Abstract

Advances in genomic testing have been pivotal in moving childhood cancer care forward, with genomic testing now a standard diagnostic tool for many children, adolescents, and young adults with cancer. Beyond oncology, the role of genomic testing in pediatric research and clinical care is growing, including for children with developmental differences, cardiac abnormalities, and epilepsy. Despite more standard use in their patients, pediatricians have limited guidance on how to communicate this complex information or how to engage parents in decisions related to precision medicine. Drawing from empirical work in pediatric informed consent and existing models of shared decision-making, we use pediatric precision cancer medicine as a case study to propose a conceptual framework to approach communication and decision-making about genomic testing in pediatrics. The framework relies on identifying the type of genomic testing, its intended role, and its anticipated implications to inform the scope of information delivered and the parents’ role in decision-making (leading to shared decision-making along a continuum from clinician-guided to parent-guided). This type of framework rests on practices known to be standard in other complex decision-making but also integrates unique features of genomic testing and precision medicine. With the increasing prominence of genomics and precision medicine in pediatrics, with our communication and decision-making framework, we aim to guide clinicians to better support their pediatric patients and their parents in making informed, goal-concordant decisions throughout their care trajectory.

Pediatric Oncology: A Case Study for Genomic Testing and Pediatric Precision Medicine

Significant technological advances have ushered in the era of precision medicine in pediatric oncology, with genetic and genomic testing becoming ever more common for children with cancer.1–3 The range of this testing in children with cancer spans from a targeted test that identifies a single genetic variant in a tumor to next-generation sequencing used to sequence the child’s whole genome (Table 1 reveals a few examples).4–6 As the technology of genomic testing has advanced, its routine use for diagnosis, risk stratification, and the modification of treatment of childhood cancers has increased.7,8 Childhood cancer research now more frequently incorporates this testing into clinical trials, in which many children with cancer enroll to receive upfront treatment.9 This is not unique to pediatrics because such testing is also becoming increasingly incorporated into standard practice in adult oncology.10,11 Despite the more standard incorporation of genomic testing into pediatric oncology clinical care, unlike in adult medicine, there is limited guidance for pediatric oncologists on how to communicate this complex information or how to engage parents in decisions related to precision medicine.12 Likewise, the prominence of genomic testing in other areas of pediatric medicine has grown, including the care of children with developmental differences, cardiac abnormalities, and epilepsy.13–15 Here, using pediatric precision cancer medicine as a case study, we will draw from 2 existing models for ethics and communication to inform a communication and decision-making framework for genomic testing in pediatrics.

TABLE 1.

Examples of Genetic and Genomic Tests in Pediatric Oncology

| Genetic or Genomic Test | Example Clinical Scenario | Intended Clinical Utility | Role in Clinical Practicea | Potential for Immediate Clinical Impact | Potential for Incidental or Secondary Finding | Suggested Languageb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FISH for specific gene rearrangement | Biopsy in a child with a new diagnosis of a solid tumor (eg, EWSR1 rearrangement in suspected Ewing sarcoma4) | Clarification/ confirmation of diagnosis | Standard of care | Likely | Unlikely | • “…this test is one we always send for children with this kind of tumor...” |

| • “…we look at the tumor cells for specific changes in a gene…” | ||||||

| • “…this will help confirm the diagnosis we suspect…” | ||||||

| FISH for panel of multiple gene rearrangements | Bone marrow aspirate in a patient with new diagnosis of leukemia (eg, BCR-ABL, ETV6-RUNX1, etc. in B-ALL5) | Risk stratification | Standard of care | Likely | Unlikely | • “…we send this test for all children who we think might have leukemia…” |

| • “…trying to identify particular gene changes seen in some leukemias…” | ||||||

| • “…this might change the treatment for your child’s leukemia…” | ||||||

| Cancer gene panel (DNA sequencing) | Biopsy of a child with relapse of a solid tumor | Identification of potential targeted treatment | Emerging standard of care | Likely | Possible | • “…we would recommend this test…” |

| • “…hope to identify if genetic changes seen in some cancers are present in your child’s tumor….” | ||||||

| • “…this might identify a targeted treatment for you…” | ||||||

| • “…could reveal a change that is not only in the tumor, but also in all of the cells in your child’s body (the healthy cells and the tumor cells)….” | ||||||

| • “…might learn about your child’s or other family members’ risk for developing certain cancers…” | ||||||

| Whole genome sequencing | Paired blood and tumor samples in a child with a new cancer diagnosis | Identification of potential underlying cancer predisposition | Becoming more common, although not yet standard of care at most institutions | Unlikely | Likely | • “…we have the option of sending this test if it is something you would like…” |

| • “…we would send a sample of both the tumor and your child’s own healthy cells to look for gene changes…” | ||||||

| • “…it could tell us health information about your child or other family members…” | ||||||

| • “…we might learn information that has no effect on your child, information that we don’t fully understand, or not learn any new information at all…” |

B-ALL, B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia.

