Abstract

Tonsillectomy is one of the most common surgical procedures practiced in Otorhinolaryngology. A significant obstacle for the speedy and smooth recovery is early post- operative pain. Pain leads to negative outcomes such as poor intake, tachycardia, anxiety, delayed wound healing and insomnia. Aim to assess and compare the effect of post-incisional infiltration of 0.75% Ropivacaine v/s 0.5% Bupivacaine on post tonsillectomy pain, the on start of oral intake and stay in hospital and to investigate any complications that can arise due to infiltration of the said drugs. 60 Patients above the age of 5 years were posted for tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy under general anesthesia. Patients were blinded about the group in which they will be enrolled. Group A received Inj. ropivacaine (0.75%) 2 ml and Group B: received Inj. Bupivacaine (0.50%) 2 ml in each fossa. After surgery, no analgesics were given & patients were observed for the intensity of post-operative pain in the immediate post-operative period, at 2, 4, 6, 12, 24, 48 h and further if not discharged using VISUAL ANALOGUE SCORE (VAS) and VERBAL RATING SCALE(VRS). Post-operative pain assessment was done using VAS and VRS at 2nd, 4th, 6th, 12th, 24th and 48th hour which was found to be lower in Group ‘A’. Patients in Group ‘A’ also started their oral intake sooner, had lesser hospitalization days than group ‘B’ patients. Longer time for Rescue analgesic and reduced total dose of analgesic required was seen in Group A compared to Group B. This comparative study on Post-incisional infiltration of 2 ml 0.75% Ropivacaine v/s 2 ml 0.5% Bupivacaine has shown that Ropivacaine is a more effective drug in reducing post-operative pain in comparison to Bupivacaine, proven statistically.

Keywords: Tonsillectomy, Post-operative pain, Bupivacaine, Ropivacaine, Post-incisional infiltration, Visual analogue scale, Wong baker facial pain scale

Introduction

Tonsils are the lymphoid tissue in the oropharynx, forming Waldeyer’s ring along with other lymphoid tissue, situated at the entrance of the digestive and respiratory system. They are most active immunologically between 3 and 10 years of age. Tonsils are the targets of infection which are commonly caused by bacteria and viruses [1]. The infection in the tonsils presents with a sore throat and is called tonsillitis. Tonsillectomy is performed for recurrent tonsillitis. In recent times obstructive sleep apnea OSA) is also one of the indications. Tonsils have a rich plexus of nerves around them, thus pain as a symptom is significant cause of morbidity, especially in children. Children refuse oral feeds and medications which cause dehydration, imbalance in electrolytes and decreased nutrition intake [1]. This further increases the need for prolonged hospitalization and intravenous medications and nutrition supplementation. Prolonged hospital stay increases the chances of hospital- acquired or nosocomial infections thereby putting a burden on the patient’s family, institution and nation. A significant obstacle in speedy and smooth recovery is early post- operative pain. Pain leads to negative outcomes such as tachycardia, anxiety, poor wound healing and insomnia [1].

Postoperative pain control, especially in pediatrics population continues to be a big challenge for Otorhinolaryngologists as definite and ideal method of pain relief is not yet known. Postoperative inflammation and spasm of the pharyngeal muscles have shown to cause ischemia in the tonsillar fossa which in turn prolongs the pain cycle.

In an attempt to decrease post tonsillectomy pain, various peri-operative adjuvant therapies such as steroids, analgesics, antibiotics and local anaesthetic infiltration have been tried.

The aim of our study is to compare the effect of post-incisional infiltration of Ropivacaine v/s Bupivacaine on post tonsillectomy pain relief as to date limited studies have been conducted in the Indian population.

Aims and Objectives

To assess and compare the effect of post-incisional infiltration of 0.75% Ropivacaine v/s 0.5% Bupivacaine on post tonsillectomy pain.

To evaluate and compare the effect of both the drugs on the start of oral intake and stay in the hospital.

To investigate any complications that can arise due to infiltration of the said drugs in the peritonsillar fossa.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining Ethical Committee clearance from the Institute, 60 Patients above the age of 5 years following pre anesthetic evaluation and informed written consent were posted for tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy under general anesthesia.

The criteria for selecting patients were as follows.

Inclusion Criteria

Age of patient: ≥ 5 years

- Patient with -

- Recurrent throat infections

- Past history of Peritonsillar abscess

- Tonsillitis causing febrile seizures

- Hypertrophy of tonsils causing a respiratory obstruction

- Suspicion of malignancy

American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Grade I & II

Exclusion Criteria

Acute pharyngeal infection

Peri-tonsillar abscess

Cardiovascular, renal or liver disease

Neurological or psychiatric disease

Coagulation disturbances

Allergy to local anesthetic.

Systemic disease like Diabetes Mellitus, Hypertension or COPD

Patients were blinded about the group in which they were enrolled. Group A: received Inj. ropivacaine (0.75%) 2 ml in each fossa.

Group B: received Inj. Bupivacaine (0.50%) 2 ml in each fossa.

Patients were kept fasting for six hours prior to surgery. The anesthesia technique was standard & uniform for all the patients. All patients were premedicated with midazolam hydrochloride intravenous. Intraoperative analgesics were withheld as they would have altered the results of our study.

Oral endotracheal intubation was performed and Nasal if no adenoid was to be operated upon. Tonsillectomy was be done using Dissection and Snare method.

