Abstract

The actin cytoskeleton and reactive oxygen species (ROS) both play crucial roles in various cellular processes. Previous research indicated a direct interaction between two key components of these systems: the WAVE1 subunit of the WAVE regulatory complex (WRC), which promotes actin polymerization and the p47phox subunit of the NADPH oxidase 2 complex (NOX2), which produces ROS. Here, using carefully characterized recombinant proteins, we find that activated p47phox uses its dual Src homology 3 domains to bind to multiple regions within the WAVE1 and Abi2 subunits of the WRC, without altering WRC’s activity in promoting Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization. Notably, contrary to previous findings, p47phox uses the same binding pocket to interact with both the WRC and the p22phox subunit of NOX2, albeit in a mutually exclusive manner. This observation suggests that when activated, p47phox may separately participate in two distinct processes: assembling into NOX2 to promote ROS production and engaging with WRC to regulate the actin cytoskeleton.

Keywords: p47phox, NADPH oxidase, NOX2, WAVE complex, WRC, ROS, Arp2/3, actin cytoskeleton

The dynamic assembly of the actin cytoskeleton and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) are prominently localized at membrane ruffles in actively migrating cells. The intricate interplay between these two processes is essential for a variety of biological processes, including cell adhesion, migration, phagocytosis, and tissue morphogenesis (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). Although extensive studies have focused on oxidative modifications of actin and various regulators of actin, including the Rho-family GTPases, the Src kinases, cofilin, myosin, gelsolin, L-plastin, and calmodulin (7, 9, 10, 11, 12), the direct coordination between ROS-generating enzymes and actin regulators has remained elusive.

In 2003, Terada’s group made a seminal observation of a direct interaction between two key regulators of these systems: the WAVE regulatory complex (WRC), which promotes actin polymerization, and the NADPH oxidase 2 complex (NOX2), which is responsible for generating ROS (13). The interaction was found to promote actin polymerization and membrane ruffling in vascular endothelial growth factor-stimulated endothelial cells (13) and play a potential role in directing the invasive migration of melanoma cells (14).

WRC is a central actin nucleation-promoting factor in the plasma membrane (15). It comprises five conserved proteins: Sra1, Nap1, Abi2, HSPC300, and the Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome family protein WAVE1 (or their corresponding mammalian orthologs in a mix-and-match arrangement). In its basal state, WRC resides in the cytosol, where it keeps WAVE1 inhibited through intramolecular interactions. WRC's activity at membranes is finely modulated through interactions with numerous membrane ligands, including inositol phospholipids, various membrane receptors bearing WRC-interacting receptor sequences, small G proteins such as Rac1 and Arf1, and various scaffolding proteins (15, 16). Activation of WRC involves the binding of Rac1 and/or Arf1 at three distinct sites, leading to the release of WAVE1’s C-terminal WH2-central-acidic (WCA) domain, which in turn stimulates Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization and lamellipodia formation in migrating cells (17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23).

NOX2 is a crucial enzyme responsible for generating ROS in various cell types (24, 25, 26, 27). The holoenzyme of NOX2 undergoes dynamic assembly involving three cytosolic proteins (p47phox, p40phox, and p67phox) and three membrane-associated proteins (Rac1 or Rac2, p22phox, and the catalytical core gp91phox) (26, 27, 28, 29). In its resting state, gp91phox remains inactive, while p47phox is autoinhibited in the cytosol (30, 31, 32, 33). The autoinhibition of p47phox is achieved through its C-terminal autoinhibitory region (AIR), which obstructs the p22phox-binding pocket formed between the N-terminal dual Src homology 3 (SH3) domains (31, 32). The assembly and concurrent activation of the NOX2 holoenzyme hinge upon the phosphorylation of the AIR sequence by various kinases (26). Phosphorylation dislodges the AIR sequence from the p22phox-binding pocket, allowing the latter to bind to the proline-rich region (PRR) within the intracellular domain (ICD) of p22phox (31, 34). This orchestrated process is essential for exerting precise spatiotemporal control over NOX2 activation and the subsequent generation of ROS (26, 35).

Terada’s work indicated that the interaction between WRC and NOX2 is mediated by the PRR of WAVE1 binding to individual SH3 domains of p47phox (13). Intriguingly, when a mutation was introduced at the highly conserved residue, W193, within the p22phox-binding pocket, it disrupted the binding to p22phox but did not affect the interaction with WAVE1 (13). These data suggest that the SH3 domains of p47phox use a distinct surface for binding to the PRR of WAVE1, potentially allowing a single p47phox molecule to simultaneously assemble into NOX2 and interact with WRC, forming a large signalosome to coordinate ROS production and actin remodeling (13, 35).

In this study, we used carefully characterized recombinant proteins to rigorously investigate the interaction between p47phox and WRC. Surprisingly, we found that the dual SH3 domains but not individual SH3 domains of p47phox directly interacted with multiple sequences within the fully assembled WRC. Moreover, the interaction did not appear to impact WRC’s activity in stimulating Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization. Remarkably, we found that both WRC and p22phox bound to the same pocket in p47phox but they did so in a mutually exclusive manner. Therefore, our data suggest a distinct model in which activated p47phox may separately participate in two crucial processes: assembling into NOX2 to stimulate ROS production and interacting with WRC to regulate the actin cytoskeleton.

