Abstract

Background

Clinical neurophysiology (CNP) involves the use of neurophysiological techniques to make an accurate clinical diagnosis, to quantify the severity, and to measure the treatment response. Despite several studies showing CNP to be a useful diagnostic tool in Movement Disorders (MD), its more widespread utilization in clinical practice has been limited.

Objectives

To better understand the current availability, global perceptions, and challenges for implementation of diagnostic CNP in the clinical practice of MD.

Methods

The International Parkinson and Movement Disorders Society (IPMDS) formed a Task Force on CNP. The Task Force distributed an online survey via email to all the members of the IPMDS between August 5 and 30, 2021. Descriptive statistics were used for analysis of the survey results. Some results are presented by IPMDS geographical sections namely PanAmerican (PAS), European (ES), African (AFR), Asian and Oceanian (AOS).

Results

Four hundred and ninety‐one IPMDS members (52% males), from 196 countries, responded. The majority of responders from the AFR (65%) and PAS (63%) sections had no formal training in diagnostic CNP (40% for AOS and 37% for ES). The most commonly used techniques are electroencephalography (EEG) (72%) followed by surface EMG (71%). The majority of responders think that CNP is somewhat valuable or very valuable in the assessment of MD. All the sections identified “lack of training” as one of the biggest challenges for diagnostic CNP studies in MD.

Conclusions

CNP is perceived to be a useful diagnostic tool in MD. Several challenges were identified that prevent widespread utilization of CNP in MD.

Keywords: clinical neurophysiology, movement disorders, tremor, electromyography, accelerometry

Clinical neurophysiology (CNP) in movement disorders (MD) involves utilizing objective neurophysiological techniques as an extension of neurological exam to help make accurate clinical diagnosis, quantify the severity, and measure the treatment response. CNP is widely used for these purposes in epilepsy, neuromuscular and sleep disorders. Although CNP has been utilized extensively for research, significantly contributing and forming the bedrock of our understanding of pathophysiology of MDs, its utilization in clinical practice has been limited. Despite several studies showing CNP to be useful as a diagnostic tool, its more widespread utilization in MD clinical practice has been limited. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 Different challenges limit the utilization of CNP in different geographical regions, as the practice of neurology (and medicine in general) varies globally.

The International Parkinson and Movement Disorders Society (IPMDS) recognized the need to better understand the current availability, global perceptions, and challenges for more widespread utilization of diagnostic CNP in the clinical practice of MD. To address these knowledge gaps a Task Force on Clinical Neurophysiology was convened and an online survey tool was created to answer these questions and obtain input from IPMDS members. In this manuscript, we present the results of this online survey on behalf of the Task Force.

Methods

An international Task Force comprised of investigators with clinical and research expertise in clinical neurophysiology was organized, ensuring fair representation from different IPMDS subsections. Several meetings were organized to discuss the current challenges for CNP in different geographic regions and based on the inputs and deliberations over virtual meetings an online survey was created and approved. The IPMDS sent an email invitation to all its members to complete the online survey, which was available between August 5 and 30, 2021.

Descriptive statistics were used for presentation of the survey results. Some results are presented by IPMDS geographical sections namely PanAmerican (PAS), European (ES), African (AFR), Asian and Oceanian (AOS). Chi‐square tests were used for comparisons between geographical sections with Bonferroni correction and presented in supplementary material. For between‐section comparisons, the ES group was arbitrarily selected as a reference to minimize the number of comparisons. For ordinal categorical answers such as: “strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree,” a weighted average was calculated by assigning an ascending value to the responses with an incremental meaning (strongly disagree = 1, disagree = 2, neutral = 3, agree = 4, strongly agree = 5) and then calculating the average value of all the responses. Average closer to 1 means that most responders tend to disagree, average of 3 means that responses were balanced between agree and disagree, average closer to 5 means that most responders tend to agree. For between geographical regions comparisons, the answers were grouped into three levels: agree, neutral, disagree and chi‐square was used. ES group was used as a reference group.

