Abstract

Objective

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an enduring condition characterized by a chronic course and impairments across several areas. Despite its significance, treatment options remain limited, and remission rates are often low. Ketamine has demonstrated antidepressant properties and appears to be a promising agent in the management of PTSD.

Method

A systematic review was conducted in PubMed/MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, Clinicaltrials.gov, Lilacs, Scopus, and Embase, covering studies published between 2012 and December 2022 to assess the effectiveness of ketamine in the treatment of PTSD. Ten studies, consisting of five RCTs, two crossover trials, and three non-randomized trials, were included in the meta-analysis.

Results

Ketamine demonstrated significant improvements in PCL-5 scores, both 24 hours after the initial infusion and at the endpoint of the treatment course, which varied between 1 to 4 weeks in each study. Notably, the significance of these differences was assessed using the Two Sample T-test with pooled variance and the Two Sample Welch’s T-test, revealing a statistically significant effect for ketamine solely at the endpoint of the treatment course (standardized effect size= 0.25; test power 0.9916; 95% CI = 0.57 to 17.02, p=0.0363). It is important to note that high heterogeneity was observed across all analyses.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that ketamine holds promise as an effective treatment option for PTSD. However, further trials are imperative to establish robust data for this intervention.

Keywords: post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD, ketamine, systematic review, meta-analysis

Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a chronic and debilitating condition, commonly associated with comorbidities, primarily mood and substance use disorders. This scenario leads to impairments across several domains, encompassing labor, economic and social areas (Goldberg et al., 2014; Yehuda et al., 2015; Shalev et al., 2017). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), published by the American Psychiatric Association (2013), there are four primary clusters of symptoms: persistent avoidance, intrusion symptoms, alterations in mood and cognition, and changes in arousal and reactivity. Epidemiological studies have estimated the 12-month prevalence of these conditions at approximately 5.3% and the lifetime prevalence at 8.3% in the United States (Benjet et al., 2016). Worldwide, the most frequently reported traumatic events include various forms of violence, such as physical and sexual assault, as well as accidents and traumatic injuries (Kilpatrick et al., 2013).

Despite their significance in treating PTSD, only two pharmacological agents, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) paroxetine and sertraline, have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, other medications, including the serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine, atypical antipsychotics, and the alpha-2 adrenergic receptor blocker prazosin, are frequently prescribed as off-label options (Sharpless & Barber, 2011; Alexander, 2012; Green, 2014). Unfortunately, remission rates with these treatments are relatively low, typically around 20-30%, and patients often experience persistent residual symptoms (Friedman et al., 2007; Berger et al., 2009; Krystal et al., 2017). Recent advances in inflammatory, molecular, neuroendocrine, and neuroimaging markers underscore the urgent need for research into new PTSD treatment modalities (Daskalakis et al., 2013; Zoladz & Diamond, 2013; Kunimatsu et al., 2020).

Ketamine, an NMDA glutamate receptor antagonist, has demonstrated notable antidepressant properties. Its effects are not limited to interactions with glutamatergic receptors, as they also involve various complex signaling cascades and molecular targets (Abdallah et al., 2018; Pereira & Hiroaki-Sato, 2018). Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have underscored the rapid antidepressant effects of ketamine, which are apparent not only in patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) (Zarate et al., 2006; Diazgranados et al., 2010; Lapidus et al., 2014) but also in those exhibiting symptoms of suicidality (Andrade, 2018; Lengvenyte et al., 2019).

The use of ketamine in treating PTSD has gained increasing recognition. Glutamatergic activity is crucial in the formation of memories, including the encoding of traumatic events (Malenka & Nicoll, 1999; Reul & Nutt, 2008). Additionally, studies utilizing animal models have shown that chronic stress exposure may lead to alterations in glutamatergic transmission, potentially heightening the susceptibility to mental disorders (McEwen, 1999; Radley & Morrison, 2005). In light of these findings, this systematic review and meta-analysis is dedicated to updating the current evidence on the efficacy of ketamine in the treatment of PTSD.

Methods

The methodology of this study was rigorously designed in alignment with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). Additionally, the protocol for this systematic review and meta-analysis was duly registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, under the registration number PROSPERO-CRD42022378592. meta-analysis

Search Strategy

The search strategy for this systematic review was meticulously executed across multiple electronic databases, including MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase, Scopus, Lilacs, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the Cochrane Library. Our search parameters were designed to include studies published from 2012 through December 2022, imposing no language restrictions to ensure a comprehensive inclusion of relevant literature. To tailor our search effectively, we adapted keywords relevant to our study’s objectives, employing specific indexing terms such as MeSH in PubMed. Additionally, to capture any potentially overlooked studies, we conducted manual searches. The detailed search strategy for each database is thoroughly documented in the supplementary materials accompanying this article.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This study included articles that met the following criteria: (1) The assessment of adults with a primary diagnosis of PTSD. (2) The use of a validated diagnostic method for PTSD. (3) The inclusion of subjects who received at least one infusion of ketamine, regardless of the route of administration. For the exclusion criteria, the study did not consider: (1) Previously published reviews, case reports, letters, editorials, as well as systematic reviews and meta-analyses. (2) Studies involving patients with comorbid psychotic disorders, active substance use disorders, or severe clinical conditions (neurological, pulmonary, and cardiovascular).

Screening Selection

Two authors, TMA and JPP, independently conducted the initial screening of titles and abstracts, followed by a detailed examination of the full-text manuscripts, adhering to the pre-established selection criteria. In instances of disagreement regarding inclusion, the issues were resolved through group discussions until a consensus was reached.

