Graphical abstract

Keywords: Ultrasound, Cavitation measurement, Engineering, Food processing, Scale up strategies

Highlights

-

•

Main principles and methods for measuring acoustic cavitation are discussed.

-

•

Acoustic wave and system parameters affecting US process efficiency are discussed.

-

•

US for agri-food applications improved product quality and extraction efficiency.

-

•

US can be combined with conventional agri-food processes to improve operations.

-

•

Innovative designs for large-scale US assisted food processing are described.

Abstract

Acoustic cavitation, an intriguing phenomenon resulting from the interaction of sound waves with a liquid medium, has emerged as a promising avenue in agri-food processing, offering opportunities to enhance established processes improving primary production of ingredients and further food processing. This comprehensive review provides an in-depth analysis of the mechanisms, design considerations, challenges and scale-up strategies associated with acoustic cavitation for agri-food applications. The paper starts by elucidating the fundamental principles of acoustic cavitation and its measurement, delving then into the diverse effects of different parameters associated with, the acoustic wave, mechanical design and operation of the ultrasonic system, along with those related to the food matrix. The technological advancements achieved in the design and set-up of ultrasonic reactors addressing limitations during scale up are also discussed. The design, engineering and mathematical modelling of ultrasonic equipment tailored for agri-food applications are explored, along with strategies to maximize cavitation intensity and efficiency in the application of brining, freezing, drying, emulsification, filtration and extraction. Advanced US equipment, such as multi-transducers (tubular resonator, FLOW:WAVE®) and larger processing surface areas through innovative designing (Barbell horn, CascatrodesTM), are one of the most promising strategies to ensure consistency of US operations at industrial scale. This review paper aims to provide valuable insights into harnessing acoustic cavitation's potential for up-scaling applications in food processing via critical examination of current research and advancements, while identifying future directions and opportunities for further research and innovation.

1. Introduction

Acoustic cavitation is a phenomenon generated when ultrasound (US) waves pass through a liquid medium creating cavities/bubbles that grow, expand and ultimately collapse in microseconds [85], [148], releasing huge amount of energy locally that ultimately contributes to increase the temperature and pressure and to the occurrence of local turbulence and intense liquid circulation in the reactor. The cavitation generated due to the passage of US in the frequency range of 16 kHz–2 MHz (beyond the audible frequency limit) is known as acoustic cavitation and the chemical changes induced are referred to as sonochemistry.

US is a promising technology for the food processing industries due to the effects of intense cavitation caused by high intensity acoustic fields on the chemical, biochemical and mechanical properties of food matrix especially in liquid medium. Due to this, the food processing industries have been applying US in large scale operations since 1990′s [6], being extensively studied for multiple processes including mixing, freezing, thawing, homogenization, brining, filtration, enzyme and microbial inactivation, emulsification, stabilization, preservation, sterilization of equipment, dispersion, hydrogenation, fermentation, particle size reduction, tenderization of meat, drying, ripening, ageing, oxidation, dissolution and crystallization, extraction, degassing and atomization of food [18], [37]. US assisted processes offers several advantages, as it is non-destructive in nature, it is able to reduce energy and chemical inputs in the processes (green technology), and to improve several aspects of foods, including their quality and safety by inactivating microbes and undesirable enzymes, as well as minimizing the negative impact of the technological processing on the sensory attributes of the final food products. The effectiveness of US processing depends on the frequency, power, temperature, transducer selection, signal types, reactor geometry, and physiochemical properties of liquids and food products being treated. Moreover, there are numerous problems associated with scale up due to the attenuation of acoustic cavitation (cushioning effect caused by the static liquid and the bubble cloud), decrease in US intensity at increased distance from the transducers, and hence reducing the performance of the US systemsGogate et al. [40], Gogate et al. [44], [120]. Thus, it is crucial to address the limitations of US systems when aiming to scale-up these processes to improve the performance of the US and allow their expansion to further industrial applications. The operating parameters, equipment design and the mechanism by which the US influences and facilitates the myriad food-based applications must be taken into account during the scale-up process.

2. Mechanism and measurement of acoustic cavitation

The behaviour of the small gas bubbles present in the liquids or gas entrapped in colloidal solids can vary during US treatments based on the pressure and extrinsic other conditions [90]. Cavitation bubbles involve the formation of gas or vapor bubbles within a liquid (Fig. 1). When the pressure in a liquid drops below its vapor pressure, the liquid undergoes a phase change and forms vapor or gas bubbles. These bubbles can be filled with vaporized liquid, gas, or a combination of both. The acoustic cavitation phenomena can be classified as transient and stable depending on the operating parameters and composition of the liquid medium. Stable cavities are persistent microbubbles, formed at US intensities within the range of 1–3 W/cm2, which oscillate non-linearly for many cycles until reaching an equilibrium due to acoustic pressure [3]. Transient cavities are violent in nature, generated at higher US intensity (over 10 W/cm2). The microbubbles that reach their maximum size rapidly and collapse in less than one cycle, inducing microstreaming, cavitation nuclei and shockwaves that generate high temperature and pressure [3].

Fig. 1.

Graphic representation of cavitational bubble dynamics during US. Content for the image modified from Wu et al. [138].

These bubbles are generated due to the transformation of the energy input of the US processes into friction, turbulence, waves and cavitation through increased acceleration of the media, creating local differences of heat and pressure [138]. Cavitation can be produced by different modes, namely, ultrasonic (acoustic) transducers, high pressure nozzle, venturi nozzle, or through high velocity rotation. In case of acoustic cavitation, the amplitude of the sound waves reduces as the waves propagate through the liquid medium. The energy loss due to the scattering phenomenon is negligible and absorption of soundwaves leads to change in bulk viscosity and thermal conductivity [29]. The energy requirement of the US processes is dictated by the type of cavitation achieved; hence, it is critical to tailor the collapsing conditions of the microbubbles to increase the desired effects of US, as well as to reduce the energy consumption of the US-assisted processes.

Bubble dynamics analysis and/or measurement of cavitation intensity are critical as they can be used as indicators of the efficiency of the US systems, as well as to determine whether cavitation occurs or not under certain operating conditions [131]. It is vital to elucidate the maximum size attained by the cavity before it collapses, as this will determine the magnitude of the temperature and pressure changes achieved during the cavitation processes [9]. Moreover, the lifetime of the cavity will also determine the impact zone in a reactor. The measurement of cavitation can be performed both theoretically and experimentally. Theoretical methods include the use of multiple equations, such as the wave and bubble dynamics equations that can be used to estimate the cavitation intensity [9], [43], [94], [100]. The experimental measurements focus on the determination of both the primary and secondary effects of acoustic cavitation. Primary effects of acoustic cavitation include pressure and temperature measurements determined using hydrophones and thermocouples, respectively. The secondary effects include measurements of the formation of radicals, oxidation reactions, electrochemical effects and mass transfer coefficients that can be estimated by multiple physical and chemical methods [12], [62], [68], [71], [120]. The main methods currently available for the measurement of primary and secondary effects of acoustic cavitation together with the main limitations of each method are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Summary of main types, applications and limitations of method for the estimation of the primary and secondary effects of acoustic cavitation.

| Types of effect | Measurement [units] | Description of the methods | Highlights of the methods | Limitations of the methods | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary effects | Pressure [Pa] | Pressure intensity in the liquid medium is quantified using hydrophones. This includes piezoelectric hydrophones (needle device, membrane device, liquid electrode hydrophone and reflector-type hydrophone), thermal probes and optical fibre-tip sensors. |

|

|

Campos-Pozuelo et al. [12],Kanthale, Gogate, Pandit, and Wilhelm [62],Koch and Jenderka [68] |

| Temperature [℃] | Local temperature changes in the liquid medium are measured using thermocouple or thermistor at any position in the reactor. |

|

|

Kuijpers et al. [71],Sutkar and Gogate [120] | |

| Secondary effects | Weissler or iodine dosimetry [mol/J] | In this method, hydroxyl ions (OH•) are measured by quantifying the amount of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) produced by the sonication of water. OH• produced during US processing generate H2O2 that oxidize the iodide ions of the aqueous potassium iodide solution to produce an iodine atom. The excess iodine atoms react with iodide ions to form triiodide complex anion (I3−) that is monitored at 355 nm spectrophotometrically. The G value (radiation chemical yield) of the reaction is represented as G(I3-) = 1/2 G(OH•)I |