Results

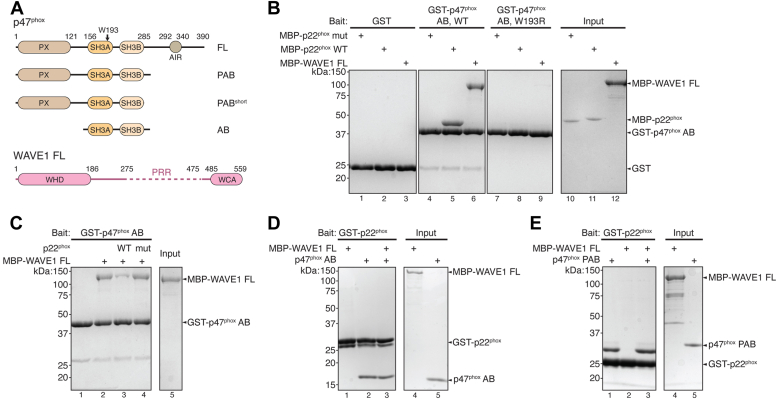

WAVE1 and p22phox share the same binding site on p47phox

Due to challenges in producing recombinant WAVE1, previous studies relied on yeast two-hybrid assays and in vitro translated, unpurified proteins to investigate the interaction between WAVE1 and p47phox (13). To validate the previous results, we purified various fragments of p47phox and the full-length (FL) WAVE1 recombinantly using established protocols (Fig. 1A) (36, 37). Consistent with prior findings, our pull-down assays confirmed a robust interaction between p47phox and both FL WAVE1 and p22phox ICD (referred to as p22phox for brevity hereafter). Specifically, glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-tagged dual SH3 domains of p47phox (hereafter referred to as p47phox AB, Fig. 1A), but not GST, retained both maltose-binding protein (MBP)-tagged FL WAVE1 and MBP-tagged p22phox, while the mutant p22phox, in which the p47phox-binding PRR sequence was replaced with alanines, failed to bind to p47phox AB (Fig. 1B, lanes 1–6). Contrary to previous findings, which suggested that the W193R mutation in the p22phox-binding pocket only disrupted the binding to p22phox but not to WAVE1 (13), it was to our surprise that W193R abolished the binding to both p22phox and FL WAVE1 (Fig. 1B, lanes 7–9). This result indicated that, distinct from the previous conclusions, WAVE1 and p22phox may share the same binding pocket on p47phox.

Figure 1.

p47phoxbinds to full-length WAVE1.A, schematic showing domain organization and constructs used in this study. B–E, Coomassie blue–stained SDS PAGE gels showing glutathione-S-transferaseGST) pull-down between GST-p47phox AB or GST-p22phox and FL WAVE1 in indicated conditions. B, WT and W193R mutant of GST-p47phox AB pulling down MBP-p22phox and MBP-FL WAVE1. C, GST-p47phox AB pulling down FL WAVE1 in the presence of p22phox ICD peptide as competitors. D and E, far pull-down results of FL WAVE1 by GST-p22phox in the presence of untagged p47phox AB in (D) or PAB in (E). ICD, intracellular domain; MBP, maltose-binding protein.

To further investigate the previous model which proposed that WAVE1 and p22phox can simultaneously bind to the same p47phox (13), we used two distinct approaches. First, in a competition pull-down assay, we observed that the WT p22phox ICD peptide, but not the mutant peptide, significantly suppressed the binding to WAVE1 (Fig. 1C). Next, we used a far pull-down assay to test whether untagged p47phox AB could act as a bridge between p22phox and WAVE1, which would support the idea of their simultaneous binding to the same p47phox. However, our experiments failed to detect any interaction between GST-p22phox and FL WAVE1 in the presence of untagged p47phox, whether it is the AB construct or the longer PAB construct (where P stands for the phox-homology or PX domain) (Fig. 1, A, D, and E). Together, our data strongly indicate that the interactions of both WAVE1 and p22phox with p47phox occur through the same binding pocket and are mutually exclusive.

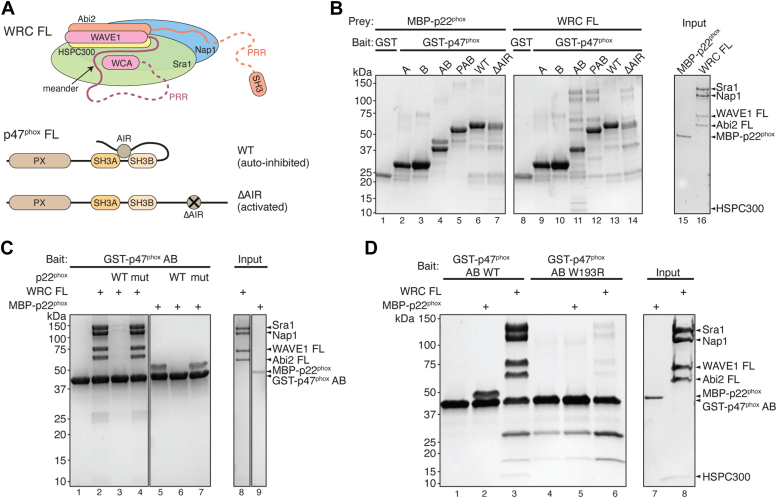

WRC interacts with p47phox at the same binding pocket

Inside the cell, WAVE1 does not exist as a single polypeptide chain but instead is constitutively incorporated into the WRC (Fig. 2A) (15). As a result of the limited availability of WRC purification techniques, earlier studies relied on isolated WAVE1 to explore its interaction with p47phox (13). Over the last 2 decades of efforts to refine WRC purification methods, it has become evident that isolated WAVE1 has a tendency to aggregate, potentially introducing experimental artifacts (15, 36, 38). To investigate whether the interaction between p47phox and FL WAVE1 holds true in the context of the WRC, we used recombinantly purified FL WRC in pull-down assays. Surprisingly, in contrast to previous findings, only tandemly linked dual SH3 domains (i.e., GST-p47phox AB), and not the individual A or B SH3 domains, were able to bind the WRC (Fig. 2B, lanes 9–11). This is similar to p22phox, which also required both SH3 domains but not individual ones for binding (Fig. 2B, lanes 2–4). The N-terminal PX domain slightly weakened the binding to p22phox but did not seem to affect the binding to WRC (Fig. 2B, lanes 5 and 12).

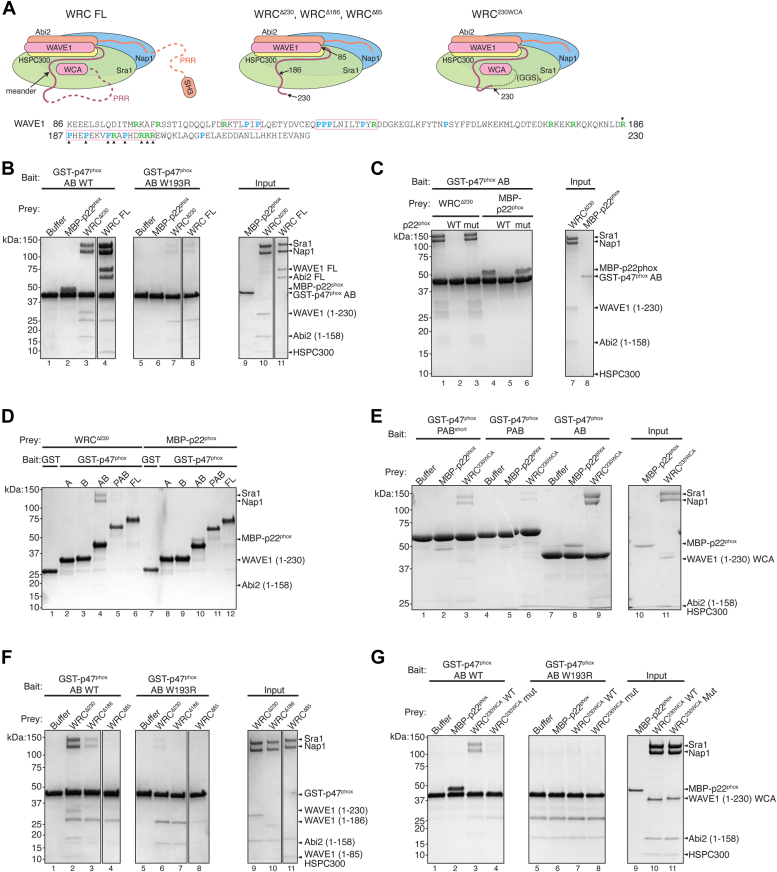

Figure 2.

