Abstract

Objectives

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the effect of chitosan and carboxymethyl chitosan (CMCS) on dentin surface morphology and bonding strength after irradiation of Er:YAG laser.

Methods

Eighty-four laser-irradiated dentin samples were randomly distributed into three groups (n = 28/group) according to different surface conditioning process: deionized water for 60s; 1wt% chitosan for 60s; or 1wt% CMCS for 60s. Two specimens from each group were subjected to TEM analysis to confirm the presence of extrafibrillar demineralization on dentin fibrils. Two specimens from each group were subjected to morphological analysis by SEM. Seventy-two specimens (n = 24/group) were prepared, with a composite resin cone adhered to the dentin surface, and were then randomly assigned to one of two aging processes: storage in deionized water for 24 h or a thermocycling stimulation. The shear bond strength of laser-irradiated dentin to the resin composite was determined by a universal testing machine. Data acquired in the shear bond strength test was analyzed by one-way ANOVA with the Tukey honestly significant difference post hoc test and Independent Samples t-test (α = 0.05).

Results

CMCS group presented demineralized zone and a relatively smooth dentin surface morphology. CMCS group had significantly higher SBS value (6.08 ± 2.12) without aging (p < 0.05). After thermal cycling, both chitosan (5.26 ± 2.30) and CMCS group (5.82 ± 1.90) presented higher bonding strength compared to control group (3.19 ± 1.32) (p < 0.05). Chitosan and CMCS group preserved the bonding strength after aging process (p > 0.05).

Conclusions

CMCS has the potential to be applied in conjunction with Er:YAG laser in cavity preparation and resin restoration.

Keywords: Extrafibrillar, Dentin bonding, Er:YAG laser, Chitosan, Carboxymethyl chitosan

Significance

The unsatisfactory bonding efficacy hinders the clinical application of Er:YAG in caries removal and resin restoration. Using CMCS as primer was associated with promising dentin bonding strength and durability after laser ablation.

Introduction

The application of erbium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Er:YAG) laser in dentistry offers an alternative to traditional mechanical instrumentation for cavity preparations. Er:YAG laser offers the advantage of selective removal of carious dentin and being more comfortable for patients due to the minimal pain, pressure, noise, and vibration during the treatment procedure [1, 2]. The issue of bond strength of resin composite to the irradiated dentin has been a controversial and much-disputed subject within the field of cavity preparation by Er:YAG laser. In contrast to earlier findings, however, most recent studies revealed that the application of Er:YAG laser negatively affected the efficacy of dentin bonding [3–6]. The presence of a laser-modified layer and fused collagen may lead to loss of interfibrillar space, which was considered to be the main reason for the decrease of dentin bond strength and restoration failure after cavity preparation by Er:YAG laser [7].

Chitosan is a polycationic polymer derived from alkaline deacetylation of chitin [8]. By means of cross-linking exogenous crosslinking agents with dental collagen fibrils, chitosan is capable of locally enhancing the biostability and biomechanical properties of collagen fibrils [9, 10]. According to the study of Pascale et al. [11], higher modulus of elasticity and lower proteolytic activity were found for dentin treated by chitosan as an irrigant. Currently, there have been a limited number of studies that have investigated the effect of chitosan on dentin after cavity preparation by Er:YAG laser, which reported that chitosan had little impact on dentin morphology, wettability, and chemical composition [12, 13]. In addition, a randomized clinical trial in primary molars conducted by Santos et al. [14] evaluated the effect of chitosan on dentin treatment after selective removal of caries lesions with Er:YAG laser, which demonstrated that the Er:YAG laser reduced the amount of Streptococcus mutans of caries-affected dentin and the chitosan showed an additional antibacterial. However, chitosan treatment had no significant influence on the performed restorations in terms of discoloration and marginal adaptation. One study examined the bonding efficacy of laser-irradiated dentin followed by conditioning with chitosan, the results suggested that chitosan did not promote the micro tensile bond strength immediately after bonding [10]. Carboxymethyl chitosan (CMCS) is a derivative of chitosan that can be obtained by chemical modification of two hydroxyl groups and one amino group on the chitosan chain by carboxymethyl group [15]. Compared with conventional chitosan, CMCS obtains higher water solubility and greater metal ions chelating capacity [15, 16], making it more suitable for clinical application in limited time. Both chitosan and CMCS at high molecular weight (> 40 kDa) are reported to be capable of removing extrafibrillar minerals of dentin matrix while preserving intrafibrillar minerals, referred to as extrafibrillar demineralization [16, 17]. The realization of extrafibrillar demineralization was associated with greater bonding effectiveness as it could reinforce the collagen scaffold [18], prevent the exposure of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in dentin collagen matrix [19], and theoretically enable the application of dry-bonding strategy in clinical practice [16, 17].

The potential use of CMCS to apply in conjunction with Er:YAG laser in caries removal and resin restoration is yet to be assessed. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the effect of the application of chitosan and CMCS on extrafibrillar demineralization of dentin collagen matrix, morphology of dentin surface, as well as bonding strength and durability after irradiation of Er:YAG laser.