|

|

Rajamma, Anandan, Yusof, Pollet, and Ashokkumar [105],Sutkar and Gogate [120],Zhao, Zhu, Feng, Xu, and Wang [152],Iida, Yasui, Tuziuti, and Sivakumar [55] |

| Fricke dosimetry [mol/J] | OH• and H2O2 formed due to the sonolysis of water oxidise ferrous ions (Fe2+) into ferric ions (Fe3+) that are determined at 304 nm. Sulphuric acid was added to prevent the oxidation of Fe2+ by air, as dissolved oxygen can act as a catalyst for this reaction. The G value of the reaction is represented as G(Fe3+) = G(OH)F + 2G(H2O2)F | ||||

| Salicylic acid dosimetry | Monitoring the hydroxylation of salicylic acid is used to quantify cavitational activity, where there is an addition of OH• to the aromatic ring, leading to formation of 2,5- and 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (C7H6O). This method can be described as a radical trap that quantifies the extent of OH• production rate. The reaction products of salicylic acid dosimetry can be determined using high performance liquid chromatography. |

|

|||

| Taplin dosimetry | Taplin dosimetry performed using a two-component dosimeter with 50 % chloroform (CHCl3) and 50 % redistilled water. Chloroform is collected in the lower part of the dosimeter volume, where CHCl3 is dissociated to chlorine (Cl−) ions after US exposure. These ions react with water to form hydrochloric acid, reducing the pH of the aqueous dosimeter phase. While the upper (aqueous) phase separated within 30 min is measured for change in pH immediately after separation. The pH values are converted to concentration of hydroxonium ions (H3O+) by using the formula pH = –log[H3O+]. | Kratochvíl and Mornstein [70] | |||

| Electro conductivity method | This method measures the change in electrical conductivity of water treated with US. A small amount of dissolved N2 and O2 gas, react to form nitric oxide (NO) under the drastic conditions of high temperature and pressure caused by cavitation. This NO oxidizes to nitrogen dioxide (NO2) that reacts with water to form nitric acid (HNO3) and nitrous acid (HNO2). |

|

|

Feng, Zhao, Zhu, and Mason [33] | |

| Terephthalate dosimetry or fluorescence method [mol/J] | In an alkaline aqueous solution, terephthalic acid produces terephthalate anions that react with OH• to generate highly fluorescent 2-hydroxyterephthalate ions (HTA) that are measured using a spectrofluorometer with an excitation and emission wavelength of 315 and 425 nm, respectively. The G value of the reaction is G(HTA) = G(OH)T |

|

|

Price, Duck, Digby, Holland, & Berryman, [102],Rajamma et al. [105],Sutkar and Gogate [120],Zhao et al. [152] | |

| Sonochemiluminescence of luminol method | Under alkaline conditions, luminol is oxidized by the OH• radicals generated during cavitation. This reaction produces 3-amino phthalate (C8H5NO4−2) resulting in a blue light spectrum that is captured using a digital camera. |

|

|

Hu, Zhang, and Yang [53],Wang et al., [133] | |

| Aluminium foil erosion method | This method makes a qualitative estimation of the acoustic pressure distribution. Aluminium foil is kept in the reaction plane, i.e., parallel to the direction of the location of transducers. The erosion patterns in the foil are analysed using a high-resolution digital camera when immersed into the sonochemical reactor. |

|

|

Avvaru and Pandit [4],Chivate and Pandit [20] | |

| Electrochemical method | In this method, the change in solid–liquid mass transfer coefficient to or from an electrode during the cavitation activity is determined by voltammetry using a sonoelectrochemical cell with a stationary working electrode. |

|

|

Hihn, Doche, Hallez, Taouil, and Pollet [52],Mao et al. [83] | |

| Polymer degradation | This method is based on monitoring changes in the molecular weight of reaction mixtures during cavitational activity at different locations in the reactor. |

|

|

Chakraborty, Sarkar, Kumar, and Madras [15] |

Table 2.

Limitations and scaling-up strategies of US technologies in the food industry.

| Limitations/challenges | Scaling-up design strategy | Results | Key parameters | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wider variation of the energy dissipation rates in the bulk volume of the reactor |

|

A typical range of optimum intensity of irradiation (power dissipated per unit area of irradiating surface, W/cm2) ranges between 5 and 20 W/cm2 which is also dependent on the actual reactor system and the purpose of the US application. |

|

Sutkar, Mahulkar, and Pandit [121] |

| Fixed frequency | Multi-transducers and adjustable configurations. | Cavitation medium is intensely disturbed due to the combination of frequencies resulting, overall, in high cavitational activity due to the generation of more cavities and strong bubble–bubble and bubble–sound field interactions due to primary and secondary Bjerkens forces. | Frequency | Ye, Zhu, He, and Song [146] |

| Complex food matrix with high vapor pressure |

|

Dimethyl sulfoxide as surfactant can enhance the cavitational activity during the extraction of polyphenols from waste fruit peels. | Overall cavitational activity | Selvakumar et al. [112] |

| Designing the reactor |

|

|

Diameter and position of the transducer | Gogate et al. (2023) |

| High infrastructure and maintenance costs | Replace US cavitation with hydrodynamic cavitation. | Hydrodynamic cavitation is a cheaper technique compared to US systems in regard to the generated cavitation energy, rudimentary equipment, and low maintenance costs. | Energy consumption | Carpenter et al. [14] |

| Non-uniform cavitational activity distribution |

|

Convenient measurement of the cavitation bubble fields allows to map the sonochemical reactor. | Flow rate and cavitation bubble fields | Kerboua and Hamdaoui [63] |

3. Parameters influencing the efficiency and intensification of US processes

Process intensification of any ultrasonic application influenced by acoustic cavitation is governed by various factors. These include primarily the physical parameters of the acoustic wave, operating parameters and design aspects of the US reactors, as well as the physico-chemical characteristics of the coupling medium (medium through which the wave is transmitted to the product) and certain factors associated with the product matrix. These factors when optimized allow the US systems to harness the maximum cavitational impact that in turn results in high product quality and throughput with improved energy efficiency.

3.1. Physical acoustic wave parameters

3.1.1. Frequency

US frequency refers to the number of sound waves passing per second, and it is expressed in hertz (Hz). The ultrasonic generator produces a signal of a specific frequency, at which the transducer operates. It is mostly fixed for each transducer and manufacturers allow only a very narrow tolerance for variations. Low frequency operation (20–100 kHz) leads to the formation of large sized and transient cavitation bubbles that collapse with great intensity [75], [116]. Hence, low frequency operation is suitable for applications which require strong sono-physical effects, such as cell disruption, extraction, textile processing, polymer degradation, etc. [88].

As mentioned by Meroni et al. [88], the inverse relationship between resonance bubble size and US frequency is stated in the Minnert equation (Eq. (1)).

| (1) |

Where, f is the resonant frequency (Hz), R is the radius of the bubble (m), γ is the polytropic coefficient, p is the ambient pressure (kPa), and ρ is the fluid density (kg/m3). However, for an active bubble, there exists a range of ambient bubble radius, starting from a Blake threshold radius of 0.63 μm at 1.75 bar when the bubble undergoes large expansion at low frequency, to near the linear resonance radius of 164 μm Yasui et al. [144], Yasui et al. [145].

At higher frequencies of up to 500 kHz, sono-chemical effects become more prominent as the augmented number of bubbles at increased frequency promotes an overall increase in the yields of free radicals that are formed due to the sonolysis of water molecules; encouraging other applications, such as chemical synthesis. Overall, the ideal frequency mostly depends on a balance between the chemical effects (radical formation) and physical effects (cell fragmentation and mass transfer) and an optimum operational frequency depending upon the system conditions needs to be selected [88]. For instance, Liao et al. [60] reported that the extraction of anthocyanin from strawberry fruit gradually increased when US frequency changed from 54 to 62 kHz, reaching the highest value of 796.9 μg/g at 62–64 kHz, beyond which the yield of anthocyanin decreased as US frequency was further increased to 90 kHz.

3.1.2. Amplitude

US amplitude is expressed in µm when associated with the kinematic characteristics of the medium, and indicates the maximum height of the wave cycle or the maximum amount of displacement of the medium’s particles from its resting position [8], [77]. US transducers usually provide vibration displacement amplitudes of maximum of 20–25 µm (µm) peak-to-peak (pp).

