Abstract

Giant Cell Tumors of the skull are rare and mostly occur in the middle cranial fossa. Radiological investigations serve as adjunct modalities; however, histopathological confirmation is mandatory. Ten to forty% of GCTs may be recurrent. Complete surgical resection is the treatment of choice, however, partial resection with adjuvant radiotherapy can serve as a secondary alternative. Recurrent cases require post-op radiotherapy. Here, we describe a case of recurrent giant cell tumor of sphenoid bone in a young male, who underwent surgical resection twice, after which he was advised adjuvant radiotherapy and denosumab. The patient did not take radiotherapy.

Keywords: Giant cell tumor (GCT), Sphenoid bone

Introduction

Giant Cell Tumor (GCT) is a benign osseous neoplasm which most commonly occurs in the epiphyses of long bones, constituting approximately 5% of all skeletal tumors. Although, mostly benign, they can have a recurrence rate reaching to 30%, especially if managed only via resection [1].

They rarely occur in the skull (only 1%) and are generally encountered in the sphenoid and temporal bones. Adverse effects of these lesions are due to compression, resulting in cranial nerve deficits [2]. Gross total resection is curative in most of these cases but in recurrent lesions, there is a substantial role of radiotherapy.

We report a case of recurrent giant cell tumor of sphenoid bone in a young male, which is a rare finding.

Case Report

After obtaining informed consent from the patient, a detailed history was recorded. A 24-year-old male had complaints of loss of vision in his right eye for the last 2 years. He had no neurological deficit. In March 2021, the patient was evaluated at a local eye hospital. Later, CEMRI brain was advised which suggested a primary neoplastic sphenoid sinus mass measuring 4.19 × 3.05 × 3.37 cm (AP × CC × TR) with differential diagnosis of Chordoma and Leiomyosarcoma. He underwent endoscopic excision of the lesion and a biopsy of the excised specimen revealed GCT of bone.

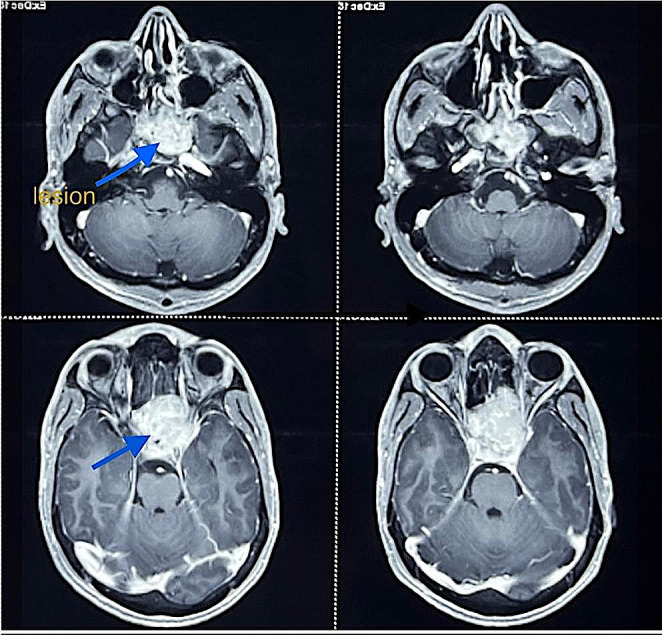

Post resection, his vision improved, and he remained asymptomatic for a year after which he again experienced blurring of vision in his right eye (December 2022). On evaluation, neurological examination was normal, but the patient had a visual acuity of 1/60. Fundus examination showed right eye secondary optic atrophy. Pre-Op CEMRI Brain with PNS done in Oct 2022 (Fig. 1) revealed a relatively ill-defined T1 hypointense T2 hyperintense mass measuring 4.1 × 4.3 × 4.5 cm (AP × TR × CC) involving both sphenoid sinuses. Superiorly the mass was causing a bulge of the superior wall of sphenoid sinus. Patient then underwent Transnasal Transsphenoidal excision of Giant Cell Tumor present in sellar region under general anaesthesia on 21st Dec 2022.

Fig. 1.

Pre-op CEMRI showing T2 hyperintense mass measuring

4.1 × 4.3 × 4.5 cm (AP × TC × CC) involving both sphenoid sinus

Post op histopathology report (Fig. 2) revealed tumor comprising of large number of osteoclastic giant cells along with mononuclear round to oval cells and a few spindle cells arranged in sheets. The individual cell shows fine chromatin, inconspicuous to prominent nuclei and pale eosinophilic cytoplasm.

Fig. 2.

H & E stained (10x) showing singly scattered monomorphic round to spindle cells along with osteoclastic giant cells

After Post op NCCT head was done, he was advised denosumab from medical oncology department and in view of recurrent lesion, was sent to us for adjuvant radiotherapy. The patient did not take radiotherapy.

