Abstract

The rates of atrial fibrillation (AF) and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) continue to grow with many patients suffering from their combined impact on quality of life and prognosis.

A lower heart rate (HR) in HFrEF is associated with reduced morbidity and mortality due to beta-blocker and ivabradine therapy. Postulated mechanisms include reduced neurohumoral activation, increased diastolic filling time and myocardial energy conservation. In contrast, the landmark randomised controlled non-inferiority RACE II trial demonstrated that a lenient rate control strategy (target HR <110 beats per minute [bpm]) was more attainable and safer than a strict rate control strategy (resting HR <80 bpm) in permanent AF. Physiologically, a higher HR is needed to compensate for the lost ‘atrial kick’ that contributes to the cardiac output by coordinated atrial contractions in normal sinus rhythm.

This leaves the not insignificant number of patients with HFrEF and AF in a conundrum over optimal HR control. Retrospective analyses of AF and HR control in landmark HFrEF trials (e.g. CHARM, PARADIGM and ATMOSPHERE) point towards better outcomes with a less stringent target HR. However, this association disappears after adjustment for known prognostic markers in HFrEF, including left ventricular ejection fraction, New York Heart Association class and NT-proBNP levels. There is a clear need for dedicated randomised controlled trials, investigating rate control strategies in this increasingly large subgroup of patients.

Regardless of rate control strategy, effective anti-coagulation and guideline-directed medical therapy must not be forgotten in the treatment of patients with HFrEF and AF.

Keywords: Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, Atrial fibrillation, Rate control, Target heart rate, Symptoms, Outcomes

Highlights

-

•

Anti-coagulation & optimal medical therapy are cornerstones of HFrEF-AF treatment.

-

•

A lower HR has better prognosis in HFrEF, but lenient rate control is safer in AF.

-

•

The impact of different rate control strategies in HFrEF-AF is less clear.

-

•

Randomised controlled trials on target HR range in HFrEF-AF are urgently needed.

1. Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) and heart failure (HF) are two common heterogenous conditions with high morbidity and mortality rates [1], [2], [3], [4]. The former is a supraventricular tachyarrhythmia, characterised by uncoordinated atrial electrical activity and subsequent ineffective atrial contractions [3], [4]. The latter describes a clinical syndrome, whereby cardiac structural and functional abnormalities, the final common pathway of diverse cardiac diseases, lead to signs and symptoms of congestion. Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) is HF, caused by impaired left ventricular systolic function with an ejection fraction ≤40 % [1], [2].

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and American Heart Association (AHA) estimate that 1 in 3 and 1 in 4 will develop AF and HF respectively [1], [2], [3], [4]. AF and HF frequently coexist as they share risk factors and drive the other's disease progression through an interplay of structural, electrical and neurohumoral changes [5], [6], [7], [8]. These include increased intracavity pressures, dilatation of the chambers and upregulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAAS) and sympathetic nervous systems, producing substrates for irregular conductions and ultimately a reduced cardiac output (Fig. 1) [5], [6], [7], [8]. The most recent National Heart Failure Audit (NHFA) on HF hospitalisations in the United Kingdom reported an AF prevalence of 40 % in patients with HFrEF [8]. A diagnosis of both predicts a worse prognosis than each condition alone through direct disease effects and their association with other poor prognostic markers [5], [6], [7], [8].

Fig. 1.

The shared and synergistic pathophysiology of heart failure and atrial fibrillation. APD indicates action potential duration; RAAS: renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

Together with effective anti-coagulation, rate and rhythm control form the pillars of AF management. Similar to the RACE I and AFFIRM trials in patients with persistent, recurrent AF in the absence of HF, the randomised controlled trial (RCT) AF-CHF demonstrated that rate control was at least non-inferior to electrical and medical rhythm control in patients with AF and HFrEF [9], [10], [11]. HFrEF patients are often also frailer and have underlying coronary artery and renal disease, putting them at greater risk of life-threatening tachy- and brady-arrhythmias with rhythm control drugs (e.g. amiodarone and flecainide) and complications in ablation procedures (e.g. cardiac tamponade and major bleeding) [12], [13], [14].

Recent advances in catheter ablation technology have led to a renewed interest in early rhythm control of AF [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. The beneficial treatment effect in the subgroup of AF patients with HFrEF remains uncertain. In the intention-to-treat analysis of CASTLE-AF, 51/179 (28.5 %) and 82/184 (44.6 %) HFrEF patients with AF treated by ablation and pharmacotherapy respectively experienced the primary composite endpoint of death from any cause or hospitalisation for worsening HF [14]. The fragility index, a measure of the trial's statistical robustness, was 11. This means that only half of the 23 patients treated by ablation and lost to follow-up needed to meet the primary composite endpoint to make the results insignificant [14], [15]. In the other landmark trial CABANA comparing catheter ablation to pharmacotherapy, only approximately 1/3rd had HF and of those, less than one tenth had HFrEF, making any conclusion tenuous at best [16], [17]. A recent AHA Scientific Statement argues in favour of non-pharmacological rhythm control of AF in HFrEF [18]. However, a decision to pursue this strategy has to carefully take into account patient co-morbidities, New York Heart Association functional class (NYHA), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), ventricular and atrial scar burden as well as duration and burden of AF [18], [19].

A more equitable and attainable treatment strategy may be rate control. The purpose of this article is to review the existing literature on optimal heart rate (HR) control in HFrEF and AF. The prognostic significance and treatment targets of HR are examined in HFrEF and AF separately, including a forensic analysis of the RACE II trial before HR control is examined in patients with both HFrEF and AF.

