Abstract

Pneumatized middle turbinate (Concha bullosa) is one of the commonest intranasal anatomical variants. Surgery is the effective method to control symptomatic concha bullosa, however, still no clear definition for the best surgical technique. The aim of our study to assess and compare the short-term outcomes of crushing and lateral laminectomy with and without mucosal preservation in the surgical treatment of symptomatic concha bullosa. Thirty patients who underwent concha bullosa surgery (a total of 42 conchae surgeries) were included in this prospective randomized study. Patients were allocated consecutively and equally into 3 groups: Group A (lateral laminectomy without mucosal preservation, n = 10), Group B (lateral laminectomy with mucosal preservation, n = 10) and Group C (Crushing, n = 10). Patients underwent the preoperative and postoperative visual analogue score (VAS) for nasal obstruction and headache, sinonasal outcome test-22 (SNOT-22) and olfactory detection test. All patients were arranged to postoperative reevaluation for 3 months. All groups showed strong significant improvement in VAS results, SNOT-22 and smell test between preoperative and postoperative scores (P < 0.001). There was a significant difference between the three groups only upon comparing lateral laminectomy groups with crushing group. No significant differences were detected between group A and B regarding all the evaluated variables. According to our results, lateral laminectomy was more advantageous than crushing in surgical management of concha bullosa. Moreover, lateral laminectomy without mucosal preservation was as effective as lateral laminectomy with mucosal preservation and there is no detectable difference between both techniques.

Keywords: Middle Turbinate, Concha Bullosa, Crushing, Lateral Laminectomy, Mucosal Preservation

Introduction

Middle nasal turbinates are important anatomical structures arising from the lateral nasal wall and carries various functions such as smelling, lamination of air flow, warming and humidification of inspired air [1]. Several types of anatomical variations of the middle turbinate were described, however, the pneumatized middle turbinate (concha bullosa) is the most frequently encountered variation and can be the cause of nasal obstruction, chronic sinusitis, headache and impair olfaction [2, 3].

Several techniques have been defined for the surgery of symptomatic concha bullosa; namely, partial lateral laminectomy, total lateral laminectomy, medial laminectomy, conchapexy and crushing [2–4]. However, there is no clear consensus for the best surgical technique and also there are still questions to be answered concerning where and how much middle turbinate should be resected.

Till now, no much more enough comparative studies evaluating the results of these different surgical techniques have been conducted so far. Here in this study we compare the outcomes of the most commonest 3 surgical techniques for treatment of symptomatic concha bullosa; crushing, lateral laminectomy with mucosal preservation and lateral laminectomy without mucosal preservation.

Materials and Methods

This prospective randomized study was carried out on 30 patients who were presented to outpatient clinic of ENT department of Minia University Hospital with symptomatic concha bullosa, from October 2022 till May 2023. Ethical permission was sought from a local faculty of medicine research ethics committee (FMREC) No:25:3/2022. According to committee protocol all patients consented for data retrieval for research purposes.

Patients complaining mainly of headache, nasal obstruction or both without significant improvement on various medications with positive topical xylocaine test were only included in this study after nasal endoscopic assessment and radiological CT scanning of the nose and paranasal sinuses. Patients with asymptomatic concha bullosa, age under 18 years, underwent previous nasal surgery, had a concomitant nasal pathology such as; chronic rhinosinusits with or without nasal polyposis, allergic rhinitis and deviated nasal septum were excluded from this study. Patients also with debilitating disease or unfit for surgery were not included in the study.

