Abstract

Marginal zone (MZ) B cells, which are splenic innate-like B cells that rapidly secrete antibodies (Abs) against blood-borne pathogens, are composed of heterogeneous subpopulations. Here, we showed that MZ B cells can be divided into two distinct subpopulations according to their CD80 expression levels. CD80high MZ B cells exhibited greater Ab-producing, proliferative, and IL-10-secreting capacities than did CD80low MZ B cells. Notably, CD80high MZ B cells survived 2-Gy whole-body irradiation, whereas CD80low MZ B cells were depleted by irradiation and then repleted with one month after irradiation. Depletion of CD80low MZ B cells led to accelerated development of type II collagen (CII)-induced arthritis upon immunization with bovine CII. CD80high MZ B cells exhibited higher expression of genes involved in proliferation, plasma cell differentiation, and the antioxidant response. CD80high MZ B cells expressed more autoreactive B cell receptors (BCRs) that recognized double-stranded DNA or CII, expressed more immunoglobulin heavy chain sequences with shorter complementarity-determining region 3 sequences, and included more clonotypes with no N-nucleotides or with B-1a BCR sequences than CD80low MZ B cells. Adoptive transfer experiments showed that CD21+CD23+ transitional 2 MZ precursors preferentially generated CD80low MZ B cells and that a proportion of CD80low MZ B cells were converted into CD80high MZ B cells; in contrast, CD80high MZ B cells stably remained CD80high MZ B cells. In summary, MZ B cells can be divided into two subpopulations according to their CD80 expression levels, Ab-producing capacity, radioresistance, and autoreactivity, and these findings may suggest a hierarchical composition of MZ B cells with differential stability and BCR specificity.

Keywords: Marginal Zone B Cell, CD80, Autoreactivity, Radioresistance

Subject terms: Marginal zone B cells, Autoimmunity

Introduction

Three major subsets of mature B cells — B-1 cells, marginal zone (MZ) B cells, and follicular (FO) B cells — perform distinct functions in humoral immunity and immune regulation, and they form distinct layers of humoral immunity [1–3]. These cell types are distinguished by distinct transcriptional programs [4, 5] and the expression of cell surface markers, such as CD43, CD11b, CD1d, CD21, and CD23 [6, 7]. Specifically, IgMhighIgDlowCD21highCD23− MZ B cells are preactivated B cells that rapidly combat bloodborne pathogens in a T-cell-independent manner [8–10], constantly shuttling between the B cell follicle and the MZ in the spleen [11, 12]. MZ B cells are rapidly activated upon encountering antigens in circulating blood through sinusoidal fenestrae and differentiate into plasma cells that secrete low-affinity antibodies (Abs). MZ B cells also support CD4+ T-cell responses and eventually germinal center reactions as they enter the splenic T-cell or FO B-cell zones and deliver antigens to CD4+ T cells or follicular dendritic cells [10, 11, 13]. MZ B cells and CD21+CD23+ transitional 2 MZ B-cell precursors (T2-MZPs) are excellent antigen-presenting B cells that present peptide antigens and costimulatory molecules, such as CD80 and CD86, to antigen-specific CD4+ T cells; [13, 14] therefore, these cells are also involved in T-cell-dependent Ab responses [15].

Effective and specific immune responses rely on the proper selection of B cells with appropriate B cell receptors (BCRs). MZ B cell development depends on BCR-mediated signaling, but this process is less sensitive to deficiencies in BCR signaling molecules than FO B cell development [16]. Furthermore, strong BCR-mediated signaling favors the commitment of transitional B cells to the FO B cell lineage rather than the MZ B cell lineage [17]. However, some studies suggest that autoreactive B cells can become MZ B cells [18–20]. Although anti-DNA autoreactive B cells are selected out of the MZ B cells in wild-type mice, overexpression of CD40L restored these autoreactive B cells in the MZ B cell population, suggesting that T cells influence MZ B-cell selection [21]. A normal pathway of autoreactive MZ B cell development from transitional 1 MZPs (T1-MZPs) was also suggested based on a BCR repertoire analysis [22]. These autoreactive MZ B cells may cause some autoimmune diseases [23, 24]. However, how the proper MZ B-cell repertoire is selected during B-cell maturation in the spleen and how this repertoire is different from the FO B cell repertoire remain unclear [8, 22, 25]. We hypothesized that some autoreactive B cells might be normally selected into the MZ B cell population and that autoreactive MZ B cells might be discriminated from pathogen-biased, nonautoreactive MZ B cells by activation marker expression or gene expression profiles.

B cells upregulate the expression of antigen presentation-related molecules, such as CD80, CD86, and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II, in response to antigenic or innate stimuli [26, 27]. The upregulation of these molecules can be observed in autoreactive B cells that are constitutively activated via BCR engagement by self-antigens. However, regulatory mechanisms inhibit the differentiation of autoreactive B cells into effector cells [28–30]. This homeostatic state may be attributed to the expression of activation-related and/or negative regulatory molecules. We previously described a subpopulation of CD80high MZ B cells that included autoreactive type II collagen-responsive B cells in collagen-induced arthritis-susceptible DBA/1 mice [19]. In this study, we investigated the heterogeneity of the MZ B cell population based on the differential expression of activation-related molecules, transcriptional and functional differences, and differences in BCR repertoires in C57BL/6 and DBA/1 mice.

Results

CD80high marginal zone B cells are a distinct subpopulation and exhibit a highly activated phenotype and a rapid response upon BCR engagement

The heterogeneity of MZ B cells was investigated by first measuring the expression levels of CD80, CD86, MHC class II, and CD1d in developing and mature splenic B cell subpopulations from C57BL/6 and DBA/1 mice under homeostatic conditions (Fig. 1A). Compared with those in other populations, significant fractions of MZ B cells, T2-MZPs, and transitional 1 (T1) B cells from both DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice expressed high levels of CD80 but not CD86 or MHC class II. The high expression of CD80 in a subpopulation of MZ B cells was confirmed with two different anti-CD80 Ab clones (Fig. S1A). The bimodal expression of CD80 suggested that high CD80 expression can be chronically maintained in subpopulations of MZ B cells and their precursors. Given that CD80 expression is not essential for MZ B cell development [31], we hypothesized that CD80high MZ B cells are a subpopulation of MZ B cells with higher baseline activation levels.

Fig. 1.

Identification of two subpopulations of MZ B cells – CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells. Splenocytes obtained from DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice were stained with fluorescently labeled anti-B220, anti-CD24, anti-CD21, anti-CD1d, and anti-CD23 Abs. A Gating strategies for each population are shown in the left panel. The right panel shows the expression of CD80, CD86, MHC class II, and CD1d in each population from DBA/1 or C57BL/6 mice. MZ B (green); T2-MZP (black); FO B (dark gray); T1 B (light gray); T2 B (gray). Fluorescence minus one (FMO) controls are shown as black lines. The dashed straight line marks the gating for CD80high cells in each subset. B Proportions of CD80high B cells in each subset. The statistical significance of differences in each population between the DBA/1 (gray) and C57BL/6 (black) mice is indicated. C Histograms showing the expression of CD9, PD-L1, and CD5 in gated T1 B, T2 B, FO B, T2-MZP, CD80high MZ B (red), and CD80low MZ B (blue) cells. FMO control (dashed line). The values in the plots show ((MFI ± SD) × 102). The graphs present the average MFIs (× 102) of each protein in the CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells. The data represent five separate experiments. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (SEM); significance was determined by Student’s t test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns, not significant

Compared with C57BL/6 mice, DBA/1 mice showed expansion of the MZ B cell compartment, as previously described [19, 32]. The proportions of CD80high MZ B and T2-MZP cells were also higher in DBA/1 mice (40.9 ± 3.4% and 17.7 ± 2.0%, respectively) than in C57BL/6 mice (34.7 ± 2.2% and 11.3 ± 1.1%, respectively) (Fig. 1B). However, CD80high cells were more abundant among MZ B cells than among other splenic B cell subpopulations in both C57BL/6 and DBA/1 mice. Furthermore, CD80high MZ B cells expressed higher levels of PD-L1 and CD5 than did CD80low MZ B cells (Fig. 1C). CD9, which is known to be highly expressed in B-1 and MZ B cells [33], was expressed at higher levels in CD80high MZ B and T2-MZP cells than in CD80low cells from both C57BL/6 and DBA/1 mice (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1B and C).

Next, we compared BCR-mediated signaling between CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells. Although CD80high MZ B cells appeared to be activated B cells, CD80high MZ B cells did not exhibit significantly increased phosphorylation of Syk or Erk or increased expression of Irf4 or Blimp-1 at baseline (Fig. S2A). Notably, the basal phosphorylation of Btk and Akt was significantly higher in CD80high MZ B cells than in CD80low MZ B cells from DBA/1 mice but not in those from C57BL/6 mice (Fig. S2B). However, Btk and Erk, but not Syk, were more highly phosphorylated upon immunoglobulin (Ig) M BCR engagement in CD80high MZ B cells than in CD80low MZ B cells (Fig. S2C). Higher phosphorylation was more prominent for BCR-distal signaling kinases than for the BCR-proximal signaling kinase Syk. Overall, the expression level of CD80 distinguished different MZ B cell populations, and compared with CD80low MZ B cells, CD80high MZ B cells were more strongly activated and had higher expression of CD9, PD-L1, and CD5.

