 5-HT1A receptor in the inhibitory effects of vilazodone on L-DOPA-induced aberrant striatal activity and dyskinesia [59], as these effects were reversed by the selective 5-HT1A receptor antagonist WAY-100635 [54, 59]. We here show that blocking 5-HT1A receptors with the same dose of WAY-100635 (0.5 mg/kg) also reverses vilazodone effects on methylphenidate-induced behavior and gene regulation. Specifically, blocking 5-HT1A receptors inhibited vilazodone-induced facilitation of locomotor activity and unmasked a potentiating effect of vilazodone on methylphenidate-induced gene expression, as indicated by the gene markers zif268 and substance P, but not enkephalin. The latter finding indicates a preferential effect on the direct pathway, similar to other psychostimulants (e.g., [23, 33, 77]).

These findings are consistent with a moderating influence of vilazodone (compared to fluoxetine) on serotonin input to the striatum via stimulation of inhibitory 5-HT1A autoreceptors [73]. Nevertheless, our drugs were administered systemically, which precludes conclusions as to their sites of action. Given the wide distribution of serotonin receptors throughout the forebrain, indirect effects via 5-HT1A heteroreceptors on other neurons, for example, on corticostriatal neurons [71], could have contributed to some of the observed effects. Corticostriatal inputs are powerful regulators of dopamine-mediated gene regulation in the striatum [78]. However, the lack of effects on enkephalin expression seems to argue against a major contribution of altered cortical inputs to the observed striatal effects. Enkephalin expression is sensitive to cortical inputs (see [78], for discussion), yet none of our treatments had an effect on enkephalin expression, consistent with a lack of effects of vilazodone on striatal enkephalin expression in the L-DOPA model [55]. Given that enkephalin expression is more affected by chronic treatments (cf. [55, 78]), further work with repeated drug treatments and/or other gene markers for indirect pathway neurons [78] will be necessary to ascertain a potential effect (or lack thereof) for vilazodone on the indirect pathway with methylphenidate treatment.

Conclusions

SSRIs such as fluoxetine when given in combination with the medical psychostimulant methylphenidate potentiate addiction-related gene regulation by methylphenidate and facilitate subsequent acquisition of cocaine self-administration in rats. These SSRIs may thus enhance the addiction liability of methylphenidate. Our present results show that vilazodone, a novel SSRI that also acts as a partial agonist at the inhibitory 5-HT1A receptor, has a significantly diminished potential to increase methylphenidate-induced gene regulation in the striatum compared with the SSRI fluoxetine. Moreover, we demonstrate that this diminished effect is mediated by vilazodone’s 5-HT1A agonist properties, as blocking the 5-HT1A receptor increased the impact of vilazodone on gene regulation to levels similar to those of fluoxetine. In as far as such gene regulation underlies the risk of psychostimulant addiction, our findings indicate that the novel SSRI vilazodone may be a better adjunct medication for methylphenidate treatment, as it appears to entail a lower risk for addiction-related gene regulation. Moreover, our results identify the 5-HT1A receptor as a potential pharmaceutical target to mitigate the addiction risk.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant DA046794.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant DA046794.

Footnotes

Competing Interests The authors have no conflicts of interest or relevant financial interests to declare.

Ethics Approval All experimental procedures met the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (National Research Council, 2003) and were approved by the Rosalind Franklin University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Consent to Participate Not applicable