The solutions 0.75% Ropivacaine or 0.50% Bupivacaine, 2 ml for each tonsillar fossa was infiltrated in the tonsillar bed of each tonsil at the same site, by the same surgeon with a 1 ½ inch 26G needle. No peritonsillar infiltration of adrenaline was given.

After surgery no analgesics were given & patient were observed in a post-operative room for the intensity of post-operative pain in the immediate post operative period, at 2, 4, 6, 12, 24, 48 h and further if not discharged.

At rest

While swallowing (on the consumption of 100 ml water, only after 6 h of surgery, as the patient was kept nil per orally),

Any adverse effects/complications subsequent to the procedure were recorded.

Time to 1st rescue analgesic

Total dose of rescue analgesics

Rescue analgesics included paracetamol in the dose of 10–15 mg/kg per dose, subject to a maximum of 4gm. Depending on the time of requirement it was given either intravenously or orally. Pain at rest reflects the patient's level of comfort. The reduction in pain while swallowing ensures that the patient can quickly return to a normal diet (Figures. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7).

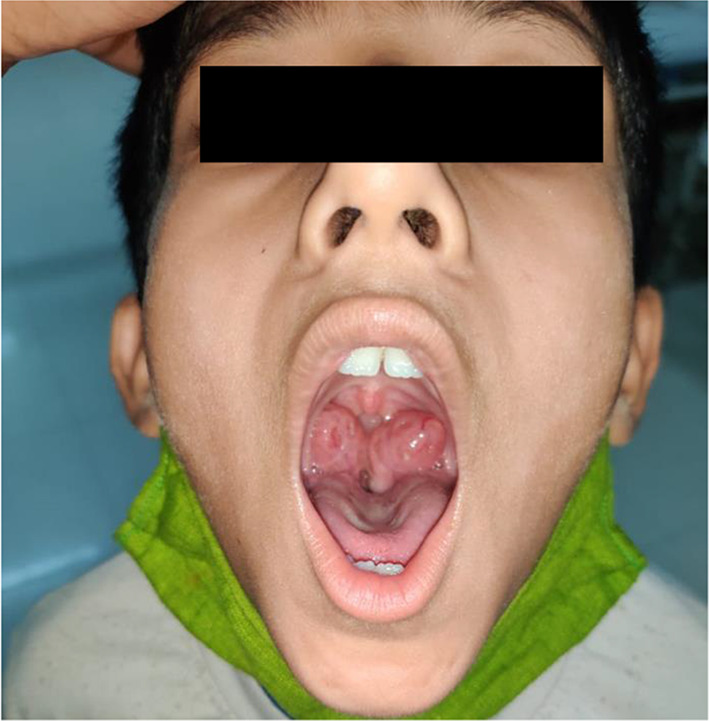

Fig. 1.

Grade 4 tonsillar hypertrophy

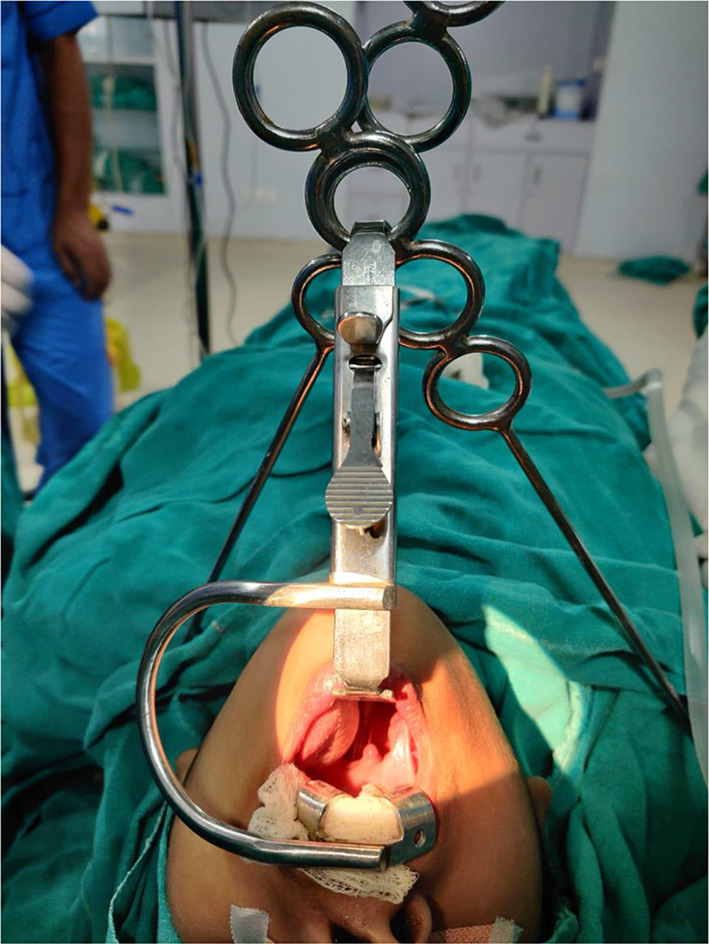

Fig. 2.

Instruments used in tonsillectomy

Fig. 3.