Materials and methods

Teeth selection and sample preparation

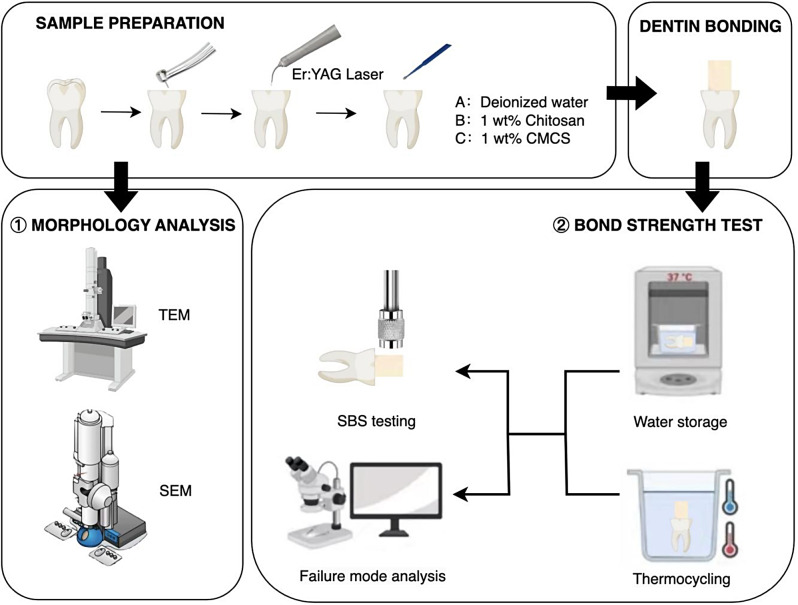

The schematic diagram of the experimental design is shown in Fig. 1.The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board and ethics committee of the institution. Eighty-four non-carious human molars were collected and stored in saline at room temperature and used within three months. A flat mid-coronal dentin surface was exposed by removing the occlusal enamel using bur at high-speed with water spray under a stereomicroscope at ×10 magnification. The experimental groups were classified based on reagents as follows:

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram showing the experimental design

Control group: Deionized water for 60s after laser ablation.

Chitosan group: 1wt% chitosan for 60s after laser ablation.

CMCS group: 1wt% CMCS for 60s after laser ablation.

Er:YAG laser irradiation

Following sample preparation, the occlusal dentin surfaces of all specimens were irradiated with an Er:YAG laser device (LightWalker DT, Fotona, Ljubljana, Slovenia) in medium-short pulse (MSP) mode. The procedure was performed using a handpiece (R14, Fotona, Ljubljana, Slovenia) at non-contact mode with focal distance of 7 mm, pulse energy of 250 mJ output, pulse repetition rate of 4 Hz, an output beam diameter of 0.9 mm, an energy density of 39 J/cm2 and under water spray rate (6mL/min) [13].

Chitosan and CMCS preparation

1 wt% chitosan (pH = 5.2) was prepared by dissolving 0.1 g of chitosan powder (MW: 150–310 KDa, 75–85% deacetylated; Millipore Sigma) in 0.2 wt% acetic acid. 1 wt% CMCS (pH = 6.7) was prepared by dissolving 0.1 g of CMCS powder (MW: 150–200KDa; Yingxin Lab, Shanghai, China) in 10 mL deionized water. Chitosan and CMCS powder were stored at 4℃ and mixed with solvent immediately before use. For dentin surface conditioning, 1 ml liquid conditioners were liberally applied to the dentin surface and agitated with a microbrush for 60 s, then rinsed with deionized water for 15 s [16].

Transmission electron microscope analysis

A total of six specimens (n = 2/group) were subjected to transmission electron microscope (TEM) analysis to visualize extrafibrillar demineralization of dentin fibrils. The specimens were cut into 1 × 2 × 2 mm dentin blocks and the irradiated dentin surface was conditioned with deionized water, chitosan or CMCS. The samples were then rinsed with sterile water. For TEM observation, six blocks were fixed with 2.5wt% glutaraldehyde solution at 4 °C for 24 h, rinsed with phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH = 7) and postfixed with 1 wt% osmic acid for 2 h. After rinsing with phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH = 7), the blocks were dehydrated in an ascending ethanol series from 30wt%(15 min), 50wt%(15 min), 70wt%(15 min) and 80wt%(15 min), and in an ascending acetone series from 90 wt%(15 min) and 95 wt%(15 min). Each specimen was sectioned into a 100-nm-thick dentin disk and immersed in epoxy resin. Six unstained disks were observed with a transmission electron microscope (Hitachi JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at 80 keV.

Scanning electron microscopy analysis

Six specimens (n = 2/group) were immersed in deionized water for an ultrasonic bath for 5 min. Specimens were immersed in glutaraldehyde solution (2.5%) (Leagene, Beijing, China) for 12 h and dehydrated in an ascending ethanol series from 50% (20 min), 75% (20 min), 95% (30 min) and 100% (60 min). Specimens then were metalized with a fine gold overlay (MSP-1 S Magnetron Sputter, IXRF, Texas, America) and submitted to morphological analysis by scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Hitachi S-3400 N II, Tokyo, Japan) at ×1000 and ×3000 magnification.