Patients were equally and randomly assigned into three groups, Group A (lateral laminectomy without mucosal preservation, n = 10), Group B (lateral laminectomy with mucosal preservation, n = 10) and Group C (Crushing, n = 10). All patients underwent the preoperative and postoperative visual analogue score (VAS) to show obstructive and headache symptoms subjectively. For a nasal obstruction, the range was from 0 to 10, with 0 reflecting total obstruction and 10 representing a fully opened nasal passage. For headache, mild headache = VAS 0–3, moderate headache = VAS > 3–7 and severe headache = VAS > 7–10. The sinonasal outcome test-22 (SNOT-22) was used to evaluate the severity of sinonasal symptoms and it consists of 22 items with total score ranged from 0 to 110, higher SNOT-22 total scores indicates worse symptoms. Butanol smell test was used to assess the ability of subjects to identify odors using different concentrations of butanol in bottles numbered from 0 to 9 and olfactory detection has inverse relationship to olfactory threshold, the higher the olfactory detection score, the lower the olfactory threshold. Postoperative evaluation was recorded after 1, 2 and 3 months.

Operative Technique

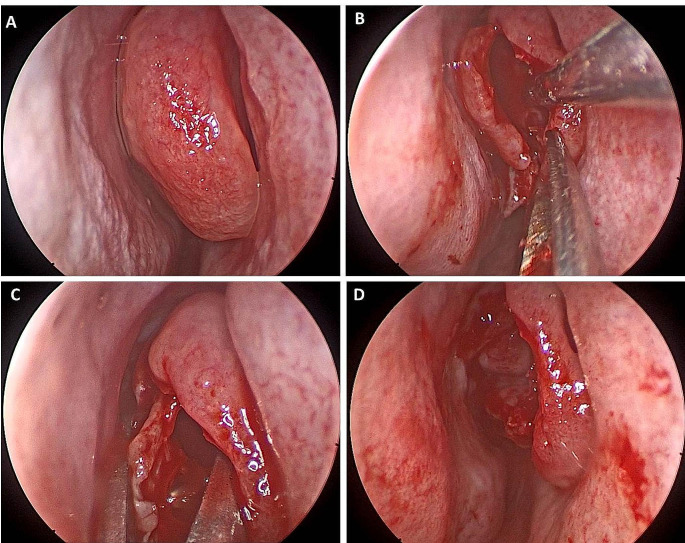

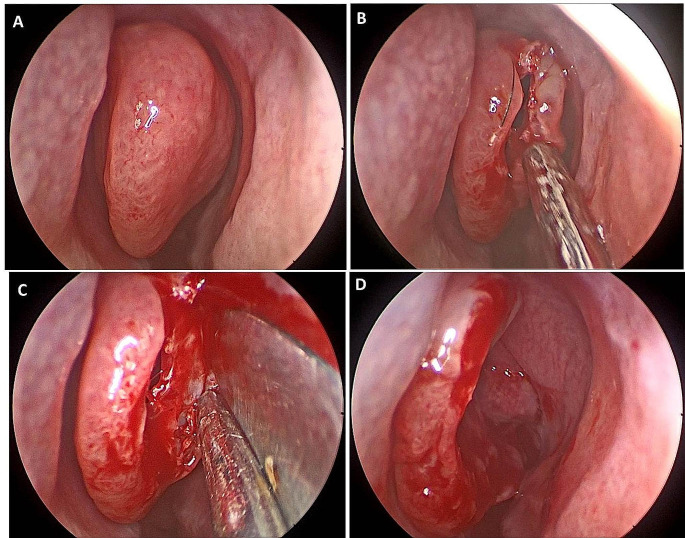

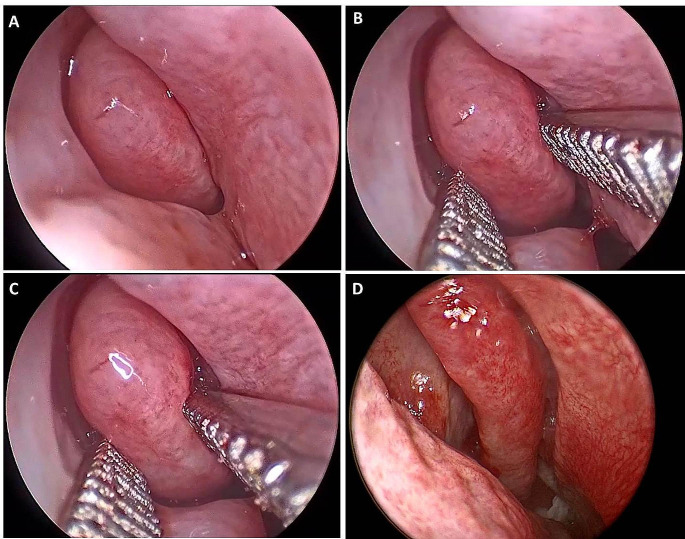

All surgical procedures were performed using zero degree endoscope under general anesthesia. Following a midline incision of the anterior part of the concha bullosa with a sickle knife and the cut was completed by the turbinate scissor For lateral laminectomy without mucosal preservation performed in group A, the anterior and lateral parts of the concha bullosa, including both mucosa and underlying bone were remove. (Fig. 1). For lateral laminectomy with mucosal preservation performed in group B, the anterior and lateral bony parts of the concha bullosa were removed leaving the covering mucosa intact. (Fig. 2). Crushing was performed on patients in group C, this technique was carried out using an artery forceps, and crushing was started at the upper merging point of the middle concha, and proceeded inferiorly and posteriorly. (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Showing endoscopic view of (A) Right concha bullosa (B) Midline vertical incision of antero-inferior surface of the right side middle turbinate (C) Removal of mucosa and bone of lateral lamellae of middle turbinate by Blakeley forceps (D) Final view of the remained middle turbinate