Individual practices at institutions vary. In general, some genomic tests are performed as standard of care, whereas others are considered novel or experimental, although all types of genomic testing are becoming increasingly common.

These example phrases are intended to demonstrate possible ways, as part of a larger discussion, to clarify the parent’s role in a given decision and the purpose of the testing being discussed.

Notably, particularly in genomics, what is considered “standard of care” is constantly evolving. Regardless of whether sending a genomic test is “standard of care” or requires a “decision” to send, the engagement of parents in their child’s care is critical. Because of this, we consider communication and decision-making along 1 continuum. Additionally, whether genetic tests and information are “exceptional” has been extensively debated in the literature.16,17 Clinicians may hold differing views on whether or how this testing differs from other evaluations. These views, along with rapidly shifting technologies and advancements, may impact each clinician’s comfort with or approach to the communication of this information. For this reason, it is critical to address this communication topic in pediatrics. Of note, as we describe this communication throughout this paper, the term parent is intended to refer broadly to a pediatric patient’s parent(s) or other legal guardian(s), as the case may be. Similarly, we will use the term genomic testing to refer to the spectrum of available genetic and genomic tests, although subtle differences exist among these.

Existing Ethical Guidelines for Genomic Testing in Pediatrics

Previously published recommendations for genomic testing in children have focused on the interests of the child undergoing testing. Indeed, in a 2013 policy statement (reaffirmed in 2018), the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) recommend that decisions about whether to offer genetic testing or screening of a child should be driven by what is in the best interest of that child.18,19 Yet, identifying an individual child’s best interest can be complex, as highlighted by the ethical, legal, and psychosocial challenges emphasized by the American Society of Human Genetics 2015 Position Statement.20 In some cases, genomic testing results in findings outside the original purpose of testing, including incidental findings (findings that are unavoidable because of the testing methodology, whether anticipated or unanticipated) or secondary findings (findings that are actively sought by a practitioner or laboratory that are not the primary target).21 In considering whether a genomic test is in the best interest of the child, these potential outcomes of the test might be considered a benefit by some parents (ie, the identification of a variant that informs future screening recommendations for the child) or a harm by other parents (ie, the identification of a variant of unknown significance that results in confusion or anxiety). When the child has symptoms of a genetic condition and a genetic test is ordered for diagnostic purposes, communication with the parent can be modeled after communication about other medical diagnostic evaluations;18 the clinician should inform parents about the potential benefits and potential harms of the diagnostic test.

Promoting a child’s best interests is commonly also the basis for recommendations about predictive genetic testing. Initially, in 2013, the ACMG recommended that testing laboratories and ordering clinicians report particular clinical genomic results to parents, even if secondary, with this list of findings warranting disclosure expansion in subsequent years.22 This stance was controversial, however, with many pediatric ethicists arguing that these findings should not be routinely reported back to families given the concern of the possible harms of disclosing undesired information to the child and their family.23 Likewise, to protect a child’s “right to an open future,” testing specifically for adult-onset conditions in children has generally been discouraged, at least in cases in which no childhood intervention will alter the potential development of disease or result in earlier treatment.19 In these cases, it has been considered preferable to delay testing until the adolescent can provide assent or, even better, until they reach the age of majority and can provide consent for themself.24 These recommendations can be more challenging to apply in children with acute illnesses, like cancer, thus requiring nuanced guidance.

Communication in Pediatrics

To approach a communication and decision-making process for genomic testing, we first considered communication norms in the care of pediatric patients. When a clinician plans to order a diagnostic test on a child, they must seek informed consent (sometimes referred to as informed permission) from the parent.25 In some cases, the informed consent is simple (ie, informing the parent that a nasal swab will be performed to evaluate for the presence of a respiratory virus), and in other cases is more nuanced (ie, obtaining parental permission through discussing the risks and benefits of a voiding cystourethrogram in a child with a history of a urinary tract infection). Of note, in any case in which consent is elicited from a parent, there is the possibility, albeit relatively uncommon, of parental refusal, although the nuances of approaching these situations are beyond the scope of this paper.26,27