Patient Position during tonsillectomy

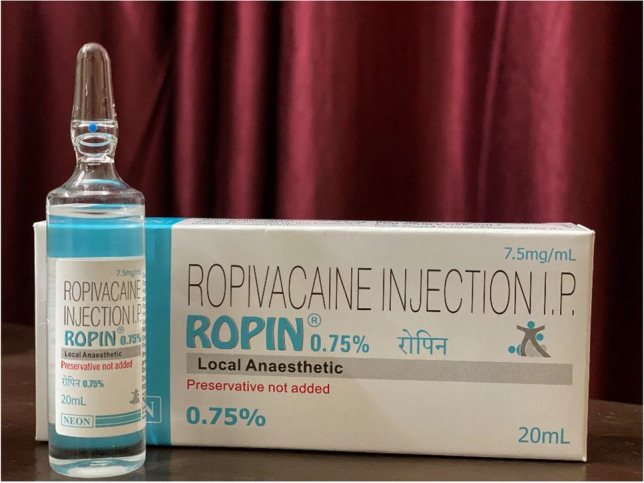

Fig. 4.

Ropivacaine

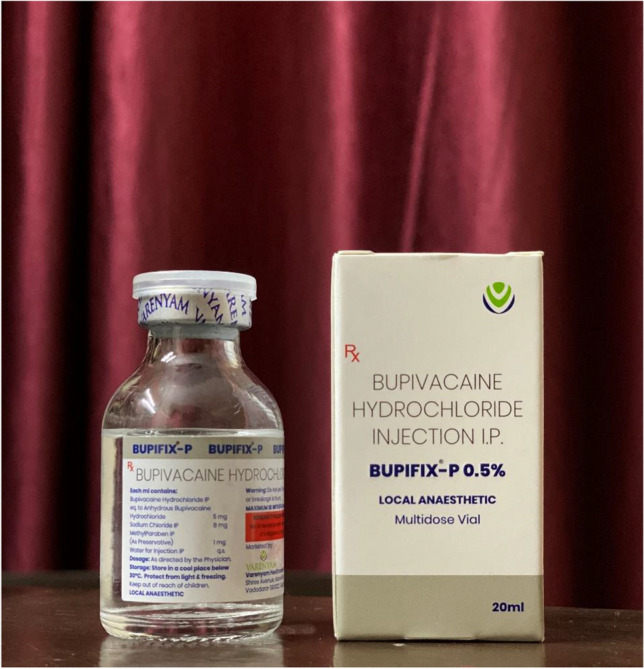

Fig. 5.

Bupivacaine

Fig. 6.

Local infiltration in tonsillar fossa

Fig. 7.

Tonsillar Fossa Post-tonsillectomy

Complications associated with Bupivacaine such as arrythmias, headache, dizziness, increased thirst, blurred vision, irritability, anxiety etc. were monitored.

Complications with Ropivacaine although rare but were monitored for hypotension, bradycardia, transient paraesthesia, back pain, urinary retention, nausea and vomiting, Horner’s syndrome, dyspnoea, shivering, fever.

Pain Assessement Methods

VAS—(VISUAL ANALOGUE SCORE) Rescue analgesia was given when VAS ≥ 4.

VAS—(VISUAL ANALOGUE SCORE) Rescue analgesia was given when VAS ≥ 4.

VRS—(VERBAL RATING SCALE)

Pain on deglutition and parents’s satisfaction score was monitored with a verbal rating scale.

Mild

Moderate

Severe

Results

The average age of the patients in the Ropivacaine group was 21.93 years and in the Bupivacaine group was 20.13. Among the 60 patients part of this study, 23 were female (ropivacaine—14 Bupivacaine—9) and 37 were male (ropivacaine—16 Bupivacaine—21).

Patients were admitted for a total of 5.13 days in the Ropivacaine group and 5.43 days in the Bupivacaine group. This includes one-day of pre-operative admission and one day—the day of operation. The difference between the Ropivacaine and Bupivacaine groups was statistically significant i.e. P < 0.05.

Out of 60 patients operated 24 underwent Adenotonsillectomy and 36 underwent Tonsillectomy.

Ropivacaine was infiltrated in 11 Adenotonsillectomy and 19 Tonsillectomy patients.

Bupivacaine was infiltrated in 13 Adenotonsillectomy and 17 Tonsillectomy patients.

Pain Score

VAS—(VISUAL ANALOGUE SCORE)

The difference between the Ropivacaine and the Bupivacaine Group was found to be statistically significant, i.e. P < 0.05. as shown in Table 1

Table 1.

VAS scoring

| Visual analogue score | Ropivacaine (n = 30) | Bupivacaine (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|

| Pain score | Mean pain score | Mean pain score |

| 2nd hour | 1.83 | 5.5 |

| 4th hour | 1.4 | 6.17 |

| 6th hour | 1.6 | 6.73 |

| 12th hour | 1.73 | 7.27 |

| 24th hour | 1.1 | 2.93 |

| 48th hour | 0 | 1.07 |

Subjective Pain

VRS (Verbal Rating Scale).

Subjective pain was compared at 2nd, 4th, 6th, 12th, 24th and 48th hour post-operatively in the Ropivacaine and Bupivacaine groups which showed statistically significant differences in both groups,

i.e. P < 0.05.as shown in Table 2

Table 2.