Results

Survey Population

The survey was sent to 10,389 IPMDS active members by email. Four hundred and ninety‐one IPMDS members (52% males), from 196 countries, responded to the survey (the number of responses per section were: PAS = 118, ES = 142, AFR = 54, AOS = 174 and 3 participants unknown). 69% were Neurologists, 11% Neurologists in‐training (Neurology residents and MD fellows) and the rest were PhD scientists (7%), physical and occupational therapists (4%), neurosurgeons (1%). A quarter of the responders (24%) have been in practice for less than 5 years and another quarter (26%) for more than 20 years. 73% of responders work in an academic setting. 40% of the responders see less than 10 MD patients per week and 39% of them see 10–30 MD patients per week. Majority of responders from the AFR (65%) and PAS (63%) sections had no formal training in diagnostic CNP (40% for AOS and 37% for ES).

CNP Availability

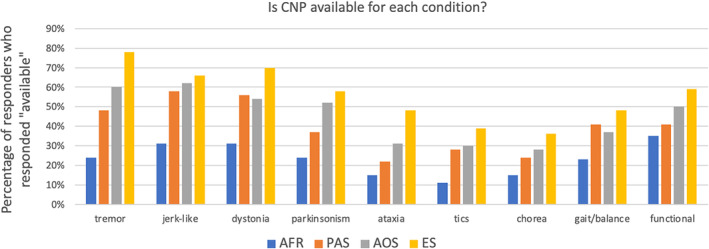

CNP is available to the majority of responders from the ES and AOS for patients with tremor (ES:78%, AOS:60%), jerk‐like movements (ES:66%, AOS:62%), dystonia (ES:70%, AOS:54%), parkinsonism (ES:58%, AOS:52%) and functional movements (ES:59%, AOS:50%) (Fig. 1, see between‐group comparisons in Table S1). CNP is available for the majority of responders from the PAS section only for jerk‐like movements (58%) and dystonia (56%). In the AFR section, CNP is available to a minority of responders for all MD.

Figure 1.

Percentage of responders who responded “available” to the survey question “Is clinical neurophysiology (CNP) available for each condition?”. Results presented by International Parkinson and Movement Disorders Society section.

For CNP studies of tremor, jerk‐like movements and dystonia, most responders reported that they refer their patients. For the question, “what percentage of your patients with each condition, do you refer/perform a CNP study?,” the majority of the responders answered less than 25% for every condition (Fig. 2—see break down per geographical region in Figure S1). Also, the majority of the responders answered that they perform/refer <10 studies/patients per month for every condition.

Figure 2.

Absolute number of responders who perform clinical neurophysiology (CNP) studies or refer their patients for each condition.

The most used CNP techniques were electroencephalography (EEG) (72%) followed by surface EMG (71%). The other techniques reported to be used were peripheral nerve stimulation (47%), somatosensory evoked potentials (47%), gait analysis (29%), accelerometry (27%), surface EMG burst duration (26%), coherence (EMG–EMG or EEG–EMG) (23%), balance testing (22%), back averaging (including Bereitschaftspotential) (20%), qualitative review of raw EMG and accelerometric traces (19%), fast Fourier transform (17%), long loop reflex (c‐reflex) (16%).

Perception of CNP Utility

The majority of responders think that CNP is somewhat valuable or very valuable in the assessment of every condition. More than 10% of the responders think that CNP is not valuable for parkinsonism, ataxia, tics and chorea; whereas for all other conditions the responders who think that CNP is not valuable were less than 10% (Fig. 3—see break down per geographical region in Figure S2). More than 10% of the responders did not know how valuable CNP is in the assessment of all conditions [except for tremor (7%)].

Figure 3.

Percentage of answers to the question “How valuable is CP in the assessment of each condition?”.

The majority of participants agreed or strongly agreed that CNP “is an extension of clinical exam” (weighted average 3.91), that “it can reinforce or change clinical diagnosis” (weighted average 3.93), and that “it can change management” (weighted average 3.81). The participants tended to disagree with statements such as “it is too complicated to interpret” (weighted average 2.7), “its diagnostic yield is too low” (weighted average 2.6) and “it is not necessary in clinical practice” (weighted average 2.2).