p47phoxbinds to full-length WRC.A, schematic showing WRC structure and domain organization used in this study. B–D, Coomassie blue–stained SDS-PAGE gels showing glutathione-S-transferase (GST) pull-down results. B, different GST-p47phox truncations pulling down MBP-p22phox and FL WRC. C, GST-p47phox AB pulling down FL WRC in the presence of p22phox ICD peptide as competitors. D, pull-down of FL WRC by WT or mutant GST-p47phox AB. ICD, intracellular domain; MBP, maltose-binding protein; WRC, WAVE regulatory complex.

It is well-established that the FL p47phox protein is autoinhibited due to its AIR sequence binding to the p22phox-binding pocket, which prevents p22phox from binding (Fig. 2A) (31, 32). Consistent with this concept, our experiments showed that the purified FL p47phox did not bind to either WRC or p22phox. In contrast, when we mutated the AIR region to release the autoinhibition, the binding to both WRC and p22phox was restored (Fig. 2B, lanes 6–7, 13–14). Furthermore, the interaction between FL WRC and p47phox was effectively blocked by the addition the WT p22phox peptide, while the mutant peptide had no such effect (Fig. 2C). Moreover, the interaction was abolished by the W193R mutation in the p22phox-binding pocket of p47phox (Fig. 2D). In summary, these data confirm that WRC and p22phox compete for the same pocket in p47phox.

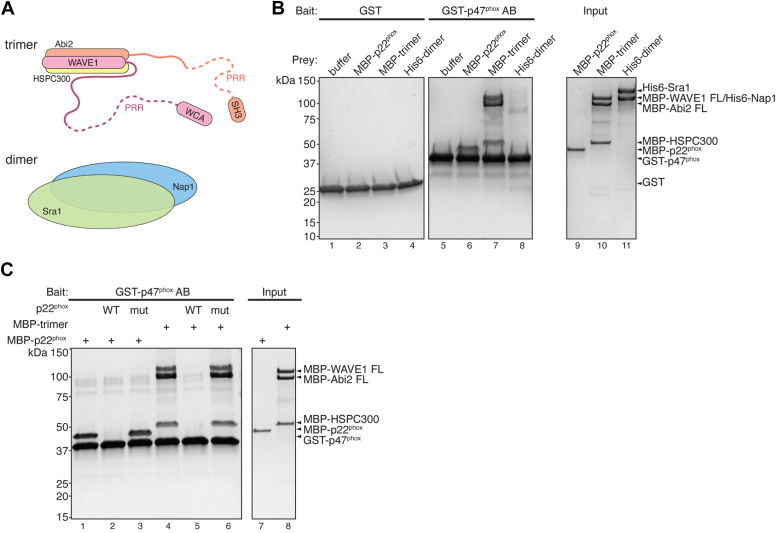

p47phox interacts with the WAVE1–Abi2–HSPC300 subcomplex

To dissect the regions mediating the interaction between FL WRC and p47phox, we tested which subcomplexes of the WRC could bind to GST-p47phox AB. In previous studies, isolated subunits of WRC often encountered issues with protein aggregation, which led to artificial results (15). However, two partially assembled subcomplexes were found to be relatively stable and suitable for biochemical studies, including a dimer containing Sra1 and Nap1, and a trimer containing WAVE1, Abi2, and HSPC300 (Fig. 3A) (36, 38).

Figure 3.

p47phoxbinds to WAVE1–Abi2–HSPC300 subcomplex of WRC.A, schematic showing WRC subcomplexes used in this study. B and C, Coomassie blue–stained SDS-PAGE gels showing glutathione-S-transferase (GST) pull-down results. B, GST-p47phox AB pulling down WRC indicated subcomplexes. C, GST-p47phox AB pulling down trimer in the presence of p22phox ICD peptide as competitors. ICD, intracellular domain; WRC, WAVE regulatory complex.

We found that GST-p47phox AB robustly pulled down an MBP-tagged WAVE1-Abi2-HSPC300 trimer but it did not interact with the Sra1-Nap1 dimer (Fig. 3B). Similar to the interaction between WRC and p47phox, this interaction was effectively blocked by the WT p22phox peptide, but not by the mutant peptide (Fig. 3C). Based on these results, we conclude that the interaction between WRC and p47phox is mediated by the WAVE1-Abi2-HSPC300 portion of the WRC.

