Abstract

Background

Renal colic is acute pain caused by urinary stones. The prevalence of urinary stones is between 10% and 15% in the United States, making renal colic one of the common reasons for urgent urological care. The pain is usually severe and the first step in the management is adequate analgesia. Many different classes of medications have been used in this regard including non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs and narcotics.

Objectives

The aim of this review was to assess benefits and harms of different NSAIDs and non‐opioids in the treatment of adult patients with acute renal colic and if possible to determine which medication (or class of medications) are more appropriate for this purpose. Clinically relevant outcomes such as efficacy of pain relief, time to pain relief, recurrence of pain, need for rescue medication and side effects were explored.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Renal Group's Specialised Register (to 27 November 2014) through contact with the Trials' Search Co‐ordinator using search terms relevant to this review.

Selection criteria

Only randomised or quasi randomised studies were included. Other inclusion criteria included adult patients with a clinical diagnosis of renal colic due to urolithiasis, at least one treatment arm included a non‐narcotic analgesic compared to placebo or another non‐narcotic drug, and reporting of pain outcome or medication adverse effect. Patient‐rated pain by a validated tool, time to relief, need for rescue medication and pain recurrence constituted the outcomes of interest. Any adverse effects (minor or major) reported in the studies were included.

Data collection and analysis

Abstracts were reviewed by at least two authors independently. Papers meeting the inclusion criteria were fully reviewed and relevant data were recorded in a standardized Cochrane Renal Group data collection form. For dichotomous outcomes relative risks and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. For continuous outcomes the weighted mean difference was estimated. Both fixed and random models were used for meta‐analysis. We assessed the analgesic effects using four different outcome variables: patient‐reported pain relief using a visual analogue scale (VAS); proportion of patients with at least 50% reduction in pain; need for rescue medication; and pain recurrence. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I² test.

Main results

A total of 50 studies (5734 participants) were included in this review and 37 studies (4483 participants) contributed to our meta‐analyses. Selection bias was low in 34% of the studies or unclear in 66%; performance bias was low in 74%, high in 14% and unclear in 12%; attrition bias was low in 82% and high in 18%; selective reporting bias low in 92% of the studies; and other biases (industry funding) was high in 4%, unclear in 18% and low in 78%.

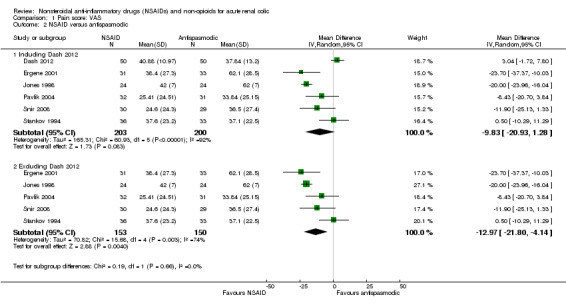

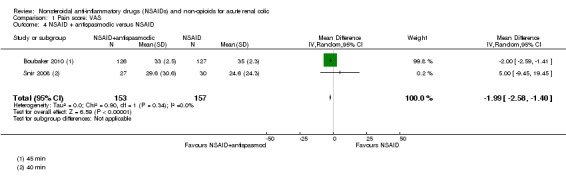

Patient‐reported pain (VAS) results varied widely with high heterogeneity observed. For those comparisons which could be pooled we observed the following: NSAIDs significantly reduced pain compared to antispasmodics (5 studies, 303 participants: MD ‐12.97, 95% CI ‐21.80 to ‐ 4.14; I² = 74%) and combination therapy of NSAIDs plus antispasmodics was significantly more effective in pain control than NSAID alone (2 studies, 310 participants: MD ‐1.99, 95% CI ‐2.58 to ‐1.40; I² = 0%).

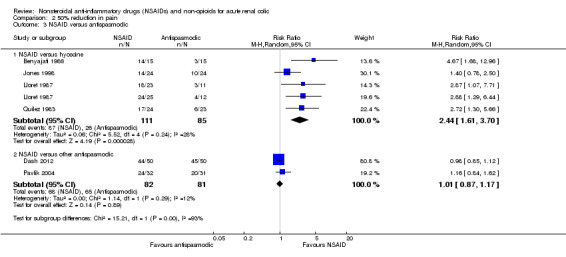

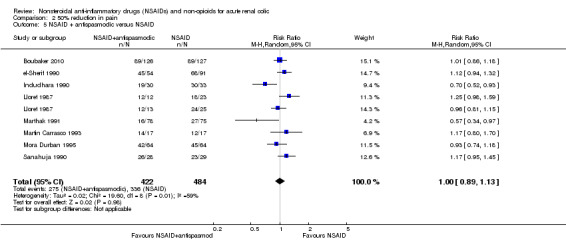

NSAIDs were significantly more effective than placebo in reducing pain by 50% within the first hour (3 studies, 197 participants: RR 2.28, 95% CI 1.47 to 3.51; I² = 15%). Indomethacin was found to be less effective than other NSAIDs (4 studies, 412 participants: RR 1.27, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.60; I² = 55%). NSAIDs were significantly more effective than hyoscine in pain reduction (5 comparisons, 196 participants: RR 2.44, 95% CI 1.61 to 3.70; I² = 28%). The combination of NSAIDs and antispasmodics was not superior to NSAIDs only (9 comparisons, 906 participants: RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.13; I² = 59%). The results were mixed when NSAIDs were compared to other non‐opioid medications.

When the need for rescue medication was evaluated, Patients receiving NSAIDs were significantly less likely to require rescue medicine than those receiving placebo (4 comparisons, 180 participants: RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.60; I² = 24%) and NSAIDs were more effective than antispasmodics (4 studies, 299 participants: RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.84; I² = 65%). Combination of NSAIDs and antispasmodics was not superior to NSAIDs (7 comparisons, 589 participants: RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.57; I² = 10%). Indomethacin was less effective than other NSAIDs (4 studies, 517 participants: RR 1.36, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.94; I² = 14%) except for lysine acetyl salicylate (RR 0.15, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.65).

Pain recurrence was reported by only three studies which could not be pooled: a higher proportion of patients treated with 75 mg diclofenac (IM) showed pain recurrence in the first 24 hours of follow‐up compared to those treated with 40 mg piroxicam (IM) (60 participants: RR 0.05, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.81); no significant difference in pain recurrence at 72 hours was observed between piroxicam plus phloroglucinol and piroxicam plus placebo groups (253 participants: RR 2.52, 95% CI 0.15 to12.75); and there was no significant difference in pain recurrence within 72 hours of discharge between IM piroxicam and IV paracetamol (82 participants: RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.54).

Side effects were presented inconsistently, but no major events were reported.

Authors' conclusions

Although due to variability in studies (inclusion criteria, outcome variables and interventions) and the evidence is not of highest quality, we still believe that NSAIDs are an effective treatment for renal colic when compared to placebo or antispasmodics. The addition of antispasmodics to NSAIDS does not result in better pain control. Data on other types of non‐opioid, non‐NSAID medication was scarce.

Major adverse effects are not reported in the literature for the use of NSAIDs for treatment of renal colic.

Keywords: Humans; Acute Disease; Analgesics, Non‐Narcotic; Analgesics, Non‐Narcotic/therapeutic use; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal/therapeutic use; Diclofenac; Diclofenac/therapeutic use; Indomethacin; Indomethacin/therapeutic use; Parasympatholytics; Parasympatholytics/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Renal Colic; Renal Colic/drug therapy; Scopolamine; Scopolamine/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs are effective treatment for acute renal colic

Acute renal colic is the pain caused by the blockage of urine flow secondary to urinary stones. The prevalence of kidney stone is thought to be between 2% to 3%, and the incidence has been increasing in recent years due to changes in diet and lifestyle. The renal colic pain is usually a sudden intense pain located in the flank or abdominal areas. This usually happens when a urinary stone blocks the ureter (the tube connecting the kidneys to the bladder). Different types of pain killers are used to ease the discomfort. Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and antispasmodics (treatment that suppresses muscle spasms) are used commonly to relieve pain and discomfort. This review aimed to assess the effectiveness of commonly used non‐opioid pain killers in adult patients with acute renal colic pain. Fifty studies enrolling 5734 participants were included in this review. Treatments varied greatly and combining of studies was difficult. We found that overall NSAIDs were more effective than other non‐opioid pain killers including antispasmodics for pain reduction and need for additional medication. We also found that the combining NSAIDs with antispasmodics did not increase the efficacy. No serious adverse effects were reported by any of the included studies.

Background

Description of the condition

Renal or ureteric colic is a symptom complex that is characteristic for the presence of obstructing urinary tract calculi. Urolithiasis is a relatively common disease and its incidence and prevalence is increasing worldwide due to lifestyle and dietary factors. The prevalence of urolithiasis is estimated at between 10% and 15% in the United States (Pearle 2012). Caucasian males are more likely to develop urinary calculi (Menon 2002).The symptoms include flank or abdominal pain radiating to the groin or genitalia. The central factors in the pathogenesis of renal colic are obstruction of the urinary flow and increased pressure proximal to the point of blockage. The increasing pressure stimulates the synthesis and release of prostaglandins. Prostaglandins promote vasodilation and increased urine output leading to higher pressure inside the collecting system. Renal colic pain is typically intense. Nausea and vomiting are common. Although most calculi pass spontaneously and do not need surgical intervention, during this period patients may suffer from severe pain. Therefore, satisfactory analgesia is of paramount importance in their management.

Description of the intervention

A wide range of drugs (opioids and non‐opioids) are used to treat pain and discomfort in patients with acute renal colic. The non‐opioid drugs include but not limited to: NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti‐ inflammatory drugs), antispasmodics, acetaminophen, calcium channel blockers and desmopressin. NSAIDs are commonly used as standard analgesics and opioids are used as rescue medications for acute renal colic. These two groups of medications have been compared in a previous review (Holdgate 2005a). In this present study we compared the analgesic effects of non‐opioids for acute renal colic. NSAIDs mainly work by inhibiting the cyclooxygenase enzyme which induces a subsequent inhibition in prostaglandin synthesis (Vane 1971). Antispasmodic medications are sometimes used alone or in combination with other analgesics for treatment of acute renal colic and work by inducing smooth muscle relaxation in urinary tract. Acetaminophen which is a non‐salicylate with weak anti‐inflammatory potency is thought to work by inhibition of a third isoform of cyclooxygenase (COX‐3) (Chandrasekharan 2002).

