Abstract

Salivary gland cancers are a rare, histologically diverse group of tumors. They range from indolent to aggressive and can cause significant morbidity and mortality. Surgical resection remains the mainstay of treatment, but radiation and systemic therapy are also critical parts of the care paradigm. Given the rarity and heterogeneity of these cancers, they are best managed in a multidisciplinary program. In this review, the authors highlight standards of care as well as exciting new research for salivary gland cancers that will strive for better patient outcomes.

Keywords: cancer, head and neck, multimodality, salivary gland carcinoma, targeted therapy

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF SALIVARY GLAND MALIGNANCIES

Salivary gland malignancies are uncommon, comprising approximately 6%–8% of all head and neck cancers.1 Although wide variations in incidence have been reported around the world, depending on the population studied, salivary gland malignancies occur at an incidence of approximately 1.1 cases per 100,000 individuals in the United States.2 At younger ages, women seem to have a higher prevalence; however, generally speaking, this sex distribution difference plateaus because of an increase in the prevalence of certain malignancies among older men, particularly salivary duct carcinoma (SDC) and metastatic squamous cell carcinoma.2 Among the various histologic types, mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) is the most common primary salivary gland malignancy, followed by adenoid cystic carcinoma (ADCC), and acinic cell carcinoma (AciCC) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Clinicopathologic features of commonly encountered primary salivary gland neoplasms.a

| Histologic entity | Grade | Common locations | Age range | Sex distribution | Outcomes | Histomorphologic features | Ancillary studies | Molecular findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common malignant neoplasms | ||||||||

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) | More often low-grade but can be intermediate-grade or high-grade | Parotid > palate > submandibular gland > minor salivary gland | Wide range, peaks in second decade of life | F:M, ~3:2 | Patients with low-grade MEC have excellent outcomes (92%−100% 5-year survival) vs. those with high-grade MEC (0%−52% 5-year survival): treatment of intermediate-grade tumors may depend on stage (intermediate-grade 5-year survival, 62%−100%) | Admixture of squamoid cells (intermediate and epidermoid type) and mucinous cells; can be cystic or oncocytic; grading by Brandwein. Katabi, AFIP, modified Healey systems; no universally accepted grading system yet | p63-positive, mucicarmine-positive in goblet type cells | CRCT1::MAML2 >> CRTC3::MAML2; rare EWSR1::POU5F1 |

| Acinic cell carcinoma | More often low-grade but can be high-grade | Parotid is most common | Approximately fifth decade of life | F:M, ~1.5:1.0 | Usually good outcomes with low-grade tumors (~90% 20-year survival): local and distant metastases can occur: outcomes appear worse in cases with high-grade transformation | Variable architecture: solid, papillocystic, microcystic, follicular patterns; variable cytology: vacuolated, clear, oncocytic, or large and polygonal with basophilic granules | NR4A3-positive; DOG1 membranous staining. SOX10-positive, mammaglobin negative | t(4;9) most common; enhancers placed upstream of NR4A3-promoting proliferation |

| Carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma (ex-PA) | Usually high-grade (if ductal carcinoma ex-PA) but can also be low-grade (often with myoepithelial carcinoma ex-PA) | Parotid is most common | Sixth or seventh decades of life | Slightly more F than M | Outcome depends on extent of invasion: 5-year overall survival rate ~25%−65% with local or distant metastasis: those with intracapsular carcinoma ex-PA (without invasion) or minimally invasive disease (<4–6 mm invasion beyond PA border) fare better | Carcinoma component is most often high-grade ductal adenocarcinoma (usually salivary duct carcinoma); subset has myoepithelial carcinoma ex-PA (usually low-grade) | Stains depend on carcinoma component: p53, Ki67, androgen receptor can be considered for salivary duct arising in PA; myoepithelial markers for myoepithelial carcinoma: PLAG1 and HMGA2 IHC can be considered for PA component | Often with PLAG1 and HMGA2 fusion genes, similar to PA: additional genetic instability, copy-number alterations; TP53 mutation; HER2 amplification |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | Usually low-grade but can show high-grade transformation | Major salivary glands > minor salivary glands | Approximately fifth decade of life | F:M, ~1.5:10 | Long clinical course with frequent recurrences and distant metastases, with approximately 50% 10-year overall survival; high-grade, NOTCH 1 mutational status, age, advanced stage, margin status can affect outcomes | Infiltrative, biphasic salivary gland malignancy; variable architecture: solid, tubular, cribriform; characteristic sharp, punched-out spaces with basophilic matrix; tumor cells have scant cytoplasm, angulated hyperchromatic nuclei | p40, smooth muscle actin-positive in myoepithelial cells. KIT-positive and cytokeratin 7 (CK7)-positive in ductal cells; MYB IHC usually diffuse | MYB::NFIB, MYBL1::NFIB translocations; NOTCH alterations seen with solid type adenoid cystic carcinoma; wide mutational array affecting several pathways |

| Secretory carcinoma | Usually low-grade but can show high-grade transformation | Parotid > oral cavity and submandibular gland | Adults, wide age range, around fourth to fifth decade of life | F ≈ M | Usually indolent: lymph node metastasis in ~25%: worse outcomes with high clinical stage and high-grade transformation | Circumscribed/infiltrative with variable solid/cystic, follicular, papillocystic architectures: occasional perineural invasion | CK7-positive, S 100-positive, mammaglobin-positive, p63/p40-negative | ETV6::NTRK3 fusions are most common |

| Salivary duct carcinoma | High-grade | Parotid is most common | Older males in sixth to seventh decade of life | M > F | Poor prognosis with high risk of recurrence, regional and distant metastasis: 5-year survival <45% | Resembles breast high-grade ductal carcinoma; oncocytic cells with nuclear pleomorphism and prominent nucleoli, comedo-type necrosis, abundant mitoses; sarcomatoid transformation, rhabdoid features, micropapillary features may be seen: extensive perineural and angiolymphatic invasion can be seen | Androgen receptor-positive. HER2-positive; estrogen receptor-negative and progesterone receptor-negative | HER2 gene amplification. PI3K alterations, complex genetic profile |

| Polymorphous adenocarcinoma | Usually low-grade but can show high-grade transformation | Palate is most common followed by other oral cavity sites | Wide range, most common in fifth to seventh decades of life | F:M, ~2.0:1.0 | Overall prognosis is excellent; low risk of local recurrence and distant metastasis but can occur; cribriform/papillary architecture, high-grade transformation, large-nerve perineural and angiolymphatic invasion, and PRKD fusions associated with aggressive behavior | Infiltrative, monophasic, uniform malignancy with open chromatin, oval nuclei, and occasional small nucleoli; arranged in trabecular, microcystic, cribriform, or papillary patterns: perineural invasion is common | CK7-positive, S100-positive, mammaglobin-negative, p63-positive. p40-negative | PRKD1 alterations (hot-spot E170D mutation in conventional type; PRKD1 rearrangements in cribriform/papillary type) |

| Intraductal carcinoma (or intercalated duct carcinoma) | Usually low-grade but apocrine type can be low-grade or high-grade | Parotid is most common | Wide age range of presentation | F ~ M | Generally excellent outcomes after complete resection if all in situ; frankly invasive carcinomas and ex-intraductal carcinoma can show worse outcomes | Four types: intercalated, small amphophilic cells with oval nuclei: oncocytic, abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with enlarged nuclei and prominent nucleoli: apocrine, bubby eosinophilic cytoplasm and apical snouting; and mixed, hybrid of other types | Myoepithelial cells highlighted by p63, calponin, smooth muscle actin; depending on subtype, can be androgen receptor-positive and HER2-positive (apocrine) or S100-positive and mammaglobin-positive (oncocytic, intercalated, and hybrid types) | Oncocytic type, TRIM33::RET or B-Raf V600E: intercalated type. NCOA4::RET; apocrine type, PI3K alterations: mixed types, mixed/hybrid type, TRIM27::RET |

| Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma | Usually low-grade; high-grade transformation can occur | Parotid and submandibular glands > other sites | Sixth or seventh decades of life | Slight F > M | Indolent course but can locally recur; local and distant metastases are rare; high-grade transformation is more aggressive | Biphasic malignancy with multinodular growth pattern; inner ductal cells: myoepithelial cells are abundant; clear cytoplasm | Ductal cells are positive for CK7; myoepithelial cells are positive for smooth muscle actin. calponin, and p40/p63 | HRAS alterations |

| Basal cell adenocarcinoma | Grading is not typically reported | Very rare, parotid | Sixth or seventh decades of life | F ≈ M | Local recurrence can occur in approximately one third of cases but outcomes usually excellent after surgery with clear margins: local and distant metastases are rare | Infiltrative, biphasic, basaloid malignancy in solid, tubular, trabecular, or membranous architectural patterns; peripheral palisading of nuclei; perineural and vascular invasion can occur | Positive for p40, calponin. and smooth muscle actin in myoepithelial cells; CK7-positive in ductal cells | A subset may arise from membranous type (CYLD alterations); molecular data are limited; complex alterations, including PI3K |

| Hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma | Usually low-grade; high-grade transformation can occur | Minor salivary gland in palate, base of tongue most common sites | Fifth to eighth decades of life | F > M | Usually good outcomes with low-grade cases: local recurrence and lymph node metastases can occur; distant metastases and death rare; high-grade transformation can be more aggressive | Clear/eosinophilic cells arranged in nests, trabeculae, or cords in a dense hyalinized or desmoplastic stroma; high-grade transformation with necrosis, marked nuclear atypia. and significant mitotic activity can occur | CK7-positive, p63-positive, negative for myoepithelial markers | EWSR1::ATF1 fusion |

| Microsecretory carcinoma | Low-grade but <30 cases reported to date | Minor salivary gland tissue in palate and buccal mucosa most common sites | Wide age range of presentation, average age In the fourth decade of life | Slight F > M | Excellent outcomes with no reported recurrences or metastases | Microcystic-predominant monotonous, intercalated, duct-like tumor cells with attenuated, eosinophilic- to dear cytoplasm, basophilic secretions, subtle infiltrative growth in a fibromyxoid background | CK7-positive, S100-positive, mammaglobin-negative. p63-positive, p40-negative | MEF2C::SS18 fusion |

| Mucinous adenocarci noma | Usually low-grade | Intraoral minor salivary gland sites | Peaks in eighth decade of life | F ~ M | Nodal metastases can occur at presentation; papillary form typically indolent: colloid or signet-ring patterns are associated with risk of recurrence and metastases | Variable architecture: papillary, colloid, or signet ring forms, but can be mixed: abundant, mucinous-type epithelium | Positive for CK7 and NKX3.1; negative for CK20, CDX2, p63. p40, TTF1, S100. calponin. smooth muscle actin. and androgen receptor | Recurrent AKT1 p.E17K alteration and can have concurrent TP53mutation |

| Sclerosing microcystic adenocarcinoma | Low-grade | Intraoral minor salivary gland sites: tongue, lip mucosa, floor of mouth, and buccal mucosa | Fifth to eighth decades of life | F > M | Excellent, without evidence of locoregional recurrence or distant metastases; surgical excision is treatment of choice, and adjuvant radiation can be considered in the appropriate context (e.g., positive margins) | Infiltrative, biphasic ducts/tubules with an attenuated, myoepithelial cell layer within dense, sclerotic stroma; perineural invasion is common | CK7, p40, and p63 highlight a biphasic population | NA |

| Common benign neoplasms | ||||||||

| PA | Low-grade (benign) | Parotid > submandibular > palate >> sublingual gland >> other oral cavity sites | Wide range, average age in fourth decade of life | F:M, ~1.4:1.0 | Excellent if completely excised; risk of recurrence associated with incomplete excision, young age (30 years or younger) and increased mitotic activity | Well demarcated, biphasic salivary gland neoplasm with variable epithelial and myoepithelial morphology and architecture in a chondromyxoid matrix; filopodial extension can occur | CK7, p40, and p63 highlight a biphasic population; positive for PLAG1 or HMGA2 immunostain | PLAG1 and HMGA2 rearrangements are most common |

| Warthin tumor | Low-grade (benign) | Parotid is most common (associated with cigarette smoking) | Seventh decade of life | M > F | Complete excision is usually curative | Papillary-cystic structures lined by oncocytic, bilayered epithelium with lymphoid stroma and germinal centers | Not routinely done | Not routinely done; may have clonal alterations |

| Basal cell adenoma | Low-grade (benign) | Parotid is most common followed by submandibular gland | Older adults, fifth decade of life or older | Slight F > M | Excellent prognosis with very low recurrence rate: exception is membranous type, with ~25% risk of recurrence | Variable morphology: solid, trabecular, tubular, and membranous patterns: basaloid cells with scant cytoplasm with peripheral palisading: membranous pattern with hyaline material surrounding nests | CK7, p40, and p63 highlight a biphasic population; patchy nuclear beta-catenin and nuclear LEF1 staining | Beta-catenin alterations; membranous type may be associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome (CYLD alterations) |

| Oncocytoma | Low-grade (benign) | Parotid is most common | Sixth to eighth decades of life | F ~ M | Excellent outcomes | Well circumscribed lesion of oncocytes with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, central nucleus, and prominent nucleolus | p63 highlights basal cell population | NA |

| Myoepithelioma | Low-grade (benign) | Parotid is most common followed by hard/ soft palate | Wide age range, third decade of life | F ~ M | Usually excellent: may rarely recur if incompletely excised; if long-standing or multiply recurrent, then may (exceptionally rarely) undergo malignant transformation | Variable morphology: plasmacytoid. spindle, epithelioid, hyaline, or clear cell features | Positive for CK7 and myoepithelial markers: calponin, S100, smooth muscle actin | NA |

| Sclerosing polycystic adenoma (SPA) | Low-grade (generally benign) | Parotid is most common | Wide age range, fourth decade of life | F:M, 3.0:2.0 | Usually good: recurrences can occur, and exceptionally rare cases of in situ and invasive carcinomas ex-SPA have been documented | Circumscribed lobular architecture, irregular distribution of ducts with eosinophilic secretions/foamy macrophages and acini with intracytoplasmic granules; stroma may show fibrosis, fibroadipose tissue and lymphoid aggregates | Periodic acid-Schiff (diastase-resistant) and GCDFP-15-positive staining in acini: positive for progesterone receptor and CK AE1/AE3 in ductal cells; myoepithelial cells: p40, p63, calponin. smooth muscle actin | Genetic alterations in PI3K pathway most common: PTEN, PIK3CA. PIK3R1 |

Abbreviations: AFIP, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; F, female; F;M, female to male ratio; IHC, immunohistochemistry; M, male; NA, not available; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase.

This is not a comprehensive list because the number of entities continues to increase with molecular testing; commonly encountered neoplasms and a few newer entities are mentioned here.

The development of salivary gland neoplasms is multifactorial, involving complex environmental and genetic interactions.3 lonizing radiation, chemical exposure, obesity, autoimmune disorders, and viral infections (such as Epstein-Barr virus in lymphoepithelial carcinoma) have been implicated, although direct links have yet to be established. Mutations in tumor suppressors/oncogenes and chromosomal translocations can also promote the development of salivary gland neoplasms (both benign and malignant).

ANATOMY OF THE SALIVARY GLAND

The salivary gland unit is composed of luminal ductal cells and is surrounded by abluminal myoepithelial cells or noncontractile basal cells, depending on the duct caliber.4 The composition of the acinar component depends on the anatomic site.5 The parotid gland is composed primarily of serous acinar cells, the submandibular gland is composed of an admixture of serous and mucinous cells, and the sublingual gland/minor salivary glands are composed entirely of mucinous cells. Malignancies can arise from these various cell types, and a few commonly encountered entities are discussed below and in Table 1.3,6 A general rule of thumb is that, the smaller the gland, the more mucinous cells and the higher likelihood of malignancy associated with the site.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The most common presenting symptom of salivary malignancy is a painless parotid or neck mass. Sublingual gland malignancies may present at late disease stage as a mass in the floor of mouth. The presence of pain, a rapidly growing mass, facial weakness, or lingual weakness/paresthesias (in the case of sublingual tumors) are ominous signs that usually indicate high-grade malignancy.

It is important to note that the differential diagnoses of a swelling/mass lesion is broad. For this review, we focused on features of key primary salivary gland neoplasms; however, salivary gland involvement by nonneoplastic tumor-like conditions (i.e., nodular oncocytic hyperplasia, necrotizing sialometaplasia, salivary duct cyst, among others), mesenchymal neoplasms, hematolymphoid processes, direct extension of cutaneous malignancies, and metastases can also be observed and should be considered in the differential, depending on the clinical history and presentation, radiologic findings, and laboratory data.6

DIAGNOSIS OF SALIVARY GLAND CARCINOMAS

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is commonly used in the initial evaluation of a salivary gland lesion for several reasons. First, it is a rapid and minimally invasive technique with high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity.7,8 On-site evaluation capabilities can provide useful information, including whether the lesion represents a primary salivary gland tumor or metastasis (in the appropriate clinical context) and whether the lesion is high-grade or low-grade, which can help with surgical planning. Second, FNAs enable the collection of sufficient material to triage for appropriate ancillary studies, including for immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry.9,10 Finally, in patients who have unresectable disease or are recommended to proceed with primary systemic therapy, cytologic material can be used for molecular studies to identify potential targetable alterations.