2. The story of HFrEF and sinus rhythm

Observational studies in HF and cardiovascular disease cohorts show an association between stricter HR control (i.e. <70 beats per minute [bpm]) in sinus rhythm (SR) and reduced all-cause and cardiovascular deaths and hospitalisation for HF [20], [21], [22], [23]. More importantly, two rate-lowering drug classes, beta-blockers (BB) and ivabradine have proven efficacy in improving outcomes in patients with HFrEF and SR. In a meta-analysis of 11 randomised, placebo-controlled HFrEF trials that included 14,166 patients in SR, BB treatment reduced their mortality by 27 % irrespective of baseline HR. [24] Conversely, a lower pre-medication baseline HR was also associated with a better prognosis, suggesting that tighter HR control directly alters the progression of HF [24], [25]. Reasons may include lower neurohumoral activation and stress response, augmented coronary blood flow during longer diastole, myocardial energy conservation and improved force-frequency mechanics in the myocardial cell (Bowditch effect) [25].

Ivabradine is a drug that reduces HR by acting solely on the sodium current If in the sinoatrial node. In the SHIFT trial, 6558 HFrEF patients on optimal pharmacotherapy were randomised to ivabradine or placebo treatment [26]. Ivabradine led to an 18 % relative reduction in the primary outcome of cardiovascular death and HF hospitalisation, which correlated with an average HR reduction of 11 bpm. This benefit was seen despite approximately 90 % of patients receiving BB [26]. Stricter HR control may directly improve outcomes in patients with HFrEF and SR.

3. Lessons from RACE II

AF with rapid ventricular response impairs cardiac function at a cellular, physiological and clinical level, leading to a tachycardiomyopathy in some cases [27], [28]. Its management was historically based on stringent rate control [29]. The randomised controlled non-inferiority RACE II trial investigated the optimal rate control strategy in patients with permanent AF by comparing lenient HR control (resting HR <110 bpm) to strict HR control (HR <80 bpm at rest and <110 bpm on exercise) in 311 and 303 patients respectively [30], [31]. Overall, 287/614 (46.7 %) had HF, including 93/287 (32.4 %) with HFrEF [32]. Any observations are therefore hypothesis-generating at best in patients with AF and HFrEF. Table 1 summarises the trial.

Table 1.

Summary of RACE II trial [32].

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

| Type of study | Prospective, multi-centre, randomised, open-label non-inferiority trial |

| Patient selection | Relevant inclusion criteria: Permanent AF for up to 12 months, ≤80 years of age, current use of anti-coagulation |

| Relevant exclusion criteria: NYHA class IV CHF or HHF in last 3 months, paroxysmal AF | |

| Intervention | Lenient (<110) vs. strict (<80 at rest, <110 on exercise) HR control |

| Combined primary outcome | Death from cardiovascular causes, HHF, stroke, systemic embolism, major bleeding, arrhythmic events (syncope, sustained ventricular tachycardia, cardiac arrest), life-threatening adverse effects of rate-control drugs, and implantation of a PPM or ICD |

| Results | Lenient (n = 311) | Strict (n = 303) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline demographics | ||

| Months AF (median[IQR]) | 16 (6–54) | 20 (6–64) |

| Prev. HF hospitalisation | 28 (9.0) | 32 (10.6) |

| LVEF ≤40 % | 45 (14.5) | 48 (15.8) |

| Symptoms | 173 (55.6) | 175 (57.8) |

| Palpitations | 62 (19.9) | 83 (27.4) |

| Dyspnoea | 105 (33.8) | 109 (36.0) |

| Fatigue | 86 (27.7) | 97 (32.0) |

| Rate control targets | ||

| Target HR achieved | 304 (97.7) | 203 (67.0) |

| Resting HR <70 bpm | 1 (0.3) | 67 (22.1) |

| Resting HR >100 bpm | 70 (22.5) | 16 (5.3) |

| Outcomes | ||

| Combined primary | 38 (12.9) | 43 (14.9) |

| Symptoms | 129/283 (45.6) | 126/274 (46.0) |

| Palpitations | 30/283 (10.6) | 26/274 (9.5) |

| Dyspnoea | 85/283 (30.0) | 81/274 (29.6) |

| Fatigue | 69/283 (24.4) | 62/274 (22.6) |

AF indicates atrial fibrillation; HR: heart rate; NYHA: New York Heart Association functional classification; CHF: congestive heart failure; HHF: hospitalisation for heart failure; PPM: permanent pacemaker; ICD: implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction.

3.1. Stricter does not mean better HR control

After a maximum 3-year follow-up, lenient rate control was non-inferior to strict rate control with 38/311 (12.9 %) and 43/303 (14.9 %) reaching the primary endpoint respectively [30]. The absence of significant treatment differences may be explained by a broad primary endpoint that included cardiovascular death, HF hospitalisation, stroke, systemic embolism, major bleeding, arrhythmic events, adverse effects of rate control and cardiac device implantation. One third of events in both arms was due to major bleeding, which is less related to rate control and more to warfarinisation [30]. The difference in average HR achieved in both groups was also relatively small. Only 1/5th of patients had a leniently controlled HR 100-110 bpm and a strictly controlled HR <70 bpm respectively [30].

The risks of strict rate control may simply outweigh any perceived benefits. In the strict rate control arm, 100/303 (33.0 %) did not achieve their target HR; 53/100 (53.0 %) already had well-tolerated symptoms without intensified rate control and 25/100 (25.0 %) failed to reach the target HR due to rate control drug-related adverse events [30]. In AF, firstly, a faster HR may be needed to compensate for the lost atrial ‘kick,’ impaired diastolic filling and reduced stroke volume and secondly, increased ventricular rates are reflective of better and therefore healthier atrioventricular node conduction [5], [25], [28]. In comparison, only 7/311 (2.3 %) patients with lenient rate control did not meet their target, pointing to a more realistic and safer therapeutic strategy [30].