Data extraction from the included articles was performed using standardized spreadsheets. The extracted data encompassed: (1) first author and year of publication; (2) country of the study; (3) study design; (4) participant characteristics; (5) sample size; (6) severity of diagnosis; (7) study outcomes. The initial data extraction was carried out by author TMA and subsequently reviewed for accuracy and completeness by JPP, INB, CRMM, URLS, RRU, and QC.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was the improvement in PTSD symptoms, assessed using the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) scores, at two specific time points:

24 hours after the first ketamine infusion.

At the pharmacological endpoint, as defined by the protocol in each individual study.

Notably, secondary depressive symptoms, typically measured by the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), were not included in the analysis.

Risk of Bias Assessment

We conducted a comprehensive risk of bias assessment using three distinct tools tailored to the study designs employed. The Version 2 of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) (Sterne et al., 2019) was utilized for randomized trials, including a specialized version for crossover trials that specifically addressed potential carryover effects. Additionally, we employed the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies - of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool (Sterne et al., 2016).

For the RoB 2 assessment, we evaluated the risk of bias across six key domains: the randomization process, timing of participant identification or recruitment, deviations from the intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of the reported result. The overall risk of bias was categorized as either low, moderate, or high.

In the case of the ROBINS-I assessment, we examined seven domains of bias: confounding, participant selection into the study, classification of interventions, deviations from intended interventions, missing data, measurement of outcomes, and selection of the reported result. The overall risk of bias was classified as "low risk," "moderate risk," "serious risk," or "critical risk."

To ensure the robustness of our assessment, two authors (TMA, URLS) independently performed the risk of bias evaluation. In instances where disagreements arose, a third author (RRU) was consulted to facilitate consensus.

Statistical Analysis

In order to evaluate the impact of ketamine on the improvement of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, we conducted data extraction at two key time points: baseline and post ketamine infusion. The assessment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) severity in these studies was carried out using three distinct measurement scales: the PCL-5, the Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R), and the Clinician-Administered Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). For each study, we gathered data on the mean scores and standard deviations (SD) associated with these measurement scales, enabling a comprehensive analysis of the effectiveness of ketamine in mitigating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms.

Since most of the studies employed the PCL-5 as the baseline score scale, the IES-R and CAPS-5 scores were parameterized using simple linear regression. The linear regression models were powered by studies that assessed both PCL-5 x IES-R and PCL-5 x CAPS-5 scores (Ashbaugh et al., 2016; Sveen et al., 2016; Murphy et al., 2017). (The figures depicting the results of the linear regression can be found in the supplementary material).

The mean difference score (MD) was computed by subtracting the mean score at baseline from the mean score at the treatment endpoint of interest. The standard deviation for the mean difference (SDMD) was calculated using the following formula:

In this equation, 'S₁' represents the standard deviation of the mean score at baseline, 'S₂' represents the standard deviation of the mean score after ketamine infusion, and 'r' is the Pearson correlation coefficient. The 'r' value is calculated from the mean scores of all studies included in the analysis. Our meta-analysis utilized the mean score difference at baseline and at the treatment endpoint (MD ± SDMD). These scores were stratified into intervention vs. control groups and categorized by immediate effects (at 24 hours) and effects over time (ranging from 1 day to a 4-week period).

To compare the pooled mean differences in the intervention and control groups, we examined the 24-hour time point and the endpoint defined by each study, which typically corresponded to the last ketamine infusion and the final outcome measured in relation to the pharmacological intervention.

To determine the statistical significance of differences between the two groups, we employed both the two-sample Welch’s T-test and the two-sample T-test with pooled variances, considering the Hypothesis Testing (H0: μ1= μ2 and H1: μ1≠ μ2).

Results

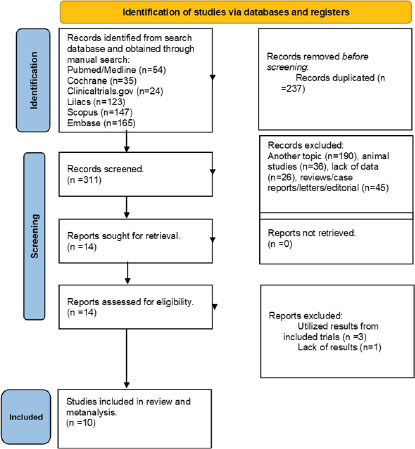

Out of the initial 548 references, 237 duplicates were removed, leaving 311 records for title and abstract assessment. Among these, 297 studies were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria, resulting in 14 studies evaluated for eligibility. Three studies were excluded as they utilized data from the same sample, and one study was excluded due to insufficient data.

Ultimately, our systematic review and meta-analysis included a total of ten studies, comprising five RCTs, two crossover randomized trials, and three non-randomized trials. These studies are cited as follows: Feder et al., 2014; Pradhan et al., 2017; Albott et al., 2018; Pradhan et al., 2018; Ross et al., 2019; Dadabayev et al., 2020; Shiroma et al., 2020; Feder et al., 2021; Harpaz-Rotem, 2022; and Abdallah et al., 2022.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only

Population

The total sample size for this study was 363 individuals; however, one study (Ross et al., 2019) did not provide demographic information for the 30 participants in their trial. Among the 333 individuals with available data, the mean age was 41.9 years (± 3.95), with 208 of them being male (62.4%). The mean baseline PCL-5 score was 51.88 (± 8.86).