Importantly, whether the informed consent process is simple or nuanced, it should include communication that facilitates the parent’s understanding of the planned test (including its potential benefits, harms, implications, etc). This can be particularly challenging to achieve at the time of a new diagnosis of a serious illness, like cancer, in a child, when a parent may experience informational or emotional overload that may limit their ability to comprehend or retain detailed information.28 Given this, clinicians must prioritize clear communication of the critical elements of the planned genomic testing (see “Suggested Language,” Table 1). Similar to communication about other complex issues in pediatrics (cancer and otherwise), repetition and reviewing important concepts at later timepoints can help clarify details and ensure parental understanding.29,30 Even with these efforts, truly informed consent is not always achieved and remains largely aspirational. The limits of informed consent in achieving parental understanding have been recognized in “simple” issues, such as understanding randomization in a clinical trial,31 and in more nuanced situations, like understanding the potential direct impact of enrollment in a tumor sequencing study for a patient’s high-risk cancer.32 Further work is needed to continue to strive for the ethical ideal of achieving true informed consent (and full understanding) in all such situations.

One way to support this in pediatric precision medicine is through the involvement of genetic counselors and pediatric geneticists who are trained specifically in educating families. However, the early integration of these specialized clinicians into pediatric care is limited by several factors, including the often time-sensitive nature of the testing and limited availability given a relatively small number of genetics professionals.33,34 Of note, although in this paper, we only refer to communication with the parent, every reasonable effort should be made to involve the patient in these processes in a developmentally appropriate fashion.25,35 How to optimally engage children or adolescents along with their parents is beyond the scope of this paper, so references to “parents” can be read as referring to “parents and pediatric patients.”

To further inform the processes around communication and decision-making specific to genomic testing in pediatrics, we draw from Opel et al’s framework for shared decision-making (SDM) in pediatrics (Fig 1), which was initially published in this journal.36,37 Although SDM is generally accepted as the preferred clinical practice model in adult health care, its application in pediatrics has been less clearly delineated. Opel et al posit that in a clinical scenario in which there is >1 medically reasonable option, the clinician should determine the medical benefit–burden ratio of one option compared with others to determine if the decision-making should be more clinician-guided or parent-guided. Even in scenarios that are not traditionally viewed as “decisions” (ie, are obligatory regardless of parental preferences), such as the treatment of a severe asthma exacerbation in a child, this model guides us in how best to involve the parent in the discussion about the child’s treatment (ie, through education about the standard treatment with a bronchodilator and oral steroids) and what leeway there is or is not for a parent’s preferences to impact the treatment plan (ie, incorporating the parental preference of delivering the bronchodilator by nebulizer or inhaler).36,37 By framing communication about a particular test or intervention in a way that supports parental input when appropriate, we can further support the parent’s role as an advocate and decision-maker for their child.

FIGURE 1.

Four-step framework for SDM in pediatrics. This algorithm can be used for any discrete clinical decision. The first 3 steps each pose a question to the physician, and Steps 3 and 4 direct the type and version of SDM to use for the particular clinical decision. Adapted from “A 4-Step Framework for Shared Decision-making in Pediatrics” by D. Opel.36

The Scope of the Genomic Test Should Guide the SDM Process

Drawing from the previous work regarding SDM, we can consider relevant standards specific to communication about genomic testing in pediatrics. The type of genomic testing, including its intended role and anticipated implications, should inform the parent’s role in decision-making (Fig 2). We developed this model with our oncology case study in mind, but it can be applied more generally to genomic testing across pediatric care. At one end of the continuum is what we similarly refer to as clinician-guided SDM. This is appropriate when (1) the purpose of the test is to identify findings immediately relevant to the child’s clinical care, and (2) the likelihood of secondary or incidental findings is low. For instance, returning to pediatric oncology as our case study, when a child presents with a new diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the standard of care includes the clinician informing the child’s parent of the planned diagnostic workup, including a diagnostic bone marrow procedure. One test routinely performed on the bone marrow specimen is a standard fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) panel to evaluate for any of several genomic variants in the leukemia that, if present, would inform the risk stratification of the cancer (see Table 1 and Table 2 for several clinical scenarios highlighting different potential uses of genomic testing in such a setting).5 This panel is important in determining the child’s risk stratification and treatment plan, and the likelihood of uncovering a secondary or incidental finding is low given the limited panel. With this type of routine diagnostic testing, the decision-making is strongly clinician-guided, with limited opportunities for incorporating parent preferences. This can be compared with a scenario in general pediatrics of a child who presents with dysuria whose urinalysis indicates a likely infection. The pediatrician would inform the parent that given the concern for urinary tract infection, the child’s urine specimen will be sent for culture. The results may immediately impact the treatment regimen and are unlikely to present secondary or incidental findings. Likewise, once again returning to our case study, in a child with signs of leukemia, the clinician should inform the parent that the genomic test will be sent as part of the standard diagnostic work-up on their child’s bone marrow specimen.

