Abstract

Patients with chronic kidney disease are already at an increased risk for pulmonary embolism, since loss of renal function rendered a procoagulant state. Further, malignant tumor is a well-established risk factor for pulmonary thromboembolism. Alternatively, occlusion of the pulmonary vasculature by tumor cells per se and associated thrombi may mimic thromboembolic disease. By comparison, however, report of pulmonary tumor embolism (PTE) in patients on maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) is exceedingly rare. A less vigilant clinician may have otherwise treated this situation as fluid overload or thromboembolic disorder. We herein described in an MHD patient such an unusual case of PTE, which was diagnosed by contrast-enhanced CT and PET/CT. As such, our work may expand the knowledge reserve of dialysis staffs about this rare complication of malignancy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13730-023-00810-w.

Keywords: Maintenance hemodialysis, Pulmonary artery embolism, Tumor thrombi, Contrast-enhanced CT, PET-CT

Introduction

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are exposed to increased risk for pulmonary embolism (PE), since loss of renal function rendered a procoagulant state [1]. Accordingly, annual frequency of PE was 527, 204, and 66 per 100,000 persons with ESRD, CKD, and normal kidney function, respectively. In addition to renal function, malignant tumor is a well-established risk factor for pulmonary thromboembolism [2]. Alternatively, occlusion of the pulmonary vasculature by tumor cells per se and associated thrombi may mimic thromboembolic disease. In this regard, incidence of tumor embolism among patients with carcinoma was 0.9–2.4% [3]. By comparison, however, report of pulmonary tumor embolism (PTE) in patients on maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) is exceedingly rare and we herein presented such a case with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) as the underlying malignancy. The study had acquired proper institutional approval (20221016) and necessary consent from the patient.