The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology was established in 2018 for the standardized reporting of salivary gland cytology findings.10 The six-tiered system consists of nondiagnostic, nonneoplastic, atypia of undetermined significance, benign neoplasm, salivary gland neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential, suspicious for malignancy, and malignant. Each category has an associated risk of malignancy based on aggregated data from multiple institutions, which can help guide clinicians in making management decisions (Table 2). The criteria have been reviewed elsewhere in greater detail.11–13

TABLE 2.

The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology: Diagnostic categories, associated risk of malignancy, and suggested management.

| Diagnostic category | Risk of malignancy | Suggested management |

|---|---|---|

| Nondiagnostic (category I) | 15% | Clinical, radiologic correlation or repeat fine-needle aspiration |

| Nonneoplastic (category II) | 11% | Clinical and radiologic follow-up |

| Atypia of undetermined significance (category III) | 30% | Repeat fine-needle aspiration or surgery |

| Neoplasm: Benign (category IVa) | <3% | Conservative surgery or clinical follow-up |

| Salivary gland neoplasm of undetermined malignant potential (category IVb) | 35% | Surgery with intraoperative frozen consultation to determine extent of surgery |

| Suspicious for malignancy (category V) | 83% | Surgery with intraoperative frozen consultation to determine extent of surgery |

| Malignant (category VI) | 98% | Surgery or systemic therapy depending on the lesion |

Although FNA cytology can be helpful to guide management, particularly in cases that are classified as nonneoplastic, benign neoplasm, and malignant, indeterminate lesions (classified as atypia of undetermined significance, salivary gland neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential, or suspicious for malignancy) that cannot be further resolved on ancillary testing may require surgical evaluation with intraoperative frozen consultation.10 The most important challenge is to determine whether the lesion is low-grade or high-grade or if it is a certain histologic type (i.e., ADCC), because this can drive the extent of surgery, most notably the decision to include or omit a neck dissection. Sampling representative areas that appear distinct within the tumor may provide insight into whether there are high-grade features, including tumor necrosis, marked nuclear atypia, and increased mitotic activity.14 Ultimately, if a lesion is encapsulated/well demarcated, then the evaluation of invasion will require submission of the entire periphery for histologic examination.

PATHOLOGIC ANALYSIS OF THE SURGICALLY EXCISED TUMOR

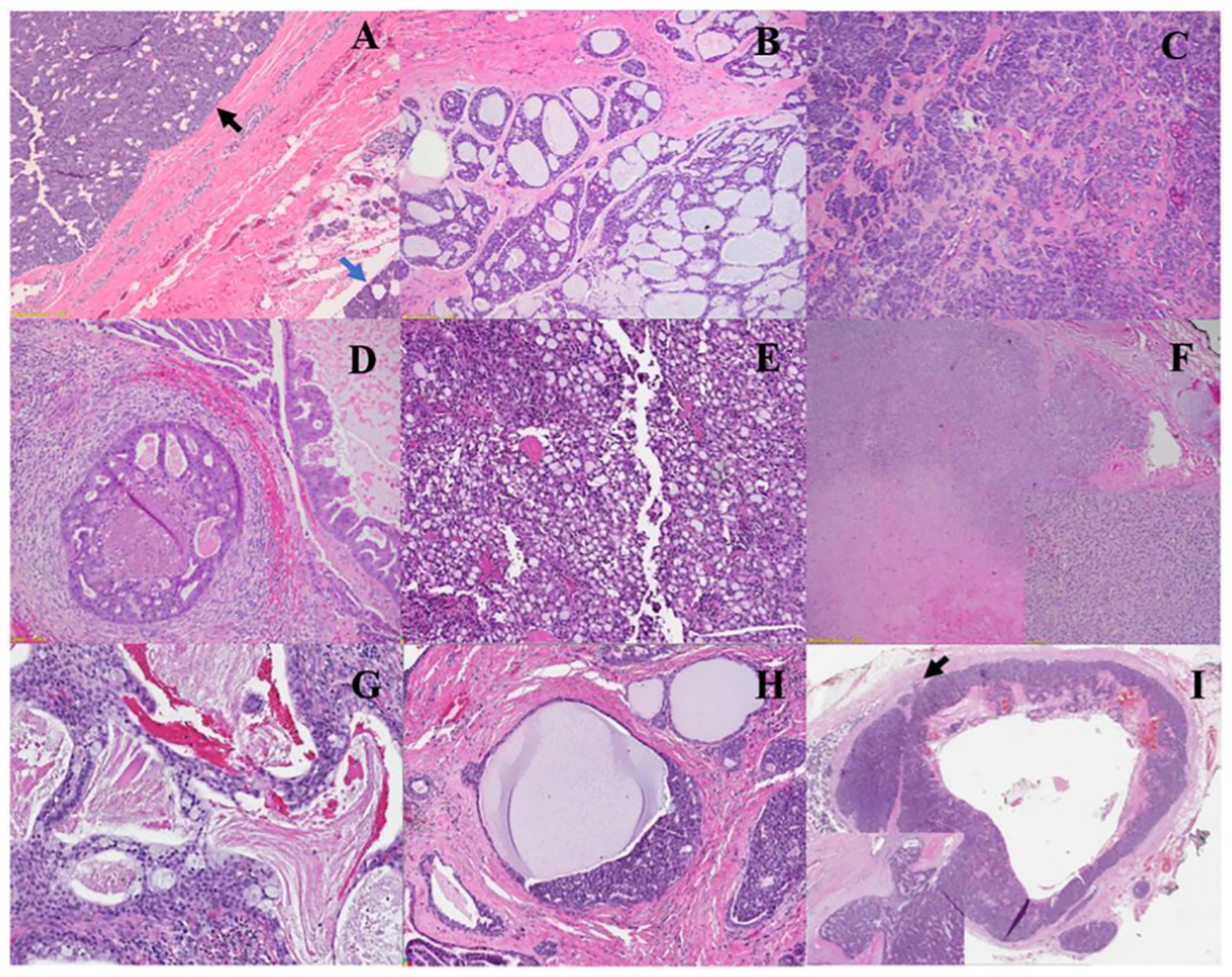

A morphologic pattern-based approach, such as establishing a biphasic or monophasic population, and broadly categorizing the lesion as basaloid, oncocytoid, cystic/secretory/mucinous, or solid-nested/spindled can help focus the differential diagnosis and enable the selection of immunohistochemistry for classification15 (Figure 1). Challenging cases with significant morphologic or immunohistochemical overlap may require molecular studies for definitive classification. Benign salivary gland neoplasms (such as pleomorphic adenoma [PA], Warthin tumor, basal cell adenoma, and oncocytoma) are far more common, and some details are provided at the end of Table 1, but these are not the primary focus of this review.

FIGURE 1.

Representative histologic images of commonly encountered salivary gland malignancies. (A) Acinic cell carcinoma (black arrow indicates the tumor; blue arrow, normal parotid tissue), (B) adenoid cystic carcinoma, (C) polymorphous adenocarcinoma, (D) salivary duct carcinoma, (E) secretory carcinoma, (F) carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenocarcinoma (inset shows low-grade myoepithelial carcinoma component), (G) mucoepidermoid carcinoma, low-grade, (H) intraductal carcinoma, and (I) basal cell adenocarcinoma (black arrow and inset show focus of border invasion with associated desmoplastic stromal response). All glass slides are stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and images were captured from digital scanned slides or directly from the slide.

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

MEC represents the most common primary salivary gland malignancy in both the pediatric and adult populations, occurring most commonly in the parotid, followed by the submandibular and sublingual glands. MECs can occur over a wide age range, with a mean age of 45 years and a female predilection of 1.1–1.5:1.0.

Histopathologic features

The cell types comprising an MEC include mucous-producing cells (mucocytes), intermediate cells, and squamoid cells. These tumors can vary in terms of the amount of cystic or solid components, and they generally lack keratinization. Several histologic variants have been described, including clear cell, oncocytic, sclerosing, Warthin-like, ciliated, spindle cell, and mucoacinar types.

MEC is graded as low-grade, intermediate-grade, or high-grade based on histologic parameters and depending on the grading system used (Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Brandwein, or modified Healey) used. The Armed Forces Institute of Pathology system uses fewer histologic parameters but tends to assign a lower grade to more aggressive tumors, whereas the Brandwein system tends to upgrade tumors more often. The modified Healey and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center grading systems use several qualitative parameters and fall in the middle, but these criteria are not well defined. To date, there is no universal grading system for MEC. Histologically, low-grade MECs tend to be well circumscribed/mostly cystic with abundant mucocytes, intermediate-grade MECs have more solid areas, and high-grade MECs tend to be infiltrative with significant mitotic activity, necrosis, nuclear pleomorphism, angiolymphatic, bone, and perineural invasion.

The squamoid populations in MECs are positive for squamous markers p40/p63 and the mucocytes are positive with the mucin stain. MECs are negative for SOX10/S100 (myoepithelial markers). MAML2 rearrangement is specific for MEC, which can be detected with fluorescence in situ hybridization; however, molecular confirmation is necessary.