FIGURE 2.

Framework for SDM in pediatric precision medicine. The type of genomic testing should inform the scope of the parent’s role in decision-making. As explained in greater detail in the text, testing that immediately impacts the child’s treatment and has a limited possibility of secondary or incidental findings is most amenable to clinician-guided SDM, whereas those without any impact on the child’s treatment but with a high likelihood of secondary or incidental findings are a better fit for parent-guided SDM (with many decisions lying somewhere between those 2 extremes).

TABLE 2.

Clinical Scenarios Along the SDM Spectrum in Pediatric Genomic Testing

| Clinician-Guided SDM | Blended (Clinician- and Parent-Guided) SDM | Parent-Guided SDM | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oncology | Neurology | Pulmonary | Oncology | Neurology | Pulmonary | Oncology | Neurology | Pulmonary | |

| Clinical scenario | 3-y-old with new diagnosis of B-ALL | 2-mo-old with profound hypotonia, suspected spinal muscular atrophy | 2-mo-old with a positive newborn screen for cystic fibrosis and positive sweat test | 7-y-old with suspected relapse of rhabdomyo-sarcoma | 3-y-old with new epilepsy and normal brain MRI | 4-y-old with concern for primary ciliary dyskinesia | 3-y-old with new brain tumor | 7-y-old with severe intellectual disability | 2-mo-old child with unexplained respiratory failure and dysmorphic facies |

| Genetic/ genomic test |

Leukemia FISH panel on marrow sample | Single gene testing for SMN1 | Single gene testing for CFTR | Multigene cancer panel on tumor biopsy | Multigene epilepsy panel | Primary ciliary dyskinesia panel | Whole exome sequencing on paired tumor/ normal samples | Whole exome sequencing | Whole exome sequencing |

| Potential clinical utility | Risk stratify, optimize upfront treatment regimen | Initiate time-sensitive treatment | Initiate time-sensitive treatment | Identify targeted treatment | Identify targeted treatment (ie, optimal antiseizure medication) | Identify targeted therapies | Identify cancer predisposition syndrome, unlikely to impact current treatment | Identify etiology of intellectual disability, unlikely to impact current treatment | Identify etiology of respiratory failure, unlikely to impact current treatment |

| Suggested language to discuss testing with parenta | • “…we send this test for all children who we think might have this diagnosis…” | • “…we would recommend this test…” | • “…we have the option of sending this test if it is something you would like…” | ||||||

| • “…trying to identify particular a particular gene change (or changes) seen in this diagnosis…” | • “…hope to identify if genetic changes seen in other children with this diagnosis are present for your child….” | • “…we would send a sample of your child’s own healthy cells to look for gene changes…” | |||||||

| • “…this testing is time-sensitive…” | • “…this might identify a targeted therapy for your child…” | • “…it could tell us health information about your child or other family members…” | |||||||

| • “…this might change the treatment for your child…” | • “…could reveal a change that is in all of the cells in your child’s body…” | • “…we might learn information that has no effect on your child, information that we don’t fully understand, or not learn any new information at all…” | |||||||

| • “…might learn about your child’s or other family members’ risk for developing certain illnesses…” | • “…because the results are unlikely to change your child’s current care for this diagnosis, we recommend taking time to fully consider whether you are interested in this…” | ||||||||

B-ALL, B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia.

These example phrases are intended to demonstrate possible ways, as part of a larger discussion, to clarify the parent’s role in a given decision and the purpose of the testing being discussed.