VRS score

| Verbal rating score | Drug | Total | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ropivacaine (n = 30) | Bupivacaine (n = 30) | ||||||

| 2nd hour | Mild | 19 | 63% | 1 | 3% | 20 | 0.0001 |

| Mod | 8 | 27% | 10 | 33% | 18 | ||

| Severe | 3 | 10% | 19 | 63% | 22 | ||

| 4th hour | Mild | 22 | 73% | 1 | 3% | 23 | 0.0001 |

| Mod | 8 | 27% | 10 | 33% | 18 | ||

| Severe | 0 | 0% | 19 | 63% | 19 | ||

| 6th hour | Mild | 26 | 87% | 2 | 7% | 28 | 0.0001 |

| Mod | 4 | 13% | 8 | 27% | 12 | ||

| Severe | 0 | 0% | 20 | 67% | 20 | ||

| 12th hour | Mild | 25 | 83% | 2 | 7% | 27 | 0.0001 |

| Mod | 4 | 13% | 6 | 20% | 10 | ||

| Severe | 1 | 3% | 22 | 73% | 23 | ||

| 24 h hour | Mild | 29 | 97% | 20 | 67% | 49 | 0.011 |

| Mod | 1 | 3% | 8 | 27% | 9 | ||

| Severe | 0 | 0% | 2 | 7% | 2 | ||

| 48 h hour | Mild | 30 | 100% | 27 | 90% | 57 | 0.237 |

| Mod | 0 | 0% | 3 | 10% | 3 | ||

In the present study, 24 (80%) patients with Ropivacaine infiltration started oral intake at the 6th hour compared to 7 (23%) patients with Bupivacaine infiltration. 29 (97%) patients with Ropivacaine infiltration started oral intake compared to 17 (57%) patients with Bupivacaine infiltration at the 8th hour. The difference between the Ropivacaine and the Bupivacaine groups was found to be statistically significant, i.e. P < 0.05.

Rescue Analgesic was given when VAS Score was more than 4. The mean time in which patients with Ropivacaine infiltration required rescue analgesic was 5.58 h in comparison to 2.17 h in the Bupivacaine group. The difference in the time required by both the groups was seen to be statistically significant, i.e. P < 0.05.

Data Analysis in Patients Receiving Ropivacaine

Male and Female

When compared between males and females, VAS Score, VRS Score, Time of oral intake and Time to Rescue, the data did not show any significant statistical difference, i.e. P > 0.05.

The total number of days of Admission showed a Statistically Significant difference, i.e. Males have a lesser day of admission as seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

VAS Score, VRS Score, Time of oral intake and Time to Rescue in males and females

| VAS | VRS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ropivacaine infilteration | F (n = 14) | M (n = 16) | p-value | GRADING | F (n = 14) | M (n = 16) | p- value |

| 2nd hour | 2 | 1.69 | 0.685 | MILD | 8 | 11 | 0.713 |

| MOD | 4 | 4 | |||||

| SEVERE | 2 | 1 | |||||

| 4th hour | 1.21 | 1.56 | 0.423 | MILD | 10 | 12 | 0.825 |

| MOD | 4 | 4 | |||||

| 6th hour | 1.29 | 1.88 | 0.202 | MILD | 14 | 12 | 0.103 |

| MOD | 0 | 4 | |||||

| 12th hour | 1.43 | 2 | 0.343 | MILD | 14 | 11 | 0.702 |

| MOD | 0 | 4 | |||||

| SEVERE | 0 | 1 | |||||

| 24th hour | 0.86 | 1.31 | 0.08 | MILD | 14 | 15 | 0.341 |

| MOD | 0 | 1 | |||||

| 48th hour | 0 | 0 | MILD | 14 | 16 | ||

| Oral intake | Female | Male | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th hour | N | 4 | 2 | 0.272 | |

| Y | 10 | 14 | |||

| 8th hour | N | 1 | 0 | 0.277 | |

| Y | 13 | 16 | |||

| Time to first rescue analgesic(hours) | 5.79 | 5.41 | 0.78 | ||

| Total no. of days of admission | 5 | 5.25 | 0.046 | ||

Age < 18 Years and > 18 Years

No Statistically Significant difference was seen in comparing VAS Score, VRS Score, Time of oral intake, Time to Rescue and Total no. of days Admission in Adults (> 18 years) and Pediatrics (< 18 years) patients receiving Ropivacaine as seen in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparing VAS score, VRS score, time of oral intake, time to rescue and total no. of days admission in adults (> 18 years) and pediatrics (< 18 years) patients

| VAS | VRS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ropivacaine infilteration | < 18yrs | > 18 yrs | p- value | Grading | < 18yrs | > 18yrs | p- value |

| 2nd hour | 2.14 | 1.56 | 0.449 | Mild | 8 | 11 | 0.555 |

| Mod | 5 | 3 | |||||

| Severe | 1 | 2 | |||||

| 4th hour | 1.43 | 1.38 | 0.902 | Mild | 10 | 12 | 0.825 |

| Mod | 4 | 4 | |||||

| 6th hour | 1.71 | 1.5 | 0.647 | Mild | 12 | 14 | 0.886 |

| Mod | 2 | 2 | |||||

| 12th hour | 1.64 | 1.81 | 0.78 | Mild | 11 | 14 | 0.54 |

| Mod | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Severe | 1 | 0 | |||||

| 24th hour | 1.07 | 1.13 | 0.841 | Mild | 13 | 16 | 0.277 |

| Mod | 1 | 0 | |||||

| 48th hour | 0 | 0 | Mild | 14 | 16 | ||

| < 18yrs | > 18yrs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral intake | 6th hour | N | 3 | 6 | 0.855 |

| Y | 11 | 24 | |||

| 8th hour | N | 0 | 1 | 0.341 | |

| Y | 14 | 29 | |||

| Time to first rescue analgesic(hours) | 5.18 | 5.94 | 0.576 | ||

| Total no. of days of admission | 5.21 | 5.06 | 0.237 | ||

Adenotonsillectomy and Tonsillectomy

No Statistically Significant difference was seen in comparing VAS Score, VRS Score, Time of oral intake, Time to Rescue and Total no. of days Admission in patients receiving Ropivacaine who underwent Adenotonsillectomy and Tonsillectomy procedure as seen in Table 5.