Bonding procedure

Seventy-two specimens (n = 24/group) were bonded using self-etch adhesive system Single Bond Universal (3 M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The adhesive system was applied to the dentin surface for 20 s, gently air-dried for 5 s, and light-cured for 10 s with a light-curing unit (Elipar S10, 3 M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) operating at 1200 mW/cm2 with standard curing mode, which was checked by a digital radiometer (TREE, model TR-P004, China). A customized metal mold was fabricated for the bonding procedure, where a circular cavity with a diameter of 5 mm and depth of 3 cm was made in the center of this mold. The mold was placed within the center of the coronal dentin surface and the bonding area was 19.625 mm2. Composite resin Z-350 (Filtek Z350, 3 M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) was packed into the cavity in stages, with each increment not exceeding 1 mm in thickness. The composite resin cone was vertically light-cured for 20 s at a distance of 1 mm from the resin surface in each increment. The mold was then gently removed, leaving resin composite cones bonded to the dentin specimens, and the samples were light-cured again for 20 s.

Shear bond strength test

After dentin bonding procedure as described above, twenty-four bonded specimens from each group were randomly assigned to one of the aging processes: storage in deionized water for 24 h or a thermocycling stimulation (5 ◦C followed by 55 ◦C for 1 min each, for 12,000 cycles). A universal testing machine (CMT6104, MTS, USA) was used to determine the shear bond strength of the thirty-six specimens. Shear forces were applied at the bonded interface by a 5 mm-width metal loading head at a steady speed of 0.5 mm/min until fracture occurred. The force at failure (N) was measured to compute the bond strength in MPa.

Failure mode observation

To classify the failure mode, the fractured specimens were examined under a stereomicroscope at ×40 magnification. The failure mode could be divided into adhesive (no resin composite was seen on dentin surface), cohesive (failure within dentin or resin composite material), and mixed (part of resin composite was seen retained on dentin surface).

Statistical analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test confirmed the normality of data distribution. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s multiple-comparison tests were applied to compare the bonding efficacy among different groups. Data acquired from specimens treated with the same conditioner were analyzed by independent samples t-test to compare the bonding strength with or without thermal cycling. Statistical tests were set at a significance level of 5% and data were analyzed by SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., v20, Chicago, IL).

Results

Transmission electron microscope observation

Demineralization of dentin treated by deionized water, chitosan, and CMCS for 60s after irradiation with Er:YAG laser was observed by transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 2A-F). A laser-modified superficial denatured layer with crack, fissures and voids could be observed in the control group and chitosan group (Fig. 2A-D), while organic matrix of CMCS group was mostly intact (Fig. 2E-F). No demineralized zone on dentin surface was observed in control group and chitosan group (Fig. 2A-D). By contrast, CMCS group presented an inhomogeneous partially demineralized zone. The presence of interfibrillar gaps and intrafibrillar apatite crystallites were also illustrated at high magnification. (Fig. 2E-F).

Fig. 2.

Transmission electron microscopy observation of unstained laser-ablated dentin surface conditioned with deionized water,1 wt% chitosan, and 1wt% CMCS each for 60s. Left column: low magnification (×3.0k). Right column: high magnification (×40.0k). R, epoxy resin; D, mineralized dentin. Control group (A&B): No demineralized zone on dentin surface was observed. Chitosan group (C&D): 1wt% chitosan conditioning did not create a demineralized zone. CMCS group (E&F): Collagen fibrils with intrafibrillar apatite (open arrowheads) were presented within the zone of partially demineralized dentin. Partially demineralized zone (between open arrows) can be seen on the surface of the mineralized dentin