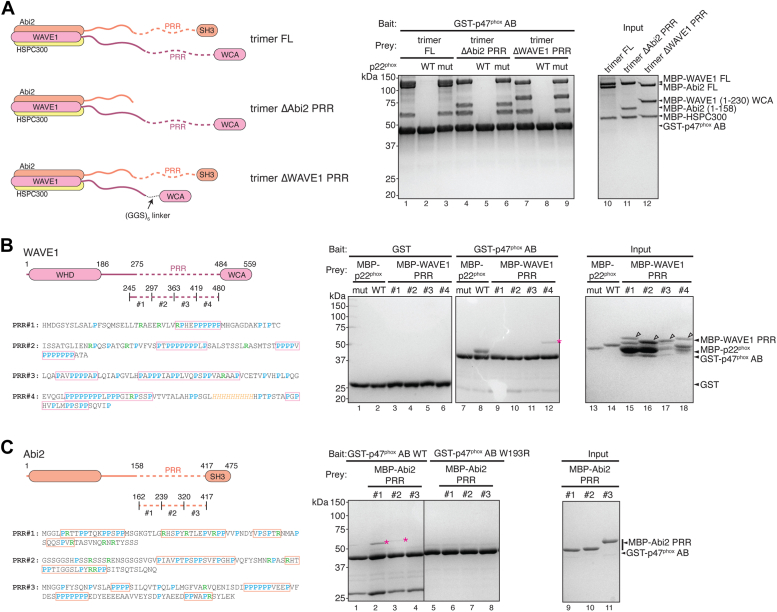

p47phox binds to multiple regions in WAVE1 and Abi2

In the trimer, both WAVE1 and Abi2 possess long unstructured sequences. Unlike their N-terminal helices, these C-terminal unstructured sequences are not involved in assembling the WRC or the WAVE1–Abi2–HSPC300 subcomplex and contain various PRR sequences, which may be important for binding to proteins containing SH3 or EVH1 domains (15, 16, 37, 39). To further identify the regions responsible for binding to p47phox, we generated trimers in which the PRR sequences in either WAVE1 or Abi2 were removed (Fig. 4A). We found that the unstructured regions of either WAVE1 or Abi2 were sufficient to sustain the interaction with p47phox AB, and this interaction could be efficiently blocked by p22phox ICD peptide (Fig. 4B). This result suggests that p47phox AB binds to both WAVE1 and Abi2.

Figure 4.

p47phoxbinds to multiple PRR sequences in WAVE1 and Abi2. Schematic and Coomassie blue–stained SDS-PAGE gels showing glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-p47phox AB pull down of (A) indicated trimers, (B) MBP-tagged PRR fragments of WAVE1, and (C) MBP-tagged PRR fragments of Abi2. In protein sequences, prolines are presented in cyan and arginines in green. PRR sequences are boxed based on proline density and their alignment with predicted SH3-binding sequences (40). Arrowheads in (B) indicate full-length fragments. Magenta asterisks indicate binding signals of corresponding fragments. MBP, maltose-binding protein; PRR, proline-rich region; SH3, Src homology 3.

To narrow down the regions within the unstructured sequences responsible for this interaction, we divided the unstructured regions in WAVE1 and Abi2 into shorter fragments, each of ∼60 residues in length and assessed their individual interactions with p47phox (Fig. 4, B and C). We found that in WAVE1, fragment #4 (residues 419–480) clearly exhibited an interaction with p47phox (Fig. 4B, lane 12, asterisk). This result aligns with previous report, in which WAVE1 (residues 270–442) was found to be important for WAVE1 to bind to p47phox (13). In Abi2, fragment #1 (residues 162–238) and, to a lesser extent, fragment #2 (residues 239–319) displayed interactions with p47phox (Fig. 4C, lanes 2–3, asterisks). Together, we conclude that p47phox can bind to at least three distinct PRR regions in the unstructured sequences of WAVE1 and Abi2. Note that the binding affinity of individual fragments appeared to be weaker than that of the FL proteins. This suggests that other fragments may also contribute to the overall interaction observed in the context of the FL proteins, but their individual affinities were too weak to be detected using pull-down assays. It is not uncommon for the combined contributions of multiple weak-affinity regions to contribute to a strong binding observed with FL proteins, often due to avidity or cooperativity effects.

WAVE1 contains an additional, noncanonical p47phox binding sequence

Based on our above results, we initially predicted that removing the unstructured regions from both WAVE1 and Abi2 would eliminate the binding of the WRC to p47phox. This WRC, referred to as WRCΔ230 in previous structural studies, consists of WAVE1 1 to 230 and Abi2 1 to 158, excluding the unstructured sequences at the C terminus (Fig. 5A) (17, 36). To our surprise, we found that WRCΔ230 still exhibited robust binding to p47phox. Similar to the interactions with p22phox and FL WRC, the binding of WRCΔ230 to p47phox was abolished by the W193R mutation (Fig. 5B) and was competitively disrupted by the p22phox peptide (Fig. 5C). Moreover, this binding relied on the dual SH3 domains in the activated p47phox. Individual SH3 domains or the FL autoinhibited p47phox did not support the interaction (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

p47phoxbinds to noncanonical sequences in WAVE1 86 to 230.A, schematic showing various WRC assemblies. WAVE1 86 to 230 sequences are shown in which prolines are presented in cyan and arginines in green, and PRR sequences are boxed based on proline density and their alignment with predicted noncanonical SH3-binding sequences (40). Arrowheads indicate residues mutated in WAVE1230WCA mutant used in (G). B–F, Coomassie blue–stained SDS-PAGE gels showing glutathione-S-transferase (GST) pull-down results. B, shows GST-p47phox AB pulling down WRCΔ230. C, GST-p47phox AB pulling down WRCΔ230 in the presence of p22phox ICD peptide as competitors. Note that the control lanes 4 to 6 are identical to lanes 5 to 7 in Figure 2C. D, pull-down results of WRCΔ230 by various GST-p47phox constructs. E, pull-down results of WRC230WCA comparing various GST-p47phox constructs. F, shows GST-p47phox AB pulling down indicated WRCs. G, shows GST-p47phox AB pulling down WRC230WCA WT and mutant. ICD, intracellular domain; PRR, proline-rich region; SH3, Src homology 3; WCA, WH2-central-acidic; WRC, WAVE regulatory complex.

Note that the p47phox PAB construct appeared to lose the binding to WRCΔ230 (Fig. 5D, lane 5), although it maintained the binding to FL WRC (Fig. 2B, lane 12). We suspected that either the PX domain at the N terminus of the dual SH3 domains or the additional amino acid linker at the C terminus interfered with the binding to WRCΔ230. To investigate this, we removed the extra amino acids at the C terminus and found that the resulting p47phox PABshort construct (Fig. 1A) exhibited an improved binding to WRCΔ230 (Fig. 5E, lane 3). Note that the binding affinity was still weaker than p47phox AB (Fig. 5E, lane 9), suggesting that the PX domain might pose certain steric clashes with the bound WRC. Due to its higher binding affinity, we switched to p47phox PABshort for experiments described hereafter that involved PAB.

We suspected that the binding between WRCΔ230 and p47phox was mediated by residues 186 to 230 in WAVE1. This region is important for WRC activation but is believed to be a flexible sequence because it remained unresolved in previous X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM studies (17, 20, 22). Consistent with our prediction, the further removal of residues 187 to 230, as in WRCΔ186, substantially reduced the interaction (Fig. 5F, lanes 2–3). Note that WRCΔ186 still exhibited weak residual binding to p47phox, which was abolished by further removal of residues 86 to 186 from WAVE1, as in WRCΔ85 (Fig. 5F, lanes 3–4). Together, these data suggest that, in addition to the PRR sequences in WAVE1 and Abi2, WAVE1 86 to 230 also interacts with p47phox through the same p22phox-binding pocket (Fig. 5F, lanes 6–8).