Table 5.

VAS score, VRS score, time of oral intake, time to rescue and total no. of days admission in patients who underwent adenotonsillectomy and tonsillectomy procedure

| VAS | VRS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ropivac aine infilte ration | Adenotonsi llectomy | Tonsille ctomy | p- val ue | GRA DING | Adenotonsi llectomy | Tonsille ctomy | p- val ue |

| 2nd hour | 1.55 | 2 | 0.568 | Mild | 7 | 12 | 0.713 |

| Mod | 4 | 4 | |||||

| Severe | 0 | 3 | |||||

| 4th hour | 1.27 | 1.47 | 0.656 | Mild | 9 | 13 | 0.825 |

| Mod | 2 | 6 | |||||

| 6th hour | 1.64 | 1.58 | 0.9 | Mild | 9 | 17 | 0.103 |

| Mod | 2 | 2 | |||||

| 12th hour | 1.64 | 1.79 | 0.808 | Mild | 8 | 17 | 0.702 |

| Mod | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Severe | 1 | 0 | |||||

| 24th hour | 1 | 1.16 | 0.567 | Mild | 10 | 19 | 0.341 |

| Mod | 1 | 0 | |||||

| 48th hour | 0 | 0 | Mild | 11 | 19 | ||

| Adenotonsillectomy | Tonsillectomy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral intake | 6th hour | N | 2 | 4 | 0.85 |

| Y | 9 | 15 | |||

| 8th hour | N | 0 | 1 | 0.439 | |

| Y | 11 | 18 | |||

| Time to first rescueanalgesic(hours) | 5.55 | 5.61 | 0.966 | ||

| Total no. of days ofadmission | 5.18 | 5.11 | 0.568 | ||

Data Analysis in patients receiving Bupivacaine.

Male and Female

When compared between males and females, VAS Score, VRS, Time to Rescue, Oral Intake and Total No. of Days of Admission, the data did not show any significant statistical difference, i.e. P > in patients receiving Bupivacaine as seen in Table 6.

Table 6.

VAS Score, VRS Score, Time of oral intake and Time to Rescue in males and females

| VAS | VRS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bupivacaine infilteration | Female | Male | p- value | Grading | Female | Male | p- value |

| 2nd hour | 5.33 | 5.57 | 0.778 | Mild | 0 | 1 | 0.598 |

| Mod | 4 | 6 | |||||

| Severe | 5 | 14 | |||||

| 4th hour | 6 | 6.24 | 0.769 | Mild | 0 | 1 | 0.798 |

| Mod | 3 | 7 | |||||

| Severe | 6 | 13 | |||||

| 6th hour | 7.11 | 6.57 | 0.488 | Mild | 0 | 2 | 0.551 |

| Mod | 2 | 6 | |||||

| Severe | 7 | 13 | |||||

| 12th hour | 7.44 | 7.19 | 0.738 | Mild | 0 | 2 | 0.598 |

| Mod | 1 | 5 | |||||

| Severe | 8 | 14 | |||||

| 24th hour | 2.89 | 2.95 | 0.941 | Mild | 7 | 13 | 0.409 |

| Mod | 1 | 7 | |||||

| Severe | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 48th hour | 1.11 | 1.05 | 0.851 | Mild | 9 | 18 | 0.232 |

| Mod | 0 | 3 | |||||

| Female | Male | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral intake | 6th hour | N | 8 | 15 | 0.85 |

| Y | 1 | 6 | |||

| 8th hour | N | 1 | 12 | 0.439 | |

| Y | 8 | 9 | |||

| Time to first rescue analgesic(hours) | 2.06 | 2.21 | 0.811 | ||

| Total no. of days of admission | 5.56 | 5.38 | 0.394 | ||

Age < 18 years and > 18 years

No Statistically Significant difference was seen in comparing VAS Score, VRS Score, Time of oral intake, Time to Rescue and Total no. of days Admission in Adults (> 18 years) and Pediatrics (< 18 years) patients receiving Bupivacaine as seen in Table 7.

Table 7.

