Abstract

Background

Breast cancer (BC) has transcended lung cancer as the most common cancer in the world. Due to the disease's aggressiveness, rapid growth, and heterogeneity, it is crucial to investigate different therapeutic approaches for treatment. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Plant-based therapeutics continue to be utilized as safe/non-toxic complementary or alternative treatments for cancer, even in developed countries, regardless of how cutting-edge conventional therapies are. Despite their low bioavailability, curcumin (CUR) and green tea (GT) represent safer therapeutic options. Due to their potent molecular-modulating properties on various cancer-related molecules and signaling pathways, they are considered gold-standard therapeutic agents and have been incorporated into the development of one or more therapeutic strategies of BC treatment.

Methods

We investigated the modulatory role of CUR and GT extracts on significant multi molecular targets in MCF-7 BC cell line to assess their potential as BC multi-targeting agents. We analyzed the phytocompounds in GT leaves using High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) techniques. The mRNA expression levels of Raf-1, Telomerase, Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and Interleukin-8 (IL-8) genes in MCF-7 cells were quantified using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). The cytotoxicity of the extracts was assessed by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay and the released Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), a valuable marker for identifying the programmed necrosis (necroptosis). Additionally, the concentrations of the necroptosis-related proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-8) were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Results

In contrast to the GT, the results showed the anticancer and cytotoxic properties of CUR against MCF-7 cells, with a relatively higher level of released LDH. The CUR extract downregulated the oncogenic Raf-1, suppressed the Telomerase and upregulated the TNF-α and IL-8 genes. Results from the ELISA showed a notable increase in IL-8 and TNF-α cytokines levels after CUR treatment, which culminated after 72 h.

Conclusions

Among both extracts, only CUR effectively modulated the understudy molecular targets, achieving multi-targeting anticancer activity against MCF-7 cells. Moreover, the applied dosage significantly increased levels of the proinflammatory cytokines, which represent a component of the cytokines-targeting-based therapeutic strategy. However, further investigations are recommended to validate this therapeutic approach.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Curcumin, Green tea, Raf-1, Telomerase, TNF-α, IL-8, Necroptosis, TME

1. Background

Breast cancer (BC) in 2020, has transcended lung cancer as the most common cancer in the world, with around 2.3 million new cases diagnosed (11.7 % of all cancer cases). Among women, BC ranks top in terms of occurrence, accounting for around 24.5 % of all cancer diagnoses and 15.5 % of cancer mortalities.1 Surgical resection, radiation and systemic therapy comprising endocrine/hormonal therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or any combination of these methods have been used to manage and treat BC patients.2 However, the major hurdle in treating cancer is eliminating tumor cells while keeping healthy cells without any harm.3 Even though computational chemistry and computer-based molecular modeling approaches are two innovative approaches to drug discovery, none can completely replace the significance of natural products' phytocompounds in therapeutic applications.4 Recent studies have shown that phytocompounds are being used for cancer treatment due to their remarkable antitumor activity, including induction of apoptotic cell death, suppression of cellular proliferation and invasion, enhancement of cancer cell sensitization and augmentation of the immune system response. This emerging approach is particularly appealing due to its minimal side effects, considering the constraints associated with traditional cancer treatment methodologies.5

Diferuloylmethane,1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl]-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione), often known as curcumin (CUR), is a naturally occurring substance made from Curcuma longa Linn (Turmeric), a Zingiberaceae family rhizomatous herbaceous plant, has a wide range of biological effects.6 Through controlling cell survival, proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, angiogenesis and metastasis, preclinical models have shown that CUR plays a crucial role in the course of BC treatment.7, 8, 9, 10 According to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) refined exposure assessment, the acceptable daily intake (ADI) of CUR is reported to be 0–3 mg/kg/day.11 While CUR has demonstrated efficacy in cancer treatment and prevention, supported by decades of human studies and traditional use,12 it is essential to acknowledge that it cannot be deemed entirely safe. Individual case studies have reported unfavorable impacts on immunity, reproduction, blood, heart, liver, and kidneys associated with high doses, which should not be overlooked.13 Moreover, a low dose may not be able to sustain sufficient efficacy against tumor cells14 in addition to its limited bioavailability.15 Consequently, it is crucial to determine appropriate dosages that can produce desired effects while developing CUR as a therapeutic or preventative agent, as inducing cancer in high-risk groups or those with precancerous changes warrants prudent consideration.12, 13

One of the most popular therapeutic drinks in the world is green tea (GT), which is made from Camellia sinensis plant leaves.16 Fresh tea leaf dry mass, which is composed primarily of phenolic compounds, is around 30 % by mass. Catechins make up over 90 % of these polyphenolic substances in GT. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) is the is most prevalent catechin in GT17 and makes up 50 %–80 % of the total quantity of catechins in GT18 in addition to other catechins such as, (-)-epicatechin (EC), (-)-epicatechin-3-gallate (ECG), (-)-epigallocatechin (EGC),19 which exhibit biologic activities including, antioxidation, antiangiogenic and antiproliferation effects, which hold significant potential in the prevention and treatment of several cancers.20 As a result, whether tested clinically or in animal models, the use of GT or its individual components has emerged as a prominent strategy in cancer prevention.21 Notably, EGCG, the most abundant anticarcinogenic catechin in GT,22 inhibited BC at a dose of 87–131 µM.23 However, the main problem reported by the vast majority of the conducted studies on EGCG effects is that the remarkably potent EGCG levels (between 20 and 200 M) are potentially inducing cytotoxic effects against normal cells, leading to undesirable consequences.24 Moreover, EGCG bioavailability was low at different concentrations after 48 h.25

It is well-recognized that BC is a genetically and clinically diverse disease with several sub-types, unique histopathological patterns and molecular features that lead to a wide range of therapeutic responses and clinical outcomes.26, 27 Therefore, the disease necessitates the combination of multiple strategies to be treated efficiently.28

RAF family members (A-Raf, B-Raf and c-Raf (Raf-1)) which considered the upstream activators of the widely known ERK cascade,29 have gained the attention due to the pivotal role of the prominent RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in cancer initiation. Raf-1 has been shown to be upregulated in a variety of human cancers30 and was one of the major oncogenic proteins that stimulated the formation of tumors in non-immortalized cells through human Telomerase reverse transcriptase gene (hTERT) expression induction via the ETS transcription factors ER81 and ERK kinases.31 hTERT, is one of the components, on which Telomerase activity relies on,32 to achieve its overexpression in over 90 % of cancers.33 As a result, the combination of targeting both Telomerase and Raf-1 in a single strategy for cancer treatment achieves a promising therapeutic approach.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is a valuable marker for identifying necrosis.34 Necrosis was initially perceived as a non-regulated form of cell death.35 Nevertheless, it has been discovered that programmed necrosis known as (Necroptosis) can be induced by Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α).36, 37 Extensive research has been conducted to investigate the efficacy and underlying mechanisms of necroptosis, considering its potential to overcome the apoptotic-resistance, and stimulating strong anticancer immune responses, emphasizing its significant potential in cancer therapy.38 It is worthy to mention that pro-inflammatory cytokines may be produced during necroptosis, including interleukin-8 (IL-8),39, 40, 41 that was found to promote neutrophil chemotaxis and degranulation as well as its established stimulatory role in the tumor microenvironment (TME).42

New avenues for employing cytokine-based therapies in cancer treatment have been approached, to boost the effectiveness of other treatments, mitigate immune-related toxicities and specifically target early-stage cancers.43 TNF-α, a potent proinflammatory cytokine, of proven regulatory functions in immunity, inflammation, differentiation, and programmed cell-death,44 has been incorporated in various TNF-α-based biotherapeutics.45 Also, IL-8-based therapy, whether released naturally or induced, can promote the migration of T-cells within the tumor, whereby can effectively inhibit tumor growth and counteract the immunosuppressive effects induced by the tumor, achieving strong antitumor response.46

Potentially life-threatening side effects can occur as a result of anticancer treatments. Patients may develop bone marrow toxicity, cardiac abnormalities, sores in the mouth and other mucous membranes, hair loss, severe acute nausea, and vomiting.47 Therefore, tumor-specific toxicity in BC treatment is considered a critical component to overcome the general hazardous side effects of many anticancer medications, which place restrictions on their utilization.48 As an extension of the well-established therapeutic profile of CUR and GT in the treatment of cancer, in addition to considering the clinical symptoms resulting from the usage of large doses of the extracts, our in vitro study investigated the effects of a low, dosage of CUR and GT leaves extracts against the MCF-7 BC cell line. we sought to verify the effectiveness of the multiple-targets strategy in addressing the widely recognized molecularly divergent nature of BC. We evaluated CUR and GT extracts as potential multi-targeting agents for this purpose, with the future intention of seamlessly integrating them as phytocompound-based therapeutics. To achieve this, we examined the extracts' modulatory role on multiple prominent molecular factors simultaneously.