Fig. 2.

Showing endoscopic view of (A) Left concha bullosa (B) Midline vertical incision of antero-inferior surface of the left side middle turbinate (C) Dissecting bone from a mucosal coverings of left middle turbinate (D) Final view after removal of bone only with subsequent repositioning of mucosal flap

Fig. 3.

Showing endoscopic view of (A) Right concha bullosa (B) Crushing of the upper part of concha bullosa (C) Crushing of the lower part of concha bullosa (D) Final view of the right middle turbinate after crushing

Statistical Analysis

The analysis of the data was carried out using the IBM SPSS 28.0 statistical package software (IBM; Armonk, New York, USA). Quantitative data were expressed as median, interquartile range (IQR) and mean ± SD, in addition to both number and percentage for categorized data. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was performed to assess comparisons among independent groups. Friedman test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test were performed to evaluate the differences at each follow-up compared to preoperative values in the same group. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of thirty patients were included in the study, 18 patients had unilateral concha bullosa and 12 patients had bilateral concha bullosa (a total of 42 conchae surgeries). Demographic data of all patients were recorded in (Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference between the groups regarding age and sex (p > 0.05). There was no statistically significant difference between the 3 groups regarding all the preoperative values (p > 0.05). All the 3 groups showed strong significant improvement for all the evaluated variants between preoperative and postoperative scores (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic data of the studied patients

| Group A | Group B | Group C | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 10) | (N = 10) | (N = 10) | ||

|

Age (y) Median (IQR) Mean ± SD |

29 (25–33) 29.6 ± 7.6 |

23.5 (20–35) 26.4 ± 8 |

24.5 (21–30) 25.8 ± 5.9 |

0.595 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 2 (20.0%) | 4 (40.0%) | 4 (40.0%) | 0.549 |

