Abstract

Background

A total of 18%–30% of Canadians live in a rural area and are served by 8% of the country’s general surgeons. The demographic characteristics of Canada’s population and its geography greatly affect the health outcomes and needs of the population living in rural areas, and rural general surgeons hold a unique role in meeting the surgical needs of these communities. Rural general surgery is a distinct area of practice that is not well understood. We aimed to define the Canadian rural general surgeon to inform rural health human resource planning.

Methods

A scoping review of the literature was undertaken of Ovid, MEDLINE, and Embase using the terms “rural,” “general surgery,” and “workforce.” We limited our review to articles from North America and Australia.

Results

The search yielded 425 titles, and 110 articles underwent full-text review. A definition of rural general surgery was not identified in the Canadian literature. Rurality was defined by population cut-offs or combining community size and proximity to larger centres. The literature highlighted the unique challenges and broad scope of rural general surgical practice.

Conclusion

Rural general surgeons in Canada can be defined as specialists who work in a small community with limited metropolitan influence. They apply core general surgery skills and skills from other specialties to serve the unique needs of their community. Surgical training programs and health systems planning must recognize and support the unique skill set required of rural general surgeons and the critical role they play in the health and sustainability of rural communities.

Abstract

Contexte

En tout, 18 %–30 % de la population canadienne vit en milieu rural et est desservie par 8 % des effectifs en chirurgie générale au pays. Les caractéristiques démographiques de sa population et la géographie du Canada influent grandement sur l’état de santé et les besoins de la population rurale, et la chirurgie générale en milieu rural joue un rôle central en répondant aux besoins chirurgicaux de ces communautés. La chirurgie générale en milieu rural est un domaine de pratique à part, et elle n’est pas bien comprise. Nous avons voulu définir la chirurgie générale en milieu rural au Canada pour en faciliter la planification des ressources humaines.

Méthodes

Nous avons procédé à une synthèse exploratoire de la littérature auprès des bases de données Ovid, MEDLINE, et Embase à partir des termes anglais « rural », « general surgery », et « workforce ». Nous avons limité notre interrogation aux articles provenant de l’Amérique du Nord et de l’Australie.

Résultats

L’interrogation a généré 425 titres, et 110 articles ont fait l’objet d’une revue du texte intégral. Nous n’avons trouvé aucune définition de la chirurgie générale en milieu rural dans la littérature canadienne. La ruralité était définie par des seuils de population ou le rapport entre la taille d’une communauté et sa proximité d’un grand centre. La littérature a fait ressortir les défis particuliers et la portée du champ de pratique de la chirurgie générale en milieu rural.

Conclusion

La chirurgie générale en milieu rurale au Canada peut se définir comme un champ de spécialité qui dessert une petite communauté et qui subit peu l’influence de la métropole. Elle applique les techniques fondamentales de la chirurgie générale et emprunte certains actes médicaux à d’autres spécialités pour répondre aux besoins particuliers des communautés. Les programmes de formation en chirurgie et la planification des systèmes de santé devraient reconnaître et soutenir l’ensemble unique des habiletés requises pour exercer en chirurgie générale en milieu rurale et son rôle dans la santé et la préservation des communautés rurales.

According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information, 8% of general surgeons in Canada work in a rural setting, whereas 18%–30% of the population lives in rural areas, which are dispersed over 95% of the total land mass.1–3 Rural Canadians are a socially diverse and culturally distinct population of Canada, who often face inequities in health care access. Indigenous people are more highly represented within rural Canada, as are people with increased comorbidities, reduced overall income, and a poor level of health compared with urban Canada.4,5 Physicians and surgeons who serve this population face challenges when it comes to meeting the health care needs of rural Canadians. Often having to do more with less, they play a crucial role in their communities.

Rural surgeons positively affect their communities by providing expert-level care close to home. They improve trauma outcomes and provide access to maternity care in their community, which would otherwise be unavailable without surgical back-up.6–11 To better understand the unique role rural general surgeons play in their communities, we aimed to assess the existing surgical literature for definitions and descriptions of rural surgeons and rural surgery practice, particularly in the areas of scope of practice, training, workforce, clinical outcomes, and recruitment and retention. We sought to develop a unifying definition of a Canadian rural general surgeon to guide future health human resource decisions and define training needs to support the sustainability of rural surgical care in Canada.

Methods

We undertook a scoping review of the literature, searching Ovid, MEDLINE, and Embase databases for primary research studies using the following terms: “general surgery,” “rural,” and “workforce.” These terms were further expanded with appropriate Medical Subject Headings. Two authors (M.D. and E.F.) used Covidence to complete the title and abstract review, and a third author (L.G.) reviewed disagreements.12 Inclusion criteria were general surgeons, Canada, Unites States, and Australia. Australia is frequently compared with Canada, as its population is similarly dispersed and comparable in characteristics, and care provision is equally challenging. The year of publication was not restricted. Studies from other geographic areas and conference proceedings were excluded, as were commentary and grey literature articles.

Full article reviews were undertaken, and searching for a definition of rural surgery was the primary objective. We further assessed articles for the definition of rurality used by authors, as well as data regarding rural scope of practice, workforce, training, clinical outcomes, and barriers to rural surgery. Bibliographies were reviewed to identify any further relevant literature. We used these data to develop a unifying definition of a rural surgeon in Canada.

Results

Literature review

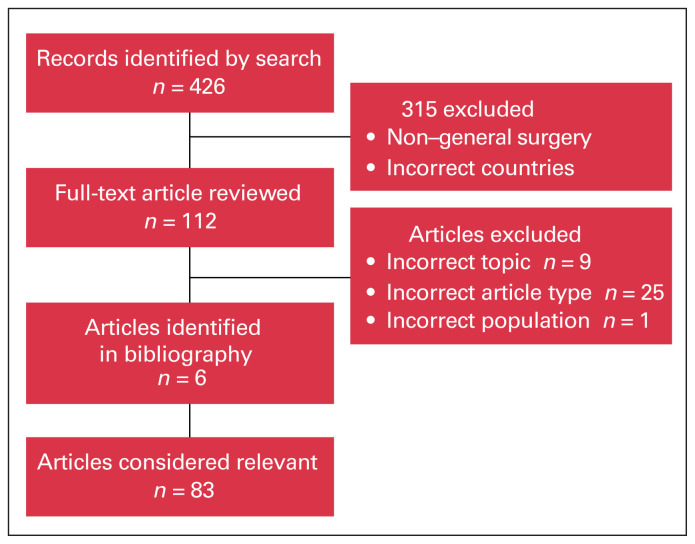

The initial literature search identified 426 titles, and 315 were excluded. The remaining 112 articles underwent a full-text review and bibliography review, and 83 were considered relevant (Figure 1). Publications included 9 Canadian, 64 American, and 11 Australian studies (Table 1). Relevant topics identified in rural surgery literature included scope of practice, surgical workforce, surgical training, clinical outcomes, and recruitment and retention (Table 2). Articles regarding rural surgery topics outside of these 5 topics are included in Table 3.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart showing the inclusion and exclusion of articles.

Table 1.

Country of publication

| Country of publication | No. of articles |

|---|---|

| Canada | 9 |

| United States | 64 |

| Australia | 11 |

Table 2.

Literature topics

| Definition | No. of articles |

|---|---|

| Scope of practice | 32 |

| Surgical workforce | 21 |

| Surgical training | 22 |

| Clinical outcomes | 13 |

| Recruitment and retention | 6 |

| Other | 5 |

Table 3.

