Abstract

The first description of an active form of a recombinant human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) reverse transcriptase (RT) and subsequent predictions of its amino acid sequence and quaternary structure are reported here. By using amino acid alignment methods, the NH2 and COOH termini of the RT, RNase H (RH), and integrase (IN) domains of the Pol polyprotein were determined. The HTLV-1 RT seems to be unique since its NH2 terminus is probably encoded by the pro open reading frame (ORF) fused downstream, via a transframe peptide, to the polypeptide encoded by the pol ORF. The HTLV-1 Pol amino acid sequence was revealed to be highly similar to that of Rous sarcoma virus (RSV), particularly at the RT-RH hinge region. These two domains remain linked for RSV; this may also be the case for HTLV-1. In light of these results, RT, RT-RH, and RT-RH-IN genes were constructed and introduced into His-tagged protein expression vectors. The corresponding proteins were synthesized in vitro, and the DNA polymerase activities of different protein combinations were tested. Solely the RT-RH–RT-RH-IN combination was found to have a significant activity level. Velocity sedimentation analysis suggested that the HTLV-1 RT-RH and RT-RH-IN monomers are likely associated in an oligomeric structure, probably of the α3/β type.

Reverse transcriptase (RT) is one of the key enzymes in the life cycle of retroviruses. All retroviral RTs are encoded by the pol gene. The protein is translated from the full-length genomic viral mRNA as part of a large polyprotein precursor, either the Gag-Pol, the Gag-Pro-Pol, or the Pro-Pol polyprotein (26).

The gag and pol genes of retroviruses are arranged in different ways. In some retroviruses, such as murine leukemia virus (MuLV), the gag and pol genes are in the same open reading frame (ORF) and are separated by a stop codon. In other retroviruses, the two genes are found in different reading frames, either with pol overlapping gag in the −1 direction (as for Rous sarcoma virus [RSV] and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 [HIV-1]), with the pol ORF overlapping gag in the +1 direction (as for human foamy virus [26]), or with a third gene, pro, interrupting the gag and pol genes and overlapping them both (as for mouse mammary tumor virus, human T-cell leukemia virus types 1 and 2 [HTLV-1 and -2], and bovine leukemia virus [BLV] [17]). To circumvent these apparent blocks in the synthesis of the Gag-Pol or Gag-Pro-Pol fusion protein, MuLV uses stop-codon readthrough, RSV and HIV-1 employs single ribosomal frameshifting, and mouse mammary tumor virus, HTLV-1, HTLV-2, and BLV use double ribosomal frameshifting (13, 17). Human foamy virus Pol is expressed as a Pol polyprotein that is initiated at the methionine residue at position 9 in the pol gene (26). The different large polyprotein precursors are then proteolytically processed by the viral protease (PR).

The Pol domains of the various classes of viruses encode either three or four enzyme activities—PR, RT, RNase H (RH), and integrase (IN)—depending on whether the PR region is part of the pol gene, is encoded by the pro gene, or is located at the 3′ end of the gag ORF. The mature RTs from different virus families have different subunit structures; avian virus RTs are α/β heterodimers (RT-RH–RT-RH-IN) (11), MuLV enzymes are monomers (RT-RH) (10, 48), and the RT of HIV-1 is a heterodimer (RT-RH–RT; p66/p51) (7, 25).

HTLV-1 is the etiological agent of adult T-cell leukemia (15, 37, 38, 49). To date, very little is known about the HTLV-1 RT, although it has been purified from virions as a 95-kDa protein and enzymatically characterized (41). The complete HTLV-1 provirus and various HTLV-1 genes, including the IN coding region (2), have already been cloned and expressed separately, but the RT domain of the pol gene has never been cloned independently. The NH2- and COOH-terminal sequences of the active enzyme remain to be determined, and the expression of an enzymatically active recombinant form of RT has not previously been reported. Information concerning HTLV-1 RT has been difficult to obtain for two reasons. (i) The two frameshift events required for Gag-Pro-Pol polyprotein synthesis occur at a low frequency (13 and 0.9%, respectively, for HTLV-2 [27]), and hence the Pol protein is produced in very small amounts; thus, to obtain substantial amounts of the RT enzyme, HTLV-1 particles must be purified from large quantities of cell culture medium (41). (ii) The HTLV-1 pol gene is GC rich and contains many inverted-repeat sequences of 7 to 12 bases (54% of the gene). This likely explains the high rate of recombination observed when this gene is manipulated. These difficulties notwithstanding, we have persisted in our attempts to obtain an active enzyme, using recombinant technology because of its importance in screening for RT inhibitors.

To define the putative coding regions for HTLV-1 RT, RH, and IN, the protein sequences encoded by the HTLV-1 pro and pol genes were aligned with those encoded by other retroviral pol genes. The results suggest that (i) unlike other retrovirus RTs, the HTLV-1 Pol enzyme is encoded by both the pro and pol ORFs; and (ii) a cleavage site between RH and IN is likely to exist, while a cleavage site between RT and RH is unlikely to be present. This has provided information necessary for the development of HTLV-1 Pol expression constructs suitable for the detection of RT activity in vitro. We demonstrate that only the combination RT-RH–RT-RH-IN exhibits detectable RT activity. Rate zonal centrifugation of a mixture of both proteins revealed that a fraction sedimented in the 180- to 240-kDa range. Analysis of the 210-kDa fraction’s RT-RH and RT-RH-IN contents showed that they were present at an approximate ratio of 3:1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and DNA methods.

Escherichia coli DH5α and STBL2 (GIBCO-BRL) were used. Plasmid pBSM13+ was used for all of the constructions, and plasmid pET-16b (Novagen) provided the (His)10 cassette. The HTLV-1 pol gene constructs were derived from the HTLV-1 proviral clone pMT-2 (32). DNA manipulations were carried out by standard methods (43). MuLV RT was from GIBCO-BRL.

Amino acid sequence alignments.