| Female | 8 (80.0%) | 6 (60.0%) | 6 (60.0%) |

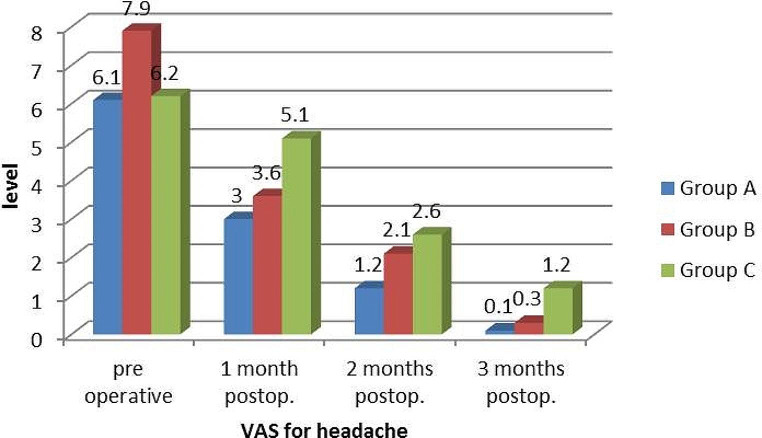

Upon comparing the 3 groups, there was a statistically significant difference in VAS score of nasal obstruction between the 3 groups regarding the whole follow-up period (p = 0.005, 0.002 and < 0.001, respectively) particularly, in comparing group A and B with group C, however, it was not significant in comparing group A and B (p = 0.9, 0.4 and 0.9, respectively) (Table 2), (Fig. 4). Although the postoperative VAS score of headache was not statistically different between group A and B (p = 0.08 and 0.9, respectively), there was a statistically significant difference upon comparing the 3 groups at the 2nd and 3rd postoperative months (p = 0.01 and 0.008, respectively) (Table 3), (Fig. 5).

Table 2.

Preoperative and postoperative nasal obstruction assessment by VAS

| Group A | Group B | Group C | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 10) | (N = 10) | (N = 10) | ||||

|

Preop. Median (IQR) Mean ± SD |

8 (7–9) 8.2 ± 0.7 |

8 (7–8) 8 ± 0.6 |

8(6–8) 7.8 ± 0.7 |

0.3 | ||

| A vs. B | A vs. C | B vs. C | ||||

| 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.5 | ||||

|

1 month postop. Median (IQR) Mean ± SD |

5 (4–7) 5.3 ± 0.9 |

5.5 (5–7) 5.6 ± 0.7 |

7 (5–8) 6.7 ± 0.8 |

0.005* | ||

| A vs. B | A vs. C | B vs. C | ||||

| 0.9 | 0.007* | 0.04* | ||||

|

2 months postop. Median (IQR) Mean ± SD |

3 (2–4) 2.9 ± 0.6 |

3 (3–4) 3.4 ± 0.5 |

4 (3–6) 4.5 ± 1 |

0.002* | ||

| A vs. B | A vs. C | B vs. C | ||||

| 0.4 | 0.001* | 0.09 | ||||

|

3 months postop. Median (IQR) Mean ± SD |

1 (1–2) 1.1 ± 0.3 |

1 (1–2) 1.2 ± 0.6 |

2 (2–3) 2.3 ± 0.5 |

< 0.001* | ||

| A vs. B | A vs. C | B vs. C | ||||

| 0.9 | < 0.001* | 0.001* | ||||

| p value (overtime) | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | |||

* p-value considered significant at < 0.05

Fig. 4.

Bar chart showing comparison between the three groups regarding VAS of nasal obstruction

Table 3.

Preoperative and postoperative headche assessment by VAS

| Group A | Group B | Group C | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 10) | (N = 10) | (N = 10) | ||||

|

Preop. Median (IQR) Mean ± SD |

7 (3–9) 6.1 ± 2.4 |

8 (5–9) 7.9 ± 1.2 |

7 (3–9) 6.2 ± 2.9 |

0.257 | ||

|

1 month postop. Median (IQR) Mean ± SD |

3 (2–4) 3 ± 0.9 |

3 (2–6) 3.6 ± 1.5 |

6 (2–8) 5.1 ± 2 |

0.3 | ||

|

2 months postop. Median (IQR) Mean ± SD |

1 (0–3) 1.2 ± 0.8 |

2 (1–3) 2.1 ± 0.5 |

2 (1–4) 2.6 ± 1.2 |

0.01* | ||

| A vs. B | A vs. C | B vs. C | ||||

| 0.08 | 0.02* | 0.9 | ||||

|

3 months postop. Median (IQR) Mean ± SD |

0 (0–0) 0.1 ± 0.3 |

0 (0–2) 0.3 ± 0.6 |

1 (0–3) 1.2 ± 1 |

0.008* | ||

| A vs. B | A vs. C | B vs. C | ||||

| 0.9 | 0.01* | 0.05* | ||||

| p value (overtime) | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | |||

* p-value considered significant at < 0.05

Fig. 5.