Summary of findings for other topics in rural surgery

| Publication | Country | Context | Primary findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cofer and Burns, 200813 | United States | Estimation of the economic value of a rural surgeon | A general surgeon was estimated to be worth $1.05 million to $2.4 million to a rural hospital |

| Doty et al., 200714 | United States | Case report of initiation of a surgical program at a critical access hospital | Description of implementation of a surgical program at a critical hospital |

| Doty et al., 200815 | United States | Perception of rural hospital administrators on the importance of general surgery | 111 surveys completed 82% of administrators viewed general surgery services as important to the financial viability of the hospital |

| Musgrove et al., 202016 | United States | Survey of rural hospitals emergency resources in nonteaching hospitals in West Virginia | In assessment of 45 hospitals, all had access to cross-sectional imaging, ventilator, operating rooms (ORs), and laboratory Not all critical access hospitals had access to OR teams 24/7 and full blood bank capabilities; increasing these resources would decrease the number of patients transferred |

| Wong and Petchell, 200417 | Australia | Assessment of rural trauma management in New South Wales, Australia | 14 hospitals identified; 43% had a permanent surgeon |

Definition of a rural surgeon

One group put forth a definition; Nealeigh and colleagues18 defined an “isolated surgeon,” which encompassed both rural US and deployed military surgeons. Their definition was derived from strictly American literature based in civilian rural America and the American military. They set out 8 criteria, 5 of which were required for a surgeon to be considered an “isolated surgeon.” The criteria were based on size of community; availability of resources, such as imaging and blood bank capabilities; distance to more complex care; and availability of local and nearby medical and surgical specialties.18

Defining rurality

A total of 50 studies used a specific definition of rurality; authors defined rurality in many ways. Most frequently used were population cut-off values (< 2500 to < 150 000 people), metropolitan influence, and health authority (Table 4 and Table 5).24,25,27,29,30,34,35,40,41,44,45,47,48,53,57,58,60,61,63,66 An example of metropolitan influence is the American Rural–Urban Commuting Area code used frequently in American studies, whereas Canadian groups more often used census data stratified by metropolitan influence. 18,23,32,36–38,43,46,50,52,55,59,64,65 The third most common definition is based on government or health authority definitions, for example, the Canadian census definition. 17,19,26,28,31,39,49,62 Other authors use a unique definition that is specific to the context of the hospital, region or question that is being answered. For example, a study assessing the use of surgical resources in Manitoba defines rural as any county outside of 2 provincial metropolitan areas.20–22,51,54

Table 4.

Definitions of rurality

| Definition | No. of articles |

|---|---|

| Population cut-off | 21 |

| Metropolitan influence | 15 |

| Government or health authority | 9 |

| Other | 5 |

Table 5.

Summary of rurality definitions

| Publication | Country | Definition of rurality |

|---|---|---|

| Hilsden et al., 200719 | Canada | Canadian census |

| Micieli et al., 201520 | Canada | Population cut-off; Local Health Integration Network population < 600 000 |

| Roos, 198321 | Canada | All areas outside of the only 2 metropolitan areas in the province of Manitoba |

| Rourke, 199822 | Canada | Community population < 2000; < 100 acute care beds |

| Schroeder et al., 202023 | Canada | Statistics Canada: community outside of a commuting area of an urban centre with > 10 000 |

| Bruening and Maddern, 199824 | Australia | Population cut-off < 50 000 |

| O’Sullivan et al., 201725 | Australia | Population cut-off < 50 000 |

| Shanmugakumar et al., 201726 | Australia | Western Australian Health Department rural and remote designated hospitals |

| Wong and Petchell, 200417 | Australia | New South Wales Department of Health hospital designation |

| Ahmed et al., 201227 | United States | Population cut-off < 150 000 |

| Baldwin et al., 199928 | United States | Washington State Office Rural Health |

| Breon et al., 200329 | United States | Population cut-off < 25 000 |

| Burkholder and Cofer, 200730 | United States | Population cut-off < 25 000 |

| Chaudhary et al., 201731 | United States | National Inpatient Sample coding; rural included micropolitan and noncentre hospitals |

| Cofer et al., 201132 | United States | Rural–urban commuting codes |

| Cook et al., 201933 | United States | Population cut-off < 50 000 |

| Deveney and Hunter, 200934 | United States | State of Oregon definition: < 30 000 |

| Deveney et al., 201335 | United States | Population cut-off < 50 000 |

| Doty et al., 200636 | United States | Rural–urban commuting codes |

| Doty et al., 200937 | United States | Rural–urban commuting codes |

| Doty et al., 200938 | United States | Rural–urban commuting codes |

| Ellison et al., 202139 | United States | United States Census Bureau: area that is outside of urban areas |

| Etzioni et al., 201040 | United States | Population cut-off < 2500 |

| Gates et al., 200341 | United States | Population cut-off < 10 000 |

| Gadzinski et al., 201342 | United States | Critical access hospitals |

| Germack et al., 201943 | United States | Department of Agriculture Rural–Urban Continuum Codes |

| Glenn et al., 201744 | United States | Population cut-off < 50 000 |

| Gruber et al., 201545 | United States | Office of Management and Budget Definition (county population < 10 000) |

| Harris et al., 201046 | United States | Rural–urban commuting codes |

| Heneghan et al., 200547 | United States | Office of Management and Budget Definition (county population < 10 000) |

| Jarman et al., 200948 | United States | Population cut-off < 50 000 |

| Komaravolu et al., 201949 | United States | United States Census Bureau: area that is outside of urban areas |

| Kwakwa and Jonasson, 199750 | United States | Rural–urban commuting code |

| Landercasper et al., 199751 | United States | Hospital network designation of rural |

| Lynge, 200852 | United States | Rural–urban commuting codes |

| Mercier et al., 201953 | United States | Population cut-off < 50 000 |

| Moesinger and Hill, 200954 | United States | Non-urban counties of Utah |

| Moore et al., 201655 | United States | Rural–urban commuting codes |

| Natafgi et al., 201756 | United States | Rural–urban commuting codes |

| Nealeigh et al., 202118 | United States | Population < 10 000; nearest tertiary referral centre > 100 miles or 2-hour commute |

| Ritchie et al., 199957 | United States | Population cut-off < 50 000 |

| Shively and Shively, 200558 | United States | Office of Management and Budget Definition (county population < 10 000) |

| Sticca et al., 201259 | United States | Rural–urban commuting codes |

| Stiles et al., 201960 | United States | Office of Management and Budget Definition (county population < 10 000) |

| Stinson et al., 202161 | United States | Population cut off < 50 000 |

| Stringer et al., 202062 | United States | Population density determined by the Kansas Department of Health and Environment |

| Thompson et al., 200563 | United States | Population cut-off < 50 000 |

| Valentine et al., 201164 | United States | Rural–urban commuting codes |

| VanBibber et al., 200665 | United States | Rural–urban commuting codes |

| Zuckerman et al., 200766 | United States | Office of Management and Budget Definition (county population < 10 000) |

Rural surgery scope of practice

Thirty-two articles assessed the scope of practice of rural surgeons (Table 6). Up to one-third of their scope of practice falls outside of traditional general surgery core competencies, excluding endoscopy.29,41,51,70 Many authors investigated the details of nontraditional procedures that a rural surgeon performs; most frequently identified were urology, orthopedic surgery, and obstetrics and gynecology (Appendix 1, available at www.canjsurg.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cjs.002123/tab-related-content).23,29,41,46,47,57,60,65,68,70,72,73,77

Table 6.