2. Methods

2.1. Preparation of plants extracts

2.1.1. Preparation of GT leaves extract for HPLC and GC-MS analyses

For use in GC–MS and HPLC analyses, GT leaves extract was purchased from UGC Pharma (Badr city, Eastern area of Cairo, Egypt). 1 kg of GT leaves was prepared by macerating them for 48 h in a mixture of 20:80 water and 100 % pure ethanol. The resulting mixture was then heated in a thermal stainless-steel tank for 6–7 h at a temperature of around 70 °C until it reached a 5 % concentration detectable using a refractometer. After being filtered, the liquid was allowed to cool to room temperature before mixing with preservative substances (2 g of sodium methylparaben and 1 g of sodium propylparaben).

2.1.2. Preparation of plants extracts for molecular assays

In order to prepare the plant extracts, 10 mg smooth powder of each of CUR (from curcuma longa (Turmeric), purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany)) and GT leaves (from local market) carefully dissolved and sterilized with ethanol 70 %. The solutions were then allowed to dry at room temperature. Each of the extracts was dissolved in 1 ml of ethanol 70 % and incubated for 48 h at ambient temperature with regular vortex. The supernatant was transferred to a clean tube at a concentration of 500 µg/µl and kept at 4 °C until used.

2.2. Phytocompounds analyses and molecular assays

2.2.1. Identification of phenols and flavonoids in GT leaves using HPLC

HPLC was used to quantitatively determine the individual phenolic and flavonoid contents of GT leaves extract. As guided by Herrera-Carrera et al.,49 the HPLC being utilized is the (Agilent 1100) with automized injector, which consists of a 1100 quaternary pump, in-line degasser, autosampler, dual wavelength UV/vis detector and acquisition system (Agilent Software 1100, Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The reversed-phase Zorbax octadecylsilane column, model ODS-C18 from Agilent, was used at room temperature. A gradient of two solvent systems; (A) acetic acid–water (2:98 v/v) and (B) acetic acid-acetonitrile–water (2:30:68 v/v) was used at a rate of 1 ml/min to separate phenols and flavonoids through a mobile phase ratio at 0 time of 90 % A and 10 % B, which changed to 0 % A and 100 % B at 30 min. Using the chromatographic retention times of the co-eluted pure standards, the resolved compounds were identified. Phenols and flavonoids were determined at wavelengths of (325 and 280 nm) respectively.

2.2.2. Identification of GT leaves phytocompounds using GC-MS

Using a Trace GC-TSQ Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Austin, TX, USA) equipped with an AS1300 autosampler and a TG-5MS capillary column with a 30 m length, 0.25 mm i.d. and 0.25 m film thickness, the chemical components of the prepared liquid of GT leaves were determined via a technique described by Fayed et al.50 The temperature was scheduled to rise by 5 °C every minute between 50 and 250 °C with a single pause for 2 min and then continue to rise to the final temperature of 300 °C with a final 2 min pause. Source, interface and injector temperatures for the mass spectrometer operating at 70 eV were set to be 200 °C, 260 °C and 270 °C, respectively. In a split mode and a solvent delay of 4 min, samples with a dilution of 1 µl were injected with AS1300 Autosampler. In full scan mode, we obtained electron ionization mass spectra in range of m/z from 50 to 650 at an ionization voltage of 70 eV. 1 ml/min of helium was used as the carrier gas. By comparing the constituents mass spectra and their relative retention times to those in the WILEY 09 and NIST 14 mass spectral databases, the components were identified.50, 51

2.2.3. Cell line propagation

The (MCF-7) Breast cancer cell line was provided from (VACSERA, Giza, Egypt). The grown cells in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI 1640) enriched with 4 mM sodium pyruvate, 4 mM L-glutamine and 5 % heat-treated bovine serum albumin (BSA) were cultured in a 75 ml cell-culture flask and finally incubated at 37 °C under 5 % CO2 humidified conditions.52, 53 An inverted microscope with a Zeiss A-Plan 10x objective lens was used for imaging cultured cells.

2.2.4. MTT assay and determination of cytotoxic concentration 50 % (CC50)

The preincubated MCF-7 cells were cultured in 96-well plates at a density of 10 × 103 cells/well to assess the cytotoxic effect of the extracts and determine their potential CC50. The cells were then treated with different concentrations of each provided extract (0.3–5 mg/ml) and incubated overnight at humidified conditions of 37 °C and 5 % CO2. 10 µl of the MTT labeling reagent (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) from the MTT cell growth assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) was added per well, achieving a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml. The plate was then re-incubated for 4 h at 37 °C and 5 % humidified CO2 incubator. Following this, 100 µl of solubilization solution was added per well and finally incubated overnight at humidified conditions of 5 % humidified CO2 incubator at 37 °C. Based on the quantity of formazan dye that was determined by measuring absorbance at 570 nm, the rate of cell viability and cytotoxic concentration were evaluated.54

2.2.5. Detection of cytotoxicity and necrotic activity by LDH secretion assay

The cytotoxicity and necrotic activity in the fluid media collected from the cultured-treated cells, were evaluated using the LDH assay kit (cat. no. ab65393, Abcam, USA). MCF-7 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 10 × 103 cells/well and were treated with 600 µg/ml of each of CUR and GT. After incubation for 24 h at 37 °C, the media were centrifuged at 600g at 4 °C for 10 min. Subsequently, the supernatant (containing the lysed cells) was transferred to another 96-well plate.55 40 μl of the treated cells received 60 µl of LDH reaction mix (20 µl LDH substrate and 40 µl LDH buffer) according to the manufacturer’s procedures followed by incubation for 1 h at room temperature. The LDH level was quantified using a micro-plate reader at an optical density (OD) of 450 nm.52, 56 Considering the non-treated (NT) cells as the negative control and Triton 100-X as the positive control, the relative LDH production was calculated according to this equation: Relative LDH = (X − Negative control)/(Positive control - Negative control), Where X = sample absorbance value at 450 nm. Finally, the results were expressed as a fold change.

2.2.6. Cell proliferation and morphology assessment

To achieve cell proliferation, cells were seeded in duplicates at a density of 10 × 104 cells per well on a 6-well plate. Followingly, the old media was discarded, and the cells were then given two PBS washes, trypsinized by adding a proper volume of trypsin and then incubated for three minutes at 37 °C. Finally, an appropriate volume of complete RPMI media was added to the trypsinized cells. An inverted microscope was utilized to conduct both the cell morphology assessment and the hemocytometer-assessed survived cells counting.57

2.2.7. Total RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Total cellular RNA was extracted using the RNA isolation kit (TRIzol, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and purified using the RNA purification kit (Invitrogen, PureLink, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The Isolated RNA was dissolved in RNase free water and the concentration was adjusted to 100 ng/μl. 1 μg of total purified RNA was used to synthesize complementary DNA (cDNA) using M-MLV reverse transcriptase from (Promega, USA). According to the manufacturer procedures, total RNA was incubated with reverse transcriptase and oligo (dT) primers at 45 °C for 1 h followed by 5 min incubation at 95 °C. The cDNA was then incubated at -20 °C until used.56

2.2.8. Quantifying gene expression by qRT-PCR

The qRT-PCR was used to quantify gene expression. The (QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit, Qiagen, USA) and the specific primers listed in (Table 1) were utilized for the quantification of the relative gene expression of each of the studied genes, Raf-1, Telomerase, TNF-α and IL-8.58, 59 To normalize the processed data from qRT-PCR analysis, the housekeeping glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression levels were used as an internal control. 0.2 μM of each primer, 2 μl of synthesized cDNA, 0.25 μl RNase inhibitor (25 U/μl), 10 μl SYBR green in addition to nuclease-free water up to the final volume of 25 μl formed the PCR reaction system. PCR was conducted under the following conditions: 94 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles (94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 15 s and 72 °C for 30 s).54, 56

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primer sequences used for mRNA quantification of the studied genes.

| Description | Primer sequences 5′–3′ |

|---|---|

| Telomerase sense | ACTTCCTCTACTCCTCAGGC |

| Telomerase antisense | TTCTCCCGGGCACAGACACC |

| Raf-1 sense | TTTCCTGGATCATGTTCCCCT |

| Raf-1 antisense | ACTTTGGTGCTACAGTGCTCA |

| TNF-α sense | AGGCAGTCAGATCATCTT |

| TNF-α antisense | AGCTGCCCCTCAGCTTGA |

| IL-8 sense | ACTGAGAGTGATTGAGAGTG |

| IL-8 antisense | AACCCTCTGCACCCAGTTTTC |

| GAPDH sense | TGGCATTGTGGAAGGGCTCA |

| GAPDH antisense | TGGATGCAGGGATGATGTTCT |

2.2.9. Proinflammatory cytokines measurement by ELISA

The levels of secreted TNF-α and IL-8 were quantitively measured and analyzed following treatment of MCF-7 cells with 600 μg/ml of each extract over 72 h using human ELISA kits (ab181421 and ab100575 Abcam, USA) respectively. The extracts were incubated with the cell cultures in 96-well plates overnight prior to commencing the time course exposure from 0 to 72 h. Cells were then lysed using 1X cell lysis buffer (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at each time point. 100 µl of the lysed cells were subsequently placed into the ELISA plate reader and incubated for 2 h at room temperature with 100 µl of control solution and 50 µl of 1X biotinylated antibody. After that, each sample well received 100 µl of a 1X streptavidin-HRP solution and then incubated in the dark for 30 min. Each well of the samples received 100 µl of the chromogen TMB substrate solution before being incubated at room temperature away from light for 15 min. The reaction was halted using stop solution (100 μl/well). Absorbance was measured at 450 nm to quantify cytokines levels.60, 61