Bar chart showing comparison between the three groups regarding VAS of headche

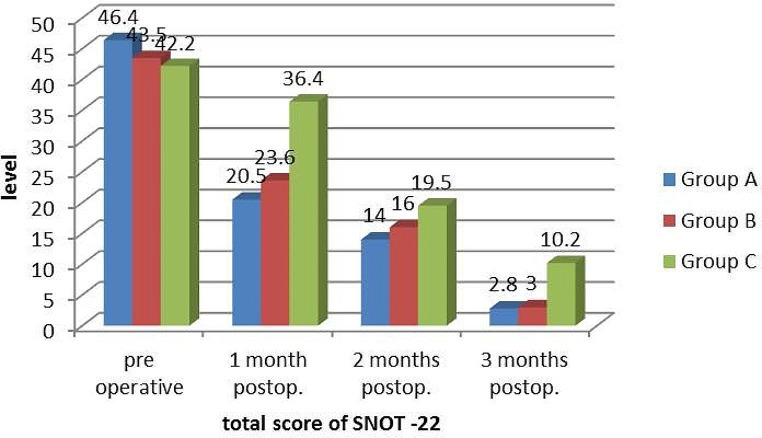

A statistically significant difference in olfactory detection score between the 3 groups was recorded at the 3rd postoperative month only (p = 0.04) and it was not significant upon comparing the independent groups (Table 4), (Fig. 6). There were a statistically significant differences in the 1st and 3rd postoperative months of SNOT-22 results between the 3 groups particularly, in comparing group A and B with group C, however, it was not significant in comparing group A and B (p = 0.8 and 0.9, respectively) (Table 5), (Fig. 7).

Table 4.

Preoperative and postoperative olfaction assessment by Butanol smell test

| Group A | Group B | Group C | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 10) | (N = 10) | (N = 10) | ||||

|

Preop. Median (IQR) Mean ± SD |

0 (0–8) 2.3.±3.7 |

2.5 (0–10) 3.3 ± 3.7 |

0 (0–10) 2.8 ± 3.8 |

0.873 | ||

|

1 month postop. Median (IQR) Mean ± SD |

0 (0–3) 0.6 ± 1.2 |

0 (0–6) 1.2 ± 2.1 |

0 (0–8) 2.5 ± 3.3 |

0.396 | ||

|

2 months postop. Median (IQR) Mean ± SD |

0 (0–3) 0.3 ± 0.9 |

0 (0–3) 0.3 ± 0.9 |

0 (0–5) 1.5 ± 2 |

0.117 | ||

|

3 months postop. Median (IQR) Mean ± SD |

0 (0–0) 0 ± 0 |

0 (0–0) 0 ± 0 |

0 (0–4) 1 ± 1.6 |

0.04* | ||

| A vs. B | A vs. C | B vs. C | ||||

| 0.9 | 0.08 | 0.08 | ||||

| p value (overtime) | 0.04* | 0.04* | 0.01* | |||

* p-value considered significant at < 0.05

Fig. 6.

Bar chart showing comparison between the three groups regarding olfaction

Table 5.

Preoperative and postoperative sinonasal symptoms assessment by SNOT-22

| Group A | Group B | Group C | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 10) | (N = 10) | (N = 10) | ||||