Among the ten studies included in our analysis, four (Feder et al., 2014; Feder et al., 2021; Abdallah et al., 2022; Harpaz-Rotem, 2022) assessed patients with moderate to severe PTSD based on their CAPS-5 scores. Two studies focused on patients with refractory PTSD, defined as those who had not responded to at least two antidepressants and had undergone cognitive behavioral therapy for a minimum of six months (Pradhan et al., 2017; Pradhan et al., 2018). Additionally, one study examined patients with comorbid TRD (Albott et al., 2018), while another study specifically assessed military veterans with combat-related PTSD (Ross et al., 2019).

Nine studies utilized intravenous ketamine at a dosage of 0.5 mg/kg. One of these studies (Abdallah et al., 2022) included an additional intervention arm with a lower dosage of 0.2 mg/kg, while another study (Ross et al., 2019) employed a higher dosage of 1 mg/kg. Furthermore, four studies investigated the use of ketamine in conjunction with psychotherapy. Two studies (Pradhan et al., 2017; Pradhan et al., 2018), authored by the same group, implemented a mindfulness-related modality called TIMBER. The other two studies (Shiroma et al., 2020; Harpaz-Rotem, 2022) assessed the combination of ketamine with prolonged exposure therapy. It is noteworthy that all of these studies were conducted within the United States of America.

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the studies included in our analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies (n = 10)

| Author(s) and Year | Country | Study Design | Characteristics of the Participants | Sample size | Diagnosis | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdaliah et al. 202233 | USA | RCT | Veterans and active-duty service members | 158 participants [standard dose 0.5 mg/kg (n= 51): Low dose 0.2 mg/k5 (== 53 Placebo (n=54) in : schedule of a infusions in 4 weeks | Severe PTSD | in the primary analysis, there was no significant difference in the treatment effect There was improvement in PCL-5 scores for all treatment groups Moreover, the lower dose compared to placebo was not significantly different after the first administration of Keta- mine |

| Albott et al., 2018 34 | USA | Non-randomized | Male and female veterans, aged 18-75 years | 15 participants completed the schedule of 6 infusions 0.5 mg/kg) | Moderate to severe PTSO and TRD | The study found a decrease in baseline symptoms 24 hours after the sixth ketamine infusion in addition, the CAPS-5 score showed . significant reduction after completing the series of 6 infusions |

| Dadabayev et al., 2020 35 | USA | RCT | US military veterans in an outpatient setting | 41 participants (aged 29 to 65 were ran- domized to receive one dose of ketamine 0.5 mg/kg) or ketorolac (15mg) | PTSO and Chronic Pain (CP) | There was a significant main effect in the group with CP and PTSD in reduction of symptoms The analysis was performed through the IES- R scale in 24 hours and 7 days after ketamine administration |

| Feder et al., 2021 36 | USA | RCT | individuals between 18 and 70 years | 30 participants were randomized to receive Ketamine (0.3 mg/kg) or midazolam (0.045 mg/kg) in . schedule of 6 infusions in 2 weeks | Severe PTSO | The use of ketamine in the active group significantly improved the CAPS-5 and MADRS score: compared to control for two weeks |

| Feder et. at 2014 37 | USA | randomized double-blind placebo- controlled crossover clinical trial | Patients with chronic PTSD | 41 subject: were randomized to receive one infusion of ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) or midazolam (0.045 mg/kg) | Severe PTSO | The primary results showed positive results regarding the total scores of IES-R 24 hours after ketamine infusion compared to mids- zolam |

| Harpar-Rotem. 202238 | USA | RCT | Subject: between 21-75 years | 28 participants were randomized to receive ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) or midazolam (0.045 mg/kg) + Prolonged Exposure Therapy | Severe PTSO | Baseline x end of treatment PCL-5 scores (Mean (SD): in the inter vention arm: 48.8 (12.3) , 29.5 (20.7) Baseline . end of treatment PCL-5 scores in the control arm: 44.4 (14.4) . 35.1 (16.8). |

| Pradhan et al., 2018 39 | USA | RCT | Adults in an outps- tient setting | 20 patients were randomized to receive 01 infusion of ketamine (0.5mg/kg) or normal saline + TIMBER psychotherapy | Refractory PTSO | in PCL scores there were no significant differences between the two study arms after 24h TIMBER-Ketamine and TIMBER-Placebo |

| Pradhan et al., 2017 40 | USA | randomized double-blind placebo- controlled crossover clinical trial | Adults in an outps- tient setting | 10 participants patients were randomized to receive 01 infusion of ketamine (0.5mg/ 5 or normal saline + TIMBER psycho- therapy | Refractory PTSO | TIMBER psychotherapy augmented with ketamine were associated with better response and prolonged therapeutic effects compared to TIMBER-Placebo |

| Ross et al. 2019 41 | USA | Non- rand- omized | US veterans aged 18-75 years | 30 participants received 6 infusions of ketamine | Combated related PSTD | A 50% reduction in depression symptoms and 44% reduction in PTSD symptoms was found |

| Shiroma et al., 2020 42 | USA | Non- rand- omized | US veterans aged 18-75 years | 10 participants received 03 weekly infu- sions of ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) + 10 weeks prolonged exposure therapy trial | Chronic and at least moderate PTSD | Repeated IV ketamine showed potential efficacy-enhancing effects of standard prolonged exposure therapy with good tolerability. |