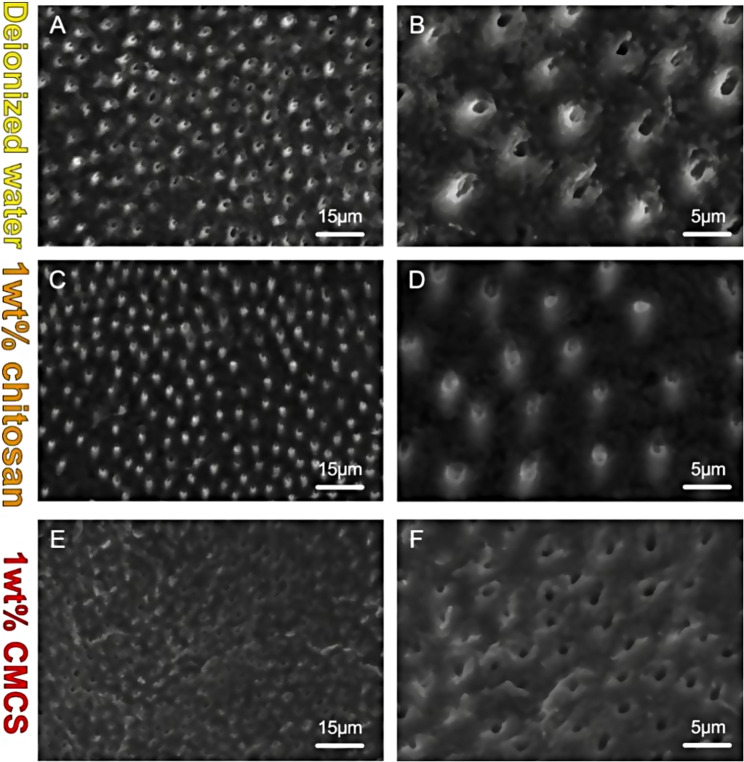

Scanning electron microscopy observation

The morphology of dentin surface was observed by scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 3A-F). Under low magnification, the dentin surface of all groups demonstrated a Control group presented a rough, uneven, irregular, and smear-free surface with open dentinal tubules. The density of peritubular dentin was higher than that of intertubular dentin since the peritubular dentin was protruded, resulting in a cuff-like appearance (Fig. 3A-B). The use of chitosan on laser-ablated dentin resulted in some partially plugged dentin tubules by the deposition of chitosan particles. The chitosan group demonstrated a scaly, smear-free surface, where cuff-like appearance was less evident compared to the control group (Fig. 3C-D). With CMCS treatment, the dentin surface exhibited a comparatively smooth, lamellar, fish scale, smear-free appearance with open dentinal tubules, whereas the cuff-like dentin structure was not presented. (Fig. 3E-F).

Fig. 3.

Microphotographs of laser-ablated dentin surfaces conditioned with deionized water, 1 wt% chitosan, and 1wt% CMCS each for 60s. Left column: low magnification (×1.0k). Right column: high magnification (×3.0k). Control group (A&B): Control group presented typically rough, uneven, irregular, and cuff-like appearance. Chitosan group (C&D): The dentin surface demonstrated less obvious cuff-like appearance and the dentin tubule were partially plugged. CMCS group (E&F):The dentin surface was relatively smooth with open dentinal tubules, whereas the cuff-like dentin structure was not presented

Shear bond strength test

The SBS values for each group are shown in Table 1. After 24 h of water storage, the highest SBS value (6.08 ± 2.12) was observed in CMCS group, which was significantly higher than that of control group (4.31 ± 1.26) (p < 0.05). However, there was no statistical difference between control group and chitosan group (5.65 ± 1.48) (p > 0.05). After thermal cycling, both chitosan (5.26 ± 2.30) and CMCS group (5.82 ± 1.90) presented higher bonding strength compared to control group (3.19 ± 1.32) (p < 0.05), with no statistical difference between chitosan group and CMCS group. For control group, those underwent immediate analysis had higher values than the aged specimens (p < 0.05), while chitosan and CMCS group preserved the bond strength after the aging process (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

The mean and standard deviation values for dhear bond strength (MPa) of laser-ablated dentin of each group before and after aging

| Study group | Before aging | After aging | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 4.3105 (1.2609) A,a | 3.1865 (1.3151) A,b | 0.044 |

| Chitosan | 5.6575 (1.4676) A,a | 5.2575 (2.3000) B,a | 0.626 |

| CMCS | 6.0774 (2.1246) B,a | 5.8211 (1.9021) B,a | 0.759 |

| P value† | 0.035 | 0.004 |

Means followed by the same uppercase letter compare treatments for the same time period; those followed by the same lowercase letter compare SBS values before and after aging for the same treatment. (p < 0.05)

*Independent Samples t-test (“before aging” versus “after aging”)

†One-way analysis of variance, Tukey honestly significant difference post hoc test

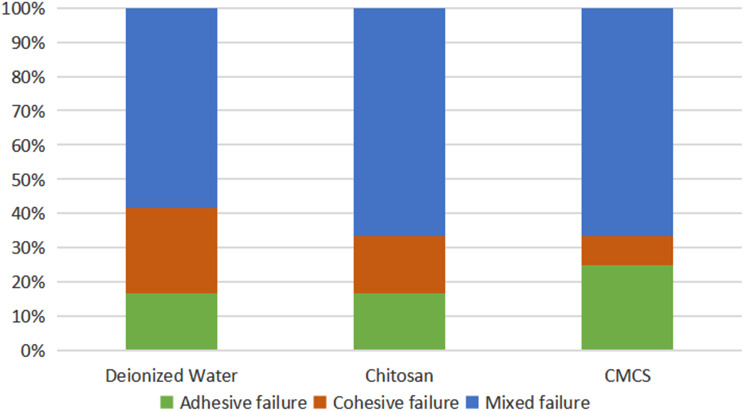

Failure mode

The failure modes were classified as adhesive, cohesive, or mixed and were defined as follows: adhesive failure had no signs of dentin fracture or composite resin remnants on the dentin surface; cohesive fractures exhibited complete fractures of dentin or resin; and mixed samples displayed both adhesive and cohesive failures. The percentage of failure mode distribution is shown in Figs. 4 and 5. Control group and chitosan group exhibited a considerable percentage of mixed failure (> 50%) before the aging process, while CMCS group exhibited the lowest prevalence. Adhesive failure was predominant in CMCS group before aging. After thermal cycling, CMCS group and chitosan group showed comparable percentage of mixed failure mode (61.5%), followed by control group (53.8%). The experimental groups before aging demonstrated an inhomogeneous distribution of failure modes and consisted primarily of mixed and cohesive failures, while the distribution of failure modes in groups with thermal cycling were more consistent. Cohesive failure was detected in all groups.