Summary of scope of practice findings

| Publication | Country | Context | Primary findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ang et al., 202067 | Australia | Remote Australian base hospital; single institutional review of vascular emergencies | Rural surgeons located at base hospitals were required to complete emergency vascular surgery |

| Baldwin et al., 199928 | United States | Comparison of rural physician practice with urban practice | Rural general surgeons were more likely to be referred patients requiring gastrointestinal workup |

| Bappayya et al., 201968 | Australia | Review of procedures completed at a rural hospital by general surgeons | Endoscopy 35.9%; 5.4% of all procedures non–general surgery, including urology, vascular, and orthopedics |

| Bintz et al., 199669 | United States | Rural American hospital review of traumas; Injury Severity Score 8–43 | 84 traumas reviewed; surgeons partook in trauma team resuscitations, procedures, or stabilization for transport, or provided local definitive treatment of patients |

| Breon et al., 200329 | United States | Scope of practice of surgeons in rural Iowa | Endoscopy comprises a significant proportion of a rural surgeon’s practice Rural surgeons were more likely to complete cesarean deliveries, hip fracture, tonsillectomies, and urologic procedures than urban surgeons |

| Campbell et al., 201170 | Australia | Assess the scope of practice of 2 practising surgeons in a rural hospital | 8336 procedures performed Traditional general surgery 44.3%, endoscopy 27.4%, other specialties: orthopedics, head and neck, neurosurgery, and obstetrics |

| Campbell et al., 201371 | Australia | Assessment of the caseload of outreach surgeons | 18 029 procedures; 32% endoscopies; emergency procedures included vascular and neurosurgery |

| Cogbill and Bintz, 201772 | United States | Assessment of scope of practice for a network of rural general surgeons | Colonoscopies account for 52% of rural surgeons’ practice, cesarean delivery 3.9%, and gynecology 2.2% |

| Etzioni et al., 201040 | United States | Assess the proportion of emergency and elective colorectal cases being performed by a certified colorectal surgeon | In low population-density areas, emergency colorectal procedures are more likely to be performed by non–colorectal surgeons |

| Gates et al., 200341 | United States | Survey of West Virginia rural surgeons | 27% of practice included obstetrics, urology, and orthopedics; also treated many medical problems |

| Gruber et al., 201545 | United States | Assessment of laparoscopic v. open colectomy for colorectal cancer in Nebraska | Rural patients were 40% less likely to receive a laparoscopic colectomy |

| Harris et al., 201046 | United States | Assessment of scope of practice for North and South Dakota general surgeons | Rural surgeons’ practice composed of 39.8% endoscopy and 25.6% general surgery procedures Surgeons in smaller centres performed more endoscopy and non–general surgery procedures (obstetrics, orthopedics, urology, and vascular) |

| Heneghan et al., 200547 | United States | Assessment of practice and motivations of rural compared with urban surgeons | Rural surgeons were more likely to perform cesarean deliveries and gynecologic procedures Endoscopy accounts for a greater proportion of rural practice |

| Hilsden et al., 200719 | Canada | Determine provincial and regional differences in endoscopy providers | Canadian rural surgeons completed 51% of all endoscopic procedures v. 35% by gastroenterologists |

| Komaravolu et al., 201949 | United States | Assessment of the proportion of colonoscopies completed by general surgeons on rural patients | In rural areas, general surgeons performed 21.9% of all colonoscopies, whereas urban surgeons performed 3.1% of all urban colonoscopies |

| Kozhimannil et al., 201573 | United States | Rates of births being attended by general surgeons | In low-volume centres, births were more likely to be attended by a general surgeon than by an obstetrician–gynecologist |

| Luck et al., 201511 | Australia | Completion of emergency neurosurgical procedures by rural surgeons | Rural centres with resident general surgeons who completed all emergency neurosurgical procedures needed before transfer |

| Micieli et al., 201520 | Canada | Assessment of temporal artery biopsies by region in Ontario | Surgeons were more often the provider in less populated regions |

| Moore et al., 201655 | United States | Assessment of the frequency of laparoscopic colectomies performed by rural surgeons | Rural surgeons did not complete a high volume of colectomies; they were not frequently performed laparoscopically |

| Nealeigh et al., 202118 | United States | Scoping review of literature surrounding American rural and deployed military surgeons | Approximately 20.7% of rural civilian surgical case volume is non–core general surgery, excluding endoscopy |

| Reynolds et al., 200374 | United States | Assessment of training procedures in a rural community training centre | Graduating residents completed a high volume of advanced laparoscopic procedures in a rural setting |

| Rinker et al., 199875 | United States | Assessment of local surgery training in emergency craniotomy | Based on need, a group of general surgeons completed training for emergency craniotomy by a neurosurgeon Over a follow-up period, 7 performed due to instability |

| Ritchie et al., 199957 | United States | Assessment of scope of practice between rural and urban surgeons | Rural surgeons completed more endoscopy procedures, laparoscopy, and non–general surgery procedures |

| Sariego, 200076 | United States | Review of a single rural surgeon’s endoscopic practice | Endoscopy accounted for 24% total procedures |

| Schroeder et al., 202023 | Canada | Assessment of scope of practice of all rural Canadian surgeons | Rural surgeons were more likely to perform procedures outside of core general surgery, including endoscopy, orthopedics, and obstetrics |

| Sticca et al., 201259 | United States | Evaluation of North Dakota rural surgeons’ scope of practice | 46 052 procedures completed by rural surgeons, 12.3% were non–general surgery procedures |

| Stiles et al., 201960 | United States | Survey of rural surgeons, assessing scope of practice and preparedness | 43 of the rural surgeons surveyed frequently performed procedures from other specialties, including gynecology, otolaryngology, urology, and vascular surgery |

| Stinson et al., 202161 | United States | Assessment of procedures most frequently performed by a rural surgeon | 38 958 procedures were assessed; 61.6% were endoscopic, cholecystectomy, or hernia repair related |

| Tulloh et al., 200177 | Australia | Assessed the caseload of 3 rural general surgeons | Practice patterns varied between the 3 surgeons; frequently performed types of procedures included endoscopy, urology, vascular, and obstetrics |

| Valentine et al., 201164 | United States | Examination of the scope of practice of American general surgeons between 2007 and 2009 | Rural surgeons performed significantly more endoscopic procedures; urban surgeons performed more laparoscopic procedures and abdominal procedures |

| VanBibber et al., 200665 | United States | Comparison of rural with urban general surgery scope of practice | Rural surgeons were less likely to perform procedures on the stomach, pancreas, liver, or esophagus; they performed a greater number of obstetric and gynecologic, vascular, and head and neck procedures, which accounts for a greater proportion of inpatient procedures |

| Zuckerman et al., 200766 | United States | Telephone survey of rural and urban surgeons assessing endoscopy volume | 74% of rural surgeons performed more than 50 endoscopic procedures in a year v. 33% of urban surgeons; 42% of rural surgeons completed > 200 procedures compared with 12% of urban surgeons |

It was found that rural surgeons play an important role in the treatment of trauma. They are routinely the surgical provider of thoracoabdominal trauma, consistent with larger centres but without the support of surgical specialties, such as neurosurgery and vascular surgery.6,11,67,69,71 The scope of rural general surgery practice extends beyond procedural care alone, including workup and management of medical conditions. For example, rural general surgeons are often responsible for endoscopic gastrointestinal workup, as gastroenterologists are not commonly present in rural communities.28 In addition to other specialty procedures, endoscopy typically comprises a significant proportion of a rural general surgeons’ workload, up to 50% of all procedures.19,23,28,29,46,47,49,61,64,66,68,70–72,76

Rural surgical outcomes

Thirteen studies assessed the clinical outcomes of rural surgeons (Table 7). Additionally, several authors reviewed the outcomes of emergency procedures not usually within general surgery practice, including vascular surgery and neurosurgery.11,67,75,82 These authors focused on rural and remote areas where delays in intervention would likely result in increased morbidity or mortality. In general, these patients had good clinical outcomes regardless of the fact that the specialty procedures were completed by general surgeons. Others assessed clinical outcomes of frequently completed procedures and found the complication rates of rural surgeons to be comparable to those of their higher-volume urban counterparts in both adult and pediatric patient populations.31,42,56,76,80 One study of a Canadian trauma system found the presence of a surgeon in the community improved trauma outcomes and effective transfers to tertiary care, their patients being more likely to arrive hemodynamically stable. These patients also had a high likelihood of requiring multidisciplinary management across several surgical disciplines, suggesting that many trauma patients treated in centres with general surgeons are obtaining appropriate care within the capabilities of their local centre.6

Table 7.