WAVE1 86 to 230 is not considered as a PRR and does not contain canonical SH3-binding sequences, yet it is scattered with several prolines and arginines, which are often found in SH3-binding motifs (40). To validate the importance of these residues in mediating the interaction, we mutated R186, P187, P190, P194, R195, P197, R200, R201, and R202 in WAVE1Δ230WCA to alanines (Fig. 5A, arrowheads). As a result, the interaction was greatly reduced (Fig. 5G, lanes 3–4), confirming that WAVE1 186 to 230 contains noncanonical SH3-binding sequences capable of binding to p47phox dual SH3 domains. Note that we used WRC230WCA for these experiments, as it contains the WCA domain, allowing us to measure whether this interaction influences WRC activity in the next section.

p47phox binding does not impact WRC activity

WAVE1 86 to 230 harbors the meander sequence known to be critical for WRC autoinhibition and activation (Fig. 5A), whereas the C-terminal unstructured PRR sequences do not contribute to WRC assembly or activation but allow the WRC to interact with various regulatory proteins (15, 16). Given that p47phox dual SH3 domains directly interacted with the WAVE1 86 to 230 sequence, we speculated that this interaction might influence WRC activity. To test this hypothesis, we used the established pyrene-actin polymerization assay to examine the effect of p47phox on WRC activity. Before we conducted this assay, we confirmed that the interaction observed in GST pull-down assays similarly occurred in cogel filtration chromatography (Fig. 6A) and when we swapped bait and prey using MBP-tagged WRC to pull down untagged p47phox PABshort (Fig. 6B, lane 6).

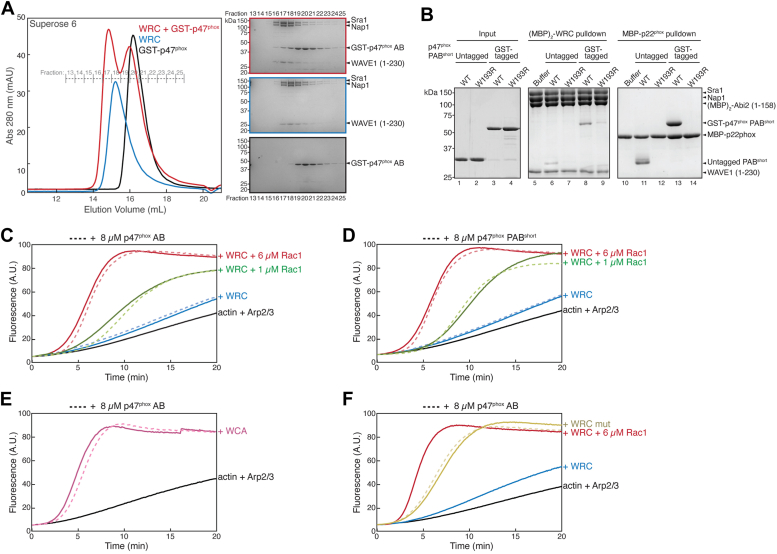

Figure 6.

p47phoxbinding does not impact WRC activity.A, cogel filtration of WRCΔ230 with glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-p47phox AB, showing chromatograms of indicated samples on left and Coomassie blue–stained SDS-PAGE gels on right. Gel images are aligned vertically over indicated fractions. The formation of a WRC–p47phox complex is indicated by the shift of the WRC peak from fraction 18 to 17 and the appearance of p47phox in fractions 16 to 18. B, Coomassie blue–stained SDS-PAGE gels of amylose beads pull down using indicated MBP-tagged baits (41), comparing untagged versus GST-tagged p47phox PABshort. C–F, pyrene-actin polymerization assay at indicated conditions. Reactions contain 3 to 4 μM actin (5% pyrene-labeled), 10 nM Arp2/3, 0.1 μM WRC230WCA or WCA, and indicated Rac1Q61L and/or p47phox. WCA, WH2-central-acidic; WRC, WAVE regulatory complex.

To our surprise, neither p47phox AB (Fig. 6C) nor PABshort (Fig. 6D) had any discernable impact on WRC activity. First, they did not enhance WRC activity in the basal state (without Rac1 activation, blue lines in Fig. 6, C and D). As some WRC ligands, such as WRC-interacting receptor sequence–containing receptors, do not directly enhance WRC activity but can modulate its activity when WRC is activated by Rac1 (22), we tested whether p47phox exhibited a similar behavior. However, p47phox did not alter the activity level of WRC, whether WRC was mildly activated by an intermediate concentration of Rac1 (green lines in Fig. 6, C and D) or fully activated by a saturating concentration of Rac1 (red lines in Fig. 6, C and D).

Certain WRC ligands can have dual and opposing effects in WRC-mediated actin polymerization assays (15). For example, the dendrite branching receptor HPO-30 can promote WRC activation while simultaneously inhibiting actin polymerization, leading to potentially complex outcomes (41). However, we ruled out the possibility that the lack of effect on WRC activity was due to a similar counteracting effect of p47phox based on two observations. First, p47phox did not affect actin polymerization mediated by free WCA peptide, to which p47phox does not bind (Fig. 6E), thus eliminating potential inhibitory effect of p47phox on actin polymerization. Second, p47phox did not affect the activity of a constitutively active WRC in the absence of Rac1, thus eliminating potential complications arising from p47phox affecting Rac1 binding to WRC (Fig. 6F). Together, the data suggest that p47phox binding to WAVE1 86 to 230 sequence does not directly impact WRC activation.

Discussion

The crosstalk between actin remodeling and redox regulation is essential to various cellular processes. A common mechanism underlying this crosstalk involves the oxidation of actin or actin regulators, such as the oxidation of actin filaments by MICAL or various proteins by ROS molecules (9, 10, 11, 12, 42). However, direct interactions between actin regulators and ROS production enzymes have remained elusive. The identification of the interaction between WAVE1 and p47phox 2 decades ago led to an intriguing model, suggesting that activated p47phox could simultaneously bind to p22phox and WAVE1, thereby potentially bridging the WRC and NOX2 into a large signalosome that coordinates actin polymerization and ROS-mediated oxidation (13, 35). In our study, we used well-characterized recombinant materials to elucidate the interaction mechanism and arrived at conclusions that differ from the earlier model.