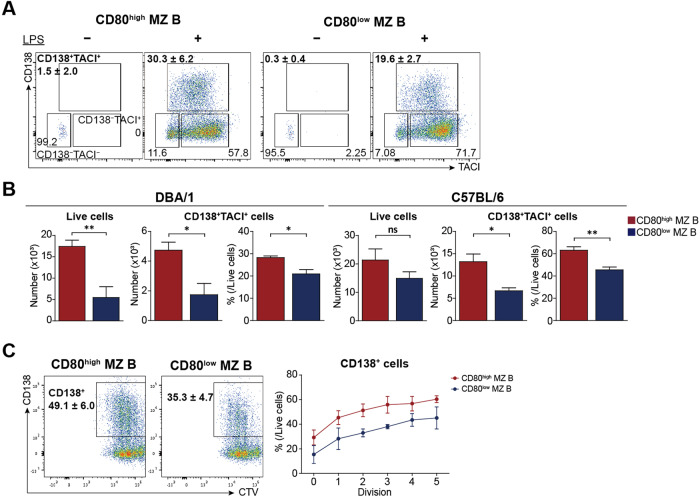

CD80high marginal zone B cells proliferate and differentiate into plasma cells more rapidly than CD80low marginal zone B cells upon LPS stimulation

MZ B cells and B-1 cells are innate-like B cells that respond well to pathogen-associated molecular patterns, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [34, 35]. Next, we compared the functional capability of CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells upon LPS stimulation. Both MZ B cell populations responded to LPS by upregulating transmembrane activator and CAML interactor (TACI) and then CD138 (Fig. 2A), but the proliferation and plasma cell differentiation ability of CD80high MZ B cells were greater than those of CD80low MZ B cells upon LPS stimulation. Additionally, there were more live CD80high MZ B cells than CD80low MZ B cells five days after LPS stimulation (Fig. 2B). Similarly, the proportions of CD138+TACI+ cells were greater among LPS-stimulated CD80high MZ B cells, suggesting that CD80high MZ B cells are more capable of activation and differentiation into plasma cells than are CD80low MZ B cells. Proliferation and concomitant plasma cell differentiation were measured by CellTrace violet dye dilution and staining with an anti-CD138 Ab (Fig. 2C). Both the sorted CD80high and CD80low MZ B cell populations exhibited plasma cell differentiation linked to proliferation. The numbers and proportions of differentiated CD138+ cells were significantly higher among CD80high MZ B cells than among CD80low MZ B cells. CD80high MZ B cells even exhibited plasma cell differentiation without single-cell division. These results suggest that compared with CD80low MZ B cells, CD80high MZ B cells exhibit heightened capacities for proliferation and differentiation into plasma cells.

Fig. 2.

CD80high MZ B cells differentiate into plasma cells more rapidly than CD80low MZ B cells. A Sorted CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells from DBA/1 or C57BL/6 mice were stimulated in vitro for five days with or without 10 μg/ml LPS. Flow cytometric plots showing the results of cells from DBA/1 mice. B Bar graphs represent the comparisons of total live cell numbers and the numbers or proportions of CD138+TACI+ plasma cells between LPS-stimulated CD80high (red) and CD80low (blue) MZ B cells from DBA/1 or C57BL/6 mice. C Sorted CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells from C57BL/6 mice were stimulated for three days with 10 μg/ml LPS in vitro. The expression levels of CD138 are shown as cell division counts tracked with CellTrace violet dye. The right panel presents the average proportions of CD138+ cells per division. Representative flow cytometry data from three separate experiments are shown. All the graphs show the means ± SEMs; the significance was determined by Student’s t test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns, not significant

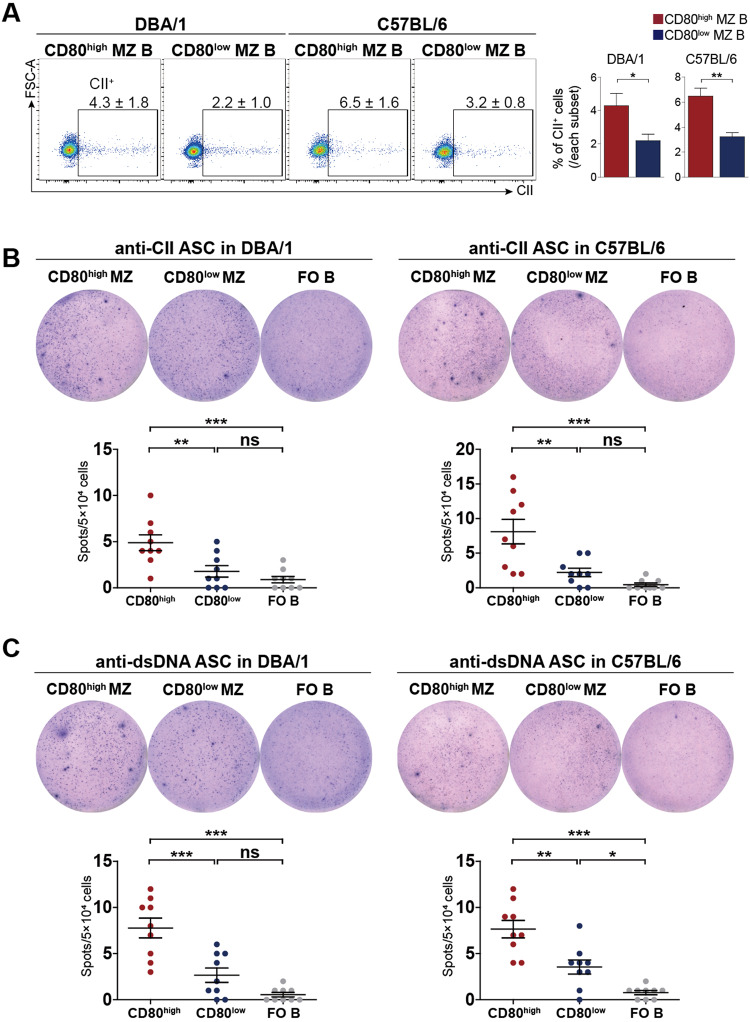

Autoreactivity and regulatory potential of CD80high marginal zone B cells

We next addressed whether CD80high MZ B cells contain B cells specific for common autoantigens, such as double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) or type II collagen (CII). The proportions of CII-binding cells, measured by flow cytometric analysis using FITC-conjugated CII, were significantly greater among CD80high MZ B cells than among CD80low MZ B cells (Fig. 3A). We further estimated the frequencies of dsDNA- or CII-specific B cells by ELISPOT assays using LPS-stimulated CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells from DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice. ELISpot assays showed that CD80high MZ B cells had significantly more anti-dsDNA or anti-CII B cells than did CD80low MZ or FO B cells from both DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 3B and C). Since FO B cells proliferate poorly upon LPS stimulation [36], FO B cells produced 0 ~ 3 autoreactive Ab-secreting spots per 5 × 104 cells. Moreover, there were significantly more autoreactive Ab-secreting spots produced by MZ B cells than by FO B cells, and CD80high MZ B cells generated 2 ~ 3.5 times more spots than did CD80low MZ B cells. These results suggest that CD80high MZ B cells are enriched in autoreactive B cells compared to CD80low MZ B cells.

Fig. 3.

CD80high MZ B cells secrete autoreactive Abs upon LPS stimulation. A Splenocytes obtained from DBA/1 or C57BL/6 mice were stained with anti-CD19, anti-CD23, anti-CD21, and anti-CD80 Abs and FITC-conjugated type II collagen (CII). The graphs present the proportions of CII+ cells among gated CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells in each subpopulation. B, C A total of 5 × 104 CD80high or CD80low MZ and FO B cells from DBA/1 or C57BL/6 mice were incubated with 10 μg/ml LPS for 48 h on CII- or double-strand DNA (dsDNA)-coated plates. The data represent three separate experiments performed in triplicate. All the data are presented as the means ± SEMs and were analyzed by Student’s t test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

The harmful effects of autoreactivity are regulated by immunoregulatory cells, such as regulatory T (Treg) or B (Breg) cells [37, 38]. Whereas Treg cells are well known to develop from autoreactive thymocytes [39], the autoreactivity of Breg cells has been described by only a few articles [40]. Breg cells can secrete IL-10 upon stimulation and may include MZ B-cell precursors and some B-1a cells; additionally, one of the cell surface markers of Breg cells is CD9 [41]. Since we found that CD80high MZ B cells exhibit some features of Breg cells, such as autoreactivity and CD9 expression, we investigated whether CD80high MZ B cells have the ability to secrete IL-10 upon activation. After stimulating sorted CD80high or CD80low MZ B cells with LPS, phorbol myristate acetate, ionomycin, and monensin for five h, the proportion of IL-10-secreting cells among CD80high MZ B cells was 10-fold higher than that among CD80low MZ B cells from C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 4A). However, the proportion of IL-10-secreting cells among stimulated CD80high MZ B cells was not significantly different from that among stimulated CD80low MZ B cells from DBA/1 mice (Fig. 4B). The difference in the IL-10 secretion potential of CD80high MZ B cells from DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice may be one of the factors that contributes to the susceptibility of DBA/1 mice to autoimmune diseases [19]. Thus, CD80high MZ B cells contain autoreactive B cells, but CD80high MZ B cells from C57BL/6 mice are also capable of secreting IL-10 upon LPS stimulation.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the IL-10 secretion capacity of CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells. Sorted CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells (1 × 105) from four C57BL/6 A and DBA/1 B mice were incubated with or without the combination of 10 μg/ml LPS, 50 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate, 2 μM ionomycin, and 2 μM monensin (LPIM) for five h. The levels of intracytoplasmic IL-10 in gated live CD19+ cells are shown (left panels of A and B). Proportions (± SDs) of IL-10-producing CD80high or CD80low MZ B cells (right panels of A and B). The data represent three separate experiments. Error bars indicate the SDs of individual values; statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test. ***p < 0.001; ns, not significant

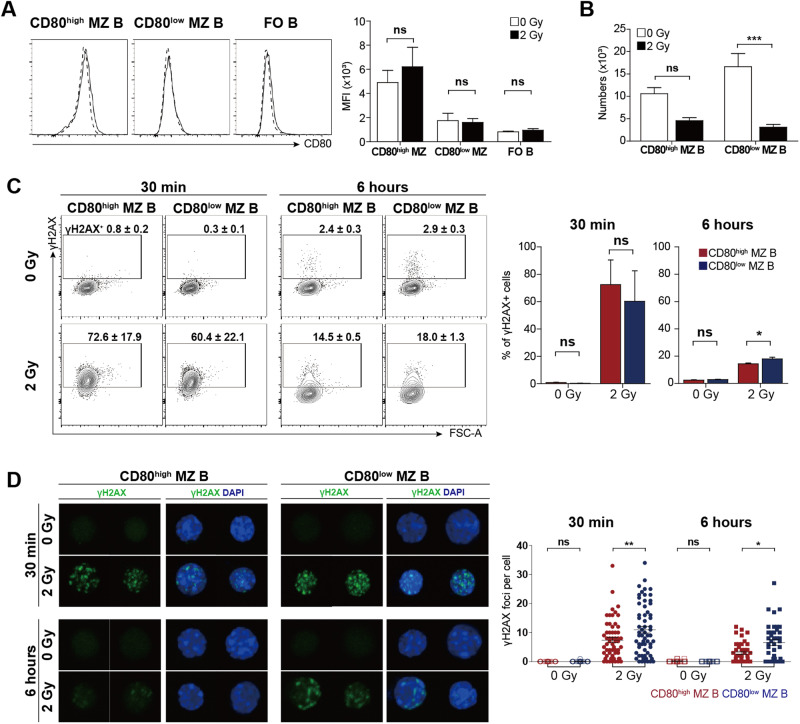

CD80high and CD80low marginal zone B cells exhibit differential radioresistance and contribute to collagen-induced arthritis development

