Intracardiac tumours require extensive imaging to characterize, prognosticate, and guide timing and approach of surgical resection. We describe the case of a 48-year-old woman with morbid obesity (body mass index [BMI]: 64) who, upon preoperative investigations for bariatric surgery, had an incidental finding of a 7-cm middle mediastinal mass. Computed tomography (CT) suggested the origin was extracardiac; however, echocardiography suggested it was within the ventricular cavity. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was not possible because of bore-size limitations. This case highlights clinical decision-making challenges in the management of cardiac tumours without tissue diagnosis and the critical role of multimodal imaging to guide surgical intervention.

Case

We present the case of a 48-year-old woman with morbid obesity (BMI: 64), who underwent preoperative investigations for bariatric surgery and had an incidental finding of a 7-cm mass in the middle mediastinum. She was minimally symptomatic, with occasional episodes of presyncope and mild dyspnea, which was attributed to her morbid obesity and sedentary status. Her relevant past medical history consisted of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obstructive sleep apnea, requiring continuous positive airway pressure. In general, she had otherwise been well, awaiting her bariatric surgery, without any fatigue or constitutional symptoms. Two years before, the patient had a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) performed for a presyncopal episode, which demonstrated normal biventricular function and normal valvular function without any evidence of a mass.

The initial CT scan revealed a 7-cm middle mediastinal mass that was believed to originate from the pericardium. An electrocardiogram (ECG)-gated cardiac CT with intravenous contrast (Fig. 1, A-C) was performed to improve tissue contrast and minimize motion artifact to elucidate the mass better. This suggested that it was a well-circumscribed cystic mass (mean 30 Hounsfield units) pushing into the right ventricle (RV) from the middle mediastinum, compatible with a pericardial or duplication cyst. To further characterize the lesion—detail its exact location, size, appearance, relationship to adjacent structures, and risk of malignancy—various other imaging modalities were employed. A TTE provided temporal resolution to determine the impact on cardiac structures and function. This demonstrated a dilated RV with normal function, trace tricuspid insufficiency, and also suggested that the mass was extracardiac in origin, causing severe RV compression. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) was used to provide further anatomic clarity, which revealed severe RV luminal loss but raised the possibility that the tumour had eroded into or through the RV free wall (Fig. 1D). At this point, we believed that there was a high likelihood that the tumour was benign and considered whether or not bariatric surgery should just proceed ahead, as the tumour did not appear to be causing any hemodynamic compromise. However, with the remote chance of a more ominous etiology, we sought further imaging guidance. An MRI was attempted for further tumour characterization, as this modality has the best spatial resolution for tissue. However, this was unsuccessful because of MR bore-size limitations. We then pursued 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET) to determine the risk of malignancy, which identified a well-defined cystic/proteinaceous tumour intimate to the pericardium, protruding into the body of the RV, with moderate peripheral FDG uptake, favoured to be in the adjacent RV, consistent with a benign etiology. Cardiac catheterization demonstrated normal coronary arteries without any tumour feeder vessels.

Figure 1.

Determining mass origin. Multimodal imaging used to localize and define the mass. (A) Electrocardiogram (ECG)-gated cardiac computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast in axial plane, (B) ECG-gated cardiac CT with intravenous contrast in sagittal plane, (C) 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography CT scan in the axial plane demonstrating minimal radiotracer uptake into the mass, suggestive of a benign process, and (D) preoperative transesophageal echocardiography demonstrating concern for right ventricular invasion and right ventricular compromise in modified right ventricular inflow-outflow view with colour Doppler demonstrating no flow within the mass. Asterisk = mass; arrow = right ventricle; solid arrowhead = left ventricular outflow tract; open arrowhead = pulmonary artery.

Clinical discussions focused on balancing the increased perioperative risks secondary to her morbid obesity and likely benign etiology of this tumour with the patient’s strong desire for surgical resection. We initially contemplated a robotic assisted pericardial cyst resection to reduce the perioperative impact on the patient; however, CT imaging suggested that this would be very difficult with her body habitus. More importantly, with further imaging suggesting that the tumour had invaded through the RV free wall, we thought that it was more appropriate to attempt resection through a midline sternotomy.

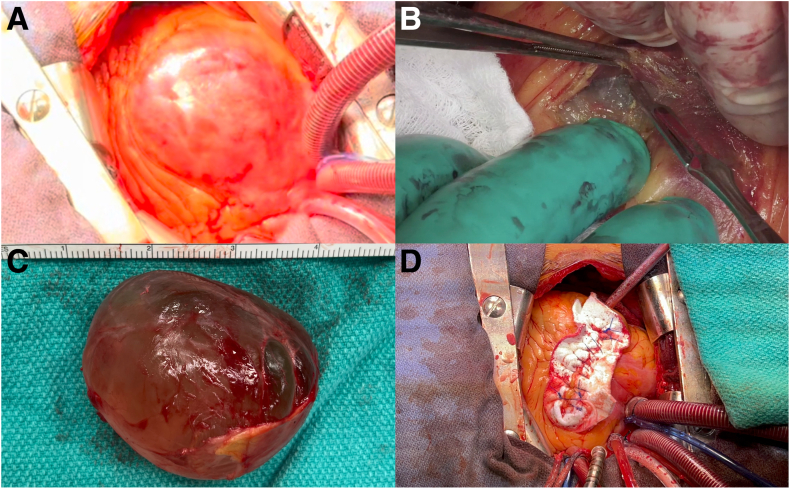

At operation, we found that the pericardium was moving independently from the heart and that, surprisingly, the tumour was completely encapsulated within the RV. As such, the patient was heparinized, placed on full cardiopulmonary bypass, and underwent cardioplegic arrest. The anterior RV was incised, and the cystic tumour was meticulously excised with sharp dissection and enucleated out of the RV free wall without rupture (Fig. 2; Video 1

, view video online). It had the macroscopic appearance of a cystic mass. The large mass (Fig. 2C) was sent for pathologic analysis, and frozen section specimens of the adjacent RV free wall were negative for malignancy. Following resection, we noticed that a papillary muscle supporting the tricuspid valve was displaced and near rupture. It was translocated and reinforced with pledgeted braided sutures to the base of the RV. The RV defect was then closed with a large bovine pericardial patch and felt.