The following sequences were obtained from version 14.0 of the Protein Identification Resource databank: GNVWH3 (HIV-1 pol) (39), GNFV1R (RSV pol) (44), GNMV1M (MuLV pol) (47), and GNLJGB (BLV pol) (42). The DNA sequence of HTLV-1 strain MT-2 was established in our laboratory. The sequence of HTLV-2 λH6.0 was translated from its DNA sequence taken from the literature (46). Alignments were performed with the CLUSTAL program (14), Hydrophobic Cluster Analysis (HCA) plot V2 version 2.0 (23), and Dayhoff Mutation Data Matrix (MDM-78) (5).

Construction of in vitro expression vectors.

To circumvent the occurrence of recombinations during cloning manipulations, we have proceeded by a protocol involving several steps (detailed cloning procedures are available on request). Briefly, a basic vector containing pol gene DNA, extending from the NarI site (nucleotide [nt] 2531) to the SalI site (nt 5672) of HTLV-1 provirus clone pMT-2 (using the numbering system of Seiki et al. [45]), was obtained. The 5′-end DNA region was modified by PCR with primer 2520-2539 (5′-CGCACAAGCATGCAGATCTACCATGGTGCCAATACAGGCGCCAGCC-3′) and primer 2635-2580 (5′-CCTTCCGGACCAAGTGTTGCAAGGCCTGGAGGCGTTCTGGA TTAAGAGGGAACTGGC-3′). The resulting expression clone, pPOL, is described in Results. Two other plasmids, pRT and pRT-RH, were derived from the pPOL plasmid by site-directed mutagenesis with primers that add stop codons at nt 3913 (primer 3913-3895, 5′-TCTCTAGACTATTAAAACAGGCAGGGGGCGGT-3′) and at nt 4294 (primer 4315-4276, 5′-GTAGTTCTGTAGGAGAGCGCTACAGGACAGGGGTGATTAG-3′). Plasmids pPOL, pRT, and pRT-RH were used to generate vectors, designated pHPOL, pHRT-RH, and pHRT, respectively, for expression of His-tagged fusion proteins. DNA sequences that were subjected to PCR or site-directed mutagenesis were confirmed by sequencing.

Cell-free transcription and translation.

Protein synthesis was carried out in one stage with a simultaneous in vitro transcription-translation system (TNT Coupled Reticulocyte Lysate System) as recommended by the manufacturer (Promega). The [35S]methionine (1,000 Ci/mmol)-labeled translation products were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (21). The [35S]methionine-labeled proteins were visualized by fluorography.

Purification of histidine-tagged HTLV-1 RT.

Purification of the His-tagged fusion proteins was performed with a TALON metal affinity resin in accordance with the protocol described by the manufacturer (Clontech). The recovered proteins were then concentrated in NANOSEP microconcentrators (Pall Filtron) and subjected to RT assays.

RT assays.

The RT reaction mixture (41) contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM KCl, 0.01% Triton X-100, 30 mM MgCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 1.5% glycerol, 1 mg of bovine serum albumin (BSA) per ml, 10 μg of poly(rC) · oligo(dG) per ml, 100 μCi of [3H]dGTP (7.7 Ci/mmol; ICN) per ml, and 20 μl of protein extract 1 plus 20 μl of protein extract 2 (with each 20-μl extract volume originating from 70 μl of in vitro transcription-translation mixture containing either pHRT, pHRT-RH, or pHPOL DNA or no DNA) in a 0.1-ml volume. The RT assays were carried out for 1 h at 37°C. The 3H-labeled acid-insoluble materials were collected by filtration on 0.45-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose filters (Millipore). The amount of incorporated [3H]dGMP was measured with a liquid scintillation counter (LS 6,000 IC; Beckman).

Proteolytic processing of Pol polyprotein by BLV PR.

Proteolytic processing of Pol by the BLV PR was achieved as described previously (30) with an incubation time of 4 h.

Sucrose density gradient sedimentation.

A crude mixture of [35S]methionine-labeled RT-RH and RT-RH-IN (25 μl of each in vitro transcription-translation medium) was adjusted in 0.3 M KCl and layered onto a 5-ml linear 5 to 20% sucrose density gradient in a solution containing 0.3 M KCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 10% glycerol. Molecular mass markers of 340 kDa (α2-macroglobulin; 1 μg), 200 kDa (β-amylase; 7.5 μg), 150 kDa (alcohol dehydrogenase; 12.5 μg), and 69 kDa (BSA; 2.5 μg) were layered onto a parallel gradient. The gradients were centrifuged at 45,000 rpm in a Kontron SW55 rotor at 4°C for 19 h. Fractions (200 μl) were collected, and the proteins were precipitated with cold 10% trichloroacetic acid and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Radiolabeled proteins were detected by autoradiography and quantified with a Packard Instant Imager instrument. Molecular mass markers were visualized after Coomassie blue staining.

RESULTS

Identification of the NH2-terminal sequence of HTLV-1 RT.

It has been reported that HTLV-1 pol gene products, i.e., RT, RH, and IN, are synthesized as part of a Gag-Pro-Pol polyprotein produced by two consecutive ribosomal frameshifts, the first occurring in the gag-pro overlap (12, 35) and the second occurring in the pro-pol overlap (34) (Fig. 1A). The precursor may be subsequently processed into mature RT by the retroviral PR.

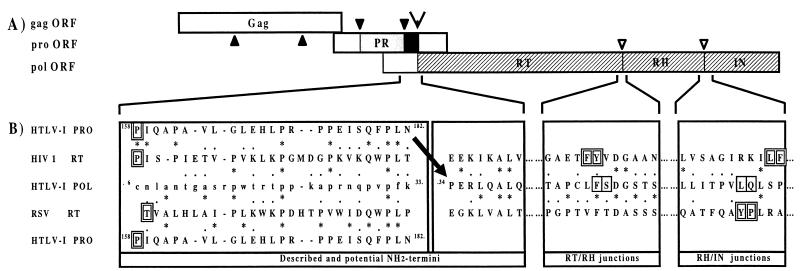

FIG. 1.