2.3. Data analysis

The histograms and charts were all created using Microsoft Excel. ΔΔCt analysis was utilized to quantify the mRNA expression levels obtained from qRT-PCR in accordance with the following equations: (1) ΔCt = Ct value for gene - Ct value for GAPDH, (2) (ΔΔCt) = ΔCt value for sample - ΔCt for control), (3) quantification of fold change = (2−ΔΔCt).52, 62 For the statistical analysis, the student's two-tailed t-test was used and statistical significance was determined at P-value ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. HPLC-identified phenols and flavonoids in GT leaves

(Table 2) quantitatively illustrates the identified phenolic and flavonoid phytocompounds of the ethanolic extract of GT leaves. The tabulated data present the concentration (in µg/ml) of each phenolic and flavonoid phytocompound per retention time (RT) (in minutes). Phenolic phytocompounds were identified at a wavelength (λ) of 325 nm, while flavonoid phytocompounds were identified at a wavelength (λ) of 280 nm. Among the phenolic compounds in GT, Caffeic acid, Catechol, and Chlorogenic acid exhibited the highest levels with concentrations of 11.89, 10.14, and 9.27 µg/ml, respectively. Conversely, the least abundant phenolic phytocompounds were Ferulic acid, Isoferulic acid, Gallic acid, and Protocatechuic acid, with concentrations of 1.09, 0.78, 0.56, and 0.09 µg/ml, respectively. Additional phenolic phytocompounds identified included Cinnamic acid (4.22 µg/ml) and Pyrogallol (2.66 µg/ml). In terms of GT flavonoids, the chief GT constituents, Catechin and Epicatechin, exhibited modest concentrations of 7.69 and 0.89 µg/ml, respectively. On the other hand, Rutin and Luteolin displayed the highest abundancy with concentration values of 11.36 and 10.43 µg/ml and in contrast, Myricetin had the lowest concentration of 2.33 µg/ml. Naringin, Kaempferol, and Quercetin were also present in moderate amounts, with concentrations of 4.14, 5.07, and 5.88 µg/ml, respectively.

Table 2.

HPLC analysis report of total phenolic and flavonoid compounds in ethanolic extract of GT leaves.

| Phenolic Compounds | Formula | RT (min) | Concentration (µg/ml) | Flavonoid Compounds | Formula | RT (min) | Concentration (µg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallic Acid | C6H2OH3CO2H | 4.4 | 0.56 | Myricetin | C15H10O8 | 3.0 | 2.33 |

| Pyrogallol | C6H3OH3 | 5.0 | 2.66 | Rutin | C27H30O16 | 4.2 | 11.36 |

| Cinnamic Acid | C9H8O2 | 6.5 | 4.22 | Naringin | C27H32O14 | 5.1 | 4.14 |

| Chlorogenic Acid | C16H18O9 | 7.89 | 9.27 | Quercetin | C15H10O7 | 6.8 | 5.88 |

| Catechol | C6H4OH2 | 9.2 | 10.14 | Kaempferol | C15H10O6 | 8.0 | 5.07 |

| Isoferulic Acid | C10H10O4 | 11.0 | 0.78 | Luteolin | C15H10O6 | 9.0 | 10.43 |

| Caffeic Acid | C9H8O4 | 11.5 | 11.89 | Catechin | C15H14O6 | 12.0 | 7.69 |

| Ferulic Acid | C10H10O4 | 12.2 | 1.09 | Epicatechin | C15H14O6 | 18.0 | 0.98 |

| Protocatechuic Acid | C7H6O4 | 14.2 | 0.09 |

3.2. GC-MS-based phytocompounds profile of GT leaves

The obtained data, derived from the meticulous GC-MS analysis (Table 3), showed a diverse array of bioactive phytocompounds found in ethanolic extracts of GT leaves. Remarkably, Caffeine was presented as the dominant phytocompound, occupying the highest peak area at 63.45 % exhibited at a RT of 24.27, which extended to a second peak at 26.08 RT with a relatively lower peak area of 0.68 %. On the other end of the spectrum, Hexadecanoic acid, 2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester, exhibited the lowest peak area of 0.37 % at an RT of 22.15. However, its significance cannot be overlooked, as it displayed a significant elevation, reaching an area percentage of 4.06 % at an RT of 26.08. Additional extended peak areas were observed, including Benzene, 1-ethyl-3-methyl, which manifested two successive peak areas. The former represented the higher, with a peak area of 5.58 % at an RT of 5.08, while the latter demonstrated the lower, with a peak area of 0.80 % at an RT of 5.43. Besides 9-Octadecenoic acid with a peak area of 0.94 % at RT 22.9, other peak areas not less than 1 % but not exceeding the threshold of a 7 % peak area were also obtained in non-sequential RTs Among these phytocompounds, Ethanol, 2-butoxy- with a peak area of 6.36 % at RT of 4.61, 10-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester with a peak area of 4.06 % at RT of 27.26, Benzene, 1,3,5-trimethyl, with a peak area of 4.70 % at RT of 5.72 and 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)- with a peak area of 4.75 % at RT of 28.71. Furthermore, several low peak areas were observed for each of Cyclopropanepentanoic acid, 2-undecyl-, methyl ester (1.17 %), trans, 10,13-Octadecadiynoic acid, methyl ester (1.24 %), and 10-Heptadecen-8-ynoic acid, methyl ester, (E)- (1.84 %) at RT of 27.65, 6.33 and 6.99, respectively.

Table 3.

Identified compounds obtained from GC-MS analysis of the ethanolic extract of GT leaves.

| Retention time (RT) (min) | Compound Name | Area % | Molecular Formula | Molecular Weight | CAS# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.60 | Ethanol, 2-butoxy- | 6.36 | C6H14O2 | 118 | 111-76-2 |

| 5.08 | Benzene, 1-ethyl-3-methyl | 5.58 | C9H12 | 120 | 620-14-4 |

| 5.43 | Benzene, 1-ethyl-3-methyl | 0.80 | C9H12 | 120 | 620-14-4 |

| 5.72 | Benzene, 1,3,5-trimethyl | 4.70 | C9H12 | 120 | 108-67-8 |

| 6.33 | 10,13-Octadecadiynoic acid, methyl ester | 1.24 | C19H30O2 | 290 | 18202-24-9 |

| 6.99 | 10-Heptadecen-8-ynoic acid, methyl ester, (E)- | 1.84 | C18H30O2 | 278 | 16714-85-5 |

| 22.15 | Hexadecanoic acid, 2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester | 0.37 | C19H38O4 | 330 | 542-44-9 |

| 22.91 | 9-Octadecenoic acid | 0.94 | C18H34O2 | 282 | 112-80-1 |

| 24.27 | Caffeine | 63.45 | C8H10N4O2 | 194 | 58-08-2 |

| 24.59 | Caffeine | 0.68 | C8H10N4O2 | 194 | 58-08-2 |

| 26.08 | Hexadecanoic acid, 2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester | 4.06 | C19H38O4 | 330 | 542-44-9 |

| 27.26 | 10-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester | 4.06 | C19H36O2 | 296 | 13481-95-3 |

| 27.65 | Cyclopropanepentanoic acid,2-undecyl-, methyl ester, trans | 1.17 | C20H38O2 | 310 | 42199-20-2 |

| 28.71 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)- | 4.75 | C18H32O2 | 280 | 60-33-3 |