3.2. Impact of HR on symptoms

The outcome that patients understandably may consider most relevant is the daily symptoms associated with AF. Strict rate control led to a greater absolute reduction in the number of patients with palpitations in comparison to lenient rate control (−17.9 % vs. −9.3 %) [30]. However, dyspnoea and fatigue, symptoms that are not specific to AF affected more patients than palpitations at baseline. In both groups, their burden was relatively unchanged after appropriate rate control with 1 in 4 still fatigued and 1 in 3 still breathless [30], [33]. Both groups showed a 10 % reduction in overall symptom burden with every second person remaining symptomatic [33]. These improvements in quality of life were not associated with rate control, but instead with the presence of symptoms at baseline, higher baseline LVEF, and absence of co-morbidities [33].

A post-hoc subgroup analysis of the 287 (46.7 %) HF patients, including 93 (32.4 %) with HFrEF showed that the stringency of rate control did not alter their clinical outcomes [32]. Similar to the overall study population, HF patients were predominantly limited by dyspnoea, which was strongly associated with worse Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire scores, but not rate control [33]. In permanent AF, rate control may have little impact on the predominant symptom of breathlessness.

4. Heart rate control in HFrEF with AF

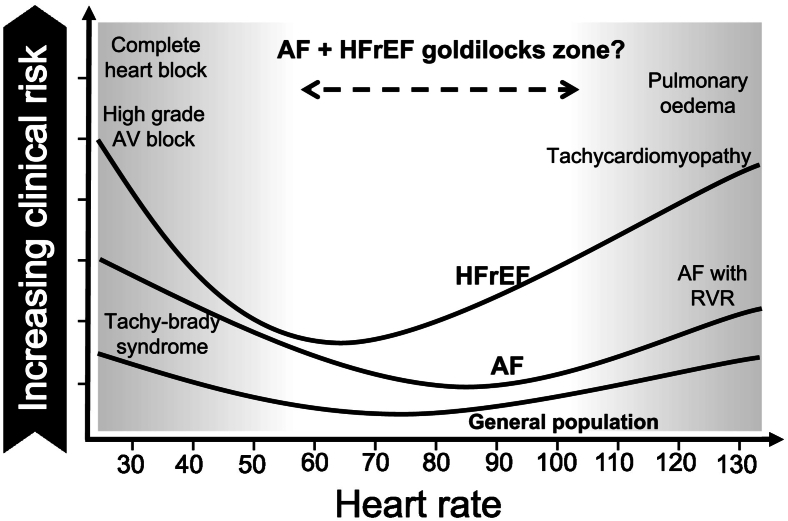

The impact of HR on outcomes for patients in AF without HF in comparison to patients in SR with underlying HFrEF is different. A lower HR in HFrEF is protective, but tighter rate control in AF may increase drug-related side effects without improved mortality or morbidity. This leaves patients with both conditions and their treating physicians in a conundrum (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The relative clinical risk of AF and HFrEF according to heart rate. AF indicates atrial fibrillation; HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; AV: atrioventricular; RVR: rapid ventricular response.

4.1. Retrospective observations

Previous observational studies, RCTs and meta-analyses in HFrEF can provide some, albeit limited insight into rate control of coexistent AF. Table 2 summarises the key studies.

Table 2.

Overview of previous studies that investigated heart rate control in HFrEF patients with underlying AF [9], [29], [38], [39].

| Lead author | Type of study | Total cohort (n) | Patients w/ AF n(%) | Patients w/ HFrEF n(%) | Heart rate tertiles | Variables in multi-variate analysis | Principle findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Castagno et al. 2012 [34] | Retrospective analysis of CHARM programme | 7597 | 1148 (15.1) | 4576 (60.2) | T1 60 (57–64)a T2 72 (70–74)a T3 84 (80–90)a |

Age, LVEF, diabetes, prev. HF hospitalisation, NYHA, BMI, diastolic BP, sex, cardiomegaly, candesartan use, BB use | HFrEF Mortality HR 1.06 (1.02–1.10) CVD/HHF HR 1.07 (1.03–1.10) AF Mortality HR 0.97 (0.90–1.05) CVD/HHF HR 0.95 (0.89–1.02) |

| Simpson et al. 2015 [35] | Sub-study of MAGGIC meta-analysis | 21,361 | 3259 (15.3) [2910 in multivariate analysis] | 2285 (10.7) | T1 < 78 (32–77) T2 78–98 T3 > 98 (99–180) |

Age, sex, LVEF, ischaemic aetiology, HTN, diabetes, BB use | Heart rate nominal variable Mortality HR T1 1.00 T2 0.96 (0.83–1.19) T3 0.81 (0.72–1.03) Heart rate numerical variable Mortality HR 0.95 (0.92–0.98) per 10 bpm increase |

| Cullington et al. 2014 [20] | Prospective cohort study | 2039 | 488 (24.0) | 2039 (100.0) [LVEF <50] |

Per 10 bpm increase | Age, weight, QRS duration, systolic BP, NYHA, IHD, BB use | Univariate analysis Mortality HR 0.93 (0.88–0.99) Multivariate analysis Mortality HR 0.94 (0.88–1.00) |

| Docherty et al. 2019 [25] | Retrospective analysis of Paradigm & Atmosphere RCTs | 13,562 | 3449 (25.4) | 13,562 [100.0] | T1 ≤ 72 T2 73–85 T3 ≥ 86 |

Age, sex, race, region, NYHA, LVEF, IHD, systolic BP, BMI, eGFR, HF duration & hospitalisation, diabetes, stroke, digoxin use, BB use, amiodarone use, NT-proBNP | Univariate analysis Pump failure death HR T1 1.0 T2 0.67 (0.47–0.97) T3 0.67 (0.46–0.96) Multivariate analysis Pump failure death HR T1 1.0 T2 0.76 (0.52–1.11) T3 0.85 (0.58–1.25) |

AF indicates atrial fibrillation; HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; HF: heart failure; NYHA: New York Heart Association functional classification; BMI: body mass index; BP: blood pressure; BB: beta-blocker; HR: hazard ratio; CVD: cardiovascular death; HHF: hospitalisation for heart failure; HTN: hypertension; IHD: ischaemic heart disease; RCT: randomised controlled trial; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide. amedian(IQR).