RCT = Randomized Controlled Trial; PTSD = Post Traumatic Stress Disorder; PCL-5 = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5; TRD = Treatment Resistant Depression; CAPS-5 = Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5; IES-R = Impact of Events Scale-Revised; MADRS = Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating;

Meta-analysis for effects over time

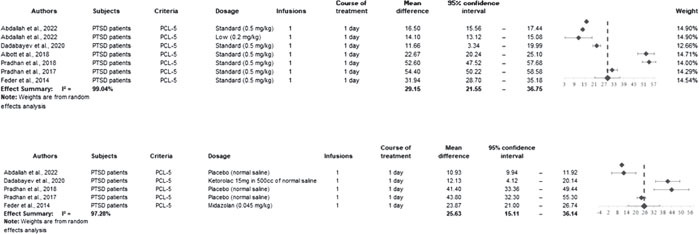

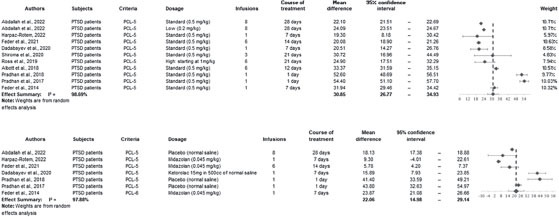

The meta-analysis was conducted using the methodology outlined in the Comprehensive Meta-analysis Software – Version 3.0 (2022). Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, with moderate heterogeneity assumed at I2 values greater than 50%, and high heterogeneity at values exceeding 75%. A random-effects model was employed to account for both within-study and between-study variability. In our initial assessment, four studies (Ross et al., 2019; Shiroma et al., 2020; Feder et al., 2021; Harpaz-Rotem, 2022) were excluded as they did not measure the PCL-5 score 24 hours post the initial ketamine infusion.

The improvement in PCL-5 mean scores was more pronounced in the ketamine group compared to the control groups in both analyses: at the endpoint of the treatment course (30.85 vs. 22.06) and in the 24-hour analysis (29.15 vs. 25.63). We employed both the Two Sample T-test with pooled variance and the Two Sample Welch’s T-test to evaluate the significance of these differences. For the endpoint of the treatment course, ketamine showed a significant effect (standardized effect size = 0.25; test power = 0.9916; 95% CI = 0.57 to 17.02; p = 0.0363). However, the effects of ketamine after the first 24 hours were not statistically significant (standardized effect size = 0.069; test power = 0.9747; 95% CI = -9.31 to 16.36; p = 0.5897). There was evidence of high between-study heterogeneity in all subgroup analyses (I2 = 99.04%, 97.28%, 98.69%, and 97.88%, respectively; p < 0.001).

The forest plots for each analysis are presented in figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Forest Plot for Mean Difference in PCL-5 score, 24 hours after ketamine infusion for intervention and control groups, respectively

Figure 3.

Forest Plot for Mean Difference in baseline PCL-5 score and at the endpoint ketamine treatment for intervention and control groups, respectively

The confidence interval for the difference between active and control groups is presented in tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Hypothesis Testing and Confidence Interval Analysis for 24-Hour Treatment, Comparing Mean Differences Between Intervention and Control Groups

| Immediate effects (24 hours) - Two Sample T-test with pooled variance | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Sample size | Variance | Pooled Mean Difference |

| Study (1) | 167 | 2509.51 | 29.15 |

| Control (2) | 98 | 2820.25 | 25.63 |

| Results | |||

| Pooled variance | 2624.12 | Standardized effect sizes | 0.0690 |

| t-statistic | 0.5400 | Test power | 0.9747 |

| P-value | 0.5897 | 95% Confidence Interval | -9.31 < μ1- μ2 < 16.36 |

Table 3.

Hypothesis Testing and Confidence Interval for the Endpoint Course of Treatment, Comparing Mean Differences Between Intervention and Control Groups

| Time effects (1-10 weeks) - Two Sample Welch’s T-test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Sample size | Variance | Pooled Mean Difference |

| Study (1) | 234 | 1014.71 | 30.85 |

| Control (2) | 126 | 1645.53 | 22.06 |

| Results | |||

| Pooled variance | 1234.97 | Standardized effect sizes | 0.25 |

| t-statistic | 2.1076 | Test power | 0.9916 |

| P-value | 0.0363 | 95% Confidence Interval | 0.57 < μ1- μ2 < 17.02 |

In the analysis of the risk of bias, three studies (Feder et al., 2014; Abdallah et al., 2022; Feder et al., 2021) representing 30% of the total, were classified as having a low risk of bias in the overall assessment. Four studies, accounting for 40% (Pradhan et al., 2017; Pradhan et al., 2018; Dadabayev et al., 2020; Harpaz-Rotem, 2022), were classified as having a moderate risk of bias. Meanwhile, all three non-randomized studies (Albott et al., 2018; Ross et al., 2019; Shiroma et al., 2020), also representing 30%, were classified as having a serious overall risk of bias. Specifically, the most problematic dimensions of bias identified were: (1) bias due to confounding; (2) bias due to deviations from intended interventions; and (3) bias due to missing data, with these concerns primarily associated with the non-randomized studies. For the studies classified as having an overall moderate risk of bias, it is important to note that a low risk of bias was found in most subdomains of analysis, as detailed in the supplementary material.