Strategy for expression of the HTLV-1 Pol polyprotein and localization of encoding domains. (A) Schematic presentation of gag, pro, and pol ORFs. Gray box, mature PR; black box, part of pro ORF which would encode the RT NH2 terminus; open arrowhead, frameshift site; hatched box, domains that encode part of RT, RH, and IN in the pol ORF; closed and open inverted triangles, described and hypothesized PR maturation sites, respectively. (B) Alignments of different NH2 and COOH termini of HIV-1 and RSV RT, RH, and IN domains with amino acids encoded by the HTLV-1 pro ORF’s 3′ end and pol ORFs. Amino acids in lowercase letters in the HTLV-1 pol ORF do not encode the RT protein. Amino acids in capital letters in the HTLV-1 pro and pol ORFs encode the NH2-terminal segment of RT. Alignments were generated with the CLUSTAL and HCA programs. Identification of perfectly conserved (∗) or well-conserved ( · ) amino acids was made with MDM-78 (5). I and L are considered to be identical. The arrow indicates the shift from the pro to the pol HTLV-1 ORF. Double-boxed amino acids are previously described PR cleavage sites leading to mature (i) PR, RT, RH, and IN of HIV-1; (ii) RT-RH and IN of RSV; or (iii) PR of HTLV-1. Single-boxed amino acids are the deduced junctions between the HTLV-1 RT-RH and RH-IN domains.

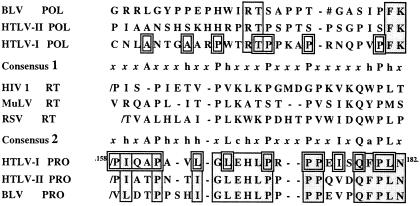

Because the 20 NH2-terminal amino acids of HIV-1 RT are absolutely required for its polymerization activity (16), it was deemed important to identify precisely the NH2 terminus of the HTLV-1 RT protein. Comparison analyses of the amino acid sequences encoded by the pol genes of different retroviruses, conducted by several authors, have provided information for the identification of the RT, RH, and IN domains (3, 18). This identification was based on the high level of amino acid conservation among Pol polyproteins. This kind of approach enabled us to determine the amino and carboxy termini of the HTLV-1 RT. HTLV-1, HIV-1, and RSV protein sequences were aligned (Fig. 1B), using both the CLUSTAL and HCA programs. The amino acid sequence encoded in the HTLV-1 pol ORF downstream of the frameshift site, beginning at P34 (numbering from the first amino acid encoded in the HTLV-1 pol ORF), aligned well with those of the RSV and HIV-1 RTs (Fig. 1B). This was consistent with the alignments proposed earlier by Barber et al. (3) and Johnson et al. (18). Surprisingly, these authors have also proposed the alignment of the HTLV-1 pol ORF sequence located upstream of the frameshift site (Fig. 1B) with those of the RSV and HIV-1 RT NH2 termini. This alignment seemed to be inappropriate for two reasons: (i) to date, there is no known mechanism that would permit the expression of HTLV-1 pol ORF-encoded amino acids located upstream of the frameshift site; and (ii) the results of our amino acid sequence comparisons suggest a different alignment (described below). For the segment encompassing amino acids 1 to 33 encoded in the HTLV-1 pol ORF upstream of the frameshift signal (Fig. 1B), the sequence similarity to the NH2 termini of the RSV and HIV-1 RTs was limited. These observations suggest that the amino terminus of the HTLV-1 RT is not encoded by the pol ORF. Because the 3′ end of the HTLV-1 pro ORF aligned better with the RSV and HIV-1 RTs, and because the NH2 termini of numerous RTs are generated by protease cleavage of the polyprotein precursor, we hypothesized that the COOH-terminal Pro peptide would correspond to the NH2 terminus of the HTLV-1 RT. Thus, the peptide encoded by the portion of the pro ORF located downstream of the L157-P158 PR cleavage site (19, 30) through N182, the last amino acid decoded before the shift into the pol frame, was analyzed. If this peptide has biological significance, it should be conserved among all retroviral RTs and particularly among the BLV-HTLV family RTs. The consensus sequence deduced from the alignment of BLV-HTLV Pro peptides revealed that the three sequences were highly similar and contained two perfectly conserved motifs, GLEHLP and QFPLN (Fig. 2). Such a level of conservation was not observed in the corresponding pol frame sequences. Then, the published NH2-terminal sequences of the RSV, MuLV, and HIV-1 RTs were compared with either the P158-to-N182 Pro HTLV-1 peptide or amino acids 6 to 33 of the HTLV-1 pol ORF sequence located upstream of the pro-pol frameshift site. Residues of the same class shared by the HTLV-1 sequence and at least two of the three RT sequences were noted in consensus sequences (Fig. 2). Consensus sequence 2, obtained when comparing the HTLV-1 pro ORF sequence to RSV, MuLV, and HIV-1 RT sequences, was much more significant than that obtained when comparing the three RT sequences with the HTLV-1 pol ORF sequence (consensus sequence 1). This was particularly evident for the GLEHLP and QFPLN motifs that were included in two consensus motifs, x-leucine-charged amino acid-hydrophobic amino acid-x-proline and glutamine-aromatic amino acid-proline-leucine-x (where x is any amino acid). Moreover, in the 25-residue Pro peptide P158 to N182, 14 residues (double boxed in Fig. 2) were also present in at least one of the RSV, MuLV, or HIV-1 RT NH2 termini. This was absolutely not the case for the Pol peptide, which shared only seven residues. Consequently, we propose that the P158-to-N182 peptide encoded in the HTLV-1 pro ORF corresponds to the NH2 terminus of the HTLV-1 RT. The NH2-terminal segment of the HTLV-1 RT would thus result from a fusion of amino acids 158 to 182 encoded in the pro ORF with amino acids 34 to 896 encoded in the pol ORF, the fusion point being the transframe N-P dipeptide translated at the frameshift site (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 2.