In US sonotrode/horn/probe systems, cavitation intensity is proportional to the displacement amplitude of the incorporated US horn. The amplitude of the US vibration coming from the transducer is amplified through a significant reduction in the horn’s cross-sectional area from input to its output tip surface [97]. The resulting high-amplitude US wave is then transmitted to the liquid medium. This amplification produced by a specific type of probe is marked in terms of an amplification factor, also known as amplitude gain. The amplitude gain of the horn is inversely proportional to the diameter of its output tip. Therefore, the amplitude transmitted to the solution can be calculated by multiplying the transducer’s amplitude with amplitude gain of a specific probe provided by the supplier. While this amplitude gain factor is fixed for a particular probe, the amplitude on the US generator coming to the transducer can be controlled at different levels between 20 and 100 % for most set-ups.

Although, the amplitude setting can be controlled, it is noted that the presence of cavitation bubbles near the horn tip can indeed affect the actual acoustic amplitude at that location. The phenomenon is associated with changes in the acoustic environment due to cavitation. Cavitation bubbles, when present, can influence the local conditions of the acoustic field. The collapse of cavitation bubbles can generate high-intensity shock waves and alter the acoustic properties of the medium. In the context of an ultrasonic horn or probe, the presence of cavitation bubbles near the tip can lead to changes in the effective acoustic impedance or radiation resistance Yasui et al. [144], Yasui et al. [145]. As cavitation bubbles collapse, they create localized high-pressure conditions, which can affect the transmission and propagation of the ultrasound wave. This, in turn, may influence the effective acoustic amplitude at the horn tip. Therefore, acknowledging the impact of cavitation bubbles on the acoustic environment and their potential role in altering the acoustic amplitude is relevant in the context of ultrasound applications. For example, highest pea protein yield of 86.2 % was observed Wang, Zhang, Xu, and Ma [132] at an US amplitude of 33.7 % and other optimised pH shift parameters (pH 9.6, time 13.5 min and dilution (solid: liquid ratio 1:11.5)), in a US assisted alkaline pH shift extraction process with varying amplitude from 25 to 35 % (28.5 μm to 39.9 μm).

3.1.3. Acoustic power

Power (Watts (W)) refers to the rate at which the acoustic energy is emitted per unit time [125]and every US transducer is manufactured with a maximum input power. Power is related to the pressure amplitude of the sound wave; and the power applied should be sufficient to supply the pressure needed for cavitation (cavitation threshold). Increasing the acoustic power increases the temperature, number and size of cavitation bubbles, and the sonochemical yield. However, the phenomenon of quenching, observed under high acoustic power conditions or excess acoustic pressure beyond the threshold (6 × 102 kPa), can counterintuitively impede certain sonochemical reactions. This noteworthy consideration emphasizes the nuanced interplay between acoustic power and sonochemical outcomes and warrants careful examination in the context of the experimental design before its practical application [143]. Pressure amplitudes much higher than the threshold of the US device can lead to the formation of a bubble cloud around the transducer, causing an attenuation of the sound field and an acoustic impedance or resistance to the propagation of US waves, which will ultimately result in low energy dissipation in the mediumGogate et al. [40], Gogate et al. [44], [88], [120].

While the system is in operation, the power input can be controlled by changing the power amplitude (%) up to the maximum level set by the manufacturer. However, the actual output power varies with the volume and nature of the sample, reactor configuration and temperature increase during the process. It is usually measured in terms of effective calorimetric power (P) as discussed by Tiwari [125] assuming that the system has no heat losses as seen in Eq. (2).

| (2) |

P is the power in watt (W); Cp is the heat capacity of the solvent at constant pressure (J.g−1. °C−1); m is the mass of solvent (g); and dT/dt is the temperature rise per second.

Cui et al. [24] investigated 5 US powers (30 W to 240 W) to study their influence on the yields of polysaccharides extracted from Volvariella volvacea fruiting bodies at set US frequency of 20 KHz, 50 °C, 20 min, liquid/solid ratio of 20:1. Increasing the power from 60 W to 210 W improved the polysaccharide yields from 4.82 % to 7.63 %. However, when increasing the power to 240 W, a minor decrease of yields to 7.59 % was observed.

3.1.4. Acoustic intensity

Acoustic intensity is expressed as the power transmitted per unit area of the emitting surface of the transducer (W/cm2). It can be calculated as seen in Eq. (3).

| (3) |

Where, UI is the ultrasonic intensity, P is the US power (W) and S is the area of the emitting surface of the transducer (cm2).

The acoustic intensity is directly correlated to the US power and amplitude of the transducer [1]. A minimum intensity is required to achieve the cavitation threshold. At high acoustic intensity, the cavitationally active volume proliferates and the bubbles last longer due to an increased collapse pressure, leading to greater impact of cavitation [42]. However, further increase in acoustic intensity can lead to liquid agitation phenomenon surpassing cavitation which will eventually hinder the propagation of the sound waves in the liquid medium. Acoustic intensity decreases with an increased distance from the transducer, by the attenuation of the US waves arising due to reflection, refraction and absorption of the incident sound wave causing spatial variation of cavitational activity [42], [88], [120]. For instance, maximum protein concentration of 161.65 ± 1.12 mg/L was obtained from pineapple juice when increasing the acoustic intensity from 75 W/cm2 to 226 W/cm2, further increase in acoustic intensity resulted in decreased protein concentration, with levels of 57.88 ± 1.81 mg/L achieved at 376 W/cm2 as reported by Costa et al. [22].

3.1.5. Power density

Power density corresponds to the US power applied per unit volume (W/cm3) of sample solution [79] (Eq. (4)).

| (4) |

PD is power density; P is US power (W); and V is the volume of sample solution (cm3 or L).

Power density is vital to control the cavitation effect, as high power or high intensity when distributed in a large volume of liquid will not be effective in generating the effect of cavitation. Cavitation yield of an US equipment specifies the capacity of the system to produce the anticipated change based on the power density or the electric energy used for producing the cavitation [42]. This cavitation yield can be calculated using Eq. (5).

| (5) |

Byanju, Rahman, Hojilla-Evangelista, and Lamsal [11] varied the US power density from 2.5 W/cm3 to 4.5 W/cm3 at 20 kHz, 750 W by varying the amplitude between 20 and 40 % and the volume of the samples, which significantly increased protein extraction yields by 68.5 % and 90 %, respectively in soy flakes over the un-sonicated controls.

3.2. Mechanical parameters for the design of a reactor

3.2.1. Immersion depth of US probe

Immersion depth of the probe (for US probe /sonotrode system) and height of the liquid in the reactor (for plate transducers in a US bath system) affects the reflection and refraction phenomenon of the acoustic waves on the liquid and the reactor’s wall surfacesGogate et al. [40], Gogate et al. [44]. This parameter also impacts the hydrodynamic characteristics of the liquid motion and cavitational activity distribution. Placing the probe close to the bottom or base of the reactor leads to increased reflection of sound waves which widens the cavitation zones [42],Gogate et al. [40], Gogate et al. [44]. While placing the probe further away from the bottom leads to attenuation of the acoustic waves. To increase the cavitational intensity, some studies suggested an immersion depth of 2–5 mm inside the liquid for horn type systems, and a maximum liquid depth of 15 times the wavelength or an odd multiple of 1/4th of the wavelength of the acoustic wave for plate type transducers. However, an optimum value should be ascertained based on the reactor system, liquid flow, operational parameters and the desired application [88].

3.2.2. Ratio of diameter of probe/transducer to the diameter of the reactor vessel

In case of a large reactor size, the higher the ratio immersion probe diameter to reactor vessel diameter, the more widespread will be the cavitational activity, inducing increased power dissipation in the medium, overcoming acoustic impedance until reaching an optimum value Gogate et al. [40], Gogate et al. [44]. Vessel diameter-transducer diameter ratio has been reported to be somewhere close to 1.5 to 1.45 for significant sono-chemical efficiency. Probe diameters higher than that will cause a decrease in the acoustic amplitude delivered to the reactor medium [88].

3.2.3. Position of the transducers in the reactor

More the distance from the transducer, translates in lower acoustic intensity and energy dissipation in the bulk volume of the reactor, with increased formation of passive or dead cavitation zonesGogate et al. [40], Gogate et al. [44], [88]. This distance also affects the mixing motion and hydrodynamic characteristics of the coupling medium in the reactor, as the acoustic streaming from the transducer may help in providing efficient bulk mixing in a small volume [88].