Comparing VAS Score, VRS Score, Time of oral intake, Time to Rescue and Total no. of days Admission in Adults (> 18 years) and Pediatrics (< 18 years) patients

| VAS | VRS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bupivacaine infilteration | < 18yrs | > 18yrs | p- value | Grading | < 18yrs | > 18yrs | p- value |

| 2nd hour | 5.55 | 5.5 | 1 | Mild | 1 | 0 | 0.63 |

| Mod | 5 | 5 | |||||

| Severe | 10 | 9 | |||||

| 4th hour | 6.38 | 5.93 | 0.548 | Mild | 1 | 0 | 0.516 |

| Mod | 6 | 4 | |||||

| Severe | 9 | 10 | |||||

| 6th hour | 6.69 | 6.79 | 0.891 | Mild | 1 | 1 | 0.832 |

| Mod | 5 | 3 | |||||

| Severe | 10 | 10 | |||||

| 12th hour | 7.31 | 7.21 | 0.888 | Mild | 1 | 1 | 0.765 |

| Mod | 4 | 2 | |||||

| Severe | 11 | 11 | |||||

| 24th hour | 3.13 | 2.71 | 0.599 | Mild | 8 | 12 | 0.075 |

| Mod | 7 | 1 | |||||

| Severe | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 48th hour | 1.19 | 0.93 | 0.402 | Mild | 14 | 13 | 0.626 |

| Mod | 2 | 1 | |||||

| < 18yrs | > 18yrs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral intake | 6th hour | N | 11 | 12 | 0.273 |

| Y | 5 | 2 | |||

| 8th hour | N | 8 | 5 | 0.431 | |

| Y | 8 | 9 | |||

| Time to firstrescue analgesic(hours) | 2.31 | 2 | 0.607 | ||

| Total no. ofdays of admission | 5.25 | 5.64 | 0.031 | ||

Adenotonsillectomy and Tonsillectomy

No Statistically Significant difference was seen in comparing VAS Score, VRS Score, Time of oral intake, Time to Rescue and Total no. of days Admission in patients receiving Bupivacaine who underwent Adenotonsillectomy and Tonsillectomy procedure as seen in Table 8.

Table 8.

VAS Score, VRS Score, Time of oral intake, Time to Rescue and Total no. of days Admission in patients who underwent Adenotonsillectomy and Tonsillectomy procedure

| VAS | VRS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bupivac aine infilte ration | Adenotonsi llectomy | Tonsille ctomy | p- val ue | grading | Adenotonsi Llectomy | Tonsille ctomy | p- val ue |

| 2nd hour | 5.15 | 5.76 | 0.431 | Mild | 1 | 0 | 0.404 |

| Mod | 5 | 5 | |||||

| Severe | 7 | 12 | |||||

| 4th hour | 6.08 | 6.24 | 0.833 | Mild | 1 | 0 | 0.404 |

| Mod | 5 | 5 | |||||

| Severe | 7 | 12 | |||||

| 6th hour | 6.69 | 6.76 | 0.92 | Mild | 1 | 1 | 0.873 |

| Mod | 4 | 4 | |||||

| Severe | 8 | 12 | |||||

| 12th hour | 7.38 | 7.18 | 0.767 | Mild | 1 | 1 | 0.852 |

| Mod | 2 | 4 | |||||

| Severe | 10 | 12 | |||||

| 24th hour | 2.62 | 3.18 | 0.474 | Mild | 7 | 13 | 0.407 |

| Mod | 5 | 3 | |||||

| Severe | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 48th hour | 1.15 | 1 | 0.622 | Mild | 11 | 16 | 0.39 |

| Mod | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Adenotonsillectomy | Tonsillectomy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral intake | 6th hour | N | 8 | 15 | 0.087 |

| Y | 5 | 2 | |||

| 8th hour | N | 5 | 8 | 0.638 | |

| Y | 8 | 9 | |||

| Time to first rescue analgesic(Hours) | 2.35 | 2.03 | 0.605 | ||

| Total no. of days of admission | 5.38 | 5.47 | 0.651 |

Discussion

Tonsillectomy is one of the most common surgical procedures performed. Advances in both surgical and anaesthetic techniques have led to reduced surgical time with fewer complications. Pain after tonsillectomy still remains an important problem. Various surgical and medical techniques have been studied in search of safe and effective post-tonsillectomy pain relief [2]. Research studies have been conducted on the impact of local infiltration on the reduction of post-tonsillectomy pain but the results were contradictory. This can be caused by problems such as insufficient sample size, different techniques, different timing of infiltration and different concentration of the drug.

Local Anesthetics (LAs) block the formation of action potential generation by blocking sodium channels. LAs block conduction in the following order: small myelinated axons, non- myelinated axons, large myelinated axons. Nociceptive and sympathetic transmission is thus blocked first [3].

In the present study, post-incisional infiltration of either bupivacaine or ropivacaine resulted in better relief in postoperative pain following tonsillectomy and adenotonsillectomy in paediatric and adult patients operated under general anaesthesia.

A few studies have included only the adult population, so in our study, we included patients of all age groups.

Giannoni et al. noted that injecting ropivacaine with clonidine prior to tonsillectomy resulted in decreased pain, less analgesic use and faster return to normal activity compared to the placebo group in the pediatric age group [4].

A recent study also suggested that the surgical incision and perioperative events result in noxious changes in the CNS (central nervous system) that later contribute to post-operative pain [5]. The reason for the pain, therefore, cannot be explained by the presence of a local anesthetic in the area of surgery for a long time. Such long-term pain relief can be caused by the neural blockade, preventing nociceptive sensations from entering the central nervous system during and immediately after surgery and thus preventing the formation of a stable hyperexcitable state responsible for the maintenance of post-surgical pain. Local anaesthetics acts by inducing the antinociceptive effect on the nerve membranes. However, they affect the membrane-bound proteins of any tissue. They can inhibit the release and activation of agents that activate or sensitize nociceptors and participate in inflammation (prostaglandins, lysosomal enzymes, etc.) [6]. Thus, infiltration into the area before incision gives the local anesthetic sufficient time to have the local effect as well as a central action.