Outcomes

The 5-year overall survival rates are 90%, 86%, and 55% for low-grade, intermediate-grade, and high-grade MEC, respectively.3,6 Advanced stage, age, male sex, high-grade tumor, and a positive margin are associated with lower overall and disease-free survival.

Adenoid cystic carcinoma

ADCC comprises approximately 25% of all primary salivary gland carcinomas and occurs in both major and minor salivary glands. ADCC is slightly more frequent in women, with a median age of presentation at around the sixth decade of life.

Histopathologic features

On histology, ADCC is an infiltrative, basaloid, biphasic neoplasm composed of ductal cells and myoepithelial cells. The myoepithelial cells have clear cytoplasm with small, hyperchromatic, angulated nuclei, whereas the ductal cells have more eosinophilic cytoplasm. ADCCs can show tubular, cribriform, or solid architectural patterns. The cribriform pattern has microcystic spaces that can contain a hyaline or mucoid basement membrane-type material. ADCCs are commonly associated with perineural invasion.

Immunohistochemistry will highlight the biphasic epithelial and myoepithelial components with cytokeratin 7/KIT and p40/p63/calponin, respectively. MYB overexpression occurs in most ADCCs and can lend support to the diagnosis. However, the most specific test for ADCC is the identification of either MYB∷NFIB or MYBL1∷NFIB translocations with fluorescence in situ hybridization or molecular testing. NOTCH1 alterations are enriched in the more aggressive solid variant of ADCC.

Outcomes

ADCC has a long, progressive clinical course with multiple recurrences and, ultimately, a fatal outcome. The solid variant and high-grade transformation are associated with worse outcomes. The reported 10-year overall survival and recurrence-free survival rates are 50% and 60%, respectively.3,6

Acinic cell carcinoma

AciCC is composed of malignant acinar cells with variable degrees of differentiation. Because of the classification of several secretory carcinomas (SCs) as AciCCs before molecular clarification, the precise incidence is unclear, but it is considered to be the second most common salivary gland malignancy (approximately 12% of all epithelial salivary gland malignancies). The parotid is the most common site, followed by submandibular and minor salivary gland sites. AciCC occurs over a wide age range, often in the fourth to fifth decades of life, and shows a 1.5:1.0 female:male distribution ratio.

Histopathologic features

AciCCs can have variable architecture, including solid, microcystic, follicular, and papillary-cystic growth patterns. Tumor-associated lymphoid proliferation can be prominent in the periphery. AciCCs can have serous acinar cell (with basophilic zymogen granules), intercalated ductal phenotype, vacuolated, nonspecific glandular, oncocytic, or clear cell appearances, with ill-defined cell borders and small nuclei. High-grade transformation, depicted by solid growth, necrosis, nuclear pleomorphism, and increased proliferative activity, can be noted in conjunction to low-grade areas. AciCCs with high-grade transformation can exhibit perineural and lymphovascular invasion.

Confirmatory immunostains typically include NR4A3, SOX1O, and DOG1 in low-grade cases. Nuclear NR4A3 expression is generally maintained in AciCCs with high-grade transformation, whereas SOX1O, DOG1 and S100 are less consistent. Molecular testing can be helpful in identifying the NR4A3 rearrangement in challenging cases.

Outcomes

The 5-year and 10-year overall survival is >90% for low-grade AciCC, whereas it decreases to approximately 27% for patients with AciCC demonstrating high-grade transformation. A reduced overall survival of approximately 22% is also seen in patients who have AciCC with distant metastases.3,6

Secretory carcinoma

SC occurs over a wide age range, often in the fourth to fifth decade of life, and with equal distribution among men and women. The most common anatomic site of presentation for SC is the parotid, and sites in the oral cavity and submandibular gland are less frequent.

Histopathologic features

SC is most often low-grade and can either be well circumscribed or infiltrative. Architecturally, this tumor can demonstrate variable cystic/solid, tubular, follicular, or papillocystic patterns with eosinophilic to granular/vacuolated cytoplasm, small uniform nuclei, and dense luminal secretions.

SC shows a distinct immunoprofile with S100, SOX1O, and mammaglobin positive staining, whereas DOG1 and NR4A3 (shown in AciCC) are negative. Moreover, SC does not show p40/p63 myoepithelial staining. If needed, ETV6 or RET rearrangements can be demonstrated through molecular testing.

Outcome

Most SCs are low-grade, with indolent behavior and good outcomes (approximately 95% and 90% 5-year and 10-year overall survival, respectively), but can demonstrate lymph node/distant metastases in approximately 25% of patients. Advanced clinical stage is a reported adverse prognostic factor. In the limited data available, high-grade transformation was associated with worse outcomes (with an approximately 5.5-fold hazard ratio).3,6,16,17

Carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma

Carcinoma ex-PA (CXPA) accounts for roughly 12% of all salivary gland malignancies, with most occurring in the parotid gland and arising from a preexisting/recurrent PA. Patients are usually in the sixth or seventh decade of life, and there is a slight predilection for women.

Histopathologic features

Carcinomas arising from the ductal component tend to be high-grade, most often being SDC ex-PA, whereas those arising from the myoepithelial component tend to be low-grade. Rare cases of carcinosarcoma with both malignant epithelial and sarcomatous components have been reported. Depending on the extent of invasion beyond the PA border, CXPAs can be classified as intracapsular (carcinoma is confined within the PA border), minimally invasive (carcinoma invades <4–6 mm beyond the PA border), or invasive (≥6 mm beyond the PA border).

Immunohistochemistry for PLAG1 or HMGA2 followed by confirmation with fluorescence in situ hybridization testing can help identify a PA component. The presence of androgen receptor (AR) staining in a ductal carcinoma arising from a PA would be in keeping for an SDC ex-PA. Additional complex molecular alterations in TP53, HRAS, PIK3CA, and/or amplification of EGFR or MYC may occur in the course of tumor progression.

Outcomes

Patients with CXPA have an overall 5-year survival ranging from 25% to 75%, which varies in part because of the better outcomes seen with minimally invasive and intracapsular CXPAs compared with the invasive type. Reported adverse prognostic factors include large tumor size (>4 cm), lymph node metastases, and distant metastasis. In general, CXPAs behave aggressively, with up to 70% showing local and/or distant recurrences.3,6

Salivary duct carcinoma

SDC is a high-grade malignancy resembling its mammary apocrine carcinoma counterpart. SDCs account for up to 10% of all salivary gland malignancies, commonly affecting men in the sixth or seventh decade of life.

Histopathologic features

SDCs are highly infiltrative, with complex architecture and comedo-type necrosis. Tumor cells have abundant eosinophilic/apocrine cytoplasm with marked nuclear pleomorphism and prominent nucleoli. Perineural and angiolymphatic invasion are frequent. A subset may arise from a preexisting PA. Histologic variants, including sarcomatoid transformation with spindle cells and heterologous differentiation, mucin-rich, basal-like, micropapillary, oncocytic, and rhabdoid subtypes, have been reported but are typically seen with a conventional SDC component.3,6

SDCs are most often positive for AR, Her2/Neu, and cytokeratin 7 and negative for SOX1O and S100. Common molecular alterations include TP53 (55%), HRAS (23%), PIK3CA (23%), and amplification of ERBB2 (35%). A small subset of SDCs may harbor PTEN or BRAF alterations. If arising in the context of a PA (i.e., SDC ex-PA), then HMGA2 or PLAG1 alterations can be identified.

Outcomes

SDC is an aggressive malignancy with locoregional and distant metastases. Overall, outcomes are poor, with reported 5-year and 10-year disease-specific survival rates of approximately 64% and 56%, respectively.3,6,18

All of the aforementioned entities, including other less common entities not discussed here, are detailed in Table 1. It must be noted that the portfolio of salivary gland neoplasms continues to expand with increased use of molecular testing, and the current list is not comprehensive.

STAGING OF SALIVARY GLAND NEOPLASMS

For major salivary glands (i.e., parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands), the eighth edition the American Joint Cancer Committee tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging is prognostic.19 The general principles for the T category staging involve size of the tumor, the presence or absence of extraparenchymal extension, and the extent of involvement of adjacent structures. In the absence of extraparenchymal extension, defined as clinical and/or macroscopic evidence of extension beyond salivary gland parenchyma, tumor size cutoffs of 2 and ≤4 cm define T1 and T2, respectively. Of note, microscopic extraparenchymal extension alone does not warrant the upstaging of tumor size. At >4 cm or in the presence of grossly identifiable extraparenchymal extension, the tumor is classified as T3. Should the tumor involve proximal structures, including skin, mandible, ear canal, and/or facial nerve, it is staged as T4a; whereas, with more extensive spread to involve the pterygoid plates or skull base or to encase the carotid artery, it is staged as T4b. The nodal N category depends on a combination of laterality of the involved nodes, metastatic deposit size cutoffs of 3 or 6 cm, and the presence of extranodal extension. The presence of distant metastases would lead to an M1 classification.