Discussion

our primary objective in conducting this meta-analysis was to evaluate the effectiveness of ketamine as a pharmacological intervention for PTSD, in light of the emerging data in this field. We anchored our analysis on a linear regression of PCL-5 scores to assess improvements in the core symptoms of PTSD. Our findings indicate that ketamine is associated with symptom improvements in PTSD, noticeable both 24 hours after the first infusion and at the conclusion of the treatment period. Importantly, these improvements were found to be statistically significant when compared to control agents only in the endpoint analysis.

A previous meta-analysis by Albuquerque et al. (2022) also found evidence supporting the beneficial effects of ketamine in treating PTSD. In their analysis, the positive effects were predominantly observed in MADRS scores, which may indicate improvements in secondary depressive symptoms associated with PTSD, rather than the primary symptoms of the disorder. This finding is particularly relevant considering the high rates of co-occurrence of PTSD and major depressive disorder (MDD), especially among military veteran populations, who form a significant portion of the study samples. Epidemiological data indicate that approximately 50% of veterans in the US are afflicted with both PTSD and MDD (Seal et al., 2010; Rytwinski et al., 2013). Additionally, long-term treatment with ketamine has been associated with reduced hospitalization rates, particularly for severe comorbid conditions such as PTSD and TRD (Hartberg et al., 2018).

Future researchers should focus on the longterm effects of ketamine and the assessment of adjunctive psychotherapy treatment. Synaptic deficits are intimately linked to the development of PTSD and related disabilities (Krystal et al., 2017). Stress conditions act directly in glutamate synapsis leading to a reducing signaling of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and resulting in loss and reduction of dendritic spines. Moreover, there is evidence that severe symptomatology is related to reduced cortical thickness. Such mechanisms are intricately connected to the pathophysiology of PTSD (Popoli et al, 2011; Wrocklage et al., 2017).

The properties of ketamine may contribute to the restoration of synaptic connectivity and an increase in neuronal plasticity. The proposed mechanisms behind these actions are believed to involve the release of glutamate and the blockade of extra-synaptic NMDA receptors, which lead to changes in intracellular cascade signaling pathways. These neural mechanisms increase BDNF, AMPA signaling and changes in intracellular messenger phosphorylation (Autry et al., 2011; Li et al., 2011; Krystal et al., 2013). Furthermore, ketamine has shown effect in reducing traumatic memories and fear, an effect attributed to its action on synaptic pathways in key brain regions, including the hippocampus, basal ganglia, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex (Pradhan et al., 2017; Shiroma et al., 2020).

Most studies in our meta-analysis evaluated ketamine as a monotherapy for treating PTSD. A RCT by Rothbaum et al. (2006) found that patients who partially responded to an initial treatment with sertraline showed increased benefits from 10 sessions (twice a week) of prolonged exposure (PE) therapy. Another RCT (Schneier et al., 2012) demonstrated that patients treated with both PE and paroxetine for 10 weeks experienced significant improvements in PTSD symptoms compared to those treated with PE and a placebo. Additionally, there is evidence supporting the effectiveness of ketamine-assisted therapy (KAP) in significantly reducing depressive and anxiety symptoms (Dore et al., 2019). Moreover, combination of ketamine and prolonged exposure therapy presents a promising avenue for future research (Shiroma et al., 2020; Harpaz-Rotem, 2022).

Ketamine was found to be well-tolerated in the studies analyzed. The most common side effects reported were dose-related dissociative and psychomimetic symptoms. These side effects generally peaked 40 minutes post-infusion and subsided to baseline levels within two hours. Notably, no psychotic or manic symptoms were observed during treatment (Feder et al., 2014; Feder et al., 2021; Abdallah et al., 2022). Additionally, exposure to ketamine was not linked to an exacerbation of PTSD-related symptoms. These data are consistent with previous studies that have assessed the safety and tolerability of ketamine (Wan et al., 2015; Vázquez et al., 2021).

The primary strength of our study lies in the increased number of included studies and, consequently, the enlarged intervention sample size in our analysis. Furthermore, we conducted a linear regression analysis of PCL-5 values to evaluate improvements in key symptoms of PTSD. Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge that our study does face several limitations. Firstly, high heterogeneity was observed in all analyses, indicating potential methodological issues in some studies, and raising concerns about bias influence, as confirmed by the risk of bias assessment. Secondly, most studies involved small sample sizes, with the RCT by Abdallah et al. (2022) comprising 43.5% (158 out of 363 participants) of our sample. Thirdly, our analysis was limited to assessing short-term treatment outcomes due to the nature of the available data. Finally, the observed high heterogeneity may be attributed to variations in study designs (such as the absence of control groups), sample sizes, the number of ketamine infusions, baseline pharmacological treatments, associations with psychotherapy, and differences in endpoints as defined by each study's protocol.

Conclusion

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis, employing linear regression of PCL-5 values to assess the effectiveness of ketamine in treating PTSD. Improvements were observed both 24 hours post-infusion and at the endpoint of the pharmacological treatment, which ranged from 1 to 4 weeks. Nevertheless, the improvement was notably more pronounced compared to the control group only in the later analysis. Our study suggests that ketamine could be a promising option for the treatment of PTSD, particularly when paired with various psychotherapy approaches. However, it is essential to highlight that further randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are needed to establish more robust evidence for this intervention.