When the converse is true, when (1) the testing is not likely to immediately impact the child’s treatment plan, or (2) there is potential for an incidental or a secondary finding, in which case the determination of whether to send the test should instead be more strongly guided by the parent’s preferences or values, rather than the clinician. We call this parent-guided SDM. For instance, an oncologist might consider sending paired somatic and germline genomic sequencing at the time of a child’s cancer diagnosis (Tables 1 and 2). The range of potential findings that could impact not only the child but also their family is significant, including learning about an underlying cancer predisposition syndrome, an incidentally found predisposition for an adult-onset condition, or a variant of unknown significance.38 Some patients and their families consider results like these to be valuable, citing “knowledge as power,” with results potentially informing screening recommendations for family members.39 Others, although less common, cite concerns about learning this information due to concerns about increasing anxiety during an already overwhelming time for the family or worries about the impact on family members’ insurance.32,40 Especially when the immediate clinical utility is limited, a decision to send a genomic test with this complex scope of possible results warrants significant parental input. For these reasons, it may be also reasonable to delay complex testing (eg, tests with limited immediate clinical relevance or the possibility of incidental or secondary findings) to allow for a more comprehensive SDM process.41 Because some genomic tests are not particularly time-sensitive, a parent who declines whole genome sequencing for their child at one timepoint may later decide to pursue the test. Of note, although somewhat controversial, in pediatrics, the ACMG recommends that, in general, parents should be permitted to opt out of secondary findings.23,42,43 Particularly for those tests with a high likelihood of secondary or incidental findings, a key part of the communication is to ensure that parents know there is an opt-out option available and the risks and benefits of opting out or not opting out (see “Suggested Language” in Table 1). This preference to opt out of secondary results may also change for a parent over time. Given this, it may be helpful for clinicians to readdress this question, as well as the decision on whether to pursue testing, at later timepoints in the child’s care, particularly if they feel that a parent’s initial choice may have been limited by their understanding early in their child’s illness. Incorporating parental input throughout the child’s care respects their role as decision-makers for their child and, in turn, respects the child. This could be seen, for example, as analogous to other strongly preference-sensitive decisions regarding which, parents generally are given significant authority in pediatric care, such as those related to their child’s end-of-life care.44

Falling between these two on the spectrum of parental involvement, are cases in which the results of the test might have an immediate clinical impact but also carry at least some potential for a secondary or incidental finding. One example to which this applies is tumor sequencing using a cancer gene panel (Table 2 describes several scenarios, including this one, in which this framework might be applied). Testing in this way could identify new treatment possibilities but also may uncover a secondary germline finding (a variant present both in the tumor and in the child’s healthy cells) that identifies a cancer predisposition syndrome. For example, if a child experiences a relapse of a solid tumor, their clinician might recommend testing the tumor for any genomic alterations that might suggest a targeted treatment for the child. The cancer panel for this child’s tumor could reveal a germline mutation, such as TP53, in the child. There is no medication to target TP53 in the tumor, and this alteration, if proven to be in the germline, would impart a higher risk of the child developing several types of cancer, including adult-onset cancers. In addition, if found to be hereditary, it would also reveal health information about family members.45 This testing could also reveal a variant of unknown significance. Even when a test is ordered with a particular clinical goal, such as the identification of a targeted treatment, the risk of learning secondary or incidental results should be clearly communicated during the SDM process.

Similar tensions arise in other areas of pediatric care, such as the evaluation of a child with chronic headaches with atypical features. A pediatrician might recommend an MRI of the brain to evaluate for potential etiologies of the headache, the findings of which may direct treatment recommendations. This imaging has the possibility of incidental findings, including both those with clinical relevance and those with unknown significance. Given the anticipated potential clinical impact, the clinician should present this information among the other recommendations for diagnostic workup, rather than as a “choice” whether to order. After describing these potential risks, if the parent expresses concern, they may more thoroughly explore reasonable alternatives (ie, the risks and benefits of not obtaining this imaging). When feasible, particularly in situations like this and others with lower clinical urgency, parents may, as introduced earlier, also benefit from additional time, the repetition of key information, or a discussion with additional team members to process this complex information in decision-making. See Table 2 for additional examples of genomic testing across the landscape of pediatrics in which this framework might be applied, along with where on the SDM spectrum each falls, and suggested language that could be used when talking to a parent about the testing.