Challenges

Regarding the cost of the studies, in the AFR section the majority of the responders indicated that the patient covers part or all the cost. In contrast, the majority of the responders from ES answered that the government covers part or all of the cost (Fig. 4). The ES section had statistically significantly more responders compared to all the other sections, who indicated that the government covers the cost and statistically significantly less responders who indicated that the patient covers the cost (see between‐group comparisons in Table S2).

Figure 4.

Percentage of answers regarding cost coverage for clinical neurophysiology studies, by International Parkinson and Movement Disorders Society section.

The responders from the AFR section were neutral about whether “the benefits can justify the cost”. However, responders from all other sections tended to agree that “the benefits can justify the cost” (weighted averages were AOS: 3.6, ES: 3.8 and PAS: 3.6). All sections except the ES agreed that two of the biggest challenges for diagnostic CNP studies in MD are the cost to perform (weighted averages were AFR: 3.9, AOS: 3.3, PAS: 3.5 and ES: 2.9) and the lack of reimbursement scheme (weighted averages were AFR: 4.1, AOS: 3.5, PAS: 3.5 and ES: 2.6) (Between sections comparisons in Table S3).

All the sections identified “lack of training” as one of the biggest challenges for diagnostic CNP studies in MD (weighted averages were AFR: 4.5, AOS:4.1, ES:4.1 and PAS:4.3). Other challenges were the “lack of normative values” (weighted average for all sections 3.85), “lack of referral base” (weighted average for all sections 3.63), “difficulties to interpret” (weighted average for all sections 3.46) and “lack of standardized equipment” (weighted average for all sections 3.46).

Future Directions

The vast majority of the responders (93%) suggest that MD training curriculum should include training in diagnostic CNP. Also, the majority (90%) is interested in participating in training courses.

Discussion

This manuscript presents the results of a survey on CNP in movement disorders as part of the work of the IPMDS Task Force on CNP. With this survey the Task Force attempted to describe the availability and utility of CNP as well as the perceptions and challenges for wider adoption of these tools. Four hundred and ninety‐one responses from 196 countries were thought to be representative of the global medical community that treats patients with MD. The results are biased towards more academic representation (73% of responders).

Regarding the worldwide availability of CNP, we identified a geographical pattern of reduced availability in the PAS and AFR sections compared to the ES and AOS. A similar pattern was identified with regards to CNP training, as less responders from the PAS and AFR sections had formal training on CNP, compared to the ES and AOS. This could be explained by the fact that CNP is not part of the formal training curriculum in MD fellowship in the PAS and AFR section, whereas in the ES and AOS formal CNP training is commonly incorporated in residency and fellowship.

As regards CNP availability for different MDs, the majority of participants responded affirmatively for tremor, jerk‐like movements, and functional neurological disorders. This aligns with the current literature on this subject, with several studies showing good utility of CNP for diagnostic testing for these disorders. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 The current evidence about utility of CNP for diagnostic purposes in parkinsonism and dystonia and higher than expected response for these disorders is unclear. It is plausible that the responses could have been confounded by utilization of these tests for differential diagnosis of tremor and jerk‐like MDs, which are common phenotypes in Parkinsonism and dystonias. Utilization of EMG guidance for botulinum toxin injections for dystonia could have potentially also been considered use of CNP.

Overall, CNP is perceived to be a useful diagnostic tool in MD, as the majority of the responders have a positive opinion about its utility. The conditions that CNP is thought to be most useful are tremor, jerk‐like movements, gait/balance and functional movement disorders. Only a small percentage of the patients with MD (<25%) receive a CNP study which may be due to limited utilization or limited need. The most useful techniques are EMG, EEG and peripheral nerve stimulation, but the questions did not differentiate exactly in what ways these techniques are used. We suspect that the most common use of EEG in movement disorders is in the setting of back averaging (for cortical myoclonus or readiness potentials), somatosensory evoked potentials or EMG–EEG coherence. This information can be valuable for estimation of equipment and procedural cost as well as utilization rates calculations.