In the context of minor salivary glands in other sites, including oral cavity, sinonasal tract, and trachea, the current recommendation is to apply site-specific TNM staging protocols using a combination of tumor size and anatomic structures involved.3

Surgical considerations

Adequate surgical resection is the most effective form of treatment for salivary gland cancers (SGCs). However, the extent of surgery for salivary gland carcinoma is one of the most widely debated topics in head and neck surgical oncology, particularly as it relates to the extent of node dissection. Reconstructive techniques for contour or skin defects and facial nerve deficits have progressed in recent years and have been extensively reviewed elsewhere.20–27 We review general surgical principles of salivary gland malignancies here.

Extent of resection for the primary tumor

For submandibular gland, sublingual gland, or minor salivary gland carcinomas, complete resection is recommended, with a generous margin whenever possible. Most parotid tumors arise within the superficial lobe, and these tumors are often in direct contact with the facial nerve. The general consensus among head and neck surgeons, which is supported in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, is to preserve the facial nerve whenever a dissection plane can be established between the nerve and the tumor.28,29 It is also established that the facial nerve or some of its branches should be sacrificed in the event of preoperative facial weakness or gross invasion/engulfment by the tumor.28,29 For primary salivary malignancies, there are no strong data to suggest that oncologic outcomes are improved by performing a total parotidectomy or a radical parotidectomy (including facial nerve resection) for tumors in the superficial lobe without gross nerve involvement.30,31 Depending on the extent of the tumor, resection of the lateral temporal bone, masseter muscle, and/or mandible may be required to achieve an adequate resection.28

ROLE OF ELECTIVE NECK DISSECTION FOR CLINICALLY NODE-NEGATIVE NECK

When the neck is clinically staged as NO based on examination and imaging, the decision to perform elective neck dissection is largely based on the specific tumor grade and histology, in addition to the primary site. In minor salivary malignancies, elective neck dissection may improve regional disease control.32,33 For carcinoma of the major salivary glands, elective neck dissection should be considered for T3/T4 tumors or high-grade histology.29,34,33 A review of >20,000 cases of parotid cancer in the National Cancer Database showed a high incidence of occult nodal metastasis in high-grade malignancies, including MEC, AciCC, ADCC, and adenocarcinoma, with the highest incidence of occult metastasis seen in SDC.35 The authors recommended elective neck dissection for high-grade tumors of those histologic subtypes versus observation for low-grade tumors.35 A systematic review and meta-analysis of elective neck dissection for salivary malignancies reported similar results based on high-grade histology and T3/T4 tumors.36 Although this information is certainly useful for patient counseling and surgical planning, many tumors do not fit neatly into high-grade/low-grade categories. Furthermore, the histologic grade and subtype may be unclear based on FNA biopsy or even frozen section.37 Lymphovascular invasion is also associated with occult metastases,38 but this also may not be appreciated at the time of surgery. Thus the surgeon must often make a judgment call based on the available imaging and intraoperative findings.

If the decision has been made to perform elective neck dissection, the extent of dissection must be determined. It is well established that the most likely area of spread for parotid cancers is to levels II and III; submandibular, sublingual, and minor salivary cancers often spread to levels I-III.33,34,37–41 External jugular nodes, another frequent area of nodal spread, are also typically resected. The decision to dissect levels I, IV, and V for parotid cancers is a topic of ongoing debate. Some authors have argued that dissection of level I has already been partially completed after parotidectomy and adds little additional morbidity; similarly, dissection of level IV is not much more extensive once levels II and III have been dissected.37 Occult metastases in level V are very unlikely in the absence of clinically evident nodes elsewhere,42 and a level V dissection may result in significant morbidity, which often results from stretch injury to the spinal accessory nerve. As such, some surgeons prefer to avoid this by limiting their level V dissection to removal of level Vb just behind the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Of note, there is no strong evidence that elective neck dissection improves survival outcomes for salivary cancers.34,37

EXTENT OF NECK DISSECTION FOR PATIENTS WITH CLINICALLY NODE-POSITIVE DISEASE

Although neck dissection is recommended when clinically involved nodes are seen on physical examination or imaging, the extent of dissection in this situation is controversial. Most experts on this have advocated for selective neck dissection including levels II-IV or I-IV, depending on the primary site.33,34 However, others have advocated for a comprehensive (levels I-V) neck dissection.41,43 One study demonstrated that 60% of patients undergoing neck dissection with clinically evident anterolateral neck disease also had occult nodal metastases in level V.42 However, this was a single-institution, retrospective study, and it is unclear whether these patients could have been adequately treated with adjuvant radiotherapy. It is notable that no regional recurrences were seen in patients who did not undergo level V dissection.42

Reconstructive considerations

There are three components in the consideration of reconstruction after parotid malignancy extirpation; (1) restoration of volume, (2) cutaneous reconstruction to create a low-tension closure, and (3) facial reanimation procedures for any neural sacrifice.

First, restoration of volume is indicated in both benign and malignant cases and can be tackled in a variety of ways. For the patient with a relatively small intraparenchymal defect, with preservation of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system and subcutaneous tissue, either no reconstruction is needed or a small fat graft can be used, depending on the skin thickness and aesthetic goals of the patient. Typically, younger patients with slimmer facial skin will benefit the most from fat grafting in this scenario. Fat grafting is an excellent reconstruction option for volume defects because it resists infection, remains supple, has no foreign body reaction, and will grow with the patient in the pediatric population.44 Dermal fat grafting has the additional advantage of resisting unpredictable reabsorption, which is common with standard fat grafting45–47 If the superficial musculoaponeurotic system and subcutaneous tissue are excised to achieve an oncologic margin, the necessity for volume reconstruction increases. Adjuvant radiation will certainly cause more resorption of grafts, but this is variable and depends on how quickly the graft vascularizes, which is a function of technique of harvest and vascularity in the wound bed. Ultimately, the decision to perform volume reconstruction can be readily assessed intraoperatively by the surgeon by comparing facial symmetry after tumor extirpation. Any type of fat grafting involves a donor site (typically thigh or abdomen), with associated donor site complications, and also requires a longer time for drain placement to prevent seroma. Fat grafting has also been shown to decrease Frey syndrome and sialocele, so it is useful to counsel patients on these points when discussing risks and benefits.

Other options for volume reconstruction include vascularized options, such as the superiorly based sternocleidomastoid flap (based off the occipital artery), the temporoparietal fascia flap (based off the superficial temporal artery), the temporalis flap (based off the internal maxillary artery), and the submental island musculodermal flap. The sternocleidomastoid flap suffers from issues with muscle atrophy, variable devascularization based on the extent of neck dissection, and creating limited neck mobility. The temporoparietal fascia flap is limited by minimal volume reconstruction with an extended temporal incision and potential injury to the frontal branch of the facial nerve. The temporalis flap causes an extended incision with temporal wasting and muscle atrophy and has fallen out of use given this defect. Although the submental flap is an excellent option, it involves an extended incision, limits neck mobility to some degree, and adds operative time. Vascularized flaps have the great advantage of resisting resorption in the postoperative period, especially with the addition of adjuvant radiation. A preoperative discussion with the patient on their aesthetic goals in the context of expected adjuvant therapy is the most prudent approach in deciding what, if anything, to do for restoration of volume.

Cutaneous reconstruction is indicated when extirpation of tumor leaves a skin defect that will be under excessive tension if closed primarily. If a tumor reaches the subcutaneous tissue, skin will typically need to be removed to ensure a good margin and healthy skin in the extirpated bed. Furthermore, when diagnostic core biopsy or incisional biopsy is done (despite the lack of indication to do this), skin should be excised along the tract to ensure clear margins. The varieties of reconstructive options for providing cutaneous coverage are wide and include cervicofacial advancement and submental island myocutaneous, supraclavicular fasciocutaneous, and free fasciocutaneous flaps. Cervicofacial advancement is limited by its random blood supply and often is plagued by distal necrosis, especially in patients with any vascular disease or history of smoking. Furthermore, incision design must be determined before ablative surgery; and, if margins need to be revised, this can create a logistical issue for this flap.

The submental island myocutaneous flap is becoming the gold standard for cutaneous reconstruction of parotid defects in many institutions.26,48 It has the advantages of simple harvest (with new modifications)49 excellent skin color match, relatively quick harvest, minimal donor site morbidity (some limitation of neck extension), and shorter hospital stay versus free-flap reconstruction. The submental island flap can be used for defects up to 14 × 6 cm, but this depends on the submental laxity of the patient. Technical modifications include taking the mylohyoid muscle with the flap to avoid any difficult small-vessel dissection and preoperative understanding of venous drainage patterns (external jugular vs. internal jugular vein) to ensure the flap will not become congested. Furthermore, the anterior jugular vein can be coupled to an additional vein (typically external jugular) using loupe magnification to give additional venous drainage, when indicated. Although there are reports of surgeons experiencing repetitive failure of this flap,50 in experienced hands, the rate of success of this flap is >95%.26 If a two-team approach is being used, it is important the ablative team is aware that a submental flap is being raised and the neck dissection should be done after the flap is mobilized completely.

