Abstract

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is a rare mesenchymal tumor with an indolent course but variable metastatic potential. Less than 50 cases of neck SFTs have been documented since 1991. We present a case report of rare presentations of SFT of nape of neck typifying the hypercellular variant of SFT (hemangiopericytoma) with challenges in treatment. Patient underwent excision and was subjected to adjuvant radiation. We concluded that SFT though a rare diagnosis should be considered while dealing with soft tissue tumors and multi-disciplinary pre-operative planning is must to avoid complications and recurrence. Surgical excision remains treatment of choice, but long follow-up is must.

Keywords: Case report, Solitary fibrous tumor, Hemangiopericytoma, Nape of neck SFT

Introduction

Solitary fibrous tumour (SFT) is a rare mesenchymal tumour, characterized by a peculiar branching vasculature, fibroblastic origin and NAB2-STAT6 gene rearrangement [1]. SFTs are proclaimed to have an indolent course. SFTs arise from serosal membranes like pleura, peritoneum and meninges. Earlier they were considered as only intra-thoracic tumours but later this mis-conception was cleared to current dictum that SFTs are can arise anywhere in body. The incidence of SFT is < 0.1 per 1,00,000 population/year and accounts for about 2% of all soft tissue tumours [8, 12]. No gender or environmental risk factor correlation have been reported [14].

SFTs tend to grow slowly and cause symptoms mostly due to mass effect on surrounding structures. They are known to cause paraneoplastic syndromes such as Doege-Potter syndrome, or rarely, hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy leading to clubbing [19]. Histologically SFTs presents as a spectrum ranging from high-fibrous low-cellular variant to a hypercellular variant [10]. Treatment of SFTs include gross total resection of tumour with radiation reserved for high-risk cases [11].

In this study, we present a case of SFT of neck and challenges in its management.

Case

40-year-old lady presented in OPD with complains of swelling over nape of neck since last 7 years. Excision of swelling was tried 5 years ago but operating surgeon abandoned the procedure due to excessive bleeding. On examination there was 6 × 6 cm swelling over posterior aspect of neck extending from basi-occiput to 6th cervical vertebra with old excision scar over skin. On local ultrasound examination it was a well-defined, heterogenous lesion with multiple cystic spaces and vascular channels. X-ray neck (Lateral & AP view) (Fig. 1a, b) revealed a soft tissue density lesion in left postero-lateral aspect of neck with no bony erosion. MRI of neck revealed a T2 hyperintense and T1 hypointense lesion in subcutaneous plane with maintained fat planes with neck muscles and no intramedullary extension (Fig. 2a–c). As there was prior history of profuse bleeding during excision, we decided not to do the biopsy and instead decided to go for pre-operative embolization of tumour. But as there were multiple feeding vessels (Fig. 3), embolization of feeding vessels was cancelled after discussion with interventional radiologist.

Fig. 1.

a, b X-ray neck lateral and AP view: soft tissue density lesion involving left postero-lateral aspect of neck with no associated bony erosion

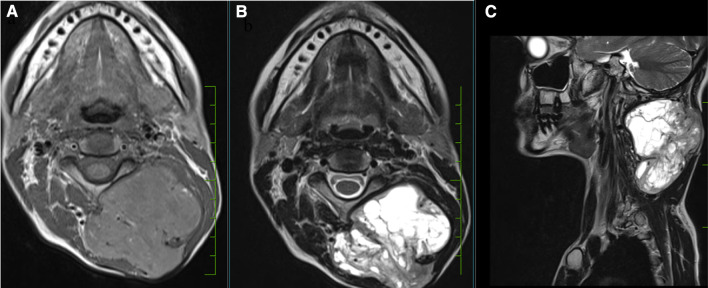

Fig. 2.