Consent to Publish Not applicable

Data Availability

The data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Iversen L (2006) Neurotransmitter transporters and their impact on the development of psychopharmacology. Br J Pharmacol 147 Suppl 1:S82–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castle L, Aubert RE, Verbrugge RR, Khalid M, Epstein RS (2007) Trends in medication treatment for ADHD. J Atten Disord 10:335–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kollins SH (2008) ADHD, substance use disorders, and psychostimulant treatment: current literature and treatment guidelines. J Atten Disord 12:115–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swanson JM, Wigal TL, Volkow ND (2011) Contrast of medical and nonmedical use of stimulant drugs, basis for the distinction, and risk of addiction: comment on Smith and Farah (2011). Psychol Bull 137:742–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DSMMD, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. 2000, Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- 6.SAMHSA (2015) Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH Series H-50, HHS Publication No (SMA) 15–4927 https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR1-2014/NSDUH-FRR1-2014.pdf: [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benson K, Flory K, Humphreys KL, Lee SS (2015) Misuse of stimulant medication among college students: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 18:50–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Compton WM, Han B, Blanco C, Johnson K, Jones CM (2018) Prevalence and correlates of prescription stimulant use, misuse, use disorders, and motivations for misuse among adults in the United States. Am J Psychiatry 175:741–755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlezon WAJ, Konradi C (2004) Understanding the neurobiological consequences of early exposure to psychotropic drugs: linking behavior with molecules. Neuropharmacology 47:47–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrey N, Wilkinson M (2011) A review of psychostimulant-induced neuroadaptation in developing animals. Neurosci Bull 27:197–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marco EM, Adriani W, Ruocco LA, Canese R, Sadile AG, Laviola G (2011) Neurobehavioral adaptations to methylphenidate: the issue of early adolescent exposure. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 35:1722–1739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Waes V, Steiner H (2015) Fluoxetine and other SSRI antidepressants potentiate addiction-related gene regulation by psychostimulant medications. In: Pinna G (eds) Fluoxetine: Pharmacology, Mechanisms of Action and Potential Side Effects. Nova Science Publishers, Hauppauge, NY, pp. 207–225 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rushton JL, Whitmire JT (2001) Pediatric stimulant and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor prescription trends: 1992 to 1998. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 155:560–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safer DJ, Zito JM, DosReis S (2003) Concomitant psychotropic medication for youths. Am J Psychiatry 160:438–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waxmonsky J (2003) Assessment and treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children with comorbid psychiatric illness. Curr Opin Pediatr 15:476–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spencer TJ (2006) ADHD and comorbidity in childhood. J Clin Psychiatry 67 Suppl 8:27–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavretsky H, Kim MD, Kumar A, Reynolds CF (2003) Combined treatment with methylphenidate and citalopram for accelerated response in the elderly: an open trial. J Clin Psychiatry 64:1410–1414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson JC (2007) Augmentation strategies in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Recent findings and current status of augmentation strategies. CNS Spectr 12 Suppl 22:6–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishii M, Tatsuzawa Y, Yoshino A, Nomura S (2008) Serotonin syndrome induced by augmentation of SSRI with methylphenidate. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 62:246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ravindran AV, Kennedy SH, O’Donovan MC, Fallu A, Camacho F, Binder CE (2008) Osmotic-release oral system methylphenidate augmentation of antidepressant monotherapy in major depressive disorder: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 69:87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Csoka A, Bahrick A, Mehtonen OP (2008) Persistent sexual dysfunction after discontinuation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Sex Med 5:227–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Logan J, Franceschi D, Maynard L, Ding YS, Gatley SJ, Gifford A, Zhu W, Swanson JM (2002) Relationship between blockade of dopamine transporters by oral methylphenidate and the increases in extracellular dopamine: therapeutic implications. Synapse 43:181–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yano M, Steiner H (2007) Methylphenidate and cocaine: the same effects on gene regulation? Trends Pharmacol Sci 28:588–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan D, Gatley SJ, Dewey SL, Chen R, Alexoff DA, Ding YS, Fowler JS (1994) Binding of bromine-substituted analogs of methylphenidate to monoamine transporters. Eur J Neurosci 264:177–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuczenski R, Segal DS (1997) Effects of methylphenidate on extracellular dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine: comparison with amphetamine. J Neurochem 68:2032–2037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Segal DS, Kuczenski R (1999) Escalating dose-binge treatment with methylphenidate: role of serotonin in the emergent behavioral profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 291:19–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berke JD, Paletzki RF, Aronson GJ, Hyman SE, Gerfen CR (1998) A complex program of striatal gene expression induced by dopaminergic stimulation. J Neurosci 18:5301–5310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuferov V, Kroslak T, Laforge KS, Zhou Y, Ho A, Kreek MJ (2003) Differential gene expression in the rat caudate putamen after “binge” cocaine administration: advantage of triplicate microarray analysis. Synapse 48:157–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuferov V, Nielsen D, Butelman E, Kreek MJ (2005) Microarray studies of psychostimulant-induced changes in gene expression. Addict Biol 10:101–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Black YD, Maclaren FR, Naydenov AV, Carlezon WAJ, Baxter MG, Konradi C (2006) Altered attention and prefrontal cortex gene expression in rats after binge-like exposure to cocaine during adolescence. J Neurosci 26:9656–9665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heiman M, Schaefer A, Gong S, Peterson JD, Day M, Ramsey KE, Suárez-Fariñas M, Schwarz C, Stephan DA, Surmeier DJ, Greengard P, Heintz N (2008) A translational profiling approach for the molecular characterization of CNS cell types. Cell 135:738–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nestler EJ (2014) Epigenetic mechanisms of drug addiction. Neuropharmacology 76, part B:259–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steiner H, Van Waes V (2013) Addiction-related gene regulation: Risks of exposure to cognitive enhancers vs. other psychostimulants. Prog Neurobiol 100:60–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thanos PK, Michaelides M, Benveniste H, Wang GJ, Volkow ND (2007) Effects of chronic oral methylphenidate on cocaine self-administration and striatal dopamine D2 receptors in rodents. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 87:426–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robison LS, Ananth M, Hadjiargyrou M, Komatsu DE, Thanos PK (2017) Chronic oral methylphenidate treatment reversibly increases striatal dopamine transporter and dopamine type 1 receptor binding in rats. J Neural Transm 124:655–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yano M, Beverley JA, Steiner H (2006) Inhibition of methylphenidate-induced gene expression in the striatum by local blockade of D1 dopamine receptors: Interhemispheric effects. Neuroscience 140:699–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alburges ME, Hoonakker AJ, Horner KA, Fleckenstein AE, Hanson GR (2011) Methylphenidate alters basal ganglia neurotensin systems through dopaminergic mechanisms: A comparison with cocaine treatment. J Neurochem 117:470–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhat RV, Baraban JM (1993) Activation of transcription factor genes in striatum by cocaine: role of both serotonin and dopamine systems. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 267:496–505 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lucas JJ, Segu L, Hen R (1997) 5-Hydroxytryptamine1B receptors modulate the effect of cocaine on c-fos expression: converging evidence using 5-hydroxytryptamine1B knockout mice and the 5-hydroxytryptamine1B/1D antagonist GR127935. Mol Pharmacol 51:755–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castanon N, Scearce-Levie K, Lucas JJ, Rocha B, Hen R (2000) Modulation of the effects of cocaine by 5-HT1B receptors: a comparison of knockouts and antagonists. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 67:559–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morris BJ, Reimer S, Hollt V, Herz A (1988) Regulation of striatal prodynorphin mRNA levels by the raphe-striatal pathway. Brain Res 464:15–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walker PD, Capodilupo JG, Wolf WA, Carlock LR (1996) Preprotachykinin and preproenkephalin mRNA expression within striatal subregions in response to altered serotonin transmission. Brain Res 732:25–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horner KA, Adams DH, Hanson GR, Keefe KA (2005) Blockade of stimulant-induced preprodynorphin mRNA expression in the striatal matrix by serotonin depletion. Neuroscience 131:67–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Waes V, Beverley J, Marinelli M, Steiner H (2010) Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants potentiate methylphenidate (Ritalin)-induced gene regulation in the adolescent striatum. Eur J Neurosci 32:435–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thanos PK, Robison LS, Steier J, Hwang YF, Cooper T, Swanson JM, Komatsu DE, Hadjiargyrou M, Volkow ND (2015) A pharmacokinetic model of oral methylphenidate in the rat and effects on behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 131:143–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moon C, Marion M, Thanos PK, Steiner H (2021) Fluoxetine potentiates oral methylphenidate-induced gene regulation in the rat striatum. Mol Neurobiol 58:4856–4870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thanos PK, McCarthy M, Senior D, Watts S, Connor C, Hammond N, Blum K, Hadjiargyrou M, Komatsu D, Steiner H (2023) Combined chronic oral methylphenidate and fluoxetine treatment during adolescence: Effects on behavior. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 24:1307–1314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Senior D, McCarthy M, Ahmed R, Klein S, Lee WX, Hadjiargyrou M, Komatsu D, Steiner H, Thanos PK (2023) Chronic oral methylphenidate plus fluoxetine treatment in adolescent rats increases cocaine self-administration. Addiction Neuroscience 8:100127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lamoureux L, Beverley BA, Marinelli M, Steiner H (2023) Fluoxetine potentiates methylphenidate-induced behavioral responses: enhanced locomotion or stereotypies and facilitated acquisition of cocaine self-administration. Addiction Neuroscience in press: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steiner H, Warren BL, Van Waes V, Bolaños-Guzmán CA (2014) Life-long consequences of juvenile exposure to psychotropic drugs on brain and behavior. Prog Brain Res 211:13–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alter D, Beverley JA, Patel R, Bolaños-Guzmán CA, Steiner H (2017) The 5-HT1B serotonin receptor regulates methylphenidate-induced gene expression in the striatum: Differential effects on immediate-early genes. J Psychopharmacol 31:1078–1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borycz J, Zapata A, Quiroz C, Volkow ND, Ferré S (2008) 5-HT(1B) receptor-mediated serotoninergic modulation of methylphenidate-induced locomotor activation in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 33:619–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Waes V, Ehrlich S, Beverley JA, Steiner H (2015) Fluoxetine potentiation of methylphenidate-induced gene regulation in striatal output pathways: Potential role for 5-HT1B receptor. Neuropharmacology 