In a retrospective analysis of the CHARM (Candesartan in Heart Failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity) program that included HF patients with reduced and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), Castagno et al. examined the relationship between baseline HR and the endpoints, all-cause mortality and cardiovascular death or hospitalisation for worsening HF (Table 2) [34]. Of 7597 patients, 4576 (60.2 %) had HFrEF and 1148 (15.1 %) had AF. Overall, patients, who were younger, female, current smokers, more hypertensive and diabetic without a history of MI tended to have a higher resting HR. These patients also had a worse baseline LVEF, NYHA class and were more likely to have a history of hospitalisation for HF [34]. Many of these associations disappeared in the subgroup with AF at baseline [34]. Furthermore, in patients with HFrEF an increase in HR by 12 bpm was associated with a 6–7 % increased risk of reaching the above endpoints, irrespective of the use or dose of BB and other known prognostic markers (e.g. NYHA class and previous hospitalisation for HF). This relationship was not seen in patients with AF and a median EF 38 % [34].

The MAGGIC (Meta-analysis Global Group in Chronic Heart Failure) meta-analysis pooled individual patient data of 41,972 patients from a mixture of observational and small RCTs to compare the 3-year mortality rates of HFrEF and HFpEF patients [35]. In a sub-study of 3259 (15.3 %) patients with AF, there were 15.9 deaths per 100 patient-years in the highest HR tertile (>98 bpm) versus 18.9 deaths per 100 patient-years in the lowest HR tertile (<78 bpm) (Table 2) [35]. After adjustment for known markers of prognosis in HFrEF, HR remained statistically significant as a continuous, but not categorical variable. A 10 bpm incremental increase in ventricular rate was associated with a 5 % relative reduced risk of death per year [35]. In a different prospective cohort study of 2039 patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD) and EF ≤50 %, 488 (24.0 %) AF patients had a similar 7 % relative risk reduction in all-cause mortality for every 10 bpm increase in baseline HR (Table 2) [20]. However, after adjustment for age, systolic BP, QRS duration, NYHA class, and BB use, HR was not significantly associated with survival [20]. Contrary to rate control in HFrEF with underlying SR, a more lenient strategy may cause less harm and in fact be beneficial in HFrEF with AF.

In a pooled analysis of 3449 HFrEF patients with AF and a median EF 30.6 % from the PARADIGM-HF and ATMOSPHERE trials, Docherty et al. also examined the impact of baseline HR and change in HR after 12 months on clinical endpoints (Table 2) [25]. These included the composite of cardiovascular death and HF hospitalisation, sudden death, pump failure death and all-cause mortality. On univariate analysis, the only endpoint that differed between HR tertiles was risk of pump failure death; it was greatest in patients in the lowest HR tertile (HR ≤72 bpm) [25]. However, similar to previously described studies, any association between HR and said endpoints disappeared after adjustment for established prognostic markers, including N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) [25]. Although a higher baseline HR seems favourable in HFrEF patients with AF, further increases in HR after 12 months of treatment tended to increase symptoms, NT-proBNP levels, HF hospitalisation and mortality [25].

4.2. Beta-blockers and digoxin

Beta-blocker therapy is a cornerstone in the pharmacological management of HFrEF, improving morbidity and mortality through various pathways including a reduced HR. [24] As it is also one of three commonly prescribed chronotropic drug classes to improve rate control in AF, BB should be an ideal therapeutic agent for HFrEF patients with AF [3], [4], [29]. This was clarified in a meta-analysis of AF sub-studies from four RCTs comparing BB therapy to placebo in HFrEF [36]. From an original 8680 patients, 1677 (19 %) had AF, of whom 842 and 835 were randomised to BB and placebo respectively. BB therapy had a mortality risk odds ratio (OR) of 0.86 with a relatively large 95 % confidence interval (CI) of 0.66 to 1.13 and an even less favourable HF hospitalisation OR of 1.11 (95 % CI 0.85–1.47) [37]. In HFrEF patients with AF, BB seems to have a disappointingly neutral effect on clinical outcomes [36], [37].

Two small RCTs investigated the combined and differential effect of BB and digoxin therapy on HR control, LV function and symptoms in patients with AF and HF [38], [39]. The earlier trial was conducted in two phases and recruited 47 patients with HF (43 had LVEF <40 %) and AF treated with digoxin [38]. First, patients were randomised to carvedilol or placebo for 4 months and after the withdrawal of digoxin in the combined therapy group, patients were treated with either carvedilol or digoxin over the next 6 months. The addition of carvedilol to digoxin improved rate control, LVEF and symptoms [38]. Importantly, the subsequent stopping of digoxin led to a drop in LVEF and worsening of symptoms, contradicting previous neutral findings of digoxin therapy in HFrEF [38], [40]. In a more recent study of 160 patients in permanent AF with symptoms of HF, there was no significant difference between digoxin and bisoprolol therapy in overall patient reported quality of life at 6 months [39]. However, after 12 months, patients on digoxin had significantly better scores in certain domains of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). The trial was not powered for this secondary analysis and LVEF was not part of the inclusion criteria [39]. The Digit-HF trial will re-examine the role of digoxin and other cardiac glycosides in HFrEF, including in the subgroup of patients with coexistent AF [41].