Fig. 4.

Failure mode of each experimental group before aging

Fig. 5.

Failure mode of each experimental group after aging

Discussion

Er:YAG laser is adept in removing carious dental hard tissue with minimal vibration, pressure, and noise [1]. The output wavelength of Er:YAG laser (2.94 μm) is strongly absorbed by water (3.0 μm) and OH¯ groups in hydroxyapatite (2.8 μm) [20, 21], resulting in thermo-mechanical ablation and efficient removal of hard dental tissue [3]. It was reported that ablation of Er:YAG laser results in a laser-modified layer and fused collagen on irradiated dentin, which adversely affect the effectiveness of the subsequent dentin bonding process [7].

The unsatisfactory bonding efficacy in subsequent resin restoration poses obstacles that hinder the clinical application of caries removal by Er:YAG laser [22, 23]. Both self-etch and etch-and-rinse adhesive systems have been used to perform dentin bonding after Er:YAG laser irradiation [2, 24–26], with the latter being more effective [23, 27]. Nevertheless, these existing acid-etching techniques lead to excessive demineralization of both extrafibrillar and intrafibrillar minerals [28]. The inability of resin monomers to completely infiltrate the demineralized collagen fibrils provides conditions for hydrolysis of exposed collagen and resin [29]. In addition, the exposure and activation of endogenous proteases during the depletion of intrafibrillar minerals would result in the degradation of the hybrid layer [30]. It was proposed that the structural defects within the resin-dentin surface could be avoided by preserving intrafibrillar minerals and selectively demineralizing extrafibrillar dentin, referred to as extrafibrillar demineralization, which could be realized by applying chelators such as chitosan and CMCS [31]. Extrafibrillar demineralization of the bonding surface via the application of chitosan and its derivatives was proposed as a strategy to enhance the bonding efficacy [16, 17, 31]. CMCS possesses great chelating capability and thus could be more suitable for the extrafibrillar demineralization protocol [15, 16]. Despite these promising features, there remains a paucity of evidence on whether chitosan and CMCS could be used in conjunction with Er:YAG laser. The experimental work presented here offers the first extensive exploration of the impact of chitosan and CMCS on the surface morphology and bond strength of laser-irradiated dentin, demonstrating that CMCS can enhance bond strength and durability through the induction of extrafibrillar demineralization, ultimately facilitating the bonding procedure following cavity preparation using the Er:YAG laser.

Under SEM examination, the typical cuff-like structure on dentin surface could be observed in control group, which could be attributed to the preferential removal of the water-rich intertubular dentin by Er:YAG laser [22, 32]. Chitosan group merely presented a slightly less obvious cuff-like appearance, suggesting that dentin morphology appeared to be unaffected by chitosan conditioning. This corroborates the findings of previous studies which reported that conditioning with chitosan had little effect on the morphology, wettability, and chemical composition of laser-irradiated dentin [12, 13]. In addition, chitosan particles were found to be deposited in dentinal tubule orifices (Fig. 3C-D). This observation agrees with that of Curylofo-Zotti et al. [12], who found that chitosan remnants appeared to be deposited on the intertubular dentin after laser ablation followed by dentin conditioning with chitosan. It is worth noting that, in comparison with the control and chitosan groups, the dentin surface treated with CMCS exhibited a smoother appearance, lacking the cuff-like structure associated with the other groups. It is hypothesized that CMCS, as a potent biomodifier, may restore microstructural alterations, microbreaks, and collagen fiber denaturation induced by laser irradiation [13]. This was further confirmed by the TEM results obtained in the present study, revealing that the organic matrix on the dentin surface of the CMCS group remained largely intact following laser irradiation (Fig. 2).

TEM observation provided a more detailed view of the morphology of dentin fibrils. No significant alteration in the dentin fibrils was observed after 1wt% chitosan conditioning, similar to the results of the control group (Fig. 2A-D). By contrast, CMCS group presented an inhomogenous partially demineralized zone (Fig. 2E-F), suggesting that under the conditions in the present study, only CMCS was capable of inducing extrafibrillar demineralization after laser irradiation. Although it has been betokened that CMCS enables the formation of extrafibrillar demineralization [16], recent study revealed that it could also be achieved via the application of chitosan. Gu et al. [17] demonstrated that without laser irradiation, 60 s of 1wt% chitosan conditioning resulted in a 150-nm-thick partially demineralized zone with the presence of intrafibrillar apatite crystallites, while the partially demineralized zone increased to 0.8 to 1 μm thick after 20 min of chitosan conditioning. This could be ascribed to the difference in experimental design, as the dentin collagen fibrils had been irradiated by Er:YAG laser before chitosan conditioning in the present study.