89:77–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meadows SM, Conti MM, Gross L, Chambers NE, Avnor Y, Ostock CY, Lanza K, Bishop C (2018) Diverse serotonin actions of Vilazodone reduce L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine-induced dyskinesia in hemi-parkinsonian rats. Mov Disord 33:1740–1749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Altwal F, Moon C, West AR, Steiner H (2020) The multimodal serotonergic agent vilazodone inhibits L-DOPA-induced gene regulation in striatal projection neurons and associated dyskinesia in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease. Cells 9:2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hughes ZA, Starr KR, Langmead CJ, Hill M, Bartoszyk GD, Hagan JJ, Middlemiss DN, Dawson LA (2005) Neurochemical evaluation of the novel 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist/serotonin reuptake inhibitor, vilazodone. Eur J Pharmacol 510:49–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Owen RT (2011) Vilazodone: a new treatment option for major depressive disorder. Drugs Today (Barc) 47:531–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cruz MP (2012) Vilazodone HCl (Viibryd): a serotonin partial agonist and reuptake inhibitor for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Pharm Ther 37:28–31 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Altwal F, Padovan-Neto FE, Ritger A, Steiner H, West AR (2021) Role of 5-HT1A receptor in vilazodone-mediated suppression of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia and increased responsiveness to cortical input in striatal medium spiny neurons in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease. Molecules 26:5790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Waes V, Carr B, Beverley JA, Steiner H (2012) Fluoxetine potentiation of methylphenidate-induced neuropeptide expression in the striatum occurs selectively in direct pathway (striatonigral) neurons. J Neurochem 122:1054–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Willuhn I, Sun W, Steiner H (2003) Topography of cocaine-induced gene regulation in the rat striatum: Relationship to cortical inputs and role of behavioural context. Eur J Neurosci 17:1053–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paxinos G, Watson C, The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 1998, New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yano M, Steiner H (2005) Methylphenidate (Ritalin) induces Homer 1a and zif 268 expression in specific corticostriatal circuits. Neuroscience 132:855–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Waes V, Vandrevala M, Beverley J, Steiner H (2014) Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors potentiate gene blunting induced by repeated methylphenidate treatment: Zif268 versus Homer1a. Addict Biol 19:986–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sahli ZT, Banerjee P, Tarazi FI (2016) The preclinical and clinical effects of vilazodone for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Expert Opin Drug Discov 11:515–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carta M, Carlsson T, Kirik D, Björklund A (2007) Dopamine released from 5-HT terminals is the cause of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in parkinsonian rats. Brain 130:1819–1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nishijima H, Tomiyama M (2016) What mechanisms are responsible for the reuptake of levodopa-derived dopamine in Parkinsonian striatum? Front Neurosci 10:575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carta M, Björklund A (2018) The serotonergic system in L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia: pre-clinical evidence and clinical perspective. J Neural Transm 125:1195–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cenci MA (2017) Molecular mechanisms of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. In: Steiner H and Tseng KY (eds) Handbook of Basal Ganglia Structure and Function. Elsevier, London, pp. 857–871 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Spigolon G, Fisone G (2018) Signal transduction in L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia: from receptor sensitization to abnormal gene expression. J Neural Transm 125:1171–1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lanza K, Bishop C (2018) Serotonergic targets for the treatment of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. J Neural Transm 125:1203–1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cohen SR, Terry ML, Coyle M, Wheelis E, Centner A, Smith S, Glinski J, Lipari N, Budrow C, Manfredsson FP, Bishop C (2022) The multimodal serotonin compound vilazodone alone, but not combined with the glutamate antagonist amantadine, reduces l-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in hemiparkinsonian rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 217:173393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sellnow RC, Newman JH, Chambers N, West AR, Steece-Collier K, Sandoval IM, Benskey MJ, Bishop C, Manfredsson FP (2019) Regulation of dopamine neurotransmission from serotonergic neurons by ectopic expression of the dopamine D2 autoreceptor blocks levodopa-induced dyskinesia. Acta Neuropathol Commun 7:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barnes NM, Sharp T (1999) A review of central 5-HT receptors and their function. Neuropharmacology 38:1083–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.De Deurwaerdère P, Di Giovanni G (2016) Serotonergic modulation of the activity of mesencephalic dopaminergic systems: Therapeutic implications. Prog Neurobiol in press: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Budrow C, Elder K, Coyle M, Centner A, Lipari N, Cohen S, Glinski J, Kinzonzi N, Wheelis E, McManus G, Manfredsson F, Bishop C (2023) Serotonergic actions of vortioxetine as a promising avenue for the treatment of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. Cells 12:837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lobo MK, Nestler EJ (2011) The striatal balancing act in drug addiction: distinct roles of direct and indirect pathway medium spiny neurons. Front Neuroanat 5:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Steiner H (2017) Psychostimulant-induced gene regulation in striatal circuits. In: Steiner H and Tseng KY (eds) Handbook of Basal Ganglia Structure and Function. Academic Press/Elsevier, London, pp. 639–672 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.