Case report

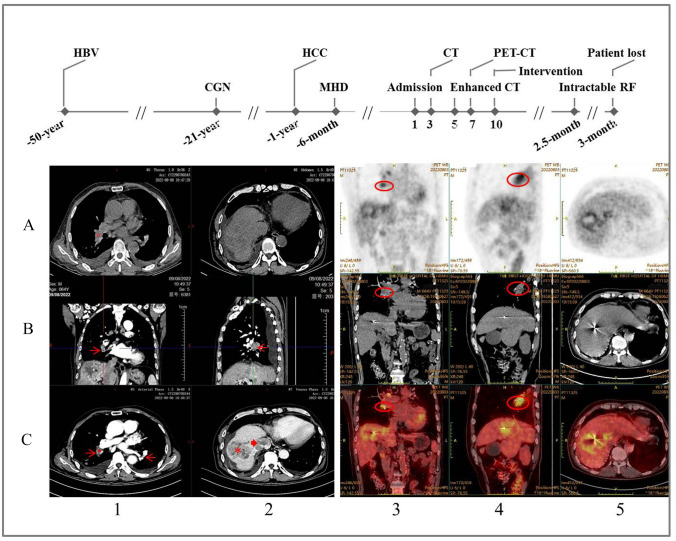

A 64-years-old anuric man was admitted for dyspnea and cough of 1 week after 6 months on MHD. Without diabetes, his medical history included viral hepatitis B, chronic glomerulonephritis, and HCC for 50, 21, and 1 year, respectively (Fig. 1). He had been treated by cyberknife radiosurgery and received routine follow-up 1 month prior to his admission during which his hemoglobin was 98 g/L (reference 130–150 g/L) and platelet was 158 × 109/L (125–350 × 109/L). According to the latest KDIGO guidelines [4], the patient received three weekly hemodialysis sessions of 4 h each, using bicarbonate-based dialysate and polysulfone membrane dialyzers as reported previously [5]. Generally, he was also given roxadustat, controlled-release nifedipine, and sevelamer carbonate for the treatment of anemia, hypertension, and hyperphosphatemia, respectively. Low-molecular-weight heparin was used for anticoagulation during the hemodialysis and his therapeutic regimen had no antiplatelet agent. When wheeled in, the patient was anemic with a panting appearance and his vitals were T 36.5 °C, P 96 beats/min, R 25 times/min, and BP 165/115 mmHg. Physical examination revealed no sign of asthma, pulmonary infection, pleural effusion, cardiac failure, and massive ascites. However, a loud S2 on cardiac auscultation, hepatomegaly, and moderate pitting edema of the lower extremities were found. Laboratory tests showed hemoglobin 84 g/L, platelet 205 × 109/L, D-dimer 2.32 mg/L (< 5.00 mg/L), BNP 1320 pg/mL (< 100 pg/mL). In blood gas analysis, PO2 and PCO2 were 114.0 and 18.8 mmHg on 3L oxygen by nasal cannula, respectively. No S1Q3T3 pattern was observed on electrocardiogram, whereas pulmonary artery pressure was 55 mmHg and flow tract of the right ventricular system appeared unobstructed on echocardiography. Ultrasound further confirmed the HCC and absence of deep vein thrombosis in his lower extremities. Plain chest CT scan detected metastasis of the HCC but no discernible lesion of the pulmonary artery, with a CT value of 38.8 Hounsfield units (HU) (Fig. 1A1). The patient was then managed by progressively increased ultrafiltration, downregulation of dry weight and daily use of lower molecular-weight heparin. However, his symptoms persisted unrelentingly and contrast-enhanced CT scan subsequently detected filling defects of the pulmonary artery, with a CT value of 65.6 and 63.7 HU during the arterial and venous phase, respectively (Fig. 1C1). Consistently, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) found accumulation of the 18FDG in the same arterial segment (Fig. 1). Tumor mass was also found at the ‘second hepatic hilum’ where hepatic vein joined the inferior vena cava (IVC) and the entry site of IVC to right atrium 1 week later during attempted catheter embolectomy (Fig. 2). The patient was then kept on palliative care with an arterial PO2 of 50 mmHg on ambient air 2.5 months after his diagnosis and eventually lost half a month later.

Fig. 1.

A brief overview of the patient’s medical history and results of major imaging examinations. Upper panel shows previous medical history and progression of the pulmonary tumor embolism. A1–2 Plain CT scan of the mediastinal window and abdomen, showing a CT value of 38.8 Hounsfield units (HU) for the right inferior pulmonary artery (red circle). B1–2 and C1 Three axial views of the filling defects in the pulmonary arteries by contrast-enhanced CT scan (red arrows), with a CT value of 65.6 HU during the arterial phase measured at the same site as in A1 (red circle). C2 Massive hepatocellular carcinoma (asterisk) and metastasis to the inferior vena cava (arrowhead). Row A–C across column 3–5 Accumulation of the 18FDG in the right inferior main pulmonary artery (red ellipses) and primary hepatocellular carcinoma. HBV hepatitis B virus, CGN chronic glomerulonephritis, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, MHD maintenance hemodialysis, RF respiratory failure

Fig. 2.

Metastatic mass at the entry site of inferior vena cava into the right atrium. The mass was materialized with the infusion of contrast media, effectively blocking advance of the catheter

Discussion

Thromboembolic diseases have been an issue of attention in MHD population as hemostasis is a heterogeneous condition in these patients [1]. Accordingly, abnormalities in platelet function and the coagulation cascade may lead to either increased risk of bleeding or clotting, depending on the counteracting effect of the defects. Less seen but no less deadly, PTE is a scenario that dialysis staffs should also be familiar with, especially when the risks of overall cancer occurrence were significantly higher in chronic dialysis patients than in the age-matched general population [6] and malignancy accounted for the third of all-cause mortality in the MHD population [7]. In this regard, our report may be essential to consider the care of dialysis patients with malignancy.

Pulmonary tumor embolism is characterized by emboli in the pulmonary arterial system (including alveolar and septal capillaries) consisting of tumor cells without fibrocellular intimal proliferation and not contiguous with the metastatic foci [3]. The most common primary malignancy was HCC before 2005, which was surpassed by breast and gastric cancer thereafter [8]. Tumor itself is known to express procoagulant proteins, leading to a hypercoagulable state in malignancy [9]. In clinical setting, it may present with a wide spectrum of symptoms, ranging from acute hypoxia, chest and abdominal pain to cough and indolent pulmonary hypertension. In MHD patients, nonetheless, these symptoms especially the dyspnea are most often caused by fluid overload and the associated hypertension and cardiac insufficiency. In this scenario, unaware dialysis staffs usually responded by increasing the ultrafiltration, and the resultant reduction in effective circulating blood volume may in turn improve cardiac index, elicit right ventricular overload, and exaggerate the PTE [10]. On occasion, unnecessary anticoagulation is given that may lead to potential bleeding hazard.