How the intervention might work

During the initial phase of obstruction glomerular vasodilation leads to increase urine output and further increase in intra‐ureteral pressure. This in turn results in prostaglandin synthesis in the ureteral wall, contraction of smooth muscle and further pain. Thus, pain control may be aimed at inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis (prostaglandin inhibitors or non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)), reducing spastic ureteral contraction (antispasmodics) or diminishing the pain by intervening at the level of central nervous system (opioids) (Gulmi 2002).

Why it is important to do this review

A plethora of NSAIDs has been used for renal colic, belonging to different classes. In a systematic review by Holdgate 2005a, NSAIDs and opioids were both effective in the management of renal colic but there was higher risk of nausea and vomiting with opioids. There is no systematic review of the efficacy and side effects of these different agents or classes. In addition NSAIDs have not been compared to other non‐opioid medications in terms of their efficacy and side effect profiles.

Objectives

The aim of this review was to assess benefits and harms of different NSAIDs and non‐opioids in the treatment of adult patients with acute renal colic and if possible to determine which medication (or class of medications) are more appropriate for this purpose. Clinically relevant outcomes such as efficacy of pain relief, time to pain relief, recurrence of pain, need for rescue medication and side effects were explored.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods) looking at the effect of NSAIDs and non‐opioids (including calcium channel blockers and desmopressin) in the management of acute renal colic were included. The first period of randomised cross‐over studies were also be included.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

Adults (> 16 years) with acute onset (< 48 hours) of clinically diagnosed renal colic due to urinary stones requiring treatment for pain.

Types of interventions

NSAIDs versus placebo

NSAID versus NSAID

NSAIDs versus non‐opioids (e.g. antispasmodics)

Non‐opioids (other than NSAIDs) versus placebo

Non‐opioid versus non‐opioid (other than NSAIDs)

Any dosage, frequency, duration and route of administration were included.

Types of outcome measures

Studies with at least one of the following outcomes were included.

Patient rated pain by a validated tool

Time to relief

Need for rescue medication

Pain recurrence

Major adverse event (e.g. gastrointestinal bleed, kidney dysfunction)

Minor adverse event (e.g. gastrointestinal disturbances, dizziness)

Exclusion criteria

Patients who had any contraindications to NSAIDs or other non‐opioid drugs were excluded

Any interventions including opioids

Incomplete data precluding calculation or estimation of effect size.

Primary outcomes

-

The primary objective of this review was to explore the analgesic efficacy of non‐opioids medications commonly used to treat acute renal colic. The degree of pain relief achieved by study medications was explored and when possible different analgesics were compared. Therefore the primary outcome were:

Change in pain scores within the first hour

Proportion of patients with significant pain relief (see below)

Proportion of patients who needed rescue medication (opioids, another type of analgesic medications or a second dose of the same study treatment) within 6 hours observation period

Rate of pain recurrence

Secondary outcomes

Medication side effects were explored as a secondary outcome.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Renal Group's Specialised Register (to 27 November 2014) through contact with the Trials' Search Co‐ordinator using search terms relevant to this review. The Cochrane Renal Group’s Specialised Register contains studies identified from the following sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials CENTRAL

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Handsearching of renal‐related journals & the proceedings of major renal conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected renal‐journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal & ClinicalTrials.gov

Studies contained in the Specialised Register are identified through search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of the Cochrane Renal Group. Details of these strategies as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts are available in the 'Specialised Register' section of information about the Cochrane Renal Group.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of nephrology, urology and emergency medicine textbooks, review articles and relevant trials.

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete trials to investigators known to be involved in previous trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The search strategy described was used to obtain titles and abstracts of studies that may be relevant to the review. The titles and abstracts was screened independently by two authors, who discarded studies that were not applicable, however studies and reviews that included relevant data or information on trials were retained initially. Two authors independently assessed retrieved abstracts and, if necessary the full text, of these studies to determine which studies satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was carried out by the same reviewers independently using standard data extraction forms. Studies reported in non‐English language journals were translated before assessment. Where more than one publication of one trial existed, only the publication with the most complete data was included. Disagreements were resolved in consultation with a third author.

Two authors independently carried out data abstraction and quality assessments. Again, a consensus meeting was held with all authors to agree on the assessments for each included study.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were independently assessed by two authors using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (seeAppendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

We also used funnel plots to assess publication bias, whenever the number of included studies allowed.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes results were expressed as relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Data was pooled using the random effects model. Where continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of treatment (patient‐rated pain scores, time to pain relief), the mean difference (MD) was used. When different scales were used and adequate data was not available to calculate standardized mean difference, we classified the findings into two categories: reduction in pain score more than 50% and less than 50%. Need for rescue medication and pain recurrence were treated as dichotomous outcomes.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was analysed using a Chi² test on N‐1 degrees of freedom, with an alpha of 0.05 used for statistical significance and with the I² test (Higgins 2003). I² values of 25%, 50% and 75% correspond to low, medium and high levels of heterogeneity. Heterogeneity among participants could be related to age and the pathology (e.g. size and location of stone). Heterogeneity in treatments could be related to prior agent(s) used and the agent, mode of administration dose and duration of therapy. Variability in timing of post intervention assessment is another source of heterogeneity.

Data synthesis

VAS‐100 mm (Visual Analogue Scale), VAS‐10 cm, or total pain relief at the beginning of the study and at different time points during the study periods were collected. When the number or proportion of patients with at least 50% pain relief (dichotomous data) were available this was extracted. TOTPAR (total pain relief) or SPID (summed pain intensity difference) at the enrolment at and over 15 to 30 minutes, one to two hours, and six hours or sufficient data to allow their calculation were extracted.

A global rating of the effect of a single dose of study medication was extracted when no other information was available. Patient's global evaluation using a standard 3‐point scale (no relief, partial relief, complete relief) or 2‐point scale (complete to moderate relief, mild or no pain relief) was collected, and dichotomous information was extracted for each category. Information from the top two categories of the patient global rating has been shown to produce very similar estimates of analgesic efficacy to information from standard pain relief and pain intensity measurement scales (Collins 2001). Data on complete pain relief in 3‐point scale and complete or to moderate relief in the 2‐point scale was used for the purpose of this analysis. Weighted means (by inverse of variance) were calculated.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was conducted to compare NSAIDs to non‐NSAIDs, placebo, antispasmodics, and a combination of antispasmodics and NSAIDs. We also conducted subgroup analysis to compare different NSAIDs when adequate data was available.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

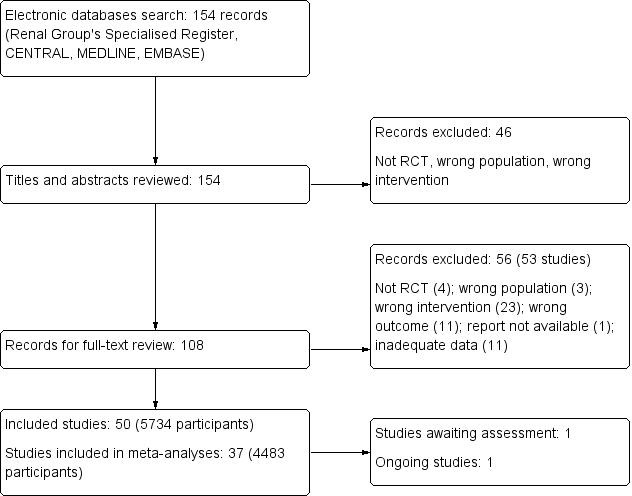

The initial review of the literature revealed 108 relevant records of which 56 (53 studies) were excluded upon further review. One study is awaiting classification (Tanko 1996) and there is one ongoing study (NCT01543165) (Figure 1). A total of 50 studies (5734 participants) were included in this review and 37 studies (4483 participants) contributed to our meta‐analyses.

1.

Flow chart showing study selection procedure

Included studies

Twenty three studies assessed intramuscular (IM) NSAIDs, given alone or in combination with other treatments and provided uncontaminated single dose data (Al Waili 1999; Arnau 1991; Boubaker 2010; Cohen 1998; Dash 2012; Ergene 2001; Fraga 2003; Grissa 2011; Kumar 2011; Laerum 1996; Lopes 2001; Lundstam 1980; Lupi 1986; Marthak 1991; Miralles 1987; Mora Durban 1995; Quilez 1983; Sanahuja 1990; Snir 2008; Stein 1996; Sanchez‐Carpena 2007; Vignoni 1983; Walden 1993).

Eighteen studies assessed intravenous (IV) NSAIDs, given alone or in combination with other treatments and provided uncontaminated single dose data (al‐Sahlawi 1996; Benyajati 1986; el‐Sherif 1990; Galassi 1983; Glina 2011; Holmlund 1978; Jones 1998, Kekec 2000; Lehtonen 1983; Lloret 1987; Magrini 1984; Martin Carrasco 1993; Muriel 1993; Muriel‐Villoria 1995; Pavlik 2004; Pellegrino 1999; Sanchez‐Carpena 2003; Stankov 1994).

One study (Supervia 1998) assessed mucosal (sublingual) NSAIDs, given alone or in combination with other treatments and provided uncontaminated single dose data.

One study compared the oral effect of diclofenac (150 mg) to baralgan (Indudhara 1990), and one study compared oral diclofenac plus antispasmodics with oral baralgan (Chaudhary 1999).

In one study a bolus followed by continuous infusion of glucagon was compared with a placebo (Bahn Zobbe 1986).

Three studies assessed antispasmodics. Miano 1986 compare IV tyropramide with butylscopolamine; Romics 2003 compared IV drotaverine to placebo; and Iguchi 2002 compared butylscopolamine with local lidocaine.

One study (Kheirollahi 2010) compared intramuscular hyoscine‐N‐butylbromide given alone or in combination with intranasal desmopressin.

A number of studies allowed patients to receive a second dose of the medication within the observation period (e.g. after 30 minutes if adequate pain relief was not achieved). For these studies we extracted single dose information collected before the second dose was given.

Four studies reported 4‐point VAS scores (Cohen 1998; Martin Carrasco 1993; Sanchez‐Carpena 2003; Stein 1996); 18 studies reported mean (SD) VAS‐10 (cm) scores (Al Waili 1999; Arnau 1991; Benyajati 1986; el‐Sherif 1990; Ergene 2001; Galassi 1983; Kheirollahi 2010; Laerum 1996; Lopes 2001; Magrini 1984; Marthak 1991; Muriel‐Villoria 1995; Pavlik 2004; Pellegrino 1999; Sanahuja 1990; Stankov 1994; Snir 2008; Supervia 1998).