The supraclavicular flap is another reasonable regional option for parotid defects; however, depending on the length of the patient’s neck, the distal aspect of this flap may experience venous congestion or ischemia because the flap becomes less reliable the more distally is it raised. It is also essential that the skin overlying the triangle of the anterior border of the trapezius, the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid, and the clavicle is not raised during neck dissection. Furthermore, there should be no injury to the transverse cervical arterial system. Given these multiple constraints, this flap is used much less frequently for cutaneous parotid coverage.

Finally, free-flap reconstruction offers the most versatility and reach and is ideal for larger defects, which potentially involve the ramus of the mandible or the skull base. The anterolateral thigh flap, the radial forearm free flap, the rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap, and the latissimus flap are the most common free flaps for reconstruction of these defects. Although free flaps offer great versatility, they require a much greater burden of hospital resources and lead to more patient morbidity. Specifically, they require more operating room staff, longer operative time, and longer hospital stay and result in more patient donor site morbidity.26,51 For this reason, free flaps are reserved for defects that cannot readily be reconstructed with a submental island myocutaneous flap.

Briefly, facial reanimation is indicated any time the facial nerve is sacrificed or the buccal or zygomatic branches are sacrificed. Typically, the marginal mandibular nerve and temporal branch of the facial nerve do not benefit from reinnervation and can be conservatively managed by contralateral application of Botulinum toxin. Intraoperatively, the ideal reinnervation is to connect the masseteric nerve to the buccal branch of the facial nerve.52 This is a relatively easy and quick procedure, which produces excellent results given the supercharged nature of the nerve to the masseter. Patients typically can produce an appreciable smile after 3–6 months of this nerve transfer. Cable grafts from the facial nerve main trunk to peripheral branches produce tone, but rarely produce significant movement. Static or dynamic slings can also be used, but these must be discussed with the patient preoperatively and can always be done in a delayed fashion. Finally, it is important to consider eyelid procedures at the time of facial nerve sacrifice in select patients. Typically, a brow lift (direct or indirect), a gold weight, and a lateral tarsal strip are done to reduce morbidity in the eye after nerve sacrifice. Although this can certainly be done in a delayed fashion, it is important to consider this at the time of parotidectomy for patients who cannot easily undergo anesthesia or who have social situations which limit multiple appointments or procedures.

RADIOTHERAPY

Radiation therapy (RT) is a critical component in the treatment of salivary gland malignancies. Most typically, this occurs in the adjuvant setting after surgical resection with standard postoperative indications, including positive margins, nodal spread, perineural invasion, and specific histologic subtypes. However, in patients with unresectable tumors or patients who are not candidates for the operating room, definitive RT can be used. The propensity of certain types of salivary gland tumors to spread along cranial nerves brings an added layer of complexity to target volume contouring for these patients because elective cranial nerve RT is often considered. For these situations, in which target volumes approach critical normal structures, novel RT modalities, such as proton therapy, may be useful.

Adjuvant radiation

Whereas little prospective evidence exists to guide treatment decisions in the adjuvant setting, indications for adjuvant RT are relatively standard, although they depend significantly on the histology of the resected tumor. Benign tumors, such as Pas, do not need adjuvant RT unless positive margins are seen or in situations of multiple lines of recurrence or multifocal recurrence.53 For patients with malignant tumors, indications for adjuvant RT are based primarily on retrospective historical data. In a review from the Dutch Head and Neck Oncology Cooperative Group, postoperative RT improved local control in patients with pathologic T3–T4 disease, close or positive margins, bone invasion, and perineural invasion. Postoperative RT improved regional control for patients who had any nodal disease in their neck. The authors recommend a dose ≥60 grays (Gy) for adjuvant RT with a dose-response relationship seen.54,55 This dose remains the standard to the present time. Other analyses of larger databases, such as the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, show an overall survival benefit to the addition of adjuvant RT in patients with high-grade or locally advanced (T3/T4 or lymph node-positive) disease.56 Similar results are seen in analyses of the National Cancer Database.57

One specific histology that often portends an increased risk for local recurrence is ADCC. Single-institution, retrospective analysis has suggested that patients with ADCC have improved locoregional control with the addition of adjuvant RT. This is predominantly because of its propensity for neurotropic spread along the cranial nerves.58 For patients with adenoid cystic tumors, magnetic resonance imaging and careful clinical examination of cranial nerve function are recommended to best define any potential perineural invasion.59 In many patients, elective cranial nerve irradiation is performed in this setting to minimize the risk of recurrence along the cranial nerves, which can be devastating. This can be clinically quite challenging because the cranial nerves themselves are often challenging to see on a computed tomography simulation done for radiation treatment planning. Contouring guidelines to help guide radiation treatment volumes in this setting can be extremely helpful.60

Definitive radiotherapy

Although surgical resection remains the optimal treatment for patients with salivary gland malignancies, there are some patients who have very locally advanced tumors that are not amenable to complete surgical resection because of invasion into critical nearby structures. In addition, some patients may have other medical comorbidities that preclude them from undergoing surgical resection safely. In these cases, definitive RT should be offered for patients with nonmetastatic disease. No prospective evidence exists to guide treatment in these situations, and the available retrospective data are often heterogeneous with respect to histology and other risk factors, which makes interpretation challenging. Single-institution, retrospective reports suggest that 5-year locoregional control after definitive RT is lower than in patients who undergo upfront surgical resection. However, a bevy of clinical and pathologic factors (T classification, N classification, histologic grade, perineural invasion, among others) influence outcomes.61,62 A prior Dutch analysis suggested a higher total dose ≥66 Gy with standard fractionation for patients with unresectable tumors. However, other guidelines suggest 70 Gy.54,63

Alternative radiation modalities have long been considered for salivary gland malignancies to improve local control, especially in the definitive setting. In the 1980s, a Radiation Therapy Oncology Group-Medical Research Council cooperative study randomized 32 patients with inoperable, recurrent, or unresectable malignant salivary gland tumors to receive either conventional photon RT or neutron RT. The 2-year locoregional control rate was significantly higher with neutron therapy (67% vs. 17%; p < .005)64 This benefit in locoregional control persisted with 10-year follow-up; however, no significant difference in overall survival was seen. In addition, there was an increased incidence of severe long-term toxicity in the neutron arm.65 This increased toxicity, along with improved outcomes with photon RT seen in more contemporary series and the scarcity of neutron facilities in the United States, has led to neutron RT predominantly falling out of favor in this setting, at least in the United States.62 More recently, proton therapy has been used in the treatment of SGCs, although with a predominate focus of reducing toxicity of treatment. Single-institution reports describe minimal toxicity associated with proton therapy in both the definitive and adjuvant settings and very promising locoregional control.66,67 Proton therapy may be specifically beneficial in patients who have either extensively locally invasive tumors or perineural invasion involving the skull base, which may be in close proximity to critical normal structures, such as the brainstem, optic nerves, or temporal lobe. However, no prospective evidence exists to support the use of proton therapy in this setting. In addition, hypofractionated (high dose-per-fraction) techniques, such as stereotactic body RT, may be considered in the definitive setting either alone or as a boost after a lower dose of conventionally fractionated RT. Although small retrospective series suggest oncologic outcomes at least comparable to those of conventionally fractionated RT, there are no prospective data to support the use of stereotactic body RT in salivary gland malignancies.68,69

SYSTEMIC THERAPY

Chemotherapy in the curative setting

Unlike in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, there are no large prospective data to inform clinicians on the use of adding chemotherapy to radiation for high-risk SGCs after surgical resection. Salivary gland carcinomas are a heterogeneous grouping of histologies, and large clinical studies in this setting are difficult to perform. Retrospective institutional and national database studies have reported mixed results with the addition of postoperative chemotherapy to radiation.70,71 Because of this, the use of chemotherapy is often debated and, in practice, a decision is often made based on clinical judgement and discussion with the patient. Pathologic features, such as close/positive margins, high-grade histologies like SDCs, and multiple involved lymph nodes, are often used as poor prognostic indicators and scenarios that prompt discussion about the role of systemic treatment.72

Cisplatin is typically the chemotherapy chosen to be given with radiation, extrapolated from its use in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and its general efficacy in salivary gland carcinomas.63 Fortunately, a clinical trial has completed enrollment and should provide guidance in this area. Radiation Therapy Oncology Group trial RTOG 1008 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NT01220583) randomized patients with salivary gland tumors who had traditional risk factors (pathologic T3 [pT3]/pT4 disease, pathologic lymph node-positive disease, close [≤1 mm] or positive margins, or aggressive histologic subtype) to receive either adjuvant RT alone or adjuvant RT with concurrent weekly cisplatin, with a primary end point of overall survival.73 The results of this study are eagerly awaited.