Summary of findings for clinical outcomes

| Publication | Country | Context | Primary findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ang et al., 202067 | Australia | Assessment of emergency vascular procedures completed at a rural Australian hospital | 16 patients were unable to be transferred and received emergency vascular procedures; 69% survived with limb salvage |

| Ball et al., 20096 | Canada | Assessment of outcomes of level III trauma centres in Alberta, Canada | Patients who arrived from a level III trauma centre more often had a surgical assessment, 13% required laparotomy alone, and 87% required assessment from other surgical specialists These patients were less likely to arrive unstable compared with level IV centres Rural surgeons were appropriately treating and transferring trauma patients |

| Chaudhary et al., 201731 | United States | Comparison of outcomes in emergency general surgery and trauma between rural and urban centres | Rural patients had higher odds of mortality, were less likely to have major complications, and remained in hospital an average of 0.5 days longer at a cost of $98/d more; the authors concluded that despite statistical significance, they were not clinically significant |

| Gadzinski et al., 201342 | United States | Comparison of postoperative outcomes among surgical patients treated at a critical access hospital compared with other hospitals | Among general surgery patients, there were no statistically significant increased adverse postoperative outcomes among patients treated in critical access hospitals; patients on average were discharged earlier, but their care did cost 9.9%–30.1% more |

| Galandiuk et al., 200678 | United States | Comparison of quality indicators between rural and urban surgeons | Higher volume rural colorectal surgeons have comparable outcomes compared with urban surgeons in cases of colectomy Rural surgeons had similar outcomes compared with urban surgeons when assessing cholecystectomy and endoscopy |

| Luck et al., 201511 | Australia | Assessment of emergency neurosurgical procedures completed in rural Australia | 161 patients required emergency neurosurgical procedures in a rural setting with general surgery Poor outcomes were attributed to distance of patient transfer and the remote location of trauma; outcomes reviewed as acceptable based on those factors |

| Natafgi et al., 201756 | United States | Comparison of adverse events surgical patients in critical access hospitals compared with larger centres | Surgical patients at critical access hospitals had similar rates of reported adverse events compared with larger centres |

| Pandit et al., 201679 | United states | Assessment of rural v. urban surgical management of ulcerative colitis | Patients with ulcerative colitis managed in urban centres with colorectal surgery were less likely to have complications than when managed in rural settings |

| Quinn and Read, 201780 | Australia | Assessment of pediatric surgical outcomes managed at rural sites in Australia | Complication rates of orchidopexy under the age of 5 years and inguinal hernia under the age of 1 year had the same or nearly the same complication rates as the published gold standard |

| Rinker et al., 199875 | United States | Outcomes of locally performed craniotomy by general surgeons at a level III trauma centre | Based on need, a group of general surgeons completed training for emergency craniotomy by a neurosurgeon In the follow-up, 7 patients required emergency craniectomy as deemed appropriate by a remote neurosurgeon; good clinical outcomes resulted in patients deemed too unstable to transfer to specialized neurosurgical care |

| Rossi et al., 201181 | United States | Assessment of complication rates of procedures completed in critical access hospitals | Review of 100 consecutive carotid endarterectomy, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, hysterectomy, and inguinal hernia; overall complication rate of 4% |

| Sariego, 200076 | United States | Review of a single rural surgeon’s endoscopic practice | 276 endoscopic procedures were completed; 75% pertinent diagnosis were identified; no complications |

| Treacy et al., 200582 | Australia | Assessment of emergency neurosurgical procedures performed in remote Australia | 305 emergency neurosurgical procedures were completed; overall outcomes were acceptable |

One trend identified in the literature is a lower rate of laparoscopic colectomies completed at rural hospitals. Colon and rectal procedures are less likely to be performed by a specialist colorectal surgeon, and patients in rural centres are less likely to receive a laparoscopic procedure. 45,55 Another study identified patients with ulcerative colitis treated by non–colorectal specialists as more frequently experiencing complications.79

Rural surgical workforce characteristics

Twenty-five papers discussed the characteristics of the rural surgical workforce (Table 8). In the US and Canada, several authors observed that rural surgeons tend to be male, internationally trained, and older than their urban counterparts.23,41,48,52,63 The literature also identified a decrease in the number of general surgery graduates entering rural surgical practice, as well as the loss of rural surgical programs.22,29,39,43,50,85 Studies reviewing advertised surgical position vacancies identified service gaps more frequently in rural positions, often with long-standing vacancies and reliance on locum tenens surgeons as the primary surgical workforce.26,29,38,62 Several studies have been conducted to understand what factors help predict a general surgeon’s decision to practise in a rural setting. The most frequently cited predictor for choosing rural surgical practice is having grown up in a rural area or having a partner who grew up in a rural area.24,36,41,48,66 Rates of rural clerkship and resident rotations were higher among surgeons who chose rural practice settings than those working in urban settings.48

Table 8.

Summary of findings for rural surgical workforce characteristics

| Publication | Country | Context | Primary findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breon et al., 200329 | United States | Assessment of need for rural surgeons in Iowa | 64% of rural surgeons were recruiting a partner compared with 50% of urban surgeons 77% of rural surgeons felt that there was a shortage in the rural workforce |

| Bruening and Maddern, 199824 | Australia | Characterizing the rural Australian workforce | 134 male surgeons; 3 female surgeons; 41% of rural surgeons were raised in a rural setting |

| Decker et al., 201383 | United States | Assessment of the available general surgery positions in Wisconsin and Oregon | 71 positions available; 46% were rural, and only 18% required fellowship training; 67% of graduates enter fellowships |

| Doty et al., 200636 | United States | Survey to determine the characteristics of graduates from a New York general surgery program | Surgeons raised in a rural area were more likely to choose a career in rural surgery |

| Doty et al., 200938 | United States | Survey of rural hospitals recruitment of general surgeons and use of locum tenens surgeons | 56% of surveyed hospitals recruited for a general surgeon; 30% have been unable to fill the position and 20% used locum tenens surgeons |

| Ellison et al., 202139 | United States | Estimation of the American general surgeon work force needs | Population growth in the US will outpace the number of trained general surgeons; the increased need in urbanized areas will negatively affect rural recruitment |

| Gates et al., 200341 | United States | Survey of West Virginia rural surgeons | Only 5 female rural surgeons Average age of rural surgeons was 57; rural surgeons were more likely to have been raised in a rural community |

| Germack et al., 201943 | United States | Assessment of the impact from the closure of rural hospitals on local communities | In the years before a hospital closure, there is a loss of general surgery capability; at the time of closure there is a substantial loss of all specialties remaining in the community |

| Glenn et al., 198884 | United States | Defining the community requirements to support a general surgeon | To support a general surgeon, a population base of 15 000 and 11 referring physicians is required |

| Ingraham et al., 202185 | United States | Survey of all US acute care hospitals, outlining emergency general surgery coverage gaps | 2811 hospitals responded; 279 hospitals are unable to provide 24/7 emergency surgical services Rural hospitals and nonteaching hospitals were less likely to provide 24/7 emergency surgical coverage |

| Kwakwa and Jonasson, 199750 | United States | Characteristics of the American general surgical workforce | 19 791 general surgeons were identified; only 6.9% of surgeons work in a rural area |

| Jarman et al., 200948 | United States | Factors correlating to a resident’s choice of rural practice | Rural surgeons were more likely to be male Completing high school or university in a rural setting correlated to selecting a rural career Completion of a rural clerkship was also correlated to pursuing a career in rural general surgery |

| Lynge, 200852 | United States | Defining the rural general surgery workforce | Rural surgeons were more likely to be male, female surgeons were less likely to work in a rural setting, and, on average, rural surgeons were older |

| Roos, 198321 | Canada | Defining the impact of rural surgeons in local utilization of surgical services | Arrival of a surgeon in a rural area increased the utilization of surgical services in that area, and decreased the number of procedures completed outside of the home centre Departure of a surgeon increased the workload of their surgical colleagues but did not decrease the local utilization of surgical services |

| Roos et al., 199686 | Canada | Determining optimal workforce planning in rural general surgery | Defined 3 methods of determining the number of surgeons The first model was based on an optimal ratio of surgeons to population The second assessed the number of procedures where patients travelled out of their home communities to receive care The third model analyzed recruitment needs based on an assessment of the proportion of the population requiring surgery compared with other areas |

| Rourke, 199822 | Canada | Assessment of surgical services in small Ontario hospitals | Between the years 1988 and 1995 there was a decrease in 24/7 coverage for general surgery, but the number of procedures completed increased; there were fewer general surgeons practising in these smaller communities |

| Schroeder et al., 202023 | Canada | Assessment of the scope of practice of all rural Canadian surgeons | Rural surgeons were older on average, there were fewer female surgeons, and rural surgeons were more likely to be international graduates |

| Shanmugakumar et al., 201726 | Australia | Characterizing the rural general surgery workforce in Western Australia | 18 hospitals completed the survey; 89% were serviced by fly-in and fly-out surgical services, and 2 hospitals had a resident general surgeon |

| Stringer et al., 202062 | United States | Description of the loss of surgical workforce at rural hospitals in Kansas | Most rural sites in Kansas did not have a permanent surgeon Lack of surgical services at rural and frontier hospitals leads to a higher amount of patient transfers |

| Thompson et al., 200563 | United States | Characterizing the American general surgery workforce | Rural surgeons were more likely to be male and older, and were more likely to be international medical graduates |

| Zuckerman, 200766 | United States | Telephone survey of rural and urban surgeons, assessing endoscopy volume and training needs | 51% of rural surgeons were from a rural background v. 38% of urban surgeons |