3.3. CUR and GT influence on MCF-7 cell viability rate, number and morphology

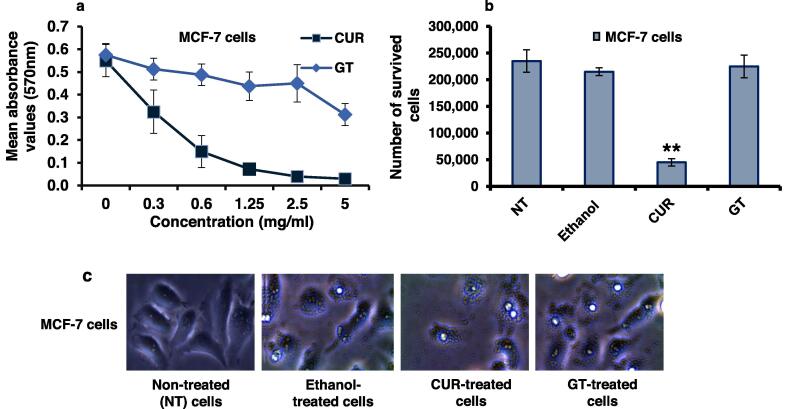

MTT assay estimated MCF-7 cells viability rate after being subjected to the treatment of extracts. The experiments were conducted in quadruplicate for each concentration of the ethanolic extracts (0.3, 0.6, 1.25, 2.5, 5 mg/ml). The results were statistically analyzed using the t-test hypothesis, with each data point representing the mean value of 4 independent results with significance set at a P value of ≤0.05 as shown in (Table 4). The results demonstrated that ethanolic CUR extract exerted a significant dose-dependent cytotoxic effect on the viability rate of MCF-7 cells, as shown in Fig. 1a. Conversely, the ethanolic extract of GT exhibited no detectable cytotoxic activity against the cells. The CC50 (the concentration of the extract required for a 50 % reduction in cell viability) of the investigated ethanolic extracts of CUR against MCF-7 cells was determined to be 1.25 mg/ml. Two repetitive experiments were performed and the mean results obtained after treating cells with the CC50 concentrations of both extracts were compared to those of the negative control (NT cells) and the positive control (the ethanol-treated cells), revealing that the number of MCF-7 cells dropped by 5-fold after CUR treatment, while the ethanolic extract of GT leaves failed to achieve any noticeable regression in the treated cells number (Table 5 and Fig. 1b). The in vitro proliferation assessment of ethanolic extracts of CUR and GT on MCF-7 cells was conducted by monitoring the altered cellular morphology and population of cells within a given field after being subjected to each of the ethanolic extracts. In comparison to the negative control represented by the NT MCF-7 cells and the positive control represented by ethanol-treated cells, the images obtained from an inverted microscope (Fig. 1c) showed changes in morphology and a decrease in the population of MCF-7 cells in the case of ethanolic CUR treatment. On the other hand, cells treated with ethanolic GT showed negligible changes in both morphology and population.

Table 4.

Statistical analysis of MCF-7 cells viability upon treatment by plants extracts indicated by absorbance values.

| Treatment | Concentration (mg/mL) | Mean | Standard deviation (S.D.) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CUR | 0.0 | 0.55 | 0.07 | – |

| 0.3 | 0.33 | 0.10 | 0.00917222** | |

| 0.6 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.000203** | |

| 1.25 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.0001** | |

| 2.5 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.0000 | |

| 5 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.0000 | |

| GT | 0.0 | 0.58 | 0.05 | – |

| 0.3 | 0.51 | 0.05 | 0.1210 | |

| 0.6 | 0.49 | 0.05 | 0.0448* | |

| 1.25 | 0.44 | 0.06 | 0.0141** | |

| 2.5 | 0.45 | 0.08 | 0.0401* | |

| 5 | 0.31 | 0.05 | 0.0003** |

Fig. 1.

Cytotoxic effects of CUR and GT against MCF-7 cells (a) The cell viability rate of MCF-7 cells treated with different concentrations of ethanolic CUR or GT extracts indicating the CC50 using the MTT assay, n = 4. (b) The number of survived cells treated with either CUR or GT extract. Error bars indicate the S.D. of two independent experiments. The Student’s two-tailed t-test was used for the significance analysis of the represented values. (**) indicates the P ≤ 0.01 and (*) indicates the P ≤ 0.05. (c) Inverted microscopy images of cell morphology and changes in the population of cells upon treatment with either ethanolic CUR or GT extract for 24 h in comparison with the positive control represented by ethanol-treated cells and non-treated (NT) cells.

Table 5.

Number of survived MCF-7 cells after treatment.

| Treatment | Non-treated (NT) cells | Ethanol-treated cells | CUR | GT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 235000 ± 21213 | 215000 ± 7071 | 45000 ± 7071 | 225000 ± 21213 |

| P-values | – | 0.333 | 0.007** | 0.684 |

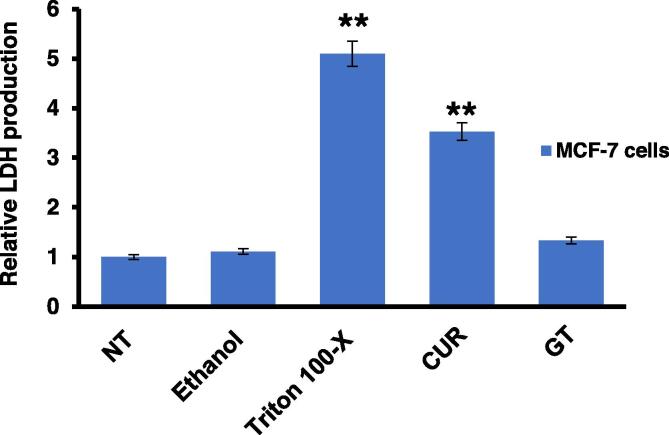

3.4. Cellular damage in MCF-7 cells treated with CUR and GT, as indicated by the discharge of LDH

LDH is discharged from the cytoplasm into the extracellular environment in response to cellular damage caused by internal cellular processes or as a result of external assaults. It is a suitable correlate for the presence of damage and toxicity in tissues and cells due to its stability in cell culture media. Furthermore, it is considered a valuable marker for necrosis.34, 63 Intriguingly, as shown in (Table 6 and Fig. 2), the relative production of LDH exhibited a substantial dose-dependent increase in ethanolic CUR-treated cells compared to ethanolic GT extract-treated cells. This increase was notably higher when compared to the negative control, represented by the NT cells.

Table 6.

Relative LDH production in treated MCF-7 cells.

| Treatment | Non-treated (NT) cells | Ethanol-treated cells | Triton 100-X | CUR | GT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.15 | 0.23 ± 0.10 | 0.09 ± 0.00 |

| Relative produced LDH | 1.00 | 1.11 | 5.10 | 3.53 | 1.33 |

| P-values | – | 0.6014 | 0.0134** | 0.0158** | 0.2226 |

Fig. 2.

Cellular damage indicated by LDH production Relative LDH production from MCF-7 cells treated with either CUR or GT extract, compared to the positive control Triton 100-X treated cells and the negative control, the non-treated (NT) cells. The S.D. of four different replicates was indicated by error bars. Student's two-tailed t-test was used to determine the significance of differentiated values. (**) indicates the P ≤ 0.01.

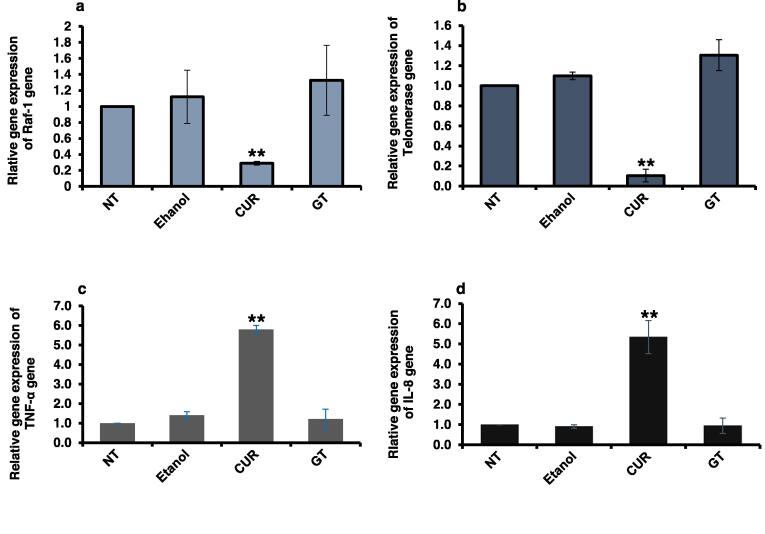

3.5. Modulatory role of CUR and GT on the expressed Raf, Telomerase, TNF-α and IL-8 genes in MCF-7 cells

The mRNA levels of Raf-1, Telomerase, TNF-α and IL-8 genes in MCF-7 cells were quantified using qRT-PCR to assess the bioactivity of CUR and GT extracts on cellular signal transduction (Table 7). In a dose and time-dependent manner, CUR demonstrated a significant impact on the expression of these genes compared to the positive control, represented by ethanol-treated cells, and the negative control, represented by NT cells. Notably, CUR drastically decreased the level of Raf-1 (Fig. 3a) and almost repressed the level of Telomerase (Fig. 3b). Moreover, it significantly elevated the levels of TNF-α and IL-8 (Fig. 3c and d). On the other hand, GT exhibited a modest upregulation of both Raf-1 and Telomerase genes, while exerting negligible to no influence on TNF-α and IL-8 levels, respectively (Fig. 3a–d).

Table 7.