The challenges for each geographical section are different, reflecting the heterogeneity of health systems in different countries. In Europe, where national health systems are common, the government covers most of the cost and consequently the cost to perform and reimbursement are not perceived as major challenges. However, this is not the case for other regions such as the AFR where most frequently the cost falls on the patient. Perhaps, more studies towards the sensitivity and specificity of CNP testing in MD will provide evidence for a compelling argument for government and health insurance to cover more of the cost. Another significant challenge is the “lack of training” with the vast majority of responders thinking that CNP should be part of the MD training curriculum. It is interesting to note that the vast majority of responses of this survey (73%) come for academic settings and based on the demographic characteristics of the responders, the need for more training is likely echoed by both the trainers and trainees. Therefore, MD training programs should take this into account when updating their curricula. Also, CNP programs that are mainly focused on epilepsy and neuromuscular disorders, could consider expanding their scope to include CNP techniques for MD. In addition, the majority of the participants expressed interest in training courses which highlights an opportunity for organizations like the IPMDS to expand its training programs towards this direction. Finally, “lack of standardized procedures” and “lack of standardized equipment” are challenges and an opportunity for future work. Furthermore, a recent paper on this topic showed that there is a lack of evidence for almost all the tests. 2 The effort for validation of electrodiagnostic criteria for functional movements disorders should serve as an example for similar work in other movement disorders. 4

Although we consider our sample of responders to be representative of the global community of providers that treat MD, we cannot ignore the fact that the nature of the study, being an online survey, makes it vulnerable to selection bias. IPMDS members not interested in CNP might have ignored the email invitation. However, our results were not heavily biased by responders who are directly involved in CNP studies, and a large proportion of the responders do not perform CNP studies but refer their patients. Another limitation is that the survey captured responses from only a small fraction of all the MD providers worldwide; however, the participation and response rates were comparable to prior MDS surveys on different topics.

In summary, this survey highlights that IPMDS members have a positive opinion about the utility of CNP in the practice of MD but the lack of training and cost are two important challenges that need to be addressed before CNP is widely adopted. The IPMDS has now formed a study group on CNP as the next step after the completion of the Task Force goals. The study group will conduct several projects on this topic and welcomes IPMDS members to participate and put forward their opinions.

Author Roles

(1) Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; (3) Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing of the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

P.K.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 3A

R.C.: 1B, 1C, 2C, 3B

C.G.: 1B, 1C, 2C, 3B

M.H.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2C, 3B

M.H.: 1B, 1C, 2C, 3B

A.L.: 1B, 1C, 2C, 3B

P.K.P.: 1B, 1C, 2C, 3B

P.S.: 1B, 1C, 2C, 3B

F.V.: 1B, 1C, 2C, 3B

M.A.T.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2C, 3B

S.M.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2C, 3B

Disclosures

Ethical Compliance Statement: This study did not require approval by an Institutional Review Board. Informed patient consent was not necessary for this work. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest: No specific funding was received for this work. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

Financial Disclosures for Previous 12 Months: PK: No additional disclosures to report. RC: No additional disclosures to report. CG: Receives research support by VolkgswagenStiftung (Freigeist) and has received honoraria for educational activities from the Movement Disorder Society and Bial Pharmaceuticals. MH: is an inventor of a patent held by NIH for the H‐coil for magnetic stimulation for which he receives license fee payments from the NIH (from Brainsway). He is on the Medical Advisory Boards of Brainsway, QuantalX, and VoxNeuro. MH: Received honoraria from AbbVie GK, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Kyowa Kirin, Ono Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Sumitomo Pharma, and Takeda Pharmaceutical. AL: No additional disclosures to report. PKP: Received research grants from the ICMR, DBT and Michael J. Fox Foundation and honoraria as Faculty from the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society, and Movement Disorder Societies of Korea, Taiwan and Bangladesh. PS: Received personal fees from Bial. FV: No additional disclosures to report. MAT: Reports grants from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development ZonMW Topsubsidie (91218013) and ZonMW Program Translational Research (40‐44600‐98‐323). She also received a European Fund for Regional Development from the European Union (01492947) and a European Joint Programme on Rare Diseases (EJP RD) Networking Support Scheme. Furthermore, from the province of Friesland, the Stichting Wetenschapsfonds Dystonie and unrestricted grants from Actelion, AbbVie and Merz. SHM: No additional disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Absolute number of responders who perform CNP studies or refer their patients for each condition. Break down by geographical region.