Rural surgical training

A total of 22 studies assessed the training of rural surgeons (Table 9). Rural surgical training literature focused on the need for a broad-based general surgery training program to ensure practice-ready surgeons. Multiple studies identified surgical residents graduating with insufficient confidence in performing procedures outside of core general surgery but most often required in rural settings.47,66,90 A Canadian survey of surgery residents in their final year of training found that 37% of residents planned to move directly into practice, and many indicated they did not feel comfortable with orthopedic, plastic surgery, obstetric or gynecologic procedures.90

Table 9.

Summary of findings for rural surgical training

| Publication | Country | Context | Primary findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burkholder and Cofer, 200730 | United States | Assessment of rural training perceptions and availability of rural training opportunities in American general surgical residency programs | 36% of training programs have a rural track Research-based programs were less likely to have a rural track; program directors were less likely to indicate rural training as a part of their program’s mission, and they were less likely to indicate that there is a shortage of rural surgeons Opinions were divided on the adequacy of a broad general surgery training program in preparation for rural surgery practice Program directors stated that orthopedics and gynecology are important aspects of a rural training program |

| Cofer et al., 201132 | United States | Survey of rural surgeons’ attitudes toward training | 20% of the 237 respondents completed fellowship training; reasons included to obtain additional skills or increase in comfort 81% indicated that there would be benefit to rural track residency programs; 80% indicated that their ideal candidate would not need subspecialty training |

| Deal et al., 201887 | United States | Needs assessment of skills in rural surgery | 237 rural surgeons responded; 82% stated that rural surgery opportunities during residency training is important The following training needs were identified: endoscopy, advanced laparoscopy, trauma management, wound care, and basic non–general surgery procedures (cesarean delivery, carpal tunnel, amputation) |

| Deveney and Hunter, 200934 | United Stated | Description of the rural training model in Oregon and its outcomes | One-year training program in a rural setting with formal training rotations in non–general surgery specialties (obstetrics and gynecology; urology; ear, nose, and throat) 10 graduates completed the program; 5 were working in rural or small community practices |

| Deveney et al., 201335 | United States | Outcomes of a rural training model in Oregon | Residents who completed the rural track were more likely to remain in general surgery, as opposed to subspecialty training regardless of career goals at the start of residency; they were also more likely to enter rural practice |

| Doty et al., 200636 | United States | Survey of graduates from a rural-based training program on practice setting and demographics; assessment of procedure logs compared with national average | Graduates of a rural broad-based training program were more likely to enter rural practice; 83% of practising graduates reported working in a rural setting, and 71% reported that they were raised in a rural community Assessment of procedure logs indicated that graduates performed significantly more non–general surgery procedures compared with the national average |

| Fader and Wolk, 200988 | United States | Description of a residency program’s rural surgery track | Dedicated training year at a rural hospital in preparation for rural or international practice Hospital characteristics including limited number of trainees outside of general surgery Additional areas of training in the sixth year were tailored to the needs of the hospital |

| Giles et al., 200989 | United States | Assessment of a general surgery program’s rural rotation | The rural rotation was well received and educational according to a resident survey Improved endoscopy exposure for residents; the rotation increased resident interest in rural surgery as a career choice |

| Gillman and Vergis, 201390 | Canada | Survey of graduating residents comfort level when performing general surgery and non–general surgery procedures | Most residents were comfortable with breast, gallbladder disease, and colorectal procedures; few were comfortable with more advanced procedures, including gastrectomy, advanced laparoscopy, and procedures outside of core general surgery |

| Glenn et al., 201744 | United States | Tele-mentoring interest in rural surgery | 78.9% of survey respondents indicated that tele-mentoring was useful for acquiring new skills, or dealing with unexpected intraoperative findings |

| Halverson et al., 201491 | United States | Evaluation of a multidisciplinary skills course for rural surgeons | Mentoring and teaching of skills beyond the normal scope of general surgery; overall, it was felt to be beneficial to practising surgeons |

| Heneghan et al., 200547 | United States | Assessment of practice and motivations of rural compared with urban surgeons | In a survey of 421 surgeons, rural surgeons indicated that they would have benefited from non–general surgery training in residency and would have equally benefited from advanced laparoscopy training |

| Jarman et al., 200948 | United States | Assessment of the characteristics of general surgery graduates | 79% of practising rural surgeons had completed a rural clerkship, compared with 37% of urban surgeons |

| Kent et al., 201592 | United States | Description of rural training program | Developed a rural training program with broad surgical specialty exposure, including exposure to rural mentorship and an emphasis on endoscopy, obstetrics, and orthopedics; 18 months of rural rotations |

| Landercasper et al., 199751 | United States | Comparison of procedure logs from practising rural surgeons compared with graduating residents | Residents completed fewer gynecologic and orthopedic procedures than practising rural surgeons |

| Milligan et al., 200993 | United States | Assessment of a rural surgical rotation in senior general surgery residency | Resident case logs from participating residents more similar to caseload of rural surgeon Following implementation of rotation, more graduates selected rural practice as a career |

| Mercier et al., 201953 | United States | Assessment of rural training opportunities and description of new rural track | 27 programs required rural rotations, 10 offered rural electives, and 4 had designated rural track match positions Designed program for residents to complete training at rural sites throughout their 5-year program |

| Moesinger and Hill, 200954 | United States | Description of 1-year rural residency program | One-year fellowship to be completed in postgraduate year 4 for residents interested in rural practice; rotations within general surgery and non–general surgery specialties |

| Reynolds et al., 200374 | United States | Assessment of training procedures in a rural community training centre | Graduating residents completed a high volume of advanced laparoscopic procedures in a rural training setting and reported confidence with those procedures |

| Stiles et al., 201960 | United States | Survey of rural surgeons assessing scope of practice and preparedness | 43 rural surgeons surveyed frequently performed procedures from other specialties, including gynecology, otolaryngology, urology, and vascular, and reported preparedness to perform these procedures on graduation |

| Undurraga Perl et al., 201594 | United States | Assessment of procedures performed by general surgeons in critical access hospitals, compared with those performed by residents Compared the procedure logs of residents who completed a rural rotation with those who did not |

Practising general surgeons performed a significantly higher proportion of endoscopy, hernia, biliary, and gynecology than residents; residents completed more cardiothoracic, vascular, liver, and pancreas procedures Residents who completed a rural rotation completed more procedures than nonrural residents |

| Zuckerman, 200766 | United States | Telephone survey of rural and urban surgeons, assessing endoscopy volume and training needs | 63% of rural surgeons wanted additional endoscopy training in their residency compared with 43% of urban surgeons |

The American training literature identified several pilot programs aimed at providing additional rural-oriented training; these included a rural year for fourth-year students, and a rural rotation with an emphasis on endoscopy exposure.34,35 Results of those programs include more analogous caseloads of residents and practising surgeons, increased likelihood of selecting rural surgery as a career, and increased self-reported preparedness for rural practice, including those procedures that fall outside of general surgery. 30,34,35,37,53,54,60,74,88,89,92–94 Canadian literature is lacking regarding general surgery training.