In addition to the morphology of laser-irradiated dentin, shear bond strength (SBS) after conditioning with chitosan and CMCS was compared. Our results showed that the application of CMCS was associated with the presence of extrafibrillar demineralization and greater shear bond strength as well as durability. SBS test showed that only CMCS group presented a statistically higher SBS value compared to control group shortly after the bonding procedure, with a negligible decrease in bonding strength after aging. The significant impact of CMCS on bonding efficacy was in consistence with a study of Yu et al. [16], which reported that CMCS treatment provided stronger and more durable bonding than traditional phosphoric acid etching. Notably, the durability of dentin-resin bond was enhanced by conditioning with chitosan compared to control group. This is in accordance with a previous study which revealed that the micro-TBS of laser-irradiated dentin-resin bond was preserved up to 6 months with the application of chitosan [10]. The SBS results obtained in the CMCS group can probably be explained by the greater alteration in the morphology of both dentin fibrils and dentin surface after laser irradiation as shown under TEM and SEM observations, which is an influential factor that affects the efficacy of dentin bonding [10].

The failure mode of fractured samples in SBS test was recorded and shown in Figs. 4 and 5. Surprisingly, a more frequent occurrence of adhesive failure, which is suggestive of inadequate bond in the resin-dentin interface [33], was found in the CMCS group compared to other groups before aging (Fig. 4). This finding was inconsistent with the SBS results, which demonstrated that CMCS could significantly enhance the bond strength shortly after the bonding procedure. Nevertheless, the mixed failure type, which is considered a sign of an intact interface [34, 35], was prevalent in the CMCS group and occurred more frequently than in the other groups after thermal cycling (Fig. 5). These findings suggest that, although the application of CMCS did not result in an ideal bonding interface immediately after bonding, it may be beneficial in preventing structural defects within the resin-dentin interface during prolonged use.

Contrary to expectations, 1wt% chitosan barely enhanced the bond strength after laser irradiation, though the bond strength was preserved after thermal cycling. More recently, literature has emerged that offers contradictory findings about the effectiveness of chitosan on dentin bonding. Baena et al. [36] reported that 0.1% chitosan did not increase the longevity of resin–dentin bonds, while Paschoini et al. [37] revealed that 2.5% chitosan significantly improved the immediate and preserved the 6-month bond strength of the adhesive interface. Another study by Mohamed et al. [38] indicated that the concentration of chitosan had a considerable impact on dentin bonding, as a statistically significant difference in TBS value was observed after treatment with 0.2% and 2.5% chitosan. These results suggest that the effectiveness of chitosan on bonding efficacy might be concentration-dependent. Although chitosan did not increase the SBS value compared to control group, neither did it induce extrafibrillar demineralization on dentin surface, no one can exclude the possibility that the effect of chitosan could also be remarkable by altering its concentration.

A possible limitation of the present study is that laser ablation was performed on sound dentin instead of artificial carious lesions. Since carious tissue contains more water components than sound dental tissue, the biomechanical properties of the remaining caries-affected dentin after caries removal may be different [12, 39]. Therefore, the data obtained cannot be directly extrapolated to conditions of carious lesions in human patients, but the data can serve as a guide for future investigations on the potential interrelation between the novel bonding procedure and the clinical efficacy of resin restoration after caries removal by Er:YAG laser.

Within the limitations of this study, it was found that although chitosan group upheld its bonding strength after aging, CMCS had greater capability to induce extrafibrillar demineralization and augment bonding efficacy, and thus being more preferable to apply in conjunction with Er:YAG laser in cavity preparation and resin restoration. Nevertheless, literature assessing the influence of chitosan concentration on its efficacy is relatively scarce, whereas the optimal clinical parameters of CMCS when applied in dentin bonding are yet to be explored. These topics warrant further studies.

Conclusion

The application of CMCS after laser ablation was associated with greater alteration on dentin surface morphology and the realization of extrafibrillar demineralization of dentin fibrils, while providing promising bonding strength and durability. CMCS has the potential to be applied in conjunction with Er:YAG laser in cavity preparation and resin restoration.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge all the support and contributions of participators.

Abbreviations

- Er:YAG

laser:erbium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser

- CMCS

Carboxymethyl chitosan

- MMPs

Matrix metalloproteinases

- TEM

Transmission electron microscope

- SEM

Scanning electron microscope

Author contributions

Q.Z.J. and Y.L. supervised the experiment and manuscript drafting. L.X.G. and C.C. contributed to the design of the study and performed most of the experiments. J.H.C., Y.T.H. and J.Z. participated in the experiment. C.C. and X.C. carried out data analysis. Y.L. and X.C. participated in drafting the manuscript and performing critical revision of the draft. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National College Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program [grant number 2022A083]; and the Guangzhou Medical University Students Innovative Capability Enhancement Program [grant number 02-408-2203-2074].

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board and ethics committee of the affiliated stomatology hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (JCYJ2023003) in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lanxi Guan and Chen Cai contributed equally to this work and shared co-first authorship.

Contributor Information

Qianzhou Jiang, Email: jqianzhou@126.com.

Yang Li, Email: antonialee@foxmail.com.