Quantification of relative gene expression of Raf-1, Telomerase, TNF-α and IL-8 in treated MCF-7 cells.

| Gene | Treatment | Fold changes | P-values | Gene | Treatment | Fold changes | P-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raf-1 | NT | 1.000 ± 0.000 | – | TNF-α | NT | 1.000 ± 0.000 | – |

| Ethanol | 1.120 ± 0.335 | 0.66372 | Ethanol | 1.406 ± 0.183 | 0.08871 | ||

| CUR | 0.290 ± 0.024 | 0.00056** | CUR | 5.800 ± 0.202 | 0.00088** | ||

| GT | 1.327 ± 0.437 | 0.40150 | GT | 1.219 ± 0.492 | 0.59325 | ||

| Telomerase | NT | 1.00 ± 0.00 | – | IL-8 | NT | 1 ± 0.00 | – |

| Ethanol | 1.099 ± 0.038 | 0.06738 | Ethanol | 0.905 ± 0.091 | 0.27789 | ||

| CUR | 0.104 ± 0.063 | 0.00243** | CUR | 5.337 ± 0.821 | 0.01744** | ||

| GT | 1.305 ± 0.154 | 0.10689 | GT | 0.940 ± 0.382 | 0.84420 |

Fig. 3.

Quantification of Raf-1, Telomerase, TNF-α and IL-8 expression in treated MCF-7 cells with plants extracts (a) Fold change of steady-state mRNA of Raf-1 gene in MCF-7 cells in comparison with the negative control non-treated (NT) cells. (b) Fold change of steady-state mRNA of Telomerase gene in MCF-7 cells in comparison with the negative control non-treated (NT) cells. (c) Fold change of steady-state mRNA of TNF-α gene in MCF-7 cells in comparison with the negative control non-treated (NT) cells. (d) Fold change of steady-state mRNA of IL-8 gene in MCF-7 cells in comparison with the negative control non-treated (NT) cells. Levels of GAPDH mRNA were used as an internal control, while ethanol-treated cells considered the positive control. The S.D. of two independent experiments was indicated by error bars. Student's two-tailed t-test was used, where (**) indicates the P ≤ 0.01.

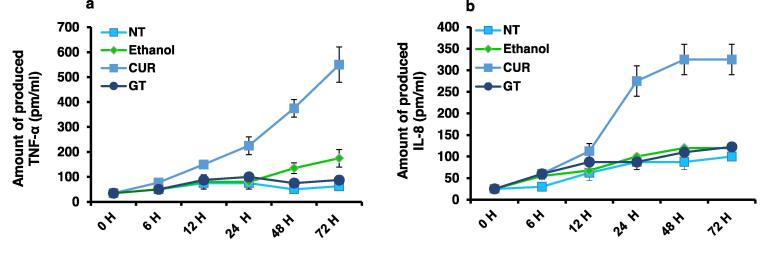

3.6. CUR and GT stimulatory effects on IL-8 and TNF-α in MCF-7 cells

TNF-α and IL-8 were measured in a time-course assay using ELISA to examine the relationship between the treatment by the extracts and the proinflammatory markers released by the treated cells. It is remarkable to note that CUR treatment resulted in a time-dependent increase in TNF-α and IL-8 production, reaching levels of 550 and 325 pm/ml, respectively, compared to NT cells as the negative control and ethanol-treated cells as the positive control (Fig. 4a and b). Conversely, cells treated with GT produced a significantly negligible amount of TNF-α and IL-8, measuring 87 and 122.5 pm/ml, respectively (Fig. 4a and b). These findings collectively support the ability of CUR to regulate the release of proinflammatory markers from treated cells.

Fig. 4.

Levels of Produced proinflammatory markers TNF-α and IL-8 in MCF-7 cells treated with plants extracts (a) Concentration of the produced cytokine TNF-α (pm/ml) in the fluid media of MCF-7 cells that received 1.25 mg/ml of each plant extract at the specified time points compared to the positive control, represented by ethanol-treated cells, and the negative control, represented by non-treated (NT) cells. (b) Concentration of the produced chemokine IL-8 (pm/ml) from MCF-7 cells treated with 1.25 mg/ml of each plant extract at the specified time points compared to the positive control, represented by ethanol-treated cells, and the negative control, represented by non-treated (NT) cells. The S.D. of two replicates was revealed by error bars.

4. Discussion

In view of the well-recognized molecular divergence of BC,64 a comprehensive therapeutic plan should incorporate multiple treatment modalities. Therefore, it was relevant to determine potential molecular targets that could be modulated in favor of effective BC treatment in addition to exploring the potential molecular targets that represent a component in the targeted-based therapy to be employed in complement to other therapies. Considering the well-established anti-cancer profiles of CUR and GT,65, 66 we evaluated ethanolic extracts of CUR, considered the main bioactive compound in turmeric,67 and the whole crude of GT leaves to maximize the previously reported anticancer effect of some of its contained compounds.68, 69, 70 To ensure efficacy and eliminate adverse effects, it is crucial to determine an appropriate dosage that overcomes their low bioavailability. Therefore, low doses of both extracts were examined.

CUR exhibits a wide range of chemotherapeutic and chemopreventive influences.71, 72 Its anticancer potential against BC was demonstrated through the inhibition of cell proliferation and promotion of apoptosis in various human BC cell lines, including MCF-7, T47D, MDA-MB-468, and MDA-MB-231.73 In our assessment of the effect of CUR on MCF-7 cell viability using the MTT assay, specifically at a concentration of 1.25 mg/ml (CC50), we observed a significant reduction in cell viability over a 0–24-hour treatment course. Our current findings indicate that CUR effectively inhibits the growth of MCF-7 cells in a dose and time-dependent manner. Furthermore, treatment with CUR extract resulted in an elevated level of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) production. The simultaneous effects on cell viability (as demonstrated by the MTT assay) and cytotoxicity (as determined by LDH release into the medium) align with a previous study conducted by Wright et al., regarding cytotoxicity. However, our results contradict their findings on antiproliferation,74 the effect of which was achieved by our dosage, as evidenced by the changes in viable cell number and cell morphology.

Genomic alterations in BC are rarely a factor contributing to its development. Nevertheless, it can be triggered by various mechanisms, including membrane receptor activation, epigenetic events, or intracellular signaling network re-adjustments. Among the 11 % of modulations in RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway-related genes of primary breast tumors, Changes in Raf-1 expression are linked to considerably worst survival for BC.75 Moreover, Raf-1 activation for this pathway has been responsible for a more aggressive phenotype marked by enhanced cell proliferation and migration, chemoendocrine resistance and eventually the formation of distant metastases conferred by this pathway activation.76 Given these findings, Raf-1 has been known as a promising target to regulate the ERK/MAPK pathway,77 subsequently a potential therapeutic strategy against cancer.78 Wu et al. demonstrated CUR ability to suppress K562 cell growth via downregulation of the p210BCR/ABL/RAS/RAF/MEK-1/ERK/Elk-1 pathway as one of the signal transduction pathways involved in the mechanism of action.79 Raf-1, being one of three known RAF isoforms and the first to be identified,80 was effectively targeted by the CUR extract, fulfilling effective interference with the ERK cascade pathway, and resulted in antiproliferation of MCF-7 cells.

Telomerase is a ribonucleoprotein complex that specifically handles telomere shortening. hTERT and Telomerase RNA, the two major components of human Telomerase, act as templates for telomere lengthening, a vital process since maintaining telomere length is crucial for the continuing division of cells.81 The fact that over 90 % of malignancies overexpress Telomerase, which is necessary for the beginning and maintenance of carcinogenesis,33 guided numerous research studies with the aim of cancer treatment. Also, it led to the evaluation of Telomerase inhibitors in combination with traditional cancer treatments and in maintenance clinical trials to reduce recurrence following surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation.82 Our results reinforced a previous study that demonstrated that reduction of the hTERT gene expression in BC cells by CUR suppressed human Telomerase activity and that this reduction was not due to the c-Myc pathway.83 And even though the dose used was low, CUR effectively repressed the Telomerase levels, further contributing to its potential mode of action in eliminating MCF-7 cells. Moreover, by building upon the previously reported interaction between Raf-1 and hTERT,31 one of the key components of telomerase,33 the simultaneous targeting accomplished through the use of CUR emerges as a promising therapeutic approach for the effective treatment of BC.

In a previous study, it was observed that a low dose of ethanolic CUR extract did not exert any influence on TNF-α and IL-8. Conversely, a high content of DMSO-soluble CUR was found to reduce IL-8 expression while upregulating TNF-α levels. Additionally, the study indicated that CUR did not show involvement in the NF-κB pathway but downregulated Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) expression. It also inhibited JNK, a member of the MAPK family, while activating ERK and p38.84 However, in our investigation, the low dosage of ethanolic CUR extract resulted in a significant upregulation of both IL-8 and TNF-α, along with a downregulation of Raf-1. As a result, we proposed that the production of IL-8 potentially has eventuated through a MAPK pathway other than ERK. It is widely accepted that the timing of sample collection plays a crucial role since CUR demonstrates a temporal transition from a pro-to antioxidant.85 This evidence promoted our hypothesis that CUR induced the generation of free radicals. In this context, Kang et al. reported that CUR-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) are of a biphasic function, depending on the incubation period.86 Thus, shown CUR to contribute to a complex signaling network, promoting survival in the early incubatory period and necrotic death in the latter, subsequently inhibiting apoptotic cell death. Through the induction of ROS, CUR could enhance DU-145 prostate cancer cells proliferation via ERK or p38/JNK with the assist of phosphorylated Akt. In later periods, considerably produced amounts of ROS, induced cell death in the case of caspase degradation. Consequently, besides autophagic signaling, necrosis was dominant, with insignificant apoptotic cell death. The toxicity caused by CUR peaked and proliferation signs, such as phosphorylated ERK and phosphorylated Akt, were almost completely declined.86 The findings of the current study are consistent with the observations made by Kang et al. Although we did not measure the presence of elevated ROS, we postulated based on the obtained results and supported by the elevation of the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α, along with the increased IL-8 levels and high lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) production after treatment, that a different type of cell death, accompanied by the establishment of a pro-inflammatory TME, occurred, distinct from apoptosis.