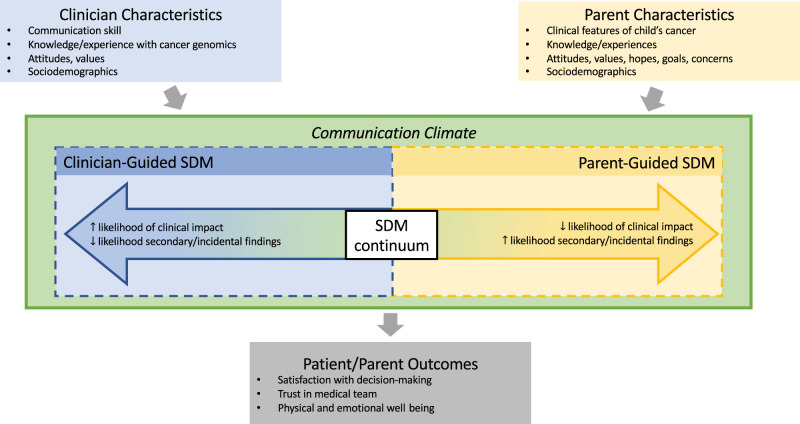

Using SDM to Move From Precision Medicine to Precision Information

Although decisions about genomic testing, both in pediatric oncology specifically and more generally across pediatrics, are important, they do not exist in a vacuum. In practice, decisions and communication practices around those decisions are informed by the stakeholders involved in the SDM process. Kane et al’s conceptual model of the SDM communication process (initially developed in the setting of medical oncology) highlights the importance of considering situational features, such as characteristics of the patient and clinician, and their impact on the communication process.46 Just as in the Kane model, characteristics of the pediatric clinician, such as their previous experiences with genomic-informed therapies, might impact their style of communication about these tests with parents.40,47,48 Likewise, characteristics of the parent, such as their hopes, goals, and values, can affect their own perspectives and, in turn, the communication climate.32,39 Both of these factors can, in turn, influence the parent’s experience of this communication and decision-making process, leading to downstream impacts, such as their satisfaction with decision-making or their trust in the medical team. We have developed a conceptual model for the SDM process in the era of precision medicine in pediatrics, bringing together the work of Opel et al and Kane et al (Fig 3).36,37,46 This model centers around a given plan for, or decision regarding, genomic testing, highlighting that such decisions take place in a communication climate informed by the characteristics and perspectives of the clinician and parent engaged in the SDM process.32,39,40,47,48 An appreciation of the complexity of these decisions and the complexity of those taking part in them will help improve communication and optimize outcomes as we move from the simple personalization of medicine to the more challenging personalization of information.

FIGURE 3.

Conceptual model of the SDM process in pediatric precision medicine. Decisions regarding genomic testing take place in a communication climate informed by the characteristics and perspectives of the clinician and parent engaged in the SDM process.

With our conceptual model, we have necessarily simplified several features of a nuanced and complex process. First, we describe a 2-way process involving the clinician and the patient’s parent. The patient is a critical stakeholder in the process, particularly when in the adolescent and young adult age range. Likewise, other medical professionals, including nurses, advanced practice providers, genetic counselors, geneticists, social workers, and child life specialists, may each impact a parent’s experience of receiving information or making care decisions. In addition, the conceptual model is unable to fully represent the level of uncertainty often present when a genomic test is sent. For example, even when the purpose of a genomic test is to identify a possible molecularly targeted (ie, genomically informed) therapy, there can remain significant uncertainty in the success of such a treatment, with pediatric clinicians often relying on abstractions from adult data. Finally, the factors influencing the communication climate identified in the conceptual model are also necessarily simplified. “Sociodemographic factors,” for instance, refers to a broad range of inequities in patient experiences and outcomes in both pediatrics and genomic medicine. This includes limited representation of minoritized groups in genomics-related research or limited access to genomic testing and therapies.49–51 Without particular attention to further research and intervention efforts, we risk widening these inequities further. Even with the necessary simplifications in our conceptual model, it serves as a starting point for approaching communication and decision-making in the complex and evolving precision medicine era across all areas of pediatric medicine. Further efforts are needed to develop communication resources for pediatricians and patients and their parents.

Conclusions

Novel technologies will continue to advance, and the ethical challenges seen in pediatric precision cancer medicine are likely to arise more frequently in all areas of pediatric medicine. Genomic sequencing, for example, is becoming more common in the newborn setting (both for sick and healthy newborns), in pediatric epilepsy care, and in the care of children with congenital heart disease.13,14,52 It is likely to have a larger role in many other areas of both general and subspecialty pediatrics in the near future. As medical care moves toward truly personalized care for each patient, we have the opportunity to extend this concept beyond laboratory testing or targeted medications. Pediatric clinicians can also personalize their interactions with patients and their families to center information that is relevant to the individual experience, which some authors have referred to as “precision communication.”53 By centering the role of SDM in complex decisions like these, we aim to guide clinicians in better supporting parents in making informed, goal-concordant decisions both in our exemplary case study of pediatric oncology, as well as in other complex situations that arise in pediatric care.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Doug Opel, MD, MPH, for his expertise and comments on early concepts presented in this manuscript.