Comparative alignments of HTLV-BLV pol ORF NH2-terminal domains and HTLV-BLV pro ORF COOH-terminal domains with previously characterized HIV-1, MuLV, and RSV RT NH2 termini. Residues in single gray boxes are those conserved in HTLV-1, HTLV-2, and BLV. Double-boxed amino acids are HTLV-1 pro or pol ORF residues shared at least once with either HIV-1, MuLV, or RSV. Consensus sequence 1 was obtained by comparing the HTLV-1 pol ORF-encoded amino acids with those of HIV-1, MuLV, and RSV RTs, and consensus sequence 2 was obtained by comparing the HTLV-1 pro ORF-encoded amino acids with HIV-1, MuLV, and RSV RT residues. Perfectly conserved (capital letters), hydrophobic (h), charged (c), and aromatic (a) residues are noted in the consensus sequences when they are present in the HTLV-1 sequence and in at least two of the previously described RTs. #, stop codon; -, amino acid insertion; /, previously described cleavage site.

Localization of possible cleavage sites leading to the mature Pol-derived proteins.

To define the possible cleavage sites between the RT-RH and RH-IN domains and, thus, RH and IN NH2 and COOH termini, HTLV-1 RH and IN domain amino acid sequences were also aligned with those of HIV-1 and RSV (Fig. 1B). The comparisons were made with both the CLUSTAL and HCA programs, also making use of the previously published sequence comparisons of Barber et al. (3) and Johnson et al. (18).

Despite the presence of highly conserved residues, analysis of the HTLV-1 sequence at the RT-RH junction did not reveal any obvious cleavage sites. The HTLV-1 Pol sequence at this RT-RH junction aligned well with that of HIV-1 (there are 2 perfectly conserved and 6 well-conserved residues [8 of 12 conserved]) but aligned much better with that of RSV (with 5 perfectly conserved and 7 well-conserved residues [12 of 12 conserved]). This suggests that, like for RSV, there is no RT-RH cleavage in HTLV-1, with the RT domain remaining linked to the RH domain. If this was not the case, the best candidate for a cleavage site between the RT and RH domains would be located after F472. Based on this hypothesis, S473 would be the NH2-terminal residue of the HTLV-1 RH domain.

Alignment of the IN domains of Pol sequences (Fig. 1B) was imposed by a conserved pair of His and Cys residues (the HHCC motif, downstream of the sequence shown here) in the amino-terminal portion of these proteins. Results of HCA alignments suggested that for HTLV-1 there is a region containing three potential cleavage sites, L593-L594, V598-L599, and L599-Q600. PR cleavage sites containing L in such a position exist in HTLV-1 Gag and Pro precursors; cleavages at L-P and L-V sites produce the mature matrix, capsid, nucleocapsid, and PR proteins (4, 12, 19, 30, 36). Recently, Balakrishnan and Jonsson reported a study on a bacterially expressed HTLV-1 IN (2); they utilized the NH2-terminal amino acid V598, which may be part of the P597-V598 putative PR cleavage site. Nevertheless, in our HCA analysis, the L-Q environment seemed to be more appropriate for a PR cleavage site. Thus, Q600 would be the NH2-terminal residue of the HTLV-1 IN. The COOH-terminal residue of IN is probably G896, the last amino acid of the Pol polyprotein.

Thus, we propose that (i) the HTLV-1 RT domain encompasses amino acids P158 through N182 of the pro ORF as well as amino acids P34 through F472 of the pol ORF, (ii) the RH domain extends from S473 through L599 of the pol ORF, and (iii) the IN domain encompasses amino acids Q600 to G896 of the pol ORF.

Construction and expression of a recombinant Pol polyprotein precursor: its cleavage by the retroviral PR.

The expression of recombinant HTLV-1 Pol proteins requires the addition of a start codon and the mimicking of the ribosomal frameshift event in the pro-pol overlap to produce a unique RT-RH-IN polyprotein. A 5′ PCR primer brought the initiator codon incorporated into the Kozak consensus sequence (20), ACCATGG, in frame with the pro ORF. The first two amino acids just after the ATG codon were L and P; L was the last residue of mature HTLV-1 PR, and P was the first amino acid of mature HTLV-1 RT. The 3′ PCR primer encompassed the pro-pol overlap and contained two silent mutations in the frameshift site, so that ribosomes could not shift in the −1 direction, and a single thymine insertion, to mimic the frameshift event. This amplified 5′-terminal pol segment was introduced downstream of the T3 promoter of plasmid pBSM13(+). A 3,045-bp BspEI-SalI DNA fragment of the HTLV-1 pol gene was inserted downstream of the construct described above. The resulting recombinant plasmid, pPOL, was then subjected to coupled transcription-translation (TNT) in rabbit reticulocyte lysate, using T3 RNA polymerase. SDS-PAGE analysis of [35S]methionine-labeled proteins revealed two major translation products, of 92 and 76 kDa (Fig. 3A, lane 1). The RT-RH-IN polyprotein had an apparent molecular mass of 92 kDa. This was within the expected range, since the calculated size was 99 kDa and the RT purified from virions by Rho and coworkers was 95 kDa (41). The 76-kDa protein probably resulted from protease degradation or from internal initiation or premature termination of translation.

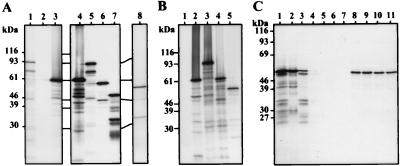

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE of in vitro-translated Pol proteins. DNA matrices were simultaneously transcribed by either T3 (A) or T7 (B) RNA polymerase and translated in the presence of [35S]methionine. Proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and fluorography. The positions of molecular mass markers positions are indicated on the left. (A) Translation products synthesized in the presence of either luciferase (lanes 3 and 4), pPOL (lanes 1 and 5), pRT-RH (lane 6), or pRT (lane 7) DNA template or no DNA template (lane 2). In vitro-synthesized, [35S]methionine-labeled POL polyprotein precursor was incubated for 4 h at 37°C with BLV protease (lane 8). (B) Translation products synthesized in the presence of either luciferase (lane 2), pHPOL (lane 3), pHRT-RH (lane 4), or pHRT (lane 5) DNA template or no DNA template (lane 1). (C) Purification of [35S]methionine-labeled, His-tagged RT protein (lane 1) on nickel resin. Lanes: 2, bound His-RT; 3, unbound His-RT; 4 to 7, fractions obtained at each resin washing step; 8 to 11, fractions of imidazole-eluted pure His-RT.