3.3. Operational parameters

3.3.1. Duty cycle

The US signal can be delivered in a continuous, pulsed or sweeping modes [88]. When US is used in a pulsed mode, acoustic energy is transmitted in short bursts or pulses and the average intensity of the output over time is low. In pulsed US, US output is cycled as ‘ON’ time which signifies the pulse length and ‘OFF’ time is the pulse interval [111]. Duty cycle is the percentage of time during which the US signal is ‘ON.’ Pulsed mode limits local temperature rise, lowers bubble coalescence, and increases active cavitation zones. While in case of continuous US (duty cycle: 100 %), acoustic energy is transmitted continuously, and acoustic intensity is constant over time [88]. Continuous irradiation may produce excessive amount of bubbles which coalesce to form clouds helping in degassing but these clouds can also cause acoustic decoupling (cavitational blocking) and attenuation of signal [88]. US transducers with sweep bandwidth and sweep frequency, a symmetric deviation about the centre frequency, may show mixed performance. All these signal modes should be optimally used based on the reactor set up and applications desired.

3.3.2. Liquid flow

Agitation or stirring in addition to the hydrodynamic movement generated by the acoustic cavitation is helpful for bulk mixing in large scale operations that can reduce acoustic attenuation, bubble cloud formation, impedance, decoupling and improve acoustic energy efficiency. Too high agitation can also reduce the number of bubbles formed and in turn reduce the acoustic efficiency. An optimum design, positioning and speed of agitators can be established based on the final aim of the US equipment. The flow rate of the liquid, in case of continuous US systems, also influences the amount of the liquid passing through the active cavitation zones [120].

Enhanced agitation or stirring, complementing the hydrodynamic motion induced by acoustic cavitation, proves beneficial for promoting bulk mixing in large-scale operations. This dual approach helps to mitigate acoustic attenuation, bubble cloud formation, impedance, and decoupling, thereby improving acoustic energy efficiencyGogate et al. [40], Gogate et al. [44]. It is crucial to note that excessive agitation might counterproductively diminish the number of bubbles formed, thereby reducing acoustic efficiency. Striking a balance is essential, and optimal design, positioning, and speed of agitators can be tailored based on the specific objectives of the US equipment.

Considering the potential quenching effect at excessive acoustic power, it is noteworthy that appropriate liquid flow plays a pivotal role in suppressing quenching. In this context, the flow rate of the liquid becomes a critical parameter, particularly in continuous US systems [143]. The interplay between liquid flow and the active cavitation zones should be carefully considered and optimized to ensure effective and controlled sonochemical reactions, taking into account the quenching phenomenon observed at higher acoustic power levels [120].

3.3.3. Temperature of the solvent medium

In the range of 20–60 °C, increasing the temperature of the solution reduces the viscosity and surface tension of the liquid and increases its liquid vapour pressure. The extent of increase in liquid vapour pressure is higher than the liquid temperature (Ti) as explained in Equation (6). As discussed by Sutkar and Gogate [120], the local temperature of the cavity reached during collapse should be higher compared to the surrounding liquid temperature (Tf)

| (6) |

Where Tf is final temperature, Pi and Pf are initial and final vapour pressures and ƴ is polytropic coefficient of gas. Thus, it is estimated that the cavitational activity will be reduced at very high operating temperature in the reactor [120].

Moreover, high temperatures can degrade heat sensitive components in the treated product. Hence, temperature-controlled US treatments using jacketed vessels and heat exchangers need to be put to place, representing an additional processing cost. However, high temperatures increase the kinetic energy of the gas bubbles, decreasing their solubility in the liquid, thereby reducing the number of available cavitation nuclei. Hence, an optimum temperature of operation will be mostly dependent on the application needed for specific processes. Changes in the bulk temperature can be monitored by using thermocouple or thermister placed at any position in the reactor, while the collapse temperature can be measured by thermocouple/thermister having very low response time [120].

3.3.4. Treatment time

Prolonged US treatments may lead to excessive cavitation and it can cause unwanted structural and physicochemical changes in the product, possible plateauing and thereafter reduction of the reaction or mass transfer rate after initial increase [82]. For example, Özyurt, Tetik, and Ötleş [93] extracted the highest yields of protein from cold pressed tomato seed waste by applying 1.5 to 2 min of US treatments at 210 W and 24 kHz, while higher treatment times of 3.5 min and above resulted in decreased protein yields. Similarly, the maximum protein yield from defatted rice bran at US power fixed at 15 W/g was achieved by treatments of 2 min, decreasing when treatment times increased from 2 to 5 min [82].

3.4. Physicochemical properties of the coupling medium

3.4.1. Viscosity of the solvent

High viscosity of liquid medium not only reduces mass transfer rate of the solvent, but also increases cohesive forces in the medium to increase the cavitation threshold. High viscosity also reduces the active cavitation zone, increasing attenuation of the acoustic wave. However, samples with low viscosity could also lead to increased bubble coalescence reducing acoustic intensity [88].

3.4.2. Surface tension of the solvent

During nucleation of bubbles, liquids with high surface tension provide increased resistance to mass transfer during compression phase of the acoustic wave, but during later stages, this surface tension stabilizes the growth of the bubbles. Surfactants, such as sodium dodecyl sulphate, dimethyl sulfoxide in the system, and other ionic surfactants will get adsorbed at the gas–liquid interface, and thus, their addition can reduce bubble coalescence [88], [120].

3.4.3. Dissolved gases and liquid vapor pressure

Dissolved gases in the liquid help to build and grow the cavitation bubbles through rectified diffusion until these bubbles reach a critical size beyond which they are incapable to withstand the internal vapour pressure leading to their rupture or implosion. However, higher liquid vapor pressure may lead to increased vapour content of the bubble cavity resulting in cushioned collapse and reducing the energy released during their collapse. On the other hand, ultrasonication leads to degassing which can reduce nucleation and cavitational yield, hence gas bubbling into the medium can be done to retain cavitation. Gases having high thermal conductivity will lose heat to the surrounding liquid and quickly reach low temperatures during the collapse of the bubbles (collapse temperature). The solubility and polytropic constant of the gas will also impact the acoustic cavitation [120] as seen in Eq. (7).

| (7) |

Where Ti is the initial temperature of liquid, Tf is final collapse temperature of the adiabatically collapsing bubble, ƴ is polytropic coefficient, Ri and Rf are the initial and final radius of the cavitating bubbles, respectively.

3.4.4. Presence of dissolved salts

The inclusion of solid particles, particularly salts (NaCl, NaNO2, and NaNO3), primarily serves to introduce additional nuclei, thereby promoting cavitation activity. However, it is essential to note that the presence of solids can also result in the scattering of acoustic waves, leading to the attenuation of cavitation. Moreover, dissolved salts can significantly impede bubble–bubble coalescence. The overall impact of these dual phenomena is system-dependent, emphasizing the necessity for optimization before determining operational parameters for practical applications [34], [120], [142].

3.5. Product parameters

The product being ultrasonicated and its properties and prior processing also influences the impact of the ultrasonication process. Smaller particle size of the product being treated helps to increase the surface area of contact between the product and the coupling media, if they are in direct contact during the US treatments. It also lowers the average diffusion path within the solid matrix of the raw material, helping in mass transfer during the extraction applications and improving the reaction yields [30], [116]. Pre-treatments, such as hydration of the solids before ultrasonic reaction may help to facilitate solvent penetration during ultrasonic reaction improving reaction rate. Solid: solvent ratio or dilution ratio, when increased, it usually helps to increase the yields of extraction reactions as the concentration gradient between the solvent and the extraction matrix contributes to increase the mass transfer of compounds [101], [108], [116]. But with course of time, if the viscosity of solution increases and the solvent gets saturated with the product, acoustic impedance will occur resulting in reduced reaction rates.

4. US reactors and scale-up strategies for process intensification

An ultrasonic reactor is constituted by an electric generator that converts utility power into a conforming high-frequency alternating current to drive the ultrasonic transducer [137]. The transducer then converts the electrical energy into sound energy to be delivered to the medium containing the product to be treated either in direct or indirect contact. Conventional probe-based systems consist of a horn driven by the transducer, helping to deliver the radiation to the product that is usually in direct contact with the medium. However, newer designs of probe-based systems also allow indirect contact. US bath systems with enclosed transducers fixed inside their walls allow for an indirect contact with the product, although they can also be used in direct contact for other applications, such as cleaning of materials [88]. Flow cells with US emitting walls or with sonotrodes inserted into the cell’s cavity are always in direct contact with the product and they are generally used in continuous US reactor systems. US bath systems are always operated in batch conditions, while probe systems can be operated in batch mode or coupled with flow cells to aid during continuous operations. Laboratory scale ultrasonic reactor systems can typically handle volumes ranging from mL to a few L needed for research and clinical applications. The scaling-up of these reactors for the commercial applications as needed in multiple industries can be challenging as the efficiency of ultrasonic cavitation will be influenced by the various factors as described previously in Section 3. One of the primary challenges faced while scaling-up an ultrasonic process is the increase in size of the reactor to hold larger processing volumes that leads to an increase in the distance of the bulk of the liquid from the concentrated US emitting zone of the transducer [119]. As a result, cavitation bubbles may not be uniformly distributed throughout the reactor, leading to formation of dead cavitation zones and reduced dissipation of acoustic energy and intensity as explained in Section 3.2.