Glossary

- ACMG

American College of Medical Genetics

- FISH

fluorescence in situ hybridization

- SDM

shared decision-making

Footnotes

Dr Lee conceptualized the review, drafted the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Rosenberg critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Marron conceptualized the review and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FUNDING: Funded, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (T32-HL125195 to BML) and Rally Foundation for Childhood Cancer Research (BML). The authors have been supported for other, non-related work by the NIH (ARR and JMM), American Cancer Society (ARR), Arthur Vining Davis Foundations (ARR), Cambia Health Solutions (ARR), Conquer Cancer Foundation of ASCO (ARR and JMM), CureSearch for Children’s Cancer (ARR), and the Palliative Care Research Cooperative Group (JMM). The opinions herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the funders.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES: Dr Marron has received honoraria from Partner Therapeutics for serving on their Ethics Advisory Board and from Sanofi-Genzyme Global Oncology for delivering a lecture to their employees and holds stock in ROMTech. None of these entities has had a role in this work. Drs Lee and Rosenberg have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1. Forrest SJ, Geoerger B, Janeway KA. Precision medicine in pediatric oncology. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2018;30(1):17–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mody RJ, Prensner JR, Everett J, et al. Precision medicine in pediatric oncology: lessons learned and next steps. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(3):10.1002/pbc.26288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ahmed AA, Vundamati DS, Farooqi MS, Guest E. Precision medicine in pediatric cancer: current applications and future prospects. High Throughput. 2018;7(4):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Trautmann M, Hartmann W. Molecular approaches to diagnosis in Ewing sarcoma: fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Methods Mol Biol. 2021;2226:65–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hiemenz MC, Oberley MJ, Doan A, et al. A multimodal genomics approach to diagnostic evaluation of pediatric hematologic malignancies. Cancer Genet. 2021;254–255:25–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Newman S, Nakitandwe J, Kesserwan CA, et al. Genomes for kids: the scope of pathogenic mutations in pediatric cancer revealed by comprehensive DNA and RNA sequencing. Cancer Discov. 2021;11(12):3008–3027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oberg JA, Glade Bender JL, Sulis ML, et al. Implementation of next generation sequencing into pediatric hematology-oncology practice: moving beyond actionable alterations. Genome Med. 2016;8(1):133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Cancer Institute. About the CCDI Molecular Characterization Initiative. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/research/areas/childhood/childhood-cancer-data-initiative/molecular-characterization. Accessed April 29, 2022

- 9. Childhood Cancer Data Initiative. About the Childhood Cancer Data Initiative Molecular Characterization Initiative. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/research/areas/childhood/childhood-cancer-data-initiative/data-ecosystem/molecular-characterization. Accessed May 8, 2023