The mature, active form of an RT is produced by enzymatic processing of the Gag-Pro-Pol polyprotein by the retroviral PR. To obtain such natural processing, HTLV-1 PR and Pol proteins were simultaneously synthesized in vitro. Under these conditions, no processing was observed. In fact, HTLV-1 PR synthesized in vitro does not cleave any of its natural substrates (i.e., either Gag [29] or Pol polyproteins) and appears to be inactive. However, BLV PR has been demonstrated to efficiently mature the HTLV-1 Gag precursor (30). Therefore, to identify the maturation products of the HTLV-1 Pol precursor, the Pol polyprotein was synthesized in vitro and incubated with a BLV extract containing active PR. The PR cleavage gave rise to two processed products migrating at 54 and 36.5 kDa (Fig. 3A, lane 8), approximately equivalent to the predicted sizes of the RT-RH and IN proteins. The RT-RH protein contains five methionines, all located in the RT domain, while the IN protein contains three. Densitometric analysis revealed that the intensity of the 36.5-kDa band was 2.2 if a value of 5 was attributed to the band at 54 kDa. This was in agreement with the expected results; i.e., the protein of the lowest electrophoretic mobility is likely the RT-RH protein and the other one is likely the IN protein. The same cleavage profile has also been observed by using an insect cell extract containing active HTLV-1 PR expressed via a Gag-Pro recombinant baculovirus (data not shown). These results revealed that there was only one cleavage site in the Pol precursor and that the PR cleavage generated two proteins whose apparent molecular weights and methionine compositions approximately matched those of the RT-RH and IN proteins. The lack of cleavage between the RT and RH domains was in accordance with the conclusions of the alignment described above.

Construction of vectors leading to the expression of non-polyhistidine-linked or polyhistidine-linked RT-RH-IN, RT-RH, and RT proteins.

To define the nature of the HTLV-1 active RT, two other Pol expression vectors were derived from the pPOL plasmid. Activities of other viral RTs are more easily detected after proteolytic maturation of their Pol precursors (8, 24). The resulting RT activities are harbored by either monomeric, homodimeric, or heterodimeric enzymes. Because the above results showed that there is at least one PR cleavage site between RH and IN, the corresponding expression vector, pRT-RH, was constructed. Although our sequence alignments and in vitro proteolytic maturation suggest otherwise, a protease cleavage site may be present between the RT and RH domains. Thus, an expression vector containing the RT domain alone was constructed. Site-directed mutagenesis to create termination codons either after F472 or after L599 at the putative RT-RH and RH-IN cleavage sites, respectively, was carried out. The resulting vectors, pRT and pRT-RH, contain RT and RT-RH domains, respectively. They were used as templates for coupled transcription-translation. Two bands, with apparent molecular masses of 59 kDa (corresponding to the RT-RH polyprotein) and 48 kDa (corresponding to the RT protein), were observed (Fig. 3A, lanes 6 and 7). In order to easily purify Pol proteins, three other recombinant Pol plasmids, containing a (His)10 tag named either pHPOL, pHRT-RH, or pHRT, were constructed. These plasmids were identical to the pPOL, pRT-RH, and pRT constructs, respectively, except that a T7 promoter, an ATG start codon, and 10 in-frame histidine codons were inserted upstream of the pol gene. They directed the in vitro synthesis of the predicted His-linked RT-RH-IN, RT-RH, and RT proteins (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 to 5, respectively). Interestingly, the His-linked RT-RH-IN gene led to only one protein, of 94 kDa, suggesting that the 76-kDa protein obtained with the non-His-tagged gene resulted from a weak usage of the first start codon. These proteins could be easily purified on a nickel affinity column (Fig. 3C).

RT assays.

Active HTLV-1 RT might be an RT-RH–RT heterodimer, like the p66/p51 HIV-1 RT, or an RT-RH–RT-RH-IN heterodimer, like RSV α/β RT. It might also be an α monomer, like the MuLV and feline leukemia virus RTs, or it might be composed of another, as-yet-undescribed combination. Therefore, each HTLV-1 Pol protein synthesized in rabbit reticulocyte lysate, or pairwise combinations of them, were tested for their RT activity under well-established polymerization conditions (41). First, nonpurified Pol proteins produced in vitro were analyzed; however, none of them, not even the MuLV RT supplemented with the coupled transcription-translation extract, displayed RT activity. Thus, the coupled transcription-translation extract likely contains an inhibitor of RT activity. In the second step, to circumvent this problem, His-tagged RT-RH-IN, RT-RH, and RT proteins were synthesized in vitro, purified on nickel affinity columns, and then immediately assayed for enzymatic activity. To search for active monomers or homomultimers, the His-linked RT-RH-IN, RT-RH, and RT proteins were tested separately for their ability to incorporate [3H]dGMP in acid-insoluble material (Table 1). Then, different pairwise combinations of monomers (with the ability to heterodimerize or to oligomerize) were tested for their RT activity (Table 1). A substantial RT activity was detected only for the RT-RH–RT-RH-IN combination. With approximately 0.2 pmol of enzyme, 14.8 pmol of [3H]dGMP was incorporated into the polymer in 1 h at 37°C. These results indicate that active HTLV-1 RT is probably an RT-RH–RT-RH-IN oligomer.

TABLE 1.

RT activities of different combinations of genetically engineered HTLV-1 Pol proteins

| Content of protein extract no.:

|

Amt of [3H]dGMP incorporated (pmol)a | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| RT | —b | <0.1 |

| RT-RH | — | 0.6 |

| RT-RH-IN | — | 0.5 |

| RT | RT-RH | <0.1 |

| RT | RT-RH-IN | 0.1 |

| RT-RH | RT-RH-IN | 14.8 |

| MuLV RTc | — | 55.4 |

The enzyme assays were carried out as described in Materials and Methods, using 20 μl of extract no. 1 plus 20 μl of extract no. 2.

—, 20 μl of mock extract.

MuLV RT (40 U) was tested under the same conditions.