Beyond residency training, continuing education was consistently noted as an important aspect of upgrading and maintaining skills, including laparoscopic colon surgery and others not within core general surgery. Programs were well received by rural surgeons, with participants indicating these programs would broaden the care they would be able to provide to local patients.91 Telementoring was also identified as an educational approach that could benefit rural surgeons in learning new skills or managing unexpected intraoperative findings.44

Rural surgery recruitment and retention

Six studies examined barriers to selecting rural surgery as a career and rural surgeon retention (Table 10). These studies identified on-call burden and professional isolation as common areas leading to career dissatisfaction. A Canadian study by Ahmed and colleagues27 identified difficulty in accessing resources, with perceived impediments in providing high-quality patient care leading to reduced career satisfaction and negatively affecting rural surgeon retention. Family considerations were also found to affect rural retention, particularly surgeon’s concerns regarding their children’s education and finding spousal employment. Studies also identified positive retention aspects of rural practice, including the sense of community, the ability to establish long-lasting relationships with their patients, and rural settings being noted to provide a positive and preferable environment for raising a family.48,72

Table 10.

Summary of findings for rural surgery recruitment and retention

| Publication | Country | Context | Primary findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed et al., 201227 | Canada | Survey of Canadian general surgeons assessing career satisfaction | Rural surgeons cited on-call burden and volume of patients as causes for career dissatisfaction |

| Bruening and Maddern, 199824 | Australia | Survey of rural Australian surgeons | 137 surveys completed 85 reported dissatisfaction with the amount of time on call, 74 reported peer isolation, and 62 stated that they had challenges with their children’s schooling |

| Gates et al., 200341 | United States | Survey of West Virginia surgeons | 88 surveys completed 23% of rural surgeons would leave medicine; 32% stated that rurality had an adverse effect on their practice |

| Heneghan et al., 200547 | United States | Assessment of practice and motivations of rural surgeons compared with urban surgeons | Rural surgeons were more likely to experience professional isolation, felt a lack of local surgical and medical support, were less likely to report adequate vacation coverage, had an unacceptable call schedule, and had difficulty recruiting colleagues |

| Ricketts, 201095 | United States | Assessment of the migration of rural general surgeons | General surgeons who moved over the course of the study period were more likely to move to areas with more physicians and improved economics |

| Shively and Shively, 200558 | United States | Assessment of threats to rural surgery at a single Kentucky hospital | Rural surgeons report difficulty in finding employment for their spouse and professional isolation as barriers to pursuing a career in rural surgery |

Discussion

Defining rurality in a health care context

In Canada, the low population density and distribution of population, with few large metropolitan areas, make the definition of rurality difficult to delineate in the context of health care. For example, a community of 5000 people in southern Ontario is often not more than 1 hour from a tertiary care centre; however, a community of 5000 in Nunavut is thousands of kilometres from a tertiary care centre. Because of the unique features of Canadian geography, numerous institutions have worked to define rurality.

Statistics Canada defines rurality as the area that remains after the delineation of population centres (small towns with a 1000–29 999 population, medium urban centres with a 30 000–99 999 population, and large urban centres with a population > 100 000) with a population density of less than 400 people per square kilometre.96 In a health care context, this definition is unable to capture the nuances and impacts of proximity that larger tertiary care centres have on the delivery of health care. Statistics Canada has worked to develop a “remoteness index” to try to capture this nuance by developing a score based on proximity to other centres.96 Other population cut-offs have been used by provinces to set out criteria for rural retention programs. In Ontario, researchers use the Rural Index for Ontario, which stratifies communities based on their size and distance to secondary and tertiary care.97 The Canadian Institute for Health Information employs a hybrid model that uses a population cut-off of 10 000 and further stratifies communities by metropolitan influence, based on the percentage of residents who commute to and from a metropolitan area for work.98 The literature identified in this review highlights and emphasizes the importance of including metropolitan influence in defining rurality in surgical care.

Defining the rural general surgeon’s role and scope of practice

Most of the current literature on rural surgery is American, and Canada’s population distribution and physical geography are vastly different. Some of the challenges faced by rural surgeons in Canada are similar to those experienced by their American counterparts; however, it is clear that additional population distribution and geographic factors substantially affect rural Canadian surgeons. This review identified a single pre-existing definition of a rural or isolated surgeon in an American military context. Although this definition was robust and specific, it did not address key elements that are required in a Canadian context, such as the scope of practice and the unique role that a Canadian rural surgeon plays within their community. The definition was further limited by its applicability to Canada, the exclusion of Canadian literature, and the inclusion of deployed military surgeons. The definition of a Canadian rural surgeon must also include the role of the surgeon in the local health care system, the unique scope of practice, and the community characteristics.

Canadian rural surgeons are not only the primary surgeon but also act as an important critical service access point in both emergency and elective practice settings. In the example of trauma care resource access and utilization, Canadian surgeons provided appropriate care in their home community and effectively transferred patients requiring a higher level of care, referring multisystem trauma cases and caring for single-system trauma patients locally.6 Other studies have suggested that general surgeons in rural settings are more likely to perform endoscopy and complete diagnostic workup for gastrointestinal disorders than their urban counterparts.28 In this role, rural surgeons are an important initial access point to subspeciality surgery and medicine, acting as gatekeepers and facilitators of surgical referral to higher-level complex tertiary and quaternary care. Our literature review identified a lower rate of laparoscopic colectomies in the rural setting, which likely represents the older demographic of general surgeons, and this trend may shift as new graduates enter rural practice. Further, our review did identify advanced laparoscopic training as a suggested skill when training rural surgeons, and this can be adequately addressed in rural streams. Within the literature, the most frequently addressed theme of rural surgery is the extended scope of practice, with orthopedics, obstetrics and gynecology, and urology being the most frequently included specialties outside of general surgery. Within Canada, the distribution and diversity of procedures performed by rural surgeons is dependent on the needs of the community and allocation of other local surgical and health care resources as opposed to a one-size-fits-all model. Finally, characteristics of the community that a rural surgeon serves can also affect their extended scope of practice, particularly the influence and access to higher-level care in nearby metropolitan centres. Patient preference also plays a critical role, as rural patients may identify a strong preference for surgery close to home regardless of their knowledge of surgical outcomes. Quality of life issues, including proximity to family and social supports, and capacity and expense for medical travel are critically important and often overlooked aspects of surgical care in rural communities.99,100

Rural general surgery training, recruitment, and retention considerations

The literature clearly identifies a gap in the surgical care needs of rural patients and the accessibility of trained providers. An aging and shrinking rural surgical workforce combined with decreased confidence of new graduates pursuing rural practice inevitably results in a widening of the access gap among rural surgical patients. Rural general surgeons provide critical services, with improvements in trauma patient outcomes and equivalent surgical care outcomes to those of their high-volume urban counterparts in core general surgery procedural competencies. Recruitment of rural-oriented surgical trainees combined with training opportunities targeted to build rural surgical skill sets with an extended scope of practice may encourage trainees to pursue a career in rural general surgery.

Practice isolation, call burden, and burnout are challenges in rural communities. Communicating these issues in the medical community and the public at large is critical. Authors discussing equitable care distribution and access within the surgical community have called for a shift to group practice and networked care models in rural communities. 101,102 Considering shifts in remuneration models for rural surgeons away from fee-for-service models to salaried or other alternative payment models may also support recruitment to communities with lower practice volumes, as well as a shift to team-based care models. Smaller communities with insufficient case volumes to support multiple general surgeons may also extend the surgical workforce by including Family Physicians with Enhanced Surgical Skills (FP-ESS) training working alongside and in collaboration with general surgeons, ensuring appropriate access to specialist and generalist care in smaller rural and remote communities. 101,103 Supporting healthy multisurgeon rural surgical programs may improve the work–life balance of rural surgeons and build continuing medical education opportunities for surgeons to provide the high-quality care rural communities deserve. Implementing these models of care in rural communities may help overcome practice isolation and burnout challenges affecting retention of rural general surgeons and support the sustainability of rural surgical programs.