Given that MZ B cells are known to be radiosensitive [42], we investigated whether the two MZ B cell subpopulations were equally radiosensitive. A single 2-Gy irradiation dose was used to deplete a large fraction of the splenic B cells. The spleen size was decreased markedly six h after 2 Gy irradiation (Fig. S3A), and the number of splenic B cells was decreased to the minimum level seven days after irradiation (Fig. S3B). Both FO B and MZ B cells decreased in number, but the proportion of MZ B cells among FO B cells was initially higher and was maintained at higher levels after irradiation in DBA/1 mice than in C57BL/6 mice (Fig. S3B and Fig. 5A and B). The number of C57BL/6 MZ B cells greatly decreased in response to irradiation, but the number of MZ B cells started to increase one week after irradiation (Fig. 5E and F). Notably, CD80high MZ B cells were more radioresistant than CD80low MZ B cells in both DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 5D and H). The number of CD80high MZ B cells did not decrease after irradiation in DBA/1 mice, whereas the number of CD80high MZ B cells decreased but rapidly recovered one week after irradiation in C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 5C and G). The number of CD80low MZ B cells eventually recovered to a homeostatic level approximately one month after irradiation in both DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice. The expression levels of CD86, CD9, and CD1d did not change in the CD80high and CD80low MZ B cell subpopulations during the early and late postirradiation periods, which suggested the phenotypic stability of the two MZ B cell subpopulations (Fig. S3C).

Fig. 5.

CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells exhibit differential radiosensitivity and repopulation kinetics after irradiation. DBA/1 A–D or C57BL/6 E–H mice were irradiated (2 Gy), and splenocytes were analyzed at the indicated time points after irradiation. Nonirradiated DBA/1 mice were used as a control (Day 0). Splenocytes were stained with fluorescently labeled anti-B220, anti-CD23, anti-CD21, and anti-CD80 Abs. Flow cytometric plots show the expression of CD21 and CD23 in gated B220+ cells and the expression of CD80 in gated FO B (filled gray) or MZ B (black) cells (A and E). The numbers in the upper corners are the proportions of total MZ B cells that were CD80high (red gate) or CD80low (blue gate). Proportions of CD21–CD23– (DN), T2-MZP, MZ B, or FO B cells (B and F). Proportions of CD80high or CD80low MZ B cells among total MZ B cells (C and G). Numbers of CD80high or CD80low MZ B cells at the indicated time points (D and H). The data represent three separate experiments. Error bars indicate the SEM; significance was based on Day 0 and determined by ANOVA. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns, not significant; dpi, days postirradiation

Since we defined MZ B cell subpopulations based on CD80 expression, we next investigated the possibility that CD80low MZ B cells convert to CD80high MZ B cells upregulating the expression of CD80 upon irradiation. This possibility was excluded because CD80high MZ B cells, CD80low MZ B cells, or FO B cells that were irradiated in vitro did not upregulate CD80 expression (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, the radiosensitivity of CD80low MZ B cells in vivo was recapitulated by the higher radiosensitivity of sorted CD80low MZ B cells compared with that of sorted CD80high MZ B cells in vitro (Fig. 6B). Radiation (2 Gy) induced the accumulation of phosphorylated histone H2AX (γH2AX), a marker of double-stranded DNA breaks [43], in both CD80low and CD80high MZ B cells from both DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice after 30 min (Fig. 6C and Fig. S3D). However, delayed resolution of γH2AX was observed in CD80low MZ B cells from DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice compared to the respective CD80high MZ B cells six h after irradiation; these results suggested that DNA repair is delayed in CD80low MZ B cells. The increase in γH2AX foci in CD80high MZ B cells was further confirmed by immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 6D). In summary, the CD80high and CD80low MZ B cell subpopulations substantially differ in radioresistance both in vivo and in vitro.

Fig. 6.

Expression of CD80 and phosphorylation of histone H2AX before and after irradiation. A Sorted CD80high or CD80low MZ B cells and FO B cells from DBA/1 mice were incubated for six h after 0 or 2 Gy irradiation in vitro. Histograms show the expression of CD80 in live B220+ cells. The bar graph shows the average MFI values of CD80 expression. B Splenic B cells were obtained from DBA/1 mice and subjected to 2 Gy irradiation. The numbers of live gated CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells were determined after six h of culture. C Splenocytes from DBA/1 mice were incubated for 30 min or six h after 2 Gy irradiation and stained with an anti-γH2AX Ab. The graphs show the proportions of phosphorylated H2AX+ (γH2AX+) cells among the gated CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells. D Purified CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells from DBA/1 mice were incubated for 30 min or six h after 0 or 2 Gy irradiation in vitro. Immunofluorescence images showing γH2AX foci in representative cells. The right-hand graphs show the counts of γH2AX foci per cell (n ≥ 20 for 0 Gy; n ≥ 40 for 2 Gy). Error bars indicate the SEM; significance was determined by ANOVA. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001; ns, not significant

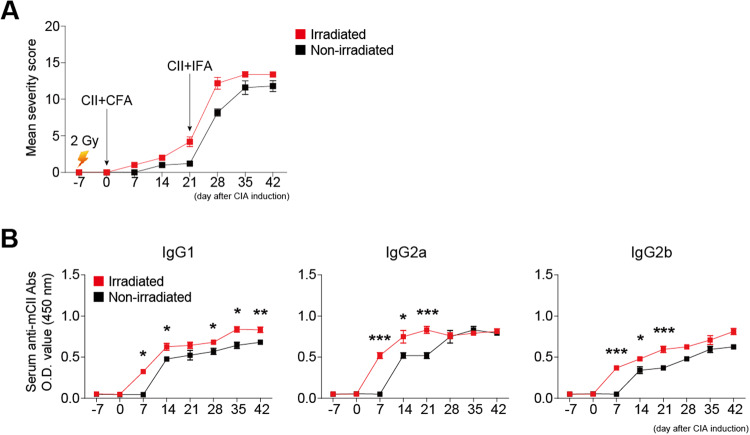

To investigate the functional differences between CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells, we selectively depleted CD80low MZ B cells by 2 Gy irradiation and investigated whether the collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) was exacerbated or ameliorated by the change in the MZ B cell composition. After immunization with bovine CII seven days after 2 Gy irradiation, the severity of CIA and increase in anti-mouse CII IgG Ab production were accelerated compared to those in DBA/1 mice immunized without irradiation (Fig. 7A and B). These findings suggest that radioresistant CD80high MZ B cells promote CIA and may contribute to radiation-induced autoimmune diseases.

Fig. 7.

Collagen-induced arthritis progression was accelerated after the depletion of CD80low MZ B cells by irradiation. On Day -7, 2 Gy-irradiated or nonirradiated DBA/1 mice were intradermally injected at the base of the tail with 100 μl of an emulsion (bovine CII + complete Freund’s adjuvant; dose of 200 μg of CII per mouse) on Day 0 and boosted with bovine CII + incomplete Freund’s adjuvant on Day 21. A The severity of collagen-induced arthritis was monitored and scored using the Chondrex mouse arthritis scoring system. B Serum anti-CII Abs of the indicated IgG subclasses

CD80high marginal zone B cells exhibit high expression of genes related to the antioxidant response, negative regulation of immune responses, and lymphocyte activation

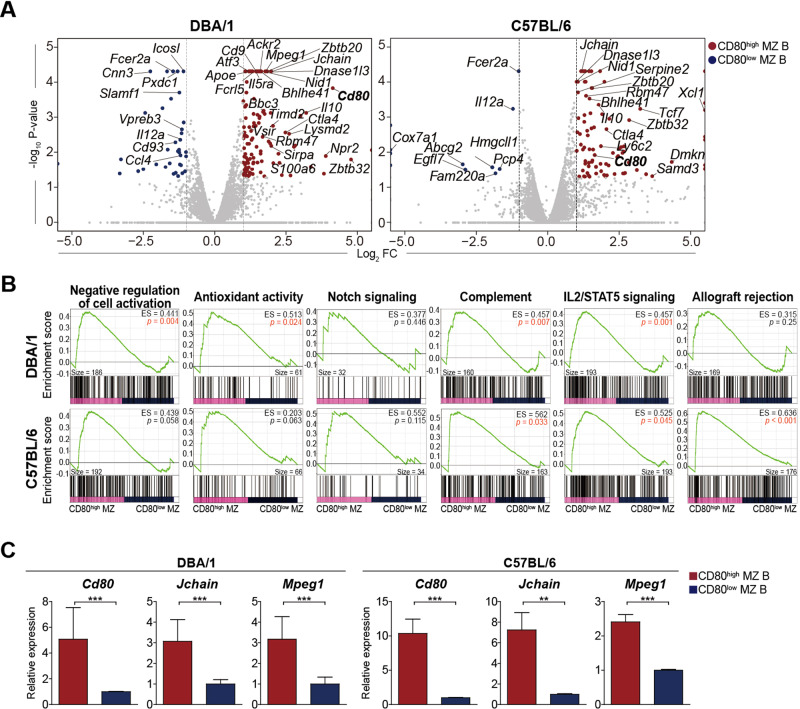

Transcriptome analysis was also conducted to elucidate the differences in gene expression between CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells from DBA/1 or C57BL/6 mice. A total of 156 and 106 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the two MZ B cell subpopulations were identified in DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice, respectively (Fig. 8A and Table S1). A total of 119 and 95 genes were upregulated in CD80high MZ B cells from DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice, respectively (Table S1A and B). Many upregulated DEGs were categorized as Breg cell signature genes, plasma cell surface markers, or plasma cell transcription factors, but the differences in the expression of B-cell transcription factor genes were not significant (Figs. S4A and S5) [44, 45]. Moreover, 37 and 11 genes were downregulated in CD80high MZ B cells from DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice, respectively (Table S1C and D). Among the DEGs, 23 upregulated and 2 downregulated DEGs were shared between CD80high MZ B cells from DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice. The 23 shared upregulated DEGs in CD80high MZ B cells included genes implicated in the regulation of inflammation (Cd80, Ctla4, Il10, Atf3, Axl, Dnase1l3, Rbm47, Nid1, and Rap1gap2), in the proinflammatory pathway (Ahnak and Axl), in plasma cell differentiation (Jchain, Prdm1, Zbtb20, Zbtb32, and Tent5c), in radioresistance (Actn1), in survival (Atp11a), and in the innate function of B cells (Bhlhe41, Gpr55, Lmo7, and Ahnak). The two shared downregulated DEGs in CD80high MZ B cells were Fcer2b (CD23) and Il12a.