In order to overcome such limitations and intensify the ultrasonication process, several strategies to upgrade the ultrasonic reactors and their operation are being proposed and investigated (Table 2). A single modification can help to address more than one challenge of the multiple issues faced when working to retain or enhance the efficiency of acoustic cavitation during the scale-up. In this section, we have highlighted the technological innovations that have been introduced in the design and manufacturing of the essential components of US systems and their configuration and arrangement. These critical innovations can be potentially exploited to scale-up US applications at pilot and industrial scales with benefits of intensified cavitation, efficient acoustic energy transfer and distribution, improved process control and enhanced end product yield and quality.

4.1. Technological improvements in the design of transducers

Transducers can be of various types based on their vibrating element, being the magnetostrictive and piezoelectric transducers more commonly used than the liquid-driven ones. Magnetostrictive transducers vibrate due to the expansion and contraction movement of the ferromagnetic core material induced by the alteration in the magnetic field by the alternating electric current [2]. The sandwich type piezoelectric transducers discovered by Langevin in 1920 vibrates when the piezoelectric elements (ceramic rings) get mechanically compressed between a front and a back mass and undergo dimensional changes when excited by the electric current [2]. Piezoelectric transducers have been regarded as the most cost-effective choice, especially for low frequency high intensity US application [28]. These transducers fixed to sonotrodes/probes or horns acting as amplifiers have been widely used at laboratory and industrial level to deliver high intensity focused acoustic irradiation through a concentrated cavitation zone around the sonotrode. Further insights into the design and function of US probe systems are explained in detail in Section 4.2. Plate type transducers consist of a stainless-steel plate irradiated by a stack of multiple piezoelectric type transducers welded together inside a metal box (Fig. 2a), that deliver sound waves diffusely, generating primarily a stable cavitation or a repeated transient cavitation.

Fig. 2.

Different types of transducers (a) plate type [115]; (b) scheme of high power extensive area radiator; (c) circular stepped plate transducer; (d) rectangular stepped plate transducer; (e) grooved plate transducer; (e) stepped-grooved plate; (f) flat-plate transducer with reflectors; (g) flat-plate transducer with reflectors; (h) transducer with cylindrical radiator; (i) fluidised bed radiator [104]; (j) air cooled transducer [56]; and (k) water cooled transducers [58]. Figures from (b) to (h) were adapted with permission from Gallego-Juárez et al. [36].

Since industrial-scale US processors require horns having larger output diameter, they run at progressively lower amplitudes and cannot produce high cavitation intensities [98]. The classical design of transducers fitted with horns act as extensional vibrators and their cross-sectional dimensions need to be smaller than ¼ of the acoustic wavelength to avoid coupling with radial vibrations. When these transducers are run at high power, multiple non-linear phenomena, such as frequency shifts and modal interactions, occur during the US treatments reducing the performance of these operations [36]. Plate transducers also cause modal interactions when used at high power, directing the acoustic energy towards unwanted large amplitude vibrations, hampering power dissipation [36]. To overcome such limitations, especially at large scale and for their applicability for gas and liquid medium, a handful of design modifications of the transducers have been explored. The family of high-power transducers with extensive area radiator comprises of several forms depending on the shape and/or the profile of the radiator. These transducers have been particularly used for applications in fluid and multi-phase coupling media especially in gases which otherwise face high acoustic absorption [36]. Hence, these radiators are designed to reduce the non-linear phenomenon of the longitudinal vibrating transducers and to provide good impedance matching between the ultrasonic radiation source and the coupling medium [36]. They can simultaneously focus beams of high energy and deliver large amplitude of vibration through the extensive radiating areas for bulk irradiation in large-scale industrial applications [36]. These systems generally consist of a vibrator, which constitutes of a piezoelectric transducer and a solid horn acting as the vibration amplifier, driving the extensive radiator which vibrates in one of its flexural modes (Fig. 2b). The different shapes of the radiators fabricated till date include the (i) stepped-plate transducer which can be further classified into directional stepped profile, focusing stepped profile, circular stepped-plate and rectangular stepped-plate, (ii) grooved plate transducers, (iii) stepped-grooved-plate transducer, (iv) flat-plate transducer with reflectors, (v) transducer with cylindrical radiator [36].

The shape and geometry of the stepped plate transducers allow to control the radiation in such a way that the direction and distribution of the ultrasonic vibration can be regulated as needed (Fig. 2c and d), while the grooved plate transducers (Fig. 2e) focus the radiation by uniformly distributing the amplitude, separating untuned vibration modes and preventing modal interactions. When combined (Fig. 2f), they complement each other to provide directional (stepped) and focused (grooved) vibrations [36]. The flat plate transducers with reflectors (Fig. 2g) put in phase the radiations emanating from plate zones vibrating in counter-phase [36]. In cylindrical radiators, the entire cylindrical vibrating chamber acts as the ultrasonic radiator as seen in the tubular radiator (Fig. 2h) and in the fluidized bed ultrasonic dryer (Fig. 2i) delivering high intensity acoustic radiation to dry particulate materials using forced air as the coupling medium [104].

An efficient cooling of transducers is also needed to counteract the heat generated during their operation and to allow their long-term use. Conventional transducers, typically cooled by forced air (Fig. 2j), are susceptible to overheating and they are exposed to flammable vapours and moisture, which may be carried by the air into the internal area of the transducers where high-voltage contacts are located Industrial Sonomechanics and Florida [56]. To overcome this, modern transducers are water-cooled (Fig. 2k), preventing overheating even in continuous operations and sealing the transducers from the external environment, making them resistant to high humidity conditions and vapours from processing of flammable organic solvents Industrial Sonomechanics and Florida [58].

4.2. Technological improvements of US probe systems

Sonotrodes/horns/probes are metal rods fitted to the transducer of an ultrasonic system to transmit acoustic vibrations to the product being treated and they can be used for both batch and continuous applications. The shape of the sonotrode determines the final amplitude being delivered to the product governed by its amplitude gain factor or amplitude ratio as explained in section 3.1. Titanium alloys are the current preferred choice for manufacturing sonotrodes as they have high surface hardness, good fatigue strength and encounter lesser vibration loss Ultraschall and Emerson [127]. These can be coated with nickel, chrome, carbides, nitrides of titanium and polytetrafluoroethylene for high amplitude operations [88]. Nevertheless, their erosion through prolonged use, especially at high frequencies reduces their lifetime and poses a hazard of metal contamination in the treated product. Chrome or nickel coated aluminium, stainless steel are cheaper alternatives that are mostly used for low-amplitude applications [35].

Based on its geometry the sonotrodes can be classified into several types (Fig. 3a) including (i) stepped, consisting of two distinct sections of uniform cross-sectional area; (ii) conical, with a tapering cross section; (iii) exponential, gradually tapering cross-sectional area following exponential equation; and (iv) hyperbolic, combining stepped and exponential design.

Fig. 3.

US probe systems (a) geometric profile of different US probes; (b) water cooled US probe system adapted with permission from Suchintita Das et al. [116]; (c) booster use to amplify amplitude [127]; (d) block sonotrodes [50]; (e) Cascatrodes™ [50]; (f) multi-stepped horn and its acoustic transmission area highlighted by sonochemiluminescence adapted with permission from Wei et al. [136]; (g) full and half-wave Barbell Horn [99]; (h) 4-finger sonotrode [50]; (i) VialTweeter [50]; (j) CupHorn [50].