5. Treatment targets on HFrEF-AF axis

Effective anti-coagulation in AF and guideline-directed medical therapy in HFrEF must be remembered in the treatment of patients with both conditions [1], [2], [3], [4]. Fig. 3 summarises the important treatment targets. To treat AF in the context of HFrEF the most recent AHA guidelines do not specify a target HR while current ESC guidelines recommend a leniently controlled resting HR target of <110 bpm in line with the limited evidence from the RACE II trial [2], [30], [32]. However, if there is a deterioration in symptoms or worsening LVEF, stricter HR control may be considered [2], [4].

Fig. 3.

Treatment targets on the HFrEF-AF axis, including guideline-directed medical therapy, anticoagulation, catheter ablation and rate control. AF indicates atrial fibrillation; HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; AVN: atrioventricular node; CRT: cardiac resynchronisation therapy; SGLT2i: sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor; ACEi: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: angiotensin II receptor blocker; MRA: mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; ARNI: angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor; APD: action potential duration; RAAS: renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

5.1. Impact of AF on HFrEF

In patients without LV systolic impairment, rhythm and rate control of AF improve outcomes when used in appropriate circumstances [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [30]. However, underlying HFrEF likely changes the role of AF as a disease and treatment substrate, explaining why the already weak association between HR control and clinical outcomes becomes insignificant when adjusted for known markers of prognosis in HFrEF (e.g. LVEF, NT-proBNP levels, NYHA class, medications, etc.) [20], [25], [34], [35]. Similar to fluid overload, the state of permanent or persistent AF is perhaps more a marker of being in cardiac failure and less a disease-modifying treatment target in HFrEF. A reasonable HR range may help control symptoms, but not improve clinical outcomes [30], [31], [32], [33], [34]. The RACE II trial was only powered to test for non-inferiority of lenient versus strict HR control on clinical outcomes in patients with AF. Currently underway, the DanAF trial will investigate which strategy is superior, using symptoms as the primary outcome [42].

In contrast, HFrEF patients with paroxysmal or new-onset AF were at higher risk of hospitalisation and stroke than patients without AF or with permanent/persistent AF in a combined retrospective analysis of the PARADIGM-HF (sacubitril-valsartan vs. enalapril in HFrEF) and ATMOSPHERE trials (aliskiren vs. enalapril vs. combined therapy in HFrEF) [43]. This was observed despite greater phenotypic similarity between patients in the AF subgroups versus patients without AF. Characteristics included LVEF, NT-proBNP level and NYHA class [43]. In a post-hoc analysis of the AF subpopulation in the COMET trial (carvedilol vs. metoprolol in HFrEF), a similar pattern was observed [44]. The haemodynamic instability and increased risk of stroke during the onset of AF may be more important than the long-term state of AF in HFrEF patients [43], [44]. Effective anti-coagulation remains paramount. Catheter ablation strategies to prevent paroxysms of AF precipitating decompensated HF may also have an important role to play (Fig. 3) [18], [19].

5.2. Impact of new HF pharmacotherapy on AF

If chronic AF is a marker of worsening cardiac failure in patients with HFrEF, then guideline-directed HFrEF medical therapy as well as the treatment of the underlying cause of LV systolic dysfunction remain the cornerstones of treatment (Fig. 3). In the CAN-TREAT algorithm for the management of HFrEF and AF, Kotecha et al. emphasise the importance of RAAS inhibition and treating other underlying cardiovascular disease [5].

In contrast to BB therapy, RAAS inhibition is associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalisation for HF in patients with HFrEF and AF from meta-analyses and post-hoc subgroup analyses of RCTs [45], [46], [47], [48]. These agents include angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB), mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA) and the relatively newer agent, sacubitril/valsartan, which also has a neprilysin inhibitor. This group of medication may also prevent the onset of AF in patients with HFrEF by 48 %, potentially limiting episodes of arrhythmia-induced HF decompensation [45], [46], [47], [48]. Postulated mechanisms include a reduction in left atrial size, fibrosis and hypertrophy (Fig. 3) [45], [46], [47], [48].

Two further drug classes that reduce morbidity and mortality in HFrEF, including AF subgroups are the sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) and soluble guanylate cyclase receptor stimulator (e.g. vericiguat) [2], [49], [50]. With less haemodynamic and blood pressure effects, these drugs improve myocardial metabolism and reduce oxidative stress respectively [51]. Although their beneficial effects are maintained across the different AF subgroups, their impact on AF incidence remains unclear [52], [53], [54], [55]. A post-hoc subgroup analysis of the DAPA-HF trial, comparing dapagliflozin to placebo in HFrEF did not show any impact on AF incidence, however, a larger meta-analysis of different SGLT2i trials in HF showed a 37 % relative risk reduction in AF incidence [54], [55]. The anti-arrhythmic effects of SGLT2is may include the shift to ketogenic metabolism and stabilisation of the Na+/H+ exchanger 1 (NHE1) ion channel in cardiac myocytes [55].

6. Knowledge gaps

To help answer the question of optimal HR target or range in patients with HFrEF and AF the following are recommendations for future research.

-

1.

The mechanisms underlying the development and progression of AF in HFrEF need further study.

-

2.

The impact of the different subtypes of AF on patients with HFrEF needs further investigation at a cellular, haemodynamic and clinical level.

-

3.

Large randomised controlled trials comparing different rate control strategies in well-phenotyped groups of patients with HFrEF and AF are needed.