Fig. 8.

Gene expression comparison between CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells. RNA transcriptome analysis was performed using 21,915 or 21,853 genes that were identified in CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells sorted from DBA/1 mice or C57BL/6 mice, respectively. A Volcano plots comparing transcriptomes of CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells. Symbols indicate genes with significant differences (p ≤ 0.05 and |log2-fold change| ≥ 1); CD80high MZ B (red), CD80low MZ B (blue), or no significance (gray). B Enrichment plots generated by gene set enrichment analyses. The genes were assigned to the following gene sets: negative regulation of cell activation (GO:0050866), antioxidant activity (GO:0016209), positive regulation of the notch signaling pathway (GO:0045747), complement, IL2/STAT5 signaling, and allograft rejection. A nominal p value of 0.05 was used to assess the significance of gene set enrichment (p < 0.05, marked in red). ES, enrichment score; p, nominal p value. C qRT‒PCR analysis was performed to compare the expression of Cd80, Jchain, and Mpeg1 in CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells from DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice. Bar graphs show the means ± SEMs of three independent experiments. Student’s t test was performed to determine statistical significance. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

The top Gene Ontology (GO) terms enriched in CD80high MZ B cells from both DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice included negative regulation of cell activation (GO:0050866), negative regulation of immune system process (GO:0002683), response to LPS (GO:0032496), antioxidant activity (GO:0016209), and lymphocyte proliferation (GO:0046651) (Fig. S4B). According to the gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) plots generated from the GO gene sets, genes involved in the negative regulation of cell activation and antioxidant activity were significantly enriched in CD80high MZ B cells from DBA/1 mice and in MZ B cells from C57BL/6 mice (p = 0.058 and 0.063, respectively; Fig. 8B). We inferred that the higher antioxidant activity of CD80high MZ B cells than that of CD80low MZ B cells was correlated with radioresistance, whereas the higher expression of genes related to the negative regulation of cell activation was associated with the regulatory function of CD80high MZ B cells. The hallmark gene sets that were enriched in CD80high MZ B cells from both DBA/1 and C57BL/6 strains included gene sets related to epithelial mesenchymal transition, coagulation, IL-2-STAT5 signaling, complement, and Kras signaling_down (Fig. S4C). GSEA plots showed that CD80high MZ B cells were significantly enriched in genes involved in IL-2/STAT5 signaling and complement regulation in both DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 8B). The enrichment of genes associated with IL-2/STAT5 signaling and complement was thought to be correlated with the level of activation and control of inflammation, respectively. The hallmark gene set for allograft rejection, which includes both anti-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory genes, was significantly enriched in CD80high MZ B cells from C57BL/6 mice but not in CD80high MZ B cells from DBA/1. The expression of the hallmark gene set for Notch signaling, which is essential for MZ B-cell development, did not differ between CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells. Some of the differences in gene expression were further confirmed by qRT‒PCR using CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells purified from DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 8C). The expression of CD80 was confirmed to be regulated at the transcription level. Collectively, the DEG analyses showed that CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells differed significantly in terms of the expression of genes related to antioxidation activity, negative and positive regulation of B cell activation, and regulation of inflammation.

The immunoglobulin heavy chain repertoire of CD80high marginal zone B cells contains clonotypes that are distinct from those of CD80low marginal zone B cells

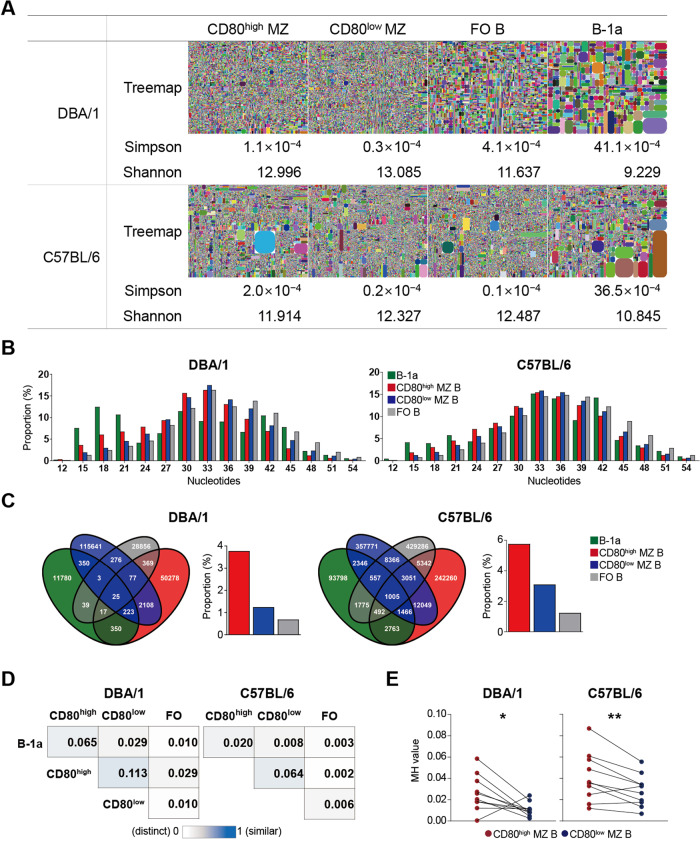

We next investigated whether the BCR repertoire of CD80high MZ B cells is different from that of CD80low MZ B cells. The IgH chain repertoires of four B cell populations—CD80high MZ B cells, CD80low MZ B cells, FO B cells, and peritoneal B-1a B cells—from DBA/1 or C57BL/6 mice were compared with respect to the levels of diversity, similarity and length of complementary-determining region 3 sequences (CDR3s). We obtained more than 4.5 × 105 reads from each subset (Table S2). The number of unique clonotypes identified based on the VDJH or CDR3 sequences was highest for CD80low MZ B cells and FO B cells from DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice, respectively, and lowest for B-1a cells in both mouse strains. CD80low MZ B cells and FO B cells were the most diverse subpopulations in DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice, respectively, as measured by the Shannon and Simpson indices (Fig. 9A). Notably, the IgH clonal diversity of CD80high MZ B cells was lower than that of CD80low MZ B cells, suggesting that some frequent clonotypes were present in CD80high MZ B cells. Compared to CD80low MZ B cells, CD80high MZ B cells contained several highly repetitive clonotypes that were also found in B-1a cells (Tables S3 and S4).

Fig. 9.

CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells exhibit distinct immunoglobulin heavy chain repertoires. A total of 2 × 105 peritoneal B-1a cells were pooled from seven DBA/1 or C57BL/6 mice, and 1 × 106 CD80high MZ B cells, CD80low MZ B cells, and FO B cells that were pooled from three mice of each strain were used for Ig heavy chain repertoire analysis. A Treemap and diversity indices. Shannon indices were calculated for the top 10,000 clonotypes. B The length distribution of CDR3s showing the proportion of sequences according to the number of nucleotides. C Venn diagram displaying the number of overlapping clonotypes (unique VDJH) between the indicated repertoires. The graphs show the proportion of reads of clonotypes in the indicated cell subsets that overlapped with B-1a cells. D Heatmap displaying Morisita–Horn similarity (MH) indices comparing the repertoires of given combinations. E MH values comparing the heavy chain repertoires of CD80high or CD80low MZ cells to those of B-1a cells. The top 10 V-J combinations in the B-1a cell repertoire were analyzed to determine the use of B-1a cell clonotypes in identifying MZ B cell subpopulations. From top to bottom: V7-3/J2, V3-2/J2, V2-9/J4, V3-2/J1, V3-6/J2, V1-4/J2, V3-2/J4, V2-9/J2, V1S55/J4, and V1-26/J2 in DBA/1; V1-55/J4, V1-55/J1, V2-9/J4, V2-2/J4, V1-53/J2, V6-6/J2, V7-3/J4, V1-55/J2, V10-1/J4, and V1-19/J2 in C57BL6 mice. The MH values range from 0 (white, distinct) to 1 (blue, similar). Significance was determined by paired Student’s t test; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

The frequencies of V segment usage and mutation rates were similar between the CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells from both DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice (Fig. S6A and B). When we compared the CDR3 lengths of IgH clonotypes in the B cell subpopulations, we found that CD80high MZ B cells contained more clonotypes with shorter CDR3s and fewer N nucleotides than did CD80low MZ B cells from both DBA/1 and C57BL6 mice (Fig. 9B and Fig. S6C). Since B-1a cells have highly frequent clonotypes with short CDR3 lengths, we investigated whether CD80high MZ B cells possessed clonotypes shared with B-1a cells. The number of shared clonotypes between B-1a and CD80low MZ B cells was higher than that between B-1a cells and CD80high MZ B cells, but the proportion of shared clonotypes between B-1a cells and CD80high MZ B cells was higher than that between B-1a and CD80low MZ B cells in both DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 9C). The shared CDR3 clonotypes between B-1a cells and CD80high MZ B cells are listed in Table S3A and B. The top 30 highly recurring CDR3 sequences of B-1a cells were more frequently found in the CDR3s of CD80high MZ B cells than in those of CD80low MZ B or FO B cells (Table S3A and B). Seven and five CDR3 clonotypes from the top 20 highly recurring CDR sequences of the respective DBA/1 and C57BL/6 CD80high MZ B cells were also found among the B-1a cell clonotypes, whereas only one of the top 20 CDR3 in CD80low MZ B cell clonotypes from DBA/1 mice and none of the top 20 CDR3 in CD80low MZ B cell clonotypes from C57BL/6 mice were found among the B-1a cell clonotypes (Table S4A and B). Overall, approximately 3.76% and 5.73% of the CDR3 clonotypes from the CD80high MZ B cells from DBA/1 and C57BL/6, respectively, but only approximately 1.23% and 3.08% of the CDR3 clonotypes from the CD80low MZ B cells from DBA/1 and C57BL/6, respectively, were shared with the B-1a cell clonotype (Table S5A and B). A comparison of the Morisita-Horn (MH) similarity indices, which account for both the number of common clonotypes and the distribution of clone sizes [46], revealed that the CD80high MZ B-cell repertoire was distinct from the CD80low MZ B-cell repertoire in both DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice, although they shared more clonotypes than the other repertoires. Notably, we observed higher MH indices between B-1a and CD80high MZ B cells than between B-1a and CD80low MZ B or FO B cells in both DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 9D). To analyze the B-1a cell clonotypes present in the MZ B-cell subpopulations in detail, we compared the MH indices between the MZ B-cell subpopulations and B-1a cells in V-J combinations repetitively encountered in B-1a cells (Fig. 9E). For 9 out of the 10 B-1a V-J combinations, the MH indices between CD80high MZ B cells and B-1a cells were higher than those between CD80low MZ B cells and B-1a cells in both mouse strains. The higher similarity of CD80high MZ B cells to B-1a cells was significantly different from that of CD80low MZ B cells to B-1a cells. Furthermore, CDR3 clonotypes previously found in phosphatidylcholine-specific B cells were more frequently observed in CD80low MZ B cells than in CD80high MZ or FO B cells (Table S6). In summary, CD80high MZ B cells expressed a distinct IgH repertoire with frequent clonotypes shared with B-1a cells in both DBA/1 and C57BL/6 mice.