|

Preop. Median (IQR) Mean ± SD |

48.5 (39–51) 46.4 ± 7.1 |

47.5 (28–50) 43.5 ± 11.7 |

38 (36–48) 42.2 ± 13.8 |

0.466 | ||

|

1 month postop. Median (IQR) Mean ± SD |

21(14–27) 20.5 ± 4 |

26 (12–33) 23.6 ± 7.7 |

33 (21–56) 36.4 ± 11 |

0.001* | ||

| A vs. B | A vs. C | B vs. C | ||||

| 0.8 | 0.001* | 0.03* | ||||

|

2 months postop. Median (IQR) Mean ± SD |

14.5 (8–19) 14 ± 3.7 |

16 (6–25) 16 ± 7.6 |

19 (12–28) 19.5 ± 5.8 |

0.1 | ||

|

3 months postop. Median (IQR) Mean ± SD |

2 (0–7) 2.8 ± 2.5 |

3.5 (1–5) 3 ± 1.8 |

7.5 (3–26) 10.2 ± 8.2 |

0.01* | ||

| A vs. B | A vs. C | B vs. C | ||||

| 0.9 | 0.02* | 0.05* | ||||

| p value (overtime) | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | |||

* p-value considered significant at < 0.05

Fig. 7.

Bar chart showing comparison between the three groups regarding SNOT-22 of sinonasal symptoms

Overall, the three groups showed strong significant improvement over time in all the evaluated variables between preoperative and postoperative scores and also upon comparing group A and B (lateral laminectomy with and without mucosal preservation) with group C (Crushing). However, no significant differences were detected between group A and B regarding all the evaluated variables.

Discussion

Middle turbinate can be divided structurally into three segments; anterior, middle and posterior segments. Several types of anatomical variations of the middle turbinate were described, however, the pneumatized middle turbinate (concha bullosa) is the most frequently encountered variation [2, 3]. Bolger et al. classified pneumatization of the middle concha into three types: (1) In lamellar type, pneumatization is localized to the vertical lamella of the middle turbinate, (2) In bulbous type, pneumatization is localized to the inferior part of the middle turbinate. (3) In the extensive type, pneumatization involves both the vertical lamella and the inferior part of the middle turbinate [3].

Rhinosinusitis was detected more frequently in cases with extensive type concha bullosa occurred through compressing the uncinate process or through narrowing the middle meatus [5]. Concha bullosa may cause contact points that can trigger a rhinogenic headache [6]. So it is important to do surgery for concha bullosa simultaneously during functional endoscopic sinus surgery, not only because it contributes to osteomeatal and sinus disease but also to facilitate visualization of the osteomeatal complex during endoscopic sinus surgery [4].

There are many different techniques for the surgical treatment of concha bullosa, such as total resection, lateral or medial partial resection, turbinoplasty, crushing and crushing with intrinsic stripping. Each of these techniques has its own advantages and disadvantages, however, there is no clear consensus for the best surgical technique [7]. Three of the commonly used surgical techniques for concha bullosa are crushing, lateral laminectomy with mucosal preservation and lateral laminectomy without mucosal preservation. In our study, the differences between crushing and lateral laminectomy with and without mucosal preservation were studied according to the outcome of surgery.

Crushing is an easy and conservative technique, however, it is not applied for large concha bullosa that requires partial resection [8]. There are studies that reported recurrence after crushing such as Kieff and Busaba study [9]. While Tanyeri et al. did prospective study on 14 cases with concha bullosa and did not report any recurrence of pneumatization [10] and also Kocak et al. applied crushing to 95 concha bullosa cases and did not encounter any recurrence [11]. Recent studies reported that olfactory dysfunction is less encountered with crushing than with other techniques [7].

Lateral laminectomy is the most used technique for management of concha bullosa as this technique facilitate drainage from the frontal sinus recess into the middle meatus [12, 13]. The disadvantage of this technique is a risk of synechia formation. Canon et al. [13] reported no synechia, while Doğru et al. reported synechia rate of 27% [4]. The rates of synechia decrease when the mucosa is preserved [14–16].

We evaluated, in our study; headache, nasal obstruction, olfaction and severity of sinonasal symptoms as the main presenting symptoms in patients with concha bullosa. In this study, using preoperative and postoperative subjective evaluation that had been validated by many studies; VAS as a test for headache and nasal obstruction assessment, Butanol smell test as a test to assess olfaction, while SNOT-22 tests to assess severity of sinonasal symptoms.