Chemotherapy in the recurrent/metastatic setting

For salivary gland tumors that metastasize or are no longer amenable to curative therapy, the first decision is whether to pursue systemic therapy or expectant management. This is often a decision based on patient preferences, histology, and aggressiveness of the tumor. Expectant management may be appropriate for low-grade tumors with low disease burden. In expectant management, metastasectomy for slow-growing tumors is a reasonable option and has demonstrated the ability to lead to prolonged disease intervals for selected patients.74

For patients who opt for or are counseled to initiate systemic therapy, chemotherapy remains the mainstay of treatment. However, there are no large, randomized trials that can inform treatment decisions. Based on limited data, a mainstay of treatment is combination therapy, which typically includes cisplatin or carboplatin. In general, response rates range between 20% and 45%, although such therapy appears to have little activity in specific subsets.75 For example, in a retrospective analysis, the overall response rate to carboplatin and paclitaxel was 29%, although the response rate specific to ADCC was <10%.76,77

In addition to cytotoxic chemotherapy, multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors have been studied in select patients. Lenvantinib, axitinib, and sorafenib all have been used and have demonstrated only modest benefit, with response rates ranging from 5% to 25%, depending on drug and SGC cytopathologic subtype, but with significant toxicity.78–80 Overall, whereas both chemotherapy and tyrosine kinase inhibitors form the backbone for our treatment of SGCs, clearly other treatment modalities and clinical research are needed.

IMMUNOTHERAPY FOR SALIVARY GLAND CANCERS

Given the limited, standard, systemic therapy options for patients with SGCs, we recommend participation in a clinical trial.81 Therefore, there is a need for collaborative efforts in the investigation of novel therapeutic options, including immunotherapy, in the management of metastatic SGCs. The programmed death 1 (PD-1) receptor inhibits T-cell function when binding to its ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L282 PD-L1 expression has been observed in 22.8% of SGCs and was associated with worse disease-free and overall survival in a retrospective series.83

One of the main studies testing the clinical activity of PD-1 inhibitors in SGC is Keynote-028 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02054806), which is a phase lb trial enrolling patients with different tumor types.84 The study enrolled patients who had PD-L1-positive SGC for which standard therapy was ineffective or was deemed inappropriate. In total, 26 patients with SGC were enrolled based on PD-L1 expression ≥1% and received pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks for up to 2 years. The objective overall response rate was 12% (three patients achieved a partial response), with a median duration of response of 4 months (range, 4–21 months).85 Despite the limited responses observed, a disease control rate of 58% as well as durable responses were observed in this heavily pretreated population. It is worth indicating that the reported responses are equivalent to those observed with tyrosine kinase inhibitor use in subtypes of SGC, such as ADCC.86 These data suggest that there may be value in using PD-1 inhibitors in biomarker-selected patients with advanced SGC.

Keynote-158 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02628067) is a subsequent study enrolling patients with metastatic SGC. PD-L1-positive disease was noted in 25.7% of patients. Despite a response rate of only 4.6%, enrichment of responses was noted in PD-L1-positive patients, and the duration of response exceeded 2 years in few patients, reinforcing the value of PD-1 inhibitors in a selected group of SGCs.87 Despite the small number of patients with SGC on Keynote-158, a subsequent analysis indicated a high tumor mutation burden (TMB-high status) correlated with improved responses to anti–PD-1 therapy88

Combination immunotherapeutic approaches have not been commonly investigated in SGCs. A phase 2 trial combining the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab and the CTLA4 inhibitor ipilimumab is currently enrolling patients with recurrent, metastatic SGC (excluding ADCC) and assessing the response rate as its primary end point. Among the 32 enrolled patients, five confirmed partial responses were noted, with regressions ranging between 66% and 100% in target lesions.89 A phase 2 basket trial of the same combination revealed a response rate of 4% in patients with ADCC.90

Although PD-L1 appears to be a predictive biomarker for clinical benefit to immune checkpoint inhibitors in other malignancies, better markers are needed in SGC, which can be achieved only in larger prospective studies. Although the results with immunotherapy are currently rather limited, future research focusing on introducing novel combinatorial approaches that could enhance the benefit to immunotherapy in these diseases will need to be pursued. Nonetheless, the American Society of Clinical Oncology issued its guidelines for immunotherapy and biomarker testing in head and neck cancers indicating that pembrolizumab may be offered to patients who have PD-L1-positive, recurrent or metastatic SGCs and immunotherapy, albeit with a moderate quality of evidence and a strength of recommendation noted to be weak (recommendation 6.2).91

Targeting HER2

The HER-2/neu proto-oncogene is positioned on chromosome 17q and regulates cell growth and development, whereby the gene encodes a tyrosine kinase receptor member of the epidermal growth factor receptor family. These four receptors are capable of heterodimerization, leading to cell-signal transduction that can facilitate tumor growth.92 Amplification of the HER2 gene or protein overexpression is suggested in several solid tumor malignancies.93

In the early 2000s, it became evident that more clinically aggressive SGCs often overexpressed or demonstrated amplification in the proto-oncogene HER-2/neu.94 Because SDC shares histologic resemblance to invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast, HER2 expression was also potentially important in salivary tumors (whether primary or metastatic). Larger efforts to score multiple salivary cancer histologies for HER2 overexpression demonstrated that the overall frequency was low, around 17%,95,96 but that high-grade histologic features correlated with HER2 expression among subtypes such as SDC, MEC, and CXPA, in which HER2 positivity ranged from 21% to 83%. A systematic review of 80 studies summarized HER2 overexpression among SDCs at 45% and, among MECs, at 84%.97 Furthermore, it is unclear whether HER2 expression is prognostic; in one study specifically in SDC, HER2 expression was associated with a propensity for distant metastatic spread and decreased 5-year survival.98

There are various ways to measure HER2 oncogene activity, and most scoring in SGCs has recapitulated testing practices adopted from breast cancer.99 Although these cutoffs have been used in scoring SGCs, there is no clear standardization or scoring rubric available that is specific to these tumors, and HER2 positivity can vary considerably across different studies. Notably, several series have demonstrated lower 3+ IHC expression and HER2 gene amplification concordance compared with breast cancer.100,101 Although speculative, it is plausible that HER2 protein overexpression is regulated independently from gene amplification in salivary cancers or that the rates of gene transcription and protein degradation are important.101 Other work has suggested that HER2 signaling in SDC may potentiate the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway.102

Despite the variation in scoring and expression patterns across salivary histologies, it is important to routinely assess HER2 IHC (with reflex ISH testing, when appropriate) in clinical practice among all high-grade salivary cancers (specifically SDC and MEC), particularly in the setting of recurrent or metastatic disease given the therapeutic implications.

HER2-directed therapies in the recurrent, metastatic setting

The first prospective trial to evaluate the HER2-directed antibody trastuzumab in patients who had SGC with HER2 IHC overexpression (2+ to 3+) was published in 2003. Fourteen patients with locoregionally advanced or metastatic tumors received trastuzumab 2 mg/kg weekly after a loading dose until progression with minimal evidence of activity (objective response rate, 8%).103 The dual erbB2 (gene encoding HER2) and the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor lapatinib (1500 mg daily) also were evaluated in patients who had advanced SGC with 2+ HER2 tumor expression, and no responses were observed among 17 patients, although eight patients (47%) had stable disease (which lasted ≥6 months in four patients).104 Extrapolating from advanced breast cancer, adding taxane therapy to HER2-targeted treatment was later explored. A single-arm, Japanese, phase 2 trial of trastuzumab (6 mg/kg every 3 weeks after a loading dose) in combination with docetaxel (70 mg/m2 every 3 weeks) among 57 participants with HER2-overexpressing (3+IHC expression or gene amplified), advanced SGC reported a response rate of 70% and a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 8.9 months.105 The combination was well tolerated, with expected cytopenias observed. A small series reported the use of trastuzumab with paclitaxel and carboplatin (TCH) (every 3 weeks for six cycles) among patients with HER2 2+ to 3+, advanced salivary cancer with favorable activity, including one complete response lasting for >4 years (the median duration of response was 18 months).106 Fifteen patients in the phase 2a multibasket MyPathway study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02091141) had HER2-amplified and/or overexpressing (with or without mutations) salivary cancers and were treated with dual anti-HER treatment using trastuzumab and pertuzumab (420 mg intravenously every 3 weeks after a loading dose). The response rate was 60%, with a median duration of 9.2 months and a median PFS of 8.6 months.107 Based on these combined data, trastuzumab is often combined with platinum and/or taxane therapy (the latter is sometimes combined with pertuzumab) in the first-line setting for advanced HER2-overexpressing salivary cancers.