References

- Abdallah, C. G., Roache, J. D., Gueorguieva, R., Averill, L. A., Young-McCaughan, S., Shiroma, P. R., Purohit, P., Brundige, A., Murff, W., Ahn, K. H., Sherif, M. A., Baltutis, E. J., Ranganathan, M., D'Souza, D., Martini, B., Southwick, S. M., Petrakis, I. L., Burson, R. R., Guthmiller, K. B., López-Roca, A. L., … Krystal, J. H. (2022). Dose-related effects of ketamine for antidepressant-resistant symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans and active duty military: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled multi-center clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 47(8), 1574–1581. 10.1038/s41386-022-01266-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah, C. G., Sanacora, G., Duman, R. S., & Krystal, J. H. (2018). The neurobiology of depression, ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: Is it glutamate inhibition or activation?. Pharmacology & therapeutics, 190, 148–158. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albott, C. S., Lim, K. O., Forbes, M. K., Erbes, C., Tye, S. J., Grabowski, J. G., Thuras, P., Batres-Y-Carr, T. M., Wels, J., & Shiroma, P. R. (2018). Efficacy, Safety, and Durability of Repeated Ketamine Infusions for Comorbid Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Treatment-Resistant Depression. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 79(3), 17m11634. 10.4088/JCP.17m11634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque, T. R., Macedo, L. F. R., Delmondes, G. A., Rolim Neto, M. L., Almeida, T. M., Uchida, R. R., Cordeiro, Q., Lisboa, K. W. S. C., & Menezes, I. R. A. (2022). Evidence for the beneficial effect of ketamine in the treatment of patients with post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism: official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism, 42(12), 2175–2187. 10.1177/0271678X221116477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander W. (2012). Pharmacotherapy for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder In Combat Veterans: Focus on Antidepressants and Atypical Antipsychotic Agents. P & T: a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management, 37(1), 32–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI]

- Andrade C. (2018). Ketamine for Depression, 6: Effects on Suicidal Ideation and Possible Use as Crisis Intervention in Patients at Suicide Risk. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 79(2), 18f12242. 10.4088/JCP.18f12242 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ashbaugh, A. R., Houle-Johnson, S., Herbert, C., El-Hage, W., & Brunet, A. (2016). Psychometric Validation of the English and French Versions of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). PloS one, 11(10), e0161645. 10.1371/journal.pone.0161645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autry, A. E., Adachi, M., Nosyreva, E., Na, E. S., Los, M. F., Cheng, P. F., Kavalali, E. T., & Monteggia, L. M. (2011). NMDA receptor blockade at rest triggers rapid behavioural antidepressant responses. Nature, 475(7354), 91–95. 10.1038/nature10130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjet, C., Bromet, E., Karam, E. G., Kessler, R. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Ruscio, A. M., Shahly, V., Stein, D. J., Petukhova, M., Hill, E., Alonso, J., Atwoli, L., Bunting, B., Bruffaerts, R., Caldas-de-Almeida, J. M., de Girolamo, G., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Huang, Y., Lepine, J. P., … Koenen, K. C. (2016). The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychological medicine, 46(2), 327–343. 10.1017/S0033291715001981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger, W., Mendlowicz, M. V., Marques-Portella, C., Kinrys, G., Fontenelle, L. F., Marmar, C. R., & Figueira, I. (2009). Pharmacologic alternatives to antidepressants in posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry, 33(2), 169–180. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadabayev, A. R., Joshi, S. A., Reda, M. H., Lake, T., Hausman, M. S., Domino, E., & Liberzon, I. (2020). Low Dose Ketamine Infusion for Comorbid Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Chronic Pain: A Randomized Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Chronic stress (Thousand Oaks, Calif.), 4, 2470547020981670. 10.1177/2470547020981670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskalakis, N. P., Lehrner, A., & Yehuda, R. (2013). Endocrine aspects of post-traumatic stress disorder and implications for diagnosis and treatment. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America, 42(3), 503– 513. 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diazgranados, N., Ibrahim, L., Brutsche, N. E., Newberg, A., Kronstein, P., Khalife, S., Kammerer, W. A., Quezado, Z., Luckenbaugh, D. A., Salvadore, G., Machado-Vieira, R., Manji, H. K., & Zarate, C. A., Jr (2010). A randomized add-on trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant bipolar depression. Archives of general psychiatry, 67(8), 793–802. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore, J., Turnipseed, B., Dwyer, S., Turnipseed, A., Andries, J., Ascani, G., Monnette, C., Huidekoper, A., Strauss, N., & Wolfson, P. (2019). Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy (KAP): Patient Demographics, Clinical Data and Outcomes in Three Large Practices Administering Ketamine with Psychotherapy. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 51(2), 189–198. 10.1080/02791072.2019.1587556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder, A., Costi, S., Rutter, S. B., Collins, A. B., Govindarajulu, U., Jha, M. K., Horn, S. R., Kautz, M., Corniquel, M., Collins, K. A., Bevilacqua, L., Glasgow, A. M., Brallier, J., Pietrzak, R. H., Murrough, J. W., & Charney, D. S. (2021). A Randomized Controlled Trial of Repeated Ketamine Administration for Chronic Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. The American journal of psychiatry, 178(2), 193–202. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20050596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder, A., Parides, M. K., Murrough, J. W., Perez, A. M., Morgan, J. E., Saxena, S., Kirkwood, K., Aan Het Rot, M., Lapidus, K. A., Wan, L. B., Iosifescu, D., & Charney, D. S. (2014). Efficacy of intravenous ketamine for treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry, 71(6), 681–688. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. J., Marmar, C. R., Baker, D. G., Sikes, C. R., & Farfel, G. M. (2007). Randomized, double-blind comparison of sertraline and placebo for posttraumatic stress disorder in a Department of Veterans Affairs setting. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 68(5), 711–720. 10.4088/jcp.v68n0508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green B. (2014). Prazosin in the treatment of PTSD. Journal of psychiatric practice, 20(4), 253–259. 10.1097/01.pra.0000452561.98286.1e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, J., Magruder, K. M., Forsberg, C. W., Kazis, L. E., Ustün, T. B., Friedman, M. J., Litz, B. T., Vaccarino, V., Heagerty, P. J., Gleason, T. C., Huang, G. D., & Smith, N. L. (2014). The association of PTSD with physical and mental health functioning and disability (VA Cooperative Study #569: the course and consequences of posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam-era veteran twins). Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation, 23(5), 1579–1591. 10.1007/s11136-013-0585-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpaz-Rotem I. (2022). Combining neurobiology and new learning: ketamine and prolonged exposure: a potential rapid treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Clinicaltrials.gov NCT02727998.