Eighteen studies reported mean (SD) VAS‐100 (mm) before or after treatment or both (Boubaker 2010; Chaudhary 1999; Dash 2012; Fraga 2003; Glina 2011; Grissa 2011; Iguchi 2002; Jones 1998; Kekec 2000; Kheirollahi 2010; Kumar 2011; Lloret 1987; Lundstam 1980; Martin Carrasco 1993; Miralles 1987; Romics 2003; Sanchez‐Carpena 2007; Vignoni 1983). Walden 1993 reported median (95% CI) VAS‐100. Lupi 1986 used Analogue Chromatic Continuous Scale (ACCS) for evaluating pain intensity and also reported the proportion of patients with a 50% pain reduction.

Indudhara 1990 used the 5‐point verbal rating scale (VRS‐5) and Miano 1986 used the Keele‐Dundee scale.

It was not possible to calculate a pooled estimate of improvement in VAS score of participants in treatment groups because of inconsistency in reporting the data among studies. The time to assess patients varied from five minutes to several hours. To overcome this problem we only assessed and combined data for pain control within the first 60 minutes. This timing was uniformly reported and is clinically more relevant in the treatment of an acute pain. Eleven studies used an ordinal outcome measure (al‐Sahlawi 1996; Bahn Zobbe 1986; el‐Sherif 1990; Indudhara 1990; Kheirollahi 2010; Lehtonen 1983; Lloret 1987; Marthak 1991; Mora Durban 1995; Quilez 1983; Sanahuja 1990) and two studies had a binary outcome (Benyajati 1986; Holmlund 1978).

Excluded studies

We were not able to locate one study (Al‐Faddagh 1996); Wandschneider 1973 assessed the effect of NSAIDs in urologic procedures; three studies (Altay 2007;Ho 2004; Nissen1990) assessed the same type of NSAIDs that were used by different routes in study arms; and eight studies did not provide adequate data (Bilora 2000; Breijo 2007; Catano 2004; Julian 1992; Pardo 1984; Phillips 2009; Roshani 2010; Timbal 1981). Four studies were not randomised (Al‐Obadi 1997; Basar 1991; El‐Sherif 1995; Ruiz 1988); sample size was very small (4) in one study (Godoy 2000); and medications were used as prophylaxis not treatment in one study (Cole 1989). The outcome of interest was stone expulsion in eight studies (Bach 1983; Dellabella 2003; Dellabella 2005; Engelstein 1992; Porpiglia 2000; Porpiglia 2004; Muller 1990; Yilmaz 2005). In 18 studies narcotics were used (Bergus 1996; Cordell 1996; Curry 1995; Elliott 1979; Hazhir 2010; Henry 1987; Kapoor 1989; Khalifa 1986; Lishner 1985; Lundstam 1982; Muller 1990; NCT00646061; NCT01339624; Oosterlinck 1982; Persson 1985; Primus 1989; Soleimanpour 2012; Viksmoen 1986). Reported data for three studies could not be used in the analysis (Galassi 1985; Grenabo 1984; Mortelmans 2006). Mortelmans 2006 evaluated the effect of antispasmodics to placebo and Yencilek 2008 compared IV papaverine to IV hyoscine‐N‐butylbromide; however all the patients received NSAIDs and antispasmodics at the beginning of the study. In Holdgate 2005 all participants received narcotics. One study was excluded for inappropriate use of VAS (Sala‐Mateus 1989). One study only included patients with recurrent renal colic (Laerum 1995) and one study (Ohkawa 1997) evaluated the outcome before and at one, three and seven days after treatment. One study (Ayan 2013) was excluded as it compared adding an alternative medicine product (aromatherapy with essential rose oil) to the conventional therapy.

Ongoing studies

One study has been completed but as yet there are no published data (NCT01543165).

Studies awaiting classification

One study (Tanko 1996) is awaiting classification as it has yet to be translated.

Risk of bias in included studies

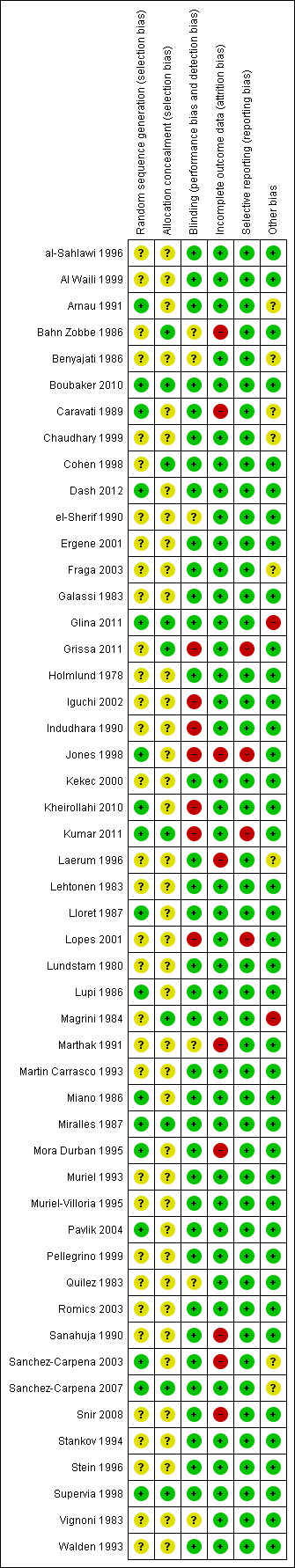

Our risk of bias assessment can be seen in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Sequence generation

Seventeen studies had adequate sequence generation (Arnau 1991; Boubaker 2010; Caravati 1989; Dash 2012; Glina 2011; Jones 1998; Kheirollahi 2010; Kumar 2011; Lloret 1987; Lupi 1986; Miano 1986; Miralles 1987; Mora Durban 1995; Pavlik 2004; Sanchez‐Carpena 2003; Sanchez‐Carpena 2007; Supervia 1998). The sequence generation was unclear in the remaining 33 studies.

Allocation concealment

Allocation concealment was determined to be adequate in only 10 studies (Bahn Zobbe 1986; Boubaker 2010; Cohen 1998; Glina 2011; Grissa 2011; Kumar 2011; Magrini 1984; Miralles 1987; Sanchez‐Carpena 2007; Supervia 1998), allocation concealment was unclear in the remaining 40 studies.

Blinding

Thirty seven studies had adequate blinding (al‐Sahlawi 1996; Al Waili 1999; Arnau 1991; Boubaker 2010; Caravati 1989; Chaudhary 1999; Cohen 1998; Dash 2012; Ergene 2001; Fraga 2003; Galassi 1983; Glina 2011; Holmlund 1978; Kekec 2000; Laerum 1996; Lehtonen 1983; Lloret 1987; Lundstam 1980; Lupi 1986; Magrini 1984; Martin Carrasco 1993; Miano 1986; Miralles 1987; Mora Durban 1995; Muriel 1993; Muriel‐Villoria 1995; Pavlik 2004; Pellegrino 1999; Romics 2003; Sanahuja 1990; Sanchez‐Carpena 2003; Sanchez‐Carpena 2007; Snir 2008; Stankov 1994; Stein 1996; Supervia 1998; Walden 1993). Seven studies were not blinded (Grissa 2011; Iguchi 2002; Indudhara 1990; Jones 1998; Kheirollahi 2010; Kumar 2011; Lopes 2001) and six studies did not provide adequate information so it was unclear whether investigators, participants, or outcome assessors were blinded (Bahn Zobbe 1986; Benyajati 1986; el‐Sherif 1990; Marthak 1991; Quilez 1983; Vignoni 1983).

Incomplete outcome data

Forty one studies had complete outcome data. Risk for attrition bias was high in nine studies (Bahn Zobbe 1986; Caravati 1989; Jones 1998; Laerum 1996; Marthak 1991; Mora Durban 1995; Sanahuja 1990; Sanchez‐Carpena 2003; Snir 2008).

Selective reporting

Forty six studies were free of reporting bias for the primary outcome. The primary outcomes were estimated when the subjects were still in the emergency department. Nevertheless there were issues with incomplete reporting or lack of SD in four studies (Grissa 2011; Jones 1998; Kumar 2011; Lopes 2001).