MRI neck: T1 hypointense (a) and T2 hyperintense (b, c) soft tissue lesion in left postero-lateral aspect of neck with no intramedullary extension

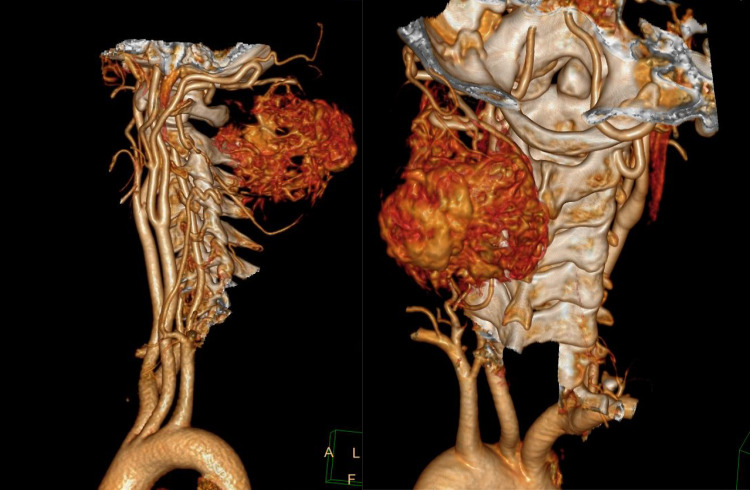

Fig. 3.

CT Angiography demonstrating hypervascular lesion with multiple feeding vessels

On exploration it was 10 × 9 cm (Fig. 4a, b) highly vascular tumour making excision quite perilous with significant blood loss. Upper edge of tumour was adherent to dura leading to intra-op dural breach at C1–C2 level requiring G-dural patch repair. Lumbar drain was kept till post-operative day 3 for allowing healing of dural patch repair. Gross total resection of tumour was done (Fig. 5). Post-operative course was uneventful.

Fig. 4.

Intra-operative photos. Note the scar due earlier attempted excision (a) thus patch of skin was also excised

Fig. 5.

Gross total resection specimen

Histopathological examination revealed a well circumscribed tumour with thin-walled staghorn vascular channels, mitotic rate of 4–10/ 10 HPF, tumour necrosis of > 10% with CD34 positivity on immuno-histochemistry (Fig. 6). Capsular invasion of margins was noted, but dura was not involved. D-score of 4 was given, stratifying the patient to intermediate risk according to Demicco et al. [4] classification.

Fig. 6.

a Multiple Staghorn vascular channels lined by single layer of endothelial cells; b High magnification image demonstrating mitotic figures(arrow); c High magnification image demonstrating necrosis(arrow); d Immuno-histochemistry demonstrating diffuse CD34positivity

Adjuvant radiation was given due microscopic positive margins. Patient is under surveillance and after 28 months of follow-up there is no evidence of recurrence.

Discussion

SFT was first described as benign mesothelioma by Wagner in 1870 [20] and was further characterised by Klemperer and Rabin [13] in 1931 but eventually it was identified by other terminologies e.g. submesothelial fibroma, localized mesothelioma, benign mesothelioma, etc. In 1942 Stout and Murray coined the term “Hemangiopericytomata” for hypercellular soft tissue tumours and claimed their origin from capillary pericytes [17]. With advances in histopathology and immunohistochemistry, in 2002 WHO classification of bone and soft tissue tumors, hemangiopericytomas were considered as a hypercellular subset of SFTs and its origin was from fibroblastic lineage contrary to the earlier belief of originating from pericytes [5].

Most symptoms are attributed to mass-effect of the tumour. Head and neck SFTs may present with voice changes, nasal obstruction or as an unsightly swelling. SFTs in abdomen may present with mass effects like early satiety, distention of abdomen or change in bowel habits [19]. Unsightly swelling was the chief presenting complain in our case also.

The radiographic features of SFT are largely nonspecific. CT demonstrates a well-defined lobulated mass with heterogenous or homogenous contrast enhancement. Cystic degeneration, intra-tumoral hemorrhage and calcifications can also be noted on CT.