To regulate the increase in temperature during sonication, US probe system reactor vessels need to be temperature-controlled especially when processing temperature sensitive products through various means such as using a cryogenic fluid flowing through jackets or through use of heat exchangers (see Fig. 3b). To intensify the acoustic amplitude and energy transmitted by the probes, several strategies are being examined. The use of boosters fitted in between the transducer and the sonotrode helps to amplify the acoustic wave amplitude (Fig. 3c). Boosters are manufactured with different boosting or gain factors, and the final amplified amplitude can be calculated by multiplying the boosting factor with the original amplitude delivered by the transducer and with the amplification gain factor or amplitude ratio of the horn. For instance, Hielscher Ultrasonics GmbH (Teltow, Germany) manufactures boosters having gain factors ranging from 1.2 to 2.2.

The stepped horns can have block shapes as those manufactured by Hielscher Ultrasonics GmbH (Fig. 3d) for industrial use [51]having a single large surface area. CascatrodeTM of Hielscher Ultrasonics GmbH (Fig. 3e) has multiple ring like segments along its length [51], transmitting acoustic radiations from its tip and radially from the surfaces of the different segments, inducing multiple cavitation zones similar to a multi-stepped horn with a conical tip (Fig. 3f) as fabricated by Wei et al. [136]. The Barbell horn ultrasonic technology (BHUT) patented by Industrial Sonomechanics (Miami, Florida, USA) is featured in their “full and half-wave Barbell horn” (Fig. 3g) having a tip with a diameter of about 50 mm and two radiating surfaces, one below the output tip and another in the area above the tip and below the thinnest part of the neck, that can generate ultrasonic amplitudes over 100 μm, resulting in a scale up factors of up to 50 from normal laboratory scale horns [98], [99]. The 4-finger sonotrode (Fig. 3h) of Hielscher Ultrasonics GmbH features 4 ultrasonic probe tips compositely fitted to the transducer for the direct sonication of 4 samples simultaneously [51]. VialTweeter (Fig. 3i) another innovation by Hielscher Ultrasonics GmbH is a block sonotrode that irradiates a vessel having 10 slots to indirectly sonicate 10 samples simultaneously with equal intensity [51]. The Cup Horn reactor fabricated by Hielscher Ultrasonics GmbH (Fig. 3j) consists of a reactor vessel glued to a US sonotrode which functions similar to a strong intensity US bath but weaker than an US probe system due to the increased emission surface area. These can directly sonicate solutions filled in its cavity or indirectly sonicate vials or test tubes filled with sample solution and placed inside a water filled cavity [51].

4.3. Technological improvements of US bath systems

US bath systems have been widely commercialised at industrial scale especially for cleaning applications (Fig. 4a). They usually consist of a rectangular stainless-steel tank with enclosed piezoelectric transducers attached to its bottom and/or side walls. These units can be manufactured to operate at variable frequencies, power and with heating/cooling systems. The coupling liquid medium, mostly water, is filled inside the tank and the product to be treated can be directly placed inside or indirectly irradiated by placing it in a vessel (degassed water is preferred). The thickness and position of this vessel determines the acoustic intensity received by the product. US bath system innovations have been mostly focused on the incorporation of external cavitation intensifying accessories to improve acoustic energy distribution during the US process. Submersible versions of mobile plate transducers can be fitted to the walls at different positions of the US bath to provide additional cavitation, such as the TSP-P Powersonic manufactured by KLN Ultraschall GmbH (Trenton, New Jersey, USA) Ultrasonics and AG, C. U. C., Trenton, USA, [66] and the immersible transducer by CTG Asia, Suzhou, China (Fig. 4b) (Cleaning Technologies GroupCleaning Technologies Group [21]. Cavitation intensifying bag (CIB) (BuBble bags by BuBclean, Enschede, The Netherlands) is a scaled-up microfluidic sono-reactor, modified to include pits or indentations in their inner surfaces to entrap gas bubbles when a liquid is poured into it, enhancing the cavitational activity [10]. Rivas et al. [106] and van Zwieten, Verhaagen, Schroën, and Fernández Rivas [130] reported that the use of CIBs immersed in an US bath or positioned in it using a customised hanging rod over the transducer (Fig. 4c) led to an efficient generation of cavitation-related effects when used for emulsifying applications.

Fig. 4.

US bath systems (a) schematic representation of a typical bath system adapted with permission from Suchintita Das et al. [116]; (b) immersible transducer fitted to walls of US bath [21]; (c) Cavitation Intensifying Bag [10].

4.4. Technological improvements of US flow cells or reactor chambers

Flow cells or reactor chambers which are mainly operated at continuous mode can either have walls fitted with multiple transducers or designed to have one or more sonotrodes entering into its cavity. Continuous processing through use of these flow cells in a closed system can help to overcome the limitations of low throughput and high wastage encountered with batch processes for suitable applications.

For continuous processing, flow cells which are mostly manufactured with stainless steel or glass are connected with a pump to a sample feed tank from which the sample is continuously pumped at an optimised volumetric flow rate into the reactor cell through an inlet connection. Inside the cell chamber, the solution undergoes ultrasonication and then passes through the outlet connection to the processed sample holding tank. The geometry of the chamber offers the formation of uniform active cavitation zones throughout the solution volume processed inside its chamber during single or multiple passes. However, the flow cell geometry needs to be optimally chosen to facilitate the uninterrupted flow of solid-loaded fluids and their homogenous sonication. These chambers can also be temperature controlled with a cooling system in place that can be either jacketed chambers with cooling water connections or separate heat exchangers fitted in to the processing line. Some manufacturers including Hielscher Ultrasonics GmbH have the facility to pressurize the industrial scale ultrasonic flow cells up to 300 atm, resulting in an increased fluid density and intensified acoustic cavitation. Hielscher Ultrasonics GmbH flow cells (Fig. 5a) can handle flow rates ranging from 10 to 100 L/min for industrial applications [39].

Fig. 5.

US flow cells (a) large scale US flow cell adapted with permission from Gholami, Pourfayaz, and Maleki [39]; (b) continuous flow cell reactor system, ISP-3600 [57].

Fig. 5b illustrates a complete process line system (ISP-3600) constituting an industrial scale continuous ultrasonic reactor flow cell incorporated with a Half Wave Barbell horn fitted to a water-cooled piezoelectric transducer and connected to a heat exchanger for cooling the reactor and a pump to the product storage tank with integrated mixer, fabricated by Industrial Sonomechanics, Miami, Florida, USA for industrial scale operations Industrial Sonomechanics and Florida [57].

Various modifications of the design and set up of flow cells have been researched, offering promising results for large scale operations, including (i) continuous reactors with walls fitted with multiple transducers; and (ii) continuous reactors with multiple sonotrodes incorporated into the cavity of the reactors.

-

(i)

Continuous reactors with walls fitted with multiple transducers irradiated at the same or different frequencies

The flow reactors can have more than one radially vibrating transducer of same or different frequencies fitted or mounted on the walls of the reactors. These flow reactors can have also different geometries: polygonal, tubular and rectangular or flat bed. Gogate, Mujumdar, and Pandit [41] designed the triple frequency hexagonal flow cell reactor featuring 3 transducers of 150 W each, operating at 3 different frequencies, 20, 30 and 50 kHz, fitted on each face of the hexagon. This led to 7 different combinations of operating frequencies that resulted in total power dissipation of 900 W, when using all the transducers with a combination of 20 + 30 + 50 kHz frequencies (Fig. 6). The use of this flow cell to study formic acid degradation during US treatments revealed that there was a 20 % reduction in power density compared to the use of a dual frequency flow cell and an ultrasonic bath. However, the net formic acid degradation increased by 18 % and 68 % compared to a dual frequency flow cell and ultrasonic bath, respectively. The triple frequency flow cell had 48 % more cavitational yield compared to the dual frequency flow cell and 110 % more compared to the ultrasonic bath [41].

Fig. 6.

Triple frequency hexagonal flow cell adapted with permission from Gogate et al. [41].