In our study the majority of the patients in the three groups were in the second decade of life. This is comparative to the age distribution reported by Eren et al. [17]. However, it was different to the age distribution predominant in the third decade of life reported in other studies [18–20]. In our study, there was female predominance among patients with concha bullosa as what mentioned by Khalil et al. [20] and Hatipoglu et al. [19].

The postoperative headache assessment by VAS showed statistically significant improvement which was more in the two groups of lateral laminectomy than crushing group at the 2nd and 3rd postoperative months only (p = 0.01 and 0.008, respectively). While in comparing the two groups of lateral laminectomy with and without mucosal preservation, this improvement was statistically non-significant. There was a statistically significant difference in VAS score of nasal obstruction before and after surgery in the 3 groups. Upon comparing the 3 groups, there was a statistically significant difference in VAS score of nasal obstruction between the 3 groups (p = 0.005, 0.002 and < 0.001, respectively) particularly, in comparing lateral laminectomy groups with crushing group, however, it was not significant between both lateral laminectomy groups.

In our study, a statistically significant difference in olfactory detection score between the 3 groups was recorded at the 3rd postoperative month only (p = 0.04) and it was not significant upon comparing the independent groups. There were a statistically significant differences in the 1st and 3rd months postoperative SNOT results between the 3 groups particularly, in comparing lateral laminectomy groups with crushing group, however, it was not significant in comparing the lateral laminectomy groups. The overall results, in our study, showed more significant improvement of symptoms in the lateral laminectomy groups as compared with crushing. This significant difference was not recorded between the lateral laminectomy groups with and without mucosal preservation.

Regarding the evaluated postoperative headache, our results were similar to that in Osama AA.et al. [21] study showing significant improvement in postoperative headache in the studied two groups of lateral laminectomy with and without mucosal preservation, however, there was no statistically significant difference in the results on comparing the surgical groups. While Khalil et al. [20], in their study, reported that the postoperative headache assessment by VAS after 3 and 6 months showed statistically significant improvement that was more in mucosal preservation group.

Ankit et al. [18], in their study upon 63 patients, reported that postoperative improvement in nasal obstruction by VAS and severity of sinonasal symptoms by SNOT-22 was more or less same between the two groups of lateral laminectomy with and without mucosal preservation. While Khalil et al. [20] results showed significant improvement in both variables in patients of lateral laminectomy with mucosal preservation only after 3 months, but it was the same in both groups after 6 months.

In our study, the olfactory detection score was significantly better after 3 months with no significant differences between the surgical groups. This was concomitant to the reported results in Kumral et al. [22] and Havas and Lowinger [23] studies. We cannot comment on about any concern of the incidence of postoperative complications since we did not measure quantitatively, but none of our cases had anosmia, atrophic symptoms or sinusitis postoperatively.

Conclusion

We concluded that all the above mentioned surgical procedures for management of concha bullosa are safe and effective. According to our postoperative outcome results, most of comparative parameters were guided us to ensure that lateral laminectomy was more advantageous than crushing. Our study revealed that lateral laminectomy without mucosal preservation for surgical management of concha bullosa was as effective as lateral laminectomy with mucosal preservation and there is no detectable difference between the two techniques.

Funding

All authors declare that they did not receive any source of funding for this study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Ethical permission from faculty of medicine research ethics committee (FMREC) No:25:3/2022. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed Consent