Necrosis, also referred to as necroptosis, is a distinct form of cell death that may occur in the TME under specific circumstances, exerting an influence on the immune system’s response. Unlike tolerogenic types of cell death such as apoptosis and senescence, necrosis elicits inflammatory reactions.87 Followingly, multiple molecules known as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) are released into the TME as a result of membrane damage. When encountered by immune cells, these DAMPs stimulate the production of inflammatory cytokines.88 TNF-α and IFN-γ, among other inflammatory cytokines, enhance the immune system activity and development against cancer cells.14 It is worth noting that when applied to prostate cancer cells, CUR has been shown to increase the expression of a variety of proteins, including various DAMPs that comprise the High mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1).89 In recent years, the immunogenicity of necroptotic tumor cells and their potential role in antitumor immune responses have garnered substantial attention as an alternative cancer elimination strategy.90 Although our study did not measure the DAMPs produced in the medium, Leijte et al. reported in their study that the Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (CRS-HIPEC) procedure induced remarkable cellular damage, unscheduled cell death and/or cellular stress, as evidenced by LDH and DAMP release.91 They observed LDH and DAMPs levels significantly correlated with TNF-α, and various interleukins, including IL-8. However, and contrary to our findings, which showed elevated levels of LDH production and upregulation of the proinflammatory markers TNF-α and IL-8 after treatment with CUR extract, the previous study concluded that the transient pro-inflammatory markers that followed the chemotherapy led to immunosuppression. The major goal of immunotherapy and adjuvant treatment is to modify the responses of the TME in order to promote cancer cell death, thus enabling normal tissues to respond more favorably to treatment with fewer adverse effects.92, 93 Interestingly, as an immunomodulator, it has been demonstrated that CUR influences a range of cell interactions that either promote or antagonize tumor growth.94 Additionally, the administration of CUR has been found to induce the infiltration of various T cell subpopulations, particularly CD8+ T cells and CD4+ cytotoxic lymphocytes,95 which have previously been associated with tumor regression.96 Furthermore, CUR can alter immune system responses toward type 1 T helper cells (Th1) within the TME. The increased production of TNF-α and IFN-γ promotes the growth of antitumor immune cells, including natural killer (NK) cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells.14 These cells possess the capability to release lytic agents such as perforin, granzyme B, and reactive oxygen species (ROS).97, 98 The elevation of TNF-α following our CUR treatment supports CUR previously demonstrated immunomodulatory role. Collectively, these studies indicate CUR modifies the TME to favor anti-tumor immunity, partly through cytokine induction. Our findings of increased TNF-α are consistent with CUR promoting pro-inflammatory signals driving anti-cancer immunity. In summary, CUR shows promise as an immunotherapy adjuvant.

TNF-α, a well-documented pro-inflammatory cytokine, is known to be up-regulated in BC.99 By binding to TNF-receptor 1 (TNFR1) and TNF-receptor 2 (TNFR2) on the cell membrane, TNF-α governs a plethora of intracellular signaling events.100 The presence of prominent levels of TNF-α in tumors can enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy. However, despite its potential to induce cell death pathways, TNF-α levels alone are insufficient to cause tumor regression in both mice and humans.101 It has been postulated that external delivery of TNF-α may occupy TNFR1 produced by both healthy endothelial cells and tumor cells without adversely affecting the former, as tumor-resident endothelial cells upregulate TNFR1 in response to cytokines.102, 103 Interestingly, studies in rodents have demonstrated a synergistic antitumor effect of TNF-α when combined with chemotherapeutic treatments, as it leads to enhanced levels of the latter at the tumor site.104, 105, 106 TNF-α has also been reported to contribute to these high response rates via two distinct processes: boosting endothelium permeability, allowing easier chemotherapy entry and vascular leakage from directly killed tumor endothelium.107 In addition to its role as an innate mediator of proinflammatory cytokine stimulation, TNF-α possesses the ability to activate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and various inflammatory genes, including IL-8, as well as several inflammatory genes, including IL-8.108, 109 Notably, the induction of IL-8 production by TNF-α in synovial fibroblasts, which is implicated in the progression of rheumatoid arthritis, is influenced by the activation of either the ERK2 or JNK1 pathways in a time and dose-dependent manner.110 Another study reported that the JNK gene was significantly upregulated after CUR treatment of human colon cancer HCT116 cells, but not the ERK or p38 MAPK genes.111 Our study, in line with previous research, suggests that the application of CUR extract to MCF-7 cells may interfere with the ERK pathway via suppressing Raf-1 expression. Furthermore, the observed elevation of TNF-α and IL-8 levels implies the activation of an alternative signaling pathway responsible for cytokine secretion, distinct from ERK. There is growing evidence that within inflammatory microenvironments, proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α rely on their corresponding receptors, such as TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1), to initiate the formation of the necrosome, involving receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) and receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 3 (RIPK3), resulting in phosphorylation and oligomerization of mixed lineage kinase domain-like pseudokinase (MLKL).112 The TNF-α/TNFR1-driven signaling pathway, representing one of the most well-investigated necroptosis models, is widely present in several tumor types and other pathophysiologic disorders. Notably, RIP1 must first be phosphorylated during TNF-α/TNFR1-induced necrosis for RIP3 to activate through its kinase activity113, 114, 115, 116. Subsequently, JNK/ IL-8 have been unveiled as the downstream effectors of MLKL during necroptosis.41 Building upon prior research linking necroptosis induction to IL-8 elevation,39, 40, 41 coupled with our observations, we hypothesized that the TNF-α/TNFR1/RIP1/RIP3/MLKL/JNK/IL-8 pathway underlies CUR ability to trigger IL-8 levels in MCF-7 cells. This hypothesis holds particular relevance for therapies targeting IL-8. However, further investigations are warranted to directly measure the presence of the components within the postulated pathway and establish a definitive correlation. Notably, IL-8 wields substantial influence over TME.42 Depending on the cell type, tumor inhibition117, 118 and promotion,119, 120 have both been shown in vivo when IL-8 is transfected in cancer cells.121 These observations underscore the dual nature of IL-8, accentuating its capacity to function as both an immunoenhancer and a cancer proinhibitor depending on the cellular context.

According to prior research, the upregulated expression of the c-Raf (Raf-1) oncogene in the lung tissue of the mice which received the tobacco-specific nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamine)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone NNK treatment for 4 or 8 weeks was suppressed by 2 % tea consumption, resulting in inhibitory rates of 20 %.122 Similarly, Afaq et al. also reported that EGCG can modulate other members of the MAPK family.123 However, in contrast to these findings, our evaluated dosage of GT had no impact on the Raf-1 gene. In contrast to the data obtained from investigating the role of the GT primary pigment, Theabrownin124 and EGCG,68 which showed effects on the expression of IL-8 and Telomerase, respectively, our extract had minimal to no effect on these molecular targets under investigation. Furthermore, Unlike the data reported by Sueoka et al. in TNF-α transgenic mice,125 our dose of GT extract failed to downregulate TNF-α levels. Supporting this lack of effect, HPLC results revealed low concentrations of Catechin and Epicatechin (7.69 and 0.89 μg/ml, respectively), the primary polyphenolic constituents of GT.126 Of note, the major catechin in GT, EGCG, which contributes significantly to its anticancer efficacy,127 was found to be susceptible to degradation, influenced by the duration of time between preparation and measurement and was found to be molecularly-unstable due to dimer formation at lower concentrations.128 These prior findings may elucidate the failure of the under-study dose of GT in regulating Raf-1, Telomerase, TNF-α, and IL-8 or exhibiting potential anticancer effects against MCF-7 cells.