Conversion of CD80low marginal zone B cells into CD80high marginal zone B cells

Next, we addressed the developmental pathways of CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells and the relationship between the two subpopulations. To determine whether one of the two subpopulations developed earlier, the proportions of CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells among the total MZ B cells were measured in neonatal and adult C57BL/6 mice (Fig. S7A). MZ B cells increasingly accumulate with age, and CD80low MZ B cells appeared to accumulate earlier than CD80high MZ B cells. We further addressed the time-dependent development of CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells after MZ B cell depletion with intravenous injection of Abs targeting the α4 and αL integrins (Fig. S7B). Here, after the depletion of MZ B cells, CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells appeared almost simultaneously at 14 days postinjection. We speculated that CD80low MZ B cells might develop earlier than CD80high MZ B cells.

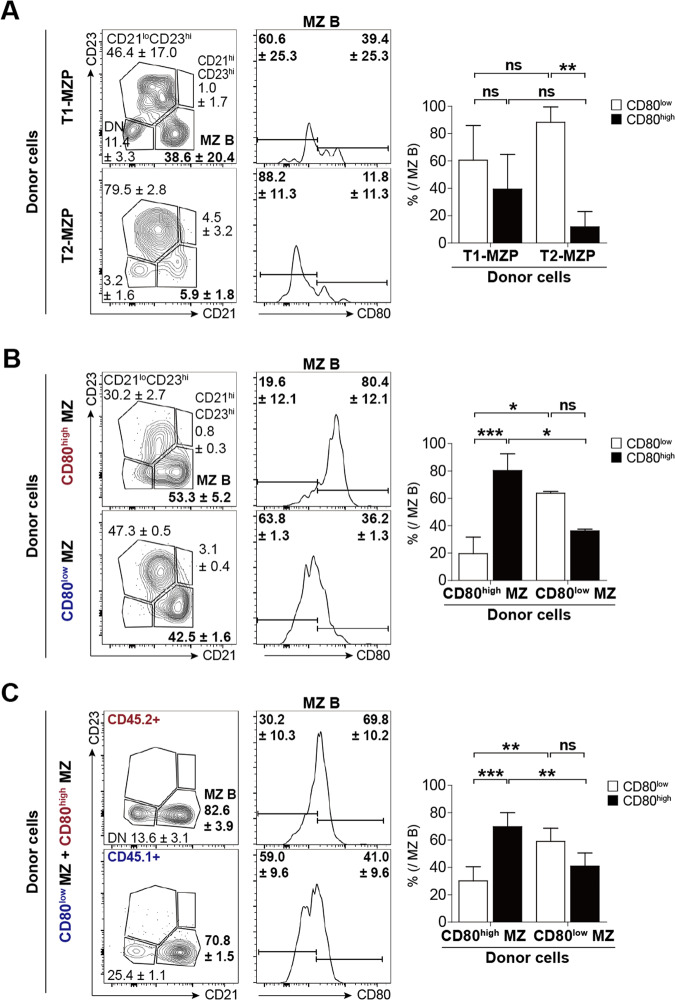

We next performed adoptive transfer experiments using CD45.2+ T1-MZPs or T2-MZPs and CD80high or CD80low MZ B cells and followed their subsequent development or stability in CD45.1+ host mice (Fig. 10A and B). Sorted CD93+CD21+CD23– T1-MZPs or CD21+CD23+ T2-MZPs were adoptively transferred into CD45.1+ C57BL/6 mice (Fig. S7C). Notably, T1-MZPs expressed high levels of CD1d, and approximately half of the T1-MZPs were CD80high, suggesting that there may be two different subpopulations of MZPs. T1 cells, except for T1-MZPs, did not express CD80. Adoptively transferred CD45.2+ T2-MZPs matured into FO and MZ B cells, and 88.2% of the MZ B cells were CD80low, showing that CD80low MZ B cells were preferentially generated (Fig. 10A). The development of MZ B cells from adoptively transferred T1-MZPs was not efficient, but rather, low numbers of both CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells were generated. Next, we investigated whether CD80low MZ B cells generate CD80high MZ B cells and vice versa (Fig. 10B). Whereas approximately half of the CD80high MZ B cells were CD80high MZ B cells, 47 and 26% of the CD80low MZ B cells were converted into FO B cells and CD80high MZ B cells, respectively. Notably, CD80low MZ B cells were not a stable MZ B cell subpopulation. When we adoptively transferred CD45.2+ CD80high and CD45.1+ CD80low MZ B cells into Rag1–/– hosts, almost no FO B cells were observed at six weeks posttransfer (Fig. 10C). Interestingly, approximately 70% of CD80high and 59% of CD80low MZ B cells maintained their expression levels of CD80. However, the conversion of CD80low MZ B cells to CD80high MZ B cells was more pronounced than was the reverse conversion. In summary, CD80low MZ B cells and CD80high MZ B cells were interconvertible, but not equivalent, since CD80low MZ B cells were less stable than CD80high MZ B cells.

Fig. 10.

Analysis of reconstituted B cell subpopulations upon adoptive transfer of T1-MZPs, T2-MZPs, CD80high MZ B cells, or CD80low MZ B cells into wild-type or Rag1-/- mice. A A total of 0.5–1 × 105 CD93+CD21+CD23– T1-MZPs or CD21+CD23+ T2-MZPs obtained from CD45.2+ mice were intravenously transferred into CD45.1 mice, and the spleens were harvested seven or four days after transfer, respectively. The gating strategy is shown in Supplementary Fig. 7C. B A total of 1 × 106 CD45.2+ CD80high (red) or CD80low (blue) MZ B cells were intravenously transferred into CD45.1 mice, and the spleens were harvested seven days after transfer. C A total of 3 × 105 CD45.2+ CD80high MZ (red) and CD45.1+ CD80low MZ (blue) B cells were simultaneously transferred into Rag1−/− mice, and the spleens were harvested at six weeks after transfer. The splenocytes obtained from host mice were stained with anti-CD19, anti-CD45.1, anti-CD45.2, anti-CD21, anti-CD23, and anti-CD80 Abs. Donor-derived cells in host mice were distinguished by gating CD45.2+ or CD45.1+ cells from live CD19+ B cells. The right-hand graphs show the relative proportions of CD80high and CD80low MZ cells in each transfer and reconstitution experiment. The data represent three (A and B) or four (C) separate experiments. The values on the flow cytometric plots are presented as the means ± SDs. Error bars indicate the SDs of individual values; significance was determined by Student’s t test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Discussion

MZ B cells are preactivated B cells that are localized in the splenic MZ and are ready to rapidly respond to blood-circulating pathogens. MZ B cells have a lower threshold for activation than FO B cells because the transcriptional network is established differently [47]. MZ B cells are a functionally unique subset of B cells and phenotypically well-defined but have long been thought to be composed of heterogeneous subpopulations since multiple pathways may lead to the development of these memory-like or innate-like B cells. In this study, we demonstrated that MZ B cells are divided into two distinct subpopulations according to their CD80 expression, radioresistance, Ab-producing capacity, and IL-10 secretion. Notably, the CD80high MZ B cell and CD80low MZ B cell subpopulations were not equivalent in terms of the hierarchy of MZ B cell differentiation. CD80high MZ B cells were stable, resistant to irradiation, and functionally active, whereas CD80low MZ B cells were unstable and could be converted into FO B or CD80high MZ B cells in adoptive transfer experiments. This hierarchy is analogous to that of IgMlowIgDhigh FO-I B cells and IgMhighIgDhigh FO-II B cells [48]. In the hierarchy of FO B cells, more autoreactive B cells proceed to FO-I cells, whereas fewer autoreactive B cells proceed to and stop at the FO-II cell stage [17]. However, whether BCR signaling alone determines the differentiation or maturation of MZ B cells or whether other factors, such as cytokines or T cells, help influence MZ B cell differentiation need to be further investigated.

MZ B cells have long been suggested to be heterogeneous by several different arguments. Based on their functional capacities upon antigenic challenge, MZ B cells are functionally divided into early Ab-forming or late germinal center-forming cells [49]. Recently, the expression of atypical chemokine receptor (Ackr) 3 was shown to be required for MZ formation [50]. Ackr3+ MZ B cells differentiate into CD138+B220low plasma cells more rapidly than Ackr3− MZ B cells after TLR stimulation, as these cells share features of CD80high MZ B cells. However, compared with CD80low MZ B cells, CD80high MZ B cells did not express higher levels of Ackr3 mRNA but rather expressed Ackr2 mRNA at higher levels than CD80low MZ B cells. Therefore, the categorization of MZ B cells based on CD80 expression does not align with categorization based on Ackr3 expression, which may suggest multidimensional heterogeneity of MZ B cells.