Quaternary structure of RT-RH–RT-RH-IN mixture.

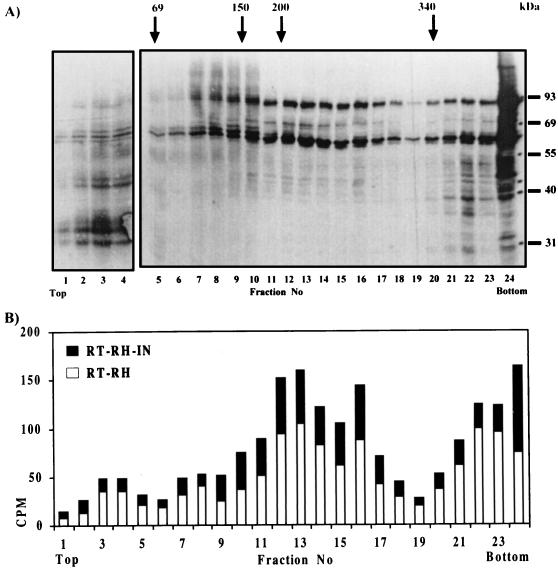

To determine the nature of the oligomeric structure formed by RT-RH and RT-RH-IN proteins when mixed together, purified His-tagged RT-RH and RT-RH-IN proteins were submitted to either exclusion chromatography, nondenaturing PAGE, or sedimentation on a sucrose density gradient. All of these trials failed, probably because of the extensive aggregation of the purified proteins. As a consequence, velocity sedimentation of a crude mixture of coupled-transcription-translation-synthesized RT-RH and RT-RH-IN proteins, adjusted in 0.3 M KCl, was examined (Fig. 4A). Half of the protein sedimented through the sucrose gradient and was recovered in the pellet in an aggregated form. The rest of the protein sedimented at an estimated molecular mass of 180 to 240 kDa. Quantification of each protein band revealed that the top of the RT-RH peak coincided with that of the RT-RH-IN peak, suggesting that both proteins were associated in a multimeric structure. This protein structure had a molecular mass higher than that expected for a heterodimeric structure but might be in accordance with a trimer or tetramer. In this oligomer, the measured RT-RT/RT-RH-IN ratio was approximately 3:1 (Fig. 4B), suggesting that three RT-RH molecules would be associated with one RT-RH-IN molecule. In view of the apparent molecular mass and the molecule ratio, it appears that the RT-RH and RT-RH-IN proteins are likely associated in an α3/β structure.

FIG. 4.

Sucrose gradient analysis of a mixture of RT-RH and RT-RH-IN proteins. (A) Both proteins were centrifuged together through a 5 to 20% sucrose gradient. Fractions were collected and subjected to trichloroacetic acid precipitation, and precipitated proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. The top and the bottom of the gradient are indicated. The positions of molecular mass markers are indicated on the right in kilodaltons. Fractions in which protein standards sedimented under the same conditions are indicated at the top of the panel. These were (from the bottom of the gradient) α2-macroglobulin (340 kDa, dimer), β-amylase (200 kDa, tetramer), alcohol dehydrogenase (150 kDa, tetramer), and BSA (69 kDa, monomer). (B) [35S]methionine-labeled proteins of each fraction were quantitated. The amounts of RT-RH-IN protein (closed bars) and of RT-RH protein (open bars) are represented for each fraction. The amount of protein in the 24th fraction is represented on a 10-fold-reduced scale.

DISCUSSION

In contrast to the HIV-1 RT, the structure-function relationship of the HTLV-1 RT has not been determined. Amino acid sequence comparisons give evidence that the NH2 terminus of the HTLV-1 RT is encoded by the pro ORF and is fused to the amino acids encoded by the pol ORF by a frameshift. According to this hypothesis, the NH2 terminus of the RT is naturally generated by the same cleavage event that produces the COOH terminus of the PR. The RT NH2 termini of numerous other retroviruses, including MuLV and HIV-1, originate from the same type of cleavage event (9). The HTLV-1 RT is unique in that it is probably encoded through the pro and pol ORFs. In the HTLV-BLV family, sequence alignments revealed a high level of sequence conservation at the 3′ end of the pro ORF, extending from the carboxy terminus of PR to the pro-pol frameshift site; in particular, two peptides are perfectly conserved. HTLV-2 and BLV may use the same coding strategy.

The amino acid comparisons revealed a high degree of similarity between the HTLV-1 Pol sequence and that of RSV, particularly at the hinge between the RT and RH domains, suggesting that like RSV, the HTLV-1 RH domain is not excised from the RT domain. Digestion of the Pol polyprotein by the protease of a related retrovirus, BLV, revealed the presence of a single PR cleavage site, probably between the RH and IN domains. Amino acid comparison predicted a region (from L593 to Q600) containing three different putative cleavage sites. These sites deviate slightly from the L-P motif generally recognized by the HTLV-1 PR (4, 30). The fact that the potential cleavage sites do not exactly match the canonical cleavage site between RH and IN has previously been noticed for HIV-1, suggesting that the local sequence environment may contribute to PR site recognition (22, 24). Analysis of the local environment by the HCA program suggested that the L599-Q600 dipeptide was the most probable cleavage site.

Based on this analysis, we constructed three expression vectors: RT (peptide P158 to N182 of the pro ORF plus peptide P34 to F472 of the pol ORF), RT-RH (RT plus polypeptide S473 to L599), and RT-RH-IN (RT-RH plus polypeptide Q600 to G896). They produced 48-, 59-, and 92-kDa proteins, respectively, when translated in vitro. The size of the 92-kDa protein compares well with that of the 95-kDa viral form described elsewhere (41).