- Hartberg, J., Garrett-Walcott, S., & De Gioannis, A. (2018). Impact of oral ketamine augmentation on hospital admissions in treatment-resistant depression and PTSD: a retrospective study. Psychopharmacology, 235(2), 393–398. 10.1007/s00213-017-4786-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick, D. G., Resnick, H. S., Milanak, M. E., Miller, M. W., Keyes, K. M., & Friedman, M. J. (2013). National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Journal of traumatic stress, 26(5), 537–547. 10.1002/jts.21848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal, J. H., Abdallah, C. G., Averill, L. A., Kelmendi, B., Harpaz-Rotem, I., Sanacora, G., Southwick, S. M., & Duman, R. S. (2017). Synaptic Loss and the Pathophysiology of PTSD: Implications for Ketamine as a Prototype Novel Therapeutic. Current psychiatry reports, 19(10), 74. 10.1007/s11920-017-0829-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal, J. H., Davis, L. L., Neylan, T. C., A Raskind, M., Schnurr, P. P., Stein, M. B., Vessicchio, J., Shiner, B., Gleason, T. C., & Huang, G. D. (2017). It Is Time to Address the Crisis in the Pharmacotherapy of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Consensus Statement of the PTSD Psychopharmacology Working Group. Biological psychiatry, 82(7), e51–e59. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal, J. H., Sanacora, G., & Duman, R. S. (2013). Rapid-acting glutamatergic antidepressants: the path to ketamine and beyond. Biological psychiatry, 73(12), 1133–1141. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunimatsu, A., Yasaka, K., Akai, H., Kunimatsu, N., & Abe, O. (2020). MRI findings in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI, 52(2), 380–396. 10.1002/jmri.26929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapidus, K. A., Levitch, C. F., Perez, A. M., Brallier, J. W., Parides, M. K., Soleimani, L., Feder, A., Iosifescu, D. V., Charney, D. S., & Murrough, J. W. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of intranasal ketamine in major depressive disorder. Biological psychiatry, 76(12), 970–976. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengvenyte, A., Olié, E., & Courtet, P. (2019). Suicide Has Many Faces, So Does Ketamine: a Narrative Review on Ketamine's Antisuicidal Actions. Current psychiatry reports, 21(12), 132. 10.1007/s11920-019-1108-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, N., Liu, R. J., Dwyer, J. M., Banasr, M., Lee, B., Son, H., Li, X. Y., Aghajanian, G., & Duman, R. S. (2011). Glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists rapidly reverse behavioral and synaptic deficits caused by chronic stress exposure. Biological psychiatry, 69(8), 754–761. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka, R. C., & Nicoll, R. A. (1999). Long-term potentiation--a decade of progress?. Science (New York, N.Y.), 285(5435), 1870–1874. 10.1126/science.285.5435.1870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B. S. (1999). Stress and hippocampal plasticity. Annual review of neuroscience, 22, 105–122. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group PRISMA (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS medicine, 6(7), e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, D., Ross, J., Ashwick, R., Armour, C., & Busuttil, W. (2017). Exploring optimum cut-of scores to screen for probable posttraumatic stress disorder within a sample of UK treatment-seeking veterans. European journal of psychotraumatology, 8(1), 1398001. 10.1080/20008198.2017.1398001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, V. S., & Hiroaki-Sato, V. A. (2018). A brief history of antidepressant drug development: from tricyclics to beyond ketamine. Acta neuropsychiatrica, 30(6), 307–322. 10.1017/neu.2017.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popoli, M., Yan, Z., McEwen, B. S., & Sanacora, G. (2011). The stressed synapse: the impact of stress and glucocorticoids on glutamate transmission. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 13(1), 22–37. 10.1038/nrn3138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, B., Mitrev, L., Moaddell, R., & Wainer, I. W. (2018). d-Serine is a potential biomarker for clinical response in treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder using (R,S)-ketamine infusion and TIMBER psychotherapy: A pilot study. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Proteins and proteomics, 1866(7), 831–839. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2018.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, B., Wainer, I., Moaddel, R., Torjman, M., Goldberg, M., Sabia, M., Parikh, T., & Pumariega, A. J. (2017). Trauma Interventions using Mindfulness Based Extinction and Reconsolidation (TIMBER) psychotherapy prolong the therapeutic efects of single ketamine infusion on post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid depression: a pilot randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover clinical trial. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Trials: Nervous System Diseases, 2(3), 80. 10.4103/2542-3932.211589 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radley, J. J., & Morrison, J. H. (2005). Repeated stress and structural plasticity in the brain. Ageing research reviews, 4(2), 271–287. 10.1016/j.arr.2005.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reul, J. M., & Nutt, D. J. (2008). Glutamate and cortisol--a critical confluence in PTSD? Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 22(5), 469–472. 