Expansion of autoreactive MZ B cells is associated with several autoimmune diseases [51, 52]. Mechanistically, it is important to know whether autoreactive MZ B cells abnormally develop in the disease environment or are already present in healthy individuals. The latter possibility is favored by this study and other previous reports using BCR transgenes with low-level autoreactivity [52–54]. Overall, we believe that the MZ B cell compartment normally contains a substantial number of autoreactive B cells, which expand further in autoimmune diseases. Dysregulated activation of autoreactive MZ B cells may be a mechanism by which autoimmune diseases are initiated; therefore, maintaining the homeostasis of the MZ B cell population is important. Notably, the MZ B cell compartment is expanded in several mouse strains, such as DBA/1 or nonobese diabetic (NOD) strains, which are susceptible to B cell-mediated autoimmune disease [19, 24], or in mice with some BCR transgenes before the disease appears [54, 55].

It is not well understood what determines the commitment of transitional B cells to the MZ B cell or FO B cell lineage [16, 56]. According to the BCR signaling strength hypothesis, strong BCR signaling inhibits the selection of transitional B cells into the MZ B cell population by blocking Notch2 signaling, whereas weak BCR signaling is permissive for Notch2-mediated MZ B-cell differentiation [17]. However, this hypothesis conflicts with the observation that MZ B cells produce autoreactive Abs in autoimmune diseases, in certain BCR-transgenic mice, or even in normal mice [10, 21, 52, 55–57]. The existence of autoreactive MZ B cells may be explained by the presence of other pathways involved in autoreactive MZ B-cell development. The BCR repertoire of MZ B cells is distinct from that of B-1a cells, but a population of B-1-like MZ B cells with BCRs lacking N-nucleotide additions was reported; however, this study did not observe many B-1a BCR specificities [22]. It was argued that these B-1-like MZ B cells develop from T1-MZPs, whereas T2 transitional B cells with N-nucleotide additions are generated by N-nucleotide+ MZ B cells as well as by FO B cells via T2-MZPs. Our data are compatible with this previous report, as high expression of CD80 was also observed in a subpopulation of T1 B cells. Our adoptive transfer experiments showed that both T1-MZPs and T2-MZPs preferentially generated CD80low MZ B cells. Therefore, we presume that CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells develop via different pathways.

CD80high MZ B cells exhibited interesting characteristics related to signaling and plasma cell differentiation. The cells showed heightened signaling upon stimulation with anti-IgM Abs or LPS. The heightened signaling of CD80high MZ B cells caused them to vigorously proliferate and differentiate into Ab-secreting cells even without a single cell division compared to that in the CD80low MZ B cells. Whereas FO B cells require multiple divisions to become plasma cells [58], MZ B cells become plasma cells after only second to third divisions [59]. CD80high MZ B cells were even more efficient at proliferating and differentiating into Ab-secreting cells than were CD80low MZ B cells. We think that this efficiency of CD80high MZ B cells may be achieved by increased signaling upon stimulation with anti-IgM or LPS [60].

CD80 and CD86 are two representative costimulatory molecules that bind to CD28 or CTLA-4 and result in T-cell activation or inhibition [61]. CD80 and CD86 are functionally distinct: whereas CD86 expression is induced rapidly and strongly upon B-cell activation and engages CD28 to promote T-cell costimulation, CD80 expression is induced weakly and slowly and is a major ligand for CTLA4 [26, 62–64]. Notably, the expression of CD80 persists in some B cell populations, as CD80 is expressed on murine unmutated and human memory B cells [65, 66]. The features of CD80high MZ B cells corresponded to the previously described CD80+ unmutated memory B cells.

The immunoregulatory property of CD80high MZ B cells is striking. IL-10 was more strongly expressed by CD80high MZ B cells than by CD80low MZ B cells. IL-10 secretion is a major feature that defines regulatory B cells, but regulatory B cells have other mechanisms for immune regulation, including cell‒cell interactions [67]. The full regulatory functions of CD80high MZ B cells have yet to be addressed. However, the expression of Ackr2 in CD80high MZ B cells is interesting because Ackr2 is known to regulate inflammation by scavenging inflammatory chemokines [68, 69].

The BCR specificities and repertoire of CD80high MZ B cells were investigated in this study, and the results demonstrated the presence of autoreactive B cells in this population. We observed the presence of anti-CII and anti-dsDNA B cells among CD80high MZ B cells. We presume that CD80high MZ B cells may secrete autoreactive and polyspecific Abs during infection. Although autoreactivity and polyspecificity may cause self-destruction, self-destruction is considered self-limited since autoreactive Ab-secreting cells are short lived [70–73]. The autoreactivity and polyspecificity of a substantial fraction of BCRs are inevitable and may even prove useful in protecting the host against pathogens in the early phase of infection [74]. We hypothesize that MZ B cells include fewer autoreactive CD80low MZ B cells that are specific to common pathogens and more autoreactive CD80high MZ B cells that include polyspecific B cells. As CD80high MZ B cells respond more rapidly to stimulation, they may act earlier in the course of infection than CD80low MZ B cells. We showed that the immunoglobulin heavy chain repertoire of CD80high MZ B cells was distinct from that of CD80low MZ B cells and included some B-1a cell specificities, which suggested that CD80high MZ B cells have some autoreactive specificities.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that MZ B cells are composed of two distinct subpopulations that differ in terms of autoreactivity, radiosensitivity, and functional capacity. The differential regulation of these cell populations may be exploited to treat autoimmune diseases or infectious diseases.

Materials and methods

Mice, irradiation, and collagen-induced arthritis induction

Wild-type C57BL/6 and DBA/1 mice were purchased from Orient Bio (Seongnam, Korea) and B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ (CD45.1) and B6.129S7-Rag1tm1Mom/J (Rag1−/−) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). The mice were maintained in the Laboratory Animal Research Center of Sungkyunkwan University. From two to four-week-old DBA/1 mice were obtained via in-house breeding within this facility. To deplete MZ B cells, C57BL/6 mice were intravenously injected with 100 μg each of blocking Abs against integrin α4 and blocking Abs against αL (BioXCell, West Lebanon, USA), and flow cytometric analysis of splenic and blood cells was performed after various durations. All the procedures were performed in a pathogen-free facility according to institutional guidelines. This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine (permission number SKKUIACUC2023-05-25-1).

For irradiation experiments, mice or purified splenic cells were irradiated with a 137Cs Gammacell source (IBL 437 C; CIS Bio International, Bangnols Sur Ceze, France) until a dose of 2 Gy was achieved. Mice that were subjected to whole-body irradiation were maintained in the animal facility, and splenocytes were obtained six h to seven weeks after irradiation for subsequent analyses. For in vitro irradiation, the sorted cells were irradiated and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GeneDEPOT Barker, TX, USA) and 100 μg/ml penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco).

To study the effect of irradiation on CIA induction, ten-week-old male DBA/1 mice that had been irradiated with 2 Gy or not for 7 days before injection were intradermally injected at the base of the tail with 100 μl of an emulsion (200 μg of bovine CII plus an equal volume of complete Freund’s adjuvant; Chondrex, Redmond, WA, USA) on Day 0. The mice were then boosted with bovine CII plus incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (Chondrex) on Day 21. The severity of collagen-induced arthritis was scored according to the Chondrex mouse arthritis scoring system [19], and serum samples were collected on the indicated days to measure anti-CII Ab levels.

Cell preparation and flow cytometric analysis

Single-cell suspensions were obtained from 8 to 12-week-old mice by mechanically disrupting the spleens or flushing the serosal cavities with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and passing the suspensions through nylon membranes. After the red blood cells were lysed and washed, the purified cells were stained on ice for 30 min with combinations of fluorochrome-conjugated Abs in fluorescence-associated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (5% newborn bovine calf serum and 0.05% sodium azide in PBS). Fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal Abs against the following antigens were used: CD80 (16-10A1, biotinylated), CD86 (GL1), and phospho-Akt (pT308) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA); CD80 (1G10) and anti-rat IgG (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL, USA); CD19 (1D3), CD21/CD35 (7E9), CD5 (53-7.3), CD9 (MZ3), CD24 (M1/69), CD138 (281-2), TACI (8F10), I-A/I-E (M5/114.15.2), CD1d (1B1), PD-L1 (10F9.G2), IgM (AF6-78), CD45.2 (104), Irf4 (IRF4.3E4), Blimp1 (5E7), phospho-H2AX (2F3), and streptavidin-conjugated with brilliant violet 421, phycoerythrin, or allophycocyanin (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA); B220 (RA3-6B2), CD23 (B3B4), CD93 (AA4.1), CD45.1 (A20), phospho-Syk (Moch1ct), phospho-Btk/Itk (M4G3LN), phospho-Erk (MILAN8R), and IL-10 (JES5-16E3) (eBioScience, San Diego, CA, USA); and FITC-conjugated CII (Sigma‒Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

The expression levels of cell surface proteins were determined using fluorescence minus one control sample. Then, the stained cells were washed with FACS buffer. The data were acquired using a BD FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences) at the BIORP of Korea Basic Science Institute and analyzed using FlowJo software (BD Biosciences). To stain intranuclear or cytoplasmic Irf4, Blimp1, phospho-Syk, phospho-Btk, phospho-Erk, phospho-Akt, phospho-H2AX, and IL-10, cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (Sigma‒Aldrich) at 4 °C for 1 h and permeabilized in 0.05% Triton X-100 (Sigma‒Aldrich) at room temperature (RT) for 30 min.

Cell sorting, culture, and adoptive transfer

B cells were separated by magnetic-activated cell sorting using the MagniSortTM Mouse B cell Enrichment Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Briefly, splenocytes were stained with enrichment Ab cocktails, which included biotinylated anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD11b, anti-CD49b, anti-Ly6G, and anti-TER-119 Abs in FACS buffer at RT for 10 min; then, the cells were washed and incubated with negative selection beads at RT for 5 min. Without washing, a tube containing cells that were incubated with beads was inserted into the magnet (eBioscience) and maintained at RT for 5 min. B cells were collected by harvesting the supernatant from the tube into a collection tube.

The cells were sorted by flow cytometry with a FACSAria III (BD Biosciences); splenic CD80high or CD80low MZ or FO B cells were separated after staining with anti-B220, anti-CD21, anti-CD23, and anti-CD80 Abs in FACS buffer. Peritoneal B-1a cells were separated after staining with anti-CD19, anti-CD11b, and anti-CD5 Abs in FACS buffer. The purities of the sorted cells were 90% or higher, and viability was tested by staining for 7-aminoactinomycin (BioLegend) or with the Fixable Viability Dye eFluor780 (eBioscience).