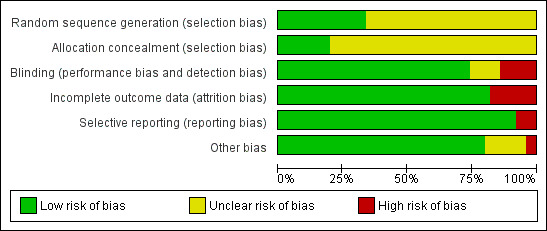

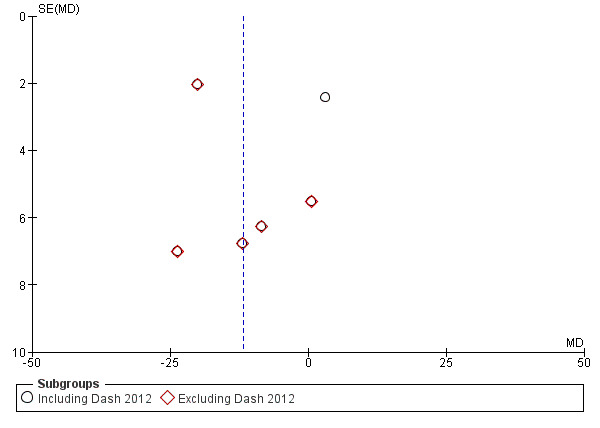

Other potential sources of bias

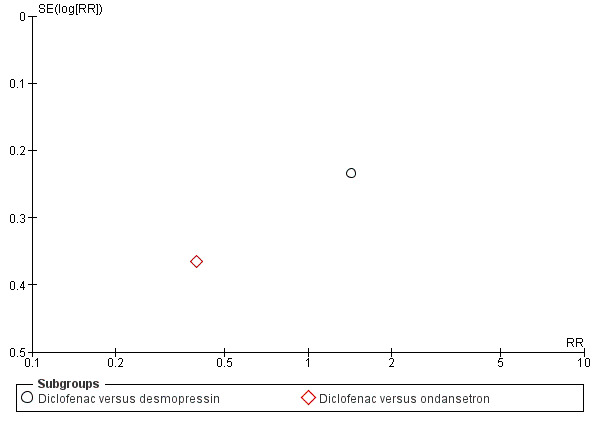

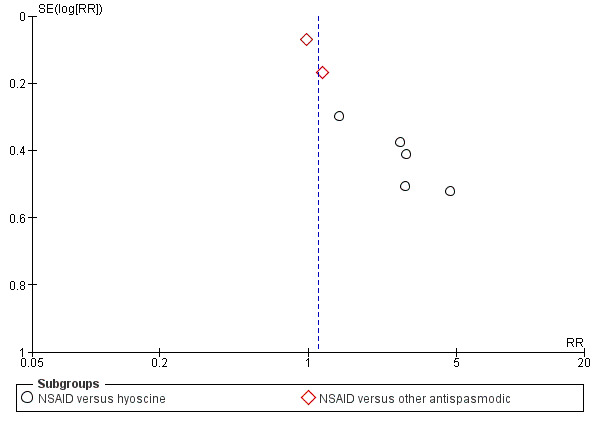

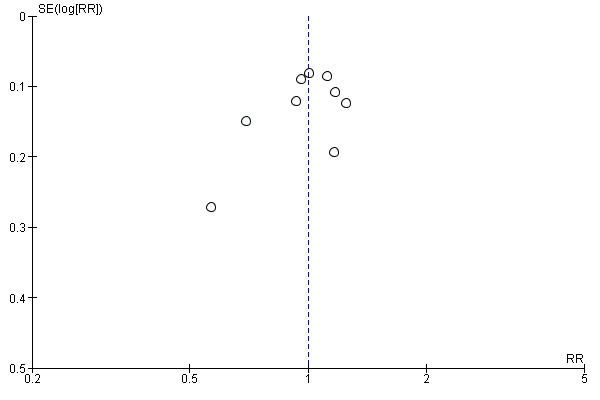

Publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots. It seems both negative and positive studies with small sample size are missing. This is evident in all subgroup analyses (Figure 4; Figure 5; Figure 6; Figure 7). Nine studies which were funded by pharmaceutical industries (Arnau 1991; Benyajati 1986; Caravati 1989; Chaudhary 1999; Fraga 2003; Glina 2011; Laerum 1996; Sanchez‐Carpena 2003; Sanchez‐Carpena 2007) could be considered at risk for bias. Two studies were judge to be at high risk of bias: two authors in Glina 2011 were employees of the funding pharmaceutical company; and the same method of diagnosis was not used in all patients in Magrini 1984. We did not identify any other sources of bias such as extreme imbalance in the groups or stoppage of incomplete study.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Pain score: VAS, outcome: 1.2 NSAID versus antispasmodic.

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 50% reduction in pain, outcome: 2.4 NSAID versus other non‐opioid.

6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 50% reduction in pain, outcome: 2.3 NSAID versus antispasmodic.

7.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 50% reduction in pain, outcome: 2.5 NSAID + antispasmodic versus NSAID.

Effects of interventions

Effects of intervention will be discussed based on the outcome reports in the studies, including changes in VAS, the proportion of patients with at least 50% reduction in pain within the first hour, and need for rescue medication.

Patient‐reported pain score (VAS)

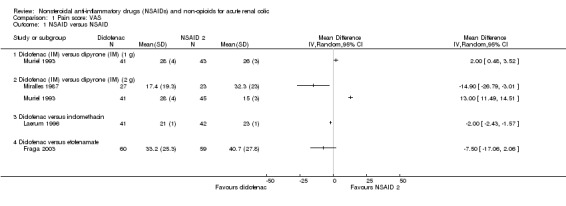

NSAID versus NSAID

Four studies compared NSAID to NSAID, however as the heterogeneity was very high when the studies were pooled (I² = 99%), we have reported the individual study results.

-

Two studies (Miralles 1987; Muriel 1993) compared patient reported VAS in patients taking IM dipyrone or diclofenac and showed opposite effects.

Muriel 1993 reported that dipyrone (both 1g and 2 g doses) was significantly more effective than diclofenac in terms of pain relief in the first 60 minutes of treatment (Analysis 1.1.1 (1 g; 1 study, 84 participants): MD 2.00, 95% CI 0.48 to 3.52), Analysis 1.1.2 (2 g; 1 study, 86 participants): MD 13.00, 95% CI 11.49 to 14.51).

Miralles 1987 reported treatment with diclofenac significantly reduced pain in the first 30 minutes compared to 2 g dipyrone (Analysis 1.1.2 (1 study, 50 participants): MD ‐14.90; 95% CI ‐26.79 to ‐3.01).

Laerum 1996 reported IM diclofenac significantly reduced pain compared to IV indomethacin (Analysis 1.1.3 (1 study, 83 participants): MD ‐2.00, 95% CI ‐2.43 to ‐1.57).

Fraga 2003 found no significant difference in pain reduction between IM diclofenac sodium compared to IM etofenamate (Analysis 1.1.4 (1 study, 119 participants): MD ‐7.50, 95%CI ‐17.06 to 2.06).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain score: VAS, Outcome 1 NSAID versus NSAID.

NSAIDs versus antispasmodic

Six studies compared NSAIDs to antispasmodics and had adequate data to be included in the meta‐analysis (Dash 2012; Ergene 2001; Jones 1998; Pavlik 2004; Snir 2008; Stankov 1994).

Meta‐analysis of these studies showed that NSAIDs were comparable to antispasmodic (Analysis 1.2.1 (6 studies, 403 participants): MD ‐9.83, 95% CI ‐20.93 to 1.28; I² = 92%). There was very significant heterogeneity. The major source of heterogeneity is likely the wide variety of antispasmodics used in the studies. By removing Dash 2012 which used drotaverine as an antispasmodic, heterogeneity was reduced and the result favours NSAIDs over antispasmodics (Analysis 1.2.2 (5 studies, 303 participants): MD ‐12.97, 95% CI ‐21.80 to ‐ 4.14; I² = 74%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain score: VAS, Outcome 2 NSAID versus antispasmodic.

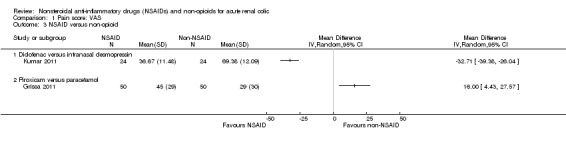

NSAID versus non‐opioid

Two studies compared 40 mg intranasal desmopressin with 75 mg diclofenac (IM) (Kumar 2011; Lopes 2001) and one study compared IM piroxicam to IV paracetamol (Grissa 2011). Due to the high heterogeneity when pooled (I² = 98%) we have reported the individual study results.

Kumar 2011 concluded that diclofenac was significantly more effective than intranasal desmopressin in relieving renal colic pain over period of 30 minutes (Analysis 1.3.1 (1 study, 48 participants): MD ‐32.71, 95% CI ‐39.38 to ‐26.04). Lopes 2001 however concluded that desmopressin was an effective analgesic after 10 minutes; but when compared to diclofenac the effect was less prominent after 30 minutes; SDs were not available from this study and could not be included in the meta‐analysis.

Grissa 2011 reported IV paracetamol was found to be more effective than IM piroxicam (Analysis 1.3.2 (1 study, 100 participants): MD 16.00, 95% CI 4.43 to 27.57).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain score: VAS, Outcome 3 NSAID versus non‐opioid.

NSAID plus antispasmodic versus NSAID alone

Two studies compared the combination of NSAIDs and antispasmodics to NSAIDs alone (Boubaker 2010;Snir 2008).

The combination therapy was significantly more effective in pain control (Analysis 1.4 (2 studies, 310 participants): MD ‐1.99, 95% CI ‐2.58 to ‐1.40; I² = 0%) but the difference in the VAS was not clinically significant (Gallagher 2001; Todd 1996). Boubaker 2010 reported a very small variance in post treatment scores; therefore, the result of the combined analysis has been swayed toward this larger study.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain score: VAS, Outcome 4 NSAID + antispasmodic versus NSAID.

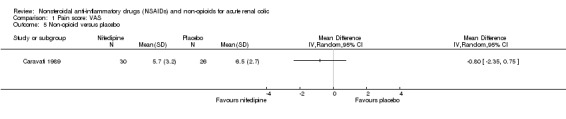

Non‐opioid versus placebo

Caravati 1989 found no significant difference between nifedipine and placebo in pain control using VAS (Analysis 1.5 (1 study, 56 participants): MD ‐0.80, 95% CI ‐2.35 to 0.75).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain score: VAS, Outcome 5 Non‐opioid versus placebo.

Non‐opioid versus non‐opioid

Miano 1986 used Keele‐Dundee Scale with five prefixed degrees to evaluate pain and concluded that IV tiropramide 50 mg was significantly more effective than IV butylscopolamine bromide 20 mg at 60 minutes (P < 0.01).

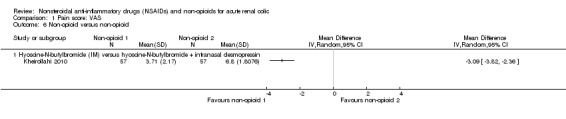

Kheirollahi 2010 compared IM hyoscine‐N‐butylbromide alone and in combination with Intranasal desmopressin showed the combination provided significantly better pain relief at 60 minutes post‐treatment (Analysis 1.6 (1 study, 84 participants): MD ‐3.09, 95% CI ‐‐3.82 to ‐2.36).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain score: VAS, Outcome 6 Non‐opioid versus non‐opioid.

50% reduction in pain

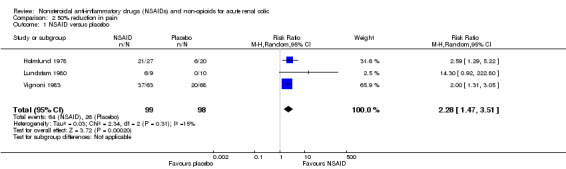

NSAID versus placebo

Three studies compared NSAIDs with placebo (Holmlund 1978;Lundstam 1980;Vignoni 1983). Holmlund 1978 compared IV indomethacin to placebo and Lundstam 1980 and Vignoni 1983 compared IM diclofenac to placebo.

NSAIDs were significantly more effective than placebo in reducing pain by 50% in the first hour (Analysis 2.1 (3 studies, 197 participants): RR 2.28, 95% CI 1.47 to 3.51; I² = 15%).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 50% reduction in pain, Outcome 1 NSAID versus placebo.