References

- 1.de Azevedo CS, Carneiro PMA, Aranha ACC, Francisconi-dos-Rios LF, de Freitas PM, Matos AB. Long-term effect of Er:YAG laser on adhesion to caries-affected dentin. Lasers Dent Sci. 2018;2(1):19–28. doi: 10.1007/s41547-017-0013-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang JH, Yang K, Zhang BZ, Zhou ZF, Wang ZR, Ge X, et al. Effects of Er:YAG laser pre-treatment on dentin structure and bonding strength of primary teeth: an in vitro study. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20(1):316. doi: 10.1186/s12903-020-01315-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Comba A, Baldi A, Michelotto Tempesta R, Cedrone A, Carpegna G, Mazzoni A, et al. Effect of Er:YAG and burs on coronal dentin Bond Strength Stability. J Adhes Dent. 2019;21(4):329–35. doi: 10.3290/j.jad.a42932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nahas P, Zeinoun T, Namour M, Ayach T, Nammour S. Effect of Er:YAG laser energy densities on thermally affected dentin layer: morphological study. Laser Ther. 2018;27(2):91–7. doi: 10.5978/islsm.18-OR-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuna EB, Ozel E, Kasimoglu Y, Firatli E. Investigation of the Er: YAG laser and diamond bur cavity preparation on the marginal microleakage of Class V cavities restored with different flowable composites. Microsc Res Tech. 2017;80(5):530–6. doi: 10.1002/jemt.22827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karadas M, Caglar I. The effect of Er:YAG laser irradiation on the bond stability of self-etch adhesives at different dentin depths. Lasers Med Sci. 2017;32(5):967–74. doi: 10.1007/s10103-017-2194-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trevelin LT, Silva BTF, Arana-Chavez VE, Matos AB. Impact of Er:YAG laser pulse duration on ultra-structure of dentin collagen fibrils. Lasers Dent Sci. 2018;2(2):73–9. doi: 10.1007/s41547-017-0020-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machado AHS, Garcia IM, Motta ASD, Leitune VCB, Collares FM. Triclosan-loaded chitosan as antibacterial agent for adhesive resin. J Dent. 2019;83:33–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2019.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shrestha A, Friedman S, Kishen A. Photodynamically crosslinked and chitosan-incorporated dentin collagen. J Dent Res. 2011;90(11):1346–51. doi: 10.1177/0022034511421928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curylofo-Zotti FA, Scheffel DLS, Macedo AP, Souza-Gabriel AE, Hebling J, Corona SAM. Effect of Er:YAG laser irradiation and chitosan biomodification on the stability of resin/demineralized bovine dentin bond. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2019;91:220–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2018.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pascale C, Geaman J, Mendoza C, Gao F, Kaminski A, Cuevas-Nunez M, et al. In vitro assessment of antimicrobial potential of low molecular weight chitosan and its ability to mechanically reinforce and control endogenous proteolytic activity of dentine. Int Endod J. 2023;56(11):1337–49. doi: 10.1111/iej.13962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curylofo-Zotti FA, Fernandes MP, Martins AA, Macedo AP, Nogueira LFB, Ramos AP, et al. Caries removal with Er:YAG laser followed by dentin biomodification with carbodiimide and chitosan: wettability and surface morphology analysis. Microsc Res Tech. 2020;83(2):133–9. doi: 10.1002/jemt.23395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curylofo-Zotti FA, Tanta GS, Zucoloto ML, Souza-Gabriel AE, Corona SAM. Selective removal of carious lesion with Er:YAG laser followed by dentin biomodification with chitosan. Lasers Med Sci. 2017;32(7):1595–603. doi: 10.1007/s10103-017-2287-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos RMC, Scatolin RS, de Souza Salvador SL, Souza-Gabriel AE, Corona SAM. Er:YAG laser in selective caries removal and dentin treatment with chitosan: a randomized clinical trial in primary molars. Lasers Med Sci. 2023;38(1):208. doi: 10.1007/s10103-023-03869-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shariatinia Z. Carboxymethyl Chitosan: Properties and biomedical applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;120(Pt B):1406–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.09.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu F, Luo ML, Xu RC, Huang L, Yu HH, Meng M, et al. A novel dentin bonding scheme based on extrafibrillar demineralization combined with covalent adhesion using a dry-bonding technique. Bioact Mater. 2021;6(10):3557–67. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gu LS, Cai X, Guo JM, Pashley DH, Breschi L, Xu HHK, et al. Chitosan-based Extrafibrillar demineralization for dentin bonding. J Dent Res. 2019;98(2):186–93. doi: 10.1177/0022034518805419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li B, Zhu X, Ma L, Wang F, Liu X, Yang X, et al. Selective demineralisation of dentine extrafibrillar minerals-A potential method to eliminate water-wet bonding in the etch-and-rinse technique. J Dent. 2016;52:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu L, Mazzoni A, Gou Y, Pucci C, Breschi L, Pashley DH, et al. Zymography of hybrid layers created using Extrafibrillar demineralization. J Dent Res. 2018;97(4):409–15. doi: 10.1177/0022034517747264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He Z, Chen L, Hu X, Shimada Y, Otsuki M, Tagami J, et al. Mechanical properties and molecular structure analysis of subsurface dentin after Er:YAG laser irradiation. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2017;74:274–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2017.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donmez N, Gungor AS, Karabulut B, Siso SH. Comparison of the micro-tensile bond strengths of four different universal adhesives to caries-affected dentin after ER:YAG laser irradiation. Dent Mater J. 2019;38(2):218–25. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2017-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monghini EM, Wanderley RL, Pecora JD, Palma Dibb RG, Corona SA, Borsatto MC. Bond strength to dentin of primary teeth irradiated with varying Er:YAG laser energies and SEM examination of the surface morphology. Lasers Surg Med. 2004;34(3):254–9. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vermelho PM, Freitas PM, Reis AF, Giannini M. Influence of Er:YAG laser irradiation settings on dentin-adhesive interfacial ultramorphology and dentin bond strength. Microsc Res Tech. 2022;85(8):2943–52. doi: 10.1002/jemt.24144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koliniotou-Koumpia E, Kouros P, Zafiriadis L, Koumpia E, Dionysopoulos P, Karagiannis V. Bonding of adhesives to Er:YAG laser-treated dentin. Eur J Dent. 2019;6(1):16–23. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1698926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koyuturk AE, Ozmen B, Cortcu M, Tokay U, Tosun G, Erhan Sari M. Effects of Er:YAG laser on bond strength of self-etching adhesives to caries-affected dentin. Microsc Res Tech. 2014;77(4):282–8. doi: 10.1002/jemt.22340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen ML, Ding JF, He YJ, Chen Y, Jiang QZ. Effect of pretreatment on Er:YAG laser-irradiated dentin. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30(2):753–9. doi: 10.1007/s10103-013-1415-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sirin Karaarslan E, Yildiz E, Cebe MA, Yegin Z, Ozturk B. Evaluation of micro-tensile bond strength of caries-affected human dentine after three different caries removal techniques. J Dent. 2012;40(10):793–801. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Betancourt DE, Baldion PA, Castellanos JE. Resin-dentin bonding interface: mechanisms of degradation and strategies for stabilization of the hybrid layer. Int J Biomater. 2019;2019:5268342. doi: 10.1155/2019/5268342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y, Thomopoulos S, Chen C, Birman V, Buehler MJ, Genin GM. Modelling the mechanics of partially mineralized collagen fibrils, fibres and tissue. J R Soc Interface. 2014;11(92):20130835. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2013.0835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frassetto A, Breschi L, Turco G, Marchesi G, Di Lenarda R, Tay FR, et al. Mechanisms of degradation of the hybrid layer in adhesive dentistry and therapeutic agents to improve bond durability–A literature review. Dent Mater. 2016;32(2):e41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mai S, Wei CC, Gu LS, Tian FC, Arola DD, Chen JH, et al. Extrafibrillar collagen demineralization-based chelate-and-rinse technique bridges the gap between wet and dry dentin bonding. Acta Biomater. 2017;57:435–48. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunn WJ, Davis JT, Bush AC. Shear bond strength and SEM evaluation of composite bonded to Er:YAG laser-prepared dentin and enamel. Dent Mater. 2005;21(7):616–24. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mirzaei K, Ahmadi E, Rafeie N, Abbasi M. The effect of dentin surface pretreatment using dimethyl sulfoxide on the bond strength of a universal bonding agent to dentin. BMC Oral Health. 2023;23(1):250. doi: 10.1186/s12903-023-02913-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Botelho LP, Dias De Oliveira SG, Douglas De Oliveira DW, Galo R. Microtensile resistance of an adhesive system modified with chitosan nanoparticles. J Conserv Dent. 2022;25(3):278–82. doi: 10.4103/jcd.jcd_612_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al Habdan AH, Al Rabiah R, Al Busayes R. Shear bond strength of acid and laser conditioned enamel and dentine to composite resin restorations: an in vitro study. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2021;7(3):331–7. doi: 10.1002/cre2.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baena E, Cunha SR, Maravic T, Comba A, Paganelli F, Alessandri-Bonetti G, et al. Effect of Chitosan as a cross-linker on matrix metalloproteinase activity and bond stability with different adhesive systems. Mar Drugs. 2020;18(5):263. doi: 10.3390/md18050263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paschoini VL, Ziotti IR, Neri CR, Corona SAM, Souza-Gabriel AE. Chitosan improves the durability of resin-dentin interface with etch-and-rinse or self-etch adhesive systems. J Appl Oral Sci. 2021;29:e20210356. doi: 10.1590/1678-7757-2021-0356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohamed AM, Nabih SM, Wakwak MA. Effect of chitosan nanoparticles on microtensile bond strength of resin composite to dentin: an in vitro study. Brazil Dent Sci. 2020;23(2):1–10. doi: 10.14295/bds.2020.v23i2.1902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Curylofo-Zotti FA, Oliveira VC, Marchesin AR, Borges HS, Tedesco AC, Corona SAM. In vitro antibacterial activity of green tea-loaded chitosan nanoparticles on caries-related microorganisms and dentin after Er:YAG laser caries removal. Lasers Med Sci. 2023;38(1):50. doi: 10.1007/s10103-023-03707-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.