Purified cells were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C with or without 10 μg/ml LPS stimulation for three or five days or with a combination with 10 μg/ml LPS, 50 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate, 2 μM ionomycin, and 2 μM monensin for five h (Sigma‒Aldrich). For the cell proliferation assay, cells were labeled with CellTrace violet dye and incubated for three days with or without stimulation. For adoptive transfer experiments, 0.5–1 × 105 CD93+CD23lowCD21high T1-MZPs, CD24highCD23highCD21high T2-MZPs, or 0.5–1 × 106 CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells were intravenously injected into CD45.1 or Rag1–/– mice.

ELISpot and ELISA

The numbers of IgM Ab-secreting cells were counted using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISpot) assay with the Mouse IgM B cell ELISpot Development Module and ELISpot Blue Color Module (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 96-well multiscreen HTS plates (Merck, Darmstadt. Germany) were coated with 0.1 mg/ml calf thymus DNA (Sigma‒Aldrich) and 0.2 mg/ml mouse CII (Chondrex) overnight at 4 °C and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (MP Biomedical, CA, USA) diluted in PBS at RT for two h. Purified cells were then added to the plates and incubated in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with or without stimuli in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for two or three days. The plates were incubated with biotinylated anti-IgM Ab followed by streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase, and the proteins were developed using 5-bromo-4-chloro-3’ indolylphosphate p-toluidine salt and nitro blue tetrazolium chloride solution. The plates were scanned with an ImmunoSpot analyzer (CTL, shaker heights, OH), and the spots were counted using ImmunoSpot 5.0 software (CTL).

To measure the serum levels of anti-CII Abs, 96-well immunoplates (SPL Life Sciences, Pocheon, Korea) were coated with mouse CII overnight at 4 °C and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (MP Biomedical, CA, USA) diluted in PBS at RT for two h. Diluted serum samples were incubated at RT for two h. The bound Abs were detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse Ig Abs (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) and tetramethylbenzidine substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). After the reaction was stopped with hydrochloride acid (Sigma‒Aldrich), the absorbance of each well was read using a spectrophotometer (450 nm; Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA).

Immunofluorescence staining

DBA/1 CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells were sorted and irradiated in vitro with 2 Gy. Then, the cells were cultured in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 30 min or six h. The cells were washed with PBS and stained with Alexa488-conjugated anti-phospho-H2AX following the intracellular staining protocol. After washing with PBS, the cells were resuspended in PBS and incubated on Poly-L-Lysine-Coated German Glass Cover Slips (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 30 min. Cover slips were wiped and mounted onto slides by using ProLong™ Diamond Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Invitrogen). The slides were completely dried and observed by using an LSM 710 laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Chester, VA, USA). The acquired images were analyzed using NIH ImageJ software with a custom macro function that was designed to count the particles. At least 40 images from 2 Gy-irradiated cells and 20 images from 0 Gy-irradiated cells were analyzed.

Bulk RNA sequencing and data analysis

Bulk RNA sequencing of 1 × 106 CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells that were obtained from pooled splenocytes harvested from three 7- to 8-week-old DBA/1 or C57BL/6 mice was performed at Life is Art of Science Laboratory (Gimpo, Korea); the extracted total RNA was treated with TRIzol® RNA isolation reagents (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA) and processed to prepare the mRNA sequencing library using the Illumina TruSeq Stranded Preparation Kit (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quantification of all the libraries was performed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad). Next, high-throughput sequencing was performed on a NextSeq550 sequencer (Illumina, Inc.) with 150-bp paired-end reads.

STAR software (version 2.5) and Cufflinks (version 2.2.1) were used to align reads to the mouse reference genome mm10 of the UCSC genome (https://genome.ucsc.edu) and to quantify mapped reads, respectively. Gene expression levels were calculated based on fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped (FPKM). DEGs between CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells were analyzed by Cuffdiff software in Cufflinks, with cutoffs of p < 0.05 and |log2-fold change| ≥1 being considered significant. The DEGs were identified using the following software: EnhancedVolcano package in R [75], g:Profiler (https://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler), GSEA (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org; [76]), and Microsoft Excel for the heatmap.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR

Total RNA was extracted from 1 × 106 CD80high and CD80low MZ B cells that were purified from C57BL/6 or DBA/1 mice using TRIzol, chloroform, isopropanol, and 70% ethanol. RNA was resuspended in DEPC water, quantified using a Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and reverse-transcribed to cDNA using a PrimeScriptTM 1st strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara Bio, Siga, Japan). TaqMan-based qRT‒PCR analysis was performed using a TaqMan Gene Expression Assay Kit (Applied Biosystems, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and a QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies, Frederick, MD, USA). Primers for Cd80 (Mm00711660_m1), Jchain (Mm00461780_m1), and Mpeg1 (Mm01222137_g1) were used, and GAPDH (Mm99999915_g1) was used as an internal control.

B cell receptor repertoire and data analysis

Total RNA from 1 × 106 peritoneal B-1a cells and splenic CD80high MZ, CD80low MZ, and FO B cells that were harvested from eight DBA/1 or C57BL/6 mice was amplified to identify clone-specific rearrangements of the Ig heavy chain genes using the Long Read iR-Reagent System (iRepertoire, Huntsville, AL, USA). Extracted RNA was quantified using a 2100 Bioanalyzer RNA Kit with a Bioanalyzer RNA Chip, and the generated libraries were evaluated using a Bioanalyzer DNA 1000 Chip (Agilent). The Illumina MiSeq platform was used to perform 250 bp paired-end sequencing of the pooled libraries.

For repertoire analysis, raw paired-end fastq files were analyzed using iRepertoire’s high-throughput immune repertoire sequence analysis workflow (https://irweb.irepertoire.com/nir/). The data were visualized via Treemaps generated by iRepertoire. Heatmaps were created in Microsoft Excel. Venn diagrams were generated using the Venn Diagram package in R (https://www.r-project.org/). To verify the differences in B cell receptor (BCR) repertoires, Simpson and Shannon indices were calculated for the B cell subpopulations as previously described [77]. A repertoire comparison was performed by calculating the MH similarity index [46]. Shannon and MH indices were calculated for the top 10,000 clonotypes. The formulas for the diversity and comparison indices are as follows:

where D is the Simpson index, H is the Shannon index, CMH (P,Q) is the MH similarity index between populations P and Q, pi is the relative abundance of clonotype i in population P, qi is the relative abundance of clonotype i in population Q, and pi + qi is the relative abundance of clonotype i in a merged population (P + Q).

Somatic mutations of clonotype sequences were evaluated using the IMGT database (https://www.imgt.org/; Montpellier, France).

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of differences between groups was assessed using unpaired or paired Student’s t tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA); p values ≤ 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to perform the statistical analyses and generate the graphs.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (2023R1A2C2004510); Korea Basic Science Institute (National Research Facilities and Equipment Center) grant (2020R1A6C101A191) of the Ministry of Education (Korea); and the BK21 FOUR Program (Graduate School Innovation) of Sungkyunkwan University.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: SL, SJI, TJK. Methodology, validation, and analysis: SL, HWL, DA, WJO, HGH; Data curation: SL, DA, YK, HWL; BCR sequencing and RNA-seq data analysis: SL, DA, HWL, WJO, HGH; Writing – original draft: SL, TJK; Writing – review, editing: SL, SJI, TJK.

Data availability

The raw BCR sequencing and gene expression data were deposited in the NCBI database under accession number PRJNA938995.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Se Jin Im, Email: sejinim@skku.edu.

Tae Jin Kim, Email: tjkim@skku.edu.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41423-024-01126-0.