7. Conclusion

AF and HFrEF are likely to dominate healthcare and cardiology services. We know that patients with both diagnoses do worse, yet treatment options for symptomatic and prognostic benefit are limited. Effective anti-coagulation and guideline-directed medical therapy remain the foundation of treatment in patients with both conditions. HR is an important therapeutic target in each condition separately. Barring destabilising fast ventricular responses, patients in AF fare better with a more lenient rate control strategy. Conversely, a lower HR is a positive prognostic marker in HFrEF. From the limited available evidence of post-hoc analyses of RCTs, meta-analyses and observational studies the effects of HR and its treatment seem to be different in patients with HFrEF and AF. The impact and treatment of this important physiological parameter need to be further investigated in patients with HFrEF and AF.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor John J. McMurray for his conception and support of writing this review article. Dr. K Hesse performed the literature review and drafted, reviewed and revised the manuscript, tables and figures.

References

- 1.Heidenreich P.A., Bozkurt B., Aguilar D., Allen L.A., Byun J.J., Colvin M.M., Deswal A., Drazner M.H., Dunlay S.M., Evers L.R., Fang J.C., Fedson S.E., Fonarow G.C., Hayek S.S., Hernandez A.F., Khazanie P., Kittleson M.M., Lee C.S., Link M.S., Milano C.A., Nnacheta L.C., Sandhu A.T., Stevenson L.W., Vardeny O., Vest A.R., Yancy C.W. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: a report of the american College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2022 May 3;145(18):e895–e1032. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonagh T.A., Metra M., Adamo M., Gardner R.S., Baumbach A., Böhm M., Burri H., Butler J., Čelutkienė J., Chioncel O., Cleland J.G.F., Coats A.J.S., Crespo-Leiro M.G., Farmakis D., Gilard M., Heymans S., Hoes A.W., Jaarsma T., Jankowska E.A., Lainscak M., Lam C.S.P., Lyon A.R., McMurray J.J.V., Mebazaa A., Mindham R., Muneretto C., Francesco Piepoli M., Price S., Rosano G.M.C., Ruschitzka F., Kathrine Skibelund A., ESC Scientific Document Group. Authors/Task Force Members 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022 Jan;24(1):4–131. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.January C.T., Wann S.L., Alpert J.S., Calkins H., Cigarroa J.E., Cleveland J.C., et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the american College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014 Dec 14;64(21):e1–e76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hindricks G., Potpara T., Dagres N., Arbelo E., Bax J.J., Blomström-Lundqvist C., ESC Scientific Document Group 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Eur. Heart J. 2021 Feb 1;42(5):373–498. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotecha D., Piccini J.P. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure: what should we do? Eur. Heart J. 2015 Dec 7;36(46):3250–3257. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zafrir B., Lund L.H., Laroche C., Ruschitzka F., Crespo-Leiro M.G., Coats A.J.S., et al. Prognostic implications of atrial fibrillation in heart failure with reduced, mid-range, and preserved ejection fraction: a report from 14 964 patients in the european Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur. Heart J. 2018 Dec 21;39(48):4277–4284. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pandey A., Kim S., Moore C., Thomas L., Gersh B., Allen L.A., et al. Predictors and prognostic implications of incident heart failure in patients with prevalent atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017 Jan;5(1):44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR) Bart’s Health; London: 2020 Dec. National Heart Failure Audit 2020 summary report (2018/19 Data)https://www.nicor.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/National-Heart-Failure-Audit-2020-FINAL.pdf [cited 2021 March]. Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy D., Talajic M., Nattel S., Wyse D.G., Dorian P., Lee K.L., et al. Atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure investigators. Rhythm control versus rate control for atrial fibrillation and heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008 Jun 19;358(25):2667–2677. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Gelder I.C., Hagens V.E., Bosker H.A., Kingma J.H., Kamp O., Kingma T., et al. Rate control versus electrical cardioversion for persistent atrial fibrillation study group. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with recurrent persistent atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002 Dec 5;347(23):1834–1840. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyse D.G., Waldo A.L., DiMarco J.P., Domanski M.J., Rosenberg Y., Schron E.B., et al. Atrial fibrillation follow-up investigation of rhythm management (AFFIRM) investigators. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002 Dec 5;347(23):1825–1833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirchhof P., Camm A.J., Goette A., Brandes A., Eckardt L., Elvan A., et al. EAST-AFNET 4 trial investigators. Early rhythm-control therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 Oct 1;383(14):1305–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2019422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuck K.H., Brugada J., Fürnkranz A., Metzner A., Ouyang F., Chun K.R., FIRE AND ICE Investigators Cryoballoon or radiofrequency ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016 Jun 9;374(23):2235–2245. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marrouche N.F., Brachmann J., Andresen D., Siebels J., Boersma L., Jordaens L., et al. CASTLE-AF Investigators Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018 Feb 1;378(5):417–427. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Docherty K.F., Jhund P.S., McMurray J.J.V. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018 Aug 2;379(5):491–492. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1806519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Packer D.L., Mark D.B., Robb R.A., Monahan K.H., Bahnson T.D., Poole J.E., et al. CABANA Investigators Effect of catheter ablation vs antiarrhythmic drug therapy on mortality, stroke, bleeding, and cardiac arrest among patients with atrial fibrillation: the CABANA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019 Apr 2;321(13):1261–1274. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Packer D.L., Piccini J.P., Monahan K.H., Al-Khalidi H.R., Silverstein A.P., Noseworthy P.A., et al. Ablation versus drug therapy for atrial fibrillation in heart failure: results from the CABANA trial. Circulation. 2021 Feb;8(143):1377–1390. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gopinathannair R., Chen L.Y., Chung M.K., Cornwell W.K., Furie K.L., Lakkireddy D.R., Marrouche N.F., Natale A., Olshansky B., Joglar J.A., American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee and Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology. <collab>Council on Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biologycollab, Council on Hypertension. Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health. The Stroke Council Managing atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2021 Jun;14(6) doi: 10.1161/HAE.0000000000000078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee J.Z., Cha Y.M. Atrial fibrillation and heart failure: a contemporary review of current management approaches. Heart Rhythm O2. 2021;2(6Part B):762–770. doi: 10.1016/j.hroo.2021.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cullington D., Goode K.M., Zhang J., Cleland J.G., Clark A.L. Is heart rate important for patients with heart failure in atrial fibrillation? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014 Jun;2(3):213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hori M., Okamoto H. Heart rate as a target of treatment of chronic heart failure. J. Cardiol. 2012 Aug;60(2):86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kannel W.B., Kannel C., Paffenbarger R.S., Jr., Cupples L.A. Heart rate and cardiovascular mortality: the Framingham study. Am. Heart J. 1987 Jun;113(6):1489–1494. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90666-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox K., Ford I., Steg P.G., Tendera M., Robertson M., Ferrari R., BEAUTIFUL investigators Heart rate as a prognostic risk factor in patients with coronary artery disease and left-ventricular systolic dysfunction (BEAUTIFUL): a subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008 Sep 6;372(9641):817–821. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61171-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kotecha D., Flather M.D., Altman D.G., Holmes J., Rosano G., Wikstrand J., et al. Beta-blockers in Heart Failure Collaborative Group Heart rate and rhythm and the benefit of Beta-blockers in patients with heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017 Jun 20;69(24):2885–2896. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Docherty K.F., Shen L., Castagno D., Petrie M.C., Abraham W.T., Böhm M., et al. Relationship between heart rate and outcomes in patients in sinus rhythm or atrial fibrillation with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020 Mar;22(3):528–538. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swedberg K., Komajda M., Böhm M., Borer J.S., Ford I., Dubost-Brama A., et al. SHIFT Investigators Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2010 Sep 11;376(9744):875–885. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pellman J., Sheikh F. Atrial fibrillation: mechanisms, therapeutics, and future directions. Compr. Physiol. 2015 Apr;5(2):649–665. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daoud E.G., Weiss R., Bahu M., Knight B.P., Bogun F., Goyal R., et al. Effect of an irregular ventricular rhythm on cardiac output. Am. J. Cardiol. 1996 Dec 15;78(12):1433–1436. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)89297-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.European Heart Rhythm Association. European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. Camm A.J., Kirchhof P., Lip G.Y., Schotten Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur. Heart J. 2010 Oct;31(19):2369–2429. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Gelder I.C., Groenveld H.F., Crijns H.J., Tuininga Y.S., Tijssen J.G., Alings A.M., RACE II Investigators Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010 Apr 15;362(15):1363–1373. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Gelder I.C., Van Veldhuisen D.J., Crijns H.J., Tuininga Y.S., Tijssen J.G., Alings A.M., et al. Rate control efficacy in permanent atrial fibrillation: a comparison between lenient versus strict rate control in patients with and without heart failure. Background, aims, and design of RACE II. Am. Heart J. 2006 Sep;152(3):420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mulder B.A., Van Veldhuisen D.J., Crijns H.J., Tijssen J.G., Hillege H.L., Alings M., RACE II investigators Lenient vs. strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure: a post-hoc analysis of the RACE II study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2013 Nov;15(11):1311–1318. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Groenveld H.F., Crijns H.J., Van den Berg M.P., Van Sonderen E., Alings A.M., Tijssen J.G., RACE II Investigators The effect of rate control on quality of life in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation: data from the RACE II (Rate Control Efficacy in Permanent Atrial Fibrillation II) study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011 Oct 18;58(17):1795–1803. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castagno D., Skali H., Takeuchi M., Swedberg K., Yusuf S., Granger C.B., Michelson E.L., et al. CHARM Investigators Association of heart rate and outcomes in a broad spectrum of patients with chronic heart failure: results from the CHARM (Candesartan in heart failure: assessment of reduction in mortality and morbidity) program. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012 May 15;59(20):1785–1795. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simpson J., Castagno D., Doughty R.N., Poppe K.K., Earle N., Squire I., Richards M., et al. Meta-analysis Global Group in Chronic Heart Failure (MAGGIC) Is heart rate a risk marker in patients with chronic heart failure and concomitant atrial fibrillation? Results from the MAGGIC meta-analysis. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2015 Nov;17(11):1182–1191. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rienstra M., Damman K., Mulder B.A., Van Gelder I.C., McMurray J.J., Van Veldhuisen D.J. Beta-blockers and outcome in heart failure and atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013 Feb;1(1):21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kotecha D., Holmes J., Krum H., Altman D.G., Manzano L., Cleland J.G., Lip G.Y., Coats A.J., Andersson B., Kirchhof P., von Lueder T.G., Wedel H., Rosano G., Shibata M.C., Rigby A., Flather M.D., Beta-Blockers in Heart Failure Collaborative Group Efficacy of β blockers in patients with heart failure plus atrial fibrillation: an individual-patient data meta-analysis. Lancet. 2014 Dec 20;384(9961):2235–2243. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khand A.U., Rankin A.C., Martin W., Taylor J., Gemmell I., Cleland J.G. Carvedilol alone or in combination with digoxin for the management of atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003 Dec 3;42(11):1944–1951. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kotecha D., Bunting K.V., Gill S.K., Mehta S., Stanbury M., Jones J.C. Rate control therapy evaluation in permanent atrial fibrillation (RATE-AF) team. Effect of digoxin vs bisoprolol for heart rate control in atrial fibrillation on patient-reported quality of life: the RATE-AF randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020 Dec 22;324(24):2497–2508. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.23138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Digitalis Investigation Group The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997 Feb 20;336(8):525–533. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702203360801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bavendiek U., Berliner D., Dávila L.A., Schwab J., Maier L., Philipp S.A., et al. DIGIT-HF investigators and committees (see Appendix). Rationale and design of the DIGIT-HF trial (DIGitoxin to improve ouTcomes in patients with advanced chronic heart Failure): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019 May;21(5):676–684. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feinberg J.B., Olsen M.H., Brandes A., Raymond L., Nielsen W.B., Nielsen E.E., et al. Lenient rate control versus strict rate control for atrial fibrillation: a protocol for the danish atrial fibrillation (DanAF) randomised clinical trial. BMJ Open. 2021 Mar 31;11(3) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mogensen U.M., Jhund P.S., Abraham W.T., Desai A.S., Dickstein K., Packer M., et al. PARADIGM-HF and ATMOSPHERE investigators and committees. Type of atrial fibrillation and outcomes in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017 Nov 14;70(20):2490–2500. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swedberg K., Olsson L.G., Charlesworth A., Cleland J., Hanrath P., Komajda M., et al. Prognostic relevance of atrial fibrillation in patients with chronic heart failure on long-term treatment with beta-blockers: results from COMET. Eur. Heart J. 2005 Jul;26(13):1303–1308. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schneider M.P., Hua T.A., Böhm M., Wachtell K., Kjeldsen S.E., Schmieder R.E. Prevention of atrial fibrillation by renin-angiotensin system inhibition a meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010 May 25;55(21):2299–2307. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olsson L.G., Swedberg K., Ducharme A., Granger C.B., Michelson E.L., McMurray J.J., et al. CHARM investigators Atrial fibrillation and risk of clinical events in chronic heart failure with and without left ventricular systolic dysfunction: results from the candesartan in heart failure-assessment of reduction in mortality and morbidity (CHARM) program. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006 May 16;47(10):1997–2004. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swedberg K., Zannad F., McMurray J.J., Krum H., van Veldhuisen D.J., Shi H., Vincent J., Pitt B., EMPHASIS-HF Study Investigators Eplerenone and atrial fibrillation in mild systolic heart failure: results from the EMPHASIS-HF (Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization And SurvIval Study in Heart Failure) study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012 May 1;59(18):1598–1603. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu X., Liu H., Wang L., Zhang L., Xu Q. Role of sacubitril-valsartan in the prevention of atrial fibrillation occurrence in patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2022 Jan 26;17(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McMurray J.J.V., Solomon S.D., Inzucchi S.E., Køber L., Kosiborod M.N., Martinez F.A., Ponikowski P., Sabatine M.S., Anand I.S., Bělohlávek J., Böhm M., Chiang C.E., Chopra V.K., de Boer R.A., Desai A.S., Diez M., Drozdz J., Dukát A., Ge J., Howlett J.G., Katova T., Kitakaze M., Ljungman C.E.A., Merkely B., Nicolau J.C., O'Meara E., Petrie M.C., Vinh P.N., Schou M., Tereshchenko S., Verma S., Held C., DeMets D.L., Docherty K.F., Jhund P.S., Bengtsson O., Sjöstrand M., Langkilde A.M., DAPA-HF Trial Committees and Investigators Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019 Nov 21;381(21):1995–2008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Armstrong P.W., Pieske B., Anstrom K.J., Ezekowitz J., Hernandez A.F., Butler J., CSP Lam, Ponikowski P., Voors A.A., Jia G., McNulty S.E., Patel M.J., Roessig L., Koglin J., O'Connor C.M., VICTORIA Study Group Vericiguat in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 May 14;382(20):1883–1893. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weldy C.S., Ashley E.A. Towards precision medicine in heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021 Nov;18(11):745–762. doi: 10.1038/s41569-021-00566-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ponikowski P., Alemayehu W., Oto A., Bahit M.C., Noori E., Patel M.J., Butler J., Ezekowitz J.A., Hernandez A.F., Lam C.S.P., O'Connor C.M., Pieske B., Roessig L., Voors A.A., Westerhout C., Armstrong P.W., VICTORIA Study Group Vericiguat in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: insights from the VICTORIA trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2021 Aug;23(8):1300–1312. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zelniker T.A., Bonaca M.P., Furtado R.H.M., Mosenzon O., Kuder J.F., Murphy S.A., Bhatt D.L., Leiter L.A., McGuire D.K., Wilding J.P.H., Budaj A., Kiss R.G., Padilla F., Gause-Nilsson I., Langkilde A.M., Raz I., Sabatine M.S., Wiviott S.D. Effect of dapagliflozin on atrial fibrillation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: insights from the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial. Circulation. 2020 Apr 14;141(15):1227–1234. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Butt J.H., Docherty K.F., Jhund P.S., de Boer R.A., Böhm M., Desai A.S., Howlett J.G., Inzucchi S.E., Kosiborod M.N., Martinez F.A., Nicolau J.C., Petrie M.C., Ponikowski P., Bengtsson O., Langkilde A.M., Schou M., Sjöstrand M., Solomon S.D., Sabatine M.S., McMurray J.J.V., Køber L. Dapagliflozin and atrial fibrillation in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: insights from DAPA-HF. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022 Mar;24(3):513–525. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yin Z., Zheng H., Guo Z. Effect of sodium-glucose co-transporter protein 2 inhibitors on arrhythmia in heart failure patients with or without type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022 May;18(9) doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.902923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]