Discussion

Giant Cell Tumor (GCT) is commonly found in long bones (75–90% of cases) and rarely occurs in the skull. Leonard et al. found that only 1% of GCTs were seen in craniofacial region, and majority of them involved bones of the middle cranial fossa like the temporal and sphenoid bones [3].

The most common clinical presentation is headache followed by features of cranial nerve palsies. However, diplopia and loss of vision are commonly seen in GCTs of sphenoid bone [4]. Features suggestive of GCT of sphenoidal bone on CT scan are an expansive lytic lesion with an epicenter in infrasellar fossa and tumor calcifications may also be detected. MRI will show cystic and solid components which are iso or hypointense in T1 or T2, with enhancement post-contrast administration. Differential diagnosis includes chordoma, large pituitary tumor, eosinophilic granuloma, cancer of the nasopharynx, giant cell reparative granuloma among others. Hence, histopathological confirmation is mandatory [5].

Ten to forty% of GCTs may be recurrent. A study done by Antal et al. revealed DNA ploidy and increased expression of Ki-67 in tumor cells to be associated with this risk of recurrence [6]. Complete surgical resection is the treatment of choice for GCTs outside head and neck region. In a systematic review conducted by Weng et al., partial resection, no radiotherapy and ki-67 ≥ 10% were identified as independent risk factors for progression-free survival. GTR alone or GTR plus radiotherapy was concluded to be optimal with partial resection plus ≥ 45 Gy radiotherapy to be used as a secondary alternative [7].

Malone et al., in their study, suggested radiotherapy to be an effective modality in absence of surgical feasibility. Post-op radiotherapy was especially effective in malignant pathology with a high ki-67 index (≥ 10%) regardless of extent of resection, recurrent GCTs and residual tumors [8]. Hence, our case warranted use of post-op radiotherapy as it was a recurrent case. Other modalities that can be used for recurrent GCTs are gamma knife radiosurgery (Kim et al., 2012) and Interferon α2b (Caudell et al., 2003).

Studies demonstrating role of Chemotherapy in GCTs have been limited. Roux et al. reported overexpression of RANKL (Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor NF-kβ ligand) by GCTs which resulted in overactivation of osteoclasts. Denosumab, a monoclonal antibody against RANKL was thus, tested [9]. Further trials conducted showed that Denosumab can be considered as an effective treatment for advanced cases of GCT (inoperable or metastatic) and was approved by the FDA in 2013 [10].

Conclusion

In conclusion, various therapeutic dilemmas are yet to be answered in cases of skull GCTs. This report contributes to the few reported cases of skull based GCTs, especially sphenoidal bone GCTs, in literature. Awareness of its occurrence at this site is important for proper diagnosis and treatment.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

The above report is compliant with ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest

The authors cite no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Freeman JL, Oushy S, Schowinsky J, Sillau S, Youssef AS. Invasive giant cell Tumor of the lateral Skull Base: a systematic review, Meta-analysis, and Case Illustration. World Neurosurg. 2016;96:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.05.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Billingsley JT, Wiet RM, Petruzzelli GJ, Byrne R. A locally invasive giant cell Tumor of the skull base: case report. J Neurol Surg Rep. 2014;75(1):e175–e179. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1378153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leonard J, et al. Malignant giant-cell Tumor of the parietal bone: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2001;48(2):424–429. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200102000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isaacson B, Berryhill W, Arts HA. Giant-cell tumors of the temporal bone: management strategies. Skull Base. 2009;19(4):291–230. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1115324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Heijden L, Dijkstra PDS, Blay JY, Gelderblom H. Giant cell tumour of bone in the denosumab era. Eur J Cancer. 2017;77:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antal I, Sa ´pi Z, Szendroi M. The prognostic significance of DNA cytophotometry and proliferation index (Ki-67) in giant cell tumors of bone. Int Orthop. 1999;23:315–319. doi: 10.1007/s002640050381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weng JC, Li D, Wang L, Wu Z, Wang JM, Li GL, Jia W, Zhang LW, Zhang JT. Surgical management and long-term outcomes of intracranial giant cell tumors: a single-institution experience with a systematic review. J Neurosurg. 2018;131(3):695–705. doi: 10.3171/2018.4.JNS1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malone S, O’Sullivan B, Catton C, Bell R, Fornasier V, Davis A. Long-term follow-up of efficacy and safety of megavoltage radiotherapy in high-risk giant cell tumors of bone. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;33:689–694. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00159-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roux S, Amazit L, Meduri G, Guiochon-Mantel A, Milgrom E, Mariette X. RANK (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B) and RANK ligand are expressed in giant cell tumors of bone. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;117:210–216. doi: 10.1309/BPET-F2PE-P2BD-J3P3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luengo-Alonso G, Mellado-Romero M, Shemesh S, Ramos-Pascua L, Pretell-Mazzini J. Denosumab treatment for giant-cell Tumor of bone: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2019;139(10):1339–1349. doi: 10.1007/s00402-019-03167-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]