Usually, local anesthetics used for regional anesthesia in pediatric patients are amide in nature. These local anesthetics are blockers of sodium channels, which affect their action. In toxic concentrations, they can result in severe cardiac arrhythmias and even cardiac arrest. These agents are bound to serum proteins and metabolized by cytochrome P450. The intrinsic clearance of bupivacaine is lower in children as compared to that adults. Ropivacaine can be used even in younger patients as its clearance is not low as expected in comparison to adults [7].

There have been a few conflicting reports comparing the efficacy and the safety of ropivacaine and bupivacaine in controlling pain post-tonsillectomy. Akoglu and colleagues in the year 2006, compared the effects of 0.2% ropivacaine and 0.25% bupivacaine on post-tonsillectomy pain 24 h post- surgery [8]. They inferred 0.2% ropivacaine infiltration was a safe and effective method and equivalent to 0.25% bupivacaine in controlling post-tonsillectomy pain. According to trials of Unal et al. [9] and Akoglu et al. [8], the dose of ropivacaine was too low in preventing postoperative pain after tonsillectomy operations. So, in our study, a higher concentration of ropivacaine solution was taken compared to the above studies.

The duration of postoperative pain assessment was another limitation of the studies done by Unal et al. [9] and Akoglu et al. [8]. The studies assessed pain only for a duration of 24 h but in our study, we observed the pain for 48 h post-op. Thus, a prolonged pain follow-up was taken into account. In our study, the pain scores of the ropivacaine group (drug A) were significantly lower at rest and at the time of swallowing. The effective and prolonged pain relief is due to the neural blockade that prevented the nociceptive impulses from entering the CNS during and immediately after surgery. Thus, it suppressed the formation of a sustained hyper-excitable state that is responsible for the maintenance of postoperative pain.

Some of the studies also used epinephrine along with ropivacaine for infiltration. We did not prefer using epinephrine in conjunction with ropivacaine or bupivacaine as it is reported to have caused pulmonary edema and intracranial hemorrhage by Tajima et al.1997 [10]. A rare case of a 16-year-old girl who developed cardiac asystole and a central medullo-pontine infarct following injection with bupivacaine with epinephrine in the bed of tonsils and adenoids has been reported [11].

Fortunately, we did not encounter any central nervous system or cardiac side effects from infiltration of both ropivacaine and bupivacaine.

One of the other shortcomings of some studies was due to their small sample size and only focus on adult patients, as conducted by Arikan OK et al. in 2006 and 2008 [12, 13]. Thus, their results cannot be compared with our study as we have included the pediatric age group as well. In contrast to our study epinephrine was also used with ropivacaine. A very high concentration of ropivacaine i.e., 2% ropivacaine was injected into twenty adult patients who were assessed for pain at rest and swallowing. Rather than studying the drugs in different patients, they infiltrated ropivacaine in one tonsillar fossa and the other fossa was infiltrated with saline. They concluded that infiltrating with ropivacaine significantly reduced postoperative pain at rest and most importantly while swallowing [12].

In our study, we found that ropivacaine offered significant pain relief beyond 48 h. The prolonged pain relief in the study by Arikan OK et al., 2006[12] may be due to more concentration (2%) of ropivacaine as compared to 0.75% ropivacaine used in our study. Such a high concentration of the drug was not used in our study as our study included patients who were children.

In the year 2008, the same author conducted a study to compare the efficacy of pre-incisional high- dose ropivacaine and bupivacaine for post-tonsillectomy pain. Fifty-eight adult patients were selected and divided into three groups for infiltration of ropivacaine, bupivacaine and saline. They concluded that pre-incisional infiltration with ropivacaine markedly reduced the pain post tonsillectomy when compared to bupivacaine and saline. A reduced amount of additional analgesic intake was seen in the ropivacaine group. Again, the author had used all three drugs with epinephrine which we did not use in our study [13].

In the year 2011, a prospective, randomized and placebo controlled trial comparing bupivacaine with its S- enantiomer levobupivacaine was done by Kasapoglu et al. [14] in children. The study consisted of 60 children, which concluded that both levobupivacaine and bupivacaine were more effective than saline [14]. The S- enantiomer and the racemate were equally potent. However, animal studiesvand experience in humans, both suggest that levobupivacaine is less cardiotoxic than bupivacaine [15].

Mahmut et al. in the year 2012, compared ropivacaine, bupivacaine and lidocaine in the management of post-tonsillectomy pain in children. 120 children were a part of the study using a higher dose of ropivacaine 0.5% compared to 0.25% of bupivacaine and lidocaine. The visual analogue scale was used to record the pain, also other parameters like operative time, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative hemorrhage etc. were also observed. The results concluded that ropivacaine infiltration is equally effective as bupivacaine for post-tonsillectomy pain management in children. However, in view of the potential side effects of the bupivacaine-epinephrine combination, ropivacaine is a much safer choice, for post-tonsillectomy relief in pain in children [16].

As per the AAO HNS guidelines 2011, regarding the indications of tonsillectomy [17], perioperative and postoperative care, special emphasis has been given to controlling the postoperative pain following tonsillectomy and recommended the use of appropriate measures for proper analgesia.