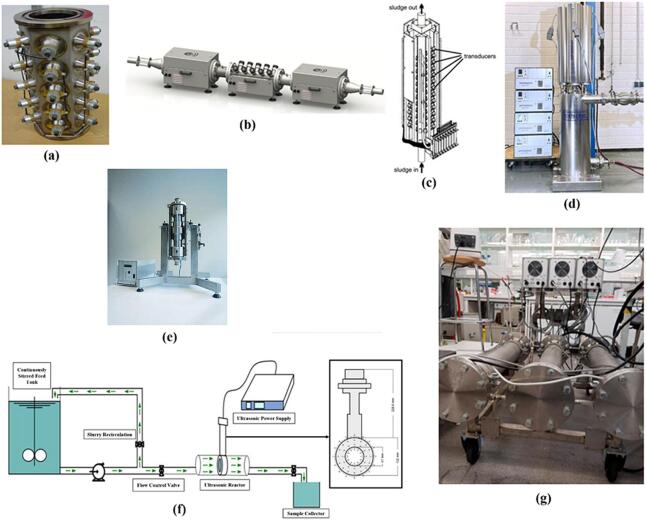

In case of tubular reactors, their cylindrical geometry fitted with transducers on their walls have the advantage of allowing the ultrasonic emitting field to be focussed on the central area of the tube instead of impacting the inner surface of the walls that are protected from cavitational degradation [88]. Few of the commercially available tubular design reactors include: (i) the tubular resonator designed by KLN Ultraschall GmbH, Crest Ultrasonics Corp. (New Jersey, Trenton, USA) with 30 transducers with frequencies ranging between 20–40 kHz attached to its walls (Fig. 7a); (ii) the FLOW:WAVE® reactor by UNITECH Srl (Villa del Conte (PD), Italy) (Fig. 7b) with multiple transducers operating at double frequencies of 20/40 kHz attached to its walls Unitech [129]; (iii) the pilot-scale ultrasound reactor SORA 3 by STN ATLAS Elektronik (Bremen, Germany) with maximum power consumption of 3.6 kW and 12 piezoceramic flat transducers at each of the four sidewalls (Fig. 7c) fixed at 31 kHz and acoustic intensities varying within the range of 5–18 W/cm2 [91]; (iv) the MultiSonoReactors MSR-4 and MSR-5 made by Hielscher Ultrasonics GmbH which can hold 4 or 5 ultrasonic transducers together Hielscher Ultrasonics [49](Fig. 7d). Other tubular reactors include the SONITUBE flow reactor produced by SYNETUDE (Cognin, France) (Fig. 7e) with adjustable frequency between 20 and 35 kHz and flow rates ranging between 200 and 500 L/h [122], useful for certain applications, such as US-assisted enzymatic liquefaction and extraction of R-phycoerythrin from red seaweeds [76], production of methyl esters from vegetable oils [80], and microorganism inactivation in milk [23]. A similar reactor with a donut shaped transducer named Sonix was fabricated by Branson Ultrasonics (Danbury, CT, USA) operating at 3.3 kW and 20 kHz (Fig. 7f) and was used to saccharify corn slurry at flow rates between 10 and 28 L/min by Montalbo-Lomboy et al. [89]. Tamminen, Holappa, Gradov, and Koiranen [124] compared the extraction yield of chlorophylls and carotenoids from spinach leaves using a laboratory scale US reactor (Hielscher Ultrasonics flow cell FC22K, 24 kHz, power density 2500 W/L) and a pilot scale continuous jacketed tubular US reactor (25 kHz and power density 1500 W/L). In this pilot scale reactor, the sonotrode was placed in the centre of the reactor and the process side tubing containing the solution was coiled as a helix around it and the temperature controlled by a heat transfer fluid flow cooling system (Fig. 7g). The authors stated that in order to achieve equal extraction yield, a 2.5-fold higher volume-specific US power is required in the pilot scale reactor compared to the batch laboratory scale US flow cell. Three of these pilot scale tubular reactors were used in tandem for sonocrystallization applications by Ezeanowi, Pajari, Laitinen, and Koiranen [31].

Fig. 7.

Tubular flow cell reactor designs (a) tubular cell reactor with 30 transducers [67]; (b) FLOW:WAVE® reactor [129]; (c) pilot scale US reactor (system SORA 3, STN ATLAS Elektronik, Bremen, Germany) adapted with permission from Nickel and Neis [91]; (d) MultiSonoReactor, MSR-4 and MSR-5 (Hielscher © 2023); (e) SONITUBE flow reactor [122]; (f) donut shaped transducer (Sonix, Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT,USA) adapted with permission from Montalbo-Lomboy et al. [89]; (g) tubular reactor with helical coil adapted with permission from Ezeanowi et al. [31].

A rectangular reactor (length = 1,000 mm, width = height = 80 mm) manufactured by BANDELIN electronic GmbH & Co. KG (Berlin, Germany) was investigated for sewage sludge sonication by Lippert et al. [80]. These reactors could be run at a flow rate of 100 L/h (Fig. 8a) with 6 transducers operating at a fixed frequency of 25 kHz (300 W) fitted to the top and bottom surface of the walls of the reactor chamber enclosed in a flat-bed housing. Another similar flat-bed rectangular reactor by BANDELIN electronic GmbH & Co. KG was also used to disintegrate waste activated sludge [81]. This flat-bed reactor has an adjustable length and height reaction chamber, formed by two parallel ultrasonic plates each of them fitted with 10 transducers of fixed frequency (25 kHz) and enclosed in a steel case (Fig. 8b).

-

(ii)

Continuous reactors with multiple sonotrodes, irradiated at same or different frequencies, incorporated into the cavity of the reactors.

Fig. 8.

Rectangular reactors (a) rectangular reactor adapted with permission from Lippert et al. [80]; (b) flat-bed rectangular reactor adapted with permission from Lippert et al. [81].

Continuous reactors with multiple incorporated sonotrodes irradiated at different or equal frequencies deliver high-intensity, focused ultrasonication in flow cell systems. A continuous flow cell reactor fitted with 2 sonotrodes (Fig. 9a) working simultaneously at dual frequency of 20/40 kHz in a pulsed mode (on and off-time of 5 and 2 s, respectively) led to a power density of 220 W/L during pre-treatment of sunflower meal solution followed by alkaline pH shift for protein isolation [25]. The ULTRAWAVES high-power BIOSONATOR ultrasonic reactor system by Wasser- & Umwelttechnologien GmbH (Karlsbad-Ittersbach, Germany) incorporates a looped design for the solution flow consisting of 5 sonotrodes operating at 20 kHz frequency Ultrawaves - Wasser- und Umwelttechnologien GmbH, Germany, [128]. This looped structure prevents deposition of solid particles around the sonotrode tips and inside the chamber cavity (Fig. 9b). Two or more US probes (dual frequency system) can also be incorporated into a reaction vessel fixed at different angles. For instance, Zhang et al. [149] analysed soluble protein content in soy milk treated by different positioning of US sonotrodes inside the flow cell reactor. The authors used 2 US probes operating under multi-angle dual frequency (40 + 20 kHz at angles of 0°, 30° and 45 deviated from the vertical baseline) with 2 m distance between the transducers, and single frequency probes operating individually at 40 and 20 kHz and placed vertically (0° away from the vertical baseline) as seen in Fig. 9c. Sweeping mode was used with sweeping amplitude operating at centre frequency ± 1 kHz, and a sweeping period of 100 ms. Treatments at 40 + 20 kHz caused an increase of soluble protein of 20 % and 12 % compared to individual 40 kHz and 20 kHz treatments, respectively [149]. Multiple transducers of variable frequency fitted into the reaction chamber help to reduce the use of a very high single frequency transducer, thereby protecting the life of the individual transducers and preventing metallic corrosion Gogate et al. [40], Gogate et al. [44]. Multi-frequency transducers operating simultaneously also provide advantages as the interaction between different acoustic waves at various frequencies is greater than the effect of the sum of the individual frequencies, resulting in a significant rise in cavitation yield and substantial energy efficiency [45]. The use of multiple transducers permits to decrease the power dissipation per unit area while maintaining the required power dissipation levels in the reactor Gogate et al. [40], Gogate et al. [44].

Fig. 9.

Continuous flow cell reactor designs fitted with multitransducers (a) continuous flow cell reactor fitted with 2 sonotrodes adapted with permission from Dabbour et al. [25]; (b) BIOSONATOR [128]; (c) flow cells with 2 sonotrodes fixed at different angles adapted with permission from Zhang et al. [149].

Other advancements in the ultrasonic flow cell design include the design and use of accessories, such as the MultiPhase Cavitator Insert (InsertMPC48) manufactured by Hielscher Ultrasonics GmbH (Fig. 10a) that when fitted to the flow cells inject liquid or gas through 48 very fine cannulas into the liquid phase inside the cavitation zone. This results in very fine droplets that have an increased surface area of contact, facilitating phase-transfer-reactions and sono-crystallization applications [48]. Hielscher Ultrasonics GmbH in co-operation with ETH Zürich developed a special flow reactor named the Ultrasonic Mini Flow Cell which encases a glass tube for the liquid flow and the reactor is irradiated with a sonotrode (Fig. 10b). In this reactor, the sonotrode is not in contact with the liquid, and thus, the liquid inside the closed glass tube is free from any metallic residues arising from wear and tear of the sonotrodes or from any air borne contaminants [50].