Consent for post-mortem dissection was given by the donors and the Medical Council.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cantone E, Castagna G, Ferranti I, Cimmino M, Sicignano S, Rega F, et al. Concha bullosa related headache disability. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19(13):2327–2330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eweiss A, Khatwa M, Zeitoun H. Trifurcate middle turbinate; an unusual anatomical variation. Rhinology. 2008;46(3):246–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolger WE, Parsons DS, Butzin CA. Paranasal sinus bony anatomic variations and mucosal abnormalities: CT analysis for endoscopic sinus Surgery. Laryngoscope. 1991;101(1):56–64. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199101000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dogru H, Tuz M, Uygur K, Çetin M. A new turbinoplasty technique for the management of concha bullosa: our short-term outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2001;111(1):172–174. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200101000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tunçyürek Ö, Eyigör H, Songu M. The relationship among concha bullosa, septal deviation and chronic rhinosinusitis. ENT Updates. 2013;3(1):1. doi: 10.2399/jmu.2013001002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgenstein KM, Krieger MK. Experiences in middle turbinectomy. Laryngoscope. 1980;90(10):1596–1603. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198010000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed E, Hanci D, Ustun O. Surgıcal techniques for the treatment of concha bullosa: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Open J. 2018;4(1):9–14. doi: 10.17140/OTLOJ-4-146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doğru H, Uygur K, Tüz M. Concha Bullosa squeezer for turbinoplasty (Doğru forceps) The J Otolaryngology. 2004;33(2):111–113. doi: 10.2310/7070.2004.02112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kieff DA, Busaba NY. Reformation of concha bullosa following treatment by crushing surgical technique: implication for balloon sinuplasty. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(12):2454–2456. doi: 10.1002/lary.20640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanyeri H, Aksoy EA, Serin GM, Polat S, Türk A, Ünal ÖF. Will a crushed concha bullosa form again? Laryngoscope. 2012;122(5):956–960. doi: 10.1002/lary.23234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koçak İ, Gökler O, Doğan R (2016) Is it effective to use the crushing technique in all types of concha bullosa. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology. 273:3775–3781 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Braun H, Stammberger H. Pneumatization of turbinates. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(4):668–672. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200304000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richtsmeier WJ, Cannon CR. Endoscopic management of concha bullosa. Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery. 1994;110(4):449–454. doi: 10.1177/019459989411000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Har-El G, Slavit D. Turbinoplasty for Concha Bullosa: a non-synechiae-forming alternative to middle turbinectomy. Rhinology. 1996;34(1):54–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sigston EA, Iseli CE, Iseli TA. Concha Bullosa: reducing middle meatal adhesions by preserving the lateral mucosa as a posterior pedicle flap. J Laryngology Otology. 2004;118(10):799–803. doi: 10.1258/0022215042450814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta R, Kaluskar S. Endoscopic turbinoplasty of concha bullosa: long term results. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;65:251–254. doi: 10.1007/s12070-011-0368-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eren SB, Kocak I, Dogan R, Ozturan O, Yildirim YS, Tugrul S (eds) (2014) A comparison of the long-term results of crushing and crushing with intrinsic stripping techniques in concha bullosa Surgery. International forum of allergy & rhinology [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Ankit S, Nirali C, George A. Comparison between lateral partial turbinectomy and canthoplasty for concha bullosa. Natl J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;1(10):23–24. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatipoğlu HG, Cetin MA, Yüksel E. Concha Bullosa types: their relationship with sinusitis, ostiomeatal and frontal recess Disease. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2005;11(3):145–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khalil YA-w, Aboel-naga HA-r, Hussein A, GadAllah H (2018) AH. Comparative Study between lateral laminectomy and conchoplasty in the surgical treatment of symptomatic middle turbinate Concha Bullosa. Egyptian Journal of Ear, Nose, Throat and Allied Sciences. ;19(3):80 – 6

- 21.Albirmawy OA, Elsherif HS, Shehata EM, Younes A. Middle turbinate evacuation conchoplasty in management of contact-point rhinogenic headache in children. Int J Clin Pediatr. 2012;1(4–5):115–123. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumral TL, Yıldırım G, Cakır O, Ataç E, Berkiten G, Saltürk Z, et al. Comparison of two partial middle turbinectomy techniques for the treatment of a concha bullosa. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(5):1062–1066. doi: 10.1002/lary.25065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Havas TE, Lowinger DS. Comparison of functional endonasal sinus Surgery with and without partial middle turbinate resection. Annals of Otology Rhinology & Laryngology. 2000;109(7):634–640. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]