The infiltration with local anesthetic has resulted in a significant reduction in duration and total dosage of systemic analgesics and is also associated with an increase in time to rescue analgesic. So, it encourages patients to have good oral intake, in turn, shorten the hospital stay reducing the risk of acquiring hospital acquired infections and reducing the financial burden on the institution as well as the family. Most of the patients in the Ropivacaine group had a relatively comfortable post-op recovery and did not complain much of pain or any difficulty in feeding in comparison to most of the patients in the Bupivacaine group. No adverse drug reactions or side effects were observed with patients receiving ropivacaine and bupivacaine.

Thus, our study concludes that Drug A—Ropivacaine is an effective and safer method for post- operative analgesia in pediatric as well as adults.

Conclusion

This comparative study on Post-incisional infiltration of 2 ml 0.75% Ropivacaine v/s 2 ml 0.5% Bupivacaine has shown that Ropivacaine is a more effective drug to reducing post-operative pain in comparison to Bupivacaine, proven statistically. Also, we inferred Ropivacaine is better for the early start of oral intake and early discharge from the hospital.

Though in our study there were no complications with Ropivacaine or Bupivacaine the literature suggests Ropivacaine be safer due to fewer systemic side effects.

Thus, we suggest the use of Ropivacaine routinely in all cases of Adenotonsillectomy or Tonsillectomy irrespective of the Age or Gender of the patient.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethics Approval

Institutional Ethical Committee Approval taken before the study.

Informed Consent

Informed Written Consent about the study taken before every surgery in the patient’s own vernacular language.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mehta DM (2019) A Randomised double blind clinical trial to compare the effects of preincisional infiltration of ropivacaine v/s bupivacaine on post tonsillectomy pain relief. J Med Sci Clin Res [Internet]. 7(5). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333223115_A_Randomised_double_blind_clinical_trial_to_compare_the_effects_of_preincisional_infiltration_of_ropivacaine_vs_bupivacaine_on_post_tonsillectomy_pain_relief

- 2.Robinson SR, Purdie GL. Reducing post-tonsillectomy pain with cryoanalgesia: a randomized controlled trial. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(7):1128–1131. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200007000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor A, McLeod G. Corrigendum to ‘Basic pharmacology of local anaesthetics’[BJA Education 20 (2020) 34–41] BJA Ed. 2020;20(4):140. doi: 10.1016/j.bjae.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giannoni C, White S, Enneking FK, Morey T. Ropivacaine with or without clonidine improves pediatric tonsillectomy pain. Archiv Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2001;127(10):1265–1270. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.10.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katz J, Kavanagh BP, Sandler AN, Nierenberg H, Boylan JF, Friedlander M, Shaw BF (1992) Preemptive analgesia. Clinical evidence of neuroplasticity contributing to postoperative pain. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1519781/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.JF B, GR S. (1990) Molecular mechanisms of local anesthesia: a review. Anesthesiology [Internet]. 72(4):711–34. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2157353/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Jx M, Bj D (2004) Pharmacokinetics of local anaesthetics in infants and children. Clin Pharmacokinet [Internet]. 43(1):17–32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14715049/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Akoglu E, Akkurt BCO, Inanoglu K, Okuyucu S, Daglı S. Ropivacaine compared to bupivacaine for post-tonsillectomy pain relief in children: a randomized controlled study. Int J Pediatric Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70(7):1169–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unal Y, Pampal K, Korkmaz S, Arslan M, Zengin A, Kurtipek O. Comparison of bupivacaine and ropivacaine on postoperative pain after tonsillectomy in paediatric patients. Int J Pediatric Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71(1):83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tajima K, Sato S, Miyabe M. A case of acute pulmonary edema and bulbar paralysis after local epinephrine infiltration. J Clin Anesth. 1997;9(3):236–238. doi: 10.1016/S0952-8180(97)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park AH, Pappas AL, Fluder E, Creech S, Lugo RA, Hotaling A. Effect of perioperative administration of ropivacaine with epinephrine on postoperative pediatric adenotonsillectomy recovery. Archiv Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(4):459–464. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arikan OK, Ozcan S, Kazkayasi M, Akpinar S, Koc C. Preincisional infiltration of tonsils with ropivacaine in post-tonsillectomy pain relief: double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled intraindividual study. J Otolaryngol. 2006;35(3):167–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arikan OK, Sahin S, Kazkayasi M, Muluk NB, Akpinar S, Kilic R. High-dose ropivacaine versus bupivacaine for posttonsillectomy pain relief in adults. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;37(6):836–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasapoglu F, Kaya FN, Tuzemen G, Ozmen OA, Kaya A, Onart S. Comparison of peritonsillar levobupivacaine and bupivacaine infiltration for post-tonsillectomy pain relief in children: placebo-controlled clinical study. Int J Pediatric Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;75(3):322–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grubb T, Lobprise H. Local and regional anaesthesia in dogs and cats: Overview of concepts and drugs (Part 1) Veterinary Med Sci. 2020;6(2):209–217. doi: 10.1002/vms3.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Özkiriş M, Kapusuz Z, Saydam L. Comparison of ropivacaine, bupivacaine and lidocaine in the management of post-tonsillectomy pain. Int J Pediatric Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;76(12):1831–1834. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baugh RF, Archer SM, Mitchell RB, Rosenfeld RM, Amin R, Burns JJ, Patel MM. Clinical practice guideline: tonsillectomy in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144:S1–S30. doi: 10.1177/0194599810389949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]