Contrast-enhanced CT and PET/CT are better diagnostic tools for differentiating PTE from bland thrombosis, since PTE but not thrombosis is enhanced in the former approach [11] and enriched with 18FDG in the latter [12]. Consistently, we observed increased CT values of the right inferior pulmonary artery in contrast-enhanced scan over the plain one. Indeed, the same arterial segment also showed 18FDG accumulation in the PET/CT scan. Arguably, FDG-PET/CT might be more useful when contrast-enhanced CT cannot distinguish tumor emboli from bland thrombi [13]. However, it is noteworthy that the 18FDG accumulation level of a tumor embolism might depend on the degree of differentiation and size of the tumor. As a matter of practice, the possibility of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and related thromboembolism has been clinically ruled out in our patient [14].

Cardiac surgery and urgent embolectomy have been proposed in selected patients with a satisfactory general condition [15]. The fact that HCC is predisposed to invade the IVC directly and extend proximally has eventually made catheter embolectomy unfeasible in our case. Pulmonary tumor embolism carries a poor prognosis in the late stages of malignancy in general and intracardiac involvement in particular predicts a very poor outcome with a mean survival of 1–4 months at the time of diagnosis [16]. Unfortunately, this inexorable finding was recorded in our case.

We herein described PTE in an MHD patient that highlighted the diagnostic use of contrast-enhanced CT and PET/CT and our experience may, thus, expand the knowledge reserve of dialysis staffs about this rare complication of malignancy in the MHD population. As such, persistent dyspnea in MHD patients with tumor especially the HCC should always raise the suspicion of PTE, which a less vigilant clinician may have otherwise treated as fluid overload or thromboembolic disorder.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors have declared no competing interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in our study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

7/28/2023

The original version is updated due to spell error in corresponding author email address.

References

- 1.Kumar G, Sakhuja A, Taneja A, et al. Milwaukee initiative in critical care outcomes research (MICCOR) group of investigators. Pulmonary embolism in patients with CKD and ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:1584–1590. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00250112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujieda K, Nozue A, Watanabe A, et al. Malignant tumor is the greatest risk factor for pulmonary embolism in hospitalized patients: a single-center study. Thromb J. 2021;19:77. doi: 10.1186/s12959-021-00334-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassiri AG, Haghighi B, Doyle RL, Berry GJ, Rizk NW. Pulmonary tumor embolism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:2089–2095. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.6.9196119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, Prevention, and Treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2017;7:1–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Wang T, Li Y, Wu HB, et al. Optimal blood pressure for the minimum all-cause mortality in Chinese ESRD patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Biosci Rep. 2020;40:BSR20200858. doi: 10.1042/BSR20200858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung CY, Tang SCW. Oncology in nephrology comes of age: a focus on chronic dialysis patients. Nephrology (Carlton) 2019;24:380–386. doi: 10.1111/nep.13525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moroi M, Tamaki N, Nishimura M, et al. Association between abnormal myocardial fatty acid metabolism and cardiac-derived death among patients undergoing hemodialysis: results from a cohort study in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61:466–475. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He X, Anthony DC, Catoni Z, Cao W. Pulmonary tumor embolism: a retrospective study over a 30-year period. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0255917. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khorana AA, Ahrendt SA, Ryan CK, et al. Tissue factor expression, angiogenesis, and thrombosis in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2870–2875. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanghavi SF, Freidin N, Swenson ER. Concomitant lung and kidney disorders in critically ill patients: core curriculum 2022. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;79:601–612. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogawa Y, Abe K, Hata K, Yamamoto T, Sakai S. A case of pulmonary tumor embolism diagnosed with respiratory distress immediately after FDG-PET/CT scan. Radiol Case Rep. 2021;16:718–722. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2021.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wittram C, Scott JA. 18F-FDG PET of pulmonary embolism. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:171–176. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.0640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xi XY, Gao W, Gong JN, et al. Value of 18F-FDG PET/CT in differentiating malignancy of pulmonary artery from pulmonary thromboembolism: a cohort study and literature review. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;35:1395–1403. doi: 10.1007/s10554-019-01553-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greinacher A. Clinical practice. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:252–261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1411910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin HH, Hsieh CB, Chu HC, Chang WK, Chao YC, Hsieh TY. Acute pulmonary embolism as the first manifestation of hepatocellular carcinoma complicated with tumor thrombi in the inferior vena cava: surgery or not? Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1554–1557. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sung AD, Cheng S, Moslehi J, Scully EP, Prior JM, Loscalzo J. Hepatocellular carcinoma with intracavitary cardiac involvement: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:643–645. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.