First, we have established that p22phox and WRC bind to the same pocket in p47phox, and their interactions occur in a mutually exclusive manner, rather than simultaneously. Previous studies suggesting simultaneous binding of WAVE1 and p22phox to p47phox were primarily based on yeast two-hybrid analysis and binding assays using in vitro translated materials (13). These studies indicated that mutating the conserved residue, W193R, within the p22phox-binding pocket did not affect WAVE1 binding. In addition, individual SH3 domains could bind WAVE1. This was distinct from p22phox, which requires both SH3 domains for binding (13). Our studies confirmed a direct interaction between WAVE1 and p47phox and further revealed multiple p47phox binding sequences within the WAVE1 and Abi2 subunits of the WRC.

However, in contrast to previous studies, we find that all interactions between WRC and p47phox, regardless of the specific binding sequences involved, are mediated by the same p22-phox-binding pocket. These interactions share common features with p22phox binding, as they are all abolished by W193R mutation, can be competitively disrupted by p22phox binding, require dual SH3 domains but not individual SH3 domains and cannot occur with autoinhibited FL p47phox. The discrepancy between our findings and prior results likely stems from differences in the materials involved. Over years of effort to establish recombinant WRC purification, it has become evident that individually expressed or purified WRC subunits, including WAVE1, are prone to protein aggregation, which can lead to erroneous experimental outcomes (15). Using our meticulously purified materials and rigorous controls, we have now clarified the previous observations and established that WRC and p22phox bind to p47phox at the same binding site and in a mutually exclusive manner.

WRC contains PRRs known to mediate interactions with various PRR-binding proteins, such as SH3-containing proteins like WRP (43)- and EVH1-containing proteins like Ena/VASP (37, 39). Since the unstructured PRR sequences are not involved in WRC assembly or autoinhibition, these interactions typically do not have a direct impact on WRC activity. Instead, they mainly influence WRC localization and its connections with other signaling pathways. Our study has expanded the list of WRC ligands by establishing p47phox as a genuine WRC-binding protein. This interaction can potentially connect WRC-mediated actin polymerization with pathways involving p47phox, such as NOX2 activation.

In addition to the PRR sequences in WAVE1 and Abi2 that interact with p47phox, we have also uncovered noncanonical SH3-binding sequences within the region spanning residues 86 to 186 of WAVE1. This finding is consistent with the promiscuity of SH3-binding sequences (40, 44) and may prompt reevaluation of other SH3- or EVH1-containing WRC ligands to determine whether they also interact with this specific region. Notably, this region contains the meander sequence, which winds across a conserved surface on Sra1 (Fig. 5A), playing a key role in WRC autoinhibition and activation. Therefore, it is possible that other SH3-containing proteins may dock at this sequence to modulate WRC activity, although, unexpectedly, p47phox binding to this noncanonical sequence did not affect WRC activity under various tested conditions.

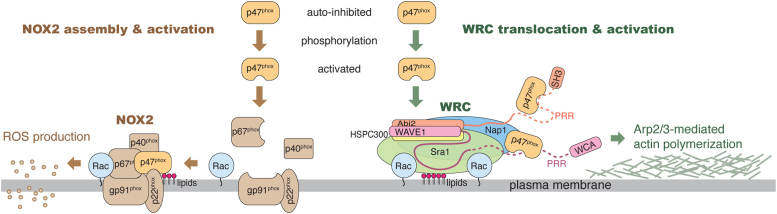

Our results propose a model distinct from previous reports. In this revised model, upon activation, p47phox can participate in two distinct processes in the cell (Fig. 7). In one process, p47phox translocates to the membrane by binding to p22phox and, together with other NOX2 subunits, assembles into an active NOX2 complex to initiate ROS production. In another process, p47phox binds to membrane-associated WRC at multiple sequences. While the precise mechanisms by which the p47phox–WRC interaction modulates actin dynamics in a cellular context remains to be elucidated, several possibilities exist. First, although p47phox binding to WRC does not directly control WRC activity, it could potentially regulate WRC's interactions with other SH3-binding proteins or serve as a scaffold to recruit p47phox-binding ligands. Second, this interaction could influence WRC localization, considering that the PX domain of p47phox interacts with inositol phospholipids at membranes (45, 46), which are also potential activators of the WRC (19, 47). Third, p47phox may interact with actin either directly through its C-terminal sequence (residues 319–337) (48) or indirectly through its PX domain binding to meosin (49, 50). Intriguingly, both inositol phospholipids and Rac1 are shared factors between NOX2 assembly and WRC activation (8). Thus, the cooperative actions of Rac1 activation, inositol phospholipids production, and p47phox activation may play a pivotal role in orchestrating ROS production and actin polymerization (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Schematic depicting an updated model detailing the potential involvement of activated p47phoxin the processes of ROS production and actin cytoskeletal remodeling. This model is based on our interpretation of the biochemical data and warrants further validation through cellular experiments to fully understand its functional implications. ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Taken together, our work clarifies the connection between WRC and p47phox, providing a foundation for exploring the interplay between actin polymerization and ROS production in various cellular processes.

Limitations of the current study

We recognize several limitations in our study, primarily the lack of cellular experiments to elucidate the functional significance of p47phox binding to the WRC within a cellular context. For instance, it remains unknown whether p47phox binding influences WRC activity, localization, or composition inside the cells; whether NOX2 assembly and WRC binding compete for the same pool of activated p47phox; and how the activities of NOX2 and WRC are spatiotemporally linked or balanced through p47phox. We anticipate that our biochemical results, obtained from carefully characterized materials, will pave the way for future investigations into these intriguing questions.

Experimental procedures

Protein purification

Various human WRCs were expressed and purified essentially as previously described (17, 18, 23, 36). All constructs were generated by standard molecular biology procedures and verified by Sanger sequencing. To improve the yield of FL WAVE1 expression from bacterial cells, the coding sequences were synthesized from Integrated DNA Technologies using codons optimized for Escherichia coli expression. The coding sequence of FL human p47phox was obtained from GE Healthcare (IMAGE: 3633829). DNA constructs, protein sequences, and cloning primers used in this study are listed in Tables S1–S3, respectively.

Reconstitution of recombinant WRCs followed previously established protocols involving purification of individual subunits, assembly of subcomplexes (i.e., Sra1/Nap1 dimer and WAVE1/Abi2/HSPC300 trimer), and final purification of the WRC pentamer by a series of affinity, ion exchange, and gel-filtration chromatography steps (23, 36). Sra1 and Nap1 were expressed in Tni cells using the ESF 921 medium (Expression Systems). Other proteins were expressed in BL21 (DE3)T1R cells (Sigma) at 18 °C overnight or ArcticExpress (DE3) RIL cells (Stratagene) at 10 °C for 24 h. Various WRCs used in this study behaved similarly during each step of the reconstitution, showing no sign of misassembly or aggregation.