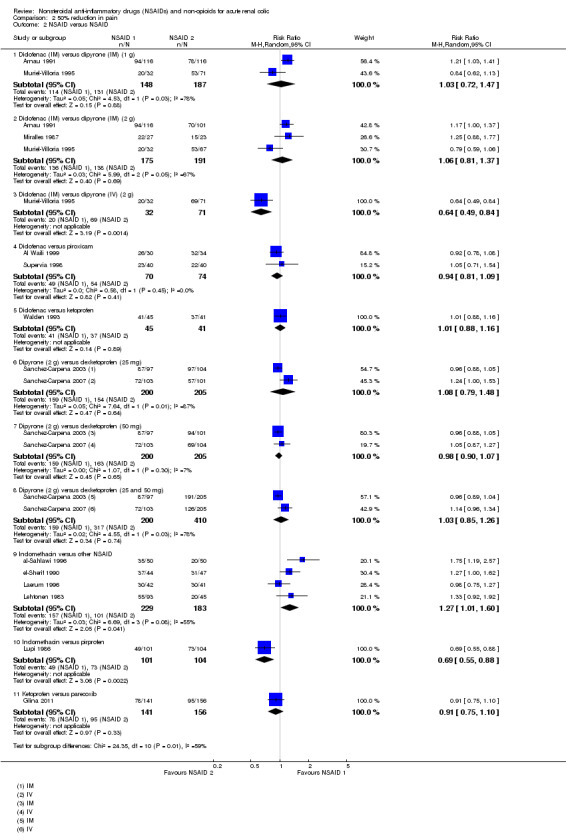

NSAID versus NSAID

Sixteen studies comparing one NSAID to another (al‐Sahlawi 1996; Al Waili 1999; Arnau 1991;Cohen 1998; el‐Sherif 1990; Glina 2011; Laerum 1996; Lehtonen 1983; Lupi 1986; Muriel 1993; Muriel‐Villoria 1995; Stein 1996; Supervia 1998; Sanchez‐Carpena 2003; Sanchez‐Carpena 2007; Walden 1993).

Two studies (Arnau 1991;Muriel‐Villoria 1995) compared 75 mg diclofenac (IM) with 1g dipyrone (IM). There was no significant difference between diclofenac and dipyrone (Analysis 2.2.1 (2 studies, 335 participants): RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.47; I² = 78%).

Three studies (Arnau 1991;Miralles 1987;Muriel‐Villoria 1995) compared 75 mg diclofenac (IM) with 2 g dipyrone (IM). There was no statistically significant difference between diclofenac and dipyrone (Analysis 2.2.2 (3 studies, 366 participants): RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.37; I² = 67%).

Muriel‐Villoria 1995 reported 2 g dipyrone (IV) was superior to 75 mg diclofenac (IM) in terms of pain reduction (Analysis 2.2.3 (1 study, 103 participants): RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.84). The authors also concluded that the analgesic effects of dipyrone appeared faster and lasted longer.

Two studies (Al Waili 1999;Supervia 1998) compared diclofenac to piroxicam. There was no significant difference in 50% pain relief (Analysis 2.2.4 (2 studies, 144 participants): RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.09; I² = 0%).

Walden 1993 reported there was no significance difference observed in pain reduction at 120 minutes post‐treatment between diclofenac and ketoprofen (Analysis 2.4.5 (1 study, 86 participants): RR 1.01, 95% C: 0.88 to 1.16).

-

Two studies compared dipyrone to dexketoprofen (Sanchez‐Carpena 2003; Sanchez‐Carpena 2007). Sanchez‐Carpena 2003 compared 2 g dipyrone (IM) with two different doses of dexketoprofen (25 and 50 mg; IM) and Sanchez‐Carpena 2007 compared the same dose dexketoprofen (IV) with 2 g dipyrone (IV).

There were no significant differences between 2 g dipyrone and 25 mg dexketoprofen (Analysis 2.2.6 (2 studies, 405 participants): RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.48; I² = 87%).

There were no significant differences between 2 g dipyrone and 50 mg dexketoprofen ((Analysis 2.2.7 (2 studies, 405 participants): RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.07; I² = 7%).

Combined, there was no significant difference between dipyrone and dexketoprofen (Analysis 2.2.8 (2 studies, 610 participants): RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.26; I² = 78%).

-

Five studies compared indomethacin with other NSAIDs (al‐Sahlawi 1996; el‐Sherif 1990; Laerum 1996; Lehtonen 1983; Lupi 1986). Overall, indomethacin was found to be comparable to other NSAIDs (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.54), however there was significant heterogeneity (I² = 83%). Subgroup analysis revealed that the source of heterogeneity was Lupi 1986 in which indomethacin (IM) was compared to pirprofen (IM). By removing this study indomethacin was found to be less effective than other NSAIDs (Analysis 2.2.9 (4 studies, 412 participants): RR 1.27, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.60; I² = 55%).

Lupi 1986 reported pirprofen was significantly more effective than indomethacin in reducing pain by 50% (Analysis 2.2.10 (1 study, 205 participants): RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.88).

Glina 2011 reported no significant difference between 40 mg parecoxib (IV) and 100 mg ketoprofen (IV) (Analysis 2.2.11, RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.10).

Two studies compared diclofenac to ketorolac (Cohen 1998;Stein 1996). We were not able to do a meta‐analysis on these studies due to differences in data presentation.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 50% reduction in pain, Outcome 2 NSAID versus NSAID.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 50% reduction in pain, Outcome 4 NSAID versus other non‐opioid.

NSAID versus antispasmodic

Six studies (seven comparisons) (Benyajati 1986; Dash 2012; Jones 1998; Lloret 1987; Pavlik 2004; Quilez 1983) compared NSAIDs to antispasmodics

NSAIDs were more effective than antispasmodics in pain reduction (Analysis 2.3 (7 comparisons, 359 participants): RR 1.89, 95% CI 1.12 to 3.19; I² = 88%). However there was significant heterogeneity. The source of heterogeneity is likely from the different antispasmodics used in the studies. By pooling the four studies that used hyoscine as the antispasmodic (Benyajati 1986; Jones 1998; Lloret 1987; Quilez 1983) the heterogeneity was markedly reduced (I² = 28%). NSAIDs were significantly more effective than hyoscine in pain reduction (Analysis 2.3.1 (5 comparisons, 196 participants): RR 2.44, 95% CI 1.61 to 3.70).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 50% reduction in pain, Outcome 3 NSAID versus antispasmodic.

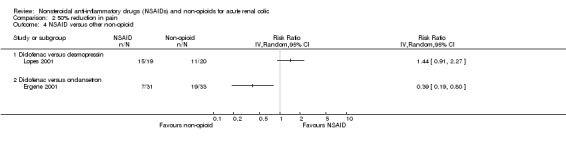

NSAID versus other non‐opioid

Two studies compared an NSAID to another on‐opioid (Ergene 2001; Lopes 2001).

Lopes 2001 reported no significant difference between 75 mg diclofenac (IM) and 40 µg intranasal desmopressin (Analysis 2.4.1 (1 study, 30 participants): RR 1.44, 95% CI 0.91 to 2.27).

Ergene 2001 reported 75 mg diclofenac (IM) was inferior to 8 mg ondansetron (IV) for pain relief (Analysis 2.4.2 (1 study, 64 participants): RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.80).

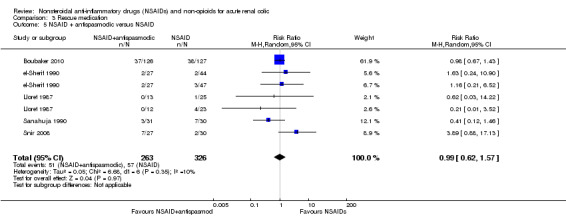

NSAID plus antispasmodic versus NSAID

Eight studies (nine comparisons) compared NSAIDs with combinations of NSAIDs and antispasmodics (Boubaker 2010;el‐Sherif 1990;Indudhara 1990;Lloret 1987;Marthak 1991;Martin Carrasco 1993;, Mora Durban 1995;Sanahuja 1990). There was no significant difference between NSAIDs and combination of NSAIDs and antispasmodics (Analysis 2.5 (9 comparisons, 906 participants): RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.13; I² = 59%).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 50% reduction in pain, Outcome 5 NSAID + antispasmodic versus NSAID.

NSAID plus non‐opioid versus non‐opioid

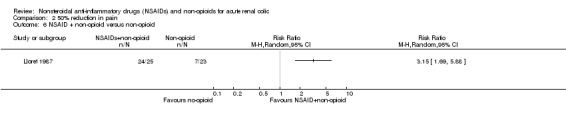

Lloret 1987 reported dipyrone plus hyoscine was more effective than dipyrone alone for pain reduction (Analysis 2.6 (1 study, 48 participants): RR 3.15, 95% CI 1.69 to 5.88).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 50% reduction in pain, Outcome 6 NSAID + non‐opioid versus non‐opioid.

Non‐opioids versus non‐opioids

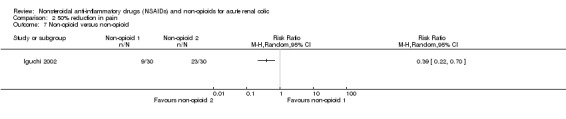

Iguchi 2002 reported IV butylscopolamine was less effective in pain control than lidocaine injection to trigger point for complete pain relief at 30 minutes (Analysis 2.7 (1 study, 60 participants): RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.70).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 50% reduction in pain, Outcome 7 Non‐opioid versus non‐opioid.

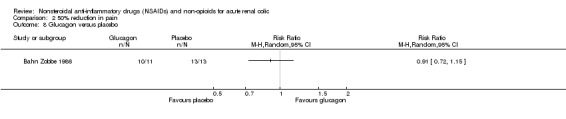

Glucagon versus placebo

Bahn Zobbe 1986 found no significant difference in achieving pain control between a bolus injection of glucagon to placebo (Analysis 2.8 (1 study, 24 participants): RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.15).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 50% reduction in pain, Outcome 8 Glucagon versus placebo.

Need for rescue medication

The need for rescue analgesia was reported in 18 studies comparing different types, doses and routes of administration of NSAIDs (al‐Sahlawi 1996; Al Waili 1999; Arnau 1991; Cohen 1998; el‐Sherif 1990; Fraga 2003; Glina 2011; Laerum 1996; Lehtonen 1983; Lloret 1987; Lupi 1986; Magrini 1984; Muriel‐Villoria 1995; Sanchez‐Carpena 2003; Sanchez‐Carpena 2007; Stein 1996; Supervia 1998; Walden 1993).

Eight studies (Dash 2012; Ergene 2001; Kumar 2011; Lloret 1987; Lopes 2001; Pavlik 2004; Snir 2008; Stankov 1994) which compared NSAIDs (given alone or in combination with other non‐opioids) to non‐opioids reported data on need for rescue analgesics.