5. Conclusions

Even when applied at a low dose, the multi-targeting strategy employed by CUR manifested its potent cytotoxicity and antiproliferative effects against MCF-7 BC cells. In contrast to the applied low dose of GT, which exhibited a negligible cytotoxic effect against MCF-7 cells, the anticancer strategy of CUR against MCF-7 cells yielded substantial results. CUR not only induced cytotoxicity, leading to the elimination of cancer cells by interfering with the ERK pathway via Raf-1 suppression, but also maintained the antiproliferative activity against cancer cells through Telomerase repression. Our findings substantiate CUR as a confirmed anticancer therapeutic agent for the treatment of the well-recognized molecularly divergent BC, fulfilling the multiple-targets strategy necessity for effective treatment. Furthermore, the CUR-induced elevated cytokines TNF-α and IL-8 suggest a potential strategy to incorporate CUR, which represents a component of phytocompound-based therapeutics, into a cytokine-based therapeutic plan. This combination holds great promise in paving the way for tumor-immunity suppressive cytokine-based therapies that target TNF-α and IL-8, thereby enhancing immunosurveillance and preparing the TME for additional therapies, which ultimately leads to effective cancer cell elimination. However, further in vitro, in vivo and relevant clinical trials are required to elucidate the efficacy of these therapeutic strategies in the treatment of BC and provide robust experimental confirmation.

Data availability

The dataset supporting the findings of the study is provided within the published paper. All additional information will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

This study was self-funded and was conducted as a part of M.Sc. degree fulfilment.

CRediT authorship contribution Statement

Radwa M. Fawzy: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Amal A. Abdel-Aziz: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Khalid Bassiouny: Conceptualization, Supervision. Aysam M. Fayed: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harbeck N., Penault-Llorca F., Cortes J., et al. Breast cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:66. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mousa S.A., Bharali D.J. Nanotechnology-based detection and targeted therapy in cancer: nano-bio paradigms and applications. Cancers. 2011;3:2888–2903. doi: 10.3390/cancers3032888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veeresham C. Natural products derived from plants as a source of drugs. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2012;3:200–201. doi: 10.4103/2231-4040.104709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rizeq B., Gupta I., Ilesanmi J., AlSafran M., Rahman M.M., Ouhtit A. The power of phytochemicals combination in cancer chemoprevention. J Cancer. 2020;11:4521–4533. doi: 10.7150/jca.34374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deokate U., Upadhye M. In: Ginger cultivation and use. Kaushik P., Ahmad R.S., editors. IntechOpen; London: 2023. Antioxidant potential of phytoconstituents with special emphasis on curcumin. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y., Yu J., Cui R., Lin J., Ding X. Curcumin in treating breast cancer: a review. J Lab Autom. 2016;21:723–731. doi: 10.1177/2211068216655524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu D., Chen Z. The effect of curcumin on breast cancer cells. J Breast Cancer. 2013;16:133–137. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2013.16.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song X., Zhang M., Dai E., Luo Y. Molecular targets of curcumin in breast cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2018;19:23–29. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.9665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun X.D., Liu X.E., Huang D.S. Curcumin induces apoptosis of triple-negative breast cancer cells by inhibition of EGFR expression. Mol Med Rep. 2012;6:1267–1270. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Food Safety Authority Refined exposure assessment for curcumin (E 100) EFSA J. 2014;12:3876. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2014.3876. 43 pp. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shehzad A., Qureshi M., Anwar M.N., Lee Y.S. Multifunctional curcumin mediate multitherapeutic effects. J Food Sci. 2017;82:2006–2015. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.13793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stringer JL, Snyder SI. Anticancer drug. Encyclopedia Britannica. 2018. https://www.britannica.com/science/anticancer-drug [Accessed 18 Aug 2023].