Figure S2. Percentage of answers to the question “How valuable is CP in the assessment of each condition?”. Break down by geographical region.

Data S1. Supporting information.

Table S1. CNP availability. Between geographical sections comparisons. ES group was used as a reference group. Significant values are noted with an asterisk (based on Bonferroni correction).

Table S2. Cost coverage. Between geographical sections comparisons. ES group was used as a reference group. Significant values are noted with an asterisk (based on Bonferroni correction).

Table S3. Answers were grouped into three levels: agree, neutral, disagree, and between groups, comparisons were performed. ES group was used as a reference group. Significant values are noted with an asterisk (based on Bonferroni correction).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Yao He (University of Utah) for providing statistical support.

Marina A. Tijssen and Shabbir Merchant contributed equally.

References

- 1. Gandhi SE, Silverdale MA, Mercer D, Marshall AG, Kobylecki C. Real world use of a neurophysiology service for the differential diagnosis of hyperkinetic movement disorders. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2020;71:11–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van der Veen S, Klamer MR, Elting JWJ, Koelman JHTM, van der Stouwe AMM, Tijssen MAJ. The diagnostic value of clinical neurophysiology in hyperkinetic movement disorders: a systematic review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2021;89:176–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jackson L, Klassen BT, Hassan A, Bower JH, Matsumoto JY, Coon EA, Ali F. Utility of tremor electrophysiology studies. Clin Park Relat Disord 2021;5:100108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schwingenschuh P, Saifee TA, Katschnig‐Winter P, et al. Validation of "laboratory‐supported" criteria for functional (psychogenic) tremor. Mov Disord 2016;31(4):555–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Everlo CSJ, Elting JWJ, Tijssen MAJ, van der Stouwe AMM. Electrophysiological testing aids the diagnosis of tremor and myoclonus in clinically challenging patients. Clin Neurophysiol Pract 2022;7:51–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zutt R, Elting JW, van Zijl JC, et al. Electrophysiologic testing aids diagnosis and subtyping of myoclonus. Neurology 2018;90(8):e647–e657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brown P, Thompson PD. Electrophysiological aids to the diagnosis of psychogenic jerks, spasms, and tremor. Mov Disord 2001;16(4):595–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kamble NL, Pal PK. Electrophysiological evaluation of psychogenic movement disorders. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016;22(Suppl 1):S153–S158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McAuley JH, Rothwell JC, Marsden CD, Findley LJ. Electrophysiological aids in distinguishing organic from psychogenic tremor. Neurology 1998;50(6):1882–1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Absolute number of responders who perform CNP studies or refer their patients for each condition. Break down by geographical region.

Figure S2. Percentage of answers to the question “How valuable is CP in the assessment of each condition?”. Break down by geographical region.

Data S1. Supporting information.

Table S1. CNP availability. Between geographical sections comparisons. ES group was used as a reference group. Significant values are noted with an asterisk (based on Bonferroni correction).

Table S2. Cost coverage. Between geographical sections comparisons. ES group was used as a reference group. Significant values are noted with an asterisk (based on Bonferroni correction).

Table S3. Answers were grouped into three levels: agree, neutral, disagree, and between groups, comparisons were performed. ES group was used as a reference group. Significant values are noted with an asterisk (based on Bonferroni correction).