References

- 1.Allman D, Pillai S. Peripheral B cell subsets. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:149–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Somers V, Dunn-Walters DK, van der Burg M, Fraussen J. Editorial: new insights into B cell subsets in health and disease. Front Immunol. 2022;13:854889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garraud O, Borhis G, Badr G, Degrelle S, Pozzetto B, Cognasse F, et al. Revisiting the B-cell compartment in mouse and humans: more than one B-cell subset exists in the marginal zone and beyond. BMC Immunol. 2012;13:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Revilla IDR, Bilic I, Vilagos B, Tagoh H, Ebert A, Tamir IM, et al. The B-cell identity factor Pax5 regulates distinct transcriptional programmes in early and late B lymphopoiesis. EMBO J. 2012;31:3130–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King JK, Ung NM, Paing MH, Contreras JR, Alberti MO, Fernando TR, et al. Regulation of marginal zone B-cell differentiation by MicroRNA-146a. Front Immunol. 2016;7:670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas KM. B-1 lymphocytes in mice and nonhuman primates. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1362:98–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zouali M, Richard Y. Marginal zone B-cells, a gatekeeper of innate immunity. Front Immunol. 2011;2:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin F, Kearney JF. Marginal-zone B cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:323–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cerutti A, Cols M, Puga I. Marginal zone B cells: virtues of innate-like antibody-producing lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:118–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palm AE, Kleinau S. Marginal zone B cells: from housekeeping function to autoimmunity? J Autoimmun. 2021;119:102627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cinamon G, Zachariah MA, Lam OM, Foss FW Jr., Cyster JG. Follicular shuttling of marginal zone B cells facilitates antigen transport. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:54–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnon TI, Horton RM, Grigorova IL, Cyster JG. Visualization of splenic marginal zone B-cell shuttling and follicular B-cell egress. Nature. 2013;493:684–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Attanavanich K, Kearney JF. Marginal zone, but not follicular B cells, are potent activators of naive CD4 T cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:803–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang JH, Wu Q, Yang P, Li H, Li J, Mountz JD. et al. Type I interferon-dependent CD86(high) marginal zone precursor B cells are potent T cell costimulators in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:1054–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferguson AR, Youd ME, Corley RB. Marginal zone B cells transport and deposit IgM-containing immune complexes onto follicular dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2004;16:1411–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cariappa A, Tang M, Parng C, Nebelitskiy E, Carroll M, Georgopoulos K, et al. The follicular versus marginal zone B lymphocyte cell fate decision is regulated by Aiolos, Btk, and CD21. Immunity. 2001;14:603–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pillai S, Cariappa A. The follicular versus marginal zone B lymphocyte cell fate decision. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:767–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin F, Chen X, Kearney JF. Development of VH81X transgene-bearing B cells in fetus and adult: sites for expansion and deletion in conventional and CD5/B1 cells. Int Immunol. 1997;9:493–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park C, Kho IS, In Yang J, Kim MJ, Park S, Cha HS, et al. Positive selection of type II collagen-reactive CD80(high) marginal zone B cells in DBA/1 mice. Clin Immunol. 2017;178:64–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Li H, Weigert M. Autoreactive B cells in the marginal zone that express dual receptors. J Exp Med. 2002;195:181–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kishi Y, Higuchi T, Phoon S, Sakamaki Y, Kamiya K, Riemekasten G, et al. Apoptotic marginal zone deletion of anti-Sm/ribonucleoprotein B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:7811–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carey JB, Moffatt-Blue CS, Watson LC, Gavin AL, Feeney AJ. Repertoire-based selection into the marginal zone compartment during B cell development. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2043–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palm AK, Friedrich HC, Mezger A, Salomonsson M, Myers LK, Kleinau S. Function and regulation of self-reactive marginal zone B cells in autoimmune arthritis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2015;12:493–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marino E, Batten M, Groom J, Walters S, Liuwantara D, Mackay F, et al. Marginal-zone B-cells of nonobese diabetic mice expand with diabetes onset, invade the pancreatic lymph nodes, and present autoantigen to diabetogenic T-cells. Diabetes. 2008;57:395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lechner M, Engleitner T, Babushku T, Schmidt-Supprian M, Rad R, Strobl LJ, et al. Notch2-mediated plasticity between marginal zone and follicular B cells. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lenschow DJ, Sperling AI, Cooke MP, Freeman G, Rhee L, Decker DC, et al. Differential up-regulation of the B7-1 and B7-2 costimulatory molecules after Ig receptor engagement by antigen. J Immunol. 1994;153:1990–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuseff MI, Reversat A, Lankar D, Diaz J, Fanget I, Pierobon P, et al. Polarized secretion of lysosomes at the B cell synapse couples antigen extraction to processing and presentation. Immunity. 2011;35:361–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodnow CC, Crosbie J, Adelstein S, Lavoie TB, Smith-Gill SJ, Brink RA, et al. Altered immunoglobulin expression and functional silencing of self-reactive B lymphocytes in transgenic mice. Nature. 1988;334:676–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duong BH, Tian H, Ota T, Completo G, Han S, Vela JL, et al. Decoration of T-independent antigen with ligands for CD22 and Siglec-G can suppress immunity and induce B cell tolerance in vivo. J Exp Med. 2010;207:173–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kinnunen T, Chamberlain N, Morbach H, Choi J, Kim S, Craft J, et al. Accumulation of peripheral autoreactive B cells in the absence of functional human regulatory T cells. Blood. 2013;121:1595–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freeman GJ, Borriello F, Hodes RJ, Reiser H, Hathcock KS, Laszlo G, et al. Uncovering of functional alternative CTLA-4 counter-receptor in B7-deficient mice. Science. 1993;262:907–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carnrot C, Prokopec KE, Rasbo K, Karlsson MC, Kleinau S. Marginal zone B cells are naturally reactive to collagen type II and are involved in the initiation of the immune response in collagen-induced arthritis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2011;8:296–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Won WJ, Kearney JF. CD9 is a unique marker for marginal zone B cells, B1 cells, and plasma cells in mice. J Immunol. 2002;168:5605–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubtsov AV, Swanson CL, Troy S, Strauch P, Pelanda R, Torres RM. TLR agonists promote marginal zone B cell activation and facilitate T-dependent IgM responses. J Immunol. 2008;180:3882–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin F, Oliver AM, Kearney JF. Marginal zone and B1 B cells unite in the early response against T-independent blood-borne particulate antigens. Immunity. 2001;14:617–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meyer-Bahlburg A, Bandaranayake AD, Andrews SF, Rawlings DJ. Reduced c-myc expression levels limit follicular mature B cell cycling in response to TLR signals. J Immunol. 2009;182:4065–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dominguez-Villar M, Hafler DA. Regulatory T cells in autoimmune disease. Nat Immunol. 2018;19:665–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ray A, Dittel BN. Mechanisms of regulatory B cell function in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases beyond IL-10. J Clin Med. 2017;6:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kieback E, Hilgenberg E, Stervbo U, Lampropoulou V, Shen P, Bunse M, et al. Thymus-derived regulatory T cells are positively selected on natural self-antigen through cognate interactions of high functional avidity. Immunity. 2016;44:1114–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maseda D, Smith SH, DiLillo DJ, Bryant JM, Candando KM, Weaver CT, et al. Regulatory B10 cells differentiate into antibody-secreting cells after transient IL-10 production in vivo. J Immunol. 2012;188:1036–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun J, Wang J, Pefanis E, Chao J, Rothschild G, Tachibana I, et al. Transcriptomics identify CD9 as a marker of murine IL-10-competent regulatory B cells. Cell Rep. 2015;13:1110–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riggs JE, Lussier A, Lee S, Appel M, Woodland R. Differential radiosensitivity among B cell subpopulations. J Immunol. 1988;141:1799–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taneja N, Davis M, Choy JS, Beckett MA, Singh R, Kron SJ, et al. Histone H2AX phosphorylation as a predictor of radiosensitivity and target for radiotherapy. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2273–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dubois F, Limou S, Chesneau M, Degauque N, Brouard S, Danger R. Transcriptional meta-analysis of regulatory B cells. Eur J Immunol. 2020;50:1757–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kassambara A, Reme T, Jourdan M, Fest T, Hose D, Tarte K, et al. GenomicScape: an easy-to-use web tool for gene expression data analysis. Application to investigate the molecular events in the differentiation of B cells into plasma cells. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11:e1004077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Venturi V, Kedzierska K, Tanaka MM, Turner SJ, Doherty PC, Davenport MP. Method for assessing the similarity between subsets of the T cell receptor repertoire. J Immunol Methods. 2008;329:67–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kin NW, Crawford DM, Liu J, Behrens TW, Kearney JF. DNA microarray gene expression profile of marginal zone versus follicular B cells and idiotype positive marginal zone B cells before and after immunization with Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Immunol. 2008;180:6663–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cariappa A, Boboila C, Moran ST, Liu H, Shi HN, Pillai S. The recirculating B cell pool contains two functionally distinct, long-lived, posttransitional, follicular B cell populations. J Immunol. 2007;179:2270–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song H, Cerny J. Functional heterogeneity of marginal zone B cells revealed by their ability to generate both early antibody-forming cells and germinal centers with hypermutation and memory in response to a T-dependent antigen. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1923–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Radice E, Ameti R, Melgrati S, Foglierini M, Antonello P, Stahl RAK, et al. Marginal zone formation requires ACKR3 expression on B cells. Cell Rep. 2020;32:107951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grimaldi CM, Michael DJ, Diamond B. Cutting edge: expansion and activation of a population of autoreactive marginal zone B cells in a model of estrogen-induced lupus. J Immunol. 2001;167:1886–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mandik-Nayak L, Racz J, Sleckman BP, Allen PM. Autoreactive marginal zone B cells are spontaneously activated but lymph node B cells require T cell help. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1985–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gies V, Bouis D, Martin M, Pasquali JL, Martin T, Korganow AS, et al. Phenotyping of autoreactive B cells with labeled nucleosomes in 56R transgenic mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7:13232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kanayama N, Cascalho M, Ohmori H. Analysis of marginal zone B cell development in the mouse with limited B cell diversity: role of the antigen receptor signals in the recruitment of B cells to the marginal zone. J Immunol. 2005;174:1438–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Julien S, Soulas P, Garaud JC, Martin T, Pasquali JL. B cell positive selection by soluble self-antigen. J Immunol. 2002;169:4198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Makowska A, Faizunnessa NN, Anderson P, Midtvedt T, Cardell S. CD1high B cells: a population of mixed origin. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:3285–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ichikawa D, Asano M, Shinton SA, Brill-Dashoff J, Formica AM, Velcich A, et al. Natural anti-intestinal goblet cell autoantibody production from marginal zone B cells. J Immunol. 2015;194:606–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scharer CD, Barwick BG, Guo M, Bally APR, Boss JM. Plasma cell differentiation is controlled by multiple cell division-coupled epigenetic programs. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gaudette BT, Roman CJ, Ochoa TA, Gomez Atria D, Jones DD, Siebel CW, et al. Resting innate-like B cells leverage sustained Notch2/mTORC1 signaling to achieve rapid and mitosis-independent plasma cell differentiation. J Clin Invest. 2021;131:e151975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen TT, Tsai MH, Kung JT, Lin KI, Decker T, Lee CK. STAT1 regulates marginal zone B cell differentiation in response to inflammation and infection with blood-borne bacteria. J Exp Med. 2016;213:3025–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Collins AV, Brodie DW, Gilbert RJ, Iaboni A, Manso-Sancho R, Walse B, et al. The interaction properties of costimulatory molecules revisited. Immunity. 2002;17:201–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pentcheva-Hoang T, Egen JG, Wojnoonski K, Allison JP. B7-1 and B7-2 selectively recruit CTLA-4 and CD28 to the immunological synapse. Immunity. 2004;21:401–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hathcock KS, Laszlo G, Pucillo C, Linsley P, Hodes RJ. Comparative analysis of B7-1 and B7-2 costimulatory ligands: expression and function. J Exp Med. 1994;180:631–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sansom DM, Manzotti CN, Zheng Y. What’s the difference between CD80 and CD86? Trends Immunol. 2003;24:314–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Anderson SM, Tomayko MM, Ahuja A, Haberman AM, Shlomchik MJ. New markers for murine memory B cells that define mutated and unmutated subsets. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2103–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bar-Or A, Oliveira EM, Anderson DE, Krieger JI, Duddy M, O’Connor KC, et al. Immunological memory: contribution of memory B cells expressing costimulatory molecules in the resting state. J Immunol. 2001;167:5669–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yanaba K, Bouaziz JD, Haas KM, Poe JC, Fujimoto M, Tedder TF. A regulatory B cell subset with a unique CD1dhiCD5+ phenotype controls T cell-dependent inflammatory responses. Immunity. 2008;28:639–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nibbs RJ, Wylie SM, Pragnell IB, Graham GJ. Cloning and characterization of a novel murine beta chemokine receptor, D6. Comparison to three other related macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha receptors, CCR-1, CCR-3, and CCR-5. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12495–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nibbs RJ, Graham GJ. Immune regulation by atypical chemokine receptors. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:815–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee S, Ko Y, Kim TJ. Homeostasis and regulation of autoreactive B cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17:561–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reyes-Ruiz A, Dimitrov JD. How can polyreactive antibodies conquer rapidly evolving viruses? Trends Immunol. 2021;42:654–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]