Conclusion

A rural general surgeon in Canada is defined as a surgical specialist who works in smaller (population < 30 000) or remote communities with limited metropolitan influence. Rural general surgeons apply the foundational principles of surgery, combining core general surgery training with additional surgical skills to serve the unique surgical needs of their community. In addition to providing emergent and elective general surgical services, they provide care beyond what is considered the core scope of general surgery practice and optimize care access close to home for rural patients. They act as a surgical care access point for more complex subspecialty surgical presentations. Rural general surgeons provide critical access to emergency and elective surgical expertise to positively affect patient outcomes. Training programs and health systems must support the unique needs and roles of these providers to provide high-quality equitable care access to rural Canadians.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the work of Lisa Allen, who assisted with the preparation of the manuscript, and the work of Alla Iansavitchene, who assisted with the literature search.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Lyndsay Glass is a member of the Canadian Association of General Surgeons Rural Surgery Committee. Peter Miles is a member and past chair of the Canadian Association of General Surgeons Rural Committee. Lauren Smithson is chair of the Advisory Council for Rural Surgery, American College of Surgeons. Evan Wong reports a Canadian Association of General Surgeons operating grant. Caitlin Champion reports a Skin Investigation Network of Canada Team Development Grant, and is a member of the Canadian Association of General Surgeons Rural Surgery Committee and co-chair of the Continuing Professional Development Committee. No other competing interests were declared.

Contributors: Lyndsay Glass, Rebecca Afford, Quinn Gentles, Sarah MacVicar, Peter Miles, Roy Kirkpatrick, Lauren Smithson, Mark Walsh, Stephen Hiscock, Evan Wong, and Caitlin Champion contributed to the conception and design of the work. Lyndsay Glass, Malcolm Davidson, and Emily Friedrich contributed to the data acquisition and analysis. Lyndsay Glass, Malcolm Davidson, Emily Friedrich, and Caitlin Champion contributed to interpretation of the data and drafting the manuscript. Rebecca Afford, Sarah MacVicar, Quinn Gentles, Peter Miles, Roy Kirkpatrick, Lauren Smithson, Mark Walsh, Stephen Hiscock, and Evan Wong reviewed and revised the manuscript critically. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Supply, distribution and migration of physicians in Canada, 2020 — historical data. Ottawa: CIHI; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bollman RD, Clemenson HA. Structure and change in Canada’s rural demography: an update to 2006. Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin 2008;7:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moazzami B. Strengthening rural Canada: fewer & older: population and demographic challenges across rural Canada. A pan-Canadian report. Toronto: Essential Skills Ontario; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.In pursuit of health equity: defining stratifiers for measuring health inequality. Ottawa: Canadian Institute For Health Information; 2018:69. [Google Scholar]