, view video online). It had the macroscopic appearance of a cystic mass. The large mass (Fig. 2C) was sent for pathologic analysis, and frozen section specimens of the adjacent RV free wall were negative for malignancy. Following resection, we noticed that a papillary muscle supporting the tricuspid valve was displaced and near rupture. It was translocated and reinforced with pledgeted braided sutures to the base of the RV. The RV defect was then closed with a large bovine pericardial patch and felt.

Figure 2.

Surgical management of a pericardial vs intracardiac tumour. Intraoperative images demonstrating (A) intracardiac origin of the cystic mass, (B) sharp dissection to enucleate the mass, (C) successfully enucleated 7-cm cystic tumour, and (D) right ventricular defect repaired with a bovine pericardial patch and felt.

The patient had an unremarkable postoperative course and was discharged 6 days after surgery. Her postoperative echocardiogram demonstrated a left ventricular ejection fraction of 55% to 60%, mild-to-moderately reduced RV function and mild-to-moderate tricuspid regurgitation. Final pathology revealed that the tumour was an intracardiac mesothelial cyst, with no features of malignancy and with immunophenotype confirming pericardial origin.

Cardiovascular imaging has a central role in the diagnosis and management of cardiac tumours. The current literature suggests that various imaging modalities should be used to define these rare tumours further, including contrast echocardiography, transesophageal echocardiography, PET, CT, and MRI.1 This case highlights important imaging challenges and limitations in characterizing cardiac tumours and, particularly in this case, clarifying the extracardiac vs intracardiac origin. The potential for the mass to be intracardiac, and the fact that no mass was identified 2 years before, raised concern for a malignant etiology. Assessing the malignancy risk is essential to offer appropriate treatment and avoid any delays. Malignant cardiac masses should be considered for induction therapy with chemotherapy and radiation, followed by surgical resection; however, unlike most other cancers, histologic tissue diagnosis is rarely confirmed before surgical resection. In this case, we suspected a benign etiology, given its cystic features and middle mediastinal presentation; however, the potential RV invasion was concerning. Ultimately, the mass was found to be a mesothelial cyst: a rare, benign serosal neoplasm typically originating in the peritoneum but occasionally from the pericardium. Reviewing recent literature revealed 1 report of an intramyocardial mesothelial inclusion cyst found in the left ventricle, although it was not pericardial in origin.2 Another case involved a mesothelial cyst that was obstructing the RV outflow tract; however, this also did not originate from the pericardium.3 Finally, assessing the symptomatology and hemodynamic impact of the mass are necessary to evaluate whether resection is necessary.

In conclusion, this case highlights challenges in the management of atypically presenting cardiac tumours. It also demonstrates the crucial role of multimodal imaging to guide management and its limitations when the tumour is in an unusual location or when the patient has morbid obesity. In this case, the patient underwent successful surgical resection for an extremely rare mesothelial intracardiac cyst of pericardial origin.

Novel Teaching Points.

-

•

Multimodality imaging consisting of transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography, CT, PET, and MRI is required to characterize cardiac masses and provide adequate information for management decisions and surgical planning.

-

•

Histologic determination of cardiac masses is often impossible before surgical excision.

-

•

Mesothelial cysts are a rare form of benign neoplasm emerging from serosal tissue. Pericardial mesothelial cysts are particularly rare.

-

•

Benign cardiac masses may require surgical management if they cause symptoms or affect hemodynamics.

Acknowledgments

Ethics Statement

This publication adheres to ethical guidelines and patient consent was obtained.

Patient Consent

The authors confirm that a patient consent form has been obtained for this article.

Funding Sources

No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures

Dr Chu is supported as the Ray and Margaret Elliott Chair in Surgical Innovation and has received Speaker’s honoraria from Medtronic, Edwards, Terumo Aortic, and Artivion. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

See page 609 for disclosure information.

To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit CJC Open at https://www.cjcopen.ca/ and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjco.2023.11.020.

Supplementary Material

Diagnosis and management of pericardial vs intracardiac cyst. Video summary of the multimodal imaging, intraoperative management, and postoperative results.

References

- 1.Tyebally S., Chen D., Bhattacharyya S., et al. Cardiac tumors: JACC CardioOncology State-of-the-Art Review. JACC CardioOncol. 2020;2:293–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alwis S., Salmasi M.Y., Raja S.G. A rare case of an intramyocardial mesothelial inclusion cyst. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9 doi: 10.1002/ccr3.5024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kotha V.K., Yan A.T., Prabhudesai V., et al. Benign intramyocardial mesothelial cyst in the right ventricular outflow tract: computed tomography and cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging appearances. Circulation. 2014;130:e275–e277. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Diagnosis and management of pericardial vs intracardiac cyst. Video summary of the multimodal imaging, intraoperative management, and postoperative results.