- 10. Chakravarty D, Johnson A, Sklar J, et al. Somatic genomic testing in patients with metastatic or advanced cancer: ASCO provisional clinical opinion. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(11):1231–1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Colomer R, Mondejar R, Romero-Laorden N, et al. When should we order a next generation sequencing test in a patient with cancer? EClinicalMedicine. 2020;25:100487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murray AK, McGee RB, Mostafavi RM, et al. Creating a cancer genomics curriculum for pediatric hematology-oncology fellows: a national needs assessment. Cancer Med. 2021;10(6):2026–2034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kikano S, Kannankeril PJ. Precision medicine in pediatric cardiology. Pediatr Ann. 2022;51(10):e390–e395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Graifman JL, Lippa NC, Mulhern MS, et al. Clinical utility of exome sequencing in a pediatric epilepsy cohort. Epilepsia. 2023;64(4):986–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Berg JS, Agrawal PB, Bailey DBJr, et al. Newborn sequencing in genomic medicine and public health. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2):e20162252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Evans JP, Burke W. Genetic exceptionalism. Too much of a good thing? Genet Med. 2008;10(7):500–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Green MJ, Botkin JR. “Genetic exceptionalism” in medicine: clarifying the differences between genetic and nongenetic tests. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(7):571–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bioethics CO; Committee on Bioethics; Committee on Genetics; American College of Medical Genetics; Genomics Social, Ethical, and Legal Issues Committee. Ethical and policy issues in genetic testing and screening of children. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):620–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ross LF, Saal HM, David KL, Anderson RR; American Academy of Pediatrics; American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Technical report: ethical and policy issues in genetic testing and screening of children. Genet Med. 2013;15(3):234–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Botkin JR, Belmont JW, Berg JS, et al. Points to consider: ethical, legal, and psychosocial implications of genetic testing in children and adolescents. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97(1):6–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weiner C. Anticipate and communicate: ethical management of incidental and secondary findings in the clinical, research, and direct-to-consumer contexts (December 2013 report of the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues). Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(6):562–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW, et al. ; American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15(7):565–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Burke W, Antommaria AH, Bennett R, et al. Recommendations for returning genomic incidental findings? We need to talk! Genet Med. 2013;15(11):854–859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ross L. Genetic Testing and Screening of Minors. In: Diekema DS, Mercurio MR, Adam MB, eds. Clinical Ethics in Pediatrics: A Case-Based Textbook. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2011:181–185 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Katz AL, Webb SA; Committee on Bioethics. Informed consent in decision-making in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20161485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Diekema DS. Parental refusals of medical treatment: the harm principle as threshold for state intervention. Theor Med Bioeth. 2004;25(4):243–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ross LF. Better than best (interest standard) in pediatric decision making. J Clin Ethics. 2019;30(3):183–195 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Alahmad G. Informed consent in pediatric oncology: a systematic review of qualitative literature. Cancer Contr. 2018;25(1):1073274818773720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Feraco AM, McCarthy SR, Revette AC, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of the “Day 100 Talk”: an interdisciplinary communication intervention during the first six months of childhood cancer treatment. Cancer. 2021;127(7):1134–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lemmon ME, Donohue PK, Parkinson C, et al. Communication challenges in neonatal encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20161234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kodish E, Eder M, Noll RB, et al. Communication of randomization in childhood leukemia trials. JAMA. 2004;291(4):470–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marron JM, DuBois SG, Glade Bender J, et al. Patient/parent perspectives on genomic tumor profiling of pediatric solid tumors: the Individualized Cancer Therapy (iCat) experience. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(11):1974–1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Raspa M, Moultrie R, Toth D, Haque SN. Barriers and facilitators to genetic service delivery models: scoping review. Interact J Med Res. 2021;10(1):e23523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Abacan M, Alsubaie L, Barlow-Stewart K, et al. The global state of the genetic counseling profession. Eur J Hum Genet. 2019;27(2):183–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Salter EK, Hester DM, Vinarcsik L, et al. Pediatric decision making: consensus recommendations. Pediatrics. 2023;152(3):e2023061832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Opel DJA. A 4-step framework for shared decision-making in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2018;142(Suppl 3):S149–S156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Weiss EM, Clark JD, Heike CL, et al. Gaps in the implementation of shared decision-making: illustrative cases. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20183055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Parsons DW, Roy A, Yang Y, et al. Diagnostic yield of clinical tumor and germline whole-exome sequencing for children with solid tumors. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(5):616–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mandrell BN, Gattuso JS, Pritchard M, et al. Knowledge is power: benefits, risks, hopes, and decision-making reported by parents consenting to next-generation sequencing for children and adolescents with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2021;37(3):151167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Scollon S, Majumder MA, Bergstrom K, et al. Exome sequencing disclosures in pediatric cancer care: patterns of communication among oncologists, genetic counselors, and parents. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(4):680–686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Johnson LM, Sykes AD, Lu Z, et al. Speaking genomics to parents offered germline testing for cancer predisposition: use of a 2-visit consent model. Cancer. 2019;125(14):2455–2464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics News. ACMG updates recommendation on “opt out” for genome sequencing return of results. Available at: https://www.acmg.net/docs/Release_ACMGUpdatesRecommendations_final.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2023

- 43. McCullough LB, Brothers KB, Chung WK, et al. ; Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research (CSER) Consortium Pediatrics Working Group. Professionally responsible disclosure of genomic sequencing results in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2015;136(4):e974–e982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Linebarger JS, Johnson V, Boss RD, et al. ; Section on Hospice and Palliative Medicine. Guidance for pediatric end-of-life care. Pediatrics. 2022;149(5):e2022057011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kratz CP, Achatz MI, Brugières L, et al. Cancer screening recommendations for individuals with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(11):e38–e45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kane HL, Halpern MT, Squiers LB, et al. Implementing and evaluating shared decision making in oncology practice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(6):377–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Johnson LM, Valdez JM, Quinn EA, et al. Integrating next-generation sequencing into pediatric oncology practice: an assessment of physician confidence and understanding of clinical genomics. Cancer. 2017;123(12):2352–2359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cohen B, Roth M, Marron JM, et al. Pediatric oncology provider views on performing a biopsy of solid tumors in children with relapsed or refractory disease for the purpose of genomic profiling. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(Suppl 5):990–997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Petrovski S, Goldstein DB. Unequal representation of genetic variation across ancestry groups creates healthcare inequality in the application of precision medicine. Genome Biol. 2016;17(1):157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Atutornu J, Milne R, Costa A, et al. Towards equitable and trustworthy genomics research. EBioMedicine. 2022;76:103879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. West KM, Blacksher E, Burke W. Genomics, health disparities, and missed opportunities for the nation’s research agenda. JAMA. 2017;317(18):1831–1832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kaiser J. Sequencing projects will screen 200,000 newborns for disease. Science. 2022;378(6625):1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Paladino J, Bernacki R. Precision communication-a path forward to improve goals-of-care communication. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(7):940–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]