- 5.DesMeules M, Pong RW, Guernsey Read, et al. Rural health status and determinants in Canada. Health in Rural Canada 2011;568. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ball CG, Sutherland FR, Dixon E. Surgical trauma referrals from rural level III hospitals: Should our community colleagues be doing more, or less? J Trauma 2009;67:180–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kornelsen J, Grzybowski S, Iglesias S. Is rural maternity care sustainable without general practitioner surgeons? Can J Rural Med 2006;11:218–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iglesias A, Iglesias S, Arnold D. Birth in Bella Bella: emergence and demise of a rural family medicine birthing service. Can Fam Physician 2010;56:e233–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grzybowski S, Stoll K, Kornelsen J. Distance matters: a population based study examining access to maternity services for rural women. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller KJ, Couchie C, Ehman W, et al. Rural maternity care. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2012;34:984–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luck T, Treacy PJ, Mathieson M, et al. Emergency neurosurgery in Darwin: still the generalist surgeons’ responsibility. ANZ J Surg 2015;85:610–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Covidence systematic review software. Veritas Health Innovation; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cofer JB, Burns RP. The developing crisis in the national general surgery workforce. J Am Coll Surg 2008;206:790–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doty BC, Heneghan S, Zuckerman R. Starting a general surgery program at a small rural critical access hospital: a case study from southeastern Oregon. J Rural Health 2007;23:306–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doty B, Zuckerman R, Finlayson S, et al. General surgery at rural hospitals: a national survey of rural hospital administrators. Surgery 2008;143:599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musgrove KA, Abdelsattar JM, Lemaster SJ, et al. Optimal resources for rural surgery. Am Surg 2020;86:1057–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong K, Petchell J. Resources for managing trauma in Rural New South Wales, Australia. ANZ J Surg 2004;74:760–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nealeigh MD, Kucera WB, Artino AR, et al. The isolated surgeon: a scoping review. J Surg Res 2021;264:562–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hilsden RJ, Tepper J, Moayyedi P, et al. Who provides gastrointestinal endoscopy in Canada? Can J Gastroenterol 2007;21:843–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Micieli JA, Micieli R, Margolin E. A review of specialties performing temporal artery biopsies in Ontario: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open 2015;3:E281–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roos LL. Supply, workload and utilization: a population-based analysis of surgery in rural Manitoba. Am J Public Health 1983;73:414–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rourke JTB. Trends in small hospital medical services in Ontario. Can Fam Physician 1998;44:2107–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schroeder T, Sheppard C, Wilson D, et al. General surgery in Canada: current scope of practice and future needs. Can J Surg 2020;63: E396–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruening MH, Maddern G. A profile of rural surgeons in Australia. Med J Aust 1998;169:324–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Sullivan B, McGrail M, Russell D. Rural specialists: the nature of their work and professional satisfaction by geographical location of work. Aust J Rural Health 2017;25:338–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shanmugakumar S, Playford D, Burkitt T, et al. Is Western Australia’s rural surgical workforce going to sustain the future? A quantitative and qualitative analysis. Aust Health Rev 2017;41:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed N, Conn LG, Chiu M, et al. Career satisfaction among general surgeons in Canada: a qualitative study of enablers and barriers to improve recruitment and retention in general surgery. Acad Med 2012;87:1616–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baldwin L, Rosenblatt R, Schneeweiss R, et al. Rural and urban physicians: Does the content of their medicare practices differ? J Rural Health 1999;15:240–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Breon TA, Scott-Conner CEH, Tracy RD. Spectrum of general surgery in rural Iowa. Curr Surg 2003;60:94–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burkholder HC, Cofer JB. Rural surgery training: a survey of program directors. J Am Coll Surg 2007;204:416–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaudhary MA, Shah AA, Zogg CK, et al. Differences in rural and urban outcomes: a national inspection of emergency general surgery patients. J Surg Res 2017;218:277–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cofer JB, Petros TJ, Burkholder HC, et al. General surgery at rural Tennessee hospitals: a survey of rural Tennessee hospital administrators. Am Surg 2011;77:820–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cook MR, Hughes D, Deal SB, et al. When rural is no longer rural: Demand for subspecialty trained surgeons increases with increasing population of a non-metropolitan area. Am J Surg 2019;218:1022–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deveney K, Hunter J. Education for rural surgical practice: the Oregon Health & Science University Model. Surg Clin North Am 2009;89:1303–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deveney K, Deatherage M, Oehling D, et al. Association between dedicated rural training year and the likelihood of becoming a general surgeon in a small town. JAMA Surg 2013;148:817–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doty B, Heneghan S, Gold M, et al. Is a broadly based surgical residency program more likely to place graduates in rural practice? World J Surg 2006;30:2089–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doty B, Zuckerman R, Borgstrom D. Are general surgery residency programs likely to prepare future rural surgeons? J Surg Educ 2009;66:74–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doty B, Andres M, Zuckerman R, et al. Use of locum tenens surgeons to provide surgical care in small rural hospitals. World J Surg 2009;33:228–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ellison EC, Satiani B, Way DP, et al. The continued urbanization of American surgery: a threat to rural hospitals. Surgery 2021;169:543–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Etzioni DA, Cannom RR, Madoff RD, et al. Colorectal procedures: What proportion is performed by American board of Colon and rectal surgery-certified surgeons? Dis Colon Rectum 2010;53:713–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gates RL, Walker JT, Denning D. Workforce patterns of rural surgery in West Virgina. Am Surg 2003;69:367–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gadzinski AJ, Dimick JB, Ye Z, et al. Utilization and outcomes of inpatient surgical care at critical access hospitals in the United States. JAMA Surg 2013;148:589–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Germack HD, Kandrack R, Martsolf GR. When rural hospitals close, the physician workforce goes. Health Aff (Milwood) 2019; 38: 2086–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glenn IC, Bruns NE, Hayek D, et al. Rural surgeons would embrace surgical telementoring for help with difficult cases and acquisition of new skills. Surg Endosc 2017;31:1264–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gruber K, Soliman AS, Schmid K, et al. Disparities in the utilization of laparoscopic surgery for colon cancer in rural Nebraska: a call for placement and training of rural general surgeons. J Rural Health 2015;31:392–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harris JD, Hosford CC, Sticca RP. A comprehensive analysis of surgical procedures in rural surgery practices. Am J Surg 2010;200:820–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heneghan SJ, Bordley IVJ, Dietz PA, et al. Comparison of urban and rural general surgeons: motivations for practice location, practice patterns, and education requirements. J Am Coll Surg 2005; 201:732–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jarman BT, Cogbill TH, Mathiason MA, et al. Factors correlated with surgery resident choice to practice general surgery in a rural area. J Surg Educ 2009;66:319–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Komaravolu SS, Kim JJ, Singh S, et al. Colonoscopy utilization in rural areas by general surgeons: an analysis of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Am J Surg 2019;218:281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kwakwa F, Jonasson O. The general surgery workforce. Am J Surg 1997;173:59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Landercasper J, Bintz M, Cogbill TH, et al. Spectrum of general surgery in rural America. Arch Surg 1997;132:494–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lynge DC. Rural general surgeons: manpower and demographics. Surg Endosc 2008;22:1593–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mercier PJ, Skube SJ, Leonard SL, et al. Creating a rural surgery track and a review of rural surgery training programs. J Surg Educ 2019;76:459–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moesinger R, Hill B. establishing a rural surgery training program: a large community hospital, expert subspecialty faculty, specific goals and objectives in each subspecialty, and an academic environment lay a foundation. J Surg Educ 2009;66:106–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moore J, Pellet A, Hyman N, et al. Laparoscopic colectomy and the general surgeon. J Gastrointest Surg 2016;640–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Natafgi N, Baloh J, Weigel P, et al. Surgical patient safety outcomes in critical access hospitals: How do they compare? J Rural Health 2017;33:117–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ritchie WP, Rhodes RS, Biester TW. Work loads and practice patterns of general surgeons in the United States, 1995–1997: a report from the American Board of Surgery. Ann Surg 1999;230:533–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shively EH, Shively SA. Threats to rural surgery. Am J Surg 2005;190:200–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sticca RP, Mullin BC, Harris JD, et al. Surgical specialty procedures in rural surgery practices: implications for rural surgery training. Am J Surg 2012;204:1007–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stiles R, Reyes J, Helmer SD, et al. What procedures are rural general surgeons performing and are they prepared to perform specialty procedures in practice? Am Surg 2019;85:587–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stinson WW, Sticca RP, Timmerman GL, et al. Current trends in surgical procedures performed in rural general surgery practice. Am Surg 2021;87:1133–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stringer B, Thacker C, Reyes J, et al. Trouble on the horizon: an evaluation of the general surgeon shortage in rural and frontier counties. Am Surg 2020;86:76–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thompson MJ, Lynge DC, Larson EH, et al. Characterizing the general surgery workforce in rural America. Arch Surg 2005;140:74–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Valentine RJ, Jones A, Biester TW, et al. General surgery workloads and practice patterns in the united states, 2007 to 2009: a 10-year update from the American Board of Surgery. Ann Surg 2011;254: 520–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.VanBibber M, Zuckerman RS, Finlayson SRG. Rural versus urban inpatient case-mix differences in the US. J Am Coll Surg 2006;203: 812–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zuckerman R, Doty B, Bark K, et al. Rural versus non-rural differences in surgeon performed endoscopy: results of a national survey. Am Surg 2007;73:903–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ang ZH, Brown K, Rice M, et al. Role of rural general surgeons in managing vascular surgical emergencies. ANZ J Surg 2020;90:1364–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bappayya S, Chen F, Alderuccio M, et al. Caseload distribution of general surgeons in regional Australia: Is there a role for a rural surgery sub-specialization? ANZ J Surg 2019;89:672–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bintz M, Cogbill TH, Bacon J. Rural trauma care: role of the general surgeon. J Trauma 1996;41:462–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Campbell NA, Kitchen G, Campbell IA. Operative experience of general surgeons in a rural hospital. ANZ J Surg 2011;81:601–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Campbell NA, Franzi S, Thomas P. Caseload of general surgeons working in a rural hospital with outreach practice. ANZ J Surg 2013;83:508–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cogbill TH, Bintz M. Rural general surgery: a 38-year experience with a regional network established by an integrated health system in the midwestern United States. J Am Coll Surg 2017;225:115–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kozhimannil KB, Casey MM, Hung P, et al. The rural obstetric workforce in US hospitals: challenges and opportunities. J Rural Health 2015;31:365–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Reynolds FD, Goudas L, Zuckerman RS, et al. A rural community-based program can train surgical residents in advanced laparoscopy. J Am Coll Surg 2003;7515:620–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rinker CF, McMurry F, Groeneweg V, et al. Emergency craniotomy in a rural level III trauma center. J Trauma 1998;44:984–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sariego J. The role of the rural surgeon as endoscopist. Am Surg 2000;66:1176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tulloh B, Clifforth S, Miller I. Caseload in rural general surgical practice and implications for training. ANZ J Surg 2001;71:215–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Galandiuk S, Mahid SS, Polk HC, et al. Differences and similarities between rural and urban operations. Surgery 2006;140:589–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pandit V, Khalil M, Joseph B, et al. Disparities in management of patients with benign colorectal disease: impact of urbanization and specialized care. Am Surg 2016;82:1046–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Quinn L, Read D. Paediatric surgical services in remote northern Australia: an integrated model of care. ANZ J Surg 2017;87:784–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rossi A, Rossi D, Rossi M, et al. Continuity of care in a rural critical access hospital: surgeons as primary care providers. Am J Surg 2011;201:359–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Treacy PJ, Reilly P, Brophy B. Emergency neurosurgery by general surgeons at a remote major hospital. ANZ J Surg 2005;75:852–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Decker MR, Bronson NW, Greenberg CC, et al. The general surgery job market: analysis of current demand for general surgeons and their specialized skills. J Am Coll Surg 2013;217:1133–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Glenn JK, Hicks LL, Daugird AJ, et al. Necessary conditions for supporting a general surgeon in rural areas. J Rural Health 1988;4:85–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ingraham AM, Chaffee SM, Ayturk MD, et al. Gaps in emergency general surgery coverage in the United States. Ann Surg Open 2021; 2: e043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Roos N, Black C, Wade J, et al. How many general surgeons do you need in rural areas? Three approaches to physician resource planning in southern Manitoba. CMAJ 1996;155:395–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Deal SB, Cook MR, Hughes D, et al. Training for a career in rural and nonmetropolitan surgery — a practical needs assessment. J Surg Educ 2018;75:e229–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fader JP, Wolk SW. Training general surgeons to practice in developing world nations and rural areas of the United States — one residency program’s model. J Surg Educ 2009;66:225–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Giles WH, Arnold JD, Layman TS, et al. Education of the rural surgeon: experience from Tennessee. Surg Clin North Am 2009; 89:1313–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gillman LM, Vergis A. General surgery graduates may be ill prepared to enter rural or community surgical practice. Am J Surg 2013;205:752–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Halverson AL, Darosa DA, Borgstrom DC, et al. Evaluation of a blended learning surgical skills course for rural surgeons. Am J Surg 2014;208:136–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kent KC, Foley EF, Golden RN. Rural surgery — a crisis in Wisconsin. WMJ 2015;114:81–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Milligan JL, Nelson HS, Mancini ML, et al. Rural surgery rotation during surgical residency. Am Surg 2009;75:743–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]