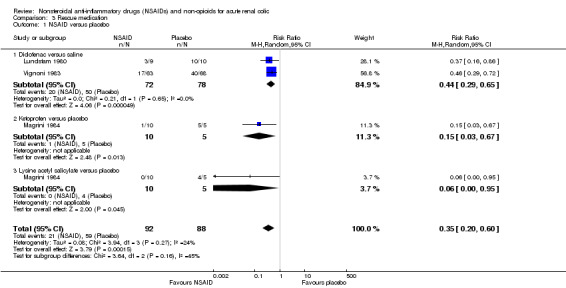

NSAID versus placebo

Three studies (four comparisons) compared NSAIDs with placebo (Lundstam 1980; Magrini 1984; Vignoni 1983).

Patients receiving NSAIDs were significantly less likely to require rescue medicine than those receiving placebo (Analysis 3.1 (4 comparisons, 180 participants): RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.60; I² = 24%).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Rescue medication, Outcome 1 NSAID versus placebo.

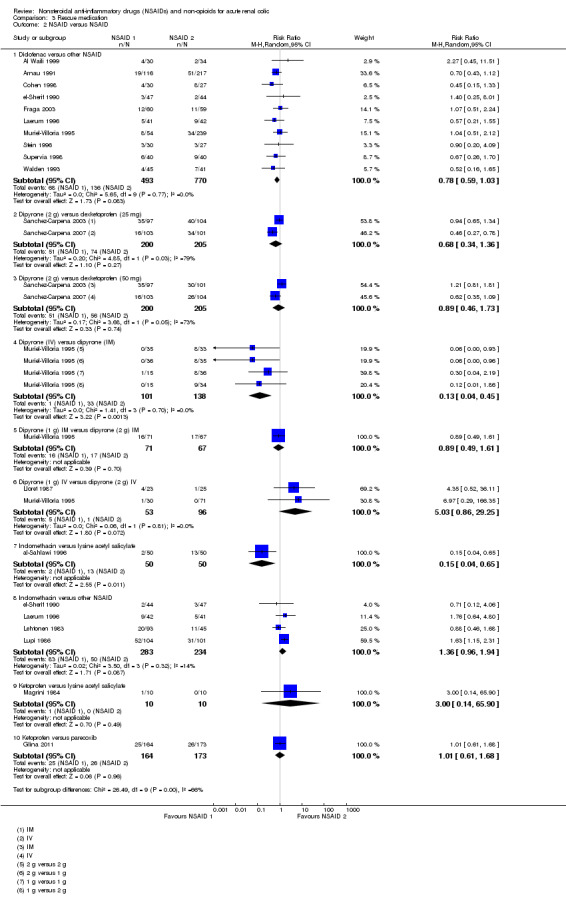

NSAID versus NSAID

Ten studies (Al Waili 1999; Arnau 1991; Cohen 1998; el‐Sherif 1990; Fraga 2003; Laerum 1996; Muriel‐Villoria 1995; Stein 1996; Supervia 1998; Walden 1993) compared diclofenac with other NSAIDs.

Pooled analysis of these studies showed that diclofenac is comparable with other NSAIDs (Analysis 3.2.1 (10 studies, 1263 participants) RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.03; I² = 0%)

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Rescue medication, Outcome 2 NSAID versus NSAID.

Two studies compared 2 g dipyrone (IM or IV) with 25 mg or 50 mg dexketoprofen (IV or IM) (Sanchez‐Carpena 2003; Sanchez‐Carpena 2007).

There was no significant difference in the need for rescue medication between 2 g dipyrone (IM or IV) and either 25 mg dexketoprofen (IM or IV) (Analysis 3.2.2 (2 studies, 405 participants): RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.36; I² = 79%) or 50 mg dexketoprofen (IM or IV) (Analysis 3.2.3 (2 studies, 405 participants): RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.73; I² = 73%).

Two studies compared different doses of dipyrone (Lloret 1987; Muriel‐Villoria 1995). Muriel‐Villoria 1995 compared varying doses of dipyrone delivered either IV or IM and Lloret 1987 compared 1g versus 2 g dipyrone (IV).

IV doses of dipyrone significantly reduced the need for rescue medication compared to IM doses of dipyrone (Analysis 3.2.4 (4 comparisons, 239 participants): RR 0.13, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.45; I² = 0%).

Muriel‐Villoria 1995 reported no difference in the need for rescue medication between 1 g or 2 g dipyrone delivered IM (Analysis 3.2.5 (1 study, 138 participants): RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.61).

There was no significant difference in the need for rescue medication between 1 g and 2 g dipyrone delivered IV (Analysis 3.2.6 (2 studies, 149 participants): RR 5.03, 95% CI 0.86 to 29.25; I² = 0%).

Five studies compared indomethacin with other NSAIDs (al‐Sahlawi 1996; el‐Sherif 1990; Laerum 1996; Lehtonen 1983; Lupi 1986).

al‐Sahlawi 1996 compared 100 mg indomethacin (IV) to 1.8 g lysine acetyl salicylate (IV) and reported a statistically significant reduction in the need for rescue medication in the indomethacin group (Analysis 3.2.7 (1 study, 100 participants): RR 0.15, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.65).

Pooled analysis of the other four studies showed that patients treated with other NSAIDs needed less rescue medication compared to those who received indomethacin, however this result was not significant (Analysis 3.2.8 (4 studies, 517 participants): RR 1.36, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.94; I² = 14%).

Two studies compared ketoprofen to lysine acetyl salicylate (Magrini 1984) and parecoxib (Glina 2011) and found no significant difference in need for rescue medication (Analysis 3.2.9 (1 study, 20 participants): RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.14 to 65.90), (Analysis 3.2.10 (1 study, 337 participants): RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.68).

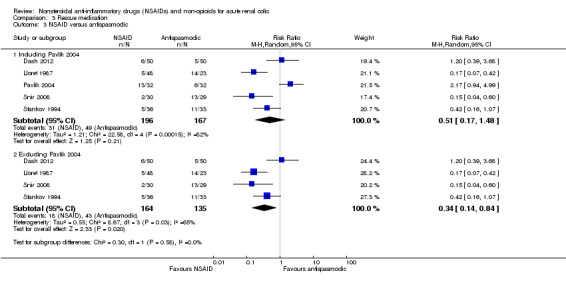

NSAID versus antispasmodic

Five studies which compared NSAIDs to antispasmodics (Dash 2012; Lloret 1987; Pavlik 2004; Snir 2008; Stankov 1994).

There was no significant difference in need for rescue therapy between NSAIDs and antispasmodics (Analysis 3.3.1 (5 studies, 363 participants): RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.48; I² = 82%). There was significant heterogeneity. The major source was Pavlik 2004; when this study was removed the heterogeneity was reduced to 65% and the result indicates that patients treated with NSAIDs were significantly less likely to need rescue therapy (Analysis 3.3.2 (4 studies, 299 participants): RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.84; I² = 65%).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Rescue medication, Outcome 3 NSAID versus antispasmodic.

NSAID versus other non‐opioid

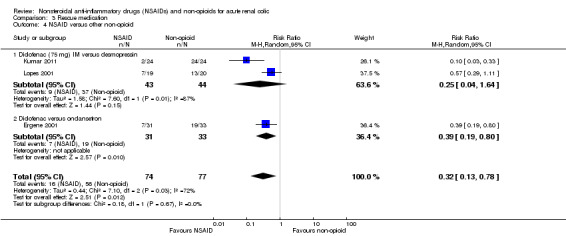

Three studies compared NSAIDs with other non‐opioids; two compared 75 mg diclofenac (IM) to desmopressin (Kumar 2011; Lopes 2001), and one compared diclofenac to ondansetron (Ergene 2001).

Combined there was significantly less need for rescue therapy for the NSAID group compared to other non‐opioids (Analysis 3.4 (3 studies, 151 participants): RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.78; I² = 72%).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Rescue medication, Outcome 4 NSAID versus other non‐opioid.

NSAID plus antispasmodic versus NSAID

Five studies (seven comparisons) compared combination of NSAIDs and antispasmodics versus NSAIDs (Boubaker 2010; el‐Sherif 1990; Lloret 1987; Sanahuja 1990; Snir 2008). There was no significant difference between the two treatment groups (Analysis 3.5 (7 comparisons, 589 participants): RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.57; I² = 10%).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Rescue medication, Outcome 5 NSAID + antispasmodic versus NSAID.

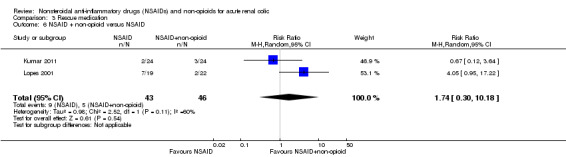

NSAID plus non‐opioid versus NSAID

Two studies compared the effect of 40 mg intranasal desmopressin to 75 mg diclofenac (IM) (Kumar 2011; Lopes 2001). There was no significant difference between the two treatments (Analysis 3.6 (2 studies, 89 participants): RR 1.74, 95% CI 0.30 to 10.18; I² = 60%).

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Rescue medication, Outcome 6 NSAID + non‐opioid versus NSAID.

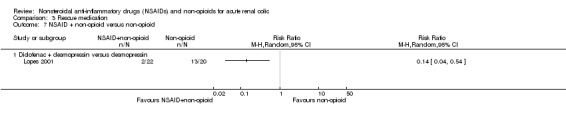

NSAID plus non‐opioid versus non‐opioid

Lopes 2001 compared Diclofenac plus desmopressin versus desmopressin and reported significantly less need for rescue therapy with the combined treatment (Analysis 3.7.1 (1 study, 42 participants): RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.0 to 0.54).

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Rescue medication, Outcome 7 NSAID + non‐opioid versus non‐opioid.

Non‐opioid versus placebo

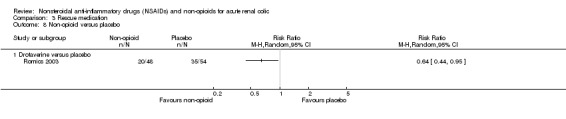

Romics 2003 reported patients receiving drotaverine were significantly less likely to need rescue therapy than those receiving placebo (Analysis 3.8.1 (1 study, 102 participants): RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.95).

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Rescue medication, Outcome 8 Non‐opioid versus placebo.

One cross‐over study (Caravati 1989) which compared oral nifedipine to placebo showed 77% of the patients receiving both nifedipine and placebo needed further rescue medication, however data presented was non‐adequate for further statistical analysis.