Different GST-tagged p47phox constructs were purified by Glutathione Sepharose beads (Cytiva), followed by anion-exchange chromatography through a Source Q15 column and gel filtration through a Hiload Superdex 75 column. To obtain untagged p47phox proteins, GST-p47phox was treated with Tev protease overnight at 4 °C to cleave off the GST tag, followed by ion exchange and gel-filtration chromatography to obtain the untagged protein. Proteins including Arp2/3 complex, actin, WAVE1 WCA, TEV protease, HRV 3C protease, and untagged Rac1Q61L were purified as previously described (23, 36). All ion exchange and gel-filtration chromatography steps were performed using columns from Cytiva on an ÄKTA pure protein purification system.

GST pull-down assay

GST pull-down experiments were performed as previously described (17, 23). Typically, 250 to 300 pmol of GST-tagged proteins as baits and 100 to 150 pmol of WRCs as preys were mixed with 20 μl of Glutathione Sepharose beads in 1 ml of binding buffer (10 mM Hepes pH 7, 100 mM NaCl, 5% (w/v) glycerol, 2 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol or 1 mM DTT) at 4 °C for 30 min, followed by three washes using 1 ml of the binding buffer in each time of wash. Bound proteins were eluted with the GST elution buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5, 2 mM MgCl2, and 30 mM reduced GSH) and examined by SDS-PAGE.

Pyrene-actin polymerization assay

Actin polymerization assays were performed as previously described with some modifications here (17, 23). Each reaction (120 μl) contained 3 to 4 μM actin (5% pyrene labeled), 10 nM Arp2/3 complex, 100 nM of WRC230WCA constructs or WAVE1 WCA, and desired concentrations of untagged Rac1Q61L and/or untagged p47phox in the NMEH20GD buffer (50 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM Hepes pH 7, 20% (w/v) glycerol, and 1 mM DTT). Pyrene-actin fluorescence was recorded every 5 s at 22 °C, one reaction per measurement using single-channel pipettes to minimize air bubbles or pipetting errors, using a 96-well flat-bottom black plate (Greiner Bio-One) in a Spark plate reader (Tecan), with excitation at 365 nm and emission at 407 nm (15 nm bandwidth for both wavelengths).

Data availability

All data are contained within the manuscript. Further information and requests for resources and reagents including DNA constructs and recombinant proteins should be directed to Baoyu Chen.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information (17, 22).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

K. J. B. and B. C. conceptualization; K. J. B. and B. C. funding acquisition; B. C. supervision; S. V. N. P. K, B. J. S, K. J. B, and C. A. A. data curation; S. V. N. K. and B. C. writing-original draft; S. V. N. P. K., B. J. S., C. A. A., K. J. B., and B. C. visualization; S. V. N. P., B. J. S., K. J. B., and C. A. A. investigation.

Funding and additional information

The research was supported by the American Heart Association (19IPLOI34660134 [to B. C. and K. J. B.]) and the National Institutes of Health (R35 GM128786 [to B. C.]). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Enrique De La Cruz

Footnotes

Present address for Brodrick J. Sevart: Colorado School of Mines/NREL Advanced Energy Systems Graduate Program, 1500 Illinois Street, Golden, CO 80401, USA.