- 14.Fu X., He Y., Li M., Huang Z., Najafi M. Targeting of the tumor microenvironment by curcumin. Biofactors. 2021;47:914–932. doi: 10.1002/biof.1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopresti A.L. The problem of curcumin and its bioavailability: could its gastrointestinal influence contribute to its overall health-enhancing effects? Adv Nutr. 2018;9:41–50. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmx011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao T., Li C., Wang S., Song X. Green tea (Camellia sinensis): a review of its phytochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology. Molecules. 2022;27:3909. doi: 10.3390/molecules27123909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tachibana H. Molecular basis for cancer chemoprevention by green tea polyphenol EGCG. Forum Nutr. 2009;61:156–169. doi: 10.1159/000212748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koch W., Kukula-Koch W., Komsta Ł., Marzec Z., Szwerc W., Głowniak K. Green tea quality evaluation based on its catechins and metals composition in combination with chemometric analysis. Molecules. 2018;23:1689. doi: 10.3390/molecules23071689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reygaert W.C. Green tea catechins: their use in treating and preventing infectious diseases. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:9105261. doi: 10.1155/2018/9105261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper R., Morré D.J., Morré D.M. Medicinal benefits of green tea: Part II. Review of anticancer properties. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:639–652. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rahmani A.H., Al Shabrmi F.M., Allemailem K.S., Aly S.M., Khan M.A. Implications of green tea and its constituents in the prevention of cancer via the modulation of cell signalling pathway. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/925640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cabrera C., Artacho R., Giménez R. Beneficial effects of green tea—a review. J Am Coll Nutr. 2006;25:79–99. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2006.10719518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belguise K., Guo S., Sonenshein G.E. Activation of FOXO3a by the green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate induces estrogen receptor α expression reversing invasive phenotype of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5763–5770. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lambert J.D., Yang C.S. Cancer chemopreventive activity and bioavailability of tea and tea polyphenols. Mutat Res. 2003;523–524:201–208. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00336-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thangapazham R.L., Singh A.K., Sharma A., Warren J., Gaddipati J.P., Maheshwari R.K. Green tea polyphenols and its constituent epigallocatechin gallate inhibits proliferation of human breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2007;245:232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yersal O., Barutca S. Biological subtypes of breast cancer: Prognostic and therapeutic implications. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5:412–424. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i3.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baliu-Piqué M., Pandiella A., Ocana A. Breast cancer heterogeneity and response to novel therapeutics. Cancers. 2020;12:3271. doi: 10.3390/cancers12113271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yeo S.K., Guan J.L. Breast cancer: multiple subtypes within a tumor? Trends Cancer. 2017;3:753–760. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matallanas D., Birtwistle M., Romano D., et al. Raf family kinases: old dogs have learned new tricks. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:232–260. doi: 10.1177/1947601911407323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rapp U.R., Fensterle J., Albert S., Götz R. Raf kinases in lung tumor development. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2003;43:183–195. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(03)00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goueli B.S., Janknecht R. Upregulation of the catalytic telomerase subunit by the transcription factor ER81 and oncogenic HER2/Neu, Ras, or Raf. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:25–35. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.25-35.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ray S.K., Mukherjee S. In: Hypoxia in cancer: significance and impact on cancer therapy. Mukherjee S., Kanwar J.R., editors. Springer; Singapore: 2023. Hypoxic regulation of telomerase gene expression in cancer; pp. 251–273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solomon P., Dong Y., Dogra S., Gupta R. Interleukin 8 is a biomarker of telomerase inhibition in cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:730. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4633-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan F.K., Moriwaki K., De Rosa M.J. Detection of necrosis by release of lactate dehydrogenase activity. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;979:65–70. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-290-2_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan F.K., Shisler J., Bixby J.G., et al. A role for tumor necrosis factor receptor-2 and receptor-interacting protein in programmed necrosis and antiviral responses. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:51613–51621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305633200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chipuk J.E., Green D.R. Do inducers of apoptosis trigger caspase-independent cell death? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:268–275. doi: 10.1038/nrm1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Degterev A., Huang Z., Boyce M., et al. Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:112–119. doi: 10.1038/nchembio711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zang X., Song J., Li Y., Han Y. Targeting necroptosis as an alternative strategy in tumor treatment: From drugs to nanoparticles. J Control Release. 2022;349:213–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Negroni A., Colantoni E., Pierdomenico M., et al. RIP3 AND pMLKL promote necroptosis-induced inflammation and alter membrane permeability in intestinal epithelial cells. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:1201–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu K., Liang W., Ma Z., et al. Necroptosis promotes cell-autonomous activation of proinflammatory cytokine gene expression. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:500. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0524-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y., Zhao M., He S., et al. Necroptosis regulates tumor repopulation after radiotherapy via RIP1/RIP3/MLKL/JNK/IL8 pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:461. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1423-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waugh D.J., Wilson C. The interleukin-8 pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6735–6741. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Propper D.J., Balkwill F.R. Harnessing cytokines and chemokines for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:237–253. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00588-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baud V., Karin M. Signal transduction by tumor necrosis factor and its relatives. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:372–377. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cai W., Kerner Z.J., Hong H., Sun J. Targeted cancer therapy with tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Biochem Insights. 2008;2008:15–21. doi: 10.4137/BCI.S901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jin L., Tao H., Karachi A., et al. CXCR1- or CXCR2-modified CAR T cells co-opt IL-8 for maximal antitumor efficacy in solid tumors. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4016. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11869-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu S., Liu J., He L., et al. A comprehensive review on the benefits and problems of curcumin with respect to human health. Molecules. 2022;27:4400. doi: 10.3390/molecules27144400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chari R.V.J. Targeted cancer therapy: conferring specificity to cytotoxic drugs. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:98–107. doi: 10.1021/ar700108g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herrera-Carrera E., Moreno-Jiménez M.R., Rocha-Guzmán N.E., et al. Phenolic composition of selected herbal infusions and their anti-inflammatory effect on a colonic model in vitro in HT-29 cells. Cogent Food Agric. 2015 doi: 10.1080/23311932.2015.1059033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fayed M.A.A., Abouelela M.E., Refaey M.S. Heliotropium ramosissimum metabolic profiling, in silico and in vitro evaluation with potent selective cytotoxicity against colorectal carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2022;12:12539. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-16552-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bakr R.O., Amer R.I., Attia D., et al. In-vivo wound healing activity of a novel composite sponge loaded with mucilage and lipoidal matter of Hibiscus species. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;135 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khalil H., El Malah T., El Maksoud A.I.A., El Halfawy I., El Rashedy A.A., El Hefnawy M. Identification of novel and efficacious chemical compounds that disturb influenza a virus entry in vitro. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:304. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abd El Maksoud A.I., Taher R.F., Gaara A.H., et al. Selective regulation of B-Raf dependent K-Ras/mitogen-activated protein by natural occurring multi-kinase inhibitors in cancer cells. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1220. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.El-Fadl H.M.A., Hagag N.M., El-Shafei R.A., et al. Effective targeting of Raf-1 and its associated autophagy by novel extracted peptide for treating breast cancer cells. Front Oncol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.682596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qian X., Yang L. ROCK2 knockdown alleviates LPS–induced inflammatory injury and apoptosis of renal tubular epithelial cells via the NF–κB/NLRP3 signaling pathway. Exp Ther Med. 2022;24:603. doi: 10.3892/etm.2022.11540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khalil H., Abd El Maksoud A.I., Roshdey T., El-Masry S. Guava flavonoid glycosides prevent influenza A virus infection via rescue of P53 activity. J Med Virol. 2019;91:45–55. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taher R.F., Al-Karmalawy A.A., Abd El Maksoud A.I., et al. Two new flavonoids and anticancer activity of Hymenosporum flavum: in vitro and molecular docking studies. J Herbmed Pharmacol. 2021;10:443–458. doi: 10.34172/jhp.2021.52. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morikawa A., Takeuchi T., Kito Y., et al. Expression of Beclin-1 in the microenvironment of invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast: correlation with prognosis and the cancer-stromal interaction. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khalil H., Tazi M., Caution K., et al. Aging is associated with hypermethylation of autophagy genes in macrophages. Epigenetics. 2016;11:381–388. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2016.1144007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khalil H., Arfa M., El-Masrey S., El-Sherbini S.M., Abd-Elaziz A.A. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of interleukins associated with hepatitis C virus infection in Egypt. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2017;11:261–268. doi: 10.3855/jidc.8127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khalil H., Abd El Maksoud A.I., Alian A., et al. Interruption of autophagosome formation in cardiovascular disease, an evidence for protective response of autophagy. Immunol Invest. 2020;49:249–263. doi: 10.1080/08820139.2019.1635619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rao X., Huang X., Zhou Z., Lin X. An improvement of the 2(-delta delta CT) method for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction data analysis. Biostat Bioinforma Biomath. 2013;3:71–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stoddart M.J. Cell viability assays: introduction. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;740:1–6. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-108-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Polyak K. Heterogeneity in breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3786–3788. doi: 10.1172/JCI60534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tomeh M., Hadianamrei R., Zhao X. A review of curcumin and its derivatives as anticancer agents. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1033. doi: 10.3390/ijms20051033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Khan N., Mukhtar H. Multitargeted therapy of cancer by green tea polyphenols. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sohn S.I., Priya A., Balasubramaniam B., et al. Biomedical applications and bioavailability of curcumin—an updated overview. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:2102. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13122102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Meeran S.M., Patel S.N., Chan T.H., Tollefsbol T.O. A novel prodrug of epigallocatechin-3-gallate: differential epigenetic hTERT repression in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4:1243–1254. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rauf A., Imran M., Khan I.A., ur-Rehman M., Gilani S.A., Mehmood Z., Mubarak M.S. Anticancer potential of quercetin: a comprehensive review. Phytother Res. 2018;32:2109–2130. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xiao X., Guo L., Dai W., et al. Green tea-derived theabrownin suppresses human non-small cell lung carcinoma in xenograft model through activation of not only p53 signaling but also MAPK/JNK signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022;291 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hatcher H., Planalp R., Cho J., Torti F.M., Torti S.V. Curcumin: From ancient medicine to current clinical trials. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1631–1652. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7452-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Doello K., Ortiz R., Alvarez P.J., Melguizo C., Cabeza L., Prados J. Latest in vitro and in vivo assay, clinical trials and patents in cancer treatment using curcumin: a literature review. Nutr Cancer. 2018;70:569–578. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2018.1464347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hu S., Xu Y., Meng L., Huang L., Sun H. Curcumin inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis of breast cancer cells. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16:1266–1272. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wright L.E., Frye J.B., Gorti B., Timmermann B.N., Funk J.L. Bioactivity of turmeric-derived curcuminoids and related metabolites in breast cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19:6218–6225. doi: 10.2174/1381612811319340013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rocca A., Braga L., Volpe M.C., Maiocchi S., Generali D. The predictive and prognostic role of RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway alterations in breast cancer: revision of the literature and comparison with the analysis of cancer genomic datasets. Cancers. 2022;14:5306. doi: 10.3390/cancers14215306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leontovich A.A., Zhang S., Quatraro C., et al. Raf-1 oncogenic signaling is linked to activation of mesenchymal to epithelial transition pathway in metastatic breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2012;40:1858–1864. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu X., Carr H.S., Dan I., Ruvolo P.P., Frost J.A. p21 activated kinase 5 activates Raf-1 and targets it to mitochondria. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105:167–175. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Beeram M., Patnaik A., Rowinsky E.K. Raf: a strategic target for therapeutic development against cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6771–6790. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wu L.X., Xu J.H., Wu G.H., Chen Y.Z. Inhibitory effect of curcumin on proliferation of K562 cells involves down-regulation of p210(bcr/abl) initiated Ras signal transduction pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2003;24:1155–1160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bonner T.I., Kerby S.B., Sutrave P., Gunnell M.A., Mark G., Rapp U.R. Structure and biological activity of human homologs of the raf/mil oncogene. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:1400–1407. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.6.1400-1407.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rubtsova M., Dontsova O. Human telomerase RNA: telomerase component or more? Biomolecules. 2020;10:873. doi: 10.3390/biom10060873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ouellette M.M., Wright W.E., Shay J.W. Targeting telomerase-expressing cancer cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:1433–1442. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01279.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ramachandran C., Fonseca H.B., Jhabvala P., Escalon E.A., Melnick S.J. Curcumin inhibits telomerase activity through human telomerase reverse transcritpase in MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. Cancer Lett. 2002;184:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Klawitter M., Quero L., Klasen J., et al. Curcuma DMSO extracts and curcumin exhibit an anti-inflammatory and anti-catabolic effect on human intervertebral disc cells, possibly by influencing TLR2 expression and JNK activity. J Inflamm. 2012;9:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Strasser E.-M., Wessner B., Manhart N., Roth E. The relationship between the anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin and cellular glutathione content in myelomonocytic cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;70:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kang D., Park W., Lee S., Kim J.H., Song J.J. Crosstalk from survival to necrotic death coexists in DU-145 cells by curcumin treatment. Cell Signal. 2013;25:1288–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mortezaee K., Najafi M. Immune system in cancer radiotherapy: Resistance mechanisms and therapy perspectives. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;157 doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.103180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rodriguez-Ruiz M.E., Vitale I., Harrington K.J., Melero I., Galluzzi L. Immunological impact of cell death signaling driven by radiation on the tumor microenvironment. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:120–134. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0561-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Teiten M.H., Gaigneaux A., Chateauvieux S., et al. Identification of differentially expressed proteins in curcumin-treated prostate cancer cell lines. OMICS. 2012;16:289–300. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Verzella D., Pescatore A., Capece D., et al. Life, death, and autophagy in cancer: NF-κB turns up everywhere. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:210. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2399-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Leijte G.P., Custers H., Gerretsen J., et al. Increased plasma levels of danger-associated molecular patterns are associated with immune suppression and postoperative infections in patients undergoing cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Front Immunol. 2018;9:663. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Monjazeb A.M., Schalper K.A., Villarroel-Espindola F., Nguyen A., Shiao S.L., Young K. Effects of radiation on the tumor microenvironment. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2020;30:145–157. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2019.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sadeghi Rad H., Monkman J., Warkiani M.E., et al. Understanding the tumor microenvironment for effective immunotherapy. Med Res Rev. 2021;41:1474–1498. doi: 10.1002/med.21765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang Y., Lu J., Jiang B., Guo J. The roles of curcumin in regulating the tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment. Oncol Lett. 2020;19:3059–3070. doi: 10.3892/ol.2020.11437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Li W., Wang H., Ma Z., et al. Multi-omics analysis of microenvironment characteristics and immune escape mechanisms of hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1019. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu C., Wu S., Meng X., et al. Predictive value of peripheral regulatory T cells in non-small cell lung cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Oncotarget. 2017;8:43427–43438. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]