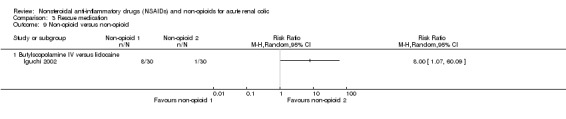

Non‐opioid versus non‐opioid

Iguchi 2002 compared IV butylscopolamine and lidocaine injection to trigger point reported a significantly higher proportion of patients in the butylscopolamine group needed rescue medication (Analysis 3.9.1 (1 study, 60 participants): RR 8.00, 95% CI 1.07 to 60.09).

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Rescue medication, Outcome 9 Non‐opioid versus non‐opioid.

Pain recurrence

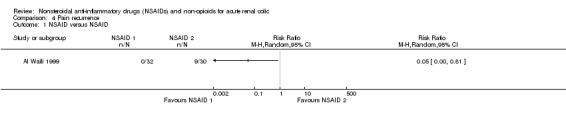

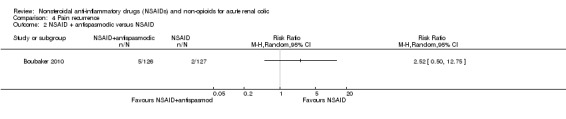

Three studies reported pain recurrence (Al Waili 1999; Boubaker 2010; Grissa 2011).

Al Waili 1999 reported a higher proportion of patients treated with 75 mg diclofenac (IM) showed pain recurrence in the first 24 hours of follow‐up compared to those treated with 40 mg piroxicam (IM) (Analysis 4.1 (1 study, 60 participants): RR 0.05, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.81).

Boubaker 2010 reported no significant difference in pain recurrence at 72 hours between piroxicam plus phloroglucinol and piroxicam plus placebo groups (Analysis 4.2 (1 study, 253 participants): RR 2.52, 95% CI 0.15 to12.75).

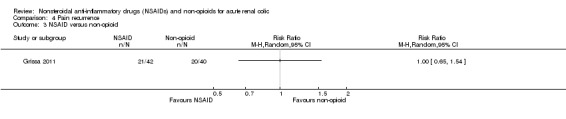

Grissa 2011 reported no significant difference in pain recurrence within 72 hours of discharge between IM piroxicam and IV paracetamol (Analysis 4.3 (1 study, 82 participants): RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.54).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Pain recurrence, Outcome 1 NSAID versus NSAID.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Pain recurrence, Outcome 2 NSAID + antispasmodic versus NSAID.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Pain recurrence, Outcome 3 NSAID versus non‐opioid.

Adverse effects

Reporting adverse effects was variable. Some studies provided detailed tables and some did not cite any side effects (Table 1). In addition reporting the side effects was further complicated by variation in definitions. No study reported serious adverse effects such as gastro‐intestinal bleeding or kidney impairment. Overall, when comparing different NSAIDs, gastrointestinal adverse effects seemed to be a common occurrence (Table 1). In studies which compared NSAIDs with non‐NSAIDs, gastro‐intestinal and central nervous system adverse effects seemed to be more common among the NSAID groups (Table 2; Table 3).

1. Adverse effects for NSAIDs versus NSAIDs.

|

Study |

Comparison | GI | CNS | Injection site | Other | |||||

| NSAID (1) | NSAID (2) | NSAID (1) | NSAID (2) | NSAID (1) | NSAID (2) | NSAID (1) | NSAID (2) | NSAID (1) | NSAID (2) | |

| Sanchez‐Carpena 2003 | Dexketoprofen | Dipyrone | 2/225 | 7/108 | 6 | 4 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 2 |

| Sanchez‐Carpena 2007 | Dexketoprofen | Dipyrone | 39/205 | 22/103 | 4 | 3 | 19 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Sanahuja 1990 | Diclofenac | Baralgan | 0/29 | 0/28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Indudhara 1990 | Diclofenac | Baralgan | 2/33 | 6/30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Miralles 1987 | Diclofenac | Dipyrone | Adverse effects not reported | |||||||

| Muriel‐Villoria 1995 | Diclofenac | Dipyrone | 24/55 | 18/239 | 104 | 134 | 1 | 4 | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Muriel 1993 | Diclofenac | Dipyrone | 6/41 | 11/88 | 59 | 85 | 1 | 2 | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Arnau 1991 | Diclofenac | Dipyrone | 26/116 | 45/227 | 65 | 157 | 13 | 32 | 11 | 37 |

| Marthak 1991 | Diclofenac | Dipyrone + antispasmodic | 5/82 | 8/85 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Fraga 2003 | Diclofenac | Etofenamate | 4/60 | 0/59 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| el‐Sherif 1990 | Diclofenac | Indomethacin | 3/47 | 3/44 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Laerum 1996 | Diclofenac | Indomethacin | 3/41 | 6/42 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Walden 1993 | Diclofenac | Ketoprofen | Total adverse effects: NSAID 1 (7/45); NSAID 2 (10/41) | |||||||

| Stein 1996 | Diclofenac | Ketorolac | 0/30 | 0/27 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cohen 1998 | Diclofenac | Ketorolac | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Al Waili 1999 | Diclofenac | Piroxicam | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Supervia 1998 | Diclofenac | Piroxicam | 0 | 0 | 1/40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mora Durban 1995 | Flurbiprofen | Dipyrone + hyoscine | 0 | 0 | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | 33/67 | 43/68 | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| al‐Sahlawi 1996 | Indomethacin | Lysine acetyl salicylate | Adverse effects not reported | |||||||

| Lehtonen 1983 | Indomethacin | Metamizole | 12 | 7 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Galassi 1983 | Indomethacin | Metamizole | 14/18 | 0/14 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| Lupi 1986 | Indomethacin | Pirprofen | 2 | |||||||

| Glina 2011 | Ketoprofen | Parecoxib | 14/164 | 11/174 | 6 | 10 | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Martin Carrasco 1993 | Ketorolac | Dipyrone + antispasmodic | 1 | |||||||

| Boubaker 2010 | Piroxicam | Piroxicam + phloroglucinol | 9/127 | 10/126 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 3 | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Kekec 2000 | Tenoxicam | Tenoxicam + isosorbide | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

CNS ‐ central nervous system; GI ‐ gastrointestinal; NSAID ‐ nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug

2. Adverse effects for NSAIDs versus non‐opioids.

| Study | Comparison | GI | CNS | Injection site | Other | |||||

| NSAID | Non‐NSAID | NSAID | Non‐NSAID | NSAID | Non‐NSAID | NSAID | Non‐NSAID | NSAID | Non‐NSAID | |

| Benyajati 1986 | Baralgan | Hyoscine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kumar 2011 | Diclofenac | Desmopressin | Adverse effects not reported | |||||||

| Lopes 2001 | Diclofenac | Desmopressin | 1/19 | 0/20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Dash 2012 | Diclofenac | Drotaverine | 8/50 | 0/50 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Quilez 1983 | Diclofenac | N‐butyl hyoscine | No serious side effects were observed | |||||||

| Ergene 2001 | Diclofenac | Ondansetron | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Snir 2008 | Diclofenac | Papaverine | 0/30 | 0 | 0 | 4/29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vignoni 1983 | Diclofenac | Placebo | No adverse effects were observed | |||||||

| Lundstam 1980 | Diclofenac | Placebo | No adverse effects were observed | |||||||

| Stankov 1994 | Dipyrone | Butylscopolamine | 1/36 | 1/33 | ‐‐ | 1 | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | 1 | ‐‐ |

| Lloret 1987 | Dipyrone | Hyoscine | 0 | 0 | 24/48 | 12/23 | 18 | 1 | 13 | 11 |

| Holmlund 1978 | Indomethacin | Placebo | No adverse effects were observed | |||||||

| Jones 1998 | Ketorolac | Hyoscyamine | No adverse effects were observed | |||||||

| Pavlik 2004 | Metamizole | Cizolirtine | 2/32 | 2/31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Grissa 2011 | Piroxicam | Paracetamol | ‐‐ | 1 | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | 1 | ‐‐ |

CNS ‐ central nervous system; GI ‐ gastrointestinal; NSAID ‐ nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug

3. Adverse effects for other comparisons.

|

Study |

Comparison | GI | CNS | Injection site | Other | |||||

| Drug 1 | Drug 2 | Drug 1 | Drug 2 | Drug 1 | Drug 2 | Drug 1 | Drug 2 | Drug 1 | Drug 2 | |

| Iguchi 2002 | Butylscopolamine | Lidocaine | No adverse effects were observed | |||||||

| Romics 2003 | Drotaverine | Placebo | 20 patients in drotaverine, 4 in placebo had mild adverse effects | |||||||

| Bahn Zobbe 1986 | Glucagon | Placebo | 11/18 | 1/19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Caravati 1989 | Nifedipine | Placebo | 1/13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Miano 1986 | Tyropramide | Butylscopolamine | 3/103 | 4/96 | 7 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 |

CNS ‐ central nervous system; GI ‐ gastrointestinal

Discussion

Summary of main results

In this review, our objective was to assess the analgesic efficacy and side effects of different non‐opioids including NSAIDs. This proved to be a challenging task due to a multitude of reasons discussed below.

Our systematic search of the literature yielded 53 studies eligible for review. All studies only included adult patients. Some studies required radiologic evidence of a urinary stone as inclusion criteria and others included patients based on clinical findings. This inconsistency in diagnostic criteria is a potential source of heterogeneity. Although one may argue that as a clinician (dealing with a patient requiring urgent analgesics) decision making based on clinical findings is more realistic and practical.

The studies involved many different medications. Among NSAIDs, metamizole, diclofenac and indomethacin were the most commonly used. Metamizole (dipyrone) is not used in many parts of the world due to the rare but serious hematologic side effect of aplastic anaemia. We have included this medication in our study. Overall NSAIDs were more effective than placebo in alleviating renal colic pain as shown in three relatively old studies. NSAIDs have not been compared to placebo in more recent studies most likely due to ethical issues of using placebo to treat a patient with acute severe pain.

NSAIDs as a group were more efficacious than or comparable to antispasmodics or other non NSAID analgesics. This finding was consistent when proportions of patients with more than 50% reduction in pain or requiring rescue medication or patient reported pain scores were evaluated. In addition, the combination of NSAIDs and antispasmodics was not superior to NSAIDs alone for all assessed outcomes. Patients on combination therapy (NSAID plus antispasmodic) reported lower pain VAS, however the difference was not clinically significant.