Supporting information

References

- 1.Gellert M., Hanschmann E.M., Lepka K., Berndt C., Lillig C.H. Redox regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics during differentiation and de-differentiation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2015;1850:1575–1587. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schröder K. NADPH oxidases in redox regulation of cell adhesion and migration. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;20:2043–2058. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurd T.R., DeGennaro M., Lehmann R. Redox regulation of cell migration and adhesion. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tochhawng L., Deng S., Pervaiz S., Yap C.T. Redox regulation of cancer cell migration and invasion. Mitochondrion. 2013;13:246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moldovan L., Moldovan N.I., Sohn R.H., Parikh S.A., Goldschmidt-Clermont P.J. Redox changes of cultured endothelial cells and actin dynamics. Circ. Res. 2000;86:549–557. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.5.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stanley A., Thompson K., Hynes A., Brakebusch C., Quondamatteo F. NADPH oxidase complex-derived reactive oxygen species, the actin cytoskeleton, and Rho GTPases in cell migration. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;20:2026–2042. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu Q., Huff L.P., Fujii M., Griendling K.K. Redox regulation of the actin cytoskeleton and its role in the vascular system. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017;109:84–107. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acevedo A., González-Billault C. Crosstalk between Rac1-mediated actin regulation and ROS production. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018;116:101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson C., Terman J.R., González-Billault C., Ahmed G. Actin filaments-A target for redox regulation. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2016;73:577–595. doi: 10.1002/cm.21315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griesser E., Vemula V., Mónico A., Pérez-Sala D., Fedorova M. Dynamic posttranslational modifications of cytoskeletal proteins unveil hot spots under nitroxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2021;44 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.102014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rouyère C., Serrano T., Frémont S., Echard A. Oxidation and reduction of actin: origin, impact in vitro and functional consequences in vivo. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2022;101 doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2022.151249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balta E., Kramer J., Samstag Y. Redox regulation of the actin cytoskeleton in cell migration and adhesion: on the way to a spatiotemporal view. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.618261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu R.F., Gu Y., Xu Y.C., Nwariaku F.E., Terada L.S. Vascular endothelial growth factor causes translocation of p47phoxto membrane ruffles through WAVE1. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:36830–36840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302251200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park S.J., Kim Y.T., Jeon Y.J. Antioxidant dieckol downregulates the Rac1/ROS signaling pathway and inhibits Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP)-family verprolin-homologous protein 2 (WAVE2)-mediated invasive migration of B16 mouse melanoma cells. Mol. Cells. 2012;33:363–369. doi: 10.1007/s10059-012-2285-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rottner K., Stradal T.E.B., Chen B. WAVE regulatory complex. Curr. Biol. 2021;31:R512–R517. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.01.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramer D.A., Piper H.K., Chen B. WASP family proteins: molecular mechanisms and implications in human disease. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2022;101 doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2022.151244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding B., Yang S., Schaks M., Liu Y., Brown A.J., Rottner K., et al. Structures reveal a key mechanism of WAVE regulatory complex activation by Rac1 GTPase. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:5444. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-33174-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang S., Tang Y., Liu Y., Brown A.J., Schaks M., Ding B., et al. Arf GTPase activates the WAVE regulatory complex through a distinct binding site. Sci. Adv. 2022;8 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.add1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lebensohn A.M., Kirschner M.W. Activation of the WAVE complex by coincident signals controls actin assembly. Mol. Cell. 2009;36:512. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Z., Borek D., Padrick S.B., Gomez T.S., Metlagel Z., Ismail A.M., et al. Structure and control of the actin regulatory WAVE complex. Nature. 2010;468:533–538. doi: 10.1038/nature09623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koronakis V., Hume P.J., Humphreys D., Liu T., Hørning O., Jensen O.N., et al. WAVE regulatory complex activation by cooperating GTPases Arf and Rac1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:14449–14454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107666108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen B., Brinkmann K., Chen Z., Pak C.W., Liao Y., Shi S., et al. The WAVE regulatory complex links diverse receptors to the actin cytoskeleton. Cell. 2014;156:195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen B., Chou H.-T.T., Brautigam C.A., Xing W., Yang S., Henry L., et al. Rac1 GTPase activates the WAVE regulatory complex through two distinct binding sites. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.29795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brandes R.P., Kreuzer J. Vascular NADPH oxidases: molecular mechanisms of activation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2005;65:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lassègue B., San Martín A., Griendling K.K. Biochemistry, physiology, and pathophysiology of NADPH oxidases in the cardiovascular system. Circ. Res. 2012;110:1364–1390. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Benna J., Dang P.M.C., Gougerot-Pocidalo M.A., Marie J.C., Braut-Boucher F. p47phox, the phagocyte NADPH oxidase/NOX2 organizer: structure, phosphorylation and implication in diseases. Exp. Mol. Med. 2009;41:217–225. doi: 10.3858/emm.2009.41.4.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bedard K., Krause K.-H. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2007;87:245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magnani F., Mattevi A. Structure and mechanisms of ROS generation by NADPH oxidases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2019;59:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nocella C., D’Amico A., Cammisotto V., Bartimoccia S., Castellani V., Loffredo L., et al. Structure, activation, and regulation of NOX2: at the crossroad between the innate immunity and oxidative stress-mediated pathologies. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023;12:429. doi: 10.3390/antiox12020429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu R., Song K., Wu J.X., Geng X.P., Zheng L., Gao X., et al. Structure of human phagocyte NADPH oxidase in the resting state. Elife. 2022;11 doi: 10.7554/eLife.83743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groemping Y., Lapouge K., Smerdon S.J., Rittinger K. Molecular basis of phosphorylation-induced activation of the NADPH oxidase. Cell. 2003;113:343–355. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00314-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuzawa S., Suzuki N.N., Fujioka Y., Ogura K., Sumimoto H., Inagaki F. A molecular mechanism for autoinhibition of the tandem SH3 domains of p47phox, the regulatory subunit of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Genes Cells. 2004;9:443–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noreng S., Ota N., Sun Y., Ho H., Johnson M., Arthur C.P., et al. Structure of the core human NADPH oxidase NOX2. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:6079. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-33711-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogura K., Nobuhisa I., Yuzawa S., Takeya R., Torikai S., Saikawa K., et al. NMR solution structure of the tandem Src homology 3 domains of p47 phox complexed with a p22phox-derived proline-rich peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:3660–3668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505193200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ushio-Fukai M. Localizing NADPH oxidase-derived ROS. Sci. STKE. 2006;2006 doi: 10.1126/stke.3492006re8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen B., Padrick S.B., Henry L., Rosen M.K. Biochemical reconstitution of the WAVE regulatory complex. Methods Enzymol. 2014;540:55–72. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397924-7.00004-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen X.J., Squarr A.J., Stephan R., Chen B., Higgins T.E., Barry D.J., et al. Ena/VASP proteins cooperate with the WAVE complex to regulate the actin cytoskeleton. Dev. Cell. 2014;30:569–584. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ismail A.M., Padrick S.B., Chen B., Umetani J., Rosen M.K. The WAVE regulatory complex is inhibited. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:561–563. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi R., Kramer D.A., Chen B., Shen K. A two-step actin polymerization mechanism drives dendrite branching. Neural Dev. 2021;16:3. doi: 10.1186/s13064-021-00154-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teyra J., Huang H., Jain S., Guan X., Dong A., Liu Y., et al. Comprehensive analysis of the human SH3 domain family reveals a wide variety of non-canonical specificities. Structure. 2017;25:1598–1610.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kramer D.A., Narvaez-Ortiz H.Y., Patel U., Shi R., Shen K., Nolen B.J., et al. The intrinsically disordered cytoplasmic tail of a dendrite branching receptor uses two distinct mechanisms to regulate the actin cytoskeleton. Elife. 2023;12 doi: 10.7554/eLife.88492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rajan S., Terman J.R., Reisler E. MICAL-mediated oxidation of actin and its effects on cytoskeletal and cellular dynamics. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023;11 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2023.1124202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soderling S.H., Binns K.L., Wayman G.A., Davee S.M., Ong S.H., Pawson T., et al. The WRP component of the WAVE-1 complex attenuates Rac-mediated signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:970–975. doi: 10.1038/ncb886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saksela K., Permi P. SH3 domain ligand binding: what’s the consensus and where’s the specificity? FEBS Lett. 2012;586:2609–2614. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanai F., Liu H., Field S.J., Akbary H., Matsuo T., Brown G.E., et al. The PX domains of p47phox and p40phox bind to lipid products of PI(3)K. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:675–678. doi: 10.1038/35083070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karathanassis D., Stahelin R.V., Bravo J., Perisic O., Pacold C.M., Cho W., et al. Binding of the PX domain of p47(phox) to phosphatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate and phosphatidic acid is masked by an intramolecular interaction. EMBO J. 2002;21:5057–5068. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oikawa T., Yamaguchi H., Itoh T., Kato M., Ijuin T., Yamazaki D., et al. PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 binding is necessary for WAVE2-induced formation of lamellipodia. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:420–426. doi: 10.1038/ncb1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamura M., Itoh K., Akita H., Takano K., Oku S. Identification of an actin-binding site in p47phox an organizer protein of NADPH oxidase. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhan Y., He D., Newburger P.E., Zhou G.W. p47phox PX domain of NADPH oxidase targets cell membrane via moesin-mediated association with the actin cytoskeleton. J. Cell Biochem. 2004;92:795–809. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wientjes F.B., Reeves E.P., Soskic V., Furthmayr H., Segal A.W. The NADPH oxidase components p47(phox) and p40(phox) bind to moesin through their PX domain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;289:382–388. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the manuscript. Further information and requests for resources and reagents including DNA constructs and recombinant proteins should be directed to Baoyu Chen.