When HER2-targeting antibody-drug conjugates emerged, interest turned to exploring agents like trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1), even among patients with prior trastuzumab exposure. The National Cancer Institute-Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice (NCI-MATCH) precision medicine study treated 38 patients who had HER2-amplified tumors (greater than 7 copy numbers) with various solid tumors using T-DM1 (3.6 mg/kg every 3 weeks), and two partial responses were observed, both in patients who had SGC.108 Li and colleagues treated 10 patients who had HER2-amplified (identified by next-generation sequencing), advanced SGCs as part of a larger basket study and demonstrated a response rate of 90%, with five complete responses among patients who had been treated with prior trastuzumab and pertuzumab; the median PFS was not reached (95% confidence interval, from 4 to ≥22 months).109 Notably, patients had received a median of two prior lines (range, zero to three prior lines) of systemic therapy before enrollment. The latter data suggest that sequential HER2 targeting can be beneficial for patients with HER2-overexpressing, advanced SGCs in the second line and beyond. Illustrating this point, a small series from the Netherlands treated 13 patients who had HER2-positive SDC with combined docetaxel, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab in the first line, with 58% responding (median PFS, 6.9 months); then, seven patients from the same cohort went on to receive second-line T-DM1, with a 57% response rate and a median PFS of 4.4 months.110

Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd; DS-8201a) is a novel antibody-drug conjugate with a humanized anti-HER2 antibody that has a cleavable peptide-based linker and a potent topoisomerase I inhibitor payload. The drug-to-antibody ratio is two-fold higher than that of T-DM1, enabling efficient drug delivery, and the payload is membrane-permeable, allowing a neighboring tumor cell cytotoxic effect.111 These properties have made T-DXd appealing to investigate among solid tumors with low or heterogeneous HER2 expression. Tsurutani and colleagues evaluated T-DXd (5.4–6.4 mg/kg, every-3-week dosing at optimization) among 60 patients with previously treated, HER2-expressing solid tumors (≥1+ HER2 IHC expression) in a phase 1 dose-finding trial.112 Therapy was well tolerated with some nausea, decreased appetite, and vomiting. Eight patients with SGC were included with some tumor regression observed.

Given the benefits of sequential HER2 targeting in salivary cancer, as newer HER2-directed therapies surface and the lower limits of HER2 expression are redefined, incorporating these therapies into practice is important, particularly given the limited benefit of cytotoxic chemotherapy and the lack of approved therapies in this disease. The latter rely on willing and determined clinicians securing off-label approval for these drugs or ensuring access to clinical trials for these patients.

HER2-directed therapies in the adjuvant setting

Moving beyond the advanced disease setting, the use of adjuvant HER2-based therapy to mitigate the risk of disease relapse, particularly distant metastatic spread, is of great interest. A case series of nine patients who received adjuvant chemoradiation using weekly carboplatin and paclitaxel with RT followed by trastuzumab maintenance continued up to 1 year.113 Median disease-free survival and overall survival were longer among TCH-treated patients compared with comparable patients who received chemoradiation alone. No difference in outcomes according to HER2 expression intensity or amplification status was noted (recognizing the small sample size). However, six patients who received adjuvant TCH with HER2-expressing (2+ to 3+) salivary cancers recurred at a median follow-up of 5.2 years.

Some experts routinely use this or a similar trastuzumab-based regimen in the adjuvant setting for HER2-overexpressing salivary cancer tumors if they secure off-label approval. The first prospective, multicenter trial of adjuvant HER2 therapy using 1 year of T-DM1 is enrolling in the United States for patients with locoregionally advanced, HER2-expressing (2+ to 3+) SGCs who have undergone surgery followed by adjuvant weekly cisplatin with radiotherapy (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT04620187). Cisplatin was chosen in that study because platinum-taxane radiosensitization may increase mucositis risk, and cisplatin is the preferred radiosensitizer in mucosal head and neck squamous cell cancers. Future studies may investigate adjuvant T-DXd therapy for HER2 low-expressing salivary tumors in the adjuvant or even neoadjuvant setting.

Targeting androgen receptor

AR is a nuclear steroid hormone receptor that is expressed in several human tissues, with testosterone and 5α-dihydrotestosterone as its main ligands. AR regulates the transcription of several effector genes through direct DNA interactions, with aberrations in signaling leading to oncogenic potential in prostate cancer and other cancers.114 Similar to HER2, AR expression measured by IHC varies among different types of SGCs and most frequently has been identified among SDCs (range, 64%–98%).115 The frequency of AR expression in other salivary cancer subtypes is 0%–30%. The variability in reported expression among SDCs may reflect improvements in histologic classification and technical issues around staining.

Studies have demonstrated that AR IHC-negative SDC can demonstrate detectable messenger RNA signaling in AR, which may suggest a mechanism of acquired activation in some tumors.116 In prostate cancer, resistance to androgen-targeted therapies can occur when the full-length AR gene is spliced to yield variants that lose the ligand-binding domain.117 AR-V7 is a variant that includes only exons 1–3 and has been identified in SDCs.118 Other genetic alterations in AR signaling that have been identified in SDCs include X chromosome (housing the AR gene) polysomy; FOXA1 mutations, which regulate AR transcription; and FASN mutations, which disrupt the enzymatic regulation of fatty acid synthesis.116 These collective molecular observations suggest that targeting AR in overexpressing salivary cancers is important to consider and that mechanisms of acquired resistance could be relevant with exposure to androgen-blocking therapies.

Androgen-deprivation therapy in the recurrent, metastatic setting

Borrowing from the therapeutic armamentarium of prostate cancer, androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) has been explored to treat patients who have salivary cancer with tumor AR expression. In a retrospective series of patients with AR-positive salivary cancer who received the oral antiandrogen bicalutamide with a gonadotropin hormone-releasing hormone agonist, 65% of patients demonstrated a response.119 In 2018, the first prospective phase 2 trial reported a 42% response rate when using the gonadotropin hormone-releasing hormone agonist leuprolide with bicalutamide among 36 patients who had advanced, AR-positive salivary gland carcinoma, with a median PFS of 8.8 months.120 Although this established combined androgen blockade with a gonadotropin hormone-releasing hormone agonist and an oral antiandrogen as a first-line option in these tumors, it is unclear whether using cytotoxic chemotherapy first is preferable. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Head and Neck Cancer Group/UK Clinical Research Network 1206 trial is a randomized phase 2 study that aims to address this question (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01969578).

Downregulation of AR pathway signaling or upregulation of SRD5A1, the enzyme that promotes conversion of testosterone to 5α-dihydrotestosterone, are known to negatively affect combined androgen-blockade response.121 Upstream of testosterone, steroid synthesis can also be enhanced by upregulation of the cytochrome P450 family 17 subfamily A polypeptide 1, but this enzyme has not been observed in SDC despite being identified in prostate tumors.122 A phase 2, second-line study evaluating the cytochrome P450 family 17 inhibitor abiraterone with ADT enrolled 24 patients with AR-positive disease who had previously been treated with ADT alone. The response rate was 21%, with a median duration of response of 5.8 months and a median PFS of 3.6 months.123 These data support the use of sequential ADT for so-called castrate-resistant, AR-positive salivary cancers. Another phase 2 study using the next-generation oral antiandrogen enzalutamide (160 mg daily) among 46 patients with advanced, AR-positive salivary cancer (28% had received prior ADT) yielded a 15% response rate (4% confirmed), with a median PFS of 5.6 months.124 Notably, the latter study did not continue ADT with enzalutamide. Furthermore, studies have not aligned in their definition of AR overexpression because some protocols require ≥1% nuclear AR staining, whereas others have used a combination of an intensity score (0–3) and high nuclear expression (≥70%) to enrich patient selection. How AR splice variants or acquired resistance evolve with sequential AR-directed therapy in salivary cancer is not well understood.

We believe that the sequential use of AR-directed therapy in AR-overexpressing salivary cancers, particularly SDC, is important in the recurrent, metastatic setting, and clinical trial participation should always be encouraged. When both AR and HER2 overexpression are observed in a particular tumor, preference is often given to targeting HER2 certainly if 3+ IHC status or gene amplification is identified. Combining AR and HER2 therapies in practice is not typically favored.

ADT in the adjuvant setting

Whether adjuvant ADT should be incorporated as part of postoperative therapy for patients with locoregionally advanced, AR-positive salivary cancers is not yet known. A group of European investigators published a retrospective study of 22 patients with stage IVA, AR-positive SDC treated with adjuvant ADT for a median duration of 1 year compared with a control group of 111 patients who were not treated after surgery. At a median follow-up of nearly 2 years, the 3-year disease-free survival rate was 48% in the ADT-treated group versus 28% among similar controls.125 Future trials should aim to prospectively address this question, but execution has been difficult given the relative rarity of the condition and the need to agree on the preferred form of ADT and duration of therapy.

Targeted therapy