On MRI, SFTs show low-intermediate intense T1-weighted images and heterogeneously low intense T2-weighted images in cases of hypocellular variants. Hypercellular variants appear hyperintense on T2-weighted images as are cystic degenerations, necrosis and hemorrhage [15].

Paraneoplastic syndromes may occur in patients with SFT, more frequently with large tumours in thorax and abdomen. Doege-Potter syndrome and hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy are 2 paraneoplastic syndromes associated with SFTs. Doege-Potter syndrome was first described in 1930 by Karl Doege and Roy Potter in a case of mediastinal tumor associated with hypoglycemia of non-pancreatic origin which resolved after excision of tumor. It is caused due to hypersecretion of IGF-2 by tumor. Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy presents as clubbing, synovial effusion and periostitis, exact cause of this is unknown but is mainly attributed to secretion of cytokines and hyaluronic acid from tumor [19].

Less than 50 cases of SFTs originating in neck have been reported since 1991 [16]. Making it an unusual occurrence.

Characteristic vasculature changes in SFTs include branching (staghorn) hyalinized vasculature surrounded by ovoid or spindle cells and variable deposition of collagen in stroma. These histopathological features along with expression of CD34 and/or STAT-6 on immunohistochemistry form essential criteria for diagnosis of SFT [1].

Resection of localised tumours with negative margins is standard of care treatment for SFTs [6].

Chung et al. [3] have found a high rate of positive margins on surgical pathology in there study of head and neck SFTs. Other studies of extracranial head and neck SFTs have also reported constraints in obtaining tumour free margins, either due to thin friable capsule or due to proximity to critical structures, [9] leading to presence at tumour cells at margin and R1 resection as was seen in our case.

Considering the spectrum of SFTs, hypercellular variant of SFTs tend to be highly vascular thus preoperative embolization should be considered to minimise intra operative complications [21].

SFTs with high risk features including high mitotic count, margin positive resection or extensive necrosis have been subjected to radiotherapy post excision which has been associated with decrease in local recurrences but no benefit in overall survival is established [2].

SFTs are known for their localised, slow growing nature though metastasis and recurrences post excision have been well-documented. In a recent study this concept was challenged as they demonstrated 41% recurrences at 10 years with 36% chance of disease-specific death [18].

In a study of 219 patients by Gholami et al. [7], they observed a 5 and 10-year risk of local recurrence of 4% and 7%, whereas risk of distant metastasis of 13% and 16% respectively. They concluded that large (> 8 cm) tumours in the chest or abdominal/retroperitoneal cavity are at greatest risk for recurrence and disease specific death also making point for long term follow-up of patients with SFT.

Demmico et al. [4], devised a risk stratification model based on age, tumour size, mitotic count and tumour necrosis for assessing risk of metastasis. They validated this score on 79 patients, with low-risk patients having no metastasis at 10 years, intermediate-risk patients: 10% risk of metastasis at 10 years and high-risk patients with 73% risk of metastasis at 5-years. But, Gholami et al. [7] noted metastasis even in patients without any adverse histopathological features. Thus, challenging the predictors for recurrence.

In our study, despite microscopic positive margins, there is no evidence of recurrence after 28 months of follow-up.

Conclusion

SFT though a rare diagnosis should be considered in differential diagnosis especially when dealing with soft tissue tumors. Glucose morning should be done in all cases of SFTs as there may be subclinical hypoglycemia. Gross complete resection of tumour stays the mainstay of the treatment. SFTs are tumors with variable metastatic potential, with metastasis usually occurring late. Hence, long term follow up is recommended.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviation

- SFT

Solitary fibrour tumor

Author contributions

SG was the chief operating surgeon in the cases and helped in writing the article. AV analysed and interpreted the patient data and was a major contributor in writing this article. TN helped with review of literature. ML did histopathological analysis of both the specimens. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Ethical approval and consent to participate and publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. Ethical approval was not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Board WCOTE (2020) Soft tissue and bone tumours (5th ed.). WHO Classification of Tumours, p 110