Among different types of NSAIDs, higher doses of dipyrone (2 g) seemed to be more efficacious than diclofenac in obtaining long lasting pain relief, and IV doses of dipyrone significantly reduced the need for rescue medication compared to IM doses of dipyrone in one study. Regarding proportion of patients with 50% reduction in pain and need for rescue medication, indomethacin was less effective than other types of NSAIDs.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Data from many studies could not be pooled due to difference in interventions, outcomes measured or presentation of data.

This current review has several limitations common to most systematic reviews. Most of the analyses exhibit significant heterogeneity. Although the presented results are from a random effects model we did not find any significant change when a fixed effect model was used. This points to the fact that the source of heterogeneity is not statistical. There are multiple sources including different inclusion criteria, interventions and outcome measures. For instance, not all NSAIDs may have the same effect on renal colic. Even in the case of the same medication the route of administration and dosing may have been different.

We found the outcome measures a challenging issue. Different measures such as VAS, binary or ordinal measures have been used. The time of outcome assessment was quite variable as well. To overcome this problem we grouped studies together that presented the outcomes as a continuous variable. We also estimated the proportion of patients with at least a 50% reduction in pain in the first hour. We elected to use this measure because of the universal availability of pain assessment results in the first hour. In addition we believe this is a relevant clinical outcome. Synthesis of data at times required some degree of judgment from the authors. Some studies allowed a second dose of the protocol medication or opioids in the case of inadequate pain control. In this situation we only pooled data corresponding to the period before administration of the second dose.

Severe adverse effects such as digestive tract bleeding, renal impairment and in the case of metamizole, blood dyscrasia, were not reported. Recent reports from Sweden have suggested a rate of one case of agranulocytosis in 1700 based on six cases in 10,000 prescriptions. The thoroughness and length of follow up for adverse effect is unknown. Therefore underestimation of adverse effects, especially those manifested beyond the short follow up, is quite possible. It seems minor central nervous symptoms such as dizziness, gastro‐intestinal complaints such as nausea and injection site erythema formed the majority of the adverse effects. We were not able to pool these data to perform a meaningful meta‐analysis. There was insufficient information of adequate quality for any safety analysis. A recent meta‐analysis has shown increased risk of cardiovascular event in patients using diclofenac, similar to Cox‐2 inhibitors. This has resulted in a European wide adverse event alert for this medication (CNT 2013).

Quality of the evidence

The overall quality of the studies was fair. The main issues were unclear methods of randomisation and concealment. In some studies the outcome assessor was not blinded. Since the outcomes were assessed in the same visit, incomplete follow‐up was rare.

Potential biases in the review process

The published protocol was followed to avoid any bias in the review process. Nevertheless, we had to make judgement calls when combining studies and their outcomes. The main challenge in this review is to explain the effects.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Medication used in the treatment of acute renal colic can be categorized in the two broad groups of opioids and non‐opioids. The most commonly used non‐opioids are NSAIDs. Holdgate 2005a compared NSAIDs to opioids and found: "Single bolus doses of both NSAIDs and opioids provide pain relief to patients with acute renal colic". However, patients receiving NSAIDs achieve greater reduction in pain scores and are less likely to require further analgesia in the short term (Holdgate 2005a). To our knowledge, this is the first review investigating NSAIDs and non‐opioids for acute renal colic.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Despite variability in the studies and the evidence not being of the highest quality, we still believe that NSAIDs are an effective treatment for renal colic when compared to placebo or antispasmodics. The addition of antispasmodics to NSAIDs does not result in better pain control. The findings of this review support the use commonly available NSAID such as diclofenac, indomethacin, or ketorolac. We remain uncertain as the effect of metamizole on blood dyscrasia. However, in the presence of other interventions with more certain safety profiles the justification of its use is more difficult, unless there is a remarkable difference in the cost. Data on other types of non‐opioid, non‐NSAID medication is scarce.

Implications for research.

There is lack of studies assessing a combination of different NSAIDs. The optimal dose and route of administration is not clear. More accurate reporting of side effects is required.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the referees for the comments and feedback during the preparation of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Electronic search strategies

| Database | Search terms |

| CENTRAL |

|

| MEDLINE |

|

| EMBASE |

|

Appendix 2. Risk of bias assessment tool

| Potential source of bias | Assessment criteria |

|

Random sequence generation Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence |

Low risk of bias: Random number table; computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots; minimization (minimization may be implemented without a random element, and this is considered to be equivalent to being random). |

| High risk of bias: Sequence generated by odd or even date of birth; date (or day) of admission; sequence generated by hospital or clinic record number; allocation by judgement of the clinician; by preference of the participant; based on the results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; by availability of the intervention. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. | |

|

Allocation concealment Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment |

Low risk of bias: Randomisation method described that would not allow investigator/participant to know or influence intervention group before eligible participant entered in the study (e.g. central allocation, including telephone, web‐based, and pharmacy‐controlled, randomisation; sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes). |

| High risk of bias: Using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non‐opaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure. | |

| Unclear: Randomisation stated but no information on method used is available. | |

|

Blinding of participants and personnel Performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study |

Low risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Blinding of outcome assessment Detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors. |

Low risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, but the review authors judge that the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Incomplete outcome data Attrition bias due to amount, nature or handling of incomplete outcome data. |

Low risk of bias: No missing outcome data; reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size; missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods. |

| High risk of bias: Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size; ‘as‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation; potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Selective reporting Reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting |

Low risk of bias: The study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way; the study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon). |

| High risk of bias: Not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported; one or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. subscales) that were not pre‐specified; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect); one or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis; the study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Other bias Bias due to problems not covered elsewhere in the table |

Low risk of bias: The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

| High risk of bias: Had a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used; stopped early due to some data‐dependent process (including a formal‐stopping rule); had extreme baseline imbalance; has been claimed to have been fraudulent; had some other problem. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists; insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias. |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Pain score: VAS.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 NSAID versus NSAID | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Diclofenac (IM) versus dipyrone (IM) (1 g) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Diclofenac (IM) versus dipyrone (IM) (2 g) | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Diclofenac versus indomethacin | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.4 Diclofenac versus etofenamate | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 NSAID versus antispasmodic | 6 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Including Dash 2012 | 6 | 403 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐9.83 [‐20.93, 1.28] |

| 2.2 Excluding Dash 2012 | 5 | 303 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐12.97 [‐21.80, ‐4.14] |

| 3 NSAID versus non‐opioid | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Diclofenac versus intranasal desmopressin | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 Piroxicam versus paracetamol | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 NSAID + antispasmodic versus NSAID | 2 | 310 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.99 [‐2.58, ‐1.40] |

| 5 Non‐opioid versus placebo | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6 Non‐opioid versus non‐opioid | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6.1 Hyoscine‐N‐butylbromide (IM) versus hyoscine‐N‐butylbromide + intranasal desmopressin | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 2. 50% reduction in pain.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 NSAID versus placebo | 3 | 197 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.28 [1.47, 3.51] |

| 2 NSAID versus NSAID | 14 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Diclofenac (IM) versus dipyrone (IM) (1 g) | 2 | 335 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.72, 1.47] |

| 2.2 Diclofenac (IM) versus dipyrone (IM) (2 g) | 3 | 366 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.81, 1.37] |

| 2.3 Diclofenac (IM) versus dipyrone (IV) (2 g) | 1 | 103 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.49, 0.84] |

| 2.4 Diclofenac versus piroxicam | 2 | 144 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.81, 1.09] |

| 2.5 Diclofenac versus ketoprofen | 1 | 86 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.88, 1.16] |

| 2.6 Dipyrone (2 g) versus dexketoprofen (25 mg) | 2 | 405 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.79, 1.48] |

| 2.7 Dipyrone (2 g) versus dexketoprofen (50 mg) | 2 | 405 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.90, 1.07] |

| 2.8 Dipyrone (2 g) versus dexketoprofen (25 and 50 mg) | 2 | 610 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.85, 1.26] |

| 2.9 Indomethacin versus other NSAID | 4 | 412 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.27 [1.01, 1.60] |

| 2.10 Indomethacin versus pirprofen | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.55, 0.88] |

| 2.11 Ketoprofen versus parecoxib | 1 | 297 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.75, 1.10] |

| 3 NSAID versus antispasmodic | 6 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 NSAID versus hyoscine | 4 | 196 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.44 [1.61, 3.70] |

| 3.2 NSAID versus other antispasmodic | 2 | 163 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.87, 1.17] |

| 4 NSAID versus other non‐opioid | 2 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 Diclofenac versus desmopressin | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 Diclofenac versus ondansetron | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5 NSAID + antispasmodic versus NSAID | 8 | 906 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.89, 1.13] |

| 6 NSAID + non‐opioid versus non‐opioid | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 7 Non‐opioid versus non‐opioid | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 8 Glucagon versus placebo | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Comparison 3. Rescue medication.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 NSAID versus placebo | 3 | 180 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.35 [0.20, 0.60] |

| 1.1 Diclofenac versus saline | 2 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.44 [0.29, 0.65] |

| 1.2 Ketoprofen versus placebo | 1 | 15 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.15 [0.03, 0.67] |

| 1.3 Lysine acetyl salicylate versus placebo | 1 | 15 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.06 [0.00, 0.95] |

| 2 NSAID versus NSAID | 18 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Diclofenac versus other NSAID | 10 | 1263 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.59, 1.03] |

| 2.2 Dipyrone (2 g) versus dexketoprofen (25 mg) | 2 | 405 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.34, 1.36] |

| 2.3 Dipyrone (2 g) versus dexketoprofen (50 mg) | 2 | 405 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.46, 1.73] |

| 2.4 Dipyrone (IV) versus dipyrone (IM) | 1 | 239 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.13 [0.04, 0.45] |

| 2.5 Dipyrone (1 g) IM versus dipyrone (2 g) IM | 1 | 138 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.49, 1.61] |

| 2.6 Dipyrone (1 g) IV versus dipyrone (2 g) IV | 2 | 149 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 5.03 [0.86, 29.25] |

| 2.7 Indomethacin versus lysine acetyl salicylate | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.15 [0.04, 0.65] |

| 2.8 Indomethacin versus other NSAID | 4 | 517 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.36 [0.96, 1.94] |

| 2.9 Ketoprofen versus lysine acetyl salicylate | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.14, 65.90] |

| 2.10 Ketoprofen versus parecoxib | 1 | 337 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.61, 1.68] |

| 3 NSAID versus antispasmodic | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Including Pavlik 2004 | 5 | 363 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.17, 1.48] |

| 3.2 Excluding Pavlik 2004 | 4 | 299 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.14, 0.84] |