Furthermore, for rapid and easy enzyme purification, expression vectors that produced the same proteins with an NH2-terminal (His)10 tag were also constructed. Le Grice and Grüninger-Leitch reported that addition of such a His tag at the NH2 terminus of the HIV-1 RT had no effect on its activity (22). We did not expect this tag to affect the RT activity either. After in vitro expression, the three proteins were purified to homogeneity on a nickel chromatography support. The RT activity was examined by testing each protein alone or in pairwise combination. Neither RT, RT-RH, nor RT-RH-IN alone displayed significant RT activity. A combination of RT plus RT-RH or RT plus RT-RH-IN proteins had no or low levels of polymerization activity. By contrast, the combination of RT-RH and RT-RH-IN proteins displayed significant RNA-dependent DNA polymerase activity. The level of activity was slightly below that described for other RTs (28, 31). This would signify either that HTLV-1 RT activity is intrinsically low, that most of the enzyme is in an inactive form, or that a negative effect of the added tag cannot be excluded. The fact that the monomers of the different proteins exhibited no or negligible activity was reminiscent of contradictory reports about the level of polymerization activity associated with HIV-1 and HIV-2 p66 and p51 monomers (or homodimers). This activity seemed to be severely reduced for low concentrations of p51 and p66 (1, 6, 16, 33, 40).

Obtainment of RT activity requires the presence of the RT-RH and RT-RH-IN proteins, suggesting a possible association of both monomers. Sucrose gradient sedimentation analyses of a crude mixture of both proteins in a coupled transcription-translation lysate indicate that RT-RH and RT-RH-IN proteins do not heterodimerize but may associate to form oligomers of a higher order. They sedimented in a peak at an approximate molecular mass of 180 to 240 kDa with an RT-RH/RT-RH-IN ratio of 3:1, which favored an α3/β tetrameric structure.

In this experiment and numerous other experiments using purified proteins, RT-RH and RT-RH-IN proteins exhibited a high propensity to precipitate. This characteristic hampered our ability to demonstrate the association of an RT activity with the purified oligomers. It may be possible that the low level of the detected RT activity was due to the fact that most of the proteins were in an aggregated form. The active enzyme would correspond to the 210-kDa oligomer, and the inactive enzyme would correspond to the major part of the protein that is recovered in the aggregated fraction of the gradient.