Fig. 10.

Special accessories for flow cell reactors (a) MultiPhase cavitator insert (InsertMPC48) [48]; (b) ultrasonic Mini Flow Cell [50].

5. Mechanisms and mathematic modelling of US-assisted processes in the food industry

5.1. US-assisted brining

Brining, a common practice in food industry, encompasses two mass transfer processes: water migration from the food matrix to the brine, and solute migration from the brine to the matrix. There are several issues associated with current brining and marinating processes. Firstly, brining often requires a high NaCl content, which requires a final “desalting” process before the products can be sold. Secondly, due to the limited permeability of salt in the cell membrane, it usually takes hours for brined samples to reach a certain concentration of salt, which can result in enzymatic softening, structural damage, and bloating McMurtrie et al. [87].

The use of US in these processes offers several advantages over conventional brining method and it could potentially solve some of the issues associated to these conventional processes. Cavitation during the US process generates localized high pressures and temperatures, which results in the release of energy. These dynamic conditions improve the mass transfer of salt and flavour compounds into the food, accelerating the brining process. The micro-jets and liquid streams generated by cavitation can agitate the brine [7]. This agitation increases the penetration of the brine into the food, allowing the salt and flavouring agents to reach the deeper layers of the food effectively, leading also to uniform distribution of flavours and salt throughout the food, enhancing the sensory characteristics of the final product [110]. In addition, US affects the protein structure of meat and seafood [92], [141]. The mechanical vibrations disrupt the protein matrix, causing changes in the texture of meat that can be used for the tenderization of meat, helping to break down connective tissues and increasing water retention, resulting in juicier and more tender final products [96].

The factors that affect the ultrasonic enhancement of brining can vary depending on the final applications and more mathematical models need to be developed for large scale brining processes. Several equations have been proposed for cheese brining process assisted by US [109] for both the mass transfer (Eq. (8)) and brine transfer (Eq. (9)). The equation based on the combination of microscopic mass transfer balance with Fick’s law are as follows:

| (8) |

where is the local concentration of either moisture or NaCl in the cheese, is the effective diffusional coefficients for either water or salt, is the time, and are the characteristic coordinates of each geometry.

Regarding NaCl and water transfer, it could be fitted to the Arrhenius equation:

| (9) |

Where is the osmotic solution temperature and is the gas constant. Thus, the influence of brine temperature during sonication on mass transfer can be elucidated.

5.2. US-assisted freezing and crystallization

Freezing plays an important role in the preservation of fresh biomass. The process of freezing and crystallization are interlinked as the main principles of the freezing process consist of an initial ice nucleation followed by crystal growth within an unfrozen aqueous phase. The quality of frozen foods is closely related to the location and size of the ice crystals and the formation of these crystals depends on the rate of freezing. Rapid freezing results in small intracellular ice crystals, which are desirable for high-quality products. Therefore, increasing the freezing rate can significantly enhance the entire freezing process and preserve the original quality of food. Additionally, freezing can also be employed for drying and concentration purposes [17].

US is a promising technology for enhancing the freezing rate and controlling the formation and distribution of ice crystals [150]. US can disrupt ice crystal formation and promote the formation of smaller ice crystals, leading to good texture and reduced damage to the cellular structure of the frozen products [117]. This can result in improved sensory attributes and improved retention of nutrients in the frozen food. Furthermore, US can enhance the heat transfer rate during freezing by promoting convection and enhancing mass transfer between the product and the surrounding medium [27]. This can result in fast freezing times and uniform temperature distribution within the product, reducing the formation of ice crystals and maintaining the product's quality.

The effectiveness of US-assisted freezing is influenced by various factors, including US intensity, frequency, sample positioning, cooling medium temperature, and flow rate. In a study conducted by Kiani, Sun, and Zhang [64], the heat transfer phenomena was examined using a stationary copper sphere with different intensities and positions. The authors found a direct correlation between US intensity and sphere position with the population of cavitation bubbles and patterns of acoustic streaming. The presence of strong cavitation clouds and acoustic streaming on the surface of the sphere resulted in a high cooling rate. The properties of the cooling medium also play a significant role in heat transfer and ice crystal formation. Kiani, Sun, and Zhang [65] demonstrated that at an US irradiation intensity of 890 W/m2, the cooling medium exhibited high viscosities and low flow rates due to the effects of mixing and cavitation, which is beneficial for freezing applications as it contributes to the controlled and uniform cooling of the material.

However, it is difficult to describe the US-assisted freezing process mathematically. Saclier, Peczalski, and Andrieu [107] proposed a theoretical model to explain ice primary nucleation triggered by US. According to their model, the collapse of cavitation bubbles creates high pressures, which raise the equilibrium freezing temperature of water. This, in turn, increases the level of supercooling and facilitates ice nucleation. They established correlations between operational parameters, such as ultrasonic wave amplitude and supercooling degree, and the number of nuclei formed. Specifically, the number of nuclei produced by a single bubble can be mathematically expressed as follows:

| (10) |

Where is the nucleation rate distribution as a function of liquid pressure and temperature, is the liquid volume surrounding the bubble, and is time.

To describe the relationship between the nucleation rate and the pressure and temperature generated by US, the function can be defined as follows:

| (11) |

Where is the nucleation rate, is the Planck constant, is the perfect gas constant, is the critical free energy at the point of formation of a nucleus of critical size, is the activation energy for the water molecules diffusion across the water/ice interface, is the molar weight of the solution, and is the density of the solution. Considering the high pressure produced during the collapse of cavitation bubble, can be expressed as:

| (12) |

Where is the latent heat of melting, is the crystal-solution interface energy, is the solidification temperature, is the processing temperature, is the solid phase density, and is the liquid pressure.

According to the equations, a better control of both nucleation and crystal growth can be done and the energy required to achieve target supersaturation conditions (temperature and pressure) can be reduced along with better control of the characteristics of crystallized material. US technology has found diverse applications in the preservation and processing of various foodstuffs and pharmaceuticalsBaillon et al. [5]. In particular, US freezing has proven effective for high-value food products and pharmaceuticals due to its precise control and rapid freezing capabilities. Additionally, US has been successfully utilized in the crystallization of food products, such as triglyceride oils (including vegetable oils), ice cream, and milk fat [26], [69], [118]. One notable advantage of US in crystallization processes is its ability to prevent the encrustation of crystals on cooling elements, ensuring efficient heat transfer throughout the cooling process. This not only enhances product quality but also contributes to the overall efficiency and reliability of the production process.

5.3. US-assisted drying

Drying is a commonly used to enhance the stability of fresh harvest biomass. However, the quality of biomass can be significantly affected by the drying process, particularly when high temperatures or long drying times are employed [16]. Low-cost methods like solar drying require ample spaces and favourable climate conditions, while other traditional methods, such as hot air drying, though widely used in the industry, are energy-intensive, time-consuming, and involve high temperatures. These factors can potentially compromise the quality of the final products and thus, advanced drying technologies, such as freeze-drying, fluidized bed drying, microwave drying, and spray drying have been developed for specific applications. However, these new methods can often be time- or energy- consuming processes that could be improved, and US emerges as a potentially new drying alternative due to several mechanisms: (i) Cavitation induces acoustic streaming and microstreaming in the drying medium or material being dried. These streaming effects disrupt the boundary layer of moisture near the surface, reducing the stagnant air or vapour film thickness, promoting a fast and efficient mass transfer of moisture from the material to the surrounding drying medium, resulting in accelerated drying rates Zhu et al. [156], Zhu et al. [157]; (ii) US is able to increase the surface area of the target material as the cavitation generates bubbles on the surface of the material or within the drying medium. These bubbles collapse violently, leading to the generation of localized turbulences and small droplets or microbubbles. The increased surface area due to these microbubbles enhances the contact between the drying medium and the material, facilitating more efficient moisture evaporation [151]; (iii) Ultrasonic waves can disrupt the diffusion pathways within the material being dried [13]. The mechanical vibrations induced by US can help to break down the structural barriers, such as cell walls or barriers between moisture-containing regions, allowing moisture to move more freely and accelerating the drying; (iv) Ultrasonic waves can generate localized heating due to the absorption of sound energy by the material. This localized heating can contribute to faster moisture evaporation and drying Zhu et al. [154], Zhu et al. [155].