- 2.Bishop AJ, Zagars GK, Demicco EG, Wang WL, Feig BW, Guadagnolo BA. Soft tissue solitary fibrous tumor: combined surgery and Radiation Therapy results in excellent local control. Am J Clin Oncol. 2018;41(1):81–85. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung HR, Tam K, Han AY, Obeidin F, Nakasaki M, Chhetri DK, St John MA, Kita AE. Solitary fibrous tumors of the Head and Neck: a single-Institution Study of 52 patients. OTO Open. 2022;6(3):2473974X221098709. doi: 10.1177/2473974X221098709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demicco EG, Wagner MJ, Maki RG, Gupta V, Iofin I, Lazar AJ, Wang WL. Risk assessment in solitary fibrous tumors: validation and refinement of a risk stratification model. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(10):1433–1442. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2017.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fletcher CD. The evolving classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the new WHO classification. Histopathology. 2006;48(1):3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukunaga M, Naganuma H, Nikaido T, et al. Extrapleural solitary fibrous Tumor: a report of seven cases. Mod Pathol. 1997;10(5):443–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gholami S, Cassidy MR, Kirane A, Kuk D, Zanchelli B, Antonescu CR, Singer S, Brennan M. Size and location are the most Important risk factors for malignant behavior in resected solitary fibrous tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(13):3865–3871. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-6092-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gold JS, Antonescu CR, Hajdu C, Ferrone CR, Hussain M, Lewis JJ, et al. Clinicopathologic correlates of solitary fibrous tumors. Cancer. 2002;94:1057–1068. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson CH, Hunt BC, Harris GJ. Fate and management of incompletely excised solitary fibrous Tumor of the orbit: a case series and literature review. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;37(2):108–117. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kazazian K, Demicco EG, de Perrot M, Strauss D, Swallow CJ. Toward better understanding and management of solitary fibrous tumor. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2022;31(3):459–483. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2022.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King DM, Hackbarth DA, Kirkpatrick A. Extremity soft tissue sarcoma resections: How wide do you need to be? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:692e699. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2167-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinslow CJ, Wang TJC. Incidence of extrameningeal solitary fibrous tumors. Cancer. 2020;126(17):4067. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klemperer P, Rabin CB. Primary Neoplasms of the pleura: a report of five cases. Arch Pathol. 1931;11:385. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700220103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Penel N, Amela EY, Decanter G, Robin YM. Marec-berard P solitary fibrous tumors and so-called hemangiopericytoma. Sarcoma. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/690251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Abbott GF, McAdams HP, Franks TJ, Galvin JR. From the archives of the AFIP: localized fibrous tumor of the pleura. Radiographics. 2003;23(3):759–783. doi: 10.1148/rg.233025165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stanisce L, Ahmad N, Levin K, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors in the head and neck: comprehensive review and analysis. Head and Neck Pathol. 2020;14:516–524. doi: 10.1007/s12105-019-01058-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stout AP, Murray MR. Hemangiopericytoma: a vascular tumor featuring Zimmermann’s pericytes. Ann Surg. 1942;116:26. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194207000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan MC, Brennan MF, Kuk D, Agaram NP, Antonescu CR, Qin LX, Moraco N, Crago AM, Singer S. Histology-based classification predicts pattern of recurrence and improves risk stratification in primary Retroperitoneal Sarcoma. Ann Surg. 2016;263(3):593–600. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tay CK, Teoh HL, Su S. A common problem in the elderly with an uncommon cause: hypoglycaemia secondary to the Doege-Potter syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2014207995. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-207995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagner E. Das tuberkelähnliche Lymphadenom (Der Cytogene oder reticulirte Tuberkel) Arch Heilk (Leipzig) 1870;11:983–497. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiss B, Horton DA. Preoperative embolization of a massive solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73(3):983–985. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.