The results obtained were unexpected, since they revealed that the structure of retroviral RTs is not limited to those previously described but can be more complex, as that of HTLV-1 RT seems to be. Unfortunately, because more-detailed structural studies on active RT required large amounts of pure, nonaggregated proteins, they could not be performed. Nevertheless, the in vitro synthesis system we have developed is the only one available for the screening of potential RT inhibitors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kathryn Mayo and David Hoffman for critically reviewing the English of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the ANRS, the Comité de la Gironde de la Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer, and the Etablissement Public Régional d’Aquitaine. Bernadette Trentin is a recipient of a fellowship from the Comités des Pyrénées-Atlantiques et des Landes de la Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson S F, Coleman J E. Conformational changes of HIV reverse transcriptase subunits on formation of the heterodimer: correlation with kcat and Km. Biochemistry. 1992;31:8221–8228. doi: 10.1021/bi00150a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balakrishnan M, Jonsson C B. Functional identification of nucleotides conferring substrate specificity to retroviral integrase reactions. J Virol. 1997;71:1025–1035. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1025-1035.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barber A M, Hizi A, Maizel J V, Jr, Hughes S H. HIV-1 reverse transcriptase: structure predictions for the polymerase domain. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1990;6:1061–1072. doi: 10.1089/aid.1990.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daenke S, Schramm H J, Bangham C R. Analysis of substrate cleavage by recombinant protease of human T cell leukaemia virus type 1 reveals preferences and specificity of binding. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2233–2239. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-9-2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dayhoff M O, Barker W C, Hunt L T. Establishing homologies in protein sequences. Methods Enzymol. 1983;91:524–545. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(83)91049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deibel M R, Jr, McQuade T J, Brunner D P, Tarpley W G. Denaturation/refolding of purified recombinant HIV reverse transcriptase yields monomeric enzyme with high enzymatic activity. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1990;6:329–340. doi: 10.1089/aid.1990.6.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.di Marzo Veronese F, Copeland T D, DeVico A L, Rahman R, Oroszlan S, Gallo R C, Sarngadharan M G. Characterization of highly immunogenic p66/p51 as the reverse transcriptase of HTLV-III/LAV. Science. 1986;231:1289–1291. doi: 10.1126/science.2418504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farmerie W G, Loeb D D, Casavant N C, Hutchison III C A, Edgell M H, Swanstrom R. Expression and processing of the AIDS virus reverse transcriptase in Escherichia coli. Science. 1987;236:305–308. doi: 10.1126/science.2436298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzgerald P M D, Springer J P. Structure and function of retroviral proteases. Annu Rev Biophys Biophys Chem. 1991;20:299–320. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.20.060191.001503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerard G F, Grandgenett D P. Purification and characterization of the DNA polymerase and RNase H activities in Moloney murine sarcoma-leukemia virus. J Virol. 1975;15:785–797. doi: 10.1128/jvi.15.4.785-797.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golomb M, Grandgenett D P. Endonuclease activity of purified RNA-directed DNA polymerase from avian myeloblastosis virus. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:1606–1613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatanaka M, Nam S H. Identification of HTLV-I gag protease and its sequential processing of the gag gene product. J Cell Biochem. 1989;40:15–30. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240400103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatfield D L, Levin J G, Rein A, Oroszlan S. Translational suppression in retroviral gene expression. Adv Virus Res. 1992;41:193–239. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60037-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins D G, Sharp P M. CLUSTAL: a package for performing multiple sequence alignment on a microcomputer. Gene. 1988;73:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinuma Y, Nagata K, Hanaoka M, Nakai M, Matsumoto T, Kinoshita K I, Shirakawa S, Miyoshi I. Adult T-cell leukemia: antigen in an ATL cell line and detection of antibodies to the antigen in human sera. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:6476–6480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hizi A, McGill C, Hughes S H. Expression of soluble, enzymatically active, human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase in Escherichia coli and analysis of mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1218–1222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacks T. Translational suppression in gene expression in retroviruses and retrotransposons. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;157:93–124. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-75218-6_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson M S, McClure M A, Feng D F, Gray J, Doolittle R F. Computer analysis of retroviral pol genes: assignment of enzymatic functions to specific sequences and homologies with nonviral enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:7648–7652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.20.7648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobayashi M, Ohi Y, Asano T, Hayakawa T, Kato K, Kakinuma A, Hatanaka M. Purification and characterization of human T-cell leukemia virus type I protease produced in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1991;293:106–110. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kozak M. Compilation and analysis of sequences upstream from the translational start site in eukaryotic mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:857–872. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.2.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le Grice S F, Grüninger-Leitch F. Rapid purification of homodimer and heterodimer HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by metal chelate affinity chromatography. Eur J Biochem. 1990;187:307–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemesle-Varloot L, Henrissat B, Gaboriaud C, Bissery V, Morgat A, Mornon J P. Hydrophobic cluster analysis: procedures to derive structural and functional information from 2-D representation of protein sequences. Biochimie. 1990;72:555–574. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(90)90120-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leuthardt A, Le Grice S F. Biosynthesis and analysis of a genetically engineered HIV-1 reverse transcriptase/endonuclease polyprotein in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1988;68:35–42. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90596-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lightfoote M M, Coligan J E, Folks T M, Fauci A S, Martin M A, Venkatesan S. Structural characterization of reverse transcriptase and endonuclease polypeptides of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome retrovirus. J Virol. 1986;60:771–775. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.2.771-775.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Löchelt M, Flügel R M. The human foamy virus pol gene is expressed as a Pro-Pol polyprotein and not as a Gag-Pol fusion protein. J Virol. 1996;70:1033–1040. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1033-1040.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mador N, Panet A, Honigman A. Translation of gag, pro, and pol gene products of human T-cell leukemia virus type 2. J Virol. 1989;63:2400–2404. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.2400-2404.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Majumdar C, Abbotts J, Broder S, Wilson S H. Studies on the mechanism of human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase. Steady-state kinetics, processivity, and polynucleotide inhibition. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:15657–15665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mamoun R Z, Dye D, Rebeyrotte N, Bouamr F, Cerutti M, Desgranges C. Mouse monoclonal antibodies directed against the HTLV-I protease recognize epitopes internal to the dimer. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1997;14:184–188. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199702010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menard A, Mamoun R Z, Geoffre S, Castroviejo M, Raymond S, Precigoux G, Hospital M, Guillemain B. Bovine leukemia virus: purification and characterization of the aspartic protease. Virology. 1993;193:680–689. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mizrahi V, Lazarus G M, Miles L M, Meyers C A, Debouck C. Recombinant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase: purification, primary structure, and polymerase/ribonuclease H activities. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1989;273:347–358. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90493-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mori K, Sabe H, Siomi H, Iino T, Tanaka A, Takeuchi K, Hirayoshi K, Hatanaka M. Expression of a provirus of human T cell leukaemia virus type I by DNA transfection. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:499–506. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-2-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muller B, Restle T, Weiss S, Gautel M, Sczakiel G, Goody R S. Co-expression of the subunits of the heterodimer of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:13975–13978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nam S H, Copeland T D, Hatanaka M, Oroszlan S. Characterization of ribosomal frameshifting for expression of pol gene products of human T-cell leukemia virus type I. J Virol. 1993;67:196–203. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.196-203.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nam S H, Kidokoro M, Shida H, Hatanaka M. Processing of gag precursor polyprotein of human T-cell leukemia virus type I by virus-encoded protease. J Virol. 1988;62:3718–3728. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.10.3718-3728.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oroszlan S, Copeland T D. Primary structure and processing of gag and env gene products of human T-cell leukemia viruses HTLV-ICR and HTLV-IATK. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1985;115:221–233. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-70113-9_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poiesz B J, Ruscetti F W, Gazdar A F, Bunn P A, Minna J D, Gallo R C. Detection and isolation of type C retrovirus particles from fresh and cultured lymphocytes of a patient with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:7415–7419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poiesz B J, Ruscetti F W, Reitz M S, Kalyanaraman V S, Gallo R C. Isolation of a new type C retrovirus (HTLV) in primary uncultured cells of a patient with Sezary T-cell leukaemia. Nature. 1981;294:268–271. doi: 10.1038/294268a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ratner L, Haseltine W, Patarca R, Livak K J, Starcich B, Josephs S F, Doran E R, Rafalski J A, Whitehorn E A, Baumeister K. Complete nucleotide sequence of the AIDS virus, HTLV-III. Nature. 1985;313:277–284. doi: 10.1038/313277a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Restle T, Muller B, Goody R S. Dimerization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. A target for chemotherapeutic intervention. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:8986–8988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rho H M, Poiesz B, Ruscetti F W, Gallo R C. Characterization of the reverse transcriptase from a new retrovirus (HTLV) produced by a human cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cell line. Virology. 1981;112:355–360. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90642-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sagata N, Yasunaga T, Tsuzuku-Kawamura J, Ohishi K, Ogawa Y, Ikawa Y. Complete nucleotide sequence of the genome of bovine leukemia virus: its evolutionary relationship to other retroviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:677–681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.3.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwartz D E, Tizard R, Gilbert W. Nucleotide sequence of Rous sarcoma virus. Cell. 1983;32:853–869. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seiki M, Hattori S, Hirayama Y, Yoshida M. Human adult T-cell leukemia virus: complete nucleotide sequence of the provirus genome integrated in leukemia cell DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:3618–3622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.12.3618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shimotohno K, Takahashi Y, Shimizu N, Gojobori T, Golde D W, Chen I S, Miwa M, Sugimura T. Complete nucleotide sequence of an infectious clone of human T-cell leukemia virus type II: an open reading frame for the protease gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:3101–3105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shinnick T M, Lerner R A, Sutcliffe J G. Nucleotide sequence of Moloney murine leukaemia virus. Nature. 1981;293:543–548. doi: 10.1038/293543a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verma I M. Studies on reverse transcriptase of RNA tumor viruses. III. Properties of purified Moloney murine leukemia virus DNA polymerase and associated RNase H. J Virol. 1975;15:843–854. doi: 10.1128/jvi.15.4.843-854.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshida M, Miyoshi I, Hinuma Y. Isolation and characterization of retrovirus from cell lines of human adult T-cell leukemia and its implication in the disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:2031–2035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]