10.1177/0269881108094617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, C., Jain, R., Bonnett, C. J., & Wolfson, P. (2019). High-dose ketamine infusion for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in combat veterans. Annals of clinical psychiatry : oficial journal of the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists, 31(4), 271–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum, B. O., Cahill, S. P., Foa, E. B., Davidson, J. R., Compton, J., Connor, K. M., Astin, M. C., & Hahn, C. G. (2006). Augmentation of sertraline with prolonged exposure in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of traumatic stress, 19(5), 625–638. 10.1002/jts.20170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytwinski, N. K., Scur, M. D., Feeny, N. C., & Youngstrom, E. A. (2013). The co-occurrence of major depressive disorder among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis. Journal of traumatic stress, 26(3), 299–309. 10.1002/jts.21814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneier, F. R., Neria, Y., Pavlicova, M., Hembree, E., Suh, E. J., Amsel, L., & Marshall, R. D. (2012). Combined prolonged exposure therapy and paroxetine for PTSD related to the World Trade Center attack: a randomized controlled trial. The American journal of psychiatry, 169(1), 80–88. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal, K. H., Maguen, S., Cohen, B., Gima, K. S., Metzler, T. J., Ren, L., Bertenthal, D., & Marmar, C. R. (2010). VA mental health services utilization in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in the first year of receiving new mental health diagnoses. Journal of traumatic stress, 23(1), 5–16. 10.1002/jts.20493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev, A., Liberzon, I., & Marmar, C. (2017). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. The New England journal of medicine, 376(25), 2459–2469. 10.1056/NEJMra1612499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpless, B. A., & Barber, J. P. (2011). A Clinician's Guide to PTSD Treatments for Returning Veterans. Professional psychology, research and practice, 42(1), 8–15. 10.1037/a0022351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiroma, P. R., Thuras, P., Wels, J., Erbes, C., Kehle-Forbes, S., & Polusny, M. (2020). A Proof-of-Concept Study of Subanesthetic Intravenous Ketamine Combined With Prolonged Exposure Therapy Among Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 81(6), 20l13406. 10.4088/JCP.20l13406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J. A., Hernán, M. A., Reeves, B. C., Savović, J., Berkman, N. D., Viswanathan, M., Henry, D., Altman, D. G., Ansari, M. T., Boutron, I., Carpenter, J. R., Chan, A. W., Churchill, R., Deeks, J. J., Hróbjartsson, A., Kirkham, J., Jüni, P., Loke, Y. K., Pigott, T. D., Ramsay, C. R., … Higgins, J. P. (2016). ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 355, i4919. 10.1136/bmj.i4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J. A. C., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G., Blencowe, N. S., Boutron, I., Cates, C. J., Cheng, H. Y., Corbett, M. S., Eldridge, S. M., Emberson, J. R., Hernán, M. A., Hopewell, S., Hróbjartsson, A., Junqueira, D. R., Jüni, P., Kirkham, J. J., Lasserson, T., Li, T., McAleenan, A., … Higgins, J. P. T. (2019). RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 366, l4898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sveen, J., Bondjers, K., & Willebrand, M. (2016). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5: a pilot study. European journal of psychotraumatology, 7, 30165. 10.3402/ejpt.v7.30165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, G. H., Bahji, A., Undurraga, J., Tondo, L., & Baldessarini, R. J. (2021). Efficacy and Tolerability of Combination Treatments for Major Depression: Antidepressants plus Second-Generation Antipsychotics vs. Esketamine vs. Lithium. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 35(8), 890–900. 10.1177/02698811211013579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan, L. B., Levitch, C. F., Perez, A. M., Brallier, J. W., Iosifescu, D. V., Chang, L. C., Foulkes, A., Mathew, S. J., Charney, D. S., & Murrough, J. W. (2015). Ketamine safety and tolerability in clinical trials for treatment-resistant depression. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 76(3), 247–252. 10.4088/JCP.13m08852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrocklage, K. M., Averill, L. A., Cobb Scott, J., Averill, C. L., Schweinsburg, B., Trejo, M., Roy, A., Weisser, V., Kelly, C., Martini, B., Harpaz-Rotem, I., Southwick, S. M., Krystal, J. H., & Abdallah, C. G. (2017). Cortical thickness reduction in combat exposed U.S. veterans with and without PTSD. European neuropsychopharmacology : the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 27(5), 515–525. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda, R., Hoge, C. W., McFarlane, A. C., Vermetten, E., Lanius, R. A., Nievergelt, C. M., Hobfoll, S. E., Koenen, K. C., Neylan, T. C., & Hyman, S. E. (2015). Post-traumatic stress disorder. Nature reviews. Disease primers, 1, 15057 . 10.1038/nrdp.2015.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarate, C. A., Jr, Singh, J. B., Carlson, P. J., Brutsche, N. E., Ameli, R., Luckenbaugh, D. A., Charney, D. S., & Manji, H. K. (2006). A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Archives of general psychiatry, 63(8), 856–864. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoladz, P. R., & Diamond, D. M. (2013). Current status on behavioral and biological markers of PTSD: a search for clarity in a conflicting literature. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 37(5), 860–895. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]